The Old Curiosity Club discussion

Little Dorrit

>

Little Dorrit Chapters 27-29

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Chapter 28

An Appearance in the Marshalsea

Ferdinand Barnacle: “Regard our place from the point of view that is the essential thing. Regard our place from the point of view that we only ask you to leave us alone, and we are as capital a Department as you’ll find anywhere.”

Blandois: “I had, and that I have – do you understand me? Have a commodity to sell to my lady your respectable mother. I described my precious commodity, and fixed my price … a gentleman must be amused at somebody’s expense!”

I have placed two epigraphs above since this long chapter divides itself into two separate parts. The first part deals with a conversation Arthur has with Ferdinand Barnacle about the Circumlocution office. The second part is an unpleasant conversation between Arthur and Blandois. Let’s take a look at the Barnacle conversation first.

Arthur is having great difficulty adjusting to life within the walls of the Marshalsea. He is gloomy, out of sorts, and slowly descending into a very unhealthy state of life. The last thing he probably wanted was to have a visit from any of the Barnacles but that is exactly what happens. Ferdinand Barnacle, a “sprightly” and totally obnoxious person, appears at Arthur’s door. Ferdinand hopes that the Circumlocution Office has played no part in Arthur’s present situation. Ferdinand is aware that, at times, the Circumlocution Office does grind people down but “if men will be gavelled, why - we can’t help it.” I can imagine the joy with which Dickens mocked the office with sarcastic remarks such as “we only ask you to leave us alone.” I’m amazed that Arthur did not raise himself from his sick bed and attempt to strangle Young Ferdinand. No doubt, however, Arthur’s measured and controlled responses add to the level of bitterness that comes from the pen of Dickens. Ferdinand comments that he would be “greatly vexed if you don’t take the warning by the past and keep away from us.” A subtle warning? Perhaps Ferdinand is too dense to realize what he is saying?

Ferdinand does not care about Doyce’s invention and has no intention of ever starting to have any interest in the humbug idea. Concerning Merdle, Ferdinand says that the next man to come along with a genuine taste for swindling will also succeed. From these first paragraphs of the chapter Dickens has delivered two insights into society. The first is that one should never rely on any government bureaucracy to support an individual’s initiatives or needs. The other is that cons and swindlers will always exist and take advantage of others. As readers we are left with the question as to what is worse and more contemptible. Is it a government that will do nothing to aid the population or crooks and swindlers who do so much damage in a population? Indeed, I think Dickens suggests that these two options are simply opposite sides of the same coin.

Arthur is second visitor is the lawyer Rugg who attempts to convince Arthur to make a concession to public opinion and be moved to the Bench where Arthur’s case will be dealt with as more than simply a person who owns a few pounds to another person. Arthur is, however, resolute. He will not be transfers to the “superior abode” of the Bench. Arthur thinks the Marshalsea is a place of better punishment. Do you think Arthur is being noble, foolish, or simply obstinate in remaining at the Marshalsea?

Arthur’s third visitor of the day (one wonders how tired Arthur must be with all this activity) is a surprise. It is none other than the missing Blandois who is followed by Pancks and Cavalletto. Blandois immediately takes up his usual poise of lounging in the room. Arthur immediately launches into an attack on the character of Blandois and how he has upset his mother and cast “dreadful suspicions” upon the company. We learn that Blandois has been staying in London in disguise. There are many layers to this man. So far he has used three names and assumed different disguises and identities. What evil lurks at the core of his being?

It is clear that Arthur despises Blandois. He demands of Blandois “how you dare direct a suspicion of murder against my mother’s house?” But oh, Blandois is one cold and cruel man. He cannot be intimidated or even upset by Arthur or the situation he finds himself in. I can’t forget the first time we meet Blandois at the beginning of the novel. From that point on Blandois has been cold, detached, and seemingly unable to be ruffled in any way. His languid posture is more telling than the facial contortions he does with his nose and his lips and moustache.

So, let’s see what we can learn about Blandois and his connection to the Clennam household.

he has “a commodity” to sell to Arthur’s mother.

he has “fixed my price” for this commodity.

Arthur’s mother angered Blandois with her “too calm, too stolid, too unmovable attitude.

there is some unexplained connection between Blandois and Flintwinch.

We are told that “the difficulties of a certain contract would be removed by the appearance of a certain party to it.” Wow, that’s mysterious!

Blandois appears to be in total control of the situation and is dictating the events that are unfolding in the jail.

Blandois writes a letter to Mrs Clennam and tells her that she has one week to “unconditionally accept” his offer or to suffer the consequences.

That Mrs Clennam now pay for his lodging and his food for the coming week.

While waiting for a reply from Mrs Clennam, Blandois mentions both Pet and Miss Wade and that he became a spy for Miss Wade and reported to her on the relationship between Pet and Gowan. Flintwinch returns to the group with a response to Blandois’s letter, is embraced by Blandois, and that is followed by Flintwinch chastising Arthur for not ignoring Blandois in the past. Flintwinch hands Arthur a letter from his mother. The contents are severe, cruel, and unfeeling towards her son. Flintwinch then tells Blandois that Mrs Clennam agrees to his terms.

As this most confusing chapter ends Blandois appears the victor, and Arthur and his mother the losers. The question is, what is it that Blandois holds over their heads? Poor Arthur, he is now alone again in his cell and no doubt even more worn out from all the visitors he has seen in the past few hours.

An Appearance in the Marshalsea

Ferdinand Barnacle: “Regard our place from the point of view that is the essential thing. Regard our place from the point of view that we only ask you to leave us alone, and we are as capital a Department as you’ll find anywhere.”

Blandois: “I had, and that I have – do you understand me? Have a commodity to sell to my lady your respectable mother. I described my precious commodity, and fixed my price … a gentleman must be amused at somebody’s expense!”

I have placed two epigraphs above since this long chapter divides itself into two separate parts. The first part deals with a conversation Arthur has with Ferdinand Barnacle about the Circumlocution office. The second part is an unpleasant conversation between Arthur and Blandois. Let’s take a look at the Barnacle conversation first.

Arthur is having great difficulty adjusting to life within the walls of the Marshalsea. He is gloomy, out of sorts, and slowly descending into a very unhealthy state of life. The last thing he probably wanted was to have a visit from any of the Barnacles but that is exactly what happens. Ferdinand Barnacle, a “sprightly” and totally obnoxious person, appears at Arthur’s door. Ferdinand hopes that the Circumlocution Office has played no part in Arthur’s present situation. Ferdinand is aware that, at times, the Circumlocution Office does grind people down but “if men will be gavelled, why - we can’t help it.” I can imagine the joy with which Dickens mocked the office with sarcastic remarks such as “we only ask you to leave us alone.” I’m amazed that Arthur did not raise himself from his sick bed and attempt to strangle Young Ferdinand. No doubt, however, Arthur’s measured and controlled responses add to the level of bitterness that comes from the pen of Dickens. Ferdinand comments that he would be “greatly vexed if you don’t take the warning by the past and keep away from us.” A subtle warning? Perhaps Ferdinand is too dense to realize what he is saying?

Ferdinand does not care about Doyce’s invention and has no intention of ever starting to have any interest in the humbug idea. Concerning Merdle, Ferdinand says that the next man to come along with a genuine taste for swindling will also succeed. From these first paragraphs of the chapter Dickens has delivered two insights into society. The first is that one should never rely on any government bureaucracy to support an individual’s initiatives or needs. The other is that cons and swindlers will always exist and take advantage of others. As readers we are left with the question as to what is worse and more contemptible. Is it a government that will do nothing to aid the population or crooks and swindlers who do so much damage in a population? Indeed, I think Dickens suggests that these two options are simply opposite sides of the same coin.

Arthur is second visitor is the lawyer Rugg who attempts to convince Arthur to make a concession to public opinion and be moved to the Bench where Arthur’s case will be dealt with as more than simply a person who owns a few pounds to another person. Arthur is, however, resolute. He will not be transfers to the “superior abode” of the Bench. Arthur thinks the Marshalsea is a place of better punishment. Do you think Arthur is being noble, foolish, or simply obstinate in remaining at the Marshalsea?

Arthur’s third visitor of the day (one wonders how tired Arthur must be with all this activity) is a surprise. It is none other than the missing Blandois who is followed by Pancks and Cavalletto. Blandois immediately takes up his usual poise of lounging in the room. Arthur immediately launches into an attack on the character of Blandois and how he has upset his mother and cast “dreadful suspicions” upon the company. We learn that Blandois has been staying in London in disguise. There are many layers to this man. So far he has used three names and assumed different disguises and identities. What evil lurks at the core of his being?

It is clear that Arthur despises Blandois. He demands of Blandois “how you dare direct a suspicion of murder against my mother’s house?” But oh, Blandois is one cold and cruel man. He cannot be intimidated or even upset by Arthur or the situation he finds himself in. I can’t forget the first time we meet Blandois at the beginning of the novel. From that point on Blandois has been cold, detached, and seemingly unable to be ruffled in any way. His languid posture is more telling than the facial contortions he does with his nose and his lips and moustache.

So, let’s see what we can learn about Blandois and his connection to the Clennam household.

he has “a commodity” to sell to Arthur’s mother.

he has “fixed my price” for this commodity.

Arthur’s mother angered Blandois with her “too calm, too stolid, too unmovable attitude.

there is some unexplained connection between Blandois and Flintwinch.

We are told that “the difficulties of a certain contract would be removed by the appearance of a certain party to it.” Wow, that’s mysterious!

Blandois appears to be in total control of the situation and is dictating the events that are unfolding in the jail.

Blandois writes a letter to Mrs Clennam and tells her that she has one week to “unconditionally accept” his offer or to suffer the consequences.

That Mrs Clennam now pay for his lodging and his food for the coming week.

While waiting for a reply from Mrs Clennam, Blandois mentions both Pet and Miss Wade and that he became a spy for Miss Wade and reported to her on the relationship between Pet and Gowan. Flintwinch returns to the group with a response to Blandois’s letter, is embraced by Blandois, and that is followed by Flintwinch chastising Arthur for not ignoring Blandois in the past. Flintwinch hands Arthur a letter from his mother. The contents are severe, cruel, and unfeeling towards her son. Flintwinch then tells Blandois that Mrs Clennam agrees to his terms.

As this most confusing chapter ends Blandois appears the victor, and Arthur and his mother the losers. The question is, what is it that Blandois holds over their heads? Poor Arthur, he is now alone again in his cell and no doubt even more worn out from all the visitors he has seen in the past few hours.

Chapter 29

A Plea in the Marshalsea

John Chivery Junior: “Tell him,’” repeated John, in a distinct, though quivering voice, “that his little Dorrit sent him her undying love.” Now it’s delivered. “Have I been honourable, sir?”

Clennam wakes the next day feeling very unwell and recognizes that his “dread and hatred of the place [had become] so intense that he felt it a labour to draw his breath in it.” Cavalletto and Pancks were away attempting to help him, the Plornish’s were offering their support, and Young John looked in every day and yet Arthur’s spirits and health diminished greatly. He dozes, dreams, and thinks he smells the aroma of flowers. Then he sees flowers and they seem so beautiful. He sees the figure of a person enter the room. It was Little Dorrit in her old Marshalsea dress. Little Dorrit dropped to her knees “and with her lips raised up to kiss him, and with her tears dropping on him as the rain from Heaven had dropped upon the flowers, Little Dorrit, a living presence, called him by his name.”

Now we must pause. What follows in the remainder of this chapter will, for many readers, be melodrama raised to great heights. For others, this reunion will be a conformation of a love that has existed for many chapters. For still others, it might make a reader somewhat uncomfortable when we realize that there is an age difference of slightly more than 20 years between Arthur and Amy. Such a difference in age, especially as Little Dorrit asks Arthur to call her by that name, and the fact that Arthur is desperately poor, may lead us to have a very bad feeling about Arthur. I will attempt to briefly report the facts of the chapter objectively. I will then present my opinion with the hope it will stimulate some debate. Oh to be with you all in The George for a spirited evening of discussion!

Arthur tells Little Dorrit that he has thought about her every minute since coming to the Marshalsea. Cynics might observe that was easy since he is in the same jail cell as the Dorrit’s. Dickens tells us that Amy “looked something more womanly than when she had gone away, and the ripening touch of the Italian sun was visible upon her face.” She and Maggy begin to freshen up the room and make it more comfortable for Arthur. Amy slips into her old role with her father and does not move from her position unless it is to help Arthur and offer him comfort. Amy tells Arthur that she will not leave England again.

Amy offers Arthur all her money and tells Arthur she will never forget how he supported her and her family in the past. As the chapter progresses there is a give and take between them, with Amy insisting she will stand by Arthur and Arthur insisting she must strike out on her own life. Within these two positions I found one statement to stand out. At one point Arthur says “ if I had been known and told you that I loved and honoured you, not as the poor child I used to call you, but as a woman whose true hand would raise me high above myself and make me a far happier and better man; if I had so used the opportunity there is no recalling… but, as it is, I must never touch it yet, never!”

Maggy, showing a very rational mind, tells Amy to get Arthur to a hospital. Maggy also invokes the story of the Princess. The evening bell of the Marshalsea rings and thus Amy and Maggy must leave for the night. Shortly after Arthur hears quiet steps and Young John comes into Arthur’s room to inform him that he has shown Little Dorrit safely to her hotel. On the way to the hotel we learn that Little Dorrit asked Young John to look after Arthur when she was not at the Marshalsea. John tells Arthur that he will honour Little Dorrit’s request. Her last request to John was to send Arthur her undying love. With that, John extends his hand to Arthur and makes the solemn promise that “I’ll stand by you forever.“

And so the chapter ends. Arthur and Amy have spoken. Their minds and their hearts are now as one. We cannot forget John Junior who, in an act of love and sacrifice, has now offered Arthur his hand in friendship and made a solemn promise that while he once loved Amy he now has transferred his loyalty to both Arthur and Little Dorrit. Is it too much to wonder whether John’s last name, which is Chivery, is not a derivation of chivalry? There was a time when Knights would do anything for their ladies and do everything to maintain their own honour. Amy once stood by a window of a room that imprisoned her and talked about a Princess. John has made a chivalric sacrifice for the woman he loved, and we must not forget that the name Arthur finds a very special place in the minds of the English medieval tradition.

Thoughts

We are getting very close to the end of this novel. Dickens and Hablot Browne worked very carefully on this novel. There is no question that Dickens described Amy as being petite in stature. Time and time again we have encountered the word “little.” If we look at Browne’s illustrations, however, we will see Amy portrayed as looking like a young woman, not a girl. Dickens would have seen most, if not all, of these illustrations prior to their being produced in the various parts of the publication. I wonder to what extent we can blend the written word descriptions of Little Nell with the drawn representations of her in order to come to some understanding of how Dickens envisioned her?

A Plea in the Marshalsea

John Chivery Junior: “Tell him,’” repeated John, in a distinct, though quivering voice, “that his little Dorrit sent him her undying love.” Now it’s delivered. “Have I been honourable, sir?”

Clennam wakes the next day feeling very unwell and recognizes that his “dread and hatred of the place [had become] so intense that he felt it a labour to draw his breath in it.” Cavalletto and Pancks were away attempting to help him, the Plornish’s were offering their support, and Young John looked in every day and yet Arthur’s spirits and health diminished greatly. He dozes, dreams, and thinks he smells the aroma of flowers. Then he sees flowers and they seem so beautiful. He sees the figure of a person enter the room. It was Little Dorrit in her old Marshalsea dress. Little Dorrit dropped to her knees “and with her lips raised up to kiss him, and with her tears dropping on him as the rain from Heaven had dropped upon the flowers, Little Dorrit, a living presence, called him by his name.”

Now we must pause. What follows in the remainder of this chapter will, for many readers, be melodrama raised to great heights. For others, this reunion will be a conformation of a love that has existed for many chapters. For still others, it might make a reader somewhat uncomfortable when we realize that there is an age difference of slightly more than 20 years between Arthur and Amy. Such a difference in age, especially as Little Dorrit asks Arthur to call her by that name, and the fact that Arthur is desperately poor, may lead us to have a very bad feeling about Arthur. I will attempt to briefly report the facts of the chapter objectively. I will then present my opinion with the hope it will stimulate some debate. Oh to be with you all in The George for a spirited evening of discussion!

Arthur tells Little Dorrit that he has thought about her every minute since coming to the Marshalsea. Cynics might observe that was easy since he is in the same jail cell as the Dorrit’s. Dickens tells us that Amy “looked something more womanly than when she had gone away, and the ripening touch of the Italian sun was visible upon her face.” She and Maggy begin to freshen up the room and make it more comfortable for Arthur. Amy slips into her old role with her father and does not move from her position unless it is to help Arthur and offer him comfort. Amy tells Arthur that she will not leave England again.

Amy offers Arthur all her money and tells Arthur she will never forget how he supported her and her family in the past. As the chapter progresses there is a give and take between them, with Amy insisting she will stand by Arthur and Arthur insisting she must strike out on her own life. Within these two positions I found one statement to stand out. At one point Arthur says “ if I had been known and told you that I loved and honoured you, not as the poor child I used to call you, but as a woman whose true hand would raise me high above myself and make me a far happier and better man; if I had so used the opportunity there is no recalling… but, as it is, I must never touch it yet, never!”

Maggy, showing a very rational mind, tells Amy to get Arthur to a hospital. Maggy also invokes the story of the Princess. The evening bell of the Marshalsea rings and thus Amy and Maggy must leave for the night. Shortly after Arthur hears quiet steps and Young John comes into Arthur’s room to inform him that he has shown Little Dorrit safely to her hotel. On the way to the hotel we learn that Little Dorrit asked Young John to look after Arthur when she was not at the Marshalsea. John tells Arthur that he will honour Little Dorrit’s request. Her last request to John was to send Arthur her undying love. With that, John extends his hand to Arthur and makes the solemn promise that “I’ll stand by you forever.“

And so the chapter ends. Arthur and Amy have spoken. Their minds and their hearts are now as one. We cannot forget John Junior who, in an act of love and sacrifice, has now offered Arthur his hand in friendship and made a solemn promise that while he once loved Amy he now has transferred his loyalty to both Arthur and Little Dorrit. Is it too much to wonder whether John’s last name, which is Chivery, is not a derivation of chivalry? There was a time when Knights would do anything for their ladies and do everything to maintain their own honour. Amy once stood by a window of a room that imprisoned her and talked about a Princess. John has made a chivalric sacrifice for the woman he loved, and we must not forget that the name Arthur finds a very special place in the minds of the English medieval tradition.

Thoughts

We are getting very close to the end of this novel. Dickens and Hablot Browne worked very carefully on this novel. There is no question that Dickens described Amy as being petite in stature. Time and time again we have encountered the word “little.” If we look at Browne’s illustrations, however, we will see Amy portrayed as looking like a young woman, not a girl. Dickens would have seen most, if not all, of these illustrations prior to their being produced in the various parts of the publication. I wonder to what extent we can blend the written word descriptions of Little Nell with the drawn representations of her in order to come to some understanding of how Dickens envisioned her?

Peter wrote: "Chapter 27

Peter wrote: "Chapter 27The Pupil of the Marshalsea

“This was native delicacy in Mr. Chivery - true politeness; though his exterior had very much of the turnkey about it, and not the least of a gentleman.”

..."

Earlier I had asked if Arthur didn't make a prize husband for Amy because she could spend all her time assisting him in slaying his demons. But if that is what Amy is looking for in a man, then who better than John Jr.? Hmmm . . .

Didn't Arthur refuse to permit himself to think of Amy as a wife because of the age difference? Or was it because he didn't think he was good enough for her? He's done so little with his life and she so much with hers. Then again, if his parent's marriage is the only experience he has of marriage and love, then how could he recognize Amy's overtures as overtures?

Arthur is a product of his strict upbringing, of his father and mother. His mother, an uncompromising, unforgiving, and bitter parent and wife, is all will and no compassion. She, and her values, haunt him. Any change in Arthur's attitude towards Amy represents a change in his attitude towards his mother, an unshackling of the chains that bind him -- liberation. Amy is Arthur's liberator. See, Tristram? Amy succeeds again. 😇

I had always thought Merdle despised aristocrats and the Gentleman's society. That's why he lost no sleep relieving them of their money. IIRC, he did balk a bit before taking Dorrit's money. Dorrit didn't fit the profile. I always thought Madoff justified what he did for the same reasons.

Xan wrote: "Peter wrote: "Chapter 27

The Pupil of the Marshalsea

“This was native delicacy in Mr. Chivery - true politeness; though his exterior had very much of the turnkey about it, and not the least of ..."

Hi Xan

Arthur was certainly aware of the difference in age between Amy and himself and did see this as a factor in any evolving relationship. I often think that Arthur’s long denial of his true feelings towards Amy was meant by Dickens to keep the reader hanging on. As Dickens’s plots go, I think Amy and Arthur are the ones most destined for each other. Considering the number of disastrous marriages in the novel we need some counterbalance.

As to the issue of their age difference I think we need to remember that it was not a major issue in the middle class and especially the upper classes in England at the time. Dickens himself, during the writing of LD, was on the cusp of erecting a wall between his bedroom and Catherine’s. We are about a year away from Dickens leaving his wife and beginning his long relationship with Ellen Turnan who was much younger.

Amy as Arthur’s liberator. I like that take on the plot.

The Pupil of the Marshalsea

“This was native delicacy in Mr. Chivery - true politeness; though his exterior had very much of the turnkey about it, and not the least of ..."

Hi Xan

Arthur was certainly aware of the difference in age between Amy and himself and did see this as a factor in any evolving relationship. I often think that Arthur’s long denial of his true feelings towards Amy was meant by Dickens to keep the reader hanging on. As Dickens’s plots go, I think Amy and Arthur are the ones most destined for each other. Considering the number of disastrous marriages in the novel we need some counterbalance.

As to the issue of their age difference I think we need to remember that it was not a major issue in the middle class and especially the upper classes in England at the time. Dickens himself, during the writing of LD, was on the cusp of erecting a wall between his bedroom and Catherine’s. We are about a year away from Dickens leaving his wife and beginning his long relationship with Ellen Turnan who was much younger.

Amy as Arthur’s liberator. I like that take on the plot.

I always thought in the upper middle-class and middle class, where women permitted to do anything but look good, parents were forced to marry daughters off to older men. If you were responsible parents, you had to make sure her suitor was well-off enough to provide for her throughout her life. That limited the field to the financially established, older men.

I always thought in the upper middle-class and middle class, where women permitted to do anything but look good, parents were forced to marry daughters off to older men. If you were responsible parents, you had to make sure her suitor was well-off enough to provide for her throughout her life. That limited the field to the financially established, older men.

Xan wrote: "I always thought in the upper middle-class and middle class, where women permitted to do anything but look good, parents were forced to marry daughters off to older men. If you were responsible par..."

Hi Xan

Yes. Middle and upper class women and men were much more a commodity to each other in the 19c than now.

There must be a criticism/analysis of how 19c marriages were arranged, conducted, and unfolded somewhere. It would be fascinating to read. Has any Curiosity come across any good book/article on the subject?

Hi Xan

Yes. Middle and upper class women and men were much more a commodity to each other in the 19c than now.

There must be a criticism/analysis of how 19c marriages were arranged, conducted, and unfolded somewhere. It would be fascinating to read. Has any Curiosity come across any good book/article on the subject?

I can't speak for Arthur, but I'M exhausted after all of those visitors, so I must assume he was, as well.

I can't speak for Arthur, but I'M exhausted after all of those visitors, so I must assume he was, as well. John Chivery - Poor John. Perhaps he could have gotten over his love for Amy and moved on if Arthur hadn't ended up at the Marshalsea as a constant reminder. Arthur, whose "honor" is shown by the way humbles himself at the Marshalsea instead of following Rugg's advice, all in order to do right by Doyce, isn't thinking about how his choices are affecting others, like Amy and John. In answer to Peter's questions - yes, I thought this "revelation" took much too long, and it's about time somebody smacked Arthur upside the head so he'd open his eyes and see what is plain to everyone else.

Ferdinand Barnacle (what a name!) - Peter found him totally obnoxious, and he is. But I also found him winsome and amusing. The entire scene seemed unnecessary, though. There was no reason for this visit.

Peter wrote: one should never rely on any government bureaucracy to support an individual’s initiatives or needs It's one thing not to support initiatives. It's another to actively throw up barriers by strangling people with regulations preventing individual initiative. I'm reminded of the recent story I heard about Rod Stewart: people's cars kept bottoming out from the potholes on the street in front of his house. Calls to the "circumlocution office" netted no results, so Stewart went out with buckets of gravel and filled them himself. Instead of being lauded for taking the bull by the horns, the municipality fined him for doing it without permission. The Barnacles at work!

The Plornishes - they are a refreshing respite from the heaviness of this story.

Rugg - I don't really understand what the business about the "Bench" is. I imagine it's something like the difference between the Marshalsea v. being sentenced to serve time in what they used to call white collar, "country club" type prisons, so non-violent offenders didn't get thrown together with murderers. Whatever it is, I don't suppose a complete understanding is critical to the plot.

Blandois/Rigaud - This chapter gave me a headache. Rigaud dances around things without ever coming to the point, and his little hints are exhausting. Out with it, man! Peter, I appreciate your summation of the chapter, which didn't hold many answers, but at least gave us what little information there is in a straightforward way. Regarding your observation about exteriors/appearances, I'm quite fatigued by Rigaud's constant insistence that he's a gentleman.

Amy - First, the dress. Oh, come on, Amy (and Dickens)! First of all, that dress would certainly no longer fit. Amy's diet over the last year or whatever it's been has surely caused a change in her figure. I'll blame that one on Dickens, who probably just didn't put that much thought into it. But even if the old rags did still fit, I find this choice preposterous. Knowing Amy, even her "fine" clothes are utilitarian and humble in appearance. One could even say she's being insulting to those who are truly poor and would gladly trade their rags for a decent suit of clothes.

I'm less creeped out by the difference in Arthur and Amy's ages than I am in the fact that Amy has daddy issues, and is treating Arthur just the way she treated William. It's not a healthy, mature relationship we're seeing here. But then, her relationship with her father was never healthy, either. I can't help but wonder if this is the type of relationship Charles had with Ellen. Ick. I kind of want to give Arthur points for not taking Amy's money. At least he has that much self-respect. In theory, anyhow. In reality, though, what good is this really doing anyone? They all suffer. Take it as a loan, then work hard to pay it back with interest before you ask for her hand in marriage. Win-win.

And that brings us to Maggy - Dickens has been hinting that Arthur is not thriving in this environment, and we know he's not eating well, if at all. Now we have simpleton Maggy stating that he should be taken to a hospital. I can see what's coming, and (in reference to last week's thread) I'm not feeling at all clever about it, but annoyed by what is surely going to occur in the remaining chapters. Formulaic Dickens, I'm afraid.

Aside: have any of you seen Terminator II? I was always impressed at how Sarah Connor started in the first movie slender, but, well... soft, for lack of a better term. Then she uses her time locked up - in solitary confinement, no less - to train and get in fighting shape - hard as a rock! The transformation was astounding. Arthur should have taken some tips from her, instead of just sitting there having a pity party for himself and wasting away. I find his whole response to this situation impractical and a bit selfish. Which is interesting, since I think that's the exact opposite of what Dickens intended.

Mary Lou wrote: "I can't speak for Arthur, but I'M exhausted after all of those visitors, so I must assume he was, as well.

John Chivery - Poor John. Perhaps he could have gotten over his love for Amy and moved o..."

Mary Lou

It is always a delight to read your comments. They make me both chuckle and have a better understanding of what is going on in the chapters under discussion.

I do have sympathy for John at this point in the novel. His character has grown on me. I see him now as a type of Knight errant. Do you think there is anything in the name Chivery to suggest chivalry? That idea keeps rattling around in my head.

The visit of Ferdinand to Arthur was funny in a depressing kind of way. I can picture the first readers of this novel gathered at their local giving their own examples of the horrors encountered dealing with the government. What a great anecdote about Rod Stewart.

As for Amy having “daddy issues” I agree with you. It seems to me that in the last couple of novels and this one Dickens has offered more interesting and in depth psychological issues. Lady Dedlock, Esther, Miss Wade, Amy and her father, Arthur and his mother etc. While these characters may not be as subtly drawn as those in modern novels, I see Dickens pushing the edges of psychological realism in his characters much more.

We seem to have our formulaic Dickens and a newly emerging psychological type of character appearing in the same novel.

John Chivery - Poor John. Perhaps he could have gotten over his love for Amy and moved o..."

Mary Lou

It is always a delight to read your comments. They make me both chuckle and have a better understanding of what is going on in the chapters under discussion.

I do have sympathy for John at this point in the novel. His character has grown on me. I see him now as a type of Knight errant. Do you think there is anything in the name Chivery to suggest chivalry? That idea keeps rattling around in my head.

The visit of Ferdinand to Arthur was funny in a depressing kind of way. I can picture the first readers of this novel gathered at their local giving their own examples of the horrors encountered dealing with the government. What a great anecdote about Rod Stewart.

As for Amy having “daddy issues” I agree with you. It seems to me that in the last couple of novels and this one Dickens has offered more interesting and in depth psychological issues. Lady Dedlock, Esther, Miss Wade, Amy and her father, Arthur and his mother etc. While these characters may not be as subtly drawn as those in modern novels, I see Dickens pushing the edges of psychological realism in his characters much more.

We seem to have our formulaic Dickens and a newly emerging psychological type of character appearing in the same novel.

Amy's daddy issues are immense indeed. And what else could they be, with the father she had? Her ending up with Arthur might be giving her the chance of having a do-over-father. Someone who does love and appreciate her for what she does for him? For that I do think he should be able to get out of the Marshallsea somehow, to be a bigger contrast to her father who couldn't - not really, not for decades. In my eyes Amy and Arthur - or Amy and any man she would marry - would never be equals though. Amy is too subservient to be ever equal and not daddied by any man she marries, even if he were 23 years her junior instead of her senior.

Mary Lou wrote: "I kind of want to give Arthur points for not taking Amy's money. At least he has that much self-respect."

Mary Lou wrote: "I kind of want to give Arthur points for not taking Amy's money. At least he has that much self-respect."I can't say I feel the same on this--sheesh, just take the money, Arthur, and cut it out with the dramatic self-sacrifice.

Amy-Arthur may be my least favorite Dickens couple. I can't imagine either of them treating themselves to even so much as an ice cream cone. It's all duty and sacrifice, all the time.

John Chivery, now, him I like. He is also all duty and sacrifice, but his sacrifice is 1) asked for, and 2) actually useful. I feel like Arthur's and Amy's sacrifices serve little purpose but exalting their own holiness. Though I guess Amy does take good care of her brother who--shockingly!--appears to appreciate it.

Also I am grateful to John for writing epitaphs that had me laughing every time he got a chapter to himself.

Mary Lou wrote: "Blandois/Rigaud - This chapter gave me a headache. Rigaud dances around things without ever coming to the point, and his little hints are exhausting. Out with it, man! Peter, I appreciate your summation of the chapter, which didn't hold many answers, but at least gave us what little information there is in a straightforward way."

Mary Lou wrote: "Blandois/Rigaud - This chapter gave me a headache. Rigaud dances around things without ever coming to the point, and his little hints are exhausting. Out with it, man! Peter, I appreciate your summation of the chapter, which didn't hold many answers, but at least gave us what little information there is in a straightforward way."Agreed! Very helpful.

Amy - Arthur have been a possible throughout the book. We talked about it much earlier. Now at the end, it is just one more romance love story -- I think the ending is so weak. The house blows up - gets the bad guy, one escapes, the mother confesses

Amy - Arthur have been a possible throughout the book. We talked about it much earlier. Now at the end, it is just one more romance love story -- I think the ending is so weak. The house blows up - gets the bad guy, one escapes, the mother confessesBut I never found out WHO Arthur's mother was? A trashy woman, according to his fake mother. And why did the fake mother take on Arthur as a child? Because the old man supported her? Why not support the real mother? I am missing something here. And Amy and Arther take care of her sister's children! Sob. Isn't this supposed to be a Harlequin? A&A fade off into the sunset. Dickens failed me at the end. Maybe that is why I could not remember much of what I read 50 years ago.

peace, janz

A friendly reminder, Janz, to keep the comments confined to the chapters in the heading, and those that came before. No spoilers. :-)

A friendly reminder, Janz, to keep the comments confined to the chapters in the heading, and those that came before. No spoilers. :-)

Oops - Sorry - read something earlier that I interpreted as ending the discussions. Please everyone - do not read the above unless you have finished the book. I will not do this again. peace, janz

Oops - Sorry - read something earlier that I interpreted as ending the discussions. Please everyone - do not read the above unless you have finished the book. I will not do this again. peace, janz

Xan wrote: "See, Tristram? Amy succeeds again."

Does she really, though? On the one hand, she may in that she gets what she wants: She finally has someone else to sacrifice herself to in order to "help" him. Just the way she did with her father. On the other hand, however, it might be asked if she gets what she needs and what is good for her: I think Amy would be a rather sticky and depressing person to have around me, with all her subservient and self-denying love. It might suit Arthur but it will certainly not make a man out of him. Like Julie, I cannot see them as a wholesome couple because both reinforce each other's psychological problems.

Apart from that, I cannot say that I particularly like Arthur: He is so obsessed with his own "duty" that he does not act in common sense. And, what is even more annoying, he never thinks twice about using Flora's soft spot for him in order to further his own means. Need some new place for Amy to work at? Just visit Flora. Need some pretext to get a talk with Affery in private? Just use Flora. Nevertheless, he never goes to see Flora simply for seeing Flora. The more I am writing about him the more I hate the very guts of this whining guy.

Does she really, though? On the one hand, she may in that she gets what she wants: She finally has someone else to sacrifice herself to in order to "help" him. Just the way she did with her father. On the other hand, however, it might be asked if she gets what she needs and what is good for her: I think Amy would be a rather sticky and depressing person to have around me, with all her subservient and self-denying love. It might suit Arthur but it will certainly not make a man out of him. Like Julie, I cannot see them as a wholesome couple because both reinforce each other's psychological problems.

Apart from that, I cannot say that I particularly like Arthur: He is so obsessed with his own "duty" that he does not act in common sense. And, what is even more annoying, he never thinks twice about using Flora's soft spot for him in order to further his own means. Need some new place for Amy to work at? Just visit Flora. Need some pretext to get a talk with Affery in private? Just use Flora. Nevertheless, he never goes to see Flora simply for seeing Flora. The more I am writing about him the more I hate the very guts of this whining guy.

Mary Lou wrote: "I'm quite fatigued by Rigaud's constant insistence that he's a gentleman."

It is as tiresome as the constant mention of Carker's teeth but I think it does serve a certain purpose: We all know that for all his pretensions and claims, Blandois is no gentleman at all and that we cannot be even sure that one of the three names by which he goes in this novel is his real one. He is simply a scoundrel and a self-serving soldier of fortune. His constant claim to being a gentleman may make us find parallels with other people in this novel who lay claim to being gentlemen and then are not. Just listen to the Chief Butler ;-)

It is as tiresome as the constant mention of Carker's teeth but I think it does serve a certain purpose: We all know that for all his pretensions and claims, Blandois is no gentleman at all and that we cannot be even sure that one of the three names by which he goes in this novel is his real one. He is simply a scoundrel and a self-serving soldier of fortune. His constant claim to being a gentleman may make us find parallels with other people in this novel who lay claim to being gentlemen and then are not. Just listen to the Chief Butler ;-)

Tristram wrote: "His constant claim to being a gentleman may make us find parallels with other people in this novel who lay claim to being gentlemen and then are not. Just listen to the Chief Butler ;-)."

Tristram wrote: "His constant claim to being a gentleman may make us find parallels with other people in this novel who lay claim to being gentlemen and then are not. Just listen to the Chief Butler ;-)."Who *are* the gentlemen in this novel?

I think it's just Clennam? Nobody thinks of Doyce as a gentleman.

Oh, and Minipet's dad, too.

The gentlemen are not exactly thriving in this book. Then again, nobody's thriving much at this darkness-before-the-dawn point in the story, except the Circumlocution Office?

Gowan and the Barnicle Bunch are "gentlemen" but certainly not worthy of the designation by today's definition.

Gowan and the Barnicle Bunch are "gentlemen" but certainly not worthy of the designation by today's definition.

Tristram wrote: "Xan wrote: "See, Tristram? Amy succeeds again."

Does she really, though? On the one hand, she may in that she gets what she wants: She finally has someone else to sacrifice herself to in order to ..."

Ah, duty versus common sense. That is a huge hurdle to approach. I agree that on the one hand Arthur does stretch the idea of falling one one’s sword because of errors both real or presumed in his past or committed by himself in the present to the limit.

On the other hand, I find him to be a very noble man. In fact, I admire him. As we look around us today how many people have such a moral compass? He admits to and is willing to pay financially, legally and morally for his decisions and actions. Merdle is a cheat. Merdle takes the “easy” way out. Arthur, however, will accept the consequences of his actions. He will pay his debt to society. It would be easy for him to blame Merdle, then turn his back on Doyce. Surely, seeing how the Circumlocution Office and the Barnacles operate, and the financial ruin caused by Merdle in society would be enough motivation for Arthur to decide to join the cheats and corruption he sees around himself. That’s the easy way out, the best motivation since it is what he sees all around himself.

He does not. Is Arthur too good or is he what we wish others would be more like? What is it that Doyce, young John Chivery, Miss Wade and, of course, Amy all come to see, realize, and appreciate in Arthur?

Perhaps Arthur, in spite of his apparent blandness and boredom, is what we all wish to be true, or at least possible in people. We all love Pickwick because he is so human, so funny, so bumbling, so intent on being good. Mr Pickwick is who we want to cheer on, to be friends with, indeed, even to emulate. Sadly, people like him are few and far between. I hold out the possibility that Mr Pickwick even exists. As for Arthur, perhaps he is what Pickwick would be like, would have to be like in order to survive with dignity in the world.

Does she really, though? On the one hand, she may in that she gets what she wants: She finally has someone else to sacrifice herself to in order to ..."

Ah, duty versus common sense. That is a huge hurdle to approach. I agree that on the one hand Arthur does stretch the idea of falling one one’s sword because of errors both real or presumed in his past or committed by himself in the present to the limit.

On the other hand, I find him to be a very noble man. In fact, I admire him. As we look around us today how many people have such a moral compass? He admits to and is willing to pay financially, legally and morally for his decisions and actions. Merdle is a cheat. Merdle takes the “easy” way out. Arthur, however, will accept the consequences of his actions. He will pay his debt to society. It would be easy for him to blame Merdle, then turn his back on Doyce. Surely, seeing how the Circumlocution Office and the Barnacles operate, and the financial ruin caused by Merdle in society would be enough motivation for Arthur to decide to join the cheats and corruption he sees around himself. That’s the easy way out, the best motivation since it is what he sees all around himself.

He does not. Is Arthur too good or is he what we wish others would be more like? What is it that Doyce, young John Chivery, Miss Wade and, of course, Amy all come to see, realize, and appreciate in Arthur?

Perhaps Arthur, in spite of his apparent blandness and boredom, is what we all wish to be true, or at least possible in people. We all love Pickwick because he is so human, so funny, so bumbling, so intent on being good. Mr Pickwick is who we want to cheer on, to be friends with, indeed, even to emulate. Sadly, people like him are few and far between. I hold out the possibility that Mr Pickwick even exists. As for Arthur, perhaps he is what Pickwick would be like, would have to be like in order to survive with dignity in the world.

I agree, Peter. And Pickwick is a great example. But Pickwick has characteristics that Arthur send to lack. Namely, a sense of humor, a temper, and passionate pursuits. These things make him more interesting and likeable, while still an honorable man with strong ethics and morals. In fact, Dickens' first hero may well have been his best.

I agree, Peter. And Pickwick is a great example. But Pickwick has characteristics that Arthur send to lack. Namely, a sense of humor, a temper, and passionate pursuits. These things make him more interesting and likeable, while still an honorable man with strong ethics and morals. In fact, Dickens' first hero may well have been his best.

Mary Lou wrote: "I agree, Peter. And Pickwick is a great example. But Pickwick has characteristics that Arthur send to lack. Namely, a sense of humor, a temper, and passionate pursuits. These things make him more i..."

Yes.

Pickwick is the person I would most like to meet from any Dickens novel.

Dostoevsky once said that there were very few good people in the world. Two that he specifically mentioned were Christ and Mr. Pickwick.

Yes.

Pickwick is the person I would most like to meet from any Dickens novel.

Dostoevsky once said that there were very few good people in the world. Two that he specifically mentioned were Christ and Mr. Pickwick.

Peter wrote: "Is Arthur too good or is he what we wish others would be more like?"

Peter wrote: "Is Arthur too good or is he what we wish others would be more like?"Neither? I find him too interfering. There's not a problem out there he's not prepared to jump in and solve (sometimes badly), and often it feels excessive. So far in this book, whose business has not been Arthur's business?

But I expect that's the definition of gentlemanliness that this book is encouraging. The gentleman takes gracious responsibility for his subordinates. I am thinking especially about this book coming after Hard Times with its indictment of the laissez-fairer leave-it-alone brand of interpersonal relationships. Arthur is at the opposite extreme. He won't leave anyone alone. I can see why Dickens would think this is a good thing, but not everyone needs or wants a substitute dad.

Though as people have already commented, maybe Amy does.

Julie wrote: "Peter wrote: "Is Arthur too good or is he what we wish others would be more like?"

Neither? I find him too interfering. There's not a problem out there he's not prepared to jump in and solve (some..."

Hi Julie

Yes. Good point. Arthur is certainly on the other edge of the spectrum from characters in HT. Dickens is very often writer of extremes.

By the way, how was Ireland?

Neither? I find him too interfering. There's not a problem out there he's not prepared to jump in and solve (some..."

Hi Julie

Yes. Good point. Arthur is certainly on the other edge of the spectrum from characters in HT. Dickens is very often writer of extremes.

By the way, how was Ireland?

Peter wrote: "By the way, how was Ireland?"

Peter wrote: "By the way, how was Ireland?"I'm still here! I'm running a 5-week program--the first 3 weeks I was teaching but the last 2 weeks of the program, now, are Irish language immersion, which I can't teach. So I snapped up the opportunity to take the class along with my students. I haven't studied a language for about a quarter century and then it was Spanish, which is comparatively close to English, so this is a challenge for sure. But it is *very* fun to be a student again and watch someone else do the teaching--and I find as a student rather than a teacher I have a little more time to get caught up on my Dickens. :)

Also it's beautiful--I've never come across a landscape like this and am enjoying my time here. (Though I do begin to miss my big northwestern trees and mountains.)

Peter wrote: "Mary Lou wrote: "I agree, Peter. And Pickwick is a great example. But Pickwick has characteristics that Arthur send to lack. Namely, a sense of humor, a temper, and passionate pursuits. These thing..."

I'd rather be Pickwick than Clennam because I think one can get through life without moping and the danger of self-pity just by regarding it as a sort of game even if it is a mug's game. I would not care to meet Clennam at all but rather travel around Europe in the company of Pickwick. And then there is the creepy streak in Clennam which makes him stalk Amy and bury his nose into her affairs sensing that she is all too ready to respond to his interest.

Turn it as you will, Clennam does not sit straight with me at all.

I'd rather be Pickwick than Clennam because I think one can get through life without moping and the danger of self-pity just by regarding it as a sort of game even if it is a mug's game. I would not care to meet Clennam at all but rather travel around Europe in the company of Pickwick. And then there is the creepy streak in Clennam which makes him stalk Amy and bury his nose into her affairs sensing that she is all too ready to respond to his interest.

Turn it as you will, Clennam does not sit straight with me at all.

Julie wrote: "But it is *very* fun to be a student again"

Words that not only would I never say, but have never even entered my head before. I hope you are having a wonderful time Julie. Well, except for all that school stuff of course. :-)

Words that not only would I never say, but have never even entered my head before. I hope you are having a wonderful time Julie. Well, except for all that school stuff of course. :-)

Amy and Arthur and the 20 year age difference. This has been in my mind since the beginning of the book because of my family. My dad was 16 years older than my mom. My husband is 18 years older than I am. My son-in-law is 20 years older than my daughter. I told my granddaughter not long ago that she better soon start looking for a future husband, since the family law seems to be to increase the age difference by two years every generation, so she better start looking before all the possible husbands for her out there are too old to marry her. She yelled something like "Yuk, Nan be quiet!" Oh, she's 13 now.

As for my dad, he told me when my mom died that he married a woman so much younger than him so he would have someone to take care of him when he got old, and now he was all alone anyway. He lived twenty years more than my mom did. He was married once before and his first wife's name was Georgina, but everyone just called her Gene, and my mother's name was Jean. Dad said he did that so he would never get in trouble if he called my mom by the "wrong" name.

As for my dad, he told me when my mom died that he married a woman so much younger than him so he would have someone to take care of him when he got old, and now he was all alone anyway. He lived twenty years more than my mom did. He was married once before and his first wife's name was Georgina, but everyone just called her Gene, and my mother's name was Jean. Dad said he did that so he would never get in trouble if he called my mom by the "wrong" name.

And I now just realized I don't have the illustrations yet for this week, so I'm off to find them.

Posting illustrations is not going well, please be patient, one of us should be. The computer refuses to let me do anything, it just keeps telling me to reload for the 100th time, so I'm doing this on my tablet which takes longer. This day just keeps getting better and better. 😤😓

At Mr. John Chivery's Tea-Table

Book II Chapter 27

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"Young John was some time absent, and, when he came back, showed that he had been outside by bringing with him fresh butter in a cabbage leaf, some thin slices of boiled ham in another cabbage leaf, and a little basket of water-cresses and salad herbs. When these were arranged upon the table to his satisfaction, they sat down to tea.

Clennam tried to do honour to the meal, but unavailingly. The ham sickened him, the bread seemed to turn to sand in his mouth. He could force nothing upon himself but a cup of tea.

"Try a little something green," said Young John, handing him the basket.

He took a sprig or so of water-cress, and tried again; but the bread turned to a heavier sand than before, and the ham (though it was good enough of itself) seemed to blow a faint simoom of ham through the whole Marshalsea.

"Try a little more something green, sir," said Young John; and again handed the basket.

It was so like handing green meat into the cage of a dull imprisoned bird, and John had so evidently brought the little basket as a handful of fresh relief from the stale hot paving-stones and bricks of the jail, that Clennam said, with a smile, "It was very kind of you to think of putting this between the wires; but I cannot even get this down to-day."

As if the difficulty were contagious, Young John soon pushed away his own plate, and fell to folding the cabbage-leaf that had contained the ham. When he had folded it into a number of layers, one over another, so that it was small in the palm of his hand, he began to flatten it between both his hands, and to eye Clennam attentively.

"I wonder," he at length said, compressing his green packet with some force, "that if it's not worth your while to take care of yourself for your own sake, it's not worth doing for some one else's."

"Truly," returned Arthur, with a sigh and a smile, "I don't know for whose."

Commentary:

In love with Amy Dorrit for years, John Chivery naturally resents Arthur Clennam, for John sees what Arthur does not: that Amy is in love with Arthur. Ironically, Arthur Clennam, but lately arrived as an insolvent debtor at the Marshalsea, has been unaware of John Chivery's resentment, a predisposition that Phiz's illustration of the turnkey's son trying to engage the self-absorbed, disheveled Arthur Clennam at the tea-table in his own, tastefully decorated room above one of the prison's gates, does not communicate.

At Mr. John Chivery's Tea-Table

Book II Chapter 27

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"Young John was some time absent, and, when he came back, showed that he had been outside by bringing with him fresh butter in a cabbage leaf, some thin slices of boiled ham in another cabbage leaf, and a little basket of water-cresses and salad herbs. When these were arranged upon the table to his satisfaction, they sat down to tea.

Clennam tried to do honour to the meal, but unavailingly. The ham sickened him, the bread seemed to turn to sand in his mouth. He could force nothing upon himself but a cup of tea.

"Try a little something green," said Young John, handing him the basket.

He took a sprig or so of water-cress, and tried again; but the bread turned to a heavier sand than before, and the ham (though it was good enough of itself) seemed to blow a faint simoom of ham through the whole Marshalsea.

"Try a little more something green, sir," said Young John; and again handed the basket.

It was so like handing green meat into the cage of a dull imprisoned bird, and John had so evidently brought the little basket as a handful of fresh relief from the stale hot paving-stones and bricks of the jail, that Clennam said, with a smile, "It was very kind of you to think of putting this between the wires; but I cannot even get this down to-day."

As if the difficulty were contagious, Young John soon pushed away his own plate, and fell to folding the cabbage-leaf that had contained the ham. When he had folded it into a number of layers, one over another, so that it was small in the palm of his hand, he began to flatten it between both his hands, and to eye Clennam attentively.

"I wonder," he at length said, compressing his green packet with some force, "that if it's not worth your while to take care of yourself for your own sake, it's not worth doing for some one else's."

"Truly," returned Arthur, with a sigh and a smile, "I don't know for whose."

Commentary:

In love with Amy Dorrit for years, John Chivery naturally resents Arthur Clennam, for John sees what Arthur does not: that Amy is in love with Arthur. Ironically, Arthur Clennam, but lately arrived as an insolvent debtor at the Marshalsea, has been unaware of John Chivery's resentment, a predisposition that Phiz's illustration of the turnkey's son trying to engage the self-absorbed, disheveled Arthur Clennam at the tea-table in his own, tastefully decorated room above one of the prison's gates, does not communicate.

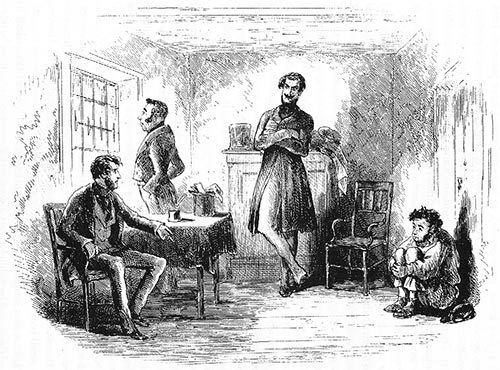

Book II Chapter 27 - Harry Furniss

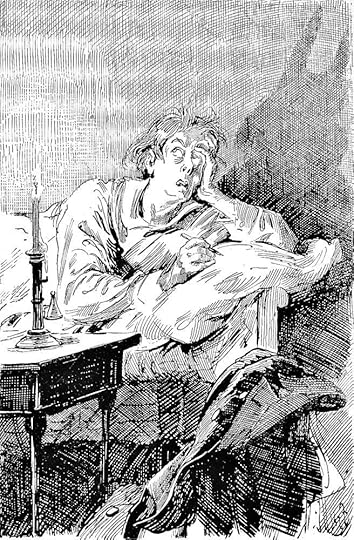

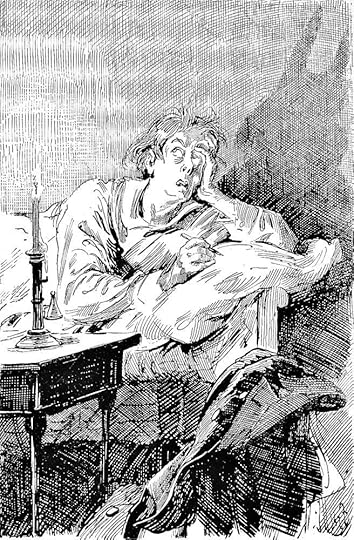

John Chivery Pens His Own Epitaph

Book II Chapter 27

Harry Furniss

Household Edition 1910

Text Illustrated:

"Happily, if it ever had been so, it was over, and better over. Granted that she had loved him, and he had known it and had suffered himself to love her, what a road to have led her away upon — the road that would have brought her back to this miserable place! He ought to be much comforted by the reflection that she was quit of it forever; that she was, or would soon be, married (vague rumours of her father's projects in that direction had reached Bleeding Heart Yard, with the news of her sister's marriage); and that the Marshalsea gate had shut for ever on all those perplexed possibilities of a time that was gone.

Dear Little Dorrit.

Looking back upon his own poor story, she was its vanishing-point. Every thing in its perspective led to her innocent figure. He had travelled thousands of miles towards it; previous unquiet hopes and doubts had worked themselves out before it; it was the centre of the interest of his life; it was the termination of everything that was good and pleasant in it; beyond, there was nothing but mere waste and darkened sky.

As ill at ease as on the first night of his lying down to sleep within those dreary walls, he wore the night out with such thoughts. What time Young John lay wrapt in peaceful slumber, after composing and arranging the following monumental inscription on his pillow —

STRANGER!

RESPECT THE TOMB OF

JOHN CHIVERY, JUNIOR,

WHO DIED AT AN ADVANCED AGE

NOT NECESSARY TO MENTION.

HE ENCOUNTERED HIS RIVAL IN A DISTRESSED STATE,

AND FELT INCLINED

TO HAVE A ROUND WITH HIM;

BUT, FOR THE SAKE OF THE LOVED ONE,

CONQUERED THOSE FEELINGS OF BITTERNESS, AND BECAME

MAGNANIMOUS."

Commentary:

This Dickensian satire of the infatuated, self-absorbed adolescent lover is consistent with such portraits in his earliest sketches, including that of Cymon (the romanticized version of "Simon") in February 1836 farce "The Tuggses at Ramsgate. Young John (the appellation distinguishes him from his father, a Marshalsea turnkey) is a sentimental youth whose love for Amy Dorrit remains unrequited.

John Chivery Pens His Own Epitaph

Book II Chapter 27

Harry Furniss

Household Edition 1910

Text Illustrated:

"Happily, if it ever had been so, it was over, and better over. Granted that she had loved him, and he had known it and had suffered himself to love her, what a road to have led her away upon — the road that would have brought her back to this miserable place! He ought to be much comforted by the reflection that she was quit of it forever; that she was, or would soon be, married (vague rumours of her father's projects in that direction had reached Bleeding Heart Yard, with the news of her sister's marriage); and that the Marshalsea gate had shut for ever on all those perplexed possibilities of a time that was gone.

Dear Little Dorrit.

Looking back upon his own poor story, she was its vanishing-point. Every thing in its perspective led to her innocent figure. He had travelled thousands of miles towards it; previous unquiet hopes and doubts had worked themselves out before it; it was the centre of the interest of his life; it was the termination of everything that was good and pleasant in it; beyond, there was nothing but mere waste and darkened sky.

As ill at ease as on the first night of his lying down to sleep within those dreary walls, he wore the night out with such thoughts. What time Young John lay wrapt in peaceful slumber, after composing and arranging the following monumental inscription on his pillow —

STRANGER!

RESPECT THE TOMB OF

JOHN CHIVERY, JUNIOR,

WHO DIED AT AN ADVANCED AGE

NOT NECESSARY TO MENTION.

HE ENCOUNTERED HIS RIVAL IN A DISTRESSED STATE,

AND FELT INCLINED

TO HAVE A ROUND WITH HIM;

BUT, FOR THE SAKE OF THE LOVED ONE,

CONQUERED THOSE FEELINGS OF BITTERNESS, AND BECAME

MAGNANIMOUS."

Commentary:

This Dickensian satire of the infatuated, self-absorbed adolescent lover is consistent with such portraits in his earliest sketches, including that of Cymon (the romanticized version of "Simon") in February 1836 farce "The Tuggses at Ramsgate. Young John (the appellation distinguishes him from his father, a Marshalsea turnkey) is a sentimental youth whose love for Amy Dorrit remains unrequited.

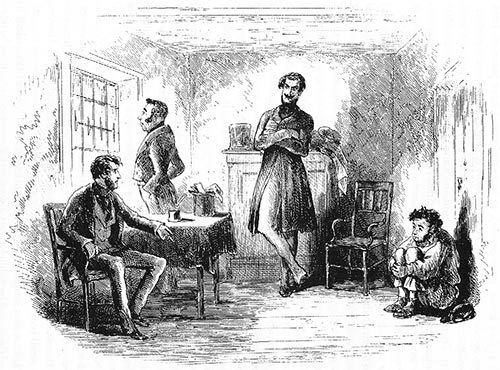

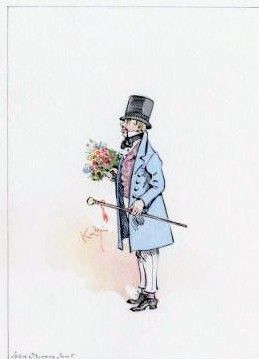

Book II Chapter 28 - James Mahoney

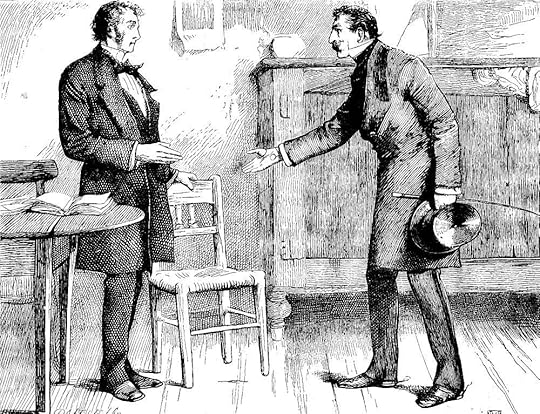

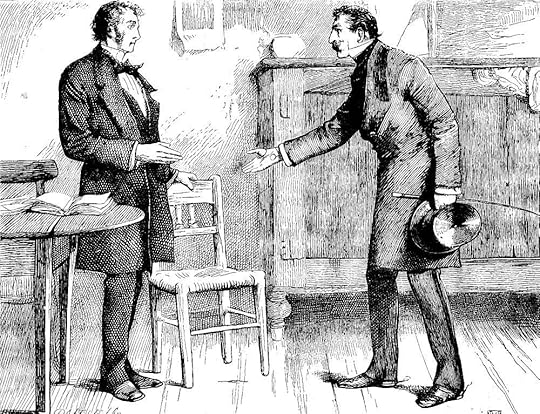

It was the sprightly young Barnacle, Ferdinand

Text Illustrated:

"One day when he might have been some ten or twelve weeks in jail, and when he had been trying to read and had not been able to release even the imaginary people of the book from the Marshalsea, a footstep stopped at his door, and a hand tapped at it. He arose and opened it, and an agreeable voice accosted him with "How do you do, Mr. Clennam? I hope I am not unwelcome in calling to see you."

It was the sprightly young Barnacle, Ferdinand. He looked very good-natured and prepossessing, though overpoweringly gay and free, in contrast with the squalid prison.

"You are surprised to see me, Mr. Clennam," he said, taking the seat which Clennam offered him.

"I must confess to being much surprised."

"Not disagreeably, I hope?"

"By no means."

"Thank you. Frankly," said the engaging young Barnacle, "I have been excessively sorry to hear that you were under the necessity of a temporary retirement here, and I hope (of course as between two private gentlemen) that our place has had nothing to do with it?"

"Your office?"

"Our Circumlocution place."

"I cannot charge any part of my reverses upon that remarkable establishment."

Commentary:

The title for this illustration as it appears in the New York edition of the same volume is much longer: He arose and opened it, and an agreeable voice accosted him with "How do you do, Mr. Clennam? I hope I am not unwelcome in calling to see you." — Book 2, chap. xxviii. The juxtaposition of the wood-engraving and passage illustrated and the lengthy passage serving as a caption makes it abundantly clear that the composite woodblock engraving serves as a headpiece in the Harper and Brothers printing. In contrast, in the Chapman and Hall volume, the plate appears eight pages ahead of the passage realized, forcing a proleptic reading that telegraphs to the reader the fact that Arthur Clennam's solitude will be interrupted by at least one visitor, one of the self-interested Barnacle clan that controls the government's Circumlocution Office, Dickens's satire on the British bureaucracy. This particular Ministry's charge, ably executed by cabinet minister and Merdle confederate Lord Decimus Tite Barnacle, "to fetter public spirit, to contract the enterprise, to damp the independent self-reliance" (Book I: Chapter 34, "A Shoal of Barnacles,") of the British. Consequently, the Circumlocution Office and the legion of Barnacles are anathema to Clennam's business partner, the engineer and inventor Daniel Doyce.

Whereas Dickens's original illustrator, Hablot Knight Browne had focused on the dialogue between the mercenary Frenchman, Rigaud, and Arthur Clennam in Arthur's private room in the Marshalsea later in the chapter, James Mahoney has decided to focus on the first visitor that day, Lord Decimus's private secretary, Ferdinand, who concedes that occasionally the Circumlocution Office occasionally "floors" men of business and free enterprise in the Barnacles' attempts to protect the Public Service. The "pupil" of the debtors' prison is naturally a little critical of the Circumlocution Office's failure to detect Merdle's massive swindle and protect the public interest. Rugg, the provisioner, is Clennam's second visitor; he then receives a significant trio: Pancks, Cavaletto, and Rigaud. This is the visit that Phiz chose to realise since it, rather than the other two, advances the plot.

It was the sprightly young Barnacle, Ferdinand

Text Illustrated:

"One day when he might have been some ten or twelve weeks in jail, and when he had been trying to read and had not been able to release even the imaginary people of the book from the Marshalsea, a footstep stopped at his door, and a hand tapped at it. He arose and opened it, and an agreeable voice accosted him with "How do you do, Mr. Clennam? I hope I am not unwelcome in calling to see you."

It was the sprightly young Barnacle, Ferdinand. He looked very good-natured and prepossessing, though overpoweringly gay and free, in contrast with the squalid prison.

"You are surprised to see me, Mr. Clennam," he said, taking the seat which Clennam offered him.

"I must confess to being much surprised."

"Not disagreeably, I hope?"

"By no means."

"Thank you. Frankly," said the engaging young Barnacle, "I have been excessively sorry to hear that you were under the necessity of a temporary retirement here, and I hope (of course as between two private gentlemen) that our place has had nothing to do with it?"

"Your office?"

"Our Circumlocution place."

"I cannot charge any part of my reverses upon that remarkable establishment."

Commentary:

The title for this illustration as it appears in the New York edition of the same volume is much longer: He arose and opened it, and an agreeable voice accosted him with "How do you do, Mr. Clennam? I hope I am not unwelcome in calling to see you." — Book 2, chap. xxviii. The juxtaposition of the wood-engraving and passage illustrated and the lengthy passage serving as a caption makes it abundantly clear that the composite woodblock engraving serves as a headpiece in the Harper and Brothers printing. In contrast, in the Chapman and Hall volume, the plate appears eight pages ahead of the passage realized, forcing a proleptic reading that telegraphs to the reader the fact that Arthur Clennam's solitude will be interrupted by at least one visitor, one of the self-interested Barnacle clan that controls the government's Circumlocution Office, Dickens's satire on the British bureaucracy. This particular Ministry's charge, ably executed by cabinet minister and Merdle confederate Lord Decimus Tite Barnacle, "to fetter public spirit, to contract the enterprise, to damp the independent self-reliance" (Book I: Chapter 34, "A Shoal of Barnacles,") of the British. Consequently, the Circumlocution Office and the legion of Barnacles are anathema to Clennam's business partner, the engineer and inventor Daniel Doyce.

Whereas Dickens's original illustrator, Hablot Knight Browne had focused on the dialogue between the mercenary Frenchman, Rigaud, and Arthur Clennam in Arthur's private room in the Marshalsea later in the chapter, James Mahoney has decided to focus on the first visitor that day, Lord Decimus's private secretary, Ferdinand, who concedes that occasionally the Circumlocution Office occasionally "floors" men of business and free enterprise in the Barnacles' attempts to protect the Public Service. The "pupil" of the debtors' prison is naturally a little critical of the Circumlocution Office's failure to detect Merdle's massive swindle and protect the public interest. Rugg, the provisioner, is Clennam's second visitor; he then receives a significant trio: Pancks, Cavaletto, and Rigaud. This is the visit that Phiz chose to realise since it, rather than the other two, advances the plot.

Book II Chapter 28 - Phiz

In The Old Room

Book II Chapter 28

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"His door was immediately swung open by a thump, and in the doorway stood the missing Blandois, the cause of many anxieties.

"Salve, fellow jail-bird!" said he. "You want me, it seems. Here I am!"

Before Arthur could speak to him in his indignant wonder, Cavalletto followed him into the room. Mr. Pancks followed Cavalletto. Neither of the two had been there since its present occupant had had possession of it. Mr. Pancks, breathing hard, sidled near the window, put his hat on the ground, stirred his hair up with both hands, and folded his arms, like a man who had come to a pause in a hard day's work. Mr. Baptist, never taking his eyes from his dreaded chum of old, softly sat down on the floor with his back against the door and one of his ankles in each hand: resuming the attitude (except that it was now expressive of unwinking watchfulness) in which he had sat before the same man in the deeper shade of another prison, one hot morning at Marseilles.

"I have it on the witnessing of these two madmen," said Monsieur Blandois, otherwise Lagnier, otherwise Rigaud, "that you want me, brother-bird. Here I am!"

Glancing round contemptuously at the bedstead, which was turned up by day, he leaned his back against it as a resting-place, without removing his hat from his head, and stood defiantly lounging with his hands in his pockets."

Commentary:

Perhaps three months after Arthur's taking tea with John Chivery in the Marshalsea, "The Pupil of the the Marshalsea" receives four visitors from the outside world in his cramped quarters, formerly assigned to "The Patriarch," William Dorrit. The first is one of the Barnacles from the Circumlocution Office, who is just politely calling to see if the activities of the bureaucratic (and obstructionist) office have inadvertently ruined Clennam. The group of outside visitors that then appears consists of the previously missing Blandois (i., e., Rigaud), the Italian Cavaletto ("Mr. Baptist," as he is called in Bleeding Heart Yard), and that astute man of business (whose advice landed Arthur in the Marshalsea), Mr. Pancks. Blandois' visit is hardly disinterested, for he informs Arthur that he has something of value to Mrs. Clennam that he is prepared to part with for a price. He will give her one week to respond.

In The Old Room

Book II Chapter 28

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"His door was immediately swung open by a thump, and in the doorway stood the missing Blandois, the cause of many anxieties.

"Salve, fellow jail-bird!" said he. "You want me, it seems. Here I am!"

Before Arthur could speak to him in his indignant wonder, Cavalletto followed him into the room. Mr. Pancks followed Cavalletto. Neither of the two had been there since its present occupant had had possession of it. Mr. Pancks, breathing hard, sidled near the window, put his hat on the ground, stirred his hair up with both hands, and folded his arms, like a man who had come to a pause in a hard day's work. Mr. Baptist, never taking his eyes from his dreaded chum of old, softly sat down on the floor with his back against the door and one of his ankles in each hand: resuming the attitude (except that it was now expressive of unwinking watchfulness) in which he had sat before the same man in the deeper shade of another prison, one hot morning at Marseilles.

"I have it on the witnessing of these two madmen," said Monsieur Blandois, otherwise Lagnier, otherwise Rigaud, "that you want me, brother-bird. Here I am!"

Glancing round contemptuously at the bedstead, which was turned up by day, he leaned his back against it as a resting-place, without removing his hat from his head, and stood defiantly lounging with his hands in his pockets."

Commentary:

Perhaps three months after Arthur's taking tea with John Chivery in the Marshalsea, "The Pupil of the the Marshalsea" receives four visitors from the outside world in his cramped quarters, formerly assigned to "The Patriarch," William Dorrit. The first is one of the Barnacles from the Circumlocution Office, who is just politely calling to see if the activities of the bureaucratic (and obstructionist) office have inadvertently ruined Clennam. The group of outside visitors that then appears consists of the previously missing Blandois (i., e., Rigaud), the Italian Cavaletto ("Mr. Baptist," as he is called in Bleeding Heart Yard), and that astute man of business (whose advice landed Arthur in the Marshalsea), Mr. Pancks. Blandois' visit is hardly disinterested, for he informs Arthur that he has something of value to Mrs. Clennam that he is prepared to part with for a price. He will give her one week to respond.

Kim wrote: "Book II Chapter 28 - James Mahoney

It was the sprightly young Barnacle, Ferdinand

Text Illustrated:

"One day when he might have been some ten or twelve weeks in jail, and when he had been tryi..."

This illustration and the commentary offer us a very clear example of how a plate (made of metal) and a woodblock offered the reader a very different experience. Woodblocks could be dropped in anywhere within the text whereas a plate could not.

Thus, plates were often a type of spoiler for the reader. Other times, the plate would appear much after the letterpress event occurred. It’s little wonder that woodblocks slowly took over from plates when the text had illustrations.

It was the sprightly young Barnacle, Ferdinand

Text Illustrated:

"One day when he might have been some ten or twelve weeks in jail, and when he had been tryi..."