Works of Thomas Hardy discussion

This topic is about

Tess of the D’Urbervilles

Tess of the d'Urbervilles

>

Tess of the D'Urbervilles - Phase the Fifth: Chapter 35 - 44

Here are LINKS TO EACH CHAPTER SUMMARY, for ease of location:

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

About the cover picture:

The cover picture shows Woolbridge Manor, a 17th-century manor house in East Stoke, just outside the village of Wool, in Dorset. Please see my earlier post LINK HERE, for details of the village of Wool, which Thomas Hardy calls “Wellbridge”. Now we can see the connection with Alec d’Urberville’s question about “Stoke-d’Urbervilles” too. It is on the north side of the old Wool bridge, a historic crossing point over the River Frome.

Woolbridge Manor House and River Frome

There was a lovely description of Tess and Angel’s approach to the manor house in the previous chapter, 34:

“They drove by the level road along the valley to a distance of a few miles, and, reaching Wellbridge, turned away from the village to the left, and over the great Elizabethan bridge which gives the place half its name. Immediately behind it stood the house wherein they had engaged lodgings, whose exterior features are so well known to all travellers through the Froom Valley; once portion of a fine manorial residence, and the property and seat of a D’Urberville, but since its partial demolition a farm-house.”

The cover picture shows Woolbridge Manor, a 17th-century manor house in East Stoke, just outside the village of Wool, in Dorset. Please see my earlier post LINK HERE, for details of the village of Wool, which Thomas Hardy calls “Wellbridge”. Now we can see the connection with Alec d’Urberville’s question about “Stoke-d’Urbervilles” too. It is on the north side of the old Wool bridge, a historic crossing point over the River Frome.

Woolbridge Manor House and River Frome

There was a lovely description of Tess and Angel’s approach to the manor house in the previous chapter, 34:

“They drove by the level road along the valley to a distance of a few miles, and, reaching Wellbridge, turned away from the village to the left, and over the great Elizabethan bridge which gives the place half its name. Immediately behind it stood the house wherein they had engaged lodgings, whose exterior features are so well known to all travellers through the Froom Valley; once portion of a fine manorial residence, and the property and seat of a D’Urberville, but since its partial demolition a farm-house.”

Woolbridge Manor: Thomas Hardy's "Wellbridge House" has three storeys of red brick and stone construction and the roof is clay tiles and stone slates to the eaves. Many windows around the building have been removed at some time, possibly due to the window tax in 1696. Woolbridge Manor is said to have been garrisoned in the English Civil War and still has some of the metal bars set into the remaining ground floor stone mullion windows, as well as a wooden security bar across the front door. It was at some time partially demolished and was once much bigger, possibly forming a hollow square with an enclosed courtyard in the centre. It is rumoured that a tunnel runs under the river from the Manor to Bindon Abbey.

The Manor was formerly in possession of the Turberville family of Dorset (descendants of George Turberville) until it was sold in the eighteenth century. Thomas Hardy has not changed the name very much at all! And on the first floor landing, there really are two seventeenth-century mural portraits, as mentioned in the novel as “ladies of the D’Urberville family”, Tess’s ancestors.

The Manor was formerly in possession of the Turberville family of Dorset (descendants of George Turberville) until it was sold in the eighteenth century. Thomas Hardy has not changed the name very much at all! And on the first floor landing, there really are two seventeenth-century mural portraits, as mentioned in the novel as “ladies of the D’Urberville family”, Tess’s ancestors.

The Phantom Coach of the Turbervilles:

This is based on an existing legend too. A local legend states that a phantom coach crosses the bridge by Woolbridge Manor at night, but that only those with Turberville blood can see it. Various versions of the legend exist, but one associates the coach with the elopement of John Turberville of Woolbridge with Anne, the daughter of Thomas Howard, 1st Viscount Howard of Bindon.

Thomas Hardy has used all this to great effect in Tess of the D’Urbervilles :)

This is based on an existing legend too. A local legend states that a phantom coach crosses the bridge by Woolbridge Manor at night, but that only those with Turberville blood can see it. Various versions of the legend exist, but one associates the coach with the elopement of John Turberville of Woolbridge with Anne, the daughter of Thomas Howard, 1st Viscount Howard of Bindon.

Thomas Hardy has used all this to great effect in Tess of the D’Urbervilles :)

Chapter 35: Summary

Tess finishes her story, and everything surrounding them seems different: the “essence of things” seems to have been transformed by it. Angel cannot yet comprehend the truth, and wonders if Tess is our of her mind, asking why she did not tell him before. Tess begs him to forgive her, as she forgave him for “the same”.

Angel says forgiveness does not even apply here, that Tess is now an entirely different person than he had thought. He laughs hollowly and Tess cries out for mercy, and reveals the depths of her love. Angel repeats that he has not loved her, but another woman he thought was Tess. Tess suddenly comprehends his point of view and is terrified.

Tess sits down and finally takes pity on herself and starts to weep. She asks if they can ever live together now, and Angel says he has not decided yet. Tess despairs and says she will obey like a servant, and will not do anything that Angel doesn’t command her to. Angel points out how her present self-sacrifice does not fit with her earlier self-preservation, and Tess takes this likes a beaten animal.

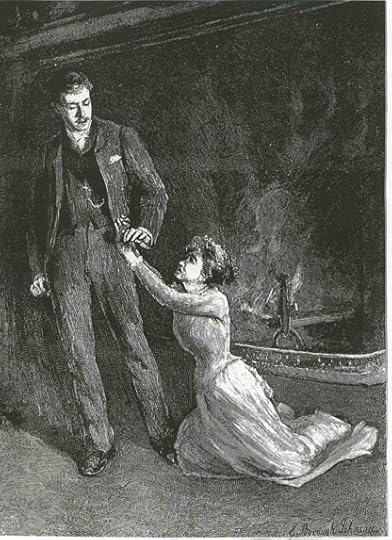

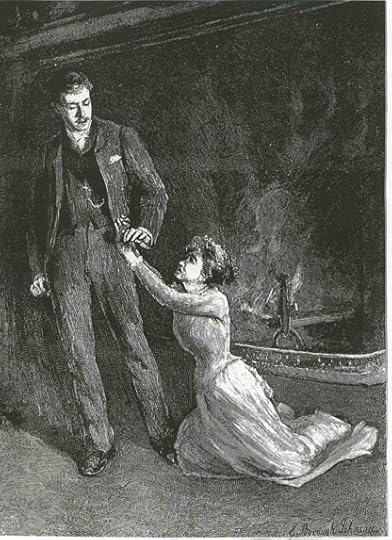

"She slid down upon her knees beside his foot." - E. Borough Johnson - "The Graphic" - 10th October 1891

Angel cries a single tear. His whole universe has been changed by her confession. He leaves the house to think, and their twin wine glasses stand tragically full. Tess follows him out into the clear night. Angel’s figure looks black and ominous, and he crosses a bridge without acknowledging her presence.

Tess follows Angel for a long time. The night clears his mind so that he can think logically about her, as if her spell over him has broken. Tess pleads that her sin was nothing she intended, and it makes no change in her personality or love, but Angel rebuffs her.

Angel admits that the sin was not her fault, but says Tess does not understand his society and manners. He cannot help but think that her ancestry makes her weak-willed, and it betrays his idea of her as a “new-sprung child of nature”. They walk on in sad silence, and a cottager notices them passing as if in a funeral procession.

Tess offers to drown herself in the river to spare Angel his pain. Angel calls her absurd and says their trouble is more satire than tragedy. He sends her home to bed. Everything about the house is the same, and Tess notices sadly the mistletoe that Angel had hung over the bed as a surprise. She feels empty and dull and soon falls asleep.

Angel returns later and is both relieved and bitter that Tess is asleep. He almost enters her room, but then looks again at the d’Urberville portraits and their sinister faces strengthen his resolution. His own face is cold, unhappy, and free of passion. Angel feels that Tess’s appearance had deceived him as to her inner self, but Tess has no advocate to defend her.

Tess finishes her story, and everything surrounding them seems different: the “essence of things” seems to have been transformed by it. Angel cannot yet comprehend the truth, and wonders if Tess is our of her mind, asking why she did not tell him before. Tess begs him to forgive her, as she forgave him for “the same”.

Angel says forgiveness does not even apply here, that Tess is now an entirely different person than he had thought. He laughs hollowly and Tess cries out for mercy, and reveals the depths of her love. Angel repeats that he has not loved her, but another woman he thought was Tess. Tess suddenly comprehends his point of view and is terrified.

Tess sits down and finally takes pity on herself and starts to weep. She asks if they can ever live together now, and Angel says he has not decided yet. Tess despairs and says she will obey like a servant, and will not do anything that Angel doesn’t command her to. Angel points out how her present self-sacrifice does not fit with her earlier self-preservation, and Tess takes this likes a beaten animal.

"She slid down upon her knees beside his foot." - E. Borough Johnson - "The Graphic" - 10th October 1891

Angel cries a single tear. His whole universe has been changed by her confession. He leaves the house to think, and their twin wine glasses stand tragically full. Tess follows him out into the clear night. Angel’s figure looks black and ominous, and he crosses a bridge without acknowledging her presence.

Tess follows Angel for a long time. The night clears his mind so that he can think logically about her, as if her spell over him has broken. Tess pleads that her sin was nothing she intended, and it makes no change in her personality or love, but Angel rebuffs her.

Angel admits that the sin was not her fault, but says Tess does not understand his society and manners. He cannot help but think that her ancestry makes her weak-willed, and it betrays his idea of her as a “new-sprung child of nature”. They walk on in sad silence, and a cottager notices them passing as if in a funeral procession.

Tess offers to drown herself in the river to spare Angel his pain. Angel calls her absurd and says their trouble is more satire than tragedy. He sends her home to bed. Everything about the house is the same, and Tess notices sadly the mistletoe that Angel had hung over the bed as a surprise. She feels empty and dull and soon falls asleep.

Angel returns later and is both relieved and bitter that Tess is asleep. He almost enters her room, but then looks again at the d’Urberville portraits and their sinister faces strengthen his resolution. His own face is cold, unhappy, and free of passion. Angel feels that Tess’s appearance had deceived him as to her inner self, but Tess has no advocate to defend her.

What a devastating chapter! Our 21st century selves want to scream at the sexual double standard, but we must remember that this was the culture of the time. What is does demonstrate is that Angel is still bound by English Victorian society's middle class conventions - as he himself admits towards the end of the chapter. The sharp contrast between Tess’s reaction to Angel’s confession and Angel to Tess’s, emphasises the unfairness, which Tess, displaying a surprisingly modern attitude in this aspect, sees but Angel dismisses with a: “don’t argue”.

The point I’d like to highlight is that for all Angel’s education and ideas about free thinking, he shows a remarkable lack of logic and constructive argument! He has long prided himself as someone not blinded by the conventions of society. Yet if he can see that “You were more sinned against than sinning”, it seems extraordinary that he should shrug off Tess’s simple logic, and revert to his all-consuming idea that “the woman I have been loving is not you [but] … another woman in your shape.”. Angel is far more concerned with his own inner thoughts and ideals than reality, or any practical implications. He also seems oblivious to the fact that Tess is a living breathing person, although at one point we are told that he "tries to be gentle".

There is obviously a lot to discuss about the psychology of both characters here. Tess’s love is still mature and deep, but Angel only loved an ideal. I feel there will be lots of indignation at Angel’s unkindness and sardonic comments forthcoming! And Angel’s large, slow tear? Who - or what - is that for?

The point I’d like to highlight is that for all Angel’s education and ideas about free thinking, he shows a remarkable lack of logic and constructive argument! He has long prided himself as someone not blinded by the conventions of society. Yet if he can see that “You were more sinned against than sinning”, it seems extraordinary that he should shrug off Tess’s simple logic, and revert to his all-consuming idea that “the woman I have been loving is not you [but] … another woman in your shape.”. Angel is far more concerned with his own inner thoughts and ideals than reality, or any practical implications. He also seems oblivious to the fact that Tess is a living breathing person, although at one point we are told that he "tries to be gentle".

There is obviously a lot to discuss about the psychology of both characters here. Tess’s love is still mature and deep, but Angel only loved an ideal. I feel there will be lots of indignation at Angel’s unkindness and sardonic comments forthcoming! And Angel’s large, slow tear? Who - or what - is that for?

The more I read Thomas Hardy, the more I realise how and why he viewed himself as primarily a poet. It’s not only by the language he uses but by his references.

The first part of this continued the breathtaking descriptions of the unearthly, devilish aspect of the couple’s surroundings. I’d love to hear your thoughts and examples on this. An example of the other aspect is that Thomas Hardy has recourse to 2 poets in this chapter alone! First is Algernon Charles Swinburne, with the four lines beginning “Behold, when thy face is made bare …”’

Erich has alerted us to references to Algernon Charles Swinburne before, in Chapter 25 - perhaps you could help us with this one please too, Erich? It’s clearly related to Tess in this context.

The other I spotted was a line from “By the Fire-side” by Robert Browning: “The little less, and what worlds away!” So poignant! Would anyone like to comment?

The first part of this continued the breathtaking descriptions of the unearthly, devilish aspect of the couple’s surroundings. I’d love to hear your thoughts and examples on this. An example of the other aspect is that Thomas Hardy has recourse to 2 poets in this chapter alone! First is Algernon Charles Swinburne, with the four lines beginning “Behold, when thy face is made bare …”’

Erich has alerted us to references to Algernon Charles Swinburne before, in Chapter 25 - perhaps you could help us with this one please too, Erich? It’s clearly related to Tess in this context.

The other I spotted was a line from “By the Fire-side” by Robert Browning: “The little less, and what worlds away!” So poignant! Would anyone like to comment?

That’s enough from me - oh except to mention how the d’Urberville family and their ancestral home seem to be a curse on Tess, and on Angel’s view of her. Do read the first posts; you might find the origins interesting!

I’m looking forward to hearing everyone’s thoughts. Thomas Hardy called this Phase “The Woman Pays” Indeed she is doing!

I’m looking forward to hearing everyone’s thoughts. Thomas Hardy called this Phase “The Woman Pays” Indeed she is doing!

Jean, ‘By the Fireside’ is by Robert Browning

Jean, ‘By the Fireside’ is by Robert BrowningLink to poem here: https://www.poemhunter.com/poem/by-th...

I knew this chapter would happen and knew what Angel's reactions would be and it was still heartbreaking to me that it would happen. Hardy shows how fragile love can be — Tess' is true but Angel, so far, is not.

I knew this chapter would happen and knew what Angel's reactions would be and it was still heartbreaking to me that it would happen. Hardy shows how fragile love can be — Tess' is true but Angel, so far, is not.Of course, many of us see Angel's reaction as a matter of pride: his prize possession is not less valuable but it is certainly tarnished in his eyes. Seeing Tess not as a living, breathing individual and not as a possession, especially not a mirror reflecting his image. It is typical of his time but it is still so disappointing.

It certainly does seem to be his pride that is hurt. Perhaps the more because he realises that Tess readily forgives him and still loves him, and he cannot do the same. It seems he does not blame her for what happened to her, but for her being honest about it and making him realise how foolish he was.

These chapters are so dark, and still I cannot help but love them. The imagery, and also I can almost feel Tess' fear of losing the man she dearly loves, no, knowing she already lost him before they had their wedding night.

Meanwhile Angel says Tess is not the woman he married, while to us as modern readers she clearly is still the same person, and he is the one who changes from a playful, loving, ideal husband into a proud, cold-hearted man of his time.

These chapters are so dark, and still I cannot help but love them. The imagery, and also I can almost feel Tess' fear of losing the man she dearly loves, no, knowing she already lost him before they had their wedding night.

Meanwhile Angel says Tess is not the woman he married, while to us as modern readers she clearly is still the same person, and he is the one who changes from a playful, loving, ideal husband into a proud, cold-hearted man of his time.

And yes, I do know I am reading this through 21st century eyes. That doesn't change the fact that I would love to kick Angel in his unmentionables right now. :-P

LOL Jantine! I think you are well aware of Victorian sensibilities in your posts. But human instincts and feelings are timeless :)

What struck me as well, is how essentially Victorian the illustration for chapter 35 is. It's as if it is posed by actors, and staged, like a Victorian melodrama. Yet this is completely authentic to the book, even to the hellish flames.

What struck me as well, is how essentially Victorian the illustration for chapter 35 is. It's as if it is posed by actors, and staged, like a Victorian melodrama. Yet this is completely authentic to the book, even to the hellish flames.

This is such a beautifully written chapter, and yet I dread reading it.

I thought Tess showed remarkable self-awareness when she said "I am only peasant by position, not by nature!".

How ignorant and stupid is Angel when he says "do not make me reproach you. I have sworn that I will not". Just because he doesn't speak words of disapproval at Tess (which actually he does!), does not mean he is avoiding reproachment with his actions. This in just one more example of what Jean called Angel's "lack of logic". maybe his biggest character flaw.

I thought Tess showed remarkable self-awareness when she said "I am only peasant by position, not by nature!".

How ignorant and stupid is Angel when he says "do not make me reproach you. I have sworn that I will not". Just because he doesn't speak words of disapproval at Tess (which actually he does!), does not mean he is avoiding reproachment with his actions. This in just one more example of what Jean called Angel's "lack of logic". maybe his biggest character flaw.

This entire chapter might well be summed up in just one exchange:

This entire chapter might well be summed up in just one exchange:"I will obey you like your wretched slave, even if it is to lie down and die.”

“You are very good. But it strikes me that there is a want of harmony between your present mood of self-sacrifice and your past mood of self-preservation.”

The harsh disdain of Angel’s pronouncement denotes an implacability from which there can be no retreat. It also seems to me that his use of the term “self-preservation” could have two quite different meanings: It might be intended as an accusation of deception on Tess’s part in withholding her secret until after they were wed. Or it could mean that she was lacking in strength of character, a failure to preserve her maidenhood. Either way, the degree of antagonism suggests that the marriage is over before it has begun.

The bit that made me most angry at Angel was when he threw her ancestors at Tess, as if she had any control over that. The double standards of the time were to be expected but how he twists his own view of her with the new information shows he never really loved Tess the person.

The bit that made me most angry at Angel was when he threw her ancestors at Tess, as if she had any control over that. The double standards of the time were to be expected but how he twists his own view of her with the new information shows he never really loved Tess the person.Heaven, why did you give me a handle for despising you more by informing me of your descent! Here was I thinking you a new-sprung child of nature, there were you, the belated seedling of an effete aristocracy!

Tess has never been the one who cared about her lineage, Angel chose the carriage, the house etc.

I really hated him at this point (more than I hated Alec at any stage!)

On a quite different note, bearing in mind Hardy’s fascination with fate, the resemblance of Tess to one of the grim portraits of D’Urberville women may suggest the existences of a family curse of sorts, a damnosa hereditas with which Tess is burdened.

On a quite different note, bearing in mind Hardy’s fascination with fate, the resemblance of Tess to one of the grim portraits of D’Urberville women may suggest the existences of a family curse of sorts, a damnosa hereditas with which Tess is burdened.

Jim wrote: "This entire chapter might well be summed up in just one exchange:

Jim wrote: "This entire chapter might well be summed up in just one exchange:"I will obey you like your wretched slave, even if it is to lie down and die.”

“You are very good. But it strikes me that there is ..."

He's also resentful that Tess was able to fall asleep and it seems to reinforce his notion that he has been deceived.

Bionic Jean wrote: "Erich has alerted us to references to Algernon Charles Swinburne before, in Chapter 25 - perhaps you could help us with this one please too, Erich? It’s clearly related to Tess in this context.."

Bionic Jean wrote: "Erich has alerted us to references to Algernon Charles Swinburne before, in Chapter 25 - perhaps you could help us with this one please too, Erich? It’s clearly related to Tess in this context.."Hardy frames the poem as Time's "satiric psalm." In Swinburne's "Now as with Sundering of the Earth," the poet shares Hardy's bleak view of the workings of fate - "the daughter of doom, the mother of death,/the sister of sorrow." Fate is "the bitter jealousy of God" who withers human happiness ("spring") until "thy life shall fall as a leaf and be shed as the rain." In earlier lines, Swinburne writes, "For death is deep as the sea,/ And fate as the waves thereof./ Shall the waves take pity on thee/ Or the southwind offer thee love?" The poet refers to the human condition in general, but Hardy applies it specifically to how Angel perceives Tess suddenly like a withered crone "in all her baseness."

Jim wrote: "bearing in mind Hardy’s fascination with fate, the resemblance of Tess to one of the grim portraits of D’Urberville women may suggest the existences of a family curse ..."

Yes, I'm quite sure this is deliberate. Peter also highlighted a part where a beam of light shone on Tess, like a stain of the d'Urbervilles. I am impressed by the fact that these two portraits are still in existence. They are murals, painted on the plasterwork, so cannot be removed. (See my first posts in the thread.)

Yes, I'm quite sure this is deliberate. Peter also highlighted a part where a beam of light shone on Tess, like a stain of the d'Urbervilles. I am impressed by the fact that these two portraits are still in existence. They are murals, painted on the plasterwork, so cannot be removed. (See my first posts in the thread.)

Thank you for this analysis Erich :) What a powerful poem!

Here it is, complete:

https://www.poetrynook.com/poem/not-s...

"Not as with Sundering of the Earth" by Algernon Charles Swinburne.

Here it is, complete:

https://www.poetrynook.com/poem/not-s...

"Not as with Sundering of the Earth" by Algernon Charles Swinburne.

Chapter 36: Summary

Angel Clare wakes up and the room seems imbued with something criminal. He makes breakfast and calls for Tess, and her morning hopes die at the sight of Angel’s face. Neither of them seem able to feel any sensation after their previous night.

Tess looks purer and more innocent than ever, and Angel almost can’t believe that her story is true, but Tess reaffirms it. Clare asks for the first time about the baby and its father, and despairs that the father is alive and still in England. He says that he had decided to not take a wife of high society, and had thought that he was getting “rustic innocence” in Tess.

Tess says she believes that he can still divorce her, but Clare says she only has a crude understanding of the law. Tess feels even more guilty, and reveals that she considered killing herself with a cord, under his mistletoe the night before. She had only decided against it as it would have caused a scandal for him. Angel Clare is shaken and makes her promise to never think of killing herself again.

They eat breakfast mechanically and then Angel goes off to observe the miller at work. Tess watches him disappear over the bridge and then cleans and waits for his return. At lunch he discusses the mill, which is very old compared with most modern machinery, and then leaves again, returning at night. Tess busies herself in the kitchen the whole time.

Angel Clare finds her and says to stop working; that she is not his slave but his wife, and Tess says she thought she was not respectable enough for him. She starts to cry and Thomas Hardy observes that any other man but hard, sceptical Angel Clare might have had mercy, but he rejects her just as he had rejected the Church. He says it is not a matter of respectability, but of principle. Tess takes his condemnation meekly and makes herself pathetically subservient to him. She is like Charity personified returning to the cruel modern world.

Three days pass in the same manner, and one morning Tess offers her face to kiss, but Angel Clare ignores it. She is crushed by his rejection, and he says that they have been living together so far for form’s sake only, but it cannot last. Time passes, and Tess no longer hopes for forgiveness.

He spends all his time trying to work out what to do next, and tells Tess he cannot live with her without despising both of them. He cannot accept that “that man” still lives as her “husband in nature” and that nowhere on Earth is far enough away to escape the past, and their future children would suffer for it.

Tess had hoped that she could wear down Angel’s resolve just by being close to him, but when she sees how far he has thought ahead she despairs. Experience has taught her that life itself is a penalty, no matter how well you try to live it. Also, she had never considered that others [her future children] might come to suffer for her personal misfortune.

Thomas Hardy again observes that Tess still might have used her own beauty and the image of a far-off land to persuade him, but she is too crushed to even try. The narrator muses that if Angel Clare had a more animalistic nature he might have acted more justly, as here his idealism works against Tess.

Tess suggests that they part and she return home, but she is upset when he quickly agrees. He is still determined to submit his emotions to his ideals, and decides that he will leave too and write to her when he has cleared his mind.

They pack with an air of finality, and both know that it is unlikely that their passion will return, as other things will fill their lives while they are apart.

Angel Clare wakes up and the room seems imbued with something criminal. He makes breakfast and calls for Tess, and her morning hopes die at the sight of Angel’s face. Neither of them seem able to feel any sensation after their previous night.

Tess looks purer and more innocent than ever, and Angel almost can’t believe that her story is true, but Tess reaffirms it. Clare asks for the first time about the baby and its father, and despairs that the father is alive and still in England. He says that he had decided to not take a wife of high society, and had thought that he was getting “rustic innocence” in Tess.

Tess says she believes that he can still divorce her, but Clare says she only has a crude understanding of the law. Tess feels even more guilty, and reveals that she considered killing herself with a cord, under his mistletoe the night before. She had only decided against it as it would have caused a scandal for him. Angel Clare is shaken and makes her promise to never think of killing herself again.

They eat breakfast mechanically and then Angel goes off to observe the miller at work. Tess watches him disappear over the bridge and then cleans and waits for his return. At lunch he discusses the mill, which is very old compared with most modern machinery, and then leaves again, returning at night. Tess busies herself in the kitchen the whole time.

Angel Clare finds her and says to stop working; that she is not his slave but his wife, and Tess says she thought she was not respectable enough for him. She starts to cry and Thomas Hardy observes that any other man but hard, sceptical Angel Clare might have had mercy, but he rejects her just as he had rejected the Church. He says it is not a matter of respectability, but of principle. Tess takes his condemnation meekly and makes herself pathetically subservient to him. She is like Charity personified returning to the cruel modern world.

Three days pass in the same manner, and one morning Tess offers her face to kiss, but Angel Clare ignores it. She is crushed by his rejection, and he says that they have been living together so far for form’s sake only, but it cannot last. Time passes, and Tess no longer hopes for forgiveness.

He spends all his time trying to work out what to do next, and tells Tess he cannot live with her without despising both of them. He cannot accept that “that man” still lives as her “husband in nature” and that nowhere on Earth is far enough away to escape the past, and their future children would suffer for it.

Tess had hoped that she could wear down Angel’s resolve just by being close to him, but when she sees how far he has thought ahead she despairs. Experience has taught her that life itself is a penalty, no matter how well you try to live it. Also, she had never considered that others [her future children] might come to suffer for her personal misfortune.

Thomas Hardy again observes that Tess still might have used her own beauty and the image of a far-off land to persuade him, but she is too crushed to even try. The narrator muses that if Angel Clare had a more animalistic nature he might have acted more justly, as here his idealism works against Tess.

Tess suggests that they part and she return home, but she is upset when he quickly agrees. He is still determined to submit his emotions to his ideals, and decides that he will leave too and write to her when he has cleared his mind.

They pack with an air of finality, and both know that it is unlikely that their passion will return, as other things will fill their lives while they are apart.

This is a difficult chapter, as Thomas Hardy describes Angel Clare’s confused mental and emotional struggle.

“Clare’s love was doubtless ethereal to a fault, imaginative to impracticability.”

There are many complex issues put forward, but I have tried to summarise what Thomas Hardy actually said without my own reactions. For instance, have you noticed that when Angel Clare was being loving in the earlier chapters, he was referred to as “Angel”. Then there was a sudden switch, and now he is referred to as “Clare” (or “he” or by his full name) and only ever referred to as “Angel” when he is looked at through Tess’s loving eyes?

My personal view then, is that Angel Clare is far more cruel than Alec d’Urberville ever was. Unless we believe it was all a cunning plan, we have to believe that Alec was straightforward in his admiration of Tess, and knows he went (far!) too far, but tried to put it right as best he could. (Tess never told him she was pregnant.) Angel Clare is a very different kettle of fish, as he wavers in what he believes, and this influences how he behaves to people.

The quotation Jim picked out is one of several sarcastic comments by Angel Clare which no human should say to another unless they intend to hurt deeply. (We were told in fact that Tess did not understand the sarcasm, but only felt wounded by his attitude. I’m not sure this is much better!)

“Clare’s love was doubtless ethereal to a fault, imaginative to impracticability.”

There are many complex issues put forward, but I have tried to summarise what Thomas Hardy actually said without my own reactions. For instance, have you noticed that when Angel Clare was being loving in the earlier chapters, he was referred to as “Angel”. Then there was a sudden switch, and now he is referred to as “Clare” (or “he” or by his full name) and only ever referred to as “Angel” when he is looked at through Tess’s loving eyes?

My personal view then, is that Angel Clare is far more cruel than Alec d’Urberville ever was. Unless we believe it was all a cunning plan, we have to believe that Alec was straightforward in his admiration of Tess, and knows he went (far!) too far, but tried to put it right as best he could. (Tess never told him she was pregnant.) Angel Clare is a very different kettle of fish, as he wavers in what he believes, and this influences how he behaves to people.

The quotation Jim picked out is one of several sarcastic comments by Angel Clare which no human should say to another unless they intend to hurt deeply. (We were told in fact that Tess did not understand the sarcasm, but only felt wounded by his attitude. I’m not sure this is much better!)

Both men are too wrapped up in their own selves to see the damage they do to another person. Janelle said she really hated Angel at one point, more than she hated Alec at any stage.

Basically this is how I feel too, because Angel is clever and has choices, but at the moment is being devastatingly unfair and unkind. Alec is (I feel) not very bright, and single-minded in what he wants, but we have not seen the vindictiveness or lashing out that we see here.

We are only just half way through the novel of course, but I always come back to this when I see readers categorise Alec d’Urberville as an arch villain. Angel Clare clings to his principles and beliefs even in the face of others’ pain. He has just as much power over Tess now as Alec did, and he also abuses it—although in a very different way.

Notice how he grabbed at the opportunity which Tess offered him—for her to go to her parents’ home. This is not an intellectual decision, but made for dogmatic reasons:

“she was appalled by the determination revealed in the depths of this gentle being she had married—the will to subdue the grosser to the subtler emotion, the substance to the conception, the flesh to the spirit. Propensities, tendencies, habits, were as dead leaves upon the tyrannous wind of his imaginative ascendency.”

We also might suspect that this is a coward’s way out!

Basically this is how I feel too, because Angel is clever and has choices, but at the moment is being devastatingly unfair and unkind. Alec is (I feel) not very bright, and single-minded in what he wants, but we have not seen the vindictiveness or lashing out that we see here.

We are only just half way through the novel of course, but I always come back to this when I see readers categorise Alec d’Urberville as an arch villain. Angel Clare clings to his principles and beliefs even in the face of others’ pain. He has just as much power over Tess now as Alec did, and he also abuses it—although in a very different way.

Notice how he grabbed at the opportunity which Tess offered him—for her to go to her parents’ home. This is not an intellectual decision, but made for dogmatic reasons:

“she was appalled by the determination revealed in the depths of this gentle being she had married—the will to subdue the grosser to the subtler emotion, the substance to the conception, the flesh to the spirit. Propensities, tendencies, habits, were as dead leaves upon the tyrannous wind of his imaginative ascendency.”

We also might suspect that this is a coward’s way out!

But standing back objectively, what makes this chapter so incisive and complex is that Thomas Hardy gets inside these two characters and tells us all their muddled thoughts and motives. The irony is, in Thomas Hardy’s ethos, that if each had behaved as they felt naturally inclined to, their love might have sustained them.

Angel Clare does not mean to be cruel—it is a reaction. He too suffers:

“he was becoming ill with thinking; eaten out with thinking, withered by thinking; … He walked about saying to himself, “What’s to be done—what’s to be done?””

and we are even told that at one point (after rebuffing her offer to receive a kiss) “wished for a moment that he had responded yet more kindly”.

Tess too is behaving uncharacteristically. She is grovelling and cowed, denying her independent spirit because she feels she has been in the wrong, and that she should be abject. This struck me too, as possibly referring to Victorian women’s submission— although Thomas Hardy does talk about “feminine hope”, so could be postulating a natural difference between the sexes:

“like the majority of women, she accepted the momentary presentment as if it were the inevitable.”

It is also a comment on Tess’s belief in the inevitability of fate.

Angel Clare does not mean to be cruel—it is a reaction. He too suffers:

“he was becoming ill with thinking; eaten out with thinking, withered by thinking; … He walked about saying to himself, “What’s to be done—what’s to be done?””

and we are even told that at one point (after rebuffing her offer to receive a kiss) “wished for a moment that he had responded yet more kindly”.

Tess too is behaving uncharacteristically. She is grovelling and cowed, denying her independent spirit because she feels she has been in the wrong, and that she should be abject. This struck me too, as possibly referring to Victorian women’s submission— although Thomas Hardy does talk about “feminine hope”, so could be postulating a natural difference between the sexes:

“like the majority of women, she accepted the momentary presentment as if it were the inevitable.”

It is also a comment on Tess’s belief in the inevitability of fate.

But Tess had not realised how stubborn Angel could be. After her brief period of happiness she is now reinforced in her conception of the cruel injustice of fate.

“I have no wish opposed to yours.” Also

“How can you be so simple!” cries Angel Clare,

yet it was Tess’s simplicity that he had loved. He feels cheated of her lack of “innocence”. Tess may be simple but we are told over and over in this chapter that she intuits what he thinks and believes, yet he cannot—or will not—project into her state of mind.

Angel Clare is at the opposite extreme to Alec d’Uberville; he is so concerned for his own moral uprightness that he ends up being as unfair and hurtful to Tess as Alec was. He views the father of her child as her “natural husband”, although by the same logic, Angel Clare’s true wife is a woman in London! The concept of natural laws versus societal ones is used against Tess here.

As an added twist, even the mill here is of no use to Angel Clare, as it is too old and cannot connect with the modern, industrial world he helplessly belongs to.

There is quite a bit of subtle foreshadowing in the imagery of this chapter too :)

Your thoughts?

“I have no wish opposed to yours.” Also

“How can you be so simple!” cries Angel Clare,

yet it was Tess’s simplicity that he had loved. He feels cheated of her lack of “innocence”. Tess may be simple but we are told over and over in this chapter that she intuits what he thinks and believes, yet he cannot—or will not—project into her state of mind.

Angel Clare is at the opposite extreme to Alec d’Uberville; he is so concerned for his own moral uprightness that he ends up being as unfair and hurtful to Tess as Alec was. He views the father of her child as her “natural husband”, although by the same logic, Angel Clare’s true wife is a woman in London! The concept of natural laws versus societal ones is used against Tess here.

As an added twist, even the mill here is of no use to Angel Clare, as it is too old and cannot connect with the modern, industrial world he helplessly belongs to.

There is quite a bit of subtle foreshadowing in the imagery of this chapter too :)

Your thoughts?

Jim wrote: "This entire chapter might well be summed up in just one exchange:

Jim wrote: "This entire chapter might well be summed up in just one exchange:"I will obey you like your wretched slave, even if it is to lie down and die.”

“You are very good. But it strikes me that there is ..."

The insights in chapter 35 are wonderful. There is so much going on in such a small space. References to poetry, Shakespeare, Greek philosophy. So much to take in.

From our 21C viewpoint it is difficult, if not impossible, to not desire to aim a kick towards Angel. It is difficult to shed our 21C sensibilities to have any grasp of the Victorian mindset that would accept Angel’s position as being correct.

Hardy writes that the tragedy of their relationship is what their ‘Agape’ had come to. Earlier in the novel we learned what ‘Eros’ had lead to in Alec’s actions. I wonder what Hardy saw as the proper course of love between two people?

Lear lamented “I am a man more sinned against than sinning.” Hardy introduces this phrase to this chapter. How would 19C readers react to this question?

When Tess sees the mistletoe hanging from the ceiling in the bed-chamber ‘of her own ancestry’ she knows it was hung by Angel. Surely this was an act by Angel to proceed the consummation of their marriage. This act is one where Angel planned to move his emotions from ‘Agape’ to ‘Eros.’ Angel has admitted to a 48 hour dalliance with a female prior to his marriage and yet Tess’s admission of her ‘sin’ is unacceptable to him.

In this chapter Tess has experienced yet another man who walks away from her. Alec’s transgression was a calculated act of Eros. In Angel’s case, he has abandoned Tess because she does not live up to his selfish self-imposed morality. Who, I wonder, is more the sinner — Alec or Angel?

Thanks for the classical references Peter.

It sounds as thought you share my views of Alec and Angel at this point of the novel.

It sounds as thought you share my views of Alec and Angel at this point of the novel.

I don't understand exactly what Angel's beliefs and principles are. He has Christian values but is no longer a churchgoer. He has clearly forgiven himself for adultery, but cannot forgive Tess.

I don't understand exactly what Angel's beliefs and principles are. He has Christian values but is no longer a churchgoer. He has clearly forgiven himself for adultery, but cannot forgive Tess.I think his moral code is more defined by his vanity, his ambitions and his quest for perfection. In this chapter, he has shown he has a cowardly and weak nature. His much professed love for Tess was actually very shallow and more focused on the challenge of winning such a desirable prize than having her as his lifelong partner for better or for worse.

Peter wrote: "Lear lamented “I am a man more sinned against than sinning.” "

Peter wrote: "Lear lamented “I am a man more sinned against than sinning.” "The reference to Lear is also illuminating because his tragedy was brought about as a result of loving too much and allowing his daughters complete power over him. In these chapters, especially, Tess is behaving like a beaten dog, taking Angel's insults without daring to assert herself.

Even though Hardy's readers would likely have understood Angel's point of view better than we can, it is significant that the author juxtaposes Angel's past with Tess's so that the injustice in the comparison is without doubt.

I don't know that Angel is a worse man than Alec, but the damage he does by following his "principles" is perhaps greater than that inflicted by Alec. While it may be possible for a person like Alec to reform, I don't see how Angel could get to a place where he could overcome his (often illogical) beliefs.

Bionic Jean wrote: "LOL Jantine! I think you are well aware of Victorian sensibilities in your posts. But human instincts and feelings are timeless :)

Bionic Jean wrote: "LOL Jantine! I think you are well aware of Victorian sensibilities in your posts. But human instincts and feelings are timeless :)What struck me as well, is how essentially Victorian the illustra..."

I agree Jean and Janine! And reading Chapter 36, I feel that even more so. Angel wants it both ways: he doesn't want to blame her but he does, he claims that Alec "is her husband in nature" what a trite and worthless line. Alec is the seducer and once again Angels chastises Tess for her prior innocence. And there is poor Tess blaming herself as well. She is still so innocent that she won't defend herself.

We can say that our 21c sensibilities make us see Tess in more of a sentimental light but that still not exactly true. All you have to look to is how governments are again taking women's rights away from them and indeed, if such experiences as Tess has had is still blamed on her. While at least in today's society, there would be a divorce (at least in much of the world), the woman would still pay the penalty.

We can say that our 21c sensibilities make us see Tess in more of a sentimental light but that still not exactly true. All you have to look to is how governments are again taking women's rights away from them and indeed, if such experiences as Tess has had is still blamed on her. While at least in today's society, there would be a divorce (at least in much of the world), the woman would still pay the penalty.

I so enjoy reading this novel slowly, and in this chapter two reasons come to mind.

First, I stopped and looked up the Hamlet (III.i.81-82) reference from the notes section of my book. Hardy references it in this sentence "Don't you think we had better endure the ills we have than fly to others?". That line comes from the infamous "To be or not to be" soliloquy, which made me think, once again, Hardy is brilliant. Hamlet is a perfect comparison for Angel. The mental anguish they face, the indecision, the cowardice, its all there for both men.

The second connection I made reading slower this time, was how Hardy talks about the seduction path Tess could have taken, and why she didn't. The first time I read this I couldn't help wondering if they would just consummate their marriage everything would be okay. But Hardy's reveals their inner thoughts and explains why that can't happen "There was, it was true, underneath, a back current of sympathy through which a woman of the world might have conquered him. But Tess did not think of this" I think he's talking about seduction and the fact that Tess doesn't think of it really does make her an innocent woman, no matter what Angel has come to think.

First, I stopped and looked up the Hamlet (III.i.81-82) reference from the notes section of my book. Hardy references it in this sentence "Don't you think we had better endure the ills we have than fly to others?". That line comes from the infamous "To be or not to be" soliloquy, which made me think, once again, Hardy is brilliant. Hamlet is a perfect comparison for Angel. The mental anguish they face, the indecision, the cowardice, its all there for both men.

The second connection I made reading slower this time, was how Hardy talks about the seduction path Tess could have taken, and why she didn't. The first time I read this I couldn't help wondering if they would just consummate their marriage everything would be okay. But Hardy's reveals their inner thoughts and explains why that can't happen "There was, it was true, underneath, a back current of sympathy through which a woman of the world might have conquered him. But Tess did not think of this" I think he's talking about seduction and the fact that Tess doesn't think of it really does make her an innocent woman, no matter what Angel has come to think.

Pamela wrote: "While at least in today's society, there would be a divorce (at least in much of the world), the woman would still pay the penalty..."

I have lots of sympathy for your views, Pamela. But you also remind of me of something that confused me in this chapter. When Angel says a divorce is not possible does he mean its not "legally" possible in the 19c, or is he saying his moral code won't allow him to divorce Tess? I think its the later, but I'm not sure.

I have lots of sympathy for your views, Pamela. But you also remind of me of something that confused me in this chapter. When Angel says a divorce is not possible does he mean its not "legally" possible in the 19c, or is he saying his moral code won't allow him to divorce Tess? I think its the later, but I'm not sure.

Bionic Jean wrote: "But Tess had not realised how stubborn Angel could be. After her brief period of happiness she is now reinforced in her conception of the cruel injustice of fate.

Bionic Jean wrote: "But Tess had not realised how stubborn Angel could be. After her brief period of happiness she is now reinforced in her conception of the cruel injustice of fate.“I have no wish opposed to yours...."

Chapter 36 is yet another puzzle for me. I cannot understand Angel’s arguments to cast off Tess, and I do mean cast her off. Is he so apparently philosophical, so ethereal, that the real world of dirt and blood and disappointment is merely a theory? That can’t be. He is curious. He wants to learn, to understand a job, he wants to experience innovation, and yet his morals are unexplainable to me.

Hardy’s use of symbols and settings further confuses me. We read that to get to the mill he must cross a stone bridge and cross a railway. When he returns to an awaiting Tess he tells her that his experience at the mill was not enlightening since the mill had been in use ever since it ground for the monks. The mill is more a heap of ruins. Now, I took those lines to mean the past does not answer his needs. He must cross railway tracks (a sign of progress and innovation in the 19C) to reach the mill. If he is a man who is looking to enter the modern world and his morals are encased in his philosophical mind how does he expect to survive?

I’m so confused by his actions.

Bridget wrote: "When Angel says a divorce is not possible does he mean its not "legally" possible in the 19c, or is he saying his moral code won't allow him to divorce Tess? I think its the later, but I'm not sure ..."

He doesn't specify. Certainly divorce was possible in English law in the 19th century, but very difficult. We only have to look at Charles Dickens, who examined the possibility of divorcing his wife Catherine before coming to the conclusion that he couldn't afford it. It really was only an option for the wealthy.

So there's that, plus the idea that he has a father and a brother who are both clerics, before we get into looking at his own (muddled) moral code. He has also said that he is staying with Tess for a few days to protect her reputation, so it's possible he is trying to spare Tess the ignominy of being a divorced woman.

However Angel Clare does not explain any of these 4 possible reasons - or any others. Tess just had one simple thought: "I thought my confession would give you grounds for that [divorce]."

He doesn't specify. Certainly divorce was possible in English law in the 19th century, but very difficult. We only have to look at Charles Dickens, who examined the possibility of divorcing his wife Catherine before coming to the conclusion that he couldn't afford it. It really was only an option for the wealthy.

So there's that, plus the idea that he has a father and a brother who are both clerics, before we get into looking at his own (muddled) moral code. He has also said that he is staying with Tess for a few days to protect her reputation, so it's possible he is trying to spare Tess the ignominy of being a divorced woman.

However Angel Clare does not explain any of these 4 possible reasons - or any others. Tess just had one simple thought: "I thought my confession would give you grounds for that [divorce]."

Peter wrote: "Bionic Jean wrote: "But Tess had not realised how stubborn Angel could be. After her brief period of happiness she is now reinforced in her conception of the cruel injustice of fate.

“I have no wi..."

Peter, I really like the way you describe Angel. He is a conundrum. It's like he has one foot in the past and one in the future. He admires the pastoral life on the dairy farm, but he also wants to embrace the future. A future where one can go to college to study things other than theology perhaps. In this vein I think Angel represents lots of men who live during times of great technological change.

I think Hardy gives us an explanation for Angel's actions when he says "Within the remote depths of his constitution . . . there lay a hard logical deposit like a vein of metal in soft loam, which turned the edge of everything that attempted to traverse it." This description reminds me of Angel's father. Hardy tells us Rev Clare is a kind man, but he's also intractable. He can't follow his religious brethren as their views modernize and change. Perhaps the apple doesn't fall far from the tree.

“I have no wi..."

Peter, I really like the way you describe Angel. He is a conundrum. It's like he has one foot in the past and one in the future. He admires the pastoral life on the dairy farm, but he also wants to embrace the future. A future where one can go to college to study things other than theology perhaps. In this vein I think Angel represents lots of men who live during times of great technological change.

I think Hardy gives us an explanation for Angel's actions when he says "Within the remote depths of his constitution . . . there lay a hard logical deposit like a vein of metal in soft loam, which turned the edge of everything that attempted to traverse it." This description reminds me of Angel's father. Hardy tells us Rev Clare is a kind man, but he's also intractable. He can't follow his religious brethren as their views modernize and change. Perhaps the apple doesn't fall far from the tree.

Divorce was tough to get, certainly if you had in mind getting married again. Frankly I think people just didn't do it unless you could afford to jump through all the hoops.

Divorce was tough to get, certainly if you had in mind getting married again. Frankly I think people just didn't do it unless you could afford to jump through all the hoops. According to parliament.uk, "Before the mid-19th century the only way of obtaining a full divorce, which allowed re-marriage, was by a Private Act of Parliament. Between 1700 and 1857 there were 314 such Acts, most of them initiated by husbands.

"Divorce was granted by Parliament only for adultery. Wives could only initiate a divorce Bill if the adultery was compounded by life-threatening cruelty. Because of the high costs, only the wealthy could afford this method of ending a marriage.

"A movement for reform of divorce law emerged during the early years of Queen Victoria's reign. In 1853, a Royal Commission recommended the transferral of divorce proceedings from Parliament to a special court.

"These proposals were carried out in the Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857, but the grounds for divorce remained substantially the same. Adultery remained the sole ground for divorce, although wives could now allege cruelty and desertion, in addition to the husband's adultery, in order to obtain a divorce."

But I think that you have something, Jean, about Angel considering what a divorce would say about himself and his family. Better to say nothing and stay separate from Tess.

Thank you so much for the additional references and analysis of King Lear and Hamlet, Erich and Bridget, which enrich our read so much

Thanks too for the chapter and verse for the divorce law at the time Pamela :) I was absolutely sure of my facts, but at nearly midnight couldn't start looking on the Net! As I said, the sheer cost made it an impossibility for ordinary people, before we consider the other reasons I mentioned. I think Angel and the Clare family would be scandalised at the idea.

Tess of course knows no better, as all people above her peasant class would be jumbled up and differentiations vague in her mind. She feels ignorant and guilty, and is subject to Angel's scorn.

Thanks too for the chapter and verse for the divorce law at the time Pamela :) I was absolutely sure of my facts, but at nearly midnight couldn't start looking on the Net! As I said, the sheer cost made it an impossibility for ordinary people, before we consider the other reasons I mentioned. I think Angel and the Clare family would be scandalised at the idea.

Tess of course knows no better, as all people above her peasant class would be jumbled up and differentiations vague in her mind. She feels ignorant and guilty, and is subject to Angel's scorn.

Peter - Like Bridget implied, I don't think you are confused at all! Or rather, your "confusion" reflects Angel Clare's inner turmoil :)

Pankies said "I don't understand exactly what Angel's beliefs and principles are" - well neither does he!

"I think his moral code is more defined by his vanity, his ambitions and his quest for perfection."

That's an interesting viewpoint. I think although he is - 26, were we told? - his attitudes are of a younger man's struggles, and I hope still not fully formed.

Certainly Angel is much more in touch with his own whims and morals than he is with those of other people. He lacks the empathy to see the situation from Tess’s point of view, or even that her only sin is one arbitrarily attributed to her by society, and which in fact was committed against her. I don't think he is "shallow" at heart though - except occasionally his vanity (as you say) gets the better of him, e.g. the d'Urberville name, which can either be a source of pride to him - or something to despise - depending on convenience and circumstances!

Pankies said "I don't understand exactly what Angel's beliefs and principles are" - well neither does he!

"I think his moral code is more defined by his vanity, his ambitions and his quest for perfection."

That's an interesting viewpoint. I think although he is - 26, were we told? - his attitudes are of a younger man's struggles, and I hope still not fully formed.

Certainly Angel is much more in touch with his own whims and morals than he is with those of other people. He lacks the empathy to see the situation from Tess’s point of view, or even that her only sin is one arbitrarily attributed to her by society, and which in fact was committed against her. I don't think he is "shallow" at heart though - except occasionally his vanity (as you say) gets the better of him, e.g. the d'Urberville name, which can either be a source of pride to him - or something to despise - depending on convenience and circumstances!

Angel Clare is conflicted, and it is no use using the reason he values so highly if one's first assumptions are mistaken, as his are about Tess. As Erich says, "the damage he does by following his "principles" is perhaps greater than that inflicted by Alec" and he is often "illogical".

Bridget's quotation was very revealing about this - it struck me at the time too :) Great comparison with his father Bridget!

Bridget's quotation was very revealing about this - it struck me at the time too :) Great comparison with his father Bridget!

Peter - back to your thoughts about the symbolism, which I'm sure are spot on. I mentioned that we have the irony of the flour mill Angel Clare was to visit - ostensibly the reason for them being there - was using out of date methods, and no use for a forward-looking farmer. Yet again we have a favourite Victorian theme in the Industrial Age of tradition v. progress. Angel too is on the cusp in his beliefs and attitudes, and continually crossing the river symbolises this. Remember I said in the information post that Wool Bridge (pictured) or "Wellbridge", is historically important, as the point at which the river Frome could be crossed.

We also have signposts and crossroads at important points of the novel - such as in today's chapter, which we had better move on to :)

We also have signposts and crossroads at important points of the novel - such as in today's chapter, which we had better move on to :)

Chapter 37: Summary

Late that night Angel sleepwalks into Tess’s room and begins to grieve that she is dead. Tess knows that in times of great stress he does things like this, but she does not wake him up. She trusts him so much that even when he is acting unconsciously she feels safe.

The sleeping Angel picks up Tess in her sheet and murmurs endearing words that bring her joy. She is not afraid, as she would not care if she died in his arms this way. He kisses her lips and then carries her outside, towards the river.

Tess is pleased that Angel’s subconscious self still regards her as his wife, and then she thinks he is reenacting the day he carried the girls through the flood to church. He stands at the edge of the deep, fast river [Frome]. The bridge across is only one narrow plank, but Angel starts to cross anyway, and still Tess would prefer to drown together than be separated on the next day. She almost makes a movement to upset his balance, but she values Angel’s life too much to sacrifice it as well as her own.

They reach the Abbey where a stone coffin stands open against the wall. Angel lays Tess inside and kisses her, and then he stretches out on the grass and keeps sleeping. The night is cold enough to be dangerous for them to stay out in the open, but she thinks Angel will be ashamed if she wakes him and reveals what happened. She tries to persuade him to walk on, and he obeys, seeming to think in his dream that she is leading him to Heaven. Tess leads him across the stone bridge, into the house, and back onto the sofa where he sleeps.

The next morning it is clear that Angel remembers nothing of the incident. His resolve to leave Tess remains after his sleep, so he believes this must be his reason and not his passion, so he does not hesitate. Tess wants to tell Angel what happened but knows it would anger him that he showed a passion his reasoning did not approve of. The carriage Angel Clare had ordered by letter picks them up, and they go to bid farewell to the Cricks.

They walk through all the places of their courtship and the green fertility has turned to gray coldness. The other workers tease the couple knowingly, and they pretend that nothing is wrong. Retty and Marian have left the farm; Retty to her father’s, and Marian to look for work elsewhere, although they fear she will come to no good.. Tess says goodbye to her favourite cows and they leave. Mrs. Crick remarks that Tess is strange, and seemed in a dream.

They drive farther and come to the crossroads which leads to Marlott, Tess’s childhood home. Angel assures her that he is not angry, but he feels they cannot be together right now. He says he will write to her, but tells her not to not come to him unless he tells her. Tess feels these conditions are harsh, but she accepts them, and Thomas Hardy tells us that she does not behave in a way which might have persuaded him. He says that her pride might play a factor in this, perhaps as an old d’Urberville fault.

Angel gives Tess some money and takes her jewels to keep safe in the bank, and then they part. Angel hopes she will look back, but Tess is so distraught that she cannot. He remarks on the inherent wrongness of the world, and as he turns away he “hardly knew that he loved her still”.

Late that night Angel sleepwalks into Tess’s room and begins to grieve that she is dead. Tess knows that in times of great stress he does things like this, but she does not wake him up. She trusts him so much that even when he is acting unconsciously she feels safe.

The sleeping Angel picks up Tess in her sheet and murmurs endearing words that bring her joy. She is not afraid, as she would not care if she died in his arms this way. He kisses her lips and then carries her outside, towards the river.

Tess is pleased that Angel’s subconscious self still regards her as his wife, and then she thinks he is reenacting the day he carried the girls through the flood to church. He stands at the edge of the deep, fast river [Frome]. The bridge across is only one narrow plank, but Angel starts to cross anyway, and still Tess would prefer to drown together than be separated on the next day. She almost makes a movement to upset his balance, but she values Angel’s life too much to sacrifice it as well as her own.

They reach the Abbey where a stone coffin stands open against the wall. Angel lays Tess inside and kisses her, and then he stretches out on the grass and keeps sleeping. The night is cold enough to be dangerous for them to stay out in the open, but she thinks Angel will be ashamed if she wakes him and reveals what happened. She tries to persuade him to walk on, and he obeys, seeming to think in his dream that she is leading him to Heaven. Tess leads him across the stone bridge, into the house, and back onto the sofa where he sleeps.

The next morning it is clear that Angel remembers nothing of the incident. His resolve to leave Tess remains after his sleep, so he believes this must be his reason and not his passion, so he does not hesitate. Tess wants to tell Angel what happened but knows it would anger him that he showed a passion his reasoning did not approve of. The carriage Angel Clare had ordered by letter picks them up, and they go to bid farewell to the Cricks.

They walk through all the places of their courtship and the green fertility has turned to gray coldness. The other workers tease the couple knowingly, and they pretend that nothing is wrong. Retty and Marian have left the farm; Retty to her father’s, and Marian to look for work elsewhere, although they fear she will come to no good.. Tess says goodbye to her favourite cows and they leave. Mrs. Crick remarks that Tess is strange, and seemed in a dream.

They drive farther and come to the crossroads which leads to Marlott, Tess’s childhood home. Angel assures her that he is not angry, but he feels they cannot be together right now. He says he will write to her, but tells her not to not come to him unless he tells her. Tess feels these conditions are harsh, but she accepts them, and Thomas Hardy tells us that she does not behave in a way which might have persuaded him. He says that her pride might play a factor in this, perhaps as an old d’Urberville fault.

Angel gives Tess some money and takes her jewels to keep safe in the bank, and then they part. Angel hopes she will look back, but Tess is so distraught that she cannot. He remarks on the inherent wrongness of the world, and as he turns away he “hardly knew that he loved her still”.

Real Life Locations:

This is the actual tombstone where in the novel Angel lays Tess. It is the grave of an abbot at Bindon Abbey. The Cistercian monastery was founded in 1149.

Grave of an abbot on the north side of chancel, popularly known as “Tess’s grave”.

I referenced Bindon Abbey in comment 4, and here is a link to the wiki page about Bindon Abbey which is safe from spoilers!

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bindon_...

This is the actual tombstone where in the novel Angel lays Tess. It is the grave of an abbot at Bindon Abbey. The Cistercian monastery was founded in 1149.

Grave of an abbot on the north side of chancel, popularly known as “Tess’s grave”.

I referenced Bindon Abbey in comment 4, and here is a link to the wiki page about Bindon Abbey which is safe from spoilers!

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bindon_...

Wow - this was a hair-raising chapter. It felt almost gothic!

Yet again we see the superficial pretence each of the couple is keeping up. Just as when he fought the man who had insulted Tess in his sleep, Angel’s true and nobler nature comes out in his subconscious. When he is awake he represses himself with his strict ideals.

Tess’s nature is equally distorted at this point. She becomes a sort of sacrificial figure, one willing do die for love or to spare her loved one pain. And when we are told she could perhaps have used “feminine wiles” to convince Angel, her pride kicks in.

Yet again we see the superficial pretence each of the couple is keeping up. Just as when he fought the man who had insulted Tess in his sleep, Angel’s true and nobler nature comes out in his subconscious. When he is awake he represses himself with his strict ideals.

Tess’s nature is equally distorted at this point. She becomes a sort of sacrificial figure, one willing do die for love or to spare her loved one pain. And when we are told she could perhaps have used “feminine wiles” to convince Angel, her pride kicks in.

I’m sure others have recognised the twisted words of another line from Robert Browning, so I’ll leave that for someone else to analyse, and instead post my favourite passage from this chapter:

“The swift stream raced and gyrated under them, tossing, distorting, and splitting the moon’s reflected face. Spots of froth travelled past, and intercepted weeds waved behind the piles. If they could both fall together into the current now, their arms would be so tightly clasped together that they could not be saved; they would go out of the world almost painlessly, and there would be no more reproach to her, or to him for marrying her.”

What a powerful symbol water is. We have mention of crossing water, or running water at several key points. The river Frome seems to be taking on a life of its own in this novel.

Your thoughts?

“The swift stream raced and gyrated under them, tossing, distorting, and splitting the moon’s reflected face. Spots of froth travelled past, and intercepted weeds waved behind the piles. If they could both fall together into the current now, their arms would be so tightly clasped together that they could not be saved; they would go out of the world almost painlessly, and there would be no more reproach to her, or to him for marrying her.”

What a powerful symbol water is. We have mention of crossing water, or running water at several key points. The river Frome seems to be taking on a life of its own in this novel.

Your thoughts?

Sorry, a bit of an afterthought here: After all the discussion of divorce, it occurred to me to wonder about the possibility of an annulment, which would seem to have been in order, given that the marriage was never consummated and both parties realized the first day that it had all been a dreadful mistake.

Sorry, a bit of an afterthought here: After all the discussion of divorce, it occurred to me to wonder about the possibility of an annulment, which would seem to have been in order, given that the marriage was never consummated and both parties realized the first day that it had all been a dreadful mistake.

Bionic Jean wrote: "Real Life Locations:

This is the actual tombstone where in the novel Angel lays Tess. It is the grave of an abbot at Bindon Abbey. The Cistercian monastery was founded in 1149.

Thank you for this picture, Jean. So chilling to think of Tess laying there. I also liked the section you quoted. I also rather like the way the chapter ends with "and hardly knew he loved her still".

Jim poses a good question about an annulment. I don't have an answer, but I suppose an annulment might be embarrassing or shameful for both parties.

Still seems like it would have been an option for Angel to cast off Tess. Is he protecting her? Or himself? He does tell her he wants to try and bring himself round to accepting her, though does anyone really think he will?

This is the actual tombstone where in the novel Angel lays Tess. It is the grave of an abbot at Bindon Abbey. The Cistercian monastery was founded in 1149.

Thank you for this picture, Jean. So chilling to think of Tess laying there. I also liked the section you quoted. I also rather like the way the chapter ends with "and hardly knew he loved her still".

Jim poses a good question about an annulment. I don't have an answer, but I suppose an annulment might be embarrassing or shameful for both parties.

Still seems like it would have been an option for Angel to cast off Tess. Is he protecting her? Or himself? He does tell her he wants to try and bring himself round to accepting her, though does anyone really think he will?

Books mentioned in this topic

The Return of the Native (other topics)Othello (other topics)

King Lear (other topics)

Hamlet (other topics)

Tess of the D’Urbervilles (other topics)

Authors mentioned in this topic

Thomas Hardy (other topics)Thomas Hardy (other topics)

Thomas Hardy (other topics)

Thomas Hardy (other topics)

Thomas Hardy (other topics)

More...

Phase the Fifth: The Woman Pays: Chapters 35 - 44

Woolbridge Manor House - the inspiration for Wellbridge House—Tess's ancestral home