Classics and the Western Canon discussion

J. S. Mill - Three Works

>

J. S. Mill Week 11 On Liberty V & Book as a Whole

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Mill's first example of a legitimate limitation on liberty with respect to free trade is on the sale of poisons. He acknowledges that while there are legitimate uses for poisons, their potential harm if used incorrectly or maliciously means that society has a right to control them in a reasonable and effective manner. It is interesting that if a measure is not effective, it is considered wrong:

Mill's first example of a legitimate limitation on liberty with respect to free trade is on the sale of poisons. He acknowledges that while there are legitimate uses for poisons, their potential harm if used incorrectly or maliciously means that society has a right to control them in a reasonable and effective manner. It is interesting that if a measure is not effective, it is considered wrong:Restrictions on trade, or on production for purposes of trade, are indeed restraints; and all restraint, quâ restraint, is an evil: but the restraints in question affect only that part of conduct which society is competent to restrain, and are wrong solely because they do not really produce the results which it is desired to produce by them.Does demonstrating the ineffectiveness of restraints provide a loophole to deem it wrong and kill it off, or does it just invite additional restraints?

Mill argues that individuals should have the liberty to produce, buy, and sell poisons, but restrictions may be necessary to protect the buyer/consumer. Mill suggests regulating the seller rather than the buyer with better labeling and seller record keeping of transactions for accountability would not be a significant obstacle to obtaining the poisons, but would prevent improper use without detection.

Armed as we are now with Mill's example regarding the sale of poisons, how could we answer the previously posed question of what Mill would think about laws against selling heroin?

Mill goes on to: reason that individuals should be free to engage in prostitution and gambling, but prohibit pimps and casinos; perform some mental gymnastics to determine liberty forbids the option of willingly becoming a slave; in cases of divorce, the ability to simply dissolve marriages should should not be impeded except in cases of children where the father should be held responsible; support restrictions on child-bearing to prevent harms to the child and the population.

Mill goes on to: reason that individuals should be free to engage in prostitution and gambling, but prohibit pimps and casinos; perform some mental gymnastics to determine liberty forbids the option of willingly becoming a slave; in cases of divorce, the ability to simply dissolve marriages should should not be impeded except in cases of children where the father should be held responsible; support restrictions on child-bearing to prevent harms to the child and the population.Finally when it comes to government welfare, Mill supports leaving things to the people or voluntary associations instead of government. He reasons:

1. Individuals are more likely to have a personal interest in what needs to be done and will be better at it than an impersonal goverment.

2. Even if individuals are not better at the business, leaving it to them builds their character:

. . .a means to their own mental education—a mode of strengthening their active faculties, exercising their judgement, and giving them a familiar knowledge of the subjects with which they are thus left to deal.3. Mill believes it a slippery slope leading to evil by erosion of liberty to start superadding functions to the government that should be performed by individuals and other non-government bodies.

A government cannot have too much of the kind of activity which does not impede, but aids and stimulates, individual exertion and development. The mischief begins when, instead of calling forth the activity and powers of individuals and bodies, it substitutes its own activity for theirs; when, instead of informing, advising, and, upon occasion, denouncing, it makes them work in fetters, or bids them stand aside and does their work instead of them.Question, are Mill's objections to government welfare justified by utilitarianism, or whether some form of limited welfare should be endorsed to protect certain rights and interests."

I guess Mill thinks it's OK for the government to regulate commerce because the exchange of goods is a social act, not a private act. But the exchange of ideas is a social act also, so wouldn't it be logical to let the government regulate the exchange of ideas as well as that of goods?

I guess Mill thinks it's OK for the government to regulate commerce because the exchange of goods is a social act, not a private act. But the exchange of ideas is a social act also, so wouldn't it be logical to let the government regulate the exchange of ideas as well as that of goods?

Roger wrote: "....wouldn't it be logical to let the government regulate the exchange of ideas as well as that of goods ..."

Roger wrote: "....wouldn't it be logical to let the government regulate the exchange of ideas as well as that of goods ..."[grin] ouch! May I presume you are writing this tongue in cheek, Roger?

Who IS "government"?

Lily wrote: "Roger wrote: "....wouldn't it be logical to let the government regulate the exchange of ideas as well as that of goods ..."

Lily wrote: "Roger wrote: "....wouldn't it be logical to let the government regulate the exchange of ideas as well as that of goods ..."[grin] ouch! May I presume you are writing this tongue in cheek, Roger?

..."

I'm wondering if Mill really succeeds in putting his doctrine of liberty on a firm theoretical foundation. It seems like liberty is really one good among many. Maybe liberty of thought and speech should be protected because of its many good consequences, not because of the unique importance of liberty. Maybe liberty of action should more carefully regulated because of the many opportunities for mischief.

Roger wrote: "...Maybe liberty of thought and speech should be protected because of its many good consequences, not because of the unique importance of liberty. Maybe liberty of action should more carefully regulated because of the many opportunities for mischief...."

Roger wrote: "...Maybe liberty of thought and speech should be protected because of its many good consequences, not because of the unique importance of liberty. Maybe liberty of action should more carefully regulated because of the many opportunities for mischief...."I think I follow the zeitgeist of what you write, Roger. However, these recent years, as much as "freedom of speech" seems to be vital to "liberty", I do perceive that speech offers as many opportunities for mischief as does action. (Don't get me started on "woke" or "Marxism/Communism/socialism" or simply "drag/gay" or the multitude of other trigger words so prevalent in our current public arena.)

I suppose it has something to do with the recognition that human action can always be considered to be "encased in speech", whether in its creation or in its fulfillment?

(Non sequitur, but can SVB considered an example of refusal to submit to government regulation of behavior or rather of government willingness modify its rules and then discover such can lead to predictable mischief or of ....?)

Roger wrote: "I guess Mill thinks it's OK for the government to regulate commerce because the exchange of goods is a social act, not a private act. But the exchange of ideas is a social act also, so wouldn't it ..."

Roger wrote: "I guess Mill thinks it's OK for the government to regulate commerce because the exchange of goods is a social act, not a private act. But the exchange of ideas is a social act also, so wouldn't it ..."It is quite true that both commerce and the exchange of ideas are social acts, and it is perfectly logical and appropriate to restrict or limit either one when they are harmful. The justification for restricting speech or trade is not whether it is private or public, but whether it causes harm or not. Mill endorses the harm principle as a basis for government restricting, preventing, or penalizing speech or actions that harm others, such as bullying, fraud or incitement to violence. In our time it has been deemed necessary to close or suspend certain social media accounts that have violated the harm principle and even media outlets have been and are continuing to to be held accountable for defamation.

However, Mill differentiates between the harm principle from the offense principle. The offense principle states that the government should prevent speech that offends or disturbs others, even if it does not cause harm. Mill rejects the offense principle and Instead believes that individuals should be free to express their opinions, even if they are unpopular or offensive, as censorship would limit diversity of opinion and stifle intellectual progress. He contends that the best way to combat bad ideas is through free and open debate, not censorship.

While I agree with Mill's stance in theory but in practice it requires a good amount of fair mindedness free of prejudiced biases from both sides in a debate in practice. Mill accurately described the obstacle in The Subjection of Women when he wrote:

The difficulty is that which exists in all cases in which there is a mass of feeling to be contended against. So long as an opinion is strongly rooted in the feelings, it gains rather than loses in stability by having a preponderating weight of argument against it. For if it were accepted as a result of argument, the refutation of the argument might shake the solidity of the conviction; but when it rests solely on feeling, the worse it fares in argumentative contest, the more persuaded its adherents are that their feeling must have some deeper ground, which the arguments do not reach; and while the feeling remains, it is always throwing up fresh entrenchments of argument to repair any breach made in the old. (The Subjection of Women, I)As a result, positive results may not always be timely or guaranteed.

Lily wrote: "Who IS "government"?"

Lily wrote: "Who IS "government"?"In describing democratic republics, Mill writes:

The ‘people’ who exercise the power are not always the same people with those over whom it is exercised; and the ‘self-government’ spoken of is not the government of each by himself, but of each by all the rest. The will of the people, moreover, practically means the will of the most numerous or the most active part of the people; the majority, or those who succeed in making themselves accepted as the majority

Roger wrote: "Maybe liberty of thought and speech should be protected because of its many good consequences"

Roger wrote: "Maybe liberty of thought and speech should be protected because of its many good consequences"That sounds like a very utilitarian statement. :)

It is true that there may be opportunities for mischief and harm in individual actions, but Mill believed that the government's role should be limited to preventing actions that cause harm to others.

He argued that the government should not regulate actions or speech that are merely offensive or unpopular, as this would infringe on individual autonomy and limit the pursuit of truth. Moreover, he believed that censorship and regulation of speech and action would lead to a loss of diversity of opinion, a stifling of intellectual progress, and an erosion of individual autonomy.

Without individual freedom, Mill feels that it is impossible to pursue other goods, such as, justice, social progress, that contribute to our happiness, i.e., the end of all human action.

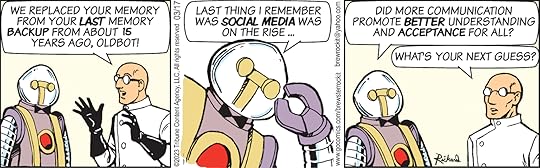

1. The Internet allows everyone with extreme or bizarre ideas to find a critical mass of co-believers.

1. The Internet allows everyone with extreme or bizarre ideas to find a critical mass of co-believers.2. The social distance given by the computer screen allows some to say things they'd hesitate to say to someone's face.

I don't think Mill anticipated any of this.

Roger wrote: "1. The Internet allows everyone with extreme or bizarre ideas to find a critical mass of co-believers.

Roger wrote: "1. The Internet allows everyone with extreme or bizarre ideas to find a critical mass of co-believers.2. The social distance given by the computer screen allows some to say things they'd hesitate..."

While the internet does have its fair share of anonymity emboldened trolls, there are also a significant number of shameless purveyors of misinformation and bullshit who proudly attach their name to it and remain unrepentant, particularly if it is profitable or good for ratings.

It is important to note that this fear of misinformation is not unique to the internet. Similar concerns were raised with newspapers, and then later on as radio, and television each emerged.

The adage about lies spreading rapidly while corrective truths take longer to disseminate has a long history, predating the internet. As early as 1710, Jonathan Swift wrote about this phenomenon.

Besides, as the vilest Writer has his Readers, so the greatest Liar has his Believers; and it often happens, that if a Lie be believ’d only for an Hour, it has done its Work, and there is no farther occasion for it. Falsehood flies, and the Truth comes limping after it; so that when Men come to be undeceiv’d, it is too late; the Jest is over, and the Tale has had its Effect…

1710 November 2 to November 9, The Examiner, Number 15, (Article by Jonathan Swift), Quote Page 2, Column 1, Printed for John Morphew, near Stationers-Hall, London.https://books.google.com/books?id=Kig...

I think, it is unfair to say Mill did not understand that the wrong ideas benefits from freedom of speech. His position is more that risks of censorship is far more dangerous than that of free speech. He spent the good portion of the sections proving this, and I want to say that even with the fuss about social media the recent events definitely prove him right.

I think, it is unfair to say Mill did not understand that the wrong ideas benefits from freedom of speech. His position is more that risks of censorship is far more dangerous than that of free speech. He spent the good portion of the sections proving this, and I want to say that even with the fuss about social media the recent events definitely prove him right.

As for Mill's take on the trade of poisons, I think though his scheme is far from being optimal in preventing harm, implemented properly, it could be effective. As I understand, the main flaw here, as in some his other constructions, is assuming the well developed human being as the actors in society. Unfortunately, my experience demonstrates that people far more better developed than me often acts very differently from what Mill suggested.

As for Mill's take on the trade of poisons, I think though his scheme is far from being optimal in preventing harm, implemented properly, it could be effective. As I understand, the main flaw here, as in some his other constructions, is assuming the well developed human being as the actors in society. Unfortunately, my experience demonstrates that people far more better developed than me often acts very differently from what Mill suggested.

In David's response to Roger: Falsehood flies, and the Truth comes limping after it; so that when Men come to be undeceiv’d, it is too late; the Jest is over, and the Tale has had its Effect… 1710 , (Article by Jonathan Swift),

In David's response to Roger: Falsehood flies, and the Truth comes limping after it; so that when Men come to be undeceiv’d, it is too late; the Jest is over, and the Tale has had its Effect… 1710 , (Article by Jonathan Swift), We can go way back with this one,at least as far as Vergil's Aeneid, where Juno releases the muse Rumour, to slink through the town before her arrival.

Alexey wrote: "As for Mill's take on the trade of poisons, I think though his scheme is far from being optimal. . .the main flaw here, as in some his other constructions, is assuming the well developed human being as the actors in society."

Alexey wrote: "As for Mill's take on the trade of poisons, I think though his scheme is far from being optimal. . .the main flaw here, as in some his other constructions, is assuming the well developed human being as the actors in society."It is true that Mill's ideas assume a certain level of rationality and ethical behavior from individuals in society. Mill explicitly assumes a certain level of responsible maturity, in both individuals and their society as a necessary condition for liberty when he writes:

It is, perhaps, hardly necessary to say that this doctrine is meant to apply only to human beings in the maturity of their faculties. We are not speaking of children, or of young persons below the age which the law may fix as that of manhood or womanhood. Those who are still in a state to require being taken care of by others, must be protected against their own actions as well as against external injury. For the same reason, we may leave out of consideration those backward states of society...Maybe we need to revisit the wretched education system and address the reforms needed today in order to produce a greater percentage of well-developed individuals.

I brought up the example of the sale of poisons to see if there was anything about the conditions and limits proposed in that scenario that might be applicable to the current laws against selling heroin. Anyone?

I brought up the example of the sale of poisons to see if there was anything about the conditions and limits proposed in that scenario that might be applicable to the current laws against selling heroin. Anyone?

Mill writes: "On the other hand, there are questions relating to interference with trade which are essentially questions of liberty; such as the Maine Law, already touched upon; the prohibition of the importation of opium into China; the restriction of the sale of poisons; all cases, in short, where the object of the interference is to make it impossible or difficult to obtain a particular commodity. These interferences are objectionable, not as infringements on the liberty of the producer or seller, but on that of the buyer."

Mill writes: "On the other hand, there are questions relating to interference with trade which are essentially questions of liberty; such as the Maine Law, already touched upon; the prohibition of the importation of opium into China; the restriction of the sale of poisons; all cases, in short, where the object of the interference is to make it impossible or difficult to obtain a particular commodity. These interferences are objectionable, not as infringements on the liberty of the producer or seller, but on that of the buyer."It seems that Mill objected to interference with people's liberty to obtain hard drugs.

Roger wrote: "It seems that Mill objected to interference with people's liberty to obtain hard drugs."

Roger wrote: "It seems that Mill objected to interference with people's liberty to obtain hard drugs."I think Mill may object to interference with people's ability to use hard drugs as far as that would be covered under self-harm, but he would not object to interference in peoples ability to sell them.

The phrase "while there are legitimate uses for poisons" comes into play here and differentiates arsenic, which my notes say is the poison Mill was specifically talking about, from heroin.

Mill argues for some utility in the use of poisons. On the other hand, heroin is highly addictive, carries significant health risks to the individual but also social harms, and most importantly there is no accepted medical use. Therefore heroin is all harm and no utility therefore laws against its sale are justified.

Of course Implicit to this stance is the naive assumption that if it cannot be sold it would not be available for an individual to use. So what additional interference can be justified?

I am not sure about Mill understanding of 'hard drugs', it seems that in that time this category was not defined, and general understanding was a bit murky.

I am not sure about Mill understanding of 'hard drugs', it seems that in that time this category was not defined, and general understanding was a bit murky.And in many jurisdictions today only selling of hard drugs is illegal not consumption or buying them, so it looks like Mill's logic in this case is not so unusual.

Alexey wrote: "And in many jurisdictions today only selling of hard drugs is illegal not consumption or buying them, so it looks like Mill's logic in this case is not so unusual."

Alexey wrote: "And in many jurisdictions today only selling of hard drugs is illegal not consumption or buying them, so it looks like Mill's logic in this case is not so unusual."i agree, and I think Mill's logic, as stemming from his essays, is missing an element of sympathy for the users of such drugs from the perspective they are victims battling some disease by using such drugs.

Sam wrote: "We can go way back with this one,at least as far as Vergil's Aeneid, where Juno releases the muse Rumour, to slink through the town before her arrival.."

Sam wrote: "We can go way back with this one,at least as far as Vergil's Aeneid, where Juno releases the muse Rumour, to slink through the town before her arrival.."Great reference, especially for this group! So the greater speeds of misinformation and disinformation relative to the truth is definitely not a new problem.

David, thanks for leading this discussion of Mill. It was very illuminating for me. I have often heard of Mill, but never actually read his works.

David, thanks for leading this discussion of Mill. It was very illuminating for me. I have often heard of Mill, but never actually read his works.

You are welcome, Roger. And thank you to you, and also Alexy, Donnally, Lily, Sam, and Susanna for participating in he discussions! I'm glad to hear that the discussion sounds as helpful to you as it was for me. I had not read Mill much beyond a few profound sounding quotes until now and I think his works are definitely worth exploring in more depth.

You are welcome, Roger. And thank you to you, and also Alexy, Donnally, Lily, Sam, and Susanna for participating in he discussions! I'm glad to hear that the discussion sounds as helpful to you as it was for me. I had not read Mill much beyond a few profound sounding quotes until now and I think his works are definitely worth exploring in more depth.Mill convinced me of the merits of Utilitarianism. After examining various scenarios, I couldn't find any counter-examples where a case could not be made that "utility" was in some way the end goal. As a result, I feel compelled to provisionally accept that the basis of ethical values lies not in any intuitive, deontological, or metaphysical doctrine, but is rooted in the capacity for happiness and suffering and only learned inductively through personal experience and human experience.

I may give his "Considerations on Representative Government" a read as well since it is included in the text I was reading from. I understand it offers a look into the nature of democracy and the relationship between citizens and their elected representatives.

Remember, we never close these discussions so the conversation can continue for as long as you like. Feel free to keep the discussion going.

It was a very enlightening discussion for me; I am very grateful to everyone for such an opportunity of dipper understanding Mill's philosophy. Particularly, to you, David, for leading the discussion and your persistency in confronting assumptions and hasty conclusions.

It was a very enlightening discussion for me; I am very grateful to everyone for such an opportunity of dipper understanding Mill's philosophy. Particularly, to you, David, for leading the discussion and your persistency in confronting assumptions and hasty conclusions.I am not so convinced in the merit of utilitarianism, but now see how productive this approach can be as the tool for analyses.

Thanks, Alexy! I appreciated your thoughtful contributions in these discussions.

Thanks, Alexy! I appreciated your thoughtful contributions in these discussions.Regarding utilitarianism, I am provisionally convinced of its merit and have found it to be a helpful approach thus far. However, our discussion sobered any thought of utilitarianism as a panacea and the highlighted the challenges of applying it to every situation. I am finding it to be an interesting mindset to approach issues with and another useful framework to consult in making decisions and taking action.

I was not convinced by Mill.

I was not convinced by Mill. First, I don't buy that happiness, however elevated, is the sole end of mankind. To be sure it's a very important goal, and no-one disdains it, but it's not the only thing. There's also righteousness.

Second, I don't buy that the common happiness of mankind is the sole guide to the rightness of actions. For one thing, we have more responsibility towards those closer to us than to those farther away. For another, we have a greater responsibility to avoid harm than to do positive good. Finally, some deeds are wicked regardless of their consequences.

Roger wrote: "There's also righteousness."

Roger wrote: "There's also righteousness."Mill may view righteousness as a means to happiness or in some cases roll righteousness into happiness as a part of it, similar to his view on virtue. However, it's worth noting that while performing righteous acts may bring satisfaction and fulfillment, it also raises questions about the nature of righteousness and its context that highlight the dangers of using a religion or ideology to obfuscate otherwise morally questionable actions.

Are there any examples of righteousness that avoid all of these entanglements?

Certainly there are elements of righteousness that are almost universally agreed on: telling the truth, keeping your word, treating people fairly, protecting the weak, etc.

Certainly there are elements of righteousness that are almost universally agreed on: telling the truth, keeping your word, treating people fairly, protecting the weak, etc.

Roger wrote: "Certainly there are elements of righteousness that are almost universally agreed on: telling the truth, keeping your word, treating people fairly, protecting the weak, etc."

Roger wrote: "Certainly there are elements of righteousness that are almost universally agreed on: telling the truth, keeping your word, treating people fairly, protecting the weak, etc."There is some overlap and while it is true that these elements of righteousness are widely accepted, it is important to consider why we value these actions in the first place. Mill may explain they are valued because of their utility - they promote the greatest good for the greatest number of people. For example, telling the truth and keeping your word can help establish trust and promote social cohesion, which can lead to greater happiness for all involved.

While righteousness may offer a certain level of guidance for ethical behavior, it's important to recognize that it can be subject to personal interpretation and cultural biases. In contrast, the pursuit of happiness as an ethical standard places the emphasis on the well-being and flourishing of individuals and society as a whole, rather than on rigid adherence to a set of what amounts to arbitrary moral principles. By recognizing happiness as the ultimate goal and prioritizing it, we can create a more universal ethical framework.

David wrote: "By recognizing happiness as the ultimate goal and prioritizing it, we can create a more universal ethical framework. ..."

David wrote: "By recognizing happiness as the ultimate goal and prioritizing it, we can create a more universal ethical framework. ..."But doesn't that devolve into "meaning" ascribed to happiness? What are its "universal" attributes? Its ethical ones?

Lily wrote: "But doesn't that devolve into "meaning" ascribed to happiness? What are its "universal" attributes? Its ethical ones?."

Lily wrote: "But doesn't that devolve into "meaning" ascribed to happiness? What are its "universal" attributes? Its ethical ones?."Thanks for your questions, Lily. I cannot help but be reminded of one of my favorite quotes:

. . .so long as a man rides his HOBBY-HORSE peaceably and quietly along the King’s high-way, and neither compels you or me to get up behind him,——pray, Sir, what have either you or I to do with it?I think Mill might agree that the meaning of happiness is subjective, and that individuals should have the freedom to pursue their own versions of happiness as long as it does not harm others. However Mill may add that there are certain universal attributes of happiness that can be identified.

Sterne, Laurence. The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman

For example, happiness is generally associated with positive emotions, such as opportunities for joy, contentment, and fulfillment. It also involves a sense of well-being and satisfaction with one's life circumstances, such as a stable income, good health, and meaningful relationships. These attributes can be seen across cultures and time periods, suggesting that they are universal aspects of human happiness.

Regarding ethical attributes, Mill might say that happiness, as the ultimate end should be pursued in conjunction with other ethical considerations, such as justice, fairness, and the well-being of others as means to, or part of, happiness. Conversely, pursuing happiness at the expense of others or their interests is not a truly ethical pursuit of happiness.

Some aspects of what people commonly call righteousness certainly do vary culturally, though others do not. In the same way, some aspects of what people commonly call happiness vary culturally. Mill thought the highest form of happiness was that sought by civilized, cultured, genteel men like himself and his friends.

Some aspects of what people commonly call righteousness certainly do vary culturally, though others do not. In the same way, some aspects of what people commonly call happiness vary culturally. Mill thought the highest form of happiness was that sought by civilized, cultured, genteel men like himself and his friends. Like Kant with his categorical imperative, Mill is trying to put the rules of morality on a firm theoretical footing without appealing to a divine lawgiver, I guess. I doubt it's possible. People have good impulses, and desire wholesome happiness, but also have very evil impulses and desire debased happiness. To distinguish the good from the bad we need some rule outside the impulses themselves.

What stunned me is that Mill seems to reject but then co-opt divine command it by claiming God operates on utilitarian principles when he wrote,

What stunned me is that Mill seems to reject but then co-opt divine command it by claiming God operates on utilitarian principles when he wrote,If it be a true belief that God desires, above all things, the happiness of his creatures, and that this was his purpose in their creation, utility is not only not a godless doctrine, but more profoundly religious than any other.Mill then suggests that some see utilitarianism is god's framework or model for mankind to figure morality out on their own,

But others besides utilitarians have been of opinion that the Christian revelation was intended, and is fitted, to inform the hearts and minds of mankind with a spirit which should enable them to find for themselves what is right, and incline them to do it when found, rather than to tell them, except in a very general way, what it is: and that we need a doctrine of ethics [utilitarianism], carefully followed out, to interpret to us the will of God.From my own perspective, the foundation of morality will always be a matter of debate; the fact that people are capable of making moral judgments and acting in accordance with ethical principles is not.

Thank you David, for pointing this out. In my view, anyone who claims his particular moral basis is the word of God is treading on very dangerous ground.

Thank you David, for pointing this out. In my view, anyone who claims his particular moral basis is the word of God is treading on very dangerous ground.

Donnally wrote: "Thank you David, for pointing this out. In my view, anyone who claims his particular moral basis is the word of God is treading on very dangerous ground."

Donnally wrote: "Thank you David, for pointing this out. In my view, anyone who claims his particular moral basis is the word of God is treading on very dangerous ground."Excellent point, and I agree. But technically Mill argues not from the divine command horn of the Euthyphro Dilemma, but from the "independent standard" horn.

1. The first horn asserts that something is good because God commands it. This means that morality is dependent on God's arbitrary will, and that there is no independent standard for morality beyond God's commands. This option is known as divine command theory most commonly associated with a lawgiver

2. The second horn is that God commands something because it is good. This means that there is an independent standard for morality that exists independently of God's will, and that God's commands are based on that standard. This option is sometimes called the "independent standard" view. This view does not require a deity for a moral doctrine, but Mill still claims one.

Mill takes the independent standard view and cleverly poses and "if-then" statement:

If it be a true belief that God desires, above all things, the happiness of his creatures, and that this was his purpose in their creation, [then] utility is not only not a godless doctrine, but more profoundly religious than any other.The danger pointed out is that Mill chooses an argument that claims to know what a supreme deity desires and based on that argument claims utilitarianism as the most profoundly religious doctrine. If it were true, I would instead say there is a whole lot of unhappy maximized suffering to account for.

But we should keep in mind, Mill went to great pains to demonstrate the ultimate authority for utilitarianism was human conscience, and if lacking that, social pressure. Did he just throw in the independent view to answer those claiming utilitarianism is a godless doctrine?

Chapter V: Applications

Mill starts with a couple of general rules of thumb: 1) An individual is not accountable to society for actions concerning only themselves. 2) For actions that harm others, individual may face social or legal punishment if society deems it necessary for protection.

Mill recognizes that there are exceptions to the principle of individual liberty in cases beyond an individual's control. These exceptions include instances of bad social institutions, such as discriminatory laws or practices, unequal distribution of resources, or oppressive social norms. Additionally, there are situations where certain actions will unavoidably harm the interests of others must be accepted, such as the unsuccessful job applicants for a limited number of jobs. In these cases, Mill suggests that society should only intervene if the means of success employed are fraudulent, treacherous, or forceful, and go against the general interest of mankind.

Next Mill argues that trade is a social act and while the principle free trade, allowing individuals and businesses to trade goods and services without restrictions, is distinct from the principle of libery, free trade may be controlled within legitimate limitations of liberty.