Jane Austen's Books & Adaptations discussion

Non-fiction & Documentaries

>

Victorians on Jane Austen

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

message 1:

by

Zuzana

(new)

Sep 06, 2025 07:28AM

Mod

Mod

reply

|

flag

Anthony Trollope

from An Autobiography by Anthony Trollope:

The writer of stories must please, or he will be nothing. And he must teach whether he wish to teach or no. How shall he teach lessons of virtue and at the same time make himself a delight to his readers? That sermons are not in themselves often thought to be agreeable we all know. Nor are disquisitions on moral philosophy supposed to be pleasant reading for our idle hours. But the novelist, if he have a conscience, must preach his sermons with the same purpose as the clergyman, and must have his own system of ethics. If he can do this efficiently, if he can make virtue alluring and vice ugly, while he charms his readers instead of wearying them, then I think Mr. Carlyle need not call him distressed, nor talk of that long ear of fiction, nor question whether he be or not the most foolish of existing mortals.

I think that many have done so; so many that we English novelists may boast as a class that such has been the general result of our own work. Looking back to the past generation, I may say with certainty that such was the operation of the novels of Miss Edgeworth, Miss Austen, and Walter Scott. Coming down to my own times, I find such to have been the teaching of Thackeray, of Dickens, and of George Eliot. Speaking, as I shall speak to any who may read these words, with that absence of self-personality which the dead may claim, I will boast that such has been the result of my own writing. Can any one by search through the works of the six great English novelists I have named, find a scene, a passage, or a word that would teach a girl to be immodest, or a man to be dishonest? When men in their pages have been described as dishonest and women as immodest, have they not ever been punished? It is not for the novelist to say, baldly and simply: "Because you lied here, or were heartless there, because you Lydia Bennet forgot the lessons of your honest home, or you Earl Leicester were false through your ambition, or you Beatrix loved too well the glitter of the world, therefore you shall be scourged with scourges either in this world or in the next;" but it is for him to show, as he carries on his tale, that his Lydia, or his Leicester, or his Beatrix, will be dishonoured in the estimation of all readers by his or her vices. Let a woman be drawn clever, beautiful, attractive,—so as to make men love her, and women almost envy her,—and let her be made also heartless, unfeminine, and ambitious of evil grandeur, as was Beatrix, what a danger is there not in such a character! To the novelist who shall handle it, what peril of doing harm! But if at last it have been so handled that every girl who reads of Beatrix shall say: "Oh! not like that;—let me not be like that!" and that every youth shall say: "Let me not have such a one as that to press my bosom, anything rather than that!"—then will not the novelist have preached his sermon as perhaps no clergyman can preach it?

An Autobiography — Chapter XII On Novels and the Art of Writing Them

“I had already made up my mind that Pride and Prejudice was the best novel in the English language,—a palm which I only partially withdrew after a second reading of Ivanhoe, and did not completely bestow elsewhere till Esmond was written.”

An Autobiography — Chapter XIII On English Novelists of the Present Day

“Among English novels of the last century, I am inclined to think that Pride and Prejudice is the best. There may be no scene in it equal to the grave-digging in Hamlet, or to the death of Lady Macbeth, or, if you will, to the trial scene in Pickwick; but it is a complete and perfect work of art, and it is in that respect that it excels almost all other novels.”

“The story is thoroughly well told. The reader’s attention is never carried off from Elizabeth and her fortunes,—never wanders, as it so often does in Pendennis, in Vanity Fair, and in The Newcomes. Elizabeth, Darcy, Jane, Bingley, and Lady Catherine de Bourgh are perfectly drawn, and so is Mr. Collins; but the merit is not in single characters, or even in many, but in the grouping of them, and in the nice delineation of shades of character which it would seem almost impossible to catch. That which is here done, as so much else was done by Shakespeare, with absolute perfection, is done beyond Shakespeare’s power, and is done here,—by a young lady!”

“I do not say that she has created anything so powerful, or has even so depicted character, as Shakespeare has done; but she has had her own success, and a very wonderful one it has been.”

Project Gutenberg: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/5978/...

JASNA: “My Chief Favourite among Novelists”: Jane Austen and Anthony Trollope

https://jasna.org/publications-2/pers...

From Saint Paul's Magazine, vol. 5, "Jane Austen", (who was the author?We don't know, but Trollope was the editor of this magazine. See bellow - it was Mrs. Pollock) https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?i...

From The Letters of Anthony Trollope

To Richard Bentley 20 November 1869

On behalf of Mrs. Pollock and Saint Pauls Trollope asks for a review copy of ‘a life of my chief favourite among novelists, Jane Austen’. (The book was J. E. Austen-Leigh’s 4 Memoir of Jane Austen (1870). Mrs. Pollock’s article was ‘Jane Austen’, v (March 1870), 631-43.)

Is it Julia Pollock? The wife of Trollope's friend William Frederick Pollock. Yes, it was her!

Trollope's Conservatism by J. Halperin in Jane Austen's Lovers: And Other Studies in Fiction and History from Austen to le Carré

on Trollope's "Can You Forgive Her?"

"The Westminster Review observed this quickly enough. In its notice of the novel the writer declared that Alice "has, half-consciously, become deeply infected with the nineteenthcentury idea that there was something important to do with her life/'26 It is worth noting that Trollope was reading Emma in 1864 as he was writing Can You Forgive Her? and spoke admiringly of the way in which Jane Austen exposed the "folly," "vanity," and "ignorance" of "the female character."

"Some recent critics have thought that Trollope often depicts women as members of an oppressed second sex. Certainly he shows them, as Jane Austen did, being dependent upon men and marriage for any sort of real freedom in their lives; but he also shows them, in many cases, getting the better of recalcitrant parents and finding the means to manipulate slowerwitted lovers. To depict women as economically and socially dependent upon men was nothing new in the English novel. But Trollope never goes beyond this, as some novelists did, to argue for women's rights; and critics have sometimes interpreted the close sympathy he gives many of his heroines as a political statement instead of what in fact it is: fascination with female psychology and the pathology of physical attraction. Again and again Trollope goes out of his way to satirize the agitation for women's rights. An interest in women need not, after all, be a political statement. The anti-feminist sentiments of Can You Forgive Her? are by no means anomalous in Trollope's work."

from An Autobiography by Anthony Trollope:

The writer of stories must please, or he will be nothing. And he must teach whether he wish to teach or no. How shall he teach lessons of virtue and at the same time make himself a delight to his readers? That sermons are not in themselves often thought to be agreeable we all know. Nor are disquisitions on moral philosophy supposed to be pleasant reading for our idle hours. But the novelist, if he have a conscience, must preach his sermons with the same purpose as the clergyman, and must have his own system of ethics. If he can do this efficiently, if he can make virtue alluring and vice ugly, while he charms his readers instead of wearying them, then I think Mr. Carlyle need not call him distressed, nor talk of that long ear of fiction, nor question whether he be or not the most foolish of existing mortals.

I think that many have done so; so many that we English novelists may boast as a class that such has been the general result of our own work. Looking back to the past generation, I may say with certainty that such was the operation of the novels of Miss Edgeworth, Miss Austen, and Walter Scott. Coming down to my own times, I find such to have been the teaching of Thackeray, of Dickens, and of George Eliot. Speaking, as I shall speak to any who may read these words, with that absence of self-personality which the dead may claim, I will boast that such has been the result of my own writing. Can any one by search through the works of the six great English novelists I have named, find a scene, a passage, or a word that would teach a girl to be immodest, or a man to be dishonest? When men in their pages have been described as dishonest and women as immodest, have they not ever been punished? It is not for the novelist to say, baldly and simply: "Because you lied here, or were heartless there, because you Lydia Bennet forgot the lessons of your honest home, or you Earl Leicester were false through your ambition, or you Beatrix loved too well the glitter of the world, therefore you shall be scourged with scourges either in this world or in the next;" but it is for him to show, as he carries on his tale, that his Lydia, or his Leicester, or his Beatrix, will be dishonoured in the estimation of all readers by his or her vices. Let a woman be drawn clever, beautiful, attractive,—so as to make men love her, and women almost envy her,—and let her be made also heartless, unfeminine, and ambitious of evil grandeur, as was Beatrix, what a danger is there not in such a character! To the novelist who shall handle it, what peril of doing harm! But if at last it have been so handled that every girl who reads of Beatrix shall say: "Oh! not like that;—let me not be like that!" and that every youth shall say: "Let me not have such a one as that to press my bosom, anything rather than that!"—then will not the novelist have preached his sermon as perhaps no clergyman can preach it?

An Autobiography — Chapter XII On Novels and the Art of Writing Them

“I had already made up my mind that Pride and Prejudice was the best novel in the English language,—a palm which I only partially withdrew after a second reading of Ivanhoe, and did not completely bestow elsewhere till Esmond was written.”

An Autobiography — Chapter XIII On English Novelists of the Present Day

“Among English novels of the last century, I am inclined to think that Pride and Prejudice is the best. There may be no scene in it equal to the grave-digging in Hamlet, or to the death of Lady Macbeth, or, if you will, to the trial scene in Pickwick; but it is a complete and perfect work of art, and it is in that respect that it excels almost all other novels.”

“The story is thoroughly well told. The reader’s attention is never carried off from Elizabeth and her fortunes,—never wanders, as it so often does in Pendennis, in Vanity Fair, and in The Newcomes. Elizabeth, Darcy, Jane, Bingley, and Lady Catherine de Bourgh are perfectly drawn, and so is Mr. Collins; but the merit is not in single characters, or even in many, but in the grouping of them, and in the nice delineation of shades of character which it would seem almost impossible to catch. That which is here done, as so much else was done by Shakespeare, with absolute perfection, is done beyond Shakespeare’s power, and is done here,—by a young lady!”

“I do not say that she has created anything so powerful, or has even so depicted character, as Shakespeare has done; but she has had her own success, and a very wonderful one it has been.”

Project Gutenberg: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/5978/...

JASNA: “My Chief Favourite among Novelists”: Jane Austen and Anthony Trollope

https://jasna.org/publications-2/pers...

From Saint Paul's Magazine, vol. 5, "Jane Austen", (who was the author?

From The Letters of Anthony Trollope

To Richard Bentley 20 November 1869

On behalf of Mrs. Pollock and Saint Pauls Trollope asks for a review copy of ‘a life of my chief favourite among novelists, Jane Austen’. (The book was J. E. Austen-Leigh’s 4 Memoir of Jane Austen (1870). Mrs. Pollock’s article was ‘Jane Austen’, v (March 1870), 631-43.)

Is it Julia Pollock? The wife of Trollope's friend William Frederick Pollock. Yes, it was her!

Trollope's Conservatism by J. Halperin in Jane Austen's Lovers: And Other Studies in Fiction and History from Austen to le Carré

on Trollope's "Can You Forgive Her?"

"The Westminster Review observed this quickly enough. In its notice of the novel the writer declared that Alice "has, half-consciously, become deeply infected with the nineteenthcentury idea that there was something important to do with her life/'26 It is worth noting that Trollope was reading Emma in 1864 as he was writing Can You Forgive Her? and spoke admiringly of the way in which Jane Austen exposed the "folly," "vanity," and "ignorance" of "the female character."

"Some recent critics have thought that Trollope often depicts women as members of an oppressed second sex. Certainly he shows them, as Jane Austen did, being dependent upon men and marriage for any sort of real freedom in their lives; but he also shows them, in many cases, getting the better of recalcitrant parents and finding the means to manipulate slowerwitted lovers. To depict women as economically and socially dependent upon men was nothing new in the English novel. But Trollope never goes beyond this, as some novelists did, to argue for women's rights; and critics have sometimes interpreted the close sympathy he gives many of his heroines as a political statement instead of what in fact it is: fascination with female psychology and the pathology of physical attraction. Again and again Trollope goes out of his way to satirize the agitation for women's rights. An interest in women need not, after all, be a political statement. The anti-feminist sentiments of Can You Forgive Her? are by no means anomalous in Trollope's work."

Charles Dickens very likely didn't read Jane Austen

In John Forster's bio, we find one mention of Jane Austen in which he queries, as he often did when proofreading. He mentions some similarities of the characters in Nicholas Nickleby (Mrs. Nickleby and Miss Knag) to Jane Austen's Mrs Bates in Emma and was told he had not read Emma.

"I told him, on reading the first dialogue of Mrs. Nickleby and Miss Knag, that he had been lately reading Miss Bates in Emma, but I found that he had not at this time made the acquaintance of that fine writer."

Quote from The Life of Charles Dickens Vol 1 Chapter 9, page 167

In John Forster's bio, we find one mention of Jane Austen in which he queries, as he often did when proofreading. He mentions some similarities of the characters in Nicholas Nickleby (Mrs. Nickleby and Miss Knag) to Jane Austen's Mrs Bates in Emma and was told he had not read Emma.

"I told him, on reading the first dialogue of Mrs. Nickleby and Miss Knag, that he had been lately reading Miss Bates in Emma, but I found that he had not at this time made the acquaintance of that fine writer."

Quote from The Life of Charles Dickens Vol 1 Chapter 9, page 167

G H Lewes

an influential essay The Novels of Jane Austen

an influential essay The Lady Novelists: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?i...

his letters to and from Charlotte Brontë

https://imgur.com/a/t1OJs0X

an influential essay The Novels of Jane Austen

an influential essay The Lady Novelists: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?i...

his letters to and from Charlotte Brontë

https://imgur.com/a/t1OJs0X

George Eliot

"Without Austen, No Eliot" By Rebecca Mead

The New Yorker, January 28, 2013

In 1852, George Henry Lewes, the literary critic, sometime novelist, amateur scientist, and all-round man of letters, contributed an essay to the Westminster Review titled “The Lady Novelists.” In it, Lewes gave a survey of what he called “the field of female literature,” touching down upon the works of George Sand, Mrs. Gaskell, Charlotte Brontë—and Jane Austen, whose novels he had been championing for years. Austen, Lewes argued, was “the greatest artist that has ever written, using the term to signify the most perfect mastery over the means to her end.”

There were spheres of life that Austen did not attempt to depict, Lewes went on to say: she was always an English countrywoman describing the lives of other English countrywomen. But “her world is a perfect orb and vital,” he wrote. “To read one of her books is like an actual experience of life.” As well as praising the veracity of her work, Lewes admired its “special quality of womanliness,” which, he suggested, no male pseudonym could have disguised. She is not doctrinaire; there is “not a trace of woman’s ‘mission’” about her. In sum, Lewes wrote, “as the most truthful, charming, humorous, pure-minded, quick-witted and unexaggerated of writers, female literature has reason to be proud of her.”

Lewes’s essay, which echoes Austen’s own famous characterization of her art—as social miniatures, produced on two inches of ivory—would be notable as an early and perceptive analysis of Austen’s contribution to literature, with or without the qualification of gender. But what makes it particularly piquant is the name of the editor who commissioned him to write it: Marian Evans, the formidable literary critic and translator who within a few years would herself become a writer of fiction under the pseudonym of George Eliot. Even more suggestive is the fact that not long after writing this essay, Lewes and Evans were to embark upon one of the most notorious and productive literary love affairs of the nineteenth century—eloping to Germany in the fall of 1854, and living together as husband and wife for a quarter of a century, even though Lewes already had a wife, Agnes, from whom divorce was impossible. Talking about Jane Austen was one of the ways in which this high-strung, bohemian, and dauntingly intelligent couple fell in love.

And reading Jane Austen was part of the process by which Marian Evans left essay writing behind. In the spring of 1857, she reread Austen’s novels in the evenings, while during the day she worked on the stories that would become her first published work of fiction, “Scenes of Clerical Life.” In her fiction, of course, Eliot would go on to do all the things that Lewes praised Austen for not doing. She often wrote about worlds of which she had no first-hand experience, with lesser and greater success. (“Romola,” her novel about Renaissance Italy, is little loved by readers beyond those in English literature departments; “Daniel Deronda,” which depicts both British aristocrats and European Jews, is riveting.) Until her true identity was revealed, she fooled just about everyone with her male pseudonym (though Charles Dickens figured her out early). And in contrast with Austen’s light touch, Eliot occasionally ran the risk of being doctrinaire—a worthwhile danger when one believes as earnestly as she did in the improving powers of literature, and the way in which a novel might change a reader’s life.

So without Austen, no Eliot—and even if the debt is sometimes obscured, it continues to resonate through Eliot’s own evolution. Could there be a more Austenesque scenario than the beginning of “Middlemarch,” which presents two young, well-born, unmarried women recently arrived in a country neighborhood, one of them filled with sense and the other brimming with sensibility? (It’s fun to speculate about what Austen would have done with the premise: in her hands, I suspect, Casaubon would have been consigned to Mr. Collins-like irrelevance, Ladislaw would have turned out to be a Wickham-like scoundrel, while Lydgate would have emerged as a Darcy-like dark horse.) Writing within her perfect orb, Austen gave Eliot the space to imagine what might be accomplished beyond that limitation—and gave the same to generations of women writers that have followed her, novelists and otherwise. (There can be few writers of long-form journalism who have not sought to emulate Austen’s perfect, ironic snap.) Eventually, we might even hope, unexamined prejudice about what women can or cannot achieve will finally be displaced by something closer to universally-acknowledged pride.

Source: https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-...

"Without Austen, No Eliot" By Rebecca Mead

The New Yorker, January 28, 2013

In 1852, George Henry Lewes, the literary critic, sometime novelist, amateur scientist, and all-round man of letters, contributed an essay to the Westminster Review titled “The Lady Novelists.” In it, Lewes gave a survey of what he called “the field of female literature,” touching down upon the works of George Sand, Mrs. Gaskell, Charlotte Brontë—and Jane Austen, whose novels he had been championing for years. Austen, Lewes argued, was “the greatest artist that has ever written, using the term to signify the most perfect mastery over the means to her end.”

There were spheres of life that Austen did not attempt to depict, Lewes went on to say: she was always an English countrywoman describing the lives of other English countrywomen. But “her world is a perfect orb and vital,” he wrote. “To read one of her books is like an actual experience of life.” As well as praising the veracity of her work, Lewes admired its “special quality of womanliness,” which, he suggested, no male pseudonym could have disguised. She is not doctrinaire; there is “not a trace of woman’s ‘mission’” about her. In sum, Lewes wrote, “as the most truthful, charming, humorous, pure-minded, quick-witted and unexaggerated of writers, female literature has reason to be proud of her.”

Lewes’s essay, which echoes Austen’s own famous characterization of her art—as social miniatures, produced on two inches of ivory—would be notable as an early and perceptive analysis of Austen’s contribution to literature, with or without the qualification of gender. But what makes it particularly piquant is the name of the editor who commissioned him to write it: Marian Evans, the formidable literary critic and translator who within a few years would herself become a writer of fiction under the pseudonym of George Eliot. Even more suggestive is the fact that not long after writing this essay, Lewes and Evans were to embark upon one of the most notorious and productive literary love affairs of the nineteenth century—eloping to Germany in the fall of 1854, and living together as husband and wife for a quarter of a century, even though Lewes already had a wife, Agnes, from whom divorce was impossible. Talking about Jane Austen was one of the ways in which this high-strung, bohemian, and dauntingly intelligent couple fell in love.

And reading Jane Austen was part of the process by which Marian Evans left essay writing behind. In the spring of 1857, she reread Austen’s novels in the evenings, while during the day she worked on the stories that would become her first published work of fiction, “Scenes of Clerical Life.” In her fiction, of course, Eliot would go on to do all the things that Lewes praised Austen for not doing. She often wrote about worlds of which she had no first-hand experience, with lesser and greater success. (“Romola,” her novel about Renaissance Italy, is little loved by readers beyond those in English literature departments; “Daniel Deronda,” which depicts both British aristocrats and European Jews, is riveting.) Until her true identity was revealed, she fooled just about everyone with her male pseudonym (though Charles Dickens figured her out early). And in contrast with Austen’s light touch, Eliot occasionally ran the risk of being doctrinaire—a worthwhile danger when one believes as earnestly as she did in the improving powers of literature, and the way in which a novel might change a reader’s life.

So without Austen, no Eliot—and even if the debt is sometimes obscured, it continues to resonate through Eliot’s own evolution. Could there be a more Austenesque scenario than the beginning of “Middlemarch,” which presents two young, well-born, unmarried women recently arrived in a country neighborhood, one of them filled with sense and the other brimming with sensibility? (It’s fun to speculate about what Austen would have done with the premise: in her hands, I suspect, Casaubon would have been consigned to Mr. Collins-like irrelevance, Ladislaw would have turned out to be a Wickham-like scoundrel, while Lydgate would have emerged as a Darcy-like dark horse.) Writing within her perfect orb, Austen gave Eliot the space to imagine what might be accomplished beyond that limitation—and gave the same to generations of women writers that have followed her, novelists and otherwise. (There can be few writers of long-form journalism who have not sought to emulate Austen’s perfect, ironic snap.) Eventually, we might even hope, unexamined prejudice about what women can or cannot achieve will finally be displaced by something closer to universally-acknowledged pride.

Source: https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-...

Goldwin Smith 1823-1910

- "devout Anglo-Saxonist", "the most vicious anti-Semite in the English-speaking world", strongly opposed to the women's suffrage movement

The Life of Jane Austen (1890)

Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/lifeofjan...

- "devout Anglo-Saxonist", "the most vicious anti-Semite in the English-speaking world", strongly opposed to the women's suffrage movement

The Life of Jane Austen (1890)

Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/lifeofjan...

Walter Herries Pollock

Jane Austen, her Contemporaries and Herself (1899)

https://archive.org/details/janeauste...

Jane Austen, her Contemporaries and Herself (1899)

https://archive.org/details/janeauste...

Elizabeth Wordsworth

Dame Elizabeth Wordsworth DBE (22 June 1840 – 30 November 1932) was founding Principal of Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford and she funded and founded St Hugh's College. She was also an author, sometimes writing under the name Grant Lloyd.

Essays, old and new (1919)

https://archive.org/details/essaysold...

Dame Elizabeth Wordsworth DBE (22 June 1840 – 30 November 1932) was founding Principal of Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford and she funded and founded St Hugh's College. She was also an author, sometimes writing under the name Grant Lloyd.

Essays, old and new (1919)

https://archive.org/details/essaysold...

Anne (Anna) Thackeray Ritchie

From an island; a story and some essays (1877):

Essay "Jane Austen"

https://archive.org/details/fromislan...

A Book of Sibyls: Mrs. Barbauld, Miss Edgeworth, Mrs. Opie, Miss Austen

"Jane Austen", Cornhill Magazine, 24, 1871, p. 158

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?i...

Leslie Stephen, in the Mausoleum Book, describes how his brother, Fitzjames Stephen, compared Anny to Austen in a review of one of Anny’s stories in 1867. Leslie Stephen also compared Ritchie’s artistic creativity with that of Austen in his Dictionary of National Biography (London: Smith, Elder & Co., 1903).

From an island; a story and some essays (1877):

Essay "Jane Austen"

https://archive.org/details/fromislan...

A Book of Sibyls: Mrs. Barbauld, Miss Edgeworth, Mrs. Opie, Miss Austen

"Jane Austen", Cornhill Magazine, 24, 1871, p. 158

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?i...

Leslie Stephen, in the Mausoleum Book, describes how his brother, Fitzjames Stephen, compared Anny to Austen in a review of one of Anny’s stories in 1867. Leslie Stephen also compared Ritchie’s artistic creativity with that of Austen in his Dictionary of National Biography (London: Smith, Elder & Co., 1903).

Julia Kavanagh

English Women of Letters

[unsigned essay] "Miss Austen and Miss Mitford", Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, 107, 1870, p. 290

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?i...

!!!

There’s no record in the Wellesley Index to Victorian Periodicals of Julia Kavanagh contributing to Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine. Wellesley instead attributes the essay to Margaret Oliphant, who was a regular, almost house-critic at Blackwood’s.

Oliphant wrote hundreds of articles for Blackwood’s, especially on literary topics.

She often handled pieces on women writers, domestic fiction, and cultural retrospectives.

Stylistic analysis of “Miss Austen and Miss Mitford” matches Oliphant’s other essays of the same period.

Wellesley Index (vol. 1, 1966) firmly attributes the essay to Oliphant, not Kavanagh.

English Women of Letters

[unsigned essay] "Miss Austen and Miss Mitford", Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, 107, 1870, p. 290

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?i...

!!!

There’s no record in the Wellesley Index to Victorian Periodicals of Julia Kavanagh contributing to Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine. Wellesley instead attributes the essay to Margaret Oliphant, who was a regular, almost house-critic at Blackwood’s.

Oliphant wrote hundreds of articles for Blackwood’s, especially on literary topics.

She often handled pieces on women writers, domestic fiction, and cultural retrospectives.

Stylistic analysis of “Miss Austen and Miss Mitford” matches Oliphant’s other essays of the same period.

Wellesley Index (vol. 1, 1966) firmly attributes the essay to Oliphant, not Kavanagh.

(Lesley Stephen) Leslie Stephen

"Humour", (unsigned), Cornhill Magazine, 33, 1876

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?i...

Hours in a Library (only mentions)

absolutely non-complimentary :)

James Fitzjames Stephen (his brother)

prefered Emma to Jane Eyre. :)

written by Leslie Stephen about his brother: In literary matters I notice that he does not think the poetry of Byron of a 'high order'; that he reads some essays of Shelley, which are unanimously voted 'unsatisfactory'; that he denies that Tennyson's 'Princess' shows higher powers than the early poems (a rather ambiguous phrase); that he considers Adam, not Satan, to be the hero of 'Paradise Lost'; and, more characteristically, that he regards the novels of the present day as 'degenerate,' and, on his last appearance, maintains the superiority of Miss Austen's 'Emma' to Miss Brontë's [104]'Jane Eyre.' 'Jane Eyre' had then, I remember, some especially passionate admirers at Cambridge.

"Humour", (unsigned), Cornhill Magazine, 33, 1876

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?i...

Hours in a Library (only mentions)

absolutely non-complimentary :)

James Fitzjames Stephen (his brother)

prefered Emma to Jane Eyre. :)

written by Leslie Stephen about his brother: In literary matters I notice that he does not think the poetry of Byron of a 'high order'; that he reads some essays of Shelley, which are unanimously voted 'unsatisfactory'; that he denies that Tennyson's 'Princess' shows higher powers than the early poems (a rather ambiguous phrase); that he considers Adam, not Satan, to be the hero of 'Paradise Lost'; and, more characteristically, that he regards the novels of the present day as 'degenerate,' and, on his last appearance, maintains the superiority of Miss Austen's 'Emma' to Miss Brontë's [104]'Jane Eyre.' 'Jane Eyre' had then, I remember, some especially passionate admirers at Cambridge.

Richard Simpson (1820-1876)

wiki: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard...

"Jane Austen" (Unsigned review of Austen-Leigh's Memoir)

North British Review, 52, April 1870, p. 129 (147)

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?i...

wiki: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard...

"Jane Austen" (Unsigned review of Austen-Leigh's Memoir)

North British Review, 52, April 1870, p. 129 (147)

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?i...

George Eliot - George Eliot’s Life, as Related in her Letters and Journals

Letter to Miss Sara Hennell, Wednesday, 2d June, 1852.

I am bothered to death with article-reading and scrap-work of all sorts: it is clear my poor head will never produce anything under these circumstances; but I am patient. I am ashamed to tease you so, but I must beg of you to send me George Sand's works; and also I shall be grateful if you will lend me—what I think you have—an English edition of "Corinne," and Miss Austen's "Sense and Sensibility." Harriet Martineau's article on "Niebuhr" will not go in the July number. I am sorry for it; it is admirable. After all, she is a trump—the only Englishwoman that possesses thoroughly the art of writing.

***

"September, 1856, made a new era in my life, for it was then I began to write fiction. It had always been a vague dream of mine that some time or other I might write a novel; and my shadowy conception of what the novel was to be, varied, of course, from one epoch of my life to another. But I never went further towards the actual writing of the novel than an introductory chapter describing a Staffordshire village and the life of the neighboring farm-houses; and as the years passed on I lost any hope that I should ever be able to write a novel, just as I desponded about everything else in my future life. I always thought I was deficient in dramatic power, both of construction and dialogue, but I felt I should be at my ease in the descriptive parts of a novel. My "introductory chapter" was pure description, though there were good materials in it for dramatic presentation. It happened to be among the papers I had with me in Germany, and one evening at Berlin something led me to read it to George. He was struck with it as a bit of concrete description, and it suggested to him the possibility of my being able to write a novel, though he distrusted—indeed, disbelieved in—my possession of any dramatic power. Still, he began to think that I might as well try some time what I could do in fiction, and by and by, when we came back to England, and I had greater success than he ever expected in other kinds of writing, his impression that it was worth while to see how far my mental power would go towards the production of a novel, was strengthened. He began to say very positively, "You must try and write a story," and when we were at Tenby he urged me to begin at once. I deferred it, however, after my usual fashion with work that does not present itself as an absolute duty. But [299]one morning, as I was thinking what should be the subject of my first story, my thoughts merged themselves into a dreamy doze, and I imagined myself writing a story, of which the title was "The Sad Fortunes of the Reverend Amos Barton." I was soon wide awake again and told G. He said, "Oh, what a capital title!" and from that time I had settled in my mind that this should be my first story. George used to say, "It may be a failure—it may be that you are unable to write fiction. Or, perhaps, it may be just good enough to warrant your trying again." Again, "You may write a chef-d'œuvre at once—there's no telling." But his prevalent impression was, that though I could hardly write a poor novel, my effort would want the highest quality of fiction—dramatic presentation. He used to say, "You have wit, description, and philosophy—those go a good way towards the production of a novel. It is worth while for you to try the experiment."

We determined that if my story turned out good enough we would send it to Blackwood; but G. thought the more probable result was that I should have to lay it aside and try again.

But when we returned to Richmond I had to write my article on "Silly Novels," and my review of Contemporary Literature for the Westminster, so that I did not begin my story till September 22. After I had begun it, as we were walking in the park, I mentioned to G. that I had thought of the plan of writing a series of stories, containing sketches drawn from my own observation of the clergy, and calling them "Scenes from Clerical Life," opening with "Amos Barton." He at once accepted the notion as a good one—fresh and striking; and about a week afterwards, when I read [300]him the first part of "Amos," he had no longer any doubt about my ability to carry out the plan. The scene at Cross Farm, he said, satisfied him that I had the very element he had been doubtful about—it was clear I could write good dialogue. There still remained the question whether I could command any pathos; and that was to be decided by the mode in which I treated Milly's death. One night G. went to town on purpose to leave me a quiet evening for writing it. I wrote the chapter from the news brought by the shepherd to Mrs. Hackit, to the moment when Amos is dragged from the bedside, and I read it to G. when he came home. We both cried over it, and then he came up to me and kissed me, saying, "I think your pathos is better than your fun."

The story of the "Sad Fortunes of Amos Barton" was begun on 22d September and finished on the 5th November, and I subjoin the opening correspondence between Mr. Lewes and Mr. John Blackwood, to exhibit the first effect it produced:

Letter from G. H. Lewes, to John Blackwood, 6th Nov. 1856.

"I trouble you with a MS. of 'Sketches of Clerical Life' which was submitted to me by a friend who desired my good offices with you. It goes by this post. I confess that before reading the MS. I had considerable doubts of my friend's powers as a writer of fiction; but, after reading it, these doubts were changed into very high admiration. I don't know what you will think of the story, but, according to my judgment, such humor, pathos, vivid presentation, and nice observation have not been exhibited (in this style) since the 'Vicar of Wakefield;' and, in consequence of that opinion, I feel quite pleased in negotiating the matter with you.[301]

"This is what I am commissioned to say to you about the proposed series. It will consist of tales and sketches illustrative of the actual life of our country clergy about a quarter of a century ago—but solely in its human, and not at all in its theological aspects; the object being to do what has never yet been done in our literature, for we have had abundant religious stories, polemical and doctrinal, but since the 'Vicar' and Miss Austen, no stories representing the clergy like every other class, with the humors, sorrows, and troubles of other men. He begged me particularly to add, that—as the specimen sent will sufficiently prove—the tone throughout will be sympathetic, and not at all antagonistic.

"Some of these, if not all, you may think suitable for 'Maga.' If any are sent of which you do not approve, or which you do not think sufficiently interesting, these he will reserve for the separate republication, and for this purpose he wishes to retain the copyright. Should you only print one or two, he will be well satisfied; and still better, if you should think well enough of the series to undertake the separate republication."

***

On Christmas Day, 1856, "Mr. Gilfil's Love-Story" was begun, and during December and January the following are mentioned among the books read: The "Ajax" of Sophocles, Miss Martineau's "History of the Peace," Macaulay's "History" [306]finished, Carlyle's "French Revolution," Burke's "Reflections on the French Revolution," and "Mansfield Park."

***

Journal, 1858.

Feb. 28.—Mr. John Blackwood called on us, having come to London for a few days only. He talked a good deal about the "Clerical Scenes" and George Eliot, and at last asked, "Well, am I to see George Eliot this time?" G. said, "Do you wish to see him?" "As he likes—I wish it to be quite spontaneous." I left the room, and G. following me a moment, I told him he might reveal me. Blackwood was kind, came back when he found he was too late for the train, and [11]said he would come to Richmond again. He came on the following Friday and chatted very pleasantly—told us that Thackeray spoke highly of the "Scenes," and said they were not written by a woman. Mrs. Blackwood is sure they are not written by a woman. Mrs. Oliphant, the novelist, too, is confident on the same side. I gave Blackwood the MS. of my new novel, to the end of the second scene in the wood. He opened it, read the first page, and smiling, said, "This will do." We walked with him to Kew, and had a good deal of talk. Found, among other things, that he had lived two years in Italy when he was a youth, and that he admires Miss Austen.

Letter to Miss Sara Hennell, Wednesday, 2d June, 1852.

I am bothered to death with article-reading and scrap-work of all sorts: it is clear my poor head will never produce anything under these circumstances; but I am patient. I am ashamed to tease you so, but I must beg of you to send me George Sand's works; and also I shall be grateful if you will lend me—what I think you have—an English edition of "Corinne," and Miss Austen's "Sense and Sensibility." Harriet Martineau's article on "Niebuhr" will not go in the July number. I am sorry for it; it is admirable. After all, she is a trump—the only Englishwoman that possesses thoroughly the art of writing.

***

"September, 1856, made a new era in my life, for it was then I began to write fiction. It had always been a vague dream of mine that some time or other I might write a novel; and my shadowy conception of what the novel was to be, varied, of course, from one epoch of my life to another. But I never went further towards the actual writing of the novel than an introductory chapter describing a Staffordshire village and the life of the neighboring farm-houses; and as the years passed on I lost any hope that I should ever be able to write a novel, just as I desponded about everything else in my future life. I always thought I was deficient in dramatic power, both of construction and dialogue, but I felt I should be at my ease in the descriptive parts of a novel. My "introductory chapter" was pure description, though there were good materials in it for dramatic presentation. It happened to be among the papers I had with me in Germany, and one evening at Berlin something led me to read it to George. He was struck with it as a bit of concrete description, and it suggested to him the possibility of my being able to write a novel, though he distrusted—indeed, disbelieved in—my possession of any dramatic power. Still, he began to think that I might as well try some time what I could do in fiction, and by and by, when we came back to England, and I had greater success than he ever expected in other kinds of writing, his impression that it was worth while to see how far my mental power would go towards the production of a novel, was strengthened. He began to say very positively, "You must try and write a story," and when we were at Tenby he urged me to begin at once. I deferred it, however, after my usual fashion with work that does not present itself as an absolute duty. But [299]one morning, as I was thinking what should be the subject of my first story, my thoughts merged themselves into a dreamy doze, and I imagined myself writing a story, of which the title was "The Sad Fortunes of the Reverend Amos Barton." I was soon wide awake again and told G. He said, "Oh, what a capital title!" and from that time I had settled in my mind that this should be my first story. George used to say, "It may be a failure—it may be that you are unable to write fiction. Or, perhaps, it may be just good enough to warrant your trying again." Again, "You may write a chef-d'œuvre at once—there's no telling." But his prevalent impression was, that though I could hardly write a poor novel, my effort would want the highest quality of fiction—dramatic presentation. He used to say, "You have wit, description, and philosophy—those go a good way towards the production of a novel. It is worth while for you to try the experiment."

We determined that if my story turned out good enough we would send it to Blackwood; but G. thought the more probable result was that I should have to lay it aside and try again.

But when we returned to Richmond I had to write my article on "Silly Novels," and my review of Contemporary Literature for the Westminster, so that I did not begin my story till September 22. After I had begun it, as we were walking in the park, I mentioned to G. that I had thought of the plan of writing a series of stories, containing sketches drawn from my own observation of the clergy, and calling them "Scenes from Clerical Life," opening with "Amos Barton." He at once accepted the notion as a good one—fresh and striking; and about a week afterwards, when I read [300]him the first part of "Amos," he had no longer any doubt about my ability to carry out the plan. The scene at Cross Farm, he said, satisfied him that I had the very element he had been doubtful about—it was clear I could write good dialogue. There still remained the question whether I could command any pathos; and that was to be decided by the mode in which I treated Milly's death. One night G. went to town on purpose to leave me a quiet evening for writing it. I wrote the chapter from the news brought by the shepherd to Mrs. Hackit, to the moment when Amos is dragged from the bedside, and I read it to G. when he came home. We both cried over it, and then he came up to me and kissed me, saying, "I think your pathos is better than your fun."

The story of the "Sad Fortunes of Amos Barton" was begun on 22d September and finished on the 5th November, and I subjoin the opening correspondence between Mr. Lewes and Mr. John Blackwood, to exhibit the first effect it produced:

Letter from G. H. Lewes, to John Blackwood, 6th Nov. 1856.

"I trouble you with a MS. of 'Sketches of Clerical Life' which was submitted to me by a friend who desired my good offices with you. It goes by this post. I confess that before reading the MS. I had considerable doubts of my friend's powers as a writer of fiction; but, after reading it, these doubts were changed into very high admiration. I don't know what you will think of the story, but, according to my judgment, such humor, pathos, vivid presentation, and nice observation have not been exhibited (in this style) since the 'Vicar of Wakefield;' and, in consequence of that opinion, I feel quite pleased in negotiating the matter with you.[301]

"This is what I am commissioned to say to you about the proposed series. It will consist of tales and sketches illustrative of the actual life of our country clergy about a quarter of a century ago—but solely in its human, and not at all in its theological aspects; the object being to do what has never yet been done in our literature, for we have had abundant religious stories, polemical and doctrinal, but since the 'Vicar' and Miss Austen, no stories representing the clergy like every other class, with the humors, sorrows, and troubles of other men. He begged me particularly to add, that—as the specimen sent will sufficiently prove—the tone throughout will be sympathetic, and not at all antagonistic.

"Some of these, if not all, you may think suitable for 'Maga.' If any are sent of which you do not approve, or which you do not think sufficiently interesting, these he will reserve for the separate republication, and for this purpose he wishes to retain the copyright. Should you only print one or two, he will be well satisfied; and still better, if you should think well enough of the series to undertake the separate republication."

***

On Christmas Day, 1856, "Mr. Gilfil's Love-Story" was begun, and during December and January the following are mentioned among the books read: The "Ajax" of Sophocles, Miss Martineau's "History of the Peace," Macaulay's "History" [306]finished, Carlyle's "French Revolution," Burke's "Reflections on the French Revolution," and "Mansfield Park."

***

Journal, 1858.

Feb. 28.—Mr. John Blackwood called on us, having come to London for a few days only. He talked a good deal about the "Clerical Scenes" and George Eliot, and at last asked, "Well, am I to see George Eliot this time?" G. said, "Do you wish to see him?" "As he likes—I wish it to be quite spontaneous." I left the room, and G. following me a moment, I told him he might reveal me. Blackwood was kind, came back when he found he was too late for the train, and [11]said he would come to Richmond again. He came on the following Friday and chatted very pleasantly—told us that Thackeray spoke highly of the "Scenes," and said they were not written by a woman. Mrs. Blackwood is sure they are not written by a woman. Mrs. Oliphant, the novelist, too, is confident on the same side. I gave Blackwood the MS. of my new novel, to the end of the second scene in the wood. He opened it, read the first page, and smiling, said, "This will do." We walked with him to Kew, and had a good deal of talk. Found, among other things, that he had lived two years in Italy when he was a youth, and that he admires Miss Austen.

George Saintsbury

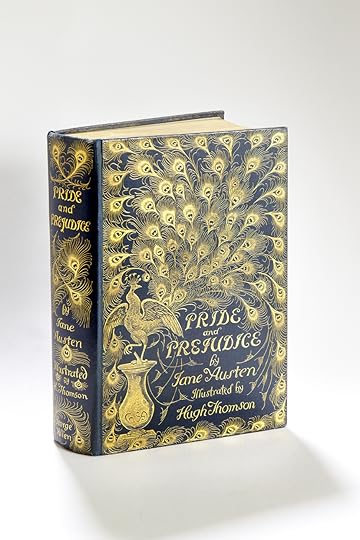

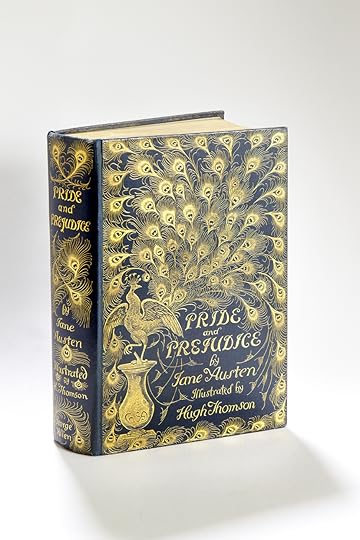

Preface to Pride and Prejudice by George Saintsbury (1894) - it's the famous Peacock edition with Hugh Thompson's illustrations

https://www.jausten.it/jaindsaintsbur...

George Edward Bateman Saintsbury, FBA (23 October 1845 – 28 January 1933), an English critic, literary historian, editor, teacher, and wine connoisseur, gained a reputation as a highly influential literary critic of the late-19th and early-20th centuries.

The English Novel by George Saintsbury

https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/14469

A History of Nineteenth Century Literature (1780-1895) by George Saintsbury

https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/31698

Preface to Pride and Prejudice by George Saintsbury (1894) - it's the famous Peacock edition with Hugh Thompson's illustrations

https://www.jausten.it/jaindsaintsbur...

George Edward Bateman Saintsbury, FBA (23 October 1845 – 28 January 1933), an English critic, literary historian, editor, teacher, and wine connoisseur, gained a reputation as a highly influential literary critic of the late-19th and early-20th centuries.

The English Novel by George Saintsbury

https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/14469

A History of Nineteenth Century Literature (1780-1895) by George Saintsbury

https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/31698

Essay "Miss Burney's Own Story" by Mary Elizabeth Christie

in The contemporary review, v. 43, 1883 Jan-Jun, p. 332

"Maria Edgeworth, who had sighed hopelessly in 1783 for the "honour of Miss Burncy's corre- spondence," published "Castle Rackrent" and "Belinda" in 1801; in 1811, Jane Austen brought out "Sense and Sensibility." Each in her different way, and very different degree, was a greater artist than Miss Burney. Miss Edgeworth excelled in grasp of moral principles; Miss Austen was supreme in literary form. But when the next place to Shakespeare is claimed for Jane Austen as a painter of human nature, I cannot help asking whether in one quality Frances Burney does not come nearer to deserving this high honour. She painted human nature with a more genial touch than Jane Austen. She certainly wants the quiet and terrible power with which her successor lays bare and withers the follies and the meannesses of mankind. But on the other hand she does what Miss Austen fails to do-she warms our hearts towards our fellow-creatures in their folly even more than in their wisdom. Her fools and they are many- are as ridiculous and tiresome persons as it is possible to conceive, and yet the result of jogging along with them through her voluminous novels is that, as we turn the last page, we realize that, after all, we have a kindly feeling and a sense of kin towards each and all of them. She had a pure artistic delight in character, which enabled her to enjoy, and make others enjoy, every genuine manifestation of it.

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?i...

Miss Burney's Novels, Contemporary Review, December 1882

in The contemporary review, v. 43, 1883 Jan-Jun, p. 332

"Maria Edgeworth, who had sighed hopelessly in 1783 for the "honour of Miss Burncy's corre- spondence," published "Castle Rackrent" and "Belinda" in 1801; in 1811, Jane Austen brought out "Sense and Sensibility." Each in her different way, and very different degree, was a greater artist than Miss Burney. Miss Edgeworth excelled in grasp of moral principles; Miss Austen was supreme in literary form. But when the next place to Shakespeare is claimed for Jane Austen as a painter of human nature, I cannot help asking whether in one quality Frances Burney does not come nearer to deserving this high honour. She painted human nature with a more genial touch than Jane Austen. She certainly wants the quiet and terrible power with which her successor lays bare and withers the follies and the meannesses of mankind. But on the other hand she does what Miss Austen fails to do-she warms our hearts towards our fellow-creatures in their folly even more than in their wisdom. Her fools and they are many- are as ridiculous and tiresome persons as it is possible to conceive, and yet the result of jogging along with them through her voluminous novels is that, as we turn the last page, we realize that, after all, we have a kindly feeling and a sense of kin towards each and all of them. She had a pure artistic delight in character, which enabled her to enjoy, and make others enjoy, every genuine manifestation of it.

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?i...

Miss Burney's Novels, Contemporary Review, December 1882

Jane Austen, by Mrs. Charles Malden (=Sarah Fanny Malden)

Published in 1889

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?i...

Published in 1889

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?i...

The development of the English novel, by Wilbur L. Cross (1899)

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?i...

Wilbur Lucius Cross (April 10, 1862 – October 5, 1948) was an American literary critic who served as the 71st governor of Connecticut from 1931 to 1939.

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?i...

Wilbur Lucius Cross (April 10, 1862 – October 5, 1948) was an American literary critic who served as the 71st governor of Connecticut from 1931 to 1939.

The literary history of England in the end of the eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth century, by Mrs. Oliphant v.3

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?i...

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?i...

Harriet Martineau (12 June 1802 – 27 June 1876) was an English social theorist.[2] She wrote from a sociological, holistic, religious and feminine angle, translated works by Auguste Comte, and, rare for a woman writer at the time, earned enough to support herself.[3]

Martineau advised a focus on all aspects of society, including the role of the home in domestic life as well as key political, religious, and social institutions. The young Princess Victoria enjoyed her work and invited her to her coronation in 1838.[4][5] The novelist Margaret Oliphant called her "a born lecturer and politician... less distinctively affected by her sex than perhaps any other, male or female, of her generation."[3]

Her commitment to abolitionism has seen Martineau's achievements studied world-wide, particularly at American institutions of higher education.[6][7][8] When unveiling a statue of Martineau in December 1883 at the Old South Meeting House in Boston, Wendell Phillips referred to her as the "greatest American abolitionist".

Autobiography (1855):

"When I was young, it was not thought proper for young ladies to study very conspicuously ; and especially with pen in hand. Young ladies (at least in provincial towns) were expected to sit down in the parlour to sew, — during which reading aloud was permitted, — or to practice their music ; but so as to be fit to receive callers, without any signs of blue-stockingism which could be reported abroad. Jane Austen herself, the Queen of novelists, the immortal creator of Anne Elliott, Mr. Knightley, and a score or two more of unrivalled intimate friends of the whole public, was compelled by the feelings of her family to cover up her manuscripts with a large piece of muslin work, kept on the table for the purpose, whenever any genteel people came in. So it was with other young ladies, for some time after Jane Austen was in her grave ; and thus my first studies in philosophy were carried on with great care and reserve."

...

"Their friend Miss Mitford came up to town occasionally, and found her way to Fludyer Street. I was early fond of her tales and descriptions, and have always regarded her as the originator of that new style of " graphic description " to which literature owes a great deal, however weary we, may sometimes have felt of the excess into which the practice of detail has run. In my childhood, there was no such thing known, in the works of the day, as " graphic description : " and most people delighted as much as I did in Mrs. Eatcliffe's gorgeous or luscious generalities,— just as we admired in picture galleries landscapes all misty and glowing indefinitely with bright colours, — yellow sunrises and purple and crimson sunsets, — because we had no conception of detail like Miss Austen's in manners, and Miss Mitford's in scenery, or of Millais' and Wilkie's analogous life pictures, or Rosa Bonheur's adventurous Hayfield at noon-tide. Miss Austen had claims to other and greater honours ; but she and Miss Mitford deserve no small gratitude for rescuing us from the folly and bad taste of slovenly indefiniteness in delineation."

"...she [Miss Berry] believing the appearance of heartlessness in him [Mr Horace? Walpole] to be ascribable to the influence of his timev She did not succeed in changing the world's judgment of her friend ; and this was partly because the influences of the time did not prevent other men from showing heart. Charles James Fox had a heart ; and so had Burke and a good many more. While Johnson and then Darwin were corrupting men's taste in diction, Cowper was keeping it pure enough to enjoy the three rising poets, alike only in their plainness of speech — Crabbe, Bums, and Wordsworth. Before Miss Burney had exhausted our patience, the practical Maria Edgeworth was growing up. While Godwin would have engaged us wholly with the interior scenery of man's nature, Scott was fitting up his theatre for his mighty procession of costumes, with men in them to set them moving ; and Jane Austen, whose name and works will outlive many that were supposed immortal, was stealthily putting forth her unmatched delineations of domestic life in the middle classes of our aristocratic England. And against the somewhat feeble elegance of Sir William Jones's learning there was the safeguard of Gibbon's marvellous combination of strength and richness in his erudition. The vigor of Campbell's lyrics was a set-off against the prettiness of Moore's. The subtlety of Coleridge meets its match, and a good deal more, in the development of science ; and the morose complainings of Byron are less and less echoed now that the peace has opened the world to gentry whose energies would be self-corroding if they were under blockade at home, through an universal continental war. Byron is read at sea now, on the way to the North Pole, or to California, or to Borneo ; and in that way his woes can do no harm. To every thing there is a season; and to every fashion of a season there is an antagonism preparing. Thus all things have their turn ; all human faculties have their stimulus, sooner or later, supposing them to be put in the way of the influences of social life."

from Autobiography, with memorials by Maria Weston Chapman

by Martineau, Harriet, 1802-1876; Chapman, Maria Weston, 1806-1885

"Read "Emma," — most admirable. The little comj)lexities of the story are beyond my comprehension, and wonderfully beautiful" Jan 18th, 1838

From Harriet Martineau by Florence Fenwick Miller (1884)

About Deerbrook (1839)

"This bondage to (supposed) fact was one cause of her failure. A lesser, but still important reason for it, was that she tried to imitate Jane Austen's style. X Her admiration of the works of this mistress of the art of depicting human nature was very great. Harnet's diary of tlie period when she was preparing to write Deerbrooky shows that she re-read Miss Austen's novels, and found them "wonderfully beautiful". This judgment she annexed to Emma and again, after recording her new reading of Pride and Prejudice, she added, "I think it as clever as before ; but Miss Austen seems wonderfully afraid of pathos. I long to try" When she did " try" she, either intentionally or unconsciously, but very decidedly, modelled her style on Miss Austen's. But the two women were essentially different. Harriet Martineau had an original mind; she did wrong, and prepared the retribution of failure for herself, in imitating at all; and Jane Austen was one of the last persons she should have imitated."

"Miss and her naval partner remind me of the pair in the novel that I have read eleven times — Miss Austen's Persuasion — unequalled in interest, charm and truth (to my mind). There is a hint there of the drawback of separation ; but yet, — who would have desired anything for Anne Elliot and her Captain Wentworth but that they should marry?"

From a letter - Sept 7th, 1873

[Florence Fenwick Miller (sometimes Fenwick-Miller, 5 November 1854 – 24 April 1935) was an English journalist, author and social reformer of the late 19th and early 20th century. She was for four years the editor and proprietor of The Woman's Signal, an early and influential feminist journal.]

Martineau advised a focus on all aspects of society, including the role of the home in domestic life as well as key political, religious, and social institutions. The young Princess Victoria enjoyed her work and invited her to her coronation in 1838.[4][5] The novelist Margaret Oliphant called her "a born lecturer and politician... less distinctively affected by her sex than perhaps any other, male or female, of her generation."[3]

Her commitment to abolitionism has seen Martineau's achievements studied world-wide, particularly at American institutions of higher education.[6][7][8] When unveiling a statue of Martineau in December 1883 at the Old South Meeting House in Boston, Wendell Phillips referred to her as the "greatest American abolitionist".

Autobiography (1855):

"When I was young, it was not thought proper for young ladies to study very conspicuously ; and especially with pen in hand. Young ladies (at least in provincial towns) were expected to sit down in the parlour to sew, — during which reading aloud was permitted, — or to practice their music ; but so as to be fit to receive callers, without any signs of blue-stockingism which could be reported abroad. Jane Austen herself, the Queen of novelists, the immortal creator of Anne Elliott, Mr. Knightley, and a score or two more of unrivalled intimate friends of the whole public, was compelled by the feelings of her family to cover up her manuscripts with a large piece of muslin work, kept on the table for the purpose, whenever any genteel people came in. So it was with other young ladies, for some time after Jane Austen was in her grave ; and thus my first studies in philosophy were carried on with great care and reserve."

...

"Their friend Miss Mitford came up to town occasionally, and found her way to Fludyer Street. I was early fond of her tales and descriptions, and have always regarded her as the originator of that new style of " graphic description " to which literature owes a great deal, however weary we, may sometimes have felt of the excess into which the practice of detail has run. In my childhood, there was no such thing known, in the works of the day, as " graphic description : " and most people delighted as much as I did in Mrs. Eatcliffe's gorgeous or luscious generalities,— just as we admired in picture galleries landscapes all misty and glowing indefinitely with bright colours, — yellow sunrises and purple and crimson sunsets, — because we had no conception of detail like Miss Austen's in manners, and Miss Mitford's in scenery, or of Millais' and Wilkie's analogous life pictures, or Rosa Bonheur's adventurous Hayfield at noon-tide. Miss Austen had claims to other and greater honours ; but she and Miss Mitford deserve no small gratitude for rescuing us from the folly and bad taste of slovenly indefiniteness in delineation."

"...she [Miss Berry] believing the appearance of heartlessness in him [Mr Horace? Walpole] to be ascribable to the influence of his timev She did not succeed in changing the world's judgment of her friend ; and this was partly because the influences of the time did not prevent other men from showing heart. Charles James Fox had a heart ; and so had Burke and a good many more. While Johnson and then Darwin were corrupting men's taste in diction, Cowper was keeping it pure enough to enjoy the three rising poets, alike only in their plainness of speech — Crabbe, Bums, and Wordsworth. Before Miss Burney had exhausted our patience, the practical Maria Edgeworth was growing up. While Godwin would have engaged us wholly with the interior scenery of man's nature, Scott was fitting up his theatre for his mighty procession of costumes, with men in them to set them moving ; and Jane Austen, whose name and works will outlive many that were supposed immortal, was stealthily putting forth her unmatched delineations of domestic life in the middle classes of our aristocratic England. And against the somewhat feeble elegance of Sir William Jones's learning there was the safeguard of Gibbon's marvellous combination of strength and richness in his erudition. The vigor of Campbell's lyrics was a set-off against the prettiness of Moore's. The subtlety of Coleridge meets its match, and a good deal more, in the development of science ; and the morose complainings of Byron are less and less echoed now that the peace has opened the world to gentry whose energies would be self-corroding if they were under blockade at home, through an universal continental war. Byron is read at sea now, on the way to the North Pole, or to California, or to Borneo ; and in that way his woes can do no harm. To every thing there is a season; and to every fashion of a season there is an antagonism preparing. Thus all things have their turn ; all human faculties have their stimulus, sooner or later, supposing them to be put in the way of the influences of social life."

from Autobiography, with memorials by Maria Weston Chapman

by Martineau, Harriet, 1802-1876; Chapman, Maria Weston, 1806-1885

"Read "Emma," — most admirable. The little comj)lexities of the story are beyond my comprehension, and wonderfully beautiful" Jan 18th, 1838

From Harriet Martineau by Florence Fenwick Miller (1884)

About Deerbrook (1839)

"This bondage to (supposed) fact was one cause of her failure. A lesser, but still important reason for it, was that she tried to imitate Jane Austen's style. X Her admiration of the works of this mistress of the art of depicting human nature was very great. Harnet's diary of tlie period when she was preparing to write Deerbrooky shows that she re-read Miss Austen's novels, and found them "wonderfully beautiful". This judgment she annexed to Emma and again, after recording her new reading of Pride and Prejudice, she added, "I think it as clever as before ; but Miss Austen seems wonderfully afraid of pathos. I long to try" When she did " try" she, either intentionally or unconsciously, but very decidedly, modelled her style on Miss Austen's. But the two women were essentially different. Harriet Martineau had an original mind; she did wrong, and prepared the retribution of failure for herself, in imitating at all; and Jane Austen was one of the last persons she should have imitated."

"Miss and her naval partner remind me of the pair in the novel that I have read eleven times — Miss Austen's Persuasion — unequalled in interest, charm and truth (to my mind). There is a hint there of the drawback of separation ; but yet, — who would have desired anything for Anne Elliot and her Captain Wentworth but that they should marry?"

From a letter - Sept 7th, 1873

[Florence Fenwick Miller (sometimes Fenwick-Miller, 5 November 1854 – 24 April 1935) was an English journalist, author and social reformer of the late 19th and early 20th century. She was for four years the editor and proprietor of The Woman's Signal, an early and influential feminist journal.]

Letters of Mary Russell Mitford by Mary Russell Mitford (1872)

from letters to Mrs Hoffland (?)

"At present my haycock companion is an old novel called " The Beggar Girl." Did you ever read it? It is nothing grand to talk about; and indeed people seem to think it so ignominious, that I never met with anybody in my life but Miss J- who confessed to have read it ; but to me the novel is one of the very best I ever met with. The prodigious quantity of invention, the identity of the characters, particularly a certain Mrs. Feversham and Betty Brown, and above all, the total absence of moral maxims of the do-me-good air which one expects to find in Miss Edgeworth, give a freshness and truth to " The Beggar Girl " which I never found in any fiction except that of Miss Austen. " Vicissitudes," and "Ellen," are almost equally good. You, my dear Mrs. Hofland, are one of those who can afford to praise a thing not commonly praised, and I think you would like them. I long for your tale. You are the mistress of our tears, as Miss Austen is of our smiles, and I think you have the advantage. People are prouder of crying than of laughing ; you hear more praises of Lear than of the "School for Scandal"."

from a letter - April 17, 1819

"I am finishing a tragedy on the subject of Charles and Cromwell, for Covent Garden next year, and then. I shall go dingdong to a novel, of which I have already laid the plan. It will be common English life in the country, as playful, and as true, as I can make it, in other words, as like Miss Austen ; but I am unfeignedly afraid of the attempt. It must be made though; and when I recollect the kind encouragement which I have so often received from you and Mr. Hofland, and the universal demand made on me for sut^h a work, I feel emboldened."

from letter May 25,1825

"I was standing wearily before the drawing-room fire, indulging the ennui engendered by Mr. H 's silence and conversation, Mrs. D brought Miss B up to me, and asked in her quick manner, "How do you like Mr. H 's face ? What does it express?" "Nothing!" said I, in my quiet and truth-telling way, little dreaming that I was giving this flattering answer before his lady-love ; and how Mrs. D brought him to it I cannot imagine — for I avow to you he never uttered a syllable to her that, whole day. Now must I apologise to Miss B for having disliked him so much as my beloved Mrs. Bennet did to her daughter Lizzy, in my ever dear "Pride and Prejudice." After all, it's a verygood match — he is a worthy young man, she a kind, well-meaning girl, as much too man-like as he is too womanly — so there is a good chance of their improving each other."

from a letter - Feb 7, 1821

Now I have always had many, and therefore I love things that make me gay — therefore, amongst other reasons, I love Miss Austen.

from a letter to Miss Barret, Dec 5, 1842

"Your admiration of Jane Austen is so far from being a heresy, that I never met any high literary people in my life who did not prefer her to any female prose writer. The only dissent I ever heard was from one very clever man, who stood up for the "Simple Story" as still finer; but then that was only one novel, and only the first half of that. For my own part, I delight in her. and really cannot read the present race of novel-writers —although my old friend Mrs. Trollope, in spite of her terrible coarseness, has certainly done two or three marvellously clever things. She was brought up within three miles of this house, being the daughter of a former vicar of Heckfield, and is, in spite of her works, a most elegant and agreeable woman. I have known her these fifty years; she must be turned of seventy, and is wonderful for energy of mind and body. Her story is very curious; put me in mind to tell it you. She used to be such a Radical that her house in London was a perfect emporium of escaped state criminals. I remember asking her at one of her parties how many of her guests would have been shot or guillotined if they had remained in their own country."

from a letter to Mrs Hoare, 1852

from letters to Mrs Hoffland (?)

"At present my haycock companion is an old novel called " The Beggar Girl." Did you ever read it? It is nothing grand to talk about; and indeed people seem to think it so ignominious, that I never met with anybody in my life but Miss J- who confessed to have read it ; but to me the novel is one of the very best I ever met with. The prodigious quantity of invention, the identity of the characters, particularly a certain Mrs. Feversham and Betty Brown, and above all, the total absence of moral maxims of the do-me-good air which one expects to find in Miss Edgeworth, give a freshness and truth to " The Beggar Girl " which I never found in any fiction except that of Miss Austen. " Vicissitudes," and "Ellen," are almost equally good. You, my dear Mrs. Hofland, are one of those who can afford to praise a thing not commonly praised, and I think you would like them. I long for your tale. You are the mistress of our tears, as Miss Austen is of our smiles, and I think you have the advantage. People are prouder of crying than of laughing ; you hear more praises of Lear than of the "School for Scandal"."

from a letter - April 17, 1819

"I am finishing a tragedy on the subject of Charles and Cromwell, for Covent Garden next year, and then. I shall go dingdong to a novel, of which I have already laid the plan. It will be common English life in the country, as playful, and as true, as I can make it, in other words, as like Miss Austen ; but I am unfeignedly afraid of the attempt. It must be made though; and when I recollect the kind encouragement which I have so often received from you and Mr. Hofland, and the universal demand made on me for sut^h a work, I feel emboldened."

from letter May 25,1825

"I was standing wearily before the drawing-room fire, indulging the ennui engendered by Mr. H 's silence and conversation, Mrs. D brought Miss B up to me, and asked in her quick manner, "How do you like Mr. H 's face ? What does it express?" "Nothing!" said I, in my quiet and truth-telling way, little dreaming that I was giving this flattering answer before his lady-love ; and how Mrs. D brought him to it I cannot imagine — for I avow to you he never uttered a syllable to her that, whole day. Now must I apologise to Miss B for having disliked him so much as my beloved Mrs. Bennet did to her daughter Lizzy, in my ever dear "Pride and Prejudice." After all, it's a verygood match — he is a worthy young man, she a kind, well-meaning girl, as much too man-like as he is too womanly — so there is a good chance of their improving each other."

from a letter - Feb 7, 1821

Now I have always had many, and therefore I love things that make me gay — therefore, amongst other reasons, I love Miss Austen.

from a letter to Miss Barret, Dec 5, 1842

"Your admiration of Jane Austen is so far from being a heresy, that I never met any high literary people in my life who did not prefer her to any female prose writer. The only dissent I ever heard was from one very clever man, who stood up for the "Simple Story" as still finer; but then that was only one novel, and only the first half of that. For my own part, I delight in her. and really cannot read the present race of novel-writers —although my old friend Mrs. Trollope, in spite of her terrible coarseness, has certainly done two or three marvellously clever things. She was brought up within three miles of this house, being the daughter of a former vicar of Heckfield, and is, in spite of her works, a most elegant and agreeable woman. I have known her these fifty years; she must be turned of seventy, and is wonderful for energy of mind and body. Her story is very curious; put me in mind to tell it you. She used to be such a Radical that her house in London was a perfect emporium of escaped state criminals. I remember asking her at one of her parties how many of her guests would have been shot or guillotined if they had remained in their own country."

from a letter to Mrs Hoare, 1852

Margaret Oliphant

"The literary history of England in the end of the eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth century". In volume 3, in the chapter "Maria Edgeworth - Jane Austen - Susan Ferrier", she praises all these women, but especially Austen.

"The life of average human nature swept by no violence of passions, disturbed by no volcanic events, came suddenly uppermost in the works of these women as it had never done before. Miss Austen in particular, the greates and most enduring of the three, found enough in the quiet tenor of life which fell under her own eyes to interest the world."

She wrote the article "Miss Austen and Miss Mitford" (see above).

"The literary history of England in the end of the eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth century". In volume 3, in the chapter "Maria Edgeworth - Jane Austen - Susan Ferrier", she praises all these women, but especially Austen.

"The life of average human nature swept by no violence of passions, disturbed by no volcanic events, came suddenly uppermost in the works of these women as it had never done before. Miss Austen in particular, the greates and most enduring of the three, found enough in the quiet tenor of life which fell under her own eyes to interest the world."

She wrote the article "Miss Austen and Miss Mitford" (see above).

Books mentioned in this topic

English Women of Letters (other topics)Jane Austen's Lovers: And Other Studies in Fiction and History from Austen to le Carré (other topics)

The Letters of Anthony Trollope (other topics)

George Eliot’s Life, as Related in her Letters and Journals (other topics)

The Life of Jane Austen (other topics)

More...

Authors mentioned in this topic

Henry James (other topics)Julia Kavanagh (other topics)

Leslie Stephen (other topics)

Goldwin Smith 1823-1910 (other topics)

Charlotte Brontë (other topics)

More...