Art Lovers discussion

Art Lovers News Corner

>

February 2010

message 1:

by

Heather

(new)

Jan 31, 2010 04:54PM

To facilitate browsing and posting the current news in the art world, we have decided to create a News Corner for every month. Feel free to add, comment and participate in the news! If you hear of something or read something interesting, share it with the group, we'd love to hear it too!

To facilitate browsing and posting the current news in the art world, we have decided to create a News Corner for every month. Feel free to add, comment and participate in the news! If you hear of something or read something interesting, share it with the group, we'd love to hear it too!

reply

|

flag

PICASSO STICKS UP FOR HIS SISTERS

PICASSO STICKS UP FOR HIS SISTERSAt Tate Britain's Chris Ofili launch party last week, Christoph Grunenberg, director of Tate Liverpool, was keen to reveal important art historical details about his forthcoming blockbusting Picasso show (21 May-30 August) at the Merseyside museum. Cheekily goaded by Stephen Snoddy, director of the New Art Gallery Walsall, Grunenberg announced (drum roll) that “Picasso was secretly a feminist.” And has he had any problems obtaining loans for the show? “We were desperate but now we’ve got over 200 works,” he said. Phew.

A Controversy Over Degas

A Controversy Over Degas

Experts are concerned about the authenticity of 74 "recently discovered" plaster casts of Degas sculptures that were purportedly made during his lifetime and the bronzes that have been produced from them, which are now selling for more than $2 million

by William D. Cohan

http://www.artnews.com/issues/article...

This year marks the fourth centenary of the death of Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio. (1573-1610)

This year marks the fourth centenary of the death of Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio. (1573-1610)[image error]

His intensely emotional realism and dramatic use of lighting had a formative influence on the Baroque school of painting. Famous (and notorious) while he lived, Caravaggio was forgotten almost immediately after his death, and it was only in the 20th century that his importance to the development of Western art was rediscovered.

Hello Heather! In my opninion,Caravaggio is the best realism artist i'd ever seen. Because you can see the pure and true soul of each character he paint. In other words, you can feel the painted charachter like it's you, without getting any influence from Caravaggio himself.

Hello Heather! In my opninion,Caravaggio is the best realism artist i'd ever seen. Because you can see the pure and true soul of each character he paint. In other words, you can feel the painted charachter like it's you, without getting any influence from Caravaggio himself.

Hi, Heather! Caravaggio's most famous contribution was the dramatic use of light and shadow called chiaroscuro. I went to a great classical art school in New York City. If you're an artist, check out my most recent blog entry, "secrets of the old masters," at helenmarylesshankman.wordpress.com to find out how to best use light and dark for their greatest effects.

Hi, Heather! Caravaggio's most famous contribution was the dramatic use of light and shadow called chiaroscuro. I went to a great classical art school in New York City. If you're an artist, check out my most recent blog entry, "secrets of the old masters," at helenmarylesshankman.wordpress.com to find out how to best use light and dark for their greatest effects. You're right! I learned a little bit about chiaroscuro in college, but not the valuable information you posted in your blog. Since it wasn't an art class, it didn't teach how to use the light and shadow. Looking at Caravaggio's paintings, the chiaroscuro is really what makes the painting! He was definitely a master!

You're right! I learned a little bit about chiaroscuro in college, but not the valuable information you posted in your blog. Since it wasn't an art class, it didn't teach how to use the light and shadow. Looking at Caravaggio's paintings, the chiaroscuro is really what makes the painting! He was definitely a master!

I enjoy the emotive quality of his paintings. They are extremely expressive. There is no passive way to experience them as the chiaroscuro adds immensely to the effect.

I enjoy the emotive quality of his paintings. They are extremely expressive. There is no passive way to experience them as the chiaroscuro adds immensely to the effect.

GIACOMETTI SCULPTURE FETCHES RECORD $104M

GIACOMETTI SCULPTURE FETCHES RECORD $104MPrice for ‘Walking Man I’ is highest ever paid for work of art at auction

LONDON - A life-size bronze sculpture of a man by Alberto Giacometti was sold Wednesday at a London auction for 65 million pounds ($104.3 million) — a world record for the most expensive work of art ever sold at auction, Sotheby’s auction house said.

It took just eight minutes of furious bidding for about ten bidders to reach the hammer price for “L’Homme Qui Marche I” (Walking Man I), which opened at 12 million pounds, Sotheby’s said.

The sculpture by the 20th century Swiss artist, considered an iconic Giacometti work as well as one of the most recognizable images of modern art, was sold to an anonymous bidder by telephone, the auction house said.

Sotheby’s had estimated the work would sell for between 12 to 18 million pounds.

The sale price trumped the $104.17 million paid at a 2004 New York auction for Pablo Picasso’s 1905 “Boy With a Pipe (The Young Apprentice).” That painting broke the record that Vincent van Gogh had held since 1990, and its sale was the first time that the $100 million barrier was broken.

“It’s a phenomenal result ... I think the result pretty much reflects the depth of the market,” Helena Newman, a specialist of Impressionist and Modern art at Sotheby’s, told the BBC.

The price for the sculpture went up rapidly with keen interest from bidders calling in from Europe, Asia and the U.S., Newman said.

“L’Homme Qui Marche I,” a life-size sculpture of a thin and wiry human figure standing 72 inches (183 centimeters) tall , “represents the pinnacle of Giacometti’s experimentation with the human form” and is “both a humble image of an ordinary man, and a potent symbol of humanity,” Sotheby’s said.

The work was cast in 1961, in the artist’s mature period. It is rare because it was the only cast of the walking man made during Giacometti’s lifetime that has ever come to auction, Sotheby’s said. It was bought by Dresdner Bank in the early 1980s.

The last time a Giacometti of comparable size was offered at auction was 20 years ago. That sculpture was sold for $6.82 million, a record for Giacometti works at the time.

The Associated Press.

WHY VAN GOGH CUT HIS EAR: NEW CLUE

WHY VAN GOGH CUT HIS EAR: NEW CLUEStill-life painting depicts letter with news of his brother's engagement

[image error]

An envelope depicted in a Van Gogh painting provides a clue that could help to explain why the artist slashed his ear. The envelope, in Still Life: Drawing Board with Onions, 1889, is addressed to Vincent from his brother Theo. Until now, no one has considered whether the artist was illustrating a specific letter.

The letter in the painting probably arrived in Arles on 23 December 1888, the fateful day when Vincent mutilated his ear in the late evening. It almost certainly contained news that Theo had fallen in love with Johanna (Jo) Bonger, and Vincent was fearful that he might lose his brother’s emotional and financial support.

In the still-life, the handwriting on the envelope is clearly Theo’s, and the letter is addressed to Vincent in Arles. Although the postmarks lack a legible date, one contains the number “67”, enclosed in a circle. This was used by the post office in Place des Abbesses, close to Theo’s Montmartre apartment.

The postmark directly over the two postage stamps reads “Jour de l’An” (New Year’s Day). This was spotted by Dutch specialists working on the new edition of Van Gogh’s letters, which was published in October. They concluded that the letter had been posted during “the busy period around New Year” and it had possibly arrived on 23 December, the date Vincent received his 100 francs financial allowance from Theo by post. The letter was probably posted the day before from Paris.

The established view is that Vincent did not learn of Theo’s engagement until after he mutilated his ear, but our research suggests that news of the love affair reached him on 23 December. Theo and Jo had met (for a second time, after a long break) in Paris in mid-December and decided to marry just a few days later. On 21 December Theo wrote to his mother, asking for permission. His brother must surely have been among the next to know.

It seems Vincent already knew of the impending engagement when Theo visited him in hospital on Christmas Day. In a recently published letter, Theo wrote to his fiancée about the brief hospital visit: “When I mentioned you to him he evidently knew who and what I meant and when I asked whether he approved of our plans, he said yes, but that marriage ought not to be regarded as the main object in life.”

On Christmas Day Vincent was suffering from a life-threatening wound and was in considerable mental distress, so it seems unlikely that Theo would have broken the news about his engagement. Although it was briefly discussed, this was presumably because Vincent had already known.

Still Life: Drawing Board with Onions was painted just a few days after Vincent returned to the Yellow House on 7 January 1889. News of the love affair could well have been a trigger for the self-mutilation, although there was probably no one simple explanation for the incident and there were also serious tensions with Gauguin. Vincent may have feared (wrongly) that he would lose the support of Theo. For years, Theo had provided money and friendship.

Vincent’s feelings must have been complex, and by January 1889 he may well have become reconciled to the engagement, following reassurances from his brother. The very fact that he included the envelope in the still-life suggests a message of hope.

Although it is speculation, the postmark on the envelope might represent a coded message that the strong links between the two brothers would survive. The Musée de La Poste in Paris told us that although “Jour de l’An” postmarks were widely used in the run-up to Christmas and New Year in the 1880s, most are fairly small marks, rather than the more prominent words inscribed by Van Gogh. This suggests that the personalised postmark may have been Vincent’s way of stressing to Theo that the letter depicted was a very particular one—and that he wished his brother well for the new year.

The painting, on loan from the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo, will form the centrepiece of “The Real Van Gogh: the Artist and his Letters”, opening at London’s Royal Academy on 23 January.

By Martin Bailey

Everytime I look @ one of VG's paintings, I feel he's sending a message through his painting...but to whom and what is the message? I can't tell.

Everytime I look @ one of VG's paintings, I feel he's sending a message through his painting...but to whom and what is the message? I can't tell.interesting post!

Thanks you Heather :)

You're welcome, Amal. I though this was interesting because there are so many speculations as to who and why he lost part of his ear. I remember Alex posted a different speculation, I think I will post that again here so we can kind of make our own decision-if possible :)

You're welcome, Amal. I though this was interesting because there are so many speculations as to who and why he lost part of his ear. I remember Alex posted a different speculation, I think I will post that again here so we can kind of make our own decision-if possible :)

THE REAL STORY BEHIND VAN GOGHS SEVERED EAR

Historians Now Claim That van Gogh Lost His Ear in a Fight With Fellow Artist Paul Gauguin

By CHRISTEL KUCHARZ

PASSAU, Germany, May 5, 2009

He's known as the tortured genius who cut off his own ear, but two German historians now claim that painter Vincent van Gogh lost his ear in a fight with his friend, the French artist Paul Gauguin.

The official version about van Gogh's legendary act of self-harm usually goes that the disturbed Dutch painter severed his left ear lobe with a razor blade in a fit of lunacy after he had a row with Gauguin one evening shortly before Christmas 1888.

Bleeding heavily, van Gogh then wrapped it in cloth, walked to a nearby bordello and presented the severed ear to a prostitute, who fainted when he handed it to her.

He then went home to sleep in a blood-drenched bed, where he almost bled to death, before police, alerted by the prostitute, found him the next morning.

He was unconscious and immediately taken to the local hospital, where he asked to see his friend Gauguin when he woke up, but Gauguin refused to see him.

A new book, published in Germany by Hamburg-based historians Hans Kaufmann and Rita Wildegans, argues that Vincent van Gogh may have made up the whole story to protect his friend Gauguin, a keen fencer, who actually lopped it off with a sword during a heated argument.

The historians say that the real version of events has never surfaced because the two men both kept a "pact of silence" - Gauguin to avoid prosecution and van Gogh in an effort trying to keep his friend with whom he was hopelessly infatuated.

Hans Kaufmann, one of the authors of the book "Pakt des Schweigens" - "Pact of Silence" in English - told ABC News that "the official version is largely based on Gauguin's accounts. It contains inconsistencies and there are plenty of hints by both artists that the truth is much more complex than the story we've all known."

"We carefully re-examined witness accounts and letters written by both artists and we came to the conclusion that van Gogh was terribly upset over Gauguin's plan to go back to Paris, after the two men had spent an unhappy stay together at the "Yellow House" in Arles, Southern France, which had been set up as a studio in the south."

"On the evening of December 23, 1888 van Gogh, seized by an attack of a metabolic disease, became very aggressive when Gauguin said he was leaving him for good. The men had a heated argument near the brothel and Vincent might have attacked his friend. Gauguin, wanting to defend himself and wanting to get rid of 'the madman' drew his weapon and made a move towards van Gogh and by that he cut off his left ear."

"We do not know for sure if the blow was an accident or a deliberate attempt to injure van Gogh, but it was dark and we suspect that Gauguin did not intend to hit his friend."

Gauguin left Arles the next day and the two men never saw each other again.

In the first letter that Vincent van Gogh wrote after the incident, he told Gauguin, "I will keep quiet about this and so will you." That apparently was the beginning of the "pact of silence."

Years later, Gauguin wrote a letter to another friend and in a reference about van Gogh he said, "A man with sealed lips, I cannot complain about him."

Kaufmann also cites correspondence between van Gogh and his brother Theo, in which the painter hints at what happened that night without directly breaking the "pact of silence" - he writes that "it is lucky Gauguin does not have a machine gun or other firearms, that he is stronger than him and that his 'passions' are stronger."

"There are plenty of hints in the documents we had at our disposal that prove the self-harm version is incorrect, but to the best of my knowledge, neither of the friends ever broke the pact of silence," says Kaufmann, who suggests that the story about van Gogh's ear needs to be re-written.

Vincent van Gogh, who painted The Starry Night, Sunflowers and the Potato Eaters but also a self-portrait with his bandaged ear to name but a few, died in 1890 from a self-inflicted gunshot wound at the age of 37. Gauguin died in 1903 at age 54.

Copyright © 2009 ABC News Internet Ventures

Heather wrote: "

Heather wrote: "THE REAL STORY BEHIND VAN GOGHS SEVERED EAR

Historians Now Claim That van Gogh Lost His Ear in a Fight With Fellow Artist Paul Gauguin

By CHRISTEL KUCHARZ

PASSAU, Germany, May 5, 2009

He's know..."

Yes,I read this one in the other post...thank you Heather.

I know that the self portrait you've posted here is by VG, what about Gauguin's portrait , is it by VG as well?

I was going to comment that it was after an arguement with Gauguin. That's been known for some time. Heather send me your snail mail address off list.

I was going to comment that it was after an arguement with Gauguin. That's been known for some time. Heather send me your snail mail address off list.

Poor Vincent. How terribly sad that both of these explanations are perfectly plausible. Funny to think of a man this passionate creating paintings so defined by masterly control.

Poor Vincent. How terribly sad that both of these explanations are perfectly plausible. Funny to think of a man this passionate creating paintings so defined by masterly control.

An illuminating show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, "The Drawings of Bronzino," on view through April 18. Astonishingly, it's the first exhibition ever dedicated to this fascinating Florentine master, renowned in his day as both artist and poet. The son of a butcher, Bronzino became court painter to Cosimo I de' Medici and his wife, the sloe-eyed Eleonora di Toledo—the woman with the pearls in the Uffizi—entrusted with portraits of the noble family and, among other important commissions, the decoration of Eleonora's private chapel in the Palazzo Vecchio, designs for monumental tapestry cycles, and numerous devotional paintings, including a fresco of the martyrdom of St. Lawrence for the church of San Lorenzo, where the Medici worshiped. (And that's not to mention all those portraits of upper-class types like that fashionably dressed boy at the Frick.)

The Metropolitan's exhibition includes nearly all of the 61 surviving drawings by or attributed to Bronzino, all of them made as studies, explorations of ideas, and/or preparations for finished works in other mediums. Some are carefully developed visions of individual figures who appear in Bronzino's paintings, while others present elaborate compositional schemes, and still others test possibilities or record searches for definitive forms. We come to recognize typical characters—round-faced children, curly-haired young men, heavy-lidded, long-necked women—but there's considerable variation, over time, in Bronzino's handling of the red or black chalk he habitually employed.

In the preparations for a painting of the contest between Apollo and Marsyas, made about 1530-32, Bronzino responds to anatomy with disjunctive touches of tone and bold, expressive contours. About 10 years later, in a study of male crossed legs, he minimally suggests sturdy musculature with broad passages of delicate hatching, disciplined by an incisive, simplified outline. A late preparatory modello, made about 1565, for "The Virtues and Blessings of Matrimony Expelling the Vices and Ills"—a decoration for a Medici wedding—is even simpler; although every inch is filled with athletic nudes, their vigorous physiques are indicated mainly by crisp contours and the smallest possible amount of economically placed shading.

No drawing seems to anticipate fully the enameled surfaces and seamless tonal shifts of Bronzino's paintings. In the surviving studies for portraits, the subjects seem more animated, more vividly characterized, and more nervous than they do in the meticulously finished paintings. Yet as we view the drawings, sometimes troubled by an emphasis on detail that disrupts the whole, sometimes seduced by virtuoso, assured passages, we realize that the probing observation that informs the chalk studies underlies even the suavest, most idealized of Bronzino's paintings—sometimes literally, in the form of incised lines, as recent technical studies of a portrait belonging to the Metropolitan reveal; the draftsman's intense attention to actuality strengthened his paintings.

The exhibition also reminds us of how Renaissance artists were trained. Bronzino was apprenticed early to Jacopo Pontormo, who was only nine years older. (Their close friendship endured for over four decades.) As required, the young Bronzino learned to emulate his master's soft, smoky drawing style, so successfully that the attributions of some included works have shifted between the two artists, while others have been identified as collaborations from Bronzino's time with Pontormo. By the mid-1530s, Bronzino was on his own, working for the Medici. His drawings are now more individual: a distinctive combination of an awareness of Leonardo-esque delicate shading and a love of Michelangelo's vigorous articulation of bodies in space. Bronzino's horror vacui style is largely his own—those tightly packed expanses, especially in his later works, filled with twisting, angled Michelangelo-inspired figures, limbs opposed to limbs, bodies to bodies.

Toward the end of his career, Bronzino still received important commissions, but fewer of them, since the death of Eleanora deprived him of his strongest supporter; Cosimo I preferred Giorgio Vasari's crabbed style. And, as the exhibition makes clear, some of those jam-packed late works are distinctly problematic. The drawings for even the most airless of Bronzino's late works are, nonetheless, brilliant. The entire exhibition changes our perceptions of his paintings. I'll never look at that beautiful boy at the Frick the same way again.

By KAREN WILKIN

Ms. Wilkin writes about art for the Journal.

Monica wrote: "THANK YOU!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!"

Monica wrote: "THANK YOU!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!"Yeah, I thought of you, Monica, when I found this article. When are you going out there?

As soon as I can figure it out!!!!!!!!!!!!! I have a friend or two who want to go to NY, too!!

As soon as I can figure it out!!!!!!!!!!!!! I have a friend or two who want to go to NY, too!!I'm gonna send you a regular email. Look for it in your email program.

THERE'S LITTLE ROOM FOR ARTISTIC LICENSE HERE

THERE'S LITTLE ROOM FOR ARTISTIC LICENSE HERE

By DANIEL GRANT

Nothing marks the cultural philistine more than the comment at an art show, "Hey, nobody really looks like that!" Of course, Picasso took great liberties with the placement of eyes and noses when he painted those figures in "Demoiselles d'Avignon"; de Kooning knew when he began his "Woman" series of paintings that women didn't look like clowning monsters. The one was experimenting with forms and perspectives, while the other was expressing outwardly what was felt internally. It is understood that artists can rework the world in their paintings and sculptures to reveal a different, less literal, type of truth. Accuracy matters on term papers, not in art.

Well, maybe with some art. "I had an argument with a fellow once about the eye color of a mockingbird," said Melanie Fain, a wildlife artist in Boerne, Texas, who had this exchange in her booth at an art fair. "A golden color is what I saw when I painted it, but maybe mockingbirds in Austin look different than those in San Antonio." In any event, "he wanted to catch me doing something wrong."

She shouldn't take it personally. All artists who focus on wildlife, historical and nautical scenes are confronted on a regular basis by people who are knowledgeable in these fields—outdoorsmen, hunters, birders, Civil War re-enacters, military historians (or military buffs), yachtsmen and boating enthusiasts—looking for mistakes. "People test me all the time," said Jan Martin McGuire, a wildlife artist in Bartlesville, Okla. "I once did a painting of a meadowlark sitting on a metal fence in a western setting, and a man came up to me and asked if that was an eastern meadowlark or a western meadowlark. I told him that the only difference between the eastern and western meadowlark is the song they sing and, otherwise, there was no difference in their plumage. He just walked away."

John Warr, a painter in Scottsboro, Ala., said that he knows how disputatious wildlife enthusiasts can be ("I call them feather-counters"), but they are nothing compared to Civil War buffs, his other subject area. "Civil War collectors are so much pickier, and they point out things more, especially in weapons." A sharp-eyed observer noticed in one of his paintings that the cannon balls being used by Confederates were actually Union balls. For him, "the good thing about painting Confederate soldiers is that they wore and used equipment that they found; it was a mismatch of everything," allowing Mr. Warr to depict a range of historically appropriate shoes, hats, clothing and guns. Federal soldiers, on the other hand, "had government issue," which makes painting them less interesting.

With Confederate Civil War generals, on the other hand, there is no room for improvisation, and artists better know their minutiae. For example, Nathan Bedford Forrest was left-handed, which affected where he carried his sword. John Hunt Morgan never wore a general's jacket into battle, because Union snipers took aim at opposing generals to put their regiments into disarray. A particular general wore a specific coat at one battle and another coat at a different engagement.

Confederate flags were often homemade, while the flags of Northern volunteer regiments were produced by their state governments; the canteens, haversacks, horse tack, hats, uniforms, artillery, guns of all types—the specifics are endless and everything. The process of learning what questions to ask and where to find answers turns artists into historians.

How to research is not taught in studio art classes, but it is a skill artists in the accuracy trade need to acquire. Ms. Fain has thousands of photographs (hers and other people's) in a filing cabinet and close to a hundred birds in her freezer; when needed, she will take a bird out and thaw it partially in order to "spread a wing out and see the colors of the feathers and how long the feathers are." Ms. McGuire has "a whole library" of books on African wildlife, and she has traveled to Africa more than a dozen times to photograph animals that she may later paint.

Research takes many forms. Ms. Fain has a bird-call app on her iPhone, which helps attract ducks that she photographs in the wild and occasionally shoots with her gun, providing her with food for thought and food for dinner. William Beebe, a marine artist in Williamsburg, Va., travels to marinas to take one photograph after another—broad images and detailed shots—of ships and boats that might be used in a painting. These photographs are from many different angles, "because you never know from what vantage point someone commissioning a painting is going to want to see the boat." Once, he was challenged by someone on the position of a rudder handle in a painting of a schooner, "but I had worked from a photograph, and I know I got it right and the other fellow didn't."

Mr. Warr learned about Gen. Morgan's jackets from the John Hunt Morgan Society (an informal group composed of descendants and others) and about Gen. Forrest's left-handedness from a local history-buff lawyer. Finding out whom to ask is key, and they are not the usual suspects; university professors may be well-versed in the politics of the Civil War, but not necessarily the kinds of information that help an artist paint an accurate picture of what someone who might have been there would have seen: the crops grown in that field, the weather that day, the length of so-and-so's sleeves, the flag a specific regiment was carrying that day, how tall this person was, how far apart lines of troops marched, the percentage of soldiers who wore no uniform at all, the roofing on that house and whether the building in the distance was painted that color (or painted at all).

All the detective work, the attention to detail and facts, may obscure the artist's other important goal—to create an interesting picture. It is a difficult balancing act. "Beauty is truth, truth beauty," Keats famously wrote, but the poet clearly sided with beauty over facts. Mr. Beebe noted that schooners have "a tremendous number of lines, and there are a lot of connection points where ropes meet a pulley. It can take away from the painting if you have to put in every rope and every cleat." For that reason, he tends to depict these ships at a distance, requiring less detail and making the overall painting "more appealing to the eye." If he has done that well, he figures, people will forgive the small mistakes.

Mr. Grant is the author of "The Business of Being an Artist" (Allworth).

By Michael Upchurch

By Michael UpchurchSeattle Times arts writer

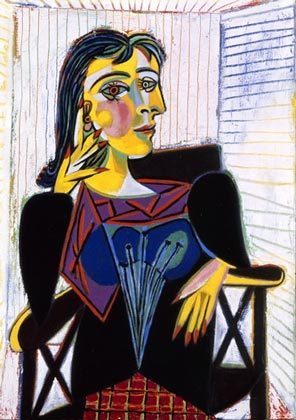

PABLO PICASSO

"Portrait of Dora Maar," part of the exhibit, shows Picasso's iconic "leap of perception."

When the Musée National Picasso, Paris, closed its doors in August for a $28 million renovation, the scoop was that its 5,000 artworks by Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) would be locked away for more than two years.

The museum would stop lending out Picasso artworks, The Associated Press reported, while experts updated, computerized and restored its inventory.

Well, someone somewhere along the line changed his or her mind.

And the Seattle Art Museum is the first American beneficiary of that change of heart.

"Picasso: Masterpieces from the Musée National Picasso, Paris," an exhibit of more than 150 works of art, from paintings and sculptures to prints, drawings and photographs, opens at SAM on Oct. 8 and will be on display through Jan. 9, 2011.

The exhibit will cover every phase in Picasso's protean career, from the dawn of the 20th century through works dating from the early 1970s, including his 1970 self-portrait "The Matador."

SAM director Derrick Cartwright calls this "a once-in-a-lifetime chance for a large public to view these important objects in Seattle."

Added Chiyo Ishikawa, co-curator with Michael Darling of the show's Seattle stop: "The exhibition presents an entire sweep of Picasso's career, documenting the full range of his unceasing inventiveness and creative process."

"Picasso never liked to rest on his laurels," Darling said. "This prompted him to always move on before any one expressive mode began to run thin."

Highlights will include "La Celestina" (from his famous Blue Period), "The Two Brothers" (from his Pink Period) and the exuberant "Two Women Running on the Beach (La Course)" from 1922.

"Portrait of Dora Maar" (1937) finds him taking a multiplaned approach to the human figure — in this case, his mistress Dora Maar, a surrealist photographer. Jonathan Jones, writing in The Guardian's "Portrait of the Week" column, ascribed to the painting "the kind of leap of perception that caricaturists loved to parody in Picasso, and that enables his art to say two or 200 things at once. ... Her presence transcends the physical."

The most unusual thing about the Musée Picasso's collection is that it comprises works that Picasso kept for himself. This is the artist's personal record of his eight-decade-long career.

The Musée National Picasso, Paris, opened in Paris' Marais neighborhood in 1985. Housed in a converted 17th-century mansion, the museum has room to display only 300 or fewer works at a time — a clear source of frustration for museum director Anne Baldassari, who told The Associated Press, "We can't continue like this."

Along with expanding exhibit space, renovations will address "electrical problems," enhance accessibility for disabled visitors and create additional venues for student activities. The museum is scheduled to reopen in early 2012.

In the meantime, "Picasso: Masterpieces from the Musée National Picasso, Paris" just closed in Helsinki, Finland's Ateneum Art Museum, where it attracted record crowds, and is about to open in Moscow's Pushkin Museum. The exhibit likely will go to two more U.S. cities — still to be confirmed — after it leaves Seattle.

Along with the Olympics, Vancouver’s art scene is geared up to impress its share of the thousands of people soon to flood the city. The Vancouver Art Gallery will be exhibiting a rare collection of Leonardo da Vinci’s anatomical drawings from February 6th to May 2nd. It will be the first time that “Anatomical Manuscript A” will be shown to the public as a complete set since da Vinci drew them in the early 1500’s. The exhibit concentrates on the movements of musculature and the structures of the human body, a very fitting collection considering the large amount of muscled athletes that will be in Vancouver for the Olympics. Not that most of us need any help imagining them without their uniforms. The exhibit will be free for the duration of the Olympics, February 12th-28th, although it might be so busy during that time that you’ll be touching a few human bodies as well looking at them.

A reference or 'clip' file is something most artists have but I didn't know they kept freezers full of dead animals for the purpose. I have one artist friend who keeps an eagle wing in his freezer and has used it's image in his work. One of my dearest friends since high school is a botanical illustrator of the highest order (spiralfern.net) and her specimen only last just so long, but for her rendering them.

A reference or 'clip' file is something most artists have but I didn't know they kept freezers full of dead animals for the purpose. I have one artist friend who keeps an eagle wing in his freezer and has used it's image in his work. One of my dearest friends since high school is a botanical illustrator of the highest order (spiralfern.net) and her specimen only last just so long, but for her rendering them.------------------------

Where is the Bronzino article from? The Wall Street Journal?

Paperchase forced to deny it copied artist's work after Twitter backlash

Paperchase forced to deny it copied artist's work after Twitter backlashBy Chris Green The Independent Art

A British artist has accused the stationery chain Paperchase of copying one of her designs and reproducing it on thousands of bags, notebooks and albums without her permission.

The artist, who calls herself Hidden Eloise, sells illustrations through the online shop Etsy, many of which feature a picture of a girl with long dark hair. On a blog post on her website, the 28-year-old, from London, claimed that her design had been redrawn and used on numerous Paperchase products.

“My lovely girl from the artwork...has been stolen, badly traced and stuck in front of a poor (and separately traced) mushroom that now decorates untold numbers of notebooks, albums and tote bags sold throughout the UK through Paperchase and Amazon.co.uk,” she wrote.

http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-ent...

I know a photographer who was told her photo was to be used on a "Wall of Fame" in the client's office. Then she saw it on a billboard! How stupid! Instead of a small usage fee the 'a'hole had to pay $50,000.00

I know a photographer who was told her photo was to be used on a "Wall of Fame" in the client's office. Then she saw it on a billboard! How stupid! Instead of a small usage fee the 'a'hole had to pay $50,000.00

[image error]

[image error]Andy Warhol: The Last Decade

Andy Warhol: The Last Decade features nearly 50 works by Warhol and examines how he simultaneously worked with the screened image and pursued a reinvention of painting in his late work. Created amidst the bustle of Warhol’s Pop celebrity, the works included illustrate the artist’s vitality, energy, and renewed spirit of experimentation. During those final years, Warhol produced more works, in a greater number of series, than at any other time.

Critical to Warhol’s reinvention of painting was the revival of the medium by the Neo-Expressionist painters. Warhol was both enamored with the new painting and challenged by it. He relished the youthful vitality of artists such as Jean-Michel Basquiat, Francesco Clemente, Keith Haring, and Julian Schnabel. Seeing the energy in their work and witnessing their popularity, Warhol began to work with new enthusiasm and eventually produced an extended series with Basquiat. His intimate working relationship with Basquiat during the years of 1983-84 certainly expanded his repertoire of painting techniques and dramatically increased his production-a stimulus that carried the artist through the end of his career.

http://www.dallasartnews.com/2009/10/...

Continue reading at Dallas Art News to find out about his ideas, reasoning, and success behind the last decade of his artistic movement.

Exhibition Itinerary

Milwaukee Art Museum (September 26, 2009-January 3, 2010)

Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth (February 14-May 16, 2010)

Brooklyn Museum (June 18-September 12, 2010)

Baltimore Museum of Art (October 17, 2010-January 9, 2011)

Filling the Void

Filling the Void

NEW YORK -- With the available money for ambitious new buildings having shrunk to almost nothing in this country -- and with firms continuing to downsize in brutal fashion -- where will architectural ideas come from, and where will they wind up? What kind of impact will they have on the wider culture?

Those are among the tricky questions raised by "Contemplating the Void," an exhibition that opened last week at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. As part of its ongoing 50th anniversary celebration, the museum invited nearly 200 architects, artists and designers to propose fanciful new uses for the 90-foot-high rotunda of its Frank Lloyd Wright-designed building. Curators Nancy Spector and David van der Leer asked the participants, whose biggest names include Anish Kapoor, Zaha Hadid, Richard Meier, Toyo Ito and Rachel Whiteread, to leave "practicality and even reality behind" as they produced ideas for filling the space inside Wright's famous spiraling ramp.

The uneven results suggest there is one skill that will be more important for architects than any other as credit remains tight and cranes idle. I am tempted to call this skill the ability to make something out of nothing. But it is actually a slight twist on that idea that will be most valuable -- knowing how to make nothing mean something.

http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/cultu...

-- Christopher Hawthorne

In 1970 'performance art', an off shoot of 'guerilla theater', was still prevalent. On a class trip some of us brought roller skates to the Guggenheim. One guy was really good and made it around several levels. I only made it 1/4 of the way around one level -- had to stop myself before crashing into the artwork. I never was very athletic but my heat was in the right place!

In 1970 'performance art', an off shoot of 'guerilla theater', was still prevalent. On a class trip some of us brought roller skates to the Guggenheim. One guy was really good and made it around several levels. I only made it 1/4 of the way around one level -- had to stop myself before crashing into the artwork. I never was very athletic but my heat was in the right place!

That would be so awesome to roller skate the Guggenheim! I would be afraid to crash into some of the art, too, not being very adept at skating anyway. I think it is a beautiful structure.

That would be so awesome to roller skate the Guggenheim! I would be afraid to crash into some of the art, too, not being very adept at skating anyway. I think it is a beautiful structure.

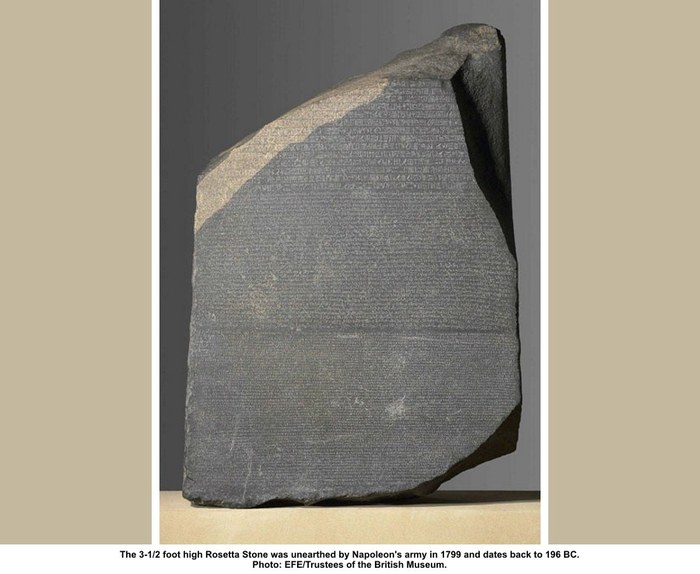

The Rosetta Stone

The Rosetta Stone

From LONDON (REUTERS), Editing by Paul Casciato

The head of Egypt's Supreme Council of Antiquities said he plans to ask the British Museum to hand the Rosetta Stone over to his country. The ancient stone was the key to deciphering hieroglyphs on the tombs of Egyptian pharaohs and is one of six ancient relics that Egypt's chief archaeologist Zahi Hawass said his country wants to recover from museums around the world. The 3-1/2 foot high Rosetta Stone was unearthed by Napoleon's army in 1799 and dates back to 196 BC. It became British property after Napoleon's defeat under the 1801 Treaty of Alexandria.

"I did not write yet to the British Museum but I will. I will tell them that we need the Rosetta Stone to come back to Egypt for good," Hawass told Reuters this weekend.

"The British Museum has hundreds of thousands of artifacts in the basement and as exhibits. I am only needing one piece to come back, the Rosetta Stone. It is an icon of our Egyptian identity and its homeland should be Egypt."

Hawass, whose flamboyant style and trademark hat have led some to liken him to film character Indiana Jones, has in the past said he wanted to acquire the stone for Egypt and now wants to go about it through official channels.

His wish list for relics also includes the bust of Nefertiti from Berlin's Neues Museum, a statue of Great Pyramid architect Hemiunu from the Roemer-Pelizaeus Museum in Hildesheim, Germany, the Dendera Temple Zodiac from the Louvre in Paris, Ankhaf's bust from Boston's Museum of Fine Art and a statue of Rameses II from the Museo Egizio in Turin, Italy.

The Rosetta Stone, which has inscriptions in hieroglyphic, demotic and Greek, has been housed at the British Museum since 1802 and forms the centerpiece of the museum's Egyptian collection, attracting millions of visitors each year.

Hawass had previously asked to borrow the stone for the opening of a new museum in Giza, near Cairo in 2012, but said he would no longer settle for just a loan. The British Museum said in a statement that its collection should remain as a whole to fulfill the museum's purpose, and it would consider the request for a loan to Egypt in due course.

David Gill, reader in Mediterranean archaeology at Swansea University, said the British Museum would be cautious about handling the request as it could lead to increased pressure over other items in its collection, such as the Parthenon marbles.

"The whole issue for the British Museum is if they say we're going to give you back the Rosetta Stone, it sets a precedent," he said. "They're worried that countries like Italy, Greece and Turkey are going to demand large numbers of objects back."

Masako Muro, a 34-year-old tourist in London from Japan, said she felt that the Rosetta Stone should remain in London, at least for the benefit of visitors.

"It is easy to travel here especially for tourists compared to traveling to Egypt. And that makes it open to everybody," she said.

This was a good article, Andrew. I can see both points of view. I think the Rosetta Stone should be returned to Egypt, but then again, having it in London does make it more easily accessible for tourists. No matter where it is housed, the Stone will still command respect for its Egyptian history. Also, if the British Museum gives in to giving back the Rosetta Stone to Egypt, they might, in time, have to give up other relics to other countries, also. It's a touchy situation for everyone involved.

This was a good article, Andrew. I can see both points of view. I think the Rosetta Stone should be returned to Egypt, but then again, having it in London does make it more easily accessible for tourists. No matter where it is housed, the Stone will still command respect for its Egyptian history. Also, if the British Museum gives in to giving back the Rosetta Stone to Egypt, they might, in time, have to give up other relics to other countries, also. It's a touchy situation for everyone involved.

The museum where I volunteer had a similar situation and decided to return the artworks. Now we have a great relationship with those museums and it has made it easier, I believe, to get artworks on loan for exhibits.

The museum where I volunteer had a similar situation and decided to return the artworks. Now we have a great relationship with those museums and it has made it easier, I believe, to get artworks on loan for exhibits.

I am always of mixed mind when it comes to artifacts and art from other countries. On the one hand, it is their immediate heritage and should belong to them. On the other hand, it is the common heritage of all of us in which we want to share.

I am always of mixed mind when it comes to artifacts and art from other countries. On the one hand, it is their immediate heritage and should belong to them. On the other hand, it is the common heritage of all of us in which we want to share.

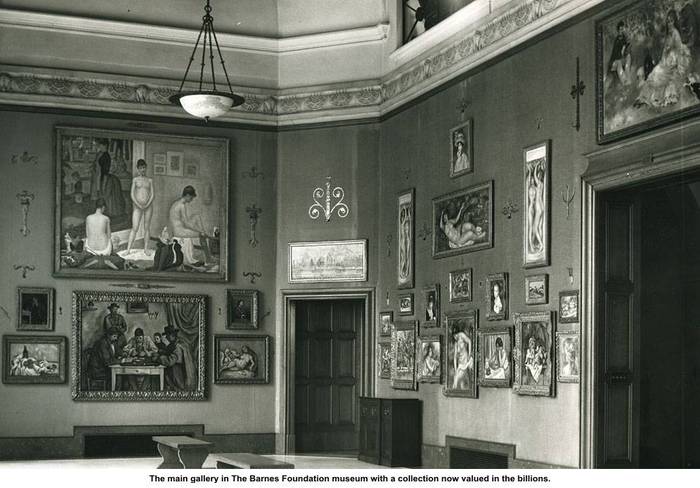

Film Chronicles the Dramatic Struggle for Control of the Barnes Foundation

Film Chronicles the Dramatic Struggle for Control of the Barnes Foundation

SAN FRANCISCO, CA.- The "Art of the Steal" chronicles the long and dramatic struggle for control of the Barnes Foundation, a private collection of Post-Impressionist and early Modern art valued at more than $25 billion. "THE ART OF THE STEAL", an IFC Film, runs 101 minutes, is in English, and is not yet rated by the MPAA. In 1922, Dr. Albert C. Barnes created The Barnes Foundation in Lower Merion Pennsylvania, five miles outside of Philadelphia with the intention of using his remarkable collection of Post-Impressionist and early modern art as an educational institution. Dr. Barnes built his foundation away from the city and the cultural elite who originally scorned his collection as "horrible, debased art," and set it on the grounds of his own home, an arboretum in the leafy suburbs.

Tastes changed, and soon the very people who belittled Barnes wanted access to his collection. When Dr. Barnes died in a car accident in 1951, he left control of his collection to Lincoln University, a small African-American college. His will contained strict instructions, stating the foundation shall always have an educational mission and that the paintings were never to be removed. Such strict limitations made the collection safe from commercial exploitation. But was it really safe?

More than fifty years later, a powerful group of moneyed interests have gone to court to take the art - recently valued at more than $25 billion - and bring it to a new museum in Philadelphia. Standing in their way is a group of former students who are trying to block the move. Will the students succeed, or will a man's Last Will and Testament be broken and one of America's greatest cultural monuments be destroyed?

Giorgio de Chirico Portrait of Dr. Albert C. BarnesAbout the Filmmakers:

Don Argott, Director/Cinematographer

Don Argott is a cinematographer, producer and director. Originally from northern New Jersey, he graduated from the Art Institute of Philadelphia in 1994. Upon graduation, Argott opened and co-owned Mini Mace Pro Pictures, where he worked on countless corporate and commercial videos and short films as a DP and director. He also worked as a DP/camera op for FOX Sports, ESPN, NBC, and TLC/Discovery.

In 2002, Argott parted ways with his business partner, and started 9.14 Pictures with producer Sheena M. Joyce. ROCK SCHOOL, the company's first feature-length documentary, premiered at the Los Angeles Film Festival in 2004. TWO DAYS IN APRIL, 9.14's second feature-length documentary, followed four college football players as they entered the NFL Draft. "THE ART OF THE STEAL" is their third film.

Lenny Feinberg, Executive Producer

Lenny Feinberg is a real estate investor, mountaineer and wine drinker. A former student of the Barnes Foundation, Dr. Barnes' philosophy has had a significant influence on his life. He initiated, funded, and was intimately involved in the making of THE ART OF THE STEAL, which is his first film. He is presently developing new documentary projects.

Sheena M. Joyce

Sheena M. Joyce graduated from Bryn Mawr College with a BA in English in 1998. Upon graduation, Joyce began her film career as an employee of the Greater Philadelphia Film Office, marketing the area to the production industry for almost five years. In 2002, she formed 9.14 Pictures with director Don Argott. ROCK SCHOOL, the company's first feature-length documentary, and Joyce's first as producer, was released in 2005. This was followed by TWO DAYS IN APRIL.

Barnes must have had a real eye for art to see in his works something of value even when he was criticized by others. Now we see what that value really is! His intentions were pure in wanting to save the art for educational purposes. I really hope the students win on this one. Guess I will have to watch the film, it looks fascinating!

Barnes must have had a real eye for art to see in his works something of value even when he was criticized by others. Now we see what that value really is! His intentions were pure in wanting to save the art for educational purposes. I really hope the students win on this one. Guess I will have to watch the film, it looks fascinating!

The trouble with the museum as set up by Barnes is that very few people could see the collection. You had to apply for the privilege of making an appointment. And they were very selective about who they let in.

The trouble with the museum as set up by Barnes is that very few people could see the collection. You had to apply for the privilege of making an appointment. And they were very selective about who they let in.

Not exactly so Ruth cause it's a house so heards of people couldn't just show up unannounced. All the artwork was moved out so the building could be restored and iirc they were displayed at the Philly Art Museum. I saw the collection there at that time, I believe in the late 1990s. it was jaw-droppingly gorgeous. Paintings that have never left his home. Some by Monet on his little house boat that are shockingly beautiful. I went to Le Bec Vin with my mom and saw the collection at Princeton on the same trip. Fond memories.

Not exactly so Ruth cause it's a house so heards of people couldn't just show up unannounced. All the artwork was moved out so the building could be restored and iirc they were displayed at the Philly Art Museum. I saw the collection there at that time, I believe in the late 1990s. it was jaw-droppingly gorgeous. Paintings that have never left his home. Some by Monet on his little house boat that are shockingly beautiful. I went to Le Bec Vin with my mom and saw the collection at Princeton on the same trip. Fond memories.My aunt told me Dr. Barnes invented a solution that was put in newborns eyes. It was before my time so someone who knows more can fill us in.

Saying all that. If I were the judge there would be no contest. Honor the deceased's will.

Yes, he was the inventor of Argyrol, which was a silver nitrate solution. It was squirted in babies' eyes as a disinfectant.

Yes, he was the inventor of Argyrol, which was a silver nitrate solution. It was squirted in babies' eyes as a disinfectant.He was a millionaire by 1910, which is when he got into art collecting, and exceptionally lucky in his timing in 1929.

That's really interesting! Do they still use the Argyrol? Did it have any bad side effects that caused it to be discontinued? I've never heard of it, what a bright and lucky man!

That's really interesting! Do they still use the Argyrol? Did it have any bad side effects that caused it to be discontinued? I've never heard of it, what a bright and lucky man!

Monica wrote: "Not exactly so Ruth cause it's a house so heards of people couldn't just show up unannounced. All the artwork was moved out so the building could be restored and iirc they were displayed at the Phi..."

Monica wrote: "Not exactly so Ruth cause it's a house so heards of people couldn't just show up unannounced. All the artwork was moved out so the building could be restored and iirc they were displayed at the Phi..."I realize why they couldn't show up. But it still limited the audience to a very select few. I'm not saying I know what the answer is. In fact, I think in this case there is no good answer.

As for the silver nitrate solution. It was used as a disinfectant in the eyes of newborns, mostly as a protection against gonorrhea. It's no longer used because antibiotics have replaced it. (I'm married to a retired ob/gyn.)

I've been through Marjorie Merriweather's house in DC where it's the same sort of thing. Lots of places you have to call fIrst. http://www.hillwoodmuseum.org/mmp.html

I've been through Marjorie Merriweather's house in DC where it's the same sort of thing. Lots of places you have to call fIrst. http://www.hillwoodmuseum.org/mmp.htmlFrederick Church's Olana on the Hudson is more accessible but it's a NY landmark so the state takes care of it.

http://www.olana.org/visit.php

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia...

His teacher Thomas Cole's house is ramshackle but I believe it's being worked on.

Maybe this should be it's own thread--artistic homes- travel destinations.