The History Book Club discussion

SUPREME COURT OF THE U.S.

>

#93 - ASSOCIATE JUSTICE BYRON WHITE

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

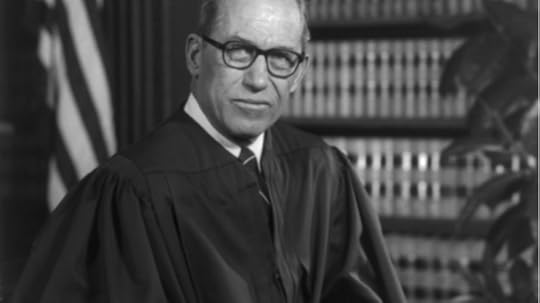

Byron Raymond "Whizzer" White (June 8, 1917 – April 15, 2002) won fame both as a football halfback and as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. Appointed to the court by President John F. Kennedy in 1962, he served until his retirement in 1993. He was married to Marion Lloyd Stearns in 1946 and the father of two children, Charles (Barney) Byron White and Nancy Pitkin White.

Byron Raymond "Whizzer" White (June 8, 1917 – April 15, 2002) won fame both as a football halfback and as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. Appointed to the court by President John F. Kennedy in 1962, he served until his retirement in 1993. He was married to Marion Lloyd Stearns in 1946 and the father of two children, Charles (Barney) Byron White and Nancy Pitkin White.White was born in Fort Collins, Colorado. He was raised in the nearby town of Wellington, Colorado, where he obtained his high school diploma in 1930. He made a point of returning to Wellington on an annual basis for his high school reunions up until 1999 when his physical health worsened significantly. He died in Denver at the age of 84 from complications of pneumonia. He was the first and only Supreme Court Justice from the state of Colorado.

Education

After graduating at the top of his Wellington high school class, White attended the University of Colorado at Boulder on a scholarship. He joined the Phi Gamma Delta fraternity and served as student body president his senior year. Graduating in 1938, he won a Rhodes Scholarship to the University of Oxford and, after having deferred it for a year to play football, he went on to attend Hertford College, Oxford.

Football

White was an All-American football halfback for the Colorado Buffaloes of the University of Colorado at Boulder, where he acquired the nickname "Whizzer" from a newspaper columnist. The nickname would follow him throughout his later legal and Supreme Court career, to White's chagrin. He also played basketball and baseball. After graduation he signed with the NFL's Pittsburgh Pirates (now Steelers),playing there during the 1938 season. He led the league in rushing in his rookie season and became the game's highest-paid player.

Of all the athletes I have known in my lifetime, I'd have to say Whizzer White came as close to anyone to giving 100 percent of himself when he was in competition.

~- Pittsburgh Pirates/Steelers owner Art Rooney

After Oxford, White played for the Detroit Lions from 1940 to 1941. In three NFL seasons, he played in 33 games. He led the league in rushing yards in 1938 and 1940, and he was one of the first "big money" NFL players, making $15,000 a year. His career was cut short when he entered the United States Navy during World War II; after the war, he elected to attend law school rather than return to football. He was elected to the College Football Hall of Fame in 1954.

Military service

During World War II, White served as an intelligence officer in the United States Navy stationed in the Pacific Theatre. He had originally wanted to join the Marines but was kept out due to being colorblind. He wrote the intelligence report on the sinking of future President John F. Kennedy's PT-109. White was awarded two Bronze Star medals.

Personal life

White married Marion Stearns, the daughter of the president of the University of Colorado, and they would eventually have one son, Charles, and one daughter, Nancy.

Legal career

After World War II, he attended Yale Law School, graduating magna cum laude in 1946. During his years at Yale Law, he served as Chairman of the Conservative Party of the Yale Political Union, preceded by Homer Daniels Babbidge and succeeded by Johnston Redmond Livingston. After serving as a law clerk to Chief Justice Fred Vinson, White returned to Denver.

White practiced in Denver for roughly fifteen years with the law firm now known as Davis Graham & Stubbs. This was a time in which the Denver business community flourished, and White rendered legal service to that flourishing community. White was for the most part a transactional attorney. He drafted contracts and advised insolvent companies, and he argued the occasional case in court.

During the United States presidential election, 1960, White put his football celebrity to use as chair of John F. Kennedy's campaign in Colorado. White had first met the candidate when White was a Rhodes scholar and Kennedy's father, Joseph Kennedy, was Ambassador to the Court of St. James. During the Kennedy administration, White served as United States Deputy Attorney General, the number two man in the Justice Department, under Robert F. Kennedy. He took the lead in protecting the Freedom Riders in 1961, negotiating with Alabama Governor John Malcolm Patterson.

Supreme Court

Supreme CourtAcquiring renown within the Kennedy Administration for his humble manner and sharp mind, he was appointed by Kennedy in 1962 to succeed Justice Charles Evans Whittaker, who retired for disability. Kennedy said at the time: "He has excelled at everything. And I know that he will excel on the highest court in the land." The 44-year-old White was approved by a voice vote. He would serve until his retirement in 1993. His Supreme Court tenure was the fourth-longest of the 20th century.

Upon the request of Vice President-Elect Al Gore, Justice White administered the oath of office on January 20, 1993 to the 45th U.S. Vice President. It was the only time White administered an oath of office to a Vice President.

During his service on the high court, White wrote 994 opinions. He was fierce in questioning attorneys in court, and his votes and opinions on the bench reflect an ideology that has been notoriously difficult for popular journalists and legal scholars alike to pin down. He was seen as a disappointment by some Kennedy supporters who wished he would have joined the more liberal wing of the court in its opinions on Miranda v. Arizona and Roe v. Wade.

White often took a narrow, fact-specific view of cases before the Court and generally refused to make broad pronouncements on constitutional doctrine or adhere to a specific judicial philosophy. He preferred to take what he viewed as a practical approach to the law to one based in any legal philosophy. In the tradition of the New Deal, White frequently supported a broad view and expansion of governmental powers. He consistently voted against creating constitutional restrictions on the police, dissenting in the landmark 1966 case of Miranda v. Arizona. In his dissent in that case he noted that aggressive police practices enhance the individual rights of law-abiding citizens. His jurisprudence has sometimes been praised for adhering to the doctrine of judicial restraint.

Substantive due process doctrine

Frequently a critic of the doctrine of "substantive due process", which involves the judiciary reading substantive content into the term "liberty" in the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment and Fourteenth Amendment, White dissented in the controversial 1973 case of Roe v. Wade. But White voted to strike down a state ban on contraceptives in the 1965 case of Griswold v. Connecticut, although he did not join the majority opinion, which famously asserted a "right of privacy" on the basis of the "penumbras" of the Bill of Rights. White and Justice William Rehnquist were the only dissenters from the Court's decision in Roe, though White's dissent used stronger language, suggesting that Roe was "an exercise in raw judicial power" and criticizing the decision for "interposing a constitutional barrier to state efforts to protect human life." White, who usually adhered firmly to the doctrine of stare decisis, remained a critic of Roe throughout his term on the bench.

White explained his general views on the validity of substantive due process at length in his dissent in Moore v. City of East Cleveland: The Judiciary, including this Court, is the most vulnerable and comes nearest to illegitimacy when it deals with judge-made constitutional law having little or no cognizable roots in the language or even the design of the Constitution. Realizing that the present construction of the Due Process Clause represents a major judicial gloss on its terms, as well as on the anticipation of the Framers, and that much of the underpinning for the broad, substantive application of the Clause disappeared in the conflict between the Executive and the Judiciary in 1930s and 1940s, the Court should be extremely reluctant to breathe still further substantive content into the Due Process clause so as to strike down legislation adopted by a State or city to promote its welfare. Whenever the Judiciary does so, it unavoidably pre-empts for itself another part of the governance of the country without express constitutional authority.

White parted company with Rehnquist in strongly supporting the Supreme Court decisions striking down laws that discriminated on the basis of sex, agreeing with Justice William J. Brennan in 1973's Frontiero v. Richardson that laws discriminating on the basis of sex should be subject to strict scrutiny. However, only three justices joined Brennan's plurality opinion in Frontiero; in later cases gender discrimination cases would be subjected to intermediate scrutiny (see Craig v. Boren).

White wrote the majority opinion in Bowers v. Hardwick (1986), which upheld Georgia's anti-sodomy law against a substantive due process attack. The Court is most vulnerable and comes nearest to illegitimacy when it deals with judge-made constitutional law having little or no cognizable roots in the language or design of the Constitution.... There should be, therefore, great resistance to ... redefining the category of rights deemed to be fundamental. Otherwise, the Judiciary necessarily takes to itself further authority to govern the country without express constitutional authority.

White's opinion in Bowers shows the consistency of his commitment to judicial restraint, and his opposition to usurpation of power by the Judiciary. His argument in the case typified White's fact-specific, deferential style of deciding cases: White's opinion treated the issue in that case as presenting only the question of whether homosexuals had a fundamental right to engage in sexual activity, even though the statute in Bowers potentially applied to heterosexual sodomy (see Bowers, 478 U.S. 186, 188, n. 1). A year after White's death, Bowers was overruled in Lawrence v. Texas (2003).

Death penalty

White took a middle course on the issue of the death penalty: he was one of five justices who voted in Furman v. Georgia (1972) to strike down several state capital punishment statutes, voicing concern over the arbitrary nature in which the death penalty was administered. The Furman decision ended capital punishment in the U.S. until 1977, when Gary Gilmore, who decided not to appeal his death sentence, was executed by firing squad. White, however, was not against the death penalty in all forms: he voted to uphold the death penalty statutes at issue in Gregg v. Georgia (1976), even the mandatory death penalty schemes struck down by the Court.

White accepted the position that the Eighth Amendment to the United States Constitution required that all punishments be "proportional" to the crime; thus, he wrote the opinion in Coker v. Georgia (1977), which invalidated the death penalty for rape of a 16-year-old married girl. However, his first reported Supreme Court decision was a dissent in Robinson v. California (1962), in which he criticized the Court for extending the reach of the Eighth Amendment. In Robinson the Court for the first time expanded the constitutional prohibition of “cruel and unusual punishments” from examining the nature of the punishment imposed and whether it was an uncommon punishment − as, for example, in the cases of flogging, branding, banishment, or electrocution − to deciding whether any punishment at all was appropriate for the defendant’s conduct. White said: “If this case involved economic regulation, the present Court's allergy to substantive due process would surely save the statute and prevent the Court from imposing its own philosophical predilections upon state legislatures or Congress.” Consistent with his view in Robinson, White thought that imposing the death penalty on minors was constitutional, and he was one of the three dissenters in Thompson v. Oklahoma (1988), a decision that declared that the death penalty as applied to offenders below 16 years of age was unconstitutional as a cruel and unusual punishment.

Abortion

Along with Justice William Rehnquist, White dissented in Roe v. Wade (the dissenting decision was in the companion case, Doe v. Bolton), castigating the majority for holding that the U.S. Constitution "values the convenience, whim or caprice of the putative mother more than the life or potential life of the fetus."

Civil rights

White consistently supported the Court's post-Brown v. Board of Education attempts to fully desegregate public schools, even through the controversial line of forced busing cases. He voted to uphold affirmative action remedies to racial inequality in an education setting in the famous Regents of the University of California v. Bakke case of 1978. Though White voted to uphold federal affirmative action programs in cases such as Metro Broadcasting, Inc. v. FCC, 497 U.S. 547 (1990) (later overruled by Adarand Constructors v. Peña, 515 U.S. 200 (1995)), White voted to strike down an affirmative action plan regarding state contracts in Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co. (1989).

White dissented in Runyon v. McCrary (1976), which held that federal law prohibited private schools from discriminating on the basis of race. White argued that the legislative history of Title 42 U.S.C. § 1981 (popularly known as the "Ku Klux Klan Act") indicated that the Act was not designed to prohibit private racial discrimination, but only state-sponsored racial discrimination (as had been held in the Civil Rights Cases of 1883). White was concerned about the potential far-reaching impact of holding private racial discrimination illegal, which if taken to its logical conclusion might ban many varied forms of voluntary self-segregation, including social and advocacy groups that limited their membership to blacks: "Whether such conduct should be condoned or not, whites and blacks will undoubtedly choose to form a variety of associational relationships pursuant to contracts which exclude members of the other race. Social clubs, black and white, and associations designed to further the interests of blacks or whites are but two examples". Runyon was essentially overruled by 1989's Patterson v. McLean Credit Union, which itself was superseded by the Civil Rights Act of 1991.

Relationships with other justices

White said that he was most comfortable on Rehnquist's court. He once said of Earl Warren, "I wasn't exactly in his circle." On the Burger Court, the Chief Justice was fond of assigning important criminal procedure and individual rights opinions to White, because of his frequently conservative views on these questions.

Court operations and retirement

White frequently urged that the Supreme Court should consider cases when federal appeals courts were in conflict on issues of federal law, believing that a primary role of the Supreme Court was to resolve such conflicts. Thus, White voted to grant certiorari more often than many of his colleagues, and he wrote numerous opinions dissenting from denials of certiorari. After White (along with fellow Justice Harry Blackmun, who also took a liberal line in voting to grant certiorari) retired, the number of cases heard each session of the Court declined steeply.

White disliked the politics of Supreme Court appointments. During his interviews for clerks, he mostly wished to discuss football, not legal philosophies; at one point, he turned down future Justice Samuel Alito for a clerkship. He retired in 1993, during Bill Clinton's presidency, saying that "someone else should be permitted to have a like experience." Clinton appointed Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, a judge from the Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit and a former Columbia University law professor, to succeed him.

Later years and death

Later years and death After retiring from the Supreme Court, White occasionally sat with lower federal courts. He maintained chambers in the federal courthouse in Denver until shortly before his death. He also served for the Commission on Structural Alternatives for the Federal Courts of Appeals.

White died on April 15, 2002 at the age of 84. He was the last living Warren Court Justice, and died the day before the fortieth anniversary of his swearing in as a Justice. From his death until the retirement of Sandra Day O'Connor, there were no living former Justices.

His remains are interred at All Souls Walk at the St. John's Cathedral in Denver.

Then-Chief Justice Rehnquist said White "came as close as anyone I have known to meriting Matthew Arnold's description of Sophocles: 'He saw life steadily and he saw it whole.' All of us who served with him will miss him."

Awards and honors

The NFL Players Association gives the Byron "Whizzer" White award to one NFL player each year for his charity work. Michael McCrary, who was involved in Runyon v. McCrary, grew up to be a professional football player and won the Byron "Whizzer" White award in 2001.

The federal courthouse in Denver that houses the Tenth Circuit is named after White.

White was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2003 by President George W. Bush.

White was inducted into the Rocky Mountain Athletic Conference Hall of Fame on July 14, 2007, in addition to being a member of the College Football Hall of Fame.

One of White's former law clerks, Dennis J. Hutchinson, wrote an unofficial biography of him called The Man Who Once was Whizzer White.

by

by

Dennis Hutchinson

Dennis Hutchinsonsource for posts 2, 3, and 4: wikipedia

and how can you not love someone whose nickname is Whizzer? lots of reasons to like this Justice, but that is one of the fun ones.

and how can you not love someone whose nickname is Whizzer? lots of reasons to like this Justice, but that is one of the fun ones.

Byron White and the Supreme Court

Byron White and the Supreme CourtUniversity of Chicago Law Professor Dennis Hutchinson talked about the life of Associate Justice Byron White. Justice White served on the U.S. Supreme Court for 31 years, but before his appointment in 1962 he was a college and professional football player earning a great deal of national media attention in the early twentieth century. Mr. Hutchinson looked at how Byron White’s early celebrity shaped his career on the Court.

“Byron White & the Supreme Court: We Learned That in Wellington” was part of the History Colorado 2011-2012 lecture series, held at the Scottish Rite Masonic Center in Denver.

http://www.c-span.org/video/?301742-1...

Dissent from Roe v. Wade and Doe v. Bolton and their Progeny

Dissent from Roe v. Wade and Doe v. Bolton and their ProgenyByron White was appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court as Associate Justice in 1962, and served on the Court until he retired in 1993. He died in 2002. Justice White wrote a widely quoted dissent in Doe v. Bolton, in which Justice Rehnquist concurred.

The Abortion Decisions: "An exercise of raw judicial power"

A prominent critic of Roe v. Wade and Doe v. Bolton, Justice White not only dissented from the 1973 decisions but later made repeated attempts to overrule them. According to his biographer, White's personal views on abortion seem to have been ambivalent. [1] On the other hand, his Roe dissent suggests that he was alarmed by the Court's disregard for the life of the unborn. "The Court, for the most part, sustains this position: during the period prior to the time the fetus becomes viable, the Constitution of the United States values the convenience, whim, or caprice of the putative mother more than the life or potential life of the fetus . . ."[2]

Whatever his own opinions on abortion may have been, there is no doubt that he regarded the Court's action as entirely unjustifiable from a legal perspective:

I find nothing in the language or history of the Constitution to support the Court's judgment. The Court simply fashions and announces a new constitutional right for pregnant mothers [410 U.S. 222] and, with scarcely any reason or authority for its action, invests that right with sufficient substance to override most existing state abortion statutes. . . . As an exercise of raw judicial power, the Court perhaps has authority to do what it does today; but, in my view, its judgment is an improvident and extravagant exercise of the power of judicial review that the Constitution extends to this Court.[3]

On the Constitutional Foundations of Roe and Doe: "There, nothing"

This was a view he adhered to throughout his time on the Court. He later told a friend that Roe was the only illegitimate decision the Court had made during his tenure: "In every other case, there was something in the Constitution you could point to for support. There, nothing."[4] White dissented in many other cases, of course, but Roe clearly stood out in his mind as completely unjustifiable. Nearly twenty years later, in Planned Parenthood v. Casey, he voted to overturn Roe despite the fact that the decision was by then a long-standing precedent. This was an unusual move: White, like nearly all judges, tended to defer to decisions eventually even if he had initially disagreed with them. The fact that he made an exception with regard to Roe shows how strongly he objected to the Court's verdict in that case. His biographer makes note of this fact: "Unlike all other areas, in which several years of reaffirmation settled doctrine and dictated his acceptance of a line of authority even where he had dissented at first, abortion was an exception. An illegitimate decision was entitled to no respect."[5]

The Dissent in Thornburgh: Overturn Roe-Return the Issue to the People

This is borne out by White's dissent in Thornburgh v. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, written thirteen years after (1986). In this decision, in an opinion authored by Justice Harry Blackmun, the Court struck down various state abortion regulations, reiterating Roe's claim that abortion is a fundamental constitutional right.

In his dissent White acknowledges the importance of stare decisis: the principle that the Court should uphold its prior decisions for the sake of the law's consistency and integrity. "[W]hen governing legal standards are open to revision in every case, deciding cases becomes a mere exercise of judicial will, with arbitrary and unpredictable results." Stare decisis is thus essential to the judicial process.

It is also essential, however, that the Court retain an ability to set aside prior decisions in certain circumstances: specifically, when a prior decision has overturned laws that represent the will of the people, and has overturned these laws by finding principles in the Constitution that are not there:

[D]ecisions that find in the Constitution principles or values that cannot fairly be read into that document usurp the people's authority, for such decisions represent choices that the people have never made, and that they cannot disavow through corrective legislation. For this reason it is essential that this Court maintain the power to restore authority to its proper possessors by correcting constitutional decisions that, on consideration, are found to be mistaken.

White then cites examples in which the Court had overruled its prior decisions, despite stare decisis concerns. History has shown, moreover, that the Court was right to do so; and even Blackmun had recently acknowledged the necessity of overruling bad decisions that "depart from a proper understanding of the Constitution."

"In my view," says White, "the time has come to recognize that Roe v. Wade, no less than the cases overruled by the Court in the decisions I have just cited, 'departs from a proper understanding of the Constitution,' and to overrule it." White argues this by first noting that there is clearly nothing in the text of the Constitution itself that refers to abortion or even to reproduction generally speaking; moreover, it is "highly doubtful" that the Constitution's authors intended to protect a right to abortion. In Roe the Court had acknowledged as much, but claimed that the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment (which forbids the deprivation of life, liberty or property without due process of the law) protected individuals from state laws that infringed on their liberties in certain circumstances. It ruled that abortion was a fundamental liberty that states could not restrict without a compelling interest.

White finds this ruling flawed. While individual liberty is indeed protected under the Due Process Clause, this protection is generally very limited: state laws can usually restrict liberty as long as they are rational. [For instance, my liberty to drive on the left side of the road is restricted by state laws across the nation; these traffic laws certainly do not violate the Due Process Clause.] Only when fundamental rights are at issue is a stricter standard applied: states may not infringe on fundamental rights without a truly compelling reason. In White's opinion, contrary to the Court's in Roe, the liberty to abort is not fundamental; therefore states can restrict abortion.

The question, of course, is how to distinguish a "fundamental" right or liberty from a "non-fundamental" one. White notes that rights found explicitly in the Constitution are clearly fundamental; in protecting these rights against intrusive state laws the Court is on firm ground. However,

[w]hen the Court ventures further and defines as "fundamental" liberties that are nowhere mentioned in the Constitution . . . it must, of necessity, act with more caution, lest it open itself to the accusation that, in the name of identifying constitutional principles to which the people have consented in framing their Constitution, the Court has done nothing more than impose its own value upon the people.

In order to protect against this possibility, the Court in the past has classed as fundamental only those rights that are "implicit in the concept of ordered liberty" such that liberty could not exist without them. At other times the Court has claimed that rights "deeply rooted in the nation's history and tradition" should also be considered fundamental. These approaches allowed the Court to go beyond the text of the Constitution to protect unenumerated rights, but placed limits on how far this process could be taken.

Neither of these approaches justify Roe, says White. It is clear, even from the Court's own opinion in Roe, that abortion is not "deeply rooted in our nation's history and tradition." Nor is abortion "implicit in the concept of ordered liberty:" a free and democratic society does not presuppose any particular set of rules regarding abortion.

And again, the fact that many men and women of good will and high commitment to constitutional government place themselves on both sides of the abortion controversy strengthens my own conviction that the values animating the Constitution do not compel recognition of the abortion liberty as fundamental. In so denominating that liberty, the Court engages not in constitutional interpretation, but in the unrestrained imposition of its own extraconstitutional value preferences.

The Court made another serious error in Roe as well, says White: it not only claimed that abortion was a fundamental right, but also claimed that the state's interest in protecting unborn life was not "compelling" until viability, and therefore ruled that states could not restrict abortion until after viability. White finds the distinction between pre- and post-viability irrelevant: the state's interest in protecting life arises from its desire to protect those who will be citizens if they are not killed in the womb. This interest is equally substantial whether the fetus is viable or not.

White concludes that the abortion issue should be returned to the states and the people themselves:

Abortion is a hotly contested moral and political issue. Such issues, in our society, are to be resolved by the will of the people, either as expressed through legislation or through the general principles they have already incorporated into the Constitution they have adopted. Roe v. Wade implies that the people have already resolved the debate by weaving into the Constitution the values and principles that answer the issue. As I have argued, I believe it is clear that the people have never-not in 1787, 1791, 1868, or at any time since-done any such thing. I would return the issue to the people by overruling Roe v. Wade.

Source: EndRoe.org

Parcells: A Football Life

Parcells: A Football Life by Bill Parcells (no photo)

by Bill Parcells (no photo)Synopsis:

After his pivotal 2013 induction into the Pro Football Hall of Fame, iconoclastic and Super Bowl-winning coach Bill Parcells finally reveals his life story and 50 storied years of football. Widely acclaimed sports writer Nunyo Demasio touches on some of the biggest NFL franchises in history, including the New York Giants, New England Patriots, New York Jets, and Dallas Cowboys.

Bill Parcells may be the most iconic football coach of our time. During his decades-long tenure as an NFL coach, he turned failing franchises into contenders. He led the ailing New York Giants to two Super Bowl victories, turned the New England Patriots from a team best known for their drug scandals into an NFL powerhouse, reinvigorated the New York Jets, brought the Dallas Cowboys back to life, and was most recently enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame. He changed the way the game was played, reimagining his teams with ferocious defenses and smashmouth offenses that spawned such great players as Hall of Famers Lawrence Taylor and Curtis Martin. Beloved and controversial but always respected, this is a rare inside look at one of football's greatest minds at the most reflective time in his career.

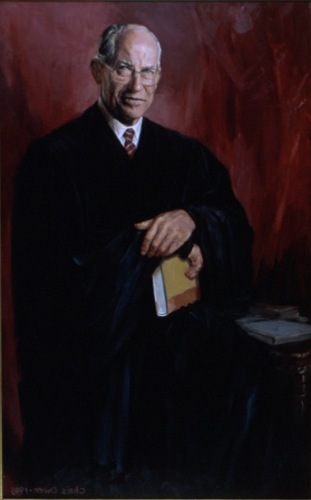

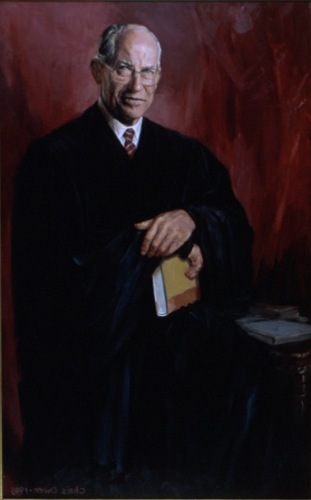

Byron R. White

Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court April 16, 1962 - June 28, 1993

The Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States (Artist: Chris Owen)

Byron White—an unmoving pragmatist—lives in infamy for both his individualistic approach to law and his success as a professional athlete. Hailing from the small town of Fort Collins, Colorado, White was born on June 8, 1917 to Alpha Albert White and Maude Elizabeth Burger. While his beginnings were modest and his parents did not complete high school, White nevertheless excelled as a scholar and athlete. He graduated valedictorian of his high school and earned an athletic scholarship for football to the University of Colorado at Boulder.

At Colorado, White played collegiate football as a halfback. He earned All-American decorations and received the nickname “Whizzer,” which followed him for the rest of his life. White won a Rhodes Scholarship to study medicine the University of Oxford upon graduating, but deferred for a year in order to play professional football. He was selected in Round 1 of the 1938 NFL draft by the Pittsburgh Pirates (now the Pittsburgh Steelers). He played only one season, but led the entire league in rushing yards as a rookie and earned the highest salary in the sport at the time. After leaving the NFL, White traveled to England to complete his Rhodes scholarship at Oxford’s Hertford College in 1939, but soon returned to the States when World War II began. Upon his return, White entered Yale Law School, obtaining the highest grades in his class the first year. In a move unthinkable by today’s standards, White took a leave of absence from law school to play the 1940-1941 football seasons with the Detroit Lions. His legal education remained unfinished when he entered the U.S. Navy in 1942. While there, White served as an intelligence officer, where he met future president John F. Kennedy and befriended future justice John Paul Stevens. After the war ended, White finally earned his law degree from Yale in 1946.

White’s legal career began when he moved to Washington, D.C. to work as a law clerk. He clerked for U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice Fred Vinson until 1947, when he joined a Denver law firm and worked in private practice for the next fourteen years. In 1960, John F. Kennedy, now running for president, asked White for help in promoting his campaign. White used his celebrity clout to demonstrably publicize Kennedy in Colorado before Robert Kennedy gave him the reins of the national Citizens of Kennedy organization. Upon election, John F. Kennedy named White as the U.S. Deputy Attorney General, the second-highest position in the Justice Department under Robert Kennedy. In this capacity, White managed the daily administration of the department, took an active role in representing departmental initiatives to Congress, and was integral to the selection process for federal judiciary nominees. President Kennedy then selected White as his nominee to replace the retiring Associate Justice Charles E. Whittaker in March 1962. Although initially apprehensive, he agreed and was quickly confirmed by the Senate. White took his seat as Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court on April 16, 1962.

Byron White is not easily categorized by ideology. Scholars continue to debate his ideological posture because his demeanor during oral arguments, prose in written opinions, and voting record are each driven by the individual circumstances of the case. Rather than make sweeping legal conclusions about constitutional doctrine, he approached cases by examining their facts and implementing a pragmatic approach towards interpreting the law. White wrote a total of nearly one thousand opinions during his 31 years of service and is remembered for his stern interrogation of attorneys during arguments. What is known for certain is that he believed in a strong federal government, a U.S. Supreme Court deferential to the other branches, and government accountability. These ideas are perhaps best illustrated in his ardent support of expansion of governmental powers, writing several majority opinions to desegregate public schools, such as U.S. v. Fordice in 1992, and uphold affirmative action policies, as in Fullilove v. Klutznick in 1980. Nevertheless, his voting record fell more in line with the conservative bloc as the years passed. He wrote majority opinions to reduce the power of federal civil rights laws, to uphold state laws prohibiting homosexual sex between consenting adults, and opposed state and local affirmative action plans. He similarly dissented from the majority in Miranda v. Arizona and Roe v. Wade. A vocal critic of the substantive due process doctrine for the entirety of his career, White retired from the Court on June 28, 1993 and was succeeded by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. He served on the Commission on Structural Alternatives for the Federal Courts of Appeals while occasionally sitting on lower federal courts in Colorado until his passing at age 84.

Other:

C-Span American History TV - Uploaded on October 9, 2011

Byron White served on the Supreme Court for 31 years, but before his appointment in 1962 he was a college and professional football player earning a great deal of national media attention. University of Chicago Law Professor Dennis Hutchinson looks at how Byron White's early celebrity shaped his career on the Court.

Links:

https://www.oyez.org/justices/byron_r...

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jlKGO...

Discussion Topics:

a) Discuss why University of Chicago Law Professor Dennis Hutchinson feels that Justice White's early celebrity shaped his thirty-one years on the U.S. Supreme Court.

b) Discuss why scholars continue to debate the ideology demonstrated during the career of Justice White on the United States Supreme Court.

Source(s): Oyez, C-Span American History TV (You-Tube)

Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court April 16, 1962 - June 28, 1993

The Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States (Artist: Chris Owen)

Byron White—an unmoving pragmatist—lives in infamy for both his individualistic approach to law and his success as a professional athlete. Hailing from the small town of Fort Collins, Colorado, White was born on June 8, 1917 to Alpha Albert White and Maude Elizabeth Burger. While his beginnings were modest and his parents did not complete high school, White nevertheless excelled as a scholar and athlete. He graduated valedictorian of his high school and earned an athletic scholarship for football to the University of Colorado at Boulder.

At Colorado, White played collegiate football as a halfback. He earned All-American decorations and received the nickname “Whizzer,” which followed him for the rest of his life. White won a Rhodes Scholarship to study medicine the University of Oxford upon graduating, but deferred for a year in order to play professional football. He was selected in Round 1 of the 1938 NFL draft by the Pittsburgh Pirates (now the Pittsburgh Steelers). He played only one season, but led the entire league in rushing yards as a rookie and earned the highest salary in the sport at the time. After leaving the NFL, White traveled to England to complete his Rhodes scholarship at Oxford’s Hertford College in 1939, but soon returned to the States when World War II began. Upon his return, White entered Yale Law School, obtaining the highest grades in his class the first year. In a move unthinkable by today’s standards, White took a leave of absence from law school to play the 1940-1941 football seasons with the Detroit Lions. His legal education remained unfinished when he entered the U.S. Navy in 1942. While there, White served as an intelligence officer, where he met future president John F. Kennedy and befriended future justice John Paul Stevens. After the war ended, White finally earned his law degree from Yale in 1946.

White’s legal career began when he moved to Washington, D.C. to work as a law clerk. He clerked for U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice Fred Vinson until 1947, when he joined a Denver law firm and worked in private practice for the next fourteen years. In 1960, John F. Kennedy, now running for president, asked White for help in promoting his campaign. White used his celebrity clout to demonstrably publicize Kennedy in Colorado before Robert Kennedy gave him the reins of the national Citizens of Kennedy organization. Upon election, John F. Kennedy named White as the U.S. Deputy Attorney General, the second-highest position in the Justice Department under Robert Kennedy. In this capacity, White managed the daily administration of the department, took an active role in representing departmental initiatives to Congress, and was integral to the selection process for federal judiciary nominees. President Kennedy then selected White as his nominee to replace the retiring Associate Justice Charles E. Whittaker in March 1962. Although initially apprehensive, he agreed and was quickly confirmed by the Senate. White took his seat as Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court on April 16, 1962.

Byron White is not easily categorized by ideology. Scholars continue to debate his ideological posture because his demeanor during oral arguments, prose in written opinions, and voting record are each driven by the individual circumstances of the case. Rather than make sweeping legal conclusions about constitutional doctrine, he approached cases by examining their facts and implementing a pragmatic approach towards interpreting the law. White wrote a total of nearly one thousand opinions during his 31 years of service and is remembered for his stern interrogation of attorneys during arguments. What is known for certain is that he believed in a strong federal government, a U.S. Supreme Court deferential to the other branches, and government accountability. These ideas are perhaps best illustrated in his ardent support of expansion of governmental powers, writing several majority opinions to desegregate public schools, such as U.S. v. Fordice in 1992, and uphold affirmative action policies, as in Fullilove v. Klutznick in 1980. Nevertheless, his voting record fell more in line with the conservative bloc as the years passed. He wrote majority opinions to reduce the power of federal civil rights laws, to uphold state laws prohibiting homosexual sex between consenting adults, and opposed state and local affirmative action plans. He similarly dissented from the majority in Miranda v. Arizona and Roe v. Wade. A vocal critic of the substantive due process doctrine for the entirety of his career, White retired from the Court on June 28, 1993 and was succeeded by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. He served on the Commission on Structural Alternatives for the Federal Courts of Appeals while occasionally sitting on lower federal courts in Colorado until his passing at age 84.

Other:

C-Span American History TV - Uploaded on October 9, 2011

Byron White served on the Supreme Court for 31 years, but before his appointment in 1962 he was a college and professional football player earning a great deal of national media attention. University of Chicago Law Professor Dennis Hutchinson looks at how Byron White's early celebrity shaped his career on the Court.

Links:

https://www.oyez.org/justices/byron_r...

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jlKGO...

Discussion Topics:

a) Discuss why University of Chicago Law Professor Dennis Hutchinson feels that Justice White's early celebrity shaped his thirty-one years on the U.S. Supreme Court.

b) Discuss why scholars continue to debate the ideology demonstrated during the career of Justice White on the United States Supreme Court.

Source(s): Oyez, C-Span American History TV (You-Tube)

The Greatest Supreme Court Justice

By LUKE VOYLES November 3, 2017

Justice Byron White does not have an excellent reputation among legal scholars or among the general public. Conservatives do not usually remember White too fondly because of his liberal rulings, and he is usually not particularly beloved by liberals because of his conservative rulings. When noted Yale law professor Robert M. Cover wrote his famous New York Times article comparing Supreme Court justices to professional baseball players, he compared White to Jackie Jensen. Cover explained that both Jensen and White were “better as running backs” (White was a noted running back at the University of Colorado in the 1930s). He also found that White was completely overwhelmed by the towering presences in the Earl Warren Court, but that White became more powerful in the Warren Burger Court. Oyez.org was even more scathing in its view of Justice White, calling him “an unmoving pragmatist-lives in infamy both for his individualistic approach to law and his success as a profession athlete.”

As the title might give away, I completely disagree with these views on White. I believe that White was a magnificent centrist dedicated to a more equal United Sates, and he was also suspicious of governmental overreach. His life and career were unorthodox for a Supreme Court justice. Born in 1917, he played professional football for one year for the Pittsburgh Steelers and went into the army as an intelligence officer. He wrote the report on the sinking of the PT-109, onboard which was the man who would appoint him to the Supreme Court in 1962: John F. Kennedy. White served as the assistant attorney general under Kennedy and helped protect both Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Freedom Riders in Mississippi. As a Supreme Court justice, legal scholars had no reason to question White’s credentials on the liberal Earl Warren Court as he was an appointee of John Kennedy.

At first, White did not seem to deviate too much from Chief Justice Warren. White joined the majority in Abingdon School District v. Schempp (1963). He wrote the majority opinion of McLaughlin v. Florida in 1964, which partially overruled Pace v. Alabama (1883). McLaughlin allowed two people of two different ethnicities to live together. It would take three more years for Pace to be completely overturned in Loving v. Virginia (1967), a case where White joined a unanimous court. He helped the Court incorporate the right of a trial by jury guaranteed by the Sixth Amendment of the Constitution to the state level in his majority opinion for Duncan v. Louisiana (1968). Even after Warren Burger replace Earl Warren as chief justice in 1969, White continued to support liberal causes. In 1972, White concurred with the 5-4 ruling that determined that the death penalty laws of the United States were too arbitrary in Furman v. Georgia. He wrote for the majority in banning the death penalty for people only guilty of rape in Coker v. Georgia (1977), a landmark ruling in Eighth Amendment jurisprudence. White also spoke for the majority of justices in Duren v. Missouri (1979), when he explained that it was discrimination for juries to not require women selected for jury duty to serve that duty.

At first, White did not seem to deviate too much from Chief Justice Warren. White joined the majority in Abingdon School District v. Schempp (1963). He wrote the majority opinion of McLaughlin v. Florida in 1964, which partially overruled Pace v. Alabama (1883). McLaughlin allowed two people of two different ethnicities to live together. It would take three more years for Pace to be completely overturned in Loving v. Virginia (1967), a case where White joined a unanimous court. He helped the Court incorporate the right of a trial by jury guaranteed by the Sixth Amendment of the Constitution to the state level in his majority opinion for Duncan v. Louisiana (1968). Even after Warren Burger replace Earl Warren as chief justice in 1969, White continued to support liberal causes. In 1972, White concurred with the 5-4 ruling that determined that the death penalty laws of the United States were too arbitrary in Furman v. Georgia. He wrote for the majority in banning the death penalty for people only guilty of rape in Coker v. Georgia (1977), a landmark ruling in Eighth Amendment jurisprudence. White also spoke for the majority of justices in Duren v. Missouri (1979), when he explained that it was discrimination for juries to not require women selected for jury duty to serve that duty.

As the 1970s progressed, White revealed himself to be quite the conservative in certain issues. For context, the one dissenter in Duren was Justice William Rehnquist, who joined the court in 1971. While White continued to hold the center-right of the Court, he frequently began joining with Rehnquist against many other members of the court. In 1973, they were the sole dissenters in Roe v. Wade. White also joined Rehnquist in supporting Congress’s power to expel non-citizens for no reason whatsoever in Immigration and Naturalization Service v. Chadha (1983). It was also during his time on the Burger Court that White made his great blunder as a writer of a majority opinion in Bowers v. Hardwick (1986). White was incorrect both in his conclusion and in his methodology. Justice Sandra Day O’Connor joined White’s opinion, but would explain in her concurrence in Lawrence v. Texas (2003) why she agreed with White. O’Connor believed that states had the right to ban certain sexual acts (i.e., sodomy) for both sexes. However, O’Connor concurred in Lawrence because the Texas law under question only banned homosexual sodomy, which she considered to be gender discrimination and therefore, unconstitutional. White did not take that road out, and specifically allowed such a ban as a bar on homosexual activities.

Read the remainder of the article at: http://www.wupr.org/2017/11/03/the-gr...

Other:

by

by

Dennis J. Hutchinson

Dennis J. HutchinsonSource: Washington University Political Review

Gorsuch elaborates on his ‘childhood hero,’ Justice Byron White

By MARK BERMAN March 21, 2017

The U.S. Supreme Court in 1988. In the front row, White is second from right. (Bob Daugherty/AP)

During his confirmation hearings, Gorsuch has repeatedly invoked a Supreme Court justice who also hailed from Colorado. Justice Byron White, who was nominated by President John F. Kennedy, spent three decades on the bench before retiring in 1993. White, who was also a running back who twice led the NFL in rushing, died in 2002.

Gorsuch clerked for White, and speaking on Tuesday afternoon, credited the late justice with teaching him how to be a judge.

“He really was my childhood hero,” Gorsuch said in response to a question from Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Tex.), who praised White while asking it. “And to actually get picked out of the pile to spend the year with him … remains the privilege of a lifetime. And it has everything to do with why I’m here. I wouldn’t have become a judge but for watching his example and the humility with which he approached the job.”

White was one of two justices — along with William H. Rehnquist, who would later serve as chief justice — who dissented from Roe v. Wade in 1973. That landmark abortion rights ruling came up early in Gorsuch’s hearing, because President Trump, who nominated Gorsuch, vowed to have Roe overturned, though Gorsuch said he made no promises or commitments before being nominated.

When asked if Trump had brought up overturning the 1973 decision, Gorsuch replied earlier Tuesday that if he had, “I would have walked out the door.”

(Another White tidbit: A few years back, the late justice emerged as a bit of a lightning rod during the Democratic presidential primary. Former New Mexico governor Bill Richardson drew some criticism from liberal activists when he named White as a model justice, saying later that he named him because he “figured if Kennedy had supported him,” he couldn’t have been that bad.)

Link to article: https://www.washingtonpost.com/politi...

Other:

by

by

Dennis J. Hutchinson

Dennis J. Hutchinson

Source: The Washington Post

By MARK BERMAN March 21, 2017

The U.S. Supreme Court in 1988. In the front row, White is second from right. (Bob Daugherty/AP)

During his confirmation hearings, Gorsuch has repeatedly invoked a Supreme Court justice who also hailed from Colorado. Justice Byron White, who was nominated by President John F. Kennedy, spent three decades on the bench before retiring in 1993. White, who was also a running back who twice led the NFL in rushing, died in 2002.

Gorsuch clerked for White, and speaking on Tuesday afternoon, credited the late justice with teaching him how to be a judge.

“He really was my childhood hero,” Gorsuch said in response to a question from Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Tex.), who praised White while asking it. “And to actually get picked out of the pile to spend the year with him … remains the privilege of a lifetime. And it has everything to do with why I’m here. I wouldn’t have become a judge but for watching his example and the humility with which he approached the job.”

White was one of two justices — along with William H. Rehnquist, who would later serve as chief justice — who dissented from Roe v. Wade in 1973. That landmark abortion rights ruling came up early in Gorsuch’s hearing, because President Trump, who nominated Gorsuch, vowed to have Roe overturned, though Gorsuch said he made no promises or commitments before being nominated.

When asked if Trump had brought up overturning the 1973 decision, Gorsuch replied earlier Tuesday that if he had, “I would have walked out the door.”

(Another White tidbit: A few years back, the late justice emerged as a bit of a lightning rod during the Democratic presidential primary. Former New Mexico governor Bill Richardson drew some criticism from liberal activists when he named White as a model justice, saying later that he named him because he “figured if Kennedy had supported him,” he couldn’t have been that bad.)

Link to article: https://www.washingtonpost.com/politi...

Other:

by

by

Dennis J. Hutchinson

Dennis J. HutchinsonSource: The Washington Post

The Unjustly Forgotten Legacy of Byron White

By FRANK SCATURRO March 30, 2017

Byron White, shown here in 1991, second farthest to the right next to Justice Kennedy (Reuters: File Photo)

The judiciary would enjoy a better reputation today if more judges emulated his restraint.

In a nomination hearing that otherwise proceeded as expected, Judge Neil Gorsuch may have surprised Supreme Court watchers by calling Justice Byron White, a fellow Coloradan for whom he had clerked, his “childhood hero” and “one of the greats.” Noting White’s modesty, Gorsuch poignantly recalled his observation that “the truth is we’ll all be forgotten soon enough, me included.” His words would prove too true too soon.

White died on April 15, 2002. His 31 years on the Court, the fourth-longest tenure of the 20th century, followed a storybook journey from NFL star to World War II hero to deputy attorney general. Yet there was little press fanfare upon his death. Even the passing of the actor Robert Urich the following day received more coverage.

Perhaps not coincidentally, the politicization of the federal judiciary hit a new low in 2002. Prior years had demonstrated the infectious influence of politics on the selection of Supreme Court justices, but by the time White died, the same phenomenon was afflicting the nominations of judges to the lower federal appeals courts to an unprecedented degree. Democratic senators, taking their cues from left-wing interest groups, were holding up such lower-court nominees and setting the stage for their wholesale filibuster in 2003.

Although a Democrat, John F. Kennedy, nominated him, there can be little doubt that someone with White’s views would be subjected to the same treatment from his own party today. White came from an age when judges were celebrated for showing a certain deference to the judgments of democratically elected officials. An unelected, life-tenured judge, the thinking went, should be hesitant to impose his own personal views in striking down laws passed by the people’s representatives. White understood this, once remarking that “judges have an exaggerated view of their role in our polity.”

At the same time, the Constitution contained powerful guarantees of civil rights ratified shortly after the Civil War, guarantees that had been disregarded for many years as the Supreme Court allowed Jim Crow to sweep the old Confederacy. Here, the posture of restraint was not in order, and White was well positioned to know it. As deputy attorney general in the Kennedy Justice Department, he confronted racial segregation directly and personally intervened in Alabama to protect the Freedom Riders. On nominating him to the Court, President Kennedy called White the “ideal New Frontier justice.”

The combination of judicial restraint and a willingness to protect the long-neglected civil rights of African Americans would characterize White’s years on the Court. At the time of his appointment, such champions of judicial restraint as Felix Frankfurter and John Marshall Harlan II were still on the Court, which had recently and unanimously rejected state-sponsored segregation. White would long outlast those early colleagues and remarkably stuck to his principles even as other trends transformed the Court’s role.

Criminal law was one area the Warren Court had to revolutionize without White’s help. White wrote a powerful dissent from the majority’s decision in Miranda v. Arizona (1966), arguing, as he would in later criminal-law opinions, against treating law enforcement with too much distrust: “More than the human dignity of the accused is involved; the human personality of others in the society must also be preserved. Thus the values reflected by the privilege [against self-incrimination] are not the sole desideratum; society’s interest in the general security is of equal weight.” Nonetheless, part of White’s restraint entailed later deferring to the precedent that established the now-familiar Miranda warnings after society had come to rely on them.

Link to remainder of article: https://www.nationalreview.com/2017/0...

Other:

by Robert Dittmer (no photo)

by Robert Dittmer (no photo)

Source: National Review

By FRANK SCATURRO March 30, 2017

Byron White, shown here in 1991, second farthest to the right next to Justice Kennedy (Reuters: File Photo)

The judiciary would enjoy a better reputation today if more judges emulated his restraint.

In a nomination hearing that otherwise proceeded as expected, Judge Neil Gorsuch may have surprised Supreme Court watchers by calling Justice Byron White, a fellow Coloradan for whom he had clerked, his “childhood hero” and “one of the greats.” Noting White’s modesty, Gorsuch poignantly recalled his observation that “the truth is we’ll all be forgotten soon enough, me included.” His words would prove too true too soon.

White died on April 15, 2002. His 31 years on the Court, the fourth-longest tenure of the 20th century, followed a storybook journey from NFL star to World War II hero to deputy attorney general. Yet there was little press fanfare upon his death. Even the passing of the actor Robert Urich the following day received more coverage.

Perhaps not coincidentally, the politicization of the federal judiciary hit a new low in 2002. Prior years had demonstrated the infectious influence of politics on the selection of Supreme Court justices, but by the time White died, the same phenomenon was afflicting the nominations of judges to the lower federal appeals courts to an unprecedented degree. Democratic senators, taking their cues from left-wing interest groups, were holding up such lower-court nominees and setting the stage for their wholesale filibuster in 2003.

Although a Democrat, John F. Kennedy, nominated him, there can be little doubt that someone with White’s views would be subjected to the same treatment from his own party today. White came from an age when judges were celebrated for showing a certain deference to the judgments of democratically elected officials. An unelected, life-tenured judge, the thinking went, should be hesitant to impose his own personal views in striking down laws passed by the people’s representatives. White understood this, once remarking that “judges have an exaggerated view of their role in our polity.”

At the same time, the Constitution contained powerful guarantees of civil rights ratified shortly after the Civil War, guarantees that had been disregarded for many years as the Supreme Court allowed Jim Crow to sweep the old Confederacy. Here, the posture of restraint was not in order, and White was well positioned to know it. As deputy attorney general in the Kennedy Justice Department, he confronted racial segregation directly and personally intervened in Alabama to protect the Freedom Riders. On nominating him to the Court, President Kennedy called White the “ideal New Frontier justice.”

The combination of judicial restraint and a willingness to protect the long-neglected civil rights of African Americans would characterize White’s years on the Court. At the time of his appointment, such champions of judicial restraint as Felix Frankfurter and John Marshall Harlan II were still on the Court, which had recently and unanimously rejected state-sponsored segregation. White would long outlast those early colleagues and remarkably stuck to his principles even as other trends transformed the Court’s role.

Criminal law was one area the Warren Court had to revolutionize without White’s help. White wrote a powerful dissent from the majority’s decision in Miranda v. Arizona (1966), arguing, as he would in later criminal-law opinions, against treating law enforcement with too much distrust: “More than the human dignity of the accused is involved; the human personality of others in the society must also be preserved. Thus the values reflected by the privilege [against self-incrimination] are not the sole desideratum; society’s interest in the general security is of equal weight.” Nonetheless, part of White’s restraint entailed later deferring to the precedent that established the now-familiar Miranda warnings after society had come to rely on them.

Link to remainder of article: https://www.nationalreview.com/2017/0...

Other:

by Robert Dittmer (no photo)

by Robert Dittmer (no photo)Source: National Review

Books mentioned in this topic

Justice Byron White Decisions (other topics)The Man Who Once Was Whizzer White: A Portrait Of Justice Byron R White (other topics)

The Man Who Once Was Whizzer White: A Portrait Of Justice Byron R White (other topics)

Parcells: A Football Life (other topics)

The Man Who Once Was Whizzer White: A Portrait Of Justice Byron R White (other topics)

More...

Authors mentioned in this topic

Robert Dittmer (other topics)Dennis J. Hutchinson (other topics)

Dennis J. Hutchinson (other topics)

Bill Parcells (other topics)

Dennis J. Hutchinson (other topics)

More...

Biography

Byron White was born and raised in Colorado. He attended the University of Colorado on a scholarship. He graduated first in his class and held varsity letters in football, basketball, and baseball. "Whizzer" White played professional football for a year with the Pittsburgh Pirates football team.

White won a Rhodes Scholarship to Oxford, and then returned to the United States to complete a law degree at Yale. He combined his law classes with football, playing for the Detroit Lions. Upon graduation from Yale, White clerked for Chief Justice Fred Vinson. Thereafter, White returned to Colorado and engaged in private law practice.

White organized the Colorado presidential campaign for John F. Kennedy. Kennedy appointed White deputy attorney general in 1961. A year later, Kennedy selected White for a position on the Supreme Court.

White acquired a reputation for moderation during the heyday of Warren Court liberalism and egalitarianism. Though the membership of the Court has shifted in White's direction, he has not managed to articulate a comprehensive philosophy and lead his fellow justices.

Personal Information

Born Friday, June 8, 1917

Died Monday, April 15, 2002

Childhood Location Colorado

Childhood Surroundings Colorado

Religion Episcopalian

Ethnicity English

Father Alpha A. White

Father's Occupation Lumber company manager

Mother Maude Burger

Family Status Middle

Position Associate Justice

Seat 7

Nominated By Kennedy

Commissioned on Wednesday, April 11, 1962

Sworn In Sunday, April 15, 1962

Left Office Sunday, June 27, 1993

Reason For Leaving Retired

Length of Service 31 years, 2 months, 12 days

Home Colorado

source: The Oyez Project at IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. 01 April 2012. .