Beatrix Campbell's Blog

October 29, 2025

The Thick of It

When the Prime Minister announced that West Midlands police were ���wrong��� to ban Maccabi Tel Aviv fans from attending the Aston Villa Europa Cup match on 6 November ���adding, ���We will not tolerate antisemitism on our streets,��� he was not only wrong, he was, forgive me for saying so, thick. Not a slur I like to use, but there are moments���

When his Culture, Media and Sport Secretary Lisa Nandy amplified the government���s case with the claim that the ban was unprecented, she was also wrong, and thick. And when Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson commented that the police and safety committee should explain the decision ��� as if it didn���t know, and as if it were not obvious ��� she was also wrong, and thick.

Everybody knew the reason: racist and sexist rampages. In any case the government had been briefed that the ban was being��considered��and why ��� there was a serious risk that Maccabi Tel Aviv fans would do what they do: make trouble.��

As they had done in Amsterdam and Athens in 2024 and generally on their home turf. And as they did on 19 October, the day after the Aston Villa ban had been announced: Tel Aviv police cancelled a match between rivals, Maccabi and Hapoel, after fans rioted before the game. Furthermore, they would be making racist trouble in one of Britain���s most ethnically-diverse cities.

There was nothing ���uprecedented��� or anti-semitic about the decision.

Across Europe, fans and their teams have been banned in the 2020s – the notoriously toxic rivalry between between Glasgow���s Rangers and Celtic fans resulted in both clubs banning each others��� fans from away matches. Eintracht Frankfurt fans were banned from Aberdeen in 2023 and Naples in 2025. Between 2022 and 2025 UEFA banned Russian teams entirely.

It is an eerie echo of the bad old days in 1980s English football: In 1985 English fans were banned after the European cup final between Liverpool and Juventus in Heysel stadium in Brussels: Liverpool supporters rushed at Juventus fans, a wall collapsed, 39 people were killed and over 600 injured. And that was before kick-off which ��� bizarrely went ahead. Nothing was more important than the game.

Heysel was not unusual ��� like many, the stadium was not fit for purpose; the police captain in charge was later convicted of manslaughter. The crash provoked the overhaul of football stadiums across Europe and reform of crowd safety management.

The disaster brought shame to English football ��� the Union of European Football Associations banned English clubs for five years.

Football violence could no longer be blamed on ���chavs��� or poor boys who knew no better. Riots were the sport of all sorts of men – men with Rolex watches, smart kit and enough money to travel. I���ve met men jailed for football hooliganism who were far from inarticulate ��� thick ��� thugs, they were eloquent about the pleasures of contempt and the productivity of violence.

Thinking about football violence got me writing with Adam Dawson, a dynastic Manchester United fan, about the culture of the ���beautiful game���, how for many boys it is about making masculinity, it dominates the seasons of their days, the obsession intrudes upon almost everything, their social lives, their conversations, their presence at parties, weddings, meal times; days before a game, excessive visceral excitement floods their bodies.

Hatreds flourish ��� a friend, a woman who holds a Newcastle United season ticket, whose passions are cooking and football, admits that when she encounters people from the rival Sunderland, ���I want to stab them���. It is as if a delectable curse shadows their passion.

Sir Keir Starmer���s family life has been dominated by his addiction to Arsenal, a club with a global fanbase. He says that being a ���massive fan��� is ���part of what I am.��� He says he loves the game and everything that goes with it, being with the guys and their sons, going to the pub, the excitement, the banter. Before he became Prime Minister, he says his staff ensured that the team���s fixtures are put into his diary, and he makes it to most of the home games.

There is, therefore, no excuse for his wilful ignorance – or indifference ��� about the risks Maccabi Tel Aviv fans could bring to Aston Villa. The Prime Minister���s criticism of West Midlands police and the city���s safety systems presumed anti-semitic bias and na��ve or inexperienced management of menacing football fans.

They were none of these things. The Prime Minister���s indifference to the Chief Constable���s authority and operational autonomy, should worry everyone about both this government���s competence and its authoritarianism. Seemingly, No 10 didn���t bother to consult Tel Aviv���s own experience trying to manage some Maccabi supporters��� relentless, violent racism and sexism.

The government���s intervention had nothing to do with football, or the behaviour of these fans and everything to do with Starmer���s adhesion to Israel.

Sky News��� eyewitness account of the attacks on the night described their attacks on Arabs, and Palestinians in particular.

Richard Sanders��� Double Down News takedown of Sky TV���s censorship and distortion of its own reporter���s eyewitness narrative should have caused Downing Street to pause. Universally reported as anti-semitic attacks on Maccabi fans, Sky News had broadcast a very different narrative. Its journalist used footage shot by Amsterdam photographer Annet de Graaf that showed the opposite: Maccabi fans, some of them hooded, running around attacking Dutch citizens.

But de Graaf���s footage was used and abused by international news organisations ��� a classic bit of ���totally dishonest��� obfuscation, says Sanders. De Graaf tried to engage international news organisations, to correct their version of events, but they wouldn���t.

De Graaf���s material had been used by Sky News journalist Alice Porter in her report. However, after broadcasting Porter���s story, Sky then traduced it by making Porter re-voice a re-edited version that ommitted the Maccabi fans��� culpability. Porter had been ‘clearly bullied‘ said Sanders.

Maccabi Tel Aviv fans��� violence in Athens in 2024 had been widely broadcast. These incidents are all part of a pattern: fans��� racist chants ���reach record levels��� in Israel���s 2024-2025 season – a 64 per cent increase, according to Kick It Out Israel.

Maccabi Tel Aviv fans are the worst, the Millwall of Israel ��� ���No one likes us. We don���t care. We are Millwall.��� It took years of assiduous effort to reform the brand and the reputation.

Kick it Out Israel accuses the Israel Football Association of systemic failure to confront pervasive racism and sexism among supporters and lack of ���meaningful enforcement ��� ���The club whose fans were recorded with the highest number of racist chants was Maccabi Tel Aviv.���

The Aston Villa ban should be a warning to the Israeli football authorities that their fans are not welcome not because they are Jews, but because in Birmingham, unlike Israel, their racist aggression will not be tolerated. And it should be a caution to No 10, too, that everyone, including the government, should share that responsibility.

As it happens, Aston Villa, West Midlands Police and the city���s emergency services are well used to trying to protect and prevent football fans��� menace and violence. Before the 2023 Warsaw Legia match against Aston Villa, for example, the notorious Polish fans��� ticket allocation was cut to 1000, on safety grounds.

Thousands of Polish fans arrived without tickets and enjoyed themselves not watching football but running rampage in the city. UEFA then fined the club ��100,000 and Legia Warsaw fans were banned from five future away games. So much for Lisa Nandy���s ���unprecedented��� allegation.

Ministers allowed themselves to be recruited to Starmer���s evident and ardent wish to defend Israel, the government dodged the opportunity to attack the racism, sexism and the cult of violence that still stick to football culture, and to address the larger context: how to make men participants in ��� rather than a threat to ��� pleasurable safe space

So, the ban remained. Maccabi Tel Aviv fans didn���t get to go to Aston Villa for the November fixture. The few Maccabi fans who made it were unhappily corralled into a nearby basketball park.��Villa fans would have been disappointed ��� their team won, but the absence of away teams��� fans always hollows out the space and the spirit.

But what was the alternative? The apparent reason for the ban on Maccabi Tel Aviv fans was their safety,����when everyone knew that the ban had been provoked by the history of their fans with enough money to travel and enough racist fury to fight their host communities. The ban saved them from themselves �����despite the protests of Starmer and his ministers, who didn���t have the grace or the political will to speak up for the people of Aston���s right to be safe.

October 19, 2025

Provocations and ���Picking Quarrels��� – Green Party Leaders Must Wise Up

Brighton���s Green MP Si��n Berry posted a strange message on X during the massive feminist gathering at the Brighton Centre on the sea front on 10 October:

I raised this with the Council, including the leader, months ago and offered my help to prevent all this. Very disappointing not to have had this taken up.

— Sian Berry (@sianberry) October 10, 2025

She was referring to the FiLiA Women���s Liberation Conference marking the 10th anniversary of a feminist conference in the city that, she had decided, was a ���clearly provocative��� event, and that she had tried (and failed) to persuade the council to ���prevent this���.

This was her response to the attack on the centre on the eve of Europe���s biggest feminist conference: it was to blame, the women were the provocateurs who, she suggested, had inflamed the masked-up faux militia, the trans cult Bash Back, to smash windows and spray-paint the conference centre���s walls.

Despite her best efforts, the council had refused to cancel. But it was, in a way, complicit ��� it had refused to pre-empt the attack and rejected FiLiA���s request for a Public Space Protection Order.

FiLiA had anticipated an assault. In August, Bash Back vandalised the constituency office of Health Secretary Wes Streeting allegedly for ���intending to erase trans people from public life.���

Berry���s complaint is an eerie echo of Article 293 of China���s Criminal Code prohibiting ���picking quarrels and provoking trouble.��� Among the many celebrated victims are the Feminist Five, known for their witty and sad public performances against violence against women and the lack of public toilet provision for women (they occupied a men���s toilet). Their fate went global after they were rounded up, arrested and imprisoned in 2015 for planning to post stickers against sexual harassment on public transport.

A hostile environment smoulders in the Green Party; a large members��� group, Green Party Women, was disaffiliated, feminist events are sabotaged and activists have been suspended or expelled.

Berry���s ill-judged intervention is unsurprising – she is an implacable warrior against Green feminists, against any debate about trans-gender politics and against those who endorse the meaning of ���woman��� in the UK���s equalities law (that is, woman = adult female sex), recently re-affirmed by the Supreme Court. She also takes a hard line on prostitution ��� sexual exploitation is merely sex work (the two themes are often paired in Green and trans-cult politics).

The party leaders��� animus has almost bankrupted the party: around ��1 million has been spent defending itself – and losing – in anti-discrimination legal cases. The party is paying a high price for their bullying and deployment of what in Stalinist Russia was deemed the use of ���administrative methods��� against critics (in the Soviet case, to dispatch dissidents to prisons, labour camps and asylums).

Millions of activist hours will have been squandered on disciplinary procedures and expulsions.

For the avoidance of doubt, the Green Women���s Declaration is not trans-phobic, or hostile to men or women who choose to live as if they were the opposite sex, and its advocates have never resorted to violence or threats.

Its 1600 signatories resist ���the chilling atmosphere of censure within the green Party���. They insist on freedom to speak up for biological reality and the core values of science-based policy-making on climate and the environment.

They also want a more democratic and accountable party structure. At the moment anyone can turn up to the party conference ��� a seemingly open structure but, in practice, one that can be captured.

Berry is one of the censors. So, too, it seems, is new leader Zack Polanski who has defended the party decision to ban Green Women���s Declaration from holding a stall at the party���s October conference on the grounds of their ���bad behaviour’.

What behaviour? He didn���t disclose. My guess is that he couldn���t because the Green feminists are typically scrupulous: they haven���t stalked or suspended members, smashed up venues or events.

They are not transphobic ��� they never say that trans people should not exist. And they oppose the cultish mantra ���no debate���. My guess is that it is the feminists��� very presence that is offensive to the trans cult.

That is certainly what motivated the masked Bash Backers when they vandalised the Brighton Centre. Berry and Polasnski should have a word with themselves ��� they need to take responsibility for the fine mess in which they and the party finds themselves.

It is urgent ��� the party is the beneficiary of an unprecedent rush of support ��� membership up from 40,000 to over 100,000. This surge reveals a longing for a new configuration of progressive politics. It follows mass disappointment with Sir Keir Starmer���s hapless, authoritarian Labour leadership, and equally mass disappointment with the chaotic launch of Your Party .

The surge is attracted by the optimism of Green policies and, no doubt, Zack Polanski���s audacious performance as the party���s new leader.

What these new members want and deserve is the Green esprit translated into progressive political practice. What they won���t want is bullying leadership, expulsions, and misogyny, and they certainly won���t want Bash Back.

Further ReadingMy sorry stories about trans-cults, censorship and misogyny:

2010: Censoring Julie Bindel

2015: We cannot allow silencing and censorship of individuals

2016: TRANS/formations

2017: Letter to the Working Class Movement Library

2020: Bad Dreams ���Greens and Gender

October 10, 2025

Without Her Knowledge: The Politics Of The Gaze

More than 30,000 pictures and videos were taken by Dominique Pelicot of his wife, middle aged French woman Gisele Pelicot, without her clothes on, without her senses, and without her permission or knowledge. She had never seen his industrial cache of images of her in induced abjection, until the police discovered them inadvertently, and learned that they were shared among unknown numbers of men in a covert network, Without Her Knowledge.

She decided to waive anonymity and wanted some of the filmed scenarios be shown in the exceptional 2024 rape trial in Avignon of 52 men – her former husband and 51 others living in and around her village in southern France. Dominique Pelicot had filmed them after he secretly invited them to enter his wife’s bedroom and rape her whilst she was unconscious.

One of her abusers, Husamettin Dogan, reprised the ghoulish scenario in October 2025 when he appealed against his conviction for rape (to which he had initially pleaded guilty) and nine-year jail sentence. He appeared in court in Nimes to present himself as the victim: he had been manipulated by her husband, he said, who filmed him enter their bedroom, wearing only a condom, where he raped her: No, not rape, he told the court, just ‘sexual acts’.

For a while, he’d said, he thought she was dead. He didn’t explain whether he wondered how she’d died, or how, therefore, she had consented to anything, or why, then, he persisted.

Some of the video footage, showed Dogan penetrating an inert Gisele Pelicot and also trying to force her to ‘perform oral sex’ on him. He claimed to have been there for only half an hour, but the police had produced video footage of him at her home that lasted more than three hours.

The Pelicot trial had been an epochal event in which the main witness, the woman, ‘could say nothing about her experience but the videos spoke for her.’ It told the world something it hardly knew about some men, and their proclivities; their technology of sexual surveillance finally opened the aperture on a hitherto closed community that shared their malign sexual interests, their dedicated voyeurism and their sexist world view.

The trial showed how for a decade these men had been closeted in a masculine culture that preserved men’s secrets, that licensed their privileged gaze and their warrant of entitlement – a kind of material and visual droit de seignior – that is understood thanks to the great feminist insight: the politics of seeing.

Among the remarkable features of the trial was that Gisele Pelicot appeared in person, and announced that shame changed sides, that it belonged to them, not to her. She insisted that the public arena should be allowed to witness their bodies abusing hers.

Then she performed another radical reversal of the rape relationship: during the trial she faced them and stared at them when they gave their evidence. She confronted them with the one thing they had been guaranteed to avoid: her gaze. It was a scarcely-noticed rebellion that disrupted the power of the male gaze that had animated the whole project.

‘Without their Knowledge’ was devised by her husband to deliver the unconscious, unseeing woman in a decade-long, elaborately constructed mis en scene, to recruit male accomplices.

The project realised, in extremis, the gender power axis that film theorist Laura Mulvey described in her 1975 Screen magazine essay, Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, in which she argues that ‘the unconscious of patriarchal society has structured film form.’

It structures ‘ways of seeing and pleasure in looking.’ Women are the spectacle, they appear but don‘t define or direct the cinematic narrative, nor do they impinge on what the viewer sees: the gaze, says Mulvey, is constructed through a patriarchal lens.

Mulvey published this hugely influential theory in 1975. In 1972 the art critic John Berger’s revolutionary Ways of Seeing, a book based on a television series made by Mike Dibb, had theorised the politics of seeing and described men as the surveyors of women, and women as doomed to survey themselves: to gain any control over the process, the woman must ‘interiorise’ it in order to ‘constitute her presence’.

Men see, women are seen, ‘men act, women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at.’

These insights, formed in the white heat of the Women’s Liberation Movement, help us think about the politics of seeing in the Pelicot crime scene and then in the trial.

In Dominique Pelicot’s meticulous preparations over a decade, his ardent attention to his wife’s everyday comforts camouflaged the drugs he fed her in the evenings that rendered her comatose. She could neither consent nor contribute anything to her metamorphosis from a sentient woman of a certain age to a prostrate, inert, imagined player – an object whose objectification was consummated by the ubiquitous gaze of the abusers and the man behind the camera.

This absolute antithesis of consent – the mission of ‘Without her Consent’ – ensured the men’s absolute sovereignty.

In this drama, however, Gisele Pelicot was not inanimate, she was alive: without her will she was transformed, transported into their fantasy and thus traduced.

Psychologist Elly Hanson has elaborated a weighty challenge to notions of consent: she cautions that in reality ‘much consensual sex is unwanted, harmful or profoundly regretted.’

Gisele Pelicot’s predators were assured that she had consented, that her unconscious participation was part of a game. But it seemed to have escaped them that this was a contradiction in terms: she could not know to what she had consented, and she could not consent to what she could not know.

Hanson insists that the objectification of Gisele Pelicot was not only a ‘violation of her dignity, a kind of mocking – you will be what I want you to be – but also part of a group process: what they were doing together is pivotal.’

The men’s game was enacted in both their rape and the circulation of it, and the collective pleasure in it.

Hanson argues that this critical dynamic, sometimes overlooked, ‘is how offenders are engaged in a collective project of dominance – co-constructing their version of warped masculine power – vicariously enjoying each other’s dominance, performing their own, and losing themselves in the power of the whole.’

This dominance of the gaze, ‘is a part of the violation of their victims’ vulnerability – this sense that they can wholly take in their victim, whilst they themselves are impenetrable (double meaning intended).’

The beating heart of this offending is the body’s massive surge of sadistic, omnipotent energy and contempt. Typically, adds Hanson, these men often ‘move into victim-stancing when faced with their abuse, a form of gaslighting that so often bamboozles and confuses, whether it be to narrate oneself the victim of earlier abuse or of the other offenders.’

This was manifest in the Domminique Pelicot case, in ‘a deep-seated sense of aggrievement on display, the feeling that flows from thwarted entitlement.’

When Gisele Pelicot insisted on facing the perpetrators during the trial, looking at them, staring at them, she exposed them to the last thing they sought: the experience of being seen. Seen this time, that is, not within their own cult of sexual surveillance, but by the public and above all, by their victim, herself.

During the months of that long trial, Gisele Pelicot was witnessed by crowds gathering inside and outside the court, no longer an object, but a speaking subject with a lot to say. So, the politics of the gaze and of sexual objectification were aired unequivocally.

If it was hard to imagine that Gisele Pelicot could recover her privacy thereafter. Nonetheless there would have been a general consensus that she was entitled to it and that her society would support it.

But we were reminded of the mass media’s perverse – and patriarchal – sense of entitlement in April 2025 when Paris Match published uninvited photographs of her out walking with a male friend. She had changed her name and her where she lived. If she had forfeited anonymity during the trial, she now sought to regain her privacy.

The behavior of Paris Match contrasts with the strategy of press photographer, Ray Belisario, Britain’s first and most famous invader of royal privacy who confronted the monarchical mantra ‘be seen, above all be seen’ but only in conditions of sovereign choosing.

The intrepid Belisario was known as the first British paparazzi, but his mission was much more disciplined than that might imply: he was a republican, he was not interested in snooping inside royal closets or under their skirts, he wanted to breach monarchical fortifications that controlled who and what their subjects could see.

His mission was to confront the constitutional historian Walter Bagehot’s proposition that the monarchy’s ‘mystery is its life. We must not let in daylight upon the magic.’ Mystery secured their sovereignty. That was his political target. Paris Match, by contrast, trespassed on a life that did not parade power, but the opposite, and re-iterated uninvited, unwelcome intrusion that had become the story of her life.

Gisele Pelicot sued and she forced Paris Match to concede and pay compensation to services for women subjected to violence.

She would show that this woman had not survived multiple rapes and 30,000 images taken in the most sordid circumstances without her consent, only to have a mighty, mass circulation magazine publish her image, yet again without her consent.

At the end of Dogan’s appeal case, on 9 Oct the court resolved to increase his prison sentence, and the Prosecutor Dominique Sie confirmed the social heft of the Pelicot revelations: Dogan’s stance was a clear illustration, he said, of persistent rape culture and male domination. Unusually, perhaps uniquely, Without Her Knowledge was understood not as indivudual malevolence but a system that was simultaneously contested and prevalent.

September 26, 2025

Out and Out Betrayal

Bravo Ruth Davidson ��� the first openly gay political party leader in the UK, former leader of the Scottish Tories, former Member of the Scottish Assembly, former journalist and former army signaller ��� now a member of the House of Lords.

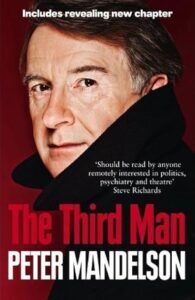

With characteristic verve she denounced Lord Peter Mandelson in September when his craven excuses for continuing his ardent friendship with ludicrously rich and pathological sexual abuser of girls, Jeffrey Epstein.

The allure of this elite networker, conman and convicted sex offender was irresistible to Mandelson ��� even after Epstein���s conviction he proclaimed ���we love you���. He had been jailed for trafficking in minors and years later was alleged to have sexually abused scores of young women.

Mandelson���s scarcely credible excuse was that he never witnessed abuse and wrong-doing, and ���never sought or was offered��� introductions to young women, ���perhaps because I���m a gay man.���

Oh no, protested Ruth Davidson, Epstein was notorious for entertaining grandees on his Lolita Express and his luxury ���paedo island���. ���I���m absolutely disgusted,��� she said, ���don���t you dare use that as a shield.���

Her fierce rebuke brought to mind Mandelson���s less than felicitous commitment to the gay movement that made his sexual orientation legal and his marriage to his partner possible.

He had no time for the social movements that challenged and changed the law on domestic and sexual life.

In 1998 he reacted with fury when gay Tory MP Matthew Parris commented to Jeremy Paxman in a BBC Newsnight discussion, that there were at least two gay members of the Cabinet: Paxman baulked and did his best to apologise to Mandelson. But he was having none of it.

His private life was private, he insisted ��� even though everyone ��� including his constituents, seemed to know and weren���t bothered, and even though he would invoke his private lfe when he wanted to boast about his grandfather, the Labour politician Herbert Morrison.

In the event, the abject BBC banned any mention of Mandelson���s ���private life��� for the next decade.

In 2006 the Liberal MP Simon Hughes, another militant guardian of his private life, was outed and forced to acknowledge that he was ���bisexual.���

Here���s what I wrote about these politicians and their private lives in The Independent on 29 January 2006:

Coming out can be horrible, scary, embarrassing and unfair. It is not easy, and it never stops. But you must do it, especially if you have power, and most especially if you are a politician. Parliamentary culture has no excuse for making it so difficult, but Members of Parliament have no excuse for not coming out.

There are only two excuses with merit: that you would be sacked, and that you cannot bring yourself to tell your mother. Politicians are not sacked, and if you are a politician, somebody else is going to tell your mother. So, for a politician, there is no excuse.

This is not to say it is not onerous. Coming out to my family was worse than telling my parents I had been done for shoplifting (pinched a book from an art shop). It was worse than telling them I had failed my A-levels (they minded for me). And it was worse than telling them I was going to get married (no one was good enough).

It is worse because gay people have to do something no heterosexual person ever has to: draw attention to something you do not want them to have in their head, your sexuality and your sex life. And it is worse because you are giving your parents something to deal with at that point in your life which is about autonomy.

In the early 1970s, I told my mother I had fallen in love with a woman. I was 23, married, and intoxicated with the Women’s Liberation Movement. I had my own home, my own Hoover, my own husband – all the signifiers of having my own life. Although this new thing was tumultuous, I was suddenly living my life; it was such a surprise, such a thrill. But still, this was something so seismic that it rustled everything, all the way to my mother. Of course, it was my business, not that of my mother, but it was an issue, because being gay is always an issue.

She was good, as I knew she would be. Whenever anything homophobic was said in our house, only by my father, she would challenge him with the tenacity of a sly fox. She was a hospital nurse, she worked with gay people, they were part of her universe.

After I told her, she must have been sleepless, because she woke me in the middle of the night and said: “Homosexuals should have the same rights as anybody else.” Then she went back to bed. She did not mind me being gay; what she struggled with was another loved one in my life other than her.

I dreaded my father’s reaction. I did not want to talk to him about my sexuality and I did not want to negotiate his political prejudice. He was a British bolshevik who prized the muscular iconography of revolutionary heroism. He endorsed a leftist fiction that homosexuality was a bourgeois deviation. It was a legend encouraged by spy scandals implicating upper-class fops, or class contempt for posh camp.

His working-class hauteur was transformed not by me, but by watching Quentin Crisp’s bewitching autobiography on television. My father wept. Whether it was Crisp or his daughter, he softened, and took strength. The reaction I was not prepared for was from sympathetic relatives who congratulated me for not, well, looking like a lesbian. “You’re not an evangelist.” Oh, but I am, I thought. I had been compromised by my good manners.

And I will never forget coming out to a boss. This was during the ecstatic swirl of 1970s sexual politics and the organisation was hot with scurrilous gossip about a couple of women who had fallen in love. I went into his office and told him I expected him to do the right thing, to support them. (I knew he had not.) He had affairs, but his desk was crowned with photos of his wife. His reputation was intact. I also told him I expected him to do the right thing by me. Instantly, I saw a blush, not of embarrassment, I am sure, but of arousal. We all know the place of lesbians in the fantasies of some men. I was exposed. He was not.

Among my lesbian friends, some women are out with everyone except their mothers. One friend survived a custody battle in the days when lesbians always lost their children. She had to do something no heterosexual person in a custody case has to, describe “what you do in bed”. She did that, she survived grotesque humiliation and the hazard of losing, she showed her valour, but she could never use the “L” word to her mother. Why? “I didn’t want her to reject me.”

That nightmare – losing your mother – is indicative of the risk. Every gay man or woman I know has a story of great imagination, dignity and fortitude. Being gay commands great courage. As the brutal death of poor David Morley reminds us, being gay can get you killed. The greatest heroism is shown by people who are ordinary. They are not stars, they are not politicians, they have no social power, no back-up, only other gays.

The most culpably craven are politicians. Their mothers are no excuse; they routinely recruit their “private life” in the service of their power. Simon Hughes has told us about the respectable poverty of his parents. Peter Mandelson, the former MP who never wanted to tell us he is gay, has assiduously told us about his genealogy: his grandfather was the right-wing, post-war Labour politician Herbert Morrison. The connection, presumably, added value to his CV. Mandelson used his public power, his proximity to the Prime Minister, to control what the BBC could say about him.

Neither Mandelson nor Hughes resisted the temptation to intervene in the private lives of others. Simon Hughes, in many ways a likeable advocate of liberalism, used his power to restrict access to abortion. He is a Christian. His church has, for a millennium, regulated where men put their willies, what women may do with their bodies, when and if they have babies, and who may couple with whom.

Mandelson was a guru of the late and unlamented cult, the Third Way, that sponsored the misogynist family policies of the first term when, lest we forget, one government priority was to cut benefits for lone parents.

The marque of New Labour’s modernity was the aura of representivity of the class of 1997: the energies of the black movement, the women’s movement, the gay movement that transformed Labour’s parliamentary profile. These were the new social movements of the 1960s and 1970s, which had confronted the historic settlements that shaped modernity, colonialism, patriarchy, and the polarisation between work and home, public and private. These were the movements that brought us the idea of personal oppression and the concept that “the personal is political”. But they were ostracised by New Labour, which lent its endorsement to the idea that it was right on to be right off.

It is a fable of populist politics beloved by politicians – always more conservative than the civil society they represent – that private life is private. The notion relies on conventional wisdoms about nature and tradition, it trades on public anxieties during times of social rupture, and it invokes traditional power as a way of restoring security. Their moralism makes them conservative about the “private” lives of the public.

The vanity and grandiosity of the parliamentary mission is personal; career politicians do it because, they tell us, they want to make the world a better place. Neither Hughes nor Mandelson has any right to claim the shield of private life, not because they are “public” figures, but because political power, uniquely, allows them to intrude in our collective “private life”, for better or worse.

A private domain, a sequestered refuge beyond the marketplace, uncontaminated by politics, is a fiction. There is no such thing as private life. Our sexualities are social relationships. Sexual orientations, births, marriages, deaths, domesticity, all of this is as intensely regulated as traffic lights, or the nuclear bomb.

The solitary confinement of women in the home was not an effect of evolution but the outcome of a 19th-century power struggle between men and women, and the intervention of public men – in the state, corporations and trades unions – which determined when, whether, and how much women may be paid for their labours.

Marriage is as natural as Pot Noodle; the impetus for modern marriage en masse is relatively recent, it was the public enforcement of women’s personal dependence on men rather than on the church or the state. Church and state determined when marriages may begin and whether they could end. The state determined, until recently, that men may beat and rape their wives, but they may not bond sexually with men.

Everything about our bodies, how we imagine them, where we put them, with whom, whether on a bus, or in a park or in a bath house, or a home, has been the subject of public regulation. Desire and pleasure, likewise, have been scrutinised and legislated by the public guardians of corporeal activity. When we are born, we are scrupulously monitored, tested and immunised, and now the Government is fighting for access to our DNA. I do not mind the state accessing my DNA, but then I do not think there is any such thing as privacy. These claimants of privacy, Mandelson and Hughes, never had it; people talked about their sexuality all the time. They knew that.

Hughes’ resistance to definition has resonance. Heterosexuality’s dominion ensures it is never defined. And it claims the power to define the deviation. Hughes’ protest is, inevitably, about shame. He may not feel he is gay. But there is a difference between what he is and what he does. Desire is activity not identity.

That is the beauty of the label: gay is what you do, not what you are. And that is why his denial is a lie; by lying he revealed he is not proud of himself or other gay people. He has done a disservice to young people finding their sexuality, and older people who had to fight for it. Hughes and Mandelson have a generational public duty to be proud. I am, because I, like them, belong to the generation that made our gay lives liveable and lovable.

July 23, 2025

Sir Keir: the Honourable Gentleman who is for turning

Perhaps Sir Keir Starmer ‘misspoke’, perhaps he forgot or Trump-like didn’t really know what his 2024 election manifesto did and didn’t pledge, when he decided to withdraw the party Whip from four MPs on 17 July 2025 for allegedly transgressing the manifesto.

‘We had to deal with people who repeatedly break the whip because everyone was elected as a Labour MP on the manifesto of change and everybody needs to deliver as a Labour Government.’

He should consult that 2024 document, punctuated by photographs of himself and proclaiming how he has changed the party. He would be reminded that Starmer’s cruel cuts are not delivering the 2024 manifesto, and they aren’t supported by public opinion.

Nowhere in the manifesto is there a promise to cut disability benefits, keep the two-child benefit cap or abolish pensioners’ winter payment allowance.

These MPs did not disavow the manifesto, he did. He has emerged as, a conjuror of the false promise, an Honorary Gentleman who is for turning.1

The punishment of York’s MP Rachel Maskell is emblematic of the chasm between the leadership cabal and the voters. Maskell is a former physiotherapist and trade union official, a popular advocate of ethical socialism. Her values are what could be called decent – she is a Christian whose voting record is generally consistent with the values of the progressive electorate, from the environment to public ownership of national utilities and transport, social welfare, equality and human rights.

You have to wonder what the Labour Party is if not a manifesto that the Maskells of this world could promote.

Starmer by contrast is shut, ambitious yet on the wrong side of history on much that matters, not least re-distribution of wealth and power, and above all Israel. His notion of the party appears as the antithesis of, for example, Labour’s post-war leader, Clement Atlee who, arguably, steered Labour’s most momentous change agenda ever; he was on the right, but he broke bread with politicians across the firmament and, most important, grasped the necessity of the left’s presence and roots in popular feeling.

Not even Tony Blair, on a mission to re-locate Labour to the centre of the political firmament, was so insecure as to invoke the Inquisition.

Not so the Starmer clique. When Chancellor Rachel Reeves proclaimed ‘this is a changed party, not a party of protest’ she identified: merely what it wasn’t. But what else could it – should it – be after the Tory deluge and genocidal war-making?

Starmer’s latest round of Parliamentary detentions is indicative of a theory of the party as an audience, a subaltern servant, not a movement – a space in which multitudes can muster, experience the pleasures and productivity of solidarity; a space to think, a source of collective self-discovery and a resource to do stuff that answers society’s problems.

It is not just that the leadership is managerial and macho, it is worse, much worse, it is pathological, animated by visceral hatred of the left – exemplified by the serial harassment of Diane Abbott.

By the time Starmer was elected Prime Minister in 2024, he had emptied the party of half its membership, though Labour remains the biggest political party in an emaciated political culture. His government is weak, adrift from a a social base, for which, evidently, it has little interest or respect.

In their book Get In Patrick Maguire and Gabriel Pogrund chronicle the modus operandi of Starmerism – furtive, furious, manic and yet strangely maladroit. His boot camp regime won’t equip the party with strength and valour, more likely an indecent scramble to who knows where.

In 1980 Tory Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher refusal to respond to recession and roaring unemployment. ︎

︎Photograph: Reuters

Sir Keir:�� the Honourable Gentleman who is for turning

Perhaps Sir Keir Starmer ���misspoke���, perhaps he forgot or Trump-like didn���t really know what his 2024 election manifesto did and didn���t pledge, when he decided to withdraw the party Whip from four MPs on 17 July 2025 for allegedly transgressing the manifesto.

���We had to deal with people who repeatedly break the whip because everyone was elected as a Labour MP on the manifesto of change and everybody needs to deliver as a Labour Government.���

He should consult that 2024 document, punctuated by photographs of himself and proclaiming how he has changed the party. He would be reminded that Starmer���s cruel cuts are not delivering the 2024 manifesto, and they aren���t supported by public opinion.

Nowhere in the manifesto is there a promise to cut disability benefits, keep the two-child benefit cap or abolish pensioners��� winter payment allowance.

These MPs did not disavow the manifesto, he did. He has emerged as as, a conjuror of the false promise, an Honorary Gentleman who is for turning.1

The punishment of York���s MP Rachel Maskell is emblematic of the chasm between the leadership cabal and the voters. Maskell is a former physiotherapist and trade union official, a popular advocate of ethical socialism. Her values are what could be called decent ��� she is a Christian whose voting record is generally consistent with the values of the progressive electorate, from the environment to public ownership of national utilities and transport, social welfare, equality and human rights.

You have to wonder what the Labour Party is if not a manifesto that the Maskells of this world could promote.

Starmer by contrast is shut, ambitious yet on the wrong side of history on much that matters, not least re-distribution of wealth and power, and above all Israel. His notion of the party appears as the antithesis of, for example, Labour���s post-war leader, Clement Atlee who, arguably, steered Labour���s most momentous change agenda ever; he was on the right, but he broke bread with politicians across the firmament and, most important, grasped the necessity of the left���s presence and roots in popular feeling.

Not even Tony Blair, on a mission to re-locate Labour to the centre of the political firmament, was so insecure as to invoke the Inquisition.

Not so the Starmer clique. When Chancellor Rachel Reeves proclaimed ���this is a changed party, not a party of protest��� she identified: merely what it wasn���t. But what else could it ��� should it – be after the Tory deluge and genocidal war-making?

Starmer���s latest round of Parliamentary detentions is indicative of a theory of the party as an audience, a subaltern servant, not a movement – a space in which multitudes can muster, experience the pleasures and productivity of solidarity; a space to think, a source of collective self-discovery and a resource to do stuff that answers society���s problems.

It is not just that the leadership is managerial and macho, it is worse, much worse, it is pathological, animated by visceral hatred of the left ��� exemplified by the serial harassment of Diane Abbott.

By the time Starmer was elected Prime Minister in 2024, he had emptied the party of half its membership, though Labour remains the biggest political party in an emaciated political culture. His government is weak, adrift from a a social base, for which, evidently, it has little interest or respect.

In their book Get In Patrick Maguire and Gabriel Pogrund chronicle the modus operandi of Starmerism – furtive, furious, manic and yet strangely maladroit. His boot camp regime won���t equip the party with strength and valour, more likely an indecent scramble to who knows where.

In 1980 Tory Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher refusal to respond to recession and roaring unemployment.�� ���

���Photograph: Reuters

April 4, 2021

Somewhere in England’s Green and Pleasant Land…

* Rising and falling stars: Aimee Challenor

(First appeared on Byline, September 2018)

Somewhere in England there is a girl who was raped, tortured and electrocuted by a well-known local Green Party figure in Coventry, David Challenor. During his criminal trial his victim described his rituals in which he dressed as a little girl or a baby in a nappy, at a house used as an official Green Party address in 2015. For anyone, this case is cruel and cautionary – for Greens it is a huge political crisis.

We know that nothing is more important than community respect and validation for the survivors of sexual crime. This girl didn’t get it. Her lonely journey to the criminal court was vindicated – last month the perpetrator, David Challenor, received a 22-year-sentence.

But she was denigrated and abandoned by the people who mattered most, her intimate community, the Challenors, well-known Green Party activists. It was the abuser they supported, not his accuser.

The police interviewed members of the family in October 2015, including Aimee Challenor, who had just left the care system and began the process of transitioning to a girl. Aimee was an ambitious young trans activist who became Green Party equalities spokesperson in 2017 and a party candidate. Hailed as a ‘rising star,’ Aimee Challenor pitched into the party’s deputy leadership election.

She insists that despite the criminal charges she was ‘building bridges’ and attempting reconciliation with her father, who she twice appointed as election agent – there are no criteria regulating agents, according to the Electoral Commission. But she declined to inform the party leadership until Challenor was sentenced. Individuals knew, but didn’t act.

Coventry Pride took swift action after learning of the case in 2016. Why didn’t the Green Party or other organisations associated with Aimee Challenor, like Stonewall, follow its lead?

Members are now asking whether there was anything else Aimee Challenor didn’t disclose, they are alarmed by robust research by veteran social media monitors.

that reveals her own involvement in adult-baby fetish network

The scandal has scalded the Green leaders. An inquiry has been launched, David Challenor has been expelled. When mutiny among party members forced Aimee’s suspension in early September, Aimee Challenor quit, accused the party of transphobia and blocked Caroline Lucas on Twitter as a trans exclusionary radical feminist.

But the inquiry needs to do more than poke around the guile and cruelty of David Challenor and the Green Party needs to do more than lament its own misfortune in being gulled by the Challenors. And it needs to ask why the party’s initial official statements about the scandal pathetically paid more attention to Aimee Challenor’s need for support than the vindicated – but traduced – child.

The inquiry should ask how the party lost its marbles about gender and sexual politics and whether the party’s hard-line trans policies provided what sexual violence scholar Prof Liz Kelly calls a ‘conducive context’ that shielded the Challenors from scrutiny.

How did an open and democratic party sometimes behave like the Inquisition hunting trans heretics, particularly feminists, who have been harassed and disciplined, notably the lesbian activist Olivia Palmer, who has been expelled?

How could it come to pass that the Green Party has forced luminaries Rupert Read and Jenny Jones to publically recant their scepticism.

Aimee and David Challenor mobilised Twitter widgets to block ‘trans exclusionary radical feminists’ – last year Aimee Challenor proclaimed the campaign’s success in blocking 50,000 people deemed ‘terfs’ and bigots, and getting one vocal feminist transsexual, Miranda Yardley, being banned from Twitter for life.

When Miranda Yardley was invited to address North Surrey Green Party, they were forced to disinvite Yardley and then became the subject of a ‘transphobia’ complaint themselves. The Green Party executive didn’t protest against ‘terfblocking’. The party’s universally-respected leader Caroline Lucas hated it, but described herself as powerless to resist it. I myself complained to a senior member of the Party about terf-blocking and others did, too. Apparently no action was taken. Now Lucas herself has been terf-blocked.

The inquiry should ask who in the leadership supported Aimee Challenor’s legal action to silence Green Party activist Andy Healey – he launched Gender Critical Greens, a feminist resource, and insisted on identifying Challenor as a man. The legal action against Healey is still unresolved. Healey was not allowed to address the party conference, whilst David Challenor was given a platform to propose motions despite his impending trial on the most serious child sexual abuse charges.

Other political parties should not be smug about the Greens’ crisis and catharsis – they’ve tolerated a trans modus operandi and ideology that is bulwarked by a kind of religiosity, by claims that to debate its hypotheses is to eliminate trans people: debate is death.

The Working Class Movement Library in Manchester was aghast to find itself targeted by a trans campaign to staunch its funding.

Gay organisations, too, have been blasted by trans harassment, Manchester’s Queer Up North Festival Organiser, Jonathan Best, chronicles his grim experience. Gay people are increasingly alienated by the seemingly endless expansion of categories attached to ‘gay and lesbian,’ including trans, that have nothing to do with sexual orientation.

A closed Facebook group was promoted to name and shame academics deemed transphobic, by Goldsmiths University trans researcher Natacha Kennedy. Kennedy is also Goldsmiths’ Mark Hellen – they are one person, two personas. They appeared as ‘joint’ authors of a paper on ‘transgender children’:

Sussex University philosophy professor Kathleen Stock became a cause celebre when she was pilloried for urging philosphers to engage in the gender debates flaring in social media. She was condemned as transphobic by the students union but in July the university’s vice chancellor Adam Tickell ventured where the Green Party does not tread by affirming both trans people’s human rights and academic freedom, ‘I hold a deep rooted concern,’ he wrote, ‘about the future of our democratic society if we silence the views of people we don’t agree with.’

The Liberal-Democrats, the Tories and Labour, gay organisations and mass media commentators across the political spectrum should all start asking how they fell for trans folly that is not sustained by science, that doesn’t enjoy consensus among many trans women and trans-sexuals, and certainly not among maybe most women.

The dogma has been assiduously promoted as a new civil rights frontier and fortified by no-platforming, bullying and what can only be called blacklisting of dissenting voices deemed ‘terfs’ and ‘bigots’ on the wrong side of history. The mantra ‘There is no debate’ is recited not only in the Green Party but across the political firmament.

It is as though nothing is real, there is only ‘gender fluidity’ and freedom of choice that synchronises marvellously with neo-liberal erasure of oppression and exploitation. The notion that anyone can be anything they want to be, that a man is a woman if he says he is, empties ‘woman’ of meaning – some Greens refer to non-women to satisfy trans sensitivities.

The Challenor case is an arrow to the heart of Britain’s twisted sexual politics. Already gay activists are joining feminists and saying they are sick of the narcissism, misogyny of some trans activists:

The Green Party’s inquiry is, therefore, more important than the Green Party itself – it should open a window on the degradation of political culture.

The inquiry should also review the Green Party’s child safeguarding policy and processes. Although the party has vigorously promoted an extreme trans policy and practice, I have trawled through GP policy and can’t find a specific policy or protocol on child abuse and safeguarding, despite massive public concern in the wake of the Savile scandal in 2012, despite the work of Caroline Lucas and her Parliamentary colleagues in securing the launch of the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse, and its public reports on institutional complicity in child abuse.

Aimee Challenor was a teenager undergoing transition with the support of Mermaids, an organisation chided by the High Court, and criticised by some for advocating medical interventions at puberty that amount to child abuse:

Aimee Challenor was a teenager undergoing transition with the support of Mermaids, an organisation chided by the High Court, and criticised by some for advocating medical interventions at puberty that amount to child abuse:

The Challenor family had been subject to its own High Court proceedings because of the parenting the children in the family received. Whilst many children who exit the care system do so with dignity, independence, qualifications and readiness to enter the adult world, Aimee Challenor appears to have been in a family who fought against children’s services’ support and yet, by her own account, turned to the parents for support and reconciliation after leaving the care system.

The inquiry must ask: Did no one in the Green Party at the time recognise the consequential vulnerabilities which the leadership are at now at pains to stress? Did the executive consider duties of care towards a teenager going through profound personal changes, with an extreme trans ideology, being propelled into a leadership position?

Is the Green Party preparing for a possible Serious Case Review into the Challenor case, which would undoubtedly be interested in the context and culture of the child’s family and her abuser, his activity in other contexts and other institutions?

Did the leadership and executive’s support for Aimee Challenor’s trans agenda, and the party’s early, strident rush to endorse an extreme trans position, obscure child safeguarding responsibilities?

On a personal note, I should say that I am a Green Party member. I’ve stood as a candidate in local and parliamentary elections. My own journey into these debates was provoked more a decade ago by no-platforming and censorship of debate:

This forced me to address the issue itself. I have benefited from feminist writing, obviously, the eloquent essay on gender, race, class and identity politics in the Jenner and Dolezal cases in the US by political scientist Adolph Reed Jnr, and the intelligence of many transgender women and trans-sexuals. They are profoundly dismayed by the authoritarianism and speciousness of trans policy in the Green Party and the spectacular nastiness of some extreme trans advocates: Sarah Brown, a Liberal Democrats candidate in Cambridge, notoriously rebuked a fellow councillor Richard Taylor with ‘suck my formaldehyde balls’.

I support Gender Critical Greens and Woman’s Place_UK and their campaign for women’s places and safe spaces, I have chaired two of their public meetings. Trans activists have harassed the organisers and the venues, frequently obliging the organisers to change venues. In Newcastle this summer Northumbria University agreed to a last-minute booking of their out-of-town campus. A local trans activist put out an alert warning trans people that they’d not be safe in the city: watch out there’s terfs about

Many heart-sick Green Party members are now voicing their worries and urging a full review that goes beyond the Challenor debacle and reassesses policies on trans, gender and sexual politics generally, and the safeguarding of children specifically.

Some of us will give evidence to the Parliamentary committee on the Gender Recognition Act. Given the fate of others, and aside from my own decisions about whether I remain in the Green Party, we need to know whether this will this result in disciplinary action, and whether the party is prepared to forfeit seasoned and intelligent activists over bullying, misogyny and cultish trans dogma?

Members of other organisations should be asking themselves the same questions.

Check out Jorg C’s forensic takedown of Aimee Challenor and Challenor’s husband Nathaniel Knight, a person with long-standing and acknowledged interest in fetishism and fantasies about sex with children: https://grahamlinehan.substack.com/p/something-rotten-at-the-heart-of

The post Somewhere in England’s Green and Pleasant Land… appeared first on Beatrix Campbell.

September 15, 2020

Sex crime and ‘shining rights’

FUREDI INTO THE ABYSS

Is there a consensus about sexual abuse of children and rape generally? The answer to this question would seem self-evident but it isn’t. There are laws, of course, but laws don’t describe consensus. Nor do they create consensus. Laws may describe prohibitions and rights, but they do not effect either rights or prohibitions.

The eminent lawyer and former Appeal Court judge, Stephen Sedley cautions that ‘Any state can set out rows of shining rights, like medals on a leader’s chest…’ But rights only have meaning, he says, in their implementation, and their application to intractable conflicts of interest.

Long-standing laws proscribing sexual acts with children exemplify Sedley’s point: sexual offences laws attract many-a-medal but few rights. More than 90 per are never reported, and fewer than 10 per cent of reported rapes ever reach a courtroom. Legal prohibitions are not the same as legal rights.

This failure goes to the crux of consensus and whether we mean what we say about sexual assault and rape. Failure to implement the law contributes to the lack of consensus: it doesn’t create it, but it facilitates it. This gap exercises great minds in the criminal justice system, social justice and feminism. It is also the abyss into which sociologist Frank Furedi throws himself. He is a prolific emeritus professor and a go-to-contrarian in the right-wing media. He bundles random hypotheses into purported grand theories about the meaning of modern life, and his methodology is sound-bite rhetoric.

His work is an archetype of child abuse scepticism, a hyperactive, cynical engagement with nowness that masks hubris, an addictive againstness that is parasitical – it squats on terrain, phenomenon and agendas made by others, only to criticise or condemn.

Furedi reads the gap between sexual offences law and implementation as evidence not of hidden crime but of perils imagined by moral crusaders: the gap, therefore, between crimes, reported crime and justice outcomes, is confirmation that sexual abuse is bad but rare. He goes further: irrational paranoias and scandal-mongering menace civil society. Typically, he used the 2012 Jimmy Savile scandal to air a grand theory about the crisis of civilisation as we know it: Moral Crusades in an Age of Mistrust.

He omits concepts of power, oppression, suffering and inequality, and enlists ‘sexual violence’ instead as a transcendent term: ‘panics’ about rape and child sexual abuse sponsor his complaints about threats to civilisation, consensus, reason, public institutions and public safety, everything.

Let’s consider Furedi’s case and his method.

Consensus: Furedi argues that there is, or rather was, a moral consensus: everybody agrees that sexual abuse of children is wrong. But (contrary to the evidence) he insists that it is rare and it is exaggerated by feminists and other ‘moral entrepreneurs’ for their own political ends.

Furedi argues that moral consensus is being – or has been – disoriented and even displaced by the promotion of distrust in traditional institutions, and aversion to risk and the ordinary hazards of everyday life, ‘There is little consensus even on some of the most elementary questions about the meaning of life,’ he argues

Scandal: A moral apocalypse has been created by scandals that never clarify or clean up society, they just make people feel bad, they lead only to a ‘sense of disorientation’; Irrational suspicion and ‘sightings of new evils are an integral feature’ of moral crusaders who promote an ideology of evil that ‘rarely accepts that a problem has been solved.’

Sacred childhood: Amidst this loss of faith in the established order, he suggests, an idealised icon of hope glows, it is the child, a sacred ideal of innocence, an optimistic gleam in an otherwise incoherent world. Thus, he argues, we insulate childhood from sex and everything else, children are sacralised and sequestered, under the perpetual surveillance of anxious parents fearful of everything outside their domestic bubble.

He offers no evidence. Nor does he consider trans-Atlantic debates about the sexualisation of children in popular culture and the polarisation between masculinities and femininities in the marketing of childhood.

Culture of fear: He accuses paranoid adults of seeing sexual abuse everywhere – we won’t let our children just be; we invest not in their future but our own. We smother children not with love but with fear. His misanthropic prospectus brings a cynical frown to anti-oppressive movements and leads him to defend traditional institutions and consensus from challenge.

Thus, he claims panic is induced by the ‘tendency to massively inflate the peril of paedophilia’; scandals – typically the Jimmy Savile scandal – are a ‘moral crusade’, exemplified by the police inviting ‘the entire nation to recollect any incident of abuse that might have happened to them in the past’; by feminists contending ‘that the majority of young girls and women are subjected to some form sexual abuse by family members’ – for this he offers no evidence. He relies on the arch sceptic Richard Webster, who also offers no evidence.

There is a loss of authority, he says, exemplified by a chilling example, ‘the Catholic Church has lost significant moral capital as a result of the involvement of a few of its clergy in a series of sexual abuse scandals.’ Well, yes.

Crisis of authority: loss of trust derives not from the impact of survivors and radical social movements, not from the rise of democracy and the decline of deference, not from political scrutiny, but from moral crusaders, self-interested moral profiteers who exploit a few mistakes and misdemeanours to terrify everyone into feeling that they just can’t leave the house.

So successful has this been, he says, that even the authority of judges is called into question. He cites the movements to revisit the Hillsborough stadium disaster and abuse in North Wales children’s homes: The independent panel of inquiry into the 1989 Hillsborough football stadium disaster in which 89 people lost their lives ‘called into question’ the inquiry by Lord Justice Taylor. Furedi is wrong – the panel vindicated the Taylor inquiry and went further by accessing evidence of wrongdoing by South Yorkshire police that was unavailable to Taylor. The launch of the review by Julia Macur into the evidence available to Sir Ronald Waterhouse’s inquiry and his report, Lost in Care, ‘indicates that the authority of judicial independence is not beyond question.’ It might have. But, wrong again, the issue was not ‘the authority of judicial independence’ but whether Waterhouse had full access to evidence, and the ability to investigate it.

There is, for sure, an important debate to be had about the conditions in which scandals and public inquiries do or do not sponsor political change. The scandals following the Aberfan colliery disaster in 1966, Hull’s triple trawler tragedies in the 1968, the thalidomide drug scandal in the 1950s-60s, all exposed reckless disregard for safety.

The inquiries did not necessarily yield reform: in Aberfan the National Coal Board, the trade unions and civic authorities, were all implicated, and the potential agents of challenge and change were, therefore, compromised.

It took a decade – after mighty, lonely campaigns by the women of the fishermen’s families – before new laws regulated the fishing industry; It took three decades of campaigning by the Hillsborough relatives movement and the people of Liverpool, for the authorities responsible for the Hillsborough football stadium disaster to be called to account; it took four decades for relatives of the British Army’s murderous action on Bloody Sunday in Derry, Northern Ireland, to get the full story of what happened to the 13 unarmed people shot by the British Army.

All of these outcomes were contingent on whether the truth could ever be told, by whom, and to whom – to everyone? – and on whether it was made to matter. These are questions of political culture, the ‘balance of forces’ and hegemony. Politics and power, however, are nowhere in in Furedi’s chronicle, in which scandal is moralised rather than politicised.

A good example is telephone hacking, cited by Furedi as just another blow to institutions and reputations. The ‘crime’ at the heart of the hacking scandal was industrial scale, illegal hacking of people’s telephone conversations. Although it was initially represented as the price celebrities pay for being seen, the politics of hacking came alive in the House of Commons Culture Select Committee hearings in 2011. That was when the traffic of personnel between the Metroplitan police, the Murdoch press and Downing Street was disclosed. That was the moment when the hacking scandal became much more than the invasion of individuals’ privacy – though that was cruel enough; that was when we learned of secret and illegal surveillance that circulated between, and served the interests, of the Met, Downing Street and the Murdoch media empire.

The Murdoch media had established a symbiotic relationship between hackers, senior Metropolitan police officers, and Downing Street. They could spy on anyone. They could ruin anyone – not least their adversaries.

Children, teenagers, sex and violence: Furedi’s modus operandi appeared in 2012 in a blog that indicated his general approach to sex and sex crime.

In 2012 the British government launched a campaign directed at teenagers about sexual violence in relationships, and in particular, boys’ sense of entitlement. That year the parenting website Mumsnet launched its own campaign We Believe You campaign against rape.

The Home Office initiative was a novel campaign that fielded a ‘top man’, deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg, to promote equality in young people’s sexual relationships.

Furedi rushed into print. He had been triggered by an advert on London Underground, ‘REAL MEN GET RAPED… Talking about it takes real strength.’ He admitted that he didn’t get it. But that didn’t stop him. He threw in a third ingredient, the trial of two boys convicted of attempting to rape an eight-year-old girl. ‘The Home Office campaign is so obsessed with ‘raising awareness’ about an alleged epidemic of sexual violence that it wouldn’t recognise a healthy teenage relationship if it bumped into one. Once rape has been redefined as a normal feature of human relationships, it will end up being ‘discovered’ everywhere,’ he protested, so boys had been subjected to a ‘showtrial for being naughty and were convicted of attempted rape at the Old Bailey in London’ despite the fact that the eight-year-old ‘admitted in court that she had made up the story of her ordeal’.

There was indeed widespread unease among children’s advocates about the criminal trial. However, the boys were not tried for being ‘naughty’ and it wasn’t a ‘showtrial’. The judge and the lawyers divested themselves of their usual wigs and gowns, and during the trial the boys were allowed to sit with their mothers.

In 2010, the boys had been seen taking the girl to various locations to attack her. The girl’s mother had told been another boy that they were ‘hurting’ the girl ‘and doing really bad things.’ The mother found the boys in a field where they were trying to assault her daughter. The girl had been consistent in her evidence at the time, but under cross-examination at the Old Bailey, she retracted. (Not unusual.)

Nonetheless, the jury believed her contemporaneous statements and delivered a guilty verdict.

The implication was that the Home Office campaign had pathologised intimate relationships between young people. Furedi went further, he mounted a defence of pressure: ‘pressure – unwanted or wanted – is integral to every attempt to strike up a sexual relationship.’ It is? How does he know? And should it? Is that how it is for him? Generalising from masculine intuition, he complains that heterosexuality is being criminalised by efforts to clarify what is meant by sexual violence and the question of consent.

The Home Office campaign could hardly bear the weight given it by Furedi: Theresa May, who was then Home Secretary (and later Prime Minister) supported women’s movements’ attempts to improve the criminal justice system’s response to rape. She recognised that the system should not just seek to prosecute perpetrators but to prevent abuse.

Research conducted among teenagers by Bristol University scholars revealed that 90 per cent had been in an intimate relationship, 30 per cent of girls experienced violence from a partner; a sixth of girls felt pressured to have ‘sexual intercourse’ and one in 16 had been raped; one in 17 boys felt pressured into sex.

The Home Office then commissioned a campaign to raise teenagers’ awareness. But the Department of Education and Secretary of State Michael Gove baulked at spreading the campaign to schools – the most obvious location. Despite research showing that publicity didn’t penetrate unless accompanied by action to engage people in the issues, there was no follow-up in schools. May tackled Gove about this, but to little avail. ‘A sorry story,’ confided one of the officials involved.

Mumsnet: Furedi also trashed a parallel campaign by the online parenting network, Mumsnet. It conducted a survey of 1,600 women that confirmed long-standing findings from other research: 10 per cent had been raped, 30 per cent had been sexually assaulted, 80 per cent didn’t report these attacks to the police.

Mumsnet had created a phantom, he said, ‘The process through which this fantasy was concocted is fairly typical of the modern pathologisation of sexual relations. First, an online poll carried out by an advocacy group is miraculously transformed by a journalist into ‘research’. And of course, there is no need to raise any questions about how the poll was conducted or how representative was the sample on which it was based. Then, by the time the story hits the rest of the media, it is yet another case of ‘New research shows…’ – a phrase we hear all the time these days, and which should always set alarm bells ringing. Finally, the 80 per cent claim is magically converted into fact.’

He accused feminist scholars of promoting ‘an epidemic of rape’ by their ‘methodological exaggeration of male violence.’ Not only did they inflate the figures, he said, ‘they constructed survey questions that stripped sexual acts of context and, therefore complication, ‘Since that time, discrete acts of rape have been so denuded of meaning that they have become indistinguishable from the normal ambiguities, tensions and pressures involved in everyday sexual encounters.’

Furedi himself could have inquired into the conduct and methdology of the poll. He only needed to ask Mumsnet. He didn’t. I did.

Mumsnet explained that, of course, surveys among their members are not representative samples, they are Mumsnet users. Mumsnet explained: What had been learned was that ‘official data can miss important aspects, because it’s not asking enough questions, or asking the right questions. In lots of other situations, the official record is simply silent because the research is never undertaken.’

The rape survey and the campaign emerged from online conversations, ‘Mumsnet is a female-dominated site where users are anonymous, and as such it is an environment where women can talk about sex, bodily functions and the nuances of relationships in great detail, and without being told to pipe down. And that has a significant effect on the kinds of conversations that take place.

‘The campaign grew out of an entirely organic set of discussions and surveys that the users themselves carried out. What was really noticeable about those user conversations was the way in which users were led, by other women, towards the naming of their experiences as rape or sexual assault.

‘Incidents that they had previously thought of as ‘just a bit off’ or ‘don’t know whether that was OK’ or ‘I haven’t thought about it for years’ or ‘I suppose I didn’t say no and scream and shout’ became recognised for what they were – rape and/or sexual assault. So, the survey that we carried out was conducted in an atmosphere of heightened awareness among our users.’

Mumsnet explained to me that, ‘the definition of rape and sexual assault to cover all non-consensual sexual activity is challenging, especially for people – not all of them men – who have grown up believing that a bit of slightly forcible slap-and-tickle is nothing to make a fuss about.

‘We have seen users on Mumsnet become extremely angry and upset when other users tell them that the experiences they’re relating – sex instigated while they were asleep, anal sex taking place suddenly or without discussion, condoms being promised but not worn – were non-consensual and thus categorisable as a criminal offence; the women themselves don’t always want to see their experiences and their relationships that way. So, it’s not only Furedi who struggles with this.’

A year after Mumsnet’s survey, it was vindicated by Office for National Statistics figures showing that only around 15% of rapes are reported to the police.

Furedi does not report official statistics, instead he finds the main culprits in a coven of feminist academics and journalists, primarily Mary Koss and Ms Magazine. There is indeed a story here (though Furedi doesn’t tell it) about the politics and technologies of measurement when surveys delve into the most intimate and defended crimes. Feminist researchers had criticised official surveys for failing to address context and complication, as well as official under-reporting.

Koss and her colleague Cheryl Oros published the first rape survey showing that only a quarter of women who had experienced legally-defined rape described it as rape. Her work attracted the attention of Ms magazine, which sponsored a federally-funded survey on rape among college students. Koss was writing in the context of a revolution in rape awareness and research, not least the discovery in the 1980s that official statistics, based on police reports and national crime surveys, did not reach into or record women’s experiences.

The Ms Magazine survey discovered that a quarter of students had been victims of rape or attempted rape, yet only a quarter of those whose assault met the legal definition actually named it as rape. This is the story of ‘one-in-four’ and the entry of ‘date rape’ into the lexicon of sexual politics.

It became a template, regularly revisited and refined, for research on sexual violence. Bonnie Fisher and Francis Cullen, writing in 2000 about the development of measurement, ‘Measuring the Victimization of Women: Evolution of Current Controversies and Future Research’, comment that, ‘What they developed, therefore, was systems of criteria, measurement, and vocabulary that were sufficiently subtle to cope with women’s reticence, shame and ambivalence about their experience, particularly in the context of entrenched social scripts about sex and violence.

‘Researchers have come to realise that conceptually defining and then operationalising sexual victimisation are complicated and, to a degree, imperfect enterprises—especially when deciding when an unwanted sexual advance crosses the line from imprudence to criminal behaviour.’

They also had to anticipate and address the inevitable criticism that as activist academics they would find what they were looking for. The methodological challenges ‘opened the way for conservative commentators to charge that the supposed “epidemic of rape” is an invention of feminist scholars.’

Scholars and pundits remained divided. Was the perceived extent of rape a ‘constructed’ or real public health and justice problem? What were the linguistic and psychological implications of these dissonant narratives?

After decades of experimentation, surveys have become more refined, yet ‘Letting a woman tell her own story’ doesn’t necessarily resolve the discrepancies: half of women describing acts legally-defined as rape still did not consider it to be rape. It is when acts are described explicitly that rape estimates increase.

Bonnie Fisher comments that how people construct incidents ‘may be a large, not a small, source of “measurement error” in how people respond to questions.’ The implications are heavy, ‘For virtually any other crime (e.g., larceny, burglary, robbery), the idea of measuring objective, rather than socially constructed, reality would raise barely a ripple of concern.’