Raph Koster's Blog

November 16, 2025

Looking back at a pandemic simulator

It’s been six years now since the early days of the Covid pandemic. People who were paying super close attention started hearing rumors about something going on in China towards the end of 2019 — my earliest posts about it on Facebook were from November that year.

Even at the time, people were utterly clueless about the mathematics of how a highly infectious virus spread. I remember spending hours writing posts on various different social media sites explaining that the Infection Fatality Rates and the R value were showing that we could be looking at millions dead. People didn’t tend to believe me:

“SEVERAL MILLION DEAD! Okay, I’m done. No one is predicting that. But you made me laugh. Thanks.”

You can do the math yourself. Use a low average death estimate of 0.4%. Assume 60% of the population catches it and then we reach herd immunity (which is generous):

328 million people in the US.60% of that is 196 million catch it.0.4% of that is 780,000 dead.But that’s with low assumptions…

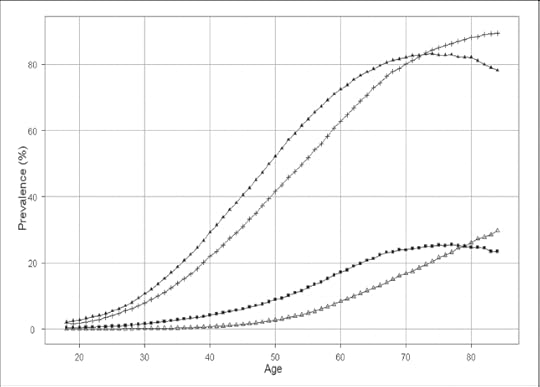

Graph showing fatality rates with and without comorbidities, by age.

Graph showing fatality rates with and without comorbidities, by age.It was like typing to a wall. In fact, it’s pretty likely that it still is, since these days, the discourse is all about how bad the economic and educational impact of lockdowns was — and not about the fact that if the world had acted in concert and forcefully, we could have had a much better outcome than we did. The health response was too soft, the lockdown too lenient, and as a result, we took all the hits.

Of course, these days people also forget just how deadly it was and how many died, and so on. We now know that the overall IFR was probably higher than 0.4%, but very strongly tilted towards older people and those with comorbidities. We also now know that herd immunity was a pipe dream — instead we managed to get vaccines out in record time and the ordinary course of viral evolution ended up reducing the death rate until now we behave as if Covid is just a deadlier flu (it isn’t, that thinking ignores long-term impact of the disease).

The upshot: my math was not that far off — the estimated toll in the US ended up being 1.2 to 1.4 million souls, and worldwide it’s estimated as between 15 and 28.5 million dead. Plenty of denial of this, these days, and plenty of folks blaming the vaccines for what are most likely issues caused by the disease in the first place.

Anyway, in the midst of it all, tired of running math in my spreadsheets (yeah, I was tracking it all in spreadsheets, what can I say?), I started thinking about why only a few sorts of people were wrapping their heads around the implications. The thing they all had in common was that they lived with exponential curves. Epidemiologists, Wall Street quants, statisticians… and game designers.

Could we get more people to feel the challenges in their bones?

The design sketch

The design sketchSo… I posted this to Facebook on March 24th, 2020:

Three weeks ago I was idly thinking of how someone ought to make a little game that shows how the coronavirus spreads, how testing changes things, and how social distancing works.

The sheer number of people who don’t get it — numerate people, who ought to be able to do math — is kind of shocking.

I couldn’t help worrying at it, and have just about a whole design in my head. But I have to admit, I kinda figured someone would have made it by now. But they haven’t.

It’s not even a hard game to make.

Little circles on a plain field. Each circle simply bounces around.

They are generated each with an age, a statistically real chance of having a co-morbid condition (diabetes, hypertension, immunosuppressed, pulmonary issues…), and crucially, a name out of a baby book.

They can be in one of these states:

healthyasymptomatic but contagioussymptomaticseverecriticaldeadrecoveredIn addition, there’s a diagnosed flag.

We render asymptomatic the same as healthy. We render each of the other states differently, depending on whether the diagnosed flag is set. They show as healthy until dead, if not diagnosed. If diagnosed, you can see what stage they are in (icon or color change).

The circles move and bounce. If an asymptomatic one touches a healthy one, they have a statistically valid chance of infecting.

Circles progress through these states using simple stats.

70% of asymptomatic cases turn symptomatic after 1d10+5 days. The others stay sick for the full 21 days.Percent chance of moving from symptomatic to severe is based on comorbid conditions, but the base chance is 1 in 5 after some amount of days.Percent chance of moving from severe to critical is 1 in 4, modified by age and comorbidities, if in hospital. Otherwise, it’s double.Percent chance of moving from critical to dead is something like 1 in 5, modified by age and comorbidities, if in hospital. Otherwise, it’s double.Symptomatic, severe, and critical circles that do not progress to dead move to ‘recovered’ after 21 days since reaching symptomatic.Severe and critical circles stop moving.We track current counts on all of these, and show a bar graph. Yes, that means players can see that people are getting sick, but don’t know where.

The player has the following buttons.

Hover on a circle, and you see the circle’s name and age and any comorbidities (“Alison, 64, hypertension.”)Test. This lets them click on a circle. If the circle is asymptomatic or worse, it gets the diagnosed flag. But it costs you one test.Isolate. This lets them click on a circle, and freezes them in place. Some visual indicator shows they are isolated. Note that isolated cases still progress.Hospitalize. This moves the circle to hospital. Hospital only has so many beds. Clicking on a circle already in hospital drops the circle back out in the world. Circles in hospital have half the chance or progressing to the next stage.Buy test. You only have so many tests. You have to click this button to buy more.Buy bed. You only have this many beds. You have to click this button to buy more.Money goes up when circles move. But you are allowed to go negative for money.Lockdown. Lastly, there is a global button that when pressed, freezes 80% of all circles. But it gradually ticks down and circles individually start to move again, and the button must be pressed again from time to time. While lockdown is running, it costs money as well as not generating it. If pressed again, it lifts the lockdown and all circles can move again.The game ticks through days at an accelerated pace. It runs for 18 months worth of days. At the end of it, you have a vaccine, and the epidemic is over.

Then we tell you what percentage of your little world died. Maybe with a splash screen listing every name and age of everyone who died. And we show how much money you spent. Remember, you can go negative, and it’s OK.

That’s it. Ideally, it runs in a webpage. Itch.io maybe. Or maybe I have a friend with unlimited web hosting.

Luxury features would be a little ini file or options screen that lets you input real world data for your town or country: percent hypertensive, age demographics, that sort of thing. Or maybe you could crowdsource it, so it’s a pulldown…

Each weekend I think about building this. So far, I haven’t, and instead I try to focus on family and mental health and work. But maybe someone else has the energy. I suspect it might persuade and save lives.

Notes on the design

Notes on the designSome things about this that I want to point out in hindsight.

At the time that I posted, I could tell that people were desperately unwilling to enter lockdown for any extended period of time; but “The Hammer and the Dance” strategy of pulsed lockdown periods was still very much in our future. I wanted a mechanic that showed population non-compliance.There was also quite a lot of obsessing over case counts at the time, and one of the things that I really wanted to get across was that our testing was so incredibly inadequate that we really had little idea of how many cases we were dealing with and therefore what the IFR (infection fatality rate) actually was. That’s why tests are limited in the design sketch.I was also trying to get across that money was not a problem in dealing with this. You could take the money value negative because governments can choose to do that. I often pointed out in those days that if the government chose, it could send a few thousand dollars to every household every few weeks for the duration of lockdown. It would likely have been less impact to the GDP and the debt than what we actually did.I wanted names. I wanted players to understand the human cost, not just the statistics. Today, I might even suggest that an LLM generate a little biography for every fatality.Another thing that was constantly missed was the impact of comorbidities. To this day, I hear people say “ah, it only affected the old and the ill, so why not have stayed open?” To which I would reply with:Per the American Heart Association, among adults age 20 and older in the United States, the following have high blood pressure:

For non-Hispanic whites, 33.4 percent of men and 30.7 percent of women.For non-Hispanic Blacks, 42.6 percent of men and 47.0 percent of women.For Mexican Americans, 30.1 percent of men and 28.8 percent of women.

Per the American Diabetes Association,

34.2 million Americans, or 10.5% of the population, have diabetes.Nearly 1.6 million Americans have type 1 diabetes, including about 187,000 children and adolescentsPer studies in JAMA,

4.2% of of the population of the USA has been diagnosed as immunocompromised by their doctorNext, realize that because the disease spreads mostly inside households (where proximity means one case tends to infect others), this means that protecting the above extremely large slices of the population means either isolating them away from their families, or isolating the entire family and other regular contacts.

People tend to think the at-risk population is small. It’s not.

The response, for Facebook, was pretty surprising. The post was re-shared a lot, and designers from across the industry jumped in with tweaks to the rules. Some folks re-posted it to large groups about public initiatives, etc.

There was also, of course, plenty of skepticism that something like this would make any difference at all.

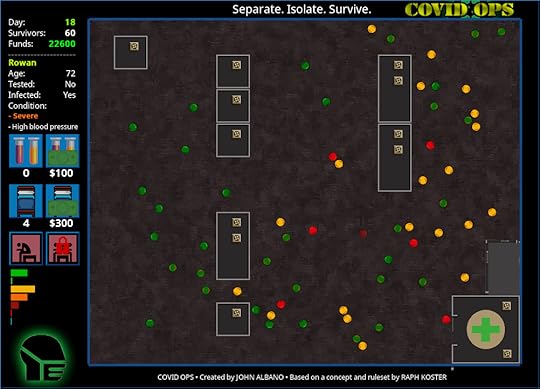

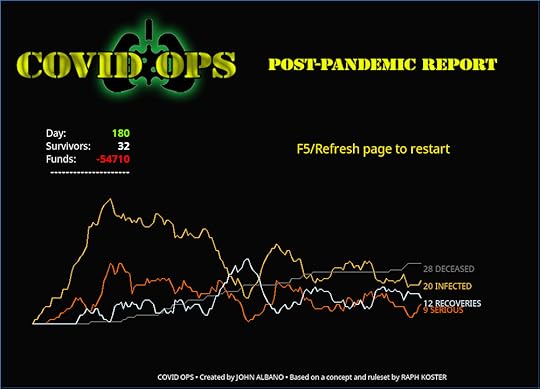

Screenshot of Covid Ops, by John AlbanoTeams take it up

Screenshot of Covid Ops, by John AlbanoTeams take it upThe first to take up the challenge was John Albano, who had his game Covid Ops up and running on itch.io a mere six days later. You can still play it there!

Stuck in the house and looking for things to do. Soooo, when a fellow game dev suggested a game idea and basic ruleset along with “I wish someone would make a game like this,” I took that as a challenge to try. Tonight (this morning?), the first release of COVID OPS has been published.

John’s game was pretty faithful to the sketch. You can see the comorbidities over on the left, and the way the player has clicked on 72 year old Rowan — who probably isn’t going to make it. As he updated it, he added in more detailed comorbidity data, and (unfortunately, as it turns out) made it so that people were immune after recovering from infection. And of course, like the next one I’ll talk about, John made a point of including real world resource links so that people could take action.

By April 6th, another team led by Khail Santia had participated in Jamdemic 2020 and developed the first version of In the Time of Pandemia. He wrote,

The compound I stay at is about to be cordoned. We’ve been contact-traced by the police, swabbed by medical personnel covered in protective gear. One of our housemates works at a government hospital and tested positive for antibodies against SARS-CoV-2.

The pandemic closes in from all sides. What can a game-maker do in a time like this?

I’ve been asking myself this question since the beginning of community quarantine. I’m based in Cebu City, now the top hotspot for COVID-19 in the Philippines in terms of incidence proportion.

This game would go on to be completed by a fuller team including a mathematical epidemiologist, and In the Time of Pandemia eventually ended up topping charts on Newgrounds when it launched there in July of 2020.

This game went viral and got a ton of press across the Pacific Rim. The team worked closely with universities and doctors in the Philippines and validated all the numbers. They added local flavor to their levels representing cities and neighborhoods that their local players would know.

Gregg Victor Gabison, dean of the University of San Jose-Recoletos College of Information, Computer & Communications Technology, whose students play-tested the game, said, “This is the kind of game that mindful individuals would want to check out. It has substance and a storyline that connects with reality, especially during this time of pandemic.”

Not only does the game have to work on a technical basis, it has to communicate how real a crisis the pandemic is in a simple, digestible manner.

Dr. Mariane Faye Acma, resident physician at Medidas Medical Clinic in Valencia, Bukidnon, was consulted to assess the game’s medical plausibility. She enumerated critical thinking, analysis, and multitasking as skills developed through this game. “You decide who are the high risks, who needs to be tested and isolated, where to focus, [and] how much funds to allocate….The game will make players realize how challenging the work of the health sector is in this crisis.”

“Ultimately, the game’s purpose is to give players a visceral understanding of what it takes to flatten the curve,” Santia said.

Aftermath

Aftermath

I think most people have no idea that any of this happened or that I was associated with it. I only posted the design sketch on Facebook; it got reshared across a few thousand people. It wasn’t on social media, I didn’t talk about it elsewhere, and for whatever reason, I didn’t blog about it.

I have had both these games listed on my CV for a while. Oh, I didn’t do any of the heavy lifting… all credit goes to the developers for that. There’s no question that way more than 95% of the work comes after the high-level design spec. But both games do credit me, and I count them as games I worked on.

A while back, someone on Reddit said it was pathetic that I listed these. I never quite know what to make of comments like that (troll much?!?).

No offense, but I’m proud of what a little design sketch turned into, and proud of the work that these teams did, and proud that one of the games got written up in the press so much; ended up being used in college classrooms; was vetted and validated by multiple experts in the field; and made a difference however slight.

Peak Covid was a horrendous time. Horrendous enough that we have kind of blocked it from our memories. But I lost friends and colleagues. I still remember. Back then I wrote,

This is the largest event in your lifetime. It is our World War, our Great Depression. We need to rise the occasion, and think about how we change. There is no retreat to how it used to be.

There is only through.

A year later, the vaccine gave us that path through, and here we are now.

But as I write this, we have the first human case of H5N5 bird flu; it was only a matter of time.

Maybe these games helped a few people get through it all. They were played by tens of thousands, after all. Maybe they will help next time. I know that the fact that they were made helped me get through, that making them helped John get through, helped Khail get through — in his own words:

In the end, the attempt to articulate a game-maker’s perspective on COVID-19 has enabled me to somehow transcend the chaos outside and the turmoil within. It’s become a welcome respite from isolation, a thread connecting me to a diversity of talents who’ve been truly generous with their expertise and encouragement. As incidences continue to rise here and in many parts of the world, our hope is that the game will be of some use in showing what it takes to flatten the curve and in advocating for communities most in need.

So… at minimum, they made a real difference to at least three people.

And that’s not a bad thing for a game to aspire to.

November 3, 2025

Game design is simple, actually

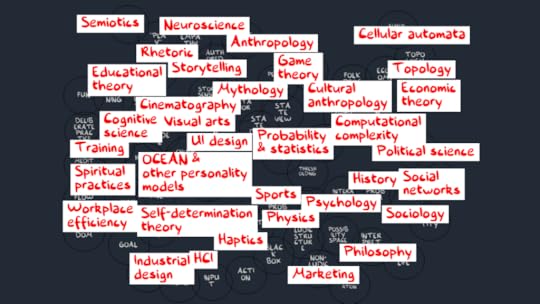

So, let’s just walk through the whole thing, end to end. Here’s a twelve-step program for understanding game design.

One: Fun

One: FunThere are a lot of things people call “fun.” But most of them are not useful for getting better at making games, which is usually why people read articles like this. The fun of a bit of confetti exploding in front of you, and the fun of excruciating pain and risk to life and limb as you free climb a cliff are just not usefully paired together.

In Theory of Fun I basically asserted that the useful bit for game designers was “mastery of problems.” That means that free climbing a cliff is in bounds even though it is terrifying and painful. Which given what we already said, means that you may or may not find the activity fun at the time! Fun often shows up after an activity.

There’s neuropsych and lots more to go with that, and you can go read up on it if you want.

Anything that is not about a form of problem-solving is not going to be core to game systems design. That doesn’t mean it’s not useful to game experience design, or not useful in general.

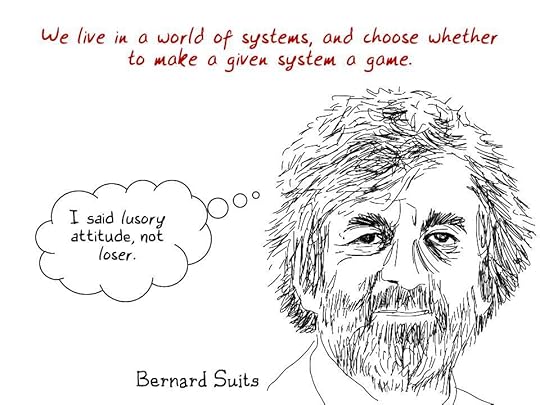

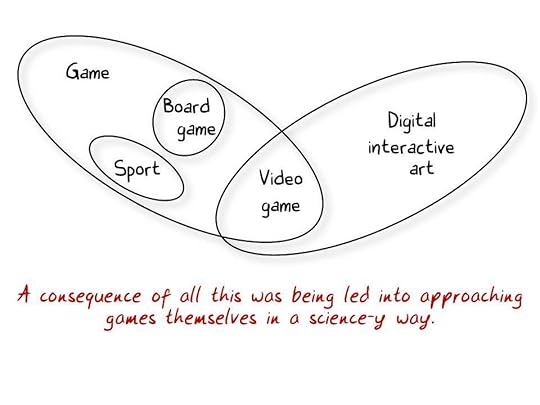

Also, in case it isn’t obvious – you can make interactive entertainment that is not meant to be about fun. You can also just find stuff in the world and turn it into a game! You can also look at a game and choose not to treat it as one, and then it might turn into real work (this is often called “training”).

This rules out the bit of confetti. A game being made of just throwing confetti around with nothing else palls pretty quick.

Bottom line: fun is basically about making progress on prediction.

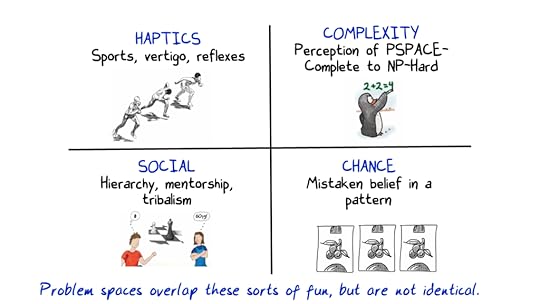

Two: Problems and toys

Two: Problems and toys

There are a lot of types of problems in the world. It is really important to understand that you have to think about problems games can pose as broadly as possible. A problem is anything you have to work to wrap your head around. A good movie poses problems too, that’s why you end up thinking about it long after.

You can go look at theorists as diverse as Nicole Lazzaro, Roger Caillois, or Mark LeBlanc for types of fun. You’ll find they’re mostly types of problems, not types of fun. “I enjoy the types of problems that come from chance” or “I enjoy the types of problems that come from interacting with others” or whatever.

This is not a bad thing. This is what makes these lists useful. Your game mechanics are about posing problems, so knowing there’s clumps of problem types is very useful.

In the end, though, a problem is built out of a set of constraints. We call those rules, usually. It also, though, has a goal. Usually, if we come across a set of rules with no problem, we just play with it, and call it a toy.

Building toys is hard! Arriving at those rules and constraints to define a nice chewy problem is very challenging. You can think of a toy as a problematic object, a problem that invites you to play with it.

On the other hand, it’s not hard to turn a toy into a game, and people do it all the time. All you have to do is invent a goal. We shouldn’t forget that players do so routinely.

Building a toy is an excellent place to start designing a game.

Bottom line: we play with systems that have constraints and movement, and we stick goals on them to test ourselves.

Three: Prediction and uncertainty

Three: Prediction and uncertaintyGames are machines built around uncertainty. Almost all games end by turning an uncertain outcome into a certain one. There’s a problem facing you, and you don’t know if you can overcome it to reach that goal. Overcoming it is going to be about predicting the future.

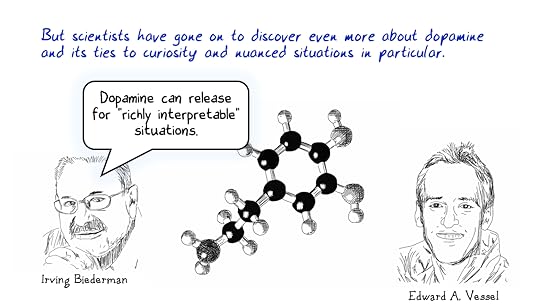

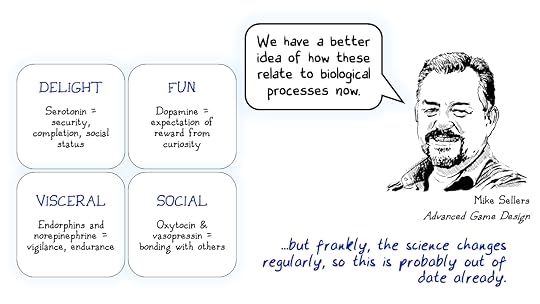

If there’s one thing that good games and good stories have in common, it’s about being unpredictable as long as possible. (This is also where dopamine comes in, it’s tied to prediction; but it’s complicated and nuanced).

If a problem basically has one answer, we often call it a puzzle. There’s not a lot of uncertainty built into a binary structure. You can stack a bunch of puzzles one on top of the other and build a game out of them (which then introduces uncertainty into the whole), but a singular puzzle isn’t likely to be called that by most people.

It happens quite often that we used to think something was a game, and it turned out it was actually a puzzle. Mathematicians call that “solving the game.” They did it to Connect Four – and you did it to tic-tac-toe, when you were little.

Good problems for games therefore all have the same characteristics:

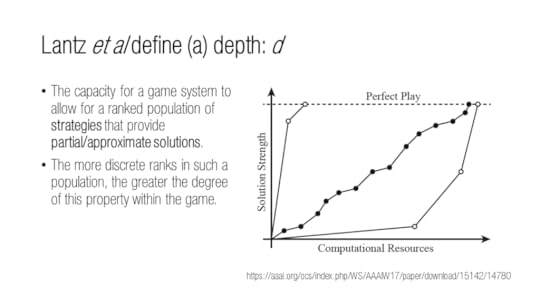

They need to have answers that evolve as you dig in more – so they need to have depth to them. Your first answer should only work for a while. There might be many paths to the solution, too. This is why so many games have a score – it helps indicate how big a spread of solutions there are!They need to have uncertain answers. (When you’re little, this universe is a lot larger than it is when you’re older – peek-a-boo is uncertain up to a certain point!).The problem should be something that can show up in a lot of situations.

A lot of very good problems seem stupidly simple, but have depths to them. Math ones, like “what’s the best path to cross this yard?” but also story ones like “For sale: baby shoes, never worn.”

I recently watched a video that included the statement that “picking up sticks” is not a useful loop. Picture a screen with a single stick in the middle. The problem posed is to move the cursor over it and click it. Once you do it, you get to do it again.

Guess what? The original Mac shipped with games that taught you how to move a mouse and click things. Once upon a time, mousing was a skill that was challenging; for all I know, you have grandparents who still have trouble with it. For them, it has uncertainty. For you, probably, it doesn’t.

Bottom line: the more uncertainty, indeterminacy, ambiguity in your game, the more depth it will have.

Four: Loops

Four: LoopsNow, imagine that the stick pops to a random location each time. Better, yes?

The core of a loop is a problem you encounter over and over again. “How do I get the next one?” But something needs to be pushing back, that’s what makes it an interesting problem and is usually what takes it past being a puzzle. I like to say “in every game, there is an opponent.” Even it’s just physics.

People talk about the core loop of a game. But there’s really two types of loops.

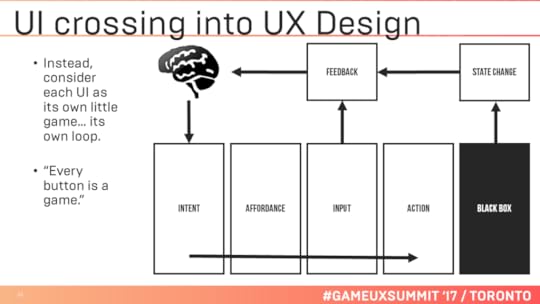

One is what we might think of as the operational loop. This is the loop between you and the problem, it is how you interact with it. You look at it. You form a hypothesis. You poke the problem. You see a result. Maybe it was success, and you grabbed the stick. Maybe it was failure. Maybe it was partial success. You update your hypothesis so you can decide what to do next.

The second loop is really your progression loop but is better thought of as a spiral. It’s what people usually mean when they say “a game loop.” They mean picking up the stick over and over. I say it’s a spiral, because clicking on the same stick in the middle of the screen over and over is not usually how we design games. That would actually be repeatedly doing the same puzzle.

Instead, we move the stick on the screen each time, and maybe give you a time limit. Now there’s something you’re pushing against, and there’s a skill to exercise and patterns to try to recognize. Far more people will find this a diverting problem for a while. It’s a better game. It’ll get even better if there are reasons why the stick appears in one place versus another, and the player can figure them out over time.

This matters: the verbs are in a loop. “Pick up,” over and over. But the situation isn’t. And you are learning how to reduce uncertainty of the outcome: move the mouse here and click, next move it there. That’s why it is a spiral: it is spiraling to a conclusion. It’ll be fun until it’s predictable.

You can think of the operational loop as how you turn the wheel, and the situations as the road you roll over. A spot on the wheel makes a progression spiral as you move. One machine, many situations — we call these rules mechanics for a reason.

Bottom line: players need to understand how to use the machine, and the point is to gradually infer how it works by testing it against varied situations.

Five: Feedback

Five: FeedbackYou can’t learn and get better unless you get a whole host of information.

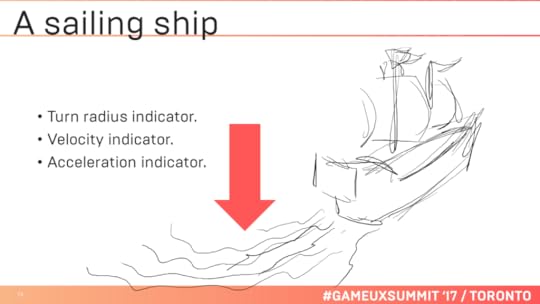

You need to know what actions – we usually call them verbs — are even available to you. There’s a gas pedal.You need to be able to tell you used a verb. You hear the engine growl as you press the pedal.You need to see that the use of the verb affected the state of the problem, and how it changed. The spedometer moved!You need to be told if the state of the problem is better for your goal, or worse. Did you mean to go this fast?

You need to know what actions – we usually call them verbs — are even available to you. There’s a gas pedal.You need to be able to tell you used a verb. You hear the engine growl as you press the pedal.You need to see that the use of the verb affected the state of the problem, and how it changed. The spedometer moved!You need to be told if the state of the problem is better for your goal, or worse. Did you mean to go this fast?There are fancy names for each of these, and you can go learn them all. Everything from “affordance” and “juice,” to terms like “state space” and “perfect information” and very confusing contradictory uses of the words “positive” and “negative” paired with the word “feedback.”

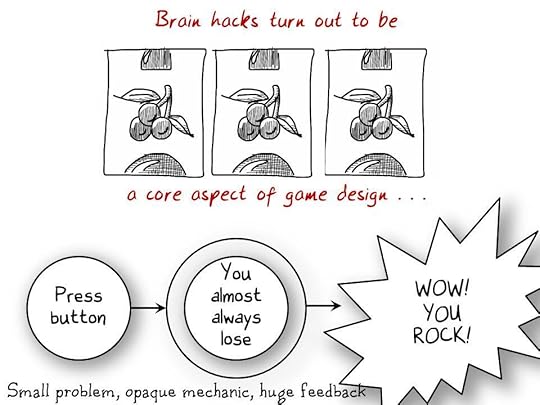

Feedback in general can, and should be, delightful. That means it’s where you get to use all those forms of fun that I threw away at the beginning. It can be surprising. It can be a juicy multimedia extravaganza. It can be a deeply affecting tragic cutscene that advances the game story.

If you have too little feedback, players cannot go around the interaction loop. Picture Tetris if the piece you drop is invisible until it lands.

If you have bad feedback, players cannot go around the learning loop either. Picture Tetris if sometimes your score goes down when you complete a line and sometimes it goes up. You can’t draw any conclusions about what the problem in the way of the goal actually is, in that crappy version of Tetris. Feedback needs to act as a reward to help you draw conclusions.

But there’s a third mistake: you can supply a gorgeous and compelling set of feedback and not actually have a real problem under there. At minimum you’re making shallow entertainment. At worst, you are building exploitative entertainment.

People will be willing to go along with pretty simple and pretty familiar problems as long as the feedback is great.

Bottom line: show what you can do, that you did it, what difference it made, and whether it helped.

Six: Variation and escalation

Six: Variation and escalation

If you are trying to design and are thinking of a specific problem scenario you are not doing game systems design. You are doing level design. “How to multiply numbers” is a problem. “What is 6 x 9” is not a problem, it’s content.

Now consider the game of Snake, or Pac-Man. They are also games where the core loop is picking up a stick. The difference is that something is an obstacle to you picking up the stick: you get longer when you pick up the stick, and can crash into yourself. You have to avoid ghosts as you gather the stick.

How long you are in Snake is a different situation. Where the apple to eat is located is a different situation. To be specific, you have the same problem in different topology. Where you are relative to the ghosts, and which dots are left, and what directions you can go in the maze are different situations in Pac-Man.

You want the verbs you use in the loop to end up confronting many many situations. If your verb can’t, your core loop is probably bad. Your core problem (aka your core game mechanic) is probably shallow.

What you want is to be able to throw increasingly complex situations at the player. That’s how they climb the learning ladder. Ideally, they should arrive at interim solutions (lots of words for that, too: heuristics, strategies) that later stop working.

Pac-Man actually got solved, by the way! That’s why Ms. Pac-Man was invented. Sometimes, the way to escalate is to change the rules, and that’s what Ms. Pac-Man did. It did it by adding randomness, and in fact using randomness is one of the biggest (and oldest) ways to create situation variation in games.

Bottom line: escalate the situations so that theories can be tested, refined, and abandoned.

Seven: Pacing and balance

Seven: Pacing and balanceSince we can put all this this down very much to problem solving and learning and mastery, it means we can steal a whole bunch of knowledge from other fields.

People learn best when they can experiment iteratively, which we also call “practicing.” That’s why loops make sense. There’s a lot of science out there about how to train, how to practice (and also a lot of educational theory that overlaps hugely), and your game will be better if it follows some of those guidelines.

People learn best when the problem they are tackling is right past the edge of what they can do. If it’s too far past that edge, they may not even be able to perceive the problem in the first place! And if the reverse is true and they see a solution instantly, they’ll either be bored, or they might just do that over and over again and never develop any new strategies and not progress.

There’s an optimal pacing shape. It looks just like what you see in your literature textbooks when they diagram tension, or whatever: sort of like a rising sine wave. You start slow, then speed up, hit a peak challenge, then back off a bit, give a breather that falls back but not all the way, then speed up… we have conventions for what to put at those peaks (bosses!). But what matters is the shape of the curve.

You need to structure your game so that you push players up. They might need to climb the curve at different paces, which is why you might also have difficulty sliders. They might not be capable of getting all the way to the top, and that’s okay.

You also need to pace to allow room for everything that isn’t mastering the problem — such as having fun with friends socially. But at the same time, things to do in the game need to come along at the right pace too!

Bottom line: Vary intensity and pressure, give players a chance to practice and moments to be tested.

Eight: Games are made of games

Eight: Games are made of gamesRemember the game about clicking on a stick that appeared at a random location on screen? That’s also a rail shooter. You move the mouse and click on a spot in 2d space. Which is also not that different from an FPS — only now you move the camera, not the cursor.

Almost no games are made of only one loop. Instead, we chain loops together – complete loop A, and it probably outputs something that may serve as a tool or constraint on a different loop.

An FPS has the problem of moving the camera (instead of the mouse) to click on the stick. It also has a loop around moving around in 3d space. Moving around is actually made of several loops, probably, because it may be made of running and jumping and spatial orientation. Those are all problem types!

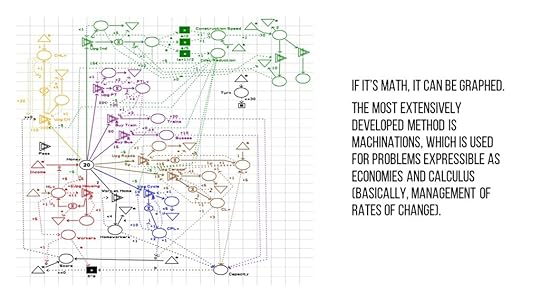

We speak sometimes of value chains: that’s where one loop outputs something to the next loop. We speak also of game economies, which is what happens when loops connect in non-linear ways, more like a web. This is not the sort of economy where you are simulating money or commerce. Instead it’s a metaphor for stocks and flows and other aspects of actual system dynamics science. In this view, your hit points is a “stock” or, if you like, a “currency” you spend in a fight.

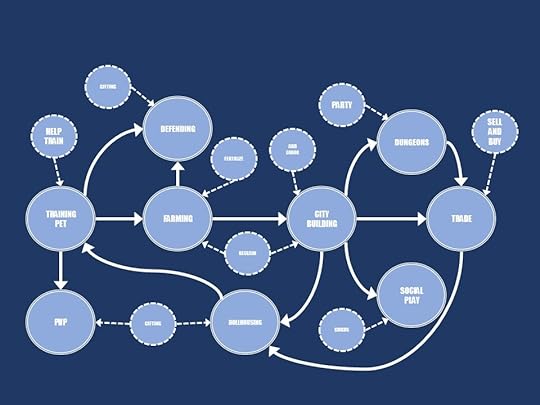

Games nest fractally, they web into complex economies, and they unroll chains of linked loops. That’s why they can be diagrammed in a multitude of ways.

At heart though, you can decompose them all into those elemental small problems, each with an interaction loop and a learning loop centered on that problem.

Bottom line: build small problems into larger webs, and map them so you understand how they connect.

Nine: Actual systems design

Nine: Actual systems design

The common question is “okay, so how do I design a problem like that?” And that is indeed the unique bit in games, because the other items here are common to lots of other fields.

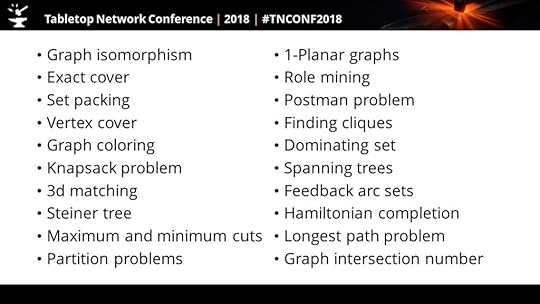

The list of possible problems is, as mentioned, enormous. This is a big rabbit hole. And once you consider that you can stack, web, and otherwise interlink problems, it means that there’s a giant composable universe of games (and game variants) to create.

Just bear in mind that because of varied tastes and experience, the diversity of the set of problems you pose is going to affect who wants to play your game.

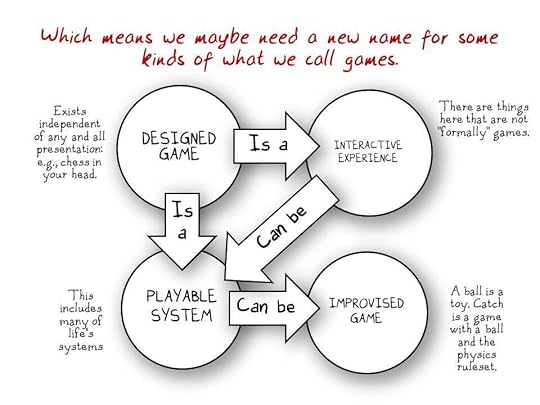

There are basically a set of categories of problems that we know work, and this is the absolute simplest version of them:

Mathematically complex puzzlesFiguring out how other humans thinkMastering your body and brainThese break down into a ton of sub-problems, but there are less than you think, and you can actually find lists of them. The hard part is that often they each seem so small and trivial that we don’t think of them as actually being worth looking at!

They are also often in disguise: the problem behind where a tossed ball will land, and the problem of how much fuel you have left in your car if you keep driving at this speed, and the problem of when your hit points will run out given you have a poison status effect on you are the same thing.

But the more of them you as a designer have wrapped your head around, the more you can combine. And you’ll find them very plastic and malleable. In fact, you could almost make a YouTube video about each one.

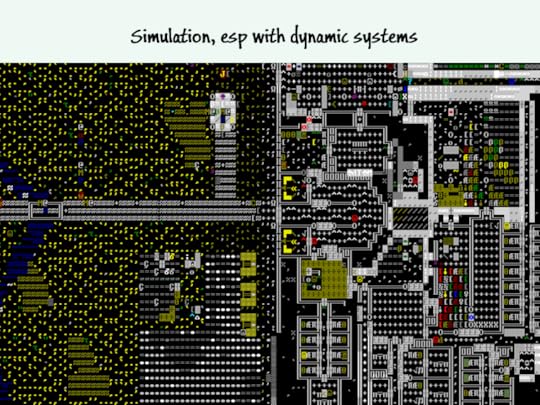

So where do you get them? Steal them. Other games, sure, but also, the world is full of systems that pose tough problems. You can grab them and reskin them.

Bottom line: not every mechanic has been invented, but a ton have. Build your catalog and workbench.

Ten: Dressing and experience

Ten: Dressing and experience

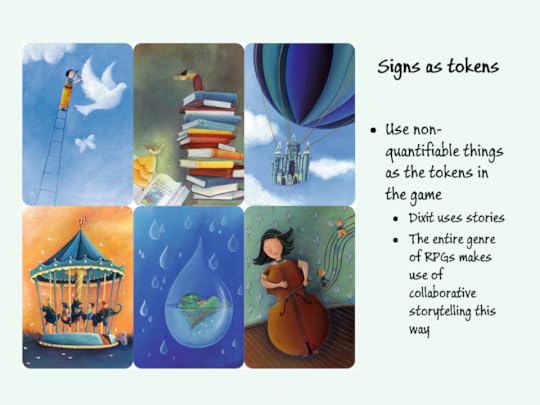

In the end, the feedback layer of a game is everything about how you present it. The setting, the lore, the audio, the story, the art…

How you dress up the problems can change everything about how the player learns from it, and how they perceive the problem. The exact same underlying problem can be as different as picking up sticks or shooting someone in the face, or as mentioned, the calculus problem of estimating the trajectory of a variable in a system of rates of change (the ball, the car and its gas, the hit points and poison) might be the same but dressed extraordinarily differently.

When you think about how you dress up the problems, you are in the realm of metaphor. You are engaging in painting, poetry, and music composition, and rhetoric, and the bardic tradition, and all that other humanities stuff.

This is a giant and deep universe for you as a designer to dive into. A lot of this stuff gets called “game design,” but then again, we also often say that a given game designer is a frustrated moviemaker, too.

It is really easy to create an experience that clashes with the underlying problems it is teaching. There are fancy critical terms for this. You also need to be very conscious about whether you are building your game so that you are telling the player a story, or so that the player can tell stories with your game.

So the takeaway should be: this stuff is deeply, deeply synergistic with the “game system” stuff that this article is about, but they are not the same thing. And games is not the best place to learn how to do these things.

Those other fields have much longer traditions and loads of expertise and lessons. They won’t all apply to the issue of “how do I best dress up this collection of problems” but most of them will.

It does not frickin’ matter if you start out wanting to make interesting problems, or if you start out wanting to provide a cool experience. You are going to need to do both to make the game really good.

Bottom line: game development is a compound art form. You can go learn those individual arts and the part unique to games.

Eleven: Motivations

Eleven: MotivationsResearchers have done a ton of studying “why people play games.” This gets called “motivations.”

Motivations are basically about people’s personal taste for groups of problems and how those problems are presented, and characteristics of those problems and the situations in which you find them. Some people like problems where you destroy stuff. Others like problems where you bond with others. Some have trouble trusting other people. Others want to cooperate.

Not everyone likes the same sorts of problems or the same sorts of dressings. Some of this is down to personality types, some of it is down to social dynamics, how they were raised, what their local culture is like, what trauma they have had, and countless other psychological things. That’s why one fancy term for this is psychographics.

The big thing is, it’s not enough that the problems need to not be obvious to you, and also not be baffling to you. They also have to be interesting to you. What problems fit in that range is going to depend entirely on who you are, what your life experiences have been, what skills you have, and even what mood you are in.

Picking motivations and selecting problems based on them is a great way to design. But motivations are not the same thing as fun. They’re a filter, useful in marketing exercises and in building your game pillars (which is an exercise in focus and scope).

Scientists have spent a bunch of time surveying tons of people and have arrived at all sorts of conclusions that map people onto reasons to play and from there onto particular problems.

If you start with motivations, then you can go from there to types of problems, types of experience, and even player demographics. And then, if you want problems that are about interacting with people, well, there’s lists of those. If you want problems that are about managing resources, or solving math issues, there’s lists of those too.

Bottom line: no game is for everyone, so you will make better games if you know who you are posing problems for.

Twelve: It’s simple, but not

Twelve: It’s simple, but notI run into game developers who do not understand the above eleven steps all the time. And understanding all eleven is more valuable than building expertise in just one, because they depend on one another. This is because getting any one of the eleven wrong can break your game. The real issue is that each of these eleven things is often multiple fields of study. And yeah, you do need to become expert in at least one.

To pick one example, some of us have been working out the rule set for how you can link loops into a larger network of problems for literally over twenty years.

Others have spent their entire career doing nothing but figuring out how best to provide just the affordances part of feedback.

So game design is pretty simple. But the devil is in details that are not very far below the surface. It’s fairly easy to explain why something is fun for an given audience. It is much harder to build something new that is fun for an arbitrary person. That said, every single one of those fields has best practices, and they are mostly already written down. It’s just a lot to learn.

Put another way — every single paragraph in this essay could be a book. Actually, probably already is several.

Bottom line: each of these topics is deep, but you want a smattering of all of them.

Some of you may not like this deconstructive view on how games are designed. That’s okay. Personally, I find it best to poke and prod at a problem, like “how do I get better at making games?” and treat it as a game. And that’s what I have done my whole career. The above is just my strategy guide. Someone else will have different strategies, I guarantee it.

But I also guarantee that if you get better at the above twelve things, you will get better at making games. This is a pragmatic list. And it will be helpful for making narrative games, puzzle games, boardgames, action games, RPGs, whatever. I breezed through it, but there are very specific tools you can pick up underneath each of these twelve things. It really is that simple, but also that hard, because that’s a frickin’ long list if you want to actually dive into each of the twelve.

What that also means is that people designing games fail a lot at it. You might say, “can’t they just do the part they know how to do, and therefore predictably make good games?”

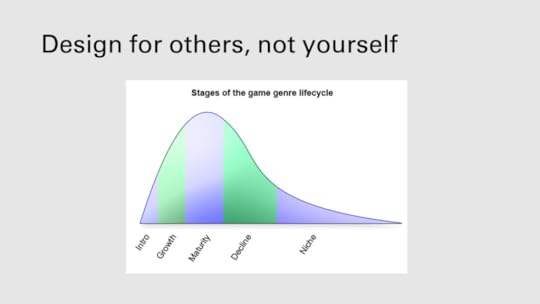

No, because players learn along with the designers. If you just make the same game, the one you know how to make, the players get bored because it’s nothing but problems they have seen before and already have their answers to. Sometimes, they get so bored that an entire genre dies.

And if you instead make it super-complicated by adding more problems, it might dissolve into noise for most people. Then nobody plays it. And then the genre dies too!

Game designers will routinely fail at making something fun. When the game of making games is played right, it is always right outside the edge of what the designers know how to do.

That’s where the fun lives, not just for the designer, but also for their audience.

That’s it, the whole cheat sheet. That’s it.

Hope it helps.

October 29, 2025

Stars Reach visual upgrades

For months now, we have been working on a big overhaul to the visuals in Stars Reach. This has involved redoing most of the shaders in the entire game, and going back and retouching every asset. We started by redoing all the plant life and flora, and we have hundreds of those assets that had to be redone.

Further, they all need to grow, change in response to seasons, be able to catch fire and burn, freeze, shed leaves and die, and so on. We don’t pre-design our biomes; we derive them on the fly from the simulation based on the environmental conditions. The right plants grow in the right places based on the temperature and the humidity and the soil types. (Yes, we even have a dozen soil types).

All that means that every tree you see in the game grew there, and propagates across the landscape just like real plants. Seeds fall and grow into trees, forest fires happen and so on.

Further, everything in the landscape itself can be changed. Mountains can be flattened, roads built, and so on. What you see in this screenshot and the videos is all dynamic, evolving, and modifiable by players. In this picture, that cliff face can not just be climbed, it can be melted into lava. You can see an ice rim along the top — pour water on the ground there, and it freezes and you will skate on the resulting ice. We are finally at a place where we do not need to compromise on the visual quality in order to deliver the simulated living world we have had working for years now.

We also have been working on improved lighting, volumetric fog and other effects. And there is more coming, such as a much improved global illumination model. Truly dark caves are on the way!

Some of these things are in the game now — we’ve been slowly putting in the new assets for months — but a lot of it is still pending a big patch to the game to roll out the technical features. But we’re at the point in development where it made sense to share some of the new visuals as a teaser.

Environments are well along, and we are tackling all the hard surface objects next. Then, we will redo characters and creatures too. It should all add up to a pretty significant change in the game’s style, though we are sticking to a somewhat stylized realism look since the games market is currently chock full of photorealistic games that are indistinguishable from one another.

All of this is also coming with pretty significant optimizations as well, resulting in smoother framerates and general performance. Plenty more to do!

I thought you might be amused to see just how far we have come, so here’s a selection of images from way back when to now. When we first announced and got pushback on the graphics, we said we would keep working on it. Well, iteration takes time. But I think it’s really cool to see the incremental steps forward over time.

2021

2021

2022

2022

2023

2023

2024 — same jungle you see in the new visuals!

2024 — same jungle you see in the new visuals!

I could swear I own this paperback

I could swear I own this paperback

Upcoming visuals

Upcoming visualsI know plenty of folks are probably wondering, “okay, but what about gameplay?” This update is about visuals, but there’s been quite a lot of game stuff rolled out since I last posted! Banks, player run shops, combat updates, and more. Multiple player cities have been built and destroyed this year so far, and we have even blown up a few entire planets. And coming real soon: player governments. If you want to check out the state of gameplay, there are tons of videos up on the Stars Reach Youtube channel.

October 25, 2025

New stuff on the site

I really have been neglecting the blog lately. But that doesn’t mean I haven’t been adding content to the site all along. I figured it might not hurt to do a little summary of items that have been added over the last year and a half or more. The last talk I posted up was my GDC talk from 2024!

So, here’s a bit of a catalog…

For folks who are interested in the history of Ultima Online, I finally gathered up the various snippets I have posted about why exactly the original ecology system didn’t survive to release. There’s a theory out there that it happened because players were like locusts and killed everything and caused it to collapse, and that’s not quite correct. Players were like locusts. But the ecology system came out of the game for economic reasons and for performance reasons. So if you’re curious, you can read the answer to “did players destroy the UO ecology?” here.

I have done a lot of podcast interviews over the last while. Mostly, these end up on the Interviews and Panels page, but I haven’t been calling attention to them here. So here’s a list in chronological order… you’ll notice the rise of “metaverse fever!”

An MMORPG.com interview from 2022 that is all about MMOs and what the hell a metaverse even is. This one has video!Naavik cornered me on The Metacast to talk about game design, Playable Worlds, player-driven economies, and more.At the GDC Showcase in 2023, Game Developer senior editor Bryant Francis interviewed me for a “game design career” fireside chat.Famed game devs Alex Seropian (founder of Bungie, Wideload, Industrial Toys) and Aaron Marroquin (Art Director, Game Designer, part time magician) have a great podcast called The Fourth Curtain where they interview devs. It was my turn back in the day. I got to share the stage with Wagner James Au and Cory Ondrejka at Gamesbeat and get real about the practical steps towards a metaverse of any sort. But not everything was about metaverses! The Here’s Waldo podcast instead wanted to talk about indie studio startups. So here’s a great conversation with Lizzie Mintus about that.If you are more interested in some stuff about Stars Reach and game design, this recent interview with grokludo gets nice and crunchy on design topics.The last major talk I gave was on “The Evolution of Online Worlds,” and I managed to share it social media and never talk about it here. It was filmed, and video as well as PDFs of the slides are available here.

There’s some other stuff too — for example, I did a lot of work around emulation a few years ago, and I finally collected a lot of those materials here, so if you need Vectrex overlays, or want to play the Microvision again, or are baffled by Atari 8 bit computer emulation, you find find some stuff to read on the Emulation page.

I’ll make the usual promise here to be better about keeping the blog updated, but… we’ll see. I haven’t even been good about posting updates on Stars Reach here!

October 12, 2025

Site updates

It’s been quite a while since the site was refreshed. I was forced into it by a PHP upgrade that rendered the old customizable theme I was using obsolete.

We’re now running a new theme that has been styled to match the old one pretty closely, but I did go ahead and do some streamlining: way less plugins (especially ancient ones), simpler layout in several places, much better handling of responsive layouts for mobile, down to a single sidebar, and so on.

All of this seems to have made the site quite a bit more performant, too.

One of the big things that got fixed along the way is that images in galleries had a habit of displaying oddly stretched on Chrome and Edge, but not in Firefox. No idea what it was, but it seems to be fixed now.

There are plenty of bits and bobs that still are not quite right. Keep an eye out and let me know if you see anything that looks egregiously wrong. Known issues: some of the lists of things, like presentations, essays, etc, are still funky. Breadcrumb styling seems to be inconsistent. The footer is a bit of a mess.

If you do need to log in to comment, the Meta links are all at the footer for now. Virtually no one uses those links anymore, so having them up top didn’t seem to make sense… How things have changed!

People tell me to move to Substack instead, but though I get the monetization factor, it rubs me wrong. I’d rather own my own site. Plus, it’s not like I am posting often enough to justify a ton of effort!

June 20, 2025

Stars Reach doesn’t look like you remember

I’ve been remiss in posting updates on Stars Reach here. I mean, the Kickstarter finished back in March (late pledges still accepted)! Today, though, I want to brag about our awesome AI and proc gen driven worlds.

Over the last few releases, we have been rolling out yet another series of improvements to the look of the worlds. And we’re getting to the point where I think the alien worlds are starting to look like the covers of sci-fi novels (especially with some player help building weird structures):

Uh oh, the monolith

Uh oh, the monolith

I could swear I own this paperback

I could swear I own this paperbackRemember, our worlds are effectively created on the fly. They’re run by AIs in every cubic meter. Everything you see is malleable and changes around you, and players can resculpt every inch of it. Heck, every tree and every bush is a mob.

Recently, we have done huge updates to lighting, flora seeding and propagation, and generation of distinct alien subspecies on each planet. We did a pass on material adhesion, so everything slumps or holds together more realistically. You can now fly through a wild wormhole, and in every play session, the planet on the other side will be unique… and gone by the next play session. And the look is really starting to click together, I think. I mean, just compare to the shots from my last post in early March!

Alien cacti on Zaraxa

Alien cacti on Zaraxa Night on a lost wild wormhole world

Night on a lost wild wormhole world A wintry landscape with deer

A wintry landscape with deer Watch out for panthers

Watch out for panthers Hmm, that seaweed is misplaced

Hmm, that seaweed is misplaced Looking out from the cave over the canyon

Looking out from the cave over the canyon Flying over the jungle

Flying over the jungle Thickets!

Thickets! Hunting by night

Hunting by night More flora density!

More flora density! Meteors falling in the background

Meteors falling in the backgroundThat’s not all, though. Players have invented ice rinks and heat pumps and most recently, even an elevator, using the in-game physics. They’re building crazy stuff. It’s awesome to see. All of this stuff is player built, using one of the three building methods (or all three!): terraforming, block building a la Minecraft, and tile building.

In the next few updates, we’ll be doing big performance updates alongside major visual updates to flora and other in-game objects, plus adding a whole bunch of features to get us closer to our current goal: keeping the servers up 24/7 by the end of the summer. It’ll be tight, but we’re making good progress.

So there’s yet another few quantum leaps coming on the game look!

Oh, there’s game stuff to talk about too. Combat has taken leaps and bounds, and there’s a huge update to that coming soon too. But right now, I just wanted to show off the visuals a bit.

March 3, 2025

One week of Stars Reach Kickstarter

Wow, it has been an intense six days.

We launched on Tuesday, which feels like an eternity ago. It’s a mad scramble to get everything done, make sure you have all the content ready, to answer the huge inflow of questions, find all the spots where you weren’t quite clear enough… but you just survive on little sleep and keep pushing. And sometimes you get a good result!

Last night we hit the $500k mark on the Stars Reach Kickstarter. This also unlocked our third stretch goal, the Hyugon playable species that you see animating over here. (There’s a blog post up on the website if you want to learn more about them!).

But that’s far from all. We also hit a stretch goal for the Hansians, an aquatic species that is one of my favorites. There’s a blog post up about them as well. We’re dropping bits of their lore into these behind the scenes posts, as well as sharing their visual evolution through art iterations and market testing.

There’s also a series on our audio design posted up there, as well as other material. Lots of info coming out about the game now, so keep an eye on the News section for it. We will try to be good about reposting this content on Reddit and Steam as well.

We’ve also ramped up our YouTube presence quite a bit! There have been six videos on the Stars Reach channel in just the last week, including several livestreams. Some of these are part of a new series called “Q&Raph” in which our community manager Thomas interview me for a half hour at a time. These dive deep into technical stuff, the background of the project, and more.

We also have done sneak peeks of upcoming features, sessions with other devs on the team, and more. Worth checking out, if you want to have something to play in the background while you work!

All in all, this has been an exhausting week, but it has been amazing to see the support from the community. We will be keeping up this content drumbeat throughout the campaign, of course, so there’s weeks left of this grueling pace.

Lastly, I wanted to share some images from recent playtests, because, wow, players have dazzled us with their creations.

Spread the word — we know there are lots of people who have still never heard of us!

February 26, 2025

STARS REACH Kickstarter funded in 1 hour

I can’t tell you how much of a rollercoaster yesterday was. We hoped to see a strong Kickstarter but reaching our goal is less than one hour is just amazing, and a real expression of support from the community. Thank you all so much. (You can check out the Kickstarter here!)

We’re not stopping here. As I write this, we are on track to double our initial goal today! We hit our first stretch goal, for the Hansian species, overnight. Hansians were first mentioned in our lore in the short story “Interdicted,” which we posted up on the website a couple of weeks ago.

Last night I did a 90 minute stream where I showed video of upcoming features ranging from the small (inventory search) to glimpses of improved rendering. You can check out the VOD of the stream here.

We will continue to do streams, releasing info, and of course, letting people in to try out the game.

There is loads of coverage:

“Stars Reach: A Living Galaxy Sandbox MMORPG” Raises Over $200k on Kickstarter In 1 Hour – MMOs.comUltima Online and Star Wars Galaxies’ “spiritual sequel” smashed its $200k Kickstarter target in under an hour, and the sci-fi fantasy MMORPG is now on track to double its goalStars Reach Aims to Revive the Sandbox MMO Glory of Star Wars GalaxiesStars Reach Looks To Fill The Star Wars Galaxies-Sized Hole In The MMO SpaceThe Stars Reach Kickstarter Just Went Live And It Already Met Its Funding Goal Of $200KWe still need your help to keep our velocity up. Even if you don’t feel comfortable pledging, tossing in $1 helps increase our backer count and show momentum. Please check out the Kickstarter here!

February 25, 2025

STARS REACH Kickstarter is live now

Today we are launching the Kickstarter for Stars Reach.

Why a Kickstarter? Well, the funding climate is rough. But we have seen that players love what we are making.

So we want to prove to the industry that people want a modern sandbox. An alternate world that feels alive, not like a static cardboard set. A game where different sorts of playstyles come together to make an immersive and dynamic galaxy. Where you can play the way you want, and the game values it, and the other players value it because you matter to the game’s economy.

I’ve been dreaming of making this game for thirty years. It’s what I wanted to do right after Ultima Online. It’s what I hoped Privateer Online could become. I cannibalized ideas from it for Star Wars Galaxies. The tech stack is inspired by what we did with Metaplace. It’s the culmination of all those years of design work and dreams.

If you also share the dream of getting online worlds back on track from a multi-decade detour into pellet-gathering themeparks, please consider backing, even if it’s only at the $1 tier. Every backer helps show momentum and interest. Do it as a favor to me.

December 13, 2024

Flooding Gaiamar

A true story of what happened in the pre-alpha testing last night in Stars Reach.

It began as an upwelling under a basement.

Oh, ever since the crater lake next door had overheated and spewed a geyser far into the sky, water was everywhere… condensing on every surface. But this was something more. It bubbled up from under Leric’s house, right there by the fountain in the middle of the settlement on Gaiamar.

The geyser erupting. Sabotage using the chronophaser to superheat the water is suspected.

The geyser erupting. Sabotage using the chronophaser to superheat the water is suspected.Mayor BeanstalkHead was not pleased. Sinkholes were appearing in the expensively constructed cobblestone walkways. One had collapsed into a home under construction, leaving the foundation exposed.

We couldn’t find a source. All we could think was that as the lake had been emptied, water was forced into the soil and was now just welling up under there. Plus, we had an unsightly pit where the lake had been. We had to resort to requesting Servitor assistance to remove the water (and a stray ammonia dump that was contaminating it). But we were worried it would happen again.

Ammonia pouring down. It’s toxic, it gets everywhere, and it mixes with the water and makes it harder to clean up.

Ammonia pouring down. It’s toxic, it gets everywhere, and it mixes with the water and makes it harder to clean up.So I carefully set about lining the entirety of the pit with nice black brick. Each side, and a floor, underneath where the dirt was. I source nice big boulders of granite and breccia to conceal what I hoped was a waterproof lining. Added in gravel and sand and made a lovely lake bed under there. By the time I was done, you couldn’t tell that it was an artificial lake now.

Even better, two citizens donated some of their land grant to make the refreshed lake private property! Until we formally claim the planet, we won’t have public spaces protected by Servitor suppression fields so this was a useful workaround to prevent someone else from superheating the lake and once again sending a mile-high column of steam into the air.

A aerial view of the incipient city and the brand new artificial lake.

A aerial view of the incipient city and the brand new artificial lake.Then I grabbed the hose and started filling the lake — nanotech enabling instant fill up to a waterline. What I hadn’t noticed was the tree growing in the corner. The roots… right through the lining wall.

This is the story of how I accidentally put all of Beanstalk City under a meter of water and collapsed every basement into a mudpit.

Water flooding into the homes under construction.

Water flooding into the homes under construction.The water flooded all of downtown, completely submerging the water fountain near city hall. It utterly filled a couple of basements that were in-progress homes, open pits vulnerable to the weather.

Mrgoshdarn’s famed bamboo grove house, with its interior underground walls made solely of compacted dirt and living bamboo trees, had its walls collapse and its pristine marble interior completely slimed with mud.

Mrgoshdarn’s famed bamboo wall basement. The compacted dirt walls collapsed shortly after this picture was taken.

Mrgoshdarn’s famed bamboo wall basement. The compacted dirt walls collapsed shortly after this picture was taken.We set up water vacuums to clear the worst of it, and watched the dirty water whirlpool away. But the real issue was the erosion. The empty fields destined for parks by city hall became sticky muddy flats, slowing people when they trudged through. Sidewalks gave way and fell into caverns below.

Draining away water from a home’s foundation.

Draining away water from a home’s foundation.A lot of recent construction had to be removed due to water damage. Beanstalk City survives, however, and we will endure.

You can see the muddy flats to the right by the city hall.

You can see the muddy flats to the right by the city hall.

All of this happened in the testing last night, and I haven’t actually embellished it much! We released homestead claims last week, and players promptly started collaborating on building a city. The geyser, the ammonia spill, and the flood all happened as described. The land ownership features, water erosion, and the rest, all actual stuff in the game.

It’s really cool to see this sort of emergence happening, and players diving in (no pun intended) and really exploring what a living virtual world can be.