Stephen Davenport's Blog

January 10, 2024

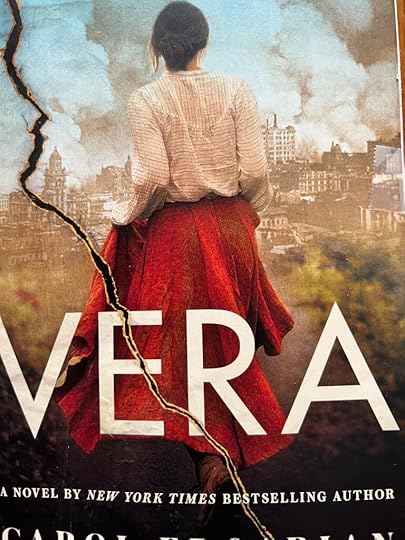

VERA, A NOVEL BY Carol Edgarian

[

Forget the history books. If you really want to know what it was like to live – or die- in San Francisco when the 1906 earthquake hit, put yourself in the hands of master storyteller Carol Edgarian, get a copy of her novel Vera, published in 2021, and start reading.

Right away you will meet the fifteen-year-old Vera who tells the story. She is the illegitimate daughter of Rose, San Francisco’s predominate madame, owner and operator of the city’s predominate brothel, named – you guessed it- The Rose. Rose, and therefore Vera also, is probably a mix of Persian, Northern African, and Spanish blood, with a suspected dash of Armenian, who, for a fee was brought north from the slums of Mexico City by the 19th century version of a coyote to become eventually the “Grande Dame of the Barbary Coast, the Rose of The Rose.”But Vera does not live with Rose, either in the brothel or Rose’s magnificent mansion on Pacific Heights – to this day unusual territory for people of such bloodlines. Instead, Rose pays a very proper, quite boring widow named Morrie to bring Vera up “to be anything but a hooker.”

The foundation on which Edgarian rests Vera’s story is the schizophrenic nature of Vera’s life as she shuttles back and forth between her proper, conventional, relatively colorless environment as Morrie’s adopted daughter and the mysterious technicolor of Rose’s environment where she is befriended and even mothered by the ladies of the night.

Vera’s double life is made more emphatic by Vera’s adopted sister Pie who is as different from her as Rose is from Morrie.

We meet Pie, (sweety pie) at age eighteen, three years older than Vera. It is just nine days before the earthquake that will level the city when the two girls walk the family dog on a familiar loop from Morrie’s house on Franklin Street to Fort Mason and back. “Pie walked slowly, having just one speed, her hat and parasol canted at a fetching angle. She was eighteen and this was her moment. All of Morrie’s friends said so. “Your daughter Pie has grace in her bones,” they said. And it was true: Pie carried that silk net high above her head, a queen holding aloft her fluttery crown.

Now grace was a word Morrie’s friends never hung on me. I walked fast, talked fast, I scowled. I carried the stick of my parasol on my shoulder, with all the delicacy of a miner carrying a shovel. ------- and anyone fool enough to come up behind me risked getting his eye poked. We were sisters by arrangement, not blood, and though Pie was superior in most ways, I was the boss and that’s how we’d go.”

And that’s how it does go: it is the feisty Vera who takes the reins, makes the decisions, takes the action necessary for survival when the buildings tumble and the city burns and Pie moons over a lover who jilts her. It would be a spoiler to tell what those actions are and how it all turned out; suffice it to say here that if you want story, this novel is for you, populated with every kind of character, prostitutes, business people, kind motherly neighbors, a corrupt mayor in dire need of an emergency to prolong his career, a multiplicity of races from very level of society, one dog and two horses.

And for icing on this spicy cake, Edgarian, like Dostoevsky in Crime and Punishment, identifies the specific place, naming the address of where the events take place so that if like me, you live in the Bay Area or have visited San Francisco, you feel like you are right there with Vera all the way.

For me, Vera is like a Dickens novel without the boring redundancy and fluffy sentiments. A wonderful read. Bravo!DetailsDetails.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 0px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 0px;}

March 14, 2023

Two Excellent Books About The Sinking of The USS Indianapolis

At 12:05 am on Monday, July 30, 1945, a torpedo fired from a Japanese submarine struck the starboard side of the USS Indianapolis, near the bow; seconds later a second torpedo hit her amidship, also on the starboard side. Minutes later, the cruiser, on a run from Guam to Leyte on the last days of the war, disappeared beneath the waves. Approximately 300 men died aboard ship, the lucky ones killed immediately, even vaporized by explosions, others by drowning and many in the most horrible way: by burning. Approximately 900 men, including the commanding officer, Captain George Butler McVay, 111, made it off the ship. They were in the water for three days before anyone knew the ship had been sunk. By the fourth day, when they were rescued at last only 315 men had survived. Many had been killed by sharks whose presence was relentless, attacking at dawn and sunset. The sinking of the Indianapolis is deemed to be the worst disaster in U.S. naval history.

It would be a spoiler to tell you of the mistakes the navy brass made that increased the chances that the Indianapolis would be attacked and undeniably was the only reason the survivors were in the water as long as they were. And yet Captain McVay was the officer court martialed. Both books tell of the survivors’ long struggle to exonerate their captain. Having served in much less dangerous times at sea and later on land, I am not surprised by this injustice, but I am outraged.

Both books, In Harm’s Way, by Doug Stanton, and Indianapolis, co-authored by Lynn Vincent and Sara Vladic, are compelling reads, with driving narrative force, specificity of detail and deep penetration into the suffering and valor of the crew via the authors’ interviews with the survivors. I read Indianapolis two years ago and was so haunted by the tragedy that when I discovered In Harm’s Way recently, I read voraciously. The books are not redundant of each other. They complement each other. They address the tragedy from different perspectives and tell the events in different sequences. At their essence they both are a cry for peace on earth.

[image error][image error].fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 0px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 0px;}January 17, 2023

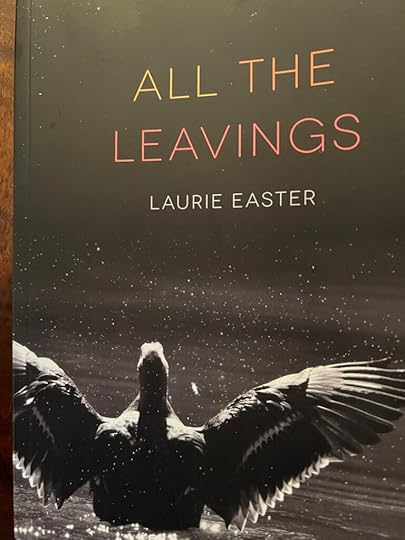

ALL THE LEAVINGS, BY LAURIE EASTER

What is the best memoir to read?

Last night – or maybe it was early this morning- I read the last sentence of Laurie Edwards’ essay collection All The Leavings, Published by Oregon State University Press in 2021. For the second time! So, if you ask me that question any time soon, All The Leavings will be my answer.

What is it like to live off the grid in the Oregon wilderness in a cabin where the bathtub is outdoors?

To be in the emergency room wondering if your daughter will survive?

To wake up in the middle of the night and realize that your beloved cat is outdoors, prey to a cougar who has been hanging around? you rush out, naked, into the woods calling for your cat until you hear the cougar’s footfalls very close. Suddenly you know what it is like to be prey.

What is it like when your daughter’s friend leaves by suicide? What’s it like to remember your own suicidal thoughts?

To leave, head out, say goodbye?

What do your friends leave in your heart when they die? Some of the answers might break your heart and I guarantee the last of the leavings in the Afterword will.

The thing is I want my heart to be broken. I want to go to places I evade in my own life. A fine editor, Tom Jenks, told me, while editing an early draft of Saving Miss Oliver’s, that I was evading places the story needed to go. “Where are those places?” I wanted to know.

“The places where it hurts the most,” he said. “And where life is so intense it’s scary.”

Laurie Easter goes like an arrow straight to those places.

All The Leavings is the work of a gifted and courageous writer

[image error][image error]December 2, 2022

The Vagabond, by Colette

I obtained the book you see pictured here so long ago that, when I read it last week, I had to read in short bursts and take Benydril, because the invisible mold on its pages afflicted my sinuses.

Sidonie Gabrielle Claudine Colette, born in Burgundy, France in 1873, published The Vagabond in France in 1910. It was, translated to English, and republished as the paperback in the picture, by Doubleday, under its imprint anchor books, in 1955. It is published now in English, by Dover Publications.

(My wife, Joanna was working at Doubleday, as assistant to the editor of foreign rights, when it published The Vagabond , which I believe is how we obtained a copy. In the mornings, he was a competent foreign rights editor; in the afternoons, after multi-martini lunches, not so much. During the afternoons, Joanna covered all his bases for him, for a whole lot less pay than he was getting, but that’s a story for another day.)

The best way to classify The Vagabond is as early women’s lib, long before the term was common.

Like Renee, the protagonist, in the novel, Colette made her own living as a travelling music hall performer after divorcing an abusive and unfaithful husband, Henry Gauthier Villars, a prominent literary critic who locked her in a room so she would focus on writing the wildly popular Claudine Series, for which he took the credit and kept the royalties for himself! After her divorce, while performing as a music hall mime, Colette managed to write an average of a novel a year. In 1910, she married again. That marriage ended in 1935 when she married for a third time. This last marriage, to Maurice Goudeket, also a writer, was a happy one. She died in 1954.

The Vagabond closely mirrors Colette’s own life.

Renee has settled into her life as a music hall performer when Maxime, a young, handsome, independently wealthy man arrives uninvited in her dressing room, declaring his admiration and bearing the usual flowers. Still simultaneously grieving for the lost love between herself and ex husband, and still furious at him, she’s determined to abandon romantic love forever. She dismisses Maxime, addressing him contemptuously as “Big Noodle,” and continues to hold him at bay. But he persists, showing up in her dressing room night after night, until, over time, she falls in love with him.

It is not clear to her whether she wants an enduring, loving marriage, including the pleasures of sex, or is seduced by the comfort and security that comes with marriage to a man so wealthy he has no profession, and who swears he will focus all his energies on making her happy.

The reader has the pleasure of being in her head as she makes her decision, one that covers all the markers of the relations between men and women, and the place of women in society, especially in Renee’s case, the lowly place of unmarried female music hall performers assumed to be licentious, ready to be kept.

It would be a spoiler to tell what Renee decides as she plies her trade in a long absence from Maxine during an extended tour of European cities. Suffice it to say she knows that marriage to Maxine will come with his domination over her, even though that is not what he wants. The very act caring for her, providing her his home, his wealth, and his respectability is a kind of domination, however inadvertent.

I was compelled by this novel, told in prose, that even in translation is powerfully evocative of the senses. And it was delicious, for a change, to read so-called sex scenes that are not scenic at all. What a pleasure not to know whether the lovers are in a hurry, or take the time to take their clothes off first, whether the woman achieves orgasm or not, and whether the lights are on or off.

What good luck it was to discover this book behind another on my shelves, and to read it for the first time after owning it since 1956!

November 14, 2022

Best War Novels

The tragedy of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine sent me to my bookshelves this morning to look for and remember the novels about war that I thought were worth keeping and treasuring. Here’s the list.

Tolstoy’s War and Peace

Eric Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on The Western Front

Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms, and For Whom the Bell Tolls, and obliquely, because set soon after the armistice, The Sun Also Rises

Pat Barker’s World War One trilogy, Regeneration, and The Eye in the Door and The Ghost Road

Sebastian Faulks’ Birdsong and Charlotte Grey

Joseph Heller’s Catch Twenty-Two

Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five

.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 0px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 0px;}October 27, 2022

HOW LONG DOES IT TAKE YOU TO WRITE YOUR BOOKS?

How many words a day should you try for?

The question is imperative for me because I am 91 years old. I’m worried that time will run out before I write all the books that are in my head. I have no interest whatsoever in a calm, leisurely fade. I want to die with my hands either on a computer’s keyboard, or a tennis racquet.

So I was intrigued when I came across a post online by one of the multitude of people who make their living by pumping out advice to writers, urging her readers to write a minimum of 2K words a day. “You can finish a complete draft in less than a month!”

Wow! If I write two more drafts of the novel I am writing now, each taking one month, I can finish in three months. Thus, I could write four novels in a year – the first three in the same time it takes to make a baby! Maybe I better look into this.

Her advice to writers: to write 2k words a day or more, first outline the entire novel and write the biographies of each character before you write the first word of the actual novel.

That’s good advice for some writers, but it doesn’t work for me. I’m not sure I could outline a business letter or the message on a birthday card, let alone a novel. In the second place, it would take me a year to outline the entire arc of a novel in sufficient detail to enable the production of the first draft in a month. Better to just start writing.

I’m not sure whether I start with a character I want to get to know or the situation she finds herself in.

Finding the way without an outline

All I knew when I started writing The Encampment, the third novel in the Miss Oliver’s School for Girls Series, is that Sylvia Bickham, the daughter of the head of school, was a senior there who was less motivated than her friends to compete for admission to one of the “best” colleges. She didn’t want to wait four more years to enter “real” life. I also knew that she was a person of color, like her mother, and that she would leave campus on a Saturday afternoon early in the academic year to get an ice cream cone in the nearby village. I didn’t know she had a roommate to walk with until I gave her one, Elizabeth Cochrane, from a little impoverished town in Oklahoma.

By then I realized that the two girls were going to come across a homeless Iraq war vet with PTSD. I understand now, looking back, that the homeless veteran was in my subconscious because I was, and still am, outraged that our American culture is so cruel that some of its less fortunate have to sleep on sidewalks and under bridges. I doubt that the homeless vet would have come to my mind in an outline.

I had to send the girls out of the safety of their campus to be confronted with the fact of that cruelty. As soon as they did. I knew they were going to put some money in his hat and get more and more involved with him in an effort to help him survive. And then I knew that their experience would teach both girls what they wanted to do with their lives.

Once I had that beginning established, I had a fair idea of how the novel would end, but only the next step on the path to that destination was clear, and then the next, and the next – an incremental journey during which I was frequently surprised by what the characters did. This is a much slower process, at least for me, than writing to an outline. And, for me, a whole lot more intriguing. Instead of planning, I discover.

Since reading that post, I have started to keep a record of how many words I write each day. The average is 1015.

I am very interested in how writers write. I’d like to learn from writers how many words you write each session, how fast you write your books, whether you outline before you write, and if so, in how much detail and how often what you actually write is different from what you posited in the outline. If you are so inclined, put your answers in the comment section below. I promise to get back to you.

.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:60% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 3.2%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 3.2%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:60% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 3.2%;margin-left : 3.2%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 0px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 0px;}October 10, 2022

MAKING AN AUDIO BOOK

A few months ago, I made an audio version of Ninety-Day Wonder, How The Navy Would Have Been Better Off Without Me, a memoir I had just finished writing about my two-year hitch as astonishingly unqualified officer in the Navy from 1953 to 1955. I am now in the process of deciding whether to publish the print and audio version with a traditional publisher or to self-publish. But that’s not what I want to write about today. Instead, I want to share what the experience of narrating the book in a professional audio studio was like.

I had expected it to be very difficult. I thought audio studios were about the audio only. I assumed I would be on my own about pace, diction, rhythm, when and for how long to pause, or anything else that a neophyte like me would need help on when delivering a story to listeners as opposed to readers. I could not have been more uninformed. I got all the guidance I was capable of absorbing. The process was exciting, satisfying, much less difficult than I had expected, and I am very satisfied with the outcome.

I made the audio at Live Oak Studio, in Berkeley, California. I should say we made it, James Ward and I as a team. He greeted me as I entered and introduced himself as my director. That word was my first clue that he would do much more than record the sound of my voice; instead, like the director of a film, he would guide me as I read. That is exactly what James did and he did it very well.

What is interesting to me about his reassurance was that he did not deliver it to me face to face; instead, after he was out of sight, ensconced in another room with all the instruments for recording, and I was seated in a different room where the microphone was placed in the right relationship to me and where I donned earphones through which I would hear his direction and my voice as I read, and where an IPad opened to the manuscript of Ninety Day Wonder was mounted directly in front of me. All I would have to do was scroll down as I read. No sound of rustling pages to disturb the listener. The impact of his talking to me when out of sight was to attune me to working entirely auditorily. It was brilliant.

He told me that when I read too fast, or my voice began to sound tired, or when I slowed down too much, or mispronounced a word, he’d stop me, delete the passage, and suggest how I should re-read it, several times, if necessary, to get it right. He told me that I would get tired so we would take breaks and remind me frequently to drink the water he had provided.

Thus reassured, I started to read. As James came through on all of his promises, I got more and more relaxed and discovered I was having fun. I remembered how I had loved reading to my children and grandchildren. I heard myself bringing out nuances that might very well not be recognizable on the page. Sarcasm, self-deprecation, amazement that the events I was narrating actually happened, caused me to change my tone of voice – as when we talk to one another, we instinctively change our tone of voice to match our meanings. I felt an intimacy with the potential listeners as if they were right there in the room with me listening to me talk to them. I am convinced that the audio version of Ninety-Day Wonder is better than the print.

I am not sure this would be true if it were not a memoir. Audios of novels are most often narrated by professional voice actors who play the parts of the various characters. Memoirs are more intimate. They are confessions. Nobody is better suited to tell listeners directly than the confessor. Nevertheless, I am considering making an audio of The Encampment, the latest novel in the Miss Oliver’s School for Girls Saga. After all, I wrote it. Shouldn’t I be the one who reads it out loud?

I am eager to learn about the experience of other writers who have made an audio book or are considering it. And from readers/listeners about their preferences: reading or listening. If you are so inclined, do so in the comments. I promise to get back to you.

.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:60% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 20px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 3.2%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 3.2%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:60% !important;order : 0;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 3.2%;margin-left : 3.2%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;order : 0;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 0px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 0px;}July 25, 2022

Mr. Zeetzee’s Terrible Temper

We lived in Riverside, CT, on a point of land that reached out into Greenwich Cove, on Long Island Sound. Our back yard went right to the water, and at the end of the point, less than a quarter of a mile from our house, there was a small private beach with a pier to dive from when we went swimming. Ever since I’d been a little kid, Mr. Zeetzee and his wife had lived across the narrow street that went down the center of the point of land to the beach. He wasn’t like all the other men on that street who commuted to their work in New York City. He owned a jewelry store in Stamford. That made him different somehow. I liked him. He was always friendly to me.

One day, during a snowstorm when I was walking home from school, he stopped to give me a ride. I wasn’t surprised; he wasn’t the kind of guy who would drive right by a neighbor’s kid walking in a snowstorm. I don’t remember what we talked about, but I do remember how glad I was to be riding instead of walking. He drove calmly through the peaceful silence that comes with falling snow, until two kids walking home from the elementary school stepped out into the road and he had to put on the brakes. The car skidded in the snow, but stopped well short of the kids. Nevertheless, he jumped out of the car and screamed at them. They ran away. He kept on screaming, his body shaking, even after the kids had stopped running, several hundred yards away. I was frightened enough to want to get out of the car, but I thought that would insult him, and I didn’t dare. Finally, he got back into his car. I could tell he was ashamed. We didn’t say a word to each other the rest of the way.

That temper got Mr. Zeetzee into big trouble on an August night a year later, the summer before my tenth grade year. My parents were away fly fishing in Maine and my friend John B was spending the night at my house. Even then, I was amazed at my parents’ naiveté to leave me and my older brother unsupervised. I suspect that John’s parents didn’t know that my parents weren’t home. My two younger brothers were away at a summer camp and my older brother was visiting a friend – which is probably why I had invited John. I didn’t want to be alone.

All the stars were out. It was warm and humid, the tide was high, and John and I, of course were restless, so around ten o’clock we walked down to the beach at the end of the point. There was a big sailboat, a yacht, at least forty feet long, tethered to a buoy several hundred yards away. It had not been there before. So, curious, we “borrowed” a canoe that was lying on the beach – maybe it was Mr. Zeetzee’s – and paddled out to it. With each stroke of our paddles, the phosphorescence in the water lighted up the night. There was no one aboard the yacht. We tied the canoe to the buoy and climbed up onto the deck. It was a magnificent vessel, with a commodious cabin. It was so big it had a steering wheel instead of a tiller. “You could go around the world in this,” I said.

“So, let’s us sail it around for a little while,” John said. I was dumbstruck. We stood there looking at each other. I can still remember the smell of varnish and the hemp of ropes. I knew if I said ‘yes,’ we really would steal that yacht and sail it around in the dark. Like so many times before, he had suggested something that I wanted to do, just as fervently as he, but I lacked the nerve. We already understood that one of the reasons for doing things others would never dare is to add to the collection of stories you can tell for the rest of your life. That’s powerful motivation for doing dumb things! But I knew we didn’t have the competence to sail so big a craft. We’d run it aground someplace and end up in jail.

I was tired of being the one who didn’t dare. I said, “I got a better idea. We’ll climb the mast and dive off.” Even he wouldn’t do that. It was much too dark.

“Okay,” he said. “Let’s.”

It turned out to be easy. There were ratlines to climb. So up we went.

But the crosstree we stood on way up there was thin and hurt my bare feet. I was dizzy with the height, and it was so dark we could barely see the water down below. It would be like diving from a cliff with your eyes closed. “How do we know it is deep enough?” I said. “We could hit bottom and break our necks.”

“Yeah, maybe it’s shallow, “John said in his most matter-of-fact tone. I’ve never known anyone who was so good at keeping his expression blank. It was why his jokes were so funny: he never laughed.

“Well then, maybe we better steal this yacht instead,” I said.

“No,” he said. “Just dive straight out, not straight down,” and then he did exactly that, launching himself. He hit the water in an explosion of phosphorescent light and disappeared. I knew he was staying under the water to scare me into thinking he was dead, but when he finally surfaced, I started to breathe again.

I was more afraid of being ashamed of being scared than I was of gravity, so I dived too. And discovered how much fun it was. I don’t remember how many times we climbed and dived into that phosphorescent gleam before we quit and paddled home. I do remember it was magic.

Walking home, still keyed up with the excitement of the diving, I picked up a rock and threw it hard at a tree on the other side of the narrow street. I hadn’t noticed Mr. Zeetzee standing on the front steps of his house – until the rock missed the tree, hitting the steps he was standing on, then bouncing up and striking his leg. Unlike the purposeful trespass on the yacht, this was completely a mistake. Besides, the rock had lost most of its momentum when it hit his leg. But I knew of his temper, and I started to run.

It was too dark for him to recognize me, so, as we came near my house, I turned to John running beside me to tell him to run past my house so Mr. Zeetzee wouldn’t know it was me. But what I saw wasn’t John; it was a lighted cigarette, still in Mr. Zeetzee’s lips, cruising along beside me, and the next thing I knew I had dived into some bushes. He’d never seen me. He’d seen John who was wearing a white T shirt, while I was only in shorts. I watched John run down the street in bare feet, Mr. Zeetzee in hot pursuit, until they disappeared around a bend. Then I went into my house and turned all the lights out so it would appear that either no one was home, or everybody was asleep. I told myself not to worry about John. He could run fast. Mr. Zeetzee wouldn’t catch him.

But it seemed forever that I was alone in the house, and I began to imagine Mr. Zeetzee catching up to John and beating him up. Maybe killing him? Then through the living room window, I saw the headlights of Mr. Zeetzee’s car coming out of his driveway and heading down the road. Now I was sure Mr. Zeetzee had caught John, hurt him badly, then grown ashamed of himself, as when he’d screamed at the kids who’d stepped out into the road. So he was taking John to the hospital! Should I call my parents in Maine and ask, ‘What do I do now? Should I call the police?’ Either one of those actions would have been a sensible thing to do. Which, I suppose, is why I didn’t do either of them.

I waited, and waited in the dark of our living room, wishing my brother were home to tell me what to do, or, better yet, persuade me that John was safe. He was a whole year and a half older than me, and either was actually more responsible, or better at appearing to be – I still don’t know which.

It must have been near midnight when I heard a knocking at the back door. Someone had come to tell me that John was dead. Or maybe John had told, under torture, who had actually thrown the rock, and Mr. Zeetzee had come to kill me too.

But it wasn’t an enraged Mr. Zeetzee at the door, nor a bad news messenger. It was John, soaking wet. “You swam?” I said, my relief that he wasn’t dead replaced by envy. I never would have thought of escaping that way.

He shrugged as if swimming was the usual way to get to my house. “What have you got to eat?” he said. “I’m hungry.”

Over a monster sandwich and a quart of milk, he told me, with the same straight face he’d suggested we borrow the yacht, how much fun he’d had with Mr. Zeetzee. “He could never catch me,” he said. “He’s much too fat. I’d let him almost catch up to me and then I’d sprint.” John went on to explain that this got boring after a while, so he headed for the woods where he hid behind a tree and yelled Zeetzee, Zeetzee, Zeetzee. “I knew that would get him,” John said. “If I had a name like that, I’d be pissed too.” When Mr. Zeetzee, crashing through the underbrush like a drunk grizzly bear, got near the tree, John would slip away to another tree, calling, Over here, Mr. Zeetzee, Over here!

After a while, Mr. Zeetzee stopped chasing him. John was sure he was pretending to have given up and had gone home. John was too smart to fall for that one, so for the next ten minutes or so, he stayed where he was, thinking he was outwaiting Mr. Zeetzee, but then a car’s headlights were lighting up the woods. Mr. Zeetzee’s fury was so durable that it had lasted long enough for him to go home, get his car and drive it back so he could shine his headlights into the woods and find John.

“I stepped out from behind the tree, and said ‘Hi Mr. Zeetzee,’ and waved my hand like I was glad to see him again,” John told me, and went on to tell that Mr. Zeetzee jumped out of the car and came running toward him. John jumped sideways, out of the beams of light, and sneaked in a big circle back toward Mr. Zeetzee’s car. “After a while, I realized I’d lost him,” John said. “It was kind of disappointing. So I made some big whooping noises. I heard him crashing around in the bushes. He still didn’t know where I was, so I went the rest of the way to his car and started blowing the horn.”

“All of a sudden, he was right there in front of me, grabbing for me,” John said. “I guess I’d blown the horn a few too many times. He was making funny noises, like snoring and screaming all at once and I could feel how crazy I’d made him. So I yelled goodbye and took off.”

John ran, full speed now, not playing games anymore, out of the woods, across the road and an empty lot, where some college age kids were singing songs and drinking beer around a fire and dived into the water at the back of the cove, a good half a mile from my house. It took at least a half an hour to swim to my house. I imagined him calmly swimming under all those stars, and my envy, mixed with admiration, grew even more intense. “I knew it was your house because all the lights were out,” he said. “So I climbed up the sea wall and knocked on the door.”

So that was that. Two fine adventures in one night! How satisfying is that?

Two days later I saw the headlines in our local newspaper, Greenwich Time: RIVERSIDE MAN ARRESTED. And a picture of Mr. Zeetzee. The article told how Mr. Zeetzee had burst upon the college kids sitting around the fire, and proceeded to beat one of them up. I would never have seen the article if I hadn’t happened to offer to take a friend’s place on his paper route that day so he could he could go sailing with his parents. All of a sudden, he was punching me in the face, the article quoted the kid. I figured, in the light of the fire, like the light of the headlamps, he must have looked like John. The kid’s father was pressing charges.

After I finished the route, I kept one of the papers and showed it to John. I needed to know how he would react. Did he feel guilty? After all, he was the one who had tortured Mr. Zeetzee. Yes, I had started it all, but by mistake. John didn’t let on how he felt. I got the same blank expression, and a little shrug. After that, we never talked about that night.

But I was the one who’d known Mr. Zeetzee, and had liked him, ever since I’d been a little kid. Not everyone stops and gives rides to people walking in snowstorms. There was no way I would ever be able to look him in the eye again.

My parents came home a few days later.

The next day, a bright warm Saturday, when the tide was high, my father said, “Let’s go swimming.” I prayed Mr. Zeetzee wouldn’t be on the pier. But there he was, sitting on the bench with a towel around his neck. We had to walk right by him. Not having read the paper because he’d been away, my dad didn’t know about his humiliation. And of course, no one in our neighborhood would talk about it. But I saw Mr. Zeetzee’s shame when my dad said hello to him. He didn’t know my dad had been away. I said “Hi Mr. Zeetzee, but I kept my eyes away, and kept on walking, my eyes straight forward toward the buoy where the yacht was tethered no longer, and dived off the pier. In the water, I looked back and saw my father dive in. Behind him, on the pier, Mr. Zeetzee had already started to walk home.

That evening, I confessed to my father. I was desperate to get it off my chest. Maybe he’d tell me to confess to Mr. Zeetzee. I started at the beginning, telling him about John’s and my adventure on the yacht. He made it clear he disapproved, though mildly, for trespassing, and he was disturbed that I would take such chances by diving into water that might not be deep enough. “You don’t have to do something dangerous just to keep up with your friends.”

But when I told him about John and Mr. Zeetzee, and how I had started it by throwing the rock, and how I’d thought Mr. Zeetzee was chasing both of us until I’d seen his lighted cigarette and dived into the bushes, he started to grin. I felt a huge relief. Besides, it was fun to tell such a good story, so I told all the details. By the time I’d gotten to the part where John was blowing Mr. Zeetzee’s car horn, he was laughing so hard he had to sit down. When I went on to tell him about Mr. Zeetzee beating up the college kid and getting arrested, he stopped laughing. I’m pretty sure, he had as much sympathy for Mr. Zeetzee as for the kid whom he had beaten up. But I could see that, for him, that was a separate story, a whole other event.

So I didn’t have to feel guilty! My father wasn’t going to tell me to cross the street, knock on Mr. Zeetzee’s door, and when he opened it, stand there, look him right in the eye and confess to him!

Then why didn’t I feel satisfied? I’ve pondered that question ever since. My father remains for me the most upright man I’ve ever known. He never would have even considered stealing someone’s yacht.

On the other hand, he would never have gotten up the nerve even to climb that mast – let alone jump off of it.

Into the dark.

.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 0px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 0px;}My Father Finally Succumbs to Old Age

My father was a young man until at the age of 87, he had a stroke while fly fishing from his canoe on Kidney Pond, near Mt. Katahdin in Maine. He was in the act of casting a dry fly at a rising trout just before sunset when suddenly he was very dizzy and knew a stroke was coming. He put his fly rod down carefully in the canoe, slid off the seat and lay down in the canoe so that he wouldn’t fall out into the water and drown. Then he threw up all over himself. The canoe drifted aimlessly in the middle of the lake while the sky above him darkened, the stars came out, and he realized he couldn’t move his right arm or leg. The whole right side of his body was paralyzed.

He knew that his friends at Kidney Pond Camp where he was staying would check to see if he had returned, because that’s what all the fishermen did for each other every evening when they got back. Soon they’d get in their canoes and come looking for him. But my father wasn’t the kind of person who lay around waiting for others to do for him what he could do for himself. With his left hand, he patted around himself until he found his paddle, and he started to paddle home. I still don’t know how he managed to reach up over the gunwale with only one hand, while lying down, and get any leverage on the water – nor how in the world he knew which direction to paddle since he could only see straight up. He was only a few hundred yards from the dock in front of his cabin when two of his friends found him and towed him the rest of the way home. The right side of his face was also paralyzed, the skin and the muscles beneath it sagging. He could talk, but only haltingly, and his words were slurred.

It was several hours before the ambulance arrived from Millinocket and took him to the hospital there. The next day my father was transferred in a private plane to the Greenwich, CT Hospital, near his and my mother’s home. I got the news in London where I was attending a conference and rushed home on the earliest plane I could get, and the first thing I saw when I walked into his hospital room was my father sitting up in bed trying to chin himself from a bar that hung above him from the ceiling on two wires like a trapeze. A nurse stood beside the bed, one hand on his paralyzed hand, squeezing it for him around the bar.

“Hi, Dad,” I said, as cheerily as I could. He didn’t answer. Instead, he raised his eyes to the bar above him, and pointed to it with his chin, as if to say ‘Don’t interrupt.’ He made the same grimace of exertion I’d seen a thousand times, widening his mouth, baring his teeth, squinting his eyes almost shut, and strained to lift himself, willing the muscles of his right arm to activate – commanding them to do their job, the way they always had for 87 years. They disobeyed. He tried again, and once again. And still again. Each time the left side of his body would rise a slight amount, and his right would not – he was a boat with a list to starboard. At last, the nurse took his right hand off the bar and laid it down beside him on the bed, like someone putting something back in a bureau drawer. “We’ll try again, this afternoon,” she said.

It was no surprise to anyone who knew the power of my father’s will that he got the use of the right side of his body back, along with a full command of speech. The stroke had done no harm to his prodigious intellect; it stayed intact until very near the end ten years later. Nevertheless, at the moment of the stroke, he finally became an elderly man. Before that time, the adjective just didn’t fit. After it, he never got back enough of even the mild athleticism it requires to put a canoe in the water and paddle out into a lake, nor to hike through the woods, to outlying lakes carrying his fly rod and his lunch. His timing at tennis doubles became so abominable it rendered the game impossible. He and my mother made the decision to trade independence for security, and moved into a retirement complex. My brother drove them from the house on the shore of Long Island Sound they’d lived in for fifty years to this new place where everything would be taken care of until they were dead.

“As we drove out of the driveway, they never looked back,” my brother told me, his voice full of wonder. “They looked straight ahead.”

.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-3{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-3 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-3{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-3 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-3{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-3 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-4{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 0px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 0px;}Miss Henry

Miss Henry, our 7th grade teacher in the Riverside, CT public school was a very large, very round person. When she stood at the front of the room, it was hard to see the blackboard.

On the first day of school, during lunch recess, when all my classmates were on the playground, and Miss Henry was in the teachers’ lounge, I sneaked back into the class room and wrote a little story on the blackboard attributing the presence of a large crack that had been present for several years in the cement path to the school’s front door to Miss Henry’s having walked on that path on the very first day of her employment. I went on to claim that the Principal had told her never to walk there again.

I think this was my earliest venture into narrative fiction, a fairly good try for a seventh grader. I especially liked my depiction of the inner thoughts of the amazed principal in which the word freak appeared several times, and I was clever enough not to adulterate the punch of the story by explaining how Miss Henry had managed to enter the school every morning since.

I assumed Miss Henry would walk back into the room, see what was written on the blackboard and demand to know, “Who wrote this?” None of the girls would answer. And all the boys would shout, “I did!” All through the sixth grade this tactic had worked. Such fun!

But Miss Henry paid no attention to the blackboard when she returned. It seemed she didn’t even see it. I can’t remember what we did that afternoon. Whatever it was did not require a blackboard. We kept waiting for her to turn around and see the blackboard and fly into a rage. Finally, just seconds before the end of the day, she looked straight at me, smiling kindly. “You spelled cement wrong, Stevie,” she said. “It starts with a c not an s.” Then the bell rang and we all trooped out. From that day on in that class my name was Stevie. Everywhere else it was Steve.

I have no idea how she knew who was the culprit. But I do know it is hard to be a wise guy with a tendency to cruelty when your name is Stevie.

So, after a while, I stopped.