Miles Craven's Blog

February 14, 2017

Across the Great Divide – Afterword

[image error]EVERY WORD IS true, and you’ll want to know how it all turned out. Part of the answer is right here in this room where I sit facing the mirror and my aged face. Assuming that the day of my birth is correct, I am 74 years-old. Olu is brushing my hair as she used to do, only it’s white now, the sliver threads coarse and thin. Age hasn’t whitened her crop, least none that you’d notice from afar. Only up close, or here in the mirror, can you spot the grey among the black. Neither of us likes the grey, in hair nor in any walk of life. Irrational yes, unrealistic, downright foolish, but there you have it – the world we have known through our long lives has worked in black and white. It won’t change now, not even with the coming of the railway that chutters and hoots in the valley below.

‘That’s right, sister,’ I say, ‘you know how it’s done. You always did.’ She’s as gentle with the brush as she was all those years ago when she first came to Belle Isle. We ceased to live there a long time ago, preferring the Grange which is easier to heat. That Vine lived here matters only in a positive sense; we feel the old walls close around us like the skin of our vanquished enemy. Soon it will be time for our walk; we always go this time of day, late, on the edge of dusk, whatever the weather or the season. It is August now, in the year 1834.

I’ve put off writing this epilogue, struggled to write it at all. I knew it would be the hardest task, bridging the gap between then and now, saying farewell to the old times – nearly 60 years ago, a lifetime for most, few of the old names left alive. So much water has flowed since I left off telling my tale. The canals of the landscape are matched by canals of life. Canals more like rivers with their many twists and turns, yet in hindsight one straight course leading to the present juncture. The only one I would settle for, and soon the end of the line.

First that long gap since 1778, or its tell-tale points. A double marriage just a month after Vine’s death. Yes, he was dead; and no, I never paid the reckoning. Not for murder, not for duelling, technically illegal even among men, and unheard of among women, though I was no ordinary woman. A crime for sure one way or another, not that it mattered in the end. There was no law in our village back then; in Father’s stead we were the law, and we disposed of the corpse as we thought fit. It’s there yet, buried shallow on account of the frost at the foot of Hautboy Hills, unmarked save by some amphibious weeds at the side of a small pond where the roach leap in summer. I never got round to burying him deeper, never got round to regretting his death for I look at it this way: if God exists He’ll forgive me; if not then He’s just like Vine – not worth a second thought.

But I was saying, about that double marriage. I married Robert Strong and Joe married – as he’d always wished – Caroline Stroud. Her father consented, and why shouldn’t he? He had plenty to atone for, as Joe told him with his new-found steel and pride. Joe’s been dead these eight years past but his son is master now, and if you ask me he’s turned out just the right mix of hard and soft, as his father had wished. He’s a man all right, but he doesn’t see fit to prove it twelve hours out of every day. And his name? Why George of course, after our father. There’s a daughter too, named Nell after me, and those old enough to remember can see the likeness. In looks only, I hope, and not in temperament. My character as it was then makes me blush with shame yet deep down, beneath the wizened skin of age, I wonder how different I really am; how different I wish to be.

I don’t wish to change my request, one my dear nephew was happy to grant, no matter those frowns in the village. By the time we’ve finished our walk tonight bonfires will be lit all over the estate to mark the official end of slavery in the British colonies. And, by the same token, right here on British soil, though in truth it withered away long ago. It will soon be the season of bonfires, that dying time of year. The serenity that comes with autumn is like no other; it’s a time of beauty tinged with sorrow. I think of Betty, who died old and blind in her last autumn; I think of Joe, whose favourite time it was. He was a good man, and Olu agrees. Robert was a good man too, she adds, and who am I to disagree? Yes, a good man though the children he gave me all died young, and the smallpox took him at 39. Ah, more sadness and regret, more mingled pleasure in both!

Yet still we live, Olu and I. Try to picture us arm-in-arm in our adopted manly guise. They call us the Ladies of the Grange but some are unkind, they ask behind our back if we are really women at all. And this in spite of Olu’s remedies, her tireless doctoring among the local poor. We have summer and winter garb, variations on a theme that has no grey. For half the year we wear black, with pinches of white at the collar and cuffs. Come summertime it’s white on the outside and black beneath, either way a familiar sight. We still do what we did back then, walk on the moors where the air is thin, wash our feet in the stream by lantern-light, leave offerings to the spirits of nature – more than ever as our end draws near. And Olu talks again of the powers of obeah, though nothing of the sort that killed the Reverend has either of us seen since. An English coincidence after all perhaps, or maybe his death was not as I remember; it was all so long ago.

On we walk this nearing twilight, the sun sinking behind the hills, the moon risen big in its stead. Aside from the colour and the small difference in height, we’ve the same stooping posture. For support I have my stick and Olu her spectacles. A little spaniel bounds along at our feet and one day I’m sure he will trip us up and bloody our noses. For now we are what we are – sisters where we might have been lovers. They say we have kindly faces but we rarely smile, and no one has heard us laugh. They say, and who’s to say they’re wrong? that we’ve each forged our self in the other’s image, that she’s my blacksmith and I her white. As for what it means to be black or white, man or woman, rich or poor, I say only this – say it as I walk with Olu through grounds where Father rests in the same vault as his wife and son, that family – blood – however it is made, is allimportant. Whether it is all that matters is another question.

FINIS

February 7, 2017

Across the Great Divide – Chapter Sixty-Nine

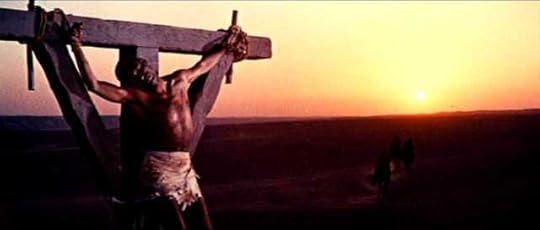

[image error]AT SEVEN PRECISELY, the stage was set beneath the spreading branches of an ancient oak. The wind was light but icy sharp, pointed as the rapiers Vine would have brought had it been a duel of swords. But pistols it was, a pair to choose from on each side.

‘Remember, aim true,’ Nell said to Joe when she handed him his choice of guns balled and primed.

‘No, remember to stand firm, it’s all I can do,’ he replied, his hand shaking as he held the piece. ‘See?’ he said with a sniff. ‘How can I aim true with a hand like this? Look at his hand, his is not shaking. His face says it all. He’s like a gargoyle that’s had the cream.’

‘You mean a cat, Joe,’ she corrected him.

‘No sis, I mean a gargoyle, a cat is too handsome for him.’

It had come to this at last, and all Nell’s arguments were spent. He would fight after all; he wouldn’t run, as they’d wanted him to do while there was still time. They would go to a lawyer in Leeds, they’d said, and make good his claim. It would all end well, he needn’t bleed in the snow like this. But no, he wouldn’t be denied the martyrdom their father would expect.

‘Less noise over there!’ cried Vine, removing his coat though the cold shot through him with bullets of its own.

‘You don’t like what you hear then?’ Joe called to him, his voice cracked, his eyes distant with thoughts of coming death.

‘I’m done with listening. I’ve expected so much, waited so long, I won’t give it up now. You think to keep me from what’s mine, what I’ve worked so long to achieve? I’ve slaved for this,’ he said with a glance at Olu. ‘I’ve grovelled for it, toadied for it, but no more – this time I come to claim.’

‘Is that all that matters?’ Joes asked him.

‘Yes, that’s all – what else is there?’

‘Life. Humanity. Masculinity in its different guises, all of them valid,’ said Joe with unwonted eloquence. ‘Mine perhaps more than yours. I think you wonder deep down what it is to be a man. I think a man like me unsettles a man like you.’

‘You think I give a damn for your girlish heart?’

‘You would if you thought about it, about your own girlish heart, but you can’t. A man like you would fall apart if he studied himself too closely. But it’s there all right, the woman in you, I can see it behind your eyes.’

‘And what’s behind your breeches? that’s what I’d like to know. Have you a prick there or a quim? Let’s get this over with. Come up close, back-to-back so I can feel your sweat. That’s it, good boy,’ he said when he’d obliged. ‘Now say the words Mister Strong – cock your triggers, gentlemen. Thank you kindly for that small service. Now be good enough to count ten paces. You’re an educated man, it shouldn’t be too hard.’

Robert took a deep breath and started the count. The fall of seconds was uneven, the last one rushed, which threw Vine who fired prematurely and missed. His mouth twitched with suppressed rage then fell still. ‘We must do this right,’ he said. ‘Ask me if I’ll stand my ground – ask if I’m ready to receive his fire.’

‘Well do you? – are you?’ Robert asked, his forehead sweating despite the cold.

‘What do you think?’ countered Vine. ‘Look at me, I’m steady as a rock. Go on then!’ he urged Joe who hesitated. ‘Shoot! I don’t expect to be hit, not by a coward like you. See? I don’t even stand side-on to lessen your target. And when you’ve missed I shall go for my second piece. Shame to waste it when it itches to be fired.’

‘Kill him Joe, for all our sakes,’ said Olu, her tone dark and full of purpose.

‘Hold your tongue you Nigger whore …’

‘Yes, and whose Nigger whore? Tell them that!’

‘You tell them, I haven’t the…confound it!’ A blast of cold had made him shiver at last.

‘Haven’t the heart? For all those times you used me?’

Was this it then, her last great secret? Yes, and out it came, every sullied detail – her rape in the Indies, threats of death if she breathed the truth to Sir George, who may or may not have forgiven Vine, but he wouldn’t take the risk, not when ‘the black slut’ was the product of his loins.

‘Think I didn’t know the truth?’ shouted Vine. ‘He knew that I knew and it started to come between us. I had to work him round to my way of thinking, which was all for the best as he’d say. He’d thought he was rid of her for good, and so did I when I gave her a parting gift she’d not be likely forget. I’m not talking speedwell either.’ He’d meant her rape there, in those very grounds, the night she left for London.

‘Come on, fire whelp! Give us all some merriment!’ he baited Joe, who still trembled, still hesitated, but who had stood his ground, his task complete he’d hoped.

It might have ended yet in Vine’s favour had he not gone too far. He said how Olu had cried out not in pain but in pleasure when he took her hard as he liked with plenty of blows thrown in. ‘Just like the old times on Barbados, but with ground cold beneath her black buttocks instead of warm. I took her mother too when Sir George weren’t looking, the black bitch were carrying my brat not his when she hang …’

Imagination for Nell became reality; the gun was in her hand; she felt its weight, its balance, she pointed it and cocked it, placed her finger on the slim little trigger. They told her afterwards that she’d got up close, that his smiling eyes doubted her intent right till the last moment, when they’d suddenly kindled – curdled, said Robert, who’d taken the weapon from her (gently) when she’d put the ball through the attorney’s skull, nearer to laughter than tears. Yes, she’d been close when she killed him, close to the oak tree, so close that the ball remained embedded for years to come.

February 1, 2017

Across the Great Divide – Chapter Sixty-Eight

[image error]THE CHALLENGE CAME while it was yet dark. Vine, who’d been drinking hard, knocked on the door with a leering grin just after four. He’d waited deliberately, guessing rightly they’d be too harassed to sleep.

‘I wish to see your brother,’ he growled when Nell answered. She’d seen the pistol at his belt, loaded or not she couldn’t tell, and the stout cudgel in his hand.

‘And if he doesn’t wish to see you?’

‘Wish has nothing to do with it,’ he said, ‘I am here and he will see me. You are back safe and well I see,’ he added, as she led him reluctantly across the hall.

‘No thanks to you, sir,’ she replied, which made his laugh echo in the empty spaces. ‘You thought you’d finished us but you haven’t. We have come home – all of us – to claim what’s rightly ours.’

‘I admire your mettle, Nell, you’re a real fighter. Even now I’m willing to let bygones be bygones. When this business is over, who knows what offer I might yet make you?’

‘And what business would that be I wonder?’

‘I think you already know,’ he said, as they entered the drawing room. Joe was on his feet waiting. He was struggling for his dignity, fiddling nervously with the lace at his throat.

‘This won’t take long,’ said Vine, strolling bodily towards him. ‘I may not stop, you know, I may keep walking, knock you over like a skittle …’ He halted abruptly, his face just an inch from Joe’s. Joe was trembling. ‘Oh you whelp, you puppy, this is hardly worth the trouble. I’ve killed better men than you and eaten them for breakfast.’

‘Wh…what do you require?’ Joe asked as he shuffled and sniffed.

‘What do I require?’ returned Vine, laughing wide-mouthed. ‘Why, everything kind sir, everything. Lock, stock and barrel,’ he said, aptly fingering the muzzle of his gun. ‘I didn’t think this would be necessary but never mind, so long as the Devil doesn’t mess with my well laid plans. I don’t like your girl’s face, sir, it revolts me in the pit of my stomach. It’s one of those faces a real man can’t help but strike.’

‘You damned ape!’ Nell cried when he’d clipped Joe twice across the mouth with the back of his hand. Joe, dabbing his bleeding lips, the blood so bright against his livid face, was on the brink of fate.

‘Come then, hit me back if you dare,’ coaxed Vine belligerently. ‘Stay where you are!’ he shouted when Robert hurried in with Olu. ‘Mistress here called me ape, she should have called you that,’ he said pointing at Olu. ‘But no matter, this little business is almost done.’ He placed a hand affectedly to his ear. ‘Did I hear the challenge I seek?’

‘You did indeed, sir,’ said Joe. ‘I will meet you at a place of your choosing. This minute if you wish.’

‘But it’s still dark,’ said Vine, with dark jest to suit. ‘Nay lad, dawn will do. The cold light thereof,’ he said, with a wink at Betty who’d come in at the other door. ‘Pistols or swords or don’t you care?’

‘Pistols,’ said Joe, as if he’d seen a glimmer there, however faint.

‘Pistols it is then, out there in the park – shall we say three hours from now?’ He had his timepiece flipped open, closing it with a click as he turned to leave. ‘Watch out!’ he joked, as a log spat loudly in the grate.

Nell sat with Joe the rest of the night, they all did, keeping him company in the study while he readied his guns. They were his father’s guns, the ornate pair Nell had watched with such interest that day, so long ago now it seemed like another life.

‘Aim true, Joe,’ she said, ‘it’s your only chance. You do know that Father used them at least once. Killed with them – at least once.’ She eyed them snug in their felt-lined box. ‘Shot some poor soul right between the eyes. Don’t know which one he used, don’t suppose it matters.’

‘He was a crack shot. What do I know about shooting?’

‘You know how to take aim,’ said Olu, her tone more warm than cold. A change had worked its magic of late; she accepted what they were in all but name – brother and sister. ‘You know how to pull a trigger and fire. I shall prime them and load them for you. I know how. Be thankful he allows you your own guns. Man like him act as his own cheating second, give you bad gun that blow itself open in your hand. Man like him give you short charge so the ball won’t carry.’

‘Good gun, bad gun – it’s all one I fear.’

‘Try to be a bit more hopeful – no?’ said Robert, his chin resting on his hands as he sat pensive at the table.

‘At least I shall stand firm and not run. You can tell the world how it was when I’m gone.’

‘Code Duello or not,’ said Robert, ‘the practice is still illegal. This doesn’t have to be, you know, we could have it stopped.’ But the same question was on all their lips: by whom?

‘No matter. I shall prove myself a man even if it kills me,’ said Joe, who forced a wry laugh. ‘As it will of course.’

Nell glanced at Olu; she couldn’t help thinking, no hoping! she still held a card up her sleeve. Robert too, looking at her gravely, was hoping the same thing. Hoping that the hope was not forlorn.

January 24, 2017

Across the Great Divide – Chapter Sixty-Seven

[image error]TO BE FACED come rain or shine, he might have added. Or come more snow, of which there was much as the coach pulled away next day. Yorkshire, as they travelled through it at last, lay hushed beneath a vast cape of undulating white, and when they stopped now and then to stretch their legs, gone was the creaking of coach springs and the rolling drum of the wheels; in their place a silence so quiet it went beyond the silence of the night, went beyond the silence of the grave till it merged with a noise faint, pulsating and undefined. It was the noise of tortured thought.

Whether outside in the snow or huddled together in the cab, Nell was thinking of her father. What else was she to think of other than his loss, his warning of trouble ahead? Death, it seemed, was everywhere in that endless white below and endless blackness above. Death was king in all its glory, to be accepted with grace, not fought against or denied. Acquaint yourself with me, the inevitable, the immutable, resign yourself and don’t be afraid, said the landscape in its language of silent speech. Speech of Heavenly cold contending with the cold of Hell in an age-old battle of wills. It wasn’t clear which had won in the past, which was winning now and which would win in the future. Nor was it clear what was good or bad. Or whether living was better than death. Their only choice was to go on.

Home, then, having changed their carriage at Leeds and parted company with the Fly. Horseford itself lay snow-bound in the dark as they glided through on wheels that felt like runners on a sleigh. Each cottage, each workshop, every inn and tavern exuded glow of candle or fire, a sight not repellent yet oddly not inviting; wariness in every light, a challenge perhaps or a warning not made clear.

The carriage drive through the park with its snow-burdened trees was slow and dream-like, heavy with expectancy. Still no one spoke, each was alone with his thoughts, solitary as a clam. Lights from the house twinkled here and there through the laden branches overhead, dancing with the motion of the weather-beaten coach. The machine skidded as the driver applied his brake, reining his beasts with a raucous cry. His whip cracked, the horses neighed and stamped their feet with cold.

‘Is the master at home?’ he asked, opening the door and folding down the step.

‘The master is dead,’ said Joe before he could think.

‘Sorry sir, begging your pardon,’ said the driver, ‘no offence intended. Shall I ring for assistance?’

Nell, not Joe, told him to unload their things and consider his work done. ‘Very good, Miss,’ and when Joe had paid him and they stood with their belongings before the great Corinthian columns made whiter than white by snow, she was forced to contend with her tears, as Heaven and Hell had seemed to do upon on the frozen moors. She didn’t cry; something stopped her, good or evil, she didn’t know which. And whose face would greet them this wild night if greet was the right word? She was braced for the worst.

And rewarded by the best. ‘Betty!’ she cried, seeing her in her night cap, holding a candle in a little dish. She looked older, wiser, a greying mother to her former self.

‘Oh Miss, Miss, it’s you ! – how you frightened me! You too Master Joe – and who’s that you have with you?’ She lifted her candle. ‘It can’t be – can it? So many wanderers returned …’

‘Don’t say any more Betty, not till you’ve heard it all. You’ve plenty to tell us yourself no doubt.’

‘That I have, Miss, that I have,’ she said, holding the door so they might come in from the cold. ‘You look like four sheep dug out from a snow drift,’ she added, standing aside to look them up and down. ‘Lord above, what’s to become of you?’

‘Now listen Betty, we must get one thing straight at the outset. Have we anything to fear tonight? Is Vine inside?’

Betty drew them to the foot of the stairs, where she cocked her head to listen. Finding all was quiet, she said, ‘Oh Miss, you’ve no idea how things are here. That man crows like a cock night and day.’

‘Answer the question, Betty,’ said an impatient Joe. ‘Does he sleep at home this evening?’

‘No sir, he does not. There’s only me and the other servants, what’s left of ‘em. These walls have ears all the same, and they’re his ears. That man pleases himself just as he likes. It’s a wonder you didn’t see his light burning when you drove past his office just now. He works late there on all manner of papers. He’s getting things straight for himself if you ask me, straight for him and bent for you. Well he’s an attorney, isn’t he? Who knows what documents he got the master to sign them last few nights. He sat up late with him, you know, in his own room. When the master gets back …’

‘He’s not coming back, Betty,’ Nell interrupted. ‘Our father is dead. Kit too is dead. They died in the same accident.’

They escorted Betty to the drawing-room where the remnants of a good fire still threw off heat. ‘Oh Glory be,’ she said, her head in her hands as she wept. ‘Will all be well, Miss?’ she asked as a log snapped and crackled in the grate. ‘Can it be all well ever again?’

‘Our delightful Mister Vine, when do you expect him back?’ asked Joe, too fretful to sit. ‘You think he means to claim everything?’ he said before she could answer.

‘I’m sure of it, sir. He means you harm as well. There’s no one to stop him now.’

‘I shall stop him. I must,’ said Joe, who looked in agony.

‘You can’t mean to fight him,’ Nell said. ‘He’s a crack shot with a pistol and a flashing blade with a sword. You aim to choose between the Devil and the deep blue sea?’

‘I mean to stay and fight one way or another. I think at last I have something to fight for.’

‘We all have something to fight for,’ Nell said with meaning.

‘He never thought to see you again, Miss, I’m sure,’ said Betty. ‘You neither Olu.’

‘I’m sure he didn’t,’ said Nell knowingly.

‘He means to claim all this for himself, he’s said so more than once.’

‘You seem to forget that I am master now,’ said Joe, drumming his fingers on the table. ‘Father is dead. I am his heir.’

‘That you are, sir,’ said Betty to appease him. ‘I never meant no harm. And you’ll have me to serve you, have no fear. I’ll not be going nowhere.’

‘Me neither,’ piped up Robert, warming himself at the fire. ‘Only…only if there’s fighting to be done, I think I should go home and make my peace with my family first.’

Betty was looking at him from under her brows. ‘You’ll be meaning with your wife, sir? It’s just that…well.’

‘Come on, woman, spit it out.’

‘It’s only what I hear, and it’s not for me to say sir, not outright in front of everyone like this. You should go and find out for yourself.’

‘On a night like this?’ said Nell. ‘No Robert, you must stay here.’

‘But what does she mean?’

‘Betty, you must say what you know. You too, Olu,’ Nell added, ‘there’s no time left for holding back. We are home, where we all mean to stay. There must be no secrets now, only the truth can give us strength.’

‘You hear everything soon enough,’ said Olu. ‘When the moment is right.’

‘Well I wish to hear what she knows now,’ said Robert, pointing at Betty. ‘If Vine comes back full of murderous intent I may not live to find out.’

‘Very well, it’s your wife sir. Another man sleeps where you once slept. Rumour has it she never expected you back. Rumour has it, she never wanted you back.’

‘That’s enough Betty, you go too far,’ Nell said, watching Robert walk slowly across the room. He halted where his misery took him, beneath a portrait of Nell’s mother.

‘It’s all right,’ he said, feeling Nell’s touch on his shoulder. ‘Deep down I half expected it. She stopped loving me a long time ago. That business with my brother didn’t help. It shamed her, made her feel unclean. As for me, I still blame myself for not doing enough to save him.’

‘What else could you have done, dear Robert? Don’t blame yourself, not for that nor what your wife has done.’ His hand now rested on Nell’s. She saw the tear on his cheek and wiped it away with her finger. When he glanced her way she licked it and smiled. ‘Salty,’ she said, ‘like the sea.’

He gave her a tender look. ‘I hope there’s no sea between us.’

‘None that I know of,’ Nell said, conscious of the others and their shared embarrassment. Only Olu was looking away, namely at the window where she’d risen to look. Just what was she watching out there in the snowy dark?

‘Come back to the fire,’ Nell said to Robert in sterner tones. ‘We must talk strategy for this fight with Vine. You’re the closest thing we have to a lawyer, do you think he’ll have stitched things up so wrong for us?’

‘Depends what he got your father to sign,’ he said, biting back his hurt. ‘The way I see it, if the estate is entailed to Joe he’ll be hard put to make it all stick.’

‘But if he kills us all, every one of us,’ Nell said only half in jest.

‘Miss, may I recommend that you all eat something then try to get some sleep?’ said Betty, rising with the candle she’d placed on the floor beside her.

‘No food for me, Betty,’ said Joe, ‘but you may bring some brandy, for I’ve a need to fortify myself. What about you Robert?’

‘Yes, brandy, why not? Dutch courage and all that – what?’

‘Nell – Olu – will you drink with us?’ asked Joe.

‘No we will not,’ Nell said.

‘She’s right, Master, without a clear head the morning will be worse for you,’ said Betty.

‘Bring it for them, you hear?’ Olu snapped without turning round. ‘Let them find some peace while they can. You think he’s not out there this minute?’ She was staring out the window still. ‘See it, that light in the grounds? It’s his lantern. He hears the carriage wheels and he comes to look. He knows we’re back Why does he hesitate? – is he playing like the cat with the mouse?’

‘The law, surely we can call on it?’ said Robert.

‘Father was the law round here,’ said Joe. ‘The only magistrate for miles around. I wish he’d come now and get it over with. If I’m to die, why should I wait till morning?’

‘You’ll not die, Joe,’ Nell told him. ‘Even he won’t shoot you down in cold blood.’ But she knew the result would be the same: Joe was a gentleman, and gentlemen were bound by a certain code. A code which for Joe was a death sentence.

January 17, 2017

Across the Great Divide – Chapter Sixty-Six

[image error]‘COACHMAN YOU WILL go back with us now,’ Joe ordered.

‘When you’ve changed the horses,’ said Nell, while Robert rose beside her for extra numbers and Olu twirled her poker red at the end.

‘Who’s going to pay me for my trouble?’ said the driver as they headed out the door.

‘You could try the Leeds newspapers,’ she told him sourly.

‘This wouldn’t have happened in my grandfather’s day. Told what to do – by a woman!’ he grumbled into his hat, soaked through like the rest of him.

‘Times are changing,’ said Robert meaningfully. ‘A man like me knows it more than most.’

The landlady’s daughter, who’d offered to go with them, said they must travel four miles along the road they’d come by, then turn east the rest of the way on foot. The distance wasn’t great, just difficult for horse and wheels and what should have been an hour’s journey instead took nearer two. Then came the final leg, following the tracks of a carriage that had strayed from the road in the dark. At last the glow of lanterns was visible through the snowy murk, where the landlady, her two strongest stable hands and several men from neighbouring farms stood gathered on the edge of a crag.

‘There’s one down there alive but we can’t move him,’ she said when they’d joined her. ‘We’ve done all we can to make him comfortable.’

In the gulley below they could make out the broken outline of an upturned vehicle; one wheel was visible and oddly was spinning still. ‘Who is left alive?’ Nell asked as the snow stung her eyes like gravel.

‘The only one that counts,’ she answered. ‘The white one.’ Errands of mercy clearly had their restrictions, and there was no regret in her eyes when she noticed Olu’s colour. The girl was the lady’s slave, or if not what did it matter? – she was black, an object hardly worth a second thought.

‘You must tell me his name,’ Nell insisted.

‘He is Sir George Cooper of Belle Isle near Leeds. He is dying and he will die.’ The words in Nell’s ears sounded both distant and near, outside and within, real and unreal, but with a frenzied grief waiting to burst.

‘We have done all we can,’ the woman continued, ‘these men here are starved with cold. We have nothing to move him with, no doctor within ten miles. We’ve made him warm with blankets but it’s hopeless. His head’s broken. Don’t go down there, Miss, it’s dangerous!’

‘I’m his daughter, I must,’ and she plunged knee-deep down the snowy slope. Joe was behind her – ‘Be careful!’ – and Robert, outrunning him in a burst of conjured bravery, was at her side holding her hand as best he could. When she slipped, his grip was agonisingly tender; he wanted to share her danger, share her thoughts, which were these: why did the wheel keep spinning? and where had she seen it before? It was spinning with more propulsion that the wind could supply; it was spinning beyond its natural velocity; it was spinning with the force of another world, a world made real by the night that was black and the snow that was white. Her amazement was complete when she found Olu already there before her. She must have hurried down by a quicker route, though there were no marks of exertion and her breath came slow not fast. It was as if she had been there for hours, even days.

‘I see to this one first,’ she said, when Nell looked at her accusingly. ‘No one give him a thought but me.’ She meant the Chinaman, Kit, lying with his blood on the snow, and though she spoke the truth Nell didn’t care – why should she when her father was dying – and he would die.

‘You can’t do anything for him, Olu, though you might help my father. Please let me pass,’ she said, for she seemed to block her way.

‘You go in there, you might not like what you see. You might not like what you hear.’

‘That’s for me to decide,’ Nell answered as Olu stepped clear.

The upturned carriage had been propped up by a stout timber to enable the door to be opened. Sir George’s body was lying on the ceiling which was now the floor; it had a deathly pallor. His head was indeed smashed and lay on a cushion of blood congealed by the cold.

‘Fool that I am, Nell. Fool that you’re not,’ he said softly when he saw her face.

‘I am here, Father. Joe too.’

‘Yes, and there’s another,’ he said, endeavouring to see through the broken glass. ‘A doctor now, I hear. She tends him – Kit – does she hate me so that she’ll kiss a dead Chinaman before me? It’s my belief he drove us right over that cliff. I can guess too who told him to do it.’

‘Here, drink this, I’ve brought some brandy,’ Nell said, bringing the bottle to his bloody mouth. ‘It will stop you shivering,’ she added, tucking in the blankets the landlady had brought.

‘No, I am warmer than I’ve ever been. I’m warmer in the heart, Nell, where it matters. I want you to forgive all the wrong I’ve done you. I want you to share my last moments. She must come too, you must know the truth – I think she may know it already. It’s why she stays out there.’

‘Shall I call her?’

‘Yes, it’s all for the best – I mean it this time.’

‘And Joe? And Mister Strong?’

A weak smile escaped his lips. ‘Everyone, why not? The horses too. No, I heard them shoot those. I wish they’d have shot me. My head is bursting. No, no, don’t distress yourself, I can bear it a while yet. It will only be a while.’

‘We’ll move you, I’ll get ropes, a litter …’

He stayed her with a freezing hand. ‘Nell, it’s over. I’m ready to die.’

‘Don’t say so!’

‘It’s true. I’ve breath only for what matters. We’ve found each other for a reason. Think about it, out here at night like this – who would have wagered on its odds?’

‘You and your wagers,’ she teased, reaching for his gory brow then halting. So much blood, so much pain – what could she hope to achieve with her meagre comforts? ‘Before you ask, I forgive you my darling. I forgive you everything. You’re my father.’ His blood was spilled and he was right, at least in part – it was thicker than water; his blood was her blood and she ought to be proud. ‘I’ve been a haughty, foolish girl.’

‘You did what you thought was right, for that I respect you. As for myself, I make no apologies for what I’ve been in life. I dealt in human flesh, it made me rich. We must strive for what we have in this world. There’s no room for weakness. But no…’ – he tried to shake his head – ‘…I lie, it was not so simple in the end. I’m sure it never was.’ He surprised her with a memory she hadn’t known they’d shared. A one-legged blackbird whose plight had touched her deeply last winter had touched him too when he’d spotted it through his casement. In its sweet voice towards dusk one day in spring he’d heard its notes unquestioningly pure and innocent. All it wanted, all it expected, was to live and sing, and in its yellow beak, black plumage and fluting call he’d felt the whole of humanity, black and white, tapping at the door of his heart. Its death when it came – he found it lying in the park – stood for the death of everything that had ever lived. It was a moment of change, of revelation that every living thing was connected one with the other in an endless chain.

‘So did it make you regret – like John Newton – your part in the slave trade? And what now of the death of poor Hector?’

But just then Joe’s face appeared at the upside door; it was all so topsy-turvy just like the picture in the Pemberton house. And still the wheel spun silently – no, with the faint whirring of a spinster’s wheel or the whoosh of the sails on a small boat. The gentle sound was drawing their father to his death, to everlasting peace Nell hoped.

‘Come in Joe,’ she said, ‘there’s room I think.’

He joined her and they crouched before him, doing homage at his makeshift bed. ‘You did your duty well, Joe,’ his father told him, ‘you found my girls.’ Joe’s shoulders stiffened in sheer delight. ‘I give you my blessing at the end, though I leave you with a fight on your hands. I think you know which. I’ll be looking down on you if He gives me the chance, I’ll be making a wager on you winning. I’ve never welcomed long odds, but in your case I’ll make an exception.’

‘Thank you,’ said Joe, unsure if he’d heard a complement. ‘But Father, you said girls, you thanked me for finding your girls.’

‘Please, if you can, make room for Olushegan. You see I’ve always known her name.’ His eyes were grown glassy. There was no time to lose, yet they didn’t know what to expect.

‘Olu – you must join us,’ Nell called, watching her chant her secret prayers over Kit’s dead body; it was stiff in the snow-light, shining like polished wood.

Reluctantly, but without protest, she crawled in and made it four. Robert, whom no one invited, had pressed his face to the glass behind her, not presuming to intrude. ‘Now,’ Sir George began, ‘I must get to the end in a number of senses. I shall die here, not the best of places but it can’t be helped. I shan’t go till I’ve told what I came so far to tell. It’s fitting that you’re all here to hear it, against the odds once again, so there must be a reason.’

He waited to get his breath, to swallow some blood, then told the salient points. He cut to the heart of what he knew would shock – shock them all except Olu, for she alone, the object of what he had to say, looked unmoved. She was his daughter, born if not in love then at least in something that swam in the same sea. He had cared for her mother as far as he was able. He couldn’t help it that he found her colour distasteful, poor substitute for what he valued so highly – a white woman’s skin. Not that he’d tasted much, if any, beyond the confines of the marriage bed: he wasn’t, when all was said and done, a passionate man. His sense of shame had been strong, less so for coupling with a Negress than for sullying the reverence in which he’d held his wife.

As for Olu, she was, like it or not, his daughter. She was, like it or not, his responsibility. She was, like it or not – and this was the hardest part – half himself. As the years passed he couldn’t ignore it, and when the time came to quit Barbados for good, he hadn’t the heart to leave her behind. Hence the need for excuses to hide his shame, hence the spurious wager, hence the ruse of exotic gifts. He’d hoped nonetheless to make her a lady, as far as was feasible for one of her kind. What he hadn’t bargained on was his jealousy when he saw the growing closeness between the two girls. To find himself displaced, reduced to second best in Nell’s affections put pay, or so he’d thought, to his sense of duty towards his black daughter who was, when all was said and done, unexpectedly black. He excused himself with the old hatreds of her culture, her magic and her skin. In all this he was encouraged by Vine, who sharpened every barb of his life-long guile to mould him the way he liked. And so in the end he had banished her, thinking it was for good. And later he had banished a second daughter, thinking that was for good too.

‘But that man, Vine,’ Nell beseeched him, ‘why did you let him get so close?’

He smiled again in spite of himself. ‘I let in only one, just him. My creation, my monster. I don’t expect you to understand. He came from so little, like me. He was ambitious, so I helped him. But my protégé got the whip hand.’

‘And Lord Pemberton? It seems they worked together at the end.’

His smile grew weaker and finally disappeared. ‘His Lordship always wanted Olu, I knew that. I saw how he looked at her. Another sin, I’m afraid – I made her part of the marriage match, to sweeten it like the sugar that made me rich. And there lay another way to be rid of her. Another way to regret.’ His glance at Olu was full of sorrow. ‘I thought the business done with, but I was wrong. The deal was off but His Lordship still claimed his sweetness. And why? Spite I expect, spite and endless desire.’

‘I’ve been all at sea, Nell,’ he said at the finish. ‘I still am and will die that way. All I know is what I’ve come to know these last few weeks – that I feel such love in my heart as to make me sick with grief. I must admit some wrong, even now I can’t admit all of it, but I must admit some. I want – need you all to forgive me. All of you…’ – he held out his hands – ‘…I wish to die in peace, the only peace I deserve.’

Nell took his hands, both of them, the gesture went without saying. Joe too, because he’d craved this moment all his life, did the same. Robert outside was also nodding; he understood now his own ill treatment at the baronet’s hands; likewise that defence of his highwayman brother, the reasoning being that any kindness shown to Olu placed in stark relief a father’s callousness towards his charge.

There remained only Olu, reticent as always yet changed by her time in London. Mechanical though her action was, she reached out and added her hands to the complex clasp. There was no love, no forgiveness in her eyes, but neither – and it was the most any of them could hope for – was there hatred. In her single glance was hope; hope that the human race in all its colours might one day live in something – something that swam in the same sea as love.

‘Now go,’ were his final words, ‘go home and face what you all must face. I wish you well and all the luck I’ve known. All told, I’ve had more than my fair share.’

He died where he lay, and he couldn’t be moved for several days. Kit neither of course, whose death, as Olu insisted, should also be mourned. Joe and Nell arranged with the landlady to have the bodies sent north for burial and to forward the bill for her costs. They daren’t stay beyond a few miserable hours; as their father had said, they had something to face: his creation, his monster.

January 10, 2017

Across the Great Divide – Chapter Sixty-Five

[image error]IN THE CRUNCHING snow and slippery ice their conveyance skidded out of London with a lusty blow of clarion ten minutes late of the appointed hour. They had the carriage to themselves on such a wintry day and it went without saying that all that was found up top was the leather-bound bundles of London news and the driver who sat beside them. He was a large man in muffler and greatcoat, whose figure was a hunched white mound long before they’d reached Hertfordshire. Here, where the coach banged on the rutted roads as if it had no wheels, where the landscape beyond the frosted glass was one shapeless void of grey desolation, it was poor wager that they’d travel another mile of the Great North Road. This was the first coach out in days, a trial run to see if journeys were possible and links re-forgeable with the frozen north. It was possible, the cocky driver assured them; he’d driven through worse, while his grandfather, in the bleak winter of 1709, had driven through snow storms unknown to Russians, while birds fell dead from the sky. The key to getting through was outriders, he explained, and at the next inn, just beyond Ware, he promised to engage them and bill his employers for the cost. There might even be a reward if he got through. Those northerners at the Leeds newspaper offices were ravenous for the London gossip, not to mention the latest news from the front, and they would have it, he said, and pay handsomely for the privilege. But as Nell looked out again on the cold windswept scape, where the snow broke in pelting flurries against the rattling glass and caked its corners white, she began to question his optimism. She even wondered if he was there still upon his box, or whether he’d long departed and the coach bumped along unmanned on its ghostly way.

Foolish rather than brave, Joe saw no need to worry. ‘We’re going home, sis,’ he said, blowing on his hands, which he’d taken from his gloves to inspect. ‘It’s where we belong. All of us,’ he added, with a quick glance at Olu.

‘But what are we going home to?’ Nell asked, contending with her fear as a flock of winter thrushes flew past, their underwings red as blood. ‘If things are coming to a head, which I think they are …’ – she couldn’t say the rest, wasn’t sure what it entailed.

‘What will be, will be,’ said Olu softly. ‘We have all made our bed together.’

Joe’s eyes kindled and his tongue sought his lips in childish wonder. Again came that look he had given her a moment ago, a look of interest, maybe even of longing.

‘What’s to become of me? – that’s what I’d like to know,’ said Robert, picking at the seam of his threadbare coat. ‘At least you’ve all got a home to go to.’

‘You have a home too, Robert,’ Nell told him. ‘You have a family waiting.’

She felt his urge to speak his mind. ‘They expected me to make my fortune,’ was all he said. ‘I can’t go home poorer than I went.’

‘Have no fear, Robert,’ said Joe cheerily. ‘Something will turn up. I’ll see to it.’

‘You’ll see to it?’ Nell asked, shooting him a glance.

‘We’ll all see to it, together,’ he said, in hope. ‘Won’t we?’

They seemed a sorry party: the men feeble in their manhood, despairing, looking to the women to save them, while they, who felt the same despair, must hide it like mothers from their children. Nell was thinking of Olu and who felt worse – Olu because her fate was so uncertain, going home to the man who’d banished her and another who hated her for reasons yet unclear; Nell because she had no magic to count on, doubted there’d been any in the first place, all a chimera of her own making. Or perhaps Olu, sensing a bigger child than herself, had fed Nell’s sense of wonder like a sparrow feeds a cuckoo. She’d said nothing of her recent captivity, so Nell asked her now – because the intimacy of the carriage encouraged it – if her father had harmed her.

‘I not see His Lordship but I heard his instructions through his men: gentleness, kindness, not a hair of my head to be harmed. You find that strange?’

‘Only a little,’ Nell said, for the news in itself wasn’t startling. She remembered his allusions to Damiens’ terrible death, his attraction and regret when it came to extreme cruelty, his apparent mellowing with age. She wondered if Olu was a means of redress, as well as power and pleasure.

‘Well it’s not strange, it’s usual,’ Olu said to disabuse her. ‘A man like him wears two faces, one here in England, one over there. He not show his other self – his true self – till he gets me back where I came from. He do with me what he likes on his tropical island. There, five thousand miles away, he can be the beast to all his beauties.’

‘Yes, yes,’ said Joe as he looked at her, ‘you are a beauty. I’ve never really seen it till now.’

This time she returned his look, not with scorn as Nell expected, but with wary regard not at odds with her question: ‘Will you be the beast out there, sir? – when you go to his neighbouring island?’

‘Now steady on, damn it all,’ said Joe, caught unawares. ‘We’re not all animals, you know. Take my father even, he can be hard, he can be cruel – God knows, I know it more than most…’ – he broke off for he’d gone too fast – ‘…but with women – all women, he shows respect, behaves with impeccable decorum…He’s not your everyday cultured gentleman, not a man for lace cuffs and piquant repartee but…well I think you know what I’m saying. I’ve inherited at least that from him…I do hope.’

Nell was looking sideways at Olu, gauging her reaction to his muddle. She’d never said outright about Sir George’s behaviour in the Caribbean, when all civilising influences – and by that she meant the women – were gone. But she was struggling with herself, struggling with something.

‘You have still so many secrets, Olu, why not tell them at last? What harm can they do now? We’ve come so far together, we’ve come through so much, all made our bed together as you said so yourself. We are all friends…’ – she looked at the men and got their confirmation – ‘…you see? I rather think we’re the best friends you’ve ever had,’ and before she could take umbrage she added, ‘you’re certainly the best friend I’ve ever had.’

‘Mine too,’ said Robert, ‘most sincerely – yes?’

‘Yes…to be sure…mine too,’ said Joe fondly. ‘Can’t say I’ve ever had a proper friend, not even a fair weather one. But when I’m Lord of the Manor, who knows hey?’

‘If you Lord of the Manor,’ said Olu, and her meaning struck home. ‘All things coming to a head,’ she went on presently, ‘so no use thinking what might be till that head is faced. All will be clear one way or other. I promise you that,’ she said, with a sidelong glance at Nell, as if to even things. Nell saw the whole world in that glance, the whole world she had lived till that moment; she saw too the world as it might become, though the vision was blurred, as if the landscape outside had burst into the coach, black, snow-bound, scarred and ridden.

The weather cleared this side of Royston but it was only a welcome interlude. As they left the town behind, the dreary bleakness returned and the wind resumed its moaning monotony. They had the outriders now but progress was slow still and they reached their next inn at eleven at night. Here at the Dog and Gun close by Sandy in Bedfordshire the stable boys were loath to stir, and with only one lantern between them made fools of themselves slipping on the ice as they struggled with the harnesses. At length the horses were quartered in warm straw and the little party seated round a glowing fire in the inn’s cosy parlour. Joe called for meat and hot posset from the apple-cheeked girl whose mother, the landlady, was gone on an errand of mercy, taking along the stoutest men in her employ. News had come that a vehicle had been spotted turned over in the snow at the foot of a deep chasm. Speculation linked it with another machine which had passed earlier, a private carriage making for London at dangerous speed.

‘Poor devils, if they’re trapped down there on a night like this,’ said Joe, rising from the settle to warm himself at the fire. He drank his posset and lifted his coat-tails to let in the heat. ‘I say, you don’t think we should be lending a hand do you?’

‘We’ve only just got here,’ said Robert who sat beside Nell. ‘I’m hungry, I’m thirsty, and now the warmth of the fire has hit me I’m downright sleepy. And you want us to go back?’

‘But Joe’s right,’ Nell said. ‘We should go back. If the landlady has gone it’s the least we can do.’

‘Of course, I didn’t mean to sound uncaring – what?’ said Robert, quick to make amends. ‘You know how much I respect your judgement, Nell.’ Tiredness had lowered his guard, failed to hide his affection.

‘Thank you, Robert,’ she answered, moved by his sincerity, touched by something else, her instincts told her what. ‘You’ll come with me then?’

‘Of course I’ll come with you.’ He hesitated, fighting his cowardice. ‘I’d be delighted – no?’

‘You won’t get me going back, or my outriders,’ said the driver, who’d entered shaking snow from his bulk. ‘And if you go back alone, who’s to say we’ll be waiting when you return?’

‘You will wait,’ Nell said. ‘I order it.’

‘You order it?’ he asked amazed as he stood with his pie and porter in the doorway. ‘And who do you think you are?’

‘I am Nell Cooper, daughter of Sir George Cooper Baronet of Belle Isle. I didn’t think it needful to tell you before but I’m telling you now so you won’t forget.’

‘And I’m telling you that I’m that same baronet’s son, Joseph Cooper Esquire,’ Joe announced as he rose.

‘I’m – nobody very much,’ Robert volunteered with a humble shrug.

Olu, whose turn it seemed to speak, said nothing and stirred the fire with the poker. This, she seemed to be saying, is my answer, make of it what you will.

‘Wait, begging your pardon, Miss,’ said the landlady’s daughter, who’d bided her time, ‘but did I hear you say just now that you’re the daughter of a baronet?’

‘You did. What of it?’

‘It’s just that – it might be nothing you understand – it’s just that the man who came to tell us of the accident said there was a coat of arms on the side of the carriage, how he saw it distinctly in the glare from the lamplight as it shone on the snow. It was a fine gent’s coat of arms, a baronet’s if he wasn’t mistaken.’

‘This coat of arms,’ broke in Joe, ‘did he say how the crest was fashioned?’

‘Yes he did, sir. He said it was unmistakable, done as a pair of crossed foxes.’

‘It can’t be…can it?’ Nell asked, putting down her posset untasted. ‘But how? – why?’

‘There’s only one way to find out,’ said Joe, re-buttoning his coat.

January 4, 2017

Across the Great Divide – Chapter Sixty-Four

[image error]‘CAN WE DEPEND on you Charlie?’ Nell asked the crossing-sweep as they squatted together in the warmth of Myers’ brick kilns in Southwark. He often slept there of a evening, so long as he was well clear before the men rekindled the ovens at seven o’clock, which gave him two hours extra sleep on a winter’s morning. Any later and they’d bake him alive, he said, and meant it.

‘Mister Sharp said I’d help, did he?’ he asked, sucking on the orange Nell had brought him and pocketing the bread as if it were gold.

‘Not in your official capacity as sweep,’ said Robert, his legs aching from his cramped position. ‘In fact Mister Sharp denies all knowledge of this arrangement. He says you’ll understand – no?’

The dirty-faced boy sucked his orange some more, his shoulders hunched, his neck tucked into his meagre coat like some wind-blown bird. And how the wind whistled among those kilns; from the north for sure, frozen up there, snow-bound, said all the reports. ‘I ain’t denying I owes him a favour or two, what with all he’s done for me over the years.’

‘He says there’s no one but you could do this job,’ Nell encouraged him.

‘No one else small enough I expect,’ said Charlie resignedly. ‘He knows I’m such a little boy for my age, not likely to grow much. It’s tonight yer say?’

‘Yes Charlie, we can’t afford to wait.’ They’d had it from the landlord at the Hope Tavern that the house was not empty as the JP had said; a token presence had been left behind by His Lordship but no better chance would be had. The side entrance to the property had a broken fanlight small enough for a boy to crawl through and unlock the door from the other side. Broken by tradesmen delivering furniture, it wouldn’t be left broken for long.

‘Don’t your worry yourself, Miss,’ said Charlie, rubbing his cold hands. ‘I’ll get you inside all right.’

‘Good boy,’ she said, and gave him another orange.

It was agreed that they’d rendezvous at two in the morning, which left enough time to hire a coach and plan their next step. Bad weather or not, they were determined to go north as soon as rescue was effected.

Charlie stood shivering, as if he’d never stopped, when they arrived at the appointed hour. There was no moon, and no one abroad in the cold dark square, not even the bell man who told the hours. They slipped through the gate and made their way cautiously to the front of the house.

‘Will you get through there Charlie?’ Joe asked, pointing at the fanlight above the door. ‘It looks more cracked than broken.’

‘We can’t widen it or we’ll make too much noise,’ Nell said, disappointed by its narrowness.

‘I can make it I think,’ said Charlie, straining to look. ‘I’m like a slug when I get started, yer’ll not believe how I shrink and flatten myself. It’s a trick I’ve learned over the years.’ Nell was tempted to ask how old he was – eight, fourteen, twenty – all three were possible. ‘Clasp yer hands together,’ he said to Joe, ‘and give me a lift.’

Soon Charlie was clambering silently up the tall door like a ragged bat. At the height of the fanlight he anchored himself one-handed on the slim sill, hooked up his short thin legs and slid in, top half first, a human tortoise now, entering its shell in reverse. A deft swinging of the rest of him and he’d disappeared with hardly a noise, not even a squeak of glass as he dropped silently on the other side. The drawing of the bolts was noisier but he managed the task in two or three short bursts, pausing to check that the house stayed quiet. Presently the door edged open and his foxy features greeted them through the vacuous gloom.

They entered a small vestibule, not yet altered to His Lordship’s tastes in the fashionable Adams style. It led into the main hall, whose black-and-white tiles were the same as at Belle Isle, though floor-space was not so generous. Of smaller size too was a bronze statue of Mars, the god of war, which seemed apt – it was a war of sorts they were fighting, and Nell hoped the old god was on their side.

Her feet creaked on the polished floor and she walked on tip-toe, urging the others to do the same. As they climbed the broad staircase with its gleaming roundels, she looked behind with a shrug that said, ‘Which room? – do we try them all?’ The shrugs returned said yes, what choice do we have? She wasn’t thinking straight, however, and it was Charlie who put her right: ‘If one be locked, Miss, chances are it’s the one we want.’

Delicately they tried them all and one for sure was locked, right at the end of the left-hand corridor. The room faced a painting in the classical style but rendered in strange, inexplicable perspective. It was, Nell realised, a topsy-turvy likeness of the house, the lines and curves intended to confuse. Her head was in enough turmoil and needed every marker it could get. They’d no keys to help either and little brute force. Question was, dare they use what they had and risk the noise?

‘We’ve no option,’ whispered Joe, ‘it’s shoulders to the door and hope it gives. Then we snatch her from the bed and run.’

‘Agreed?’ Nell asked Charlie, valuing his opinion as much as Joe’s, maybe more. But his mouth, whose teeth were white against the dirt on his face, was not smiling. He nodded, showing fear for the first time.

‘Will we hang if we’re caught, Miss?’

‘No, Lord Pemberton wouldn’t dare,’ she said to appease him. She didn’t like to add that they’d be killed by a blunderbuss before it came to any gallows.

They steadied themselves, ready for the heave. ‘After three,’ Nell said and began the count.

The door was heavy for a bedchamber and didn’t give at the first attempt; a second, a third, and a fourth thrust were needed before the lock rattled and they felt its mechanism give. One more and they had flung it open at last, the force taking them with it so they landed on their knees (Nell and Joe) or on their bellies (Charlie). The figure that seemed to flutter in the darkened room was in a bed low down near the floor. Its muffled cry was Olu’s.

‘No time to explain,’ Nell said, reaching for the hand that was warm and trembling. ‘We must go – now.’

There was no need to answer, the cold grip of her hand was enough. Out the door and back along the corridor, taking the stairs two at a time, so they flew rather than ran and found their feet by miracle. They needed one too, for the house was stirring above, and stirred more when Joe knocked over the bronze statue and set it spinning with enough clamour to make the echoes weep. They lost direction in the darkness and the door was nowhere to be seen. In Nell’s head yet was that swirling, drunken artwork and when she’d rubbed her eyes to clear them they saw what they’d dreaded – a loyal servant (they were always the worst) armed with pistols, descending the stairs.

‘Can you work your magic?’ she asked Olu, for they’d be taken for common thieves as she’d feared.

‘Painting, he loves the painting.’

‘What? – that thing upstairs?’ Nell half believed it was put there to make all the burglars dizzy.

‘No, that one,’ she cried, pointing to the full length portrait. ‘It shows a likeness of His Lordship, who is very vain.’

‘You think to come here like this in the dead of night?’ said the servant, a squat man with a face like raw meat. ‘I resent being woken from my sleep. I don’t get enough.’ His whispery hair looked aglow with anger and fatigue, sprouting at all angles like a house plant finished flowering for the year.

‘You not shoot,’ said Olu. ‘You not want to ruin that picture.’ They kept it behind them as they backed away, and the front door was right beside it. And though the servant followed with pistols pointing he was in a quandary what to do. He took aim and thought better of it, dashing the weapons together so violently in his anger it’s a wonder they didn’t discharge.

But they were out in the street now running three abreast. ‘Don’t look back,’ Nell said, spotting the lamps winking in the gloom where Robert waited with the coach and their belongings packed inside. The weather was against them, but so was time – fate too, if they didn’t look sharp. The coach that Robert had procured was not to be had long-term for neither love nor money. Its driver was strictly a London man whose vehicle was leased from an operator in The Strand. Never mind, Nell reasoned, hadn’t Joe journeyed south by the Leeds Fly, whose return departure from the Swan in Lads Lane was at ten that morning? It was the fastest machine known to man, though that might not be saying much.

December 13, 2016

Across the Great Divide – Chapter Sixty-Three

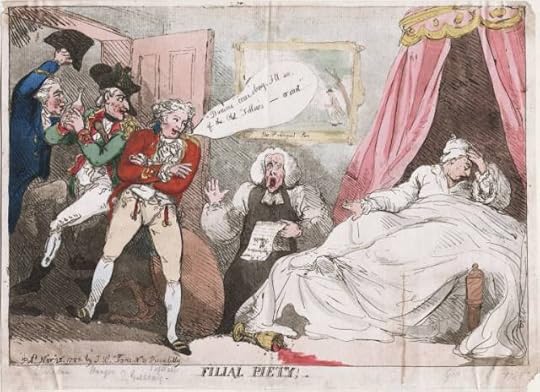

[image error]THE MAGISTRATE Mr Sharp recommended had died last week and his office lay vacant for now. Hobson’s choice ruled instead, which meant their case was put to the first who’d condescended to see them. Justice Leadbeater’s office in Chancery Lane was a large and echoing place, oak panelled and hung with sketches of anatomy. He was a great admirer of Mr Hunter, the JP said, and enjoyed watching vivisections from the public gallery at Guy’s. He also had a sense of humour few could understand but ignored at their peril.

He sat bewigged behind a large heavy desk piled high with paper and parchment. There was chaos among the order, he maintained, not the reverse as his clerk was fond of saying. His clerk was a pinch-faced man in his late twenties with a stoop so pronounced he looked to have no spine. The magistrate on the other hand was fatter than Toby Philpot, his face a bag of ruddy flesh punctured by brown sparkling eyes and a ravenous-looking mouth. One ear was larger than the other and gave him more trouble than it was worth; he was thinking of asking Mr Hunter to remove it in return for a good dinner of cow’s udder, roasted parsnips and a generous sprinkling of black pepper. All this before they’d got a word in edgeways about the help only he could give.

‘Let me get this straight as a dog’s hind leg,’ he said, fiddling with his troublesome ear, ‘you wish me to compel Lord Pemberton to set this slave girl free? You ask me to make him part with his property that for all you know he may have paid for out of his own pocket? You tell me you’re honourable people?’

‘Indeed, upon my soul,’ said Joe, ‘all three of us are precisely that. My father is Sir George Cooper …’

‘Oh yes, the Sugar King himself, a fine gentleman so I hear. A man of means and mode. Upon my soul, I do declare. The two men are friends, are they not? Why not apply to your father and let him sort this out? Gent to gent, so to speak.’

‘They are no longer friends, sir,’ said Joe, going on to tell of their fall out, how the bad-blood business of the marriage match had turned their relations sour. There was more too, which he didn’t enumerate – how Sir George’s present plight was unlikely to win him any battles. But the JP had a point: Olu was still his property in law; he had a right to claim her – at law – but that would take time, a long time, if what they knew of the law was correct. Someone in the meantime must secure the status quo; ensure Olu was safe pending official hearing.

‘No longer friends,’ mused the Justice, eyeing them as they stood before him in a line. ‘When great men are no longer friends some would say the wind is in the wrong direction. Is the wind in the wrong direction?’

‘It blows from the north, sir,’ said Robert in all innocence. ‘It blows cold and it brings snow. They say in the country the roads are impassable.’

‘Your father lives in the north, does he not Miss Cooper?’ said the Justice, feeding his small mouth with shelled almonds. ‘Is this slave an issue between them?’ he asked. ‘He holds her to spite him perhaps? If so, I wonder if it might not come to law.’

‘It may come to that in time,’ said Joe, ‘but time we don’t have.’

‘Yes, I see your point. All the same, pity it’s Lord Pemberton,’ said Leadbeater, crunching harder, ‘though His Lordship is a man who likes a joke. I also like a joke, which makes me a jocular magistrate – a contradiction in terms you might say. But what of it? What would life be like without jokes?’

‘What indeed, sir,’ Nell answered cagily. She knew all about Lord Pemberton’s jokes, and had more cause than most to dislike them. She recalled what he’d said about making Olu his own. Had she taken in jest what she ought to have taken gravely?

‘What would you say if I shared some jokes with you now? What if I said my propensity to help was in proportion to your degree of genuine laughter?’

‘I’d say that was most unusual, sir – but fair,’ said Joe, playing the game as well as he could.

‘Is that the consensus among you?’ They told him it was. ‘Then you won’t mind if I invite my clerk to make up the numbers? His laughter is loud, and when added to yours will make quite a clamour. One to annoy those miserable attorneys in the office next door. And if the weather is bad, what better way to combat it than with good old fashioned fun? Now, what shall I begin with? Do you know, I’ve come over all serious of a sudden.’ He was holding the small bell which he used to summon his clerk. ‘I feel sad, tearful, not at all jolly.’ He threw in another nut to see if that might help. He crunched it quickly and swallowed with an audible gulp. ‘Dear, dear, the wind is definitely from the north today, as it was yesterday and will be tomorrow, the weathercocks would say if they could speak. And if they could do so and predict the weather, perhaps they could predict other things – such as when this war with the Americans will end. It’s a dirty war and it will end like all dirty wars with the signing of a Peace of Shit.’ This was their cue to laugh, so they laughed and he rang his bell with instant result. ‘Ah, Magill! come and join us, good to see you’ve climbed down from your stool. I got him the highest one I could find, higher than in any office in the whole of London, and he being so small, it’s quite a spectacle to see him perched up there, perking at his books, looking every inch like a victim of Vlad the Impaler. Interesting background, Mister Magill’s,’ he said, staring at Nell significantly. ‘He looks all white but his father was black. How do you make that out?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘Then think about it. You should, but I can’t think why – can you? I don’t want you to answer now, I want you to look at Mister Magill. He hates me deep down but on the surface he’s oh so tender. I wonder what that makes him? Affectionhate?’

It was another joke, and they all laughed, Mr Magill the heartiest. ‘Good, not bad at all,’ said the Justice, applauding their efforts. ‘You make me feel like the clown I so much want to be.’

‘Your are a clown Mister Leadbeater,’ said his clerk fawningly.

‘But am I crude enough?’ the other asked with a hopeful look. ‘True humour is always crude. We are all men here but one. Only the women can judge true crudeness. I like them but I don’t lick them. I wish I did because I’d lick them well. As for me, I’ve never been well licked by women or men. Or dogs either for that matter.’ His clerk was laughing dutifully, so they laughed again too.

‘But we mustn’t forget why these good people are here,’ said the magistrate, holding up his hand peremptorily. ‘This fall-out as you term it, between your father and his Lordship. No chance of a make-up I suppose? A Lord’s bowels move in mysterious ways. What if Sir George pissed in a goblet and took it up to him in bed? What if he said, handing it over, here you are, my old friend, I’ve brought you a piss offering?’

Better to be on the safe side, Nell led the laughter a fourth time, which almost matched the clerk’s. This time the JP laughed too, outdoing them all and wiping his eyes with his pocket handkerchief. ‘Well that felt good I must say, it’s warmed my cockles, wherever they are. Probably down Billingsgate – go and fetch them Magill and be quick about it! You can get my goat while you’re at it, you’ll find that being slaughtered at Smithfield. And fetch me some liver while you’re there, it reminds me of what I rarely get – a woman’s – guess the word and you’ll have your writ.’

‘Quim,’ Nell said, and he grinned with pleasure.

‘Quim, fanny – a cunt by any other name is a cunt, as the great bard himself might have said if he’d had my sense of humour.’ Nell had lost hers long ago and he knew he’d gone too far. ‘But you’ll have your writ, I say, even though it rhymes with …’

‘Shit,’ said Robert, and while the clerk scurried out laughing, the JP smiled and said they were home and dry.

‘All right, you’ve passed my little test. Take this,’ he said, scratching a note with his quill, ‘and present it to his Lordship.’ He folded the paper twice, melted the bright red wax with the candle and sealed it neatly in the centre. ‘It’s serious in tone, no hint of joking, and it says what you want it to say: stand and deliver, sit down and surrender, swing from the chandeliers if you have to, but let her go. Mustn’t waste time beating about the bush, not when there’s a bird to be found in it – a black bird by the name of Olu. You get the drift. And he’ll get my drift likewise because he knows me – no hard feelings, I’ll tell him later over brandy and nuts.’

‘What if he refuses?’ asked Joe.

‘He won’t. He can’t. Not even great men are above the law. Now if you’ll excuse me, you’ve had quite enough of my time already. I’m getting too tender-hearted in my old age. On the other hand…’ – and here he broke wind and sighed with relief – ‘… perhaps I’m tender-farted. And as the gaoler said as he farted on the prisoner’s food – the condemned man ate a farty breakfast.’

‘Come on,’ said Joe, ‘I’ve had enough of this.’

‘Well that’s gratitude I must say,’ said the Justice as they turned to leave. ‘Wait, wait! Where are you going?’

‘To Lord Pemberton’s,’ said Joe, flapping the writ in the air.

‘No good, not worth the paper it’s written on,’ said the Justice, his bag face shuddering as he shook his head. ‘Not even good enough for wiping a man’s arse. Certainly not my arse. I prefer parchment myself, it gets the thick off like nothing else – now that’s wiped the smile off your face. He’ll not be there to receive it,’ he said, secretly relieved they were sure. ‘You see the house is all shut up and empty – apart from your girl of course, if that’s where she is.’

‘But …’

‘No buts, there’s too many in English law and I don’t mean butts for jokes. I mean rebutters, surrebutters – just ask next door, they make a living out of them. Messrs and Cornwell and Dance, Attorneys-at-Law.’

‘That name sounds familiar,’ Nell said, turning it over in her mind.

The fat man rolled his eyes, and his cheeks and neck rolled with them. ‘All names do to somebody. Stands to reason I expect.’

‘Mister Vine, my father’s attorney – Cornwell and Dance act as his London agents.’

‘Well such as he, a country attorney, will have no need to set foot in the capital, not with the likes of them to see to his affairs. Slippery characters, ardent pettifoggers and more besides. I can’t prove anything of course, they’re a clever pair, don’t commit much to paper, certainly not parchment,’ he said, shuffling uncomfortably on his seat. ‘They have friends in high places and there’s none to speak out against them. To lay an information at their door is to lay one at the Devil’s himself. Which brings us back to Lord Pemberton – you know it all seems to me like one big family.’

‘Cornwell and Dance are his Lordship’s attorneys too?’ Nell had guessed accurately.

‘When he’s in London yes.’

‘And when he’s in Yorkshire?’

‘Ah, sis,’ said Joe, ‘I was meaning to tell you about that but it didn’t seem important. There’s been a change by all accounts. Lord Pemberton has swapped his man.’

‘Vine!’ she declared as the fog (or some of it) began to lift.

‘What’s going on here?’ asked a frustrated Joe. ‘Why does Pemberton want Olu and why is Mister Vine involved? There’s more to this than meets the eye.’

‘You can’t take on the whole world,’ said Mr Leadbeater, more serious now.

‘No, but we can go home and take on Vine,’ Nell answered. ‘Where there’s a snake afoot only one solution presents itself – you must cut off the reptile’s head.’

At the mention of violence, Joe looked suddenly pale. ‘You think the three of us can handle this alone?’

‘Four of us,’ Nell replied abruptly, ‘four of us will handle it, and the fourth will feel like forty. I am taking Olu with us.’

‘You’ll never take her and stay within the law,’ said Mr Leadbeater. ‘My hands are tied I’m afraid,’ for which they read secretly pleased. ‘His Lordship has every law in the land on his side. And she’s an unclaimed runaway, his property in all but name. No court would ever contest his claiming her as a windfall. And yes, while there’s the Mansfield Judgement to stop him shipping her out against her will, he’ll have her bound as servant and beat the law that way. Legally, my dear, you don’t stand a chance.’

Legally he was right, but Nell wasn’t thinking legally: her aim was to steal Olu from under his Lordship’s nose.

My new novel, Pride Before a Fall Through Time, was published 30 November 2016. tinyurl.com/gtd8jc6

December 6, 2016

Across the Great Divide – Chapter Sixty-Two

WHAT SHE HADN’T counted on was their manner of doing business. The darkness helped, a cloying fog more grey than dark, and dismal as death. They took him on the threshold of his master’s door, five or six, Nell couldn’t say, only that their leader was vengeful, at full strength of power and gall. She followed them across the street into a small clearing overhung with leafless plane trees and broad beech that reminded her of home. The fog, the dark, the tangled thicket of branches heavy with snow gave perfect cover for what they had in mind, and for what she’d delivered him to. No quarter asked and none given, as the military men said, as Colonel Jenkins had shouted in the heat of many a battle. They held him pressed against the ribbed bark of the wide-girthed trunk; they stripped him to the waist in the cold and began to beat his upper body with the implements they’d brought for the purpose. They beat him for several minutes, his mouth gagged, before they put their single question: ‘Where is she? You know who.’

WHAT SHE HADN’T counted on was their manner of doing business. The darkness helped, a cloying fog more grey than dark, and dismal as death. They took him on the threshold of his master’s door, five or six, Nell couldn’t say, only that their leader was vengeful, at full strength of power and gall. She followed them across the street into a small clearing overhung with leafless plane trees and broad beech that reminded her of home. The fog, the dark, the tangled thicket of branches heavy with snow gave perfect cover for what they had in mind, and for what she’d delivered him to. No quarter asked and none given, as the military men said, as Colonel Jenkins had shouted in the heat of many a battle. They held him pressed against the ribbed bark of the wide-girthed trunk; they stripped him to the waist in the cold and began to beat his upper body with the implements they’d brought for the purpose. They beat him for several minutes, his mouth gagged, before they put their single question: ‘Where is she? You know who.’

To Hell with courage! To Hell with loyalty! Nell thought, when she saw it hadn’t worked. He was standing his ground on his trembling legs. He wouldn’t yet, on account of his master, betray the means to please. This was perversity indeed, and it earned him no rewards. What now? she wondered, as out came a hammer and nails from the leader’s coat.

‘Hold his hands flat,’ he instructed.

Crucified dogs came to mind as Nell craned her neck towards Joe loitering across the road, patting himself against the bitter cold. Robert was beside him blowing on his hands – hands that were pained by frost, and how much more they’d suffer if nails and hammer were applied! ‘Is this just?’ was the question on her lips that wouldn’t quite form. Why? – why did she say nothing?

It wasn’t just Nell who stayed mute. There was little talk, scarcely any, the whole spectacle played in dumbshow. Yet in some ways it seemed so ordinary, beautiful too in the fog and snow and chilling air. Still she watched; for posterity’s sake she didn’t want to miss a thing. She wanted to remember, fix every detail forever though they’d plague her for life. She’d remember the snow on the tree bark, upon the last stray leaves of autumn, upon the stiff grass where shoes crunched and buckles shone dully. His body writhing stiffly with the first nail, a suppressed scream virtually silent. The blood oozing thick and slowly like oil, not red but black in that dark light. The faces of his torturers gathered like revellers round a festival tree that wanted only a brazier for roasting chestnuts. And then carefully, when the first long nail was hammered in half its length, the leader repeated his question in a soft almost tender voice: ‘Where is she? You know who.’

‘You go to fucking hell,’ his victim cried.

Undeterred the other, who was now his executioner for sure, extracted a second nail from his pocket and hammered it in without pause all the way to the hilt. ‘Look what you bring me to?’ he said, his face up close. ‘You make this harder than it needs be.’

Nell stayed for the rest out of duty, out of curiosity and, because she’d seen murder before as committed by loved ones – a brother who had murdered a dog, and a father a slave – out of resignation. Still she loved them, her filial killers; such things were never simple, and in some ways there was neither right nor wrong, only forgiveness and a means to an end. This man’s death was exactly that; an end that might be changed if he’d tell what they wanted to know. His destiny was in his hands – literally, for he was nailed to a tree like Jesus.

They were about to start on his feet, were removing his boots, arguing whether two feet crossed or both feet separate was preferable. They might have been talking of a plant that needed training to a trellis. And yet for victim and killers alike there could be no going back. He would have to be finished now, for all their sakes.