Linda Holeman's Blog

April 21, 2020

April 2020

Movies and Memories…

What a strange moment to be alive: a time in history none of us could have envisioned. It’s really a time for self-reflection, being alone or isolated with family through this pandemic. There are only so many things one can do while inside for 23 out of every 24 hours – those of us who can get out for a physically-distanced walk are the lucky ones. Like some of you, I’ve been cooking and baking more (and naturally eating more), and I’ve edited and organized photos I’ve been meaning to get to for a few years. I’ve done the requisite cleaning of closets, and I’ve sat in front of my computer for hours on end, trying to write (although I’m beginning to suspect my muse is in quarantine), but also watching too many time-wasting videos on YouTube, including how to shear an alpaca and the moments on Britain’s Got Talent that made Simon Cowell cry.

But being able read for hours as I work through an immense stack of waiting books without guilt about what I should be doing instead brings me great joy. And, of course, there’s the television. I try to stay away from the lure of daytime television, I promise, but there are so many new series, some intriguing and eye-opening, like Unorthodox; others to make us laugh – hello there, What We Do in the Shadows, and some downright bizarre – yes, I’m talking to you, Tiger King. And there are movies: some great new ones, but also old ones, which are sometimes hard to find, but worth the search.

A few weeks ago, I decided to take a look at some old-timey movies I remembered having an effect on me when I was a child. After a while, I started to take note of the pattern of movies that called to me: they were all movies that I had watched with my grandmother. And there was more: they were movies that had shaped me into a traveler, instilling in me the clichéd word wanderlust.

My paternal grandmother Luba was probably clinically depressed much of her life, although when I was a child, Grandma was just called sad. Her life was marked by major tragedies, starting, when she was five or six, with the death of her mother. The trauma continued when, a few years later, ten-year old Luba watched helplessly as her younger brother was snatched up from their Russian village by Cossacks galloping through in a cloud of dust. The little boy was never seen again – and this event became the genesis for my novel, The Lost Souls of Angelkov.

When she was only 49, my grandmother was widowed; in photographs from that time she looks at least twenty years older. She never gave up her widow’s grief, moving in with our family because she found it too difficult to live alone.

To combat her loneliness, she looked to her five grandchildren for distraction. Each of us played a different role in her life. And I like to think I was the lucky one; she called on me to watch movies with her. Even though I was far too young for most of them, I became Grandma’s companion on journeys that took her away from her own narrow world and negative thoughts.

I either accompanied my grandmother to our local movie theatre or watched movies on our black-and-white television on snowy, cold Winnipeg evenings, snuggled beside her on the couch. Coming from my crowded, working-class household of five children with busy, distracted parents, she was the only adult in my life who had the time to give me individual attention – which I lapped up with what was probably pathetic gratitude.

Grandma always chose movies that took place in faraway, unfamiliar places, with plots focused on impending doom or danger – definitely no cheery romances or comedies or musicals. Was this because the troubled aspects of life were familiar to her? I think about this in my own choices as a novelist: I’m much more attracted to the dark side. Is this interest something I inherited – without the internal, constant grief – from my grandmother?

Only as an adult do I realize how enlightening those movies were, in terms of introducing me – a child firmly rooted in a smallish, geographically isolated city in the middle of Canada – to other cultures and to historic events. I remember watching The Good Earth, full of heartache in early twentieth century China, and Genghis Khan, the life and conquests of the 13th century Mongol emperor that both frightened and fascinated me. Lost Horizons focused on a group of survivors from a plane crash stumbling into the mysterious and other-worldly village, Shangri-La, hidden in a valley in the Himalayas. There was Lawrence of Arabia, with the romanticism of the desert and the handsome hero, and The African Queen, with the mismatched couple Allnut and Rose making their way through the dangerous waters of the Ulanga River in exotic Tanganyika – now Tanzania – during WWI.

As I started my own journeys into the world, I followed many of those childhood memories, although I wasn’t immediately aware where my desire to explore certain parts of the world came from. But there were times, as I set foot in a new country, that I may have heard a whisper from my long-deceased grandmother, urging me to remember where I had first encountered that country: with her.

Visiting China, I thought of The Good Earth and poor, beleaguered O-Lan as I witnessed village life in the countryside as well as the chaos of the cities.

Experiencing the barren lands of outer Mongolia by train and vehicle and finally on horseback, of course I thought of Genghis Khan and his horde of Mongol followers – even though I knew by then that the film had actually been shot, all those decades ago, in the country formerly known as Yugoslavia.

Then there was the striking Sir Laurence Olivier as Lawrence of Arabia, thundering across the desert of Jordan. Was it odd that a few years ago I found myself walking across the Israel-Jordan border and climbing into a jeep that took me to Wadi Rum, where scenes from the movie were filmed? As I hiked sand cliffs and dunes, I envisioned those scenes of Lawrence racing into battle.

On another long journey, as I flew over the Himalayas on my way from Nepal to Bhutan, I thought about Lost Horizons, looking out the window of that small, shaking plane into the valleys below. To distract myself from the rather uneasy flight, I tried to imagine which could be that mysterious Blue Moon Valley known, as Shangri-La.

While I travelled through Tanzania, I watched hippos basking under the sun in the Ulanga River, envisioning The African Queen with Hepburn and Bogey portraying sweaty contrarians working together to fight for survival from both nature and human dangers.

Those are only a handful of the many movies that shaped part of my future by fueling an intense desire to explore the furthest reaches of the globe. I know there will be no more carefree travel for some time; maybe the whole idea of travel will be changed. As I’ve said, it’s a time of reflection for all of us, and remembering my grandmother and those movie experiences through these long evenings of the pandemic gives me something to focus on as the world struggles to heal itself. Stay safe, everyone.

July 21, 2019

July 2019

Where We Find Books – or Where They Find Us Part Four…

Oh Colombia, you captured my heart. A lot of people believe that Colombia is still the cartel-controlled, dangerous country of the 80s and 90s. It takes a long time for people to let go of the memories fueled by images and journalism, influenced even today by the Netflix series Narcos. But after the death of Escobar in 1993, the country began a renaissance which continues steadily, making Colombia a welcoming and friendly place. I’ve heard other travelers call it Latin America’s coolest secret.

I loved visiting the island of San Andres, and the cities of Bogota and Medellin, each place with its own history and interesting stories. But it was in Cartagena, the sixteenth century coastal city dangling into the Caribbean Sea, that I immersed myself in learning about the man who had written books I’d fallen in love with when I was much younger. Gabriel García Márquez, affectionately known as Gabo, lived only briefly in Cartagena, where he started his career in journalism. But when his family moved to Cartagena he became a frequent visitor, eventually building a home there.

I stayed in a hotel in Getsemani, a vaguely seedy, working-class but hip and utterly charming neighbourhood just outside the old walled city. Getsemani’s stone walls are covered in vivid, creative graffiti, a tribute to a city waking from a long sleep as it recovers the charm and vitality that García Márquez’s novels describe in such deep and resonating glory.

García Márques once stated: “All of my books have loose threads of Cartagena in them. And, with time, when I have to call up memories, I always bring back an incident from Cartagena, a place in Cartagena, a character in Cartagena.” He added, “I would say that I completed my education as a writer in Cartagena.”

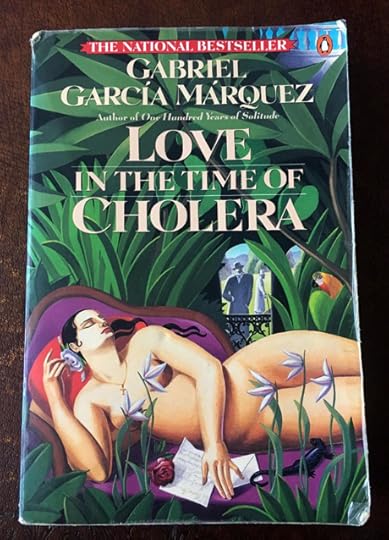

Cartagena was the setting of García Márques’ Love in the Time of Cholera, regarded by some as one of the twentieth century’s great love stories in literature. He’s admitted that he based this fictional tale on the courtship of his own parents.

My own second-hand edition, bought almost thirty years ago. There may be a few tear-stained pages…just saying.

Although I own a number of Gabo’s works, I decided to look for more around Cartagena’s Old City. And I was always rewarded, not just by finding copies of his works in Spanish and English, but also by the places I found them.

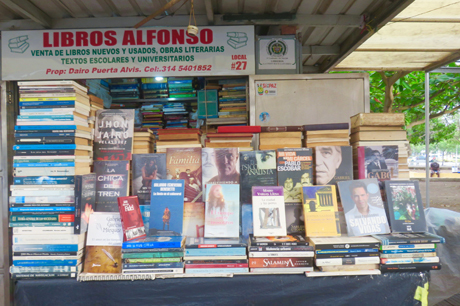

By this photo it appears that any place to sell books will do. This bookseller had set up his “moveable feast” (although of books, not food) just inside the Old City gates.

Wandering the tangle of narrow, bustling streets, made glorious with colourful, flower-filled balconies on old colonial houses, I stumbled upon Abaco: Libros y Café. Although small, books are stacked from the beautiful stone floors right to the rafters. It’s a welcome respite from the Colombian heat, and the hushed atmosphere immediately brings a sense of calm after the slightly chaotic commotion on the streets outside.

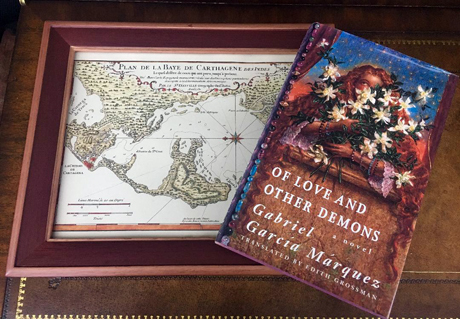

As well as recently published, second-hand, and even a few rare books, there is also a selection of reproductions of maps (don’t get me started on maps; they are a secondary love after books). It was difficult to leave this place empty-handed. And…I didn’t.

García Márquez was inspired to write this 1995 novel, Of Love and Other Demons, after his year in Cartagena in the late 1940’s. As that young journalist, he was sent to investigate the grisly discovery of the skeleton of a young girl with seventy feet (!!!) of copper hair, buried under the floor of a 17th century former convent. In what had become his trademark, García Márquez combined myth and reality in this novel. He’s been said to “tell the truth through inventions and make-believe”: his own style of magic realism, in which he treats the extraordinary as completely natural.

As I walked back to Getsemeni, right across the street from the Old City gates I discovered a full block of pop-up stalls of books, reminiscent of those that line the Seine in Paris.

I found both novels by Gabo and non-fiction about him in this stall.

It felt lovely to walk some of the paths García Márquez walked as he worked out his themes and mysteries, whether under the shade of almond trees by day or in the warm, breezy nights with the scent of roasting meat and spices from street vendors. And by the end of my time in Cartagena, I was certain in my conviction that his work reflected his belief in the enduring power of love.

September 10, 2018

September 2018

Where We Find Books, or Where They Find Us

Part Three…

I had the wonderful opportunity to visit the West Indies in the spring. I particularly loved the island country of St. Vincent, with its thirty-two islands and cays, known as the Grenadines. Some of the islands are inhabited, and others are a tangle of jungle and dramatic mountains and deserted beaches. They have mystical-sounding names like Mustique and Isle À Quartre and All Awash, names that bring adventure to mind.

And, of course, while travelling, I am always looking for interesting bookstores in unexpected places. The most curious I found on this journey was on the island of Bequia (pronounced BECK-way) in Port Elizabeth, its tiny harbour town.

My daughter Brenna and I took the hour-long morning ferry to Bequia from St. Vincent, arriving in time for milky coffee before setting out to explore by foot what we could of the island, which, from the moment we stepped off the ferry, was atmospheric and welcoming. The whole island has less than 5,000 inhabitants, and this sleepy little port town had the charm of a place slightly lost in time, in the best possible way. Bequia means “Island of the Clouds” in ancient Arawak, the language of the indigenous peoples of South America and of the Caribbean, and for us the island lived up to its name.

All along Belmont Way, the only main street in Port Elizabeth, were small tables of local wares: rich, colourful displays of Caribbean artwork, handmade jewelry, brightly colored clothing, scrimshaw, and handcrafted wooden boats. The majority of businesses on Bequia are locally owned and managed, and, because of its small size, the people living here are connected through their community pride. The street contained small, humble hotels and guesthouses with endearing names like The Gingerbread Hotel, The Frangipani, and Rambler’s Rest, as well as little shops selling all manner of products. And there was a beautifully painted little bookshop, aptly named Bequia Bookstore. I was disappointed to find it closed.

Thinking I wouldn’t get to see what the bookstore had to offer, I stopped to look at a table of children’s books on the street, and had the pleasure of meeting a woman who said she was the poet laureate of the island, showing me a computer-generated diploma with her name written onto it. Was she actually the poet laureate? Does the island HAVE a poet laureate? I don’t know, but she was personable and friendly as she read me a rhyming book on recycling on Bequia she’d self-published. I was a captive audience of one as I stood, anxiously moving from foot to foot, watching my daughter disappear on her own explorations. Still, it was a cool experience any way I look at it.

While we would have loved to visit the strange-sounding Moonhole Beach, it could only be reached by boat, so we decided to take a little footpath to Princess Margaret Beach, one of the island’s two more accessible beaches. Part of the path along rocky scree and jungle was washed out due to a recent storm, and we had to do some mountain-goat-like leaps and crafty maneuvers to get to this mainly deserted, gorgeous white sand beach. There were only a couple of locals there, happy to pour us plastic cups of rum punch from huge jugs they had brought down to sell on the beach. There were also a few friendly dogs who followed us to a shady spot under some tall palm trees and then slept peacefully beside us, happily jumping up to accompany us when we walked along the surf, and sitting patiently at the edge of the sea as we took a quick swim to cool off. The white sand beach was tranquil, although with a sense of wildness, the jungle coming right down to the sand.

After a few hours of sun and sand and sea (and yes, rum punches), we said good-bye to the locals and dogs and headed back to Port Elizabeth for our afternoon ferry back to St. Vincent. I was excited to see Bequai Bookstore was now open, a young girl I assumed to work there reading on a chair on the porch.

I loved what I found inside. There was West Indian, North American, and European fiction, as well as lots of informative books on the flora, fauna, and wildlife of the islands. There were instructive manuals on sailing and yachting. I even found some old classics that looked as if they’d been on the shelves since their publication. There were no other customers, the girl running the store still reading outside, and I browsed to my heart’s content. And in a back room, along with faded Christmas decorations, were open cabinets of hundreds of faded scrolled charts and survey maps for sailing.

I wondered how many people visited the bookstore. I wondered how many survey maps they sold. I bought one, then carried it, rolled up in my carry-on, through another few islands and eventually all the way home to Canada. I have no use of a map of this sort, but I leave it on a shelf in my office, and every time that rolled map catches my eye I’m transported back to the Island in the Clouds, and the beautiful, dusty little Bequia Bookstore.

May 28, 2018

May 2018

Where We Find Books – or Where They Find Us

Part Two…

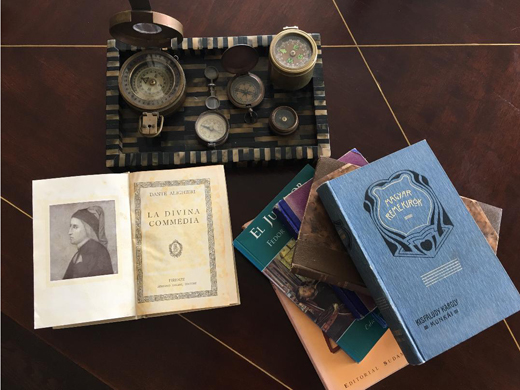

Over my lifetime of travel, I’ve often tried to find a book written by an author of the country I’m exploring. Naturally they’re written in the language of the country, and I can’t read them, but I love looking at them in my “foreign edition” bookshelves. I will admit that I’m pretty crazy about organizing and reorganizing my bookshelves in the way of most bibliophiles, and also will tell you that I get a definite rush by simply holding my 1925 Edizione Florentia copy of Dante’s La Divina Comedia.

Last year, as my daughter Zalie and I left Canada for a month-long adventure of some of the Balkans – Croatia, Macedonia and Albania – as well as Georgia and Armenia, I imagined I would uncover something exciting for my collection. We flew in from Tbilisi, Georgia, landing in Skopje on a steamy August morning, as the sun was starting to make an appearance over the landlocked Balkan nation of mountains, lakes, and ancient towns in the country known internationally as FYROM, the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia. Before the breakup of Yugoslavia, I had travelled through all the narrow roads of the country, and was curious to revisit it.

We first explored the Old Bazaar, connected to the newer city of Skopje by the 15th century Stone Bridge over the Varder River. We loved the small, ancient place, with its 1492 Ottoman-era Mustafa Pasha Mosque as a focal point on a plateau above the Old Bazaar’s tiny winding streets. We got lost and found and lost again in those atmospheric cobbled lanes, standing still to listen to the overlapping, echoing calls to prayer from the many minarets.

Back in modern Skopje, we found city squares of smooth, shiny marble teeming with elaborate neo-classical structures and towering columns with ornate details. There are marble and bronze statues of the known and unknown, from Mother Theresa (who was born in Skopje in 1910 and lived there until, at eighteen years old, she left for her life vocation in India) to a shoe-shine man to a bull reminiscent of New York City fame. The piece de resistance is the massive statue of Alexander the Great, currently the largest in the world, although Greece claims they will soon outdo it. There are also abstract human forms, artistic and full of life – and some just a little bit creepy – near the new theatre. The city has undergone a massive reconstruction, and most of these statues are a result of Project Skopje 2014. Along with the over-abundance of statues, there are fountains, massive, multi-tiered fountains, with lions and horses and mothers and babies. The physical scope of the city was almost overwhelming, in spite of the lack of people. Perhaps it was too hot, or perhaps it was holiday time, but the city streets had an air of emptiness.

Alexander the Great – AND fountain!

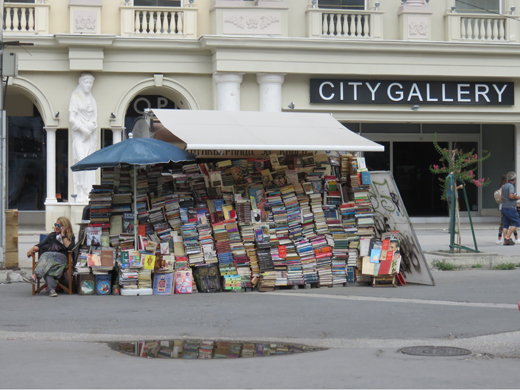

We finally stopped at a small café to cool off with glasses of frosty Macedonian beer, with its undecipherable name. Standard Macedonian, the official language of the Republic, was implemented in 1945, and its alphabet is an adaption of the Cyrillic script, unreadable to our English alphabet sensibilities. I’d had no luck in coming across a bookstore on either side of Stone Bridge, but as we sat sipping our beer, looking across the square, there they were: books. Hundreds and hundreds of books, but not in a bookstore. These volumes were simply under an awning on the street. They were stacked and piled, leaning and threatening to tumble. During the hour we sat at the café, nobody stopped or even glanced at them. Clearly the stacks of books were as much of the local landscape as the statues and the fountains, but they were more exciting to me than so much shining marble and rushing water.

Zalie and Macedonian beer

We went over to it, and I kept saying Slavko Janevski to the woman sitting beside the books. I had discovered that he’d written The Village Beyond the Seven Ash Trees in 1952, and it was the first novel to be published in the Macedonian language. But the woman just shook her head and shrugged, pushing another book into my hands. I finally bought it, although naturally, like the name of the beer, it was Cyrillic, and I couldn’t read the title of the book, or the author’s name.

But that was as much as I needed. I had bought a book written in Macedonian, and walked away from that small square in Skopje happy, even though I didn’t know what I had bought. And it still brings me pleasure to look at that unreadable novel in my shelf today. That’s kind of how it works when books find you.

July 2018

Where We Find Books – or Where They Find Us

Part Two…

Over my lifetime of travel, I’ve often tried to find a book written by an author of the country I’m exploring. Naturally they’re written in the language of the country, and I can’t read them, but I love looking at them in my “foreign edition” bookshelves. I will admit that I’m pretty crazy about organizing and reorganizing my bookshelves in the way of most bibliophiles, and also will tell you that I get a definite rush by simply holding my 1925 Edizione Florentia copy of Dante’s La Divina Comedia.

Last year, as my daughter Zalie and I left Canada for a month-long adventure of some of the Balkans – Croatia, Macedonia and Albania – as well as Georgia and Armenia, I imagined I would uncover something exciting for my collection. We flew in from Tbilisi, Georgia, landing in Skopje on a steamy August morning, as the sun was starting to make an appearance over the landlocked Balkan nation of mountains, lakes, and ancient towns in the country known internationally as FYROM, the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia. Before the breakup of Yugoslavia, I had travelled through all the narrow roads of the country, and was curious to revisit it.

We first explored the Old Bazaar, connected to the newer city of Skopje by the 15th century Stone Bridge over the Varder River. We loved the small, ancient place, with its 1492 Ottoman-era Mustafa Pasha Mosque as a focal point on a plateau above the Old Bazaar’s tiny winding streets. We got lost and found and lost again in those atmospheric cobbled lanes, standing still to listen to the overlapping, echoing calls to prayer from the many minarets.

Back in modern Skopje, we found city squares of smooth, shiny marble teeming with elaborate neo-classical structures and towering columns with ornate details. There are marble and bronze statues of the known and unknown, from Mother Theresa (who was born in Skopje in 1910 and lived there until, at eighteen years old, she left for her life vocation in India) to a shoe-shine man to a bull reminiscent of New York City fame. The piece de resistance is the massive statue of Alexander the Great, currently the largest in the world, although Greece claims they will soon outdo it. There are also abstract human forms, artistic and full of life – and some just a little bit creepy – near the new theatre. The city has undergone a massive reconstruction, and most of these statues are a result of Project Skopje 2014. Along with the over-abundance of statues, there are fountains, massive, multi-tiered fountains, with lions and horses and mothers and babies. The physical scope of the city was almost overwhelming, in spite of the lack of people. Perhaps it was too hot, or perhaps it was holiday time, but the city streets had an air of emptiness.

Alexander the Great – AND fountain!

We finally stopped at a small café to cool off with glasses of frosty Macedonian beer, with its undecipherable name. Standard Macedonian, the official language of the Republic, was implemented in 1945, and its alphabet is an adaption of the Cyrillic script, unreadable to our English alphabet sensibilities. I’d had no luck in coming across a bookstore on either side of Stone Bridge, but as we sat sipping our beer, looking across the square, there they were: books. Hundreds and hundreds of books, but not in a bookstore. These volumes were simply under an awning on the street. They were stacked and piled, leaning and threatening to tumble. During the hour we sat at the café, nobody stopped or even glanced at them. Clearly the stacks of books were as much of the local landscape as the statues and the fountains, but they were more exciting to me than so much shining marble and rushing water.

Zalie and Macedonian beer

We went over to it, and I kept saying Slavko Janevski to the woman sitting beside the books. I had discovered that he’d written The Village Beyond the Seven Ash Trees in 1952, and it was the first novel to be published in the Macedonian language. But the woman just shook her head and shrugged, pushing another book into my hands. I finally bought it, although naturally, like the name of the beer, it was Cyrillic, and I couldn’t read the title of the book, or the author’s name.

But that was as much as I needed. I had bought a book written in Macedonian, and walked away from that small square in Skopje happy, even though I didn’t know what I had bought. And it still brings me pleasure to look at that unreadable novel in my shelf today. That’s kind of how it works when books find you.

April 3, 2018

April 2018

Where We Find Books – or Where They Find Us

Part One…

Last summer I had the amazing opportunity to explore four of East Africa’s countries: Kenya, Rwanda, Uganda and Tanzania. I was with one of my daughters, Brenna, and, as usual when travelling together, we coordinated our reading material for our adventure. Our goal was to bring novels or non-fiction written by female authors of each country. This proved slightly difficult, necessitating research and ordering, at times, from out-of-print sellers, but we managed. Of course, you’re probably thinking, why didn’t you download your books onto an electronic device? Who carries eight to ten books when you’re packing light to go on safaris and treks throughout four countries? We did. Why? We did consider that power sources to charge devices might be iffy in remote areas. But it really wasn’t that. Brenna and I are writers. We want our physical books. We need to hold them, to turn down pages and scribble in margins and flip back and forth. Yes, any electronic reading device allows you to bookmark and highlight. I know. But humour me. You know it’s not the same.

We read while waiting in airports and during flights, and by our headlamps in camps after the sun went down and there were hyenas calling and howler monkeys leaping through the trees above and baboons slyly checking for any bits or bobs – a water bottle or hat perhaps – forgotten outside the tent (and never to be seen again).

Occasionally, some of the little guest houses in the small cities we moved through for a night here and there had a book exchange, and we left our own used books and found those left by other travelers. Halfway through our six weeks we worried about running out of books. And then…a library, tiny and unexpected, on an isolated island in the middle of a lake in Uganda.

We had travelled on foot through the very slow and slightly confusing border crossing from Rwanda into Uganda. Our Ugandan driver, Bosco, picked us up and drove us through miles and miles of beautiful terraced hillsides growing sweet potatoes and maize and cassava in his old and dusty 4X4. All we had on our itinerary – which we’d planned ourselves – for our first three days in Uganda was that we would be staying at Lake Boonyani, in a geodome crafted from local materials. It sounded perfect.

As the sun went down over the Ugandan countryside Bosco switched on his headlights and sped up, and we bounced around, expecting, at any turn, to come into a campsite near a lake. Instead, after maneuvering through a small town filled with bicycles loaded down with bananas, honking truck horns and flocks of goats creating natural traffic-calming zones, Bosco slowed the truck and carefully inched down a steep incline. I heard water. We got out and Bosco set our bags on the ground and left us in the dark, telling us he would meet us here in three days. Another man appeared and motioned us to follow. We ended up on a rickety dock that was a few pieces of wood barely holding together. And there was a tiny boat, a cut-out canoe of sorts, rocking on the gentle lift and fall of the lake. The boat driver carefully distributed the weight of our bags and after we had gingerly climbed in, he started the small motor and we headed out into complete darkness. There was no light on the boat, and no moon or stars, as there was a heavy cloud cover eventually bringing rain, making it even harder to see ahead of us – although we didn’t know what we were looking for. We did barely miss running into some night-fishermen throwing their nets into the black water, but the driver of our boat – and the fishermen – seemed to take it in stride as, amid shouts, we swerved sharply to avoid a collision. And then we saw a few tiny pinpoints of light; they looked oddly high in the darkness.

They were. The camp was at the top of an island hill. We pulled alongside a similar rough dock as the one we’d left on the mainland, and the driver flashed a torch a few times. Two young men came running down to the dock. Each picked up a bag and disappeared. The boat pulled away. Brenna and I climbed – and climbed and climbed – many, many winding wooden steps. The rain stopped, and the night clouds disappeared as we reached the top of the hill, and were shown to our geodome under the glorious blanket of stars the clouds had been hiding. By their soft glow we did our best to get ready for bed and climb under our mosquito netting to fall into our usual exhausted sleep after yet another long and exciting and challenging day.

In the morning, we awoke to brilliant sunshine and the most glorious view of Lake Boonyani through the open front of our geodome. The wooden deck this thatched, domed structure (it felt like being inside a three-sided beehive) rested on was the perfect place for us to read and write and dream.

That first morning we explored the island camp. And there it was, down one of the paths: a small, inconspicuous wooden building. Inside were tables and chairs and bookshelves holding all manner of well-used books in different languages to be borrowed during one’s stay on the island. I spent the rest of that first morning reveling in what I found.

For all the glory of our stay in Lake Boonyani, this tiny, gracious place was one of the highlights.

July 31, 2017

July 2017

Catching the Travel Bug…

I was never a big “joiner” in terms of clubs and groups, and that holds true today. I definitely have a spirit of community, and I love socializing with colleagues and friends, but signing up for something I MUST be attendance for every Tuesday at 7 pm for the next so many weeks or months has always filled me with dread.

But I couldn’t escape belonging to one club in high school: it was mandatory. Oh, the horror I faced, trying to pick something I could not only enjoy, but could be even okay at. Debating? Not on your life. Science? Um, that would be a big NO. Nothing to do with sports, thanks. But luck was on my side. That year saw the introduction of a new, previously unimagined club. Mr. S had done a lot of travelling before his teaching career, and, bless him, starting his first year at my high school, he was enthusiastic about bringing his knowledge of distant, intriguing worlds to any interested students in a small corner of Winnipeg. He started the Travelogue Club, and my name was first on the very short list. There were only ten or eleven of us like-minded souls in the club, and nothing was required but to sit and watch the slides he’d taken on his travels or reels of documentaries of life in other countries. He spoke of whirling dervishes in Turkey and the messy joy of taking part in La Tomatina in Spain. I learned that there really was a Timbuktu, and that the Tasmanian Devil was an actual animal and not just a cartoon character named Taz. There was no participation expected; all I had to do was watch and listen. And dream. At the end of each class Mr. S gave us a list of voluntary additional reading, both non-fiction and novels on the country we had just been subjected to. Perfect for me.

My parents were not travellers, nor did they appear to have any interest in leaving Winnipeg when I was younger. I watched as some of my friends went on family summer vacations, west to such romantic sounding places as Lake Louise and Banff, or east to the mystery of the Bay of Fundy, or all the way down to California to yes, you guessed it, Disneyland. I endlessly dreamed of adventures in new places, but it was impossible for me to envision my own parents taking us any further than fifty miles to a family get-together on a prairie farm, or, occasionally, a week hiatus to a rented cottage near one of Manitoba’s lakes.

Starting at sixteen, I did my share of hitch-hiking and driving in Canada and the US, but that wasn’t enough. I was obsessed with flying away from North America and touching down on basically any foreign land. Along with the sights and sounds Mr. S had installed in my head, my desire to travel was highly influenced by the music of the late 60s and early 70s: I wanted to board Crosby, Stills and Nash’s “Marrakesh Express”, I wanted to be taken to the heart of India as in John Lennon’s “India, India”, and I wanted to touch Cat Steven’s ‘strange and bewildering’ “Katmandu” (sic). My opportunity finally came when I was twenty-one. Because I had to count every penny very, very carefully, I found the cheapest flight I could: to Amsterdam on a one-way $99.00 student ticket. The only catch was it flew out of Buffalo, New York, and getting there from Winnipeg would cost way more than that flight to Europe. I heard about the friend of a friend who had been relocated to Toronto on a company move, but needed to get her car – and cat – there. She would pay for gas, food, and one night in a motel along the way (hello Wawa, Ontario). So I drove the car from Winnipeg to Toronto, accompanied by the endless cacophony of a car-sick, yowling Siamese. From Toronto, I caught a bus to Buffalo and then on to its little airport. The plane left just before midnight on the student “champagne” flight, so-called because of the small plastic glass of something fizzy we were handed at 7 am as the overnight flight started its descent. It was all thrilling to me, and I knew, as I felt the exhilaration of the liftoff and the continuing excitement that kept me wide-eyed as the plane hurtled eastward through the night sky, that I would definitely be doing this again. And again and again.

And I have. The best thing about travel is that it’s never done. There’s always somewhere new. To quote Susan Sontag, “I haven’t been everywhere, but it’s on my list.”

People regularly ask me: did you have a mentor, someone who encouraged you to write? My answer has always been no, apart from that one Grade Five teacher who saw something in my writing and entered it into a radio writing contest. But did I have a mentor for my love – and life – of travel? Yes. Mr. S, the architect of that first Travelogue Club. I’ve often thought of his influence, and I’m sorry he never knew how much he inspired me.

With my own “Magic Bus” on the road outside San Sebastian, Spain, 1973.

May 31, 2017

May 2017

The Scope!…

Next up with the third installment of “School Days Writing”: sounds like something old-timey from Laura Ingalls Wilder or Lucy Maude Montgomery. I give you my word I am not THAT old.

After the thwarted novel attempt I discussed in my last “here I am as a hopeful adolescent writer” post, I daily scribbled in my very private journals. But as far as being published goes, all I can boast of is writing for my high school newspaper, Scope. There are a number of novels and memoirs, as well as movies, with young people writing in their school newspaper about politics and equality and making the school (next up, the world!) a better place.

Hmmm. Not so in my case. If only I could boast that I had written witty, scathing op-eds about the national or even local political arena, environmental issues or world peace. Although in truth, nobody was writing that kind of thing in the few issues of Scope I kept (uncovered in the box I’ve previously mentioned). There was a lot of talk about sports, accounts of the upcoming musical, exchange students, the science club’s latest discovery, and the ever-present tittle-tattle on teachers and students alike. What’s that, you ask? What did I write, then?

Here you have it: I wrote the fashion column during my grade eleven year. I was highly flattered to be hired for that particular column, mainly because I made most of my clothes in high school, and trust me, when I look back at any photos from that era, they definitely looked homemade. I made them not because I loved sewing, but because it was the only way I could come even close to wearing what I wanted to wear. I couldn’t afford to buy the things I coveted in the shops, or in the fashion magazines I hungrily lingered over at the drugstore, but I could, on the old portable Singer in our basement, figure out how to make them. My mother didn’t know how to sew at all, and she claimed she didn’t know why we even had a sewing machine. I put it down to another mystery from that cluttered old basement. Lest I’m making myself sound like the poor little match girl…not quite. It was just the logistics of growing up in a fairly large, very working class family where there was no extra money for anything but the barest necessities, and I wanted more than that.

I did learn the essentials of sewing in mandatory junior high Home Ec classes: one half the year cooking, one half sewing (note: the boys took Shop, which included workworking and car maintenance – no feminism rearing its head back in Winnipeg circa 1960s). But I needed more than the basics of sewing a straight seam and creating darts and learning the meaning of cutting on the bias to make what I longed to wear. So I taught myself – I would have promised my first born for Google back then – the way I learned a lot of things when I was younger: out of sheer desperation and determination. And I understand now that desperation and determination can create passion, which is good for getting things done – like the desperate determination I need to approach my novel-in-progress today.

The first theme I came up with was “The Young Look”, and somehow felt I had the authority to state: To start off the new school year in a big way, keep in mind that the look this season is “young”. Wait. Wasn’t I sixteen years old, and writing for high school? Wasn’t everybody young?

It gets worse. So much worse. After talking about skirts that fall into something that isn’t quite A-line but certainly isn’t straight, either (?) I actually wrote this: But the shirt that looks like “his” – but not on you! has achieved that daring “come-hither” look that everyone desires. In bold, yet shy (what does that mean?) printed or solid colors, it brings out all the femininity in you. Yikes. It’s impossible for me to remember what I was thinking. But it was a different time, and I was doing my best. And clearly there was no staff copy-editor to catch all those inconsistencies.

For my next column, which I titled “Comfortable Casual Carefree”, I discussed the merits of the pant-suit. Just when you thought it couldn’t get any worse, I included illustrations.

Although I continued my new writing career through the year, I think two examples are enough for you to get the picture. Saying “we all start somewhere” feels like a rather large understatement in this case, don’t you think?

March 22, 2017

March 2017

Testing the Future Waters…

In my previous post, I shared the story of my first publication: “An African Adventure.” I was ten years old and the story was a few hundred words. By age thirteen, I was trying to broaden my writing horizons, and thought it was time to start my first novel.

I found these pages stored in the one small box I have – the memory box, if you will. It’s about the size of a small printer box. It’s travelled with me to every home I’ve lived in, or been stored somewhere between moves. I have nothing of my childhood or adolescence apart from what’s inside it. One box. That’s it. I remember some of my favourite things, and now rather mourn them, wishing I could see them again out of pure nostalgia. There was a little jewelry music box shaped like a pagoda, with a tiny geisha spinning inside her black lacquered home, a microscope and slides, a flat cardboard box with gemstones glued into separated squares (I’m not sure why I loved that, but it left such a strong impression that it’s showing up in my novel-in-progress), a set of wooden castanets painted with large, gaudy flowers (I never did get the hang of them), and a chocolate-brown ceramic piggy bank. All of those things disappeared, without a trace, as the saying goes.

But I do have my box, and everything in it is paper. There is one book, and one only: the used copy of Greyfriar’s Bobby I bought for myself at a church basement sale when I was seven or eight. There are some report cards – the less said about those the better, yikes. There’s a stack of my Royal Conservatory Music diplomas and some old theory books. There are a few ticket stubs and paper flowers from school dances. And then there are the things that I wrote.

A construction paper booklet of rhymed four-lined poems, with pictures I drew and coloured, tied with red yarn was my first attempt at creating a book. There is a “two-year” diary from when I was nine and ten. It’s very small, and has five days to a page. By the lack of writing space, it’s clear this was a diary created for children with little happening in their lives. I dutifully filled out a lot of those pages with dull one-liners: “Went tobogganning (sic) with Randy and Tim. Cold.” There is my first story publication – see above, the awkwardly named African Adventure. And also my first shaky steps at writing a novel.

I was thirteen. What did I love to read about when I was that age? Without fail, the protagonist was brave and determined and competent, orphaned or in some sort of “cast out from home and alone and in danger” situation. Setting? A place foreign to me. Hopefully exotic. The plot might have focussed on trying to find or connect with a lost loved one, or it might have been the struggle for survival against human or geographical danger – and in the best case scenario, a combination of both plot points!

Oh, wait. Isn’t that what I write about now? Wow – I’m currently writing about what was dearest to my heart as barely an adolescent, decades – and I mean DECADES – later. That speaks very strongly to where our life-long passions lie: what interests us, and what we want or need to explore.

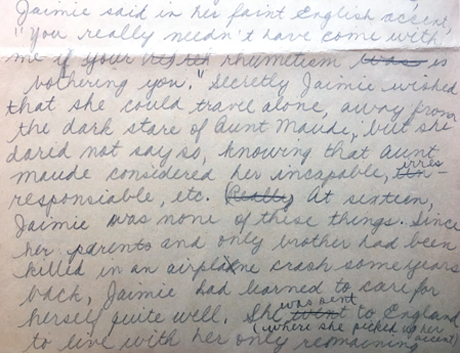

So the plot of my first novel goes something like this: Jaimie, a plucky Canadian girl, orphaned (of course) but sent to live with a cranky and unloving (naturally) old aunt in England (here we go, forced to leave all that is familiar) travels to Barcelona (another journey, this one getting exotic), and while there, discovers…well, I didn’t get that far.

At that age I had graduated to reading classics, and had discovered England through Jane Eyre (orphan), Oliver Twist (yet another orphan) and Pip (ditto) from Great Expectations. As to Barcelona? What did I know about Barcelona, or anything Spanish, for that matter, apart from those castanets? I would have used the “B” encyclopedia at the library to find out what Jaimie might experience: what she’d eat and drink and what the air smelled like and the look of the buildings and how the people were unlike any she’d previously known. I clearly liked in-depth researching in what I was interested in, even at thirteen. I still love researching. See where I’m going with this?

There are about six pages, written on unlined yellow paper. The novel starts with Jaimie on a rocking train from England to Spain (active beginning) thinking about her dead parents and former life in Canada (backstory). In Barcelona, she’s immediately and shockingly lost (promising hook) on the winding, beautiful, and yet at times threatening streets. And that’s as far as I got. I wonder now: what was Jaimie’s goal, apart from surviving? What was the conflict, apart from being alone and frightened in unfamiliar terrain? What would her character arc have been?

Some things are an intrinsic part of who we are. Could anyone have made me want to research and write a novel when I was in grade seven or eight? By Junior High, I was not a keen or particularly accomplished student – and I have the report cards to prove it. I did only what was necessary to get by. All I really wanted to do was read – and, in this case, write – and not be bothered by pesky homework assignments and what I deemed to be uninspiring class projects.

Finding these pages made me wonder why I let my beloved gemstone box and microscope and other treasures disappear, and kept those messy, hand-written pages. Was it a small voice in my head telling me that this really wasn’t the end? Okay, it was the end of this novel attempt, but it wasn’t the end of writing for me in the same way that jewelry boxes and piggy banks are naturally outgrown.

I think I knew I was on to something, even at thirteen.

An African Adventure

January 28, 2017

January 2017

The Elusive Fifteen Minutes…

Fifth grade. I was very shy, and rarely spoke or answered questions. I still remember, with complete clarity, the day that changed. It was one of those grey prairie November afternoons, snow swirling outside the classroom windows. Mrs. Bean, my teacher, brought in a portable radio. She plugged it in and fiddled with the dials. Then she announced that as a special treat, we would hear a story written by one of our very own students. She had sent a story I had written as an assignment to a contest sponsored by the Department of Education, and it was one of the handful of stories from Manitoba chosen to be published in a little booklet, and read aloud on the radio. I was stunned as she made this announcement, and could only stare at my hands in my lap, too shy to even look up as I heard my words read by a rather sonorous male voice. Later Mrs. Bean gave me the booklet containing my story, “An African Adventure”. Now I smile at the realization that I was into writing about foreign lands even at ten years old, never having left my small prairie city.

Suddenly I was a minor classroom celebrity. What I can only recognize as an adult is that the new feeling I had was a kind of empowerment, something I’d never known at home or in school.

I started to talk in class. I’d put up my hand when I had an anecdote or story that related to something Mrs. Bean was speaking about. She’d always call on me, bless her. Now I sense she realized she was witnessing an awakening of sorts, and, as a caring and involved teacher, she wanted to nurture those tenuous attempts.

And then, after too short a time of the joy of suddenly bourgeoning confidence, a boy sitting behind me – let’s call him Bruce – whispered loudly as I raised my hand, “There goes Linda again. Why doesn’t she shut up? We don’t care about her stupid stories.” Surely I’m paraphrasing, but that’s what I remember hearing. My reaction? Immediate shame and horror. Nobody cared? We – which I imagined meant everyone – wanted me to shut up? My stories were…STUPID? I put my hand down.

One harsh critic, and I was silenced. Why didn’t I turn to Bruce and say something along the brilliantly childish lines of, “No, YOU shut up.” Was he jealous, or bored, or didn’t like me or actually did like me and wanted my attention – for whatever reason, he silenced me. I’m sorry that the ten-year old me was so lacking in conviction. And that was it for the rest of the year. I reverted to my old silent behaviour, shaking my head when Mrs. Bean, for a while, tried to draw me out.

It took me decades to find story-telling confidence again, to ignore my childhood fear that what I had to say was not pleasing everybody – which we know is impossible. In publishing, there are reviewers and critics who, if we let them, might be that whispering voice that our stories aren’t worth hearing. But we have to ignore the negativity and go forth bravely. Harper Lee knew all about it: “I would advise anyone who aspires to a writing career that before developing her talent she would be wise to develop a thick hide.” Good old Harper Lee; she speaks for all of us who live our lives in the creative vortex.

I’m thankful for intelligent, fair, constructively critical readers and reviewers, but with every new piece of writing we send out into the world we face the same challenge: how will it be received? It’s clear that fame – however you define it – is rarely lasting. But those fifteen minutes Andy Warhol spoke about can come again, and again. Sometimes we have to reinvent ourselves, and use our words in different ways, toss them out into the void and see what happens. We’re lucky enough to live in a democratic society, where we’re free to speak our opinions and write our stories without censor. We are allowed to have our voices, and we should never allow anyone to bully or shame us into silence.

Stay strong, writing sisters and brothers.