Kimberly Knutsen's Blog

November 12, 2019

On Being a Crappy Girlfriend

October 1, 2018

Pearl

On Monday, Pearl brushed her teeth with salmon-flavored toothpaste and got dressed for school. When she climbed on the bus—moldy windows and torn seats—her best friend Poppy, who everyone called Seed, smiled and said, “Mmmmmm, salmon.”

“What did you use?” Pearl asked.

“Chicken, like always.” Seed sighed. “Mom won’t let me try salmon until all the stupid chicken is gone.” She pouted prettily, and the bus driver slammed on the brakes and shouted, “Butts in seats. No lie. Do it now or you’re all out on your asses.”

Pearl laughed a loud, look-at-me laugh and purposely raised her butt off the seat.

Seed caught Pearl’s eye and laughed louder, and then Pearl laughed even louder and Seed laughed loudest of all.

Pearl stopped laughing and sat.

Seed, now the lone loud laugher on the bus, looked alarmed, and Pearl smiled inside, glad that her mom had bought her the salmon toothpaste the first time she asked.

*

On Wednesday, Pearl hopped up the steps of the bus, her secret sparkling inside like soda pop. “Sup, bitch?” she said, climbing over Seed to the window seat.

Seed looked alarmed. Her tight, pink twists pulled up her eyebrows, adding to her look of surprise.

“What is it?” Pearl asked as the bus lurched into traffic. A car honked, and the bus driver laid on the horn for a full thirty seconds before blasting Led Zeppelin. It sounded like a machine stomping metal in a factory.

“It’s…different,” Seed said, a pretty grimace on her face. “What kind did you use?”

“Peanut butter,” Pearl burst out, louder than she’d intended. She had been so excited, her secret bubbling and fizzing ever since she saw the new flavor at Safeway. Peanut butter? she’d thought when she saw the nut-covered tube on the shelf along with the other teen pastes. And then, Of course…peanut butter, and for a brief second, the world had made perfect sense.

But now, Seed was making a face and delicately pinching her nose, like the peanut butter was a bad choice, like it was wrong in some way Pearl had never anticipated. She turned away from Seed’s sympathetic grimace. She felt shame and like she hated her friend. Seed, she thought, the voice in her head dripping with disdain.

*

On Friday, the bus driver eyed her as she climbed on the bus. Gary, Pearl thought because that was his name. Gary was crying, sobbing really, Gary like a giant lump with pig-bristle hair and mournful eyes.

What is happening? Pearl thought.

Gary honked his nose into a hanky and told Pearl to “move it along. You kids don’t care. You don’t even know my name.”

Gary, Pearl thought again.

The bus pulled away from the curb slowly, as if it too were sad. A song that sounded like crying came over the speakers.

Pearl sat by Seed but ignored her, which was the best punishment she could think of. As she stared out the window, raindrops sliding and flower petals stuck to it, she could feel Seed staring at her, pleading for attention, and it made Pearl feel powerful and happy.

She had thrown her peanut butter toothpaste away thanks to Seed.

Her mom had yelled “No more waste in this household” when she found the nut-covered tube and told Pearl that no, she was not going to drive her to Dutch because now she was mad. Really mad. So Pearl did not get to go to Dutch and she had to use the peanut butter toothpaste—the bad toothpaste—because that’s all there was left—thanks to Seed.

“Pearl,” Seed whispered, her voice urgent. Pearl could smell her chicken-scented breath, her normal breath, like a cat, a normal cat, and she suddenly felt so desperate and alone tears burned her eyes.

“Pearl,” Seed hissed again.

Pearl inhaled and exhaled slowly. She imagined she was lying on a lounger next to the pool at the club having the best day of her life, all by herself because Seed was no longer invited to come along; Seed was never going to be invited again. Ever.

Seed poked her in the ribs, hard, and Pearl whirled around. Oh it’s on, she thought, excited—maybe more excited than she’d ever been. “What?!” she cried, glaring at her former friend.

“You know Danny B?” Seed asked in a low voice, nodding at the boy with eyes the color of river water sitting across the aisle playing sad drums to Gary’s sad music on the seat in front of him.

“Like, yeah,” Pearl said. “Do you think I don’t know the cutest boy in eighth grade who, by the way, said Sucks, brah when I cried when I fell up the stairs after choir?”

“Yeah, well, what you don’t know is that he uses peanut butter toothpaste now too. He started last week and now all the eighth-grade boys are using it and even some of the girls.”

Pearl stared.

“That means you were ahead of everyone.” Seed whipped her ponytail over her shoulder. “You knew peanut butter was good, and it was.” She clapped the next words out: “You. Are. A. Boss.”

Pearl stared some more. She could hardly believe what a boss she was. “Girl…what?”

Seed smiled and shrugged.

Is this happening? Pearl thought.

A moment later, brakes shrieked and the back end of the bus flew up and onto the curb, smashing into a tree, sending kids flying into the aisle.

“What the fuck,” Gary said. He stood and gathered his bag like a purse, like Pearl’s grandma’s purse, and walked off the bus. Nobody else moved.

Pearl looked at the heap of kids in the aisle. She saw feet and a trumpet and a beanie without a head. Her eyes met Danny B’s and he smiled, his hair black with blood.

Peanut butter, Pearl thought, and for a moment everything made perfect sense.

Peanut butter, Pearl thought, and for a moment everything made perfect sense.

June 20, 2016

Summer Solstice Meditation

Summer Solstice Meditation

This is the light of the mind, cold and planetary

… Sylvia Plath, “

The Moon and the Yew Tree

”

Sit quietly in an easy seated position. Let your spine be long. Imagine a string running from your tailbone up your spine and out the crown of your head. Imagine someone pulling up the string, lifting you into a nice alert position.

Focus on your breathing. Let go, let it flow. Relax your arms and legs. Relax your root chakra (private parts), relax your internal organs, your heart, throat, eyeballs and brain. Keep letting go. Let thoughts pass like clouds in a summer blue sky. If you start thinking, say to yourself, “thinking,” and focus once again on your breathing.

This is a good time to use a mantra, words that help calm the “monkey mind” and set one’s intentions. I like nam myoho renge kyo.

Get in touch with your root chakra, at the tip of your tailbone. This is your lowest chakra, and it grounds you. Open this chakra down into the earth and feel safe. It’s the seat of your life force. It’s also your sexy chakra. In your root chakra, picture a fiery-red hibiscus flower. Sexy, hot, fresh and alive. Let the fiery-red glow fill your lower parts. Oo-la-la.

Now focus on your second chakra, in your belly. This is the seat of creativity. The color is orange. Imagine a hot-orange Tropicana rose filling this area with radiant life. Smell its wonderful smell. Let the Tropicana rose turn into a Peace rose, a soft soothing yellow with pink-tinged petals. Focus on this pinkish-yellow glow. Let it fill your belly with a deep sense of peace. Send this out into the world.

Your third chakra is located in your solar plexus. This is your strength center, your powerful core, physically and spiritually. Imagine a fiery yellow-white sun. Let its heat and roar fill the center of your being. Feel the power within. Your third chakra helps you hold your space in the world. It can be the seat of “no,” as in, “No, I will not be on that committee,” or “No, I will not drive you across town during rush hour when it’s 103 degrees out.” Enjoy connecting with your third chakra power center and saying “no”—without apologies or explanations or unnecessary smiles. You rock!

Your fourth chakra is your heart chakra. It is the center of your being. Open your heart. Send love out into the world. Open your heart. Receive love from the world. Let your heart center fill with green light. Imagine a beautiful tree bursting with green leaves. Let its branches and buds open, sending tendrils of green healing light out into the world. Feel this light glowing in your heart center.

Your fifth chakra is the seat of your voice. Sometimes this chakra can become constricted. Women are often encouraged to be silent. On the flipside, our voices are often not heard. Fill your fifth chakra with a glittering blue light. Imagine a volcanic lake—like Crater Lake—ancient, wise and deep. Harness this cool and immense power. Speak your truth.

Your sixth chakra is located in the space between your eyebrows. This is your third eye, the seat of intuition. The color is indigo, a dark violet-blue. Imagine a deep, dark midnight sky, full of starry light. This is the dream space. Focus on your third eye. What dreams dance here? Send them out into the world. What visions come to you? Thank the universe for its wisdom.

Your seventh chakra is located at the crown of your head. The light is lavender. This chakra connects you to your higher spiritual self. Imagine a thousand petal lotus flower, a crown of violet light. You are a queen. Let your higher self speak to you. Let violet light cascade down from above, filling your body, mind and soul.

Sit in seated meditation for as long as you like. Enjoy the color-drenched energy and light filling your entire being. Know that you are one with the wisdom and beauty of the natural world.

Namaste.

Quick Guide

Chakra Color Seat Image

Root Chakra Red Life force, sexuality Hibiscus flower

Second Chakra Orange Creativity Tropicana rose, Peace rose

Third Chakra Yellow Power center Sun

Fourth Chakra Green Heart center Tree

Fifth Chakra Blue Voice Lake

Sixth Chakra Indigo Third eye, intuition Midnight sky

Seventh Chakra Purple Spirituality Thousand petal lotus flower

June 15, 2016

On Being a Crappy Girlfriend

Yesterday, I talked to Steve, an old boyfriend circa 1988. He’d found me on Facebook, and we talked on the phone. I’d always wondered how Steve was doing, and I also felt kind of guilty because I was kind of a jerk in a petty, princess-y way. We argued a lot, and I wasn’t super nice, and things faded away after I moved to Las Vegas. Steve and I hadn’t spoken since 1991.

Steve and I met at the old Willamette Diner, a rollicking 1950s-style restaurant on the banks of the Willamette River, where we worked as a busboy and waitress, respectively, with bosses who seemed pretty nice until they fired both of us.

I was fired for two reasons: one, the big boss Joe said if I was late again, I was fired. Well, I was late again, and I was fired. However, the day I was fired, before the final chop, Joe told me to put this giant bag of ketchup in this dispenser on the wall. I thought it was weird. The bag weighed about fifty pounds, I could barely lift it, and I was supposed to heave it up into this ketchup dispenser on the wall? Bizarre.

At every other restaurant I’d worked at, we had ketchup bottles that you “married” at the end of your shift during side-work, which was the worst part of any restaurant job. (Marrying meant to pour the ketchup from one bottle into another, so you had fewer, fuller bottles. The more accurate word would be “mate.”) Sometimes the girls at this other restaurant I worked at, which shall remain nameless, added water to the ketchup and shook it so it would be thinner and easier to marry/mate, which I now think must have violated all sorts of health codes.

Anyway, I lifted this enormous plastic bag of ketchup, dropped it into the dispenser—the dishwashers shouting instructions, steam billowing from their sprayers—and suddenly the bottom plug pops off, and I’m standing in a tsunami of what seems like ten tons of ketchup, pouring all over my hands, all over my legs, all over my white uniform and white tennis shoes, a bloodbath of ketchup, and the dishwashers are screaming at me to “turn the spigot, turn the spigot,” and I’m thinking, what fucking spigot are you talking about?

I try to cover the spout with my hands, and it’s like trying to plug a hole in a dike when an entire ocean is flooding over you, and suddenly my legs are burning—ketchup is really acidic, and I’d just shaved them, which I remember thinking made the burning worse, although now I’m not sure why I thought that—and finally, the whole thing stops because all fifty pounds of ketchup is all over the floor and all over me.

The big boss comes out of his office, his tomato face steaming red, and I’m fired. As in: Right now. As in: Walk to your car doused in ketchup like the giant hotdog loser you are and drive home.

So this is where Steve and I met. By the time of the great ketchup massacre, he had already been fired—I don’t remember why.

I liked Steve because he looked like Axl Rose in Guns N’ Roses—he even wore the bandana tied around his head. He had long hair and a great sense of humor. My girlfriend was also dating a guy who looked like Axl in a different way, and we liked to talk about how our guys looked exactly like Axl. Mine looked like a younger Axl, circa “Welcome to the Jungle,” and hers looked like a meaner Axl. This was how shallow we were at age twenty-one. It all was all too exciting.

Steve and I had a lot of fun hanging out at his apartment across from the Willamette River. (Fellow Portlanders, he and his cousin paid $350 a month rent.) We both loved rock music. We’d talk for hours about lyrics, songs, was there any band greater than the almighty Led Zeppelin, who was a true rocker, who was a poseur, and what exactly were the Temples of Syrinx?

We listened to music all the time. We both liked to smoke. Steve, a doggie-downer, liked his 40-ouncers of Schlitz, and I, a puppy-upper, liked my Diet Coke Big Gulps. We were into Kingdom Come for a while, and I still think “What Love Can Be” is a great song.

Steve and I also fought. We argued all the time, and it was all about petty shit. Steve would get insecure and depressed and pout, and I’d call him el bebe grande, and then he’d pretend to be a baby and hold his feet and roll around on his back and say “waah, waah,” and we’d laugh hysterically.

Sometimes his cousin, the beautiful Mimi, who worked as a cocktail waitress at Stuart Anderson’s Cattle Company in Milwaukie, would break out the Aqua Net and rat Steve’s long hair so he looked more Poison than G N’ R. She’d put eyeliner on him, tie one of her sparkly scarves around his head, and make him wear a vest with no shirt. It was all so glam and exciting!

Steve and I fought a lot about pizza. I felt that I paid for everything, and I started to get mad about it, so one time after we ordered pizza, we sat in my parents’ dining room (I still lived at home) and had a stand-off, staring first at each other and then at the Pizza Hut box on the table. I’d paid, Steve hadn’t. I didn’t want to give him any because I felt he was being a mooch. He wanted some because he was starving.

“I have 87 cents,” he said, digging change out of his pocket and dropping it on the table, and I said, “OK, you can have one piece.” Wow. Looking back, I’m so ashamed. I was trying to make a point about how the lady shouldn’t have to pay every single time (I’d gone out with a lot of broke rockers by then) but what a bitch! It’s pizza! What, were you going to eat the entire thing yourself?

One time, though, Steve and I bonded over pizza. We’d ordered it from his apartment, and it was during the time Domino’s had the rule that if it wasn’t there in thirty minutes, it was free. The pizza guy arrived at the thirty-seven minute mark—to his credit, it was New Year’s Eve—and we were so excited. Free pizza!

Steve, who was shy, went out and broke the bad news to the pizza guy. “10:26,” I yelled after him. “It was supposed to be here by 10:26.” Oh my God. What an idiot. First, I made Steve do my dirty work (I was paying), and second, what if the drivers got in trouble if they gave away too many free pizzas? What if they had to pay for them? Decades later, I feel bad.

Another time, Steve and I drove out to the gorge and picked a ton of sage—why, I have no idea. I do know we listened to Jimmy Page’s Outrider on that trip. Driving home that night in my old beater Fiat that went into death throes once you hit 45 mph, I was overcome by the strong smell of sage and had a terrible panic attack. The medicinal smell was overpowering, it was too much, and it scared me (even now, I couldn’t tell you why). Steve laughed as I shouted, “roll down the windows, roll down the windows,” and he kept saying, incredulously, “a smell can’t hurt you, why are you flipping out?” Good times.

Later that summer, I moved to Las Vegas to dance and go to UNLV. Steve visited. I was working in a nightclub as a cocktail waitress, the Shark Club on the Strip, and bought Steve a pair of M.C. Hammer parachute pants from the club, which he still has.

One afternoon, Steve and I argued, and he disappeared for hours, stomping off into the desert across the street from my apartment. I was so scared. “He’s in the desert,” I cried to my mom on the phone. “What if he’s lost forever?”

“Calm down,” she said. “He’s in a major city. Someone’s bound to find him.” Which is exactly what she said when my orange cat disappeared for six days.

Steve did return, later that night, and just as the cat had, he hopped the back fence and stood at the sliding door peering in, hands (paws) pressed against the glass, the black desert sky and a spray of stars swirling out behind him.

Looking back, I see that Steve’s moods, his pouting, were because he battled depression, and I feel bad for the young guy he was. But back then, I hadn’t raised three kids—life hadn’t brought me to my knees—and I had very little patience. It was all about me. Why are you bringing me down? Why can’t we just have fun?

After I returned from Vegas, before moving to New Mexico for graduate school, Steve and I had one great night. We went to a movie, then hung out at his mom’s house in Vancouver. He showed me a picture he’d drawn. It was me as a mermaid: long blonde hair, better boobs and a smaller waist, a fabulous, iridescent tail.

And yes, I know it sounds ridiculous, but I was thrilled. Steve was (and is) a stunning artist, but more than that, he knew me. Steve knew that if asked what kind of animal I’d like to be, I’d say “a mermaid.” He knew the ridiculous, princess-y, obnoxious mess that I was, and he liked me despite, or maybe even because of, it.

During our recent phone call, we talked about our lives. Steve never had kids. In the last few years, his mom, dad and stepdad died. He’s struggled with addiction.

I told Steve that my kids’ dad was in prison—life without parole—for a murder he committed while out of his mind on drugs. After the obligatory I’m sorry to hear that, Steve blurted, “You always did like losers.” He hesitated. “Like me.”

I laughed at his harsh self-assessment, but it made me sad. Steve wasn’t a loser. He was kind and a good friend, and like the rest of us, he’s struggled. I reminded him of that last great night in 1991. After he showed me his artwork, we went out into the foggy, wet night and ended up at the train yards, talking and laughing like old times. Steve pulled me close. His coat smelled like rain. We set a penny on the tracks, then screamed at the top of our lungs as the train rocketed past, our breath billowing in the icy air, just two young dumbasses, the rest of our lives, like the train, hurtling toward us, and we had no clue what was to come.

I like to think that along the way, through the people we meet, we store up kindness to see us through the difficult times. I still have the flattened penny from that night. It sits in my jewelry box along with a lumpy ceramic angel made by my then six-year old son (he’s twenty-one now), and worry beads I’ve had since age five (I’m fifty now).

Like that surprising flood of ketchup so many years ago, life shocks the hell out of us. It rushes past. We rush through it. Goodness, eternal and warm, a sticky penny in our palm, stays put.

January 9, 2016

Gerbils: A Love Story

Rodent dreams. Little ears and walrus whiskers. I can’t stop watching videos of capybaras soaking in Japanese hot springs.

They’re like giant gerbils, and they seem so peaceful and wise. But I notice that the tourists petting them avoid the belly, even when they flip over and stretch seductively. Anyone who’s been caught in a cat’s “bear trap” knows this trick. What would a capybara bite feel like? They’re rodents; they must have giant teeth.

I would rub the tummy, but I’d be afraid. I’d do it, though—if the critter indicated he might like it—my heart racing. I want to pet a capybara. I wish one were sitting on my desk right now. No, on my lap.

What do they smell like? I imagine dirt and wet dog and a bit of eau de guinea pig cage. They remind me of Labs. They look dumb in the best sense of the word: clowny and joyful and laid back. They know the importance of a good spa day.

There are lemons—whole lemons—floating in the wooden tubs with the capybaras, and Japanese hand towels. It’s all so elegant, silent, dignified. Snow blankets the ground. Steam fills the air. I wouldn’t mind being a capybara in my next life. My life now is loud.

˜

My oldest son Matt has quit smoking pot. It’s been twelve days. Last night Matt’s girlfriend Natalia told me, “Matt said you said it was OK if he smoked pot once a week.”

When Matt came home from work, I told him I did not say it would be OK if he smoked pot once a week. What I did say was that it would be nice if he were the kind of person who could smoke pot once a week, but he’s not. Pot is his kryptonite.

“No,” Matt said, dumping cheese on Doritos and sticking them in the microwave. “You said if I only do it once a week, that’s fine.”

“No, I didn’t.”

“Uh, yeah you did.” Matt rolled his eyes.

“No, not. Why would I say that? You can’t—”

“Whatever.” Matt shook his head like I was the biggest dumbass on earth. He picked up his plate, a tube of Pringles, and a beer and brushed past me, bumping my shoulder as he went.

Goddammit. I lost it. I got loud. Why was he so rude? Why was he twisting my words? “If you smoke pot in this house,” I yelled up the stairs, “you’re moving out. Instantly. No thirty-day notice. You are not a rock star, and this is not your pad.”

“Pad,” Matt said with a laugh, and his tone was so disrespectful, his thinking so wrong, I sank into a black hole—the one that sucks in controlling, powerless, codependent moms of adult pot-smoking children.

I spun in the black hole with the other martyred moms: moms who go to work every day, moms with “cheery” attitudes and no husbands, moms in pantsuits with gray roots and tired eyes. We cried silent tears. We felt destroyed. We asked God, “What the fuck is this? Do they ever grow up? Do they ever go away? And you want me to deal with this and perimenopause? Are you high?”

My loud, hateful thoughts turned into frantic, fear-based thoughts. If Matty smokes, he’ll smoke all the time, and I’m scared for him. He’s my oldest boy, my big boy, and I’m afraid we’re experiencing “failure to launch” because he’s twenty-one and still hasn’t moved out—he’s moved his girlfriend in, the lovely Ukrainian Natalia whom I love as my own, and not just because she’s such an eager snitch, but still—

The black hole spat me out.

The kitchen smelled like rain. Matt was working as an elf—a seasonal delivery driver for UPS. He’d set his wet tennis shoes on the heating vent. His brown jacket hung dripping from the bathroom door. His glasses sat on the kitchen counter, dotted with raindrops, steamy from the warm air inside. Matt was a good boy. He was working; he was trying. Life is hard. No one gets it right.

I ate six Hershey’s Kisses, the candy cane kind that aren’t even good. Then I took a bath.

˜

A human, not a rodent, soaking in hot water. No lemons. No snow, no steam. Only the strong scent of my middle son’s Axe body wash.

I stared at the wall near the ceiling, wondering for the millionth time what those two strange brown spots were. They’re identical, the size of a quarter. They look like they’d be soggy if you poked them, and once poked, a million wasps would come buzzing out. Or an entire farm full of ants. Or rats: big rats, baby rats, mama rats and middle-school rats. Our Portland neighborhood is infested with rats. They’ve entered our home—and not always willingly. I found a live baby one on the counter next to the cats’ bowl, and a big dead one, courtesy of the dog, on my pillow—a turndown gift, like a mint.

I stood on the edge of the tub, praying no one would barge in, and poked the spots. Nothing happened. I scrubbed at them with a towel. The spots remained. It isn’t mold. It’s a mystery.

As I dressed, the fight with Matt faded. I lost interest in the spots. I was thinking of my friend. Tall, handsome, kind John with his Roman nose and wire-rimmed glasses. John is a scientist. He has the perfect answer to all my hypochondriac questions: “You’re fine, you’re healthy as a horse, you’re going to live to be a hundred and two.” John thinks I’m obnoxious and a “princess” who spends way too much at Starbucks—and still he loves me.

I love him too. He is genuinely good. He sees the best in everyone—well, there’s this one guy at work who really gets his goat, but beyond that… At movies, John cries so hard he has to take off his glasses and wipe his eyes with a hankie. Yes, he’s the kind of man who always has a clean handkerchief in his back pocket and a box of Kleenex in his truck. If you’re hormonal, he’s ready.

Two months ago, John found blood in his urine. He has cancer. Bladder cancer. No. Yes. No. I remember the moment he told me. He’d gone to the doctor—we were sure it was nothing. I was in the living room sweeping up dog hair. It was close to Halloween. All the grass was dead and the pumpkins glowed in the late afternoon sun. My phone buzzed. It was John: “Are you sitting down?”

It was bad news. The sitting down kind of news.

We’re still in the “ignore it” stage. John feels healthy and acts healthy, so how could anything be wrong? We rarely talk about it. We still fight. I bitch and complain. He’s negative. Nobody’s drinking kale smoothies, or flying to Mexico for alternative treatments, or visualizing the bladder full of orange, healing light. Well, I am—the visualization part—but how is that going to help John when he thinks it’s “a bunch of horseshit?”

We ignore the elephant—no, the giant capybara—in the room. John will be fine. John will be fine. Johnwillbefine. The truth is, I’m afraid we’re at the beginning of a long journey that won’t end well. But, when you think about it…isn’t that life?

I closed my eyes. I quit thinking altogether.

Matt called me into his room. He’d taught himself to play “Wish You Were Here.” There were a few false starts. “Check it out, Mom. Strum, strum, fuck! OK, check it out. Strum, strum, shit!” Then he got it and it was good. Natalia and I applauded.

“And I’m not smoking.” Matt set down his guitar. “It’s been like almost a month.”

“Yay,” I said, purposely not correcting his math.

He gave me a puppy-dog look. “Will you please bring me some water? And make no-bake cookies?”

˜

A giant capybara stands—sits? It’s hard to tell; they’re all shaped like pears—under an outdoor bamboo shower. Hot water drips onto its head. It closes its eyes, blissful.

I keep looking for the rub. Is the hot springs a ruse? Is this how the capybaras are rounded up before being led to slaughter? Do relaxed capybaras make for more tender meat? Do people eat capybaras? I shudder, remembering the time my daughter googled guinea pig and was greeted with an image of two: braised and on a plate, ready for dinner.

Are these jumbo rodents as peaceful as they seem? Or do they fight to the death when the cameras are off?

Who are these capybaras, and why am I too lazy to Google any information about them? Giant, happy rodents bathe on my computer screen. I don’t want to know more. It’s the mystery I love.

A big one—the size of an English bulldog—sleeps, two mini ones curled at its rump. I watch it breathe, in an out, so slowly, as it dreams its scritchy dreams. I notice a grasshopper on its back. It darts. Shit, it’s a snake, no a lizard! I wasn’t expecting that. The reptile slithers into the grass. The capybara twitches in its sleep.

Another one goes underwater—the sides of the tub are glass—and just sort of walks around. It moves blindly, eyes closed, like an old person in a pool. I wonder again if they bite. I’m reminded of a story. Gerbils. Giant gerbils. Little gerbils. Oh, how I wanted gerbils.

˜

I’m nine and I’ve read the book and I’m ready to be a full-fledged gerbil owner. A responsible gerbil owner. I actually wanted the Teddy Bear Hamster, but my mom said no. Anything too cute is immediately denied. There’s a limit to cuteness in our house. No Pulse or Lawman jeans, only the itchier J.C. Penney brand. No salon haircuts. My mom gives me and my siblings—and several of the kids on the block—identical choppy bowl cuts. A thirty-second sit down in Judy’s living room, and you’re good to go, ready to fly back outside and play Red Rover or doorbell ditch or watch Shirley swing the dead possum by its tail, or whatever it was you were doing before your mom told you to go inside and get those goddamn bangs out of your eyes.

The Gerbil Story

I am nine, in my bedroom on 31st street with my best friend Kelly. I’ve finally wangled gerbils—which is ironic, as for the rest of my life I’ll have a severe rodent phobia. But I’ve got my gerbils, happily gerbil-ing in their fluff in their cage like a birdcage, and life is complete.

Kelly and I are holding the gerbils. They are scary-fun—the best kind of fun. I can still feel the thrill in my belly, the gerbil in my hand—ugh!—scampering up my arm, up to my neck, its sharp claws poking my skin, the whiff-whiff of its breath against my neck, the naked tail—argh!—its breathing, so fast and birdlike, what if it goes in my ear?! And then—

Kelly screams. She’s still holding her gerbil, but her hazel eyes have grown enormous, for it has bitten her thumb. The gerbil’s bitten Kelly and she’s screaming. I see bright ruby blood, the brightest, reddest blood I’ve ever seen, welling jewel-like from her thumb, and the gerbil is still attached. I can’t believe it. “Get it off, get it off,” Kelly shouts, panicked, and now she’s getting really pale, all the blood draining from her face, out of her thumb, blood dripping on the hardwood floor, the gerbil gripped, chomped down permanently and forever to her thumb, its little body flinging back and forth as she tries to shake it off, its beady eyes bright, determined to never let go of my friend.

I call for my mom. Kelly keeps trying to shake the gerbil off—why won’t it let go?—and now I’m crying and scared, what if it never lets go, what if it bites Kelly forever? And then—whap. The gerbil flies across the room and hits the wall on my little sister’s side with a loud thump, then slides to the ground and lies there. Unmoving.

Oh. My. God. Kelly’s hurt, and we’ve hurt the gerbil, slumped against the wall, stunned and motionless. Is it dead, is it dead? Blood dripping, blood smeared on the gerbil’s chest, and I’m crying. Suddenly, I no longer like this gerbil business, and I yell once more for my mom who comes running as I collapse to the ground, hands on my head in a duck and cover position. I hate them, I hate them. This is really, really bad, make it go away.

I was a highly emotional child.

My mom picks up the gerbil. She rubs its bloody head. It blinks. It’s alive. We put both gerbils back in the cage (for I was gripping my gerbil the entire time). “Now it’s time to calm down,” my mom says, hands on hips. I wipe my nose on my shirt. I recover. Kelly is bandaged 1970s style: no trip to the doctor, no antibiotic ointment, no rabies shot—she has a giant rodent gash on her thumb, but my mom just runs cold water on it, slaps on a Band-Aid, and we go outside and play.

˜

There’s more.

The Gerbil Story, Part Two

The next day I walk to the cage, full of trepidation, no longer excited about these gerbils of mine. With power, the owning of pet rodents, comes great responsibility, and it weighs heavily on my nine-year-old shoulders. I watch the gerbils. One of them is doing its gerbil thing, shredding up a toilet paper roll, its black eyes starbright and alert, and the other…isn’t moving. I poke it. Its head falls off. Yeah, you heard me: The second gerbil’s head falls off. The alert gerbil, the gerbil with the intact head and the curious starbright eyes, which I now realize are pure evil, has eaten his cagemate. He’s eaten his friend, chewed its head almost all the way off. And when I poke said friend, fluff falls away from the carcass and the head plops to the bottom of the cage.

I yell for my mom.

“Ooh, ick,” is her response. She sets down her coffee cup. “Go get me some toilet paper.” She hesitates, a grim look on her face. “No, go get your dad.”

A sick horror seeps into my veins. Once the dad is called in, you know it’s really bad.

My mom tells me to “quit fussing” and go wait in the hall. As I crouch outside my bedroom door, the linoleum cold on my bare feet, I devise a story in my mind: The evil gerbil with the starbright eyes is the one that bit Kelly, the one that got fwapped against the wall on my little sister’s side of the room. He was so traumatized by his flight through the airspace of Kimmy and Krissy’s room that once safely back in his cage, he proceeded to eat his cagemate, his lady friend.

Now, I have no idea if those gerbils of mine are male or female, but I instinctively think of the bad one as the man and the cannibalized one as the lady.

˜

Gerbils: Day Three

I tiptoe to the cage, sick in my gut. I really hate gerbils now. Maybe I shouldn’t look. Maybe I should go back downstairs and watch cartoons. If I ignore the remaining gerbil, will it go away? Well, yes, eventually. But no, I’m the responsible gerbil owner. I read the book. It’s my duty to change its water, feed it and clean its cage.

I force myself to look.

The remaining gerbil is no longer alert, curious, doing his gerbil thing. He is unmoving. My heart explodes. I shut my eyes tightly, reach out a tentative finger, and give him a poke. He doesn’t move. I open my eyes, too afraid to poke him again. Either way, he doesn’t move.

For the third time in three days, I yell for my mom.

She thumps up the stairs, sets down her coffee cup with a sigh, and pokes the probably dead gerbil. She pokes it again. After one final vigorous poke, she pronounces it dead.

This is it. The great gerbil experiment of 1974 is over. Done. I don’t know if I’m more horrified or relieved.

As my mom takes the cage way, saying, “Well, this was a waste of money,” I look at my hands, my fingers pinched together from the stress of the entire episode. I hate gerbils, I tell myself. I hate them, I hate them. At the same time, I’m heartbroken. Why did my gerbils not turn out right? Why did my gerbils go so awry? Why did I get the bad gerbils? Why, why, why?

I tumble back through time. The wanting, the years of wanting, and the book with the illustration of the perfect Teddy Bear Hamster—the right kind, Mom! The kind I wanted in the first place. The kind that doesn’t eat its friends. But no, it was too cute, and there could never be anything too cute in our house. We only ever got vanilla ice cream. Why? Because it was plain, and anything else would be too fancy.

The yearning, the whining, the begging, the pleading, the book with the picture in it, with the instructions that I read, that I memorized—The responsible gerbil owner will change the water daily. The responsible gerbil owner will provide a wheel for their pet. Gerbils want and need daily exercise. Watch them go for a ride!—and then the trip to the pet store up on Woodstock, the gerbils, two gerbils because two are always better than one. The two gerbils in a box—gerbils in a box, gerbils in a box, the thump-scritchy-thump of gerbils in a box—and the cage, the cheaper one like a birdcage, gold—it was so pretty—but was it a gerbil cage? Was it actually a birdcage? Was that why the bloody mayhem occurred, because the cage was too small? Even now, forty years later, I have so many questions.

˜

I now realize that when I watch the capybaras, I’m not in a state of relaxation, I’m in a state of hypervigilance. Look at them simmering in their fancy outdoor hot tubs like wannabe actors in a Burbank apartment complex. They lean against each other, close their eyes, relax their bodies, sink down until just their tiny ears are visible. So Zen, so laid back, so…dangerous.

Do they eat each other once darkness falls? Do they sink their teeth into the hands of unsuspecting tourist/belly rubbers? Are they lovers or killers? Madmen or just really chill spa guests? That’s the rub: I have no way of knowing (well, I could Google, but as I said, I’m too lazy). And while I love the mystery of the capybaras, I don’t trust them, not one bit. Who’s to say they won’t wreak havoc on this snowy, steamy Japanese resort town? How can I believe what’s right in front of my eyes?

When you think about it, that’s the problem with life, too—the rub, the tricky part. Are things as they appear—happy capys getting their hot tub on—or are there deeper, darker developments to come? Is it nothing, or is it something? Oh, mystery of life: how amazing, and how truly terrifying you are.

Will Matt stay “off the nip” and have a happy, productive life, spinning on his own mortgaged gerbil wheel with good-citizen determination? Will John’s high-grade cancer cells do the right thing and dissolve in their weekly bath of tuberculosis bacteria? Or will they grow angry and destroy a genuinely good man? And what about the spots on my bathroom wall? What the hell are those? Nothing? Or something?

I guess my only choice (for I’d rather be dead than bitter and jaded) is to force myself to see the good, to believe in the good: Matt, twenty-one already, and yes, he’s in my home, eating my food and running up my water bill, but at the same time, yes, it’s Matt, alive, my big boy, right here in my home. And John, the gerbil I always wanted—no, the Teddy Bear Hamster—the good kind, the right kind, the kind that sticks around. And here he is, sitting beside me in a movie theater on a rainy Sunday afternoon, big and warm and comforting, weeping into his hankie.

Back at my desk, I stare at my computer screen, wondering if my university has some sort of system to spy on us, to watch what we do all day long in our locked offices when we’re supposed to be grading papers. Do they know I’m obsessed with the capybara videos? Is there some sort of limit to how many times you can refresh cuteoverload.com before they knock on your door, hand you a pink slip, escort you off the property, and send out a university-wide email telling everyone you’ve decided to “spend more time with your family?”

Fuck it. I throw caution to the wind. I press play, lean back and watch, mesmerized, as fat, happy animals float in their lemon baths, enjoying themselves, in the moment. Breathing. At peace. Alive.

Gerbils: A Trilogy

Rodent dreams. Little ears and walrus whiskers. I can’t stop watching videos of capybaras soaking in Japanese hot springs.

They’re like giant gerbils, and they seem so peaceful and wise. But I notice that the tourists petting them avoid the belly, even when they flip over and stretch seductively. Anyone who’s been caught in a cat’s “bear trap” knows this trick. What would a capybara bite feel like? They’re rodents; they must have giant teeth.

I would rub the tummy, but I’d be afraid. I’d do it, though—if the critter indicated he might like it—my heart racing. I want to pet a capybara. I wish one were sitting on my desk right now. No, on my lap.

What do they smell like? I imagine dirt and wet dog and a bit of eau de guinea pig cage. They remind me of Labs. They look dumb in the best sense of the word: clowny and joyful and laid back. They know the importance of a good spa day.

There are lemons—whole lemons—floating in the wooden tubs with the capybaras, and Japanese hand towels. It’s all so elegant, silent, dignified. Snow blankets the ground. Steam fills the air. I wouldn’t mind being a capybara in my next life. My life now is loud.

˜

My oldest son Matt has quit smoking pot. It’s been twelve days. Last night Matt’s girlfriend Natalia told me, “Matt said you said it was OK if he smoked pot once a week.”

When Matt came home from work, I told him I did not say it would be OK if he smoked pot once a week. What I did say was that it would be nice if he were the kind of person who could smoke pot once a week, but he’s not. Pot is his kryptonite.

“No,” Matt said, dumping cheese on Doritos and sticking them in the microwave. “You said if I only do it once a week, that’s fine.”

“No, I didn’t.”

“Uh, yeah you did.” Matt rolled his eyes.

“No, not. Why would I say that? You can’t—”

“Whatever.” Matt shook his head like I was the biggest dumbass on earth. He picked up his plate, a tube of Pringles, and a beer and brushed past me, bumping my shoulder as he went.

Goddammit. I lost it. I got loud. Why was he so rude? Why was he twisting my words? “If you smoke pot in this house,” I yelled up the stairs, “you’re moving out. Instantly. No thirty-day notice. You are not a rock star, and this is not your pad.”

“We’ll see,” Matt said, and his tone was so disrespectful, his thinking so wrong, I sank into a black hole—the one that sucks in controlling, powerless, codependent moms of adult pot-smoking children.

I spun in the black hole with the other martyred moms: moms who go to work every day, moms with “cheery” attitudes and no husbands, moms in pantsuits with gray roots and tired eyes. We cried silent tears. We felt destroyed. We asked God, “What the fuck is this? Do they ever grow up? Do they ever go away? And you want me to deal with this and perimenopause? Are you high?”

My loud, hateful thoughts turned into frantic, fear-based thoughts. If Matty smokes, he’ll smoke all the time, and I’m scared for him. He’s my oldest boy, my big boy, and I’m afraid we’re experiencing “failure to launch” because he’s twenty-one and still hasn’t moved out—he’s moved his girlfriend in, the lovely Ukrainian Natalia whom I love as my own, and not just because she’s such an eager snitch, but still—

The black hole spat me out.

The whole kitchen smelled like rain. Matt was working as an elf—a seasonal delivery driver for UPS. He’d set his wet tennis shoes on the heating vent. His brown jacket hung dripping from the bathroom door. His glasses sat on the kitchen counter, dotted with raindrops, steamy from the warm air inside. Matt was a good boy. He was working; he was trying. Life is hard. No one gets it right.

I ate six Hershey’s Kisses, the candy cane kind that aren’t even good. Then I took a bath.

˜

A human, not a rodent, soaking in hot water. No lemons. No snow, no steam. Only the strong scent of my middle son’s Axe body wash.

I stared at the wall near the ceiling, wondering for the millionth time what those two strange brown spots were. They’re identical, the size of a quarter. They look like they’d be soggy if you poked them, and once poked, a million wasps would come buzzing out. Or an entire farm full of ants. Or rats: big rats, baby rats, mama rats and middle-school rats. Our Portland neighborhood is infested with rats. They’ve entered our home—and not always willingly. I found a live baby one on the counter next to the cats’ bowl, and a big dead one, courtesy of the dog, on my pillow—a turndown gift, like a mint.

I stood on the edge of the tub, praying no one would barge in, and poked the spots. Nothing happened. I scrubbed at them with a towel. The spots remained. It isn’t mold. It’s a mystery.

As I dressed, the fight with Matt faded. I lost interest in the spots. I was thinking of my friend. Tall, handsome, kind John with his Roman nose and wire-rimmed glasses. John is a scientist. He has the perfect answer to all my hypochondriac questions: “You’re fine, you’re healthy as a horse, you’re going to live to be a hundred and two.” John thinks I’m obnoxious and a “princess” who spends too much at Starbucks—and still he loves me.

I love him too. He is genuinely good. He sees the best in everyone—well, there’s this one guy at work who really gets his goat, but beyond that… At movies, John cries so hard he has to take off his glasses and wipe his eyes with a hankie. Yes, he’s the kind of man who always has a clean handkerchief in his back pocket and a box of Kleenex in his truck. If you’re hormonal, he’s ready.

Two months ago, John found blood in his urine. He has cancer. Bladder cancer. No. Yes. No. I remember the moment he told me. He’d gone to the doctor—we were sure it was nothing. I was in the living room sweeping up dog hair. It was close to Halloween. All the grass was dead and the pumpkins glowed in the late afternoon sun. My phone buzzed. It was John: “Are you sitting down?”

It was bad news. The sitting down kind of news.

We’re still in the “ignore it” stage. John feels healthy and acts healthy, so how could anything be wrong? We rarely talk about it. We still fight. I bitch and complain. He’s negative. Nobody’s drinking kale smoothies, or flying to Mexico for alternative treatments, or visualizing the bladder full of orange, healing light. Well, I am—the visualization part—but how is that going to help John when he thinks it’s “a bunch of horseshit?”

We ignore the elephant—no, the giant capybara—in the room. John will be fine. John will be fine. Johnwillbefine. The truth is, I’m afraid we’re at the beginning of a long journey that won’t end well. But, when you think about it…isn’t that life?

I closed my eyes. I quit thinking altogether.

Matt called me into his room. He’d taught himself to play “Wish You Were Here.” There were a few false starts. “Check it out, Mom. Strum, strum, FUCK! OK, check it out. Strum, strum, SHIT!” Then he got it and it was good. Natalia and I applauded.

“And I’m not smoking.” Matt set down his guitar. “It’s been like almost a month.”

“Yay,” I said, purposely not correcting his math.

He gave me a wistful look. “Will you please bring me some water? And make no-bake cookies?”

˜

A giant capybara stands—sits? It’s hard to tell; they’re all shaped like pears—under an outdoor bamboo shower. Hot water drips onto its head. It closes its eyes, blissful.

I keep looking for the rub. Is the hot springs a ruse? Is this how the capybaras are rounded up before being led to slaughter? Do relaxed capybaras make for more tender meat? Do people eat capybaras? I shudder, remembering the time my daughter googled guinea pig and was greeted with an image of two: braised and on a plate, ready for dinner.

Are these jumbo rodents as peaceful as they seem? Or do they fight to the death when the cameras are off?

Who are these capybaras, and why am I too lazy to Google any information about them? Giant, happy rodents bathe on my computer screen. I don’t want to know more. It’s the mystery I love.

A big one—the size of an English bulldog—sleeps, two mini ones curled at its rump. I watch it breathe, in an out, so slowly, as it dreams its scritchy dreams. I notice a grasshopper on its back. It darts. Shit, it’s a snake, no a lizard! I wasn’t expecting that. The reptile slithers into the grass. The capybara twitches in its sleep.

Another one goes underwater—the sides of the tub are glass—and just sort of walks around. It moves blindly, eyes closed, like an old person in a pool. I wonder again if they bite. I’m reminded of a story. Gerbils. Giant gerbils. Little gerbils. Oh, how I wanted gerbils.

˜

I’m nine and I’ve read the book and I’m ready to be a full-fledged gerbil owner. A responsible gerbil owner. I actually wanted the Teddy Bear Hamster, by my mom said no. Anything too cute is immediately denied. There’s a limit to cuteness in our house. No Pulse or Lawman jeans, only the itchier J.C. Penney brand. No salon haircuts. My mom gives me and my siblings—and several of the kids on the block—identical choppy bowl cuts. A thirty-second sit down in Judy’s living room, and you’re good to go, ready to fly back outside and play Red Rover or doorbell ditch or watch Shirley swing the dead possum by its tail, or whatever it was you were doing before your mom told you to go inside and get those goddamn bangs out of your eyes.

The Gerbil Story

I am nine, in my bedroom on 31st street with my best friend Kelly. I’ve finally wangled gerbils—which is ironic, as for the rest of my life I’ll have a severe rodent phobia. But I’ve got my gerbils, happily gerbil-ing in their fluff in their cage like a birdcage, and life is complete.

Kelly and I are holding the gerbils. They are scary-fun—the best kind of fun. I can still feel the thrill in my belly, the gerbil in my hand—ugh!—scampering up my arm, up to my neck, its sharp claws poking my skin, the whiff-whiff of its breath against my neck, the naked tail—argh!—its breathing, so fast and birdlike, what if it goes in my ear?! And then—

Kelly screams. She’s still holding her gerbil, but her hazel eyes have grown enormous, for it has bitten her thumb. The gerbil’s bitten Kelly and she’s screaming. I see bright ruby blood, the brightest, reddest blood I’ve ever seen, welling jewel-like from her thumb, and the gerbil is still attached. I can’t believe it. “Get it off, get it off,” Kelly shouts, panicked, and now she’s getting really pale, all the blood draining from her face, out of her thumb, blood dripping on the hardwood floor, the gerbil gripped, chomped down permanently and forever to her thumb, its little body flinging back and forth as she tries to shake it off, its beady eyes bright, determined to never let go of my friend.

I call for my mom. Kelly keeps trying to shake the gerbil off—why won’t it let go?—and now I’m crying and scared, what if it never lets go, what if it bites Kelly forever? And then—WHAP. The gerbil flies across the room and hits the wall on my little sister’s side with a loud THUMP, then slides to the ground and lies there. Unmoving.

Oh. My. God. Kelly’s hurt, and we’ve hurt the gerbil, slumped against the wall, stunned and motionless. Is it dead, is it dead? Blood dripping, blood smeared on the gerbil’s chest, and I’m crying. Suddenly, I no longer like this gerbil business, and I yell once more for my mom who comes running as I collapse to the ground, hands on my head in a duck and cover position. I hate them, I hate them. This is really, really bad, make it go away.

I was a highly emotional child.

My mom picks up the gerbil. She rubs its bloody head. It blinks. It’s alive. We put both gerbils back in the cage (for I was gripping my gerbil the entire time). “Now it’s time to calm down,” my mom says, hands on hips. I wipe my nose on my shirt. I recover. Kelly is bandaged 1970s style: no trip to the doctor, no antibiotic ointment, no rabies shot—she has a giant rodent gash on her thumb, but my mom just runs cold water on it, slaps on a Band-Aid, and we go outside and play.

˜

There’s more.

The Gerbil Story, Part Two

The next day I walk to the cage, full of trepidation, no longer excited about these gerbils of mine. With power, the owning of pet rodents, comes great responsibility, and it weighs heavily on my nine-year-old shoulders. I watch the gerbils. One of them is doing its gerbil thing, shredding up a toilet paper roll, its black eyes starbright and alert, and the other…isn’t moving. I poke it. Its head falls off. Yeah, you heard me: The second gerbil’s HEAD FALLS OFF. The alert gerbil, the gerbil with the intact head and the curious starbright eyes, which I now realize are pure evil, has eaten his cagemate. He’s eaten his friend, chewed its head almost all the way off. And when I poke said friend, fluff falls away from the carcass and the head plops to the bottom of the cage.

I yell for my mom.

“Ooh, ick,” is her response. She sets down her coffee cup. “Go get me some toilet paper.” She hesitates, a grim look on her face. “No, go get your dad.”

A sick horror seeps into my veins. Once the dad is called in, you know it’s really bad.

My mom tells me to “quit fussing” and go wait in the hall. As I crouch outside my bedroom door, the linoleum cold on my bare feet, I devise a story in my mind: The evil gerbil with the starbright eyes is the one that bit Kelly, the one that got FWAPPED against the wall on my little sister’s side of the room. He was so traumatized by his flight through the airspace of Kimmy and Krissy’s room that once safely back in his cage, he proceeded to eat his cagemate, his lady friend.

Now, I have no idea if those gerbils of mine are male or female, but I instinctively think of the bad one as the man and the cannibalized one as the lady.

˜

Gerbils: Day Three

I tiptoe to the cage, sick in my gut. I really hate gerbils now. Maybe I shouldn’t look. Maybe I should go back downstairs and watch cartoons. If I ignore the remaining gerbil, will it go away? Well, yes, eventually. But no, I’m the responsible gerbil owner. I read the book. It’s my duty to change its water, feed it and clean its cage.

I force myself to look.

The remaining gerbil is no longer alert, curious, doing his gerbil thing. He is unmoving. My heart explodes. I shut my eyes tightly, reach out a tentative finger, and give him a poke. He doesn’t move. I open my eyes, too afraid to poke him again. Either way, he doesn’t move.

For the third time in three days, I yell for my mom.

She thumps up the stairs, sets down her coffee cup with a sigh, and pokes the probably dead gerbil. She pokes it again. After one final vigorous poke, she pronounces it dead.

This is it. The great gerbil experiment of 1974 is over. Done. I don’t know if I’m more horrified or relieved.

As my mom takes the cage way, saying, “Well, this was a waste of money,” I look at my hands, my fingers pinched together from the stress of the entire episode. I hate gerbils, I tell myself. I hate them, I hate them. At the same time, I’m heartbroken. Why did my gerbils not turn out right? Why did my gerbils go so awry? Why did I get the bad gerbils? Why, why, why?

I tumble back through time. The wanting, the years of wanting, and the book with the illustration of the perfect Teddy Bear Hamster—the right kind, Mom! The kind I wanted in the first place. The kind that doesn’t eat its friends. But no, it was too cute, and there could never be anything too cute in our house. We only ever got vanilla ice cream. Why? Because it was plain, and anything else would be too fancy.

The yearning, the whining, the begging, the pleading, the book with the picture in it, with the instructions that I read, that I memorized—The responsible gerbil owner will change the water daily. The responsible gerbil owner will provide a wheel for their pet. Gerbils want and need daily exercise. Watch them go for a ride!—and then the trip to the pet store up on Woodstock, the gerbils, two gerbils because two are always better than one. The two gerbils in a box—gerbils in a box, gerbils in a box, the thump-scritchy-thump of gerbils in a box—and the cage, the cheaper one like a birdcage, gold—it was so pretty—but was it a gerbil cage? Was it actually a birdcage? Was that why the bloody mayhem occurred, because the cage was too small? Even now, forty years later, I have so many questions.

˜

I now realize that when I watch the capybaras, I’m not in a state of relaxation, I’m in a state of hypervigilance. Look at them simmering in their fancy outdoor hot tubs like wannabe actors in a Burbank apartment complex. They lean against each other, close their eyes, relax their bodies, sink down until just their tiny ears are visible. So Zen, so laid back, so…dangerous.

Do they eat each other once darkness falls? Do they sink their teeth into the hands of unsuspecting tourist/belly rubbers? Are they lovers or killers? Madmen or just really chill spa guests? That’s the rub: I have no way of knowing (well, I could Google, but as I said, I’m too lazy). And while I love the mystery of the capybaras, I don’t trust them, not one bit. Who’s to say they won’t wreak havoc on this snowy, steamy Japanese resort town? How can I believe what’s right in front of my eyes?

When you think about it, that’s the problem with life, too—the rub, the tricky part. Are things as they appear—happy capys getting their hot tub on—or are there deeper, darker developments to come? Is it nothing, or is it something? Oh, mystery of life: how amazing, and how truly terrifying you are.

Will Matt stay “off the nip” and have a happy, productive life, spinning on his own mortgaged gerbil wheel with good-citizen determination? Will John’s high-grade cancer cells do the right thing and dissolve in their weekly bath of tuberculosis bacteria? Or will they grow angry and destroy a genuinely good man? And what about the spots on my bathroom wall? What the hell are those? Nothing? Or something?

I guess my only choice (for I’d rather be dead than bitter and jaded) is to force myself to see the good, to believe in the good: Matt, twenty-one already, and yes, he’s in my home, eating my food and running up my water bill, but at the same time, yes, it’s Matt, alive, my big boy, right here in my home. And John, the gerbil I always wanted—no, the Teddy Bear Hamster—the good kind, the right kind, the kind that sticks around. And here he is, sitting beside me in a movie theater on a rainy Sunday afternoon, big and warm and comforting, weeping into his hankie.

Back at my desk, I stare at my computer screen, wondering if my university has some sort of system to spy on us, to watch what we do all day long in our locked offices when we’re supposed to be grading papers. Do they know I’m obsessed with the capybara videos? Is there some sort of limit to how many times you can refresh cuteoverload.com before they knock on your door, hand you a pink slip, escort you off the property, and send out a university-wide email telling everyone you’ve decided to “spend more time with your family?”

Fuck it. I throw caution to the wind. I press play, lean back, and watch, mesmerized, as fat, happy animals float in their lemon baths, enjoying themselves, in the moment. Breathing. At peace. Alive.

September 27, 2015

X-Ray

Here’s an excerpt from the novel I’m working on. Daisy is the mother of three teens. Her husband is in prison for murder, and she’s struggling with PTSD. When I wrote this section, it felt good to get in touch with my inner wild child. Growing up in Portland, in the 70s, in Eastmoreland, was, in a lot of ways, a free and happy time. I loved the tunnels of old oaks, and the cold Jell-O air, and all the awesome kids in our Duniway crew!

X-Ray

The story of that night could be summed up in two lines: “Life had flipped. This was the X-ray.” The Daisy she had been up until that moment disappeared. Someone new took her place, someone fearful and disappointed in the world, and over the years that fear and disappointment had grown. She looked at the text her friend, Janie, had sent after their brunch.

This isn’t you. You have never been depressed a day in your life. When I saw you walking to the restaurant, you looked scared. This is NOT THE DAISY I KNOW. The Amazing Daisy was never afraid. Sometimes you were so fearless I WAS SCARED! Like in eighth grade when you and Lindy Watson took your mom’s car to go buy beer and you had never driven in your life and it was a stick shift! That was it for me. I couldn’t keep up, LOL. Please, from someone who loves you, go see someone, get on medication—there is a lot of help out there. You deserve to BE HAPPY!

Janie’s text was painful. Daisy had sensed she was losing her mojo, but she hadn’t thought anyone would notice. Janie had, and Daisy was embarrassed. She had let the world down. She was no longer the fun girl screaming with laughter as her mother’s Pinto bucked and jerked and squealed its way through the intersection of 26th and Holgate, a short case of Mickey’s Big Mouth hidden beneath a sweatshirt on the back seat.

Where had she and Lindy of the goopy blue eyeliner found the money to buy beer? Oh, yes. Daisy had a distinct memory of tiptoeing into her little sister’s darkened bedroom, opening the jewelry box, and extricating two folded two-dollar bills, the ballerina unmoving, oblivious.

Mickey’s Malt Liquor. Daisy’s mouth watered, and she felt ill just thinking of that green hillbilly in a bottle. The same went for sloe gin—whatever that was—and she knew that if she wanted to make her little sister nauseous, she need only say two words: peach brandy.

Back to the story. The deeper truth was that the real Daisy, The Amazing Daisy, her nickname when she was at her wildest, took risks. She and Lindy wanted beer. They were only thirteen. What to do? Take those two-dollar bills that had been sitting in Heather’s jewelry box since 1976. And while you’re at it, take the pink rabbit’s foot, too—she’ll never notice. (Only she did, Daisy remembered—the very next morning. “Somebody robbed me,” Heather screamed from her room, and Daisy had run straight out the front door, the rabbit’s foot swinging from her belt loop—a blatant admission of guilt, she saw now—not stopping until she reached the playground at school, which was empty but for a dog chasing seagulls on the field.)

Back to the night before. After procuring funds, which included raiding her mom’s boyfriend’s hippie pouch for quarters—Daisy and Lindy huddled. Now that they had money, how to get to Penny Wise, the store that was happy to sell to minors, its unofficial motto being, “If you have money, we have beer”?

“Let’s take the car,” Daisy said. “Everyone is somewhere. They might not be back until late. Really late.”

“Cool.” Lindy smiled her rabbity smile, and Daisy had the urge to smush her chubby cheeks. “Do you know how to drive?”

“No. Do you?”

“No.”

“We’ll figure it out,” Daisy said, feeling crafty. “It can’t be hard. My mom just puts the key in and goes.”

“Yeah, my mom too.”

“I like the purple kohl on your lips.” Daisy grabbed a stack of Oreos.

Lindy held out her hand for a cookie. “It looks good on you, too.”

“Yeah, I know. We’re in a club, OK? The purple fox club. No one else is allowed in.”

“Purple fox.” Lindy bobbed her head. “Hell, yeah.”

“And our theme song is `Mary Jane.’”

“I’m so in love with Rick James. What if we took the car and met a guy with glittery braids?”

“Two guys,” Daisy said. “And I would die.”

*

Driving was surprisingly difficult. Who knew that keeping the wood-paneled Pinto in a straight line would be so hard? Between the gas and the brake and the other brake and the really-hard-to-turn steering wheel, driving was like a test you wish you would have skipped.

The car bounced up onto the curb behind the 7-11. The girls bounced with it, hitting their heads on the ceiling. Lindy screamed. Daisy laughed, tears burning her eyes. “Why are there so many mugs in this car?” Lindy cried.

“I don’t know, my mom—”

“What?!”

Daisy was laughing so hard she couldn’t speak.

Coffee mugs chinging everywhere. Strange needles and meters on the dashboard. A possum waddling through the pooled headlights. It was like that: Daisy would act tough and, instantly, the tough part would take over and she’d have no choice but to go along, which wasn’t bad because the end result was always fun.

It would be years until the fun stopped, as abruptly as the Pinto did when Daisy turned onto 31st street and saw a car in the driveway.

*

The Pinto screeched to a halt. Crybaby Bob’s VW Bug sat in the driveway, and it was like him, Daisy thought, burned out and silly with its painted flowers and peace signs and psychedelic swirls. The driver’s door was smashed, and you had to get in on the passenger side. When the neighbor lady hit Bob last summer, he’d come home and cried on the couch for an hour.

“Nothing I do…” he kept saying.

“You do. You do do. You do a lot,” her mother murmured, and Daisy, listening in the kitchen, had smiled because nothing they said made sense.

“Maybe…” Her mom’s voice was hesitant. “Try not to smoke before you go out.”

“Carol,” Bob warned.

Daisy giggled and ran outside and down the block to go get Lindy.

Bob was boyfriend number three after Daisy’s dad moved to Japan, never to be heard from again.

“He’s there on business,” Daisy’s mom said, stink waves emanating from the home perm on her head.

“Is he coming home?”

“He needs his space.”

“Clear across the ocean?”

“Head space—he needs to clear his head.”

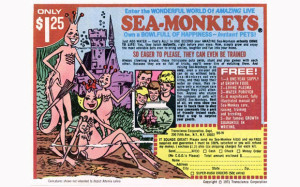

“What’s wrong with his head?” Daisy cried. But Carol had no answer—it was time to neutralize, to take out the rods—so Daisy gave up. She sometimes pictured her dad on the other side of the ocean with a new Japanese family, like his old one only smarter and more streamlined, and there he was, Marvin, for that was his name, with his big square head and square black glasses, smiling proudly like the dad in the ad for Sea Monkeys.

After her obsession with Squirmles, little squirmy things on a string, Daisy had become obsessed with Sea Monkeys, and after seven years of begging, her mother finally let her order them from the back of an Archies comic book.

Sea Monkeys were a hoax.

They were not a happy family with crowns and pretty blonde hair, relaxing in a bowl, smiling at you through the glass.

They were bits of nothing and they didn’t do anything and you could barely even see them, and one day the dog drank them up and that was it.

Done.

They were like us, Daisy had thought as she dropped the bowl in the outside garbage, and no, she did not want to make a terrarium, Mom. Daisy and her mother and Heather—they were the lame Sea Monkey family, the dirty duck pond water family, the ones her dad had left behind, and who could blame him for wanting to go far away, to find people who were nicer and calmer and didn’t yell and throw coffee mugs (Daisy’s mom) or refuse to go to bed (Daisy) or have vampire teeth that cost a fortune in braces (Daisy and Heather) or throw up candy corn in the backseat of the company car (Daisy).

Marvin gave the girls the two-dollar bills the day he left. When Daisy stole them from Heather’s jewelry box, she’d thought, “Good, get rid of them all; there shall be no two-dollar bills in this house.”

Now they had beer instead. Only Bob’s VW Bug was in the driveway, which meant her mother was home, which meant trouble.

“Act normal,” Daisy whispered.

“Bob’s going to cry,” Lindy said.

Daisy tried to park straight then gave up. They pushed the car doors shut, shoved the beer in the bushes, and walked inside.

Bob was waiting on the landing.

*

Why? Daisy wanted to shout. Bare feet and hairy toes and cut-off shorts that were always way too short and a T-shirt for some gross concert she would never be caught dead at—why was this weirdo living in her house? And hadn’t he ever heard of funk? The Dazz Band and Parliament/Funkadelic and the Commodores and Earth, Wind & Fire and everything that was good and not embarrassing? Bob had a ponytail. He smelled like a fancy goat. Instead of deodorant, he wore some kind of oil that he kept in a velvet pouch on top of the dresser—frankincense—Daisy had found it during one of her sweeps for money and roaches. “He’s one of the Wise Men,” she told Lindy, and they’d laughed a long time, probably because they’d stolen one of Bob’s roaches from the edge of the bathtub earlier.

He took baths. Guys should not take baths. It was just wrong.

“Where’s my mom?” she asked now.

“Where is your mother’s car?” Bob had a gleam in his eye, and Daisy could see how excited he was to get her in trouble—there was nothing he liked more than to be a narc. “Who ate all the Fudgsicles?” her mom might ask, and Bob would be the first to pipe up. “Well, your daughter left four sticks next to the TV, and they’re sitting there as we speak, covered in ants.”

That time was good, though, because he got in trouble for not cleaning up.

Bob repeated his question. “Where is your mother’s car?”

Daisy kept her face expressionless. “I don’t know—outside?”

“Where have you girls been?”

“Outside.” Daisy said it like he was stupid.

Bob’s eyes widened. “It’s your tone,” he said, shaking his head. “It—no, I feel that when you use that tone, it’s—I hate to say it—really bitchy. It makes me feel sad, Daisy, and I’m just trying to hang in there, like you and everyone else on this big blue ball we call home.”

Lindy, breathing steadily in Daisy’s ear, snickered softly at the word ball.

Daisy thought of the poster in her bedroom, the kitten doing a chin-up on a bar and beneath it the words HANG IN THERE. She looked at Bob’s skinny noodle arms. He probably couldn’t do a pull-up, and she was the arm-hang champion of her school—she had the Presidential Physical Fitness patch in her jewelry box to prove it. “Did you just call me a bitch?” she asked.

Bob looked scared. “No, man. I’m just confirming. You were outside with the car.”

“If the car was outside, and we were outside, then I guess so.” Daisy shrugged.

“Shall I touch the hood?” Bob’s tone was oddly formal.

“What?”

“Shall I touch the hood?”

Lindy giggled, and Daisy tried not to laugh.

“To see if it’s warm,” Bob explained.

The girls laughed harder.

Bob sighed and shook his head. “Just keep it down, OK? Your mom has cramps, and I’m feeling really vulnerable lately…” He wandered downstairs to the garage, where he smoked pot and listened to Steely Dan records. He wasn’t allowed to smoke in the house because of the girls, but guess what mom, the garage is part of the house, and it’s not like we can’t smell it.

“He sure feels a lot,” Lindy said as they retrieved the beer from the bushes, fumbling in the dark.

“He’s like a lady but not.” Daisy hesitated. “Hey, let’s go knock on bedroom windows.”

“Awesome.”

“We’ll start with Greg then go to D.C.’s. We’ll scare the guys and make them come with us.”

“And then we’ll party in your room. So much fun.”

As Daisy walked past the Pinto, she rested her hand on the hood. It was warm, as if still excited by their late night joyride.

September 8, 2015

Summer School

I don’t think I was the best mom to my oldest son—we were like two teenagers (or one hormonal teen and one perimenopausal mom) battling—but he survived and is now a wonderful and wise twenty-one year old. Through the harrowing high school years, I learned a lot about parenting and my son and myself and terror and worry and joy, and am now a much better mom to my current teenagers. Or maybe it’s that they’re very well-behaved (or very sneaky) and so it’s easy. I’m just glad to be a mom, and to have some good material for the book I’m currently working on. There is no school for parenting, and if there were, I would have flunked out and been sent to summer school repeatedly. Here’s an excerpt from the new book.

“WHAT?!” Lil Jon

“Let me get a Monster,” Matt said, his sunglasses reflecting twin pine trees.

“No. Ick. We’ll go to Starbucks.” His mother, Daisy, glanced at him as she turned onto Fremont. “You look like a rock star in those.”

“I am a rock star.”

As they stood in line at the coffee shop, Daisy was surprised at how tall he’d grown—at least six inches in the past year—she barely came up to his shoulder. It seemed just yesterday he was a toddler, clinging to her like an entitled chimp, refusing to walk when he could be transported. Now, at fifteen, Matt was a young man: long black hair, pale skin, black-rimmed eyes. He was shockingly handsome and as wild and out of control as she’d been as a teen. A pierced eyebrow, a pierced lip, gauged earlobes—these no longer fazed Daisy. She’d fought the battle of the piercings and lost long ago. Today, there were more serious issues at hand. They were on their way to Matt’s summer school class. He’d been suspended twice his freshman year for smoking pot, then expelled for pulling the fire alarm during finals week, and had earned zero credits.

A short latte and a six-dollar soy white chocolate mocha later, and they were on their way. Baskets of fuchsias hung from the streetlamps, and a frazzled terrier sat on a table, staring into the shop at its owner. They walked to the car beneath a sky as blue as swimming pool water. Sunlight streamed through the windshield, clean for once, and sparkled on the hood. Matt, dressed in sagging cargo shorts and a Misfits T-shirt, was in a good mood. “Man, summer school’s legit. Nobody hassles you. They don’t even care if you smoke.”

Please do not smoke, Daisy thought, biting her tongue to avoid the fight. “And you go,” she said. “You’ve gone every day.”

“Right. Because nobody cares.”

“So it’s the caring that makes you want to…act out,” she began.

“Don’t be so dramatic. You analyze every single thing.”

“But—”

“FORGET IT.” Matt plugged in his I-pod and blasted one of the nastier rap songs she’d heard in a while, something about “chapped dicks” and “dentists” with “erections like injections” and, oddly, “Chloraseptic.” Judging from the chorus, the title seemed to be “Put it in Ya Mouth.”

Charming.

Things devolved from there.

Trick Daddy’s “Let’s Go” blasted on the stereo, a song so awesomely aggressive it made Daisy want to run down the street and kick over recycling bins. As she committed criminal mischief in her mind, she followed the curve of 21st to Sandy Blvd., careful to avoid the cyclists in the bike lane. Before she knew what was happening, her son was hanging out his window, cursing and flipping off a bike rider behind them. “Matt, no,” she cried.

Too late. He continued to yell.

“Why did you do that?” she said when he sat back down.

“He punched our car.”

“No, he didn’t.”

“Yes, he did—you cut him off.”

“No, I didn’t. I’m always careful around bikes.”

Shit. The stoplight on Sandy turned yellow then red. “Goddammit, Matt. Here he comes.” She watched in the mirror as the bike rider pulled up beside them and started to punch the window. Oh my God. Daisy tried to reach her phone in the backseat, but her seatbelt had locked. She unhooked it but still couldn’t reach the phone. What was she going to do, dial 911 and report a rabid hipster attack? She honked the horn, long and loud. The driver beside her, a man in a business suit, looked at her but did nothing. It all happened so fast. Matt rolled down his window and the biker, skinny and red-faced, with purple tape on his handlebars, reached into the car and tried to grab him. Daisy screamed. Matt opened his door, knocking the guy backward, and threw his coffee on him. “You better back the fuck up,” he yelled. The light changed. The biker rode off. Daisy drove straight—she’d go the long way just to get away from this maniac. Which maniac, the biker or her son? She couldn’t quit shaking. “Why did you do that? You don’t mess with people. You don’t know what kind of crazies are out there. You could get shot. It happens all the time.”

Matt was pumped. On fire. Cheeks flushed, green eyes bright—it was the most animated she’d seen him since puberty. She could practically smell the testosterone radiating off his body. “What a pussy. That’s right. Mess with me and get your ass beat.” He said the last part like a rapper, the word “beat” rising in a mocking tone.

“Never do something like that,” she cried. “I don’t want to die because you’re trying to be a macho man.” Tears burned her eyes. She’d thought for sure the guy was going to pull out a gun and shoot Matt—or her—as they sat in the car, stuck in Portland traffic.

“Macho man.” Matt laughed. “Would you rather have a macho man or a bitch for a son?”

Daisy didn’t answer.

“You’re fear based,” he said when he got out of the car at school. He shook his head, disgusted. “You live your life in fear. You may as well be dead.”

“Thank you for the advice. I’ll take it into consideration.”

He lingered at the window, and when he spoke again, his voice was soft. “You know, just because someone goes crazy and shoots a person doesn’t mean it’s going to happen every single damn day.”

Daisy wiped her eyes.

“Love you, Mom.” Matt reached out and patted her shoulder, awkward like a dad.

Daisy sighed. “Love you too.” She watched as he jumped on his skateboard and coasted down the sidewalk, tall and laid back, long hair streaming behind him, king of his teenage world. God, how she’d love to feel that way again: invincible, insane and alive. Matt stopped at a group of kids smoking on the corner and kicked his skateboard neatly into his hand. As she pulled into traffic, his words echoed in her mind. You may as well be dead. He had a point.

Clouds like bruised orchids bloomed over the Pearl. After brunch with a friend, shopping on Hawthorne, and a lunchtime hookup with her sort-of-boyfriend John, Daisy was in a much better mood. She drove with the windows open, down Lovejoy and across the Broadway Bridge, the weird trolley tracks bumping beneath her tires. She found the tracks, which had appeared out of nowhere, troublesome. Were you supposed to drive on them? Was a trolley going to suddenly come flying her way? Could she get electrocuted?

“Rio” played on the oldies station. “Hey now, whooo,” she sang, tossing her sweater in the back. She’d just changed lanes, out of the trouble zone, when Matt texted:

Daisy called him on speakerphone. “You have to be exactly where you say you are. I’ll look once, and if you’re not there, I’m going to keep going. David and Opal have Junior Lifeguard at one.”

“Whatever. Why are you being rude?”

Daisy didn’t answer. She’d gone on way too many wild-Matt-chases to trust him.