Stephen H. Provost's Blog

May 7, 2024

"The Watchers" riddled with loose ends, inconsistencies

The Watchers is another entry in what I call the sensory-deprivation horror subgenre, following Bird Box and A Quiet Place.

The former deals with creatures that drive you mad if you see them, while the latter focuses on the sense of hearing: If you make a sound, it will alert the monsters, with tragic consequences.

A.M. Shine’s The Watchers (the basis of a film by the same name starring Dakota Fanning to be released June 7) is a little different. You don’t know what the watchers look like. You can’t see them, but they can see you. It’s an intriguing premise, and one that obviously caught the eye of filmmakers, who are about to release a feature film based on the book. But the potential for a suspense-filled, edge-of-your-seat tale is undermined by the story’s erratic pacing and unanswered questions.

I enjoy action and narratives that propel a story forward, and there’s too little of each here for my taste.

Shine likes to build tension through detailed description and by getting inside his characters’ minds—methods that can be keep readers engaged if they’re woven into the framework of the story and essential to the plot. But if they bog the story down rather than moving it forward, they can have the opposite effect.

I’ll start with description.

In his descriptive passages (and there are plenty) Shine leans very heavily on similes: Out of curiosity, I searched my Kindle copy for the word “like,” and it came back with 559 hits. Through the first couple of chapters, the vast majority I counted were used in similes. Every author has a crutch or two or three. Some writers begin far too many sentences with prepositions. Others have favorite words. That’s all well and good, but when the reader starts to notice every time a writer relies on that crutch, it’s a good sign it’s being leaned on too heavily.

More frustrating to me, however, is that much of Shine’s description is superfluous: It doesn’t tell us anything important about the story, but seems to have been included for the sake of drawing mental pictures for the reader. That’s fine if it tells me something important; if it doesn’t, it just slows me down.

Shine bogs the story down even further with extended sojourns inside the characters’ heads. These too seldom involve new revelations about them or their situation. Rather, they tend to devolve into repetitive ruminations about how they relate to one another.

I’ll grant that there’s only so much you can do when your characters spend most of the novel trapped in a cubicle together in a dark forest. There’s going to be a sense of claustrophobia and people getting on one another’s nerves. But the characters aren’t completely trapped: They can venture outside the cubicle during daylight. Yet Shine devotes precious little of his narrative to alternative settings. In one particularly galling case, the main protagonist (Mina) seems on the verge of discovering something important about the forest environment—a pattern to the burrows. But Shine distracts us from this impending discovery by having her delve back into analyzing her three companions.

Even worse: The characters never use the pattern she discovered to actually do anything about their situation. It’s simply a dead end.

And the characters are so thoroughly stuck in their heads that, even when they find themselves in a life-or-death struggle where time is of the essence, Shine has them spend a lot of time speculating on what their lives will be like when they escape. That’s just not how most people react to extreme danger. In a realistic narrative, the characters wouldn’t be focused on what-if’s about a possible future. They’d be consumed with making sure they had a future—any kind of future—by surviving in the here and now.

MAJOR SPOILERS AHEADUntil now, I’ve confined my critique to general points, but from this point forward, I’ll be dealing with elements of Shine’s story that are very specific. So if you don’t want to know what happens, by all means, please stop reading here.

His premise is that a few individuals have driven down a road and into a forest where their cars break down and smartphones stop working. In fact, nothing electronic works. Cut off from the outside world, they become sitting ducks for a race of creatures that dwell in the forest, intent on “watching” them and killing them if they don’t cooperate; perhaps even if they do.

We aren’t told why the electronics stop working; we are merely asked to accept it. Are the monsters in the forest responsible, and if so, how? Is the forest itself a “dead zone”? We’re never told.

We are also asked to accept, later in the story, that a history professor has set up computers and surveillance cameras deep in the forest that mysteriously do work. There’s no explanation for why that’s the case, either.

In crafting his narrative, Shine tries to blend together two distinct kinds of story: In the first, the creatures appear to be mindless, ravenous monsters that salivate over the prospect of killing their prey if they venture out of their protective “coop” at night. But they’re also portrayed as watching (and studying) their captives, because they have the ability to mimic a human’s appearance and are, it seems, trying to perfect this ability so they can become undetectable.

This ability seems like nearly an afterthought through much of the book. Yet near the end, it comes suddenly to the fore when we find out, in the very last sentence, that some of the creatures have become so adept at mimicry that they have infiltrated human society. To what purpose? We’re never told. Do they want to use the element of surprise to catch and kill human prey? Do they want to become more human themselves? Do they want to take over the world?

If Shine’s just trying to set up a sequel, he’s certainly left enough loose ends to set one up.

Indeed, for all the time Shine spends inside his characters’ heads (and on an extended section of exposition near they end), he leaves a host of questions unanswered in terms of their motivation.

The history professor, whose wife passed away a few years earlier, came to the forest to conduct research on the creatures and used hired help to construct an observation center. He brought with him a photograph of his wife, which one of the creatures—one capable of surviving during daylight—used as a basis to mimic her appearance. She even takes the dead woman’s name, “Madeline,” and sets up residence inside the observation center, or “coop,” either during or following the professor’s departure.

The relationship between the professor and the creature is never explored. At one point, the author states that he actually constructed the “coop” as a home for the creature, but this is at odds with the idea, suggested elsewhere, that he built it as an observation center. And why the creature should need a home outside the burrows where her fellow creatures dwell is never explained, either. Is she in league with them, or is she an outcast because she’s different? And why is she different?

The loose ends just get looser.

The professor is, if anything, even more of an enigma than “Madeline.” He only appears in the story via a videotape that he’s left in a bunker beneath the coop, wherein he provides the captives with a means of escape and implores them to destroy all his research on the creatures back at the college.

The captives readily agree to this request, but their unquestioning assent makes no sense. They’re supposedly worried that, if others learn about the creatures, they’ll come to the forest to seek them out. The author states this explicitly, yet this idea left me scratching my head. Who goes to a dark forest looking for a monster? Wouldn’t it make far more sense to alert others to the danger so they could avoid it, especially since the captives themselves had been trapped in the forest because they themselves hadn’t known of the danger?

If there’s a road into the forest, where these creatures are said to have lived for centuries, that would seem to indicate that hundreds of people must have already wandered into the trap. The idea that they had lived there for centuries and their presence was still a mystery stretches credulity beyond the breaking point. The author wants us to accept that large numbers of people have disappeared over centuries and no one has bothered to investigate?

Maybe medieval humans had done so… and had simply gone missing themselves. But in the modern world, when people disappear, the authorities get involved. They look for patterns. If their investigations produce further disappearances, they redouble their efforts. In a case like this, when things got bad enough, the government would have called in SWAT teams and military units, dropped bunker-busting bombs on the creatures’ burrows, or burned down the forest. They would have done something to eliminate the threat.

None of this is even suggested.

Nor do we know what happened to the professor after he made the tape. If he killed himself, no body is ever discovered. If he allowed himself to be taken by the creatures, the author never says so, let alone explains why he would have simply given up. He was well protected and had ample supplies inside the bunker. He stated that he was too badly injured to take the escape route he reveals on the video, but why not wait and hope the injury heals? None of this is ever addressed.

The professor’s relationship to the creature “Madeline” is never explained, either. If he was kindly disposed toward her, was it because she provided some sense of solace by taking on the appearance of his wife, as on “The Man Trap” episode of Star Trek? Or was he simply afraid of her?

And what was her attitude toward him? It’s never stated and hard to discern from the story, which presents “Madeline” as both unforgiving and surprisingly helpful to the humans in the coop. They never quite know what to make of her. She assists them in escaping the forest, perhaps, the author suggests, because she’s learned all she needs to about how to mimic them. But why does she leave them alive once they’ve served their purpose?

Her attitude toward her fellow creatures is similarly ambiguous. She protects the captives from them, and even warns Mina about them in the end, yet she also is intent on protecting them by insisting that Mina go to the university and destroy the history professor’s research; even threatening her life if she fails to keep it secret. This leaves open the question of why “Madeline”—who by now has learned how to mimic Mina’s appearance—didn’t steal the files from the university and destroy them herself.

If the author would have only let us inside “Madeline’s” head the way he let us see the thoughts of the other characters, we might have learned the reason(s) for this ambiguity, but he doesn’t do us that courtesy.

At the end, “Madeline” suddenly discovers that she isn’t the only one of her kind (with the ability to accurately mimic humans and survive daylight). It’s weird that she didn’t know this earlier, especially in light of her apparent familiarity with the creatures and how they operate. Not surprisingly, we never get an explanation for this, either.

It’s just another loose ends in a frayed tapestry of a story that could have been a whole lot better.

One final issue I had with this book was the number of errors I found. I am not one to hold authors’ feet to the fire for the occasional typo. Everyone makes mistakes, and not every author can afford a first-rate editor. However, I do have a problem with errors that appear in books successful enough to be adapted into motion pictures.

For instance, a sentence in Chapter 9 reads that “the woman’s poise was not one of action.” I’m sure “pose” was meant here. The very first sentence of Chapter 7 begins “Daniel was sat…” Oops. And then there’s, “Daniel came to believing” (rather than “to believe”), in the same chapter.

If this book was published by a traditional house, its editors and proofreaders did a piss-poor job of catching typos. If it was published independently, the author has had enough time to fix it (considering the book was published in 2022) and certainly has the wherewithal to go back and do so.

My only question now: In this rare case, will the movie actually be better than the book?

Stephen H. Provost has more than 30 years of experience as an editor and is the author of more than 50 books, including the horror collections Nightmare’s Eve and, with Sharon Marie Provost, Christmas Nightmare’s Eve . He does not typically post critical reviews of fellow authors’ works, and will not do so under any circumstances on review sites, but he makes an occasional exception in blogging about highly successful authors’ works.

January 3, 2024

Coming on Dragon Crown Books: The biography of Tempest's Lief Sorbye

Dragon Crown Books is ringing in the new year with a major announcement: I’m excited to share that I’m co-writing the authorized biography of Tempest founder, vocalist, and multi-instrumentalist Lief Sorbye.

As a Tempest fan for nearly a quarter-century and a lover of music history, I’m extremely pleased to be working with Lief on this book. I first encountered Tempest at a St. Patrick’s Day gig at Fresno’s Downtown Club in 2000, and I was hooked immediately. I’ve been attending Tempest concerts over the years ever since, and I’ve witnessed first-hand the evolution of the band, which has included an impressive array of talented musicians.

Most recently, Sharon and I attended Tempest’s concert in Reno a couple of days before our wedding. At my request, they played my request for Sharon’s favorite tune, “Jolly Roger,” and I was thrilled when they launched into my own favorite, “Hal An Tow,” immediately afterward.

Tempest has released a dozen studio albums, including their most recent, 2022’s Going Home, as well as five compilations. They tour regularly on the West Coast and across the country, including regular appearances at the Philadelphia Folk Festival.

Tempest has been blazing trails in Celtic rock since 1988, but this new book will be much more than a memoir of Lief’s time with the band. It will be a complete biography, spanning Lief’s entire life. He’s got some fascinating tales to tell from his childhood in Norway, as well as his time as a busker and with earlier bands, including Golden Bough and with his acoustic side project, Caliban. He’s also worked with some well-known people in the music industry, like the late keyboard wizard Keith Emerson (Emerson, Lake & Palmer) and frequent Tempest producer Robert Berry (The Greg Kihn Band, Ambrosia, Emerson, Carl Palmer…)

That’s just the tip of the iceberg. This will be a complete biography, illustrated with photos from Lief’s personal collection.

Lief’s biography will be my second foray into this genre of writing, 2019’s release of The Legend of Molly Bolin. I worked with Molly (Bolin) Kazmer to tell the story of her life as a trailblazer in women’s sport—the first woman to sign a contract with a pro basketball league, not to mention its leading scorer.

Dragon Crown is embarking on 2024 with a variety of projects on deck, including the second, expanded edition of Fresno Growing Up and Bonanza Highway: U.S. 95 in Nevada. That’s just the beginning. To help me achieve my goals this year, I’ve brought my wife, Sharon Marie Provost, on board full time to handle marketing and distribution, among other duties. She has some writing projects in the works as well, in the wake of co-authoring our just-released book of short stories, Christmas Nightmare’s Eve.

Look for more announcements about what’s coming from Dragon Crown and updates on The Authorized Biography of Lief Sorbye & Tempest in the coming months.

2024, here we come!

July 13, 2023

AI threatens authors by flooding the market with cheap imitations

“Why are you so worried about artificial intelligence? If your work is good, people will still buy it!”

That’s the basic argument I hear from people who think I’m reacting too strongly to generative AI (artificial intelligence that generates content). I should stop sweating it, they say. “Why not let others take advantage of it if they want to? It’s no skin off your nose. Besides, it’s fun!”

Well, I have plenty of fun doing my own writing without any help from something with the word “artificial” in its name, thank you very much. I also prefer butter to margarine, and the only reason I use artificial sweetener is because I’m diabetic, and too much sugar could kill me or cause neuropathy. I think that’s a pretty good reason.

So let’s get this out of the way right off the bat: If you have a disability that puts you at a disadvantage when it comes to writing, I have nothing against using AI to level the playing field.

But here’s the rub: For the rest of us, it doesn’t level the playing field—it tilts it toward the AI user.

Slush pileIn the era of self-publishing, writers are able to (and do) flood the market with their own works, bypassing the traditional publishing companies that served as “gatekeepers” between author and reader. They were, at best, imperfect gatekeepers, deciding what should and shouldn’t see the light of day, often using poor discretion and making rash decisions.

As someone who’s been published traditionally and who publishes his own work, I’m all in favor of self-publishing. It puts creative control in the hands of the author. However, it has the unfortunate side effect of flooding the market. When everyone from the novice to the bestseller can publish their own works, there’s a lot more from which to choose. Amazon becomes a living slush pile, and the reader has to do the work previously ascribed to the gatekeeper (traditional publisher) of deciding what’s worthy and what isn’t.

The result, predictably, is that readers—who have jobs of their own and no time to do an acquisition editor’s job on top of it—rely on things such as marketing, cover art, trends, and books that “go viral” in order to make buying decisions. Those of us who don’t have a big marketing budget are at an immediate disadvantage.

The one advantage I do have as an author is the ability to churn out a large number of titles in a short period of time. This keeps my name in front of readers, and being prolific (26 titles in three years) is a great talent to have in a world driven by instant gratification and “what have you done for me lately?”

AI robs me of that lone advantage. By generating content for “authors,” it enables them to churn out the same number of books in a fraction of the time—using work that is not their own. They are then able to flood the market and, if they have a marketing budget bigger than mine (something that is probably the norm rather than the exception), make their derivative works more visible than my original works.

Checkmate.

Class dismissedPut simply, AI gives them an unfair advantage. It tilts the playing field.

Imagine being in a class that’s graded on a curve in which everyone else has an “open-book” final exam, while you are instructed to answer questions from memory. They all get higher scores than you do, so you flunk. AI is like that. It doesn’t reflect an author’s ability, any more than such an open-book exam reflects a student’s grasp of the subject. (The use of open-book tests has, frankly, always mystified me for this very reason.)

Another analogy: Allowing one team to put a sixth player on the court during a basketball game. No one would allow that, yet a writer putting a robotic “sixth player” in the game is somehow OK? I just don’t buy it.

If you think it’s harmless, think again. Automation has already put thousands of employees out of work by replacing human checkers with automated checkstands in places like Walmart. And look what’s happened to newspapers, once gatekeepers in their own right, now reduced to a shadow of their former selves by another form of AI: targeted internet advertising. If you think the result—being without an independent watchdog holding public officials accountable—is fine and dandy, I urge you to take another look at the polarized chaos that now passes for politics and social interaction.

I haven’t even mentioned the threat AI poses to intellectual property rights. But others have. Authors Paul Tremblay and Mona Awad have sued ChatGPT’s parent company for using their novels as a framework to “train” its generative AI programs. Comedian Sarah Silverman and two other authors have done the same. If what they allege is true, this is intellectual theft. And if AI programmers can steal from others, they can steal from me.

Apples and orangesGenerative AI isn’t like a photograph in relation to a painting or an airplane compared to a bicycle. Those inventions enabled human beings to do explicitly new and different things that they hadn’t been capable of before. Generative A1 isn’t new or different; it’s derivative. It doesn’t break new ground, it mimics legitimate artistic expression and seeks to pass itself off as the same. It is, in a word, phony: an imposter seeking to supplant the real thing.

And it’s not like looking something up in a thesaurus; it’s a program that actually finishes (and suggests) full sentences for you. That, to me, is a big problem, because you’re no longer writing the book, you’re collaborating with a program that has been “trained” using the works of other authors such as Tremblay and Awad. So unless you want to share a byline with ChatGPT and whatever authors whose work it has data-mined, I suggest you avoid using it.

(Personally, I think it might be fun to write a book with Tremblay in particular, but I would have the decency to ask him to collaborate.)

I’m hardly alone in my concern about generative AI. A Reuters/Ipsos poll in May found that more than 6 in 10 Americans—not just authors and artists—are worried about the adverse effects of AI on the future of humanity.

What’s that, again, about A1 being “fun”?

My responseWhen it comes down to it, I’m not worried about Skynet taking over the world, but I am worried about AI threatening jobs and the future of free, creative artistic expression.

In response, I plan to include the following notation in my works going forward, and urge other authors to craft a similar statement.

“The contents of this volume and all other works by Stephen H. Provost are entirely the work of the author, with the exception of direct quotations, attributed material used with permission, and items in the public domain. No artificial intelligence (“AI”) programs were used to generate content in the creation of this or any of the author’s works.”

Or as Queen so succinctly put it on their best albums: “No synthesizers!”

Stephen H. Provost is the author of 50 books, covering topics ranging from highway history to the shopping centers in America, as well as fantasy, adventure, and science fiction novels. He is also the founder of the ACES of Northern Nevada online bookshop portal. His books are available on Amazon . Banner image: Jonathan Harris as Dr. Zachary Smith and the Robot from the original “Lost in Space” (public domain photograph).

January 3, 2023

Starting 2023 with a bang: 15 ebook releases and big plans ahead

Big news: All the books in my Highways of the West series, as well as my Century Cities books, are now available as ebooks for Kindle! So is Martinsville Memories, which profiles a small town in southern Virginia with a fascinating history in tobacco, textiles, and furniture-making.

So when you’re out exploring, you can take my historical travel guides along with you in handy, electronic form for easy reference.

Whether you’re planning a trip along the The Lincoln Highway in California, America’s Loneliest Road (the Lincoln in Nevada), or the Victory Highway in Nevada and the West, you’ll have a handy companion for your phone or tablet. The same is true if you’re exploring Fresno, Carson City, Greensboro, or one of the seven other towns in my Century Cities books chronicling the 20th century.

Each of these books contains a wealth of historical and contemporary photos, so you’ll know the significance of the historical places you’re seeing. (If you’re traveling the Lincoln Highway, take along a second phone to map your course using the Lincoln Highway Association’s detailed online map.)

All my books are available on Amazon, and many are available in local museums and shops around Northern Nevada. If you’re in Reno, check out Sundance Books and the Wilbur D. May Museum. In Carson City, you’ll have a hard time not finding them. The Carson City Chamber of Commerce, Nevada Day Store, Nevada State Museum, Purple Avocado, and Brewery Arts Center all have copies heading into 2023.

In Sparks, your go-to place for five of my books is the Sparks Museum. In Eureka, it’s Raine’s Market. In Fallon, it’s the Churchill County Museum. And in Ely, it’s the Nevada Northern Railway Museum, This and That on Main Street, or the Art Bank. All are carrying America’s Loneliest Road.

And that’s not all. America’s Loneliest Road is available all across the Interstate 80 corridor from Wendover, Utah, at the Wendover Air Force Base Museum, to Battle Mountain at the Cookhouse Museum, the Humboldt County Museum in Winnemucca, and two museums in Elko: The Northeastern Nevada Museum and Sherman’s Station Visitor’s Center.

More to comeThis year, I’m hoping to have my new book on U.S. 40, Victory Road, in many of those locations, as well.

My final book of 2022, released just before midnight on New Year’s Eve, takes you from the Bonneville Salt Flats through Nevada and across the Sierra on the old Victory Highway and Highway 40. Residents of places like Elko, Reno, Sparks, Winnemucca, and Battle Mountain will love this new journey.

What else is ahead in 2023? I wrote six books last year, and I don’t plan to slow down. I have books planned on two more highways (and possibly a third), more Century Cities, and a couple of surprises. You’ll also be able to catch me at several events. I’m hoping to get a spot at the Mark Twain Days in Carson City on April 22 and 23 (to showcase my new release Mark Twain’s Nevada), and planning to attend the Lincoln Highway Association’s national meeting in California this summer. You’ll find all my highway books available there.

Other hoped-for appearances include Jim Butler Days in Tonopah in May, and return appearances at Goldfield Days, Beatty Days, Dayton Valley Days, St. Mary’s Art Center in Virginia City, Gardnerville holiday craft fair, and the Sparks Museum’s holiday events. That’s just the beginning. I’ll be sharing those dates and others as they’re firmed up.

In all, 2023 is going to be a very busy and wonderful ride. Happy New Year, everyone. I look forward to sharing it, and my adventures, with all of you.

Stephen H. Provost is a former journalist, editor, and author of

more than 40 books

. Forty-five, actually. Big 5-0, here I come!

January 2, 2023

How not to write a twist: the LOTR prequel (spoilers)

Spoiler alert: If you haven’t seen The Rings of Power, Amazon’s Lord of the Rings prequel series, you will probably want to stop reading here. This article continues MAJOR spoilers.

I haven’t written much fiction lately, but if you’re familiar with my novels and short stories, you know that I love a good twist. (My first novel, Identity Break, was built entirely around a plot twist, and I incorporated several twists into my collection of short stories, Nightmare’s Eve.)

The writers of The Rings of Power seem to share that affection. Unfortunately, their series on Amazon Prime is a textbook example of how NOT to write a twist.

A twist involves an unexpected change in direction with regard to plot or character. But a good twist has to make sense once it’s revealed: It can’t seem forced, contrived, or inconsistent with what’s been revealed previously. The Sixth Sense is a prime example of a movie with a great twist: The writer, M. Night Shyamalan, even included a series of flashback/recap scenes to show the audience the clues they missed the first time around.

The writers of The Rings of Power should have been taking notes, because they included two major plot twists – both of which felt incredibly forced and contrived. (Here’s where the spoilers begin.)

The StrangerThe first involves a character known simply as The Stranger, a full-grown man who crashes to earth in a meteorite with a case of amnesia. He has difficulty speaking, at least in English, so we’re left to speculate who this person might be, although the Harfoot girl Nori keeps insisting that he’s “good.” It therefore comes as quite a shock when three white-robed characters appear in the season’s final episode and declare him to be none other than that epitome of evil, Sauron, the main antagonist in the story.

This declaration is a major twist, because the writers have kept the audience guessing about who Sauron might be to this point. But the twist feels forced in the extreme. The three robed figures’ background is not explained, nor is their reason for identifying The Stranger as Sauron. They are simply a plot device to throw a halfhearted head fake at the audience that was so unconvincing I immediately dismissed it out of hand. I had guessed early on that The Stranger was, in fact, Gandalf the Grey – a guess later confirmed by his use of a quote (“When in doubt… follow your nose”) uttered by Gandalf in The Lord of the Rings.

But the second twist, if anything, was even more badly bungled than the first. As mentioned, the writers kept the audience guessing throughout the season as to the identity of Sauron, at one point introducing a character named Adar who seemed to fit the description quite nicely. But it was clear he fit a little too well, and that the writers were using him as another head fake to throw the audience off. In their defense, Adar was developed far more fully than the three cardboard-cutout white-robed figures, and was a nicely drawn character in his own right.

He was not, however, Sauron.

HalbrandIn the end, Sauron turns out to be none other than Halbrand, a mysterious stranger the elf warrior Galadriel encounters on a raft in the middle of the ocean. This was certainly a shocking twist and one I didn’t see coming. But after it was revealed, it still didn’t make sense to me. And therein lies the problem: A good twist leaves the audience saying to themselves, “Of course! I should have seen that coming.” This one, though, just left me scratching my head in bemusement.

To be sure, Halbrand never seems like a model of integrity. We know, for instance, that he left some companions to die in the middle of the ocean, but he excused it at the time as an unfortunate necessity to ensure his own survival. He never seems like the megalomaniac we know Sauron to be, but rather a morally ambiguous – and very conflicted – opportunist, more a scalawag than a sociopath. A con artist at worst.

Even stranger, Halbrand never exhibits any ability at all to use magic. In one instance, when he is threatened by a bunch of thugs, he uses his fists – not magic – to get the better of them, then winds up in a prison cell, where he makes no attempt to escape using magic. This, we are supposed to believe, is the world’s most powerful dark sorcerer? Does he have amnesia like The Stranger? This seems unlikely, since he seems to remember doing something horrible, for which he confesses his guilt in vague terms to Galadriel. Besides, even the amnesiac Stranger uses his powers in scattershot fashion, something Halbrand never does.

Or is Halbrand merely trying to remain incognito? Does he not turn fully evil until he is scorned by Galadriel? This, too, seems unlikely, because Galadriel appears convinced she has rejected an irredeemably evil scourge, not a simple misguided rogue.

The point is that none of this adds up. It’s possible that the writers are leaving some revelations for a future season, but twists should be fully resolved within a single work, not left hanging for a sequel. If they are, they seem inauthentic and the audience feels cheated. Unresolved twists should not be left as part of cliffhangers. That’s either lazy or disingenuous – or both.

It leaves a sour taste in the audience’s mouth, which is exactly what The Rings of Power did. It twisted viewers into knots, but the plotline came unraveled when the observant viewer pulled on a strand of loose thread.

Stephen H. Provost is a former journalist, editor, and author of more than 40 books. As with many others, “The Hobbit” was his introduction to fantasy literature.

March 16, 2022

"Step foot" isn't just a secondary usage, it's wrong

Grammar experts use an odd standard when deciding what’s acceptable and what isn’t. They often argue that a word or phrase can be used in a certain way based on precedent: if it was used that way a long time ago, it must be OK now.

In other words, “If it’s old, it must be right.”

Imagine if we applied that faulty logic to the ancient believe that the sun revolved around the Earth. To paraphrase Tim Minchin in his song “White Wine in the Sun,” just because ideas are tenacious, that doesn’t mean they’re worthy.”

Two plus two doesn’t equal five just because someone added things up wrong a couple of thousand years ago. It was wrong then, and it’s wrong now. The Earth isn’t flat today because people used to think it was. Language is, to some extent, the same way. It’s not quite as clearcut as mathematics, and it does evolve, but that doesn’t mean there can’t be obvious right and wrong choices.

There are.

Even better, you can often tell what they are using a simple standard: Do they improve communication or make it worse?

Such is the case with the debate between “set foot” and the increasingly popular alternative, “step foot.” I can tell you right now, unequivocally, that the traditional “set foot” is correct, and “step foot” isn’t.

It’s not a popularity contestOne researcher noted in 2014 that “step foot” isn’t as old as “set foot.” And “set foot” is more widely used too. My Google search turned up some 20 million hits for “set foot” and “setting foot,” compared with about 6.5 million for the step and stepping alternatives — about three times as many. But the ugly step-child appears to be gaining ground: In that 2014 blog, “set foot in” registered more than five times as many hits as the lame alternative.

My favored usage is still comfortably ahead, but this isn’t a popularity contest. It’s about precise usage.

The term “stepping foot” is simply redundant.

To illustrate, I’ll substitute the hand for the foot. You can place or set your hand anywhere, but you never step with it. Stepping is only done with the foot — and that’s the key. To say you’re “stepping foot” somewhere is redundant. What else would you be stepping with? Your nose? Your rear end? Your jacket?

Each of these options is patently absurd. You can only step with a foot, so saying you’re “stepping foot” someplace is unnecessary and just plain silly. It’s like saying you’re hearing something with your ears. Who says that? Or you’re smelling something with your nose. I assume you weren’t sniffing with your small intestine.

Worse, “stepped foot” is simply improper usage. “Set” is a transitive verb: something you do to something else. “Step” is not. (The often-misunderstood lay/lie distinction functions the same way). You wouldn’t say, “I stepped my foot down” or “I stepped my foot in some horse manure.”

What about footsteps?But doesn’t the term “footsteps” create the same problem? Why not just say “steps”? You can certainly do so and be clearly understood. But steps in this context is a noun, not a verb, and it can mean several things: the steps you take when walking, steps on a staircase/ladder, or figurative steps taken toward a goal.

There’s not much room for confusion here: If you say you hear steps behind you, no one’s going to conclude a ladder is following you, and if you say you’ve taken “concrete steps,” it’s unlikely that anyone will accuse you of stealing concrete steps from the high school stadium. (For one thing, they’re attached and too heavy; for another, why would you do so?)

Still, there are multiple uses for the noun “step,” so “footsteps” doesn’t bother me as much as a means of providing additional clarity. It passes the test of improving communication, if modestly so. The phrase “step foot,” on the other hand, does not.

“Set foot” is perfectly clear on its own. There’s no other way of using it, so there’s not even a hint of potential or farfetched ambiguity.

It’s therefore entirely pointless to use the redundant “step foot.”

Language can be silly and nonsensical at times. This is especially true of English, which has its share of ridiculous usages. But that doesn’t mean we should add to them necessarily. In this case, our course is clear: We should take a step back and set our foot firmly on the clearest, straightest path.

Stephen H. Provost is a former journalist, editor, and the author of more than 40 books. He steps softly and carries a big red pen.

March 6, 2022

If you like Images of America books, you'll love these

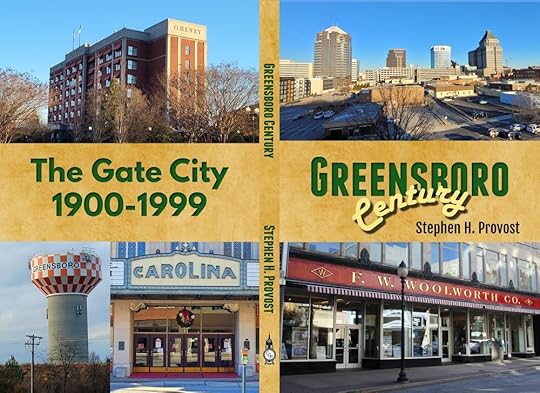

With the release of Greensboro Century, I’ve just wrapped up the ninth book in my Century Cities series.

If you know authors, you know we’re always on the lookout for good ideas, books that inspire us and may even prompt us to say to ourselves: “I could do that, only better!”

That might sound a bit arrogant, and we’re not always right. Sometimes we are, though, and even when we’re not, the results can still be pretty damn good. The more good books there are, the better — especially when it comes to history.

My Century Cities books were the product of just such an “I could do that, only better!” moment. The idea came to me after I’d wrapped up Highways of the South, my fifth book focusing on the nation’s highways during the 20th century.

In asking myself what I’d do next, I remembered coming across a series of books by Arcadia Publishing, which specializes in local and regional history through its Images of America series and History Press imprint. You’ve probably seen them: There are literally thousands of titles, many with sepia-toned covers, and some of them are very well done. Others are less so; it depends in large part on the quality of the writing.

Context is key to historyMany of the books don’t have much writing. Most often, the emphasis is on the images (hence the series title Images of America). I found myself enjoying the visuals of the Arcadia books, but wanting to know more about the stories behind them.

I thought to myself, “I enjoy these books, but I think I could do it better.” Being a writer and a photographer, as well as a researcher, I thought I could bring all those talents together and create histories that balanced text and visuals to provide a more complete picture than many of the Arcadia books do. Essentially, I’d be taking my own photographs, and using historical photos, but placing them in better context by telling the stories behind them more fully.

Context is important to me. It’s something we, as a society, have lost track of to a great degree — especially with regard to history. For instance, one survey found that barely a quarter (27 percent) of eighth-graders could identify how African Americans affected the Civil War, and just 31 percent answered “the government should be a democracy” when asked to choose belief commonly held in the United States.

(In light of this, it makes more sense that Americans are susceptible to the kind of authoritarian B.S. peddled by Trump and his sycophants/imitators.)

A chronological approachOne way to provide context is to create chronology — a timeline that shows how we evolved and progressed as a nation. I applied that principle to my Century Cities books, which are presented chronologically with each chapter devoted to a different decade, and sections within those chapters to each successive year.

That’s not something you’ll find in the Arcadia books that I’ve seen. They do have some excellent “then and now” pictorial books that compare photos of different locations from an earlier time with how they appear today, but I haven’t seen a true chronological treatment.

None of this is a knock on the Arcadia books. The more books out there that reconnect us with our history, the better, and many of them are very well done. Buy them! That said, I believe I am doing what I set out to do with this series: I’m doing what Arcadia’s doing, only better.

That’s not arrogance. It’s pride of authorship.

I invite you to check out the books in this series, and in all honesty, I think you’ll agree.

Century Cities books, all available in paperback or hardcover:

CaliforniaCambria Century, 2021

Fresno Century, 2021

San Luis Obispo Century, 2021

NevadaCarson City Century (forthcoming)

Goldfield Century, 2021

Reno Century (forthcoming)

North CarolinaAsheboro Century (forthcoming)

Greensboro Century, 2022

Winston-Salem Century (forthcoming)

Raleigh Century (forthcoming)

Durham Century (forthcoming)

VirginiaDanville Century, 2021

Roanoke Century, 2021

West VirginiaCharleston Century, 2021

Huntington Century, 2021

Stephen H. Provost is the author of more than 40 books, including nine in the Century Cities series. All his books are available on Amazon.

History in context: Century Cities vs. Images of America

With the release of Greensboro Century, I’ve just wrapped up the ninth book in my Century Cities series.

If you know authors, you know we’re always on the lookout for good ideas, books that inspire us and may even prompt us to say to ourselves: “I could do that, only better!”

That might sound a bit arrogant, and we’re not always right. Sometimes we are, though, and even when we’re not, the results can still be pretty damn good. The more good books there are, the better — especially when it comes to history.

My Century Cities books were the product of just such an “I could do that, only better!” moment. The idea came to me after I’d wrapped up Highways of the South, my fifth book focusing on the nation’s highways during the 20th century.

In asking myself what I’d do next, I remembered coming across a series of books by Arcadia Publishing, which specializes in local and regional history through its Images of America series and History Press imprint. You’ve probably seen them: There are literally thousands of titles, many with sepia-toned covers, and some of them are very well done. Others are less so; it depends in large part on the quality of the writing.

Context is key to historyMany of the books don’t have much writing. Most often, the emphasis is on the images (hence the series title Images of America). I found myself enjoying the visuals of the Arcadia books, but wanting to know more about the stories behind them.

I thought to myself, “I enjoy these books, but I think I could do it better.” Being a writer and a photographer, as well as a researcher, I thought I could bring all those talents together and create histories that balanced text and visuals to provide a more complete picture than many of the Arcadia books do. Essentially, I’d be taking my own photographs, and using historical photos, but placing them in better context by telling the stories behind them more fully.

Context is important to me. It’s something we, as a society, have lost track of to a great degree — especially with regard to history. For instance, one survey found that barely a quarter (27 percent) of eighth-graders could identify how African Americans affected the Civil War, and just 31 percent answered “the government should be a democracy” when asked to choose belief commonly held in the United States.

(In light of this, it makes more sense that Americans are susceptible to the kind of authoritarian B.S. peddled by Trump and his sycophants/imitators.)

A chronological approachOne way to provide context is to create chronology — a timeline that shows how we evolved and progressed as a nation. I applied that principle to my Century Cities books, which are presented chronologically with each chapter devoted to a different decade, and sections within those chapters to each successive year.

That’s not something you’ll find in the Arcadia books that I’ve seen. They do have some excellent “then and now” pictorial books that compare photos of different locations from an earlier time with how they appear today, but I haven’t seen a true chronological treatment.

None of this is a knock on the Arcadia books. The more books out there that reconnect us with our history, the better, and many of them are very well done. Buy them! That said, I believe I am doing what I set out to do with this series: I’m doing what Arcadia’s doing, only better.

That’s not arrogance. It’s pride of authorship.

I invite you to check out the books in this series, and in all honesty, I think you’ll agree.

Century Cities books, all available in paperback or hardcover:

CaliforniaCambria Century, 2021

Fresno Century, 2021

San Luis Obispo Century, 2021

NevadaCarson City Century (forthcoming)

Goldfield Century, 2021

Reno Century (forthcoming)

North CarolinaAsheboro Century (forthcoming)

Greensboro Century, 2022

Winston-Salem Century (forthcoming)

VirginiaDanville Century, 2021

Roanoke Century, 2021

West VirginiaCharleston Century, 2021

Huntington Century, 2021

Stephen H. Provost is the author of more than 40 books, including nine in the Century Cities series. All his books are available on Amazon.

March 5, 2022

Greensboro, from blue jeans to Woolworth's, explored in new book

I started my Century Cities series an hour to the north of my home in Martinsville, Virginia, and eight books later, I headed an hour south to Greensboro for Book No. 9.

Greensboro was actually a little closer than Roanoke, so I’d been there often before I decided to write about it. I’ve shopped at the Friendly Center and the Four Seasons mall. I’ve explored shops downtown. I’ve eaten several meals at the Green Valley Grill, a delicious restaurant at the new O. Henry Hotel (which isn’t the same as the original O. Henry, I discovered in researching this book.)

I’ve even taken some photos there for The Great American Shopping Experience, my book on the history of retail in 20th century America.

Greensboro is perhaps best known as the birthplace of the lunch-counter sit-in movement that helped break segregation in the South. It was there, at a Woolworth’s on Elm Street, that four Black college students from North Carolina A&T sat down at a segregated counter to be served. It was the beginning of a movement that would spread across the South, a key moment in the struggle for civil rights.

What I didn’t know is that the struggle had played out on a segregated city golf course a few years earlier, leading to a landmark court decision that built on Brown v. Board of Education.

Greensboro’s been a transportation hub since the end of the 19th century, when trains rolled in and out at a rate of 60 a day. That’s how it got its nickname, “The Gate City.” Fewer trains pass through these days, but several highways meet in Greensboro, branching out to Roanoke in the north, Raleigh-Durham in the east, Winston-Salem in the west, and Charlotte to the south.

The 20th century saw Greensboro grow from a city of barely 10,000 people at its outset to a bustling metropolis of more than 220,000 by the end of the millennium. In the meantime, it gave birth to a textile boom that blossomed into a blue jean bonanza. It has hosted a major golf tournament that’s been won by the likes of Sam Snead, Billy Casper, and Gary Player.

The city hosted an NCAA Final Four basketball tournament, won by home-state favorite North Carolina State, and even had its own pro basketball team in the American Basketball Association for a few years. The Carolina Cougars were coached by Hall of Famer Larry Brown from 1972 to 1974 and led by another Hall of Famer, Billy Cunningham, the league’s MVP in 1973

The famed short story writer O. Henry (real name: William Sidney Porter, for whom the hotel was named) worked at a downtown pharmacy owned by his uncle called Porter’s Drugs. A later owner of that same drugstore developed a famous treatment for head and chest congestion that's still popular today: Vicks VapoRub.

His name wasn’t Vick, though.

From blue jean and textiles to the Woolworth’s lunch counter Greensboro Century is filled with stories of milestones in the city’s history during the 20th century. Packed with historical images and contemporary photos I took myself, it’s a year-by-year chronicle of how Greensboro has grown and changed over the years.

If you’ve ever been to Greensboro or are planning to go, I invite you to take this journey with me back in time to North Carolina in the 20th century — and, if you’re interested, side trips to Roanoke or Danville in Virginia; Fresno, San Luis Obispo, or Cambria in California; Charleston or Huntington, West Virginia; or the Nevada boomtown of Goldfield.

Greensboro Century, like all the books in this series, is available on Amazon in paperback or keepsake hardcover editions.

I hope to see you there.

February 6, 2022

Why independent publishing is so tough for many authors

The transition from traditional to independent publishing has been a mixed bag for authors. It has opened up a wealth of opportunities — but it’s also created a ton of competition.

Talented writers who couldn’t get published in the past, either because they were overlooked or didn’t fit into publishers’ marketing plans, can now get their books into print (and onto Kindle) all by themselves. But not-so-talented writers have the same access. That means the publishers’ slush pile has turned into a readers’ slush pile, and good material can still get lost in the shuffle.

But that’s not the only fallout from the new Wild West of publishing.

The decline of traditional promotional outlets like newspapers has taken a toll as well. When it comes to marketing, social media sites have taken the place of old-line media. Independent authors don’t have access to the promotional tools used by traditional houses, and even those signed to publishing contracts need to do their share of the legwork these days. They’re expected to have a social media presence, and know how to use it — to engage with readers on a personal level.

Many authors, however, are not comfortable doing that.

Writing is, as the saying goes, a lonely profession — and many authors like it that way. J.D. Salinger, William Faulkner, Emily Dickinson, Harper Lee, and others shunned publicity and preferred the comforts of home to the discomforts of the cold, cruel world. Some write to escape that world, and others escape the world to write.

I do both.

A lot of us are introverts, and the increased levels of isolation during the COVID pandemic only reinforced our detachment from the world “out there.” Our books are our babies, and as hard as we may try to let criticism roll off our backs, we’d rather spend our time writing than having to deal with feedback from readers who think they know more about our books than we do.

When I worked in newspapers, I always wanted to respond to criticism with: “If you don’t like how this turned out, you try it. I dare you!” There’s a reason they used to call newspapers “the daily miracle,” and books are no picnic to write, either. If I had a dime for everyone who’s told me they always wanted to write a book...

Many of us have learned to look stop obsessing over (and responding to) Amazon reviews, and we venture out of our seclusion to attend book signings like bears emerging from hibernating in our own creative caves. To mix metaphors, we’re lone wolves, not party animals. When I leave the comfort of home, it’s to hit the open road and find pieces of history on the side of the road, not to interact with other people. Maybe that’s one reason I enjoy visiting abandoned places so much.

Even online, I’d rather be researching than interacting. For many authors, social media sites aren’t our comfort zone, and we’re not necessarily built for making YouTube videos or hosting podcasts. But such things are part and parcel of marketing in current publishing age.

So we’re faced with a few choices: We can hire someone to do that stuff for us. (Like we’re independently wealthy, right?) We can eat into our writing time by doing it ourselves. Or we can say to hell with it and just write for our own enjoyment. But again, it helps to be independently wealthy if you want to do that, or at least retired.

I don’t have any answers on how best to deal with this. It depends, I suppose, on each author’s goals and comfort level.

But these aren’t easy choices.

Some authors don’t have to make them, of course. There are talented writers who get a kick out of promotion; it comes naturally to them. They’re as skilled at marketing, or nearly so, as they are at writing; some enjoy it as much and perhaps even more. More power to them. For most of us, though, it’s not nearly as much fun dealing with the real world and real people as it is creating characters and building our own worlds.

A lot of us wish you’d get to know us through our books because we’re shy, and that’s how we communicate who we are. It’s safer that way.

Indeed, many of us can relate to this quote from author Lauren Myracle: “I live in my own little world, but it’s OK, they know me here.”

That may not be an option in this brave new world of publishing, but we authors aren’t necessarily brave when it comes to social interactions. Some of us have become pretty good at faking it, but most of us would prefer to let our writing speak for us — and for itself.

Stephen H. Provost is a former journalist and the author of 40 books. He’s also an introvert, which is why he’s been able to write 40 books!