Maya Thiagarajan's Blog

August 28, 2019

From Coverage to Learning: Making the Shift in Indian Schools

“But if thought corrupts language, language also corrupts thought.” – George Orwell

I walk into a Standard 9 classroom. It’s a Physics Class on “Force and the Laws of Motion.” Dressed in a bright blue sari, the teacher stands at the front of the room and patiently explains Newton’s first law of motion. Then she asks a question based on it. A few diligent children in the front two rows seem to be taking down notes. Two very bright boys call out answers in response to the teacher’s question. In the back of the class, however, one boy stares vacantly out the window, gazing at the tree in the distance. Another girl is busy drawing an elaborate design on a piece of scrap paper at the back of her notebook. While the hot midday sun streams in through the window, a number of students fidget in their seats, looking confused and lost.

The teacher smiles wearily at the class, and then bravely marches on to introduce the next law and ask the next question.

When I chatted with the teacher after class, I asked her why she didn’t slow down to check for understanding and review concepts, when so many students seemed to be having difficulty following what she was teaching. “But I need to cover the portions,” she responded, “I don’t have time to stop.”

When I started visiting Indian schools as an education consultant, perhaps what struck me most forcefully was the tremendous emphasis on “coverage.” The phrase “cover the portions” is used so widely across our schools, and it has seeped so deeply into the psyche of our teachers, that it seems to dictate what happens in the classroom.

In schools across Tamil Nadu, teachers use a certain kind of language. They worry about “covering the portions,” and they spend a lot of time thinking and talking about “revisions, exams, and marks.” They also try to “get through the text book” and “ensure that students do the book back questions” (or in normal speak, the questions at the back of each chapter in the text book). They make sure that they “clarify doubts” by giving students the right answers.

While they use the verb “teaching” a lot, they rarely use the verb “learning.”

Rarely do I hear teachers use words such as “learning, thinking, imagining, wondering, analyzing, and creating.” I keep looking for these words in our conversations, but like beautiful flowers that bloom very rarely, they remain elusive.

Having taught for many years, I know from experience that just because I have taught something doesn’t mean that students have learned it. Teaching and learning are not synonyms, though ideally learning should be the outcome of good teaching.

Similarly, coverage and understanding are not synonyms either. A teacher can “cover” the portions, but that does not mean that students have understood anything.

Furthermore, in many schools across our country, the end goal of education seems to be “scoring on exams.” A “good school” is one with “good results.” But “high exam scores and good results” are not synonyms for “long term success and happiness.” (In fact, studies show that the correlation between a student’s exam scores in school and his or her long term professional and personal success and happiness is surprisingly weak.)

What I wonder, however, is how the language that we use shapes the way we think about education. If we changed our language, would we also change our thinking and behavior?

What would our education system be like if teachers felt less pressure to “cover portions” and more pressure to ensure that students are engaged and learning? What if we didn’t just “clarify doubts” but actually pushed our students to think more deeply and ask more questions? What if we worried less about preparing our students for exams and more about preparing our students for life? What if we shifted our language to regularly include words like learning, imagining, questioning, wondering, analyzing, inferring, creating, and thinking. What would our education system be like then?

Perhaps then, the teacher in that physics class on the laws of motion would be free to slow down and check for understanding. Perhaps she’d even have the time and motivation to come up with imaginative ways to teach each concept so that every child could access it. And the outcome of the class would not be mere “coverage,” but would instead be “deeper engagement, thinking, and learning.”

Published on August 28, 2019 01:50

November 7, 2016

BOOKS EVERY TEACHER MUST READ!

On Reading:

The Book Whisperer, by Donalyn MillerReading in the Wild, by Donalyn Miller

Book Love, by Penny Kittle

Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain, by Maryanne Wolfe (brilliant and beautiful, but more complex than the titles above; this is one of my all-time favorite books)

Reading in the Brain, by Stanislas Dehaene (a little more scientific and technical, but a very interesting read.)

On Early Childhood (Great for parents as well)

Your Child’s Growing Mind, by Jane Healy

Einstein Never Used Flashcards, by Hirsch and Golinkoff

What Every Kindergarten Teacher Should Know, by M.B.Wilson

On Math:

What’s Math Got to Do With It? By Joanne Boaler (some interesting insights, even though I'm generally critical of Jo Boaler's approaches, which have fuelled so much of contemporary "reform" Math instruction in the US)

Number Sense, by Stanislas Dehaene (quite scientific, little more difficult but interesting)

On Teaching Character

Mindset, by Carol Dweck

How Children Succeed, by Paul Tough

The Whole Brain Child, by Daniel Siegel

On Schools/Education/Learning more generally

The One World Schoolhouse, by Salman Khan (founder of the Khan academy)

Education Nation, by Milton Chen

Why Children Don’t Like School, by Daniel Willingham

Beyond the Tiger Mom: East-West Parenting & Education for the Global Age, by Maya Thiagarajan (Lots of great info on math, reading, memory and other hot-button education topics.)

On Assessment

Embedding Formative Assessment: Practical techniques for K-12 teachers, by Dylan Williams

On Learning and the Brain/Neuroscience

How the Brain Works, by Donald Kotulak

The Jossey Bass Reader on the Brain and Learning, Edited by Kurt Fischer

The Shallows: What the Internet is doing to our Brains, by Nicolas Carr

Brain Rules, by John Medina

On the Importance of Nature for Children

Last Child in the Woods, by Richard Louv

On Curriculum Design and Pedagogy

Essential Questions: Opening Doors to Student Understanding, by Jay McTighe and Grant WigginsUnderstanding By Design, by Jay McTighe and Grant Wiggins

Making Thinking Visible (multiple authors)

Cultivating Intellectual Character, Ron Ritchard (I found this book really interesting, and it certainly had a big impact on my teaching.)

On East-West Differences in Education and Learning

The Cultural Foundations of Learning, by Jin Li (very academic, but very interesting)Beyond The Tiger Mom: East-West Parenting for the Global Age, by Maya Thiagarajan

On Multiple Intelligences

Frames of Mind, by Howard Gardner

Multiple Intelligences, by Howard Gardner

Emotional Intelligence, by Daniel Goleman

Other Important Books for Educators

Quiet, by Susan Cane (on introverted children)

Rapt: Attention and the Focused Life, by Winifred Gallagher (on focus and attention)

Flourish, by Martin Seligman (on Positive Psychology)

What books would you add to this list? Please let me know!

The Book Whisperer, by Donalyn MillerReading in the Wild, by Donalyn Miller

Book Love, by Penny Kittle

Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain, by Maryanne Wolfe (brilliant and beautiful, but more complex than the titles above; this is one of my all-time favorite books)

Reading in the Brain, by Stanislas Dehaene (a little more scientific and technical, but a very interesting read.)

On Early Childhood (Great for parents as well)

Your Child’s Growing Mind, by Jane Healy

Einstein Never Used Flashcards, by Hirsch and Golinkoff

What Every Kindergarten Teacher Should Know, by M.B.Wilson

On Math:

What’s Math Got to Do With It? By Joanne Boaler (some interesting insights, even though I'm generally critical of Jo Boaler's approaches, which have fuelled so much of contemporary "reform" Math instruction in the US)

Number Sense, by Stanislas Dehaene (quite scientific, little more difficult but interesting)

On Teaching Character

Mindset, by Carol Dweck

How Children Succeed, by Paul Tough

The Whole Brain Child, by Daniel Siegel

On Schools/Education/Learning more generally

The One World Schoolhouse, by Salman Khan (founder of the Khan academy)

Education Nation, by Milton Chen

Why Children Don’t Like School, by Daniel Willingham

Beyond the Tiger Mom: East-West Parenting & Education for the Global Age, by Maya Thiagarajan (Lots of great info on math, reading, memory and other hot-button education topics.)

On Assessment

Embedding Formative Assessment: Practical techniques for K-12 teachers, by Dylan Williams

On Learning and the Brain/Neuroscience

How the Brain Works, by Donald Kotulak

The Jossey Bass Reader on the Brain and Learning, Edited by Kurt Fischer

The Shallows: What the Internet is doing to our Brains, by Nicolas Carr

Brain Rules, by John Medina

On the Importance of Nature for Children

Last Child in the Woods, by Richard Louv

On Curriculum Design and Pedagogy

Essential Questions: Opening Doors to Student Understanding, by Jay McTighe and Grant WigginsUnderstanding By Design, by Jay McTighe and Grant Wiggins

Making Thinking Visible (multiple authors)

Cultivating Intellectual Character, Ron Ritchard (I found this book really interesting, and it certainly had a big impact on my teaching.)

On East-West Differences in Education and Learning

The Cultural Foundations of Learning, by Jin Li (very academic, but very interesting)Beyond The Tiger Mom: East-West Parenting for the Global Age, by Maya Thiagarajan

On Multiple Intelligences

Frames of Mind, by Howard Gardner

Multiple Intelligences, by Howard Gardner

Emotional Intelligence, by Daniel Goleman

Other Important Books for Educators

Quiet, by Susan Cane (on introverted children)

Rapt: Attention and the Focused Life, by Winifred Gallagher (on focus and attention)

Flourish, by Martin Seligman (on Positive Psychology)

What books would you add to this list? Please let me know!

Published on November 07, 2016 05:16

November 2, 2016

And the real culprit is...overstimulation

Bleary eyed. Heads down on their desks. Yawns.

Why are these kids always so tired?

Everyday, my students walk into class looking exhausted. When I ask them how they're doing, invariably the response I get is, "I'm so tired." And increasingly, kids tell me that they feel anxious, overwhelmed, and stressed.

Parents and teachers tend to assume that the culprit is too much schoolwork. If we assign less homework, the kids will be fine. If we have fewer assessments, the stress will dissipate.

But I don't think that schoolwork is the primary culprit.

The primary culprit for rising levels of exhaustion, anxiety, and stress is overstimulation. Students today have too much going on in their lives -- and between the floods of emails, digital notifications, pings on their phones, visual images, tweets, back-to-back enrichment activities, social engagements, assignments, deadlines, commitments, sugar binges, sports tournaments, and snapchat -- they're just so overstimulated that their bodies and minds can't actually handle it. (The same is true for many working adults as well, I think. We're just way too overstimulated.)

Call me old-fashioned, but I don't think that speed is always a good thing. And I'm not sure that "efficiency" and "productivity" (all words that describe machines and the mechanization of society) are the goals that we should be working towards. The fact is, we're not machines, and our job is not to "process" vast quantities of information and "perform" one task after another. If you ask me, human=machine is a destructive metaphor.

We're people. We're human. We're reflective, contemplative, emotional, irrational, and complex. And that's what makes us so interesting and creative.

And the reality is that our bodies and minds haven't yet caught up with the frenzied pace of an overstimulated digital and global world. And while we may think that "working like a machine" is a good thing in this age of machine-like multitasking, efficiency, and speed, the fact of the matter is that we're destroying ourselves by trying to be more machine-like, more overstimulated, more busy than we can actually handle.

So my goal for my own children is to lower the levels of stimulation that they encounter at home.

They don't need sugary snacks and lots of treats; they need vegetables.They don't need social media; they need cuddles and real life, face-to-face conversations with their parents and grandparents.They don't need a flood of bite-sized superficial bits of information, they need old-fashioned books, the longer the better.They don't need back-to-back enrichment activities, they need time at home to read, daydream, play, and rest.They don't need so much breadth -- so much exposure to so many, many different things all at once; they need depth in their lives. Let's do less, much less, but let's do it better.They don't need to "work like machines" and "multi-task" and "be efficient." They need to work like humans -- slowly, reflectively, contemplatively, creatively. You know what? They need some time to daydream, imagine, and think. They need to slow down.

And here's the catch, if they have a little more time to get their homework done, slow and sustained academic work may actually help them feel more centred, more focused, and more calm. Like I said, I don't think that it's academic work that's the problem. It's all the other stuff .... the hyper-stimulated world that our kids live in.

Why are these kids always so tired?

Everyday, my students walk into class looking exhausted. When I ask them how they're doing, invariably the response I get is, "I'm so tired." And increasingly, kids tell me that they feel anxious, overwhelmed, and stressed.

Parents and teachers tend to assume that the culprit is too much schoolwork. If we assign less homework, the kids will be fine. If we have fewer assessments, the stress will dissipate.

But I don't think that schoolwork is the primary culprit.

The primary culprit for rising levels of exhaustion, anxiety, and stress is overstimulation. Students today have too much going on in their lives -- and between the floods of emails, digital notifications, pings on their phones, visual images, tweets, back-to-back enrichment activities, social engagements, assignments, deadlines, commitments, sugar binges, sports tournaments, and snapchat -- they're just so overstimulated that their bodies and minds can't actually handle it. (The same is true for many working adults as well, I think. We're just way too overstimulated.)

Call me old-fashioned, but I don't think that speed is always a good thing. And I'm not sure that "efficiency" and "productivity" (all words that describe machines and the mechanization of society) are the goals that we should be working towards. The fact is, we're not machines, and our job is not to "process" vast quantities of information and "perform" one task after another. If you ask me, human=machine is a destructive metaphor.

We're people. We're human. We're reflective, contemplative, emotional, irrational, and complex. And that's what makes us so interesting and creative.

And the reality is that our bodies and minds haven't yet caught up with the frenzied pace of an overstimulated digital and global world. And while we may think that "working like a machine" is a good thing in this age of machine-like multitasking, efficiency, and speed, the fact of the matter is that we're destroying ourselves by trying to be more machine-like, more overstimulated, more busy than we can actually handle.

So my goal for my own children is to lower the levels of stimulation that they encounter at home.

They don't need sugary snacks and lots of treats; they need vegetables.They don't need social media; they need cuddles and real life, face-to-face conversations with their parents and grandparents.They don't need a flood of bite-sized superficial bits of information, they need old-fashioned books, the longer the better.They don't need back-to-back enrichment activities, they need time at home to read, daydream, play, and rest.They don't need so much breadth -- so much exposure to so many, many different things all at once; they need depth in their lives. Let's do less, much less, but let's do it better.They don't need to "work like machines" and "multi-task" and "be efficient." They need to work like humans -- slowly, reflectively, contemplatively, creatively. You know what? They need some time to daydream, imagine, and think. They need to slow down.

And here's the catch, if they have a little more time to get their homework done, slow and sustained academic work may actually help them feel more centred, more focused, and more calm. Like I said, I don't think that it's academic work that's the problem. It's all the other stuff .... the hyper-stimulated world that our kids live in.

Published on November 02, 2016 21:20

What Does It Take To Be A Great Teacher?

So what really makes a great teacher? Last year, I asked my graduating class this question and their reply was interesting: great teachers are ones who care about students.

And this, to me, I think is the most important and rewarding part of teaching. Great teaching always happens in the context of a strong, supportive, and mutually respectful relationship. When a student knows that a teacher genuinely cares about his or her well-being and learning, then the student becomes deeply invested in the learning process. The more I think about it, the more I think that the teacher-student relationship is, in fact, the most essential pre-requisite for great teaching and deep learning.

I would add that the next essential element is a deep passion for one's subject matter and the teacher's own love of learning. If teachers are to inspire students, they need to be inspired themselves. They need to be scholars and model intellectual excitement for their students.

And finally, teachers need to work hard. Great teaching is very hard work. It's intellectually, emotionally, and even physically draining.

Increasingly, I find all the raging discussions about pedagogy somewhat irrelevant. Some great teachers are constructivist, others may use a more traditional approach. Some great teachers may run tightly ordered classrooms with lots of rules, others may run more relaxed classrooms. Some great teachers may engage their students in lots of activities, others may choose more traditional lectures and discussions. Pedagogy, I think, is important, but in the larger scheme of things, it's not what defines a great teacher. The reality is that kids can learn in a wide range of ways, and great teaching can happen in many different forms.

However, what great teachers have in common are the following:

- They care about their students. And their students know it.

- They care about their subjects, and they demonstrate a deep love of learning themselves.

- They work hard. Very, very hard.

And this, to me, I think is the most important and rewarding part of teaching. Great teaching always happens in the context of a strong, supportive, and mutually respectful relationship. When a student knows that a teacher genuinely cares about his or her well-being and learning, then the student becomes deeply invested in the learning process. The more I think about it, the more I think that the teacher-student relationship is, in fact, the most essential pre-requisite for great teaching and deep learning.

I would add that the next essential element is a deep passion for one's subject matter and the teacher's own love of learning. If teachers are to inspire students, they need to be inspired themselves. They need to be scholars and model intellectual excitement for their students.

And finally, teachers need to work hard. Great teaching is very hard work. It's intellectually, emotionally, and even physically draining.

Increasingly, I find all the raging discussions about pedagogy somewhat irrelevant. Some great teachers are constructivist, others may use a more traditional approach. Some great teachers may run tightly ordered classrooms with lots of rules, others may run more relaxed classrooms. Some great teachers may engage their students in lots of activities, others may choose more traditional lectures and discussions. Pedagogy, I think, is important, but in the larger scheme of things, it's not what defines a great teacher. The reality is that kids can learn in a wide range of ways, and great teaching can happen in many different forms.

However, what great teachers have in common are the following:

- They care about their students. And their students know it.

- They care about their subjects, and they demonstrate a deep love of learning themselves.

- They work hard. Very, very hard.

Published on November 02, 2016 20:43

September 5, 2016

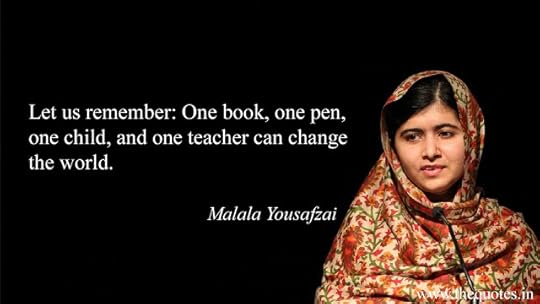

What can one book, one child, one teacher do?

Published on September 05, 2016 06:46

August 20, 2016

WHAT TEACHERS IN SINGAPORE KNOW: 5 LESSONS

Here's a blog post that I recently wrote for Ed Week's Global Learning section. I hope you enjoy it!

And a taster extract:

Lesson #1: Lesson #1: Educators don't need to accommodate short attention spans; we need to train kids to extend their attention spans.

Many of the Singaporean educators I spoke with, particularly elementary school teachers, described the benefits of making young kids complete long and demanding academic tasks. Kids spend hours learning how to write thousands of complex Chinese characters. From grade two onward, they take exams that last for 90 minutes in each of their four major subjects. Yes, that's right: seven year oldscan sit down and concentrate on math for an hour and a half.When I expressed surprise (or shock and horror, to be more precise) over this, parents and educators agreed that Singaporean kids experience significant educational stress because of the exam system, but none of them seemed to think that it was asking too much to make a young child sit down and focus on a single task for an hour and a half. "These tests and activities help train our children to shut out distractions, focus their minds, and concentrate," said one teacher. Said a parent, "It is important to teach our children to focus for extended periods of time. That's a very important skill."

Read the whole article here.

And a taster extract:

Lesson #1: Lesson #1: Educators don't need to accommodate short attention spans; we need to train kids to extend their attention spans.

Many of the Singaporean educators I spoke with, particularly elementary school teachers, described the benefits of making young kids complete long and demanding academic tasks. Kids spend hours learning how to write thousands of complex Chinese characters. From grade two onward, they take exams that last for 90 minutes in each of their four major subjects. Yes, that's right: seven year oldscan sit down and concentrate on math for an hour and a half.When I expressed surprise (or shock and horror, to be more precise) over this, parents and educators agreed that Singaporean kids experience significant educational stress because of the exam system, but none of them seemed to think that it was asking too much to make a young child sit down and focus on a single task for an hour and a half. "These tests and activities help train our children to shut out distractions, focus their minds, and concentrate," said one teacher. Said a parent, "It is important to teach our children to focus for extended periods of time. That's a very important skill."

Read the whole article here.

Published on August 20, 2016 19:31

August 5, 2016

It's not just about IQ and EQ; 21st century kids need CQ

Although it's not cool to admit it, most parents care deeply about their kids' IQ or Intelligence Quotient. I've heard parents of toddlers boast about how "smart" their kids are. (For the record, I think that IQ is a very narrow concept, which doesn't adequately reflect the many different ways in which our children can be intelligent; it does not, for example, measure a child's musical ability or imagination.)

In the last decade, we've also started to care about EQ or Emotional Quotient. Of course, we all want emotionally stable and sensitive kids who get along with others. Without a doubt, our ability to foster and maintain good relationships is key to our happiness and success, personally and professionally.

We're all trying to raise kids who enjoy learning, study hard, relate well to others, and manage their emotions effectively. We know that IQ and EQ matter for professional success, and perhaps (particularly with EQ) for long-term happiness.

Well, guess what? In a global age, we've got a new quotient that is equally important. We've got CQ or Cultural Quotient, a measure of someone's cross-cultural competence, or in other words, their sensitivity to different cultural viewpoints and their ability to work effectively in different cultural contexts.

Consider how global the workplace is these days -- companies are global and workforces are diverse. And opportunities are global too. An Indian graphics designer based in Chennai might do freelance work for a client in France, for example. Our kids need to be equipped to cross cultural borders and navigate a global, intercultural world.

And in addition to the practical implications, CQ can help us create a less prejudiced, kinder and more humane world. And that's very important.

As a global educator who has taught in the US, Singapore, and India, I think that parents can and should consider ways to help a child develop their CQ.

We can help our kids empathize with others from different contexts.

We can help our kids view an issue or story through different cultural lenses and from different perspectives.

We can help our kids understand beliefs, values, norms and conventions of different cultures.

And we can help our kids judge others less and empathize with them more. Ultimately, we want to foster open-mindedness and empathy.

Here are some suggestions:

1. Read multicultural books to your kids when they are young. Here are some options to start with.

2. Buy multicultural books for your kids to read independently as they grow older.

3. Encourage kids to learn more about other cultures through food -- take them to different kinds of restaurants or try cooking different cuisines at home.

4. Encourage kids to learn about the stories and beliefs behind different religions; these foundational stories will help your kids understand other people's world views, and it will help your child develop a respect for other people's beliefs. Here is a post on the impact of foundational stories from around the world.

5. Teach your child a foreign language.

6. Travel -- if you can afford to take your children on trips to different places, this is a great way to help them develop their CQ. If you can't travel to another city or country, then find opportunities within your own city -- perhaps there's a Chinese New Year celebration in your city's Chinatown neighborhood, or perhaps there's a Korean play that your kids can watch in a neighborhood theatre. Seek out these opportunities.

7. Remember that it's important to cross borders and shed prejudices within your own city or country -- for example, Hindu kids in India could learn more about Islam and get to know their Muslim neighbors better. CQ is about crossing borders -- of race, religion, language, culture, and socio-economic status. It's about relating to someone whose context and life is a little different from your own. You don't have to fly across the world to develop CQ -- sometimes, the most difficult borders to cross are the ones right around us.

So parents, don't just focus on IQ and EQ; consider ways to help your child develop his/her CQ as well.

In the last decade, we've also started to care about EQ or Emotional Quotient. Of course, we all want emotionally stable and sensitive kids who get along with others. Without a doubt, our ability to foster and maintain good relationships is key to our happiness and success, personally and professionally.

We're all trying to raise kids who enjoy learning, study hard, relate well to others, and manage their emotions effectively. We know that IQ and EQ matter for professional success, and perhaps (particularly with EQ) for long-term happiness.

Well, guess what? In a global age, we've got a new quotient that is equally important. We've got CQ or Cultural Quotient, a measure of someone's cross-cultural competence, or in other words, their sensitivity to different cultural viewpoints and their ability to work effectively in different cultural contexts.

Consider how global the workplace is these days -- companies are global and workforces are diverse. And opportunities are global too. An Indian graphics designer based in Chennai might do freelance work for a client in France, for example. Our kids need to be equipped to cross cultural borders and navigate a global, intercultural world.

And in addition to the practical implications, CQ can help us create a less prejudiced, kinder and more humane world. And that's very important.

As a global educator who has taught in the US, Singapore, and India, I think that parents can and should consider ways to help a child develop their CQ.

We can help our kids empathize with others from different contexts.

We can help our kids view an issue or story through different cultural lenses and from different perspectives.

We can help our kids understand beliefs, values, norms and conventions of different cultures.

And we can help our kids judge others less and empathize with them more. Ultimately, we want to foster open-mindedness and empathy.

Here are some suggestions:

1. Read multicultural books to your kids when they are young. Here are some options to start with.

2. Buy multicultural books for your kids to read independently as they grow older.

3. Encourage kids to learn more about other cultures through food -- take them to different kinds of restaurants or try cooking different cuisines at home.

4. Encourage kids to learn about the stories and beliefs behind different religions; these foundational stories will help your kids understand other people's world views, and it will help your child develop a respect for other people's beliefs. Here is a post on the impact of foundational stories from around the world.

5. Teach your child a foreign language.

6. Travel -- if you can afford to take your children on trips to different places, this is a great way to help them develop their CQ. If you can't travel to another city or country, then find opportunities within your own city -- perhaps there's a Chinese New Year celebration in your city's Chinatown neighborhood, or perhaps there's a Korean play that your kids can watch in a neighborhood theatre. Seek out these opportunities.

7. Remember that it's important to cross borders and shed prejudices within your own city or country -- for example, Hindu kids in India could learn more about Islam and get to know their Muslim neighbors better. CQ is about crossing borders -- of race, religion, language, culture, and socio-economic status. It's about relating to someone whose context and life is a little different from your own. You don't have to fly across the world to develop CQ -- sometimes, the most difficult borders to cross are the ones right around us.

So parents, don't just focus on IQ and EQ; consider ways to help your child develop his/her CQ as well.

Published on August 05, 2016 18:45

August 4, 2016

7 Life Lessons: A Letter to My Students

Here's a letter I wrote to for my students who graduated. I miss them!

Life’s Lessons : A letter to my students

Graduations remind me of diving boards: parents and teachers become spectators, waiting to see each student jump, spring, and dive into “adulthood” and the “real world.” And we teachers believe, perhaps naively, that we’ve prepared you for the real world. We’ve given you formulas and algorithms, we’ve introduced you to Orwell and Bronte, we’ve taught you about wars and revolutions, we’ve taught you to read, write, speak, and sing…. We’ve prepared you for that dive.

But in reality, there isn’t a dive that sends you into the pool of adulthood. Growing up isn’t as sudden or as simple as that. It’s a life-long journey, and for the most part, you swim along just as you did in high school. But -- perhaps not unlike the way your heart sank when you bombed a test, or the way you cried when your friend betrayed you, or the way you tossed in bed wondering if your crush would ever be reciprocated -- you might sometimes feel as though you can’t swim fast enough, or the pool seems too long and too deep to navigate, or you lose your way and hit your head on the pool walls, and ouch, it hurts.

As you navigate the complex world of independence and adulthood, I’d like to share with you some of the lessons that I learned along the way. These lessons may or may not resonate with you – but I offer them to you anyways, with all my best wishes and best intentions.

I have learned to empathize more and judge less. Everyone has challenges of some kind – sometimes heartbreaking challenges – so judge people less, empathize with them more, and be kind, be kind, be kind.

I have learned that forgiveness is always better than anger. Forgiveness is liberating, but anger is imprisoning.

As the poet Jallaludin Rumi reminds us,“Anger may taste sweet, but it kills.Don’t become its victim.You need humility to climb to freedom.”

I have learned that when we skin our knees on the sidewalks of life*, we bleed, whether we’re rich or poor, gay or straight, Jew or Christian, Hindu or Muslim, Black or White, Indian or Chinese. I hope that as you venture into a world where people define themselves by how they are different from others, often with violence and hatred, you will remember our common humanity.

I have learned that there is value in sticking things out: sticking out relationships, jobs, places, and projects. In a world with so much mobility and so many choices, this can be harder than it seems. Continuity and commitment, endurance and perseverance, or “grit” -- to use the word of the day -- all matter. We need our roots as much as we need our wings.

I have learned that you’re never quite prepared for those moments when adversity hits – when the pool feels too deep and the currents too strong, when you feel as though you may drown, or worse, you yearn to drown, when you are hit with loss or betrayal or failure or terrifying fear. But, prepared or not, you have to keep swimming and stay strong. Don’t fall apart when life gets tough; be resilient and brave.

I have learned that it is important to nurture relationships – to make an effort with people you care about and people you work with. Stay close to your families, nurture your friendships, and cultivate your professional networks. Give gifts, attend your friends’ weddings (even if they’re far away and it’s inconvenient), go to their baby showers, be there for them when things go wrong, reach out often and stay in touch. In a globalized world where people are scattered everywhere, like raindrops, relationships may start to feel ephemeral and transient. Make the effort; you will be grateful for all those relationships – familial, personal, and professional -- down the road.

I have learned that it is important to cultivate your own intellectual life. Your mind is rich and wonderful – nourish it and care for it. Knowledge and imagination, books and ideas, can enrich and sustain you. Like fire and energy, like a bird in flight and a mountain climber scaling heights, the life of the mind is thrilling. Read widely, read deeply, and read often.

Take care of yourselves always.

Ms.T

* "when we skin our knees on the sidewalks of life, we bleed" - Taken from Billy Collins' wonderful poem "On Turning Ten."

Life’s Lessons : A letter to my students

Graduations remind me of diving boards: parents and teachers become spectators, waiting to see each student jump, spring, and dive into “adulthood” and the “real world.” And we teachers believe, perhaps naively, that we’ve prepared you for the real world. We’ve given you formulas and algorithms, we’ve introduced you to Orwell and Bronte, we’ve taught you about wars and revolutions, we’ve taught you to read, write, speak, and sing…. We’ve prepared you for that dive.

But in reality, there isn’t a dive that sends you into the pool of adulthood. Growing up isn’t as sudden or as simple as that. It’s a life-long journey, and for the most part, you swim along just as you did in high school. But -- perhaps not unlike the way your heart sank when you bombed a test, or the way you cried when your friend betrayed you, or the way you tossed in bed wondering if your crush would ever be reciprocated -- you might sometimes feel as though you can’t swim fast enough, or the pool seems too long and too deep to navigate, or you lose your way and hit your head on the pool walls, and ouch, it hurts.

As you navigate the complex world of independence and adulthood, I’d like to share with you some of the lessons that I learned along the way. These lessons may or may not resonate with you – but I offer them to you anyways, with all my best wishes and best intentions.

I have learned to empathize more and judge less. Everyone has challenges of some kind – sometimes heartbreaking challenges – so judge people less, empathize with them more, and be kind, be kind, be kind.

I have learned that forgiveness is always better than anger. Forgiveness is liberating, but anger is imprisoning.

As the poet Jallaludin Rumi reminds us,“Anger may taste sweet, but it kills.Don’t become its victim.You need humility to climb to freedom.”

I have learned that when we skin our knees on the sidewalks of life*, we bleed, whether we’re rich or poor, gay or straight, Jew or Christian, Hindu or Muslim, Black or White, Indian or Chinese. I hope that as you venture into a world where people define themselves by how they are different from others, often with violence and hatred, you will remember our common humanity.

I have learned that there is value in sticking things out: sticking out relationships, jobs, places, and projects. In a world with so much mobility and so many choices, this can be harder than it seems. Continuity and commitment, endurance and perseverance, or “grit” -- to use the word of the day -- all matter. We need our roots as much as we need our wings.

I have learned that you’re never quite prepared for those moments when adversity hits – when the pool feels too deep and the currents too strong, when you feel as though you may drown, or worse, you yearn to drown, when you are hit with loss or betrayal or failure or terrifying fear. But, prepared or not, you have to keep swimming and stay strong. Don’t fall apart when life gets tough; be resilient and brave.

I have learned that it is important to nurture relationships – to make an effort with people you care about and people you work with. Stay close to your families, nurture your friendships, and cultivate your professional networks. Give gifts, attend your friends’ weddings (even if they’re far away and it’s inconvenient), go to their baby showers, be there for them when things go wrong, reach out often and stay in touch. In a globalized world where people are scattered everywhere, like raindrops, relationships may start to feel ephemeral and transient. Make the effort; you will be grateful for all those relationships – familial, personal, and professional -- down the road.

I have learned that it is important to cultivate your own intellectual life. Your mind is rich and wonderful – nourish it and care for it. Knowledge and imagination, books and ideas, can enrich and sustain you. Like fire and energy, like a bird in flight and a mountain climber scaling heights, the life of the mind is thrilling. Read widely, read deeply, and read often.

Take care of yourselves always.

Ms.T

* "when we skin our knees on the sidewalks of life, we bleed" - Taken from Billy Collins' wonderful poem "On Turning Ten."

Published on August 04, 2016 19:02

August 1, 2016

5 Back To School Resolutions

Most people make their new year's resolutions on January 1st. But not me. My mind is so attuned to an academic calendar that my year begins in August. So, it's time for some back-to-school resolutions.

To start with, I've got some parenting resolutions:

#1: Remember that my daughter is only 8!

Why is it so hard to give a second child the same attention that we give our first? When my son was 8, I spent lots of time helping him manage his time and organize all his materials. I checked his homework and made him redo drafts of sloppy work. I want to make sure that I do the same thing for my daughter, despite the fact that I'm feeling a little burnt out and exhausted. She still needs lots of help with organization and skills, and I need to make time for her.

Fortunately, my son, who is now starting grade 6, has developed good homework habits, so I think I will encourage him to work more independently while I focus my attention on helping my daughter.

#2: Remember how important nature and free-play are, even for older kids.

As my kids grow older, I find that the pressures around them seem to grow too. There's more homework, there are so many options for scheduled activities at school, and time seems to be so limited. However, I want to make sure that I still leave lots of time for my kids to play outside with their friends and to read for pleasure. I think that "a green-hour" (ie time in nature)is SO important for kids. So, as my kids choose their activities and plan their weeks, I'm going to encourage them to sign up for fewer activities and preserve some time to play freely outdoors and to read for pleasure.

#3: Put away my laptop and phone, and engage more directly with my kids.

Lately I've been finding myself becoming increasingly addicted to my devices. And that scares me. Last week I snapped at my daughter because she wanted to read with me, but I was too busy checking my facebook account. Now, you tell me what's more important?

So my resolution this year is to create "No Tech Zones" for myself. When I come home from work, I will have a no-tech hour, where I can engage with my children with no distractions. And similarly, from dinner till bedtime will be a "no-tech zone." We'll all focus on real human engagement -- something that's becoming increasingly endangered not just in schools but in homes.

#4: Focus on Wellness.

By the end of the last school year, I was an exhausted mess. My back constantly hurt, I was taking way too many advils for headaches, and I found myself feeling increasingly cranky. Let's face it: teaching is one of the most demanding and exhausting professions in the world. And adding parenting and book promotion to the mix, makes my life even more exhausting.

So this year, I'm going to schedule in the following:

- a morning yoga/stretching/mindfulness routine (I think I might add some brief 5 minute stretch and mindfulness breaks into my classroom routines as well.)

- Long walks or runs in the evening, when my kids are playing outside. I need a green hour just as much as they do.

- And more time for my own independent reading at nights and on weekends. Nothing relaxes and revives me like a good book!

#5: Enjoy the year!

Often, I think that I am so lucky. I love my job; I teach fantastic kids. I love being a mom and watching my own kids grow. And I enjoy all the writing and reading I do. I want to remind myself to slow down a bit and enjoy all the kids whom I work with and all the wonderful bits and pieces of my life.

To start with, I've got some parenting resolutions:

#1: Remember that my daughter is only 8!

Why is it so hard to give a second child the same attention that we give our first? When my son was 8, I spent lots of time helping him manage his time and organize all his materials. I checked his homework and made him redo drafts of sloppy work. I want to make sure that I do the same thing for my daughter, despite the fact that I'm feeling a little burnt out and exhausted. She still needs lots of help with organization and skills, and I need to make time for her.

Fortunately, my son, who is now starting grade 6, has developed good homework habits, so I think I will encourage him to work more independently while I focus my attention on helping my daughter.

#2: Remember how important nature and free-play are, even for older kids.

As my kids grow older, I find that the pressures around them seem to grow too. There's more homework, there are so many options for scheduled activities at school, and time seems to be so limited. However, I want to make sure that I still leave lots of time for my kids to play outside with their friends and to read for pleasure. I think that "a green-hour" (ie time in nature)is SO important for kids. So, as my kids choose their activities and plan their weeks, I'm going to encourage them to sign up for fewer activities and preserve some time to play freely outdoors and to read for pleasure.

#3: Put away my laptop and phone, and engage more directly with my kids.

Lately I've been finding myself becoming increasingly addicted to my devices. And that scares me. Last week I snapped at my daughter because she wanted to read with me, but I was too busy checking my facebook account. Now, you tell me what's more important?

So my resolution this year is to create "No Tech Zones" for myself. When I come home from work, I will have a no-tech hour, where I can engage with my children with no distractions. And similarly, from dinner till bedtime will be a "no-tech zone." We'll all focus on real human engagement -- something that's becoming increasingly endangered not just in schools but in homes.

#4: Focus on Wellness.

By the end of the last school year, I was an exhausted mess. My back constantly hurt, I was taking way too many advils for headaches, and I found myself feeling increasingly cranky. Let's face it: teaching is one of the most demanding and exhausting professions in the world. And adding parenting and book promotion to the mix, makes my life even more exhausting.

So this year, I'm going to schedule in the following:

- a morning yoga/stretching/mindfulness routine (I think I might add some brief 5 minute stretch and mindfulness breaks into my classroom routines as well.)

- Long walks or runs in the evening, when my kids are playing outside. I need a green hour just as much as they do.

- And more time for my own independent reading at nights and on weekends. Nothing relaxes and revives me like a good book!

#5: Enjoy the year!

Often, I think that I am so lucky. I love my job; I teach fantastic kids. I love being a mom and watching my own kids grow. And I enjoy all the writing and reading I do. I want to remind myself to slow down a bit and enjoy all the kids whom I work with and all the wonderful bits and pieces of my life.

Published on August 01, 2016 21:19

June 21, 2016

Summer Freedom!

Today is the last day of this academic year. As the summer stretches out ahead of me, I feel tremendous excitement and relief.

Now, don’t get me wrong. I love my job, and I’m a big proponent of hard work, schoolwork, homework, and all kinds of work. But by the end of the academic year, I’m totally and completely worn out. Schools are possibly the most structured and disciplined places on our planet. During the school year, faculty and students alike are governed by schedules, timetables, and syllabi. We think in terms of hour-long blocks that end with a loud bell. Our thoughts are always, necessarily, fragmented. Just as we’re working through a particularly difficult piece of poetry, the bell rings. All of a sudden, students have to march to a Chemistry class and wrestle with the periodic table, while I have to run to another class and teach a totally different text. And then, all year long, students and faculty alike march from one set of assignments to another, from one set of assessments to another, from one reporting period to another. Much as I love school, I do find the degree of structure overwhelming.

So, summer is a welcome break. As I contemplate two months of freedom, I realize how important unstructured time is for all of us: faculty and students alike. While structured learning is very important, a whole different kind of learning takes place in the summer. We can spend a morning immersed in a book, with no bell to interrupt the experience. We can immerse ourselves in a particular project or learning experience without the constraints and demands of school. We can play! Play with ideas, play with words, play in the sand and play at the beach. We can engage in an activity for the pure pleasure of it, without worrying about external assessments and judgments. We can do what we love, what we want, instead of being forced to do what everyone else (administrators, exam boards, parents, teachers) tell us to do. Oh, the joy of summer!

Unstructured time is, I think, critical for deep thinking and creativity. All people, teachers and students alike, need long stretches of unstructured time to imagine, dream, and think. It is this mental space and time that allows us to be reflective and creative. Additionally, we all need downtime to recharge our batteries. And, very importantly, we all need time outdoors, time to connect with nature and our physical environment. The beauty of the academic year is that we have this time built into every year. Every academic year begins anew in August, with renewed vigor and intensity. And then every academic year winds down in June, giving way to the luxury and freedom of summer.

Published on June 21, 2016 19:14