Michael Gouker's Blog

March 27, 2021

Jabbed (Mar 2021, two months before I expected)

Ha ha. Charade in a graveyard mall

People

Crowds of people

Virus murdering Mercury jab.

Oh, you are so near.

I want to know you better.

I want to plumb and close your depths,

Feel your latitude,

Touch you because now I can

inhabit your skin

Let us trade lies and proximity

All that we love, all we disdain:

Giant gumdrop drinking fountains

Handfuls of rock candy mountains

Sustenance from our very marrows

Juice of our juice in a vial

Disease vector have-a-nice-day jab

beyond this lonely desert stretch

people flower, rows and columns

burbling human bouillabaisse

surface still, sound incandescent

Desire. Delight.

soul-dragged, decadent, and oh so jabbed.

Your useless lips too cracked to open

words too mean to say

words mean too much to say

words feed empty air

you are so hungry, so lonely, but here you are

Jabbed.

Oh my! Did I jab a skewed pattern in lipstick

There on your forehead counter—

Sixteen skewered by a wisp of smoke?

Stiffen up.

Yes you believe in my make believe.

Love and suffer more.

And I marvel at my lips for milking your soul

Jabbing it dry.

So jabbed now

You are so broken and so jabbed

Pumping flaccid bicycle tires

That nozzle so deep I have to tease it out

What is that spatchcocked against my teeth?

Sphinx shining with sniffling vindication

Strikes a pose but that sucker can pump

Back and forth like jerking it off

And you laugh because you are jabbed too

In Celebration of My Jabbing (Mar 2021, two months before I expected)

"Jabbed"

Ha ha. Charade in a graveyard mall

People

Crowds of people

Liquid antiviral Mercury jab.

Oh, you are so near

I want to know you.

I want to plumb and close your depths,

Feel your latitude,

Touch you because now I can

inhabit your skin

Let us trade lies and proximity

All that we love, all we disdain:

Giant gumdrop drinking fountains

Handfuls of rock candy mountains

Sustenance from our very marrows

Juice of our juice in a vial

Disease vector have-a-nice-day jab

beyond this lonely desert stretch

people flower, rows and columns

the burbling of human bouillabaisse

surface pale, sound incandescent

Desire. Delight.

soul-dragged, decadent, and oh so jabbed.

Your useless lips too cracked to open

words too mean to say

words mean too much to say

words feed empty air

you are so hungry, so lonely, but here you are

Jabbed.

Oh my! Did I jab a skewed pattern in lipstick

There on your forehead counter—

Sixteen skewered by a wisp of smoke?

Stiffen up.

Yes you believe in my make believe.

Love and suffer more.

And I marvel at my lips for milking your soul

Jabbing it dry.

So jabbed now

You are so broken and so jabbed

Pumping flaccid bicycle tires

That nozzle so deep I have to tease it out

What is that spatchcocked against my teeth?

Sphinx shining with sniffling vindication

Strikes a pose but that sucker can pump

Back and forth like jerking it off

And you laugh because you are jabbed too

January 20, 2021

Amanda Gorman is a rock star poet.

Mr. President, Dr. Biden, Madam Vice President, Mr. Emhoff, Americans and the world: (ed. my stanzas and line breaks which are probably not right)

When day comes, we ask ourselves

Where can we find light in this never ending shade?

The loss we carry, a sea we must wade.

We braved the belly of the beast.

We've learned that quiet isn't always peace

And the norms and notions of what "just is," isn't always justice.

And yet the dawn is hours before we knew it,

Somehow we do it,

Somehow we’ve weathered and witnessed

A nation that isn't broken but simply unfinished.

We, the successors of a country and a time,

Where a skinny black girl descended from slaves

And raised by a single mother can dream of becoming president,

Only to find herself reciting for one.

And yes, we are far from polished, far from pristine,

But that doesn't mean we are striving to form a union that is perfect.

We are striving to forge our union with purpose,

To compose a country committed

To all cultures, colors, characters, and conditions of man.

And so we lift our gazes

Not to what stands between us

But what stands before us.

We close the divide because we know to put our future first

We must first put our differences aside.

We lay down our arms

So we can reach out our arms to one another

We seek harm to none and harmony for all.

Let the globe--if nothing else--say this is true,

That even as we grieved, we grew.

That even as we hurt, we hoped.

That even as we tired, we tried.

That we’ll forever be tied together,

Victorious

Not because we will never again know defeat,

But because we will never again sow division.

Scripture tells us to envision

That everyone shall sit under their own vine and fig tree,

And no one shall make them afraid.

If we’re to live up to our own time,

Then victory won't lighten the blade but in all the bridges we've made,

That is the promise to glade,

The hill we climb if only we dare.

It's because being American is more than a pride we inherit.

It's the past we stepped into and how we repair it.

We've seen a force that would shatter our nation rather than share it,

Would destroy our country

If it meant delaying democracy.

And this effort very nearly succeeded.

But while democracy can be periodically delayed,

It can never be permanently defeated.

In this truth, in this faith, we trust.

For while we have our eyes on the future,

History has its eyes on us.

This is the era of just redemption.

We feared -- at its deception.

We did not feel prepared to be

The heirs of such a terrifying hour,

But within it we found the power

To author a new chapter,

To offer hope and laughter to ourselves.

So, while once we asked, “how could we possibly prevail over catastrophe?”,

Now we assert, “how could catastrophe possibly prevail over us?”

We will not march back to what was,

But move to what shall be,

A country that is bruised but whole,

Benevolent but bold,

Fierce and free.

We will not be turned around

Or interrupted by intimidation.

Because we know our inaction and inertia will be

The inheritance of the next generation.

Our blunders become their burdens.

But one thing is certain.

If we merge mercy with might and might with right,

Then love becomes our legacy and change,

Our children's birth right.

So let us leave behind a country better than one we were left with,

Every breath from my bronze pounded chest,

We will raise this wounded world into a wondrous one.

We will rise through the gold-limbed hills in the west,

We will rise from the windswept northeast where our forefathers first realized revolution.

We will rise from the lake-rimmed cities of the Midwestern states.

We will rise from the sun-baked South.

We will rebuild, reconcile, and recover,

In every known nook of our nation,

In every corner called our country,

Our people diverse and beautiful will emerge battered and beautiful.

When day comes, we step out of the shade, aflame and unafraid.

The new dawn blooms as we free it

For there is always light if only we're brave enough to see it,

If only we're brave enough to be it

---

You can preorder her book on Amazon here: (available on 9/21/21): link to amazon for hard cover version.

November 4, 2020

My impression of NK Jemisin's World Building in The Hundred Thousand Kingdoms.

N.K. Jemisin brings many tools to her world-building, especially a focus on how power is distributed and contested by the clans of her peoples. The manifestation of power is evident throughout The Hundred Thousand Kingdoms, but one illustration in particular is the division of nobles in the Consortium. Yeine comments on the inequity of their distribution, citing as an example that the city of Sky (including the palace) has one delegate, whereas the entirety of the High North continent has only two. A delegate’s task is “to speak for themselves and their neighboring lands,” but one fundamental question is whether the needs of these conquered nations can be accurately expressed in the only language of the Consortium: Senmite, the language of the Amn that “the Arameri had imposed… on the world” (ch 6).

Jemisin mentions a number of peoples and languages in this first book of The Inheritance Trilogy including Nirva (a common tongue of the High North), the aforementioned Senmite, Teman, Kenti, Darren, and Mencheyev. It is unclear whether other peoples mentioned (like the Min, Ghor, Uthre, or Irti—these last two are related to the Ken) have their own languages. There is a parallel between Darr and the Amn, in that both peoples conquered other tribes; however, while the Amn forced Senmite on the vanquished foes, Darr did not. The common language of the north is not Darren, but Nirva. The characterization of language as an ethnic weapon

From a world-building perspective, what is most remarkable to me is how Jemisin crafts such a rich universe from sparse material. Jemisin collected her development notes in a Non-Wiki (see links below), which includes descriptions of characters (WARNING: There are spoilers for books 2 & 3), races, and locations, along with a timeline (under “Miscellany.”) Darre and Amn have adequate descriptions, but most mortal races garner only a few sentences. The nation of Tokland has seven words. The listing for Uthre and Irti only mention the “peaceful annexation.” In her conception of this universe, Jemisin’s efficiency reveals her storytelling’s reals foci are the interactions of the gods and how they affect mortals.

Mortals appropriate the language of the gods to cast spells that change reality in small ways. The specialists in this field are called scriveners, represented in The Hundred Thousand Kingdoms by the character Viraine (who is secretly also Ytempas, the inventor of language). The divine language “allows the conceptualization of the impossible,” and scriveners learn several mortal tongues first as children to “help[] them understand the flexibility of language and of the mind itself” (ch. 11). The dependency between reality and language is reminiscent of work by linguist Ferdinand de Saussure, who developed a discourse for the relationship between names and objects, and literary theorist Roland Barthes, who proposes that the “signifier comes before the signified,” that in essence all the signified “is socially constructed by its circulation between the user and the consumer of the sign,” and that, therefore, “language determines the order of the world, not the other way around” (Finnison 71). Seen this way, the magic of Jemisin’s god language might be seen as a concretization of abstract concepts, a reification, and the exchange of one reality for another relies on the mere acceptance of the believer.

At the end of the novel, the (Yeine/Enefa as I) narrator disabuses us of the necessity of language in this equation. While the magical transformation of reality “may be approximate[d]… through the use [by mortals] of the gods’ language”, Nahadoth and Yeine do not require such crude artifices (glossary entry: “Magic”). In the confrontation with Ytempas, the narrator discloses that “Language had been his invention; we had never really needed words” (ch 29). Nahadoth then reshapes reality itself, and then there is an apparent contradiction, for it is stated “we had never really needed a separate language, either; any tongue would do, as long as one of us spoke the words,” which seems to counter the notion that “we had never really needed words;” however, language and words are not equivalent. It is confusing though.

What is not confusing, however, is how Jemisin uses stammering in the novel to depict the breadth of the gap of power. Three characters stutter: Nahadoth (when recovering from pain), T’vril (while making a clumsy attempt at seduction), and (most prominently) Yeine, who stammers (both in her language and Senmite) eight times: “S-top!” (ch 5), “P-poison?” (ch 10), “A-all that surprises me are… the lies I’ve been told” (ch 10), (N-no) (ch 10), “Y-you are welcome in my family’s home” (ch 16), “N-nothing” (ch 17, when T’vril is about to offer sex between friends), “H-he could…” (ch 18), and above all, “R-Relad” in chapter 27. The stammer softens a warrior character who is impulsive and direct, but it also reveals the stress that her lack of power imposes upon her. Jemisin's use of stammer attunes the reader to perceive Yeine as weaker before the gods, even though (as we later learn) she is a vessel for one of the universe's most powerful vehicles.

Anyway, it is very interesting to see how Jemisin uses language to reflect upon the distribution of power.

Works Cited:

Finnison, Ari. “‘Language on Holiday:’ Wittgenstein and the Language-Reality Gap in Historical Narratives.” The Corvette. Volume 5. Spring 2018. University of Victoria. Undergraduate History Journal. https://journals.uvic.ca/index.php/corvette/article/view/19007 (Links to an external site.)

Jemisin, N.K. The Hundred Thousand Kingdoms. Orbit Books. 2010.

Jemisin, N.K. The Inheritance Trilogy Non-Wiki. http://nkjemisin.com/the-inheritance-trilogy-non-wiki/ (Links to an external site.)

Note: I intentionally left out the use of the imperative in the Arameri commands of the Enefadah, because I wish to address this as part of my second essay about power and slavery.

November 3, 2020

I Embrace the Keenest Foil

My second book about Coda also stars a character of fluid sexuality, Saxi, streetwise, dangerous, and gently murderous. This is for NaNoWriMo and I'm writing 65000 words. Here's the progress so far:

So the idea is to build up to it. I did this because I remember what happened to me in 2016, the last presidential election. I got knocked on my ass and had to play catch up. This time I am planning for it, so if it doesn't happen, it will just be easier.

Right now, I'm just in front of where I need to be. If all goes well (for all of us), tomorrow I'll be pushing like crazy. :-)

October 28, 2020

The Revisioners by Margaret Wilkerson SextonMy rating: 5 ...

The Revisioners by Margaret Wilkerson Sexton

The Revisioners by Margaret Wilkerson SextonMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

A heartfelt intergenerational journey across two centuries of American history told from the perspective of two women, Ava & Josephine, whose families are victims of racism. The author uses the term "recycled racism" to describe their suffering, and it's precise. There are three narratives. Josephine is the daughter of a family in the antebellum South who are escaping slavery at Wildwood. She is also much later the matriarch of a family whose white neighbor wishes to befriend her (before she gets all kkklanish and sees Josephine as a beggar at the door). Ava, some 90 years later, also must dodge the strange demands of her white racist grandmother.

Sexton does an amazing job of tracing the parallels of the paths of these two women. The prose combines pure poetry with a coarse heartbreaking tone that is soul-crushing. The characters become your old friends. It is sometimes hard going (because you know the doom is growing every page you turn) but every turn is worth it.

View all my reviews

July 22, 2020

“That Bearing Boughs May Live”: What Did King Richard II Author for the World?

It is 2020, the Summer of #BlackLivesMatter, and this week, in a moment of uncommon synchronicity, the theater company who would (in another non-Covid-19 world) be performing at the Delacorte Theater in Central Park are instead presenting King Richard II to homebound Internet streamers. Today’s resonance of the Bard’s words testifies not only to word craft but also to boldness, for King Richard II articulates revolution against repressive political and theological systems. Moreover, its nuanced language cultivates sympathy, allowing us, in the words of Shakespeare scholar Ayanna Thompson, “to grieve the loss of something even if we think it’s the right thing to get rid of,” as pertinent to “Defund the Police” protesters as their counterparts in 1776 America, 1789 Paris, 1791 Haiti, and 1917 Moscow (The Public). King Richard II asks its audience to consider the legitimacy of overthrowing a Pope-anointed monarch without damning the usurper’s mortal soul, and within the play’s text, King Richard II authors his downfall and plots a guide for future revolutionaries to follow.

Nigel Saul details the murderous “scheme… hatched by Richard and his courtiers to engineer the overthrow of Lancastrian power” before Bolingbroke’s succession, a prospect that “filled [the King] with alarm” (Saul 38-39). Shakespeare’s echoes the King’s duplicity when he tells Bushy, Green, and Aumerle that “The lining of [John of Gaunt’s] coffers shall make coats/To deck our soldiers for these Irish wars./Come, gentlemen, let's all go visit him:/Pray God we may make haste, and come too late!” (Shakespeare 1.4.62-64). The reckoning comes when King Richard II learns, upon returning from Ireland, the banished Bolingbroke is back to claim his inheritance and encircled by allies. Richard, still kingly, proclaims “Not all the water in the rough rude sea/Can wash the balm off from an anointed king;/The breath of worldly men cannot depose/The deputy elected by the Lord” (Shakespeare 3.2.54-57). Kantorowicz describes this moment as a portrayal of “the indelible character of the king’s body politic, god-like or angel-like” (27), however a string of “tidings of calamity” (Shakespeare 3.2.105) shake King Richard II to his core, a transformation from exaltation to “a [pale] nothing, a nomen” (Kantorowicz 29). Faced with mass desertions, the king appears to lose not only his authority but his very identity. “How can you say to me, I am a king?” (3.2.177) he asks his loyalists, and then bids them to “Discharge my followers: let them hence away,/From Richard’s night to Bolingbroke’s fair day,” seemingly defeated even before Bolingbroke challenges him, a self-subversion that becomes the theme of the rest of the story (3.2.218). Indeed, as Pye states, “the central question in the drama is whether sovereignty can prove itself by mastering its own subversion” (577).

What follows is a Passion play, complete with references to crosses, Judases, and Pilates, culminating in a scene where the now self-deposed Richard II defies “his onlookers to read the moment of his undoing” and dashes a mirror to the ground (578). This pivotal moment marks the end of King Richard II’s dual personhood, and the king, first “immortal because legally he can never die” (Kantorowicz 4) becomes “the king that… suffers death more cruelly than other mortals” (30). This transformation from a conniving leader to a pitiable creature is dramatic, engaging, and evocative. He seems to wish to dispense with his crown like an unused dropped gage. A poignant moment of abject misery occurs when Richard, bereft of his kingship and, from his perspective, his very identity, asks “What more remains?” (4.1.222). In response, because annihilation of self is apparently not enough, Northumberland charges his former sovereign with crimes like those Nigel Saul relates, accusations the king cannot read through tear-blinded eyes, but those sins spawn a measure of doubt, and Pye suggests a “more extravagant possibility that [the king’s] grief, and his crime, are not his own” (581). Pye argues the king is “dispossessed of his shame,” because through self-deposition, Richard II has been “rob[bed]… of the power to claim the guilt as his own”; Pye labels this dispossession the “perfect crime[,] one that elides itself as it is committed” (591). It is a particularly vexing danger overshadowing every revolutionary’s intent: Even if oppressive leaders, confronted with their misdeeds, peacefully surrender power, the true oppressor may be the society that created them, and, thus, the same fate may befall the revolutionaries.

In any case, responsibility for King Richard II’s downfall appears to be a legal tautology in English law. Kantorowicz, quoting Sir William Blackstone, explains a king “’is not only incapable of doing wrong, but even of thinking wrong: he can never mean to do an improper thing: in him is no folly or weakness’” (Kantorowicz 4). Thus, only King Richard II could author his downfall. A more interesting question is how the play has influenced history, and while it is reckless to exaggerate its impact on revolution, supporters of Robert Devereux, the Earl of Essex, did pay Shakespeare’s company to perform the play on February, 7, 1601, the day before a planned rebellion, a bald attempt to, in the words of Francis Bacon, “bring from the Stage to State” (Albright 709). Unfortunately for the earl, Queen Elizabeth I also asked for an encore performance the day of his execution.

(583 original words, excluding these.)

Works Cited

Albright, Evelyn May. “Shakespeare's Richard II, Hayward's History of Henry IV, and the Essex Conspiracy.” PMLA. Modern Language Association, Sep. 1931, Vol. 46, No. 3, p. 709.

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.com/stable/457855

Kantorowicz, Ernst. “Shakespeare: King Richard II.” The King's Two Bodies: A Study in Mediaeval Political Theology. Princeton University Press, 2016, pp. 24-41.[image error]

Pye, Christopher. “The Betrayal of the Gaze: Theatricality and Power in Shakespeare's Richard II.” ELH, vol. 55, no. 3, 1988, pp. 575-598.

Shakespeare, William. “Hamlet.” The Norton Shakespeare: The Essential Plays/Sonnets, edited by Stephen Greenblatt et al. 3rd Edition. W.W. Norton & Company. 2016.

The Public. Richard II. https://publictheater.org/productions/season/1920/richard-ii/

Ayanna Thompson’s interview is in the first segment of the four.

"Foul as Vulcan's Stithy": A Different Perspective on “The Mousetrap” and Its Intended Audience

William Shakespeare’s Hamlet illustrates how the dead can drive the living to fulfill their unfinished business. Armed with secrets of his murdered father’s specter, Hamlet conceives “The Mousetrap,” a play within a play, its stated purpose—"to catch the conscience of the king,” his uncle Claudius—though Hamlet himself sabotages his gambit during the performance (Shakespeare 2.2.606). This alone, however, should not measure its success, for Hamlet’s audience is wider. Queen Gertrude is also targeted by the piece. Indeed, she is the prince’s true focus, and there is no question here of Hamlet’s glorious success, the ramifications of which condemn them all to tragic death.

Though Hamlet mourns his father, he is more disturbed by Gertrude’s choice to speedily remarry his uncle. Maquerlot proposes Hamlet’s “disgust at the world” is “generated by disgust at his mother” (98). Hamlet’s revulsion is most dramatically demonstrated when he requests “a passionate speech” he heard performed once by a player and then prompts him by reciting fifteen lines of Aeneas' tale of King Priam’s slaughter (Shakespeare 2.2.432-436). The story finishes with Queen Hecuba’s grief at her husband’s death, declaring “The instant burst of clamor that she made… Would have made milch the burning eyes of heaven” (2.2.515-517). The underlying message is to contrast Queen Hecuba’s behavior with Gertrude’s. That Hamlet had memorized these lines speaks to the depths of his fixation.

Because the disclosure of Claudius’s crime comes through supernatural means, Hamlet’s knowledge is of limited use. The ghost stirs Hamlet’s wrath, calling Claudius “that incestuous, that adulterate beast,” who used his “wit and gifts… to seduce [and win] to his shameful lust/The will of [the] most seeming-virtuous queen” (Shakespeare 1.5.42-46). This charge of adultery invites differing interpretations ranging from the ghost still considering Gertrude its possession to a denunciation of sexual liaisons predating the murder. The ghost is also unreliable. When it appears in Queen Gertrude’s private chamber, for example, she neither sees nor hears it. Derrida discusses Hamlet’s ghost rules in depth, coining the term “hauntology” to describe how the “altogether other” interact with the living (11). “What seems almost impossible,” Derrida says, “is to speak always to the specter, to seek to the specter, to speak with it, [or] especially to make or let a spirit speak,” and this hypothesis is reinforced when only Hamlet hears its claims (11).

Faced with such a fickle witness, Hamlet chooses “The Mousetrap,” bidding Horatio to “Observe mine uncle” for guilt, though likely he has another purpose (Shakespeare 3.2.80). Consider that Hamlet does nothing with the information gleaned. Moreover, Hamlet appears more affected than Claudius by the play. Before leaving in a warranted huff, Claudius’s only lines are “Have you heard the argument? Is there no offense in't?” (3.2.232-233) and “What do you call the play?” (3.2.236). To these two reasonable questions, Hamlet spews about “poison in jest” (3.2.234) and “Let the galled jade winch, our/withers are unwrung,” both detrimental to his ploy, condemning it to failure (3.2.242-243). If indeed Hamlet sought to rattle the king, he was ignorant of Claudius’s mettle, for when confronted by a murderous Laertes, the king also does not flinch.

Who then is the real target? Maquerlot calls Hamlet “the most efficient agent of deflection” (96). This play within a play is the best tool of deflection, and Hamlet uses it to admonish his mother, the only person whose opinion he queries. In response to the promises of the Player Queen, who swears “If, once a widow, ever I be wife!” (Shakespeare 3.2.223), Gertrude parries with the famous judgment, “The lady doth protests too much, me thinks” (3.2.230). When he arrives in her private chamber later, Hamlet’s obsession with his mother’s sexuality is palpable. He greets her saying, “You are the queen, your husband's brother's wife” (3.4.15) and maintains she cannot love Claudius, because “You cannot call it love; for at your age/The heyday in the blood is tame, it’s humble” (3.4.68-69). His “imaginings… as foul/As Vulcan’s stithy” (3.2.83-84) are evident in full when he describes their sex, “In the rank sweat of an enseamed bed,/Stew'd in corruption, honeying and making love/Over the nasty sty” (3.4.92-94) Perhaps Hamlet does not wish to possess Gertrude, as Oedipus did Jocasta, but he intends to control and deny her sexuality and succeeds, for when he demands she “go not to mine uncle's bed… Assume a virtue, if you have it not,” she seems to submit (3.4.159-160).

By then, the story’s trajectory is out of everyone’s hands. Hamlet’s visit to his mother’s quarters leads to Polonius’s murder who was there to protect her from Hamlet’s murderous zeal. Hamlet, now guilty of the same heinous crime as Claudius, is doomed to Laertes’s poisoned rapier. The treacheries are further compounded by the fate of Ophelia, the accidental poisoning of Gertrude, Hamlet’s trickery—which kills Rosencrantz and Guildenstern—and his opportunistic murder of Claudius. The mousetrap seemed to succeed so well that it caught almost everyone.

(594 original words, excluding these.)

Works Cited

Derrida, Jacques. "Injunctions of Marx." Specters of Marx, the State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning, & the New International, translated by Peggy Kamuf, Routledge, 1994, pp. 1-60.

Maquerlot, Jean-Pierre. "Hamlet: Optical Effects." Shakespeare and the Mannerist Tradition: A Reading of Five Problem Plays, Cambridge University Press, 1995, pp. 87-117.

Shakespeare, William. “Hamlet.” The Norton Shakespeare: The Essential Plays/Sonnets, edited by Stephen Greenblatt et al. 3rd Edition. W.W. Norton & Company. 2016.

July 21, 2020

My 2020 Hugo Ballot

Best Novel

Gideon the Ninth, by Tamsyn Muir (Tor.com Publishing)The Light Brigade, by Kameron Hurley (Saga; Angry Robot UK)Middlegame, by Seanan McGuire (Tor.com Publishing)I read all 6 of the novels this year, and they were all spectacular. I would not argue against a vote for any of the others: the polar locked (both the planet and two characters) The City in the Middle of the Night, by Charlie Jane Anders (Tor;Titan), the Leguinian dispossessing A Memory Called Empire, by Arkady Martine (Tor; Tor UK), or the lyrical The Ten Thousand Doors of January (Redhook; Orbit UK), by Alix E. Harrow.One reason I chose Gideon the Ninth is because of its original voice. The protagonist is Gideon, the adopted cavalier of the Ninth House, who sees the world through a lens of sarcasm, tempered by humor, understandable in that she serves Harrowhark (who despises her), the Ninth House necromancer intent on reclaiming her house's greatness by becoming the Emperor's all-powerful lyctor (a kind of a necro-saint). It is also a locked door mystery where people keep getting bumped off (like Agatha Christie's Ten Little Indians), secrets, betrayals... honestly, so much going on my head was spinning. It is a brilliant debut novel by Kiwi author Muir and also the first of a promising series.

The Light Brigade and Middlegame both treat one of my favorite science fiction topics, how time can be parsed and edited, recursively even, in very different ways. The protagonists or settings could not be more different: Hurley's Private/Corporal Dietz comes from a dystopic São Paulo in a world where corporations literally own you and McGuire's two protagonists Roger & Dodger who grow up in a world like America in the 80s with a group of sinister alchemists pulling strings behind the curtain. They both do an impressive job in dealing with narratives where truth is not revealed linearly. Hurley's book is beyond grim, but McGuire's villains are evil people who will stop at nothing to achieve their goals.

Best Novella “Anxiety Is the Dizziness of Freedom”, by Ted Chiang (Exhalation (Borzoi/Alfred A. Knopf; Picador))In an Absent Dream, by Seanan McGuire (Tor.com Publishing)The Deep, by Rivers Solomon, with Daveed Diggs, William Hutson & Jonathan Snipes (Saga Press/Gallery)The novella category was a lot easier for me. Ted Chiang's story deals with a future where there are devices people can use to communicate with others (even themselves) in parallel worlds. There is an entire Silicon-Valley like industry and even a recovery program for people who get too hooked. I loved the premise as well as the moral play Chiang tells against the backdrop. It is also such a well-executed story, drawing you in, and leaving you thinking for days, which is what good science fiction should do.

McGuire's engaging story is a fairy tale where a lonely girl discovers a movable portal to an enchanting goblin market with wonder, adventure, and friends, along with barbed hooks and exorbitant costs. This author's ability to create young believable characters always impresses me. We both fear and understand her choices.

Guess what happened to all those pregnant women seized by slavers and dumped into the Atlantic on their journey to America. Well, in Solomon's world, they became a type of merfolk, a society consumed by history and consuming of its historians. Also, the merfolk are not very happy when they are forced to remember their origins, so there will be a reckoning. I have something of a fetish for these reworkings of old fantasy and horror archetypes (The Vampire Chronicles, IT, etc), so this was an easy choice, but it is also, without a doubt, a great story for 2020 and the first summer of #BlackLivesMatter. My only negative is that the story seemed a bit truncated, but something that leaves you wanting more is never bad.

Best Novelette

“The Blur in the Corner of Your Eye”, by Sarah Pinsker (Uncanny Magazine, July-August 2019)“For He Can Creep”, by Siobhan Carroll (Tor.com, 10 July 2019)Emergency Skin, by N.K. Jemisin (Forward Collection (Amazon))"Blur" is a brilliant tale of self-discovery for an author with a Watson-like assistant. It speaks to me on many levels, especially about reaching that state of creativity when the world disappears and there are only words. It also packs a hook out of nowhere that will leave you staggering. Siobhan Carroll's "Creep" is fun with the Devil that teaches the true power of the kitty cat. Jemisin's "Skin" is about another kind of devil, where the superior Randites must come home for a recharge to a world they left behind, because of all its problems. It turns out the problems left with the *superior* beings.Best Short Story

“Blood Is Another Word for Hunger”, by Rivers Solomon (Tor.com, 24 July 2019)“And Now His Lordship Is Laughing”, by Shiv Ramdas (Strange Horizons, 9 September 2019)“Do Not Look Back, My Lion”, by Alix E. Harrow (Beneath Ceaseless Skies, January 2019)Hugo award preference does not necessarily mean how the story appeals to me. Case in point: I did not choose my favorite nominated short story "A Catalog of Storms," an adroit execution of a pretty difficult concept for storytelling. Instead I chose a dark Rivers Solomon story about death, rebirth, and revenge, because it spoke to me about race relations, and I read it when the media was covering the violent suppression of the marches. "Laughing" is a great portrayal of the human cost of Churchill's war against the people of the Indian subcontinent. "Lion" is about escaping a bellicose society that uses its people for its war machine, a beautiful story through and through, and (again) perfectly captures today's mood for me.Best Series

The Wormwood Trilogy, by Tade Thompson (Orbit US; Orbit UK)The Expanse, by James S. A. Corey (Orbit US; Orbit UK)Winternight Trilogy, by Katherine Arden (Del Rey; Del Rey UK)This is the first group where I have not read all of the entries. I do not know the Luna series by Ian McDonald, nor Planetfall by Emma Newman, and I have only read a couple of the InCryptid series by Seanan McGuire (they were excellent stories.) I have no problem with my choices though.

The Wormwood Trilogy (Rosewater, Rosewater Insurrection, & Rosewater Redemption) tells about a unique alien invasion where their presence attracts humans like moths to a flame for healing, along with a presence in a psychic field called the xenosphere. Much of Earth's defense takes place there, but Thompson is subversive, and at a certain point in the story, I swear I hated humans so much I would have switched sides. He also plays with the dynamics of tension and release like he is conducting a symphony. It is simply great writing in every way, and the story switches protagonists from Kaaro to Aminat, giving the story a very different feel. These are incredible heroes, ones with flaws, making it easy to identify with them. Anyway, Wormwood is brilliant.

I am only part-way through The Expanse (it will be 9 books and I am on Cibola Burn) and have only watched the first season, which means I am lucky to have so much to look forward to. :-) The worldbuilding is sensational. I love the characters too, even the ones I despise. It is space opera but feels proximate, because much is rooted in familiar: the corruption, the conflicts, and the backstabbing. Anyway, I love it.

I chose Winternight (The Bear and the Nightingale (2017), The Girl in the Tower (2017), and The Winter of the Witch (2019)) for several reasons. I love the borderline air of fantasy/reality Arden creates, a Faerie setting reminiscent of Naomi Novik's Spinning Silver and Uprooted. Winternight is also about the church's repression of women, which also struck a chord. Mostly, though, I just love her writing, how she transports you into a cold world infused with wonder.

Best Related Work

Worlds of Ursula K. Le Guin, produced and directed by Arwen CurryThe Lady from the Black Lagoon: Hollywood Monsters and the Lost Legacy of Milicent Patrick, by Mallory O’Meara (Hanover Square)Becoming Superman: My Journey from Poverty to Hollywood, by J. Michael Straczynski (Harper Voyager US)Arwen Curry's film includes interviews of Le Guin showing her humanity and has some great clips from previous conventions. Curry does a spectacular job integrating her energetic presence together with her history, so we understand how she crafted the worlds we so love. This is the best related work by far. I also loved reading O'Meara's story of making monsters in Hollywood (a place where there are already plenty of monsters for a woman trying to make monsters). J. Michael Straczynski's story is a great immigrant story that sounds like a response to evil in many forms, especially from some in power. I also liked Gwyneth Jones's book biography about Joanna Russ, but I can only vote for three. Farah Mendlesohn's Heinlein book was great too, but stories about Heinlein's efforts to include POC by removing descriptions of them and picking suggestive last names (all to get past Southern US book censors) is no longer perceived as valiant. I read this at a time when police were busting people's heads in the street, so... Also, I recognize Celeste Ng's napkin-scrawled speech actually had tremendous impact (ha!), but I cannot in good faith rate it above my other choices.

Best Graphic Story or Comic

LaGuardia, written by Nnedi Okorafor, art by Tana Ford, colours by James Devlin (Berger Books; Dark Horse)Die, Volume 1: Fantasy Heartbreaker, by Kieron Gillen and Stephanie Hans, letters by Clayton Cowles (Image)The Wicked + The Divine, Volume 9: “Okay”, by Kieron Gillen and Jamie McKelvie, colours by Matt Wilson, letters by Clayton Cowles (Image)LaGuardia is another story that hits both immigration (ok, alien immigration) and racism notes. It is a story with uncommon heroism and Okorafor does a great job with characters and pacing. The art is exceptional and helps set the atmosphere. I love the weird D&D-themed Die, which reeks of IT, in that the horrors of teenage years haunts the characters when they are older (and both well-equipped in some ways and definitely deficient in other ways to deal with the danger.) I also chose the final volume of The Wicked + The Divine to celebrate this incredible series. Of course all the other entries were strong too. I loved Paper Girls so much, but you can only vote for three. Grrrrrrr...

Best Dramatic Presentation, Long Form

Avengers: Endgame, screenplay by Christopher Markus and Stephen McFeely, directed by Anthony Russo and Joe Russo (Marvel Studios)Captain Marvel, screenplay by Anna Boden, Ryan Fleck and Geneva Robertson-Dworet, directed by Anna Boden and Ryan Fleck (Walt Disney Pictures/Marvel Studios/Animal Logic (Australia))Us, written and directed by Jordan Peele (Monkeypaw Productions/Universal Pictures)During the Pandemic, thanks to my son's Disney Plus subscription, we have been watching all the Marvel films. Of course I already saw them a few times because I am a Marvel addict. Endgame is peak stuff, but Captain Marvel's story is also incredible, telling about the Kree-Skrull war (from the early 70s comics), and revealing a nuanced truth about how dangerous it is to be so certain. My last choice, Us, is a great horror film, and I also want to give a shout out to Universal Studios's Halloween Horror Nights for the maze. I'll never look at rabbits the same way again.

Best Dramatic Presentation, Short Form

Watchmen: “A God Walks into Abar”, written by Jeff Jensen and Damon Lindelof, directed by Nicole Kassell (HBO)The Mandalorian: “Redemption”, written by Jon Favreau, directed by Taika Waititi (Disney+)Watchmen: “This Extraordinary Being”, written by Damon Lindelof and Cord Jefferson, directed by Stephen Williams (HBO)Two of my favorite Watchmen episodes (which will no doubt split the vote) and the only Mandalorian episode nominated. Easy choice for me.

Best Editor, Short Form

Lynne M. Thomas and Michael Damian ThomasJonathan StrahanSheila WilliamsThis is so hard. I went with the editors of Uncanny (one of my favorites), Strahan (who lives and breathes short stories), and Sheila Williams from Asimov. All great choices, but to be honest, I cannot choose between them.

Best Editor, Long Form

Sheila E. GilbertNavah WolfeBrit HvideSheila E. Gilbert is editor and co-owner of DAW, which publishes so many great books, including the InCryptid series of Seanan McGuire I mentioned before. Navah Wolfe is from Simon & Schuster's science fiction imprint Saga (remember The Light Brigade?), and Brit Hvide is from Orbit (The Ten Thousand Doors of January).

Best Professional Artist

Tommy ArnoldGalen DaraJohn Picacio Tommy Arnold's Gideon cover.

Tommy Arnold's Gideon cover. Galen Dara (cover of best of sff)

Galen Dara (cover of best of sff) John Picacio's cover of a Wild Cards story.

John Picacio's cover of a Wild Cards story.Best Semiprozine

Uncanny Magazine, editors-in-chief Lynne M. Thomas and Michael Damian Thomas, nonfiction/managing editor Michi Trota, managing editor Chimedum Ohaegbu, podcast producers Erika Ensign and Steven SchapanskyBeneath Ceaseless Skies, editor Scott H. AndrewsFIYAH Magazine of Black Speculative Fiction, executive editor Troy L. Wiggins, editors Eboni Dunbar, Brent Lambert, L.D. Lewis, Danny Lore, Brandon O’Brien and Kaleb RussellI subscribe to Uncanny & BCS. I read two FIYAHs as well. These have great stories.

Best Fanzine

The Book Smugglers, editors Ana Grilo and Thea JamesGalactic Journey, founder Gideon Marcus, editor Janice Marcus, senior writers Rosemary Benton, Lorelei Marcus and Victoria Silverwolfnerds of a feather, flock together, editors Adri Joy, Joe Sherry, Vance Kotrla, and The GI know these less. I did go to the sites and tried to judge what I liked best, but my vote here is somewhat uninformed.

Best Fancast

Be The Serpent, presented by Alexandra Rowland, Freya Marske and Jennifer MaceThe Coode Street Podcast, presented by Jonathan Strahan and Gary K. WolfeClaire Rousseau’s YouTube channel, produced & presented by Claire RousseauAll the Fancasts nominated are great, but I liked the content in 2019 of Serpent. Coode Street was also great, and this year Strahan is doing short interviews during the pandemic. Rousseau's YouTube channel is both informative and entertaining.

Best Fan Writer

Adam WhiteheadJames Davis NicollCora BuhlertI was delighted to find Whitehead & Nicoll nominated. I have found myself on their blogs in the past. The information is great. Mostly there are book reviews but there are wide ranging pieces too. Great stuff. I chose Buhlert after reading one of her stories. I did not know the other nominees.

Best Fan Artist

Iain ClarkAriela HousmanGrace P. FongIain Clark's stuff is amazing!

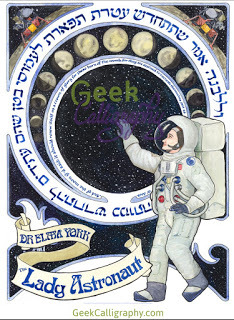

I loved this image with the calligraphy in the center by Ariela Housman:

I loved this Fong image too:

Astounding Award for Best New Writer, sponsored by Dell Magazines (not a Hugo)

Emily Tesh (1st year of eligibility)Tasha Suri (2nd year of eligibility)R.F. Kuang (2nd year of eligibility)Of these Kuang is likely the most famous (because of the excellent, but tragic Poppy Wars), but I also loved the first book in Tesh's series (Silver in the Wood), and Suri's Empire of Sand is awesome. Tesh's sequel, Drowned Country, is out in August.----

Well that's it. I wish I had more time to delve into these deeper, but I have to write a Shakespeare paper about Merchant of Venice and cutting and opening. Careful with that knife, Shylock.