Rebecca Addison's Blog

October 15, 2017

One month in Bali: How I ate my way to contentment

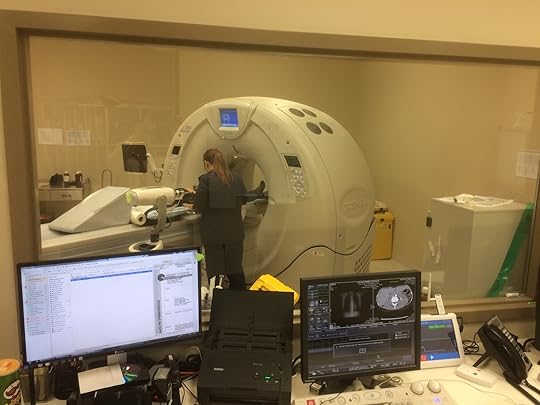

One week before I was due to fly to Bali, I found myself queuing in the carpark of a radiology clinic, watching in disbelief as the drivers around me gave up and turned their engines off, abandoning their cars. Somewhere upstairs, an MRI machine waited for me. It was an appointment I couldn’t miss. And yet miss it I would, unless I worked out how to extract my car and miraculously find another park. A circuit around the block revealed it would be a ten-minute walk, at least. Impossible. That I was going to miss my appointment because I couldn’t manage a short walk from my car to the front door felt especially cruel.

But this was my life. For nine long months, I’d been on bedrest. Breathing had become like trying to suck in air in a room full of smoke. On bad days, just walking down my hallway felt as though someone pressed their fist against my chest. My heart hammered with the slightest exertion. I woke multiple times a night with pain like hot glass between my ribs. And I was exhausted.

I was not only exhausted by my physical challenges but by the thoughts that had plagued me since my first hospital visit months before. Would I die? Why was this happening to me? Was I going to have to live this way forever – and how long would forever be, anyway? Since that first, frightening hospital stay, I’d run the gauntlet of emotions in an embarrassingly stereotypical fashion. I’d seen my share of denial, anger, and bargaining. By the time I found myself in that carpark under the MRI clinic, I’d run out of feelings. People constantly asked me how I was, how I felt, so I had plenty of time to wonder at myself, looking for the answer. I could come up with only one word: Empty.

I found a park, almost weeping with relief when a young mother pointed at her car and made the ‘steering wheel’ action with her hands. Inside, they informed me I needed a cannula for the scan. I hadn’t expected a needle. My hands were still swollen and blue from a hospital visit the week before; my underwear hid a tender knot of purple where a catheter had been inserted into a vein through my groin. I’d always prided myself on my lack of fear when it came to needles. Blood tests had never been a problem for me. I even watched. But when the receptionist told me about the surprise cannula that morning, I felt brittle, like the slightest breeze could turn me to dust. It was all I could do not to slump to the floor and cry.

Our month in Bali had been booked almost a year ago, before any of us could conceive of me being sick. Back then, it had been a response to the craziness of the Christmas season. I’d had enough of ferrying children around, of shops and traffic, of never seeing each other for longer than the time it took to pick up a phone and disappear into our respective bedrooms. It was intended to be an escape from our lives. I’d booked the tickets on sale and tucked the trip away in the back of my mind. Every now and again I’d allow myself to dream about it. Maybe my husband could take our daughter up the slopes of Mount Batur to see the sunrise. We’d finally explore the northern part of the island. I imagined myself taking a yoga class every day, my muscles lengthening; the sun turning my skin the colour of a chestnut. But when I got sick, I refused to imagine the trip any longer. Instead, I moved from appointment to appointment. I lost my shyness when it came to stripping to the waist for an ECG. I tracked my heart rate and blood pressure with military precision, all while trying not to allow my illness to define me. It defined me anyway.

I left the scan weak and teary, embarrassed at myself. And when the day of our departure finally arrived, I was indifferent. I even slept well the night before, unmolested by pre-travel nerves. My husband pushed me around the airport in a wheelchair while I pretended not to notice the stares. By the time we arrived in Denpasar, I couldn’t summon any feelings at all, other than the low hum of anxiety I’d been carrying with me ever since I decided to chance a trip to a small island with a serious cardiac issue. Illogically, I messaged my best friend and said I’d changed my mind about the whole thing.

Bali. Frog-green, violent pinks, smoke and incense. Roosters crowing at 5am. Motorbikes whipping down narrow lanes. As numb as I was, I couldn’t hide from my senses. Travellers were everywhere – barefooted, long-haired, their wrists a tangle of bracelets. Flaunting their freedom. I couldn’t join them for yoga. But I could follow them into the raw vegan restaurants that had popped up all over Ubud since my last visit. What choice did I have but to toss out my dreams of spending the month in a state of spontaneity and freedom? My body wouldn’t allow it. I decided to focus on the one thing I had to do anyway: Eat.

So while my family explored markets and waterfalls, wandered after dark, arrived home sweaty and ebullient, I stayed at the house we’d rented and read about food. I looked for places that would nourish me; I scoured good and bad reviews. I insisted we go to Canggu to try a vegan restaurant someone on a forum had recommended. I ate salads with cashew cheese flakes and pancakes with coconut whip. I ate coconut ice cream for breakfast, I devoured sushi made from cauliflower and ferments, raw lasagna, miso soup. I looked forward to each meal as if it were a gift. In my regular life, I only ate because my medication demanded I take it with food and I was too scared to ignore it. At home, I survived on crackers and toast. But in Bali, for the first time in my life and not a moment too soon, I discovered I had an appetite.

As the days wore on and I kept eating, I noticed the anxiety I’d brought with me from Australia had grown quiet. Some nights, I slept for long hours without waking, something that hadn’t happened in months. My supply of energy lasted longer. I wasn’t better; my symptoms still plagued me by the minute. And yet I was better. I wanted to eat. The planning, the research, the pride in choosing a restaurant and seeing my family’s delight when they tasted their meals – it gave me a sense of achievement I’d sorely missed during my months of bedrest. I couldn’t do much, but I could eat. Somehow, food became the thing that saved the trip. Made the trip. And it saved me.

It wasn’t what I’d envisioned when I’d booked our tickets all those months before. But then, neither was my life. The simple act of eating taught me to accept and even embrace whatever the day presented me with. I left the island without having explored much further than the small village we lived in. I still couldn’t touch my toes. But I was changed nonetheless. I was no longer empty.

I was full.

August 23, 2017

Finishing a novel: The ebb and flow of writing

Yesterday I picked up a copy of Anne Lamott’s book Bird by Bird, and opened it to the page where she talks about writing as a process of filling up and emptying out. It made me think about where I am in my writing life at the moment, having just finished a long project that took a lot out of me, both creatively, and personally. Empty felt like a good word.

I like the way Ms Lamott, thinks of writer’s block – not as a barrier, but simply the state of emptiness that comes after a great outpouring of work. It makes sense to me more than anything I’ve ever read about writing. A natural ebb and flow of creativity and rest.

I’m definitely familiar with the fullness of writing, too. There is a moment during every book I write when I am fit to bursting with words and I rush to my novel with an urgency I didn’t know I had in me. It doesn’t happen overnight; it comes after many hours, days, or weeks of filling myself up, readying myself to work.

And now, once again, I find myself at the end of a book. It’s time to uncouple from the story and say farewell to my characters, at least for now. After so many hours together and so much time invested, the end does feel a little like the empty ache of homesickness.

So how do I go about filling myself up again?

For me, it’s all about being conscious and open to ideas, sounds, smells, textures, words. I read a lot. I listen. I write down words and phrases in my notebooks. I eavesdrop on conversations, notice mannerisms of passing strangers, and allow myself to slip into my imagination before I fall asleep each night. If that’s not cutting it, I try something different. I cook or sew, learn a language, or explore new music. I’m patient with myself. I refuse to listen to the voice that tells me I will never have another good idea or write another book.

I’ve come to believe that these fallow periods are just as important as the fertile ones. How else can we figure out what direction to take next? What idea we want to grab onto and work with?

Every book I finish feels like the last book I’ll ever write. Each time I can’t imagine being that consumed by another story or knowing characters as intimately I know the ones I’ve written. But then, when I’m ready, I move on and the fun begins again. That’s the nature of creative work; you can’t give up, even if you wanted to.

Photo by Izzy Gerosa on Unsplash

August 16, 2017

This is how I write a book

As with all new things, it took me a while to work out the best way to write a novel. The first time I wrote one, it was a junior fiction book for my daughter, so the pressure was off – she’s my kid, she was going to love it, regardless! Then I started writing Still Waters, and again, there was no pressure, because I never intended on publishing it. It’s been four years since I sat down to write that first children’s book, and I’m now seven books into my writing journey. Working on my latest book, a thriller that’s currently out with beta readers, gave me the opportunity to fine tune the way I get through an 80 – 100,000 word novel. All writers do it differently. This is my process.

I’m often asked if I plan out my novels before starting them, and I have to confess that I do not. I usually have the arc of the story and the ending in mind, but I don’t sit down and plot it out by chapter or scene. I need the freedom explore different ideas as I go along, and often I don’t know what’s going to happen until I’m at that point in the story. I like to start by writing a simple scene and I’m a little funny about how I do it. I usually open a new document and write it without my usual novel formatting in place, and I never use any headings like Chapter One. With these first few scenes, there is no expectation that it will become a novel. It’s a time for play, for testing the waters to see if I want to keep going or file it away for another day.

Once I’ve committed to seeing the idea through, I work in Scrivener, which is a program for writers. Scrivener allows you to break your book into chapters and scenes, which can then be easily moved around. You can also storyboard your scenes, add keywords such as whose POV each section is from, things like that. If you’re thinking of writing a book, I recommend you check it out. There’s a free trial available.

My writing day goes something like this:

7.30am – Get up, get kids organised, drop my son at school

9.30am – Climb into bed with a cup of tea, snacks, my laptop, Kindle, and phone (turned on silent)

9.30am – 10.30am – Read the previous two days’ work and make changes. I do this every day before I begin any new writing. Some writers like to write their first drafts without any censorship or editing at all, but I prefer to edit as I go. It means that by the time the first draft is finished, each scene has been looked at two or more times already and the novel is in pretty good shape.

10.30am – 12.30am – Once I’m happy with the last couple of days’ work, I begin writing new material. I usually have a rough plan in mind for what I need to accomplish in that scene or chapter, but I keep this in the very back of my mind when I’m working. If I’m writing a difficult scene, I sometimes listen to music beforehand to get me into the right mood.

After my writing session is over – and this could be an hour or it could be four or five hours – I try to get some fresh air and do something else.

9.30pm – Before sleep, I read through the day’s work and mull that over as I’m lying in bed. When I’m in an intense writing phase, I often dream about my book or wake up with new ideas or ways to solve a tricky plot problem.

My latest novel took just over three months of working in this way for me to get a complete draft. I moved it onto my Kindle and read it as if I had just bought it, making notes as I went. Once those changes were made, I read it again, then sent it out to a couple of trusted readers who have read all of my work so far.

Then I waited.

There is an important but uncomfortable step in writing books, and it’s not something I’m very good at. Waiting. After a book is finished, you have to forget about it for a while, which is just about impossible because it’s all you can think about. I like to leave mine for a minimum of six weeks. It gives my readers a chance to look at it, and by the time I get back to it, I know that I’ll have a new perspective on the work.

Once the readers have come back with their comments and the book has come out of hiding again, it’s time to get to work. This is the time to think with your head, not your heart, and consider every aspect of your novel. Does that character add anything? Does that scene need to be there? Is it too slow at the end? Too rushed? This process took me over a year to get through, and then I did it again after an agent read it and gave me some feedback. I have no doubt that I’ll be doing it again and again, if I am lucky enough to sell it to a publisher.

With my other books, I really hated the editing part. I love writing so much; it’s almost a high when things are going right. Editing felt like work. But with this latest work, I’ve learned to love editing as much as writing. I want this book to be the best it can possibly be and I’m prepared to do everything, anything, to make that happen.

So that’s how it’s done! Or at least how I do it. If you’re a writer, let me know in the comments if this is different or the same to how you work.

Photo by Oliver Thomas Klein on Unsplash

August 13, 2017

Can you accept a compliment?

One of the reasons it took me so long to say the words, “I’m a writer” out loud was the fear that it would attract attention. I wouldn’t exactly say I’m a shy person… I can meet strangers easily enough, have conversations at parties, I do okay in new situations. What I don’t like, in a skin crawling, want to climb out of my body and run kind of way, is the attention of others, and in particular, compliments.

I’ve been thinking about this lately. I’ve come a long way since I was an insecure twenty-something. I can confidently say what I like and what I don’t, what I agree or disagree with; I can stand up for a cause I believe in, even if it’s unpopular. So why can’t I accept a compliment?

While it sometimes feels like everyone around me can bask in the glow of attention and take a compliment with ease, the fact is that I’m not alone. Loads of people hate compliments. And we usually deal with them in one of four ways:

(1) Deflect! Deflect!

Whenever anyone ever says anything nice about the way I look, I usually say this: It’s all smoke and mirrors. Meaning, it’s trickery. It’s makeup, or clothes, or whatever. What I mean is – it’s not really me, please, please, stop looking at me. When someone says something about my body (usually in relation to being thin after having children), I always say this: All the women in my family are small. Even if I’ve actually invested my time and energy in working out. Even if I’m been eating well. It’s harder when someone compliments my work, because I have nowhere to hide. At the risk of sounding cheesy, writing is the truest part of myself. I can’t lie in my work, or lie about my work, because to me, it’s sacred. I can’t say, “Oh, you know, I just threw some words together.” Because I did not throw anything together. I typed and deleted; wrote and rewrote; I fretted over comma placement; I woke in the night thinking of ways to describe a night sky. So, for writing at least, I am learning to say, “Thank you.”

(2) The Put-Down

Some people handle a compliment by immediately pointing out why the person giving it is mistaken. “You’ve done a great job with the wallpaper,” is immediately followed by, “No way, look up at that corner. See how it doesn’t line up?” Women do this a lot with clothes. How many times have we heard a variation of this:

“I love your dress!”

“This? I bought it a million years ago. I just threw it on at the last minute.”

As soon as someone says something nice, we launch in with anything negative we can think of to prove them wrong.

(3) The Hot Potato

This is the compliment you try to get rid of as quickly as you can.

“It wasn’t really me. I barely contributed anything to the project.”

“You should have seen it before my editor fixed it up. She should get all the credit.”

(4) But

Thanks, but….

I didn’t do much, my name shouldn’t even be on there, really…

It wasn’t that big of a deal

I got lucky, I didn’t really deserve it

So many of us (me included) can’t seem to say ‘Thank you’ without following it up with a but.

So what’s the deal with this?

There are probably a whole raft of deep psychological reasons why women in particular struggle with accepting compliments. Women in creative fields have to learn how to do it because it invalidates us as artists when we don’t believe in ourselves. Why is it so hard? I think it’s because we so often feel like impostors. We’re not used to taking up space and owning it. It took me ages to tell people that I wrote books for a living. I still don’t like doing it. But I know I can write well. Not every time I sit down to write… but enough for me to know that writing is what I was born to do.

Here’s what I know: If we want to make things, create good work, put that work out into the world, then we are entering into a contract. We’re sharing our work and in return, people are going to read/view/experience/listen to that work, and they’re going to offer their feedback. Some of that will be negative, because that’s the way it is, and some of it will be positive. Some of it may even be exuberantly so. And we must learn how to accept it. If we keep using the tactics above, what we’re really saying is that the person complimenting you is wrong for loving your work. That’s not how we make progress, both as creatives, and as humans.

If you’re like me and you struggle to accept a compliment, I’m convinced that the only way to change this is to practice. Make yourself say, “Thank you” and bite your tongue when the word, “but” follows. Refuse to put yourself down, or give the praise away to someone who doesn’t deserve it (if they do, that’s another story).

This is easier for me to do when I picture my thirteen year old daughter in my mind. What do I want her to learn from her mum?

That she’s worthy? That she can and should do great things?

Or that she should hide?

Until she’s older, I am her experience of womanhood. She watches everything, takes it in, remembers it. I want her to know that she can take up space, own her talents, and be proud of them. Showing her how to accept a compliment with grace and confidence is a good start, isn’t it?

So … if you liked this article, let me say, Thank you.

August 8, 2017

The Art of Noticing

There’s a girl who walks around my village with a cat in her backpack. The cat isn’t alarmed by this. He has an aristocratic look about him, maybe it’s the whiskers, and he seems to be saying with his eyes, “Yes. This is how it should be. Move on.”

Once, I watched as an elderly couple approached me from the end of the road, his back bent like a cresting wave, her fingers frozen into claws, and as they slowly shuffled along the pavement, I felt a sudden surge of tenderness. But then they got closer and as they passed, I heard her say, “If you keep on doing that, I’m going to cut your fucking winky off.”

There’s a man who sits outside the supermarket passing people pamphlets about something (I’ve never stopped long enough to find out what), and every time he sees me, he compliments something I’m wearing. “I like your pashmina,” he said the other day. “Nice boots.”

In the bakery, a bored looking teenage girl shoves bread rolls into paper bags. Her make up is so thick it splits and cracks around her mouth. I would like to tell her that she doesn’t need it. She has beautiful skin. But she is surly and cold-eyed, and I am still working my way up to it.

Once, a trio of boys (I can’t bring myself to say men) yelled at me as I passed the kebab shop. They were pumped up and had the testosterone shakes, their swollen arms hanging out of singlet tops, a sheen of sweat leftover from their workouts still on their skin. One of them had half-chewed fries on his pink tongue when he opened his mouth to holler at me. I briefly thought about scaring him. I could go up to him, too close, and tell him my age. But I only lifted my chin and kept walking, even though my eyes wanted to dip to the ground.

For almost two years I helped a boy learn how to read and write. I stayed after the school bell went and gently guided him through the spelling words he hated. I let him draw when he’d had enough. Sometimes as he doodled, he told me about his fathers, both in prison, and about his sister and mother. When I drove home afterwards, I spoke all the things I am grateful for out loud like a mantra, so that by the time I arrived home, I no longer hated the world. One day, he disappeared, and I never got to say goodbye.

A few years ago, I overheard two school mums call me, ‘That stuck up one’, presumably because I rarely talk to any of them – out of awkwardness, not snobbery. I could have corrected them, but I was too shy.

Last week, I forgot it was Book Day at school. I sat through half of the special assembly, watched as all the children but mine showed off their costumes. It was cold so I found a patch of sunshine to sit in, but it was too bright so I had to keep my hand over my eyes like a visor. Twice, I had to stop myself from weeping because I was angry that my illness has changed so much about my life. Then I told myself to get a grip, and I went home.

The last time I saw my grandmother, she gestured at me with her swollen hands; her words like little explosions flying from her frozen mouth, and for a long time no one in the room could understand her. Finally, after long minutes that had my heart torn from my chest, laid at her feet, we understood what she was saying. She was pointing at the top I was wearing. She was saying, “Pretty collar.”

A friend told me once about a work colleague who always makes a big show of contributing a generous amount of money to the office pool whenever a gift needs to be bought. But then when no one is looking, he takes his donation out again, and no one ever knows.

There are stories everywhere, if we are open to them. This is what makes a writer. If you want to write, you first have to notice the world around you. I don’t mean who is in the space around you. Don’t just see the man sitting alone at Mcdonalds at 11am on a Tuesday morning. Notice the creases in his business shirt, the ones that tell you he unwrapped it and removed its cardboard insert only that morning and didn’t have time to iron. He’s rolled the sleeves to the elbow to try and make himself more comfortable but he’s shifting in his chair, and every few seconds he glances at the door, as if he’s embarrassed someone he knows will find him there. See the tattoo? It’s a little bird, cartoonish and out of place on his thick wrist. There are words, too, but you can’t make them out. What’s he ordered? How does he eat it? Does he take big, confident bites? Or does he remove the bread and fish for pickles, before putting everything back together again?

This is what makes a character step out of the page and become a real person. When writers do this well, we can see ourselves in the characters they create. It’s not the obvious stuff – how tall he is, what his hair is like – it’s the small stuff. He’s scared of bees. His favourite treat is a marmite and cheese sandwich with the crusts cut off because that’s what his mum used to make him after school.

If you’re an aspiring writer, I encourage you to practice the art of noticing. The next time you’re out, keep your eyes and ears open. Take notes. You never know what might happen. Your first book could be waiting for you to find it.

Photo by Naomi Hutchinson on Unsplash

August 5, 2017

Hello, Stranger

I have had the strangest couple of months, probably ever. It’s been so weird that at times I haven’t understood myself at all. My mind has entertained thoughts that seem like they belong to someone else; I have done a couple of things that were completely out of character, and often, I have lain awake wondering what on earth I’m doing, and why.

I blame two separate but connected things.

The first is the book I’ve been working on for around eighteen months now. It tells the story of Edith, a woman who meets and marries a successful older man when she’s barely out of her teens. Her husband is controlling and abusive and he makes her life a misery. I have been immersed in this world for hours a day, every day, for over a year. I’ve watched documentaries about domestic abuse. I’ve read my share of suspense and thriller novels to get a feel for the genre. I’ve carefully crafted my characters until they feel like living people. The book has heavy themes, and a narrative that is personal to me, although my life is nothing like Edith’s (thank goodness). When I worked on my recent revisions, I saw some stuff in it that brought up feelings I wasn’t sure I liked feeling.

The second thing is my health. Lately, I’ve thought a lot about dying, both soon, and at a much younger age than I anticipated when I decided to have kids. My husband and I have spent all of our spare time at hospitals and doctor’s offices, as they work hard to figure out what’s wrong with my heart. I’ve lost the innocence I had… the sense that everything is okay with my body. I think most of us go about our lives without thinking too much about what’s going on under the covering of our skin. Who wants to picture their heart beating, their blood moving, all of the intricate mechanisms that need to happen for us to stay alive? Not me. But I don’t have the luxury of denial any longer. As each test result arrives, a small portion of my confidence is stripped away. I’ve landed in a scary place, where I don’t really trust my body to work at all.

These two experiences happened concurrently and as a result… I have felt very unlike myself. When you get to be my age (40 next year), you assume you have the basics figured out. At this point, I really thought there wasn’t much about my personality that could surprise me. I have been through traumatic things before, have grieved before, have experienced illness and fear. But I have not had to lie in a bed for six months, with only my rambling thoughts and my manuscript to keep me company. Or had my life ruled by tests and appointments. Or had my body constantly touched and hurt by strangers.

What I’m trying to say is, I have surprised myself. The way I’ve responded to this process has been both typical (retreating into myself, not eating, gnawing anxiety), and… strange. I’ve had a strong urge to get my affairs in order, say the things I need to say to people, and not put things off any longer. Not really for any morbid reason (although the thought is there), more because my health has become so unstable in the last six months that literally nothing would surprise me. I don’t know what the future holds, and so I feel almost manic in my desire to cross things off my list.

I am, and have always been, a very careful person. I don’t have a lot of friends, but the ones I do have are stuck with me for life. I’m slow to get to know people, naturally quiet in social settings, and not too keen on being vulnerable. I’m also a perfectionist and can be unforgiving when I make a mistake. So what’s a careful, controlled, moderate, type of person to do when she finds herself throwing caution to the wind?

I don’t know the answer to that. My instinct is to run away but for some unknowable reason, I keep leaning in. The only thing I know for sure is that if I can be honest, both in my relationships and my writing, then no matter what happens, I’ll have no regrets. And when you’re sick, you think a lot about regret. I know that you can’t fake writing. Readers are like bloodhounds when it comes to the truth; they can smell insincerity from a mile away. The same transparency should apply to the real world, too.

So that’s my survival strategy for the coming months. My way of navigating the uncomfortable uncertainty that I have no choice but to live with. Be honest, in everything; even if it’s hard.

And also, be kind. Especially to myself.

Photo by Jan Kahánek on Unsplash

June 15, 2017

My love affair with moving

If traveling overseas is the lust-fueled, starry-eyed, first three months of a relationship, then living overseas is a long marriage. You may not want to leap out of bed seconds after opening your eyes, eager to Instagram the sunrise in Cappadocia or the Tsukiji fish market in Tokyo, but you’ll know which restaurant makes the best hangover breakfast, and which restaurant is likely to give your visiting relatives diarrhea. Living overseas provides you with intimate knowledge of a city and just like a marriage, some of what you discover makes you fall deeper in love with the place, and some you wish you could back in time and un-know.

Ever since I read Frances Mayes’ Under the Tuscan Sun as a twenty-year-old with a wicked case of wanderlust, I have been obsessed with the line, “To live wholly in another country fascinates me.” Almost twenty years later, those words still come back to me when I least expect them. Mayes story of packing up and moving to a small town in Italy felt like it was written for me, even though I was living in a small flat in Auckland, New Zealand, at the time, with no plans to live anywhere except the small island I was already on.

But still, I dreamed, and even went as far as looking at jobs and real estate in countries around the globe. On Sunday afternoons, I liked to walk the city streets, quiet and empty except for a few Uni students buying cheap noodles at walk up Chinese restaurants and the occasional group of tourists, always alarmed at the way Auckland shut up shop on Sundays in the late 90s. On those Sunday afternoons, my city felt foreign. I wanted to feel lost, disorientated; I wanted to be surprised at what was around the next bend.

But it was years, a wedding, and two babies before I passed through customs and immigration in another country without any intention of going back the other way. Seven years into our “two year trip to Australia” and we are definitely out of the honeymoon phase and have transitioned to a more comfortable and familiar relationship. So much so, that I decided 2017 was the year to shake things up a little.

I think it was around Xmas time when I made the decision – spontaneously, and in a moment of pure exhaustion brought on by too many commitments (as all big decisions should be made) – I wanted out… away… anywhere but here. I was finally ready to follow Frances Mayes and live wholly in another country. I didn’t want to holiday somewhere; I wanted to live. Minutes later, four tickets to Indonesia were booked and we were mentally planning our exit from everyday life.

It’s only four weeks. As much as I love a fantasy, there is schoolwork and grown up work and pets and responsibilities to consider. But, it’s a start. I expect to fall more in love with the tropical island we’ll be living on and I hope it develops beyond that, beyond the eating out and the swims in the pool and the souvenirs to something deeper and longer lasting. I want my eyes to see new things, my body to rest and heal, my soul to be shocked, surprised, awakened.

Photo Credits:

hamdi-yoga; angelo-abear, miranda-rumi

April 20, 2017

Ration Challenge 2017

About a month ago, my twelve year old daughter came running into my bedroom saying, “Mum! Mum! Have you heard about the Syrian refugees??” I looked at her face – pale, wide-eyed – and asked her, “What have you seen?”

She had seen an ad on Youtube and whatever was in it, it left her teary and shaken. As we talked it through, she kept asking me one question: Why didn’t you tell me?

In this world of bombs and beheadings, terror attacks, and attacks on women, on Muslims, on the LGBTQI community, how do we as parents know what to share with our children? And when?

I don’t have the answer. I know that I want my children to be compassionate people, to be advocates for those without voices, to be changemakers. I know that I don’t want them to live in a bubble. But I also don’t want them to be frightened about things they can’t control.

My daughter and I talked for a long time. I shared with her how upset I am about the Syrian refugee crisis and told her that her dad and I give money every month to help. She asked if helping also helped the sad feeling and I said it did; that sometimes doing something, even a small thing, can make you feel less powerless. We talked about setting aside some money every week and once it reaches $100, getting together as a family to decide where we want to donate it.

In the way of twelve year olds, the conversation gradually shifted from Syrian refugees to what’s been happening with her at school, to a boy she kind of likes, to the gymnastics classes she wants to start taking. Even though it’s been a few weeks since that night, I’ve stowed that memory away in my mind, and I’ve had my eyes open, looking for an opportunity for her do something to help.

Enter the Ration Challenge! This is a one week challenge held from 18-25 June, where participants eat the same food rations a Syrian refugee would receive to raise awareness and money. There’s not a lot of food at play here, in fact when I first saw the picture, I thought it was the rations for a DAY not a week!

After reading through the rules and requirements, I showed the short video on the website to my daughter. She was keen straight away. Then my husband decided to join her for support and Team Addison was born. I’m exceptionally proud of both of them, especially my food-loving girl, who isn’t even that keen on lentils and beans. This is why donations before the challenge begins are so important – once you reach donation goals, you get rewards in the form of food (Jemima will have her eyes on the 50g of sugar once she gets to $400!)

If, like us, you’ve been moved by the plight of the Syrian refugees and would like to raise money, why not join the thousands of others in the 2017 Ration Challenge here.

Or if you’d like to support my daughter and husband in their challenge, you can do so here. No donation is too small.

Thank you for your kindness!

Also….

If you want to join the challenge, make you sure read the requirements including the health and safety information. People under 18 can join, but it needs to be under the watchful eye of a parent.

April 3, 2017

Life in the slow lane: why POTS might make me a better writer

Hello. I am that annoying person who pushes their shopping trolley slightly too close to your ankles for comfort. I don’t like red lights, or people who dillydally in picking up the dice when it’s their turn to roll in Monopoly, and I especially hate it when my wifi is slow. You see, I’m in a rush. Perpetually. Mind and body are always in motion, and that’s just the way I like it. I’m the woman who doesn’t need to write a list because she can remember it all, the woman who collects words and facts the way her daughter collects apps on her ipad, the wife who can’t believe her husband’s forgetfulness because it makes no sense to her, the mother who sews book day costumes while she’s baking gluten free, egg free, fundraiser cupcakes and never forgets a school note.

Well, I used to be. It’s just that I’ve always had a snappy brain. It wakes me up with ideas; it bullies me when I try to rest. My brain is a Type A New York executive, or a movie newspaper editor who barks orders about deadlines while slamming his fist on the desk. My husband likes to ponder and sometimes (all the time) he is maddeningly slow at getting stuff done. He gets distracted. I stay on task. If you could hear our brains working, his would be some kind of mashup – a bit of classical violin that morphs into blues guitar just before you’re hit with some house music. Mine would be simpler: a fast ticking clock, a metronome, the quick snapping of fingers.

Well, it used to be. Now that I have dysautonomia, things are a little different upstairs.

Now it’s not uncommon for ME to ask HIM to remind me to pick up a child, or hand in a note. He slows his pace when we’re out so that I can keep up. Always the night owl, now I’m in bed just after nine. Things take a long time. Last week I made a dress and it took me three days. Before this illness I would have sewed that sucker in three hours.

I’m part of this POTS support group that emphasizes positivity. There’s a fair bit of talk about silver linings in this group too, and I have to admit that it’s taken me a while to find one. I mean, there’s not a lot to celebrate about suddenly finding yourself with a body that behaves like a total jerk. But here I am, silver lining firmly in sight.

You know that dress that took three days? I didn’t mind it. I didn’t get annoyed, not even when my overlocker kept breaking a thread, or when I had to unpick something. This weekend I waited on the path for my husband to stop faffing around inside and finally get to the car and I didn’t mind that either. I sat down and I watched a freaking bee collect pollen on a lavender bush. And I liked watching the bee. She was fascinating.

My whole life has been spent in a state of high energy, which incidentally also feels like anxiety, and now that I have this thing, this dysautonomia, that has changed. I can sit without thinking of what I should be doing. I can breathe slowly and look around me. I’m no longer in any kind of rush, which is good, because with this heart, I’m not going anywhere fast.

It could be because my blood pressure is normal, or my blood volume, or my brain is dull, or maybe it’s side effects of the meds…. or anything. I don’t care. I need a silver lining; I thought I wouldn’t find one. I’ll take what I can get.

So now I am the slow person in the supermarket. I’m actually the slow person everywhere. And as much as I wouldn’t wish a chronic illness on anyone, sometimes I look at all the busy people, all the rushing people, and I want to tell them what they’re missing.

I see all the things now. And for a writer, that’s not such a bad thing.

March 14, 2017

A ratbag diagnosis: Surprise! You have POTS.. and it’s nothing to do with kitchenware.

We were in a big hardware store sometime in early January, standing in front of a shelf of solar lights as we talked about which ones would look best in our native garden. It was hot outside and almost as hot in, the fans doing little to move the heavy air around the warehouse.

“Argh,” I groaned, as I plucked my shirt away from my back. “It’s so hot in here. Are you hot?”

My husband shrugged, and I narrowed my eyes at him. He looked as refreshed as when he’d gotten dressed that morning. He wasn’t even sweating.

“It’s warm,” he agreed when he saw my face. “But it’s not that hot.”

By now my chest was heaving as I tried to suck in enough air to stifle that panicked I’m drowning feeling I’d been experiencing on and off for the past couple of weeks. I pressed my hand to my heart and felt it racing.

“Can we hurry?” I asked. “I can’t breathe in here.”

We pulled a set of lights off the shelf and made our way to the checkout as quickly as we could, only my default walking pace – purposeful and annoyingly fast for anyone shopping with me – was decidedly slow.

“Are you okay?” my husband asked as we climbed into the car and he cranked the AC, directing the vent towards my face.

“I don’t know,” I admitted. “I think I need to get my iron levels checked.”

But, I didn’t get my iron levels checked, not for another two months. It was the school holidays, and we had a lot going on. We lost a dear friend to cancer, we went away, our son had a severe anaphylactic reaction while at a remote camping ground and had to be taken to a country hospital via ambulance, our daughter started high school.

In February, our son brought home one of those miserable viruses – the ones that go from person to person, blocking up noses, and inflaming ears, and making heads pound. When it was my turn, it took me a long time to get over it. I’d wake up each day expecting to feel at least a little bit better, but it was exactly the same as the day before. I had no energy; all I wanted to do was lie in bed. Even walking to the other end of the house felt like an enormous effort.

Then there was the heat. The hottest summer on record, days and days of stifling temperatures, wearing wet clothing, spraying each other with water, tossing and turning all night. Everyone was hot, but I was suffering. I felt like I had weights around my ankles every time I walked. I couldn’t think properly. My feet were ridiculously hot and heavy. We joked that they were “hot bricks” and I’d press them to my husband’s back at night, sighing in relief when they touched his cool skin. And that breathing thing was back with a vengeance.

But I still didn’t go to the doctor. Because I had changed to a vegetarian diet a few months earlier, I assumed I was low in iron. I started iron tablets, then B12 tablets, and was convinced that it would solve whatever was wrong with me. Besides, what was I going to say? Ummm…. the heat is making me really hot? I’d had enough experience with cynical doctors over the years to have more than a small measure of performance anxiety when it came to demonstrating my symptoms. Besides, it would go away – right?

Then about a month ago, I was walking up the small incline to collect my son from school and by the time I got to the top I had to hold onto the fence for a minute to catch my breath. My head swam, and I lost my peripheral vision for a few seconds before everything came back into focus. That’s weird, I thought. Better see if I can get those iron levels checked. As it happened, the doctor had an appointment that afternoon. I picked up my son and went to the clinic, where I informed my GP that I was breathless and I needed some blood taken. Job done.

Only, the doctor didn’t like the sound of my symptoms. He’d noticed the way I could barely speak to him because I was puffing like I’d run up a flight of stairs.

“Do you ever feel your heart beating? Like palpitations?” he asked as he sat back in his chair and crossed his arms.

“I guess so,” I replied. “Sometimes it races. Or kind of flutters? But I’ve had that before when I was anemic and needed a blood transfusion. So I’m sure it’s just that.”

He wasn’t convinced.

“Let’s do an ECG. Just to make sure,” he said. “We’ll do the bloods as well.”

“Ok,” I said, thinking to myself, Oh, great. How much will this cost? What a waste of time.

Over the next two days I had my blood taken, and I did the ECG, and then it was the weekend, and we had relatives to stay. I spent that weekend either sitting or lying down. Washing the dishes had me bent over, eyes squeezed shut, chest heaving as I tried to get enough air into my lungs. I couldn’t think of the word ‘petition’ one day and had to stop mid-sentence, eventually having to describe it so that my husband could give me the word I was looking for. I remember him looking at me for a second too long after that happened because I don’t forget words. I’m a writer; I’ve had a lifelong love affair with the things. But it was easy to brush it off and forget about it. Life was busy, after all, and I was still tired from that virus. After one particularly bad day, I did was most people do, I started googling. I read about iron infusions, convinced that my levels were so low I’d have to spend a boring day in the hospital with a needle in my arm. Maybe I’d need another blood transfusion. That wasn’t so bad last time, I remembered. In fact, I’d felt pretty great afterward.

Tuesday arrived, and I went back to the clinic to get my results. I saw a new doctor, and he was very concerned at the way I was breathing. He put one of those oxygen/heart clips onto my finger and saw that my resting heart rate was 108. I started prattling on about my iron levels, and he patiently waited for me to finish.

“Well, the thing is,” he said, “your bloods look great. Iron is right in the middle.”

Oh.

“I’d like you to go and get a CT with contrast of your lungs. Today. Here’s the referral. Can you call me to let me know when you’re getting it done? I’ll ring you this afternoon with the results.”

I had the first small tickle of fear in my belly then. I’d only ever heard that trace of urgency in a doctor’s voice once before, and that was when my then three year old had to have an MRI of his brain. I promised to go straight to the radiology place and numbly went to pay. While I was at the counter, a call came in, and I heard my name. The receptionist said it was the cardiologist who had reviewed my ECG, and he wanted to speak to the GP, so I should wait. They talked for a long time. That’s when I knew.

There was an abnormality on my ECG, and the cardiologist strongly urged me to get the CT with contrast urgently. I gathered my papers and stepped out into torrential rain. Unable to run to the car, I shuffled down the path as quickly as I could, my hair dripping and my mind racing.

It was all systems go from that day on. ED admissions, Holter monitor, a cardiologist appointment that had me bundled into the car with an oxygen tank in the back, bound for a hospital an hour away. Admission to acute care, then acute cardiac, more CT’s with contrast, chest x-rays, too many blood tests to count. I had gone from being a busy mum with a million things to do at once, from working with an editor on my latest book – to being in a room with three old men, stripped of my privacy, unable to walk to the toilet without first ringing for a nurse to accompany me.

Check out this video of my monitor when I stood up next to the bed. It felt like going from resting to the end of a workout in the space of 20 seconds accompanied by a massive adrenaline rush (the bad kind, not the ‘high’ kind).

Every time I stood up, my heart monitor set off every alarm in the ward, and I had nurses calling out to see if I was okay. I had to sit to shower, to brush my teeth, because the combination of standing and moving my arms was too exhausting. I learned to sleep with beeping monitors and lights in the room, with the sound of my roommates snoring and farting in their sleep, with the laughter of nurses and the whine of IV trolleys being wheeled along the linoleum floor. I had a low-grade fever; I had a serious BP crash; I fasted for 40 hours waiting to find out if I needed heart surgery. I spent long frightened hours thinking about my life expectancy, about cancer, about heart disease. I thought about that movie Beaches and tried in vain to remember the heart condition that killed that lovely lady with the long brown hair. I learned to be on the receiving end of help in the form of childcare, meals, gifts, company – something that I’ve never been good at. I wrote down passwords and life insurance information; I tried and failed, to think of what I could write down for my children in case I didn’t come home.

And then finally, the diagnosis everyone had suspected but couldn’t confirm until everything else was eliminated. POTS or postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. A miscommunication between the autonomic nervous system and the heart. Coupled with my very low blood pressure and low blood volume, it was no wonder my heart was working overtime trying to pump the blood that was pooling in my legs and abdomen north to my heart and brain. My cardiologist called it a “ratbag diagnosis”. As a doctor, he likes to fix things. POTS can be managed, but it’s a chronic illness. He expressed his regret at not being able to order a procedure that would cure me. When he was ready to discharge me, he gently let me know that the medication I was taking would help, but I wouldn’t be the way I was before.

I’ve been home for two days. I still haven’t tackled the dreadlock situation on the back of my head because brushing my hair remains too tiring. I’ve walked a bit. I’ve spent a lot of time sitting. Yesterday, I wanted to pick my son up from school and ended up sitting on a sofa in the office because I couldn’t cope with standing for 5 minutes before the bell rang. I couldn’t make it to the car, so my husband had to drive down and pick me up from the entrance. I realised I need a mobility card for my car, and a wheelchair for longer trips out, at least for now.

I’ll be wearing compression stockings to my waist, even in summer. I need to drink at least 3L of water a day and eat a high salt diet and wear a medic alert bracelet and monitor my heart rate and blood pressure. And then there’s the medication I’ll be taking, even though I hate taking drugs, and have devoted years of my life to natural medicine and nutritional healing, and not taking drugs. It’s a lot to get my head around.

I’ve been lucky in life in that I’ve never had my choices drastically limited until now. All of the things I knew I’d probably never do (run a marathon, become a cross fit junkie, do a major overnight hike) were still possibilities. There’s a big difference between choosing not to do something and not being able to. I wonder what my life is going to be like now. How the family will have to adapt and what concessions they’ll have to make. I think about the medication that makes me woozy and wonder about my writing, my memory, my clear thinking, quick brain, and wonder if accessing creativity will be like wading through mud now, instead of gliding through water.

This is all new. As it turns out, it’s kind of new for my cardiac team, too. When I wasn’t being referred to as “bed 21”, the nurses called me, “the young one”. They deal with veteran smokers with clogged arteries. They don’t see women in their thirties with strange symptoms very often, and certainly not ones with anatomically perfect hearts.

So there you go. If there’s one thing you should take away from my story is that if you feel something – do something. I don’t know if it would have made a difference in my case or not, but it definitely would have if my diagnosis were something more serious, like aortic dissection (which was on the cards for a while). My reluctance to see a doctor was a little bit know-it-all and a little bit denial. There are enough health issues in my family already, in the back of my mind I think I was unwilling to add to the list. From now on, though, I am on the list. On the top of the list!

And I realise now, it’s the way it should have been all along.