Curtis Bausse's Blog

March 22, 2025

Book a Break Flash Fiction prize

A big thank you to all who submitted a story to the Book a Break Flash Fiction competition. There were some very good entries, and selecting a winner wasn't easy. So my thanks also go to the judges, Sherry Morris and Phil Baarda, who settled on the following list:

Overall winner: Chris Cottom for his story Puffins Waiting.

"Puffins Waiting is a poignant story of a final family holiday, with a strong last image and ending, where we see each character waiting for their destiny, like the puffin motif of the title."

Second: Amy Durant for her story The Last Summer

Third: Abigail Williams for her story Because Goats Are Rarely The Solution

Highly Commended: Chris Cottom for his story Wouldn't It Be Loverly

These stories will be published later this year in The Best of the Book a Break, a compilation of selected stories from this and previous competitions, with the proceeds going to the Little Sapphires School in Madagascar.

Thanks to the competition donations, a little over 300 euros was raised. Further initiatives are under way with students from Aix-Marseille University, so this year's full total will not be known till June. The current aim is to carry out repairs caused by the last cyclone and to build a study for the headmistress. The Book a Break contributions will be a precious help.

January 16, 2025

A Better World?

Our life in Algeria came to an end in 1960, when my father, who’d been moved up to lieutenant, was deprived of an eye by a vindictive Arab. Despite the way he treated me, I remember feeling sorry for him and thinking all Arabs were loathsome. It was at that age, and for several years to come, to have a father who was a hero; only later did I learn how zealous he’d been in what I came to realise was a more than questionable war.

We came to France, to Gif-sur-Yvette, a pleasant, leafy suburb where children do not go astray. Which I didn’t. I was, if I say so myself, a talented, studious pupil, gifted in art and languages, popular with my peers and held in esteem by my teachers. My parents noted with pride and satisfaction that my school reports were tip top.

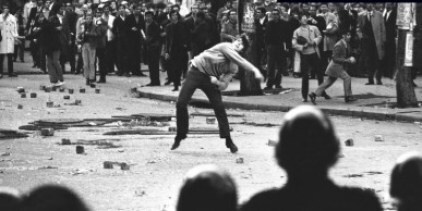

But underneath the goody-goody, a rebel strained to get out. I prowled and fretted like an animal in a cage -- and yet I must have been so accustomed to my niggardly little space that when the cage blew apart, I didn’t even escape. I’m talking now about a certain month of May.

Do I need to justify myself for not being there erecting barricades and setting the Latin Quarter alight? Probably. There were, after all, plenty of adolescents of my age slinging the old Molotovs with the best of them. They may not have understood what was happening, but they had a hell of a good time. And speaking of early accomplishments, by that age Rimbaud had written Le Bateau Ivre.

Well, Gif-sur-Yvette was not quite the same as Paris. Although in our lycée there were sit-ins, debates and gatherings which occasionally got quite stormy, I never imagined myself announcing to my parents after supper that they weren’t to worry, I’d be back in the morning, I was just nipping into Paris to overthrow de Gaulle. That’s not to say we didn’t argue. For two whole months the drama of the nation was enacted in miniature in our flat. Then they packed me off to England for the holidays and when I came back it was over, the seething energy fragmented into whimsical agitation.

Is it only with hindsight that I see in ’68 not the birth of a new era, but the abortion which ratified an old one, and would drip its clotted remains over the whole of the next decade? The maoists and trotskyists and their dissident splinter groups, the advocates of zero growth and bicycles, the health food gurus, the women’s libbers, the buddhists, the drug fiends, the goatherds, the sexpol seminarists -- I sympathised with all, but I couldn’t believe in any. OfficialIy enrolled as a law student, I in fact spent my time reading poetry in cafés and indulging in idle dreams. I could trek through Ethiopia, or join the Palestinians or go and live in the Amazon. Or why not drown in Lake Como? Luckily I had a motor-bike (a gift from my father, who thought I was studying hard), which I drove at breakneck speed around the boulevard périphérique and predictably ended up crashing, whereupon I discovered amongst other things, during ten months in hospital with fourteen operations and not enough morphine, that I was happy to be alive.

The above is an extract from The Sally Effect, a long, sprawling novel published by the now defunct Unbound Press. I may revise it one day - there's plenty in it that's good, but as it stands I'd be more inclined to disown it. I simply wanted to post that extract because although the narrator isn't me, our outlooks are similar. And the older I get, the stronger that outlook becomes.

It's a reaction, no doubt, to the way the world is heading. Fifty years ago I was optimistic, but how can I be optimistic today? The answer to that is Glow. While I might, if the right circumstances arose, joyfully join in a repetition of May 68, I put no trust in revolutions. But I cherish the hope that one day things could be different. They could, in fact, be something similar to Glow.

The Sally Effect ran to 600 pages. Glow is a mere 80. A novella set in an alternative society, one which might have existed if different choices had been made after the First World War.

Available free here.

April 9, 2023

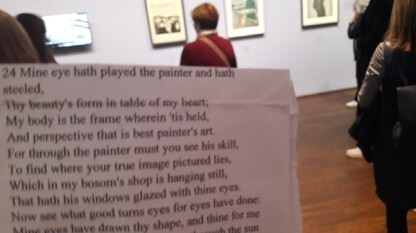

Breughel and the Bard

We're currently in Vienna, where my time is split between two activities: sheltering from the wind in the city's magnificent museums, and pursuing my Shakespeare Balancing Challenge. The two are indeed combined: a performance at the Albertina or the Belvedere is followed, as I wander round the exhibition, by the learning of the next poem.

I manage this combination fairly well. Half a minute memorising a quatrain, then I mentally rehearse it as I contemplate Egon Schiele or Breughel. Admittedly, for the time it takes to recite the lines, I'm not fully concentrating on the picture, but it only rakes a few seconds, and by the time we leave the museum, the sonnet is learnt. By which i mean I can, at that moment, recite all 14 lines of it - but that in itself is no guarantee that a couple of hours later I can do the same. In the 24 hours between that first learning and the performance, there's ample time to forget it, so many more rehearsals are needed to have any degree of confidence. And even then, I've often recited it without hesitation one minute, only for my mind to go blank when I switch on the camera the next.

But no matter. The wind in Vienna is bitterly cold but the museums are warm, and each new sonnet is a painting in words. Breughel and the Bard are good companions.

April 6, 2023

Flamingo Fancy

When was the last time you reached for the handle of your coffee cup and grasped thin air instead? It’s probably never happened, because by the time you were old enough to drink coffee, you’d acquired the skill of cup handle grasping.

On Science for Sport we’re told that “motor skills are tasks that require voluntary control over movements of the joints and body segments to achieve a goal. Some prominent examples include riding a bicycle, walking, reaching for your coffee cup, jumping, running, and weightlifting.”

They didn’t include balancing, I dare say because it’s not that prominent an example. When I’m out and about, I rarely see people imitating flamingos, or if they are, they only go as far as the crimson dress of Manfred Mann’s seminal flamingo comparison of 1966. And even they didn’t have her tucking one leg up towards her bum.

On our block all of the guys call her flamingo

Cause her hair glows like the sun

And her eyes can light the skies

When she walks she moves so fine like a flamingo

Crimson dress that clings so tight

She's out of reach and out of sight.

They do it apparently to save energy and body heat. And it isn’t just flamingos. Lots of birds do it. In fact they’re the champion one-foot balancers. It doesn’t hurt to be ambitious, of course, but if I decided I had to be Shakespeare or nothing, I’d never have started writing. Similarly, though I know that one-legged flamingo immobility is far out of my reach, it hasn’t stopped me working on the skill myself.

And the work pays off! At first it seemed impossible - I wobbled all over the place, the leg muscles just couldn’t hack it. But then they understood that I wasn’t going to let them off - I was serious about this. And they buckled down to it. Slowly, I improved. I don’t lose control any more. If I start listing to port or starboard, all it takes is a little adjustment before it gets too serious, and hey presto, I’m upright again.

The crucial part of skill acquisition is automaticity, when you’re no longer consciously thinking, ‘Uh-oh, I’m losing it - hang on, which muscle do I need to send a command to?’ You’re still sending the command, but without it interfering with whatever else you’re attending to. I started out like a baby learning to walk. It’s still far from perfect, but I’m happy to report that I’m well into the toddler stage, and have high hopes of one day avoiding bumping into furniture altogether.

I’m confident now that if I fail a sonnet performance, it will be a memory problem, not because I’ve lost my balance (at least until sonnet 100, when I start doing them blindfold - that’s a different ball game). Perhaps if I really stick at it, I’ll get a bit closer to the perfect flamingo stance. Though I’d better not push it too far. My wife is very tolerant of my balancing obsession but if she sees me doing it in a crimson dress that clings so tight, she might get worried.

December 15, 2021

Voltaire and the Vaccines

In 1734, Voltaire's Lettres Philosophiques were published, in the eleventh of which he writes of the ‘mad and dangerous English, who inject smallpox into their children’. So thought the anti-vaxxers of the day, led by a certain Dr. Hecqet of Montpellier, the argument raging for almost half a century.

Voltaire tells the story of Lady Mary Montagu, who arrived in Constantinople in 1716 shortly after catching smallpox herself. Parents in that part of the world had been giving the disease to their children for centuries; this was done by making a small incision in the child's arm and inserting a pustule removed from another child. In Voltaire's version, the reason was to preserve the beauty of the daughters, who could then be sold to harems in Persia and elsewhere. Smallpox was an ever present threat to a valuable source of income. Lady Montagu duly had her son inoculated, and on returning to England in 1721, she militated in favour of the practice.

At that time, smallpox accounted for 10% of all deaths, with a fifth of those who caught the disease succumbing to it. Most of the others were disfigured for life. ‘Do the French not like living?’ asks Voltaire. ‘Do French women care nothing for their beauty? We are indeed strange people.’ Gradually, as the evidence in favour of it accumulated, the practice of inoculation caught on. The WHO officially declared smallpox to be eradicated in 1978.

From smallpox to COVID. I had to chuckle the other day to see that Didier Raoult can now be bought as a santon. Raoult was the Marseille doctor who touted Chloroquine as a COVID cure at the beginning of the pandemic. It turned out that despite being a renowned and respected researcher, his dubious methods and unreliable statistics were more those of a charlatan. This didn't stop him promoting his cure in the States, where he found an enthusiastic supporter in President Trump. Today Raoult is in disgrace, dismissed from the medical institute he himself founded. But his santon lookalike has been selling like hotcakes. One can only imagine what Voltaire would have had to say about that.

Santon Strife doesn't feature Raoult, but Darth Vader is there, along with the more familar figures of Joseph, Mary et al. On sale for a limited time for $0.99.

Amazon Apple Barnes & Noble Kobo

September 19, 2021

Brave or reckless?

You're in a car at night on a narrow, winding country road which is unfamilar to you, when you get the impression you're being followed. When you slow down, the car behind slows too; when you speed up, it does likewise. The situation might not be so alarming if you hadn't received an anonymous letter threatening you just a few hours earlier.

What do you do? There aren't too many options. You could drive as fast as you can in the hope of coming to a house or a village where you can seek help. Or you can stop the car, get out and face down your pursuers. Flight or fight?

She drove on a bit more and then, the ultimate test, she stopped the car. The other car stopped too, a couple of hundred yards back.

She checked herself for fear. Was it something you could measure, like an earthquake? At the top of the scale would be her panic in the forest, in comparison to which she was now surprisingly calm. Maybe three and a half. Four at the most. Her heart was beating fast, yes, but she was still able to think, and she found it comforting to know that if she was being followed, at least it wasn’t by a zombie or a werewolf.

At first she was pleased with this. It meant she would analyse her situation in a calm, rational manner, and take a sensible course of action: fight or flight? But then she realised it wasn’t rational at all. Because zombies and werewolves don’t exist, whereas human beings, who when they put their mind to it can be every bit as nasty, are all over the place. Not only that, but they know how to use a gun and are better drivers.

She ought to be more afraid. Not to the point of helplessness, but six or seven would be sensible. If Neanderthals weren’t afraid when they heard a sound in the bushes, they’d have rolled over, gone back to sleep, and a minute later been supper for a sabre-toothed tiger. But although she tried to crank up her fear a notch or two, she couldn’t get beyond five, and after a while, she leant over, opened the glove box and felt about for a Luger automatic. This wasn’t rational either – more a request for divine intervention – because if Magali kept a weapon worth speaking of in her car, presumably she would have spoken of it. All she found was a screwdriver, so short and spindly you wouldn’t even speak of it if you wanted to fix a screw, let alone put the wind up a tiger. A screwdriver against a gun could only end one way. But on a narrow, unfamiliar road at night, the flight option didn’t look promising either. They’d press her into driving so fast she’d skid off the road and land in a ravine. They wouldn’t even have to shoot her then.

It wasn’t a choice between fight or flight. It was a choice between different ways of dying. And on balance, she chose being shot. As she got out, clutching the screwdriver, she braced herself to die.

The driver of the other car put the lights on full beam, dazzling her. She couldn’t see the make or colour, let alone the number plate. She stood by her own car, not moving. Her heart had moved up a few gears and was now pounding furiously: it was the heartbeat of a sitting duck. This had to be the stupidest thing she’d ever done.

And was it? Well, it's no spoiler to say that Sophie survives. But whether she's brave, reckless, naive or just plain lucky is something only the reader can decide.

Truffle Trouble, first in the Sophie Kiesser mystery series, is available for just $0.99.

February 18, 2021

The Glamour Inside

Magali composed herself, taking her time to find the right formulation. ‘It’s just that I sometimes feel overwhelmed by the way you are.’

‘Really? How am I?’

‘Just… To me you’re kind of glamorous. Smooth. And good at whatever you do. You make everything seem so effortless. You have a sort of grace and I’m in awe of you. There.’

‘Priceless! Now who’s the dolt?’

Some characters impose themselves. When a sunken, shattered Charlotte Perle appeared on Magali's doorstep in One Green Bottle, it soon became clear to me that she wouldn't just be a grieving mother in the first book of the series but would feature prominently in all. Something about her, a dignity shining through her bereavement, told me she would be second only to Magali in shaping the series as a whole. Which she did to such an extent that the four books containing it, gathered in a box set, are called The Perle Quartet.

Magali saw it too of course, though she didn't suspect at first quite how important Charlotte would become to her. But she noticed the quiet strength, the elegance and poise, and it wasn't long before she found herself drawn inexorably towards her.

The glamour Magali sees in her doesn't come from designer clothes or jewels, though Charlotte has plenty of those as well. But that remains on the surface - what Charlotte has is the sort of glamour philosopher Carol Gould sees in actor Judi Dench: ”Glamour requires distance. Dench, who is no Garbo or Dietrich, manufactures this not through stage-managed aloofness but through a natural sense of containment.” Glamour, notes Gould, "radiates from the complexity of an individual human character as a particular expression of imagination and personal uniqueness."

A dolt to be in awe of her? Perhaps. But when someone radiates glamour like that, it's difficult not to be.

The Perle Quartet: available now for a limited period at a 50% dicount.

January 30, 2021

The Tragedy of the Judge

One person who gets an occasional mention in my novels is the juge d'instruction (investigating judge or examining magistrate). Being more concerned with the search for clues, which the judge usually delegates to the police or gendarmes, I don't go into detail, but in the French system, these judges play a vital role. With a view to collating evidence in order to indict a suspect, they conduct interviews, issue warrants, appoint experts, carry out searches and seizures, or order telephone tapping. Most of the time, this is done smoothly and efficiently. But in the forthcoming Sophie Kiesser mystery Painter Palaver, there's a reference to a tragic and infamous case in which the juge d'instruction got it terribly wrong - the Grégory Affair.

In October 1984, the body of the 4-year-old Grégory was found in a river in the east of France with his hands and feet bound and a woollen hat over his face. The murderer has still not been found, a lamentable outcome due in large part to the bungled investigation led by the judge, Jean-Michel Lambert. It was Lambert's first post, and he made the fatal mistake of assuming it would be simple. It turned out to be anything but.

Judge Lambert investigates

To be fair, the Grégory case was just one of over 200 he was dealing with at the time. Nor was he the only one to make mistakes: the autopsy was rushed, and the gendarmes lost a vital piece of evidence, an anonymous letter claiming responsibility for the murder. Nonetheless, Lambert allowed himself to get caught up in the media frenzy surrounding the affair, revealing aspects which should have remained secret, jumping to hasty conclusions, and generally showing an astonishing lack of rigour. According to a colleague, “the procedure was properly ransacked by an incompetent, flippant and ultimately deeply unpleasant magistrate.”

The main suspect in the killing was Bernard Laroche, cousin of the victim's father, Jean-Marie Villemin. Laroche was said to be jealous of his cousin's personal and professional life, more successful than his own. Initially Laroche was accused by his own sister-in-law, Murielle, 15 at the time, who said he had driven with her to pick up Grégory outide his home, where he was playing on while his mother was in the house. Murielle later withdrew her statement, saying she'd been pressured into making it by the gendarmes. When Lambert ordered Laroche's release from custody, Jean-Marie Villemin swore he would get revenge on the man he was convinced had killed his son: true to his word, he shot Laroche dead a few weeks later as he was leaving work.

Convinced that Laroche was innocent, Lambert then indicted Grégory's mother, Christine, though the evidence against her was slim. In a bizarre intrusion into this state of affairs, the esteemed author Marguerite Duras then published a text affirming her belief in Christine's guilt whilst simultaneously excusing her as a tragic figure driven to it by the pressures of a patriarchal society. Needless to say, this was not a helpful contribution.

Though Lambert believed she was guilty, Christine was acquitted, while the case itself was removed from Lambert, by now thoroughly discredited, and given to another judge. Lambert went on to have an uneventful career, both as a judge and as an author of detective novels. But the Grégory Affair haunted him all his life: three years after retiring, having just sent his latest novel to his editor, he took his own life in precisely the way described in the novel, asphyxiated by a plastic bag, an empty whiskey bottle on the floor beside him.

Will we ever know who killed Grégory? I doubt it. The case drags on to this day, with new analyses of DNA traces undertaken just a few days ago, but after all this time, with so many mistakes made from the outset, it seems unlikely the truth will ever be known. In Painter Palaver, it gets no more than a passing mention, but in France it has given rise to dozens of books, both by journalists and by the protagonists themselves. Not that Sophie Kiesser has ever read them - she has her own mysteries to solve.

January 8, 2021

A Stunning Secret

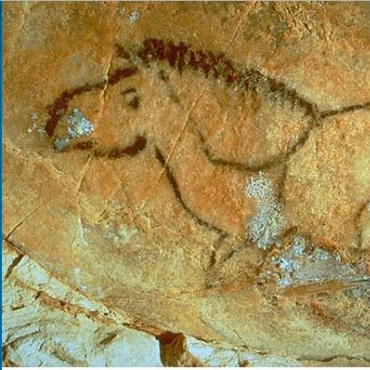

For at least two reasons, the Cosquer Cave near Marseille is amazing - firstly for what's in it, secondly for the story of its discovery.

Penguins, seals, horses, bison and aurochs, all in one space. Painted of course, by cave dwellers who lived there up to 27,000 years ago. My notions of pre-history are a bit vague, the various ages merging into a sameness in my mind, populated by our grunting, gesticulating forefathers, gathered round a fire clad in bearskins. But to be more exact, that's the paleolithic, which stretched for 2.5 million years before gradually giving way to the much shorter mesolithic, which itself gave way to the neolithic. Apart from painting, paleolithic people developed rudimentary stone tools and a belief in the afterlife.

The paintings in the cave are exceptionally well-preserved, mainly because it was cut off from the open air when the sea level rose about 10,000 years ago, sealing the entrance beneath 35 metres of water.

Unclebarned https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index...

Unclebarned https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index...

It would take a brave soul - and an experienced diver - to go into that tunnel, which may explain why the cave was undiscovered for so long. That soul was Henri Cosquer, who first navigated the tunnel in 1985, and then, with a few select companions, went back many times over the next six years. No one else knew of the cave until three divers died there in circumstances never fully explained. A few days later, unable to keep it secret any longer, Cosquer reported his discovery to the Department of Archaeological Research.

Was there any wrongdoing on Cosquer's part? He wasn't implicated in the death of the divers, and has always maintained that his aim was to study the cave, not derive any profit from it. No charges were ever brought against him, and today he is hailed as the intrepid diver who brought to light the unique cultural heritage that bears his name. Naturally, the original cave has been sealed off, but in 2022, a replica will be visible in the MUCEM museum in Marseille.

The story of the Cosquer Cave (with the diver's name changed to Jules Bisquet) gets a significant mention in Calisson Calamity, which also opens with the death of two divers near Marseille. How did they die and why? That too is a mystery - at least until Sophie Kiesser investigates. But even she is surprised by the course that events then take...

Available now on

Amazon Apple Barnes & Noble Kobo

December 14, 2020

Provence, Sweet and Deadly

"Such is the life of man - a few joys soon wiped out by unforgettable pain."

"Everyone knew it was impossible. Then along came an idiot who didn't know, and did it."

"We won't discover the secret of a nightingale's song by opening its throat."

The quotes are from Marcel Pagnol, among the best known writers of Provence. There isn't a lot of depth to his work, but it's richly evocative, steeped in the countryside round Aubagne, where he was born in 1895. His later work, autobiographical, was highly successful, as were the cinema adaptations. He himself was an accomplished film-maker, the first to be elected to the Académie Française.

My Father's Glory, My Mother's Castle, Manon of the Spring or Jean de Florette - the films drawn from Pagnol's writing show a Provence that has largely disappeared, quaintly portrayed in rustic, mistrustful villagers and stubborn peasant farmers battling with the harsh conditions of the countryside. In the world of Pagnol, where old loyalties and grudges never die, there's more than a hint of nostalgia.

But why, you might ask, am I so enamoured of Pagol? Well, I'm not really, but it so happens that out of all his quotes, one in particular caught my eye: "You need one-third almonds, one-third fruit confits, one-third sugar – and a quarter savoir faire."

A strange quote to single out, but there he captures all the mystique of calissons, and this world-renowned speciality of Aix en Provence is at the centre of Sophie Kiesser's second murder mystery, the newly released Calisson Calamity.

In a tragic incident near Marseille, two divers die – accident or murder? And how are their deaths connected to calissons, the world-renowned almond and fruit speciality of Aix en Provence? As a bitter feud erupts between two calisson producers, Sophie sets out to investigate – but soon gets out of her depth in a world that’s not as sweet – nor as cozy – as it seems.

To go with the ingredients specified by Pagnol, here you’ll also find a dose of greed, a splash of revenge, and a pinch of thwarted love. Mix all that together and what do you get? A perfect calamity.

Available now on

Amazon Apple Barnes & Noble Kobo