Doug Enaa Greene's Blog

November 17, 2025

Bloodstains on the Confession: The Moscow Trials and Their Defenders

Interview on my new book,

In Stalin's Shadow: Leon Trotsky and the Legacy of the Moscow Trials

. Originally published over at

Left Voice

.

Interview on my new book,

In Stalin's Shadow: Leon Trotsky and the Legacy of the Moscow Trials

. Originally published over at

Left Voice

.The Moscow Trials, beginning in 1936, were based on astounding claims: prosecutor Andrey Vyshinsky accused many top Bolsheviks of conspiring with Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan to destroy the Soviet Union — the very working-class government the accused had helped create. Some 700,000 people were executed during the Great Purges. Can you give us a brief overview?

Before talking about the Moscow Trials, it’s important to understand the background underlying the Great Purges. In the years before 1936, Stalin and the bureaucracy had consolidated power by defeating various oppositionists inside the Soviet Communist Party. Even after becoming the paramount leader of the USSR, Stalin’s power was not unchallenged. Stalin’s policies of industrialization and collectivization had resulted in some genuine advances, but also led to a great deal of upheaval and social discontent in the USSR. As a result, there were figures inside the Communist Party who questioned Stalin’s line and even wanted him removed. In addition, the rise to power of Hitler and Nazism in Germany after 1933 meant that the Soviet Union was facing the very real possibility of war in the near future. All of these domestic and foreign events laid the groundwork for the Great Purges.

What set off the Purges was the assassination of Leningrad Party leader Sergei Kirov in December 1934. While the assassin was arrested almost immediately, Stalin believed that he was involved in a vast overarching plot involving former Oppositionists to overturn the government. Over the coming years, the Soviet security forces would attempt to root out all these “enemies of the people.” By 1937, the Purges ravaged all aspects of Soviet society, party, and state as a witch hunt atmosphere took hold. In their zeal, the Soviet police conducted mass arrests of innocent people and torture was routinely practiced.

In three show trials held in Moscow during 1936–38, former Communist Party leaders such as Zinoviev, Kamenev, and Bukharin confessed to fantastic crimes of working with Trotsky and fascist powers to wreck the economy, conduct espionage, and carry out terrorism with the aim of overthrowing Stalin and restoring capitalism in the USSR. All of them were found guilty with most being summarily shot. Trotsky himself was living in Mexican exile, but he was murdered by a Soviet agent in August 1940.

At the end of the Purges, pretty much all sources of opposition to Stalin, whether real or imagined, had been wiped out in the Soviet Union. Now the bureaucratic caste surrounding Stalin was able to consolidate power. While the bureaucracy professed loyalty to the goals and program of communism, they had done so by murdering leaders of the October Revolution. In many respects, the Purges helped to suffocate revolutionary consciousness in the Soviet and international working class. Even though the restoration of capitalism happened decades later, I would argue that its roots can be traced back to the consolidation of Stalinism and the Great Purges.

Then and now, these accusations strain credulity. But lots of communists suppressed their doubts, saying that there must have been lots of counterrevolutionary conspiracies, and Stalin was at most overreacting to real threats. What was the material basis for the Purges?

As you mentioned, Communist Party members around the world pretty much accepted the “Trotskyite-Fascist” narrative given during the Moscow Trials. They believed that Stalin represented the historical necessity of communism. Questioning that would potentially lead to doubting the revolutionary cause itself. Any doubts amongst party members were expressed privately, if at all. It would only be after 1956 and Khrushchev’s Secret Speech that you’d see party members question Stalinist dogma. In my book, I detail how devastating that speech was for longtime militants.

On the other hand, anticommunists saw the Purges as proof that revolutions are like the Roman god Saturn eating their own children. For them, this was a sign that a proletarian revolution was bound to end in totalitarianism, terror, and the Gulag. A genuine understanding of the Purges means rejecting these twin narratives.

I would argue that there are four overlapping material processes that caused the Purges. The first is that Stalin and the government in Moscow wanted to impose centralized control on the more distant periphery. Contrary to popular understanding, Stalin did not exercise total control in the country but faced a great deal of passive resistance from regional bureaucrats. Eliminating these layers and replacing them with more compliant figures would allow Stalin to more easily implement directives for the whole country. It should be noted that this side of the Purges largely targeted loyal Stalinists. The late historian J. Arch Getty did extensive research on this.

The second element in the Purges involved the direction of Soviet foreign policy. After 1933, there was a back-and-forth between those who wanted collective security with Britain and France to contain Germany, including former right oppositionist Nikolai Bukharin and Red Army Marshal Mikhail Tukhachevsky, and others in the Soviet government who were more open to some kind of accommodation with Nazi Germany. The most prominent figures in the latter camp were Stalin and Molotov. It is likely the disagreements over foreign policy led to the purge of Bukharin and the Red Army.

A third cause of the Purges involved the longstanding struggles between Stalin and various opposition groups. By the 1930s, Stalin had triumphed over these groups, but the growth of the bureaucracy and privilege was a mockery of the egalitarianism of the October Revolution. Now Stalin wanted to consolidate his control by essentially “cleaning house” and wiping out opposition to its rule. This took the form of what the historian Vadim Rogovin called a “preventive civil war” by Stalin to discredit and destroy the real and potential communist opposition. Leon Trotsky was the most well-known figure with a clear alternative program. That’s why he was the central figure mentioned during all the trials. For Stalin, it was essential to paint Trotsky as just a fascist criminal in order to discredit his alternative to Stalinism.

The final element of the Purges was a vast hunt for “Trotskyites” with spy-baiting, hysteria, and general denunciation. By 1937, this got out of hand as the Purges affected all levels of the Soviet Union, leading to vast round-ups and mass arrests by the NKVD, the Soviet interior ministry. Stalin did not direct it, and this served no reasonable purpose. In other words, this was a process that got completely out of control.

Defenders of Stalin would say something like: you can’t make an omelette without breaking a few eggs — and this kind of bloody violence was necessary to save the revolution. Did the Moscow Trials indeed help protect the Soviet Union?

According to all the neo-Stalinists I discuss in my book — Domenico Losurdo, Ludo Martens, Grover Furr, and Bill Bland — the Purges safeguarded the Soviet Union by wiping out a dangerous pro-fascist fifth column. This was also the line promoted by Communist Party members during the 1930s and 1940s as well.

Simply put: they are completely and utterly wrong. In 1937, the Purge reached the Red Army and decimated the highest levels of its command. This had a devastating effect on the Red Army when World War II began. According to the historian Moshe Lewin, most of the frontline commanders had little experience when the Germans invaded. The army purges undoubtedly contributed to the high casualties and initial defeats that the Red Army suffered after Operation Barbarossa. While the USSR eventually won the war, the military purges were a self-inflicted wound by Stalin that made victory more costly than it should have been.

Among those purged was Mikhail Tukhachevsky, who was not only a dedicated communist and anti-fascist, but a brilliant military thinker who developed new strategies to fight the Germans. Even though his theories were condemned, many of his strategic ideas were later adopted by the Red Army during World War II, enabling them to win at the crucial battles of Stalingrad and Kursk. I honestly would like someone to explain to me how purging a dedicated communist military leader helped the Soviet Union.

While for most people today, it’s obvious that the Moscow Trials were an enormous frame-up, you’ve written an entire book looking at the works of four Stalin apologists. Do you think their ideas are relevant today?

It’s true that most (correctly) people look at the Moscow Trials as frame-ups. So why write about blatant apologists when everyone already knows the truth?

Despite the collapse of the USSR, Stalinism in its various forms remains an important pole of attraction on the broader Left. In rejecting anticommunist propaganda about the Soviet Union, there is often a rush to the opposite pole, that “Stalin did nothing wrong.” It’s important to push back against these dogmatic and irrationalist views of Stalin by promoting a sober and rational Marxist approach.

Radicalizing people who are looking for alternatives to the dead-ends of social democracy and liberalism find Marxism-Leninism very attractive. We shouldn’t forget that there are five countries that claim its heritage, including China, Cuba, and Vietnam. I should add that Communist Parties remain major forces on the Left in many countries such as India, Greece, and others. In the United States, the Communist Party has experienced growth in recent years and their publishing house reprinted Stalin’s The History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks) (Short Course). This text was originally published in 1938 and served as the Soviet Bible, including the narrative of the trials. So neo-Stalinism remains a contender in contemporary politics and it is necessary to combat its ideas.

The most serious of the bunch is the Italian philosopher Domenico Losurdo. How does he try to justify the trials?

Before I answer, I want to say that Domenico Losurdo cannot be reduced to Stalinist apologia. Losurdo’s writings on subjects ranging from Hegel, Nietzsche, liberalism, and Bonapartism are major works deserving serious consideration. In providing a critical balance sheet for Losurdo or other pro-Soviet intellectuals such as Georg Lukács, Albert Soboul, Eric Hobsbawm, or W.E.B. Du Bois, we need to keep in mind that they made genuine contributions while often believing the most outlandish things about Stalin and the USSR.

Losurdo is unique amongst the figures I covered in that he does not rely primarily upon the confessions and verdicts of the Moscow Trials to make his case — but his conclusions are pretty much the same. The crux of Losurdo’s argument is based on his understanding of the revolutionary process more universally. He believes that all revolutions — whether in France, Russia, and China — necessarily pass from a utopian stage to a more conservative stage if they are to survive. According to Losurdo, Trotsky represented the egalitarian, utopian, and messianic hopes of 1917. To preserve the revolution, it was necessary to consolidate the new order by adopting more “realistic” policies. This is what Stalin did by promoting socialism in one country, the bureaucracy, material incentives, inequality, etc.

Losurdo argues that Trotsky could not understand this historic necessity, so he accused Stalin of betraying the revolution. This led to a “Bolshevik civil war” between Trotsky and Stalin, resulting in the fratricidal violence of the Purges. However tragic and horrible the Purges were, Losurdo claims that Trotsky’s defeat was required if the Soviet Union was to survive. Additionally, he believes that Trotsky’s opposition to Stalin meant that he objectively — if not subjectively — aligned himself with Adolf Hitler and fascism.

What makes Losurdo’s defense of Stalin unique is that he doesn’t depend upon the validity of the Moscow Trials. Rather, his argument is more overtly political. It does not matter if the confessions were absurd. What matters to Losurdo is that Stalin’s program represented historical necessity while Trotsky’s ideas did not. As a result, he sides with Stalin regardless. Interestingly, Losurdo’s position echoes the French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty, who expressed the same idea in Humanism and Terror (1947), which is the most erudite philosophical defense of Stalinism ever written. Yet Losurdo’s method means that he is unable to recognize the counterrevolutionary nature of Stalinism. I discuss Losurdo specifically and Stalinism more generally at length in my book, Stalinism and the Dialectics of Saturn: Anticommunism, Marxism, and the Fate of the Soviet Union.

The most clownish defender of Stalin is certainly Grover Furr. You are probably one of just a handful of people who have read Furr’s numerous books full of conspiracy theories. Can you offer us insight into what he believes?

Furr is probably the most prolific defender of Stalin currently alive. If you believe his own account, he became interested in Stalin and Soviet history during the 1960s. From the 1980s onward, Furr has written a small library of books and articles on Soviet history during the Stalin era. Considering his professorship in medieval literature, his defense of the Stalinist Inquisition is rather ironic. I personally think Furr is absolutely sincere in his views.

His most (in)famous book is Khrushchev Lied: The Evidence that Every “Revelation” of Stalin’s (And Beria’s) “Crimes” in Nikita Khrushchev’s Infamous “Secret Speech” to the 20th Party Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union on February 25, 1956, is Probably False. Based on that overlong title, he thinks that Khrushchev lied from beginning to end and that Stalin committed no crimes. To put it bluntly: he defends the official Soviet narrative on Stalin and the Moscow Trials.

Furr relies primarily on the confessions from the Moscow Trials. He claims that these confessions were truthful and that there was no coercion by the Soviet security forces involved. When it comes to the bloodstains on the document with Tukhachevsky’s confession, he argues they could have been from a nosebleed. Beyond this, he believes that the lack of physical proof for any “Trotskyite-Fascist” plot doesn’t matter. After all, conspirators are not supposed to leave any paper trail behind. Based on Furr’s logic, the best proof for Trotsky’s conspiracy is that there is no proof at all.

He refers to every rumor, half-truth, and piece of gossip to prove the conspiracy. He also has a habit of exaggerating these points while ignoring the widespread evidence that counters his arguments, including from the Soviet archives. Furr is also guilty of pretty much every logical fallacy that you can imagine.

Furr also believes that Stalin was a secret democrat whose plans to democratize the Soviet Union were thwarted by NKVD chief Nikolai Yezhov. Blaming Yezhov allows Furr to exonerate Stalin for the severe violence of the purges. In fact, he believes that both NKVD chiefs Yagoda and Yezhov were in league with Trotsky. Even though two figures later unmasked as “enemies of the people” led the NKVD during the period of the Moscow Trials, Furr doesn’t believe that this calls into question the verdicts. He thinks Yagoda and Yezhov were spies, but the evidence they produced was still reliable.

But I don’t think Furr is actually the most clownish defender of Stalin. One other person I cover is Bill Bland, who was a follower of Enver Hoxha. Bland not only defends Stalin but essentially declares him to be a divine being. Bland is the closest you see to the transformation of Stalinism into a religion. To my knowledge, Furr has not yet done that.

Stalinists believe they discovered the largest conspiracy in world history: hundreds of thousands of communists working with an array of imperialist powers, their sworn enemies. And even 80 years later, no one has found even a single scrap of paper offering proof. This is amazing when you consider that the archives of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan ended up in the hands of their enemies.

You’re correct that no proof exists anywhere about the “Trotskyite-Fascist” conspiracy. No one has unearthed anything in the archives of the USSR, Poland, Germany, or Japan. Nor were high-ranking Nazis charged with anything relating to the Moscow Trials at Nuremberg, even though the Soviet Union had judges there.

Even though there was no proof of a “Trotskyite-Fascist” conspiracy, Communist Party members around the world believed it. If Stalin represented truth and progress, then Trotsky stood for falsehood and fascism. They acted upon it with tragic results. Throughout my book, I detail the rhetoric that you heard from Communist Party militants in France, Yugoslavia, Canada, and the United States condemning Trotsky as a hireling of fascism. I also show how this led to bloodletting in the Spanish Civil War, Trotsky’s murder, and the antisemitic show trials in Czechoslovakia. We can see the danger of what happens when people — even supposed Marxists — ignore objective truth and decide to act on a conspiracy theory.

There has been a certain growth of neo-Stalinism in recent years. How do you explain that? Is that what motivated you to write this book?

Anyone who has been online knows that weird people and even weirder ideas tend to find each other. You can see this with the most bizarre version of online neo-Stalinism which is “MAGA Communism” and the so-called American Communist Party. Although, I would argue the ACP is a degeneration of Stalinism toward more openly fascist positions.

Certainly, the persistence and growth of Marxist-Leninist parties was a motivation for me. Yet I was really motivated to write this book in order to combat the apologetics by Furr and others. Most people will ignore Furr, like we do with Holocaust deniers such as David Irving. Yet it is still necessary for someone to do the dirty work of exposing their falsehoods. No one has looked at Furr systematically and it was a necessary task. I will admit that the hardest part of this project was reading Furr’s whole corpus.

Beyond that, I think that there is a broader need to challenge neo-Stalinist ideas as part of a general struggle against irrationalism. In recent years, there has been an extraordinary growth in conspiracy theories and “alternative facts,” particularly in the United States. We’ve seen a resurgence of neo-Nazism and alt-right groups, who have all promoted various antisemitic conspiracy theories.

Many people understand the world through conspiracy theories. However, the methodology of conspiracism cannot allow us to actually know reality — it is akin to religious fundamentalism.

Neo-Stalinist conspiracism is a similar sort of conspiracism on the Left. And I believe that Marxists should train our members in reason and science — we are the true heirs to the heritage of the Radical Enlightenment, after all. Exposing the conspiracism of Losurdo, Martens, Bland, and Furr is a useful exercise in promoting critical thinking, materialist dialectics, and historical analysis. Always and everywhere, conspiracy theories are obstacles to reason and progress. If we want to really know the world, then we cannot use conspiracist nonsense. Rather, reason and historical truth can help us truly understand and change the world in the wider struggle for communism.

Doug Greene, In Stalin’s Shadow: Leon Trotsky and the Legacy of the Moscow Trials (London: Resistance Books, 2025), 272 pages, £18.

Furr Interview

Interview on my new book,

In Stalin's Shadow: Leon Trotsky and the Legacy of the Moscow Trials

. Originally published over at

Left Voice

.

Interview on my new book,

In Stalin's Shadow: Leon Trotsky and the Legacy of the Moscow Trials

. Originally published over at

Left Voice

.The Moscow Trials, beginning in 1936, were based on astounding claims: prosecutor Andrey Vyshinsky accused many top Bolsheviks of conspiring with Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan to destroy the Soviet Union — the very working-class government the accused had helped create. Some 700,000 people were executed during the Great Purges. Can you give us a brief overview?

Before talking about the Moscow Trials, it’s important to understand the background underlying the Great Purges. In the years before 1936, Stalin and the bureaucracy had consolidated power by defeating various oppositionists inside the Soviet Communist Party. Even after becoming the paramount leader of the USSR, Stalin’s power was not unchallenged. Stalin’s policies of industrialization and collectivization had resulted in some genuine advances, but also led to a great deal of upheaval and social discontent in the USSR. As a result, there were figures inside the Communist Party who questioned Stalin’s line and even wanted him removed. In addition, the rise to power of Hitler and Nazism in Germany after 1933 meant that the Soviet Union was facing the very real possibility of war in the near future. All of these domestic and foreign events laid the groundwork for the Great Purges.

What set off the Purges was the assassination of Leningrad Party leader Sergei Kirov in December 1934. While the assassin was arrested almost immediately, Stalin believed that he was involved in a vast overarching plot involving former Oppositionists to overturn the government. Over the coming years, the Soviet security forces would attempt to root out all these “enemies of the people.” By 1937, the Purges ravaged all aspects of Soviet society, party, and state as a witch hunt atmosphere took hold. In their zeal, the Soviet police conducted mass arrests of innocent people and torture was routinely practiced.

In three show trials held in Moscow during 1936–38, former Communist Party leaders such as Zinoviev, Kamenev, and Bukharin confessed to fantastic crimes of working with Trotsky and fascist powers to wreck the economy, conduct espionage, and carry out terrorism with the aim of overthrowing Stalin and restoring capitalism in the USSR. All of them were found guilty with most being summarily shot. Trotsky himself was living in Mexican exile, but he was murdered by a Soviet agent in August 1940.

At the end of the Purges, pretty much all sources of opposition to Stalin, whether real or imagined, had been wiped out in the Soviet Union. Now the bureaucratic caste surrounding Stalin was able to consolidate power. While the bureaucracy professed loyalty to the goals and program of communism, they had done so by murdering leaders of the October Revolution. In many respects, the Purges helped to suffocate revolutionary consciousness in the Soviet and international working class. Even though the restoration of capitalism happened decades later, I would argue that its roots can be traced back to the consolidation of Stalinism and the Great Purges.

Then and now, these accusations strain credulity. But lots of communists suppressed their doubts, saying that there must have been lots of counterrevolutionary conspiracies, and Stalin was at most overreacting to real threats. What was the material basis for the Purges?

As you mentioned, Communist Party members around the world pretty much accepted the “Trotskyite-Fascist” narrative given during the Moscow Trials. They believed that Stalin represented the historical necessity of communism. Questioning that would potentially lead to doubting the revolutionary cause itself. Any doubts amongst party members were expressed privately, if at all. It would only be after 1956 and Khrushchev’s Secret Speech that you’d see party members question Stalinist dogma. In my book, I detail how devastating that speech was for longtime militants.

On the other hand, anticommunists saw the Purges as proof that revolutions are like the Roman god Saturn eating their own children. For them, this was a sign that a proletarian revolution was bound to end in totalitarianism, terror, and the Gulag. A genuine understanding of the Purges means rejecting these twin narratives.

I would argue that there are four overlapping material processes that caused the Purges. The first is that Stalin and the government in Moscow wanted to impose centralized control on the more distant periphery. Contrary to popular understanding, Stalin did not exercise total control in the country but faced a great deal of passive resistance from regional bureaucrats. Eliminating these layers and replacing them with more compliant figures would allow Stalin to more easily implement directives for the whole country. It should be noted that this side of the Purges largely targeted loyal Stalinists. The late historian J. Arch Getty did extensive research on this.

The second element in the Purges involved the direction of Soviet foreign policy. After 1933, there was a back-and-forth between those who wanted collective security with Britain and France to contain Germany, including former right oppositionist Nikolai Bukharin and Red Army Marshal Mikhail Tukhachevsky, and others in the Soviet government who were more open to some kind of accommodation with Nazi Germany. The most prominent figures in the latter camp were Stalin and Molotov. It is likely the disagreements over foreign policy led to the purge of Bukharin and the Red Army.

A third cause of the Purges involved the longstanding struggles between Stalin and various opposition groups. By the 1930s, Stalin had triumphed over these groups, but the growth of the bureaucracy and privilege was a mockery of the egalitarianism of the October Revolution. Now Stalin wanted to consolidate his control by essentially “cleaning house” and wiping out opposition to its rule. This took the form of what the historian Vadim Rogovin called a “preventive civil war” by Stalin to discredit and destroy the real and potential communist opposition. Leon Trotsky was the most well-known figure with a clear alternative program. That’s why he was the central figure mentioned during all the trials. For Stalin, it was essential to paint Trotsky as just a fascist criminal in order to discredit his alternative to Stalinism.

The final element of the Purges was a vast hunt for “Trotskyites” with spy-baiting, hysteria, and general denunciation. By 1937, this got out of hand as the Purges affected all levels of the Soviet Union, leading to vast round-ups and mass arrests by the NKVD, the Soviet interior ministry. Stalin did not direct it, and this served no reasonable purpose. In other words, this was a process that got completely out of control.

Defenders of Stalin would say something like: you can’t make an omelette without breaking a few eggs — and this kind of bloody violence was necessary to save the revolution. Did the Moscow Trials indeed help protect the Soviet Union?

According to all the neo-Stalinists I discuss in my book — Domenico Losurdo, Ludo Martens, Grover Furr, and Bill Bland — the Purges safeguarded the Soviet Union by wiping out a dangerous pro-fascist fifth column. This was also the line promoted by Communist Party members during the 1930s and 1940s as well.

Simply put: they are completely and utterly wrong. In 1937, the Purge reached the Red Army and decimated the highest levels of its command. This had a devastating effect on the Red Army when World War II began. According to the historian Moshe Lewin, most of the frontline commanders had little experience when the Germans invaded. The army purges undoubtedly contributed to the high casualties and initial defeats that the Red Army suffered after Operation Barbarossa. While the USSR eventually won the war, the military purges were a self-inflicted wound by Stalin that made victory more costly than it should have been.

Among those purged was Mikhail Tukhachevsky, who was not only a dedicated communist and anti-fascist, but a brilliant military thinker who developed new strategies to fight the Germans. Even though his theories were condemned, many of his strategic ideas were later adopted by the Red Army during World War II, enabling them to win at the crucial battles of Stalingrad and Kursk. I honestly would like someone to explain to me how purging a dedicated communist military leader helped the Soviet Union.

While for most people today, it’s obvious that the Moscow Trials were an enormous frame-up, you’ve written an entire book looking at the works of four Stalin apologists. Do you think their ideas are relevant today?

It’s true that most (correctly) people look at the Moscow Trials as frame-ups. So why write about blatant apologists when everyone already knows the truth?

Despite the collapse of the USSR, Stalinism in its various forms remains an important pole of attraction on the broader Left. In rejecting anticommunist propaganda about the Soviet Union, there is often a rush to the opposite pole, that “Stalin did nothing wrong.” It’s important to push back against these dogmatic and irrationalist views of Stalin by promoting a sober and rational Marxist approach.

Radicalizing people who are looking for alternatives to the dead-ends of social democracy and liberalism find Marxism-Leninism very attractive. We shouldn’t forget that there are five countries that claim its heritage, including China, Cuba, and Vietnam. I should add that Communist Parties remain major forces on the Left in many countries such as India, Greece, and others. In the United States, the Communist Party has experienced growth in recent years and their publishing house reprinted Stalin’s The History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks) (Short Course). This text was originally published in 1938 and served as the Soviet Bible, including the narrative of the trials. So neo-Stalinism remains a contender in contemporary politics and it is necessary to combat its ideas.

The most serious of the bunch is the Italian philosopher Domenico Losurdo. How does he try to justify the trials?

Before I answer, I want to say that Domenico Losurdo cannot be reduced to Stalinist apologia. Losurdo’s writings on subjects ranging from Hegel, Nietzsche, liberalism, and Bonapartism are major works deserving serious consideration. In providing a critical balance sheet for Losurdo or other pro-Soviet intellectuals such as Georg Lukács, Albert Soboul, Eric Hobsbawm, or W.E.B. Du Bois, we need to keep in mind that they made genuine contributions while often believing the most outlandish things about Stalin and the USSR.

Losurdo is unique amongst the figures I covered in that he does not rely primarily upon the confessions and verdicts of the Moscow Trials to make his case — but his conclusions are pretty much the same. The crux of Losurdo’s argument is based on his understanding of the revolutionary process more universally. He believes that all revolutions — whether in France, Russia, and China — necessarily pass from a utopian stage to a more conservative stage if they are to survive. According to Losurdo, Trotsky represented the egalitarian, utopian, and messianic hopes of 1917. To preserve the revolution, it was necessary to consolidate the new order by adopting more “realistic” policies. This is what Stalin did by promoting socialism in one country, the bureaucracy, material incentives, inequality, etc.

Losurdo argues that Trotsky could not understand this historic necessity, so he accused Stalin of betraying the revolution. This led to a “Bolshevik civil war” between Trotsky and Stalin, resulting in the fratricidal violence of the Purges. However tragic and horrible the Purges were, Losurdo claims that Trotsky’s defeat was required if the Soviet Union was to survive. Additionally, he believes that Trotsky’s opposition to Stalin meant that he objectively — if not subjectively — aligned himself with Adolf Hitler and fascism.

What makes Losurdo’s defense of Stalin unique is that he doesn’t depend upon the validity of the Moscow Trials. Rather, his argument is more overtly political. It does not matter if the confessions were absurd. What matters to Losurdo is that Stalin’s program represented historical necessity while Trotsky’s ideas did not. As a result, he sides with Stalin regardless. Interestingly, Losurdo’s position echoes the French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty, who expressed the same idea in Humanism and Terror (1947), which is the most erudite philosophical defense of Stalinism ever written. Yet Losurdo’s method means that he is unable to recognize the counterrevolutionary nature of Stalinism. I discuss Losurdo specifically and Stalinism more generally at length in my book, Stalinism and the Dialectics of Saturn: Anticommunism, Marxism, and the Fate of the Soviet Union.

The most clownish defender of Stalin is certainly Grover Furr. You are probably one of just a handful of people who have read Furr’s numerous books full of conspiracy theories. Can you offer us insight into what he believes?

Furr is probably the most prolific defender of Stalin currently alive. If you believe his own account, he became interested in Stalin and Soviet history during the 1960s. From the 1980s onward, Furr has written a small library of books and articles on Soviet history during the Stalin era. Considering his professorship in medieval literature, his defense of the Stalinist Inquisition is rather ironic. I personally think Furr is absolutely sincere in his views.

His most (in)famous book is Khrushchev Lied: The Evidence that Every “Revelation” of Stalin’s (And Beria’s) “Crimes” in Nikita Khrushchev’s Infamous “Secret Speech” to the 20th Party Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union on February 25, 1956, is Probably False. Based on that overlong title, he thinks that Khrushchev lied from beginning to end and that Stalin committed no crimes. To put it bluntly: he defends the official Soviet narrative on Stalin and the Moscow Trials.

Furr relies primarily on the confessions from the Moscow Trials. He claims that these confessions were truthful and that there was no coercion by the Soviet security forces involved. When it comes to the bloodstains on the document with Tukhachevsky’s confession, he argues they could have been from a nosebleed. Beyond this, he believes that the lack of physical proof for any “Trotskyite-Fascist” plot doesn’t matter. After all, conspirators are not supposed to leave any paper trail behind. Based on Furr’s logic, the best proof for Trotsky’s conspiracy is that there is no proof at all.

He refers to every rumor, half-truth, and piece of gossip to prove the conspiracy. He also has a habit of exaggerating these points while ignoring the widespread evidence that counters his arguments, including from the Soviet archives. Furr is also guilty of pretty much every logical fallacy that you can imagine.

Furr also believes that Stalin was a secret democrat whose plans to democratize the Soviet Union were thwarted by NKVD chief Nikolai Yezhov. Blaming Yezhov allows Furr to exonerate Stalin for the severe violence of the purges. In fact, he believes that both NKVD chiefs Yagoda and Yezhov were in league with Trotsky. Even though two figures later unmasked as “enemies of the people” led the NKVD during the period of the Moscow Trials, Furr doesn’t believe that this calls into question the verdicts. He thinks Yagoda and Yezhov were spies, but the evidence they produced was still reliable.

But I don’t think Furr is actually the most clownish defender of Stalin. One other person I cover is Bill Bland, who was a follower of Enver Hoxha. Bland not only defends Stalin but essentially declares him to be a divine being. Bland is the closest you see to the transformation of Stalinism into a religion. To my knowledge, Furr has not yet done that.

Stalinists believe they discovered the largest conspiracy in world history: hundreds of thousands of communists working with an array of imperialist powers, their sworn enemies. And even 80 years later, no one has found even a single scrap of paper offering proof. This is amazing when you consider that the archives of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan ended up in the hands of their enemies.

You’re correct that no proof exists anywhere about the “Trotskyite-Fascist” conspiracy. No one has unearthed anything in the archives of the USSR, Poland, Germany, or Japan. Nor were high-ranking Nazis charged with anything relating to the Moscow Trials at Nuremberg, even though the Soviet Union had judges there.

Even though there was no proof of a “Trotskyite-Fascist” conspiracy, Communist Party members around the world believed it. If Stalin represented truth and progress, then Trotsky stood for falsehood and fascism. They acted upon it with tragic results. Throughout my book, I detail the rhetoric that you heard from Communist Party militants in France, Yugoslavia, Canada, and the United States condemning Trotsky as a hireling of fascism. I also show how this led to bloodletting in the Spanish Civil War, Trotsky’s murder, and the antisemitic show trials in Czechoslovakia. We can see the danger of what happens when people — even supposed Marxists — ignore objective truth and decide to act on a conspiracy theory.

There has been a certain growth of neo-Stalinism in recent years. How do you explain that? Is that what motivated you to write this book?

Anyone who has been online knows that weird people and even weirder ideas tend to find each other. You can see this with the most bizarre version of online neo-Stalinism which is “MAGA Communism” and the so-called American Communist Party. Although, I would argue the ACP is a degeneration of Stalinism toward more openly fascist positions.

Certainly, the persistence and growth of Marxist-Leninist parties was a motivation for me. Yet I was really motivated to write this book in order to combat the apologetics by Furr and others. Most people will ignore Furr, like we do with Holocaust deniers such as David Irving. Yet it is still necessary for someone to do the dirty work of exposing their falsehoods. No one has looked at Furr systematically and it was a necessary task. I will admit that the hardest part of this project was reading Furr’s whole corpus.

Beyond that, I think that there is a broader need to challenge neo-Stalinist ideas as part of a general struggle against irrationalism. In recent years, there has been an extraordinary growth in conspiracy theories and “alternative facts,” particularly in the United States. We’ve seen a resurgence of neo-Nazism and alt-right groups, who have all promoted various antisemitic conspiracy theories.

Many people understand the world through conspiracy theories. However, the methodology of conspiracism cannot allow us to actually know reality — it is akin to religious fundamentalism.

Neo-Stalinist conspiracism is a similar sort of conspiracism on the Left. And I believe that Marxists should train our members in reason and science — we are the true heirs to the heritage of the Radical Enlightenment, after all. Exposing the conspiracism of Losurdo, Martens, Bland, and Furr is a useful exercise in promoting critical thinking, materialist dialectics, and historical analysis. Always and everywhere, conspiracy theories are obstacles to reason and progress. If we want to really know the world, then we cannot use conspiracist nonsense. Rather, reason and historical truth can help us truly understand and change the world in the wider struggle for communism.

Doug Greene, In Stalin’s Shadow: Leon Trotsky and the Legacy of the Moscow Trials (London: Resistance Books, 2025), 272 pages, £18.

November 8, 2025

Grover Furr’s Medieval Stalinism

Originally published by Left Voice.

In the medieval era, guilt or innocence was often determined through trial by ordeal. One of the most notorious forms occurred when the accused was bound by their hands and feet, then cast into the water. If he sank, then he was presumed innocent; if he floated then he was found guilty. In other words, you were damned either way.

Unlike the modern justice system, trial by ordeal was not based on reason or evidence, but on the supernatural and the irrational. The governing rationale was that an all-powerful, all-seeing, and just God would not allow the innocent to be falsely condemned but would intervene by a miracle to determine the truth.

While trial by ordeal and other forms of medieval jurisprudence have been discarded in the modern world, they made a stunning reappearance in the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin. During the Great Terror of the 1930s, the Soviet leader launched a series of public show trials to eliminate potential opposition inside the Communist Party. The trials had all the hallmarks of a medieval inquisition by extorting confessions from leading Bolsheviks that they were guilty of crimes of sabotage, terrorism, and espionage in league with Leon Trotsky and fascist powers. Nor was the trial by ordeal missing from this Stalinist Terror. Pledges by former oppositionists accepting the party line were now viewed by Stalin as insincere double-dealing to hide their real guilt while confessions at trial would only serve to ensure severe punishment if not death.

Longtime Stalin apologist – and (ironically) medieval literature professor – Grover Furr finds himself defending the Moscow Trials in his latest work, Khristian Rakovsky – Trotsky’s Japanese Spy (2025). This particular work focuses on the Bolshevik revolutionary and Soviet official Christian Rakovsky (1873-1941). Rakovsky was one of the central defendants at the Third Moscow Trial of 1938 where he confessed to working with the Japanese Empire on behalf of Leon Trotsky. According to Furr, both Rakovsky and Trotsky were guilty as charged: “A great deal of evidence establishes Trotsky’s and Rakovsky’s guilt. There is no evidence that refutes it.” (13) However, a close examination reveals that not only does Furr lack any evidence, but he indulges in irrationalism and conspiratorial thinking. Like earlier Holy Inquisitors, he finds himself defending “trial by ordeal,” albeit replacing God with the General Secretary.

Stalin’s Holy InquisitorTo make his case, Furr relies almost exclusively upon confessions from Rakovsky and others extracted from the Soviet NKVD. In fact, at least a third of the book consists of lengthy transcripts of interrogations and confessions. Contrary to the bulk of historical scholarship, Furr claims that Rakovsky and others freely confessed to the NKVD without any form of coercion or threats akin to an auto-da-fé: “No one has ever presented any evidence that the defendants’ testimony was compelled by torture or threats, or that the defendants were innocent of the crimes to which they confessed at trial. No one, ever.” (12)

In actuality, Furr ignores mountains of evidence regarding widespread abuses, threats, and torture conducted by the Soviet security forces. A cursory look at The Road to Terror (1999), edited by J. Arch Getty and Oleg V. Naumov, provides ample details from the Soviet Archives. For instance, the NKVD authorized quotas for mass arrests in July 1937. This was part of an official police campaign in which thousands were arrested in a frenzied atmosphere of mass hysteria and false denunciations. The documents also show that torture was widely practiced by the NKVD. Moreover, the NKVD had orders with detailed instructions on the punishment and surveillance of families of suspects. It should also be noted that the historian Oleg Khlevniuk demonstrates in his history of the gulag that confessions were often falsified by the police.

It stands to reason that Rakovsky and others in police custody could expect to be handled roughly. While it was true that the defendants at the Moscow Trials such as Rakovsky were not physically tortured — this would have made the frame-up too obvious — they were still clearly under threat. Even if Rakovsky was not physically harmed, his confessions occurred in a society where torture and mass arrests of innocent people were pervasive. Documentary proof of such practices casts doubts upon the reliability of confessions and the entire Soviet justice system. In other words, the bulk of Furr’s “evidence” is utterly worthless.

Furthermore, Rakovsky’s confessions are useless without any form of corroboration. For example, let us assume that a suspect in police custody confesses to multiple murders. Afterward, the suspect shows the police where the bodies are buried. In this case, the confession’s validity is confirmed by revealing other corroborating evidence. A confession without corroborating evidence raises the immediate question that the accused were coerced to incriminate themselves. During the Moscow Trials, no corroborating evidence was offered to substantiate any of the confessions. Absent any corroborating evidence, we are left only with Furr’s faith in the immaculate integrity of the Soviet judicial system under Stalin and Vyshinsky.

Furr’s Burn BookLike a true Holy Inquisitor, Furr does not let a lack of proof dissuade him. He argues even if there is no evidence that this does not mean Trotsky and Rakovsky were not spies: “Suppose there were no evidence that Trotsky collaborated with Germany and Japan? Would that mean Trotsky did not collaborate? No, it wouldn’t.” (11) Furr claims that since Trotsky and Rakovsky were adept conspirators, they were careful to leave no evidence behind. So successful were they that no evidence for this wide-ranging conspiracy can be found in any archive in the world. That means the best proof for their conspiracy is that there is no proof at all. Based on Furr’s approach, we could equally conclude that Darth Vader and angels are real.Since he has no physical proof, Furr utilizes various forms of circumstantial evidence to make his case: “When there is enough of it, circumstantial evidence is the most powerful evidence there is.” (6) This usage of circumstantial evidence is where the Holy Inquisitor meets the high school mean girl. Throughout this text, all sorts of anecdotes, rumors, hearsay and gossip are thrown at the reader. Yet this is utterly irrelevant to the main point that Furr is making and merely serves to hide that he has no proof. In effect, Furr’s Khristian Rakovsky functions like the Burn Book from the film Mean Girls, a book filled with malicious gossip. Yet, unlike Furr, Regina George was more careful in substantiating the rumors in the Burn Book.Irrationalist ThinkingAt the heart of his methodology, Furr utilizes many logical fallacies to make his case. Those interested in a more thorough overview of Furr and logical fallacies should read my book, In Stalin’s Shadow: Leon Trotsky and the Legacy of the Moscow Trials . For now, we will discuss the fallacy of Post Hoc. This is the idea that any event must have been caused by an earlier event since it happened later. When Furr claims that Trotsky’s successful prediction of the accusations that Stalin would later accuse both him and Rakovsky of, this was proof that Trotsky was actually guilty of conspiracy:Given all the evidence we now have, the best explanation both for Rakovsky’s confession that he agreed to work with Japanese intelligence and for Trotsky’s uncannily specific and accurate “prediction” that Rakovsky would admit this, is that it was true… We have also seen how Trotsky used the stratagem of “exposing the scheme in advance” many times. He did this in an attempt to ward off, in advance, accusations that he could be reasonably certain would be forthcoming. Trotsky could not prevent the Soviet prosecution from uncovering and exposing his, Trotsky’s, conspiratorial activities. What he could do was to claim that these accusations were so transparently false that he could even “predict” them in advance. (175 and 185)

Just because Trotsky made a prediction before an event came to pass does not mean he was working with the Japanese. There are no grounds for making this connection. By contrast, does Furr ever consider that Trotsky was just a perceptive observer of Stalin’s methods?

Double Dealer Like the Holy Inquisition, the Moscow Trials aimed to combat heresy, apostasy, and blasphemy that challenged the reigning orthodoxy. Just as the Devil could quote scripture for his own purpose, enemies of the people in the USSR practiced “double-dealing” or hiding their nefarious “Trotskyite-Fascist” aims while feigning Marxist-Leninist orthodoxy. This is precisely what Furr accuses Rakovsky of doing when he gave up oppositional activity and accepted the party-line: “All the capitulators were dvulichnye – “two-faced,” hypocritical, and had “capitulated” in order to gain reinstatement in the Party where they could continue their conspiracy.” (29) For Furr, double dealing meant that Rakovsky now faced his own trial by ordeal – damned if he capitulates or shot if he confesses.Yet why was Rakovsky lying when he capitulated and not when he confessed? If Rakovsky is a practiced liar, then how does Furr determine when he was telling the truth? Whereas medieval judges looked to God to determine guilt or innocence, Furr uses Stalin as the supreme arbiter on the truth. According to the General Secretary: “We have drawn a conclusion: Do not take former oppositionists at their word.” (38) This holy writ enables Furr to conclude that all protestations of loyalty by former oppositionists such as Rakovsky were just an elaborate ruse. To pronounce a verdict on Rakovsky’s trial by ordeal, Furr utilizes the approach of George Costanza from the sitcom Seinfeld, which we can paraphrase as follows: “Just remember, it’s not a lie if Stalin believes it.”

Yet Furr’s method for determining truth can only work if you accept Stalin’s word as gospel. To convince the rest of us, Furr is forced to invent more elaborate conspiracy theories to exculpate Stalin. In fact, he claims that NKVD chiefs Genrikh Yagoda and Nikolai Yezhov were actually enemies of the people in league with Trotsky (200). If Furr genuinely believes that the NKVD was led by enemies of the people who arrested and tortured innocent people, then shouldn’t this cast doubt on Rakovsky’s confession and the verdicts of the Moscow Trials? That is a question Furr cannot rationally answer since it blows apart his whole faith-based narrative.

Reject the Trial by OrdealLike all his other books, this one is poorly written, difficult to follow, and overly repetitive. There is no bibliography provided, not that it matters since Furr has no evidence beyond coerced confessions. Even as a Stalinist apologist, Furr does a poor job.While Furr claims to be an objective researcher, he has more in common with a medieval judge than a scientific socialist. Throughout his work, the reader is bombarded with irrationalism, logical fallacies, and a conspiratorial mindset. Evidence is replaced by faith. Truth no longer corresponds with objective reality, but with the pronouncements of the Soviet General Secretary. What Furr has produced in all his work is pseudo-scholarship dressed up as science and truth. Marxists should recognize Furr’s work for the nonsense that it is.

May 19, 2025

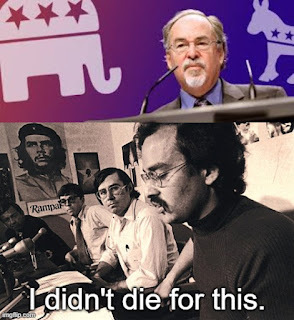

David Horowitz: Not a Hero, But He Did Live Long Enough to Become a Villain

Originally published at Left Voice.

In 2024, the elderly David Horowitz was bedridden and severely weakened by cancer. He did not have much time left. Yet in his twilight months, Horowitz received a phone call in his hospital room. The man on the receiving end was presidential candidate Donald Trump, who was then meeting with Horowitz’s son Benjamin. Trump told an enthusiastic David that they shared the same mission of restoring American greatness and freedom. When Horowitz died on April 29, 2025, he was undoubtedly happy watching President Trump realize his — or rather their — reactionary agenda.

A Class WarriorHorowitz was not always this way though. He was born on January 10, 1939, in the Forest Hills neighborhood of Queens, New York to a family of Jewish Communist Party members. According to Horowitz, even though his parents had emigrated to the United States, they wanted to destroy their adopted homeland: “In the land of Washington and Lincoln, their heroes were Marx and Lenin; in democratic America, their goal was to establish a “dictatorship of the proletariat.” Instead of being grateful to a nation that had provided them with economic opportunity and refuge, they wanted to overthrow its governing institutions and replace them with a Soviet state.”1

Horowitz is unintentionally ironic in portraying his parents as dedicated communist revolutionaries. By the time he came of age, the Communist Party (CP) was thoroughly Stalinized and had largely abandoned revolution for the needs of Soviet foreign policy. Despite the CP’s degeneration, as a red diaper baby, David did receive the rudiments of a political education where he absorbed the values of socialism. In 1949, just as the Second Red Scare chilled politics across the United States, a defiant ten-year-old David attended his first May Day demonstration. Afterward, he viewed himself “as a soldier in an international class struggle that would one day liberate all humanity from poverty, oppression, racism and war.”2

Yet Horowitz had his faith in the USSR shattered in 1956 with Khrushchev’s Secret Speech revealing Stalin’s many crimes. Later, he described his parents essentially losing their reason for being: “When my parents and their friends opened the morning Times and read its text, their world collapsed—and along with it their will to struggle. If the document was true, almost everything they had said and believed was false. Their secret mission had led them into waters so deep that its tide had overwhelmed them, taking with it the very meaning of their lives.”3

By now, Horowitz was a freshman at Columbia University as his family’s Communist Party milieu fell apart. In the coming years, Horowitz maintained his socialist convictions but largely focused on literary studies. One result of his literary pursuits was his second book, Shakespeare: An Existential View (1965).

After graduating in 1959, he moved to California, where he began graduate studies in English literature at the University of California, Berkeley. It was an auspicious choice. Shortly thereafter, Berkeley became the center of New Left and radical activism that challenged the American war in Vietnam. Attracted to the movement, Horowitz organized one of the first campus demonstrations against the Vietnam War in 1962. That same year, he published Student, an early New Left text.

Afterward, Horowitz and his family moved to Sweden where he spent the next year. During this time, he wrote The Free World Colossus: A Critique of American Foreign Policy in the Cold War (1965). In this seminal work, Horowitz attacked the prevailing anticommunist consensus that the Soviet Union was an expansionist power and the cause of the Cold War. Rather, Horowitz located the cause of the Cold War in American capitalists and imperialist aggression. Very soon, Free World Colossus proved to be a must-read text for a new generation of radicals and was translated into multiple languages. Later, Horowitz disowned his work for legitimizing a radical worldview:

MentorsThe biggest impact that my political books had would be Free World Colossus which sold about 20,000 copies over a decade. It had a very, I feel, unfortunate influence because it persuaded a lot of people of the validity of a radical perspective – which I now consider to be both false and pernicious – on the cold war, because it was used in the universities and still probably has some influence in leftist writings about the cold war.4

It was during this same period that Horowitz was offered a job with the Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation in London. At this time, Russell became involved in activism against the Vietnam War. In 1966, Ralph Schoenman convinced Bertrand Russell to bring together a war crimes tribunal to judge American involvement in the Vietnam War. Alongside Russell, those attending were some of the major figures of the international left such as Isaac Deutscher, Jean-Paul Sartre, Stokely Carmichael, Simone de Beauvoir, Vladimir Dedijer, and James Baldwin. Horowitz himself claimed later that he had reservations about the tribunal and did not take part. Yet Horowitz also admitted that he was essential in helping the tribunal by raising funds. Horowitz also participated in other actions against the war. Alongside members of the Trotskyist International Marxist Group such as Tariq Ali, he helped organize the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign in 1966.

While in London, he became close friends with two major European Marxists: Ralph Miliband (author of Parliamentary Socialism) and Isaac Deutscher, the famed biographer of both Trotsky and Stalin. Deutscher was an important political mentor to Horowitz and many radicals, introducing them to the revolutionary tenets of classical Marxism. As Horowitz said in 1969 in a collection he edited commemorating Deutscher: “It was Deutscher’s unique achievement that he constructed in his exile a Marxist vision of Bolshevism and its fate, which could serve as a bridge between the tradition and achievements of the old revolutionary left and the new… and of restoring meaning once again to the idea of Communism.”5

In addition, Horowitz’s Empire and Revolution (1969) was dedicated to Deutscher and bore his influence throughout its pages. In this text, Horowitz reinterpreted the Cold War, imperialism, and the USSR under a Deutscherite lens. Despite the deformations of Stalinism in the Soviet Union, he maintained hope that the workers would overthrow the ruling bureaucracy. Finally, the text ended with an unambiguous Bolshevik call for international revolution:

Rampartsthe continuing world-wide oppression of class, nation and race, the incalculable waste and untold misery, the unending destruction and preparation for destruction and the permanent threat to democratic order that characterize the rule of capitalism… Liberation is no longer, and can be no longer, merely a national concern. The dimension of the struggle, as Lenin and the Bolsheviks so clearly saw, is international: its road is the socialist revolution.6

Having returned to the United States and settled in California by 1968, Horowitz became a co-editor of the magazine Ramparts. One of the major radical journals of the sixties, Ramparts sold nearly 250,000 copies at its height. The journal published many of the most important leftist texts of the decade such as Che Guevara’s Bolivian Diaries, with an introduction by Fidel Castro and Soul on Ice by the Black Panther Eldridge Cleaver (later a writer for the journal). In 1967, when Martin Luther King Jr. publicly opposed the Vietnam War, he gave Ramparts the sole rights to publish the text of his speech.

This was an easy choice on King’s part since the main thrust of Ramparts’ energies were focused on opposing the Vietnam War. In its pages, the journal condemned various American war crimes in Vietnam such as the use of napalm. Moreover, Ramparts was instrumental in exposing the role of the CIA with the National Student Association, Radio Free Europe, Radio Liberty and the Asia Foundation.

Years later, Horowitz sorrowfully described his actions during the sixties:

While American boys were dying overseas, we spat on the flag, broke the law, denigrated and disrupted the institutions of government and education, gave comfort and aid (even revealing classified secrets) to the enemy. Some of us provided a protective propaganda shield for Hanoi’s communist regime while it tortured American fliers; others engaged in violent sabotage against the war effort.7

While he exaggerates and torture should not be condoned, Horowitz and Ramparts clearly did good work throughout these years.

Keynes and MarxWhile penning articles on the global uprisings of 1968, Horowitz also considered himself a revolutionary theorist. He wrote prolifically — the only constant in his career — editing books on corporations, history, the counterculture, the Cold War, and economics. Regarding economics, Horowitz hoped to establish the centrality of Marxism in understanding capitalism and crisis:

Nonetheless, at this historical juncture the traditional Marxist paradigm is the only economic paradigm which is capable of analyzing capitalism as an historically specific, class-determined social formation. As such it provides an indispensable framework for understanding the development and crisis of the present social system and, as an intellectual outlook, would occupy a prime place in any scientific institution worthy of the name.8

Despite proclaiming his adherence to Marxist political economy, Horowitz’s views were very unorthodox. In fact, he was quite animated by the Keynesian-style Marxism found in Paul Baran and Paul Sweezy’s Monopoly Capital (1966). This work ditched key components of Marx’s Capital such as the tendency of the rate of profit to fall and the theory of surplus value by replacing it with Keynes’ concept of economic surplus.

The high point of Horowitz’s engagement with this heterodox school can be found in his edited collection, Marx and Modern Economics (1968). Here, Horowitz summarizes a great deal of literature on the relationship between Marxism and bourgeois economists. In his introduction, Horowitz sees the possibility of a convergence between Marxism and mainstream economics through the medium of Keynes. This is reflected in the choice of chapters which include leftists influenced by Keynes such as Joan Robinson, Oskar Lange, Paul Sweezy, and Paul Baran. The introduction approvingly quoted Robinson: “If there is any hope of progress in economics at all, it must be in using academic methods to solve the problems posed by Marx.” Horowitz added: “It is the Marxists, alone, who have been ready to take up the challenge.”9

While Horowitz’s own revolutionary commitments remained intact, his embrace of Keynes was an early sign of a rightward shift. Like Sweezy and Baran, Horowitz dropped the essentials of Marxist political economy for bourgeois liberalism. As a result, he was unable to explain the material necessity for socialism that grew out of capitalism’s internal laws of motion. Horowitz, like Baran and Sweezy, was forced to deny the revolutionary role of the working class and look for salvation from amorphous “outcasts.” While his understanding of socialism was not scientifically grounded, Horowitz’s revolutionary faith meant he refused to give up the struggle.

By the early seventies, radicalism was beginning to lose steam. The mass movements of the previous decade began to shrink and horizons for a socialist future receded. Unknown to Horowitz and others, an era of conservative retrenchment was about to begin. While many leftists began to question the validity of socialism altogether, Horowitz attempted to carry on but was feeling the strain too. As he admitted in The Fate of Midas (1973): “In the present historical context, the work of a radical intellectual is inevitably a lonely enterprise10

In addition, the publication of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago with its exposure of the Stalinist gulag further shook Horowitz’s commitments: “I had grown up in an environment where the Soviet Union was the focus of all progressive hopes and political efforts. My acute sense of our complicity in these crimes made it difficult for me to read more than a few pages of Solzhenitsyn’s text at a single sitting.”11

While burdened and strained, Horowitz pressed on. By the early seventies, he developed a close friendship with Huey P. Newton, leader of the Black Panther Party. Even though the Panthers were one of the most militant groups of the sixties, they were now in deep decline due to COINTELPRO repression and internal infighting. In many respects, both Newton and the Panthers had severely degenerated. Yet Horowitz was convinced by Newton that the Panthers were leaving behind their simplistic violence and embracing a more creative politics focused on community service.

As Horowitz worked with the Panthers to fundraise, he introduced a friend named Betty Van Patter to work as their bookkeeper. In December 1974, Van Patter went missing. A month later, her broken and decomposed body was found in San Francisco Bay. Almost immediately, Horowitz believed that the Panthers were responsible for her murder.

Along with the waning radical movement and his growing doubts about socialism, this was Horowitz’s breaking point. His whole identity and dedication to Marxism shattered:

Second ThoughtsThe Marxist idea, to which I had devoted my entire intellectual life and work, was false… For the first time in my conscious life I was looking at myself in my human nakedness, without the support of revolutionary hopes, without the faith in a revolutionary future —without the sense of self-importance conferred by the role I would play in remaking the world. For the first time in my life I confronted myself as I really was in the endless march of human coming and going. I was nothing.12

Over the following decade, Horowitz largely withdrew from active politics. In addition to Van Patter’s murder, he was also going through a bitter divorce with his wife after an affair with Abby Rockefeller (while working on a study of the Rockefeller Family). For the time being, Horowitz retreated and attempted to rebuild his life.

In March 1985, he finally came out from the cold. Horowitz and his former Ramparts collaborator Peter Collier published an essay for the Washington Post called “Goodbye to All That,” where they announced their conversion to Ronald Reagan’s anticommunist crusade. According to Horowitz and Collier, “communism is simply left-wing fascism” and the USSR was an “evil empire.”13

With the fervor of a newly minted convert, Horowitz was compelled to preach his new anticommunist gospel. In 1987, he found himself in Nicaragua at the behest of Elliott Abrams, an Assistant Secretary of State, to oppose the leftwing Sandinista government. While there, he cheered on the Contras — right-wing terrorists backed by the U.S. — who had murdered 30,000 Nicaraguans. Two years later, Horowitz attended a conference in Kraków, Poland calling for the end of Communism and praising the “wisdom” of free market fundamentalist Friedrich von Hayek.

In 1987, Horowitz hosted a “Second Thoughts Conference” in Washington, D.C. composed of former leftists such as Ronald Radosh, Joshua Muravchik, Fausto Amador, and P. J. O’Rouke. The attendees spent their time repenting for their radical sins and warning about the ever-present dangers of “communist totalitarianism.” As the radical journalist Alexander Cockburn observed, the Second Thoughts Conference was merely an opportunity for Horowitz and company to cash in:

The Poor PlagiarizerThen [Horowitz and Collier] decided to become right-wingers and jumped on the Reagan bandwagon at more or less exactly the moment it ran finally out of steam. Since then they have gone around sucking money out of right-wing foundations in the cause of something called Second Thoughts. The less people have any interest in what they say, the crazier they’ve become, which is usually the case with self-advertising turncoats.14

The last forty years of Horowitz’s life was spent as a reactionary attack dog. He founded a number of conservative foundations that received generous donations from rightwing donors. During the “War on Terror,” Horowitz was second-to-none in his attacks on the political left for treason. While Horowitz bemoaned leftist “cancel culture” and their supposed attacks on free speech on college campuses, his “academic bill of rights” was an aggressive attempt to expose leftist teachers and drive them from academia. Naturally, he was now a rabid Zionist, homophobe, and racist. Let no one say that Horowitz did not go all in.

While Horowitz remained productive up to the very end, nothing of his later works bears any originality. His defenses of conservative politics sound more like Fox News soundbites than something written by Edmund Burke. His analytical abilities clearly declined with his apostasy. As a leftist, Horowitz was clearly aware of the differences that separated Marxists from the bourgeois imperialists of the Democratic Party. As a conservative, he lumped them all together and the Democrats appeared as another radical organization hellbent on destroying America. It is a notion that the Horowitz of 1968 would have scoffed at due to its sheer stupidity.

As part of his new conservative branding, Horowitz never missed an opportunity to tout his credentials as an ex-Marxist. This produced one of the few post-1974 works of Horowitz worth reading, his memoir Radical Son (1997). At times, Horowitz can be intimate in recounting his thinking and the various episodes of his life. Yet the reasons for abandoning his former convictions are incredibly hollow and unoriginal. Horowitz comes off as a poor plagiarizer of J. L. Talmon, Whittaker Chambers, and Fyodor Dostoevsky where he bemoans the communist left for rejecting original sin and deifying man’s reason in its place which will inevitably end in terror and totalitarianism.

As a Marxist, Horowitz was no orthodox theorist, but he did make genuine contributions in works such as Free World Colossus. And even his heterodox beliefs were part of a sincere revolutionary commitment against exploitation and oppression. During the sixties, Horowitz’s writing showcased many of the best traits of an engaged Marxist intellectual — insightful, rigorous, accessible, and overtly partisan. While Horowitz’s writings and actions from his later period showcased an equally extreme partisanship, he produced almost nothing of any substance or value. Like many renegades before him, Horowitz travelled the familiar road from radical to reactionary. There was nothing remarkable distinguishing Horowitz’s rightward journey from so many others, except that he turned it into a very lucrative career in defense of the status quo.

Notes

Notes↑1David Horowitz, Radical Son: A Generational Odyssey (New York: The Free Press, 1997), 44.↑2David Horowitz, “Left Illusions,” in Left Illusions: An Intellectual Odyssey, ed. Jamie Glazov (Dallas: Spence Publishing Company, 2003), 102.↑3Horowitz 1997, 84.↑4Jennifer Waters, Michael Kirkpatrick and David Horowitz, “An Interview with David Horowitz,” Columbia: A Journal of Literature and Art No. 12 (1987): 97-98.↑5David Horowitz, ed., Isaac Deutscher: The Man and His Work (London: Macdonald, 1971), 9 and 14.↑6David Horowitz, Empire and Revolution: A Radical Interpretation of Contemporary History (New York: Random House, 1969), 258.↑7“My Vietnam Lessons,” in Horowitz 2003, 113.↑8David Horowitz, “Marxism and Its Place in Economic Science,” Berkeley Journal of Sociology Vol. 16 (1971-72): 57.↑9David Horowitz, ed., Marx and Modern Economics (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1968), 17.↑10David Horowitz, The Fate of Midas and Other Essays (San Francisco: Ramparts Press, Inc., 1973), 5.↑11Horowitz 1997, 193.↑12Ibid. 287.↑13David Horowitz and Peter Collier, “Goodbye to All That,” Powerline, November 8, 2013. https://www.powerlineblog.com/archive...↑14Alexander Cockburn, The Golden Age is in Us: Journeys and Encounters 1987-1994 (New York: Verso, 1995), 216.January 4, 2025

Lars Lih’s What was Bolshevism: The Trap of Continuity

Originally published by Left Voice.

The Canadian academic Lars Lih is an independent scholar of Soviet history with a particular focus on Lenin and Bolshevism. Lih’s magnum opus Lenin Rediscovered (2005) is a serious study of Lenin’s What is To Be Done? (WITBD), in which he challenged Cold War caricatures of the Bolshevik leader as an elitist bent on totalitarian domination. In this work, Lih proved that Lenin was a dedicated Marxist committed to the emancipation of the working class.

What Was Bolshevism? includes many of Lih’s previously published essays on Bolshevism and the Russian Revolution. The nineteen chapters cover a multitude of topics such as war communism, the New Economic Policy, Stalinism, and perestroika. In contrast to Lenin Rediscovered, Lih deemphasizes Lenin and focuses on leading communists such as Trotsky, Bukharin, Stalin, and Zinoviev to understand the meaning of Bolshevism. In erudite and accessible writing, Lih deconstructs longstanding myths on the Left and Right. Still, Lih cannot truly understand Bolshevism since his methodology is marred by textual formalism and an overemphasis on political continuity.

Bolshevism and KautskyismIn contrast to the rest of the book, Lih’s introductory chapter centers around Lenin and repeats his previous arguments on WITBD. Following Lenin Rediscovered, he claims both Cold Warriors and leftist activists have largely misunderstood Lenin since they considered WITBD to be the foundational text of Bolshevism. Rather, Lih claims that Bolshevism’s political ideas adhered to the orthodox Marxism of Karl Kautsky: “I assume the essential continuity of Bolshevism’s message from its beginnings… Much of my writing over the last decade or so has examined the case for the alleged ruptures in 1914 and 1917 and found them wanting.” (p. 4)

Lih argues that WITBD did not advocate a “party of a new type” or a vanguard organization of proletarian revolutionaries. Rather, Lenin’s political ideas followed the model of the German Social Democratic Party as codified by Karl Kautsky’s Erfurt Program: “This book defined Social Democracy for Russian activists – it was the book one read to find out what it meant to be a Social Democrat. In 1894, a young provincial revolutionary named Vladimir Ulianov translated The Erfurt Program into Russian just at the time he was acquiring his life-long identity as a revolutionary Social Democrat.” (p. 45)

Kautsky’s ideal was that social democracy should be the party of the whole class – embracing all tendencies of the working-class movement. The implication of Lenin’s arguments in WITBD was that the party could not be “a party of the whole class.” Due to the uneven nature of consciousness inside the working class, the party should seek to organize its advanced layers. This was not in order to create a conspiratorial organization, but because a disciplined and centralized party of Marxists could act more effectively in the working-class movement than a loose and undisciplined one.

Kautsky believed that the steady accumulation of votes and parliamentary seats by social democracy guaranteed victory, meaning the party did not have to engage in revolutionary action. In effect, history would inevitably go their way. In contrast to Kautsky’s “revolutionary” fatalism, Lenin’s approach was dominated by what Georg Lukács called the “actuality of revolution.” This meant he viewed every action by the party as crucial links in a chain leading to the goal of proletarian revolution. This viewpoint had drastic effects on how Lenin envisioned the role of a communist party. For Lenin, a vanguard party was not a vehicle for collecting votes, nor did it passively await the revolution. While revolution could only happen in certain situations, this did not mean that communists could not prepare for it now. It was imperative for the party to carry out revolutionary agitation in non-revolutionary situations in order to organize forces for when the moment of overturn arrived.

Lih notes the similarities between Lenin and Kautsky’s language, but he does not see the gulf that separated them in terms of action. German Social Democracy betrayed its socialist commitments in World War I and the German Revolution of 1918. By contrast, the Bolsheviks successfully mobilized the working class against capitalism and the Tsar. In both theory and practice, Bolshevism meant a repudiation of Kautsky’s Erfurtian politics.

If all Lih was doing was highlighting the influence of Kautsky on Lenin, then there would be no objection. Lenin himself recognized his political debt to Kautsky. Yet Lih goes further than that and stresses that there were few, if any, breaks in Lenin’s ideas. It is certainly true that Lenin emerged from within the Second International and used its language and formulations. However, he developed something radically new from that raw material. On a host of ideas ranging from the vanguard party, the state, imperialism, philosophy, and socialist revolution, Lenin’s Bolshevism was vastly different from Kautsky’s “Orthodox Marxism.”

As a result, Lih’s Kautskyization of Lenin transforms Bolshevism from a distinctive revolutionary current into just unoriginal followers of Kautsky and social democracy. In effect, this amounts to a delegitimization of Leninism and its replacement by Kautskyism. By stressing the aspect of continuity over discontinuity in Lenin, Lih cannot comprehend Bolshevism. Lih’s method is one devoid of dialectics, discontinuity, and ruptures. For those interested in a more in-depth discussion on the problems of Lih’s approach, I encourage you to read my The New Reformism and the Revival of Karl Kautsky which is summarized here.

War CommunismAt least half of Lih’s book is devoted to Bolshevik debates surrounding “war communism.” Following the October Revolution, the Bolsheviks were confronted with economic collapse, foreign invasion, and civil war. In response, Lenin, Trotsky, and the Soviet leadership implemented policies to militarize labor and requisition grain from the peasants in order to feed the army. These policies were known as “war communism.” Lih challenges the consensus on war communism from scholars such as Moshe Lewin, Isaac Deutscher, Sheila Fitzpatrick, Orlando Figes, and Martin Malia that see these policies as a deluded fantasy where the Bolsheviks genuinely believed they were entering communism itself: “The myth of a leap into communism, of euphoria-induced hallucination, of a ‘short-cut to communism’, of glorification of coercion as the royal road to communism, etc., is still dominant in most works that reach the larger reading public.” (p. 7)