Davey Davis's Blog

November 23, 2025

A return to form

Before Dallas, it had been almost a year since I’d fucked an anonymous man. I felt out of practice, for one thing. Then there was my approaching book launch, which was sapping my spare time and energy, and the mushrooming vacuum of normalcy on the hookup apps, and, perhaps most distractingly, my reluctance to really lean into what I’ve been calling “twink MILF,” a brand increasingly foisted on me by a certain kind of bro who doesn’t know what to do with an older fem other than be mothered1. (“Wow, 37! I love cougars 😏,” a guy one presidential term my junior recently told me.)

Still, there remain in the world men who are older than even I who can also use a smartphone unassisted, so when Dallas showed up on my grid I replied to his messages. There was a little sexting, but nothing very involved at first. I certainly liked looking at him, with his massive head—its Bardemesque proportions smooth and light brown, as if sanded from teak—his barrel chest, heavy arms, and tautly extrusive weightlifter’s belly. On bathroom breaks and in checkout lines, I delicately fished for the catch, but he never messaged me anything blockable. Perhaps his secret problem could only be discovered in person: bad dick, medieval hygiene, apartment littered with dead cats, etc. Although Dallas was exclusively interested in fem transsexuals and CDs, he didn’t behave like it, if you know what I mean, which I found suspicious.

But after a few weeks of idle chitchat, Dallas wasn’t waving any flags redder than “ambiguously hetero.” More importantly, he was flying a green one at full mast: he wanted to be very clear about what we would do together. Not as jerkoff fodder, or because he was seeking a laundry list of what he could expect from me (and therefore require of me, once we were all alone). He pursued my yeses and nos in a careful, curious way, the mark of a man who has had a lot of sex with damaged feminine people and understands that if he wants to keep doing so, he’d better learn how to put them at ease. And so it was decided.

I peed before I left, but on the train I realized I had to pee again, because of course I did. Well, I thought, I would simply wait until I got to his condo. Standing with my back to the car door, I practiced asking Dallas if I could use his bathroom, to which he would surely say, Yes, of course, right this way. But what if he jumped me at the threshold (not violently but eagerly, as sometimes happens), and I had to interrupt—creating an inauspicious test of the limits of his indulgence? What if he said, Sure, you can use the bathroom but only on the condition that you let me watch, and I said no—creating another test, another opportunity for a line to be crossed? I realized I was working myself up, but as the express shuddered down the length of Manhattan, the inexplicable pressure in my bladder got exponentially worse. Doubt that I could even make it to Dallas’s crept in. His messages weren’t helping. He was anxious to know when and where I was along the way to his place, which would have been my elusive red flag if I didn’t know that bottoms be flaking!

How to describe the urgent need to urinate? Aching crotch, heaving groin, stabbing surfeit? Squeezing the handrail until my knuckles burned, I tried to ignore it. When that didn’t work, I devoted my attention to the sensation, as if full-body awareness would lessen my discomfort, which didn’t work, either. My chest prickled, my palms clammed, my eyes darted around the train car, as if searching for signs of danger. Well, I thought, I would simply get off at Union Square and storm the Whole Foods. But the notion of hiking aboveground to gamble on secret door codes sounded harder and more humiliating than just dropping trou in a corner of the station, an option that I was, by now, seriously considering.

Then I remembered the Union Square bathroom, right off the L platform. I’ve seen it several times a week for years, always with a spiritual headshake, an internal tsk—just imagine the horrors in there! But one time, not too long ago, I witnessed a mother and her small child come out of the women’s and they had both seemed just fine. It is a very busy metropolitan train station, after all, with not just commuters but buskers belting “The Greatest Love of All” and homeless people pleading for mercy and fed up MTA employees glowering from their glass boxes. Surely there was at least one functioning pot to piss in?

At that point, I had no choice. When we reached 14th Street, I debarked and raced upstairs, my knees rubbing, my bag slung protectively over my abdomen. I couldn’t remember exactly where the bathroom was, at first, and was suppressing yet another spike of panic—had I imagined a train station bathroom, a Narnian liminal space for cruisers and users?—when I finally oriented myself. There it was, the door to the women’s wide open, its facilities hidden around a tiled corner. I pulled my hoodie over my headphones so no one could see my face or hair and charged through the door. It was a gamble, being what I am, but there was no way in hell I was going in the other one.

Below the lower lip of the first stall, a faux fur jacket was splayed on the floor. Next to it, a pair of feet were moving in a way that struck me as untraditional for bathroom business. Whatever! I took the adjacent stall and squatted ecstatically over the seat, only to discover that my water pressure was so high that only a few drops could escape at a time. I fought to relax, trying to picture every sphincter and muscle in my groin in a state of red-and-pink repose. I knew that all of this was real but also psychosomatic, that my tension and paranoia and racing heart were all symptoms of my fear of men—of Dallas, the unknown quantity—which over the years I’ve sublimated into my neurotic terror of sex-produced UTIs, a condition that for me manifests as a constant and irrepressible urge to pee, an anxiety which of course can’t be disentangled from my healthy transsexual fear of public restrooms, which of course can’t be cloven from my rage over America’s privatization of public space. I hate it here, I thought, my belly cramping as the stall next to mine mysteriously rattled and moaned.

It took a little longer than expected, but I eventually got it all out. As I trotted back downstairs, my mood skyrocketed. I’m safe, I reminded myself (something that therapists are always telling me to do), and I’m entering a situation that is also reasonably safe, because I can trust myself to determine that Dallas is normal (choosing to ignore, for the moment, the lapses in this ability that led to my year off from fucking anonymous men in the first place.)

Dallas looked exactly like his photos. Hoping I looked like mine, I hugged him, then followed him past a display of four or five electric guitars, a gargantuan sectional couch, and an elephantine entertainment system with an Employee of the Month placard perched on top. In the bedroom awaited a delicious king-size bed (but of course—he must have had 100 pounds on me). His chest and nipples were hard, but his mouth was soft, maybe too soft, perhaps because it was so big relative to mine. While he was decisive in his movements, moving my body with the ease that I do my phone, he was gentle; he choked me only briefly, as if to demonstrate that he could, like a flight attendant holding the oxygen mask to her face before takeoff. Like his face, his cock was exactly as it was in his photos: thick, uncut, not too long. It fit perfectly down my throat, by which I mean that it was big enough to make my eyes water and my nose run. Gag, drool, spit—a crowd pleaser.

After a while, he picked me up and placed me on the bed. He sucked too hard on my clit, but when I told him so, he modulated his technique. This made me happy, which is not the same thing as aroused, but not so different, either; I don’t like receiving head, but I let guys do it because it’s easier than having a conversation about it. Having overcome something together, after a few minutes I felt sturdy enough to tell him I was done. He raced for the condom, put it on, and pressed it in. So tight, he said. His cock felt good. I suddenly remembered that I can get pregnant, that I require condoms with men not just for chlamydia and all that—which I got sick of dealing with, and anyway I’m terrified of overusing antibiotics—but because I’m not on birth control and don’t want to be. As I was imagining our big-headed baby, Dallas did what they all do and threw my legs over his ox-like shoulders to penetrate deeper, harder, faster. It hurt. (What must it feel like to be so big and male and top? It’s probably like snorting a line of coke every time you recall that you can pull your lover apart like fresh monkey bread.)

I just laid there, freeing myself from the responsibility of verbal communication, awaiting my body’s choices with something like excitement. Here is what it did for Dallas: it braced itself against the mattress. It squirmed on the sheets. It threw back its head. It closed its eyes. It used its hands to push away his over-developed pectorals. It emitted the enigmatically porny noises that men decide to recognize or not.

Dallas’s thrusts suddenly changed, becoming so small and slow that he could barely have been said to be fucking me. He turned his face, which was pressed against mine, so he could feel my tears on his own cheeks, as if the water were a seam connecting us. Very slow, very shallow, one calloused hand cradling my neck. My movements had changed, too, but only in degree. It felt good to struggle against a big, strong man who did not want to harm me. My shoulders fell back to the mattress and my legs relaxed. He sped up again without going as deep, and that felt good, too. I noticed my fingers, which could feel his rocky shoulders and bristly arms. I moved them downward, and now his ass was under my palms, strong muscle under slightly sagging skin; my body, too, was soft and athletic, disintegrating against time, only a few decades behind him.

After a while, Dallas flipped me over. I waited tensely on all fours, a little apprehensive of the force he could generate on his knees. But after just a few strokes, he told me to lie on my belly and close my legs. I knew this was a signal that he wanted to finish, and I, too, was ready to go home, but this vaguely irritated me. In my experience, this is a favored position among chasers who prefer someone with a different anatomy from mine because it both tightens the hole, so it’s easier to cum (damn those condoms, the foe of middle-aged fuckers everywhere!), and obscures the fact that I have a vagina. Or so I think.

I didn’t realize that Dallas had finished until he pulled away laughing, listing like a sailing ship, to land on his back beside me. He stroked his softening cock through the condom, a little custard puddled in the hollow tip, but I told him I had to go. Still, for a few minutes we laid beside each other. Catching our breath, we complimented each other’s bodies and discussed the importance of a hookup’s “energy,” a topic that Dallas was passionate about. See, you get it! he exclaimed. If we’re not thinking positive, then what are we doing here? Life is too short.

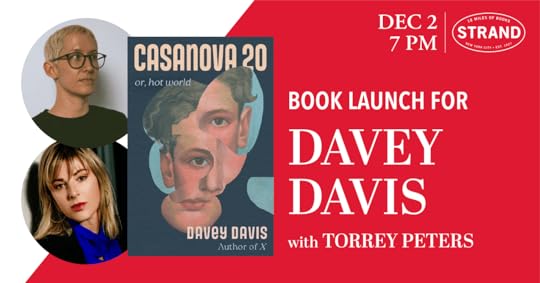

New York, come to my book launch with Torrey Peters on December 2!!! Boston, come to my reading with Gretchen Felker-Martin on December 5!!! More events to come…

My subscribers allow me to keep publishing work that’s mostly free for everyone, so thank you kindly for your support. You can also like and share my posts, preorder Casanova 20: Or, Hot World, or find me on Twitter, Instagram, and Bluesky.

1I’m way too old to be a twink and not at all in the aesthetic realm of what most people think of as MILFdom (much less equipped with children, biological or otherwise), but I’m playing the transgender card for this one.

November 14, 2025

Come to my book launch!

As anyone who’s seen her live knows, my friend Torrey is dynamite in front of an audience (and a good sport, too). She’s generously agreed to help me host the launch of Casanova 20: Or, Hot World in just a few weeks. Please come! Please mask! See you soon. 💋💋💋

My subscribers allow me to keep publishing work that’s mostly free for everyone, so thank you kindly for your support. You can also like and share my posts, preorder Casanova 20: Or, Hot World, or find me on Twitter, Instagram, and Bluesky.

November 12, 2025

"I don't owe you androgyny!"

November 2, 2025

Why publishing a book feels so bad

Preorder her!

Preorder her!A few months ago, Charlotte Shane emailed asking for contributions to a piece that went on to be called, “The Mortifying Ordeal of Being Published.” I totally meant to reply but, being in the midst of that very same kind of mortification, didn’t. (I was also moving apartments while suffering from the worst facial acne of my life.) Despite my best intentions, I didn’t add my .02 to the wise, funny, and occasionally heartbreaking reflections of my colleagues who, like me, prized open the Lament Configuration—some for the second or third or even eighth time—expecting something other than. . . all this.1

Not that they don’t have it covered. Being a working writer is “batshit and hard,” as Lydia Kiesling so succinctly puts it. It’s “vulnerable” (Rumaan Alam), leaving you “embarrassed” (Arianna Rebolini), “anxiogenic” (Daniel Lavery, always good for a vocab word), and “wrecked” (Larissa Pham)2. As seriously as I take my work and as earnestly as I wish for recognition—or at least a thoughtful, dedicated cohort of readers, perhaps based somewhere my sensibility is truly understood, like David Lynch in France or Nicole Kidman in the United States3—the marketing side of things never feels worth it, even if I don’t have any regrets, when it’s all said and done. I’ve started to wonder if loathing this process, especially the promotional part, isn’t actually a coping mechanism in itself. Because if I focus on the unique shittiness of hitting the digital streets, proferred fedora in hand, to pitch, schedule, and solicit, it’s easy to overlook how humiliating it is to spend your time a/b testing gimmicks that will convince consumers to spend their hard-earned money on your little wedge of the reaction economy4.

But like I said, no regrets. Not regarding my chosen profession, anyway. You know I like to play the martyr (I’m an artist, baby!). And there’s this, too: while it can foster the bad kind of navel-gazing, writing novels has also made me aware of just how many people it takes to make a single book happen. From the agents and editors and production workers, to the booksellers and librarians, to the critics and readers, all of these people are spending hours of their lives, if not longer, on something that someone else created. I’d like to think that this awareness has made me a better literary citizen, more curious and generous and supportive of others’ work. This has, in turn, enriched my life more than writing a novel (an intensely pleasurable but solitary activity that is incomplete without not just an audience but a social rendering) ever could. It reinforces for me, over and again, that I don’t write for myself, but for others; don’t wish to be alone, but together.

So, now that we’re a month away from publication, some housekeeping:

So, now that we’re a month away from publication, some housekeeping:Everyone is saying that you should preorder my book? Casanova 20: Or, Hot World is “intoxicating,” and “Jamesian”; it’s not to be missed and slamming mortality against our deepest desires. While Publishers Weekly described it as “fascinating if at times frustrating,” Kirkus gave it a starred review, calling Casanova “[a] show-stopping novel that carries within it a quiet, steadfast heart.”5 The only way to find out if the hype is real is to buy a copy for yourself and convene a book club with everyone you know.

Yes, there will be readings: I’ll be at Strand in NYC with Torrey Peters on December 2, Riffraff Books in Providence with Matthew Lawrence on December 4, and All She Wrote Books in Somerville with. . . someone. . . on December 5. There may be more East Coast dates before Christmas, but the rest of the tour doesn’t pick back up until January, when I’ll be making a stop in Hudson and then, at some point, the West Coast. I’m sorry that I don’t know the full plan yet, but Catapult is a small publisher—if you send the right person an email, me and my Xanax prescription could end up at your local queer bookstore.

My subscribers allow me to keep publishing work that’s mostly free for everyone, so thank you kindly for your support. You can also like and share my posts, preorder Casanova 20: Or, Hot World, or find me on Twitter, Instagram, and Bluesky.

Until my recent move, I was involved with North Brooklyn Mutual Aid, a network of nearly 2,000 neighbors committed to supporting their community with food, PPE, and essential goods distribution. With November SNAP benefits expiring thanks to the government shutdown, local orgs like NBkMA are more needed than ever. Screenshot your donation of any amount to NBkMA and I’ll send you a free month of subscriber-only DAVID content.

1While reviewing this newsletter one final time before pushing SEND, I realized that my last post was also about something Charlotte wrote. I’m sorry, everyone, for being so weird. In my defense, she did publish my first book.

2If you were following along with last week’s gooner discourse, please go read Danny’s roundtable on credulity, sexual kayfabe, and the people sexuality wasn’t supposed to ruin.

3Last summer, I met an Australian who told me that the American obsession with Kidman is completely befuddling for her countrymen. Can you believe!

4“Attention economy” is Sam Bodrojan’s clever coin.

5You know I hate pitting two divas against each other 🎭

October 19, 2025

Life on the desert island

Years ago, when I was trying to decide if I should transition, someone suggested a helpful thought experiment: would you still want these interventions if you lived alone on a desert island, with no one around to see them change your body? Like every hypothetical, this one had an agenda, which emerged from the premise that anyone who sought surgery or hormones because of their social context could not really, truly want them1. To be authentic, this life-changing desire must have a deep and essential and perhaps even genetic origin, one that has as much to do with other people as your eye color. Only someone who would choose to transition while in total exile, it followed, could even approach worthiness of such a serious act of autonomy.

Only with time and medical transition did I come to really grasp the violence of this premise2. Today, I’d wager my rent check that if you polled the 99 percent of us who don’t regret transitioning medically, there would be no uniform, “correct” answer to this question. Even my own was split: I figured I would only want to be on hormones if I had to live in the world with other people, but if I had to go to that desert island, I would be as titless as the day I was born. In this sense, I suppose, the thought experiment was elucidating, but only once I disarmed it by subverting its premise. Had I taken it as intended, I would have had to add it to the web of emotional hairline fractures caused by the mountain of “well-intentioned” advice from cis family members, doctors, and other ghouls who had convinced themselves that their desire for my death was actually a sort of neighborly practicality. (Anyone who asks or compels you not to transition is communicating their preference: that you die. Internalize this, act accordingly, and you will be free.)

Clearly, a thought experiment such as this one is not designed for nuance or a world in which change—of circumstances, needs, or desires—is not just possible, but assured. Like most of what passes for “self evident” or “commonsense,” it’s designed to torture transsexuals for admitting to the social nature of our embodiment; for our deeply human and healthy need to be seen by other people, and not just ourselves, for what we are.

Life is hard, maybe especially for other people, so how can we dare to do more than merely endure it? In her indispensable new piece, “Deconstructing Creative Angst,” Charlotte Shane writes about the guilt that many of us feel when presented with the opportunity to “indulge” in the things that align us with ourselves—our interests, our passions, our art. Perhaps you, too, have found it easier to conceive of an existence of righteous drudgery and unremitting self-denial than grant yourself permission to seek comfort, relaxation, or curiosity as well as mutuality and justice. In a world where the distribution of cruelty favors you even a little bit, Charlotte writes, “[f]orfeiting creation may, subconsciously, appeal as an alternate penance.”

She’s talking about the irrepressible urge to create that many of us feel pressured to wad up and throw away, especially at “a time like this.” If you’re an artist of any kind, I highly recommend reading her piece in full. I also strongly recommend it to anyone struggling with the choice to transition, because I still can’t find the difference between my art and my transsexualization. These acts of creation are not just the ways that I’ve stayed alive, but the reasons why I’ve hung on3. They are what give this particular life its worth. Without them, I cannot think or be; without them, I do not exist.

It’s not like I didn’t try it their way. For years I attempted to participate in my elimination, cutting away the parts of me that needed and wanted, hungered and fatigued, lusted and wished, in accordance with the desert island logic, which kept me not just from transitioning, but from indolence and play, as well as more “useful” activities, like thinking and cooperating (and now we see, don’t we, that this distinction only reinforces the notion that there is a bad way to be, a useful way to wither and die?). By refusing my very life on the basis of this specious utilitarianism, I also refused my connection with other people. As a result, I was as useless as I was miserable. It continues to fry the fuck out of me that the kinder I am to myself, permitting my body leisure as well as the disciplined play of art, the more I am able to meaningfully, tangibly help and support my community! I must again quote Charlotte at an indulgent length:

“Here’s a question for everyone who writes, paints, composes, etc., and is haunted by a sense that they’re wrong (bad, selfish, irresponsible) for doing so: if you give up your songs, your art, your poems, what will you replace them with? Where does that energy go? Is writing or art-making in the top five most frivolous things you do? If you were to make a list of all the wasteful ways you expend yourself, would imagination or journaling or rehearsal be on it? What good things happen when you stop? What good things are prevented if you persist?”

In a recent Death Panel episode, Menominee Native organizer and movement educator Kelly Hayes talked about her new book, Read This When Things Fall Apart, a collection of letters to activists and organizers on the frontlines. I’m not an organizer, but I have been organized, and I was deeply moved by Hayes’s invitation to the restorative pleasures of rest and imagination to those hard in the paint, which begins with accepting that not being everything is not the same as being nothing. “This thing about ‘enough,’” she told Beatrice Adler-Bolton, “it only matters that me and my ideas aren’t enough if I’m alone.” If you regard your own sustenance as an unforgivable indulgence, how can your opinion on the sustenance of others be any more forgiving? Without yourself, there is no “everyone.” As Charlotte writes: “You do not have to solve a problem, let alone the worst problems known to humanity, in order to create work worth sharing.”

While I haven’t yet read Hayes’s book, I look forward to doing so. Her interview got me really fired up, especially the part where she talks about the indispensability of art in sustaining movement work:

“If I didn’t, very intentionally, make space for art and for joy and for love in moments that aren’t about the horrors of this world, the parts of me that believe it doesn’t have to be that way might dry up and die. I have to nourish those parts of myself, I have to nourish my hope. And never underestimate the importance of art in doing that, by the way. Under all circumstances, under all conditions, we will always need art because it helps us remember the many versions of life that have been and could be. That we do not live in a cycle of inevitability, but in stories that can be rewritten.”

This is the part of the newsletter where I’m supposed to warn you against indulging too much. Where I acknowledge that self-care is all well and good, but that there actually is an appropriate amount of self-loathing or control or clock/pocket-watching—it’s just more moderate than what you’ve been told. But neither Charlotte nor Hayes do this. I think they both recognize that their audience’s problem has never been apathy; that traumatized, burned out, oppressed people cannot be chastised or threatened out of their immobilization. I’m not sure that anyone can. What they do offer is encouragement and clarity, premised not on our inherent need for punishment, but on a recognition of our humanity. You matter. We matter.

And if you matter, then so do your acts of creation, whether they happen on your body or elsewhere. I return, as I often do, to Maya Cade’s piece on the role of the artist in Black cinema, life, and Palestine from last year, “For All We Know and For All We Cannot Yet See.” Art can be a tool, if deployed with intention, she writes, “a testimony to the change of social order and an unbinding of the ties of colonial, capitalistic, and racist fantasies.” Of course, there is greater emotional risk in taking yourself, and your art, seriously than in succumbing to their dreams of annihilation. “If [your work is] not that important to you, how can it become important to anyone else?” wonders Charlotte. Valuing your art—and yourself—takes courage, a word that appears in Maya’s piece 10 times, one of them in this sentence: “[p]erhaps courage is the point awareness becomes movement and movement makes way for transformation.”

Your subscriptions help me pay the bills, allowing me to keep publishing work that’s mostly free for everyone, so thank you kindly for your support.

If you’d like to support me in other ways, you can like and share my posts, preorder my new book, Casanova 20: Or, Hot World, or find me on Twitter, Instagram, and Bluesky.

Since 2023, the vast majority of Gaza Strip has been bombed and destroyed, displacing around 2 million people who need shelter. The Sameer Project is raising funds for tents, cash, and other vital supplies. Screenshot your donation of any amount and I’ll send you a free month of subscriber-only DAVID content. Please share the fundraiser in your networks!

1Laying my cards on the table here: the concept of trans “social contagion” is the pathologization/criminalization of our family and community lives!

2Not to mention the threatening construction of the thought experiment itself…

3I’m reminded of Julian K. Jarboe’s viral proverb: “God blessed me by making me transsexual for the same reason he made wheat but not bread and fruit but not wine: because he wants humanity to share in the act of creation. I am only doing the Good Works here on Earth as intended!”

October 14, 2025

Autumn comfort food

The weather has finally turned. We may still see “unseasonably” warm temps yet—remember last year’s eighty-degree Halloween?—but today the conditions in New York City are appropriately dreary. Personally, I find chilly nor’easters and water-slicked rats to be cozy. Heavy rain is a rare and auspicious treat where I come from, so as long as I can get indoors when I need to, it always puts me in a good mood.

Despite the coziness, this month has been a sad one for me, so I’ve been eager to obey the primal urge hibernate. Jade and I have spent most of our time cleaning and organizing our apartment, getting our friend, Robert (who mostly lives outside), sorted with clothes for the colder weather1, and rolling joints. Last night, for the first time in weeks, we had friends over for her vegan lasagna soup, bright and basil-y with creamy tofu ricotta. Even people who can’t imagine a day without meat love Jade’s cooking.

I’ve been making a lot of soup, myself. At the beginning of the month, I woke up unaccountably exhausted after a full night of sleep, so fatigued that I was worried I’d come down with COVID (testing confirmed that I was negative). Bone-tired, I slogged through work. As soon as I could log off without getting in trouble, I forced myself to go the store, buy my ingredients, and return home to make a pot of tom kha. Slowly, I chopped and sliced and peeled, hunched over the stove like a witch with low self-esteem.

When the soup was finally ready, I sat on the living room floor, eye-level with the coffee table, and sipped it directly from the bowl, sifting the hot, spicy, citrusy broth for the aromatics I’d been too lazy to strain out. I chewed the slivers of lemongrass and the skins of shallot, enjoying the feral feeling of eating something that, while tasty enough, I would never have served to someone else. To me, this is comfort food: something you indulge in secretly rather than privately. That’s the upside of shame, you know; with the right attitude, its frisson can easily accommodate the sense of having gotten away with something, which is not quite the same thing as having been bad.

Lately, breakfasts have been my new favorite smoothie: 1 banana, 1 orange, and 4-5 dates. If you want your dates to taste good, you have to splurge on the kind that still has the pit inside. (Maybe you already knew this, but I didn’t start eating dates until I was in my thirties, so I’ve had to figure this out on my own.) Preserved without the pit, the dried date is a mere husk of its former glory, the desiccated daydream of what a real date can taste like: sweet and syrupy and rich, like chewy, slightly grainy molasses. In the aforementioned smoothie recipe, the unpitted date’s flavor and texture bind together the other fruits, bringing out the banana’s depth and the orange’s brightness. Unpitted dates have been pretty easy for me to find in Brooklyn, but recently I discovered that they sell boxes of dates-on-the-vine, which are a dollar or two more expensive but even juicier, if that was even possible. They drip like honeycomb, with an almost obscene succulence.

Now that it’s no longer summertime, eating oranges and bananas feels even stranger than it should. I know that this is cognitive dissonance, the idea that tropical fruit is more “natural” in New York City during the summer than at other times of the year. Everything feels unnatural and precarious. Though prices rise and wages stagnate, services are cut and cops multiply, for now there are still winter strawberries and plastic-packaged dragonfruit and delicately twisting soursop at the corner grocery store. And so I buy my oranges and my bananas and I combine them in my blender with the dates that came to me from Tunisia, or Morocco, or some other country that I will probably never visit.

Thank you for reading and sharing my newsletter. If you’d like to support me in other ways, you can preorder my new book—Casanova 20: Or, Hot World—out this December, or find me on Twitter, Instagram, and Bluesky.

Since 2023, the vast majority of Gaza Strip has been bombed and destroyed, displacing around 2 million people who need shelter. The Sameer Project is raising funds for tents, cash, and other vital supplies. Screenshot your donation of any amount and I’ll send you a free month of subscriber-only DAVID content. Please share the fundraiser in your networks!

1If you follow me on IG, you may remember that I recently asked for donations of clothing and other supplies on Robert’s behalf. I now have more sweaters and pants than he could wear in a year, which I will hold onto for him until he needs them. If you were one of the people who contributed to Robert’s mutual aid, thank you again ❤️

October 6, 2025

What I've been reading

I’d never heard of Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o before he died this past May (I’m a rube). Intrigued by his many reverent obituaries, I chose the Kenyan author’s A Grain of Wheat at random from the seminal works that were circulating, then ordered a copy from my best friend. Taking place in central-ish Kenya over a few days in 1963, Grain begins when a man named Mugo refuses to give the village speech for Independence Day, to the great confusion of his community, who wishes to honor the courage he displayed while held in a brutal detention camp during the rebellion against the British colonizers. Why doesn’t he want this honor? What could he be hiding?

The answer to this first of many mysteries lies at the heart of Grain, which follows Mugo, husband and wife Gikonyo and Mumbi, British collaborator Karanja, resistance hero Kihika, and other Kenyan men, women, and young people (plus one or two white colonizers) through their memories of Kenya’s Emergency and its aftermath. Like the colonial edifice it toppled, the Emergency ended worlds for the people of Kenya. Under violent occupation, the characters of Grain are forced to betray themselves and each other, mistrusting their loved ones, reporting their comrades, and choosing safety over dignity in ways big and small. In this way, the novel shows racialized class struggle taking place at the level of the individual, the family, and the village, at whose intersections child abuse, misogyny, and poverty weaken the resistance movements that lead to revolution and life beyond.

Thiong’o’s all-seeing Grain (described by other writers as “spiraling” or “a game of mirrors”) provokes an uneasy empathy for cowards and sadists—masks that all of us wear at one time or another, I think, as power permits. I don’t meant to suggest that this is the novel’s politics (its characters also exhibit legendary courage, conviction, and resilience, as well as more everyday qualities: mischief, curiosity, amorousness, pettiness, industry, good humor, etc.), only that it is willing to show us what failure—of imagination, of political will, of one person’s moral obligation to another—can look like, how it snowballs, poisons, and corrupts. Layering characters and perspectives with an awe-inspiring delicacy, Thiong’o has written a novel that is as narratively masterful as it is emotionally complex. It was his second-to-last work written in English before he switched to Gikuyu1; for this reason, as a monolingual, I treasure it all the more.

I read Grain back in June, but it’s on my mind lately because everyone keeps saying, “The world is on fire!” I see it in the comments of recorded ICE kidnappings, I hear it in casual conversations about the economy, I feel it when someone either carefully ignores or fall to pieces over the fact of a hot October day. And it isn’t just Thiong’o—all the books I’ve read lately are apocalyptic, I noticed.

Certainly I gravitate toward the subject. No one could say I picked up Lydia Kiesling’s Mobility, Sabrina Strings’ Fearing the Black Body: The Racial Origins of Fat Phobia, or Jordan Thomas’ When It All Burns: Fighting Fire in a Transformed World without knowing what I was getting into. But I think 2023 was a turning point for me, when I devoured (from between my fingers, or so it seemed) Cormac McCarthy’s unforgettable final novel/s, The Passenger and Stella Maris. Since then, ending worlds have seemed to seek me out, from William Carlos Williams’ fascinating, frustrating fantasia of genocide, In the American Grain, to Benjamin Labatut’s The Maniac, a fictionalized biography of John von Neumann whose last section dramatizes the 2016 DeepMind Challenge Match (an historic Go match between the world’s best player and a computer program), to Samantha Harvey’s Orbital, which follows six people aboard the International Space Station as they orbit Earth 16 times—that is, for a period of 24 hours.

This last was beautifully done, but as I read it, I felt a strange resentment growing inside me. In this near-plotless novel, Harvey’s crew of astro- and cosmonauts does little more than observe the world below them. They keep the lights on, as it were, running tests, exercising their muscles, and telling stories. Other than their wealth of memories and a spacewalk or two, however, life on the ship consists of the calm contemplation of a truly mesmerizing view: the Earth, Orbital’s main character. From high in the atmosphere, the reader joins them for the most engrossing geography lesson ever given, peering down to observe the globe’s oceans, mountain ranges, and superstorms as they slip by like puddles on a leisurely bike ride. Sparely beautiful, the story is absorbing, if unsatisfyingly passive at times.

It was not until the end of Orbital, with the clear foreshadowing of a specific doom, that I put my finger on my resentment. Harvey is elegizing life on earth as we know it—and the culprit, industrialization-driven climate change, couldn’t be more clear. But by situating this destiny within its universal context, a billion-year timeline of stardust and its various reconfigurations, she strips her elegy of urgency.

I can’t blame her for this. I can’t blame anyone for the way they confront the existential crisis that lies before us. But I can dislike the confrontation. The ended worlds of other authors have left me frightened or infuriated or motivated, have driven me to the depths of despair (McCarthy) and the plateaus of resignation (Thomas). This one has simply frustrated me.

Thank you for reading and sharing my newsletter. Buy my books or find me on Twitter, Instagram, and Bluesky.

Since 2023, the vast majority of Gaza Strip has been bombed and destroyed, displacing around 2 million people who need shelter. The Sameer Project is raising funds for tents, cash, and other vital supplies. Screenshot your donation of any amount and I’ll send you a free month of subscriber-only DAVID content. Please share the fundraiser in your networks!

1Ngũgĩ catalyzed the abolition of the English department at the University of Nairobi in order to focus on African languages and literature, including oral traditions.

September 29, 2025

Body scan

Hair: This morning I called in sick, deciding that I would use the day to lie in bed and finish Dorothy B. Hughes’ In a Lonely Place, which is just as riveting as Nicholas Ray’s 1950 film noir adaptation. (Fans of Tom Ripley’s many misadventures, which began with Patricia Highsmith’s The Talented Mr. Ripley in 1955, will appreciate Lonely’s con man protagonist, Dix Steele, whose powers of social parasitism are driven by perverse rage, deformed lust, and bitter class resentment). Instead, I’ve answered emails,

September 23, 2025

Come see me at Perfume

You’ll notice—as for some reason I didn’t until I was writing this post—that this reading is scheduled for October 7.

As Writers Against the War on Gaza (WAWOG) wrote in their statement of solidarity, Israel’s assault on Gaza did not begin on that day in 2023. But since then, the escalation of starvation, bombing, and immiseration has been astronomical. In response, there have been countless actions of solidarity and complicity, from BDS and PACBI, to fundraisers big and small, to larger mobilizations, like yesterday’s 24-hour general strike in Italy. Much is being done, which I don’t say to be placating, but to remind you that you and I are not alone in what’s left to do. And there’s a lot.

So while it would be nice for you to join me at Perfume, I suspect there may be better uses of your time that evening. Whatever you do, I hope you’ll consider supporting Palestinians on the ground in whatever way you can. You can start with the link below.

After 16 months of chaos, Sama'a, Baha'a, and their young daughters Julia and Talia were displaced again in mid-September. They have lost everything, over and over. You can help them cover their expenses—which include rent for their tent, water, milk, and diapers—here.

**As always, screenshot your donation of any amount and I’ll send you a FREE MONTH of subscriber-only DAVID content.**

Thank you for reading and sharing my newsletter. Buy my books or find me on Twitter, Instagram, and Bluesky.

September 15, 2025

Does pain feel good?

“Terror enlarges the object, as does joy.” — William Carlos Williams

I used to fixate on scenes for days in advance. Rather than simply not doing it and, you know, taking up tennis or knitting instead of S&M, I spent most of my waking moments just barely restraining myself from chickening out.

As afraid as I was, however, I was rarely brave enough for that kind of cowardice; I knew canceling would just prolong this horrible anticipation, and might even cause my top to suggest that our rescheduled beating be even more injurious or humiliating, something that I found very difficult to say no to. A frog eater to my core, more often than not I went through with it, though I hoped and prayed until the last possible moment that an act of god (head cold, death in the family, etc.) would make my top reschedule. And while god did come through once or twice, almost invariably the agreed-upon hour would approach to find me—flushed, sweaty, positively vibrating—packing a clean change of clothes and double-checking the address of the dungeon (punk house, condo, whatever) where my top awaited me, I imagined, in still and silent darkness, like a wooden soldier inside a cuckoo clock in the seconds before midnight finally strikes.

Davey Davis's Blog

- Davey Davis's profile

- 55 followers