Revanth Ukkalam's Blog

September 28, 2025

The Leopard of Morrison

Like a scattered blanket left uncared for during a rush hour morning, she lay resting on a colourful (let us say of a largely light citrine color with twirls, loops, and hoops of other colors spun away) colonial sofa. She was all the while guarded carefully on either side by smaller, brown leather couches and tall brown lamp shades with trapezium pleats. Wearing blue jeans and a purple crop-top, she let her legs fold enough to not fall off but also just enough so as to rest one above the other comfortably. Her arms, which pillowed her, crossed against each other, much like the crossed limbs of leopards napping on the branches of acacia trees in the much-famed photographs of the Southeastern African Savannah. Her hair, perhaps grown to right under her shoulder, blonde mostly, excepting the cinnamon roots, partially covered her face. My subject’s black leather ankle boots were left to give company only to her folded and relaxed little sack by their side.

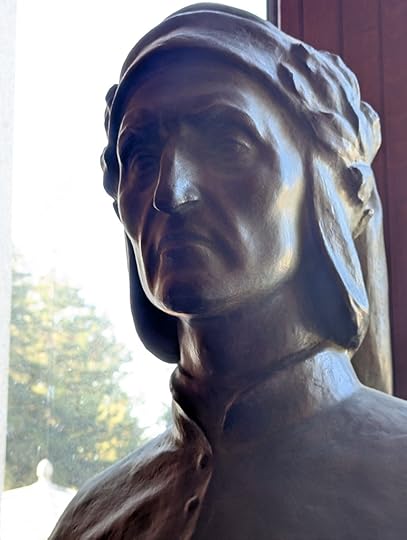

She was the heart of the hall – the library hall patronised by the Morrisons. Only underneath her sofa, there was a carpet. And the edge of the carpet was tended by an empty podium, intended perhaps for future (rather, past?) speakers. Should the library have served its duty entirely, she would meet the speaker’s eye, instantly. Even sans speakers and evening events, the mezzanine, not very high, that flew past her head, the gaze of Dante in some distance from one direction and Roman Emperor Caracalla from another all assured that she was the heart of this very room and could not be missed. Yet, she seemed to not mind and sleep away in peace.

To my eye, in her, simultaneous furnishment – her well-selected boots and her perhaps unexpected abode at a site of symmetry – and abandon converged: she seemed to know full well the attention she may draw from being in the centre of the room and the gaze of the living and the dead, long long dead, yet she seemed to not care. There was even something untame, something brave in this hour of sleep too. To resist a nap after lunch is challenging, but to resist getting up around 5 maybe deemed sloth. As much as silence comfortably hung over, crawled in, and marched about this library, the universe of the campus was far from quiet. Doe slowly was prepared in this minute, around 4:45 (let us call it dusk in the temporality of the university day, if not by the measure of the sun and its “golden hour”) to empty itself. Some returning, some issuing books, walked away, making sounds around. Yet my subject slept.

I began to suspect that there may be something more than abandon at play. One may introduce helplessness as a characteristic. It returned to me that this was one of the hottest days of the year (touching nearly a 100° F) – only I would get affected hours later. She must be bogged down entirely by the heat, I thought, that blared with little consideration, like weights on the head, fire on the skin, and fumes on the stomach. Meanwhile the warm yellow light from the lanterns in this room seemed to cushion us all. And of course, wood on all sides, in the heavens and on earth, and shelves of books in this cosmos that was the library seemed to protect us all. She was allowed, despite the grind of the end of the first third of the semester, and owing to this perfectly measured lighting, and furnishing by Oxbridgian aesthetics, to rest, rest that she much needed. That also explains why she was not alone. A few others too (some with macs that seem to fall off the light clutch of their hands), on less appealing sofas, and in less obvious and central locations, had fallen asleep and to unintended nap-monsters.

I could picture thus, that in the fifteen minutes that would follow, or perhaps in the fifteenth or so’th minute, when Morrison will shut, she will be jolted to wakefulness, made to set her feet into her boots (even if she would like to do it gently, like the rest of her fellow sleepers, she would be forced to get up quite gracelessly in that last minute), move out into the sun that was nowhere near setting (but I presume that she carried cooling shades in her sack). Perhaps finding another seat with no wooden cooling and warm light-lulling on campus, or her home, she will have to return to work. The near-hundred-degree late summer day had clearly and certainly stolen hours from her day and her study schedule. I wondered if she will panick in a few hours’ time that she had lost much of her afternoon to the leopard-nap. I imagined her cursing herself for letting the pleasant character of Morrison get to her. However, she may have also led life already at some degree of edge for any lost amount of time to shock her. She may after all with a subtle, friendly, but mostly indulgent little chiding, get on with the study that she had had planned for the day.

All of this though, is but my getting ahead of myself.

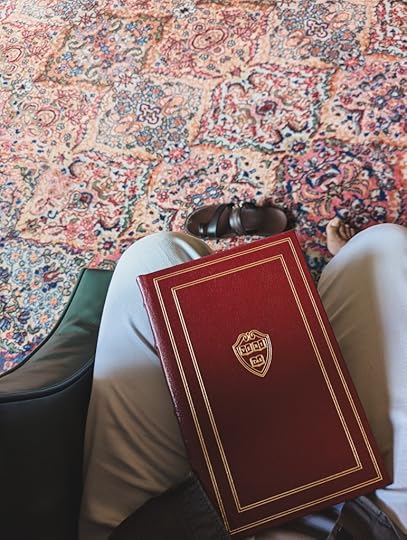

I have all along suppressed the one detail – risking falling off the sofa, an opened book, its spine facing the sky and the pages caressing her two arms, rested on the woman. As always while observing my subject, I hid the details of the book from myself. I wanted to reward myself at the end of the assignment with the title. Right before I would leave the library I stole a glance of the book from behind her sofa. It was a copy of Walden and other Writings. Indeed, there was something spectacularly satisfying about this fact. This – was “verily” how the book was meant to be read: with bouts of naps (a few drops of drool may also be spared on its pages provided it is a heavily hot afternoon). Nobody reads – I hope – Thoreau with hurry and duty, and instead with leisure. I shall take a leap and call him the Sage of Leisure.

And I also hope this was an hour of leisure for the leopard. It must be.

July 3, 2025

Heat, Heat, and Heat: Reading Tamil in the Summer

I spent a whole month of one of my favourite summers in Tamil Nadu (barring a three-day furlough to the Travancore coast) and to much my delight I spent this month thinking of Tamil culture and peculiarly for this summer, also reading Tamil in Tamil. I owe much of this summer’s pleasures to my guru, Prof. Anandakumar, Head of Tamil Department at the Gandhigram Rural Institute who taught me not only how to read the Perunkatai which I intend to study partly and somewhat peripherally in my research. I also of course owe the delights of Tamil Nadu to my kilimol̤i (parrot-speech) and kuyilkural (cuckoo-voice) girlfriend who gave me company during part of my stay in Tamil Nadu and taught me how to be in Tamil. With her I bathed in Tamil music and dressed myself with Tamil cinema (sometimes grotesquely like with Thug Life). Here I just leave of a few excerpts of memories of reading Tamil. And this blog post is a hat-tip to my spiritual preceptor, Thiru David Shulman who wrote a whole memoir of his stay in Andhra titled Spring, Heat, Rains (2008).

-0-0-

Udayana and his entourage proceed to Rācakiri (Rājagṛha)

Marutam Tinai

The toilers on lines of paddy like a crowd

Descend into a pond

From which emerges a buffalo – rushing away

Combing apart bundles of leaves hanging atop shafts of sugarcane

Kissing wood apples

Wagging its tail, it

Steps on the most precious rice

And rubs itself against a lotus guarded by the green of paddy and

on slushy waters where flies had landed,

and with it also pushes a frog to leap into murkiness.

It sluggishly hovers around stacks of hay merged with the rice

where bees buzz without break

And sails under the vast shade of the areca tree

(Perunkatai, 3.2.14-20)

-0-0-

The bliss of traveling in Tamil Nadu has been hearing a song line that goes “Jannal vecha jacket podavaa kaatru adikku”

[Stitch me a bodice with a window so the wind can strike me]

-0-0-

Udayana suffers from separation from Vācavatattai:

As the white cloud breaks its form

And hosts a flash of lightning – that

glimmers with shine and letting off heat

The hero proceeds on the path, all the while

meditating on his beloved

On a short branch of a mast-wood tree, gently waiting

for his lover, a cuckoo bird flaps his wings

till the flavour of the flower becomes his plumage

and he forsakes his own form

His rosary pea-eyed lady-love seeks him too

but cannot make out his new facelift

and yearning to mate with him she flaps her wings and he –

makes himself heard with a call of pity

Till the two are paired and at ease

The hero – alone, alone is as if pierced by a lance made of iron

— picks up his lyre and with his lotus-like palms

begins playing

(Perunkatai, 3.6.7-19)

-0-0-

It took me a visit to Srivilliputhur and sitting at a mantapam between the Vaṭapatraśāyī temple and its gopuram to realise that Āṇḍāl all along was not just a poet-saint but a patron-saint; of all of us heritage-lovers, temple-goers, and museum-visitors. In nāyakanāi ninṟa, she speaks to a guard (kāppān-ae) of the koil to open the door, just as we all make pleas to the temple management, the priest, the ASI security guard, the museum curator. Each time, we appeal to their position (koḍi tonṟum toraṇam vāyil kappānae: guard below the gate flanked by tall flags) and ask them to open the doors (tāl tiravāy), or keep the doors opened longer, let us have a peek at a hidden shed of sculptures, and most importantly – take pictures! And each time we must elevate the value of what they have power over (maṇi kadavam – the door is no less than studded with precious jewels). And why should they open the doors? Look at us. So poor and little – emaciated, having come from so far just to see this (āyar ciṛu-miyarōmukku- us, the little cowherder girls). But no, no we are no ordinary people, as little as we may be. We are consumed by this place that we have come to – we are somehow very ‘pure!’ (tūyōmāy vandōm). The place speaks to us: we have sometime back made a covenant with the place and come with expectations. Just like Maṇivaṇṇa promised Āṇḍāl that he would give the girls drums to play (aṛai paṛai vāy nērndān) as he would sing (pāḍuvān) for them. The moment of love between the place and us should make the bureaucrat, this kāppān make an exception. We deserve it. Can he not listen to love? — We ask. Just like Āṇḍāl did!

-0-0-

“Ātan“, one of the oldest surviving text fragments in South Asia. Keezhadi, 5th century BCE?

“Ātan“, one of the oldest surviving text fragments in South Asia. Keezhadi, 5th century BCE?-0-0-

June 2, 2025

Solapur and my first Sanskrit Poem

Like a roadrunner, I tend to ravage the dusty landscape of Deccan every week spent at home in Hyderabad and since I moved to the US, this meant doing so with much vigour and careless passion. And most recently I found myself perched inside the Solapur fort, situated only some three hundred kilometres from my city, and a site of severe political contestation in the medieval centuries: between the Yadavas, the Tughlaqs, the Sultanates of Bahmani, Adil Shahi, and Qutb Shahi, and the rulers of Vijayanagara and finally the Marathas. Richard Eaton and Philip Wagoner feature this “contested site” in their book – one of my favourites – Power, Memory, and Architecture. Due to the silence on the temple and the mosque in epigraphy and literature, they cannot do much but conjecture perhaps that a resistance by a monarch may have pushed perhaps Malik Kafur in the early decades of the 14th century to transform a Yadava-era (13th century?) schist temple into a mosque that neighbours it. They identify that only some fifteen pillars’ shorter shafts are missing in the desecrated temple, and in fact precisely these shafts become pillars to the mosque that oversees the temple from a slightly higher plane. There is other borrowing visible too: not least the rather bare tiles with foliated rhombuses.

However, seated in the pit-like habitat of the temple, very austere for the unashamed indulgence of the Deccani-Karnataka idiom, I was moved once again as I always tend to be with the glamour of the Vesara. Celebrated for its sharp edges, as if a shining star when viewed from the above, the temple of this type bears miniatures of its towers often guarded by pouncing but truly dancing Yalis. And picturing this format as a goddess I composed the following verse in the Shardula Vikridita metre – the metre of the dancing tigers: one that is said to be appropriate in textbooks, to talk of warriors and lovers in sport, but seen often in the talk of ornamentation of the goddess of learning.

आकाशाम्बुधिमन्थने सुचरितम् यस्याः समुद्गच्छति

या तारा तद्भूमिस्पर्शनटने वात्स्यायनम् चुम्बति

यस्यां कृष्णशिलापि आत्मरुचिना शार्दूलविक्रीडिता

ताम् देवीम् नमनम् करोमि विधिना कर्णाटपर्याटने

ākāśāmbudhimanthane sucaritam yasyāḥ samudgacchati

yā tārā tadbhūmisparśanaṭane vātsyāyanam cumbati

yasyām kṛṣṇaśilāpi ātmarucinā śārdūlavikrīḍitā

tām devīm namanam karomi vidhinā karṇāṭaparyāṭane

By near-covenant I offer my prayers to that goddess

In every outing in the Karnata

– whose saga curdles in the churn of space-sea

that star which kisses Vātsyāyana in her earth-touching-dance,

and in whom even the mere black stone without parting from its own ways,

bears the dance of the tigers

March 27, 2025

Grimness and Protest: Thoughts on Ousmane Sembene’s Camp de Thiaroye

A lean black man with a triangular chin, dull and quite off-key from the men that surround him, slowly descends upon a spiked metal fence. He grasps the fence and looks beyond it grimly. The universe is still – quivering, yet still. The grimness of the gaze and the firmness of his clasping is interrupted by a merry friend who pulls his hand away and dusts it with the sand they stand upon. He reminds him: “we are on the soil of Africa now!” The transfixed universe is back in movement and conscious only of its own movement. The moment is gone. Or so it appears. Really the moment’s arc stretches through the film and Sembene affirms that not just triangle-chinned Sidiki Bakaba but all humans had ought to be grim all along. Notwithstanding the sentimentality of the African soil, the reality of the fence around the Africans had a more sonorous ring in the history of the soil’s people. And the Camp we are now at and the corpses whose intestines it saw gleefully were testimony.

Ousmane Sembene and Thierno Faty Sow’s 1988 joint-directorial, Camp de Thiaroye, long banned in France and censored at its home, Senegal, was self-admittedly Sembene’s most nihilistic work of art. In this film, Sembene, known for his unflinching expose of the hypocrisy of imperialism – that there could possibly be a universal citizenship fostered by Empire and the march of God that is the just law – raises a mirror before the unshakable racism that French rule upon the Dark Continent is premised upon and indicts that colonial rule had been fully eroded, if it ever possessed that is, of all ethics. The inspiration for this film is the disturbing and depraved Thiaroye massacre of December 1944; Black African soldiers who had fought in the Battle of France in 1940 against the Axis forces and held as PoWs were liberated by the US in 1944 following the Normandy landings – and subsequently kept a “transitory” (read: purgatorial) camp off the Atlantic coast, outside Dakar in Senegal. When soldiers before being “released” into their villages, demanded fair treatment, edible food, and decent pay and compensation for their war services, a compromise was arrived at but the Army doubled crossed them and under the cloister of the night, massacred – according to the veterans – over three hundred ex-servicemen.

While, arguably, history does Sembene’s bidding for him, for betrayal and blood were already in the story, the film’s beauty is thicker than just the reflection upon the massacre. It lay in the thorough autopsy (why though? While colonialism is still all around us) of the design of the colonial subject. Colonialism is never over, the film shows us. It is complete, all-pervading, and substantial but not finished. Colour of the skin is always given precedence. In what forms a good leg of the film, a well-read and cultured Sergeant Diatta visits Dakar (an African city where most spaces are reserved for Whites alone) to grab a drink but is on the way bullied by American soldiers, but a Black soldier is pushed to be the brutal one. Nation trumps colour for the Black. But following Sergeant’s hospitalisation, when the Black soldiers in our Camp retaliate by taking a White American soldier hostage, the French army command is quick to swoop down into action (i.e. demand that the hostage be treated with kindness and released) and defuse the situation. They pay no heed to Nation. Are they (the North Atlantics) not all part of the ethical universal (White) commonwealth? The message though is clear: Blacks ought to be tied to nation but the White empire, need not.

And imperial racism is so full that the allotment of meat is different for the different cadres of soldiers in the camp: White Frenchmen get a can, “natives” – whatever that means – get half a can, and Black Africans only get mashed potatoes and gruel for meals. A soldier called typically in this film by the country he belongs to – each is referred to by their nation alone to comedic effect: the colonial (and post-) order is comical indeed – questions: are the sizes of the bullets that enter the body of each different?

While in a “mainstream” film, this could be a “high” moment, this provocation actually leaves us to look at history. And yes, while the bullets shooting into each body is race-agnostic, the bodies themselves were very much racial and racialised, so much that the French justification for breaking the taboo of not deploying colonised bodies Black and Brown in conflicts between European states (the taboo stemmed from the fear of the psychological and political ramifications of Asian, African, and other indigenous men being allowed to kill White Europeans, and worse, on European soil) was that simply the Black body was more resilient to wounds. Watching this film, I was made to think of David Olusoga’s masterful work The World’s War where he argues that in the recruitment of the colonised people, truly the First World War was indeed the real first global conflict. Olusoga dedicates an entire chapter to the La Force Noire, a 1914 pamphlet by Charles Mangin, a French strategist. In the book he declared:

The black troops… have precisely those qualities that are demanded in the long struggles in modern war: rusticity, endurance, tenacity, the instinct for combat, the absence of nervousness, and an incomparable power of shock. Their arrival on the battlefield would have a considerable moral effect on the adversary.

It comes then to us of no surprise that Mangin had even earned his credibility to propose French military strategy from having led in the disastrous Foshoda Campaign, (a race between the Brits and French in the 1890s to capture the city of Foshoda and become the first to touch with their African empires sea to sea) the Tirailleurs Senegalais, the very army that is the subject of our film. It is hence the above reassurance that the empire(s) gives itself that allows Maori, Punjabis, Gurkhas, Arabs, Senegalese, and Zulus to all fight in Europe (including, as Olusoga shows, become lab rats to the most terrifying military experiments like the first use of artillery and tear gas in the Battle of Ypres in 1915).

Racism while being prevalent had to substantially give way to the martial spirit in war (for Indians fighting in Europe, this meant also relaxing caste rules before they are reasserted after 1918) and it seems for too many people, the burning smoke of illusion had rested too long in the air. A curious way to frame this film is to see it as the story of the necessary disillusionment thereafter. Even Whites had apparently all along been part of this illusion and disorientation. When the French Army black soldiers take the White American hostage, a White French Captain sympathises with the hostage and remarks: “how can the White be expected to sleep in the same room as the Blacks?” An apparently “good” General questions: what about when the war was waging? The captain is quick: “That is different.” Everyone is disillusioned at a different pace. But the most powerful portrayal of the simmering agony of disillusionment and reorientation is in the theatre around the soldiers’ uniforms. After the soldiers had been freed from German prisons in France by the American armies, they had been given American uniforms to wear till they returned home and this meant not only the light khakhi colour of the shirts and trousers but all the regalia that followed American military line of command and the hierarchy that the World War brought in (in fact it is the shared uniform of the Sergeant and parasitic American troops in Senegal that frustrates the latter soldiers till they beat up the Sergeant). Wearing these uniforms had made the soldiers at the Camp feel not only part of the French Army, but also equal parts of the French Empire (why would they even feel comfortable to spell out their distaste for the food?), Alliance, and the Global Commonwealth for the Good. Placed above his fellow Blacks, he is sold on the fable of meritocracy. In a long-drawn act in the film, the soldiers are all made to return their khakhi uniforms and wear the colonial army clothes: where each colony and each community is neatly placed in a sartorial cartouche. Thin white half sleeved shirt and shorts, and a red Fez for the Tirailleurs Senegalais. The soldiers all return to their wooden cottages and assure each other fierily that all is well: but realise of course that they had been told that they were citizens of empire only for the war. Now they must learn to be subjects again. The biggest shock comes to the Sergeant who had bought the nice and sweet myth of meritocracy. As they receive their colonial uniforms, he notices that his regalia are all gone. He cries: “you gave me the hat for rank and file.” In silence, Sembene responds: no you received the hat for the colonial subject.

The Sergeant who by living in the metropole, marrying a Frenchwoman, and giving birth to a mixed race child had turned optimistic about empire learns over the course of the film that even the “good ones” are not really that good. Sembene anyways had always had a particular disdain for the metropolitan and colonised intellectual: in Moolade, the France-returned would-be-groom is the least virile and activist, much less so than the fiery female protagonist, and in Mandabi, the educated lawyer is an outright cheat. And this time, Diatta becomes an opportunity for the filmmaker to dress down the perverse forms that colonial prejudice can take. While the obviously racist generals all think that the Blacks had best be kept away, fed bad food, and thrown back into the villages of the colony to be suppressed by guns and taxes, the “good” ones believe that there was hope for them after all. Except that they should extinguish the blackness in them. They must dissolve their identities, merge with the empire, and be secularised. They must become characters in the Liberal Wet Dream, if you will. As Bruno Bauer asks of the Jews at the height of the Jewish question. Or as Ataturk asks of the Turks. And Hamid Dalwai asks of Indian Muslims. So once again to be Black was a sin. This “good” general does not even call Diatta by his name. He refers to him by his French, no, Parisian name “Aloyse”. When “Aloyse” raises the problem of colonialism and shares how his own parents were massacred along with his whole village while he was away fighting in Europe, this “good” general brushes away: “that was the Vichy period”. They were the Nazis.

In this film that too – the Nazi – is reinvented. Sembene goes so far in his attack on colonialism, as to not only compare it to Nazism, but even make his characters ponder if Hitler’s Germany was even that much worse. This may be as trivial as the claim that the kartoffel in the German prison being better than the meals in this camp. More seriously, the “good” general’s invocation of Vichy France elicits a reaction squarely comparing massacres in Europe by the Nazis with those by the French in Africa. The general is of course astounded. There could not be a greater heresy. Yes, indeed how could one compare colonisation of Africa with the colonisation of Europe. The White Continent could only colonise, not be the object of it. The film in subtler ways too walks the risky road of invoking Nazi Germany: the triangle-chinned Sidiki Bakaba, a deranged soldier (he enacts the trope of the wise madman in this film) wears throughout the film a German helmet, presumably one he picked from a dead soldier on a European battlefield. At every encounter between the generals and soldiers in the camp he appears with this helmet – his greatest form of resistance. The German Eagle staring at the outrageous generals. Exposing their racism. And of course the generals are no passive watchers. As the camp inches closer to mutiny mode, they first dismiss and then castigate the Camp as a front and arm of German propaganda and covert action. However calling the Black soldiers “German”-esque, now that the war is almost over, is only the weaker straw. We see a glimpse of the curse that shall take over soon in NATO’s World Order: “You Communist!”

That imperialism had not changed one bit is revealed bit by bit. But turns full frontal when the army decides to give only 500 CFAs (Central African Franc – this bit seems to have been a liberty taken by the writers of the film; the CFA was instituted in 1945 after the war was over to mitigate the effect of the devaluing of the Franc – that was forced upon France by the US and the Allies – on the colonies) for 1500 Francs that they had been given, for temporary usage in Europe. White Europeans, peninsulares one may say, functioned in Senegalese society with a different exchange rate. And it took only a mutiny – wearing Nazi helmets, getting their own meat (cutting it in a halal way too), capturing the watch towers and all – to make their voice heard. But it is most resounding when they take a senior general hostage, the Black sergeant party to this all. In a specially poignant image, when the captain is forced to sit down and look at the black infantry around, we wonder if this was how all mutinies felt: Haiti in 1790s, India’s Rebellion in 1857-8, and the Algerian War of Independence in the 50s.

Just as we are about to rejoice at the sound of resistance, Sembene reminds us that only nihilism had been warranted ever. And after much celebration and after silence falls upon the relaxed African soldiers, tanks roll in, like the ones that are now liberating Europe from the Axis armies. And as blood flies up and bodies fall flat, the triangle-chinned madman watches with horror. All along, he had been the wise one. Staring the fence with grimness, wearing the German helmet, and watching the tanks roll in with horror.

February 10, 2025

Meeting the Russians of San Francisco

Something named ‘Museum of Russian Culture’ should not require the archaeologising of a city. Like a hundred dollar bill on a dry sidewalk, it should be palpable, available – and much sought-after. The disappointment with the couched-ness of this museum’s soul lay in my flirtations with Russia. Some years ago: through War and Peace, Tchaikovsky, Crime and Punishment and histories of the nation. In particular, for all my philistine and rash indictments of the horrors of Stalinism and the iron claws upon the nations of the Warsaw Pact, the adolescent excitement for the colour red, the yellow stars, and socialist realism is alive. I stand hence infatuated by the Bolsheviks. To come around this stance of a sober disavowal of the Soviet Union and simultaneous infatuation with the Socialist worldsphere, I recently even manufactured the Drake-meme approving the Union’s memorabilia sprinkled in India but shunning the lead-dark weight of the USSR.

Indeed the Museum called me – from its quiet street around only a mile from the Presidio Park of San Francisco, and from its home, the Russian Cultural Centre. From days ahead I sat on the sorrows of the glum Berkeleyan skies with the fizzy excitement for this visit.

At the said silent street, an ornate façade that smells like enlightened despotism. A doorbell. Carpetted floors. Hallway filled with portraits of Russians – Californian and present-day that is, – celebrating their faraway home: with dances and cakes. Film posters. A large large elevator. Soon enough – I only wished sooner during my stay near San Francisco – the museum was here. On the third floor that marks itself apart with photographs of early 20th century Russian generals, scientists, and bureaucrats. Finally, Russians themselves on their seats. Listening to Russian! But also in Russian?

I looked around myself. Far from my imagination – better to say desire – , there was not a dash of red. Forget photographs of Lenin and translations of Marx, illustrations abounded around me of Napoleon, of trails of soldiers fighting France in 1812 (which is a particularly ruminated year and one cherished with smacking lips and gulping throats in Russia for the Battle of Borodino – a Battle that was no side’s tactical victory but proved fatal to Napoleon’s invasion of Russia and War in Europe at large) and song books on the defeat delivered to France in the Napoleonic Wars. A photograph of the Cathedral of Vasili here. A lithograph print from Germany of a view of the Kremlin from the Moscow River there, the Annunciation Cathedral and all. A sketch of the last tsar, Nicholas II. Better still, paper labels marked a few of these artefacts – sometimes in English but always definitely in Russian. But I did not take long to learn that the museum spoke more than Russian, it spoke nostalgia. A nostalgia that skipped decades and gave a longing, crispy, sepia-tinted, and often-embroidered kiss to the monarchical (they might say classical?) past. A kiss to the vanquished Romanovs.

Unsettled by this untimely romance for kings (and some queens), I walked around the gallery plastered by endless spoken Russian. Owed maybe partially to Telugu poet Mahakavi Sri Sri’s “Garjincu Raṣiyā”, a good part to the frenzy with which Gowtham Ghose’s Maa Bhoomi speaks of the Revolution, and surely to the fanfare that Dev Anand, the album of Mughal-e-Azam, and Awara enjoyed in the Union, Russian-speakers appealed to me always with a familial tone. As if walking through ‘my’ people, I kept gazing. At a shelf that was expressly in memoriam to the last Tsar, I shuddered. Tapestries that remembered the 1896 ascension of Nicholas stood out – along with photographs (that pretend to be neutral and apolitical – one need not even read Sontag to realise the falsity of such a belief) that lament the brutal and bloody killing of the Romanov family in July 1918. A volume of a 1901 French imperial magazine issued on the occasion of a grand party celebrating a then-eight-year-old alliance between the two nations (indeed Napoleon had long long paused, and Bismarck was the new man in town to put check to!) was framed. From the same year, a coin featuring once again, Nicholas II commemorating Russia’s first cast-iron, smelted two hundred years before that – with Peter the Great at the helm (the grandfather faces the young monarch in this coin, not knowing of course that he shall be the last one).

The wound of having to witness the monarchy here is gently bandaged in this hall with reminders of the ‘enlightened’ design of Russian tyranny. A recent edition of Pushkin on a table. Behind a glass there was a thick hardbound book with a green cover and presumably rusty paper – perhaps to me, the most exciting find this gallery, the registry of the 1912 (the fourth) Duma, the ‘parliament’ of Russia (never mind that more than half the convention came this time from Nobility and Tsar Nicholas pushed that the Duma be reduced to be a mere consultative body). Elsewhere a large, beautifully embroidered commemorative volume for the 50th anniversary of the abolition of Serfdom in Russia under Tsar Alexander II (never mind that a few years before the abolition in 1861, more than one-third of Russian population slaved as landless serfs who were to labour under landlords, nearly 20% of whom “owned” more than 100 serfs!). Nothing tastes sweeter to oneself than self-congratulations one ‘conquering’ one’s own vices.

As I anthropologised around, a responsible club-member of this Society hastened to me and kindly requested me to enjoy food and champagne. Including blocks of walnut cake that she had baked and soviet (finally!) chocolates. I picked the cake and the chocolates and decided to be what she specifically asked me to be – not shy. From skirting around the edges to look at the artefacts, I began not diving but softly wading into the Russians.

I began conversing with a box-faced man with a Central Asian rich-blue tubeteika reminiscent of the domes of Khiva. Denis introduced himself as a Khazak, a laser physicist, and an engineer living to the south of San Francisco. He was today here on one of his yearly drives up to the Russian Centre. He corrects himself – he is Russian, but from Kazakhstan. I ask: are there many of you here? Does he have many Kazakh friends in America? He keeps to himself, he says. I trust you, I thought. Without much pretense I ask – the absence of Soviet artefacts is interesting, right? He goes for a save, pointing to a model of a helicopter behind me. There are a few photographs of Sikorsky, the inventor of the helicopter (whatever ‘invention’ even means). And he was right. Igor, along with his wife, stayed perched upon a grey table, and stared sternly with his tight moustache firmly holding his stiff lips. Following his invention of a military aircraft, the VS-300 in 1939, America set out on the first mass manufacture of helicopters in 1942 apparently.

Some others whose company I kept that afternoon placed themselves in the curatorial universe of this museum. The baker of the cake rushed me to a display of photographs from a college that her father went to and warned – he is not in this collection, but this is my connection to this museum. Another red shirted old gentleman, only too alike to Colonel Sanders, points to a frilled frock and tells me – my wife used to own a frock like this. As I look deeply into the “womanly” artefacts, he asks me: Do you read Russian? “No” I say. “You?” “My wife is Russian.” “And you?” “Peter.” “The Great?” I joke. He giggles and says: I once sat on his chair and proceeds to recollect that a touch of royalty stuck to him on Tsar Peter’s chair in Moscow, from the hall that he abandoned to found his new capital St Petersburg in the West. Granted that artefacts of immigrants here all dated to before the revolution, I asked if his wife was from a noble family. She arrived in the US in 1917 but he tells me that she was a “common person”.

These Russians (almost) were delightful! – I thought. I then met Mercedes – of course she proposed the car company as a mnemonic device. When I inquired about her family’s arrival, she reveals that they had had many stops: after the war, in 1945 first in China (my mind’s eye swiftly turned around to behind my head to wink at the pendant featuring Xu Jincheng, a Qing noble who had been an envoy to Russia), then in Philippines, finally to Los Angeles. She smiles at the name of LA. “There were a lot of Russians there” – dropping a few more “lots” for emphasis afterwards. “Many Russians were in Hollywood too! My father was a Cossack” (Ah yes, a sociological facet for a sociology junkie inside me – the Cossacks were a semi-nomadic largely militarised loosely and widely distributed mostly-Slavic ethnicity that the Russian empire relied on for its defence and maintenance) “And cossacks played Indians in Westerns.” (The overlaps between the Cossack economy and the life of the American Indian who had to be tamed shone prominently to me) Just in case I had not caught the picture, she clarifies “the enemies of Americans were to be played by Russians.” I slide in: “I am the other kind of Indian” and ask “do you speak Russian?” Regretfully she shares that she speaks five languages but not Russian and proudly proclaims that her father used to speak nine. When I remark that the world was monolingual, she beamed: “It still is! It’s just America that thinks it isn’t. And look now they are even deporting people.” We grimace together.

It turned out that my Khiva-reminding Kazakh-Russian friend had very sweetly ushered a proud volunteer of this Centre to speak to me about the selective curation of this museum. Viktor introduces himself. Thick Russian accent – first generation immigrant – electronics engineer. Somewhat dismissively initially, he said: “It is obvious, isn’t it? This museum was made with the artefacts brought by immigrants. And so many escaped around 1917. The collections mostly belong to before that. Remember, we were with great hopes for the Revolution. We cheered for it – but the first thing they did was make Russia internationalist. They clamped down on Russian culture. We could not be Russian at all. A quest began to find a place to preserve Russian culture. First, a House was located in Prague. The museum there invited the USSR to handle it – but they ruined it there as well, so we wanted to take Russia as far away as we can from Russia so here we are in San Francisco.” He joyously speaks merry of the collection around him. He turns to the gowns and says with a “shamelessness” that is, but an ornament to all mankind, I ridiculed when the women wanted to bring in their attires and curate them, but today they are the most beloved artefacts in this museum! Through his disparagements of the Soviet Union, there was also nostalgia. Rather, a severe dislike for the current republic. With rancidity, he shared that following Yeltsin’s shock therapy, Russian industry – upon which he had sat during the Communist years – has been virally attacked, and eaten up. Unequivocally, he said, there was dignity in the past era. In 1997 – he had his own personal tragedy in this new world of kleptomania. When he had gone away, his house been broken into, his most valuable objects destroyed or stolen, particularly his computer. And only minutes later, his friend from America – as if a pronouncement from another world – called him over. And he sought his new home here, he said.

This new home that was not even like his old home, but one that was even older. One where eagles flew on flags, generals wore not caps but helmets and even crowns, and kings marked the badges of honour given off to soldiers. For all the apparent oblivion that emigres seek with the “revolutionary” past, I still wish a photo of Khruschev would have done good, and a poster of Lenin. Why when there could be a French map of Russian troops in Morocco from World War II and memorial paintings of churches from the 50s could there also not be, as I started this essay, a dash of red?

December 31, 2024

Where are India’s women tourist guides? – Notes from an Andean Village

Even though I have said the name some dozen times each day for the last three days, ‘Ollantaytambo’ refuses to stick on my tongue. It is known as the interim capital and the bastion of Incan rebellion in the 1540s by the successor (but unrecognised by the Spanish) to the last ruler Atahuallpa, Manco Inca; but to most tourists to Peru as the city of two luxurious trains and perhaps some hundred minibuses and collectivos (these seldom luxurious). It is in short, the gateway to Machu Picchu. And therefore an inescapable hamlet guarded by three clusters of hills of the Andes and a settlement given eternal air conditioning by valleys that these hills form. Despite having read about Manco Inca’s crushed rebellion (before he finally he shifts his retinue further north into the legendary and now terribly ruined capital at Vilcabamba where the Inca empire and three more kings would precariously flourish for a few decades) and hence this name many times in Kim Macquarrie’s Last Days of the Incas, I carried it only with much difficulty. And with that persistent difficulty I boarded the premium Inca Rail from Aguas Calientes at the foot of Machu Picchu and arrived at Ollantaytambo.

Only an hour before its temples and key sites would shut, I arrived at the archaeological complex of the fortification and too late to buy a ticket. With compassion that I have now come to regard as characteristic of the Peruvian tourism and hospitality sector, the ticket collector asked if I would be able to make it tomorrow. No, I have a flight I say. Visibly the officials – perhaps with empathy for the colour of my skin that is akin to theirs but also melanin that is clearly from the exotic exotic India – wished that I see their village and this fort today itself. A middle-aged tourist guide invented an apaddharma; a concept (one may call it jugadu too) that is essential to the survival of Indian society. Now I learned that the Third World was uniformly freed from the shackles of uniformity. Sixty soles shy of the actual ticket price, I was asked to make an offering of a mere ten soles in a small cup that said “tip” placed before a half-life-size manger with baby Jesus, the sacred family, and adoring shepherds. The guide said: instead of seventy for the ticket, why don’t you pay me fifty for a tour? And inclusive of the tip you will still have paid less than the ticket. I resist guides, but relish conversations – so maybe this was the Lord of Huanca’s sign for me to indulge.

I think I was drawn by the guide Yony’s charge over the site. Like the watchtowers she would introduce in her thick Quechua-Spanish accent. Like the force of the Incan rulers down from Pachacutec (who while being always called the 9th ruler is the near-founder of the Inca ‘empire’ emanating from Cusco, the navel of the earth in Inca mythology) in taming horseless and elephantless labourers to shape the adjacent into a quarry and carry large blocks of stone down the large ramp. And like the spirit of the Inca civilisation as it persists against the odds of the mountainous earth it is placed in.

We walked up the stairs of the fort as they ran over levels of the terrace farm where potatoes used to be planted. Yony made me face granaries perched on a hill before us. I try to raise the problem of meat-preservation. She stumps me: we had dried salted meat she says. Charqi – stumps me further – was the etymological and ‘actual’ root of the legendary American “Jerky”. ‘Men’ love seeing profiles of heroes and gods on hills. That is the god over even our sun and earth gods; that is Wiracochan she says. Is that also not Pachacuti’s father? – I ask. Once again she cuts my smart aleck. “That was Viracocha. This is Wiracochan.” She shows more faraway terrace farms and tells me about potato farming. I try to remind her, as if she had forgotten a crop – what about corn? She raises her arm, points to a particular storey in the farm and says: those are corn. And what more, she pulls out her photo album and drops a page with different varieties of Andean corn; pointing to one of them, she says: they planted this! Elsewhere we look at the Sun Temple, perhaps the most elaborate among those that survive in Inca cities, not least because of the living roof. She points to projections and tells me this were perhaps remnants of pumas that would have decorated this temple. I continue to be critical. How do we know? – I ask. Her ready photo album contains a Spanish illustration of the pumas before they were shattered by conquistadores. It is time for me to pay my due. We chat about the favourite element of Incan heritage in these surviving cities – the jigsaw of smoothly polished stones that make these monuments. I remember the photo of corn that she showed. I yell – hey could the shape of these stones have been inspired from the piling up of corn grains in a corn shaft? She smiles and says: Incas were inspired from nature.

As we reach the peak, we look at the village in a distance. She directs me to look at the houses that continue to have Incan walls and roofs. She tells me that many of their houses still stand on foundations lain in the 15th and 16th centuries. We call those houses ‘Cusco Community’ because they are the original inhabitants that continue to live. And we still practice the Incan religion. We all before drinking any beverage, sprinkle a few drops on the earth for our Mother Goddess Pachamama. I: Even to this day? She: Even today! There was in all this longing and nostalgic reaching out to heritage not pride, but a desire for belonging. She sought the hands of the fallen kings not for their military prowess or the assurance that they could provide to living Quechuan ethnicity, but for the affection that the company of the past could provide. There was a moving humanity in her work as a tourist guide.

I broach the subject of religion more. She is Catholic of course. She says – if I were to get married it might be in a church. But we occasionally practice Christianity. We are pushed by state. We need Baptism certificates to go to convents. And our marriages need certification from the church. And we live on Spaniard tradition. A hybrid – I ask? She nods in agreement.

But discomfort stirs me. After a few moments of silence, I ask her, tiptoeing. Records show many instances of human sacrifices. To the very gods you are talking about. With so much love you talk of these gods, and those rulers and societies that worshipped them. Do you not feel uneasy about the killing of humans that was part of the faith that you want to inherit? She admits immediately, chuckling – yes there were! Again and again, she says we do not do them anymore. With no apology, and with utmost dignity she clips: they had these beliefs about returning to the earth. In fact you know two Incan daughters were found still alive in the snowy mountain – where they had been abandoned for sacrifice. We find these rituals odd, but we have left them far behind. I too assure my position: the past is always the past and is to be left behind. But she needs no assurance from me, for she had had nothing to be shy of. She informs: why even recently, when a bunch of men found gold, one man went missing. And some other time, a pregnant woman lost her weight but there was no child with her. I think I know what happened to the missing man, former friend of the suddenly rich. And to the un-pregnant woman’s missing child. As I heard, I wondered when we might find such dignity in discourse that surrounds us. Where the strength of faith is proven by lack of doubt and reason. Where attachment to identity thrives merely on jingoism. And where life is lived purely vicariously.

I remembered about her not being married so could not help but ask – are women around you not forced to get married? When are they expected to have children? And what is the position of their employment? She turned to the story of her grandmother, who when she was 14 was coveted by her 19 year old grandfather was instantly married off with little consideration of her interest. She said about her mother: there was not much love between them. To me, a customer of her guiding, she said: they lived because they were used to each other. I used to tell as a child – why didn’t you get divorced from father when you did not love each other? I admitted that being so candid about the institution of marriage and female agency was alien to my family, society, and the broad culture that I had come from. Finally I aired: I think I began asking you about your personal life because you may well have been the first woman tourist guide I have met. She gaped.

Things began to fall in place for me. I heard for the first time, a guide at a monument talk about farming, about rituals of eating and cooking, about architectural achievements from the position of labour, about child-rearing, about the girl child of civilisation. I heard also for the first time a guide make the story of the place, a narrative of themselves. There was for the first time dignity written into the saga of justice, and thoughtfulness in a tale of celebration. Perhaps this is what an emotive register, a “feminine” register feels like.

Where are India’s women tourist guides?

The Village of Ollantaytambo scene from the fort

The Village of Ollantaytambo scene from the fort The profile of Wiracochan and the granaries

The profile of Wiracochan and the granaries  Terrace-farming at Ollantaytambo

Terrace-farming at Ollantaytambo

“Jugaadu manger”

“Jugaadu manger”

December 28, 2024

Weariness in Cusco, the City of the Inca

Pachacuti is surrounded on all sides by Spanish Baroque churches that were built on the site of temples that he and his forefathers worshipped at, and where he relied on heavy lobbying of and by chiefs to ensure that he was king. Just like all those that preceded him had done. His arm faces the hills behind the Cusco Cathedral, the oldest church in Peru, and to the most precious sun-temples of his time, built with large blocks of stone, locking into each other like the cells of a honeycomb do. Indeed, the Incas seem to have been the lords of gold. In a peculiar way the Plaza de Armas when I sit alone, rare as it is today, seems to emulate the Inca reputation. Sky, earth, and air explodes around me in gold, lit by yellow lighting hanging into high-end boutiques, cafes, and souvenir stores desperately seeking foreign exchange. The Lord of Tawantinsuyu and the God of Sun, Inti seems to have desired for the horizons of bliss.

I had little wanted to sit at the plaza. As I descended from the hill I hurried myself to recline in my hostel and bathe in narcissism over the wonderful photos I had clicked all day and share pictures of the glistening chapels in the plaza studded with canvases of “angels” with raised swords, the chequer of brown and green from the verdant Andes and sloping roofs of Cusco, and paintings water life in Nasca Culture Pottery to my art history, anthropology, and travel connoisseur-friends and lovers. Yet today having walked steep paved roads and Incan steps on a city already 3 km above sea level, I faced not altitude sickness like all run-off-the-mill travel websites had warned (or maybe it is that) but an exhaustion that is new to me. Every step seemed to let a fairy rise from my head. My spirit was frozen in a Dionysian-Apollonian struggle over desire for a chaotic bliss that is apparently felt in pain, and the more rational choice of returning home. I simply knew not myself. Just as weariness wore me down entirely, fairies flew out, and my spirit waged a battle, the city of gold shone with light under the command of the Sapa Inca.

I sought the square – for the moment I sat down my feet collapsed into the rock-solid earth like it were quicksand. And the earth reflected off the light of gold. Gold, carrying the squeak of the sneakers. Gold merging with the light of flash from phone cameras of countless families. Occasionally the gold coloured the paws of excited but slippery dogs. There were few others too alone but mostly glued to their phones. The large plastic bag filled with toy alpacas that I bought for the children of my family calls. I ignore. Like everyone else my body’s instinct on seeing beauty is to hold the camera that I think about so much. But that too gives up. The camera knows that it is not fit for Cusco.

This realisation I owe, one – of course to tiredness. It is an essential state. It slows you enough to make you drink from time. Finally maybe a little can be attributed to the hand of the Inca ruler.

September 19, 2024

Use and Abuse of Dravidianism

One year ago a dear friend of mine sent me an interview that lawyer and author J Sai Deepak for the ANI, which he gave in response to the controversial (“inflammatory”) footnotes by Udayanidhi Stalin on “Sanathanam”. Very politely he asked my views on the subject. I replied with a long-form reaction to him on Whatsapp. Recently another friend on reading this encouraged me to publish this. Here follows my essay on Dravidianism.

I agree with much many of the large points that J Sai Deepak states in this discussion here. I think Dravidianism is an extremely dangerous ideology that finds false and ahistorical alliances: Brahmin-Sanskrit-North Indian-Hindu vs Non-Brahmin-Tamil/Dravidian-South Indian-Non-Hindu. I don’t think these are borne out of the historical facts and experiences of the region or have been furthered in this stark a way by Tamils themselves. Second, the bigger problem of course is the open call for violence especially in the 30s-50s in Madras against Brahmins, and the very vicious hate against Brahmins, Hindu religion and texts, and gods and believers. While I don’t think such violence to a staggering degree has occurred, Tamil society has been completely broken and polarised to an almost irreparable degree due to the ideology. Third, I also agree that a good part of Dravidian movement was about landed castes of low ritual status trying to vie for power and also the failure of Dravidian politics to do much for untouchables in Tamil Nadu. As to US’s remarks, I didn’t follow the speech in the entirety, based on what I understand it is unnecessarily provocative.

Now having said all of that, the agenda of JSD is too hard to miss and hence makes this conversation very problematic and going by its popularity already, really harmful. In the first part, on the little historical errors – I think deliberate – which are very telling. It is obviously true that missionary activity formed the bedrock of Tamil Nationalist ideology, but the bashing of missionary work is very misleading always not merely for the service – I think there is a lot in this – done by missionaries of the Evangelical-Danish tradition, but by way of exactly the aspects JSD talks about: scholarly. He cleverly identifies a few missionaries to make his larger point: Breaking India but completely suppresses the fact that their interlocutors are also missionaries.

Of course the Dravidian proof was furnished by FW Ellis, Alexander Campbell, and Robert Caldwell (the first of whom was not a missionary by the way) but the primary interlocutor of Ellis was William Carey of Serampore, a staunch evangelical, who believed Sanskrit to be the origin of all Indian languages (a conclusion he was convinced of by Brahmins in Bengal where he was based). The first stone tools in India were discovered by Bruce Foote, a missionary. Missionaries by virtue of being among the most learned men of the time ventured into intellectual pursuits. It’s easy to line up a few whose work in retrospect led to an inconvenient consequence to identify them as conspirators against your nation. Next, how does it matter who and to what end, the development of the Dravidian as a language family occurred when it is so sound-proof. It was a landmark movement in historical and comparative linguistics and the principles that made it possible also allowed the classification eventually of all language families. That this fact also led to Dravidianism should not make us credit such valuable work.

Now what was Ellis’ proof? It was his reading of Telugu grammatical texts written by Brahmins where erringly scholars name Sanskrit to be the ‘main type’, ‘Marga’ and their own language as ‘Deshya’ – the vernacular (Telugu owing to its highly Sanskritised literary culture adopted these tropes straight from it and was open to calling itself Sanskrit’s child). However, these same scholars call Tamil primarily as the Anyadeshya: the other vernacular. Ellis because of his interaction with Andhra Brahmins saw in this the story of Telugu and Tamil having a common origin. No work by any coloniser was ever done in isolation. It was informed by informants who demonstrated excessive influences upon the white men. Often misleading even. Now even Caldwell himself gets the word Dravida from Kumarila Bhatta (9th c?) in his Tantravartika used it to refer to a linguistic category. He said that Sanskrit Pandits had a tendency to find Sanskrit origins for all words in all languages but Dravida words are clearly distinct and we think he had Tamil in his mind when he is talking of ‘the Dravidian language’ (for all we know Kumarila is the originator of the Dravidian proof – maybe he is Anti-Bharat too?)

On the false animosity between Brahmins and Non-Brahmins. His choice of the example is one where the kings of India please the Dharmashastric vision of kingship where the Brahmin is on the top. But that tells almost nothing. That Brahminism and its understanding of religion excluded members of society was clearly widespread – best evident in the countless poetry where Brahmins are made fun for their haughtiness, but even better, Bhakti poetry where poetry in subtle ways are posed by lower caste characters. The prevention of Nandanar and Tiruppan Alvar from the temple in Tamil Nadu but also Kanakadasa in Karnataka and Namdev in Maharashtra are all great examples but in each of them, there is a bending backward of the Bhakta for the authority of the Brahmin – so I believe the divisive nature of caste merely did not lead to rampant protest (apparently Virashaivism in Karnataka may be an exception – there might have been violence on Brahmins too there) but oppression was acknowledged in innumerable ways. As to kings- there are exceptions there too. Unlike other non-kshatriya rulers who sought Kshatriya status, Kakatiyas in the thirteenth century famously were comfortable being Shudras and actively progressed an anti-brahmin agenda with a sharp decline of Agraharas, and commissioning of temples, with revenue being diverted to lake-development and other infrastructure activities.

That JSD alludes to Agrahara merely to talk of patronage of Brahmins by rulers and nothing else reveals so much. There were many kinds of land grants in India but by far Brahmadeyas are the most ubiquitous of all and most in number. The model of Brahmadeya is one where land is non-taxable by the sovereign or his vassal or a tax-collector, instead it is a self-serving unit. All tax money is to go for the maintenance of a few Brahmin families and revenue is raised from the work of all other castes. The inscriptions that he asks listeners to go consult always prohibit the encroachment upon these lands and place distasteful and harrowing punishments upon those who do so (one caveat I can think of though is that the instances of the execution of these maybe far less than the inscriptions envisage – but the ideal is clear and with premodern India one is always meant to correct for the ideal-reality gap). So much for “landless destitute Brahmin” and casteism being a “two-way street”.

Same with Modern Madras. It is preposterous to believe that a big part of respectable bureaucratic, official, and state positions were held by Brahmin, and yet no wealth either led to it or off it. JSD is right in that Vellalar and the many Thevar castes were landholding castes but that’s hiding the full truth – which is that Madras is the one region where others also held land unlike in Bihar and Bengal where land too was exclusively a Brahmin privilege. I am unable to find statistics for caste-based landholdings in Madras for the nineteenth and first half of the twentieth century. I am sure the data was collected but I’d have to consult the colonial documents – but it should suffice that Brahmin Mirasidars was a category in colonial revenue collection. And the at least one historian has acknowledged that the fee paid to serfs/pannaiyals by Brahmins was consistently less than by other castes because these services were read to be essential by the nature and structure of caste.

As I said, I think Dravidianism was a bandwagon for the landed and much of its outrageousness went unchecked but I think everyone looking at history should ask questions about normalcy of something instead of just distressing about it. I think it was connected to the real complaints that the dominant castes had about both the Congress party and bureaucracy – very reasonable and brilliant men in Andhra either uphold Ramaswami Naicker or had contested elections from Justice Party tickets; it was entirely kosher. How was this possible in spite of their friendships with Brahmin counterparts? This should have to do with some genuine complaints in society – this was what led to the blind eye to the very horrifying words and acts by Dravidian players.

It is almost amusing to see JSD take the side of the Congress for the colonial period – and his once again acute picking of two names as representatives: Rajaji and Besant, both clear apologists to Brahminism, especially the latter. Besant: “The caste system assigned learning to the brahmana and splendour to the kshatriya, wealth to the vaishya. It has been the glory of the brahmana to be poor. Millennia of studious poverty have built up a body of fine nervous development, refined, sensitive and admirably adapted for its functions and have chiselled out an incomparable brain that has not its peers, as a class, in the whole world. The brain of the average brahmana compared with the average of any other class in the world is superior. Individual brains may be found anywhere of the finest value but taking as a class, the average brahmana brain is unrivalled and it has a quality, a timbre if we may borrow an untranslatable word, which is unique. Natural law has been utilised and the result is there before us.” She was also famously upset with Gandhi’s Ashrams because she was scandalised with the prospect of Brahmin and Dalit children sitting next to each other. Now, why choose new heroes or even take sides with any historical figures merely to critique and expose Dravidianism? Can a fair historiography not be made without identifying “real patriots”?

My last point is relevant because in JSD’s exposition it is evident that he is not critiquing Dravidianism but really apologising to Brahmins and Hinduism and inasmuch as Hinduism is not exclusively Brahminism, to him it mostly is. And as long as men like J Sai Deepak use the Brahminical thrust to isolate and observe Hinduism, there will be calls to destroy Hinduism.

August 20, 2024

An Ethically Impoverished World: Commerce and Culture in Akshardham

If you are a Hindu residing in the United States, you might visit the Akshardham Temple (Robinsville, New Jersey). You are normally recommended to. Never mind if you do not know who presides over it and never mind also that when you go there you will not recognise any feature of a temple: you will break no coconut, you will hear no music, you will not circumambulate the outer walls of the temple. Well, you are not going there to practice your religion; you are going there to flag to yourself, to your neighbours here in the US, and your family back home that worries may be warded off. Indeed, you are still a Hindu, one to whom practice is of little meaning or effect, but identity is all. Here at Akshardham, New Jersey, religion for the modern world resoundingly announces: Identity alone is what remains of faith. Even if experience is of little consequence, make sure that you do not make an equivocal statement. Make sure not to cross lines in the world. Be Hindu [fill with any religion] and nothing else.

Once there, make sure to embrace your culture. Take pictures to share with your ‘Parivar’ and assure them that you have not forgotten Indian clothing. Even if you eat pizza at the cafeteria, make sure it has paneer, the quintessential Indian food. Why? Back home, you have Prasad (free as it often may be and served by volunteer devotees). And here this range of cuisines for the gourmet (never mind that a Prasad typically harnesses the spices of the landscape around and is tailored to the taste and lore of the god). And yes, when you click pictures, do not forget to pose with a folded Anjali. And you must look both savvy and “trad”. “T’rad” if you will. Also, you are in a safe space to take these photos. You are greeted by NRIs who will surely greet you with a ‘namaste’. Albeit with an accent.

After successfully ignoring the scores of images of Hindu gods and episodes of the Mahabharata and Ramayana carved on the pillars of the temple, it is time to think of the sculptors. Do not forget that the temple was built entirely in India, and then assembled here. Like cotton garments in 19th century Britain. Like shoes made in Cambodia and Bangladesh. Globalisation apparently is an institution by which profit margins are enhanced and the production process made efficient, by management from a headquarter, while raw materials and labour are sourced from various parts of the world depending on where these are cheapest and where exploitation of these gets away most scot-free. Marxians call this, fancily, neo-colonialism. We cannot but wonder: are we neo-colonising ourselves?

Sure, Akshardham temple of New Jersey is assembled in the most capitalist way possible but who cares about the workers? As Abraham Lincoln famously said on the battlefield of Gettysburg, what is for the NRI is also of and by the NRI. So instead of the workers in India who made this temple let us instead celebrate the “volunteer” sevaks from San Jose and Chicago who helped assemble this monument out of Bhakti for Swami Narayan by putting up posters of them across the campus.

Before we leave, just like in India we must carry a few Bhakti paraphernalia like Agarbattis, Stotra books, and images of gods to keep in our puja rooms. But oops! We have no time for any of that. How then do we still identify as Hindu? The gift shop has found us an ingenious way out. We can wear T-shirts now available with illustrations of the Swami Narayan saints, Ganesha, Rama and Krishna, and the Symbol OM. Of course religion is not an experience that lives through us but an object that can be worn and removed at will. And since we love the shirt so much let us also buy the T-shirt that says, “You are the stone, the sculpture, and the sculptor!”

Finally, we take a selfie wearing a hoodie made in some village in distant and unreachable India by weavers and artisans probably living in destitution that says, “A Landmark of Indian Architecture”. Makes complete sense!

March 15, 2024

ఉత్తిష్ఠ నరశార్ధూల!

“దేవి, నేను వెళ్ళాలంట” అని మందవదనంతో అన్నాడు రాముడు, తన మందహాసాన్ని ఇందువదనాన్ని పక్కన పెట్టి. ఒకే ఒక క్షణం తన చేతి వద్ద పరుగులిడుతున్న ఉడుతపై చూపు విసిరి తిరిగి లాక్కున్నాడు. సీతమ్మ విసిరే అడవి పళ్ళ చేత ఆ ఉడుత, వటుడి కంటే వేగంగా ‘ఇంతయ్యిం’ది. తను విసిరిన చూపుకు కారణం తన ముందు నిలుస్తున్న విరహమే. ఎంతో ఆవేశముతో మరోప్రపంచపు పిలుపులు ఘొల్లుమంటున్నాయి. ఆ ప్రపంచంతోపాటు రాముడి అవస్థ మారుతున్నది. రాముడన్న మాటకు సీత కాస్త మొహం చిట్లించుకొని అడిగింది: “వెళ్ళాలా? నాకు తెలియని, అందని పిలుపా? ఇదేమి విచిత్రము?” అని ప్రశ్నిచింది. “మరి నేటి కాల మహిమ అట్టిది ప్రియ. నీ స్మరణ లేనిది నా నామము లేదన్నట్టు గా ఇమిడి ఉన్నాము కానీ నా ఈ కొత్తింట్లో, ఏకాకిని అవ్వాలని నా పై ఆజ్ఞ. ఐదేళ్ళ పసివాడిని అట. అది నా జన్మస్థానం అట; వాల్మీకి అదే నా జన్మస్థానం అని అన్నాడట.” ఈ లోపల ఉరకలు తీస్తున్న ఉడత సీతాదేవి చేతిమీద తాను ఎంగిలి చేసిన పండ్ల, విత్తనాల ముక్కలను విడుస్తూ ఉంది. సీతమ్మ కాస్త అయోమయపు నవ్వుతో అర్థమయికానట్టు, “మన ప్రేమలో శాశ్వతమై ఉన్నది వియోగమే కదా మరి” అని అనేసింది, గాలిలో గాలితో మాట్లాడుతూ. కానీ అందులో వింత ఏముంది? తాను ఖిన్నురాలై సముద్ర దూరంలో ఒంటరిగా ఉన్నప్పుడే రాముడు ఆ గాలితోనే అన్నాడు మరి “వీచి, తనను ముట్టుకొని నా వద్దకు రా” అని, – నీవే మా మధ్య స్పర్శ కాజాలవు అని. తిరిగి ఆ వ్యథకై సిద్ధ పడుతున్నట్టుంది కాబోలు. నిశ్శబ్దపు తెరల వెనక తను కాలచక్రంలా మత్తెక్కించే వేగంతో తిరుగుతుండగా రాముడి ఆవేదనా నివేదనలు, ఆ చలనాన్ని ఖండించి తనను చూడమని బ్రతిమాలాయి.

“నేను అక్కడ ఉండలేననిపిస్తుంది” అని అన్నాడు రాముడు. కారణం అడిగింది సీత, ఏమో పెద్ద ఎమీ తెలియని అమాయకురాలిలా. రాముడు జవాబు వెతుకుతూ ఏ లక్ష్యం లేక ఏటో చూసాడు. ఈ లోపల “అవును అది కంబడే కదూ” అని అంటూ, తానె, “అవును లే కంబడే – ఎంత సొగసుగా మన కఠోర కాంతార ప్రణయ విహారాన్ని వివరించింది. మన చిత్రకూట నివాసాన్ని చిత్రీకరించింది.” సీత చిన్నగా నవ్వింది – ఎంతైనా రాముని మనసులో ఉన్నది తనకు తెలుసు కదా, బహుశా రాముడికే తెలియనంతగా. “ఆ కంబ కావ్యంలో నేను వెదురు కాడల మీద రాలిపడ్డ కుబుసచర్మాన్ని అయోధ్యానగరపు విజయధ్వజాలతో పోల్చినపుడు, అది కేవలం ఊరట కోసం కాదు. నేను వనవాసాన్ని అంతగా ఆస్వాదిస్తాను, ఎంతగానంటే…” అని హడావుడి పడి, చివరికి, “నీ అంతగా” అని ఊరుకున్నాడు. “అడవి యొక్క ముగ్ధ శోభను, పచ్చని సౌందర్యాన్ని, అవధి లేని శృంగారాన్ని ఎంతగానో ప్రేమిస్తాను. నిన్ను ప్రేమించానట్టే, భుమిజాస్రీ.” అదిగో – దొరికింది సీత అడిగిన కారణం.

వెలివేతకు పెట్టింది పేరైన తన భర్తకు అందిన ఈ ఆహ్వానం ఆయనకు మరో వెలివేత వంటిదే అన్న అలోచన చేత సీత నివ్వెర పోయింది. తనకంటే ముందే ఉర్దూ కవి కైఫీ ఆజ్మి నేటి మందిర స్థానంలో ఉన్న ముఘలాయి కట్టడం కూల్చి వేయబడ్డ నాడు ఆ చర్యను ‘రెండవ వెలివేత’ తో పోల్చడం గుర్తు చేసుకుంది. ఆ శయిర్ విన్నప్పుడే తన బిడ్డలా ఆ కవిని లాలించింది సీతమ్మ. అలాంటిది ఆ శిథిలాలపై, తాను దూరం ఉంచిన సుఖాల మధ్య పట్టాభిషేకం జరగబోతుందని గమనించి ఆమె – “అయ్యో ఏ స్థితి వాటిల్లుతోంది మీకు!” అని అనబోయి తనను తాను ఆపుకోండి. రాముడే స్వతః గా విలపించింది చాలు అని.

పైగా ఆ మాట స్థానంలో, లేని ఆనందం తెచ్చుకొని సీత, “రామా ఒక సారి నీవు లంక నుంచి అయోధ్యకు మనం తిరిగొచ్చిన రోజును గుర్తు తెచ్చుకో. ఆరోజు యొక్క పునరాగమనం లా లేదు ఈ ముహూర్తం?” అని ఓదార్చడానికి ప్రయత్నించింది. రాముడు కాస్త తలాడిస్తూ, పక్కకు ఉన్న రాయిని ముట్టుకొని, తన చేతిని వీక్షించి, చివరికి విరుచుకుపడ్డాడు. “అవును సీత. జ్ఞాపకం లేకేమి. మనం దిగ్విజయం తో అయోధ్యకు రావడం నిజమే కావచ్చు కానీ ఆనాడు భరతుడు నిర్వహించిన స్వాగత సన్నాహాలు గుర్తు తెచ్చుకో. కోసల ప్రజానీకం ఎంత కోలాహలంతో ఉన్నా, మనలో వేరే రసమే నిండి ఉంది. నా సన్నిహితులు ఎవరు ఆనాడు? జాంబవంతుడు గుర్తు ఉండే ఉంటాడు. ఎంత తత్త్వం కలవాడు అతడు. తన దరిదాపులకు నేను తూగుతానా?” సీత ప్రేమతో రామునికి దగ్గరయ్యింది, తన దుస్తులు చిన్నగా ఉసురుసురనేలా, తన గాజులు చిన్నగా గలగల మనేలా. రాముడి సొంత లోపం ఎంచే ప్రగాఢ నమ్రతనే అతనిపై అంత అనురాగం వికసించేలా చేసింది. “పోతే సుగ్రీవుడు. ఘనమైన పశ్చాత్తాపాన్ని మోసిన వాళ్లము – ఇద్దరు మా మా పడతిని రాజ్యాన్ని తిరిగి సాధించినా, ఎంచుకున్న శోకాన్నే ఆభరణంగా ధరించిన వాళ్ళము. హనుమంతుని గురించి చెప్పడానికి నా మాటలు చాలుతాయ? వైవాహికస్నేహానికై తను పడిన శ్రమ ఎటువంటిది?” ఈలోగా చుస్తే సీత చేయి రాముని చేతిపై పడుకుని ఉంది. తన చెయ్యే ఆ క్షణంలో సేతుబంధము. మరే సాగరమూ అడ్డు రాకూడదని తృష్ణ. ఆ నల్లటి వేలుపు సీత వంక ఓరకంట చూసినాడు. చూసి మెత్తగా పలికాడు: “ప్రియ, ఆనాటి గురించి నాకు మనసైనది విజయోత్సాహం కాదు. ఆ ఉత్సాహపు కాఠిన్యం లోపల చింతన యొక్క చల్లటి, తీయటి నీళ్ళు ఉండినాయి.” ఆ దంపతులు విషాదస్మితాలు విడిచారు. “కానీ నేడు చూడు సీతా” అని తిరిగి మొదలెట్టాడు రాముడు, “ఒక యువరాజులా, అనర్హమైన రాజస్సుతో, కలుషితమైన తామసమైన తళుకు బెళుకు తో ఆహ్వానితుడిని అయినాను. ‘అహంకారమే’ నన్ను చేయి పట్టుకొని తీసుకెళ్ళుతున్నది – లేకుంటే నేను దారి తప్పి పోతాను అని కాబోలు. ఎక్కడ సీతా, మన గాథలో ఉన్న ఆ నిధానము, ఆ స్థితప్రజ్ఞత ఏది? నాకు కనిపించదే ఈరోజు.” ఈ పాటికి అస్తవ్యస్తంగా ఉన్న రాముడు బాష్పావధి లో కేకలు వేసాడు, “నా జీవితాంతం ఎందరు నన్ను దేవునిలా చూసినా, నేను తిరస్కరించాను. లేదు అని మారాం చేశాను. ఎంత వింతో చూడు – నేడు కొందరు వ్యక్తులు దేవుళ్లగా మారుతుంటే రాయిలా తిలకిస్తున్నాను.”

సీత తన చేతులతో రాముని వీపుని తెరలా కప్పింది. మృదువుగా తన గడ్డాన్ని అతని భుజంపై కుర్చోపెట్టింది. తన చూపులను చిన్న చిన్న అడుగులు వేయనిచ్చి తొలుత రాముడి తీగల వంటి వెంట్రుకలను, ఆ తర్వాత అతడి పెద్ద చెవులను చూసింది. ఆ విధంగా బాహ్య సంపదను చూసినట్టు అనిపించినా, ఆమె నిజానికి దర్శించింది తన భర్తలోని భావాలనే. తన చూపులు అడుగులు వేస్తుండగా, ‘రాముడు చెప్తున్నది సత్యమే కదా’ అని అనుకొన్నది. ఎల్లప్పుడూ తాను సామాన్యుల దేవుడే కదా. అల్పులకు, సుక్ష్ములకు, నిరాదరణ కొన్న వారకు, ఆర్తి తో చూసే వారికి, ఓర్పు గలిగినవారికి, ఎదురు చూసిన వారికే కదా తను అనుగ్రహం చేకూర్చింది. ఈమెనే దృష్టాంతం. తన పొడవాటి, నిగనిగలాడే జడపై చేయి వేసి, ప్రేమతో కాస్త కురులను ఆడించి – వాటికి అవే జడలు కట్టేసిన రోజులను స్మరించుకుంది. నేటిలా బంతి పూలు చుట్టని రోజులు గుర్తుకొచ్చాయి. తను నిరీక్షించలేదా? సాక్ష్యాత్తు రాయిగా మారిన అహల్య ఎదురు చూపు ఎక్కడ పోవాలి? రాముడిని పెనవేసుకున్న శబరి ప్రేమను చుస్తే ఈమె కూడా అసూయ చెందకుండా ఉండలేదు. సంకెళ్ళలో బందిగా ఉన్న గోపన్న ఆర్తనాదాలు ఆమెకు గుర్తొచ్చాయి, త్యాగయ్య ఆర్ద్రత తో తడిసిన ఆయన కృతులు గుర్తొచ్చాయి. వారి భావన వినయాన్ని మించినది ఏదో. రాముడు ఇంకో మంచి మాట కూడా అన్నాడనిపించింది సీతకు. రాముడిని మనస్పూర్తిగా ప్రేమించిన వారి మనోఫలకం లో వారిద్దరూ కలిసే ఉంటారు. పైగా ఆమెను వారిలో ఒకరిగా లేక్కేస్తూ ఉంటారు. వారందరూ కూడా ఆయనకై అసహనంతో, కానీ ఓర్పు తో ఎదురు చూసే సఖులే కదా. ఆమె లాగ. అలంటి ఎదురుచూపు నడుమ, సీతమ్మ ద్వారా రాములవారికి వారి వేదన-వాంఛలు విన్నవించుకున్నారు. గోపన్న సీతను, “నను బ్రోవమని చెప్పవే సీతమ్మ తల్లి… లోకాంతరంగుడు శ్రీకాంత నిను గూడి ఏకాంతమున ఏక శయ్యనున్న వేళ…” అంటూ కదిలించాడు. ఈ దాస్య భావము నుండి త్యాగయ్య దూరమయ్యింది లేదు కానీ సీతమ్మకు ప్రత్యేకంగా ఒక కీర్తనంటే మహా మక్కువ: “మా జానకి చేతపట్టగా మహారాజువైతివి” అట! ఇప్పుడు ఆమె లేక రామస్వామికి ఒక రాచనగారా? అదే క్షణం ఆమె ఒంటరిగా “ఏక్ల చలోరే” అని పాడుకున్న ఆ ముసలివాడి గురించి ఆలోచించింది. ‘రాముని పేరు దాల్చిన ఒక హంతకుని గుండు తిని ప్రాణం ఒదిలిన నిమిషం కూడా రాముడి పేరే కదా పిలిచింది’ అని గుర్తు తెచ్చుకుంది.

అంతలో రామయ్య లేచినాడు. ఆడుతున్న గాలికి అడ్డుగా స్తంభంలా నిలుచున్నాడు. సీతమ్మ మాత్రం పిలుపినిచ్చి సూటిగా అడిగింది: “ఐతే ఎందుకు ఈ ఆలయం? ఏమిటి ప్రమాణం? అసలు అంత అర్థహీనమా?” రాముడు అంతే సూటిగా బదులిచ్చాడు: “అది ప్రజాకాంక్ష అట. జనాలు కోరుతున్నది ఇదేనట.” ఒక క్షణం సీత ఆగి, తిరిగి రాముణ్ణి వెంబడించింది. ఏమి అనలేదు. ఉలుకు పలుకు లేదు. సీతాదేవి లో నుంచి ఇంతసేపు లేని ఎదో కొత్త ఛాయ వెలువడింది. తన నిశ్శబ్దమే ప్రపంచాన్ని గగ్గోలు పెట్టినట్టయ్యింది. ఆ నిశ్శబ్దాన్ని తానే ధ్వంసం చేసి: “ఐతేనేం? అది నీవు నమ్మిన న్యాయం కాదా? నీవు నీ ప్రజలను సంతోష పెట్టాలని తపన పడవా?” సీత కళ్ళను చూడాల్సిన గతి ఆ క్షణం రాముడి మీద పడనందుకు సంతోషించాడు రాముడు. ఆమె చెప్పింది అక్షరాలా సత్యం కదా మరి. రాముడి రాజనీతినే నేటి ఒక దొర అమలులో పెట్టాడు. తనకు సూర్యవంశ సంప్రదాయం అని రాజధర్మంగా బోధింపబడిన విధానాన్నే ఇంకొకరు, సృజన లేకుండా, నేడు పాటిస్తున్నారు అని రాముడికి అవగతం ఐనది. తను ఎంత విచారించినా, నేటి ఈ ఉద్యమానికి తను తొక్కిన దారే ప్రమాణం. కాకపోతే ఈ పురాణ పురుషుడు తనను ప్రేమించిన భార్యను, ఆమె పట్ల అతడికి ఉన్న బాధ్యతను పణంగా పెట్టి, ఈ ‘రాజధర్మాను’సారం ప్రవర్తించి ఉన్నాడు. తాను ఎనలేని తేనెపలుకులతో కీర్తించిన ఆ ఘోరారణ్యంలోకే భార్యను నెట్టాడు. ప్రతి రాత్రి సీత ఏ పులి నోటనో పడుతుందేమోనని తల్లడిల్లినా, ఆమె బాగోకలను విచారించలేకపోయాడు. రాముడి గుండెను పరిమళపు పూవుగా వికసింప జేసిన భవభూతి కలంలో సీత స్నేహితురాలయిన వసంత అడిగినట్టు, “అపకీర్తి నీ ప్రాణంలా నువ్వు ప్రేమించే నీ భార్యనుంచి దూరంగా ఉండి అనుభవించే వియోగం కంటే ఘోరమా?”

లోకుల మాటకు బానిస అన్న వాదనకు రాముడి దగ్గర బదులు లేకపోలేదు. తాను ప్రజల మాటను గుడ్డిగా అనుసరించిన వాడు కాదు. లోకాభిరాముడు అనగా అర్థం అది కాదు – అని తను తిరగబడ్డాడు. జనాలు రమిస్తే చాలదు, అందరు – ప్రతి ఒక్కరు సమ్మతించాలి. ఏ ఒక్కరికి కష్టం వాటిల్లరాదు. ఇలా అనుకుంటూ ఉండగానే రాముడికి తాను కలిగించిన కష్టం గుర్తొచ్చింది. కాదు కాదు కష్టం కాదు కదా – మృత్యువు. ఒక యువకునికి, తాను రాజు పాత్రలో ఉండి కొడుకుగా చూసుకోవలసిన వాణికి, విధించిన మరణ శిక్ష గుర్తుకొచ్చింది. శంబుకుడు – ఆ పేరు రాముడిని ఎప్పుడూ తొలిచి వేస్తుంది. రాముడు తన ధర్మంలో భాగంగా ఎంతగా వర్ణాశ్రమానికి కట్టుబడి ఉన్నాడంటే, ఒక కుర్రవాడు ఎంత చదువరైతేనేమి, శ్రద్ధగల వాడైతేనేమి శూద్రుడు అయినందు చేత, తన రాజ్యం పై ప్రజలపై పడిన ఏ కష్టమైనా, ఆ కుర్రవాడు తన కులాన్ని మీరి తపస్సు చేయడం వలననే అని నమ్మినాడు. నిర్మూలించాల్సిన ఒక వ్యాధి, చిదిమి వేయవలసిన ఒక చీడపురుగు అన్నట్టుగా హతమార్చినాడు. మరందుకే కదా నామరామాయణంలో “స్వర్గత శంబుక సంస్తుత రామ్” అనడం అంతటి విడ్డూరం. రాముడిని ఆ క్షణం ఆ మాట ఒక ఉరి తాడులా బిగించుకుంది. తన చేతిలో చచ్చిన ఒక వ్యక్తి తనను స్తుతించడం ఏమిటి. “స్వర్గమనం” అంట. ‘భక్తుడు కనుక అలా అని ఊరుకున్నాడు’ అని రాముడికి తోచింది. ‘రామో విగ్రహవాన్ ధర్మః’ అని తను కావడమే తను చేసిన తప్పుగా భావింపక తప్పలేదు. ఆ ధర్మమే తన చేత ఇన్ని సార్లు అక్షమ్యమైన దూరాలకు తీసుకేల్లినట్టుంది.

తనను పీడిస్తున్న ఈ పశ్చాత్తాపంలో లేశం అంతయినా తనకు ఆహ్వానం పంపిన ఈ కోట్లాది ప్రజలకు ఇబ్బంది కలిగించిందా? తులసీదాసు ‘మానసం’ లో వాల్మీకిని రాముడు, వారు నివసించడానికి సరైన క్షేత్రాన్ని సూచించమని కోరినప్పుడు – మునికి టక్కుమని సమాధానం తోచకపోగా, కాస్త విచారించి, అనూహ్యంగా: “చెవులు” అని అన్నాడు, అనగా – రామకీర్తన వినే వారి చెవులు, పైగా స్తుతించే జిహ్వ, దర్శించే కన్నులు, రాముని పేరిట సేవ చేయు కరపాదాలు. కానీ ఇవన్ని కూడా నామరూపాల చుట్టూ సంచరించే వారికి వర్తిస్తాయి. వాల్మీకి ప్రకారం – రాముడి నిజస్థానం ధ్యానించే మనసు మాత్రమే. కానీ రాముని దృష్టిలో తాను దోషాలను ఎంచే వారి మనసులో కూడా ఉంటాడు. ఒక సారి సీతను చూసాడు రాముడు, వెన్ను తిప్పి. ఆమింకా మౌనంగానే ఉంది – నిలుచుంది, తాను మోసే నైతిక భారానిగా. ఇది వరకు లాగు ప్రేమగా దగ్గరకు తీసుకోలేదు. ఈలోగా చరిత్ర పడగలిప్పి బుసలు కొట్టింది – మరణించి, రక్తం అర్పించిన వేలమంది నాదాల రూపంలో. ఇది పట్టభిషేకమేనా? దేనితో అభిషిక్తుడు కాబోతున్నాడు? తానే ఇంత మంది అసురులను చంపినాక, తన సొంత భక్తుణ్ణి సైతం చంపినాక ఏం చెప్పజాలడు ఇప్పుడు? తన కథ యుద్ధానికి శంఖారావంగా మారిందా?

ఇంత చేసి తనకు వచ్చిన ఆహ్వానం తిరస్కరించలేడేమో. ప్రకృతి నైజం సీతకు తెలిసినంత క్షుణ్ణంగా మరెవరికీ తెలియదు. మరి ఆమె అందులోనే పుట్టి, అందులో నివసించి, నడిచి, చివరికి అక్కడికే చేరింది కదా. ఆమెకు తెలిసిన సూత్రం: రాముడి చరిత అతడు ఆ ఆలయంలోకి ప్రవేశించాలనే నిర్దేశిస్తుంది. తనకు అసహనీయమైన ఆ దర్బారుని అయిష్టంగా తను ఇంటిగా మార్చుకోవలెను. ఆయన మనసు తెలిసిన వారు మూగవారు కావలెను.

రాముడు తన ప్రపంచాన్ని వదిలి గృహప్రవేశానికి తయారయ్యాడు.