Michael S. Malone's Blog

June 15, 2016

Silicon Valley’s Cash McCall

The death last week of venture capitalist Tom Perkins, 84, brings down the curtain on the first, and greatest, generation of Silicon Valley leaders. A few aged pioneers still survive — such as Intel’s Gordon Moore, who attended Andy Grove’s memorial a few weeks ago – but most now limit their time in the Valley to rare visits. Perkins, almost alone, lived in San Francisco and stayed in the news, almost to the very end.

Like most of his generational peers, Perkins started out somewhere else – in his case in White Plains, New York, where his father worked in insurance and his mother was a part-time seamstress. And also like his contemporaries, he showed an early interest in electronics, which eventually led him to MIT and then into the East Coast world of Big Tech – for Perkins, it was Sperry Gyroscope. But most importantly, like the bravest of his peers, he soon went West, where the action was in electronics, and a young man could make his mark fast.

But, unlike most of the others – such as Moore, Robert Noyce, Charles Sporck, and Jerry Sanders – Perkins didn’t end up on the Valley floor, in the Wild West gunslinger reality of Fairchild, but up on the hill above Palo Alto in the New Athens of Hewlett-Packard and its enlightened founders. Thus, even as the Fairchildren fought each other to the death in the Valley below him, Tom Perkins helped lead the most admired company in history.

Perkins thrived in Bill and Dave’s world. With money came elegant suits and manners – and no little pomposity – even as the executives around him remained in their white short-sleeve shirts and skinny ties (in years to come Perkins would be appalled by the subsequent t-shirt and hoody generations of Valley pioneers). Image was everything: once in the early years, when HP public relations director Dave Kirby blew up some photographs for an executive meeting and appended humorous thought balloons, everyone laughed . . .except a furious Perkins, who was portrayed as looking down on lesser mortals.

But Silicon Valley has always forgiven ego – if it can be backed up. And Tom Perkins career was the equal of any figure in Valley history. At Hewlett-Packard, he led the company into computers –a trajectory that ultimately would make HP the world’s most successful computer maker. Leaving HP, Perkins teamed up with Eugene Kleiner and founded Kleiner Perkins (later adding the names of Frank Caufield and Brook Byers), the world’s most important venture capital firm. At KP, Perkins would participate in, or preside over, the creation of many of the iconic tech firms of our time, including Google, Genentech, Applied Materials, Compaq, AOL, Amazon, and AirBnB.

Though the partnership of the arrogant and acerbic Perkins with Kleiner, perhaps the sweetest human being to ever achieve Valley greatness, may seem impossible, it was nevertheless one of the most successful duos in modern business history. A decade ago, interviewing Perkins on stage about his new book, the surprisingly good Valley Boy, I asked him about Kleiner, who had died a few years before. Tears welled in Perkins eyes and for a moment, uncharacteristically, he was unable to speak.

Another Valley pioneer, Marshall Cox, used to say about his compatriots in the crazy early days of Fairchild that they all modeled themselves on a contemporary movie about a high-rolling, high-living entrepreneur: “We all wanted to be Cash McCall, baby.” In the end, no Valley legend ever achieved that goal more than Tom Perkins. With a fortune in the bank and growing weary of the daily existence of a venture capitalist, Perkins set out to spend the rest of his life in search of the next adventure. For a while, he assembled perhaps the world’s largest private collection of Bugattis. Then he sold them off to build the world’s biggest sailboat – the Maltese Falcon, a 289 foot, $150 million-plus yacht whose mast barely cleared the underside of the Golden Gate Bridge at high tide. He also married the romance novelist Danielle Steele and even wrote a novel of his own entitled “Sex and the Single Zillionaire.”

But, perhaps inevitably, it didn’t end well: divorce, a conviction for involuntary manslaughter when his yacht ran over a smaller craft and killed a crew member, and resignation from the HP board over revelations of spying by the CEO on Perkins and his fellow directors.

June 1, 2016

A Lost Generation of American Entrepreneurs

By Michael S. Malone

A recent report by the Economic Innovation Group has found that, while the years 1992 to 1996 saw a net increase in the U.S of 421,000 new businesses, and the 2002 to 2006 (despite a major recession) 405,000 new companies, the comparable interval from 2010 to 2014 saw just 166,500 new enterprises http://eig.org/recoverymap. Indeed, the years 2009, 2010 and 2011 saw a net loss of new companies year-over-year – the first time in a generation. Only this year, according to the Kaufman Foundation, has there been an uptick in new company creation.

In other words, the American economy is about 300,000 new start-up companies short as we stumble out of the long aftermath of the 2008 Great Recession and into a very uncertain economic future. How many Amazons, Facebooks, and Ubers were in those thousands of lost companies because they never gained financial traction, were crushed by regulations, or were never started at all?

These results are yet one more reminder that among the various legacies of the Obama Administration, this one – the loss of a generation of new entrepreneurs, their start-up companies, and the millions of jobs they might have created – may be the most enduring.

The magnitude of this “Lost Generation of [Millennial] Entrepreneurs”, as columnist Ron Hart calls it, can best be seen in research by the Federal Reserve and published in this newspaper. It found that the percentage of adults under age 30 who own or has a stake in a privately-held business is just 3.6 percent, the lowest in 30 years – a percentage almost half that of 2010, and a third of 1989’s figures.

These are devastating numbers – especially for a nation (as I wrote on these pages a few years ago) that was seen as among the most entrepreneurial societies in history.

What happened? A whole lot of things, including some dating back to the George W. Bush Administration. It can be said to have begun in the aftermath of the dot.com bust and the resulting market crash. Congress, with the Administration’s blessing, set out to punish the perceived corporate evil-doers like WorldCom . . .and in typical fashion, managed to shoot thousands of innocent bystanders instead. What had been a typical tech bubble, with a few bad players, instead became mass fraud in which every tech start-up needed to be handcuffed with the likes of Sarbanes-Oxley, stock options expensing, and new forms of board liability. The result was fewer companies going public, less democratic distribution of equity to employees, and dumber, more risk-averse boards. Meanwhile, seeing the changing odds for success, venture capitalists became less willing to fund early round start-ups, leaving that work to angels – who, as was their nature, invested more in their own kind, the networked and wealthy.

Nevertheless, and despite all odds, tech still managed to revive itself and produce the next great wave of start-ups, this time in social networking. But then came the Great Recession, and with it a new Progressive President. Historically, Progressives have never liked small business, preferring to govern in coordination with Big Business, Big Labor, Big Education, etc. – not with those armies of annoying shop-keepers and irritating tech nerds. And so, despite the occasional high theater of small business summits, almost everything the Obama Administration has done in the last seven years has been to the detriment of American small business start-ups, not least in tech. And it is just this contempt that may explain why the U.S. economy has struggled to exit the last downturn, even as we appear to be heading into the next one: no start-ups/no new jobs.

November 17, 2015

Hollywood and Silicon Valley: ReKindling a Failed Romance?

By Michael S. Malone

Hollywood – A decade ago, the big story was the emerging partnership between Hollywood and Silicon Valley. No one has talked that way now in a long time.

The dream was that the tech industry would provide the platforms and the tools, while the entertainment industry provided the content . . .and the result would be a revolution greater than the sum of its already gargantuan parts.

Today, with a few exceptions, that promise remains unfulfilled. Indeed the two camps are as separate – and antagonistic – as ever.

What happened?

One obvious answer is that what seemed a business challenge turned out to be a cultural one instead. The assumption that the two worlds were alike – innovation driven, consumer-oriented, entrepreneurial, increasingly virtual – has proven to be wildly incorrect. Steve Jobs may have gotten Hollywood to sign on to iTunes a dozen years ago . . . but that was more of a shotgun wedding, with Hollywood as the groom with no alternatives.

Hollywood, after all, is more than a century old, with long-established products and practices, and mature distribution and delivery systems. Dragging along this legacy, it is largely resistant to radical change – rather, it knows how to make profits. By comparison, Silicon Valley knows how to capture market share. Hollywood’s reputation for innovation largely comes from two things: the content of its productions and the tools it uses to make them. The truth is that the latest CGI blockbuster was created at the service of a business model little changed in decades.

This reality seems to have caught Silicon Valley by surprise. It was inevitable that the eternally impatient tech industry would quickly grow frustrated with the film business. Hollywood is about incremental improvements on generations of proven practices; Silicon Valley, driven by Moore’s Law, revolves around hitting the reset button every few years. And evolution and revolution make for unhappy bed-fellows.

These days, Hollywood seems fearful of Silicon Valley, tremulously waiting for the gearheads up north to once again pull the latest business paradigm out from out from under it, wreck its revenue model and crash its distribution channels. The Valley, by comparison, is increasingly contemptuous of the Southland. And in the spirit of ‘if they can’t keep up we’ll do it ourselves’, the tech industry has now seen the entry of Netflix, Yahoo! and Amazon in the movie and television production business.

Needless to say, this is not an optimal situation. Entertainment and tech are America’s leading contributors to the global economy. Having them work against each other is to nobody’s advantage.

For that reason, an event held recently at Paramount Pictures here may prove a milestone in the rapprochement of the two camps. The brainstorm of COO Frederick Huntsberry, and only possible with the hiring, as senior vice-president/head of new media, of Valley marketing veteran (Applied Materials, HP) Tom Hayes, the unprecedented event was billed as a summit meeting between tech and entertainment: ‘atoms meet bits’.

Shrewdly, the subject of the summit was not movies or television, but something much less contentious: Paramount’s new foray into theme parks, code-named “Alphaworld”. On this safe ground, it was believed, both sides could meet safely.

For three days, high-tech companies, from giant Intel to hot newcomer Oculus presented their latest, cutting edge wares – holograms, virtual reality goggles, personal robots, mag-lev hovercraft — that might be used to revolutionize the park experience. And Paramount, this time looking for just such a radical leap, listened. And to create the proper mood, the studio did what it does best – magic — by holding the gathering on an elaborate set in a historic studio that had seen the filming of everything from Shane to Star Trek.

The real action came between presentations, when the techies formed up teams and devised radical solutions, using these new inventions, to the 21st century theme park challenge. Some solutions were practical, such as reducing lines and micropayments. Others were so far-out that participants and observers had to sign non-disclosure agreements – suffice to say that they were mind-boggling, the kind of stuff you see in Hollywood science fiction films.

Is Hollywood willing to contemplate, much less implement, such radical ideas? And is Silicon Valley patient enough to let its southern cousin do what it does best: find the most successful way to tell compelling stories? Both remain to be seen. But this Silicon Valley-meets-Hollywood summit was a beginning. For everyone’s sake, let’s hope it’s the (re)start of a beautiful friendship.

October 6, 2013

Why Progressives Always Get Tech Wrong

Progressive Party Membership Certificate, 1912 (Photo credit: Cornell University Library)

Two technology stories have filled the airwaves in recent days: the impending Twitter IPO, which is predicted to raise more than $1 billion; and the Obamacare online roll-out, which has crashed in a welter of locked-out applicants and frozen exchanges.

The connections between the two events are deeper than you might think – and they represent the latest milestones along the diverging responses by industry and government to the birth of the technology revolution more than a century ago.

The impact of information technology on business is well known to folks working in the private sector. It has been the subject of hundreds of books and is central to the curricula of most business school and executive training programs. Its basic message for the last few decades is: because of Moore’s Law (constantly accelerating the rate of change), globalization (rapidly expanding the customer base), and the Internet (giving users the information they need to make their own informed decisions), the traditional model of top-down, command-and-control decision making that characterized corporations through the 1950s is both obsolete and dangerously self-destructive.

Thus Twitter, the next great Silicon Valley IPO, following Facebook and Google, two other celebrated companies with hundreds of millions of ‘users’ – but more accurately: empowered, unpaid volunteers – and comparatively tiny staffs.

This lesson has never been learned – or more accurately, has been learned backwards – by our Federal government. And no group has run further in the wrong direction, all the while claiming to be more technologically savvy than its political counterparts, than the Progressives. From the original Roosevelt/Wilson/Brandeis party, through the New Deal, to the Great Society, and now the Obama party of Hope and Change, Progressives have assiduously aligned themselves to the latest tech revolution, courted its leaders . . .and then extracted from it exactly the wrong lessons. Thus, President Obama, who was elected with the help of social networks, regularly flies out to the Valley to sup with the Brahmins of high tech, listens to their ideas . . . and then goes back to Washington forever unenlightened by the real lessons that the careers of his dinnermates have to tell. Even the late Steve Jobs tried to warn him about micro-managing the economy. But the President, wearing Progressivism’s blinders, didn’t listen.

Though it had roots as far back as Charles Darwin, the divergence between the two paths took place at the end of the 19th century with the work of scientist Fredrick Winslow Taylor at Midvale and Bethlehem Steel Companies. The story of Taylor’s research is well known – it is often taught, wrongly, by Progressive-tinged history texts to schoolchildren, as the zenith of industrial exploitation of workers. That is, by using time-motion studies, Taylor learned the most efficient way for factory workers to do their tasks; then corporate bosses took those techniques, speeded them up, and dehumanized those same workers by turning them into overworked machines. They revolted, which led to the rise of trade unions.

The reality is more complex. What Taylor realized, and proved, was that work was a measurable activity that could be systematically made more productive using scientific techniques. But Taylor also argued that workers should be rewarded commensurately with their increased productivity – something management didn’t agree with . . .and paid for with labor strife for the next half-century. Industry largely learned its lesson – and when it forgot there were forward-thinking entrepreneurs to remind them: like a young David Packard, who told a gathering in the late 1940s of the nation’s biggest corporate executives that if they didn’t trust and empower their employees even more in the years to come, they were doomed. History proved him right. And smart CEOs changed their practices because, in the end, they valued profits over power.

But many of the nation’s political leaders saw the Taylor experiments differently They went for the power that came from a big, centralized government. In the weird amalgam of contempt and pity for the average man that has always characterized this ideology, the Progressive saw a confirmation that human beings really were essentially machines (there aren’t a lot of truly religious Progressives), whose performance could be improved using scientific techniques. Indeed, with the right performance targets in place – and the Progressives had their list – the entire population could be controlled and pointed in the right direction to Utopia. Most of this agenda was camouflaged by the calls for ‘social justice’ and the positive improvements in public health and agenda for which the Progressives are still celebrated today.

But Progressivism failed, and it continues to fail today – Obamacare, the bailout, cash for clunkers, etc. – because it still adheres to two long-disproven ‘truths’:

All problems have scientific/technological solutions;

Those solutions can be imposed on everyone by an enlightened few who know what is best.

Add to that an underlying belief, undeterred by historical evidence, that human society is perfectible, and everything is in place for a tyranny of good intentions – and a ‘scientific’ justification for imposing it.

If we have learned anything (not least from Progressivism’s crazy cousins Fascism, Nazism and Stalinism) over the last century it is that none of this is true. Human beings are messy and unpredictable creatures, with 10 billion different perspectives and opinions about how to live a good life. There are also more good ideas, intellectual capital, in those 10 billion brains – especially regarding some problem at hand – than in the combined faculty of Harvard and Stanford. Moreover, some people actually prefer liberty to comfort, freedom to happiness. That’s what Steve Jobs was trying to say; and that’s what’s going unsaid at those select Valley dinners with the President.

So, instead of a healthcare Twitter, we get a gigantic mess as the government tries to impose a single, software-driven system on 300 million Americans. Anyone who has ever worked on or, worse, bought a big software application – and this is one of the biggest in history — could have told HHS that the final result would be buggy, late, unsatisfying to users, unable to live up to its billing, and most of all, resistant to upgrades, much less wholesale changes. In the real world, you can’t just order “Make it so!”

Whatever else it was, Progressivism was a top-down, mass-control, limited-freedom political philosophy that has only grown more anachronistic as the decades have passed and as, ironically, technology itself has increasingly supported de-centralized, networked, and bottom-up institutions. Corporations learned that a generation ago (or they disappeared). In successful corporations today, management works best when it is the servant of employees and customers: look at the backlash from a billion users every time Facebook or eBay tries to impose some new rule or pricing scheme from above. And what are open systems and crowd-sourcing but the next evolutionary step in the inversion of the old top-down model?

That leaves the federal government the last true bastion of late 19th century command-and-control thinking. It can build as many websites and social networks as it likes, but as long as it tries to impose mass solutions from the top in a world of personalized solutions from the bottom, it is doomed to fail – and our nation continue its slide into debt and enfeeblement.

September 30, 2013

The New World of Passion Television

Television (Photo credit: *USB*)

I can’t remember the last time my older son, 22, watched television for ‘television’ – that is, for traditional series, movies and other content. Sometimes, late at night, he sits in front of the television, but always to play video games on the big HD flat screen.

Most of the time, he sits at his laptop, watching videos. It is a habit he picked up in Oxford, where he had no television (and didn’t want to pay the fees) and where video download portals (legal and illegal) were ubiquitous. And that’s how he continues to find his entertainment; surfing from obscure documentaries to Opie & Anthony YouTube feeds to strange indie films . . . wherever his passion leads him.

My younger son, 17, loves watching TV, but has little interest in regular programming (beyond “Breaking Bad”). Instead he sits at his laptop researching obscure plant species (he wants to be a plant biologist) while the TV endlessly plays in the background classic television series, from TJ Hooker to The Office. He knows more trivia about Seinfeld and Friends than most of the Gen Xers who grew up on those series. Unlike his brother, his passion is for continuity, not novelty; a soak in the curious-but-safe past rather than a high dive into a dysfunctional present.

My wife and I, being good Baby Boomers, like the spectrum in-between our two sons. Except for sports, we watch an old Sony Trinitron. We gave up on the networks long ago, but nevertheless have a predictable pattern of watching series we like on cable, PBS Mystery and Masterpiece Theater, cable news, and the occasional on-demand movie. My wife is a big fan of old films on TMC, and I was a loyal viewer of the History Channel until it succumbed to the siren call of Reality TV. You might say that our passion is for quality television in a predictable format, venue and schedule – one that requires a minimum of channel surfing and schedule searching.

Thus, though our desires are very different, all of us are still passionate about television, in whatever guise it appears. We still look to it to fulfill those passions for entertainment, experience, information and education. But each of us, in our own way, is frustrated by television as it is. And each of us has developed our own work-around to escape those limitations. Surely there is a way to give us television that matches our passions and yet is easy to find; something that combines the pure entertainment value of old-fashioned television (i.e., turn on your favorite network and watch it all evening) with the power and scale of the Internet Age.

We are hardly alone. In fact, as casual survey of the blogosphere and the comments pages of major entertainment web portals (like this one) suggest that we are, in fact, typical. And while the cable companies, such as Comcast, still tout the fact that they are giving us everything we want, few of us think they give us what we need – television content driven not by the opportunity for the provider, but by the passions of the individual viewers.

And as it happens, just such a new industry is emerging. Call it “Passion Television”. Right now it is just a handful of small, but well-funded start-ups, most of them in Silicon Valley, each with a different vision of how to answer this need. But they could just be the next great revolution in television. Two of the hottest of these start-ups are Net2TV and PivotTV.

The Epiphanies Behind Net2TV

For media industry veteran Tom Morgan, the explosion of programming and channels over the last 10 years was a two-edged sword.

On one hand, viewers loved the seemingly endless supply of video content – old television shows, web videos, raw news footage, etc. – now available on TV and the Web. On the other, all of this content came with as much frustration as delight. Too much of it was uninteresting junk, and what was interesting was almost impossible to find. TV, he reminded himself, was supposed be entertainment, not an endless, wearying search.

Why Morgan asked, couldn’t targeted video content be delivered, grouped according to a viewer’s interests, passions?

“As they say,” commented Morgan, “One point makes an idea, two points make a strategy, three points make a business.” Morgan should know. He founded BlackArrow, then later took on strategic roles at Move Networks supporting ABC.com, and finally spent a term at Virgin. All the while he kept noticing that consumers were unhappy – not with the quantity of programming available, but by their inability to find what they wanted.

“It was apparent that, despite all of the competition from games and the Web, consumers still wanted to watch TV. But they were tired of searching for channels containing personal topics of interest, and that didn’t bury them in irrelevant advertising.”

There was still the universal complaint of, in Bruce Springsteen’s memorable phrase, “Five hundred channels and nothing on.” Not that there wasn’t enough interesting content out there – it was just too scattered around cyberspace. Moreover, a lot of it exhibited the most frustrating feature of the Age of YouTube: short, less-than-5-minute, formats.

“Personal relevance,” he says, “was the hallmark of the previous generation of cable television – networks like Discovery, A&E, and Bravo got rich delivering just this kind of content to viewers. But now they’d jumped on the reality programming fad, and left a void of just this kind of content.” It struck Morgan that this void offered a tremendous business opportunity

Television content was now available on hundreds of channels, an uncounted number of websites, and scores of platforms from traditional television to smartphones and game consoles.

“It suddenly struck me that the time was ripe for the low-cost delivery of existing and newly-created non-fiction content, in a longer format – even if that meant stitching together archival short pieces,” said Morgan. “But even more than that, the opportunity was there to bundle this content together on single channels based upon a user’s passion.”

So he teamed up with another television veteran, Jim Monroe – who had his own epiphany when his 21 year-old daughter asked him “What channel is ABC?” – and founded Net2TV. The company eschews traditional distribution and programming models – instead, users can simply call up specialty channels through their television’s Internet connection, skipping television cable altogether.

Net2TV offers the kind of narrowcast channels that were unimaginable a decade ago: continuous access to live and recorded programming on everything from the Popular Science’s “PopSci” to cooking shows to a newscasts from Newsy and AP, all without paying for hundreds of other channels. This is the format for my wife and me – and probably as it expands, for our younger son as well — as right now none of us consistently watches more than a half-dozen of the several hundred cable channels available to us, and at no small price.

None of Net2TV offerings are broadcast, but rather reside as a vast archive in the Cloud, so that the user can tap into the material anytime, selecting based on interest. And while you may find the concept of watching three hours of experts showing how to cook the perfect lasagna, followed by detailed directions on how to sharpen cooking knives, to be excruciatingly boring, a lot of people out there find the idea riveting. And, in doing so, they have pre-qualified themselves for hyper-targeted advertisers of the type marketers used to only dream of.

Right now, Net2TV is available only on Philips television and Roku, but it is scheduled to be available on 20 million connected screens by December. It is preparing for this by expanding its studios for live feeds and increasing the number of platforms on which it will be available. It is also busily securing independent film and short-format videos that it can knit together and repackage into longer programming for its audiences.

User Defined

Passion TV can be characterized as television defined by user interest and not by delivery system or viewing platform. In Morgan’s words: “Programming with personality and a passion, on any screen the consumer wants, with complete mobility.”

Says Will Richmond, editor of VideoNuze, an influential online publication covering the new video space, “Online content has long been about filling infinite interest-based niches and the same phenomenon is now happening in video. We’re witnessing the natural evolution from 3 broadcast networks to 500 cable TV networks to millions of online channels. Changing consumer behaviors and the relentless pace of technology innovation fuels it all.

“Name the interest category and it’s likely there’s high-quality video in it. Examples include gaming, cosmetics, how-to, comedy, toys – the list goes on and on. Investors have taken note and have poured tens of millions of dollars into niche content providers.”

This content is of increasingly high quality, and often free – which is why a company like Net2TV is taking this short form content and turning it into full-length TV shows with logical story sequencing.

Passion Television – whether full TV programs or short video clips – has two key elements that distinguish it from traditional network and cable television:

– It is narrowcast: The Passion TV viewer isn’t interested in hundreds or even thousands of channels – 99 percent of which contains content they aren’t interested in (though are still paying for). Even the channels they do want are compromised by added programming designed to capture new viewers (for example, History and Discovery channels’ shift away from history and science programming towards larger-audience enticing reality programming). Passion TV takes advantage of the fact that technological advances (Cloud, Web services, high speed wireless, etc.) now make possible the long-held dream of being able to deliver to individual users content customized to their individual interests.

– It is structured: There are a lot of massive databases of video content out there (think Netflix), but they inevitably require the user to conduct endless searches with limited knowledge. That’s fine for some viewers, but for most people television is still perceived as a passive medium – something you watch while you are doing something else. And that calls for the packaging programming with studio-based hosts to tie all of the pieces together (think early MTV) into a continuous stream of shows, studio intros and a limited amount of passion-related advertising running 24 hours per day. At Net2TV what little navigation is required between channels is handle by a simple user interface called Portico with hosts who help viewer discover new, and relevant programming.

“What we’ve learned,” says Morgan, is that people love to watch TV that connects with their own personal passions. If we can make that experience continuous, they will keep watching for hours.”

Says Richmond, “This passion-driven viewing is being accelerated further by the convenience and personalization of mobile viewing. Tablet and smartphone-based viewing are skyrocketing and displacing desktop viewing. Next up is viewing on connected TVs, whether through devices like Roku, Apple TV, Xbox and others, or by a new generation of low-cost dongles like Chromecast that converge video from mobile devices to the big screen.

The new generation of television providers recognize that their typical user is not only not attached to the traditional cable television screen, but may have consciously abandoned it for the various other platforms now available, from web-enabled TVs to laptops and tablets to smart phones. The crucial difference is that the content is no longer being delivered by a dedicated cable service for a fee, but rather via the Internet, often using the vast storage capabilities of the Cloud.

Participant‘s Pivot TV

Net2TV is only one pioneer in this new field of Passion Television. Consider PivotTV, which launched this summer. Founder Jeff Skoll is celebrated figure in both Silicon Valley and Hollywood. Skoll first came to the public eye as eBay’s second employee and first CEO. Having made a fortune there, instead of diving back into the high tech pool, Skoll decided to change the world by creating the Skoll Foundation, a leading funder of the new-style nonprofits that are based social entrepreneurship. [Note: the author once served on the board of the Skoll Foundation.]

Having revolutionized that field, Skoll then turned to do the same in movies, founding Participant Productions, which knocked Hollywood on its ear by producing (in just its first few years) such lauded and culturally influential films as Syriana, An Inconvenient Truth, The Help, and Lincoln. What made these movies memorable, beyond their critical success and multiple awards, was that they combined high production values with strong political views—and that they reached out beyond the theater, via social networks, into social activism. In the process, Skoll and Participant changed the world of cinema.

Now Skoll has turned to television, hoping to create a similar revolution with Pivot TV. Pivot promotes itself as a new kind of television for “Passionate Millennials”, which it calls “the New Greatest Generation.” To reach this audience, Pivot is using a vast repertoire of content including original series, existing programming, films and documentaries.

Pivot TV could have been invented with my oldest son in mind. In the company’s words, it “focuses on entertainment that sparks conversation, inspires change and illuminates issues through engaging content.” But crucial to its model is that this programming will be available on a wide array of platforms, including traditional Pay TV and an on-demand streaming option via Pivot’s proprietary, interactive and downloadable viewing app. And, of course, in keeping with Skoll’s history at Participant, Pivot also will be integrated with its own social networking website, TakePart.com, to get viewers to actively become engaged with the content.

Wild West

Net2TV and PivotTV represent opposite ends of the Passion TV world: one appealing to existing passion for special-interest programming, the other a precise demographic. In-between can be found a growing number of content delivery companies, some old and some brand new, that have recognized the power of narrowcasting and passion-based programming and are moving quickly to take advantage of it.

Veteran programmers that are finding a new Passion-based format to their existing long-form content include CNet and Newsy. Amazon is heading into this space as well, taking advantage of its dominance of the consumer Cloud world. And the recent announcement of the Esquire Channel, based upon the content and philosophy of the venerable men’s magazine suggests a possible new strategic direction for the struggling print magazine industry – itself a “passion” industry created 150 years ago.

“For now”, most of this passion video is advertising-supported,” says Richmond. “But to the extent that they build audiences and loyalty, we should expect to see them tap into paid models, whether subscription, pay-per-use, commerce, product placement and other forms.”

No doubt there will soon be many more passion-based networks and content providers, especially once companies like Pivot and Net2TV prove the concept. And, of course, by definition ‘narrowcasting’ offers the potential for an almost unlimited number of markets.

Says Richmond, “The Internet’s unlimited shelf space and low cost of entry mean a proliferation of video is still ahead. Of course, not all passion content will ultimately succeed, but for now it’s a Wild West, with lots of experimentation and opportunity ahead.”

If that experimentation means a happier, more passionate television experience for me and my family, let the Wild West show begin.

September 27, 2013

An Angel Bestiary

Dear Readers: I’m back after being several months away buried in writing a big new history of Intel Corporation — 200,000 words, which should make for about a 400 page tome. It’s tentatively entitled The Intel Trinity and it will be published next spring (HarperCollins). I’m also about to embark on a co-authorship of a new book with Rich Karlgaard, publisher of Forbes on a subject that is still under wraps. In the meantime, I propose to fill this blog with some recent articles I wrote about the world of tech start-ups and venture capital that were published in Innovation magazine (including the one below), a reported piece on a new kind of television, and an excerpt from my newly published novel, Learning Curve: A Novel of Silicon Valley.

AN ANGEL BESTIARY (reprinted from Innovation Magazine)

The Silicon Valley zoo is beginning to fill with strange beasts. Few of them are tame, and many are downright ferocious.

In my inaugural column for Innovation I discussed how the combination of venture capitalists, grown ultra-conservative after being burned in the dot.com boom, and angel investors, with more desire than liquidity, had created a wide and nearly uncross-able gulf for new tech start-ups trying to reach the all-critical “A” series round of investments to make their products real.

My own start-up company, of which I’m co-founder and vice-chairman, has been camped on the near bank of that gulf now for several months. On three different occasions now we have thought we had a bridge in place to make the crossing – and all three times, it has disappeared at the last moment. I know a lot of other start-ups that are now in the same boat. Whether any of us will make the crossing is as yet unknown . . .and it holds serious portents for near-future of the U.S. economy. It is, after all, new ventures like ours that produce most of the new jobs in our economy.

What makes it all even more frustrating for those of us in the game is that we know that if we can only get to that Series A, where real venture capitalists put in real money, the path is smooth and straight, with the VCs ready and willing to write checks for millions – even tens of millions – of dollars to their pet companies. But getting there, especially with the economy threatening to turn south again, is getting harder and harder. And in the meantime, several thousand companies are camped on this side of the gulf, looking in envy at the far-off lights and dealing with the predators that roam in the woods around them.

Having encountered more than my share of these strange beasts, and in hopes of sparing you some of my own bad experiences, I thought I’d create the following bestiary of some of the Valley’s most exotic – and dangerous – new creatures. The good news these days, everybody wants to put their money in Silicon Valley’; the bad news is that anybody with a thick wallet and free lunch hours can declare themselves an ‘angel investor’ and make life miserable for struggling entrepreneurs. Here are some examples:

The Eternal Tire-Kicker – This type of ‘investor’ can usually be found at dinners and presentation events put on by the Band of Angels and other investor groups – especially those chapters located outside the Valley. These folks have made a few bucks over the years and now they want to be players on the cutting edge of the high tech revolution, they want to be company builders, and most of all, they want to be cool. But that takes a level of risk, of courage, that the Tire-Kicker isn’t willing to make. He (and, quite often these days, she) wants the sure thing that he will never find. Instead, he goes to all of the dinners, listens to the pitches by start-up teams, perhaps asks a few questions and swaps business cards afterwards. But he will never, ever invest. [Note: after this was first published I got an angry email from the Band of Angels that pointed out that over its existence its members have invested millions in start-ups. Duly noted. That said, I invite you to attend one of their meetings and draw your own conclusions.]

The Reluctant Legend – This investor looks great on paper. He’s had a great career in high tech. And, were he to invest, you’d probably make him chairman of the board. But before that happens, he’s going to put you through endless meetings with both him and his partners/technical advisors, he’s going to make you meet all sorts of milestones, and expect you to make strategic decisions and hirings and conduct expensive market research . . . all on the belief that he is going to come in with both money and experience. But the truth is that he was never going to invest in any company different from those he’s made money on before, in his little corner of the industry, in a market he already knows. And you will never meet those standards – though you will walk away, penniless, honored to have met the Great Man.

The Thanks for the Show – The most common Angel of them all. In fact, in Silicon Valley you can go to lunch five days a week with this creature. They are all very nice people, with good resumes, and they appear to have money to invest. They will eat the meal you just paid for, and will listen attentively to your presentation and slide show. They will even ask some very good questions, and perhaps recommend someone else you can speak to. But they were never going to invest in your company, even if they wanted to. They don’t have any money, or it’s invested somewhere else. They are only meeting with you because they are curious, or gathering information for their companies, or looking for a job . . .or simply because it’s a lot of fun to be the center of attention over a free lunch.

The Doomsayer – These creatures have a creepy love-hate relationship with entrepreneurs. They love the whole start-up world, yet they devote their time to explaining to every team they meet all of the reasons why they will never make it – the market’s too young/too mature, there’s too much competition/no competition so it can’t be real, you don’t have enough expertise in the industry/you are too bogged down in the old industry paradigm, etc. Bottom line: you are doomed to fail. On the other hand, if you do manage to succeed, they will take credit for having warned you of all the land mines in your path. Investment? Be serious, not with the long odds you’re facing.

The Money Bags – This guy usually has a lot of dough, and he knows it. He also got that rich because he puts money above all things, including loyalty and fairness. He is affable but detached: he knows you need his money, and that gives him the right to toy with you for as long as you are willing to be his cat’s paw. If he does decide to invest, he will show where his priorities lie by discounting your team’s innovation, sacrifice and months of hard work to a fraction of its true, all why demanding an unseemly share of the company for his cash. The worst part of it is, you’ll happily take Money Bags’ money . . .and thank him with all of your heart.

The Delicate Dilettante – This figure is often the later generation of old money. He or she loves what you are doing – though doesn’t quite understand it – and promises, too quickly, to make a huge investment. Will she? Flip a coin, because that’s about how rational the end-result will be. You may get the check tomorrow, or have a dozen affable meetings over the course of six months only to get a distracted ‘no’, or the Dilettante may just fly off in the morning for three months in Rome and forget all about you.

The It Ain’t Over ‘Til It’s Over – The dream Angel – smart, understands your business, great to work with, knows the market, lots of connections – right up to moment you are ready to ink the deal. That’s when you see their dark side: now they want the deal renegotiated under much less favorable terms. Oh, and all of these other amendments to the contract, too. Suddenly, the pen poised over the contract takes two months to actually reach the paper, if it ever does. Just how much will you give up to make the deal? Mr. It Ain’t Over ‘Til It’s Over is going to find out.

The Land Shark – Finally, beware most of all of this one. They are rare, but often fatal. Typically they come from a different industry where the rules a very different from that of high tech – such as real estate development — where the profits are largely predetermined and it is winner takes all, and the concept of being a team player, or of taking a small piece of gigantic pie, are anathema. For these guys, even crushing their friends is a badge of honor. It’s winner takes all. Even a background check may not help you – these guys can have great reputations in their own Darwinian industries. The initial conversations will be friendly, and in time the Land Shark will even talk seriously about making an investment – even reach a tentative agreement. But then, when you get down to details, Mr. Nice Guy turns into Mr. Rapist. He’ll still invest, but only if you meet his impossible, insane demands. He wants the company – and hey, thanks for the lesson on your industry’s cap tables and valuations — and you as his employees. He knows all of your weaknesses and exactly how much his money is worth – and he is quite happy to show you his multiple rows of teeth. Taking his money is akin to entering into voluntary servitude. That said, the Land Shark serves one useful purpose: he helps you discovery how much integrity you really have.

June 14, 2013

The All-Seeing Eye

The other day, my college age son quietly went around the house and put electricians tape over the camera lenses on the displays of all our home computers. I laughed when I discovered what he had done. . .then paused: after all, it wouldn’t be that hard for someone to remotely turn that camera on and secretly watch me and my family. I left the tape on.

This is what it has come to. The revelations of recent days about the NSA being able to spy on the phone calls of millions of everyday Americans, without warrant, in search of a few possible terrorists has made everyone just a little more paranoid – and a little less trusting of the benign nature of our Federal government. The reality is that we may not yet be paranoid enough.

I come from a spook family. I was born in Munich while my father was running counter-intelligence missions for the Air Force OSI into Eastern Europe; and by the time I was a teenager in Silicon Valley he was working in security at NASA. Being in such a family gave one unique insights into the hidden workings of the world.

Thus, I can remember at the height of the anti-war movement in the late 1960s watching local anti-war protests on television. When one of the leading radicals denounced the FBI for following him and his cohorts, my father chuckled and turned to me, “You know how many FBI agents there are in Palo Alto? Two. They couldn’t follow those people even if they wanted to.”

Then, and for many years afterwards, that was a comforting bit of information. Sure, as the information age progressed we were turning more and more personal information over to the retailers, strangers and government agencies – but we were still comparatively secure because those terabytes and petabytes were just too much of a tsunami of data for even an army of voyeurs to look through to find a teaspoon of valuable information about the bad guys.

But – ironically, because I make a career writing about it – I forgot about the power of Moore’s Law and its biannual doubling of computing power. The Law had kept ticking all of those years, bringing one transformative technological wonder after another: personal computers, smartphones, the World Wide Web . . .and now the newest miracle was the conjunction of superpowerful computers, ‘free’ cloud-based memory storage, and potent new analytical software to take advantage of both. Together, this new technological revolution was called Big Data – and it promised to change the very nature of our relationship with the world around us.

Last year, I wrote the copy for a celebrated photography book called “The Human Face of Big Data” and in it I extolled the fact that this new technology meant the end of sampling and statistics. Soon, I wrote, we would be able to measure everything and all of the time – every tree in the Amazon basin, every fish passing some point in the south Atlantic, every blood cell in our body, in time even every gust of wind on Earth. And then we would use the powerful new diagnostic tools to bore down and find hidden trends and extract precise details within these unimaginably vast databases. As I was celebrating the manifold virtues of this new technology it didn’t cross my mind that it was already being used on me. I trusted the companies that managed this, I trusted my own government . . .sort of. What I really trusted was my father’s comforting words. When I heard about Yahoo! caving before the Chinese or of a secret meeting between Google’s Sergay Brin and Homeland Security director Janet Napolitano at a Los Altos coffee shop, I dismissed them as isolated events. What I failed to recognize was that, with Big Data, my father’s world of intelligence gathering had become obsolete.

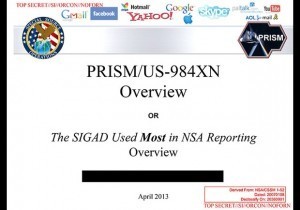

It is an old truism that technology revolutions arrive more slowly than we predict, but quicker than we are prepared for them. We saw this coming as long ago as George Orwell, but now that the NSA’s phone surveillance and PRISM online data mining programs have been exposed, we are stunned. Needless to say, most shocked of all are our elected representatives, who for last century have been notorious for being too lazy to keep up with the pace of technological innovation and its cultural and economic implications until forced to react.

No doubt once again there will be a mad scramble in the Capitol to do something – new regulations, new oversight, new attempts to protect civil liberties. But, thanks to Moore’s Law, the technology will have already moved on. Is it too much to ask, just once, that Congress get ahead of this mess before all of those newly-purchased copies of 1984 turn into tour guides? The leaders of many top Silicon Valley companies have besmirched the reputations of their companies (“Do no evil” indeed) and lost the hard-earned trust of their international customers in the last few days – for what? Haul them in before a Senate committee and find out what threats the NSA and other agencies made to make these powerful billionaires give up so much.

Meanwhile, Congress, get ahead of the technology curve for once. You can start by asking about where the data goes from cellphone cameras. Then talk to the GPS folks about the ability to track the location of private phones and use their phone and tablet cameras. Query Google about the future plans for those autonomous camera cars. Get Bill Gates and ask him about what he had to give up to quiet that Microsoft anti-trust case of a decade ago. All may prove dead-ends, but who can now be sure?

Finally, if you really want nightmares, go talk to Intel and the semiconductor industry: there was a lot of discussion twenty years ago about how easy it would be to hide a subroutine in one of those incredibly complex and intricate new microprocessors that would give a remote user access or even control. There are more than 30 billion out there, in every office, home, automobile . . .and weapons system. Anybody check chips lately?

As for me, I’ve decided to keep that black tape on my computer camera.

Related on Forbes:

see photos

see photosClick for full photo gallery: The NSA’s Slideshow Explaining Its PRISM Surveillance Program

June 5, 2013

Silicon Valley’s Newest Address? Look East

It is just before 5 pm on a hazy Tuesday at the Diridon transit station in downtown San Jose. The ACE commuter train hums and rumbles as it waits in its bay. Overhead, men and women are making their way, not yet hurried, through the old WPA-built deco station lobby and down the long ramps, each stopping to punch their transit pass into a machine.

Some are in business suits, others in bicycle gear, but most are dressed in that formal-casual look of people who work in the hundreds of glass towers and office parks of Silicon Valley. They have arrived by bus, the local light rail system, bikes, and some even in cars – and most are carrying shoulder bags or cases that betray laptops and iPads inside. A few are still on their smartphones, continuing their work day. They stream onto the train’s five cars, selecting the one that suits them best: two for regular commuters, one with bicycle racks, and two at the front equipped with desk-like set-ups that offer lighting and wireless connections.

At almost 5pm on the dot, the doors on the cars close and the train makes its way out of the station. It heads north, skirting out through the older districts of the city, then turns west through the cities of the East Bay. Then, climbing into the brown hills, the train heads up through Niles Canyon, where Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton filmed in the original Hollywood.

The jaded commuters have seen all of this many times before, and before long they have pulled out their electronic tools and gone back to work. It is an hour to Tracy, and though these distracted riders don’t look the part, they are in fact California’s latest generation of pioneers – and in their commute may lie the future of Silicon Valley.

*

Over the last half-century, Silicon Valley has become legendary for its ability to overcome one technological obstacle after another, often against seemingly impossible odds. But now the Valley’s very success has presented it with a geographical obstacle that won’t be overcome so quickly.

Electrons can circle the world on the Internet in a fraction of a second, but commuters trying to get to their jobs at Internet companies in the Valley aren’t so lucky. One reason is that the combination of high wealth and a limited number of available homes has skyrocketed local real estate prices to among the highest in the nation. The last under-one million dollar house in Palo Alto sold a decade ago. Now comparably inflated prices can be found across the Valley, and not just in the hills, but on the Valley floor from Redwood City to San Jose.

Just as important is the topography of the Valley and the surrounding San Francisco Bay Area, which essentially sit in a seam between the Coastal and Diablo ranges of mountains. Thirty years ago, when the Valley still contained the last orchards and farmland stretched to the south, this wasn’t a big concern. But now the Valley is not only out of space, but so increasingly are its traditional safety valves in the South Valley and the East Bay.

So where does the Valley grow next? The answer isn’t easy anymore. North? Unfortunately, the Peninsula gets narrower as one heads in that direction. And then there’s the great roadblock of San Francisco itself: expensive, and already the home of more than a thousand new start-up tech companies over the last decade. And, beyond the bottleneck of the Golden Gate Bridge, lies even more expensive Marin County.

West? Once you drive curvy and scary Highway 9, the only real road over the Coastal Range, you discover that Santa Cruz and the Pacific side is even narrower than the Bay. South? Southwest takes you over a long passage in the mountains to Monterey and Salinas. Southeast? Over the dangerous Pacheco pass, past the endless San Luis reservoir and out into the hot and unappealing Central Valley. Either way, it is a two hour commute.

That leaves East. But the East Bay cities are already full of tech companies and increasingly expensive homes. Out of desperation to cut costs and find an affordable space, a growing number of companies have even begun to set up shop in crime-ridden Oakland. Meanwhile, Berkeley is crowded and expensive.

That leaves the eastern hills of the Diablo range, presided over by might Mt. Diablo itself. The first valley inland from the Bay, which contains Contra Costa County, has already had its Silicon Valley growth boom, fueled in large part by the dot.com bubble of the Nineties. To sit in gridlock on the 680 Freeway at 7 a.m. and see ahead of you four lanes of cars heading south to the horizon and the Valley is to quickly understand why tech workers are now looking even farther out.

The pathway out to that new territory is the 580 freeway, which branches off 680 near Livermore and heads up and over windswept, windmill-dotted (and rock music notorious) Altamont pass, or the ACE train as it emerges from Niles Canyon, crosses the Contra Costa corridor then climbs those same hills through Patterson pass. Both drop out of the burned-brown mountains into the town of Tracy.

This is San Joaquin County, long known as a major agricultural region in California’s great Central Valley. Most Bay Area folks, if they’ve noticed the county at all, remember it only as part of the long stretch of farmland they had to drive across on their way to Tahoe and the Sierras. Most recently, the county’s biggest city, Stockton gained national attention both for a rising crime rate and for political mismanagement – it became the largest city in the U.S. in recent memory to go bankrupt. So great was the fall-out – jokes, editorials and international reporting – from that event that the Mayor, in a sad attempt at levity, showed up for his most recent State of the City address wearing an old-fashioned suit of armor.

The reality is that, after the reporters and news crews moved on, Stockton has pulled off a remarkable turnaround, reducing its crime rate and asserting a new financial discipline – to the point, writes the regional newspaper, The Record, that it has become “the poster child” for other U.S. cities trying to turn around their fortunes. But it may be years before the scandal fades and anyone notices.

*

But Tracy, San Joaquin’s closest city to Silicon Valley, is a different story. Most long-time Bay Area residents, when they think of Tracy remember a sleepy rural burg with a bar, a hotel and a couple burger joints they stopped at on the way home from the mountains – mostly because Highway 50, the road to South Shore Tahoe and the ski resorts, in those days went right through the center of town.

In fact, Tracy’s redevelopment has been almost as sweeping as Stockton’s, but without all of the financial drama. These days, there’s a new city center far from the distant freeway, with a spanking new city hall, police station, library and park. The downtown is also undergoing a transformation, most notably an entire block that included an old movie palace has now been cleverly amalgamized into cultural complex that includes the area’s largest stage, dance studios, art galleries and other arts amenities. Over by the train station another old retail block has been turned into a series of restaurants and boutiques that look like a tiny piece of Palo Alto or Los Gatos.

None of this has been spontaneous. For almost a decade now, Tracy has been looking west, over the mountains, to the excitement and wealth of Silicon Valley – and positioning itself to become the next city to join the Silicon Valley community. And if the city is patient — “We have a thirty year plan,” says city manager R. Leon Churchill Jr., “and we intend to execute it” – it is also, in the Valley spirit, anxious to get there.

“Silicon Valley is a rocket ship and we want to be aboard — not just watching from the distance like a perpetual bystander,” says Mike Ammann, president/CEO of the San Joaquin Partnership, a public-private regional development group.

May 9, 2013

Testing California’s Commitment to Education

Just a generation ago, California’s schools were the pride of American education (it’s one of the reasons my parents moved with me to California in the early 1960s). Today, tracking with the economic woes of the rest of the Golden State, California’s schools rank 30th in the country . . .and falling.

Now it could get much worse – and quickly –as one of the few bright spots of California public education is at risk of disappearing. The implications to the state’s high education enclaves, such as Silicon Valley, are frightening. But for California’s low-income, high-unemployment regions in places like the Central Valley and the state’s urban centers, the impact could be devastating. Indeed, what lingering hope there is that California can recover its old luster in less than a generation may evaporate as well.

The program is called the International Baccalaureate. If you haven’t heard of it it’s probably because the program has done a far better job at helping elementary and high school students than it has at promoting itself or its confusing name. In retrospect, it probably should have spent more time on the latter, because now as California cuts its educational budget the program – at least its California operation of more than 200 schools across the state – is facing a dangerous shortfall of its $2.5 million annual budget.

International Baccalaureate is actually a huge operation. Founded in 1968, IB is (as its name suggests) a global program, well-established in nearly 150 countries, serving more than a million students. Everywhere the goal is the same: to take young students from every economic level and bring them to the highest levels of analytical thinking in order to prepare them for college and a successful career This has been true for IB students in Botswana and Bangladesh, in Canada and – at least until now, in California.

The International Baccalaureate program is not a high school Advanced Placement (AP). In one respect it is even more extensive and demanding: AP classes are typically in one subject, targeted at only the best high school students, and designed to produce maximum results on a single year-end SAT test. By comparison, many of California’s IB programs begin in elementary school, include all types of students for every imaginable background (half operate in disadvantaged areas), and continuously measure achievement throughout the year. Indeed, many students actually take AP tests in preparation for their IB exams.

Not surprisingly, IB students, even in low-income areas, have college acceptance rates – and more important, college graduation rates – greater than even their AP counterparts.

How does IB do it? A lot of it is just the application of proven, traditional teaching techniques to 21st century subjects, with a strong emphasis on critical thinking, STEM and the ability to communicate ideas well. It is also the training of teachers to not just convey this knowledge, but to do so in a way that promotes student enthusiasm, pride and commitment. Finally, it is that increasingly taboo idea, testing – continuously, incisively and in comparison the very best students in the world.

In an age of perpetual pedagogical experimentation, an emphasis on social relevance rather than enduring truths, and a fear of holding students to the highest standards, the International Baccalaureate program is a throwback . . .delivered through the latest technology. And it works. Kristine Bohnhoff, now a sophomore at Drexel University in Philadelphia and a graduate of the IB program at Andrew Hill High School in San Jose, in an Opinion piece in the San Jose Mercury-News wrote: “Many of my peers took advanced placement courses, and yet they found the workload and assignments in college overwhelming. I often heard, ‘I didn’t learn how to do this in high school,’ ‘This is so hard,’ and ‘I have so much work.’ Yet I found my freshman year easier than getting my IB diploma, even with a full credit load, three minors, volunteering on the side and Russian class at night.”

IB’s own research of more than 1,500 of its students that subsequently enrolled in the University of California system found that they enjoyed both a higher grade point average and a greater graduation rate than their fellow UC classmates. Better yet, that advantage reached across all income groups. What this means for the state’s future is that IB does a better job of preparing college graduates for future success – in business, the professions, even in education . . .ultimately, in restoring California to civic and economic health – than any other public school program.

The awful tragedy of International Baccalaureate may be that, having somehow survived the gauntlet of the state’s teachers unions, government bureaucrats, trendy educational theories and devastating business cycles, its California program may now find itself suffocated by the indifference of the state itself.

At a time when the quality of the Golden State’s once-legendary schools is now in free-fall. When anxious parents are pulling their children out of public schools and putting them in private programs or home-schooling – abandoning the children of poorer families to their fates. And when California’s last hope of renewal lies with those high-skill industries – technology, aerospace, banking, entertainment – that are in desperate need of home-grown young talent to remain competitive; it seems almost insanely self-defeating for Sacramento to kill off the one program that is envied by even the best of these private educational alternatives.

If California can’t find a way to keep alive a program as proven and successful for its future as the International Baccalaurate, what does that say about the future of the state itself?

March 28, 2013

Why Your Kid Can’t Get a Job

This article was co-authored by veteran Silicon Valley marketing executive Tom Hayes, currently founder and CEO of MePedia.com

According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, one out of every two Millennials—age 18 to 32–is either unemployed or under-employed. Numbering approximately 80 million people (there are actually more Millennials than Baby Boomers), this cohort is now the most educated, yet most-indebted generation in history. The Department of Labor estimates that some three million Americans with Bachelor degrees work in jobs that don’t require an education at all–janitors, barristas, bartenders and retail clerks.There are a lot of obvious reasons why junior is now living in your basement at age 25.

Indeed, there has been almost a perfect storm in the convergence of Globalization and the off-shoring of labor, productivity gains from information technology, the Great Recession (and the evaporation of millions of entry-level jobs), and the rise of impersonal “robo-hiring” via computer modeling and software filtering (where test scores and checked boxes count more than life experience).

Meanwhile, the confluence of social, mobile and local is seeping into the corporate world. In fact, our very idea of an ‘enterprise’ is changing. Empowering individuals weakens organizations – and thus companies are becoming decentralized, virtual, protean. Managers can look to services like Odesk and eLance to contract out virtually any task. The very nature of work and the compact between worker and workplace is changing – and society is slowly adapting to this change. It no longer makes sense to warehouse employees (even at Yahoo!) in expensive office buildings so that colleagues can spend the day texting and emailing each other anyway.

Unfortunately, the world of work isn’t adapting quickly enough for Millennials. At a time when one’s gifts are just as likely to appear in a YouTube video or pin board as in a resume, the talents of this generation are being overlooked by aging HR directors and recruiters. There’s a reason that the average LinkedIn user is 44 years old – how do you display in a line of bare text your genius at viral marketing?

So what is a kid today to do? One answer is to establish a powerful personal brand independent of work experience. Not just cobble together a few starter jobs, but pursue their own aspirations – and then learn how to define them and market them to the corporate world. Another answer is to take advantage of being a digital natives and build new kinds of networks – and a sharing economy – and find jobs for each other and hire amongst themselves. Freelancing is likely to be their future anyhow, so why not start and learn the skills (from DIY bookkeeping to marketing) of being an entrepreneur now?Young job hunters need to rethink their social media presence. Social proof is critical to employers. Ditch the frat party photos, avoid the drunken tweets. Turn your public social media presence into a showcase of your personal brand and portal of interests and skills. Connect the dots for the prospective hiring manager. The best way to combat a thin resume is with photos, video, endorsements. Be unusual and memorable: if, for example, you reached Level 60 on World of Warcraft, tell your future boss why that means you have monster leadership skills. And, show you have a big and growing network that comes with you when you get hired.

Meanwhile, whether you’ve graduated from college or never went at all, never stop learning. The Web is filled with on-line courses from Udemy to the Ivy League. And, don’t go into major debt chasing that BA: there is a growing “uncollege” movement that aims to unseat the four-year baccalaureate BA as the key measure of smarts. Expect colleges to respond with shorter degree programs and employers to start looking for better ways to evaluate talent.

At the same time, employers need to start rethinking their recruiting process, notably in using sophisticated social network search tools to go spear-fishing for high potential talent, rather than waiting for applications to come across the transom. And, managers need to look for the skills that really matter today in high potential young talent, attributes like cognitive load capacity, adaptability and social media skills. That one kid with the high GPA and stellar SAT scores may just be a drudge who took a lot of prep classes –while that other kid making clever and obscene videos may have superior communications and social networking skills, a huge online following and an innate ability to redesign your company’s entire future. Employers need to start looking for these new skills, and stop hiring in the rear-view mirror. They need to find raw, adaptable, resilient people who can be molded and mentored for jobs that don’t even have titles yet. And no group is better suited for than the Millennial who made your latte this morning . . .or still lives in his old bedroom down the hall.

Michael S. Malone's Blog

- Michael S. Malone's profile

- 63 followers