Tracy Patrick's Blog: Paisley Patter by Tracy Patrick

January 6, 2021

The World of Yesterday

The World of Yesterday by Stefan Zweig

The World of Yesterday by Stefan ZweigMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

On 22 February 1942, Stefan Zweig posted the manuscript for The World of Yesterday to New York. The following day, he and his new wife committed suicide in Brazil. If you are looking for details on Zweig’s rather interesting personal relationships, you will not find them here. This is a memoir of what it was like to come of age in Austria-Hungary during the dying days of the Habsburg empire. It is an account of Europe during one of the most revolutionary periods in human history, and of how Zweig’s idealistic vision of European intellectual unity was torn apart by the worst conflicts the world has ever seen. His ability to deliver sharp and poignant imagery, together with his remarkable personal acquaintances with many of the greatest artists and thinkers of the time, makes for an illuminating account that brings this era to life like no historical document can. It is also the tragic tale of a man whose world is torn apart by forces beyond his control.

There are personal reasons why I sought out Zweig. I am part Austrian myself and the cathedrals of Graz with their Baroque towers, sumptuous frescoes, and gilded altars are indelibly etched in my memory. My grandmother enthused over Vienna opera house and the Schönbrunn Palace. When I listen to Mahler it evokes images of sunlight and shadow over the mountains and deep lakes of Carinthia. I once travelled on the Istanbul Express from Munich to Salzburg. I visited the Eagle’s Nest, all that is left of Hitler’s Berchtesgaden with its dark and eerie tunnels, and which was visible to Zweig from his home on the Austrian side of the border. The World of Yesterday is the Europe in which my family grew up, and I wanted to find out more.

Zweig was the son of a wealthy Viennese industrialist. At the turn of the century, the Habsburg dynasty was a familiar but stagnating fixture of Austrian life, like the stuffy gymnasium for boys where Zweig received his education. He did not find his enthusiasm for literature there, but in Vienna’s youthful café culture, where intellectuals of all backgrounds came together in pursuit of literature, music and philosophy, and where Zweig developed an enthusiasm for radical new poetry, composing his own verse as zealously as later generations would form punk bands. It is also the start of his lifelong passion for collecting and his rather homo-erotic idol worshipping (he becomes the proud possessor of Goethe's quill pen and a lock of Beethoven's hair) which he refers to in quasi-religious terms as a reverence 'for every earthly manifestation of genius.' Look out for the moment where he discovers his elderly neighbour was a friend of Goethe’s granddaughter!

Zweig is extraordinarily sensitive and dislikes any form of authoritarianism and repression. At university, he finds the elite student guilds who still exercise their medieval privileges to wear ribbons and duel with impunity, ridiculously boorish. They inspire a need for isolation that will follow him throughout his life. As a young man, he immerses himself in the artistic society of Berlin where he enjoys the company of ‘heavy drinkers, homosexuals, morphine addicts, aristocrats and swindlers.’ His work as a translator opens the gateway to Brussels and Paris where he rapidly encounters figures of mythical status. In one chapter, he is invited to dinner by Rodin, accompanying him to his studio where he watches the artist lose himself in his latest sculpture. The next, he is in London, at a poetry reading by Yeats who is mysteriously clothed in black and surrounded by altar candles. These cultural connections fill Zweig with enthusiasm for a Europe brimming with new philosophies, scientific discoveries, artistic and socialist ideals. This is the lost (albeit very male) world that Zweig mourns. I was reminded of Albert Khan’s photographic images of ethnic European communities living side by side before they were destroyed by powers larger than themselves. Yet it is one image of Rilke, with whom Zweig was friends, that uncannily hints at the destruction to come: ‘It was impossible to think of Rilke as being noisy […] I can still see him before me in conversation with a high aristocrat, completely bent over, his shoulders tortured and even his eyes cast down so that they might not betray how much he suffered physically from the gentleman’s unpleasant falsetto.’

Zweig can bring an historical turning point to life in a single startling visual. At the outbreak of the First World War, he is leaving Belgium on the Orient Express, when he sees ghostly freight trains going in the opposite direction, carrying the outlines of canons. Alienated by Europe's patriotic hysteria, he becomes aware that the era's exuberant energy and progress has a shadow side, a nationalistic competitiveness, each country with an arrogant belief in its own invincibility. While around him people voice support for the war, Zweig loses ‘all hope of reasonable conversation’ and is pushed towards spiritual and intellectual isolation. He accepts a post in the Vienna War Archive, which he considers preferable to ‘pushing a bayonet into the entrails of a Russian peasant.’

His anti-war drama, Jeremiah, is premiered in Zurich in 1917, when he is given permission to leave with his superior's words, ‘You were never one of those stupid warmongers […] Well, do your best abroad to bring the thing to an end.’ Switzerland has become a home for pacifists, and Zweig’s description of the café conspirator society with its communist revolutionaries and lurking secret agents is intriguing. But eventually he finds the conspiratorial atmosphere impotent and is once again desperate for solitude. Look out in this section for a ‘rather testy’ James Joyce.

Zweig defines the end of the war with another train journey. He is at Feldkirch station in Austria when he witnesses Emperor Karl and Empress Zita, the last of the Austro-Hungarian rulers, passing through the station and into exile in Switzerland. So ends the almost millennian Habsburg dynasty. Zweig returns to a new republic where half-starved soldiers wander like scarecrows, and bread tastes like ‘pitch and glue.’ Post-war Austria is a horrifying world of poverty and strange absurdities. Those who invested in war bonds become beggars, while impoverished peasants become the owners of rococo bookcases. The postage Zweig pays on a manuscript turns out to be worth more than his advance. Anyone skilled in bribery and deception advances, while those who obey government advice, fall back and starve. The overriding feeling is of betrayal, a generation cheated by their elders, by the institutions and traditions in which they had faith. Gone is the naivety that saw soldiers 'sing their way to slaughter.' A new sense of distrust emerges.

In the inter-war period, Zweig really makes his name as an author, marred by (according to his wife’s biography) bouts of depression. He begins to travel in a new uncertain world. In Venice, he witnesses his first fascist gathering. In Russia, he finds the atmosphere unsettling; the anonymous note thrust in his pocket, with its ominous warning ‘we are all being watched’ has the intrigue of a novel. On a visit to Germany, he witnesses the Nazi brown-shirts ambush a Social Democrat gathering, and notes the new uniforms and equipment, compared to the tattered clothes of ‘real veterans.’ Zweig speculates on the mysterious financial interests, the militarists, industrialists and capitalists, behind this new movement.

It is well known that Zweig had the personal pleasure of pissing off Hitler when Richard Strauss refused to erase Zweig’s name from their operatic debut, The Silent Woman. His personal account of this incident is fascinating. Zweig's play, The Burning Secret, was already being used as a covert public reference to Nazi involvement in the burning of the Reichstag, when Strauss put Hitler in the position of letting the opera debut or losing Strauss's prestige as President of the Nazi Chamber of Music. Senior Nazi officials were in an uproar. In the end, the opera saw two performances: a small victory over which Strauss was eventually forced to resign, but satisfying nonetheless.

A turning point for Zweig came in 1934 when he was subjected to a house search. The situation was becoming dangerous, with Nazi cells in Austria carrying out intimidation of police and civil servants. As the Austrian government treads a dangerous line between communism and fascism, desperately trying not to give Hitler an excuse to march in, Zweig is pessimistic: ‘I had written too much history not to know that the great masses always and at once respond to the force of gravity in the direction of the powers that be. I knew that the same voices which yelled ‘Heil Schuschnigg today, would thunder Heil Hitler tomorrow.’ He spends more time abroad, but confronted with fascism in Spain, and even having to endure one of Hitler’s speeches over the lonely prairies of Texas after a fellow train passenger turns the radio on, it seems to Zweig that the whole world is falling into the abyss with their eyes shut.

For a man already traumatised by the First World War, the prospect is unbearable. His warnings fall on deaf ears as people refuse to believe the worst, 'little knowing they will soon be in concentration camps.' After the Anschluss, he departs his homeland for the last time. One cannot sense deeply enough his personal tragedy. To go from an idealistic young man with dreams of European unity, to witnessing his beloved Vienna become a place where his aging mother is forbidden to sit on a public bench, where Jews are excluded from libraries, theatres, and civic buildings, where professors are forced to scrub the streets with their bare hands; laws that have no other purpose than to wilfully deprive a person of their humanity, must have been a brutal offence to such an extraordinarily sensitive soul.

His pessimism is tragic, but understandable. He moves to London as a refugee. His description of the loss of dignity and self-confidence that accompanies this status is something that merits more open discussion today. Zweig finds himself part of a persecuted population that has no common identity besides their faith, made up of the haves and have nots, the Zionists and the assimilated, the Nobel Prize winners and the cabbies, speakers of different languages and countries ‘heaped together into one confused hoard, held blameful without any specific aim or opportunity for extirpation.’ Finding it impossible to articulate his experiences, he withdraws into himself.

Consolation comes when his old friend, Sigmund Freud, arrives in London, also in exile: ‘at the moment of entering his room it was as if the madness of the world outside had been shut off.’ There is a wonderful moment when Zweig takes Salvador Dali to visit Freud. Dali sketches while they talk, but as he had incorporated the figure of death into the sketch, Zweig dares not show Freud, who is in the last stages of his illness. After he dies, Zweig is alienated again.

When war finally breaks out, he is in Bath, about to marry his second wife. The ceremony is interrupted by an official and, in an instant, Zweig goes from refugee to enemy alien: ‘I suddenly noticed before me my own shadow […] during all this time it has never budged from me […] it hovers over every thought of mine […] perhaps its dark outline lies on some pages of this book […] but after all, shadows themselves are born of light.’

If there is a lesson to be learned from The World of Yesterday it is in Zweig's perspicacity about the world that is to come. It is remarkable to read that it was once possible to sail the globe without passport, border controls, Visas, humiliating searches, and endless form filling. In Zweig's eyes, the absurd bureaucracies into which we have descended are erosions of freedom with which we have become unthinkingly compliant. He is all too aware of this piecemeal eradication of human dignity and it plummets him into despair. It is, perhaps, a mercy that he did not live to see the horrors of the Holocaust. All too often the most reasonable, insightful and compassionate voices are those that are silenced. The World of Yesterday is not only a prescient account of some of the most significant historical events in human history, but it is a fight against the injustice of being forced into submission, an insight into what it is to dream, and to wake up from a nightmare, only to find that the waking up is a nightmare in itself. Ours is a story of light and shadow, and The World of Yesterday has both in abundance.

View all my reviews

Published on January 06, 2021 08:55

April 27, 2020

Social Media and Stalking

It was National Stalking Awareness Week on April 20-24th, and this year social media has been given special emphasis due to the Coronavirus lockdown. I started to think about what this means. For many years, I'd used a pseudonym on social media to avoid ex-partners I no longer wanted contact with. I did this at the time without questioning what it says about power relationships in the digital world.

Here I was, adapting my behaviour to accommodate individuals who I knew would peek their heads around the door, despite it having been closed in no uncertain terms. In the main part I was protecting my emotional and physical health from controlling and unreasonable behaviour. Believe me, if I told you the stories you would understand. But something about it jarred. When people asked me about the pseudonym, I felt that it was better to sidestep the question, as I did not want to divulge the details of uncomfortable past experiences, fearful that I would be blamed or criticised for my bad choices.

I was not far wrong. There is a lack of understanding in society as to why, women in particular, stay in relationships that are mentally, or even physically, abusive. When I was struggling to free myself from a toxic relationship, a psychologist I was seeing questioned why I didn't just move on, without acknowledging that moving on is just what the toxic person is trying to prevent you from doing.

It is one thing reading the literature, and another thing experiencing how such situations play on your emotions, as the person you trusted questions your perceptions, manipulates your feelings, and even deliberately sets out to ruin your best moments. On the other hand, they are very good at elevating you when it suits them. Too good to be true, in fact. If it sounds confusing, that's because it is. When you try to extricate yourself from the situation, you will no doubt be met with such phrases as: 'I'm worried about you,' and 'You've got it all wrong.'

Relationships are made up of plans, dreams, hopes, all of which can be hard to let go of. The toxic wheel of acceptance and rejection can go on for a long time. Blocking. Unblocking. Letters. Texts. Random visits. In its most unhealthy aspects, social media encourages voyeurism, a way of finding out where a person goes, and what they are up to. Most getting-over-your-ex advice will warn against the temptations of this. For most of us, it's just the lingering effects of a broken heart. For others, it's a way to regain control. In other words, stalking.

So far I've been non-gender specific, but Stalking Awareness Week is promoted by Women's Aid, so to ignore gender imbalance would be to ignore a large part of the problem. In the bog standard hetero rom-com, women are invited to believe that if a guy repeatedly leaves messages, turns up unannounced at her gym class, chases her through an airport, or even breaks into her house, it’s because he's the best thing since the Wonderbra and all she has to do is admit it and they'll live happily ever after. The message women are given is to hand over your power, because the guy knows you better than you know yourself? Really?

Perhaps the psychologist had a point to make about coming to terms with choices that haven't worked out (part of the healing process), although he didn't quite put it like that. But I saw it in gender terms: the onus was on me to change my behaviour, and not on the other party to respect my boundaries. This is so often the story. But it shouldn't be. The more we talk about these issues, the easier it will be to for anyone who finds themselves in that position to recognise what it is happening to them, without taking on feelings of shame and blame. Let the abusers hide, and not the victims.

Here I was, adapting my behaviour to accommodate individuals who I knew would peek their heads around the door, despite it having been closed in no uncertain terms. In the main part I was protecting my emotional and physical health from controlling and unreasonable behaviour. Believe me, if I told you the stories you would understand. But something about it jarred. When people asked me about the pseudonym, I felt that it was better to sidestep the question, as I did not want to divulge the details of uncomfortable past experiences, fearful that I would be blamed or criticised for my bad choices.

I was not far wrong. There is a lack of understanding in society as to why, women in particular, stay in relationships that are mentally, or even physically, abusive. When I was struggling to free myself from a toxic relationship, a psychologist I was seeing questioned why I didn't just move on, without acknowledging that moving on is just what the toxic person is trying to prevent you from doing.

It is one thing reading the literature, and another thing experiencing how such situations play on your emotions, as the person you trusted questions your perceptions, manipulates your feelings, and even deliberately sets out to ruin your best moments. On the other hand, they are very good at elevating you when it suits them. Too good to be true, in fact. If it sounds confusing, that's because it is. When you try to extricate yourself from the situation, you will no doubt be met with such phrases as: 'I'm worried about you,' and 'You've got it all wrong.'

Relationships are made up of plans, dreams, hopes, all of which can be hard to let go of. The toxic wheel of acceptance and rejection can go on for a long time. Blocking. Unblocking. Letters. Texts. Random visits. In its most unhealthy aspects, social media encourages voyeurism, a way of finding out where a person goes, and what they are up to. Most getting-over-your-ex advice will warn against the temptations of this. For most of us, it's just the lingering effects of a broken heart. For others, it's a way to regain control. In other words, stalking.

So far I've been non-gender specific, but Stalking Awareness Week is promoted by Women's Aid, so to ignore gender imbalance would be to ignore a large part of the problem. In the bog standard hetero rom-com, women are invited to believe that if a guy repeatedly leaves messages, turns up unannounced at her gym class, chases her through an airport, or even breaks into her house, it’s because he's the best thing since the Wonderbra and all she has to do is admit it and they'll live happily ever after. The message women are given is to hand over your power, because the guy knows you better than you know yourself? Really?

Perhaps the psychologist had a point to make about coming to terms with choices that haven't worked out (part of the healing process), although he didn't quite put it like that. But I saw it in gender terms: the onus was on me to change my behaviour, and not on the other party to respect my boundaries. This is so often the story. But it shouldn't be. The more we talk about these issues, the easier it will be to for anyone who finds themselves in that position to recognise what it is happening to them, without taking on feelings of shame and blame. Let the abusers hide, and not the victims.

Published on April 27, 2020 05:09

February 19, 2020

A Radical Renaissance Paisley Book Festival 2020

You only have to look at the Literature Alliance Scotland website to see how alive the book festival scene is in Scotland. This year, Paisley has added its name to the burgeoning list by hosting its first ever book festival, which gives a bit a bit of an intellectual twist to the less savoury aspects of the town’s reputation by adopting the theme of radicalism and rebellion.

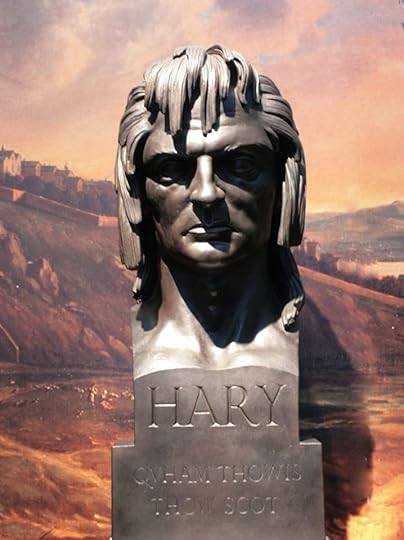

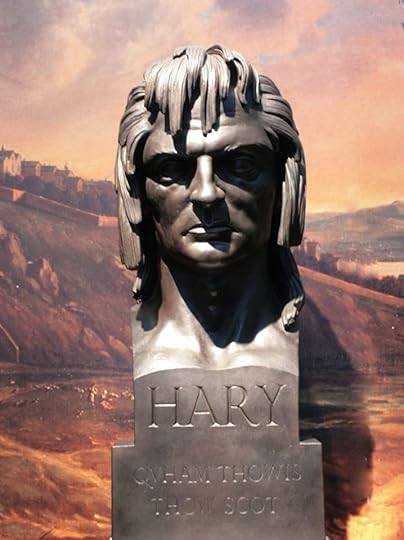

The story of one particular rebellious Scot formed part of the fabric of my childhood, having grown up in Elderslie, famed as birthplace of Sir William Wallace. What I didn’t know at the time was that the story of Wallace was handed down through literature by travelling bard, Blind Harry, whose poem ‘The Wallace’ has been described as being worthy of Homer, and who was noted by many of Scotland’s finest poets, including William Dunbar and Robert Burns. In terms of Blind Harry’s significance to our national culture, I think the comparison is justified. It might also be said that in present-day Scotland, the connection between rebellion and literature is stronger than ever, and Paisley Book Festival has decided it is worthy of celebration.

Paisley has a tradition of radical writers, most notably the weaver poets, influenced by Romanticism and the ideals of liberty, equality and justice that sparked the French and American Revolutions. During this time, the poet Alexander Wilson’s (1776-1813) open criticism of mill owners and their treatment of workers landed him in prison. Rather than face the possibility of sedition charges, he emigrated to America where his studies on birds earned him the reputation of the father of American ornithology. During the same time, Robert Tannahill’s (1774-1810) musical drama, The Soldier’s Return, idealised love and humanity over enforced conscription and the horrors of war, and his romantic pastoral poems are a testament to Renfrewshire’s natural heritage and the importance of conservation and well-being. Marion Bernstein wrote no-holds-barred poems on marriage, domestic abuse and women’s right to vote, and, John Galt (1779-1839), from neighbouring Greenock, is often considered the first political novelist in the English language for his writing on the effects of industrialisation and urbanisation on society.

Paisley Book Festival marks the bicentenary of the Radical Wars in Scotland when, in the spring of 1820, the country seemed on the brink of armed rebellion. Indeed, soldiers found men in Kilbarchan making homemade pikes, though, after a week of rioting, Paisley was under strict curfew to ensure no further rebellions took place. Wishful thinking when we take into account the subsequent Sma Shot protests of 1856, still celebrated annually by the town on 1 July, and the mill riots of 1907 when thousands of mill workers took to the streets protesting poor pay and conditions. Many of the mill girls were known big toe typists because they operated the twisting machines with their big toes, resulting in swelling and often amputation. Mill girl, Jean, in my novel, Blushing is for Sinners, recalls her grandmother being one of these women and showing her the purplish stumps.

By taking rebel voices as its theme, Paisley’s book festival is proudly announcing that the tradition of rebellious writing is not confined to the past. Paisley Writers’ Group, which used to meet in Paisley library, and which I joined twenty years ago as a fresh-faced new writer, has a strong connection with literary radicalism in both language and subject matter. Its first writer-in-residence was none other than the late Tom Leonard, whose poetry transformed the relationship between language, class and culture. His book, Radical Renfrew, anthologises much neglected dissenting voices in Renfrewshire literature from the French Revolution to the First World War. The list of luminaries goes on to include James Kelman, Suhayl Saadi, Ajay Close, Graham Fulton, Louise Turner and Dr Jim Ferguson, to name but a few whose work contributes to our understanding of the impact of significant developments in social history including Thatcherism, multiculturalism, feminism, the Suffragette movement, the American Civil War, and Medieval Renfrewshire, all of which has its fair share of – you guessed it – rebels.

Today, there is definitely a strong relationship between radicalism, activism and the arts. I’m often asked to write for organisations seeking to transform attitudes on issues ranging from mental health, addiction and recovery, refugees and modern slavery. Radical writers need original and creative ways of getting their work out there, and often these connections are driven by passion and the creative impulse to make a difference. For twelve years, I ran an eco-poetry quarterly from my front room, receiving contributions from around the world, and donating all the proceeds to conservation charity. The magazine collaborated with Paisley Hill Walking club in a sponsored poetry fundraiser, and Edwin Morgan was even so kind as to contribute an unpublished poem. Today, I am involved with Jenny’s Well Press, Paisley’s only indie publisher, run on a voluntary basis by a team of dedicated writers and editors. Indies often have to come up with radical ways of doing things, and this can lead to innovative alliances in the creation and distribution of books, for example, with charities and socially and environmentally conscious retail outlets. Every copy of my novel sold in Shelter helps fight homelessness.

Radicalism is defined as beliefs or actions that advocate complete political or social reform, and Paisley Book Festival is celebrating the tradition of rebellion by hosting literary events that recognise where contemporary change is taking place, including disabled and low income access to publishing, stories of rebel women, queer identities, the #MeToo movement and BAME writing. It features contributions from some of contemporary literature’s most radical voices like Jenni Fagan, Jackie Kay, Alan Bissett, Chris McQueer, and Mara Menzies, as well as exploring fictional rebels and Tom Leonard’s Radical Renfrew thirty years on. So, switch aff yer Netflix, and find yer inner rebel at Paisley’s Book Festival. They may take our lives, but they’ll never take our freedom, or our books!

Paisley Book Festival

20-29 February 2020

https://paisleybookfest.com/events/

Photo: Tricia Hutchison, Blind Harry by Alexander Stoddart.

The story of one particular rebellious Scot formed part of the fabric of my childhood, having grown up in Elderslie, famed as birthplace of Sir William Wallace. What I didn’t know at the time was that the story of Wallace was handed down through literature by travelling bard, Blind Harry, whose poem ‘The Wallace’ has been described as being worthy of Homer, and who was noted by many of Scotland’s finest poets, including William Dunbar and Robert Burns. In terms of Blind Harry’s significance to our national culture, I think the comparison is justified. It might also be said that in present-day Scotland, the connection between rebellion and literature is stronger than ever, and Paisley Book Festival has decided it is worthy of celebration.

Paisley has a tradition of radical writers, most notably the weaver poets, influenced by Romanticism and the ideals of liberty, equality and justice that sparked the French and American Revolutions. During this time, the poet Alexander Wilson’s (1776-1813) open criticism of mill owners and their treatment of workers landed him in prison. Rather than face the possibility of sedition charges, he emigrated to America where his studies on birds earned him the reputation of the father of American ornithology. During the same time, Robert Tannahill’s (1774-1810) musical drama, The Soldier’s Return, idealised love and humanity over enforced conscription and the horrors of war, and his romantic pastoral poems are a testament to Renfrewshire’s natural heritage and the importance of conservation and well-being. Marion Bernstein wrote no-holds-barred poems on marriage, domestic abuse and women’s right to vote, and, John Galt (1779-1839), from neighbouring Greenock, is often considered the first political novelist in the English language for his writing on the effects of industrialisation and urbanisation on society.

Paisley Book Festival marks the bicentenary of the Radical Wars in Scotland when, in the spring of 1820, the country seemed on the brink of armed rebellion. Indeed, soldiers found men in Kilbarchan making homemade pikes, though, after a week of rioting, Paisley was under strict curfew to ensure no further rebellions took place. Wishful thinking when we take into account the subsequent Sma Shot protests of 1856, still celebrated annually by the town on 1 July, and the mill riots of 1907 when thousands of mill workers took to the streets protesting poor pay and conditions. Many of the mill girls were known big toe typists because they operated the twisting machines with their big toes, resulting in swelling and often amputation. Mill girl, Jean, in my novel, Blushing is for Sinners, recalls her grandmother being one of these women and showing her the purplish stumps.

By taking rebel voices as its theme, Paisley’s book festival is proudly announcing that the tradition of rebellious writing is not confined to the past. Paisley Writers’ Group, which used to meet in Paisley library, and which I joined twenty years ago as a fresh-faced new writer, has a strong connection with literary radicalism in both language and subject matter. Its first writer-in-residence was none other than the late Tom Leonard, whose poetry transformed the relationship between language, class and culture. His book, Radical Renfrew, anthologises much neglected dissenting voices in Renfrewshire literature from the French Revolution to the First World War. The list of luminaries goes on to include James Kelman, Suhayl Saadi, Ajay Close, Graham Fulton, Louise Turner and Dr Jim Ferguson, to name but a few whose work contributes to our understanding of the impact of significant developments in social history including Thatcherism, multiculturalism, feminism, the Suffragette movement, the American Civil War, and Medieval Renfrewshire, all of which has its fair share of – you guessed it – rebels.

Today, there is definitely a strong relationship between radicalism, activism and the arts. I’m often asked to write for organisations seeking to transform attitudes on issues ranging from mental health, addiction and recovery, refugees and modern slavery. Radical writers need original and creative ways of getting their work out there, and often these connections are driven by passion and the creative impulse to make a difference. For twelve years, I ran an eco-poetry quarterly from my front room, receiving contributions from around the world, and donating all the proceeds to conservation charity. The magazine collaborated with Paisley Hill Walking club in a sponsored poetry fundraiser, and Edwin Morgan was even so kind as to contribute an unpublished poem. Today, I am involved with Jenny’s Well Press, Paisley’s only indie publisher, run on a voluntary basis by a team of dedicated writers and editors. Indies often have to come up with radical ways of doing things, and this can lead to innovative alliances in the creation and distribution of books, for example, with charities and socially and environmentally conscious retail outlets. Every copy of my novel sold in Shelter helps fight homelessness.

Radicalism is defined as beliefs or actions that advocate complete political or social reform, and Paisley Book Festival is celebrating the tradition of rebellion by hosting literary events that recognise where contemporary change is taking place, including disabled and low income access to publishing, stories of rebel women, queer identities, the #MeToo movement and BAME writing. It features contributions from some of contemporary literature’s most radical voices like Jenni Fagan, Jackie Kay, Alan Bissett, Chris McQueer, and Mara Menzies, as well as exploring fictional rebels and Tom Leonard’s Radical Renfrew thirty years on. So, switch aff yer Netflix, and find yer inner rebel at Paisley’s Book Festival. They may take our lives, but they’ll never take our freedom, or our books!

Paisley Book Festival

20-29 February 2020

https://paisleybookfest.com/events/

Photo: Tricia Hutchison, Blind Harry by Alexander Stoddart.

Published on February 19, 2020 01:48

December 11, 2019

A Goodreads Novice

I signed up to Goodreads three months ago, determined to drag myself into the digital age. After several hours and countless cups of tea, I negotiated my way through the Goodreads author programme, created my author profile and listed my books. I waited for the emails to start pinging, the followers to start flocking. Perhaps something else was needed to blow away the digital dustballs. I had to find some friends! Goodreads obligingly searched through my Facebook contacts and linked me up with a few familiar faces. I decided I’d better have something to talk about and quickly began looking for authors to follow, mostly Scottish authors whose worked I admired. Now all I had to do was go into 'My Books' and list every book I'm reading or want to read. Goodreads obliged me by making a few suggestions. And voila! I waited. The days went by. Followers: 0. I began wondering what was the point of all this. But why! I cried, into the virtual void. Is this not a place for people who think all day about books? How could I be a social pariah in this, my most ideal of environments? I noticed many other authors who seemed to be in a similar situation. Perhaps it's because maintaining a digital profile can be a bit of a challenge to us socially awkward authors. And is having large number of followers when you're not Ian Rankin or Dean Koontz indicative of quality? As an experiment, I joined a couple of Goodreads groups. A few people offered me reviews in return for cash, but the quality of their reviewing left much to be desired. I even started my own group about Scottish fiction, but quickly dropped the idea thinking that the time spent nurturing a following outweighed the possible benefits. So now I’m facing up to the fact that I’m just not very good at this sort of thing. There are other ways of promoting your work that are more fun, and produce better results. If that makes me the digital equivalent of a British Telecom phonecard, them I'm proud of my primitive status. Goodreads is what it is, and so long as I don't expect anything other than some interesting book recommendations and a forum to place reviews and the odd article, should anyone ever want to read it, then I won't be disappointed.

Published on December 11, 2019 05:54

Paisley Patter by Tracy Patrick

A blog by Paisley writer, Tracy Patrick, author of the novel, Blushing is for Sinners, and poetry collection, Wild Eye Fire Eye. http://www.tracypatrick.org/

A blog by Paisley writer, Tracy Patrick, author of the novel, Blushing is for Sinners, and poetry collection, Wild Eye Fire Eye. http://www.tracypatrick.org/

...more

- Tracy Patrick's profile

- 11 followers