Ted Russ's Blog

November 22, 2025

How to yell at a bear when you are fast asleep.

If you’ve read any of my blog, you know we get our share of black bears up here. Big ones, small ones, fat ones, skinny ones. Like everything else, they ebb and flow across our little patch according to the mountain’s invisible rhythm.

And we are all for it. We like bears. We respect bears. They are an integral and wonderful part of the neighborhood.

But this fall they started “flowing” around the coop a little too much. There is a fine line between “picturesque mountain life” and “nature documentary with casualties,” and we don’t want to cross it—particularly not with our beloved chickens.

So, I had a choice—stay up late sitting in the dark with an air horn and shotgun, waiting for a bear that might never show up, or figure out a remote solution.

I like sleep, so I started looking for the remote solution.

Now, hear me on this: I’m not interested in hurting a bear for being a bear. They’re doing what bears do—wandering around, sniffing out calories. I just need them to update their internal map so that our coop is flagged as “absolutely not worth it.”

So the question was: how do you give a bear a really bad sixty seconds without harming it?

Answer: something that could go boom without me being there.

Enter a centuries-old (or older?) solution—the tripwire.

After a little research, I found the perfect device—a small metal housing that can mount to a post or tree and holds a 12-gauge blank round. A firing pin sets the thing off when the tripwire pulls a small retention pin.

It’s perfect. Bear sniffs around the coop, drags a paw across the hardware cloth, hits the tripwire, and BOOM. No projectile, no buckshot, just a loud, startling, and educational noise. (After a couple of test runs, I can attest to the quality of the boom.)

I installed it where the bears tend to do the most sniffing and damage, made sure the tripwire was taut, and left it armed for our next nocturnal ursine guest.

See the little orange wire? You can also see the square repair job necessitated by one of the recent bear visits.

And naturally—because this is how the universe works—we haven’t had a single bear come by since.

Honestly, that’s fine. Nothing happening is a win for me and the girls. As I wrap this entry up, here is the situation:

Bears: quiet, hopefully exploring other parts of the mountain.Chickens: alive, opinionated, utterly unaware of the drama.Tripwire: armed and patiently awaiting its big moment.Me: sleeping well.When (not if) the thing goes off, I expect to see a moment of high-velocity bear butt skying over the coop fence to get away from the boom.

And I’ll keep you posted.

October 15, 2025

Da Bears

October is close to perfect up here. Mild weather and changing colors, but not a million leaves on the ground yet. We have a huge maple on the east side of the house that always kicks things off. She’s blazing now. I love the red.

October also means everything is moving, getting as fat as possible before winter, including the bears. We’ve got a couple of regulars that hang out this time of year and we get a lot of drive-bys.

One of our regulars is a grey-faced fatty that we estimate to be around 450 pounds. Check him out.

The concern right now, though, is a juvenile that has taken an interest in the coop. He or she (I can’t tell) has been by a few times and has pulled down sections of wire trying to get in. Here is one of his visits:

Here is another of his visits when he took an interest in a coffee cup left in the chicken paddock. (Yeah... I put honey in my coffee and I left it out like a jackass)

I’ve been wracking my brain trying to devise a way to prevent him/her from getting too comfortable and habituated—one that does not involve me staying up all night. I came up with a plan… I’ll let you know how it goes.

September 15, 2025

Finally!

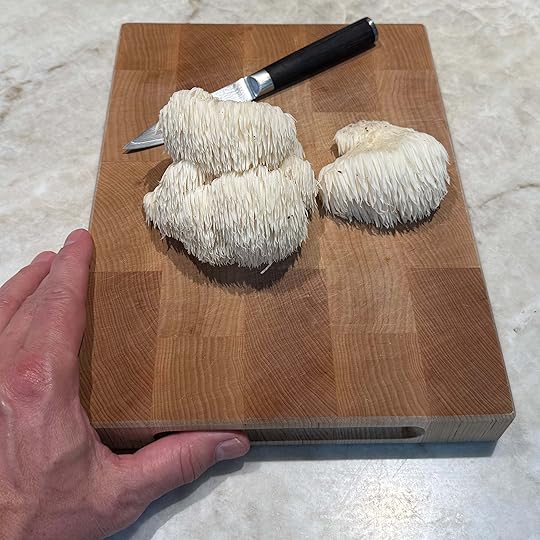

Anna and I have been trying to grow lion’s mane mushrooms for a while. We think they’re cool for a couple of reasons.

To begin with, they are beautiful. Otherworldly. Like an ethereal white… well… lion’s mane in the forest.

Then there are its nutritional benefits—some long believed (Buddhist monks in East Asia used it in tea to improve concentration during meditation) and some well documented, including cognitive, neuroprotective, and anti-inflammatory benefits.

Finally, they’re a delicious culinary head fake. You take a bite of lion’s mane expecting an earthy, meaty, of-the-forest mushroom experience, but instead you get a firm, slightly briny taste with a fibrous mouthfeel and clean finish. Very similar to lobster or crab.

So, we really wanted to figure out how to grow them.

We had a promising totem going about six years ago at our old place in the woods in north Georgia, but we ended up having to move before a decent harvest. I like to think those logs are still productive and some family of black bears enjoys them. We got plenty of shiitake and oysters out of that effort. But the lion’s mane never progressed beyond an initial, tentative baby bloom.

We moved to the Ridge in the summer of 2020. In February 2021, we inoculated six mushroom totems, including two lion’s mane. All six had failed by that summer. (I think I know what I did wrong. Gonna try totems again next spring.)

With the garden and bees and chickens and dogs and a day job, I just couldn’t pull my act together to try again until last year.

In April of ’24, we inoculated a bunch of logs, this time using the “drill-and-fill” method. This involves drilling holes in a seasoned hardwood log in a diamond pattern, filling the holes with sawdust mushroom spawn, and then sealing the holes with beeswax to prevent them from drying out.

Then you wait.

We placed them in the shadows of a rhododendron in the woods near the garden and tried not to obsess over them when we walked by.

By this spring, I thought we had struck out again. Even the shiitake logs had not produced. Lion’s mane takes longer (often more than 18 months), but the fact we struck out with the shiitakes didn’t bode well.

Then, BOOM.

They arrived!

We got a huge flush in late August.

We got a huge flush in late August.

They were good eating!

I like to sauté ’em in butter and garlic, pop in a splash of tamari in the last 30 seconds, then season with salt and pepper. (Recipe at the end.)

I like to sauté ’em in butter and garlic, pop in a splash of tamari in the last 30 seconds, then season with salt and pepper. (Recipe at the end.)

With any luck, we’ll get two or three flushes a year for the next couple of years.

With any luck, we’ll get two or three flushes a year for the next couple of years.

Garlic–Tamari Lion’s Mane

Serves: 2 • Time: 10–15 minutes

Ingredients

1 large lion’s mane mushroom (torn into bite-size chunks)2–3 cloves garlic, minced1–2 tbsp olive oil (or a mix of butter + olive oil)Splash of tamari (or soy sauce)Kosher salt and freshly ground black pepperInstructions

Dry sauté: Heat a skillet over medium-high. Add the torn lion’s mane and cook dry until it releases its water and the liquid mostly evaporates.Add fat: Add olive oil (or butter + oil) and toss to coat.Garlic: Add the minced garlic and sauté gently until fragrant.Season: Sprinkle with salt and pepper.Brown: Continue cooking until the edges are golden and slightly crispy.Glaze: In the last 30 seconds, add a splash of tamari and toss quickly—just enough to glaze, not steam.Serve: Plate immediately and enjoy hot.

August 15, 2025

Baby Chickens!

This Blog has been interrupted to bring you BABY CHICKENS!!!

I'm a two day old Rhode Island Red!

I'm a two day old Rhode Island Red!

We got five day-old chicks in late July. Two Rhode Island Reds, two Olive Eggers, and one Lavender Buff Orpington. They’ll be four weeks old this weekend and are already exhibiting biker gang qualities. Perfect for the Ridge.

A rare moment of calm for the gang

A rare moment of calm for the gang

Right now, they are in a dog crate in our basement. In about three weeks, once their feathers have filled in, they will graduate to the outdoor coop with the OGs.

Ripple is fascinated!

Ripple is fascinated!

I'll post an update when they graduate to the outdoor coop.

June 24, 2025

Heroine's end

Sad day. If you read my post about the journey of the Bald-Faced Hornet queen, you will get it. (Blog from 5 June 2025)

Pretty bummed.

This is the downside of anthropomorphizing…

June 5, 2025

The Heroine's Journey

I realize I am a sentimental dope, but I can’t help anthropomorphizing when I learn about things up here on the Ridge, can’t help but seeing poignant story arcs. More often than not, it results in a new soft spot in my dopey heart.

My latest affliction of affection is the Bald-Faced Hornet.

Hear me out on this—let’s see if you have any feels on the topic when I’m done.

(Caveat for the reader: I am not an en[image error]tomologist or naturalist or man of any great learning.)

I was walking in the woods with some friends several weeks ago when we came across a small, strange looking nest-like object attached to a young tree at about head height. After speculating on what type of nest it was, we continued on our way. Here is a picture from that day:

I since visited the nest several times (at a safe distance) and got a few pictures of the hard working insects as their home grew in size.

Using the photos and the interwebs, I identified my neighbors as Bald-Faced Hornets. First thing I learned is that they are not hornets. They are actually wasps, closely related to the Yellowjacket. (Yeah… I don’t get it either)

But it is the rest of what I learned that really got me.

Turns out the nest we happened across was only about a week old and had been built by the queen herself. Inside that fragile little sphere of paper was a handful of gestating workers. When they emerge, maybe four weeks later, they got to work helping to expand the nest. You can see the progress in the photo below.

The nest is made of chewed up dead wood, like fallen logs or branches. (So, major recycling points for the ladies)

When the colony is thriving by the end of the summer, the nest will be the size of a football or even larger, and home to hundreds of fierce wasps. (Minimum safe distance will have expanded from what it is now!)

Then, as the days shorten and the weather cools, the plot turns.

The queen starts to produce fertile females and males. (Through the summer she has been producing primarily infertile female workers). When the few hundred young, fertile females emerge from their cells, they mate with eager males that usually travel from another nest.

Having served their only purpose, the males promptly die. The young queens try to fatten up before winter. Then, around November in these parts, the young queens leave the nest, never to return. They forge ahead alone.

As the temperatures plummet, the young queens burrow into the forest floor or a dead tree and enter a hibernation state called diapause. Get this—their bodies actually create anti-freeze proteins to ward off cell damage from extreme cold.

The old queen, back at the rapidly emptying nest, having successfully raised a colony from nothing… dies.

Her empty nest is empty. Never used again.

Months later, when the weather warms, the solitary young queens emerge from their hidden hibernation to begin the cycle all over again.

They each pick a spot, build a small starter nest on their own, begin producing workers, and race against winter to raise a colony that can support the production, rearing, and fertilization of hundreds of young queens before the cold sets in.

Why hundreds, you ask?

Because most don’t make it. Only a small fraction will survive and establish successful colonies the following year. It’s a numbers game.

That’s a tough life for a queen.

I can’t help but contrast it to the path to the throne for a honeybee queen. Briefly, for the sake of comparison, if the Bald-Faced Hornet faces a solitary survival challenge, think of the honeybee’s as a murderous gauntlet of stingers.

When a honeybee hive needs a new queen, it will produce between 10 and 20 new queen bees. (Its a very cool process involving something called “Royal jelly” we should talk about sometime) The first queen to emerge goes around and kills all her rivals by stabbing them with her long stinger while they are still in their cells. (The queen is the only bee in the hive that can sting more than once.) If multiple queens emerge at the same time. They fight to the death.

There can be only one.

Ever since we got bees, I can’t help but think about the queen’s journey every time I look at our hives down at the garden. Now that I know a little more about the Bald-Faced Hornet, I won’t be able to look at a nest the same way I used to either. Heavy lies the crown.

As I told you up front, I am not an entomologist. But I appreciate a good story when I see one. Think about the journey of one of these heroines. Born in a nest teeming with siblings, mated in flight by suitors that promptly die, she leaves the nest alone and buries herself for the winter. Waking up months later if she survives, she must navigate the wilderness on her own, searching for a place to start building a new nest. Hopefully, if all goes well, her colony will pull through so that she can pass the lonely mission on to her daughters. Finally, she will die as the young queens leave, not knowing if they will succeed.

And that harsh, poetic heroine’s journey in three acts plays out over less than twelve months. Every year.

I warned you I was an anthropomorphizing sentimental dope.

May 15, 2025

Bees Kinda Suck at Flying

Honey bees are amazing collaborators, the very origin of the term “hive mind.” Every day is like an expertly-tuned eighty-thousand-piece orchestra.

Except in the airspace in front of the hive—there it’s a shit show.

I’ve been a mediocre backyard beekeeper for a few years now. I’m not very good at it yet. But I try. At the moment, I’ve got one hive sharing the garden with us that is on its fourth year. My longest run yet!

This damn heat dome hovering over us has everything on the Ridge seeking relief. By the afternoon each day, there is a dark cloud of bees swirling in front of the hive, trying to stay cool.

That cloud of foragers flying around in front of the hive has always fascinated me.

When I first started keeping bees, it scared me a bit.

It looked threatening. Aggressive. I pictured them taking offense at my presence, chasing me away, dozens of stingers piercing my skin.

As I got more comfortable being around the girls, though, and spent more time observing them up close, the cloud of bees became less threatening

Then I sat down next to my first hive one afternoon and watched them for about half an hour.

Soon I was laughing.

I have to tell you this, as a former helicopter pilot…

Bees suck at flying.

I don’t mean they don’t get it done. Obviously they do—Just one 16-oz jar of honey, for example, represents well over 100,000 flight miles. In a good year, a strong hive can produce a hundred 16-oz jars of honey representing over 7 million total flight miles.

So, yeah… they get plenty of flying done.

It just ain’t pretty.

It makes sense when you realize that most of the bees zipping around outside the hive are just a few weeks old.

A few weeks!

A few weeks into flight school, I still couldn’t land a helicopter without killing myself and everyone else on board.

During the summer, the average worker bee only lives about six weeks. She spends the first two or three weeks doing shit details inside the hive. The only times she leaves and gets to fly are for occasional jaunts to relieve herself. Not the most extensive flight training.

Around the third or fourth week, worker bees are “promoted” to foraging. They sally forth into the world each day in search of pollen, nectar and water.

So, that cloud of bees in front of the hive that used to scare me is made up of hundreds of bees who have only had a few training flights to figure out how their wings work. Half of the bees in the cloud are trying to take off on their foraging mission. The other half is trying to bring it in for a landing, fully loaded with cargo.

Your browser does not support the video tag.

When I observe the flight operations in front of a beehive with a former pilot’s eye, I see every rookie mistake I ever made. But the most common mistakes on display are these:

Mistake #1 - Hot-and-Heavy LandingsI don’t care what aircraft you fly; load it up to max gross weight, and you’re in for a tense landing. When you are heavy, you work hard so that you don’t “get behind the aircraft”—even in a Chinook.

Chinooks are powerful flying platforms, by the way, because all of their power goes to generating lift through their twin rotor discs. On a conventional helicopter, 15% to 20% of power is diverted to the tail rotor for directional control. But a Chinook achieves directional control by tilting its rotor discs—so all power goes to lift.

But as powerful as a Chinook is, you can still get in a lot of trouble when flying her at max gross weight. The engines and transmissions are under a tremendous amount of stress and it is easy to overtax and damage them. The aircraft is sluggish and slow to respond to control inputs. This means you have to “stay ahead of the aircraft”—To plan and anticipate so that you avoid having to make sudden inputs that overtax the airframe or power train and that might not get you out of trouble.

A honey bee is built a lot like a Chinook: its wings generate both lift and thrust. And it can haul more than 35 percent of its body weight in pollen or nectar—about the same load ratio as a fully fueled, crewed, and laden Chinook. A bit of symmetry in the universe I find pretty cool.

The point is, the Chinook pilot and the honeybee are in similar situations when they land heavy. It is an unforgiving phase of flight, and the biggest protection from mishap is experience.

And they’re only about three weeks old!

Mistake #2 - Feeling for the GroundLike all aircraft, honey bees and helicopters have to deal with ground effects when flying at very low altitudes. Ground effects occur when the air being thrust down from the aircraft’s lifting surfaces can’t get out of the way fast enough. It basically piles up and creates a cushion of air that buoys the aircraft.

Ground effect can be a great thing if you are in that max gross weight situation and need a little help not pranging the aircraft, but not so great if you are trying to land quickly and efficiently. It takes a little experience to learn how to anticipate ground effect and account for it. In a helicopter, when hovering or landing, it means that you have to take out more power the closer you get to the ground. It’s counterintuitive. And it is the same for a honeybee.

The problem is that, early on, a novice pilot is not a good judge of rates of closure. What is too much? What is too little? Seeing the ground rushing up quickly is unnerving, and the natural reaction is to increase power to slow your descent. Usually, the novice does that right about the time ground effects kick in, so the aircraft lurches back up. So, the pilot takes out the power. And the ground rushes up. So, the pilot increases power… you get the picture.

It’s hilarious to watch, if you have the time. Sitting next to the hive or on one of the training airfields down at Fort Rucker, you can easily spot the pilots having trouble landing. They inch down, their six legs extending to meet the ground, then they surge back into the air. They hover around for a few seconds, confused, then start sinking towards the ground again. Then they surge back up. And so on.

Watching a tired honeybee try to land herself takes me back to those old training airfields in Alabama during the summer of ’91, the flight instructor yelling at me, my buddy behind me in the jump seat laughing, my aircraft porpoising across the landing area.

Mistake #3 - Failure to Clear Flight Path Before Take OffA worker leaving the hive on a foraging mission walks out of the hive opening, takes a few purposeful footsteps and then launches herself into the air in what we called, back in the day, a max performance take off. Obstacles or other honey bees be damned.

Sometimes this method works out, and the departing forager sails off into the wide blue yonder on her mission without affecting her airborne sisters in the cloud of bees.

But, at least half the time, her departure cuts off an approaching bee, causing them to make last-minute adjustments to their flight path or—worse—causes a midair collision.

Hilarious to watch.

Maybe I shouldn’t laugh.

I mean, if you were to put me into the same small airspace with HUNDREDS of other aircraft trying to land and take off at the same time with NO AIR TRAFFIC CONTROL at all, I would probably stroke out from terror.

In an aircraft, you don’t do shit without ATC permission. They assign headings and altitudes and keep all the flying machines from banging into each other. Beehives don’t have ATC. They have instinct and millions of years of evolution that have instilled within them a drive to survive.

But no air traffic control!

On a warm day when the pollen abounds, and the nectar is flowing, it’s nuts.

“Um… You’re in my landing spot!”

Worker bees launch themselves as fast as they can into the air as their comrades careen towards the hive, loaded down with cargo and unable to control their descent. Others, less heavy with payload, hover in front of the hive, lurching up and down trying to land.

The result is an endless succession of midair collisions.

In the Army, the thought of a mid-air collision made my blood run cold. They killed people. I had my share of close calls that I still don’t like to think about.

Fortunately, there are two big differences in front of a beehive.

None of the girls are carrying highly flammable jet fuel on board, and they are all equipped with exoskeletons.

A honey bee, like all insects, has a hard outer shell called an exoskeleton. It’s made of a substance called chitin—similar to the tough stuff in your fingernails. It’s hard, but flexible and can support a lot of weight and absorb impacts. Their wings are chitin as well.

So, when the foragers collide, it doesn’t do much damage.

It’s funny, though.

They tumble, spin out, and cartwheel through the air or across the landing surface in front of the hive.

Then they get up and try again.

And again.

Until finally, they are safely back on the ground.

They walk into the hive, drop their payload, turn around and do it again.

Kinda inspiring.

April 18, 2025

The Slippers and the Still

Each year, in late April and early May, we enjoy a small colony of Lady Slippers near the end of our driveway. Several dozen of the distinctive pink orchids pop up in a scattered constellation about fifty yards across, with our driveway running through the middle. They only last about two weeks, but they steal the show every day they’re around.

A cluster of four with two more coming up

Like most orchids, Lady Slippers are a lesson in patience and cooperation. Their seeds are tiny—like specks of dust—and carry no food or nutrients. To compensate, the flower has evolved to share a symbiotic relationship with a specific fungus that weaves through the forest floor. When the soil conditions are just right—acidic, well-drained, often under pine—the fungus thrives. Then, as if designed for this one purpose, it reaches out and attaches to the Lady Slipper seed, coaxes it open, and begins to feed it. I’ve read that, once mature, the orchid returns the favor, sharing nutrients with the fungus. I’ve also read that this never happens, that the relationship is purely parasitic.

I like the first version.

Another intriguing thing about this particular orchid-supporting patch of woods is that it used to host a moonshine still. That kind of activity was common in this region for a long time, and we come across old sites on our hikes around the Ridge—rusted barrels, collapsed fire pits, half-buried old coils. Usually hidden beneath thick rhododendron on the banks of a stream, these sites always strike me as a little melancholy—once prized and fiercely protected, maybe even providing income that fed a family, now forgotten.

Part of the old still. Orchids out of frame.

But this old still makes me smile. It got lucky—spending its retirement years in a lovely, sun-dappled pine grove visited every spring by pink Lady Slippers. Judging from the rust and structural decay, I’m guessing the still is 30 to 50 years old. Probably about the same age as the orchid colony, if not a bit younger. Individual Lady Slippers take 16 years to flower for the first time and can live more than 50 years.

Another piece of the still watching over an orchid

I like to think that the old still and orchids in this spot struck up a quiet partnership decades ago—that white lightning fueled the fungi and orchid seed hookups resulting in this durable little colony. And now the rusting old still and briefly blooming Lady Slippers are old friends, sharing the small pine grove as the world turns.

March 31, 2025

First Comes the Rose, Then Comes the Rattler

The rain and warmer weather always make the transition from winter to spring fun up here. The Ridge shakes off the cold and comes alive in ways big and small. I love that things always seem to follow a certain sequence, as if Mother Nature has a checklist. First, this wakes up. Then that. Then this. Every year.

One of my favorite ways to track spring’s progress up here is the flowers.

The first to pop are always the Lenten roses. No matter how cold and inhospitable things are, they are first to bloom in late February like clockwork. We’ve got a small one near the door to my basement office that I walk by a dozen times a day. It’s always a little thrill when I spot its first flowers—the quiet promise of warmer days.

They are alone in their enthusiasm for a few weeks, though. Long enough that I always wonder if this is the year they mis-timed things. That jackass bloomed early again—no way it makes it to April. But pale and delicate as they seem, they always make it. The one in the picture below is still going strong as I write this in the second week of April.

[image error]

Then—right on cue, around mid-March—the daffodils pop and I know it’s on. Unburdened by any of the Lenton rose’s sense of restraint, the burst of yellow is jarring and unapologetic against the faded brown of the Ridge’s winterscape. They don’t last long, though. A week, maybe.

After that, the trillium erupts widely across the Ridge.

For some reason, we only have purple trillium up here. Dunno why. And the trillium seems always to be accompanied by bloodroot (which is a white flower, funny enough—its sap is an orange-red).

For some reason, we only have purple trillium up here. Dunno why. And the trillium seems always to be accompanied by bloodroot (which is a white flower, funny enough—its sap is an orange-red).

The wisteria gets serious in the first week of April.  Then, by the second week, a wide assortment of blooms are breaking loose all over the Ridge. We even have some marigolds firing off at the moment.

Then, by the second week, a wide assortment of blooms are breaking loose all over the Ridge. We even have some marigolds firing off at the moment.

And soon… One of the more enigmatic flowers on the Ridge will appear. More on that some other time.

There is another checklist happening too: Insects, then bats, then lizards, then toads and frogs, and finally—yep—snakes.

We are up to lizards so far. Gonna have to be more mindful on our walks. We always see our first timber rattlesnake before the end of April.

February 7, 2025

Why I Rewrote Spirit of the Bayonet

I’ve been a sci-fi nerd for as long as I can remember. I love it in every format—novels, comic books, movies, whatever. Science fiction is both fun and thought-provoking, and it still makes up about half of my fiction reading.

So, after publishing Spirit Mission, I guess it was inevitable that I’d try writing a sci-fi series. A big, hairy, multi-book, headlong dive into the future. I spent a couple of years hammering away at the first book. It was a blast—like, a lot of fun. But I made every possible mistake. Here are just the biggest ones:

1. Just Start Writing—Unburdened by a Plan

I didn’t think about the architecture of the series or the story arc of the book. I’ve since reflected on why, and I think I know the answer. Spirit Mission was such an important story to me I agonized over every aspect of it. It was a labor of the heart—heavy on the labor. But when I jumped into sci-fi, the stakes felt lower. I just let it rip. And rip. And rip…

2. Throw It All In

Everything I’d ever loved about sci-fi ended up in the book. Powered battle suits, derelict spacecraft, evil corporations, sexy robots—you name it. It also became a place to explore my excitements and misgivings about AI and military ethics. My teenage obsessions and my mediocre philosophy major found their way into the text in a way that lacked restraint.

3. Make It Too Long

The book ended up being almost two books' worth of content. Now, some people like long books—I know I do—but by not exerting discipline over the first book’s structure, I undermined the structure of the entire series.

4. Call It a Trilogy… Because Trilogies Are Cool

Not because the story was actually going to fit neatly into three books, but because I thought trilogies were cool. I am such a jackass.

5. Kill Any Momentum by Taking a Break

Spirit of the Bayonet got a warm reception for an un-marketed, indie-published book. I got messages from readers expressing enthusiasm and asking when Book II was coming. So, like a genius, after Spirit of the Bayonet was published, I immediately dove into writing Duty’s Cost. Creatively, it was the right move—I’m really proud of that book—but it killed whatever small momentum the Spirit of the Bayonet universe had.

So, Why Rewrite It?

When I came back to it and took a hard look at Spirit of the Bayonet, I knew it needed work. Here’s why:

Story First: That first attempt didn’t accomplish what I wanted. As a writer, I want to construct a multi-book arc that grips the reader all the way to the end. My original version didn’t set that up well.Character Evolution: My vision for the characters had evolved, and the long arc of the story had become clearer.Because I Can: The joy of being an indie author is having the freedom to be creative however I want (or need) to be.So, I dove in, ripped it in two, rewrote much of it, and added about 30% more content.

Then I dove into the next book.

Book III is now with the editor, and I’m working with my cover guy on designs. This phase always involves waiting and then surging to the finish, so I’m using the time to start outlining Book IV. I think this series will end up being six or seven books by the time the last page is written—but we’ll see.

My goal is to drop all three books at once in May. I’ll keep you posted and hope to have covers to share soon.

TR