Mohammad Rabie's Blog

January 2, 2018

Harper’s Magazine’s article about Otared: After the Revolution. Three novels of Egypt’s repressive...

By: Yasmine Seale

Original article here on Harpers.org

If Naji’s dystopia has the low-stakes lightness of a dream, Mohammad Rabie’s Otared is an unadulterated nightmare. The novel begins with a cannibal crime scene of rare ghoulishness and gets steadily grimmer. Our guide to this underworld is Ahmed Otared, good cop turned partisan. It’s 2025, and East Cairo has been occupied for two years by the armies of the Knights of Malta, land pirates with no territory of their own who speak “Arabic like Tunisians, and English in many different dialects.” The invasion was as swift and total as it was unopposed; only a lionhearted few still hold out. The bourgeois island of Zamalek has become the eye of the resistance. From the top of a tower in its midst, Otared, a matchless sniper, looks out over the divided city (the West remains free) and trains his scope on the enemy, cold-blooded behind his mask. “I was an ancient Egyptian god with a borrowed face, whose true features no man could ever know… . A Greek god, full of contempt for the world that he’d created.”

Whatever one thinks of the legitimacy of armed struggle, it does not take long for the resistance to overstep even the widest definition of guerrilla warfare and devolve into outright slaughter. What is remarkable about this shift is how slow we are to notice it. Otared is a companionable narrator, and at first we cannot see the murderer for the fancy prose style; one of the novel’s most chilling moves is the ennoblement of evil through formal beauty. Served by Robin Moger’s exceptionally fine translation, its mazelike structure and sensitive flashes of description are a lesson in the seductions of art. (Here is our terminator describing a line of blood: “It reminded me of an ostrich’s tail feather, a column of water rising from a fountain, the glowing tracks of fireworks launched across the sky.”) At regular intervals Otared takes stock of those he has killed, and these lists grow longer every time, a paratactic mess of names and bodies. Yet the slowly gathering rhythm has the effect of an ostinato, a musical pattern repeated and amplified. Violence is so carefully and insistently woven into the pattern of the novel that it cannot be senseless; something else, we come to suspect, must be at work.

And so it is. One of the longer roll calls of the dead provides a hint that Otared’s killing spree might not be quite what it seems:

And I killed a southerner called Gowhar, dressed in a broad-sleeved robe. I shot him in the neck with a single bullet, and he took to his heels, bleeding, and I let him go because I knew he’d die in a few minutes and that nobody would be able to help him.?.?.?. And I looked for Samira al-Dahshuri. She’d be walking beneath the overpass, I knew, and I swept the area through my scope, and when I saw her I fired without hesitation into her liver. It had been cirrhotic for years, and maybe she felt the bullet ripping through it and killing her. Maybe that is why she hunched over and peered at the spot as she died.

What kind of a sniper is this, and why is he blessed with a total, transcendent awareness of his victims’ lives? Why, at the moment of their death, does he describe them with something close to love?

Another clue lies in the novel’s cyclical structure: some sections pan back to 2011, and at its midpoint is a single, very brief chapter set in the year of the Hegira 455, or ad 1077. It is a testament to Moger’s flair for the varieties of English—and how they might map onto the many registers of Arabic—that within a few lines it is beautifully, mysteriously apparent that we have been transported a thousand years back in time. Here, a man attends a burial and comes to a violent understanding (“Hope shall be set in your hearts, and hope there is none, and hope is your torment”), which foreshadows the novel’s final revelation. It is not spoiling things too much to say that this key, when it comes, both clarifies the novel’s cruelty and upends it, turning its sadists into angels of mercy. A dystopia can also be a world turned on its head.

Yet the realization that Otared’s savagery is only a negative image of the truth does not redeem it entirely. Having sat through the horror show—public suicide and stoning, a miscarried fetus on a plate, homeless girls raped by a homeless man—one could be forgiven for not standing to applaud its basic conceptual trick. One part of the nightmare, however, contains the seed of something brighter. The chapters set in 2011 revolve around a man, Insal, who adopts a little girl after her parents disappear. The girl, Zahra, develops a strange ailment that causes her eyes, ears, and mouth to seal themselves shut until she is nothing but a smooth lump of flesh that has to be fed through a tube, cut off from the world of the senses. Eventually she is reunited with an aunt who suffers from the same affliction. That Zahra’s character should be one of the few not only to survive the novel but to experience a moment of connection comes as a poignant relief.

Zahra kept running her hand over her aunt’s cheek. Slow, even passes, testing out her favored sense: touch. At the nasal openings, she stopped, lifted her head, and stuck the tips of her first and middle fingers into the holes. There was a momentary lull, then the aunt released a sudden blast from her nose and Zahra snatched her hand away in feigned alarm. The aunt rocked her head back, as did the girl, then the two foreheads met once more. They were laughing.

After the Revolution. Three novels of Egypt’s repressive presentBy: Yasmine SealeOriginal article...

By: Yasmine Seale

If Naji’s dystopia has the low-stakes lightness of a dream, Mohammad Rabie’s Otared is an unadulterated nightmare. The novel begins with a cannibal crime scene of rare ghoulishness and gets steadily grimmer. Our guide to this underworld is Ahmed Otared, good cop turned partisan. It’s 2025, and East Cairo has been occupied for two years by the armies of the Knights of Malta, land pirates with no territory of their own who speak “Arabic like Tunisians, and English in many different dialects.” The invasion was as swift and total as it was unopposed; only a lionhearted few still hold out. The bourgeois island of Zamalek has become the eye of the resistance. From the top of a tower in its midst, Otared, a matchless sniper, looks out over the divided city (the West remains free) and trains his scope on the enemy, cold-blooded behind his mask. “I was an ancient Egyptian god with a borrowed face, whose true features no man could ever know… . A Greek god, full of contempt for the world that he’d created.”

Whatever one thinks of the legitimacy of armed struggle, it does not take long for the resistance to overstep even the widest definition of guerrilla warfare and devolve into outright slaughter. What is remarkable about this shift is how slow we are to notice it. Otared is a companionable narrator, and at first we cannot see the murderer for the fancy prose style; one of the novel’s most chilling moves is the ennoblement of evil through formal beauty. Served by Robin Moger’s exceptionally fine translation, its mazelike structure and sensitive flashes of description are a lesson in the seductions of art. (Here is our terminator describing a line of blood: “It reminded me of an ostrich’s tail feather, a column of water rising from a fountain, the glowing tracks of fireworks launched across the sky.”) At regular intervals Otared takes stock of those he has killed, and these lists grow longer every time, a paratactic mess of names and bodies. Yet the slowly gathering rhythm has the effect of an ostinato, a musical pattern repeated and amplified. Violence is so carefully and insistently woven into the pattern of the novel that it cannot be senseless; something else, we come to suspect, must be at work.

And so it is. One of the longer roll calls of the dead provides a hint that Otared’s killing spree might not be quite what it seems:

And I killed a southerner called Gowhar, dressed in a broad-sleeved robe. I shot him in the neck with a single bullet, and he took to his heels, bleeding, and I let him go because I knew he’d die in a few minutes and that nobody would be able to help him.?.?.?. And I looked for Samira al-Dahshuri. She’d be walking beneath the overpass, I knew, and I swept the area through my scope, and when I saw her I fired without hesitation into her liver. It had been cirrhotic for years, and maybe she felt the bullet ripping through it and killing her. Maybe that is why she hunched over and peered at the spot as she died.

What kind of a sniper is this, and why is he blessed with a total, transcendent awareness of his victims’ lives? Why, at the moment of their death, does he describe them with something close to love?

Another clue lies in the novel’s cyclical structure: some sections pan back to 2011, and at its midpoint is a single, very brief chapter set in the year of the Hegira 455, or ad 1077. It is a testament to Moger’s flair for the varieties of English—and how they might map onto the many registers of Arabic—that within a few lines it is beautifully, mysteriously apparent that we have been transported a thousand years back in time. Here, a man attends a burial and comes to a violent understanding (“Hope shall be set in your hearts, and hope there is none, and hope is your torment”), which foreshadows the novel’s final revelation. It is not spoiling things too much to say that this key, when it comes, both clarifies the novel’s cruelty and upends it, turning its sadists into angels of mercy. A dystopia can also be a world turned on its head.

Yet the realization that Otared’s savagery is only a negative image of the truth does not redeem it entirely. Having sat through the horror show—public suicide and stoning, a miscarried fetus on a plate, homeless girls raped by a homeless man—one could be forgiven for not standing to applaud its basic conceptual trick. One part of the nightmare, however, contains the seed of something brighter. The chapters set in 2011 revolve around a man, Insal, who adopts a little girl after her parents disappear. The girl, Zahra, develops a strange ailment that causes her eyes, ears, and mouth to seal themselves shut until she is nothing but a smooth lump of flesh that has to be fed through a tube, cut off from the world of the senses. Eventually she is reunited with an aunt who suffers from the same affliction. That Zahra’s character should be one of the few not only to survive the novel but to experience a moment of connection comes as a poignant relief.

Zahra kept running her hand over her aunt’s cheek. Slow, even passes, testing out her favored sense: touch. At the nasal openings, she stopped, lifted her head, and stuck the tips of her first and middle fingers into the holes. There was a momentary lull, then the aunt released a sudden blast from her nose and Zahra snatched her hand away in feigned alarm. The aunt rocked her head back, as did the girl, then the two foreheads met once more. They were laughing.

May 11, 2017

Black Gate Interviews Egyptian Science Fiction Author Mohammad Rabie

One pleasant stop on my recent trip to Cairo was the American

University’s bookshop near Tahrir Square. It’s a treasure trove of books

on Egyptology and Egyptian fiction in translation. Among the titles I

picked up was the dystopian novel Otared by Mohammad Rabie.

This novel, originally published in Arabic in 2014 and published in

English in 2016 by Hoopoe, the fiction imprint of the American

University of Cairo, is a grim dystopian tale of Cairo in 2025.

After several botched revolutions in which the people repeatedly fail

to effect real social and political change, Egypt is invaded by a

foreign power. The army crumples, most of the police collude with the

occupiers, and the general public doesn’t seem to care. A small rebel

group decides to take back their nation, and one of its agents is former

police officer turned sniper, Otared. The rebels basically become

terrorists, deciding the only way to get the people to rise up is to

make life under the occupation intolerable, which means killing as many

innocent civilians as possible.

The world Rabie paints reminds me very much of the insane landscape in Paul Auster’s In the Country of Last Things, with its violence, its cruelty, and its bizarre customs (in Otared almost

everyone wears a mask) that begin to make sense once you learn more

about the world. Throw in a nightmarish disease that affects only

children, plus a national death wish, and you have a grim but compelling

read. No science fiction novel has gut punched me this hard for a long,

long time.

To continue reading, here is the original interview

January 17, 2017

Naguib Mahfouz, the man we all wronged

Original article was published on Madamasr here.

1988

As usual I sat at the front, close to the

blackboard because I’m short-sighted, and to the left, so the teacher’s

body wouldn’t hide what he wrote.

On that particular day the

teacher was absent. I don’t remember what he taught us or even who he

was, but I remember the substitute who came instead: An Arabic teacher

who had taught me the year before and whom I had understood very little

from. Instantly the memory of incomprehension came back, along with the

idea that he was a bad teacher. A few of my classmates surrounded him,

but he didn’t seem to care for the mess, the shouting or the kids

standing around him, or even for the kids sitting like me, chatting with

their neighbors.

Suddenly I heard someone ask him about Naguib Mahfouz,

who had won the Nobel Prize a few days before. I’d heard about it in

the news and what he did wasn’t a mystery to me — I knew he was a

novelist and I knew of the prize-winning novel, but I didn’t remember

who had told me.

As if he had been waiting for a question to bring

order to the class, the sub said: “If you want to know about Mahfouz,

you have to return to your seats.” Those around him did sit down, the

rest quickly followed, and we all listened.

He said that Naguib

Mahfouz was an atheist Egyptian writer who did not believe in God and

that he had written an atheist, infidel book, which said “God has died”

on the first page. He didn’t tell us the title of the book, of course,

fearing that we would read it and be tempted, and none of us asked for

further details because of his excessive harshness and the idea of

Mahfouz-ian heresy that was deserving of execution.

Maybe many of

us didn’t give much thought to the awful details related by the

substitute teacher, but something settled in my mind and refused to

leave. For years I kept asking around and looking for Mahfouz’s phrase,

“God has died,” in every magazine or newspaper I put my hands on. I

eventually learned that it appeared in his novel Awlad Haretna (Children of Gebelawi, 1959). I read a lot about it, but never succeeded in finding a copy.

1994

I

heard the news on the car radio. Unusually, my father was driving me to

school and he was listening very carefully: Naguib Mahfouz had been

stabbed while walking down the street, but he hadn’t died and was in a

stable condition in hospital.

Dozens of images came to my mind of

his turtleneck sweater, his neutral grey jacket, his slow walk and his

back bent under the brunt of something I didn’t comprehend. I remembered

that I’d lazed around a lot and hadn’t yet finished all of his novels,

as I’d planned to do that year. Something told me that if I didn’t

finish, the man would die and it would be my fault.

It didn’t take

much intelligence to realize that the teacher who called Mahfouz an

infidel had something to do with what had happened that day. Disbelief

flies in the air and stabs with a sharp blade. The desire to enter

heaven, to purge an infidel society or to set the rules of Islam — these

are three of many motives driving that stabber or other potential

stabbers, and it all starts in school when a person we trust, whom our

parents also trust, tells us without doubt that Mahfouz is an infidel.

I was still faced with a dilemma — I had yet to find Children of Gebelawi.

Perhaps I’d have to skip it, but I didn’t want that. For some reason

I’d decided to read Mahfouz by order of publication date, but my

terrible mistake was to neglect his short stories, so I only read them

later. Anyway, the absence of Children of Gebelawi from the shelves of our small library was an inescapable stumbling block.

1996

One of my friends was holding a copy of Al-Tariq

(The Search, 1964) and saying: “Mahfouz, that infidel!” We met at a

bookstand in Heliopolis, and he pulled the book from its place and put

the stigma of disbelief on the man, just like that. The stabbed man was

still in recovery, but the blasphemy accusations never ceased, even from

a young man my age who drank beer, smoked hashish and listened to heavy

metal.

We proceeded together toward downtown Cairo, walking a

long way before he took his leave and left me at Taalat Harb Square.

There, at one of the bookstands, I finally found Children of Gebelawi

— and in an unusually large size. The vendor handed it to me with a

beautiful smile and said: “Absolute infidelity!” This was getting

boring.

I went home and started reading the book, fell asleep

three hours later from fatigue, then woke up after dawn and continued to

read. When I read that Gebelawi had died, I was shaking.

***

But this did not start in the 1980s.

It’s said that when Thartharah fawqa al-Nil

(Adrift on the Nile) was published in 1966, military commander Abdel

Hakim Amer was infuriated by its descriptions of hash-smokers’

gatherings, possibly somehow reading it as slandering his person. It’s

also said that he called Gamal Abdel Nasser and said Mahfouz should be

imprisoned, to which Nasser responded: “How many Mahfouzes do we have,

Amer?”

The story is clearly false. It’s one of those stories “the

Egyptian state” (that complex and mysterious phrase) spread to put

Nasser in a good light and everyone else in a bad light. It reeks of the

Egyptian state not only because it presents Nasser as aware and

understanding, but also because it treats Egyptians — in this case

Mahfouz — as chess pieces manipulated by the state to tell stories with a

specific purpose and for complete control over the board, attributing

absolutely no will or choice to the pieces themselves.

But this

wasn’t the state’s only interaction with Mahfouz. It’s also said that

Nasser once asked journalist Mohamed Hassanein Heikal about Mahfouz’s

next work, and Heikal responded laughingly that he was about to publish a

novel by the author that would “bring disaster” in Al-Ahram. “Only to

you,” Nasser told him. I have no doubt that both stories come from the

same person. Nasser has the same quick wit in both, and in both the

narrator dismisses Mahfouz as a chess piece to be shamelessly

manouvered.

Stories about the state’s maltreatment of Mahfouz are many. They include harassment from Al-Azhar University because of Children of Gebelawi, forcing him to resign as head of the censorship authority. They include the censor’s brutal treatment of Karnak Café

(1974), cutting so much that it became riddled with plot-holes and

appeared more like a draft than a novel by Mahfouz at the height of his

craft and creativity. They include Anwar Sadat’s insulting treatment of

him — and others — for signing Tawfiq al-Hakim’s 1972 petition

denouncing the state of “no war and no peace” since Israel occupied

Sinai in 1967. And there are stories about security reports that

criticized Mahfouz for talking about “democracy” and other heresies that

threatened the Egyptian state.

2016

On social media website Goodreads, readers trade their views about books. On the Karnak Café page,

I was surprised to find that someone wrote that it’s the best book he

had read by Mahfouz, and that he personally envied Farag for what he

did.

The name Farag does not appear in the novel. It’s the name of the man who raped Souad Hosni’s

character in the film of the book, in a scene where we see her in total

breakdown, degraded, afraid and wishing for death because of the

brutality she’s confronted with, a scene that depicts rape as an

atrocious act against the victim, and a crime not only against the

victim, but against the country itself.

Maybe the commenter

imagined himself raping Souad Hosni. Mahfouz did not write the details

of the rape in the novel, but described it metaphorically in a single

line, leaving the rest to the imagination of the reader who lived

through that awful era of Egyptian history, and was familiar with what

was going on. Or perhaps the censor removed part of the account. We’ll

never know.

What saddened me was that the commenter didn’t notice

the plot-holes and confusion obvious to anyone reading the novel with

care, only seeing the rape incident as an act to be envied.

2014

Here’s

a story I never get tired of telling. I was attending an event in

Mansoura, in a large theater where some veteran actors were preparing to

read selections from Mahfouz’s Ahlam fatrat al-Naqaha (Dreams

of the Rehabilitation Period, 2004). Helmy al-Namnam (then a

representative of the Culture Minister) was speaking onstage about the

connection between Mahfouz and Egypt getting rid of the Muslim

Brotherhood a few months before. He said the knife that stabbed the

author was close to stabbing Egypt itself. He was cleverly tying

together the fates of Mahfouz and Egypt, alive and timeless, now and

forever.

Namnam then left the stage and the actors went on, each

reading a “dream,” each with their own style and voice. It seems the

person who chose the texts was smart, as half of the “dreams” read

included harsh criticisms of the Egyptian state, of a ruler who is a

fraud, a thief, an embezzler, an oppressor and who treats Egyptians like

chess pieces to move as he pleases, without care for their will or

desires.

2016

The same year again. On the

sidelines of the International Prize for Arabic Fiction, on a panel I

participated in, an Egyptian reacted sharply when I criticized how

Egyptians dealt with their colonizers. Angrily, she asked me not

interfere with history, not to mess with it, and unhesitatingly used the

example of Mahfouz, who “told the history” of Egypt in his novels.

The first thing that came to my mind was Mahfouz’s Zaqaq al-Midaq

(Midaq Alley, 1947), which was written when Egypt was still under

British occupation yet has no depiction of the Egyptian resistance, even

though the freedom fighter is ubiquitous in television, movies and

books about that era. I thought of citing Midaq Alley and

Mahfouz’s dismissal of the “freedom fighter,” maybe because he thought

the resistance was not serious, not enough to warrant the label, or

maybe because he was writing a novel not a history book, writing down

his view not “telling the history” of Egypt. But I chose to stay silent.

It was obvious the woman had not read the book that the panel was

about. It also seemed she had never read a word by Mahfouz.

1988

The

Egyptian state was in crisis, as usual. A weak economy, meager

industry, endless fights, a “democracy” with one party monopolizing

everything and Hosni Mubarak, who knew almost nothing of what was

happening around him, earning an enduring nickname: “la vache qui rit”

(the laughing cow). If not for a few smart advisors, it would have been a

disaster for all. Suddenly, everyone got a surprise: Naguib Mahfouz had

won the Nobel Prize. The first Arab, the first Egyptian, and not in a

scientific field but a creative field that everyone finds mysterious and

attractive.

Mahfouz instantly became a star and the state decided

to forget the grudge it bore with this old chess piece, but without

forgetting the role it gave him. Indeed, it planned to make him the

best, most active piece in the coming years: massive praise in

newspapers, endless articles, countless titles (“Egypt’s fourth

pyramid,” “the Arabs’ Nobel,” etcetera), magazine pullouts, books and

the Order of the Nile awarded by Mubarak — the highest praise the state

can offer a chess piece.

Mahfouz, intelligently, accepted all this

with contentment. An elderly man cannot face the Egyptian state. Even a

young man full of enthusiasm can’t. I think he thought it was all

serving his literature in some way, that the state’s interest in him

would create wider readership for his work.

He only hoped to

spread his word more, and the state hoped to put itself in a good light,

betting on the idea that Egyptians don’t read, an idea it planted in

everyone’s mind years ago: books will ruin your head, drive you mad, get

you arrested. In the end, Mahfouz’s hope didn’t materialize but the

state’s plan worked to completion.

2016

Yes, a third time. It was a dark year.

The fallout of novelist Ahmed Naji’s

case is endless, even after his recent release, because he “violated

the decency” of a citizen with his writings. Part of this fallout was an

Egyptian prime minister announcing that Mahfouz had also “violated

public decency” with his Cairo Trilogy (1956-7), and he was not tried

then only because no one presented a case against him, but he was still a

criminal in the eyes of Egyptian law. If Mahfouz was alive today, he

added, he would have been tried and sentenced. Rejoice, Naji — your name

was mentioned the same sentence as Mahfouz, you were accused of the

same thing and if he were alive you could have been cellmates.

It

was truly a rare moment. The Egyptian state announced its secret view of

Mahfouz, the chess piece used for years against his will. Such moments

come after the state has an overwhelming triumph, as we see in every

corner in Egypt right now: no one objects, no one opposes, whoever

speaks is a traitor, whoever writes is immoral, whoever comments must be

tried and whoever thinks is an infidel. Intellectual terrorism with

every sentence and every thought. Nothing can stop the Egyptian state’s

holy march. It hasn’t beaten the other chess player; there is no other

player. The state has defeated the chess pieces themselves: Mahfouz and

all other Egyptians.

But the state has not been the only one to

wrong Mahfouz. We have all wronged him: when we called him an infidel,

envied Farag, claimed Mahfouz “wrote the history” of Egypt and called

for his imprisonment. We, fellow oppressed chess pieces, wronged someone

who wrote for us and showed us everything that was inside him, all his

puzzlement, questions, doubt, faith and the love with which he replaced

everything. We wrong him more than the state does, because we never read

what he wrote.

___________________________________________________________

This piece originally appeared in Arabic. It was translated by Ahmed Bakr.

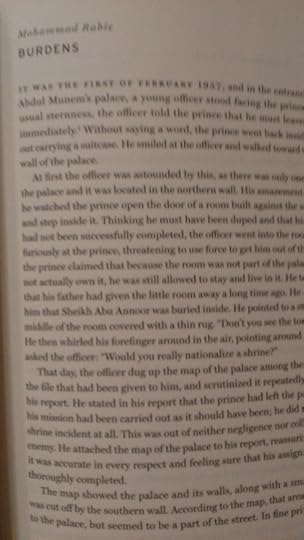

July 26, 2016

Many thanks to Mr. Mohamed El-sawi for his touching

translation...

Many thanks to Mr. Mohamed El-sawi for his touching

translation of my short story “Burdens”.

Burdens was published in the issue No. 11 of The Common

magazine, with several other translated short stories and images from Arabic authors

and artists.

You can find a link here to get your copy of The Common.

July 24, 2016

Completely horrific and painfully plausible: Mohamed Rabie’s Otared

By: Lara El Gibaly

As a child, I was struck by the myth of Prometheus, whom, as

punishment for stealing fire from mount Olympus to bestow it upon

mankind, is condemned to an eternity bound to a rock with an eagle

descending upon him every day to gnaw at his liver. At nighttime, his

liver regenerates, and, come morning, the eagle descends upon him again

in a never-ending cycle of pain and suffering.

I imagined this to

be an unfathomably torturous ordeal, one that could not possibly find

parallels in our human world, until I read Mohamed Rabie’s Otared (2015, Dar Al Tanweer).

Shortlisted

for the 2016 International Prize for Arabic Fiction, this dystopian

novel, Rabie’s third, is set between 2011 AD and 2025 AD (with a brief

chapter in 455 AH) and spares no effort, no grotesque detail no matter

how outlandish or profane, to inflict the utmost suffering on its

readers. And it does so with insight, humor, and — amid the muck, grime

and endless bloodbaths — a surprising amount of grace.

We begin

our descent into the inferno in the year 2025. Egypt is under occupation

by an ambiguous mercenary group that goes by the name of the Knights of

Malta. Cairo has been divided into an occupied East and liberated West.

In the midst of the chaos, lawlessness and daily horrors, our

protagonist Ahmed Otared leads a battalion of snipers comprised of

former police officers stationed atop the Cairo Tower as part of a

secret resistance force.

But nobody seems to care.

The

novel’s gruesomeness stems not so much from the perverse crimes we see

the characters commit, against themselves and others, but from the

suffocating sense of apathy and moral ambiguity that pervades. In this

dystopian future, the general public has become so desensitized to

violence that they walk calmly by as Otared picks off his victims one by

one with calculated efficiency or showers them with bullets

indiscriminately in one of his many killing sprees. From his

advantageous position looking down on the city, he muses that he is an

angel of mercy, that his task is great and noble, for he is putting

hundreds and thousands out of their misery, sparing them the inane

tortures of their daily existence.

I must admit that at certain

moments during my reading experience, I wished Otared would jump out of

the pages and put a bullet through my skull as well, which is, no doubt,

exactly the effect the author intended.

As the novel unfolds, our

protagonist is ordered to leave his Cairo Tower post for the first time

in two years. The city is a wasteland, and he must pass under the

October 6 Bridge in order to get downtown. He pays the gatekeepers the

fee for safe passage (an unopened pack of cigarettes) and enters the

underbelly of the beast. He passes through an informal market of bits

and bobs and has sex under the bridge with a young prostitute (sex work

is now legal under the rule of the Knights of Malta) who menstruates all

over him and whose fake glass eye pops out mid-coitus. Welcome to Cairo

2025.

But the gaping eye-socket of the menstruating woman is only

the beginning. We then see a man urinate on passersby before hanging

himself from a bridge, as the urine-soaked public stone him to death. We

see a gang of homeless youth rape an injured woman until she falls dead

in their arms, mid-thrust. We watch as a young man carries a toddler

through a field of corpses, turning her face towards each one in an

attempt to identify her lost father. We follow the dog-man and his pack

of street dogs that guide him with their howls to unburied corpses,

which he gathers in his wheelbarrow. We’re invited to eat a miscarried

fetus left on a dining table. We witness the gradual monstrous

transformation of a young girl suffering from an ailment which causes

all her orifices to seal themselves shut, until she is nothing but an

isolated lump of smooth flesh.

But the novel is not just a parade

of attractions at a house of horrors. It is also a collection of astute

observations and cynical musings on the political happenings of recent

years. The author imagines a series of bloody political events in the

years following the 2011 revolution and the 2013 Rabaa al-Adaweya

massacre: the Manshiya massacre of 2016, in which 4000 people were

killed over the span of six days; the dispersal of the 2019 sit-in at

Al-Azhar Park and Ain Shams University; and the 2025 campaign for the

return of the police to their former glory, dubbed “The police return on

police day.” All completely horrific, and all painfully plausible.

At

one point, we eavesdrop on former police officers, gearing up for an

upcoming battle, as they mock the “martyrs” of the 2011 “revolution,”

calling it instead the January disturbance. One officer offers to recite

an anti-regime poem he heard back in the days of the disturbance, and

his colleagues heave with uncontrollable laughter at his farcical

performance. This desecration of the memory of January 25 and its fallen

was particularly painful to read, but the fact that it was written

feels very necessary. It is a glimpse into a world where nothing is

sacred, where the past is a series of events meant to set us up for a

bleaker future — a world we seem to already partially inhabit.

“Maybe someone will even write a poem at the end of today!” says one officer sarcastically.

“Maybe,” his commander replies. “The idiots are aplenty.”

While

Rabea’s writing is wonderfully rhythmic and relatively simple, I would

fault it for being overly descriptive, and at times a bit repetitive

(someone with more time and a stronger psyche than me should undertake a

quantitative analysis of the writing and make a count of the number of

times the word “suffering” and its derivatives — torture, torment, pain,

agony — are used). Although the repetition is clearly a device used to

convey the long drawn-out days of suffering (one page literally consists

of the names of Otared’s victims and how he killed them, in paragraph

format, with no line breaks) and the repetitively nightmarish thoughts

of its protagonist, at times it feels a bit forced. Otared himself

adopts a Promethean logic: “Hell is eternal, I know that well enough,

and this hell will end so that another can begin. It may be a past hell,

or a future one, or the very same one. We may relive the same events

twice, thrice, or four times. So it is that our skin is burnt in order

to be replaced with new skin for the burning.”

As the novel comes

to its final third, the author makes a big reveal, one that puts into

perspective the gruesome images he has been forcing us to observe. Yet

the book continues for almost 100 pages more, and these last sections

are less powerful. They do not move the plot forward significantly, nor

do they add an interesting perspective on the novel’s hellish world.

They seem designed purely to draw out the suffering of both characters

and readers for as long as possible, and I feel the book could have done

without them.

That having been said, this is a work of daring

honesty that probes the darkest corners of our subconscious minds,

fishing out the basest of human desires and instincts and presenting us

with them in blood-spattered glory. The plot is fast-paced and gripping,

and the new and innovative horrors the author manages to concoct left

me turning its pages with excitement, trepidation and a faint sense of

nausea in my gut.

As with other recent works set in a post-apocalyptic Cairo (Ahmed Naji’s 2014 work Using Life

comes to mind), Otared contains a number of magnificently cathartic

images that play out what I imagine to be every Cairo dweller’s unspoken

shared desire for destruction. The Central Bank of Egypt building

completely disintegrates for no apparent reason. The Baron Palace is

overtaken by thousands of wild dogs and collapses under their canine

weight, and the statue of Ibrahim Pasha in Opera Square is reduced to

rubble. The inscription “Humanity has failed” is graffitied on the slab

of marble that once was its base.

Staring at it after a

particularly senseless battle in which crazed citizens bludgeoned each

other to death, our protagonist, the last man standing, wonders, “Where

do all the dead go? Where does one go if one dies in hell?”

This

is a question that recurs (what felt like) ad infinitum throughout the

book. What is worse: to suffer unknowingly, tortured by your

ever-present hope for a better future? Or to suffer knowing that you are

caught in a permanent cycle of suffering, that this better future will

never come, that your daily existence is your penance, that the

suffering never ends, it just shape-shifts, and that you must bear the

devouring of your liver by the eagle for all eternity?

Which is the harsher form of suffering? Probably the experience of reading this book.

If this article leaves you confused as to whether I loved or hated Otared

that’s probably because I can’t decide myself. It feels closest to

watching a train-crash happening in slow motion: you are horrified but

you can’t bring yourself to turn away.

I highly recommend Otared

to literary masochists and poetic self-flagellators, who actively want

to bring about a state of depression and self-loathing. Or to sinners

suffering from undefined guilt who are unsure how to repent. Or, in all

seriousness, to anyone who has a faint sense that something has gone

terribly wrong with our lives, our morality and our city, particularly

over the past five years. But turn its pages carefully. This book is not

for the faint-hearted.

Original article here

Mohamed Rabie’s novel #Otared - International Prize For Arabic...

Mohamed Rabie’s novel #Otared - International Prize For Arabic Fiction: 2016 Shortlist

Short interview about #otared in New York Times

“In

the turbulent months after the uprisings, when the promises of

democracy and greater social freedom remained elusive, some novelists

channeled their frustrations and fears into grim apocalyptic tales. In

Mohammed Rabie’s gritty novel “Otared,” which will be published in

English this year by the American University in Cairo, a former Egyptian

police officer joins a fight against a mysterious occupying power that

rules the country in 2025.Mr.

Rabie said he wrote the novel in response to the “successive defeats”

that advocates of democracy faced after the 2011 demonstrations that

ended President Hosni Mubarak’s 30-year rule. While there are parallels

to present-day Egyptian society, setting the story in the near future

allowed him to write more freely, without drawing explicit connections

to Egypt’s current ruler, he said in an email interview translated by

his Arabic publisher.“

Full article here

June 12, 2016

No one really understood what had just happened.

No one really understood what had just happened.

May 28, 2016

مطار ميونخ، صحراء جرداء لا بشر فيها ولا أشياء.

مطار ميونخ، صحراء جرداء لا بشر فيها ولا أشياء.

Mohammad Rabie's Blog

- Mohammad Rabie's profile

- 23 followers