Michael Roberts's Blog

November 26, 2025

UK: the ‘make or break’ budget

The UK had an apparently important financial event today. The Labour government’s finance minister (called the Chancellor of the Exchequer, a feudal royal term), Rachel Reeves presented the government’ s tax and spending measures for the year (and years ahead).

It was billed as a ‘make or break’ budget for the Labour government which is languishing badly in the opinion polls – its share of support has halved from an already low election result of 34% in July 2024 when Labour won a landslide of seats. The anti-immigration, pro-Brexit Reform party is now polling near 35%, with the Conservative party also down in the teens.

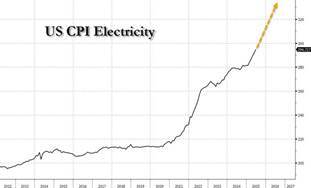

The Labour government’s 18 months in office has been nothing short of disastrous. First, it launched a series of vicious cuts in welfare spending: dropping the annual winter fuel allowance for pensioners just at a time when energy prices reached an all-time high. Then it announced cuts in benefits for disabled people. And just so another section of vulnerable Britons were not missed, it announced the maintenance of the ‘cap’ on child benefits to families with no more than two children. This meant that any family with more than two kids was badly hit. There are already 4.3m children officially in poverty in the UK and the cap would drive that poverty level to new heights.

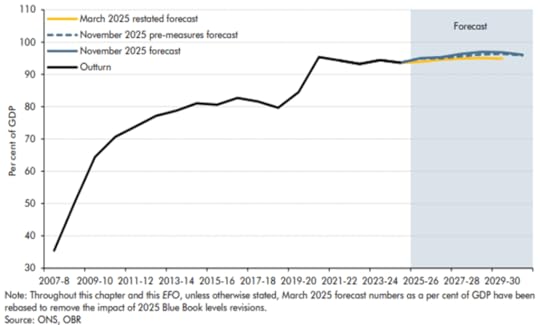

PM Starmer and Reeves were wedded to the idea that the government had to fill a ‘fiscal black hole’, namely running an annual deficit of spending over revenue that would drive up the public sector debt, already 100% of GDP.

To stop that rising, the ‘black hole’ had to be filled with tax rises and spending cuts, so that holders of government bonds (banks, pension funds, insurance companies, foreign investors etc) would not sell bonds and/or demand higher interest to buy them. The last government that intended to raise spending and finance it by ‘printing’ money (by the Bank of England) was the ill-fated and very short reign of Conservative PM Liz Truss. The bond market sold off and the pound slumped. Truss and her Chancellor were ousted by their own party within days.

On gaining office, Reeves and Starmer assured the ‘bond vigilantes’ (as the City of London is often called) that Labour would not be spendthrift but instead would close the ‘fiscal gap’ and keep public debt under control. And they did what would appeal to the vigilantes the most: austerity for the poor and subsidies and deregulation for the rich. This was a political disaster and under pressure from their own MPs, the Labour leaders have rowed back on all those cuts. This November budget finished that 180 degree turn by announcing the end of child benefit cap.

However, the problem remained that the government still thought it needed to meet the bond market’s demands. How to fill the ‘fiscal hole’? The trouble is that this hole is imaginary – it’s in the minds of the government and the financial sector; and it varies in size depending on how fast the British economy is growing. The faster it grows, the more tax revenues rise and spending falls on welfare and unemployment benefits.; and so the hole gets smaller. But here’s the rub. The UK economy is stagnating, more or less, in real terms, the only growth is in nominal GDP, in other words, in price inflation. The UK has the highest inflation rate among the top G7 economies. As a result, money lenders have kept their interest rates high in order to maintain their real gains and so small companies and household mortgage holders are suffering badly.

The body that oversees the credibility of government tax and spending measures, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), has finally recognised that the UK economy is crawling along. Having previously optimistically forecast an economic growth rate that was never achieved, the OBR has now reduced its forecast for real GDP growth from 1.8% a year to 1.5% for the next few years. If those new forecasts were right, it would mean that government would not get enough tax revenues to match spending.

But it was not true that welfare spending was ‘out of control’. Welfare spending has held roughly steady as a share of the economy since 2007. Total welfare spending in Britain in 2025-26 is estimated to be 10.8 per cent of GDP. That’s just 0.8 per cent of GDP higher than in 2007-08, and spending has actually fallen fallen by 1.2 per cent of GDP since 2012-13. Nevertheless, big business and the financial sector still demand welfare cuts and oppose tax rises – at least for the rich.

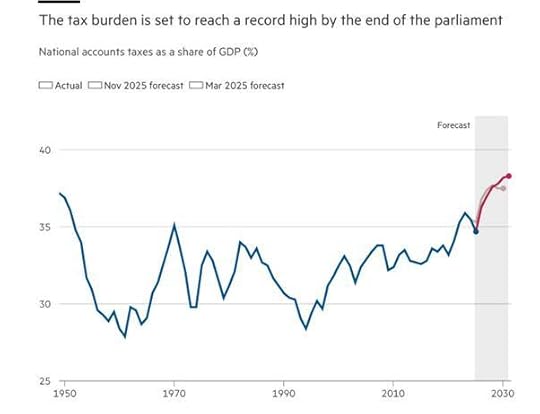

So what has Reeves done? In order to ‘fill the fiscal hole’ to keep government debt from rising, she has not raised taxes on the rich; she has not raised the tax rate for the richest earners; she has not introduced a wealth tax on the super-rich. Instead, she has raised a ‘stealth tax’ on average earners which she admits will “hurt working people. I won’t pretend otherwise.” So the tax burden as a share of national GDP will reach an all-time high by the end of the Labour government’s term of office in 2029 (if it lasts that long).

In order to cover the cost of the reversal of its previous welfare cuts, Reeves has also raised taxes on gambling; introduced a mansion tax on very expensive properties (ie valued at over £2m) and increased taxes on dividends and capital gains. But the Resolution Foundation thinktank reckons that, even with the “mansion tax”, someone with a £5m home in central London will still pay less local tax as a proportion of the value of their home than someone with an average home in far north Sunderland. Moreover, most of these increased taxes on richer Britons are not starting until near the end of this parliament, while the hit to average households will be from April next year.

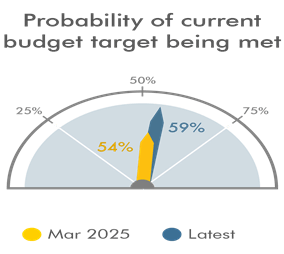

And the likelihood of meeting even the government’s fiscal targets are low. As the OBR says: “the economic outlook depends on uncertain judgements on the paths for productivity, inactivity, and net migration. The fiscal forecast also remains highly sensitive to movements in interest rates and inflation given the level of debt.” The OBR puts fiscal success at just 59%.

This is no ‘make or break’ budget, except perhaps for the Starmer-Reeves government in meeting the demands of the City of London. For most Britons, the British economy is already broken.

Let me remind you. Britain has the highest inflation in the G7; the highest electricity prices in the OECD; rising unemployment hitting 5%, stagnating real incomes since 2019; rising inequality and poverty (with 3m-plus living off ‘food banks’); the widest regional disparities in Europe; the lowest benefits relative to average wages in the OECD; public services in tatters; NHS waiting lists at a record high; local governments going bankrupt; care workers exploited by private companies and the government; more ‘social housing’ being sold to private landlord companies than are being built; water and energy companies making huge profits, while sewage pours into rivers and the beaches; and the prison and justice system paralysed.

None of this Humpty Dumpty British economy will be put together again by tinkering with a few tax measures in order to fill an imaginary fiscal hole. Speaking to Labour MPs before the budget, Reeves said that “We know there is more to do. That’s why we are investing £120bn more than the previous government in national infrastructure, cutting red tape and unnecessary regulation for businesses, introducing a new planning bill and securing new trade deals across the globe.” But this £120bn is not public investment; the government is only spending just £7bn in public funding of projects; the rest is supposed to come from the private sector through the much discredited public-private partnerships that land hospitals, schools, and other projects in permanent debt to private equity companies. Even that figure is way too small – an LSE research study reckoned that up to £60bn a year was needed to repair the economy and its people.

The government is not increasing the funding of local councils in real terms. It is not meeting the urgent needs of the National Health Service, the schools and universities. It is not going to build anywhere near enough ‘affordable housing’ because there is no public building programme, just measures of deregulation of planning and environmental controls over private developers. On the other hand, ‘defence’ spending is set to rise dramatically over this parliament in order to protect the nation from Russian invasion.

Make or break? Broken now and not being remade.

November 23, 2025

COP 30: it’s no joke

The usual joke about the United Nations Climate Change Conferences (COPs) is that each one is a ‘cop-out’. Each time there is a failure to agree on ending fossil fuel production as the source of energy, even though it is now well established that carbon and other greenhouse gas emissions come mainly from the use of fossil fuels. Each time there is a failure to agree to significant planned and implemented reductions in emissions from all sources, production, transport, wars etc. Each time, there is a failure to agree any significant reversal of unending deforestation, the polluting of the seas and the accelerating extinction of species and diversity.

The joke of saying it is a ‘cop-out’ has now worn thin to the bone. COP30 was no joke, even if the ‘agreement’ reached was one. Time has run out. The world is hotting up to the point of tipping into irreversible damage to humanity, other species and the planet itself.

Harjeet Singh of the Satat Sampada Climate Foundation, said: “Cop30 will go down in history as the deadliest talkshow ever produced.” Negotiators at Belem, Brazil “spent days discussing what to discuss and inventing new dialogues solely to avoid the actions that matter: committing to a just transition away from fossil fuels and putting money on the table.” But the core issue of a “transition away from fossil fuels” was dropped as the fossil fuel nations and most of the Western powers blocked it. Even the weak watered down idea of a ‘roadmap’ to a transition was opposed.

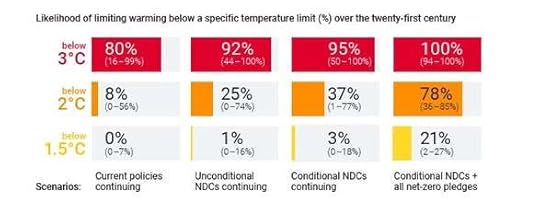

Also at stake was the question of how countries should respond to the fact that current national climate plans, known as nationally determined contributions (NDCs), would lead to about 2.5°C of global temperature above preindustrial levels, far above the 1.5C limit target set by the 2015 Paris COP agreement. The COP30 ‘agreement’ was to “continue talking about” the large gap between countries’ targets and the carbon emission cuts necessary to stay within 1.5C.

The climate scientists at COP30 made it clear – yet again. Emissions must start to bend next year, they say, and then continue to fall steadily in the decades ahead: “We need to start, now, to reduce CO2 emissions from fossil-fuels, by at least 5% per year. This must happen in order to have a chance to avoid unmanageable and extremely costly climate impacts affecting all people in the world.” Emission reductions need to be accelerated: “We need to be as close as possible to absolute zero fossil fuel emissions by 2040, the latest by 2045. This means globally no new fossil fuel investments, removing all subsidies from fossil fuels and a global plan on how to phase in renewable and low-carbon energy sources in a just way, and phase out fossil fuels quickly.”

The scientists added that finance – from developed to developing countries – is essential for the credibility of the 2015 Paris Agreement aimed at keeping the rise in global temperature no higher than 1.5C. “It must be predictable, grant-based and consistent with a just transition and equity,” they said. “Without scaling and reforming climate finance, developing countries cannot plan, cannot invest and cannot deliver the transitions needed for a shared survival.” COP30 got an agreement to increase funding from the rich countries to the poor – but the increased funding would be spread over the next ten years, not five years as before!

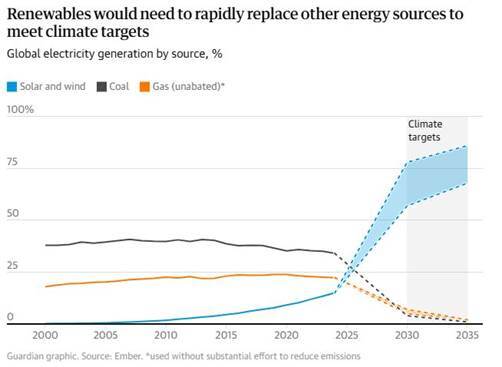

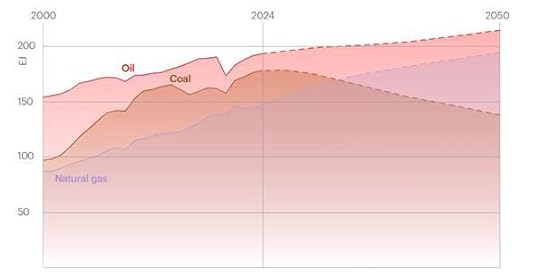

Instead , global oil and gas demand is set to rise for the next 25 years if the world does not change course, according to the International Energy Agency in its latest report. Greenhouse gas emissions are still rising despite ‘exponential’ growth of renewables. Coal use hit a record high around the world last year despite efforts to switch to clean energy.

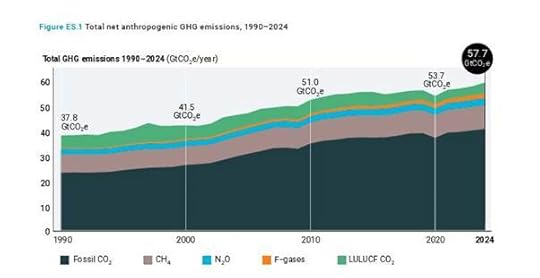

So global CO2 emissions will rise, not fall. Annual global energy-related CO2 emissions will rise slightly from current levels and approach 40 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide per year in the early 2030s, remaining around this level through to 2050. Emissions may fall in advanced economies, most substantially in Europe, and also decline in China from 2030 onwards, but they increase elsewhere.

And it’s not just carbon emissions. Methane is a greenhouse gas 80 times more powerful than carbon dioxide, and is responsible for about a third of the warming recently recorded. At previous ‘cop-outs’ it was agreed to a cut in methane emissions of 30% by 2030. Yet methane emissions have continued to increase. Collectively, emissions from six of the biggest signatories – the US, Australia, Kuwait, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Iraq – are now 8.5% above the 2020 level.

So the world is getter hotter. This year and the last two years were the three hottest years in 176 years of records, And the past 11 years, back to 2015, will also be the 11 warmest years on record. Tipping points (irreversible) are being reached: glaciers melting; forests disappearing; wildfires, floods and droughts increasing. The world is heading for 2.8°C warming, as the latest UN report reveals climate pledges are ‘barely moving the needle’.

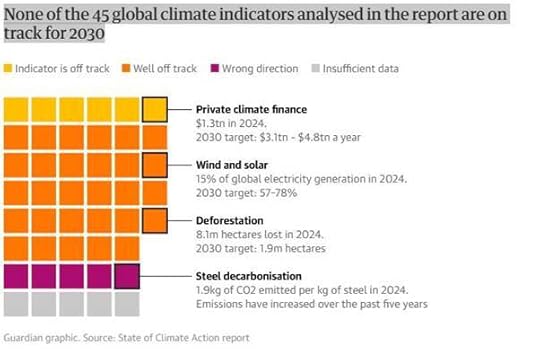

The UNEP’s ‘Emissions Gap Report 2025: Off Target’ finds that available new climate pledges under the Paris Agreement have only slightly lowered the pace of the global temperature rise over the course of the 21st century, leaving the world heading for a serious escalation of climate risks and damages. Fewer than a third of the world’s nations (62 out of 197) have sent in their climate action plans, known as nationally determined contributions (NDCs) under the Paris agreement. The US, the country that is the biggest emitter per person, has abandoned the process – the US did not turn up at COP30. Europe has also failed to deliver. None of the 45 global climate indicators analysed are on track for 2030.

Levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere soared by a record amount in 2024 to hit another high, UN data show. The global average concentration of the gas surged by 3.5 parts per million to 424ppm in 2024, the largest increase since modern measurements started in 1957, according to the report by the World Meteorological Organization.

Several factors contributed to the leap in CO2, including another year of unrelenting fossil fuel burning. Another factor was an upsurge in wildfires in conditions made hotter and drier by global heating. Wildfire emissions in the Americas reached historic levels in 2024, which was the hottest year yet recorded. Climate scientists are also concerned about a third factor: the possibility that the planet’s carbon sinks are beginning to fail. About half of all CO2 emissions every year are taken back out of the atmosphere by being dissolved in the ocean or being sucked up by growing trees and plants. But the oceans are getting hotter and can therefore absorb less CO2 while on land hotter and drier conditions and more wildfires mean less plant growth.

Reductions to annual emissions of 35 per cent and 55 per cent, compared with 2019 levels, are needed in 2035 to align with the Paris Agreement 2°C and 1.5°C pathways, respectively. Given the size of the cuts needed, the short time available to deliver them and a challenging political climate, a permanently higher rise in global temperature is unavoidable before the end of this decade. The Paris target is as dead as the people and species dying from climate change.

Indeed, rising global heat is now killing one person a minute around the world, a major report on the health impact of the climate crisis has revealed. The report says the rate of heat-related deaths has surged by 23% since the 1990s, even after accounting for increases in populations, to an average of 546,000 a year between 2012 and 2021. In the past four years, the average person has been exposed to 19 days a year of life-threatening heat and 16 of those days would not have happened without human-caused global heating, the report says. Overall, exposure to high temperatures resulted in a record 639bn hours of lost labour in 2024, which caused losses of 6% of national GDP in the least developed nations.

The continued burning of fossil fuels not only heats the planet but also produces air pollution, causing millions of deaths a year. Wildfires, stoked by increasingly hot and dry conditions, are adding to the deaths caused by smoke, with a record 154,000 deaths recorded in 2024, the report says. Droughts and heatwaves damage crops and livestock and 123 million more people endured food insecurity in 2023, compared with the annual average between 1981 and 2010.

Why are the targets for reducing emissions not being met or now even agreed? The answer is money. Despite the harm, the world’s governments provided $956bn in direct fossil fuel subsidies in 2023. This dwarfed the $300bn a year pledged at the UN climate summit Cop29 in 2024 to support the most climate-vulnerable countries. The UK provided $28bn in fossil fuel subsidies in 2023 and Australia allocated $11bn. Fifteen countries including Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Venezuela and Algeria spent more on fossil fuel subsidies than on their national health budgets.

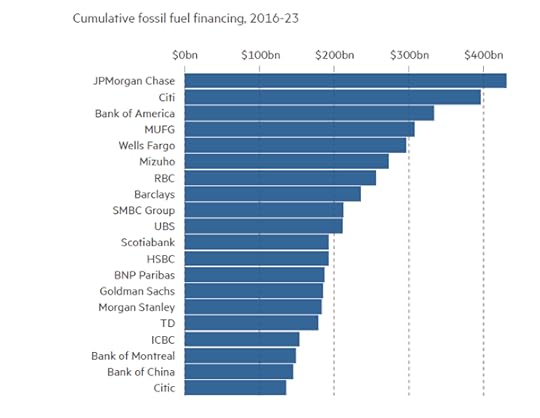

The world’s 100 largest fossil fuel companies increased their projected production in the year up to March 2025, which would lead to carbon dioxide emissions three times those compatible with the Paris climate agreement target of limiting heating to 1.5C above preindustrial levels, the report says. Commercial banks are supporting this expansion, with the top 40 lenders to the fossil fuel sector collectively investing a five-year high of $611bn in 2024. Their ‘green sector’ lending was lower at $532bn.

The reason for expanding fossil fuel production is that it is just much more profitable than switching to renewables. The problem is that governments are insisting that private investment should lead the drive to renewable power. But private investment only takes place if it is profitable to invest.

Profitability is the problem – in two ways. First, average profitability globally is at low levels and so investment growth in everything has similarly slowed. Prices of renewables have fallen sharply in the last few years. Ironically, lower renewables prices drag down the profitability of such investments. Solar panel manufacturing is suffering a severe profit squeeze, along with operators of solar farms. This reveals the fundamental contradiction in capitalist investment between reducing costs through higher productivity and slowing investment because of falling profitability.

Brett Christophers in his book, The Price is Wrong – why capitalism won’t save the planet, argues that it is not the price of renewables versus fossil fuel energy that is the obstacle to meeting the investment targets to limit global warming. It is the profitability of renewables compared to fossil fuel production. Christophers shows that in a country such as Sweden, wind power can be produced very cheaply. But the very cheapening of the costs also depresses its revenue potential. This contradiction has increased the arguments of fossil fuel companies that oil and gas production cannot be phased out quickly. Peter Martin, Wood Mackenzie’s chief economist, explained it another way: “the increased cost of capital has profound implications for the energy and natural resource industries”, and that higher rates “disproportionately affect renewables and nuclear power because of their high capital intensity and low returns.”

As Christophers points out, the profitability of oil and gas has generally been far higher than that of renewables and that explains why, in the 1980s and 1990s, the oil and gas majors unceremoniously shuttered their first ventures in the renewables almost as soon as they had launched them. “The same comparative calculus equally explains why the same companies are shifting to clean energy at no more than a snail’s pace today”.

Christophers quotes Shell’s CEO Wael Sawan, in response to a question about whether he considered renewables’ lower returns acceptable for his company: “I think on low carbon, let me be, I think, categorical in this. We will drive for strong returns in any business we go into. We cannot justify going for a low return. Our shareholders deserve to see us going after strong returns. If we cannot achieve the double-digit returns in a business, we need to question very hard whether we should continue in that business. Absolutely, we want to continue to go for lower and lower and lower carbon, but it has to be profitable.”

For these reasons, JP Morgan bank economists conclude that “The world needs a “reality check” on its move from fossil fuels to renewable energy, saying it may take “generations” to hit net-zero targets. JPMorgan reckons changing the world’s energy system “is a process that should be measured in decades, or generations, not years”. That’s because investment in renewable energy “currently offers subpar returns”.

The only way humanity has a chance of avoiding a climate disaster will be through a global plan based on common ownership of resources and technology that replaces the capitalist market system. Meanwhile, the cop-out continues.

November 16, 2025

Chile: another turn to the right?

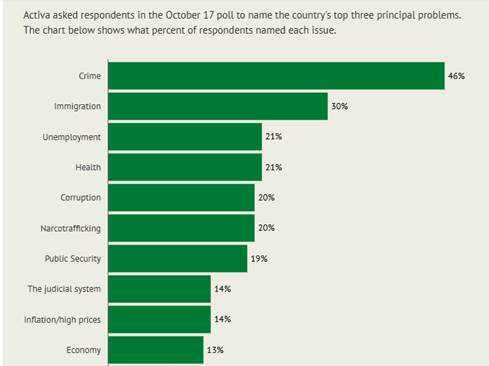

Chile has a general election today. Around 15m voters can take part in the first round to elect a new president, the lower house and half the seats of the senate. Incumbent President Gabriel Boric, who was elected in 2021, is constitutionally barred from seeking a consecutive second term. So all is up for grabs.

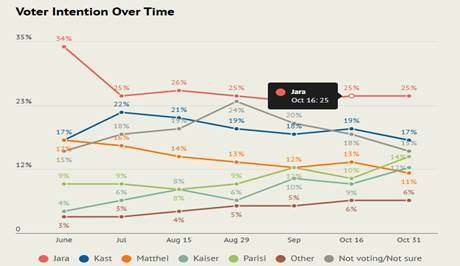

Boric was a former student activist who got a decisive victory in 2021. In a 56% turnout, the highest since voting was made voluntary, 35-year old Boric took 56% of the vote compared to ultra-right Antonio Kast’s 44%. But this time, the voter share could be the other way round. Although the leftist alliance led by Jeannette Jara of the Communist Party, who served as Boric’s labor minister, is ahead in the opinion polls, she will not get an outright majority in the first round as Boric did. And a collection of right-wing parties is likely to combine their vote and get Kast into the presidential office in the second round in December.

Chile is the richest country in Latin America as measured by GDP per head. It is a member of the OECD, the rich nations club, and in the (NAFTA-USMCA) trade bloc with Canada, Mexico and the US. As a result, its real GDP growth rate has generally been slightly faster than the rest of Latin America and so its successive governments have thus been relatively stable.

Many mainstream economists and political theorists often use this to claim that Chile is a ‘free market’ capitalist economic success story and consider Chile as the “Switzerland of the Americas”. But this apparent success story is only relative compared to other Latin American economies. Moreover, such gains have mainly gone to the rich in Chile. Income inequality is among the worst in the OECD, only surpassed by Brazil and South Africa. The income share of the bottom decile in Chile is one of the lowest in the world. Only a few countries, largely from Latin America, have lower income share accruing to the bottom decile of the distribution and this share has deteriorated in relative terms in the last 20 years.

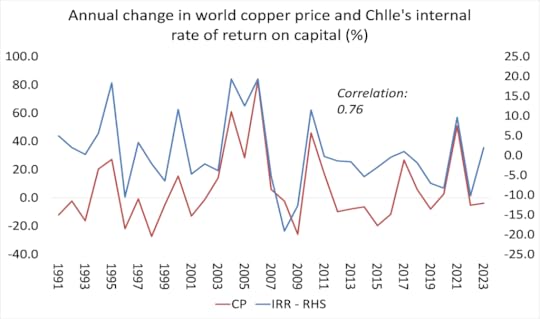

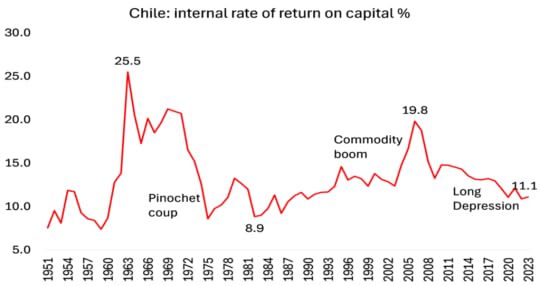

Chile’s relative economic success has always been based on its copper and mineral exports. The country has been the world’s top copper producer now for over 30 years, and close to 50% of the country’s exports come from copper-related products. The mining sector contributes 15% of Chile’s GDP and generates 200,000 jobs. If copper and mineral prices are high and rising, Chile’s economy does better and conversely. The profitability of Chilean capital has been driven by the copper cycle as the graph below shows.

Source: Penn World Tables 11.0 series

The neo-liberal period after the military coup by General Pinochet from 1973 and after the global slump of the early 1980s achieved a temporary rise in profitability, enabling the regime to maintain its control during the 1980s. Eventually, Chile returned to democracy in 1989, and the commodity price boom of the 2000s led to a new rise in profitability until the Great Recession of 2008-9.

Source: Penn World Tables 11.0

The fall in profitability after 2010 led to slowing growth in GDP, investment, incomes and a further squeezing of public services prior to the COVID slump. With COVID and the health disaster, there was a collapse in the economy, with the main impact falling on those with the lowest incomes and worst jobs. Copper prices jumped hugely when the pandemic slump ended, but then fell back by nearly 10% during the Boric presidency.

Why is the Leftist Alliance likely to lose? The main reason is that the Boric presidency failed to change the economic structure and the social inequalities in Chile. In recent decades, public services have been reduced, forcing people to use private profit operations. In particular, pensions are dominated by private sector companies. Most Chileans find their savings for retirement are just too meagre to fund a decent standard of living in old age. Replacement rates’ (ie pension income relative to average working income) in Chile are very low relative to other OECD economies. Amid high and rapidly increasing costs of living since the pandemic, alongside limited income growth and low pensions, many households have accumulated considerable amounts of debt. Taxes on the rich are small, so that income redistribution is lower than almost all OECD peers and many other poor economies.

The damage of the COVID pandemic on people’s lives and livelihoods was blamed on Boric, as it was on many incumbent governments during COVID. Boric did not take on the mining companies, but merely tried (and generally failed) to redistribute the largesse appropriated by capital somewhat more evenly. After the pandemic, inflation rocketed and the multi-nationals and the Chilean business sector, Congress and the media mounted an incessant campaign of attack. Boric’s popularity plummeted. Boric was blamed for everything, including rising crime rates and increased immigration from Venezuela as millions left that country in the search for a better living in Chile. These issues now seem to dominate the electorate, rather than the economy and the cost of living.

The main right-wing candidate in the election, José Kast, is pitching hard, Trump style, on these issues. Kast, an admirer of the former dictator Pinochet, opposes rights to abortion and same-sex marriage. He wants to build a Trump-style wall – called Escudo Fronterizo (Border Shield) –of ditches and barriers along Chile’s northern border to keep immigrants out. “Chile has been invaded … but this is over,” Kast has declared.

So it seems likely that another centre-left government in South America will eventually fall to the hard right, as it has recently in Bolivia and perhaps soon in Colombia and Peru. As Javier Milei put it on winning Argentina’s recent mid-term elections, Latin America was undergoing a “liberal renaissance.” Expressing hope that elections in several big nations over the next year would return conservative governments, Milei said: “We hope the blue wave continues. We’ve had enough reds. The world today is heading towards a different format, in which there will be a bloc led by the United States, a bloc led by Russia and a bloc led by China. In this world order, the United States understands that its bloc is in America — and without doubt, we are its biggest strategic ally.”

November 13, 2025

HM 2025 part two – nature, rent, profit and AI

In this part two, I resume my review of the Historical Materialism conference in London with a look at some of the sessions on climate change, ecology and the impact of artificial intelliigence – as well as on the state of the world economy.

As the climate crisis worsens globally, naturally there were several sessions on how capitalism is destroying humanity, other species and the planet itself. There was a staggering turnout for the launch of a new book by Alyssa Battistoni called Free Gifts: capitalism and the politics of nature. Battistoni was there to present the ideas in her book, along with some expert discussants.

I have to say that I found it difficult to follow Battistoni’s arguments, although I was obviously in a minority as there appeared to be rapt attention to her presentation and with her answers to questions. But let me see if I can summarise what I think she was saying. Battistoni says that capitalism treats nature as a ‘free gift’ by default. Natural resources can be used without payment or replenishment, so they need not be priced. But capitalism, by treating nature as a free gift, stops us recognising that nature does have value. Critics of capitalism’s commodification of the world have misidentified the problem: it’s not that capital has ‘absorbed’ (commodified) all of life, but that it has ‘abdicated responsibility’ for so much of it.

This sounds profound, but I’m not so sure. Battistoni is puzzled by why capitalism has not commodified all of nature and some ‘gifts of nature’ remain ‘free’. I think the answer is clear. Nature is only commodified by capital if it is profitable to do so, and some parts do not look profitable (yet). Digging up coal or drilling for oil is very profitable, but using the sun or wind to generate electricity is not so much – the result is that fossil fuel production and use will continue under capitalism until it is no longer more profitable than renewable energy generation (see the latest IEA report).

I think probably the most insightful point made by Battistoni was her observation that, in fighting to save the planet and its species from uncontrolled destruction wrought by capitalism, we cannot return to “natural cycles” or patterns, or ‘reproduce the old’. “A constructive view of ecological reparations cannot be rooted in the appeals to an originary (sic) nature that lurk beneath many calls for the restoration of natural balance—or even for reconciling humanity and nature by suturing the “metabolic rift.” Even if carbon is removed from the atmosphere and temperatures stabilized, the disruption that warming has wrought on the planet and its beings is irreversible. If this is daunting, it is also unavoidable. There is no other planet on which we can make a world.”

In another session, Joel Wainwright launched a new book called The End: Marx, Darwin, & the Natural History of the Climate Crisis. I’m not sure what ‘the end’ referred to, but the gist of the book aimed to reveal the affinities that Darwin’s evolutionary theory of nature by adaptation had with Marx’s view of history. According to Wainwright, Marx dispensed with a teleological (ie inevitable) view of history, as expounded by Hegel, and instead reckoned that human social development was just as much dependent on ‘contingent’ human action as on objective laws. Darwin’s 1859 Origin of the Species was taken up by right-wing theorists to argue that human ‘progress’ was based on the inexorable ‘survival of the fittest’. Darwin repudiated this interpretation of his theory in his second great work of 1871, The Descent of Man. Similarly, Marx and Engels firmly rejected the Malthusian theory of overpopulation as an inexorable law that would keep the ‘unfit’ poor for always. Poverty was not due to ‘too many people’, but to workers being condemned at regular intervals to a ‘reserve army of labour’ as capital shed labour.

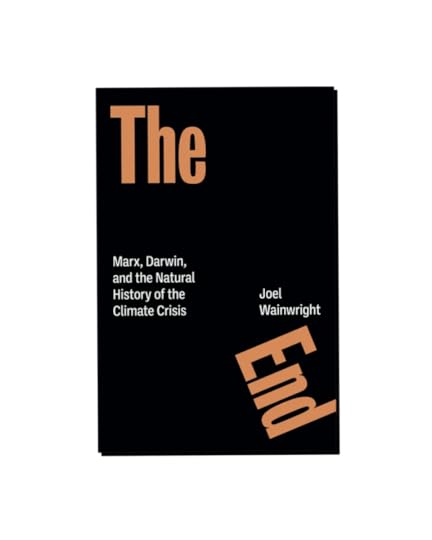

Over the years, we have been told by some Marxists that capitalism has changed its spots (unlike the leopard). It is no longer mainly to do with the exploitation of labour in production to get profits, but instead finance had taken over as the dominant mode of production, ie money makes more money without any exploitation of human labour. So now there is ‘financial capitalism’, not capitalism. Alternatively, there is ‘rentier’ capitalism or ‘extractive’ capitalism or ‘dystopian’ capitalism.

In one session at HM, rentier capitalism was the theme. Ryuji Sasaki, whom I believe is a student or colleague of Kohei Saito, the rock star Japanese Marxist ecologist, supported the concept of ‘rentier capitalism’. As he put it: “Most Marxist arguments are based on a narrow understanding of capitalism, which has led them to overlook the theory of rent.” Instead, Sasaki argued that “rentier capitalism represents the latest and most contradictory form of capitalism.” Apparently, profit in the form of rent extraction comes from ‘scarcity’, including ‘scarcity of labour'(?). To me, this theory seemed close to neoclassical marginalism, which argues that ‘factors of production’ (labour, capital, land), each get returns due to their relative scarcity. Sasaki did reject the alternative theory of rent extraction proposed by the self-proclaimed ‘erratic Marxist’, Yanis Varoufakis, who has recently argued in a book that capitalism in any form is ‘dead’ and has been replaced by what he calls ‘techno-feudalism’. This feudalism concept was repeated at the HM, with one session modifying it into ‘neo-feudalism’.

In my view, the theory that rent has replaced profit in modern capitalism as exemplified by the American tech and AI giants (which it is argued get most of their gains from monopoly rent rather than profits from exploitation) is false. It misunderstands Marx’s theory of rent. Capitalists are continually searching for more profit. They invest in technologies and sectors that can deliver surplus profits ie above the average rate of profit. But if capital can move freely into sectors, then any profit rate differentials in sectors will tend to disappear. However, if it is possible to monopolise a part of constant capital (it could be property or land traditionally, or now intellectual property rights, IPR), then surplus profits can be ‘permanently ‘ siphoned off by the monopoly owner (landowner or patent holder).

But rent merely modifies the law of value and tendency to equalise profit rates. The capitalist mode of production has not been abolished. Yes, putting up barriers to access to new technologies or drugs enables the property owners of these ‘rights’ to take a share of the surplus value appropriated from productive labour. But is that permanent and how much is this ‘rent’ as a share of the total surplus value in an economy? Undoubtedly, much of the mega profits of the likes of Apple, Microsoft, Netflix, Amazon, Facebook are due to their control over patents, financial strength (cheap credit) and buying up of potential competitors. But the rent explanation goes too far. Technological superiority explains the success of these big companies, not just monopoly power.

Moreover, by its very nature, capitalism, based on ‘many capitals’ in competition, cannot tolerate any ‘eternal’ monopoly, namely a ‘permanent’ surplus profit deducted from the sum total of profits divided among the capitalist class as a whole. The battle among individual capitalists to increase profits and their share of the market means monopolies are continually under threat from new rivals, new technologies and international competitors. Take the constituents of the US S&P-500 index. The companies in the top 500 have not stayed the same. New industries and sectors emerge and previously dominant companies wither on the vine. The substitution of new products for old ones in the long run will reduce or eliminate monopoly advantage. The monopolistic world of GE and the motor manufacturers of the 1960s and 1990s did not last once new technology bred new sectors for capital accumulation.

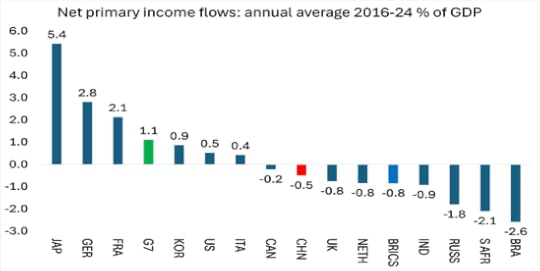

Indeed, rents from ‘permanent surplus profits’ are no more than 20% of value-added in any major economy; financial profits are even smaller a proportion. Richard Kozil-Wright at UNCTAD made an attempt to measure the size of rents as defined. He found that rents were about 20-25% of total operating profits. In another attempt, Mariana Mazzucato and colleagues used export revenues from IPR and found that these had risen sharply in the last 30 years. Cedric Durand and colleague made a similar calculation, showing that cross-border IPR receipts had reached $323bn in high-income economies in 2016. That sounds large, but IPR receipts are actually just a tiny proportion of US receipts of all profit repatriations, dividends and interest income from overseas. I did a quick update calculation from World Bank data and found that cross-border income from IPR is no more than 10% of all income received globally from trade and investment (profits, interest, dividends etc).

Source: World Bank

US corporate profits have been elevated since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. As of the last quarter of 2024, they were $4 trillion—2.3 percentage points higher as a fraction of national income than they were prior to the pandemic. The increase was entirely driven by traditional capitalist nonfinancial industries, particularly in retail and wholesale trade, construction, manufacturing and health care.

At HM, there was a session with presentations that rejected ‘rentier capitalism’ or ‘techno-feudalism’. US tech workers, AK Norris and Tavo Espinosa, argued that technology facilitates and makes possible a process of intensification of labour that generates surplus value as profits, similar to earlier forms of manufacturing. Stephen Maher and Scott Aquano of the Socialist Register showed that there was no evidence that the tendency toward the equalization of the profit rate has been suspended, or that ‘platform companies’ like Amazon consistently capture above-average profits. The income of these firms, therefore, cannot be categorized as “rent,” but rather just traditional industrial and commercial profit.

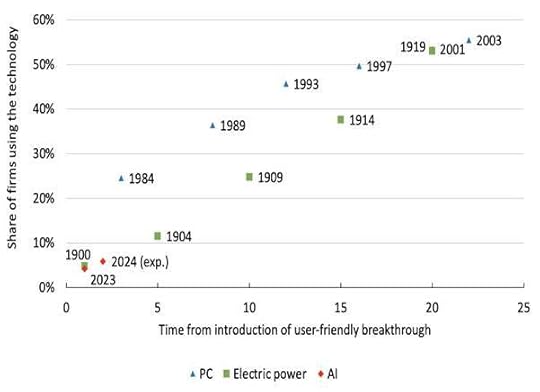

That brings me to the political economy of AI itself. Just how many jobs will be lost by the adoption of AI? And how quickly will it be adopted? Cristóbal Reyes Núñez disputed the techno optimist view that AI is coming fast and will step-change labour productivity. Based on information from the 2023 US National Business Survey of 300,000 US firms, Reyes found that the overall average adoption of AI so far was just 2.9% and even in the small number of mega firms at the top, it was still under 25%. This parallels the estimate by OECD economists of 5% adoption by firms, which at current rates of growth would mean it would take around 20 years before there was a critical mass infusion of the AI usage – assuming that AI actually works. And as Eleni Papagiannaki said in the same session, adoption does not just depend on whether AI actually works to boost productivity of labour, but on whether it becomes profitable.

Rate of adoption (% share of firms using technology)

Source: OECD

AI will only become infused across the capitalist economy if it can help the owners of the means of production to replace, or supervise and control human labour to increase profitability. Matteo Pasquinelli was the winner of last year’s Isaac Deutscher book prize with a book called In the eye of the master. He opened a plenary session at HM this year, where he argued that, whereas in the past labour was supervised and controlled by the masters (the owners and their agents, the managers), now supervision will be increasingly automated. So, instead of AI and automation being used collectively by us all, machines will rule our lives for the benefit of the master and profit.

But right now, AI is not profitable. ChatGPT may have over 400m users, but only 5% pay any regular subscription. And the huge increase in constant capital investment (data centers etc) is fast sucking up the existing profits of the Magnificent Seven tech giants.

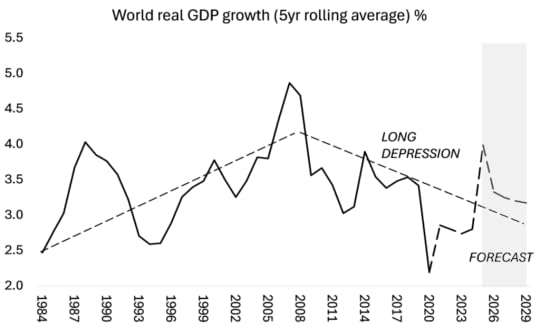

That brings me to the session in which I presented a paper on the current state of world economy and on whether AI will be the saviour of capitalism over the next decade or so. In my presentation, I argued that the major capitalist economies are stagnating: real GDP, investment and labour productivity growth have slowed significantly since the Great Recession of 2008-9; and again after the end of pandemic slump of 2020. In other words, the major economies are still in a Long Depression.

Source: IMF

This is intensifying what can be called a ‘polycrisis’ of rising poverty and inequality of wealth and incomes, both globally and within countries; an uncontrolled rise in global warming; and increased geopolitical conflict that threatens more wars.

But can AI deliver a new golden age for capitalism of high profitability and productivity? The classic Marxist answer is that capitalism can get a new lease of life only if there is ‘creative destruction’ of old capital and unprofitable firms. But governments are desperate to avoid such ‘shock therapy’ because of the political backlash that could follow. So the capitalist system is stagnating, and time is running out to fix things. In the session, Kim Moody of Labour Notes made an insightful critique of AI as a saviour of capitalism. There is no sign of any sharp rise in productivity and adoption rates are low. Moreover, AI is not a dependable new technology that can bring to an end the supply chain crisis that has developed since the end of the pandemic slump.

The only alternative to end the polycrisis is socialist one where, instead of investment being dependent on the profitability of private owners of the means of production, the means of production are commonly owned and investment is planned for social need. Right now, in the major economies, private investment that is dependent on profitability is five times larger (15% of GDP) than public investment (3%). Only when that ratio is reversed can we start to get economic growth aimed at social needs; deal with climate change and global warming; and reduce inequality, both within and between rich and poor countries.

Addendum: This year’s winner of the Isaac and Tamara Deutscher Prize was Bruno Leipold’s “Citizen Marx: Republicanism and the Formation of Karl Marx’s Social and Political Thought” https://press.princeton.edu/books/hardcover/9780691205236/citizen-marx?srsltid=AfmBOoq4CKmdNfg-FzHhetsU0XNYh7ErO69f0pX1qLNw67GNN74BnygO

“Leipold shows how Marx positioned his republican communism to displace both antipolitical socialism and anticommunist republicanism. One of Marx’s great contributions, Leipold suggests, was to place politics (and especially democratic politics) at the heart of socialism.”

It all comes down to political action in the end.

November 11, 2025

Historical Materialism 2025 part one: imperialism and war

Every year the Historical Materialism journal holds a conference in London. It is attended by (mostly) academics and students to discuss Marxist theory and critique capitalism.

This year the conference seemed very well attended and the best organised ever. There was a huge range of sessions and plenaries on economics, culture, technology, imperialism, war and gender issues. There were many ‘streams’ of presentations on fascism, technology (AI), imperialism, climate change and, of course, Marxist theory. I could not be in two places at once and review all the papers, so my coverage of the conference will be biased by my own preferences.

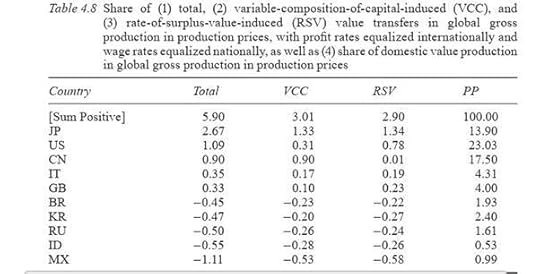

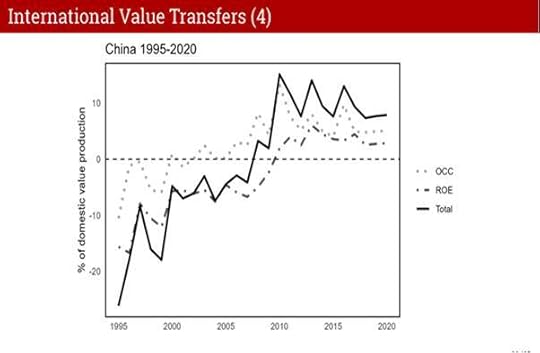

Let me start by recounting my own presentation in a session on imperialism. My paper was called Catching up or falling behind? In this, I considered whether the poorer countries of the so-called Global South were ‘catching up’ with the richer countries of the so-called Global North? The measurements of ‘catching up’ that I used were 1) per capita income levels; 2) labour productivity levels; and 3) the human development index compiled by the UN. I took the average annual growth trend for each of these measures for the G7 (or the so-called ‘high income’ economies) and compared that with those of the BRICS. I projected these trends forward to see if the gap between the rich Global North economies would eventually be closed by the Global South economies (BRICS). On all three measures, the Global South was not closing the gap and never would – with the possible exception of China.

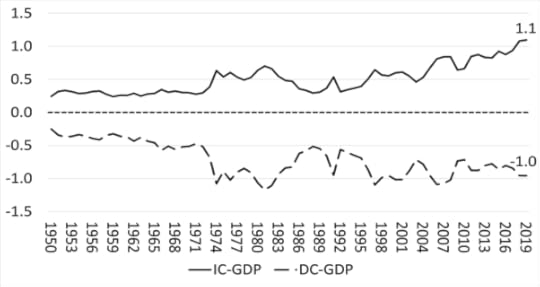

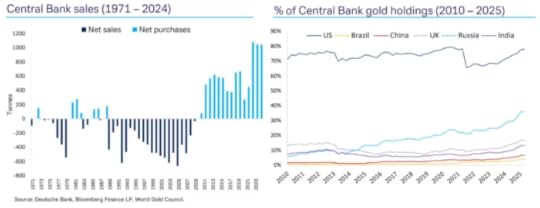

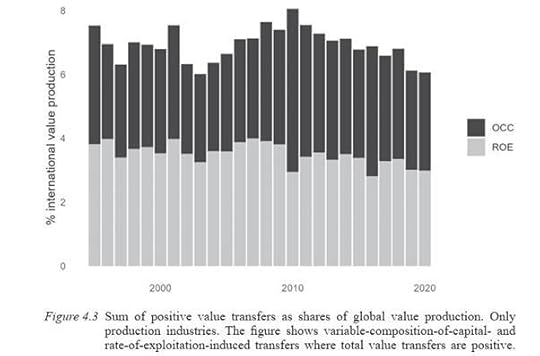

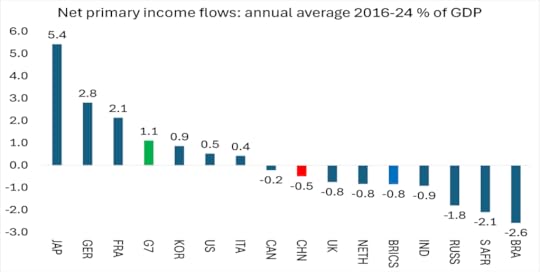

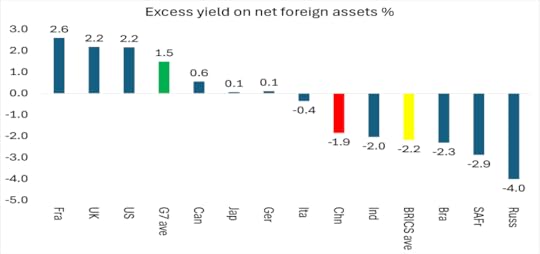

Why was the gap not being closed? The main reason was imperialism. Wealth (value) is being persistently transferred from the Global South to the Global North. Also, profitability of capital in the Global South was falling faster than labour productivity growth was rising, and this slowed down productive investment and economic growth in the Global South. China was the exception because its investment growth was less determined by the profitability of capital than in any other major Global South economy. I found that the annual gain in value to the imperialist economies of the Global North was about 2-3% of GDP each year, while the annual loss was similar for the much more populated economies of the Global South. In other words, if it were not for imperialist exploitation, the G7 economies (including the US) would not be growing at all, while the Global South economies would be growing much faster and starting to catch up.

Imperialist value transfers through trade (% of GDP)

Source: The Economics of modern imperialism, Historical Materialism journal, 4, 2021

Source: IMF

In the same session, Pedro Matto made a convincing critique of the concept of sub-imperialism. This concept argues that the Global North may gain transfers of value from Global South countries, but the larger capitalist economies of the South, like Brazil, Russia, South Africa, India or China also gain transfers of value from weaker peripheral economies in their regions. In that sense, these countries are sub-imperialists.

I have never been convinced of this concept for three reasons: first, it implies that every country is both ‘a bit imperialist’ and a ‘bit exploited’. This really weakens the concept of imperialism based on just a few mature, developed capitalist economies of the Global North, as Lenin first identified them, exploiting the rest of the world. Second, as Matto’s critique said, if every country is a bit imperialist, it weakens any direction for anti-imperialist struggle. Also, there is just no empirical evidence of major transfers of value from the likes of Zambia to South Africa; or from Paraguay to Brazil; or from poorer Asia countries to China that in any way matches the size of transfers of value through trade and financial flows from the BRICS to the G7+ economies.

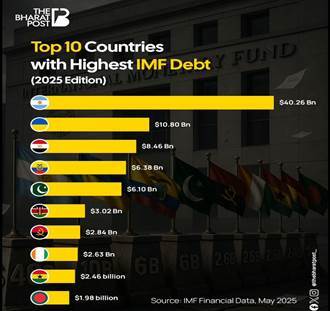

Also in this session Cristina Re and Gianmaria Brunazzi presented an intriguing theory of what they called ‘debt-driven imperialism’. The US used to be a creditor in the world economy, running trade surpluses, while lending and investing abroad. But since the 1970s, it increasingly ran trade deficits and so built up huge debts with the rest of the world, particularly with Europe, Japan and China. But because the dollar was the world’s trading and reserve currency, this debt was not a disadvantage, but instead a new economic weapon for US imperialism to dominate other countries.

I have to say that I did not find this theory convincing. For me, debt imperialism is where poor countries run up huge debts (loans) from imperialist institutions in order to grow, but then in economic crises are forced to default, devalue their currencies and impose severe austerity measures to meet their obligations with Global North banks and the IMF etc. The US is an exception as a debtor because of the ‘extraordinary privilege’ of the dollar and because it can easily finance its trade deficits through investment from abroad into US companies and financial assets. But I do not see how it follows from this that US debt is a new avenue of domination for US imperialism.

Let me also report on a massively attended ‘flagship’ session on Rethinking Imperialism and War. Michael Hardt argued that imperialism (presumably both the US and Europe) was morphing into ‘global war regimes’ as militarism takes over from economic domination. Another speaker Morteza Samanpour argued the following (taken from his abstract): “capitalist globalization does not homogenize time but intensifies its differentiation. Through logistical, financial, and extractive operations, capital simultaneously unifies and fragments spatio-temporalities, producing active disjunctures that serve its global reproduction.” And “an internationalist, anti-imperialist political strategy must attune itself to the fractured, uneven temporalities of the present—particularly with regard to the contemporary war conjuncture and the proliferation of imperial formations beyond the historical West. It calls for a renewed strategic rationality capable of productively engaging the disjunctive social times of capital in the service of a genuinely emancipatory internationalism.”

I must say I struggled to understand what all this meant – I’m very much a simpleton who needs simple language. Anyway, I think the gist of it was an attack on what is apparently called ‘campism’, namely that just because there are powers globally resisting the policies of US imperialism, that does not mean that Marxists “should endorse authoritarian states like Iran, or Russia or China simply because they oppose the U.S. and Israel.” I have sympathy with that view, although the political economist in me objects to what Samanpour called the “proliferation of imperial formations beyond the historical West”, by which does he mean that China or Russia are imperialist or even Iran or Saudi Arabia?

The other speakers is this mega session concentrated on how to fight imperialism and war. Eleonora Cappuccilli and Michele Basso looked to international class-based organisations that they are trying to build and not to ‘resistant’ states as the way to defeat imperialism and stop war, although they talked of a ‘living labour’ movement (I thought a simpler term might be a ‘workers’ movement) and seemed to argue that migrant and ‘precarious labour’ would be the spearhead in fighting imperialism, which seemed unlikely to me.

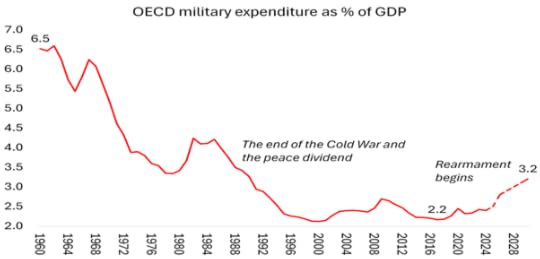

Feyzi Ismail argued that investment in and the maintenance of military infrastructure are big drivers of global carbon emissions and environmental destruction. Global military activities – excluding active warfare – already account for approximately 6% of total global emissions, Stopping the cycle of prioritising military responses to security, access to national resources, climate-induced migration or natural disasters, means mobilising mass movements – not only the climate movement, but movements against war and austerity through trade unions and workers.

Source: OECD

Overall, I found this session confusing, but maybe I am getting old. The claim is that imperialism is not confined to the ‘usual suspects’ of the Global North, but now, the world order is multi-polar with the main battle between two big imperialist powers, one declining one, the US; and one rising one, China. My view is different. I do not see the US and China as equally antagonistic and aggressive imperialisms. Those who regularly read this blog and my papers on China’s economic development know that I do not view China as imperialist in the economic sense i.e. gaining huge transfers of value through trade and financial flows from poor countries. Also, I do not consider China as capitalist in the sense that the law of value and production and investment for profit rule. Instead, China has an economy where state investment and planning dominate over the capitalist sector. That does not mean, however, that the Chinese government is a bastion of revolutionary international struggle against imperialism, as the ‘campists’ claim. Indeed, China’s ‘Communist’ leaders are outright nationalists in orientation.

In Part two of my review of this year’s HM, I shall look at the sessions on the climate crisis and ecology; and on technology, particularly artificial intelligence; and also I shall sum up the session of my second presentation that discussed key trends in the world economy.

November 1, 2025

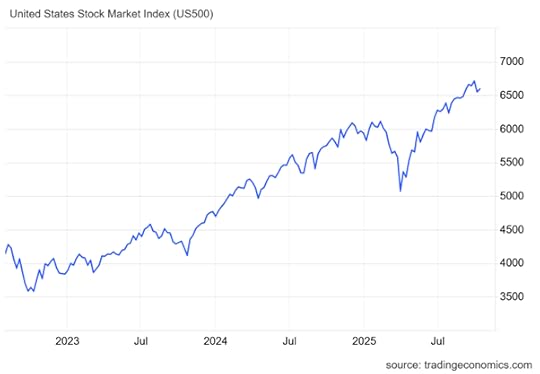

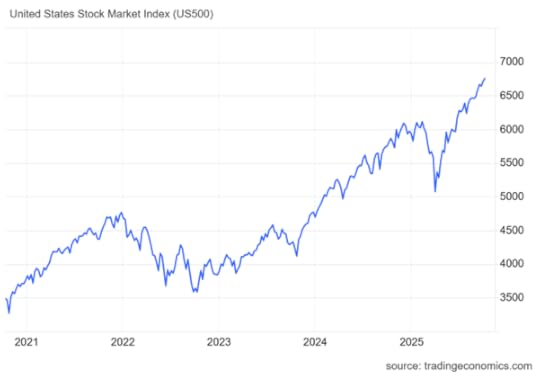

Debt and the cockroaches

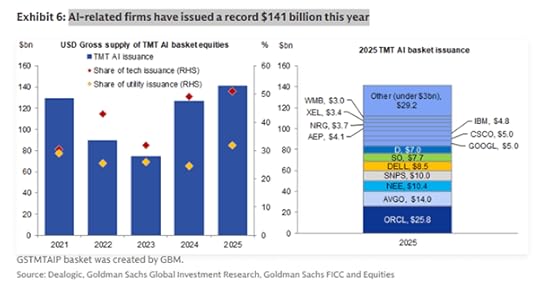

Let the Financial Times sum it up: “US stocks ride AI hype and trade truce to 6-month winning streak S&P 500 and Nasdaq post longest runs of monthly gains in years.” The FT points out that US stocks have hit their longest monthly winning streak in four years as AI hype, declining interest rates and Donald Trump’s move to dial back his trade war led the way. The S&P 500 rose in October for a sixth consecutive month of gains, and reached its 36th all-time high this year last Tuesday. It is the best run for the index since August 2021.

Any concerns about an AI bubble in the making, and signs of weakness in the US labour market have been eclipsed by a torrent of bullish spending announcements and strong earnings from Silicon Valley tech groups. And then the one-year deal between China and the US to postpone export controls on rare earths and chips added more to bullish sentiment. The Federal Reserve also delivered its second rate cut of the year on Wednesday. The Fed rate cut followed an explosion of mergers and acquisitions across corporate America, with more than $80bn worth of deals struck on last Monday.

The tech giants delivered their quarterly earnings results. Amazon shares rose 12 per cent on Friday, adding almost $300bn to its market value after the company’s cloud business reported its strongest quarterly growth in nearly three years. Meta sold $30bn of bonds to finance AI projects and the bond sale drew about $125bn of orders — the grade corporate bond. largest-ever demand in dollar terms for a US investment. Nvidia became the first company to reach a capitalisation of $5tn and Apple topped $4tn for the first time. “Yes, this is a bull market that’s run a long way . . . but at the moment the tech firms just keep on delivering,” said John Bilton, head of global multi asset strategy at JPMorgan Asset Management. “The fact everyone is telling me [tech] is a bubble makes me think it’s got further to go.”

Investment advisors were ecstatic: “There’s a greater consensus that the impact of AI is going to be real and transformational, earnings season is turning out well, we are at the beginning of a Fed rate cutting cycle, and there’s optimism that there could be a reasonable [US trade] deal with China,” said Venu Krishna, head of US equities strategy at Barclays. All the doom mongers have egg on their faces. The US economy is not in a slump, inflation is not out of control and Trump has made a trade truce with China. So everything is hunky dory in the best of all possible worlds.

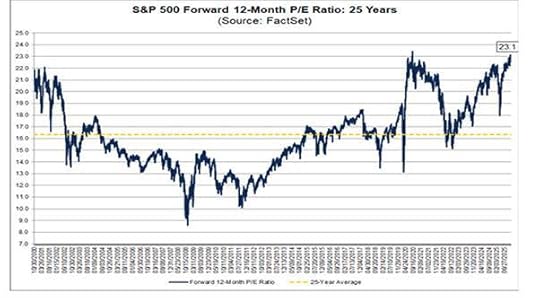

But is all really so well? The stock market boom has taken the ratio of stock market prices to corporate earnings to new highs. The P/E ratio, as it is called, is now some 40% above its historic average and surpassing the ratio reached during the so-called ‘dot.com bubble of 2000. That bubble burst with a fall of 40% in the P/E ratio.

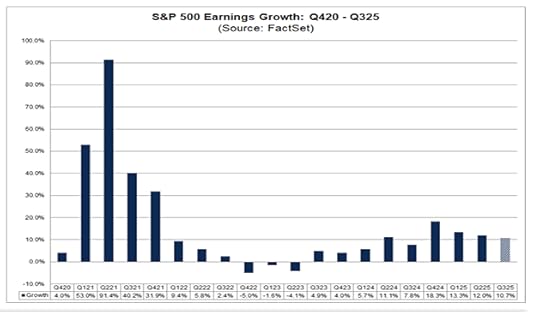

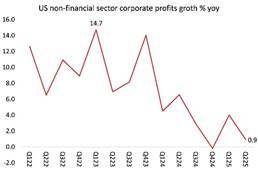

In previous posts, I have pointed out that the US success story is almost totally due to the expansion of AI investment by the tech giants, which continue to rack up big profits. But the rest of the US corporate economy is in the doldrums. In the corporate sector, earnings are still rising, but at a slower pace, up over 18% yoy at the end of 2024, but in in Q3 2025, rising at 10.7% – still good but on a downward trend.

Source: FactSet

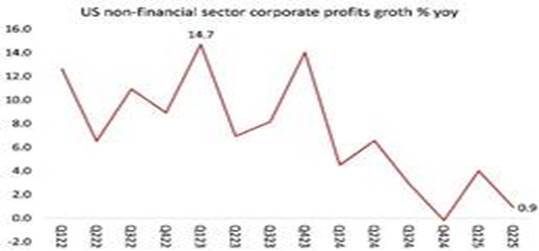

The rate of profit, although up from the depths of the pandemic slump, is still low historically, while profit growth is slowing in the non-financial sector.

Source: BEA

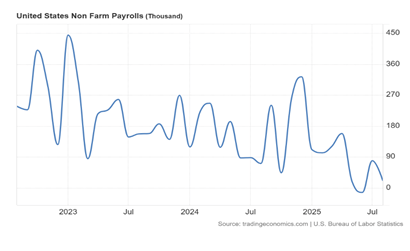

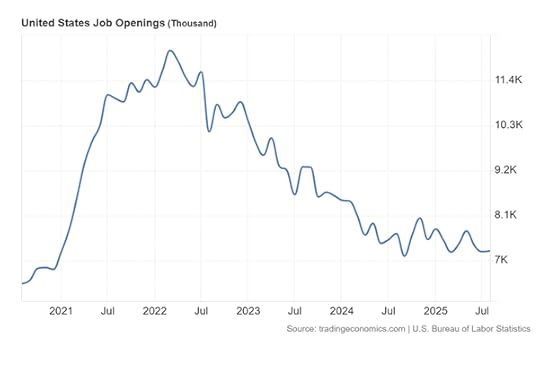

Even the Magnificent Seven are forecasting a fall in earnings growth, mainly because of heavy AI spending. At Meta and Amazon, profits are supposed to grind down to nearly nothing. As for working people, the market for labour has been weakening. Net new jobs are disappearing.

And once people lose their jobs, it is increasingly difficult to get another.

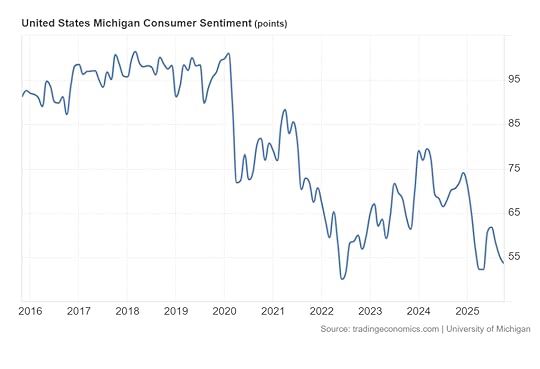

No wonder the euphoria in the stock markets is not mirrored in the labour market. American consumers have never been so depressed by their situation.

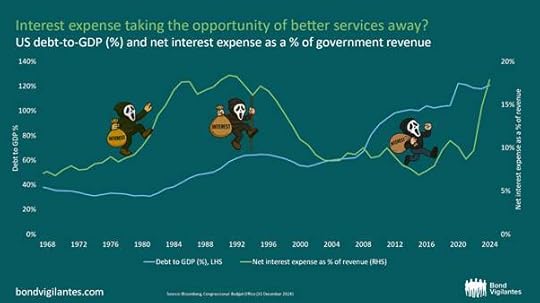

But the only joker in the economic pack of cards, according to investors and corporate strategists, is the public sector. The US government is still running huge annual budget deficits and thus driving up the level of government debt, and so increasing the cost of servicing that debt.

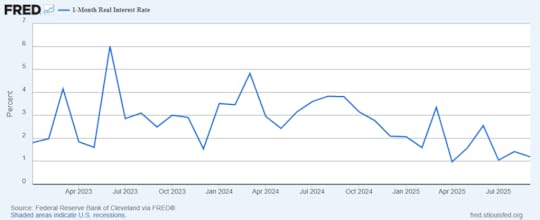

Apparently, this is the reason for low investment in productive assets: government bond issuance is rising so fast that it is ‘crowding out’ credit for the private sector to invest in productive assets. This is nonsense. There are now many studies that show that interest costs are not the first worry for companies. The main question for firms is: what return in profits will there be from new investments?

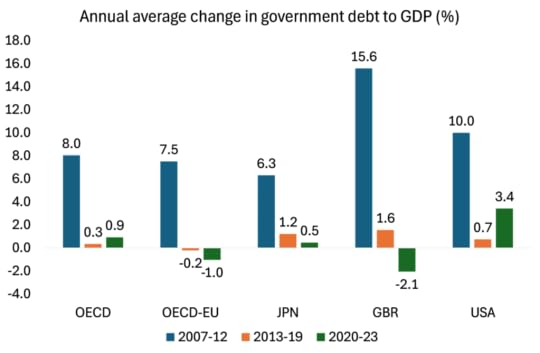

The reason that public sector debt has risen so much in the 21st century was the bailing out of the finance and private sector during the global financial crash of 2008-9, the euro debt crisis through to 2012, and the fiscal support necessary for people to get through the pandemic slump of 2020. Those were the periods when government debt ratios rocketed. In the periods in between, policies of austerity (particularly in cutting welfare benefits and investment in infrastructure), along with a some recovery in growth, kept debt ratios more or less stable. Meanwhile, cuts in personal income taxes (particularly for higher income groups) and corporate profits taxes meant that government tax revenues as a share of GDP remained flat at around 35% of GDP, while government spending to GDP rose (IMF).

Source: OECD

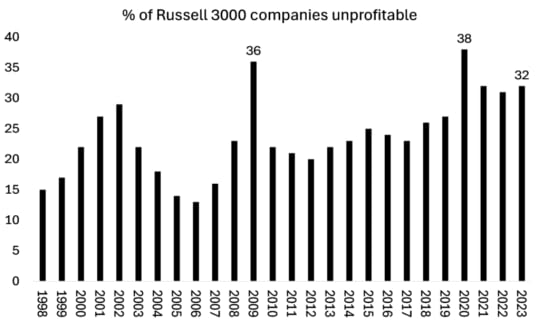

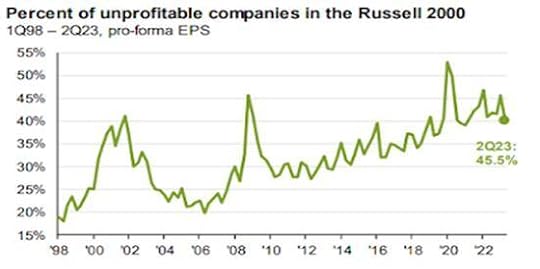

Debt does matter, but the debt that matters in a capitalist economy is not so much public debt, but corporate debt. The latest estimates are that in the major economies, some 30%-plus of companies have so much debt that they do not earn enough profits to service that debt.

Source: Bloomberg

Despite most central banks cutting short-term interest rates, borrowing rates for corporations have not fallen so much. The big cash-rich companies do not need to borrow and if they do, they can get the best rates. The AI companies are still able to fund their huge capital investments from existing cash reserves and earnings from successful core businesses, although that cash is being drained fast. But other companies are dependent on the banking sector to keep bailing them out.

And here is the risk. In the US, smaller regional banks got into deep trouble in March 2023, when start-up tech companies started to take out their deposits to keep going and the banks could not meet their obligations. And last month, JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon delivered a cryptic warning to the financial system. Referring to the bankruptcies of auto parts supplier First Brands and subprime auto lender Tricolor Holdings, Dimon said: “When you see one cockroach, there’s probably more. Everyone should be forewarned on this one.” JPMorgan lost $170 million on Tricolor. Fifth Third Bancorp and Barclays also lost $178 million and $147 million. Some US regional banks were also back in the wars. First Citizens Bancshares and South State lost $82 million and $32 million, respectively.

And just as in March 2023, European banks are in the mix. Back then, it was the mighty Swiss bank Credit Suisse that went under. This time, European banks BNP Paribas and HSBC each called out specific write-downs of $100 million or more in loan exposure. And just as in March 2023, it appears that fraud is involved. Apparently, $2.3 billion in so-called ‘factoring deals’ have “simply vanished” from First Brands accounts.

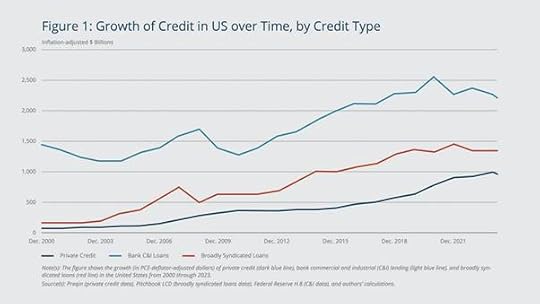

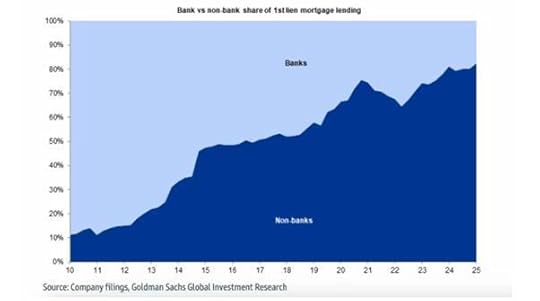

That’s the risk to the commercial banks. But increasingly, the big banks are not lending directly to companies, particularly smaller ones, but instead providing ‘liquidity’ to non-bank lenders, so-called ‘private credit’ companies. Non-bank financial institutions now account for over 10 per cent of all US bank loans. While direct on-balance-sheet funding by banks has declined sharply since 2012, the use of credit lines to non-banks has expanded significantly, now representing approximately 3% of GDP. Having grown from $500 billion in 2020 to almost $1.3 trillion today, private credit is an increasingly important source of financing for companies.

Much of this private credit lending is now used for household mortgages – shades of 2007.

As this private credit is not on bank balance sheets, it is not regulated. That could mean that there may not be enough capital in the credit companies to meet any losses if the companies they lend to go bust. Then the private credit companies could also go bust or need a big bailout by the commercial banks – a classic ricochet through the financial system – and perhaps onto the ‘real economy’.

Such ‘systemic risk’, as it is called, is dismissed by most financial strategists. Goldman Sachs recently went out of its way to argue that there was no risk from non-bank private credit companies going belly up. On the other hand, Bank of England governor Andrew Bailey raised “alarm bells” over risky lending in the private credit markets following the collapse of First Brands and Tricolor. And he drew a direct parallel with practices before the 2008 financial crisis.

Referring to how ‘repackaged’ financial products have in the past obscured the risk of the underlying assets, Bailey said: “We certainly are beginning to see, for instance, what used to be called slicing and dicing and tranching of loan structures going on, and if you were involved before the financial crisis then alarm bells start going off at that point. Tricolor and First Brands both made use of asset-backed debt, with the subprime lender bundling up car loans into bonds and the car parts manufacturer tapping specialist funds to provide credit against its invoices.” Bailey’s comments follow a warning last month from the IMF that US and European banks’ $4.5tn exposure to hedge funds, private credit groups and other non-bank financial institutions could “amplify any downturn and transmit stress to the wider financial system”.

So the stock market may be booming and the AI hype is still exploding, but the rest of the economy is not so buoyant; and there appear to be cockroaches eating into the clean running of the world of debt. Watch that space.

October 24, 2025

Depression and creative destruction

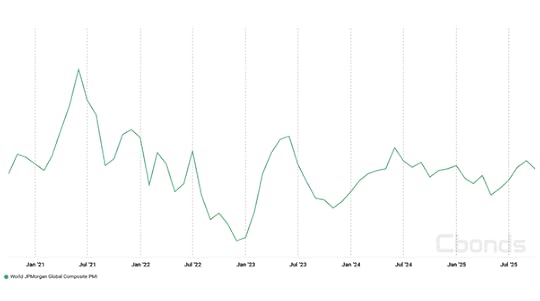

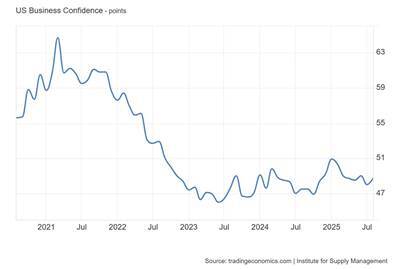

The latest economic activity indicators called purchasing managers indexes (PMIs) confirm that the major economies are still crawling along – neither slipping into slump nor picking up pace. The global PMI stands at 52.4 in September (any score above 50.0 means expansion, any score below means contraction).

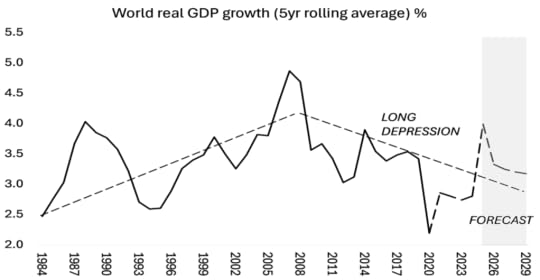

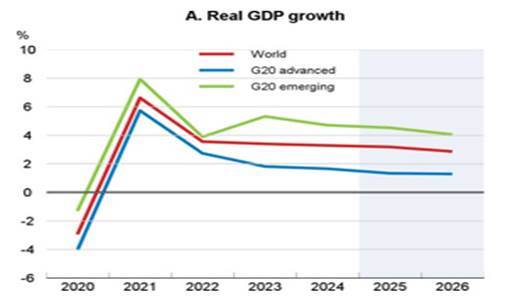

Source: JPM

In effect, the major economies remain in what I call a Long Depression that started after the Great Recession of 2008-9. In the last 17 years, economic expansion (as measured by real GDP, investment and productivity growth) has been well below the pre-2008 rate, with no sign of any step change. Indeed, after the pandemic slump of 2020, the rate of growth in all these indicators has slowed further. Whereas world real GDP growth averaged an annual 4.4% before the Great Recession of 2008-9, in the 2010s, it managed only 3% and since the 2020 pandemic slump, annual average growth has slowed to 2.7% a year. And remember, this rate includes the fast-growing economies of China and India. And also, in some key countries (the US, Canada, the UK) it has (until recently) been net immigration boosting the labour force that supported real GDP growth; per capita GDP growth has been much lower.

Source: IMF, World Bank

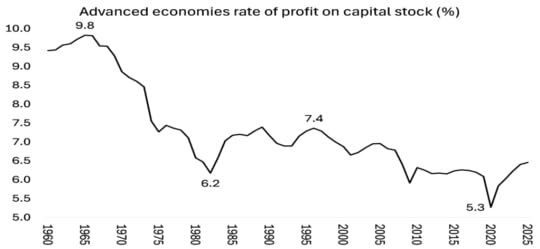

Above all, the profitability of capital in the major economies remains near a historic low and well below the level before the Great Recession.

Source: EWPT 7.0 series, AMECO, author’s calculation

In its latest economic forecast released last week, the IMF improved its forecast for global growth slightly, but still predicted a slowdown. “We now project global growth at 3.2 percent this year and 3.1 percent next year, a cumulative downgrade of 0.2 percentage point since our forecast a year earlier.” The IMF economists reckon US real GDP will rise just 2.0% this year, down from 2.8% in 2024, and then increase by just 2.1% next year. And that’s the best performance expected in the top G7 capitalist economies, with Germany, France, Italy and Japan likely to record less than a 1% increase this year and next. Canada will also slow to well under 2% – only the UK will improve (to a very modest 1.3% this year and next). But even these forecasts are in doubt as the outlook “remains fragile, and risks remain tilted to the downside”. The IMF is worried about: 1) a burst in the AI bubble; 2) a productivity slowdown in China; and 3) rising government debt and servicing.

The OECD economists are just as pessimistic. In its September Interim report on the world economy, the OECD expects global economic growth to slow to 3.2% in 2025 and 2.9% in 2026, down from 3.3% in 2024. Indeed, the OECD economists reckon that US real GDP growth will be at its slowest since the pandemic and so will China’s. And the euro area, Japan and the UK will grow just 1% or less. Growth in the US is expected at 1.8% in 2025 and 1.5% in 2026. China’s growth is seen easing to 4.9% in 2025 and 4.4% in 2026 – although that rate is still nearly three times as fast as the US and four times as fast as the euro area, which is projected to expand 1.2% in 2025 and 1.1% in 2026. Unlike the IMF, the OECD expects the UK to slow to just 1% a year in 2026, while Japan is forecast at 1.1% and 0.5% over the same period.

The UN’s trade and development agency (UNCTAD) has also released an advanced preview of its Trade and Development Report 2025. It makes for sober reading on the prospects for global growth and trade. UNCTAD economists see “faltering global growth which shows no signs of picking up in the near term. Global output growth continues to lag behind pre-pandemic trends. Momentum remains fragile and clouded by uncertainty. Investor anxiety has boosted financial markets, but not productive investment.”

Nevertheless, the major economies have not slipped into a new slump as experienced in 2008-9 and in the 2020 pandemic slump. Instead, the crawl has resumed. But neither does capitalism show any signs of leaping forward: the major economies are increasingly stuck in a period of ‘stagflation’ ie stagnating growth alongside rising inflation.

Why is this? In the Marxist theory of crises, a long boom would only be possible if there was a significant destruction of capital values, either physically or through price devaluation, or both. Joseph Schumpeter, the Austrian economist of the 1920s, taking Marx’s cue, called this ‘creative destruction’. By cleansing the accumulation process of obsolete technology and failing and unprofitable capital, new innovatory firms would prosper, boosting the productivity of labour and delivering more value. Schumpeter saw this process as breaking up stagnating monopolies and replacing them with smaller innovating firms. In contrast, Marx saw creative destruction as raising the rate of profitability as the small and weak were eaten up by the large and strong.

For Marx, there were two parts to ‘creative destruction’. There was the destruction of real capital “in so far as the process of reproduction is arrested, the labour process is limited or even entirely arrested and real capital is destroyed” because the “existing conditions of production …are not put into action”, ie firms close down plant and equipment, lay off workers and/or go bust. The value of capital is ‘written off’ because labour and equipment etc are no longer used.

In the second case, it is the value of capital that is destroyed. In this case “no use value is destroyed.” … instead, “a great part of the nominal capital of society ie of exchange value of the existing capital, is completely destroyed.” And there is a fall in the value of state bonds and other forms of ‘fictitious capital’. The latter leads to a “simple transfer of wealth from one hand to another” (those who gain from falling bond and stock prices from those who lose).

Marx argued that there is no permanent slump in capitalism that cannot be overcome by capital itself. Capitalism has an economic way out if the mass of working people do not gain political power to replace the system. Eventually, through a series of slumps, the profitability of capital could be restored sufficiently to start to make use of any new technical advances and innovation. That happened after the end of WW2, when the profitability of capital was very high and companies could thus confidently invest in the new technologies developed during the depression of the 1930s and the war. If profitability could be raised sharply now in 2025, then the diffusion of new technologies like AI that are already ‘clustering’ in the current depression could possibly take off and create a step change in the productivity of labour in the major economies.

This theory of creative destruction has been taken up by mainstream economists. Recent Nobel (Riksbank) prize winners for economics, Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt noted that the speed of the rise of new firms with new technology and the fall of old firms with old technology is positively correlated with labour productivity growth.“This could reflect the direct contribution of creative destruction and possibly also an indirect effect of creative destruction on incumbent efforts to improve their own products.” But there is no role for profitability in this mainstream theory of creative destruction. Aghion and Howett stick closely to the Schumpeter view of innovation by small firms. However, Aghion and Howett do note that firm exit and entry rates into sectors have both fallen in the US in recent decades. The employment share of new entrants (firms less than five years old) fell from 24% to 15%. In other words, the main form of reviving capitalist investment and production has dissipated. As ‘creative destruction’ is an essential contributor to growth, “this declining ‘business dynamism’ has contributed to the slow and disappointing US productivity growth”.

AI and other new technologies, even if they are effective (and that is in doubt), will not deliver sustained and higher growth because there has been no ‘creative destruction’ since 2008. Instead, there has been an unprecedented expansion of cheap credit money to support businesses, large and small, in an attempt to avoid slumps. There has been no collapse in stock and bond prices or massive corporate bankruptcies – on the contrary, new record highs in financial and property assets are continually reached. Instead of liquidation, there have been a growing number of corporate ‘living dead’ or zombie capitals, which do not make enough profit to service their debts and so just borrow more. There is also a sizeable layer of ‘fallen angels’, ie corporations with mounting debts that could soon make them zombies too.

Back at the start of the Great Depression of the 1930s, there was a division of opinion among the strategists of capital on what to do. The then Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon told the then President Hoover to ‘Liquidate labor, liquidate stocks, liquidate the farmers, liquidate real estate.’ He said: ‘It will purge the rottenness out of the system. High costs of living and high living will come down. People will work harder, live a more moral life. Values will be adjusted, and enterprising people will pick up the wrecks from less competent people.’ But just as now, the liquidation policy was rejected by the rest of administration, not because it was wrong economically, but for fear of the political repercussions. Hoover was nevertheless opposed to planning or government spending to mitigate the slump. “I refused national plans to put the government into business in competition with its citizens. That was born of Karl Marx. I vetoed the idea of recovery through stupendous spending to prime the pump. That was born of a British professor. I threw out attempts to centralize relief in Washington for politics and social experimentation.”

Perhaps the only recent policy example of ‘liquidation’ is the attempt of President Milei in Argentina. But his drastic cuts in the public sector, while sustaining high interest rates and restricting the money supply, have not produced any ‘creative’ outcome. Instead, his attempt to ‘cleanse’ the system of Argentina’s ‘unnecessary’ spending, unproductive workers and weak firms, to make the economy ‘leaner and fitter’, has pushed the Argentine peso currency to the edge of collapse, as foreign exchange reserves run out and facing huge FX debts soon needing to be paid back. So Trump and his Treasury Secretary Bessent have come to Milei’s aid with a bailout, just as the US banks got in 2008. Again, fear of the fall of Milei has led to the opposite of liquidation.

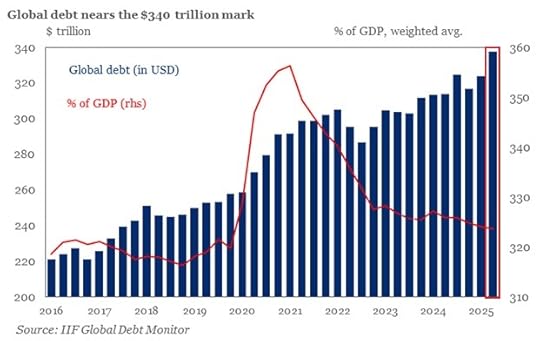

And the result is more debt. In trying to avoid slumps, governments and central banks have pumped in money and allowed companies and governments to build up debt. Global debt has reached nearly $340trn, up a massive $21 trillion so far this year, as much as the rise during the pandemic. Emerging markets accounted for $3.4 trillion of the increase in Q2, pushing their total debt to $109 trillion, an all-time high. The total debt-to-GDP ratio now stands at 324%, down from the peak in the pandemic slump, but still above pre-pandemic levels.

To solve the growth and debt problem, the IMF calls for cuts in public spending (“governments must not delay further. Improving the efficiency of public spending is an important way to encourage private investment.”) ie destruction; while pushing for increased support to the capitalist sector (“Governments should empower private entrepreneurs to innovate and thrive.”) ie creation. The destruction here is only in public services and welfare, while the private sector can expect more of the same: low interest rates, tax cuts and subsidies to ‘empower private entrepreneurs’.

October 14, 2025

The AI bubble and the US economy

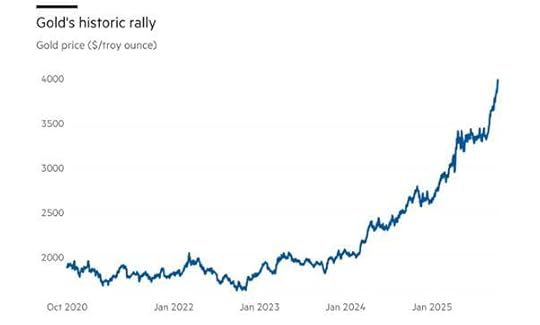

The US stock market continues to hit new record highs; the bitcoin price is also close to highs and the gold price has rocketed to all-time highs.

Investors in financial assets (banks, insurance companies, pension funds, hedge funds etc) are wildly optimistic and confident about financial markets. As the chair of Rockefeller International, Ruchir Sharma put it: “Despite mounting threats to the US economy — from high tariffs to collapsing immigration, eroding institutions, rising debt and sticky inflation — large companies and investors seem unfazed. They are increasingly confident that artificial intelligence is such a big force, it can counter all the challenges.” AI companies have accounted for 80 per cent of the gains in US stocks so far in 2025. That is helping to fund and drive US growth, as the AI-driven stock market draws in money from all over the world. Foreigners poured a record $290bn into US stocks in the second quarter of 2025 and now own about 30% of the market — the highest share in post-second world war history. As Sharma comments, the US has become “one big bet on AI”.

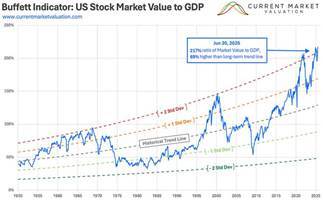

The AI investment ‘bubble’ (as measured as the stock price relative to the ‘book value’ of a company) is 17 times the size of the dot-com frenzy of 2000 — and four times the subprime mortgage bubble of 2007. The ratio of the US stock market’s value to GDP (aka the “Buffett Indicator”) has moved up to a new record high at 217%, more than 2 standard deviations above the long-term trendline.

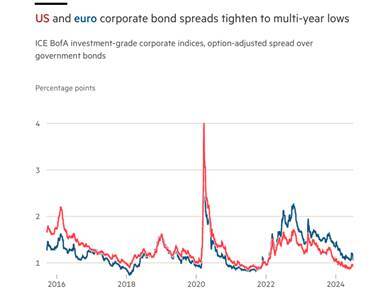

And it is not just corporate shares that are booming. There is a huge demand to hold the debt of US corporations, particularly the large tech and AI companies as per the so-called Magnificent Seven. The ‘spread’ of interest paid on corporate bonds compared to ‘safe’ government bonds has fallen to under 1% pt.

These bets on the future success of AI cover all bases, or another way to put it: all the eggs are in one basket: AI. Investors are betting that AI will eventually deliver huge returns on their stock and debt purchases, when the productivity of labour rises dramatically and with it, the profitability of AI companies. Matt Eagan, portfolio manager at Loomis Sayles, said that sky-high asset prices suggested investors were banking on “productivity gains of the kind we have never seen before” from AI. “It is the number one thing that could go wrong”.

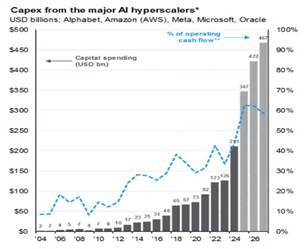

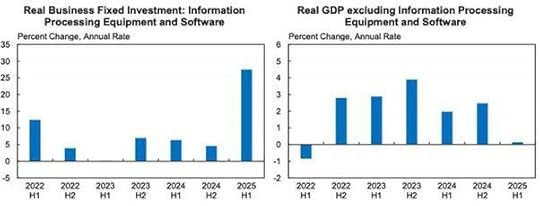

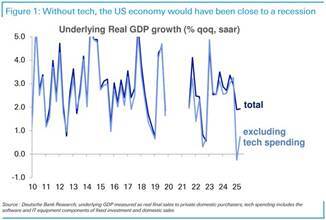

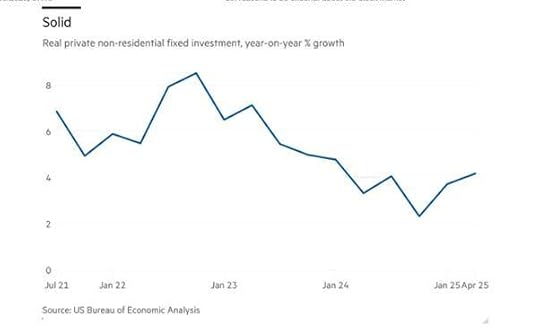

Up to now, there is little sign that AI investment is delivering faster productivity. But ironically, the huge investment in AI data centers and infrastructure is holding up the US economy in the meantime. Almost 40% of the US real GDP growth last quarter was driven by tech capex and the bulk of that capex was in AI-related investments.

AI infrastructure has risen by $400 billion since 2022. A notable chunk of this spending has been focused on information processing equipment, which spiked at a 39% annualized rate in the first half of 2025. Harvard economist Jason Furman commented that investment in information processing equipment & software is equivalent to only 4% of US GDP, but was responsible for 92% of GDP growth in the first half of 2025. If you exclude these categories, the US economy grew at only a 0.1% annual rate in the first half.

So without tech spending, the US would have been close to, or in, a recession this year.

What that shows is the other side of the story: namely the stagnation of the rest of the US economy. US manufacturing has been in recession for over two years (ie any score in graph below that is lower than 50).

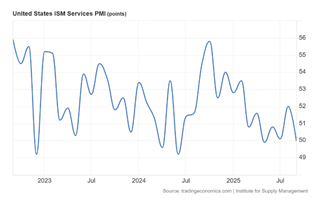

and now there are signs that the larger services sector is also in trouble. The ISM Services PMI (an economic survey indicator) fell to 50 in September 2025 from 52 in August and well below forecasts of 51.7, signalling the services sector has stalled.

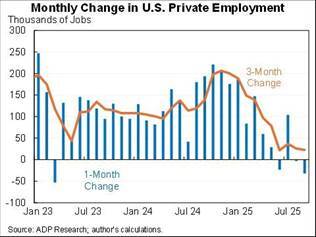

The US labour market is also looking weak. Employment grew at an annualised rate of just 0.5% in the three months to July, according to official data. That is well below the rates seen in 2024. “You’re in a low-hire, low-fire economy,” said Federal Reserve chair Jay Powell last month.

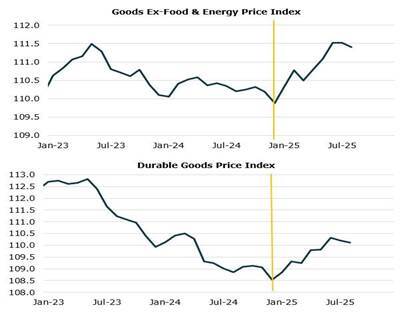

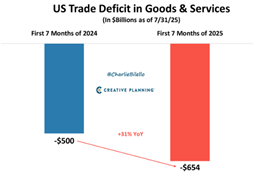

Young workers in the US are being disproportionately affected by the current economic downturn. US youth unemployment has risen from 6.6% to 10.5% since April 2023. Wage growth for young workers has declined sharply. Job vacancies for career starters have fallen by more than 30%. Early-career workers in AI-exposed occupations have experienced a 13% relative decline in employment. [image error]