Anne Renwick's Blog

November 20, 2025

Anne Renwick’s 10 Things You Must Do When Visiting London: A Guide for Fans of The Elemental Web

When I write my stories, I’m always consulting maps. Many of the places in my books are real—though some no longer exist. London is full of history and secrets hidden where you’d least expect them… and a few of those inspired scenes in my book.

When I write my stories, I’m always consulting maps. Many of the places in my books are real—though some no longer exist. London is full of history and secrets hidden where you’d least expect them… and a few of those inspired scenes in my book.

The Golden Spider

1) Crossness Pumping Station

The Golden Spider

1) Crossness Pumping Station

While the South London Waterworks that inspired Airship Sails in The Golden Spider no longer exists, you can experience the same Victorian industrial grandeur at Crossness Pumping Station. This magnificent sewage pumping station, built between 1859 and 1865 as part of Sir Joseph Bazalgette‘s revolutionary sewerage system, this magnificent station earned the nickname “Cathedral of Sewage” for a good reason.

The Station opens its doors on special event days where you can explore the ornate ironwork and machinery of the Victorian era. On Steam Days, you can see the Prince Consort engine in operation, its enormous flywheel turning, hear the hiss of steam, feel the vibration of steam power beneath your feet.

2) The Effra RiverThe Effra is one of London’s lost rivers—once wide enough for boats, now buried beneath the city and reduced to a storm drain. In Victorian times, a coffin was said to have floated down it from West Norwood Cemetery to the Thames, the grave above collapsing into the hidden stream below.

To glimpse what remains, head to the south side of Vauxhall Bridge. At low tide, you can spot the original outfall between the bridge and Vauxhall Cross. The larger outlet by the MI6 building marks the later storm relief channel, now viewable from the new Isle of Effra riverside platform opened in 2025.

Venomous Secrets

3) Burlington Arcade

Venomous Secrets

3) Burlington Arcade

Opened in 1819, Burlington Arcade is one of Britain’s earliest covered shopping arcades, stretching 196 yards between Piccadilly and Old Burlington Street in the heart of Mayfair. Built by Lord George Cavendish for “the sale of jewellery and fancy articles of fashionable demand,” it originally housed seventy-two small shops selling everything from hats and gloves to walking sticks and cigars.

What makes Burlington Arcade truly unique is its private police force—the Burlington Beadles, recruited from Lord Cavendish’s own regiment, the Royal Hussars. You’ll spot them easily in their Victorian frock coats, gold buttons, and gold-braided top hats, patrolling the arcade and enforcing a strict Regency-era code of conduct. This is the location of an early scene in Venomous Secrets.

4) The AlbanyJust east of Burlington Arcade lies one of London’s most prestigious addresses—a place so discreet you could walk past it a hundred times and never notice. The Albany is an enclave of bachelor apartments. Prospective residents are vetted by a daunting residents’ committee, and the interiors remain largely unchanged—poky, dark, arranged in ways that resist modernization, but utterly private and quiet. It’s featured in Venomous Secrets as our hero’s residence and is exactly the sort of address where you can hide secrets. While you can’t tour the interior, standing at its entrance gives you a sense of the hidden London that exists in plain sight.

5) The Lamb and FlagTucked away on Rose Street in Covent Garden, this historic pub served as inspiration for The Hissing Cockatrice in Venomous Secrets. Built in 1623 with much of its original timber frame still intact, the pub earned the nickname “Bucket of Blood” for its links to prize fighting. In 1679, the poet John Dryden was attacked in the narrow alley beside it. Inside are timber beams, dim passages, centuries of stories. The alleyway to Lazenby Court remains, still shadowed enough for Victorian intrigue.

6) Kensington Gardens & The Italian GardensWalk through Kensington Gardens, adjacent to Hyde Park, where the Serpentine winds. Make your way to the Italian Gardens on the north side near Lancaster Gate—an ornamental water garden created in the 1860s as a gift from Prince Albert to Queen Victoria. The elaborate design features four main basins with central rosettes carved in Carrara marble, and the striking Portland stone and white marble Tazza Fountain at its heart.

The Pump House overlooks it all, its pillar cleverly disguising the chimney that once vented the steam engine powering the fountains—on Saturday nights, a stoker kept the engine running to pump water into the Round Pond so the fountains would have enough pressure to run on Sundays. This is where Cait and Jack exchanged their vows in Venomous Secrets, surrounded by water, marble, and Victorian engineering.

7) The Reptile House, London ZooThe original Reptile House opened in 1849 and now houses birds, but its legacy remains. For readers of Venomous Secrets, this location carries particular significance. As you walk through, you might find yourself eyeing the exhibits with the same wariness as our characters—wondering what venomous creatures might lurk just out of sight.

The original Reptile House opened in 1849 as the world’s first purpose-built reptile house at any zoo. It was replaced by the Blackburn Pavilion in 1882-83—a red-brick building in the classical style popular for garden pavilions at the time. Inside its lofty hall, three ponds were set into the floor, the largest housing crocodiles, while hot-water pipes ran beneath to direct heat to the reptile enclosures. When a new Reptile House was built in 1926, the Blackburn Pavilion was converted to house birds in 1927-28, a role it continues today as one of the few 19th century animal houses at London Zoo still in use.

A Reflection of Shadows

8) Ye Olde Mitre, Hatton Garden

A Reflection of Shadows

8) Ye Olde Mitre, Hatton Garden

Tucked down an alleyway off Hatton Garden in London’s jewelry quarter, this historic pub dates back to 1547. Originally built for the servants of the Bishop of Ely’s palace, it once technically belonged to Cambridgeshire rather than London, creating an urban legend that criminals could evade arrest by seeking sanctuary here, beyond the jurisdiction of the Metropolitan Police.

The pub served as inspiration for The Three-Eyed Bat in A Reflection of Shadows, and once you step inside, you’ll understand why. The atmosphere transports you centuries back—dark Tudor-style paneling installed in the 1930s covers the walls, heavy oak furniture fills two cozy rooms separated by a central bar, and pewter mugs hang from the rafters. In the corner near the entrance, behind glass, sits the preserved trunk of a cherry tree that once marked the boundary between the Bishop’s garden and land leased to Sir Christopher Hatton, Queen Elizabeth I’s favorite courtier. Legend claims she danced around this tree with Hatton, using it as a makeshift maypole.

Flight of the Scarab

9) Highgate Cemetery

Flight of the Scarab

9) Highgate Cemetery

For those drawn to the beautiful and macabre, Highgate Cemetery is essential. Walk through the Egyptian Avenue—a city of the dead flanked by two imposing obelisks. In the Circle of Lebanon, you’ll find Egyptian vaults arranged around where a magnificent Cedar of Lebanon once stood at their center. The tree stood for nearly two centuries before succumbing to age in 2019. Despite the theme, it’s unlikely you’ll find yourself invited to a mummy unwrapping party…

10) The British MuseumThe museum houses over 100,000 Egyptian artifacts spanning from 10,000 BCE through the Roman period—the largest collection outside Cairo. The museum houses over 100,000 Egyptian artifacts spanning from 10,000 BCE through the Roman period—the largest collection outside Cairo. For those interested in historical mycology look for wooden tomb models showing brewers straining mash through cloth into ceramic vessels—visual evidence of ancient fermentation processes. Seek out the three-cornered loaves of bread preserved from the 11th dynasty temple at Deir el-Bahri, and the ceramic brewing vessels that still show evidence of heat exposure from the beer-making process.

Pack your walking shoes! London never runs out of hidden corners to explore. Whether you’re wandering its alleyways or turning the pages of a book, there’s always another story waiting to be uncovered. I hope this list helps you see the city—and my stories—in a new light.November 10, 2025

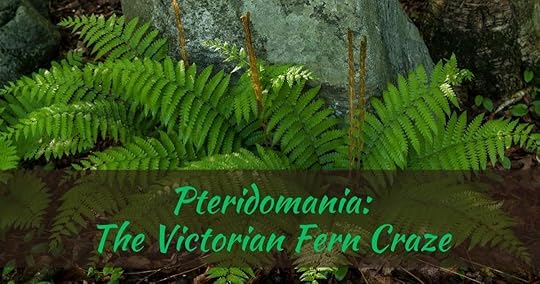

Pteridomania: The Victorian Fern Craze

Enter Lady Angela, a botanist with a photosynthetic tattoo of a fern on her arm…

During the 1880s and 1890s, British courts prosecuted “botanical criminals”—citizens caught trespassing on private estates to steal ferns. Common plants that once grew wild across Britain had become valuable enough to risk criminal charges. This was pteridomania at its peak.

What Was Pteridomania?Charles Kingsley coined the term “pteridomania” combining the Greek word for fern (Pteridophyta) with “mania.” From the 1840s through the 1890s, Britain was consumed by fern fever. Fern motifs appeared on textiles, wallpaper, jewelry, and pottery. Parlors displayed pressed specimens in albums. The wealthy built elaborate glass ferneries.

The Wardian CaseIn 1829, London physician Dr. Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward accidentally discovered that ferns could thrive in sealed glass containers. He had placed a moth chrysalis in damp soil inside a sealed bottle and noticed a fern spore germinated and flourished without additional water or care. This led to the Wardian case—a miniature greenhouse that protected delicate plants from London’s coal smoke and pollution. These cases became essential Victorian status symbols, making it possible to grow ferns indoors for the first time.

Why Ferns?Democratized Science. The Victorian era made natural history accessible across all social classes. Fern collecting required only a basket and countryside access—a vasculum (specialized metal case lined with damp moss) kept specimens fresh during transport.

Railway Expansion. The 1840s brought hundreds of miles of new railway lines, connecting city dwellers to remote Scottish borders, Welsh hills, and Devon valleys. Weekend collecting expeditions became possible for the first time.

Women’s Freedom. While women were (mostly) excluded from physics and chemistry, botany was considered appropriately feminine. More significantly, fern hunting provided rare social permission for women to venture unchaperoned into the countryside for all-day expeditions—a subtle form of Victorian rebellion.

The Glasshouse Boom. After the 1851 Crystal Palace Exhibition’s success, middle-class families added conservatories to their homes. Ferns thrived in these warm, humid environments.

The BiologyFor centuries, ferns puzzled naturalists because they produced no flowers or seeds. European legends claimed invisible fern seeds granted invisibility, restored sight, or revealed buried treasure. The Red Fern Flower supposedly bloomed only at midnight on Midsummer’s Eve, granting riches and the ability to understand animal language.

By the Victorian era, scientists had discovered that ferns reproduce via spores through a complex two-stage life cycle unlike flowering plants. Rather than dispelling the mystery, this explanation deepened public fascination with these ancient plants.

Environmental DevastationOverharvesting caused severe damage still visible today:

Killarney fern: Disappeared from most of Scotland and southwest EnglandOblong Woodsia: Numbers plummeted in the Moffat Hills, once home to Britain’s most extensive populationsDickie’s bladder-fern: Completely eradicated from its type locality (original discovery site) in Kincardineshire by 1860, though the species has since recovered elsewhere The Black MarketDemand exceeded supply by the 1860s. Commercial dealers hired guides to strip remote habitats, stockpiling rare species in greenhouses for year-round sale. Wealthy collectors paid extraordinary sums—ten to twenty pounds for a single rare specimen when a housemaid earned twelve pounds annually. Courts regularly prosecuted fern thieves throughout the 1880s and 1890s as private estates were plundered for rare specimens.

The DeclinePteridomania began fading in the 1890s and ended with Queen Victoria’s death in 1901. The craze left permanent marks: it established amateur naturalism across all social classes, gave women access to scientific observation and collection, and demonstrated how public enthusiasm could drive both scientific advancement and environmental destruction.

Icy Betrayals My novel ICY BETRAYALS is set in 1885 at pteridomania’s height, when Wardian cases filled fashionable homes and collectors faced prosecution for fern theft. Lady Angela, a botanist with a photosynthetic fern tattoo, exists in a world where the scientific and the magical intersect—where ferns hold secrets beyond what Victorian naturalists could diagram or classify.

My novel ICY BETRAYALS is set in 1885 at pteridomania’s height, when Wardian cases filled fashionable homes and collectors faced prosecution for fern theft. Lady Angela, a botanist with a photosynthetic fern tattoo, exists in a world where the scientific and the magical intersect—where ferns hold secrets beyond what Victorian naturalists could diagram or classify.

FURTHER READING

Whittingham, Sarah. Fern Fever: The Story of Pteridomania. Frances Lincoln, 2012.

Kingsley, Charles. Glaucus, or the Wonders of the Shore. 1855.

Keogh, Luke. The Wardian Case: How a Simple Box Moved Plants and Changed the World. University of Chicago Press, 2020.

Pteridomania: The Victorian Fern Craze | Anne RenwickNovember 6, 2025

Wish There Was More? Read The Elemental Web Tales

Did you finish The Elemental Web Chronicles but aren’t quite ready to leave its world?

Did you finish The Elemental Web Chronicles but aren’t quite ready to leave its world?The Elemental Web Tales are stories set in the same world, filled with science, secrets, and love.

Each book stands alone, so you can jump in anywhere and know every couple finds their happily ever after.

Which story calls to you next?

✨ A rogue frog and a rekindled love — A Trace of Copper

✨ A castle, a dragon, and a man worth trusting again — In Pursuit of Dragons

✨ A rooftop thief and the spy who loves her — A Reflection of Shadows

✨ A midnight kiss, a rare manuscript, and a murderer on the loose — A Snowflake at Midnight

✨ A ghost doomed to repeat his murder… until she arrives — A Ghost in Amber

✨ Groundhogs run amok, ancient bones, and love dug back up — A Whisper of Bone

✨ A clockwork scarab, a fairy ring, and a second chance at forever — Flight of the Scarab

Wish There Was More? Read The Elemental Web Tales | Anne RenwickOctober 28, 2025

Snail Slime Secrets: The Surprisingly Real Science

While writing A GHOST IN AMBER, I was set on having my heroine, Lady Diana Star, be a malacologist. A what? Someone who studies mollusks (then a-new-to-me-term). Even better, she would be fascinated by fossilized snails… especially as she possessed a necklace with a snail embedded in amber. But how to tie this to a plot? I dove down research rabbit holes. And discovered that snail mucus had been used medically as a healing agent for over 2,000 years – and is even now the basis for cutting-edge biomaterials. And it’s excellent for treating steam burns. Perfect for the 19th century and the Age of Steam.

Ancient Wisdom, Victorian CuriosityThe medicinal use of terrestrial mollusks stretches back to antiquity. Ancient Greek physicians, including Hippocrates himself, prescribed crushed snails mixed with sour milk for inflammations and burns. Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder documented numerous snail-based remedies in his encyclopedic Natural History. Throughout medieval Europe, snail preparations appeared in herbals and medical texts for treating wounds, coughs, and skin conditions. By the Victorian era, natural philosophy and the emerging field of zoology were experiencing a golden age. Amateur naturalists and professional scientists alike collected, catalogued, and experimented with creatures great and small. A scientifically-minded man like our hero, Lord Leo Wraxall, would have had access to both folk knowledge and emerging scientific journals. What was he working on?

The Snail’s Secret: A Natural Healing SerumModern molecular biology has revealed what ancient healers observed empirically: snail mucus is an extraordinarily complex biological cocktail designed for protection, adhesion, and repair.

Three Types of MucusGarden snails (Cornu aspersum, formerly Helix aspersa) produce three distinct secretions each with its own mechanical properties and molecular composition:

Adhesive mucus from the foot surface—allowing them to climb wallsLubricating pedal mucus for smooth locomotionProtective mucus that shields against environmental threats, pathogens, and UV radiationMolecular MagicResearch into Cryptomphalus aspersa (a related species) has identified the molecular mechanisms behind snail mucus’s regenerative properties:

Antioxidant enzymes that protect cells from oxidative damageGrowth factors that stimulate fibroblast proliferation and migrationGlycosaminoglycans that promote extracellular matrix assembly and tissue scaffoldingAntimicrobial peptides that prevent infectionMatrix metalloproteinase regulators that control tissue remodelingBasically, snail mucus tells your skin cells to multiply faster and move to where they’re needed. It helps new skin cells stick together properly and signals deeper tissue cells to build new connective structure. Researchers have identified over 70 different proteins in snail mucus. About one-third of these are completely unknown to science—they don’t match anything in our protein databases.

Burns and BeyondA landmark clinical study tested Helix aspersa extract on partial-thickness burns with stunning results:

Faster healingQuicker epithelialization (wound closure)Reduced painBetter outcomesThe snail extract wasn’t just effective—it was more effective than the standard medical treatment, with the added benefit of being less painful.

The Hydrogel ConnectionModern burn treatment increasingly uses hydrogels—water-swollen polymer networks that maintain a moist wound environment while allowing oxygen exchange. They cool burns, reduce pain, prevent infection, and promote faster healing without adhering to the wound bed. Here’s where Victorian science and modern medicine beautifully converge: snail mucus is nature’s hydrogel that:

Maintains moisture balanceCreates a protective barrierDelivers bioactive healing compoundsConforms to irregular wound surfacesCan be easily removed without traumaA 19th-century scientist with access to fresh snail mucus could have created an effective topical treatment that functioned much like modern hydrogel dressings—centuries before polymer chemistry made synthetic versions possible.

Snail-Inspired BiomaterialsModern researchers are taking snail science far beyond burn treatment, developing materials that sound like science fiction: Reversible superglue inspired by the dried mucus “door” snails make to seal their shells can hold an adult human with just two postage-stamp-sized pieces. Add water and you can unstick it, reposition it, and use it again Diabetic wound patches using snail compounds have healed chronic wounds in animals with a single application by calming inflammation and jump-starting tissue regeneration and blood vessel growth Tendon repair patches with one sticky side and one healing side reduced scarring by 25% in animal studies, staying in place for weeks Glowing bio-adhesive from a New Zealand freshwater snail could let surgeons actually see where they’re bonding tissue during operations, eliminating guesswork in delicate repairs.

Science Meets StoryThe snail mucus revelation opened a beautiful narrative door: my characters could use genuine science—knowledge that actually existed in folk tradition and natural philosophy—while appearing ahead of their time.  The best part? The science in A GHOST IN AMBER isn’t fantasy at all. Perfect for a ghost story where past and present collide.

The best part? The science in A GHOST IN AMBER isn’t fantasy at all. Perfect for a ghost story where past and present collide.

Consumer Products

Clinical & Scientific Studies

Comparative mucomic analysis of three functionally distinct Cornu aspersum Secretions

Molecular basis for the regenerative properties of a secretion of the mollusk Cryptomphalus aspersa

Innovative Biomaterial Applications

Glowing snail mucus: The sticky future of biomaterials

Janus, hydrogel inspired by snail slime that accelerates the care of the tendons

Reversible superglue mimics snail slime

A natural biological adhesive from snail mucus for wound repair

Hydrogel Wound Care (Content warning: contains images of treated burns)

When and How to Use Hydrogel for Wound Care: When Are They the Right Choice?

Snail Slime Secrets: The Surprisingly Real Science | A Ghost in Amber | Anne RenwickOctober 25, 2025

Scotland’s Cat-sìth: Where Folklore, Language, and Night Vision Collide

I wanted to write a story about a heroine who could see and move in the dark like a cat. A woman who belonged to the shadows, who could slip through darkness with feline grace. And when I stumbled across the Cat-sìth—pronounced “caught shee”—I knew I’d found a myth I needed to include.

The Cat-sìth is a creature from Highland legend: a fairy cat said to prowl the shadows of Scotland, as large as a dog and marked by a single white patch on its chest. Some believed it could steal a soul before it reached the afterlife. Highland communities developed elaborate rituals to keep the Cat-sìth away from their dead—constant vigils, avoiding loud noises, and refusing to light fires that might draw its attention. They’d distract the creature with games, music, and riddles through the night.

Some thought it a guardian that moved between worlds, a creature that walked the liminal spaces. Was it a witch who could transform into a cat nine times? A fairy in feline form? The stories change depending on who’s telling them and where in Scotland you’re standing.

Stories of the Cat-sìth might have originated from sightings of the Kellas cat, a striking black hybrid of wildcat and domestic feline that haunts the Scottish Highlands even today? As with most folklore, truth and imagination blur beautifully together.

The Language of LegendsWhen I first started researching details for my character, I assumed the Highlands spoke primarily Scottish Gaelic. And while Gaelic certainly influenced the region, I discovered that Scots—a Germanic language distinct from both English and Gaelic—was more widely spoken across much of Scotland, including Aberdeenshire where Colleen’s family has roots.

The word “Cat-sìth” itself is Scottish Gaelic: “cat” meaning cat and “sìth” meaning fairy or supernatural being. This is the same “sìth” you’ll find in banshee (bean-sìth, or “fairy woman”). But the everyday language of many Scots—the tongue Colleen speaks to her Cat-sìth companion—is Scots itself, with its own rich vocabulary and cadence.

Scots isn’t a dialect of English, though many assume it is. It’s a sister language with roots in Old English and Norse, shaped by centuries of Scottish history. Words like “braw” (fine), “wee” (small), and “ken” (know) are distinctly Scots. When Colleen murmurs to her black cat in the shadows, she’s using the language of her heritage, the tongue that feels most natural when speaking to a creature that shares her otherness.

The linguistic landscape of Scotland has always been complex—Gaelic in the Highlands and Western Isles, Scots in the Lowlands and much of the east and northeast, with countless local variations and borrowings between them. This layering of languages mirrors the Cat-sìth itself: a creature caught between worlds, belonging fully to neither yet recognized by both.

From Legend to Lady ColleenWhen I began writing A Reflection of Shadows, I couldn’t resist weaving this legend into Colleen Stewart’s story. My heroine isn’t entirely ordinary—her golden eyes gleam in the dark, and she moves through shadows with the silent grace of a predator. Her black Cat-sìth companion mirrors her own nature: half seen, half suspected, both feared and misunderstood.

Here’s where science steps in. The tapetum lucidum—a reflective layer behind the retina that helps nocturnal animals see in low light—offered the perfect bridge between myth and biology. What if that shimmer in Colleen’s eyes isn’t just poetic metaphor? What if it’s the echo of something ancient, something that hints her Scottish bloodline carries more than just family stories?

I’ve always loved blending the fantastical with the plausible—where folklore meets physiology, where a bit of Victorian science can make the impossible feel just within reach. The Cat-sìth became my symbol of the outsider, that creature caught between worlds—neither tame nor wild, mortal nor fae. Much like Colleen herself, a woman who refuses to apologize for being different.

An Invitation Into ShadowSo if you’re drawn to stories where Scottish legend tangles with steampunk invention, where a heroine speaks Scots to her Cat-sìth companion in the darkness, where ancient bloodlines meet Victorian science, I invite you to step into A REFLECTION OF SHADOWS.

Join Lady Colleen Stewart as she races across London’s rooftops with golden eyes gleaming and shadows bending to her will. Discover what happens when a thief with a Cat-sìth’s nature falls for a Queen’s agent, when folklore runs through in gaslit streets, and when being different becomes the ultimate advantage.

Join Lady Colleen Stewart as she races across London’s rooftops with golden eyes gleaming and shadows bending to her will. Discover what happens when a thief with a Cat-sìth’s nature falls for a Queen’s agent, when folklore runs through in gaslit streets, and when being different becomes the ultimate advantage.

October 24, 2025

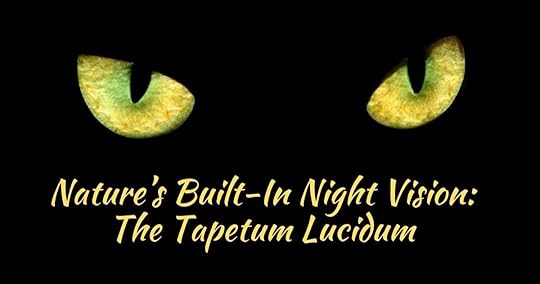

Nature’s Built-In Night Vision: The Tapetum Lucidum

If you’ve ever snapped a photo of your cat with a flash or caught a deer staring back at you from the headlights, you’ve witnessed one of nature’s most ingenious adaptations. Those glowing eyes aren’t generating light—they’re reflecting it, thanks to a remarkable structure called the tapetum lucidum.

What Is the Tapetum Lucidum?Latin for “bright tapestry,” the tapetum lucidum is a reflective layer of tissue behind the retina in the eyes of many nocturnal and crepuscular animals. Think of it as a biological mirror that gives incoming light a second chance to reach the photoreceptor cells in the retina.

When light enters the eye, some is absorbed on its first pass. The rest hits the tapetum lucidum and bounces back through the retina for a second opportunity to be detected. This effectively amplifies available light, dramatically enhancing vision in low-light conditions.

In fiction, this adaptation makes for a fascinating trait. In A REFLECTION OF SHADOWS, Lady Colleen Stewart possesses a human version of this ability, giving her enhanced night vision that aids in her rooftop escapades across London. Her black Cat-sìth companion also has a tapetum lucidum, reflecting the shared evolutionary connection between her lineage and cats—a trait that helps both of them navigate darkness with ease.

Who Has It?The tapetum lucidum appears in a surprisingly diverse range of creatures:

Carnivores: Cats, dogs, and other predators rely on it to hunt at dawn, dusk, or night.

Ungulates: Deer, horses, and cattle use it to detect predators in dim light.

Marine animals: Many fish and some sharks use it to navigate murky depths.

Others: Even some spiders, alligators, and lemurs have it.

Interestingly, most primates—including humans—lack a tapetum lucidum. Our ancestors evolved as diurnal creatures who relied on color vision, which performs best in bright daylight. But for Colleen and her Scottish lineage, evolutionary quirks allow her to gain abilities akin to her feline companions—climbing, leaping, and moving through the shadows in ways that leave others in the dark.

The Science of EyeshineThat eerie glow you see in animal eyes at night—known as eyeshine—varies in color depending on the species and the tapetum’s composition. Materials like zinc, riboflavin, or collagen crystals reflect light differently.

Cats: Typically greenish-gold

Dogs: Yellow-green, blue, or white

Alligators: Distinctive red

In Colleen’s world, her own golden eyes echo the same principle—reflecting light in darkness, giving her an edge when sneaking through London streets or spotting danger before anyone else.

The Trade-OffLike most evolutionary adaptations, the tapetum lucidum comes with a cost. While it increases light sensitivity—some studies suggest up to 50% more light reaching the photoreceptors—it can slightly reduce visual sharpness. The reflected light scatters, creating a subtle blurring effect.

For animals that need to detect movement or shapes at night, the trade-off is worth it. A slightly blurrier image you can actually see is far more valuable than a perfectly sharp one that’s cloaked in darkness.

For Colleen, this trade-off is trivial compared to the freedom it affords her: she can chase down a suspect, leap between rooftops, or tail a target in shadows where others see nothing. A slightly blurrier image in near-darkness is far more valuable than being blind to danger entirely.

An Evolutionary MarvelThe tapetum lucidum has evolved independently in multiple animal groups—a phenomenon known as convergent evolution. This underscores just how valuable enhanced night vision is for survival—whether in nature or fiction.

Next time you spot glowing eyes in the dark, pause for a moment to appreciate this elegant natural engineering.

And if you pick up A REFLECTION OF SHADOWS, you’ll join a heroine in possession of this night-vision, racing across rooftops and slipping through shadows with feline grace.

Nature’s Night Vision: The Tapetum Lucidum | A Reflection of ShadowsOctober 22, 2025

When Left is Right: The Mystery of Sinistral Snails and Halloween Magic

On All Hallows’ Eve

On All Hallows’ EveYou’re exploring a moonlit graveyard when something catches your eye — dozens of snails glowing softly in the shadows, all spiraling in the same peculiar direction. As a malacologist (that’s a snail scientist, for the uninitiated), you’d know immediately that you’ve stumbled upon something extraordinary. These aren’t ordinary garden snails. They’re all sinistral — left-handed — and in the world of gastropods, that’s about as rare as finding a unicorn.

This is exactly what happens to Lady Diana Starr in my novel, A GHOST IN AMBER. But before you run off to read about how she accidentally walks counterclockwise around an ancient yew tree and tumbles back through time, let’s explore the fascinating science behind what makes these left-spiraling shells so special.

Snail CoilsHave you ever noticed that most snail shells always curl in the same direction? It’s not random at all. A snail’s spiral forms early in development through a process called gastropod coiling. As the embryo grows, the snail’s body twists in a process called torsion, which makes the shell grow in a spiral and rearranges its organs to match. The end result is a coil that allows the snail tuck itself safely inside when danger strikes.

Most snails are what we call dextral, meaning their shells spiral to the right. If you hold a snail with the pointy tip (apex) up and the opening facing you, the opening will be on the right-hand side. Over 90% of snails are right-coiled like this, which makes it easy for them to find mates — everyone’s anatomy lines up the same way. It’s the “standard model” of snail design.

But sometimes, nature throws us a curveball: sinistral snails, whose shells spiral to the left. These lefties are rare, and their mirrored bodies can make it hard to mate with the right-handed majority. One famous example is Jeremy, a garden snail who made headlines in 2016 because he couldn’t find a compatible mate. Scientists launched a worldwide search and finally found him two left-coiled partners — a heartwarming (and scientifically fascinating) story that helped researchers study how coiling direction is inherited.

How Snails Get Their “Handedness”Coiling direction isn’t random — it’s coded in a snail’s DNA. In most species, the direction is controlled by a single gene expressed very early in the embryo. Here’s the twist: it’s mom’s genes, not the baby’s, that decide whether the shell will spiral right or left — something known as maternal effect. Left-coiling is usually a recessive trait, which is why sinistral snails like Jeremy are so rare.

Scientists have pinpointed this remarkable trait to a gene called Lsdia1, which guides how a snail’s body establishes its left-right asymmetry through proteins known as formins. The mother’s genetic contribution sets the coiling direction before her offspring even begin their first cell divisions. Research by Reiko Kuroda’s team revealed that turning this gene off can flip the entire spiral — a tiny molecular change with dramatic consequences for the snail’s shape and reproductive fate.

Word Origins: Dextral vs. SinistralThe terms we use for snail coiling actually come from Latin. Dextral comes from dexter, meaning “right” or “skillful” — it’s the same root we get “dexterity” from. Sinistral comes from sinister, meaning “left,” though in the past it also meant “unlucky” or “wrong.” (Medieval Europeans were suspicious of left-handedness.) Today, scientists use the words neutrally — no judgment implied — but they’re a great reminder of how language shapes our view of the natural world.

If it helps, you can think of dextral coiling as clockwise and sinistral as counterclockwise when you look at the shell from the top. That visual makes it easier to spot which kind of snail you’re holding.

Folklore Focus: Walking WiddershinsAnd here’s where things get a little spooky. In my book, A GHOST IN AMBER, a rare sinistral snail and a counterclockwise walk around an ancient yew tree pull our heroine back through time.

The word widdershins comes from Middle High German and literally means “against the way.” It refers to moving counterclockwise — the opposite of the sun’s path across the sky. In European folklore, this direction was linked to magic, mischief, and crossing into the otherworld. Witches were said to dance widdershins at their Sabbaths, and Halloween rituals sometimes used counterclockwise motion to summon spirits or break curses. Far from being purely sinister, widdershins was also seen as a way to undo bad luck — or to escape ordinary reality altogether.

Lady Diana’s discovery of an entire colony of left-spiraling snails is no coincidence. These rare creatures, with their counterclockwise shells, are nature’s embodiment of the widdershins principle. When she wanders around the graveyard and the ancient yew tree—three times counterclockwise, as the old legend demands—she doesn’t just observe scientific curiosities. She becomes part of the magic.

When Science Becomes EnchantmentAs a historical fantasy romance author, I love finding those moments where science intersects with folklore. The fact that Jeremy’s left-handed legacy helped modern geneticists understand heredity would have seemed like pure magic to a Victorian malacologist. And Lady Diana’s expertise — her ability to spot those sinistral shells in the moonlight — becomes the key that unlocks her greatest adventure.

Sometimes the most extraordinary discoveries happen when we pay attention to nature’s rebels: the left-handed snails, the counterclockwise walkers, the ones who dare to spiral against convention. In Jeremy’s case, being different led to worldwide fame and scientific breakthrough. For Lady Diana, it leads to something even more precious — a love that transcends time itself.

Anyone have plans to walk widdershins around an old tree in a graveyard this coming All Hallows’ Eve? Maybe play it safe and read

A GHOST IN AMBER

instead.

Anyone have plans to walk widdershins around an old tree in a graveyard this coming All Hallows’ Eve? Maybe play it safe and read

A GHOST IN AMBER

instead.

October 1, 2025

Þingvellir: Where Iceland’s History and Nature Collide

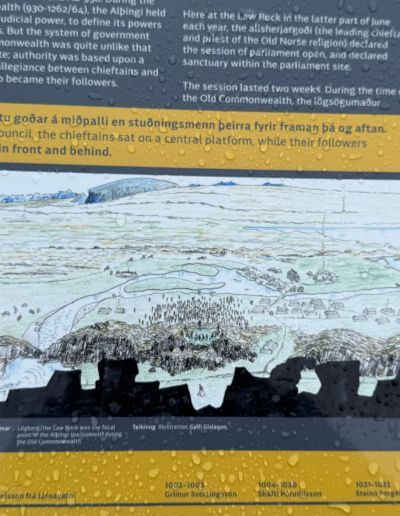

In 930 CE, Icelandic chieftains gathered at Þingvellir to establish the Alþingi, one of the world’s oldest parliaments. For centuries, this outdoor assembly met annually at Lögberg (Law Rock), where laws were recited, disputes were settled, and the nation’s fate was decided.

In 1000 CE, it was here that Icelanders made the momentous decision to adopt Christianity, averting civil war through compromise rather than conflict.

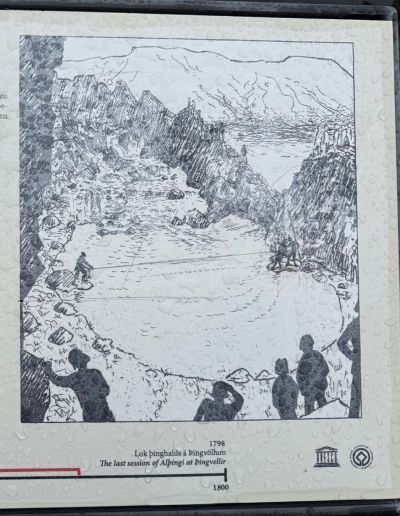

In 1262, they yielded authority to the Norwegian King. After this, the assembly continued to meet, but their power diminished. The last assembly here in Þingvellir took place in 1798.

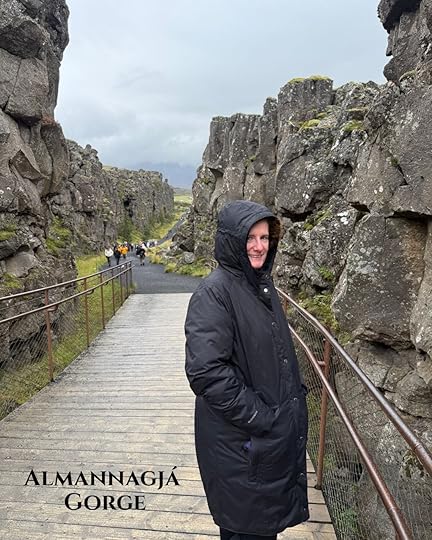

Five Must-See Wonders from Icy Betrayals 1) Almannagjá GorgeWalk between two continental plates along this dramatic rift valley. The pathway through Almannagjá offers the experience of literally standing between North America and Eurasia as they drift apart at about 2 centimeters per year. The gorge is approximately 7.7 kilometers long and up to 64 meters wide in places. The walls tower 40 meters high on either side of the walking path. This split formed from thousands of years of tectonic activity and earthquakes. The last major earthquake here was in 1789, which dropped the valley floor by about one meter overnight.

The first time we visited (April 2024) the landscape was still snow-covered. And the walkways hadn’t quite melted, so we (and others) were clutching the handrail on our way down between the rocky cliffs – hence the lack of photos. On our second visit (Sept. 2025), I stopped for a photo. It was cold up at the top of the gorge, but as we descended, the cliffs blocked the wind.

Iceland’s largest natural lake covers 84 square kilometers. Underground springs feed the lake with water that has filtered through porous lava rock, which is why the water stays crystal clear year-round. Silfra, a deep fissure at the edge of the lake, makes for a popular place to snorkel between the two tectonic plates. The water temperature remains cold, between 4-10°C depending on the season.

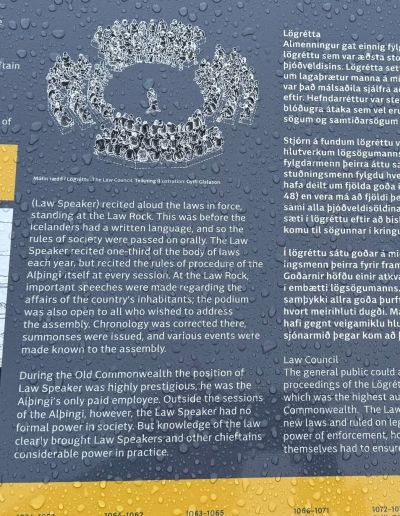

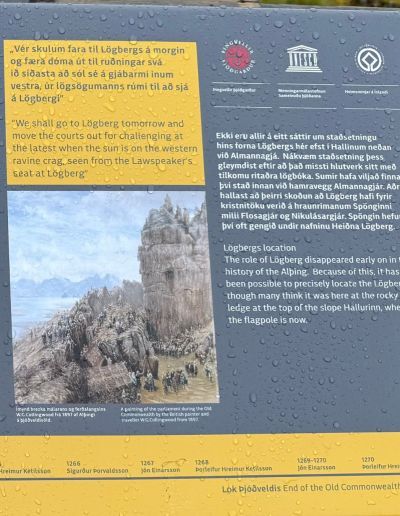

3) Lögberg (Law Rock)

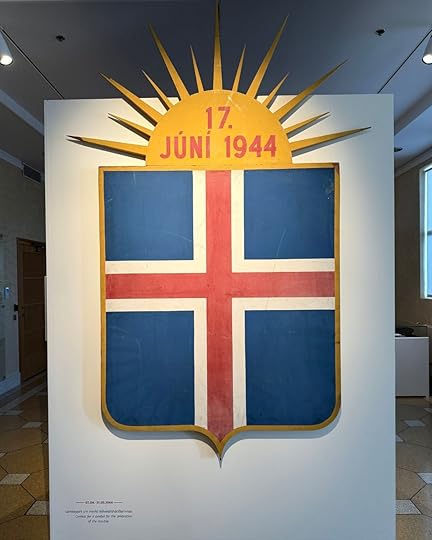

3) Lögberg (Law Rock) Though the exact location remains debated by historians, the marked site of the Law Rock is where the Lawspeaker recited Iceland’s laws from memory to the assembled crowd. The position was created in 930 CE and continued until 1271. From this rock, major announcements were made that shaped Iceland’s future, including the declaration of independence from Denmark in 1944, when thousands gathered to hear the proclamation at this historic site.

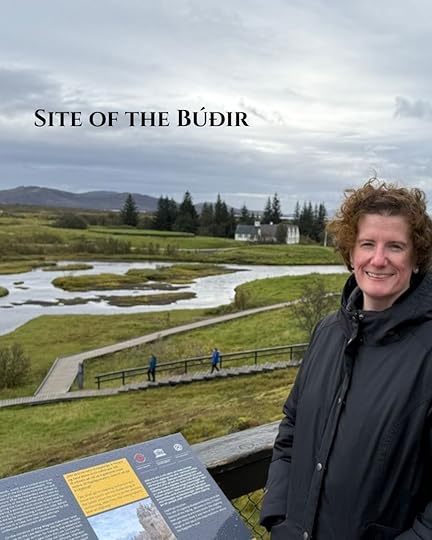

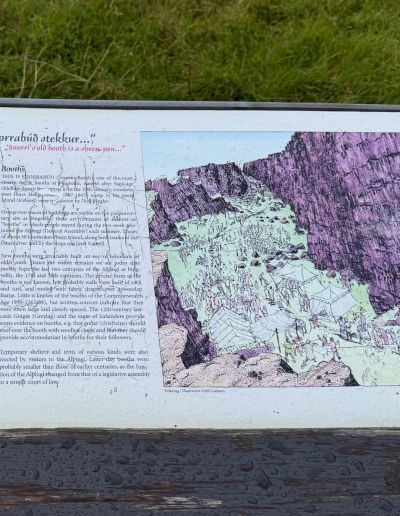

4) The Búðir (Booth Sites)

4) The Búðir (Booth Sites)Scattered across the plains are the remnants of temporary booths where Viking-age Icelanders camped during the two-week assembly. Chieftains and their retinues erected turf-and-stone shelters, creating a temporary tent city that could house hundreds. These ancient camping spots, visible as low stone foundations, show where deals were brokered, marriages arranged, and alliances forged around campfires under the midnight sun.

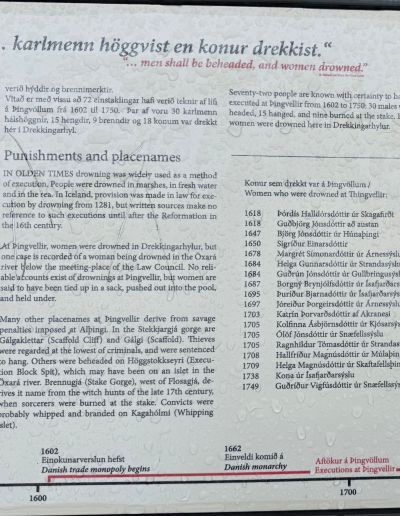

5) Drekkingarhylur (The Drowning Pool)This pool in the Öxará River serves as a chilling reminder of medieval justice. Between 1602 and 1749, women convicted of crimes like adultery, infanticide, or perjury were drowned here, tied in a sack and submerged in the frigid waters. Men faced beheading instead. It’s a sobering testament to Iceland’s harsh past. Have a look at the video I took of this pool.

Þingvellir remains a defining symbol of Icelandic identity—birthplace of the Althing and a testament to centuries of democratic tradition. Today, as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, visitors can walk between shifting tectonic plates where history and geology converge in a dramatic landscape. A View from Lögberg (Law Rock) What with there being a rather important scene that takes place here, I took a minute to film a 360° for you. You’ll just need to use your awesome reader imagination skills to cover the landscape with snow.

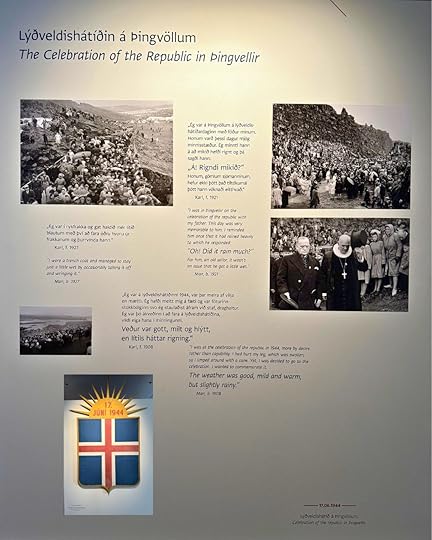

WHY set a critical scene upon Law Rock? Because when Iceland finally won independence from Denmark, this is how they celebrated:

Information Signs – click on the image to expand

Information Signs – click on the image to expand

Þingvellir: Where Iceland’s History and Nature Collide

Þingvellir: Where Iceland’s History and Nature Collide

September 20, 2025

A Timeline of Icelandic Rule

Iceland’s history is full of twists—settled by daring Norse explorers in the 9th century, it ran itself as an independent republic for centuries before falling under Norwegian, then Danish rule. In the 19th century its independence movement began. Through it all, Icelanders held on to their language, laws, and stories—providing me with the perfect backdrop to introduce you to huldufólk, trolls, and other Icelandic creatures.

Iceland’s history is full of twists—settled by daring Norse explorers in the 9th century, it ran itself as an independent republic for centuries before falling under Norwegian, then Danish rule. In the 19th century its independence movement began. Through it all, Icelanders held on to their language, laws, and stories—providing me with the perfect backdrop to introduce you to huldufólk, trolls, and other Icelandic creatures. 874–930 – Settlement period

Iceland is settled by Norse chieftains; no central ruler – authority is local, through clans and chieftains930–1262/1264 – Commonwealth (Þingvellir)

No king; governed by the Alþingi, an assembly of chieftains1262–1380 – Under the Norwegian Crown

Icelanders pledge allegiance to King Haakon IV of NorwayNorwegian kings rule through appointed officials

1397–1814 – Danish Rule (via the Kalmar Union and later Denmark)

1397: Norway enters Kalmar Union (Kingdoms of Denmark, Norway and Sweden); Iceland, under Norway, comes under Danish control as Queen Margaret I of Denmark consolidates power and places her grand-nephew Eric of Pomerania on the throne, effectively bringing Norway—and by extension Iceland—into a unified Scandinavian realm1660: Denmark becomes an absolute monarchy; Iceland governed as a Danish territory1800: The Aþing is abolished1814–1918 – Denmark after the Treaty of Kiel (factors that lead to the alt-history timeline of ICY BETRAYALS)

Denmark (on the losing side of the Napoleonic Wars) cedes Norway to Sweden; Iceland, Greenland and the Faroe Islands remain under Danish controlNorway resists and invades Sweden, but the short-lived independence movement ends with a treaty allowing Norway to keep its constitution while accepting the Swedish kingStarting in the 1830s, Icelanders begin to demand autonomy led by Jón Sigurðsson who campaigned for Icelandic self-governance, home rule, and legal reforms1843: Denmark allows Iceland to elect representatives to a re-established Althing, giving Iceland a limited legislative role1874: Iceland granted limited home rule under Christian IX, but still under Danish monarchy

1918–1944 – Kingdom of Iceland

Sovereign kingdom in personal union with Denmark: King Christian X of Denmark as monarchIceland controls domestic affairs; Denmark handles foreign policy

1944–Present – Republic of Iceland

17 June 1944: Iceland becomes a republic A Timeline of Icelandic Rule: From Settlement to Republic

A Timeline of Icelandic Rule: From Settlement to Republic

September 11, 2025

What Is Bioactive Glass? The Real Science Behind a Deadly Tattoo

Is the bioactive glass in my book ICY BETRAYALS real?

Yes – and no.

Bioactive glass – also called bioglass – is a glass-ceramic biomaterial that doesn’t just sit passively in the body. It bonds with living tissue and helps it heal.

The original formula, 45S5 Bioglass, was invented in 1969 by Dr. Hench and his team. They created a silicate-based glass made from silica, calcium, sodium, and phosphorus that could fuse with bone and act as a scaffold while the tissue rebuilt itself.

When this bioactive glass touches body fluid, it slowly dissolves, releasing minerals. Those minerals encourage a thin layer of hydroxyapatite (the same mineral that makes up bone) to form on the surface of the graft. Your cells then recognize it as “self” and begin rebuilding tissue until the bioactive glass is (mostly) replaced with your own bone.

Today, doctors sometimes use bioactive glass to fill bone defects, speed up slow-healing fractures, and even restore bone around teeth. Bioactive glass is used in some dental treatments, while related toothpastes containing nano-hydroxyapatite can be purchased to help repair microscopic cavities and reduce tooth sensitivity, though fluoride-based toothpastes remain the gold standard.

Beyond bone repair, researchers are now discovering that bioactive glass can also help heal soft tissues like skin wounds by regulating inflammation and promoting blood vessel growth. Early studies show promise for treating chronic wounds, burns, and even post-surgical healing.

And in ICY BETRAYALS? I take this very real science, twist it, and reinvent bioactive glass as a fictional substrate for a glowing, living tattoo…

What Is Bioactive Glass? The Real Science Behind a Deadly Tattoo