Daniel Schulof's Blog

July 31, 2019

The Facts About Grain-Free Diets and Canine Dilated Cardiomyopathy: Part Two — The Scandal

I wrote part one of this two-part series in August 2018. At the end of it I told readers to expect part two in “about a month.”

That was about a year ago.

So why’d it take so long? In short, I’ve come to believe there’s a scandal at the heart of the matter and it has taken me longer than I expected to develop the evidence documenting everything. Sorry for the delay, but once you get through this post, I hope you’ll be understanding.

In the course of discussing this issue with journalists, scientists, veterinarians, and everyday pet-owners over the past few months, one problem I’ve repeatedly encountered is that it takes a long time to explain it all. There’s a great deal of material to unpack. So, if you’re time-limited, there are three pieces of writing you should consider:

1) This short op-ed I wrote for CrossFit. CrossFit has fought back (and won!) against an industry-funded scientific misinformation campaign very similar to the one that appears to be underlying the FDA’s DCM investigation. The company’s founder, Greg Glassman, recognized the FDA investigation for what it is and was good enough to invite me to publish on their website so I could explain everything to their readers.

2) This Medium article. It distills the primary information down into ten key take-homes for pet owners.

3) This website. If you want to read and support my request that the Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association retract a hugely popular but highly misleading article that is creating a false narrative about DCM, go there.

On with the facts.

The FDA’s investigation was initiated by a group of American veterinarians with financial ties to three pet food companies, Nestle-Purina Petcare, Mars Petcare, and Hill’s Pet Nutrition. Those three companies (which I’ll call “The Big Three” hereafter) all have something in common: they primarily sell grain-based, kibble-style pet foods and have a profit incentive to depress sales of the grain-free products with which they compete.

In addition to prompting the FDA investigation, this same group of veterinarians also co-authored an article about diet-associated DCM which was published in JAVMA last December. Their article has been wildly popular–over the past twelve months it has been the most widely-read article in the most widely-read veterinary science journal on the planet. At more than 80,000 downloads as of July 2019, it may be the most widely-read veterinary science article ever written.

Which is a problem, because I firmly believe that the article should be retracted. It grossly mischaracterizes the evidence surrounding its subject, it relies on anecdotes and conjectures instead of evidence, it misrepresents studies that were unpublished at the time it went to print, it was written by veterinarians with financial ties to the Big Three, it defames dozens (if not hundreds) of other pet food companies, and (perhaps most striking of all) its authors managed to cleverly avoid the peer-review process that ordinarily works to ensure that bad science writing isn’t published in academic journals.

It took me the better part of the year to develop all the evidence associated with these allegations. The investigation involved public records disputes at both the state and federal level, novel biochemical analyses conducted by an independent laboratory, statistical work, and more than a dozen interviews with veterinary nutritionists and animal scientists.

I condensed all of this into a draft report and presented it to Dr. Lisa Freeman (the corresponding author of the JAVMA article and a leading proponent of the supposed link between DCM and “BEG” pet foods) at the 2019 American Academy of Veterinary Nutrition Conference. She laughed at me. And, to date, she has offered no response.

But I also passed out a couple hundred copies of the report to the other attendees at the conference. And in the month that followed more than 200 veterinarians, animal scientists, representatives of “BEG” pet food companies, and other stakeholders co-signed it and endorsed the call for JAVMA to retract its problematic article.

Last Friday I finally delivered the retraction demand package to JAVMA‘s editor-in-chief, Dr. Kurt Matushek. Here’s a link. For the most part the materials speak for themselves. But a few items require some elaboration.

In two different cases, the JAVMA article cites studies conducted by its authors that were unpublished at the time the JAVMA article went to print. Both of these studies have now been published. And they both have problems of their own. Those problems are described in detail in my letter and summarized in the Medium article. One’s a mysterious case of disappearing data. The other is a glaring methodological abnormality.

A second issue is the accessibility of relevant governmental records under the Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”) and its various state-level analogues. As part of my investigation, I filed public records requests with a host of state offices and federal governmental agencies, including the public universities where several of the relevant veterinarians are employed, as well as with the FDA itself.

Thus far, the FDA has refused to produce any of the documents associated with its investigation into canine DCM. I believe this stonewalling to be unlawful. So I recently filed a federal lawsuit against the FDA, demanding that the records be produced to me in accordance with FOIA. You can read the lawsuit for yourself — I included a copy with the retraction demand package.

Some of the state universities have been more forthcoming. I have uploaded the e-mails, financial records, and other documents they produced to this online repository. I intend to continue updating these files as more relevant documents are produced to me over the months ahead.

And that gets to my final point: this is an on-going story and I’ll continue to update it. I’ll let you know when JAVMA makes a decision. I’ll let you know if any notable records get produced to me. I’ll cover any new science that gets published. And I’ll do my best to weigh-in when any relevant news drops.

Thanks for reading.

7/31 UPDATE: Just a few days after I published my retraction demand package, Ryan Yamka PhD, one of the most well-regarded and high-profile animal nutritionists in the country has also called for the JAVMA article to be retracted.

August 14, 2018

The Facts About Grain-Free Diets and Canine Dilated Cardiomyopathy: Part One – The Evidence (and How It Has Been Misinterpreted by Leading Veterinarians)

In a way, this piece is a reaction to a press release issued by the Food and Drug Administration earlier this month informing pet owners that the organization had begun investigating a potential link between diet and canine dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), an historically rare disease characterized by enlargement (dilation) of the heart muscles.

But, more specifically, it’s a reaction to the problematic way this news has been interpreted by a few leading veterinary experts. News of the FDA investigation was immediately seized upon and amplified by several of the country’s most visible veterinary nutritionists, including Dr. Lisa Weeth and Dr. Lisa Freeman. (The AVMA and several major international media platforms, including the New York Times, followed suit.) And, in every case of which I am aware, the take-home message was more or less the same—pet owners should view the FDA investigation as a reason to avoid “grain-free” pet foods.

In a blog post written just days after the FDA investigation was announced (entitled “In Defense of Grains”), Dr. Weeth characterized the investigation as being primarily about “grain-free pet foods.” And, in a Twitter post praising the FDA’s investigation, she warned her followers that “the grain-free #petfood trend may be doing more harm than good.”

Dr. Freeman went even further. On June 4, she published a lengthy article on a pet food blog linked to the Cummings Veterinary Medical Center at Tufts University, where she is a professor. The piece was entitled “A Broken Heart: Risk of Heart Disease in Boutique or Grain-Free Diets and Exotic Ingredients.” In it, she affirmatively advised pet owners currently feeding “grain-free” pet foods to “reassess whether you could change to a diet made with more typical ingredients,” citing the FDA investigation as the motivation for her recommendation.

(Other platformed veterinarians, such as Dr. Jessica Vogelsang and Dr. Alice Jeromin also broadcast more or less the same message: the FDA’s investigation is a reason to “get off the grain-free diet!”)

I’m writing this piece because I disagree profoundly with this interpretation of the FDA’s new investigation. I also believe that this interpretation is likely to cause harm, both to the pet food manufacturers that have been wrongly implicated (I am the founder and president of one such company) and the pets whose owners follow this “expert advice” and avoid food products that might otherwise provide evidence-based health benefits to their dogs.

The manner in which these prominent veterinarians are interpreting the FDA story is problematic for a whole host of specific reasons, all of which I discuss in greater detail below. Here’s a quick overview:

(1) Their recommendations are based on anecdotal reporting, not peer-reviewed scientific evidence. Such reasoning is completely inconsistent with what pet owners ought to expect from leading veterinary professionals, as both Dr. Weeth and Dr. Freeman themselves regularly tell their readers.

(2) The known etiology of canine DCM strongly suggests that the anecdotal reporting upon which these broad recommendations are based does not even support the recommendations in the first place.

(3) Moreover, while there isn’t any published experimental evidence suggesting a link between grain-free foods and an increased risk of canine DCM, there is peer-reviewed experimental evidence linking grain-based commercial pet foods with an increased risk of canine DCM.

(4) The evidentiary basis for the recommendations is simply dwarfed by the body of evidence supporting a related nutritional phenomenon, one with far more troubling public health implications, but which has consistently been ignored by leading veterinary nutritionists such as Drs. Weeth and Freeman—the health dangers associated with the consumption of dietary carbohydrates.

(5) The recommendation that consumers avoid all grain-free pet foods is certain to harm wrongly-implicated pet food manufacturers. But I believe it’s also likely to have, on the balance, a negative impact on the health of America’s dogs (by driving consumers towards more carbohydrate-focused products). In other words, it’s not just a poorly reasoned recommendation, it’s one that actively causes harm.

Now, I haven’t done much in-depth science writing since I published Dogs, Dog Food and Dogma in 2016. (Over the past two years, my professional life has primarily been focused on getting KetoNatural Pet Foods off and running.) But I still believe that modern-day pet owners are rarely given the informational material they need in order to make sound nutritional decisions for their pets. Given that, and given the fact that this is such a clear-cut case of flawed scientific reasoning infecting public discourse, I felt a strong compulsion to dive back into the fray, if only for a moment.

In the end, promotion of the theory that all grain-free pet foods ought to be avoided due to concerns over canine DCM is not only unsupported by the evidence, it is either an example of (at best) faulty scientific reasoning by veterinary professionals or (at worst) outright bad faith. In this piece, I’ll focus exclusively on the problems with the reasoning. But in a follow-up article, one which I expect to publish within another month or so, I’ll try to explain why some folks have gotten this one so wrong.

Now, onto the nitty-gritty. I’ll start with a few background facts and then present each of the five arguments above in greater detail.

Background

Grain-Free Diets

To properly understand the flaws in the position taken by some of America’s leading veterinary nutritionists, there are three things to note about grain-free pet foods.

The first is that they make up a mammoth chunk of the pet food market. According to PetFoodIndustry.com, 44% of dry dog foods and 47% of dry cat foods for sale in the United States today do not contain any grains. And that’s just the dry formulas! Raw, freeze-dried, dehydrated, and baked pet food products are almost always grain-free. This means that it is quite possible that most of the pet food sold in the United States today is grain-free. And, by most estimations, grain-free remains the fastest growing sector in the entire market—so if it’s not already the largest sector, it’s going to be soon.

The second thing to note about grain-free diets is that, as I have already written elsewhere, there is precisely zero persuasive evidence that grains are less healthful for dogs than other sources of dietary carbohydrates, such as tubers (potatoes) or legumes (peas). In that regard, I stand in complete agreement with Drs. Weeth and Freeman—there’s no good reason to believe that grain-free pet foods stuffed with starch are particularly healthful just because the starch doesn’t come from grains.

But there’s a third and final point about grain-free pet foods that’s also critical to understand. Which is that most of the high-meat, high-protein, low-carbohydrate pet food brands on the market today (whether raw, freeze-dried, kibble, or other) also happen to be grain-free. Grain-free is such a pervasive and well-understood sector of the market, and there’s such a meaningful amount of conceptual overlap between “grain-free” and “high-meat,” that producers of truly high-meat formulas have little choice but to also make sure their products don’t contain any grains. (Again, as the president of one such company, I have experienced this pressure first-hand.) Not all grain-free pet foods contain a lot of meat, but the vast majority of high-meat pet foods are grain-free.

Canine Dilated Cardiomyopathy

Now, to understand the significance of all this, we also have to understand a few background facts about canine dilated cardiomyopathy, the disease at the heart of the FDA’s new investigation.

First, note that canine DCM is a relatively uncommon disease, with existing evidence putting the lifetime incidence rate at perhaps 1.3-1.5% of dogs. (Only 10-11% of dogs will suffer from any form of cardiac disease whatsoever in their lifetimes. And, according to Kirk’s Veterinary Therapy XIV, a 2009 veterinary textbook, DCM accounts for about 13.6% of those.) Out of every one hundred dogs in the United States today, only one or two are likely to develop DCM in their lifetimes.

For context, consider that the AVMA estimates that about 25% of dogs will develop some form of cancer in their lifetimes. And veterinary surveys suggest that as many as half of the dogs in America today are overweight (a disease that is deadlier for a dog than a lifetime of smoking is for a human being). So one might say that cancer and obesity are, respectively, about 20 and 35 times more common than DCM. For every one case of canine DCM, there are likely 20 cases of canine cancer and 35 cases of canine obesity.

(This is not to suggest that DCM isn’t a serious (potentially fatal) disease for dogs in its own right. It is. But it isn’t remotely as common as either cancer or obesity, a fact whose significance I’ll explain below.)

Second, note that there is broad consensus in the veterinary community that a subset of canine DCM cases are caused at least in part by taurine deficiency. Taurine is an amino acid (the so-called “building blocks of protein”) found in the muscle tissue of animals, and in almost no other common pet food ingredients. Although they contain some amounts of several different amino acids, plants simply do not contain meaningful amounts of taurine.

According to AAFCO and the National Research Council, dogs don’t require any exogenous (dietary) taurine, because their bodies produce the stuff endogenously from other, more widely-available amino acid precursors (specifically, methionine and cysteine).

Cats, however, cannot conduct this transformative process nearly as efficiently as dogs can, which is why taurine is considered an “essential” amino acid for cats and why it is often said that cats are “obligate carnivores.” They need to eat meat because meat is about the only source of the taurine that their bodies require.

But, just like cats, dogs can still develop taurine deficiency. It’s just not necessarily the direct result of a lack of taurine in the diet. Studies have already documented cases of taurine deficiency-induced canine DCM that researchers attributed to either a lack of dietary cysteine or dietary methionine—the two amino acid precursors that the canine body naturally converts into taurine. And, as Dr. Freeman explained in her recent article, nutritional scientists have come up with several other theories that could explain how dogs might develop taurine deficiency:

“The reasons for taurine deficiency in dogs are not completely understood but could be reduced production of taurine due to dietary deficiency or reduced bioavailability of taurine or its building blocks, increased losses of taurine in the feces, or altered metabolism of taurine in the body.”

Evidence Linking Diet and Canine DCM

So, to what degree has a link between dietary factors and canine DCM already been established through valid, peer-reviewed scientific evidence?

Like Dr. Freeman, I read the evidence to suggest that there is very likely a causal link between diet and canine DCM. More specifically, it seems clear to me that a diet deficient in some combination of taurine, methionine, and cysteine can cause a dog to develop taurine deficiency, which can lead to DCM.

The FDA’s new investigation seems to be an attempt to further clarify this relationship. Is it the case that some dogs require more dietary taurine, cysteine, or methionine than the relevant nutritional guidelines currently provide? Are some pet food products failing to meet those guidelines in the first place (regulatory pre-clearance is not required and studies have documented various nutritional deficiencies in the past)? Or could it be a question of bioavailability—are dogs actually able to absorb the amino acids found in certain products or ingredients?

Fundamentally, a spike in DCM cases could be attributable to any number of these factors. But what seems perfectly clear is it’s not in any way related to the presence or absence of grains in a diet. The issue almost certainly has nothing to do with whether or not a product is grain-free.

Why? It’s simple. Grains such as corn, wheat, and rice just aren’t particularly special when it comes to amino acids. Like most other plants, they don’t contain any detectable amounts of taurine. And, just like other plants, they also contain less bioavailable cysteine and methionine than the meat products and byproducts that are commonly used in pet foods.

And these differences are just examples of a broader phenomenon. The amino acid profiles of plants are very different from the amino acid profiles of meat products. Unfortunately, many pet foods (both grain-free and grain-based ones) rely heavily on plant-based protein sources to meet AAFCO’s standards concerning daily protein intake. One need not be a rocket scientist to see why: plants are typically far cheaper ingredients than meats.

But that’s as true for grains as it is for tubers, legumes, fruits, or vegetables.

What this all suggests to me is that the touchstone of any examination of the links between diet and canine DCM ought not to be focused the presence or absence of grains. (Because grains are not a meaningful better source of taurine, methionine, or cysteine than are peas, potatoes, or any other starchy commodity crop.) It ought to be focused on the diet’s amino acid content, or perhaps on the degree to which the diet’s protein comes from animal sources (since that issue is in some ways a stand-in for the amino acid issue).

Unfortunately, that is not how the veterinary community has interpreted the FDA’s announcement. To a significant degree they’ve cast a much wider net, recommending that pet owners interpret the investigation as a reason to avoid all grain-free pet foods—casting a shadow over approximately half of all pet foods in the United States today.

There are at least five reasons why that’s such a problem.

1) Veterinary Professionals Shouldn’t Make Nutritional Recommendations Based Solely on Anecdotal Evidence

The FDA’s press release is not a warning about evidence of a link between diet and canine DCM. It’s an announcement that the FDA is going to try to determine whether such a link exists.

Please read that again.

The FDA is not warning consumers to stay away from certain foods due to proven links between those foods and canine DCM. Such warnings are a part of the FDA’s usual practice—so you can rest assured that if there was a good reason to recommend that pet owners avoid some foods due to concerns over DCM, the FDA would have simply said so. But that’s not what the organization has done in this case. In this case, the FDA is simply saying that anecdotal reports have motivated it to look at the issue more closely.

In our quest to understand the truth about complex, difficult-to-understand phenomena like the relationship between diet and health, anecdotal reports simply don’t cut it. It’s just too easy for nuance, bias, and our innate cognitive limitations to cloud our judgment. Indeed, that’s the very reason why the nutritional science community exists in the first place—to separate the valid evidence from the less reliable sources of information.

And, of course, this is precisely the standard to which responsible veterinary professionals—including Drs. Weeth and Freeman—typically hold themselves. To see this in action, consider just a few recent cases of anecdotal reporting on matters concerning the relationship between canine nutrition and chronic disease:

Oncologists at the KetoPet Sanctuary, a non-profit treatment center in Georgetown, Texas, claim to have had tremendous success using low-carbohydrate, ketogenic diets to treat canine cancer, arguably the single worst public health problem the pet world has ever seen. And the public seems to think they’re onto something, because the organization has received significant press coverage, massive interest from pet-owners, and abundant financial investment.

With Facebook interest groups boasting hundreds of thousands of members, a rapidly growing market presence, and dozens of blogs and books documenting revolutionary health outcomes, a not-so-small army of pet owners believes that raw diets can solve the pet world’s most vexing chronic disease problems.

Several dozen real, unpaid customers of my company, KetoNatural Pet Foods, have publicly stated that they believe our products have helped to cure or improve diabetes, obesity, cancer, or epilepsy in their dogs. And, as outlined below, these observations coincide with a massive groundswell of public interest in low-carbohydrate diets and fit neatly within a large body of evidence supporting the clinical efficacy of low-carbohydrate diets for treating several common chronic diseases.

But in every one of these cases, the veterinary nutrition community has reacted in precisely the same way: by ignoring or summarily dismissing the reports. And that’s exactly what responsible vets ought to do. There’s just too great a risk that these anecdotal reports won’t stand up to scientific scrutiny. What look like causal relationships right now might well turn out to be mere coincidences when subjected to rigorous testing.

But in the case of the FDA’s recent press release, many in the veterinary community have chosen to take precisely the opposite approach—immediately amplifying and doubling-down on a theory that has zero evidentiary basis at present.

2) Even if the Anecdotal Reports Prompting the FDA’s Investigation Are Totally Accurate, They Still Don’t Support the Recommendation That Pet Owners Should Avoid All Grain-Free Foods

In its press release, the FDA clearly highlighted that taurine deficiency is a well-understood cause of canine DCM. The organization also noted that it had observed several recent cases in which dogs with DCM had low blood taurine levels. (In four other cases, dogs with DCM had normal blood taurine levels—a fact which might suggest that what’s considered “normal” in this regard needs to be updated.)

This all makes perfect sense, given what the veterinary community already knows about how DCM works. If some dogs aren’t absorbing enough of the amino acids they need to supply their bodies with sufficient amounts of taurine, those dogs might very well be eating a diet that is causing them to develop DCM. That seems entirely plausible.

But that explanation does not justify avoiding all pet foods that don’t contain grains. Nor does it justify avoiding all foods that do contain peas, potatoes, or some other non-grain source of starch. A fairer and more accurate recommendation based on the FDA’s observations might have been to avoid foods without certain amino acid concentrations or to ensure that a certain amount of animal-based protein is included in the diet.

Think of it this way: try to name one nutritional quality—let alone a quality with a plausible-sounding etiological link to DCM—that common non-grain starch sources like peas, legumes, and potatoes all share but that all grains (corn, rice, wheat, etc.) do not share. Can you do it? I can’t.

Such a quality (and I don’t believe that there is one) necessarily must exist and must be causally linked to the etiology of canine DCM in order for the recommendations set forth by Dr. Weeth and Dr. Freeman to hold water. Otherwise, even if we take the FDA’s observations as gospel, they still don’t support the recommendation to avoid all grain-free foods.

And there’s something else to consider too. We should fully expect that many (if not most) DCM cases would be eating grain-free diets, even if there is no causal link whatsoever between grain-free diets and DCM.

That’s because, as we’ve already noted, grain-free foods make up about half of the pet food market. And surely the pet owners making reports to the FDA are even more likely to feed their dogs from a market segment that (fairly or not) has developed a reputation for “premium-ness.” Of course a lot of dogs with DCM are eating grain-free diets—grain-free diets are really, really popular.

The only way to determine whether DCM rates are significantly higher in specific diet groups than in others is to conduct the kind of statistical analysis that is common in peer-reviewed studies, but absent from anecdotal reports such as the one at the heart of this case.

To my knowledge, only one researcher has published data on this issue. Dr. Darcy Adin, a veterinary cardiologist at North Carolina State University, presented a research abstract at this year’s ACVIM Forum in which she summarized the canine DCM incidence rates she had observed at North Carolina State University over a three-year period. Of the 49 cases of DCM observed at the hospital between 2015 and 2017, 22 were being fed grain-free diets and 27 were being fed traditional, grain-based pet foods.

In other words, about 44% of the DCM cases were on grain-free diets. That sounds like a big percentage and, at first glance, suggests some kind of causal link. But remember that 44% of the dog foods sold in the United States today are grain-free! And if half the dogs in America are eating grain-free diets, we should fully expect about half of all DCM cases to be eating grain-free diets too—even if there is no link between DCM and grain-free diets whatsoever.

3) At Present, the Peer-Reviewed Experimental Evidence Linking Grain-Based Diets With Taurine Deficiency or Canine DCM Actually Outweighs the Evidence Linking Grain-Free Diets to Those Conditions

For a particularly glaring example of why the recommendations voiced by some members of the veterinary community in this case amount to such a gross misinterpretation of the evidence, consider that the peer-reviewed literature already includes numerous studies in which dogs fed grain-based diets developed taurine deficiency or DCM.

In one, twelve dogs with taurine deficiency and DCM were analyzed to determine if any common characteristics could be identified among them. And, in those cases, “all twelve dogs were being fed a commercial diet containing lamb meal, rice, or both as primary ingredients.” Rice, of course, is a grain commonly used as an ingredient in traditional-style pet foods.

In another, a group of nineteen Newfoundlands included twelve taurine-deficient dogs. And, in that case, every last one of the taurine-deficient dogs was being fed a “lamb meal and rice” diet.

Is the existence of these studies a solid reason to avoid all grain-based diets due to concerns over taurine deficiency and DCM? Of course not. Because the experiments were limited in scope and because, based on what the scientific community already knows about the matter, the inadequate amino acid content of the diets is the far more likely explanation for the outcome. There’s no understood pathophysiological process that might serve as a logical explanation for a direct link between the grains and taurine deficiency, so it wouldn’t be sensible to jump to the conclusion that the grains are to blame.

And did Dr. Freeman and Dr. Weeth write lengthy blog posts highlighting these studies as evidence that consumers should avoid all traditional, grain-based kibbles? Of course not. In those cases, the studies were interpreted narrowly and grain-based diets got the benefit of the doubt, just as we’d expect them to.

The only problem is that this prudent, sensible behavior is completely inconsistent with the nature of their recommendations in the present case. Here there isn’t even publishable evidence yet, let alone a clear etiological link between grain-free diets and taurine deficiency. But sweeping generalizations have been made nonetheless.

And yet, as double standards go, this one is not nearly as eye-popping as that which results when comparing the mainstream veterinary community’s reaction to the FDA’s recent investigation with its reaction to the large and growing body of evidence supporting a somewhat related nutritional issue.

4) The Body of Evidence Suggesting Dietary Carbohydrates are Detrimental to Canine Health Simply Dwarfs the Evidentiary Record Supporting the New FDA Guidance —But That Research Has Consistently Been Ignored by the FDA and Prominent Veterinarians

Outside of the veterinary community, a single nutritional science issue has loomed large over all others for at least the past five years: the degree to which dietary carbohydrates are playing an outsized role in fueling the epidemics of obesity, diabetes, cancer, arthritis, and many of the other chronic diseases that have vexed the public health community for decades.

A lengthy article discussing the medical community’s growing interest in ketogenic diets has been one of the most-read pieces in the JAMA network this year. Dozens (if not hundreds) of low-carbohydrate nutritional science books have been published over the past 15 years. Thousands of clinicians and research scientists have convened at conferences devoted entirely to discussing the latest in low-carbohydrate/ketogenic nutrition. (Unfortunately, the next one, at Ohio State University, is already sold out.) And, accordingly, public interest in ketogenic diets has grown explosively over the past five years.

This all makes perfect sense. Because the body of peer-reviewed research suggesting that carbohydrates are playing an outsized role in perpetuating many of the most common human health epidemics is vast and growing. Much of the evidence has been dutifully compiled by the folks at Virta Health—an organization that recently published the results of a new clinical trial in which ketogenic diets completely reversed type 2 diabetes in 60% of patients within one year—in this massive online catalog.

But inside the veterinary community it’s a different story. To my knowledge, I have written the only science book in history which endorses the theory that carbohydrates are damaging to the health of modern-day domestic dogs. With very few exceptions, there hasn’t been a peep about the matter from anyone else.

The far more common view when it comes to the links between carbohydrates and canine health is that carbohydrates are no less healthful (and perhaps even healthier) for dogs than other macronutrients. All else being equal, a carbohydrate-rich diet is so unlikely to cause adverse health outcomes in dogs that anything to the contrary doesn’t even warrant mentioning.

And not only do most mainstream veterinarians steadfastly refuse to break with this view, to date they have refused to even acknowledge alternative theories. In the human nutrition community, the healthfulness of carbohydrates is a hot button issue—academic conferences and online discussions alike are quick to descend into heated argumentation as soon as the topic of low-carb diets arises. But I have struggled for years to get even a single veterinary nutritionist to address the merits of the arguments I raised in my book. In my experience, they simply won’t touch the matter.

An attempt to distill these various arguments into narrative form would make this important piece unbearably long, so I’ll link to writing I’ve done elsewhere instead. In essence, there are at least four different reasons why I believe pet owners should consider minimizing the amount of carbohydrate in their dogs’ diets:

There is unimpeachable evidence that carbohydrates induce undesirable metabolic and hormonal changes in domestic dogs. Specifically, increasing carbohydrate intake has been shown to increase insulin secretion, up-regulate glucose metabolism, and down-regulate free fatty acid oxidation. (Translation: carbs make dogs burn sugar instead of stored body fat for energy.) Evidence reviewed here.

There is a coherent and compelling pathophysiological mechanism (the so-called “carbohydrate-insulin model of obesity”) and a strong and consistent body of experimental evidence suggesting that, calorie-for-calorie, carbohydrates are more fattening for dogs than other nutrients. Evidence reviewed here.

There is a coherent pathophysiological mechanism (based on the fact that cancer cells preferentially burn glucose for energy) and compelling experimental evidence from other animal models (although not from dogs) suggesting that low-carbohydrate ketogenic diets may help to prevent or slow the progression of some forms of cancer. Evidence reviewed here.

While the great majority of modern pet foods rely extensively on carbohydrates, there is unimpeachable evidence that the domestic dog’s genetic ancestors completely avoided dietary carbohydrates for at least 99.83% of their evolution as a canine species, making the widespread consumption of carbohydrates a plausible explanation for why “diseases of modernity” (obesity, cancer, diabetes, etc.) impact modern-day domestic dogs at far higher rates than wild canines. Evidence reviewed here.

These are the potential costs of canine carbohydrate consumption. And, as you can see, the strength of the evidence supporting each individual theory varies.

On the other hand, it is a matter of consensus in the scientific community that carbohydrates are not essential nutrients for dogs. Dogs require specific amounts of amino acids, fatty acids, vitamins, and minerals in order to function optimally and avoid diseases of deficiency. But—as we should fully expect in light of how recently canine species began consuming them—they do not require carbohydrates. None whatsoever.

That is to say, our knowledge of the costs of carbohydrate consumption remains imperfect. But, critically, there are no offsetting benefits associated with chronic carbohydrate intake. All else being equal, a dog has nothing to lose by abandoning carbs—and very likely a great deal to gain.

Although you’d never know it by looking at the veterinary nutritional dogma.

For instance, consider how the country’s leading veterinary organizations—and both Dr. Weeth and Dr. Freeman individually—have told dog owners to approach the decision of whether to feed pets commercial raw-ingredient diets.

Despite their growing popularity, such products have been demonized time and time again by veterinary authorities. Their warnings typically take the form of cost-benefit analyses. The supposed costs primarily stem from the fact that raw meat can become infected with microscopic pathogens, such as Salmonella bacteria. It’s unlikely (but possible) that one will cause a dog to develop any clinical symptoms (after all, its genetic ancestors ate literally nothing but raw meat until at least the final 0.17% of their evolution as canine species.) But they can make people sick. So, the thinking goes, commercial raw diets carry a significant cost.

Technically, this is a legitimate concern supported by actual evidence. No doubt about it. It’s just not nearly as significant a concern as it has been made out to be. While it is possible for Salmonella to make dogs sick, there is only scant evidence of it actually doing so. And while the risk of transmission to humans is real, it is curtailed by common-sense safety practices, such as hand-washing and avoiding direct contact with feces. Moreover, most commercial producers employ elaborate safety measures to reduce contamination. In the end, here’s how the authors of one comprehensive meta-analysis recently described the relevant evidence:

“[T]here have been no studies conclusively documenting the risk to either pets or owners.”

In the context of the typical cost-benefit analysis, however, even a remote threat justifies the avoidance of commercial raw diets. That’s because veterinary authorities insist that these products carry absolutely no benefits.

And, again, technically, it is fair and accurate to say that raw diets are not inherently beneficial for canine health. I’ve carefully evaluated the evidence myself, and I fully agree that there is no meaningful evidence that the defining characteristic of raw diets (their “raw-ness”) is healthful in any way.

But that’s a disingenuous way to look at the issue. Because there’s another quality that sets the great majority of commercial raw diets apart from traditional kibbles, and this one is consistently ignored by veterinary authorities: they contain very few carbohydrates. While most kibble-style pet foods contain at least 40% carbohydrate (and very often much more than that!), raw diets typically contain few, if any carbs. And, as I’ve already explained, the evidence linking carbohydrate consumption with negative health outcomes in dogs is voluminous. Moreover, unlike the risks of raw meat contamination (or canine DCM, for that matter), that evidence doesn’t concern rare and uncommon issues. It relates directly to the most significant and deadly public health epidemics that the pet world has ever experienced.

In all the writing that Dr. Weeth, Dr. Freeman, the AVMA, the American Animal Hospital Association, the American College of Veterinary Nutrition, and even the FDA have done about the costs and benefits of raw diets, I’m not aware of a single instance in which any one of them has considered the significance of dietary carbohydrates. And, given the current state of the evidence linking carbohydrates and disease, that‘s a very difficult fact to explain.

Or is it?

5.) Casting Aspersions on All Grain-Free Products (Without Distinguishing Based on Protein or Amino Acid Content) Is Likely to Drive Consumers Away From Lower-Carbohydrate, Higher-Meat Pet Foods

It’s hard to ignore that the mainstream veterinary community’s perspective on the healthfulness of raw diets looks an awful lot like its reaction to the FDA’s investigation of grain-free ones. In both cases, all analyses of the underlying costs and benefits are woefully incomplete because they completely ignore the evidence suggesting carbohydrates are unhealthy for dogs. And leaving carbs out of the equation completely guts the analysis.

Unlike commercial raw diets, where the great majority of products contain few (if any) carbohydrates, it is not the case that all grain-free dry dog foods are low-carb. Extruded, kibble-style pet foods can be made using starches other than cereal grains (such as processed potatoes). Moreover, starch-stuffed plants are far cheaper ingredients than animal products and the existing regulatory regime makes it incredibly easy for producers to hide the sizable carbohydrate contents of their products. As a result of all this, many grain-free kibbles are still packed with carbs. (As of August 2017, the twelve most popular grain-free dry dog foods on Chewy.com contained an average of more than 32% carbohydrate on an as-fed basis.)

That said, it most certainly is the case that truly low-carbohydrate pet foods are almost always grain-free. And, as the founder and president of a company that produces kibble-style dog food products with less than 5% carbohydrate (on an as-fed basis), I can testify as to exactly why that is the case.

In short, fairly or not, “grain-free” means “low-carb” to millions of pet owners. And because it is so difficult under existing regulations to communicate directly with consumers on the issue of carbohydrate content, producers have little choice but to make their formulas grain-free if they want as many consumers as possible to understand that their products contain more meat and less carbohydrate than leading brands.

This is why the veterinary community’s reaction to the FDA’s investigation is not just wrong, it’s harmful too. Because demonizing all grain-free foods equally (regardless of protein or amino acid content) unfairly groups high-meat, amino acid-rich options with grain-free products that include little or no animal meat whatsoever.

And, again, I’ve experienced this first-hand. In the wake of the articles written by Dr. Weeth and Dr. Freeman, my company, KetoNatural Pet Foods, received a massive surge of e-mails from customers worried that our grain-free products would give their dogs DCM. But our products contain more than 46% protein (the great majority of which comes from animal sources), more than twice AAFCO’s recommended daily allowance of cysteine and methionine, and more than 500 milligrams of taurine per kilogram of food. There are few, if any, dry dog foods that contain more animal-based protein than ours do. Based on the existing evidence, our products are about as unlikely as any to cause a dog to develop DCM.

Nevertheless, the veterinary community’s reaction to the FDA’s investigation caused a panic amongst our customers. We were seriously damaged by the unfair generalizations.

And if the idea of for-profit corporations complaining about unfairness doesn’t exactly arouse your sympathies, consider that the problem goes a good deal further than that too. Because, in my view, the zone of damage resulting from this scandal is likely to include everyday pets as well. Because, just like with commercial raw diets, anything that serves to drive pet owners away from grain-free products is going to necessarily increase the amount of carbohydrate that modern dogs consume. And, as I explained above, there are several different solid, evidence-based reasons to believe that carbohydrates may well be playing an outsized role in perpetuating the most devastating chronic disease epidemics in the history of the domestic dog.

It is shocking that America’s leading veterinary authorities would encourage this outcome without even acknowledging the sizable body of evidence suggesting that it could be harmful to the very population they have sworn to protect. Why on Earth would they ignore such a sizable body of evidence? It’s hard to understand.

But that’s not to say we shouldn’t try to understand it.

Stay tuned. In Part Two of this series I will try to explain the unexplainable by examining the marketing tactics of a few of the pet food industry’s richest companies. I’ll be drawing on the research I conducted in connection with writing Dogs, Dog Food, and Dogma, as well as some new investigative work. There’s a pretty shocking story here, so I hope you’ll come back and check it out. I expect it to be ready for the world in about a month.

As always, thanks for reading. Keep your eyes peeled for Part Two.

—

I disagree with both Dr. Weeth and Dr. Freeman in my perspective on why “grain-free” has so successfully become a defined market segment. It seems to me that consumers, exercising judgment that is supported by common sense, a basic grasp of evolution via natural selection, and the peer-reviewed experimental record, want pet foods that are rich in meat and low in carbohydrate content. After all, that’s precisely what the domestic dog’s genetic ancestors ate for more than 99.8% of their evolutionary heritage. Unfortunately, unlike their human-food counterparts, current U.S. pet food regulations do not require manufacturers to affirmatively disclose the carbohydrate content of their products. To a significant degree the regulations don’t even allow such disclosures. But “grain-free” feels a lot like “low-carb,” particularly when it’s paired-up with the image of a wolf. So many consumers seeking “low-carbohydrate” products wind up choosing “grain-free” ones instead.

Dr. Freeman has written that wild wolves eat “berries, plants, etc.,” in addition to raw meat. This statement is contradicted by all empirical evidence. And it was described to me as “laughable” by more than one of the biologists at the Yellowstone Wolf Project with whom I lived while researching my book. It simply isn’t true.

January 4, 2018

Is My Dog Too Fat?

A major recent study suggests that being just moderately overweight is deadlier for a dog than a lifetime of smoking is for a human being. Being just “a little fat” is simply horrible for a dog’s health. It is literally worse than smoking.

And being “very fat”? Well, it’s likely even worse than that.

That’s bad news for American dogs, because polling suggests that more than 50% of them are overweight or obese (but that only 10% of their owners are aware of it). This means if you pick a random dog on the street, it is more likely than not to be overweight.

It also means that, statistically-speaking, your dog is probably overweight.

But let’s ignore the statistical version of your dog for a minute and focus instead on the real version. Is she actually “too fat” or not? And how do you know for sure?

In my experience, this subject is fraught with misinformation. There are scores of well-intentioned folks out there who think they know what they’re talking about when they make judgments about the matter, but they usually don’t have a working knowledge of the relevant evidence. So they’re in no position to defend the validity of their own recommendations.

Fortunately for you, I’m here to help separate the wheat from the chaff. In this article, I’ve essentially summarized a particularly lengthy chapter from my book, one in which I review the existing evidence on canine body condition and explain the best way to determine whether or not a dog truly is “too fat” or not.

I hope you find it helpful.

What’s My Dog’s Ideal Weight?

Here’s the simple but surprising answer: no one (I repeat: no one) knows.

Why? Because, at this moment, there is precisely zero published scientific evidence on what constitutes an “ideal body weight” for any specific dog.

Seems impossible, right? After all, veterinarians, breeders, breed organizations, and self-appointed “experts” the world over never tire of telling us how much individual breeds ought to weigh. Surely some of their recommendations are based on valid evidence, right?

Nope.

While AKC-recognized breed standards typically contain “ideal body weight” ranges, those ranges are based solely on the subjective judgments of the group’s leadership. And while those individuals tend to have plenty of experience being around specific kinds of dogs, there’s not a single case in history in which one has publicly defended his recommendations based on any kind of peer-reviewed health or longevity data.

And there are other reasons to be leery of “ideal body weight” recommendations too.

For one, breed standards don’t even claim to be about optimizing health and longevity in the first instance. Instead, they’re typically about defining the qualities that tend to “protect and advance the interests of the breed,” whatever that might mean.

Moreover, plenty of breed standards have been loudly criticized for promoting decidedly unhealthy physical traits. (See this New York Times Magazine article for a nice example.) In fact, there’s even published evidence suggesting that winning show dogs (ostensibly those that comply best with the body weight recommendations embodied in breed standards) tend to be a good deal fatter than they really ought to be, at least according to veterinarians.

(And, of course, plenty of dogs also don’t fall neatly into one breed or another. So millions of them don’t even have the benefit of breed standards to go by.)

But, most importantly of all, body weight just isn’t all that good a predictor of body fatness. There are plenty of weighty tissues in a dog’s body that have nothing whatsoever to do with fat. And there are plenty of lean, muscular dogs that are a good deal heavier than the weight ranges set forth in their breed standards suggest they ought to be.

So if body weight recommendations aren’t a reliable way to determine whether your dog is too fat, is there something better you can use?

Yes, there is.

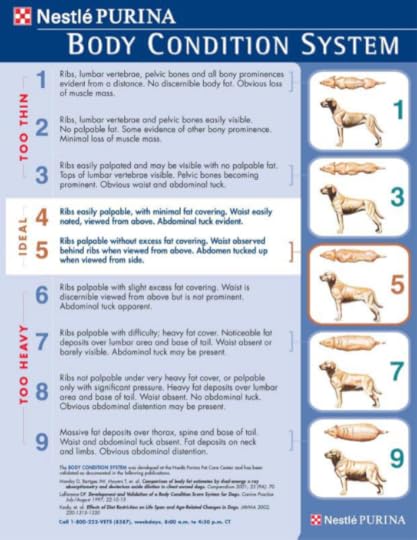

Body Condition Scoring Charts

Body condition scoring charts began coming into public view in the 1990s. Today they are the standard method by which veterinarians analyze canine body condition.

They sound a little complicated, but they’re actually quite simple. Essentially, they task the user with completing a targeted visual and tactile body part analysis in order to make some inferences about the overall nature of a dog’s body condition. In other words, all you have to do is look at and feel a few key parts of your dog’s body and you can reliably infer how much fat is in there.

Here’s the first and best-known version:

This particular system was created by a veterinary nutritionist working for Nestle Purina, but experiments definitively validating its usefulness and accuracy have been published in academic journals. It is beyond legitimate dispute that this system typically allows both experts and laypeople to make consistent, accurate judgments about the amount of fat in a dog’s body.

There are other examples (here’s my own crack at it), including at least one other that has also been validated through peer-reviewed scientific experimentation. But, generally-speaking, they all recommend the same thing: dogs’ bodies should be reasonably but not very lean, featuring (1) an “hourglass figure” (with shoulders and haunches that are somewhat wider than the waist), (2) an “abdominal tuck” when viewed from the side; and (3) ribs and skeletal musculature that are palpable.

Go ahead and give one a shot with your own dog. You’ll see that it’s very straightforward and takes no longer than about 60 seconds to complete. All good, right?

Not so fast. There’s a problem. And it’s an important one.

The problem is that the qualitative body condition recommendations (“ideal,” “too heavy,” “too thin,” etc.) made in even the most widely-used BCS protocols also are not based on any evidence. Do they seem reasonable at first glance? Sure. But a closer inspection of the research underlying them reveals that their authors (credentialed and well-intentioned as they might be) made no effort to cite evidence supporting their interpretation of what constitutes “too fat” when it comes to a dog.

I know this because I’ve read the studies (one was published in a tiny journal that isn’t available online, the other is linked above). I also interviewed the lead researchers on each one, just to give them all the benefit of the doubt.

Unfortunately, this research just confirmed the truth – the categories set forth in these BCS protocols were not based on a single, solitary evidentiary source. They amount to guesses made by their authors as to what is truly optimal when it comes to canine body condition, not any actual data linking body fatness to health or longevity.

What this means is we need to take one final step in order to understand what it means for a dog to really be “too fat.” We need to review the relevant evidence for ourselves.

What Does the Evidence Really Say About “Optimal” Canine Body Condition?

I’m going to do my very best to keep this short and sweet. (If you want the longer version, you can download a free copy of my book here.)

Most of the research into the links between fatness and health has been conducted on human subjects, where funding is far easier to come by than in the world of small animals. That body of research definitively shows that a U-shaped pattern governs the relationship between human Body Mass Index (a ratio reflecting the relationship of weight to height) and longevity.

For maximizing lifespan, the optimal BMI is almost always shown to be between 18.5 and 25.0. And it is undisputable that folks with a BMI either above or below the point of optimization tend to live shorter lives, at least on average.

But this is a curious pattern. Because the relationship between body condition and deadly chronic disease occurrence is not U-shaped. One’s risk of developing chronic diseases (including, at least, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, about a half-dozen cancers, Alzheimer’s disease, gallbladder disease, hypertension, and osteoarthritis) simply rises as one gets fatter. The fatter you are, the higher your risk. The leaner you are, the lower your risk. Period.

This latter pattern is exactly what we should expect to see, given what the scientific community knows about how body fat works. Over the past 25 years, researchers have discovered that fat tissue actively secretes substances called adipokines. And it’s those substances that cause chronic inflammation, and therefore disease. More fat tissue = more adipokines = more inflammation = more disease.

So why the U-shaped relationship between BMI and longevity? The answer seems to be that BMI isn’t a great predictor of body fat, at least not at the individual level. Some folks with low BMIs are scrawny (i.e., they have low levels of lean body mass), but not particularly lean (i.e., low levels of body fat). And scrawniness, it seems, is something that directly reduces one’s ability to combat deadly diseases (while leanness is not).

Here’s how a few different research teams recently described the phenomenon in recent papers:

“The apparent U-shaped association between BMI and total mortality may be the result of compound risk functions from body fat and fat free mass.” (Paper here.)

“Our findings suggest that BMI represents joint but opposite associations of body fat and FFM [fat free mass] with mortality. Both high body fat and low FFM are independent predictors of all-cause mortality.” (Paper here.)

“These results support the hypothesis that the apparently deleterious effects of marked thinness may be due to low FFM and that, over the observed range of the data, marked leanness (as opposed to thinness) has beneficial effects.” (Paper here.)

The limited body of canine research is perfectly in-line with these studies of human subjects. We know that canine fat tissue produces inflammatory adipokines, just like human fat tissue does. (See here.) We know that dogs with an average body condition of BCS 4.6 will typically live several years longer than dogs with an average BCS of 6.7. (See here.) We know that markedly obese dogs tend to have higher chronic disease risks than somewhat leaner dogs. (See here, here, here, here, here, and here.) And we know that, in the few instances where a wide range of canine body conditions have been analyzed (as opposed to experiments where a group of fat dogs was simply compared with a group of somewhat less-fat dogs), the leanest dogs in the study typically have the lowest chronic disease risk. (See here and here.)

So what does this all mean for our BCS protocols?

It means the evidence suggests that in some respects they’re likely to be giving bad advice. They are eminently useful when it comes to determining how fat a dog is, but they aren’t giving sound, evidence-based advice when it comes to determining how fat a dog ought to be.

If the BCS protocols truly reflected the realities of the data, they would simply say that leaner dogs are healthier dogs, full stop. That, so long as muscle mass remains normal, there’s no such thing as a dog that’s “too lean.”

And, in a way, that’s good news for you. Because it means there’s a very simple answer to the question “is my dog too fat?”

The answer to that question is simply yes.

According to the best available evidence, so long as your dog is maintaining normal amounts of muscle tissue (and is not already in the clutches of a deadly chronic disease), the leaner she is, the healthier she is likely to be. Period.

December 23, 2017

Diabetes, Dog Food, and Carbohydrates: What You Need to Know to Make the Best Decision For Your Best Friend

Canine diabetes mellitus is one of the most common and serious endocrine disorders diagnosed in pet dogs. It’s often debilitating, sometimes deadly, and almost always expensive to treat. Studies suggest that it’s getting more common too.

In lay terms, the disease is characterized by having too much sugar (glucose) in the bloodstream and not enough in the other tissues that need it. But, in a way, the disease is less about glucose and more about the body’s production and use of the hormone insulin.

Insulin’s primary function is to drive circulating glucose into tissues like fat and muscle. In diabetic animals that process becomes dysfunctional, so more and more glucose stays in the blood instead. If left untreated, the resulting condition (hyperglycemia) can cause debilitating damage to the eyes, kidneys, and cardiovascular system.

There are a few different ways that glycemic control can become disrupted. In what’s typically called insulin-deficiency diabetes (IDD), the pancreas simply stop producing enough insulin. In insulin-resistant diabetes (IRD), insulin production remains normal (or is elevated), but peripheral tissues become desensitized to the hormone, so they no longer suck up glucose effectively. In IDD, there’s not enough insulin being produced; in IRD, the insulin no longer does its job effectively. In both cases, persistent hyperglycemia is likely to result without treatment.

Although treatment varies on a case by case basis, it typically involves (1) supplementation with exogenous insulin and (2) nutritional management. And while there are several factors that are relevant to determining the appropriate diet for a dog with diabetes, one is by far the most important—carbohydrate content.

The reason for this is simple: dietary carbohydrates are glucose. Some begin the digestive process as more complicated molecules (what are often called complex carbohydrates), but by the time they enter the bloodstream, they’ve all been broken-down into glucose molecules. That’s why dietary carbohydrates cause blood sugar levels to rise so dramatically, while fats and proteins do not.

Nothing about this is remotely controversial. Every major veterinary nutrition textbook in circulation today highlights the unique importance of glycemic control to the nutritional management of canine diabetes. It is universally regarded as the most important dietary factor to be considered by caregivers.

What is controversial are the specific dietary strategies typically recommended for controlling glycemic response. None of the leading textbooks recommend a low- or zero-carbohydrate diet to help dogs manage their diabetes. Instead, they recommend strategies that are merely likely to slow (but not reduce) the delivery of glucose into the bloodstream: feed complex carbohydrates instead of simple ones, feed some fiber along with the carbohydrates, avoid “semi-moist” foods, etc.

Why not just tackle the problem directly and recommend carbohydrate restriction (or outright elimination) instead? After all, premium dry dog foods with less than 5% starch are now being produced. And veterinarians treating diabetes with zero-carbohydrate diets are having remarkable results. And, of course, dogs are more than capable of producing all the glucose their bodies need without any dietary carbs whatsoever. (That’s why carbohydrates aren’t considered essential nutrients for dogs, while proteins and fats are.)

I can only speculate about the answer to this question. That said, the answer does seem rather obvious to me when you consider these two facts:

(1) The two leading veterinary nutrition textbooks in circulation today were written by paid employees of Hill’s Pet Nutrition and Proctor & Gamble Petcare, respectively.

(2) The diabetes formulas sold by those leading pet food manufacturers rely heavily on cheap, fattening, blood-sugar spiking dietary carbohydrates. For instance, more than half of the calories in Hill’s Prescription Diet W/D Canine formula come from carbohydrates! (Glycobalance Dry Dog Food — the diabetes formula produced by former P&G brand Royal Canin — is only slightly better.) I’m sorry, that’s simply scandalous.

If you’re of the crazy belief that a diet with less than 5% starch might just be a better choice for your diabetic dog’s glycemic control than one with more than 50% carbohydrate, then you should probably check out a premium dry dog food like Ketona. And if you want to read more about how to reduce your dog’s carbohydrate intake, please re-visit our Ultimate Guide to Choosing a Low-Cost, Low-Carb Dog Food.

Thanks for reading. If you have any questions or comments, please raise them below and I’ll do my best to get back to you as quickly as possible.

December 17, 2017

Grain-Free Pet Foods: Healthy or Hoax?

As any dog owner can attest, the modern pet food market is practically bubbling over with choice.

At least that’s the way it seems. Producers certainly do a wonderful job of making it feel like they’re offering consumers an abundance of choices, with “Limited Ingredient Diets,” “High Protein Diets,” and, of course, “Grain-Free Diets” being just a few of the more popular varietals on offer.

In recent years, the term “grain-free” has enjoyed a particularly good run. Industry analyses suggest that it already is one of the most popular segments of the pet food market and that its popularity is continuing to grow. It seems clear that the term “grain-free” has become, in many circles, an indicator of premium quality and healthfulness.

But what does it actually mean for a pet food to be “grain-free”? Are there any real, demonstrable health benefits to these products? And, if so, which brands do the best job of providing those benefits?

I’ll save the time-pressed among you some suspense. The short answers are “less than you think,” “not necessarily,” and “Ketona, and to a lesser extent a few of the others listed below.”

Now, for those looking to understand the conceptual framework behind these answers (or extend lunch hour by a few minutes), a bit of elaboration.

What Does “Grain-Free” Really Mean?

The Association of American Feed Control Officials is the body that, for all intents and purposes, regulates the majority of what can and cannot be printed on a pet food label. And AAFCO considers the following ingredients to be “grain products”: barley, corn, grain sorghum, oats, wheat, rice, and rye. So, naturally, any “grain-free” pet food cannot contain any of those ingredients.

Now, if you know a bit about how pet food is manufactured, you might think this list would pose a problem or two for manufacturers intent on making “grain-free” dry kibble products. For one, these commodity crops are all among the cheapest sources of calories known to man—and that’s not exactly good news for a profit-minded manufacturer.

Even worse, they all contain an abundance of the carbohydrate molecule starch. And starch plays a critically-important functional role in the kibble-production process. In essence, starch gets sticky when it gets very hot, so it serves to bind the rest of the ingredients together as they bake, just like flour does when you bake cookies. Take away the starch, and your cookies (or kibbles) are likely to simply fall apart.

Fortunately for “grain-free” pet food manufacturers, there’s a way around these problems. They can just use potatoes, sweet potatoes, or some other combination of tuber ingredients instead of grains. Tubers are bulbous plant structures that grow underground. And, just like grains, many of them are both (1) wildly inexpensive and (2) crammed with starch. For those reasons, they represent the perfect workaround for a pet food manufacturer intent on producing a “grain-free” kibble product without breaking the bank.

So, in the vast majority of cases, the defining attribute of a “grain-free” dry pet food product is simply that it uses tuber ingredients like potatoes or yams as a source of starch instead of grain ingredients like rice, corn, and the rest.

Are “Grain-Free” Foods Actually Healthier For Pets?

To answer this second question, it is important to also appreciate what it doesn’t mean for a pet food to be “grain-free.” More specifically, it is vital to understand that whether or not a product is “grain-free” is all about its ingredients; it is not at all about its nutritional content.

The difference between ingredients and nutrients is a hugely significant one when it comes to understanding the healthfulness of a pet food. And it’s the improper blurring of the line between the two terms that, I believe, is largely responsible for the popularity of “grain-free” pet foods in the modern market.

Nutrients are the aspects of food ingredients that organisms actually use to survive and grow. Broadly speaking, they include macronutrients (proteins, carbohydrates, and fats), which provide metabolic energy and the bulk raw materials needed for tissue growth and maintenance, and micronutrients (vitamins and minerals), which are required in trace quantities in order to help propel those bodily processes along.

Ingredients are food products that are composed of nutrients. And this means that two very different ingredients can actually have quite similar nutritional contents. In fact, we’ve already seen a prime example of this—from a producer’s perspective, tubers and grains both make useful dry pet food ingredients because they both contain a great deal of the carbohdyrate molecule starch.

In other words, the real question we ought to be asking when thinking about the healthfulness of a pet food is not what are its ingredients (i.e., is it “grain-free” or not?) but what is its nutritional content?

Most consumers are well aware of this. And if the mainstream media and Google’s historical data on search trends are anything to go by, they’re particularly interetsed in one specific nutritional issue: restricting carbohydrates.

This article is not meant to be a deep dive into the scientific evidence suggesting that carbohydrates are unhealthy for dogs. I’ve already done that analysis elsewhere. So here’s just a quick run-down of what my KetoNatural colleagues and I think about the evidence (with links to our more thorough analyses):

There’s undeniable evidence that dogs avoided carbs completely for more than 99.9% of their genetic evolution. There’s undeniable evidence that carbohydrate consumption causes profound metabolic and hormonal changes within a dog’s body. There’s very strong evidence that carbohydrates are more fattening for dogs and cats than other nutrients. And there’s a limited (but growing) body of evidence suggesting that carbs are playing a significant role in the development of some common and deadly chronic diseases.

On the other hand, I’m not aware of any evidence supporting a theory that grains are more harmful to dogs and cats than any other starch-rich ingredients. For instance, experiments have been performed confirming that the glycemic impact of grains is roughly the same as the glycemic impact of other starchy ingredients (i.e., they both cause massive blood sugar and insulin spikes) in dogs.

For all these reasons, it seems crystal clear to me that what consumers really care about is the carbohydrate content of pet food products, not whether those carbohydrates come from grains or from potatoes. So let’s close the loop on our analysis of “grain-free” dry dog foods by looking at the subject of carbohydrate content more directly.

Which “Grain-Free” Dry Pet Foods Are Lowest in Carbohydrate Content?

Here’s something that might surprise you: unlike their “people food” counterparts, pet food manufacturers are not required to tell consumers how much carbohydrate is in their products. In fact, until very recently, they were affirmatively prohibited from even mentioning carbs at all in the Guaranteed Analysis panel (AAFCO’s equivalent of the FDA’s Nutrition Facts panel). Only recently, after many years of lobbying by consumers, did AAFCO finally begin allowing producers to mention starch and sugar content in the Guaranteed Analysis panel (outrageously, total carbohydrate content still isn’t allowed).

Naturally, most pet food producers choose not to make these voluntary disclosures. Instead, they make every effort—prominent images of wolves, emphasis on meat and protein content, products framed as “grain-free,” etc.—to suggest that their products are low in total carbohydrate content. They know consumers aren’t looking to stuff their pets with carbs. So, without addressing the issue directly, they make every conceivable effort to suggest that their “grain-free” products contain only a limited amount of carbohydrate.

Unfortunately for consumers, the reality is usually quite the opposite.

I know this because I’ve gone through the work of figuring out the carbohydrate content of the twelve most popular “grain-free” dry pet foods on the market today. In each case, I’ve either asked the manufacturer directly, tested the product using laboratory analysis, or calculated the total using the process outlined in this earlier article I wrote.

Before I get to the results, I’d be remiss if I didn’t include information about Ketona Chicken Recipe For Adult Dogs (full disclosure: I was closely involved in founding the company that produces it). It’s a new “grain-free” dry dog food, and while it’s not yet a leading brand it does contain less than 8% carbohydrate (on as-fed basis). Which, as you’ll see, basically puts it in a category of its own.

Now, here’s how the twelve most popular “grain-free” dry pet foods on the market today stack-up against one another:

Product

% Carbohydrate (As-Fed Basis)

Taste of the Wild High Prairie Grain-Free Dry Dog Food

26.5

Taste of the Wild Pacific Stream Grain-Free Dry Dog Food

38.7

Blue Buffalo Wilderness Chicken Recipe Grain-Free Dry Dog Food

32.5

Natural Balance L.I.D. Limited Ingredient Diets Sweet Potato & Venison Formula Grain-Free Dry Dog Food

46

Blue Buffalo Wilderness Salmon Recipe Grain-Free Dry Dog Food

32.5

American Journey Salmon & Sweet Potato Recipe Grain-Free Dry Dog Food

26

Taste of the Wild Sierra Mountain Grain-Free Dry Dog Food

40.2

Natural Balance L.I.D. Limited Ingredient Diets Sweet Potato & Fish Formula Grain-Free Dry Dog Food

45.92

American Journey Chicken & Sweet Potato Recipe Grain-Free Dry Dog Food

23

Merrick Grain-Free Real Texas Beef and Sweet Potato Recipe Dry Dog Food

20.13

Orijen Original Grain-Free Dry Dog Food

20

Blue Buffalo Basics Limited Ingredient Grain-Free Formula Turkey & Potato Recipe Adult Dry Dog Food

48

As you can see, all of the leading “grain-free” dry pet foods on the market today contain at least 20% carbohydrate. And several contain nearly 50%.

This means that Ketona, at less than 8% carbohydrate, is in a whole different realm than its leading competitors. They all contain at least twice as many carbs as it does. And some contain five or six times as many!

It also means that several of the most popular “grain-free” products on the market today actually contain more carbohydrate than a leading grain-based product like Purina Pro Plan Savor Adult Shredded Blend Chicken and Rice Formula. Which ought to hammer home just how misleading the whole “grain-free” label can be in the first place.

—

That’s it for today. Thanks for reading. I hope you found this article helpful and informative. Please drop me a line in the comments if you’d like to add anything or if you have any questions.

November 23, 2016

The Skeptic’s Guide to the Benefits of Raw Dog Foods

What follows is my skeptical analysis of the arguments commonly made for why raw-ingredient diets are “better” for dogs than those based primarily upon cooked products. It’s a lengthy (3,000+ words) and in-depth piece. Perfect for passing the time while waiting for a delayed flight or taking a break from an awkward Thanksgiving table debate about the recent election.

I have been asked to analyze this issue countless times. The raw dog food industry is growing explosively, in spite of the undeniable costs associated with its products. Calorie-for-calorie, commercially-prepared raw dog foods are usually at least eight times as expensive as traditional kibbles. Moreover, they involve considerably more preparatory work than “scoop-and-serve” kibbles and they carry at least some risk of contamination with dangerous food-borne pathogens too.

Given these costs, consumers clearly must believe that raw food products have some pretty serious benefits. And a few minutes of Internet sleuthing will demonstrate that many folks believe precisely that. To my eye, proponents of raw food diets are often zealous (even militant) in their online advocacy, with all manner of popular blogs and Facebook groups touting the supposed benefits of “going raw.”

Today’s post is my attempt to analyze their arguments in light of the best available evidence. Are the raw food devotees onto something? Do their arguments really hold water, or do they suffer from unfounded assumptions, a lack of evidence, or some other kind of shaky logic? What do we really know about the benefits or raw dog foods?

Now, let’s get something out of the way right here at the start. As I never tire of writing, there is at least one way in which raw diets are indisputably more healthful for dogs than the kibble-ized alternatives: they’re usually much lower in total carbohydrate content. Kibbles tend to be composed of 40%-60% (or more!) carbohydrate. Raw foods usually contain no carbohydrates whatsoever. For the most part, they’re meat and meat alone.

Why does that count as a benefit for raw foods? Well, calorie-for-calorie, carbs make dogs fatter than other nutrients. And being fat kills dogs. So there can be little debate over whether the lower carbohydrate content of raw-ingredient foods renders them a more healthful choice than kibbles for that reason alone. There is also emerging (if not yet overwhelming) evidence that zero-carbohydrate diets can slow or prevent the spread of cancer. Seeing as obesity and cancer are, without question, the two most pressing chronic health problems in America’s pet population, it makes plenty of sense to go raw for the simple purpose of reducing carbohydrate intake.

But in this piece we’ll be looking at something slightly different. We’ll be examining the evidence supporting the claim that raw ingredients are more healthful than cooked ingredients simply by virtue of being consumed in a raw state. In other words, if we could take all the ingredients in a raw-ingredient food, bake those ingredients and produce a lower-cost kibble, would there still be health-related reasons to choose the raw food product?

Other than the nutritional benefits of carbohydrate minimization, I have heard a grand total of four different arguments advanced in favor of raw-ingredient diets: (1) the “Enzyme Argument,” (2) the “Micronutrient Bioavailability Argument,” (3) the “Overall Vitality Argument,” and (4) the “Don’t Mess With Mother Nature Argument.” I’ll examine the merits of each one below.

But before we wade into those substantive arguments, there’s something we need to consider first, which is the fact that the American College of Veterinary Nutrition already claims to have done this analysis for us. And here’s what the ACVN has to say about the state of the evidence (emphasis mine):

Advocates of raw diets claim benefits ranging from improved longevity to superior oral or general health and even disease resolution (especially gastrointestinal disease). Often the benefits of providing natural enzymes and other substances that may be altered or destroyed by cooking are also cited. However, proof for these purported benefits is currently restricted to testimonials, and no published peer-reviewed studies exist to support claims made by raw diet advocates.

Yikes. Pretty unequivocal, huh?

Now, there are some good reasons to believe that the ACVN knows what it is talking about here. Like the fact that, as the governing body that oversees the board-certification of specialists in veterinary nutrition, it is probably the most reputable source of veterinary nutrition advice on the planet.

Nevertheless, I think that it’s worthwhile to do our own analysis of the evidence. Because I believe that the dismissive, across-the-board nature of the ACVN’s position statement is a clear case of overstatement. And it’s not too hard for me to prove my point.