Steven C. Nelson's Blog

April 4, 2017

Lighten Your Load

photo: gratisography.com

photo: gratisography.comSome people are constantly in a state of crisis management. No matter what they do, they just can’t seem to get out from under the crushing weight of their own poor decisions—sometimes decisions made to get out of existing messes! They are stressed to the max, always anticipating the ramifications of yet another thing gone wrong. You can’t help but feel bad for them as they exhibit a stout inability to control or even influence the world around them. Others’ lives are just as complication-laden, but they’re oblivious, which sometimes creates the crises around them because they don’t give the proper attention to minor issues prior to their becoming urgent. But that being unaware (which I am jealous of) also preserves their mind, as it shelters them from fully comprehending the gravity of the situation and going into full-on freak out mode.

I had a friend in college that typified the latter group. He really struggled our freshman year to get his S together, and it was so sad and frustrating to watch. The first few weeks were particularly rough for him as he adjusted to this big, new world of schedules and finals and lack of parental oversight. Tardy was his modus operandi, and I was convinced it would be his undoing. We were lucky enough to have a class together that first year, or, he was lucky we did, anyway. On multiple occasions, I joined in and embellished his stories, as if I had been there too, as he tried to explain to our professor what it was that prevented his arriving on time. He passed, and I like to think that was due in part to me embracing my inner thespian.

I helped him out because I knew he wasn’t trying to get something for nothing or shirk his responsibilities, he just needed guidance; he operated on a plane of reality different from the rest of us. What is important to you and me, e.g., responding to texts, showing up if you said you would—time in general—were to him minor details that were overlooked if something of greater interest presented itself. It was infuriating never being able to count on him, but his vagaries, the waiting to see what exactly would happen, were what made the friendship entertaining, like jamming a handful of Mentos into a two-liter of soda.

I’m somewhere between wandering around with my head in the clouds and being mired in tumult; I like to think that puts me somewhere in the range of normal. I like to walk through scenarios before jumping into them, because I’m aware that poor planning can lead to undesirable ramifications (waking up half dressed in a house you didn’t start the party in is a good example…a hypothetical one, of course). I have to keep in mind, though, that I can start missing major details if I get hyper focused on one tree and disregard the rest of the forest. So, a balanced emotional and mental investment in an issue is optimal.

That’s what Calm Me says; Freak Out Me is way less rational. My Achilles heel is managing my stress when something unexpected pops up. I’m terrible at it; I go from Gandhi to a whirlwind of terror, doubt, and worst-case scenarios faster than rabbits fornicating. “Woe is me. I can’t take how awful everything is in my life!” I lament to my wife on FaceTime from my recliner in my air conditioned house. So really, my planning ahead stems from, not an affinity for it, but just trying to avoid another panic attack. It would be nice to say that I can go into any situation unafraid, having my abilities to fall back on, but trust falls with myself end up proving myself to be rather wispy.

I wonder if the ability to wrap your arms around and not succumb to your circumstances is a character trait that you must be born with—and if you’re not, you’re screwed—or if it’s a skill that can be instilled and cultivated. Likewise with those who lack cognizance: Do they come out of the womb oblivious, or did they figure out at an early age that there are very few things worth worrying about? They seem to be happier than the rest of society, as if they are impervious to the grinding down of the soul the rest of us endure as we toil through our drudgery. Watching them float through life, leaving a mess in their wake which others clean up, I wonder if securing happiness is more simple than I thought. What if all it really requires is, instead of worrying about all the things I have to do and be, just not worrying at all? “Ignorance is detrimental to your mental well-being,” is that the saying? No, no, that’s right: “Ignorance is bliss.” Maybe that oblivious bunch is onto something.

March 2, 2017

No Longer a Thorne in My Side

Joshua Earle / Unsplash.com

Joshua Earle / Unsplash.comI finally managed to finish up The Complete Short Stories of Nathaniel Hawthorne. The work of this author was one of the last literary frontiers I had yet to explore. This wasn’t from a lack of opportunity, I just had no interest: I had endured a compulsory reading of The Scarlet Letter years ago, and with each page turned in that novel I began to wonder if it wouldn’t be worth it to poke out my own eyes to get out of reading any more. That experience still haunting me, I wasn’t exactly giddy when I saw this collection of short stories, but I knew familiarizing myself with one of our most prolific authors was a rite de passage for me as a writer, history buff, and American.

So, holding the book a little away from me and flinching slightly, I slowly cracked it open, expecting nostalgia and moral condemnation to leap out at me. No such phenomenon occurring, I relaxed and took some time to behold it; the bibliophile in me was actually a little captivated by the musty smell, yellowed pages, and imperfect print. I started off slowly, painfully plodding along, but by the third or fourth story, I started to get the hang of it. I eventually became a Hawthorne-deciphering machine, plowing through pages at finger-fatiguing pace—I felt like Neo at the end of The Matrix when he sees everything in binary code.

Reading his works gives you plenty of “meta-matter,” to contemplate—as is to be expected from allegories—but I was surprised by how much of it in this anthology can still be applied to modern life. When you travel back through the many epochs and technological breakthroughs to Hawthorne’s time via his writings, you find the same basic fears, joys, faults, and struggles that sculpt our lives today. I found a predicament in “The New England Village” that differed little in similitude from one I personally have faced and contemplated before. The woman with whom the narrator is conversing divulges the hardships of her upbringing. As she is telling her tale, one line jumped out at me: “I was an orphan, and lived with my grandmother, who was as different from me in her habits and opinions as old people usually are from young ones.” It was another universal truth that Hawthorne had woven into a tale.

Some of the exhortations in other stories are more overt. This is sort of a letdown for the sleuth types that like to sift through mystery and intrigue to discover the author’s message, but their being affirmed by the characters gave them greater force and credence. One such instance was in “Graves and Goblins” when the narrator—the ghost speaking from his experiences in the hereafter—states to the mortal reader: ”Let nothing sordid or selfish defile your deeds or thoughts, ye great men of the day, lest ye grieve the noble dead.” My first reaction was, “Oh, that’s kinda cool.” Then terror struck: I mean, actions I get, but thoughts too? Man, my mind has grieved a lot of noble dead.

There are those, though, where you have to dig below the surface; “The Snow-Image: A Childish Miracle” is a fine example. Read literally, it’s just a tale of an obtuse dad that melts his kids’ snowman, who he thinks is a real child, by bringing it inside despite their pleas to leave it outside. But contemplating it further, one deciphers Hawthorne’s message: Even when attempting to do good, if you disregard the opinions and wishes of others, you can do harm. I started with this story (for no other reason than I like snow), and that proved auspicious because it was so captivating that it made me want to delve deeper into this author’s world. The story was beautifully simple yet elegant, detailed yet easy to read; after reading it, all of the preconceptions I had about Hawthorne melted away. (See what I did there?)

As an added bonus, the peruser (it’s my blog; I’ll make up words if I want to) of this anthology gets a crash course in the intricacies of sixteenth- to eighteenth-century New England history. Some of the important figures that pop up I knew of, but I never understood the significance of their strife or tyranny or triumph until given perspective by these tales. Some of the short stories provide insight into the politics of the day, others the customs, and show how both caused distress in the average person’s life. “The Gentle Boy” depicts the conflict in a certain village between the Quakers and the Puritans (two savage bunches, I know, hurling epithets and wishes for eternal damnation in flowery prose at each other). Their mutual animosity stemmed from ideological differences that eventually led to violent means of forcing conformity, and caught in the middle is a young boy who is orphaned by the persecution of his family. It was yet another cautionary tale whose hand seemed to reach through the ages to today to yet again wag its rebuking finger at mankind.

Some stories have silly character names and outlandish circumstances like a Poe story, which was a welcomed change of pace from the generally heavy style of most. But they are easier to read than Poe’s because half of it isn’t in a foreign language or in reference to a figure from classical literature. Some stories had a sentence or two of print-worthy text jammed into five pages. A small number were pretty bland—more informative than enthralling, like a Terms of Use agreement—but made up for it by the last sentence or two conveying some unique insight that I found myself contemplating days later. Fewer still didn’t excite me much at all in any regard.

Overall, this is a fantastic collection of Hawthorne’s short stories; the perspective-changing, age-old wisdom that is bestowed upon the reader far outweighs the few short stories that were lackluster. The language, to my pleasant surprise, was a daunting but ultimately surmountable obstacle; if you enjoy a vocabulary challenge, this is a pretty stout exercise. He was quite adept at vividly describing scenes and circumstances and emotions—allowing the reader to experience the beauty and torment of life right along with the characters—and it was on full display in these stories. My only regret is that I waited so long to start reading it.

November 4, 2016

Mommy Guilt, Daddy Style

photo courtesy of gratisography.com

photo courtesy of gratisography.comHaving two kids under the age of five is soul draining. (If you have more than two, 1) Congrats for having the mental fortitude to withstand that onslaught, and 2) You may judge me for complaining about only two. Now, back to my plight.) It is impossible to fully illustrate just how much your life changes with children. And not from a personal standpoint—you are still you, your hopes and dreams (while sometimes crushed) are still yours—it’s the everyday that is completely altered. When you wake up, where you go, who you see, how and when you talk to your spouse—it all changes once you become responsible for another little human (I type this as I’m working my computer chair around Big Blocks in order to roll it closer to the keyboard).

The demands on my time are now myriad; time to and for myself is a quaint pastime that I pine for regularly (think Thomas Kinkade rendering of me in a bay window, looking longingly out across snow-covered hills). All of the free time that I used to have at my disposal I carelessly filled with frivolity, which could be why it was such a hard adjustment when it was supplanted by something of such gravity as the well-being of children. I at first readily, happily fulfilled the demands of my new role as a dad: I had the formula and breast milk all portioned out ahead of time, the wipe warmer was always stocked, I didn’t even pretend to be asleep all that often when they started to stir in the middle of the night! But the requisite tasks of maintaining that well-being progressed from the simple and sustenance-related to things like making sure I put the right color straw in the right cup for milk, that there’s the right kind of fruit snacks in the lunch bag, or putting sufficient space between dinner table seats that I’ll know it’s a lie when I hear, “She’s touching me!”

And it’s in those moments that I start to wonder just what the hell I’ve gotten myself into. These sacrifices of time and sanity are individually small, but after enduring them one right after the other, I end up in survival mode—worn down by the meltdowns of increasing triviality—wherein I’m willing to subject myself to just about anything to get through to bedtime. I never imagined I’d be one of those parents who cuts the crust off my kids’ bread—They can suck it up, I’d think—but I discovered that some battles you just cannot win; it’s like trying to stop a wave. So there I am at lunchtime, angrily slicing off the margins of grilled cheese sandwiches just to maintain the peace. I sometimes try to sneak in something on the TV that’s just for me, that might provide some mental stimulation, but it inevitably gets overruled. My solution has been to go find the most highbrow literature I have on hand and read it, just to prove to myself that my brain hasn’t turned to complete mush after 12 consecutive episodes of Yo Gabba Gabba!

But the strangest thing happens when the tablets are turned off and the kids are tucked away in bed: I feel guilty. How is that possible? We played and laughed and adventured throughout the yard all day; a tear comes to my eye as I look off into nothing, reminiscing. Then it hits me: I’m the problem, not what we did or didn’t do. I was distracted, I wasn’t all there today: I had that thing I was thinking about while pushing the swing, that text I had to check at the park, that news story I just had to read on the merry-go-round—all the while my kids were pawing at me for affection and attention, though I didn’t notice, not until I replay the day in my head. I did all of those things with them thinking it will be good for them—for us—but since I didn’t interact with them, it was if we didn’t go at all. I didn’t know that I was (unconsciously, in my defense) indulging in the things that I wanted to do and are pleasurable to me. Now I feel guilty for wasting that opportunity. This guilt, this regret that ensues when I know I didn’t do what I could have, is harder to grapple with than that of not being able to see them at all.

The mantra in my head to prompt me to enjoy the opportunity when I’m out with the kids is: “Don’t be absent, physically or mentally, in the moments that make life worth living.”

October 11, 2016

The Cognitive Debris Endeavor

Cognitive Debris has finally been realized. An anthology of my writings, the works within it range from short stories, to poetry, to random thoughts that are expressed in a just a few sentences. They are my attempts to capture and relay, in fictional settings, the snippets of meaningful and poignant things that life threw across my consciousness from time to time. The book as a whole is a reflection of how I experience life: not as a linear succession of events, but rather in bursts of emotions—what occurs is less significant than how it makes me feel.

It’s an intentionally small book. It’s for people like me that never liked reading because reading is seen as arduous and time-consuming. It’s a quick read, with most stories occupying only one page so that reading it doesn’t feel daunting—you can feel like you’ve accomplished something after just one trip to the bathroom!

I want to give a shout out to my big bro, as he took the photo that is the background of the cover and helped edit.

I want to thank my wife for facilitating the transition of my dream to reality (and not just when she married me). She was the one I bounced countless ideas off of with regard to content and aesthetics. When I got stuck on something, and the book became less of a fun hobby and more the bane of my existence, it became hers also. She bore with me the burden of completing it—at times more than her share. She helped edit and is responsible for the layout of the cover and many aspects of the interior.

I also want to thank all the other people whose time and thought touched this work; their input helped sculpt it into its current, presentable form.

I hope you enjoy reading it as much as I (at times) enjoyed writing it.

October 7, 2016

Procreation

Denis Gavrilenco/Unsplash.com

Denis Gavrilenco/Unsplash.comFew things have been romanticized to the same degree that the primal process of producing offspring has. You call it something sweet and innocent—“making love,” perhaps—and the embarrassing faces and sporadic grunting are excused. I don’t mean to disparage this romanticization—romanticizing is a certain panache that, when applied to the less pleasant aspects of it, makes society more civilized. It is euphemistic; and I myself am a man who employs this particular brand of euphemism to make humorous or non-committal my proposals to endeavor to procreate so that if they are denied, I can laugh them off as merely a silly whim.

Men of all stripes have danced this dance of being roundabout and indirect about their desire to satisfy the lust that manifests in their loins, being ignorant of the best timing and intensity of the delivery. And this applies to our emotions generally: We are unsure of what is most appropriate for the situation, so we err on not expressing anything at all. This gives women the impression that men lack emotion; nay, it is not emotion that we lack, rather judiciousness. So when it comes to something as momentous as satisfying one of our most primal, most powerful urges, we at least understand that its gravity is paired with equal delicacy and try not to screw it up.

But all of the traditional rules of engagement go out the window when you’re trying to conceive. Before my wife and I were attempting to ensure that our genes carried on, I didn’t understand why people used the phrase, “Oh, Mr. and Mrs. So And So are trying.” Trying? What’s so difficult about the concept? It’s pretty easy to grasp. Even after the first couple of times we “tried,” it didn’t set in because it was fun and exciting and it had a new purpose: you’re creating life! (I mean, yes, we can argue about it being merely a process of transferring genetic information and a reallocation of matter through which all organisms continue their existence and all that, but don’t kill my dream, okay?) Anyway, how powerful does that make you feel, right? But after a while, it just becomes work. All of the innuendos, the stimulatory precursors, the romance—it’s gone. There’s purpose to it, and that somehow strips the fun from it.

My awareness of this became painfully acute when we were trying for our second child. Conceiving our first was a quick process (that happens to a lot of guys, though, right?), so I came into it the second time around with the firm belief that it would be a breeze. At first, I kind of felt bad that she was getting the shaft in the deal since I was enjoying myself without her achieving her goal. But after quite a few unsuccessful attempts, it looked as though this wasn’t going to be as smooth as anticipated; I never in a million years would have thought that something previously so fun would ever become so cumbersome. There started to be talk of ovulation and cycles and most fertile times, and it got harder and harder for me to maintain any interest, let alone passion.

“Just tell me when,” I would say, with a dismissive wave of my hand.

This dispassionate intercourse came to a climax when, as we were getting desperate to bring the conception ordeal to a conclusion, I got a sinus infection. Secretly, I was a little relieved. I thought, “Okay, now we can put this thing on hold. I mean, look at me; I’m a mess. There’s no way she can expect me to perform.”

“Ah, but wait,” she says, “this week, this next couple of days, this is it; this is when it’s most likely to happen!”

“That is not gonna happen,” or, “Dat is nawt gonnah happeh,” as it sounds with my sinuses completely plugged up.

“No, like, right now,” she says, resolutely, as she hits the home button on her phone to check the time. I mean, she has it down to the hour, quarter hour probably.

So there I am, sick as a dog, fevered, struggling to breathe through my congested nose and hoarse throat; there’s minimal contact, no kissing, just straight to the task at hand. It was the most paradoxical position a man has ever been in: engaging in that one act we all seek pertinaciously, and hating every second.

April 21, 2016

Who I Am

photo courtesy of gratisography.com

photo courtesy of gratisography.comI’ve always been the type of person who needs to pour my all into something—I feel most satisfied when devoting my entire attention, emotion, and inspiration to one endeavor. But I never pursued the task of forging my identity with nearly the same fervor. I think that’s because I like a clear beginning and end and subsequent feeling of accomplishment, and that cannot be had with such a lengthy, multifaceted process. There’s no real definitive end to it or established procedure for going about it, or really even a specific thing to work toward. This ambiguity made it difficult to get started on, so I never really did.

I instead poured my all into many, what came to be, inconsequential things that I was certain would make me into the man I wanted to be. I acquired new friends, upgraded my apartments and cars regularly, found new employers offering greater pay—always tangible and superficial things that at the time seemed like the clear choice for quickly elevating my social status and perception of myself.

But many years back, just as I’d reached the zenith, I started on a downward trajectory—as is required of what goes up. All the things and people I’d filled my life with started to break away, because of time or impracticality or volition, and what I was left with was merely a shell of the man I thought I was creating. There was nothing of substance underneath because I hadn’t filled it with the knowledge and experience that life provides along the way. I had avoided the trials and tribulations that build a person’s foundation and cognizance of who they are because it was easier to give myself the excuse that I didn’t have time for them—I was pursuing other, greater things that would make me far happier. (True happiness, I now realize, often comes from doing those things I’d rather not.)

So I found myself at an impasse: I could just plug along through the rest of my life always knowing but never admitting I had gotten off course from who I wanted to be, or I could accept it and work toward changing it. The former seemed kind of depressing, and I knew would ultimately lead to more unhappiness, so I decided to give the latter a shot—see if I could usher in some much-needed change.

Okay, so where to begin? Overhauling yourself is no small task. I mean, I was damn near the point of demolish-it-and-start-over, not just let’s-slap-on-some-paint-and-throw-down-new-carpet. So, there was a great deal of work to tackle in order to bring about the changes I knew would lead to contentment.

I determined the first step was accepting what I had acknowledged. This proved to be challenging because my pride wouldn’t let me think of myself as anything other than the great person my never having been challenged had taught me that I was. I had to convince myself that shortcomings and flaws don’t make me a terrible person; they make me human. Plus, my endeavor to improve myself was itself a commendable act—there are some decent qualities in me after all!

With that done, I could then begin digging into the intricacies of my flaws, bad decisions (how those two were related), and highlighting areas where I could make some modifications.

I found that I had wasted a lot of effort on maintaining a façade, sometimes multiple. My aim was to try and fit in with whatever group it seemed had the greatest potential to further me, and also give me that feeling of belonging I yearned for. But no matter how great a job I thought I was doing of fooling everyone, it would eventually come to light that I did not possess the requisite traits for acceptance into the clique and I’d find myself ostracized yet again. Instead of trying to convince myself that I was someone I wasn’t and forcing the square peg into the round hole, I should have sought out the good things that were actually part of me, allowed them to bolster me, and then let fitting in somewhere happen organically.

I realized that I was seeking a grander profession as a means of improving my sense of worth and purpose—not by doing greater deeds or being more sincere and empathetic, but a greater title. One thing they say about men is true (because that’s all I’ll admit to right now): we are defined by our jobs. It is insufficient to be called a dad, husband, son, etc., because that doesn’t serve to describe “who I am.” But doesn’t it? Aren’t those titles of greater consequence than what any occupation can provide? I now see the folly in my old thinking. Who I am certainly affects what I do, but what I do is not who I am.

Ultimately, it was my pursuit of this phantom man that I thought I should be that led to a loss in my sense of direction and what I really wanted out of life. If I want to fill this shell, I need to get back to what used to make me feel validated and happy with myself. I need to embrace who I am. Only then can I embark upon and enjoy the journey of life as I was intended to.

March 12, 2016

Tethered to the Past

Oscar Keys/Unsplash.com

Oscar Keys/Unsplash.comSomehow my time is always in short supply—a strange phenomenon for something that is infinite. With two rambunctious kids and an amazing wife, whose happiness is my first priority, there are a lot of demands on my time. I do my best to keep up, but given the finite amount of focus and mental capital at my disposal each day, that endeavor does not always yield the desired result. I’ve tried to break the stereotype about males and prove that I can multitask, but I generally just find myself dividing my attention between two things and accomplishing nothing of value with either. I have aspirations of being stellar at all of my obligations, but maybe it’s time to lower my expectations: “Today I managed to put on pants and no one had to go to the ER, score one for Steve.”

I often wonder if those who subscribe to a circular concept of time are any happier, knowing they’ve got an unlimited number of go’s at this life thing. They can sit back, relax, and not sweat the small stuff, knowing that they’ll have another chance to do it right the next time around. It certainly offers some enticing advantages.

I still think the linear concept jives better with my outlook and expectations of life, though. I don’t like the idea of doubling back and experiencing all the crappy things again—once was enough. Nor do I like the idea of being indefinitely encumbered by my mistakes until I work them off. See, I’m big on having the option to ask for forgiveness (I’m a dude, so I’ve had to ask for it . . . well the number’s not important right now—enough to know the routine, okay?). It’s a wonderful thing for two reasons. First, with forgiveness comes the opportunity to move on—let that water pass under the bridge. Second, I like to do something once and be done with it, and that’s typically how forgiveness works, at least when the beseecher is sincere: you ask, they forgive, it clears the air, everything’s back to sunshine and lollipops. That could be called laziness, but let’s call it efficiency—that has a much more positive connotation. The point is, a linear concept gives me a feeling of moving, not just on with my existence, but away from something regrettable, which is liberating.

A linear concept also focuses my attention on doing now the things that will improve my future, on progressing past my current imperfect state to one that is more deserving of praise and imitation—for my benefit and that of my posterity. But I’ve found that working toward a brighter future requires quite a bit of retrospection. The future is full of potential and myriad wonders, but without the guidance of the past, the road ahead can be full of snares and misery. I’ve been down that path of snares and wasted a great deal of time freeing myself from them. That process was arduous and time-consuming, but going through it, I learned that completely severing yourself from the past can be just as detrimental to furthering yourself as only ever living in it. I also learned that while ambition must be tempered by wisdom, it shouldn’t be overruled by it.

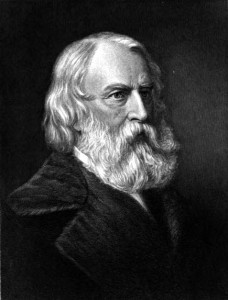

And that is the challenge I face: embracing the wisdom found in my past without letting the follies there become a hindrance. This can easily happen, for there are quite a few, which is why retrospection is just as likely to enlighten me as it is to shroud my path forward. It’s beneficial to place the mistakes of the past into a repository of experience so that they can be accessed later when in search of guidance or charting new courses. However, too keen a focus on them individually tends to be counterproductive: Like looking at photos from my awkward middle school years, I sometimes find myself doing nothing more than sifting through them and being embarrassed, overwhelmed with regret, and forgetting why I even started searching in the first place. My new aim is to use them to my advantage, as Longfellow describes in “The Ladder of Saint Augustine”:

Standing on what too long we bore

With shoulders bent and downcast eyes,

We may discern—unseen before—

A path to higher destinies,

Nor deem the irrevocable Past

As wholly wasted, wholly vain,

If, rising on its wrecks, at last

To something nobler we attain.

March 5, 2016

Read? Yeah, Right.

photo courtesy of gratisography.com

photo courtesy of gratisography.comI hated history and literature when I was in high school. I avoided them because I was intimidated by what I didn’t know and frustrated with my inability to comprehend them. Looking back now, I realize that not overcoming these obstacles really stunted my development and shut a lot of doors for later vocational endeavors. I wish so dearly that I could go back and make myself understand this before I completely wrote them off as inconsequential subjects. But, I might not be sitting here writing this blog if I had, or taken the same journey to get here that I did, or woken up soaking wet and half naked on a living room floor in a house I didn’t remember going to…but that’s a tale for another time.

My hatred for those two facets of learning was not because of the subject matter per se, it was my dislike for reading, which is a pretty essential process for understanding them as the typical means of transmission is to print them in a book and all. I avoided reading like the plague, only ever doing just enough of it to get my assignments done—not realizing that this was making subsequent assignments that much more difficult. I also started to fall behind my friends, and that gap only became more apparent as we progressed through more grades. By my Senior year, I was struggling to get through basic, English 4 while they were sailing through AP English. I would hear those more gifted friends discuss Dante’s Inferno, the brilliance of Shakespeare and the wisdom that could be gleaned from his copious body of work, all while I was doing my best to feign comprehension and feverishly look up in the dictionary the words they were using.

I read “The Masque of the Red Death” with the rest of my class and all that started to change (though it wasn’t until years later that I was able to pinpoint that as the moment I went from dreading to enjoying reading). It was by this Poe guy that I’d heard of before. I knew he was a great author, one of the best, so my friends told me, so I immediately went to my default of being intimidated by something new and complex. But to my surprise, I was able to keep up as we made our way through the work, and I actually found myself enthralled with the story—as well as wigged out by it. Through the effect that reading it had on me, I started to see that writing was a way to communicate ideas and imagery just as effectively as photography or cinematography, if not better than in some situations. This change of perspective prompted me to give some other works a shot, wanting to see what wonder and intrigue they had to offer.

Shortly thereafter I read The Catcher in the Rye at the behest of a buddy of mine, one of the aforementioned smart ones. I wasn’t quite at his intellectual level, but this dude saw my potential and insisted that I read it, for he was certain I would enjoy it. So with my newfound willingness to try the seemingly impossible, I agreed to read it, though I had some serious doubts about being able to. Swallowing my pride, I explained to him that I would need to borrow his copy of the novel seeing that I wasn’t in the “Highfalutin English Class,” as I mockingly called it. (I mocked it for two reasons, neither of which were mature: I was intimidated by the works they were studying and their ability to so easily process them as well as embarrassed by my own ineptness.) Now, we were both recluses and socially awkward, so our paths crossing and us hitting it off over a book telling the tale of a socially awkward recluse really pushed the limits of how much irony one relationship could bear. But the fortuitous encounter pushed me up to and beyond the boundaries of what I thought I could achieve, and this work is a fine example. For as I dove deeper into it and forgot all that kept me from reading it before, I understood it—I knew what was going on! Suddenly, all this reading stuff wasn’t so bad. In fact, I was starting to like it.

My literary conquests continued to accumulate and I grew increasingly confident, but it was not without great effort. The most formidable obstacle I had to overcome at the onset was the intimidation mentioned previously. If I came across a classic or a work that came highly recommended by my peers, I would immediately exclude understanding it as an attainable goal. To combat this, I instead sought out pieces that were bite-sized—my bite size. It would be a short story or short poem that was just out to the margins of my comfort zone so that I would be able to read it and comprehend it. This would bolster my confidence and empower me to work up to those more difficult works that were so mysterious.

The other obstacle that was problematic, and still is with each new book I pick up, is growing accustomed to the way the author “speaks:” his unique choice of words, cadence, and the way sentences are structured and punctuation inserted to amplify the ideas expressed within them. I find it takes until about the end of the first chapter to really start seeing and feeling what the author intended to convey, and this is especially true with older works.

My journey has been long and arduous (having handicapped myself so early on), but I’m finally starting to reap the benefits of putting in hours with my face buried in a book. I haven’t built up my literary chops to the level I’d like, but as with a physical skill, one must start out at the bottom and work up to the goal that’s been established—and continue working even after it’s been met or else stamina and proficiency begin to wane.

February 28, 2016

The Clarity of Retrospection

photo courtesy of gratisography.com

photo courtesy of gratisography.comA concept I had a hard time comprehending in my younger, wilder days was that if my prospective mate doesn’t get along with my family, that’s a bad sign—a sign this person might, ultimately, not get along with me either. The best and worst thing about my family is they’re like me—they know me and what’s best for me when I don’t, and it’s infuriating when they’re right despite trying to prove them wrong. And when’s there’s consensus the farther I expand the circle of members from which I seek advice and approval, the more right they all are. (I’ve also found that if I have to go outside of my immediate family for approval on something, it’s probably the wrong thing to do.)

I had to learn this the hard way, as with most things I’ve learned. Now, this is not to say that since the means of acquiring this knowledge was heart-wrenching, and embarrassing, and a whole host of other adjectives which make for an uncomfortable experience when applied to your existence, that I retained the knowledge any more completely. Nay, I often forget and have to learn it all over again, with the same pains and regrets. You’d also think that I, knowing I’ve preferred the hard way over the years, would have adopted a new, enlightened standard of trying the easy way first, just to see what it’s all about. This also has not happened.

I know what the easy way is; I know my family’s advice is worthy of consideration. But I shirk it—I’m confident that I can defy the odds. I proclaim, waving a dismissive hand at those warning me: “Bahhh, I know what I’m doing. I know others have tried and failed when ignoring all of these red flags before, but I’ll make it work. I’m the exception!” Then I find out how unexceptional I am and that their admonitions were spot on.

So I guess this is a roundabout apology to all those people whose advice was compassionately given but I refused to heed.

February 27, 2016

Uplifted by Longfellow

I finished Longfellow’s “Evangeline: A Tale of Acadie” today. Admittedly, after the first few pages, I was certain I knew the trajectory of the poem—just another banal tale of romance, of lost love and subsequent suffering—and started to lose interest. But knowing Longfellow hadn’t disappointed me before, I read on, and as the rest of the story unfolded I got a sense that it was heading in an unexpected direction. That direction ultimately led to a climax that was gloomy, yet surprisingly uplifting.

Fast-forwarding to said climax (doing a great disservice to the rest of this fantastic piece for the sake of brevity): a plague descends upon the town that Evangeline and her husband, Gabriel, inhabit and kills the majority of the people. (A quick interjection: Longfellow writes, “Wealth had no power to bribe, nor beauty to charm, the oppressor,” describing how powerless the people were to fight it. Reading that made me realize that regardless of our accomplishments, station, or class, we are all still just humans—empowering yet discouraging.) Gabriel is among those unfortunate enough to contract the illness and he passes, at which point Evangeline presses her husband’s lifeless head to her bosom and prays: “Father, I thank thee.”

That expression of gratitude changed my perspective on death entirely. I used to only see it as this terrible, irreversible separation that rips your heart out and sets you on a course of suffering and lament. But in her case, it brought closure—an end to the sorrow, the uncertainty, the futile hope and yearning. I had never seen death as something that could bring relief before.