Harry Harrison's Blog

October 7, 2025

Harry Harrison Centenary – Part 12: Men’s Adventure Magazines 2

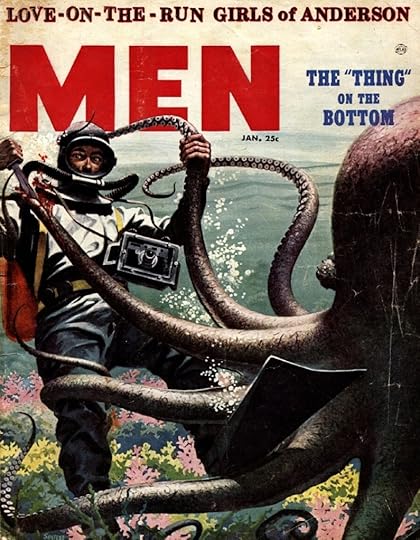

Men Vol.5, No.1, January 1956, edited by Noah Sarlat. Cover painting by Frank Soltesz for the story ‘The “Thing” on the Bottom’ by Joseph Santio. Image from PulpCovers.com

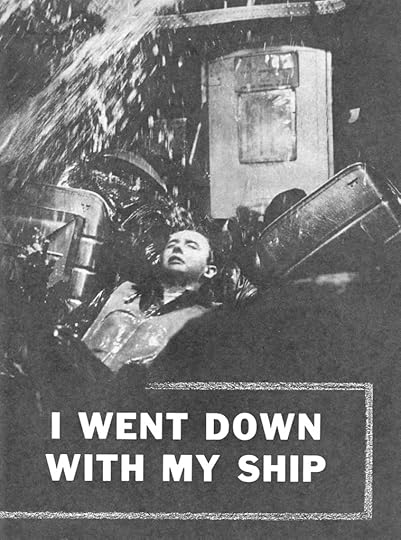

Here is one of Harry Harrison’s earliest men’s adventure articles – there were three published in January 1956. This one closely follows the ‘formula’ that I referred to in the last post. I’m not sure if Hubert Pritchard collaborated on this one or not. The accompanying photograph (see below) is uncredited. Some of the photos HH submitted with his articles came from picture libraries, and some were staged by him using people he knew.

The story may have been based on a true event, though I’m pretty sure Harry Harrison didn’t interview anyone called Captain Wilner for the details included here: everything came from his imagination. I did a quick Google search and couldn’t see that Waterhouse Victory was an actual ship. Article length c.3,000 words

The tagline on the index page reads, “She was heading for the bottom and I couldn’t get out.”

I Went Down with My Shipby Captain M. Wilner as told to Harry Harrison

“As she tilted crazily on the ocean floor, I floated around in the water-filled cabin, trying not to use up my last three feet of air.”

The ship gave another sickening lurch and I knew she was sinking. With the floor tilted at a 45-degree angle, I couldn’t keep my footing. Skidding and falling, I crashed against the bulkhead.

Everything had happened so fast there was no time to think clearly. Only one thing kept echoing around in my head: You’re Captain of this ship, why aren’t you on the bridge when she’s in trouble? I didn’t consider my own life, not then. All I knew was that I was locked in the radio room while my ship was heading for the bottom.

It was like climbing a wall to get to the door but I did it, hand over hand. I turned and pulled the handle but it was no use, the damned thing was jammed.

I was pulled loose from the door as the ship rolled again, a slow, frightening roll that didn’t stop. The lights went out then and I tumbled down the bulkhead with all of the loose equipment. The roll finally stopped, but the ship had turned completely over! There was a feeling in my gut, the kind you get when an elevator goes down too fast. We were on the way to the bottom. The ship was sinking and I was trapped inside of her.

A sudden roar blasted through the metal of the hull, followed by a tremendous hissing and bubbling as the sea water reached the engines. That explosion had been the death blow, the escaping steam was her death rattle. I floundered there in the darkness as we slid toward the bottom, waiting for the end. After a few moments the noises diminished, except for the creaking of the hull plates as the pressure worked on them.

At any moment now the steel walls of the radio room would be squeezed in and I would be crushed under a million tons of water. I wasn’t frightened; my mind was numb. I wasn’t thinking or, feeling. I and my ship were alone down there in the eternal darkness; we were going to die together.

The ship touched bottom, sinking into the ooze slowly, tilting as she settled. A sudden roar shattered the intense silence as some of the bulkheads gave way under the pressure. The water foamed up to the radio shack. I felt the door shake and was splattered by a jet of icy water that sprayed in around the jam.

It was the end.

Photo: Uncredited

Photo: UncreditedDrowning men are supposed to see their lives flash before their eyes, a sort of speeded-up newsreel, but that’s so much bilge. I didn’t see a thing except stars from banging my skull against the transmitter. I was angry, too. The Waterhouse Victory was a new ship and this was her maiden voyage. The crew and I had sweated blood getting her into shape.

She was a war baby, turned out by a bunch of ham-handed welders who in peacetime couldn’t have landed a job soldering tin cans together in a sardine factory. She was slow and we almost ripped her turbines out, but we managed to keep up with the convoy. The wolf packs were out and we had to dodge them all across the Atlantic. We would have docked the next day – if that tin fish hadn’t found us first.

The funny thing was, none of us were expecting it. We were off the coast of Madagascar, running near the center of a hundred-ship convoy. Land-based planes swept this area every day, and the sea was thick with tin cans and DE’s with listening gear.

The intelligence report said that the area was clear of subs. When we heard that we all eased up and began to feel as if the crossing was behind us. We still slept with our shoes and life-jackets on, but at least we slept. I made sure each watch had some decent sleep, then we got to work on the ship. Two straight weeks at battle stations and you have a filthy ship.

She was a mess. Broken gear in the passageways, shell casings underfoot wherever you walked, and decks as filthy as an island trader. We couldn’t throw the gear over the side because subs could track us by it. I had it all pushed in on top of the cases in number 2 hold, figuring to get rid of it when we hit port.

A heavy sea had washed right over the Waterhouse Victory the third day out, stoving in all the starboard windows on the bridge. We had rigged temporary canvas covers, but they were awfully drafty. These were taken down and wooden covers battened into place. When I saw that things were going well, I went into the radio room to look at the latest BAMS message. My First Mate, Costello, was on the bridge, the ship was in good hands.

Sparks handed me the sheaf on the clipboard and went back to monitoring the emergency frequencies. I never had a chance to look at the BAMS – the deck jumped under me and I was hit by a sound so loud it was as solid as a wave of water.

Sparks was on the floor, bleeding from the mouth, too groggy to move. I picked him up and slammed him into his chair. He was coming out of it, groping for the key. I dived for the speaking tube to the bridge and tore open the gas lid.

“Costello, what the hell was it?”

It couldn’t have taken him more than seconds to answer, but it seemed like hours to me. I hung there, cursing, until his voice rasped back.

“Captain… we we took a torpedo aft. The sub must have been lying on the bottom waiting for the convoy to come over her.”

“All right. Hold on. I’m coming up!” As I turned from the tube I saw Sparks hurl down his phones and dive for the battery room. He shouted over his shoulder:

“Power is off, Captain, have to hook in the auxiliary.”

A second explosion hit then; it must have been the ammunition in number 3 hold. That blast ripped out the bowels of the Waterhouse Victory, because she reared up like a wounded animal. The deck tilted like a coal chute and I slammed back into the transmitter. Everything seemed to break lose at the same

time and rain down on me. I saw the door swing out and slam shut. It was like climbing a gabled roof to reach that door, but I managed to do it. I swung from the handle, but the door was jammed.

Sparks would have to help me. I couldn’t force it alone. I skidded in back to the wall and over to the door of the battery room. My angry shout to Sparks died on my lips.

He sat against the wall with his eyes open. staring at me. He wasn’t seeing me though, his skull had bashed into the corner of the battery rack with the last explosion. It had put a five inch hole in the bone. Must have killed him instantly.

The ship was still listing badly. I had to find out what was going on. I grabbed the speaking tube again and got Costello back.

“Captain, the main shaft’s cracked and we’re taking water in over the stern into hatches 3 and 4. Six dead in the engine room – they’re filling up fast – twenty degree list to port!”

“Clear the wounded from the flooded compartments, then abandon ship. I’m locked in the radio shack. I’ll be there as soon as I can find something to break the door down with.”

That was when the Waterhouse Victory started her long slide to the bottom. I’d seen it happen to other ships – from torpedoing to sinking, maybe eight minutes. Now it was happening to me.

I realized then, for the first time, that I was going to die. I had been too concerned about the ship to think about any personal peril. Now there it was, staring me right in the eye. We were on the way to the bottom and there was nothing I could do about it, except go down with my ship.

With the lights out and the grave-like silence of the sea all around, it was like being buried in a giant, steel coffin. When the ship hit bottom I knew that this was it.

The seconds ticked by, each one seeming the last, as I waited for sea to crash through the bulkheads and destroy me. The water rushed up to the door of the compartment and pressed against it. I could feel the thin, cold streams that spattered in around the frame. A rock-hard stream hit me from behind, knocking me off my feet. At first I thought the bulkhead had given way, until I realized it was a jet of water from the speaking tube, forced through it from the bridge.

There was water up to my knees now and it was rising fast. My ears cracked as the incoming water compressed the air. In a few minutes it was up to my armpits, and then I was floating. I should have

been dead and I wasn’t yet; at this instant my first spark of hope was born.

The Waterhouse Victory must have sunk over the very edge of the reef that extends out from the Madagascar coast. The reef here was about 300 feet down. Where it ended, the drop went down to

over a mile. I guessed the ship was on the reef from the length of time it took us to sink. Even as I thought this, the ship shuddered and fell a ways before grinding to a stop. At any moment she might sink into that mile deep valley.

If I could get out of the ship now I might stand a chance of reaching the surface alive. However, if the ship took that mile plunge, I would be crushed long before we reached bottom. I had to at least try to get free.

The water had stopped rising in the compartment, evidently the pocket of air that was trapped there had been compressed to the point where it could withstand the outside pressure. I didn’t know how long this air would last. I had to get out while it was still breathable. To do that I needed a light. There was a waterproof flashlight in one of the file drawers. I had to find it.

It was like swimming in a nightmare. I felt along the wall until I got my direction, then took a deep breath and dived. I ran out of breath before I located the drawer and had to come up for air. On the fourth dive I found the flashlight, surfaced, and turned it on.

I treaded water and threw the beam around the compartment. It was filled almost to the top with black water. There was about three feet of airspace left between the water and what used to be the floor. The door that opened out of the radio room was on the far bulkhead. I pushed over to it. I tested it but it didn’t budge, still jammed tightly shut.

This door would be my first barrier; there was a companionway outside and another door to get through before I was out of the ship. That door led out onto the upper deck which, since the ship had turned turtle, might be buried deep in the mud. I would face that possibility when I came to it, right now I had to open that jammed door.

I had a clasp knife in my pocket, a big one that I had carried ever since I first went to sea. After I shoved the blade into the crack between the door and the jamb, I levered it back and forth as hard as I dared. The door wouldn’t move. I pushed harder and the blade snapped. There was a stub of blade about an inch long left; it barely fit into the crack of the buckled frame. I breathed a silent prayer and pushed it in. Slowly and reluctantly the door shifted. The knife dropped from my fingers as I jammed my

shoulder against the door.

It gave all at once and fell open – and took half of my air with it! What was now the top of the door had cut halfway across my airspace; when it opened that much air rushed out. When I treaded water now, my head hit against metal above me. This bit of air that was left was already getting foul. It was time to

get out.

For a moment, I lost my nerve. I visualized the tiny, crushed wreck of the Waterhouse Victory lying there in the muck of the ocean floor. I saw the schools of fish that nosed about it and the awful weight of the water on top. There was no way of knowing for sure how deep the water was, but it must be at least 300 feet. Without breathing or diving equipment of any kind, I had to force my way up through that water to the surface. The choice had to be made. If I stayed in the ship it was certain death; if I tried for the surface I had some chance of getting through, no matter how small.

I was getting out. The first thing was to get rid of extra weight. I kicked off my shoes and managed to struggle out of my heavy jacket. Then I held onto the door frame, so I wouldn’t have to tread water, and started deep breathing. I’ve seen native fishermen in the islands and Japanese pearl divers do this. They soak their bodies with oxygen for deep dives and stay under water for minutes this way. I did as much deep breathing as I could, then took one last big lungful of air. Holding the flashlight in front of me, I dived down through the door.

It was about 30 feet along the passageway to the outer door. I made it as fast as I could and grabbed the edge of the door that was standing halfway open. When I pulled it to me and pointed the flashlight through the opening I almost gasped out all my air. There was a wall of mud outside.

I reached up to the top and pushed with my free hand, the mud seemed looser there. I dropped the flashlight and took the only chance I had. Kicking with my feet and pushing against the door frame

I forced my head into that black muck. It closed about me. I could feel it being forced into my nose, my ears. I could only have been in the mud for a few moments, but it was forever. My hands were free of the door jamb so I set my feet against it and pushed as hard as I could. Reluctantly the mud gave up its hold and I was through into the water.

I blew all the air out of my lungs and started swimming for the surface hundreds of feet above. It was the hardest thing I ever did. Every part of my body said hold your breath, yet I knew I would be dead if I did. One important fact I’ve picked up from the divers I have known is that you can’t come up with a lungful of air under pressure. As you rise higher in the water the air expands, so that by the time you make the surface, you’re dead, with your lungs exploded into a bloody mess by the internal pressure.

I forced myself to get rid of that air, breathing out till I could breathe no more. Then I swam. It was midnight black. I couldn’t see the surface, but I knew I was rushing upwards. I thrashed hard, swimming for my life. There was a ringing in my head and I had to breathe, but I knew there was only water to breathe. Far, far in the distance I saw a glimmer of light that might be the surface, but it was too far away. My eyes were fogging and I had trouble moving my arms and legs. This was nothing compared to the fire in my chest. I had to breathe and I couldn’t stop myself. I knew there was no air, but my body was beyond control now. I inhaled through shaking lips – breathed in pure sea water that burned like molten lead. The water was in my mouth, my lungs. I was choking – dying.

I gasped again and breathed air. My body shot up from the water and flopped back. There was just time for one wonderful breath of air before I was below the surface again. I broke through the surface a second time, gasping and choking on water and blood. As the ache died away in my lungs I became aware of the racking pains that were clutching at my knees. The bends! The pain was gigantic, it curled my legs so I couldn’t use them. I floated with only my arms for support.

The most wonderful sight I have ever seen was the thin, gray bow of that destroyer cutting through the water towards me. I knew they always picked up the survivors of a sunken ship, but so much time seemed to have elapsed I was sure they were gone.

They threw down a rope, but I was too weak to grab on. Two sailors climbed down the Jacob’s ladder and one held me above the water while the other passed a rope under my shoulders. My last memories were of being hauled from the sea like some dripping fish…

I have a desk job on shore now, which is about all the job I can handle with a stiff leg and a chest that still hurts in cold weather. But I’m not complaining, because I got out. Half of my crew are still down there, trapped forever in a rusting hulk on the edge of the Madagascar reef.

Paul Tomlinson is the author of over a dozen novels and books about writing genre fiction. www.paultomlinson.org

September 24, 2025

Harry Harrison Centenary – Part 11: Men’s Adventure Magazines 1

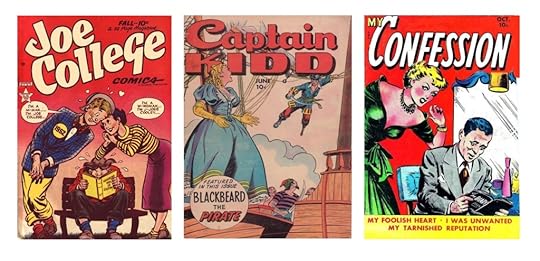

During his time as a comic book artist and editor, Harry Harrison wrote scripts for comics, short text pieces – fiction and non-fiction – that appeared in comic books, and also fake letters and responses to them for letters pages in comics. Harrison left the comics industry as the Golden Age was coming to an end and moved to writing text articles for magazines. He wrote mostly ‘men’s adventures’ but also a few pieces for True Confessions magazine.

When I researched my HH bibliography – published in 2002 – there wasn’t much information available for me to draw from. I had seven definite references plus a list of the titles of original Harrison manuscripts held in the Special Collection at the California State University, Fullerton. That list consisted of over 40 working titles, some of which included a pseudonym used.

Since 2002 I’ve returned to this subject at various points, trying to match up the list of working titles with actual published articles. I’ve also scoured listings of magazines on eBay, often squinting at photographs of contents pages to see if I can identify Harry Harrison pieces. Some of those old men’s adventure magazine have been scanned and placed online in various places and I’ve collected PDFs of relevant issues. And I’ve purchased a few of the original magazines online.

When Harry Harrison was planning to move house, in 2009 or thereabouts, I helped him sort out his files. Stashed in an old filing cabinet I found a folder with tear sheets of some of the magazine articles he had written. This helped me fill in some more gaps in the list. And there were a few bits of correspondence between him and his collaborator Hubert Pritchard.

I’ve also identified some articles that weren’t on my earlier lists, and the number of unidentified items from the Special Collection list is now down to about 30 or so working titles, some of which I have possible sightings of. I would need to see the magazines or scans of the articles to confirm these sightings. I’ll probably include the list of ‘missing’ items in a future post in the hope that other people might be able to locate the published versions.

I’m not sure that I will ever feel confident in saying that I have a complete list of Harry Harrison’s magazine articles, but I hope to get close.

Over the coming weeks I’ll post the text of a few of the more interesting articles, plus some of the artwork and photographs that accompanied them. I’m also going to write a piece on how one of these articles came to be written – Harry had kept all of the paperwork, including the drafts, correspondence, and the original item that inspired it.

In this first post on the topic, I thought I’d introduce some of the people involved in this part of Harry Harrison’s career.

Harry Harrison married Joan Merkler in 1954. Their son, Todd, was born about a year later. I shall write more about Joan at some point in this series. She was a beautiful, funny, and talented woman. And just a little bit scary.

The family found living in New York uncomfortable, particularly in summer, and a small apartment didn’t offer the kind of freedom that a young child would need. Harry and Joan decided to move to Mexico. This might sound like a random decision, but Harry had visited Mexico when he was in the army. And a number of writers and retired soldiers had made their homes there. It was also possible to live there relatively cheaply. Harry Harrison wrote about this decision and about the year they spent in Mexico in his memoir Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison! published in 2014. For the purposes of this post, the most significant thing that happened there was that he met the writer Jackson Burke.

Jackson BurkeJackson Burke was writing articles for magazines including Bluebook, Real, Man’s Illustrated, and Male. In the June 1953 issue of Bluebook, a brief biography was included: “Jackson Burke, who wrote ‘Matadors Die Rich’ (pages 26-32), tried bullfighting after hearing that a good lad at this trade can pick up as much as $20,000 in an afternoon; and that was about the rate of pay Mr. Burke was seeking at the moment. As he tells in his story, he retired from the ring after discovering that matadors aren’t overpaid, after all.

“Born in 1915 on an island in San Francisco Bay (not Alcatraz), of theatrical parents, Burke grew up in a suitcase, earned an A.B. degree at the University of California, taught school, and eventually went to sea. He since has settled down to a writing career and, besides his story in this issue, has written four novels, one of which (The Arroyo) was grabbed by a publisher. You’ll read more of Mr. Burke’s efforts in upcoming issues of Bluebook.”

It’s possible that many of the details in this ‘about the author’ piece are as true as the ‘true adventures’ Burke was writing.

In his memoir, Harry Harrison revealed that he learned how to write men’s adventures from Burke:

“A very simple formula,” Burke explained. “You open with a cliff hanger. Maybe literally one such as a climber reached the top of a terrible climb.”

Below me was a thousand foot drop. To the left and right sheer ice without a handhold. I was stretching upwards to the limits of my strength, clutching the small projecting knob of rock.

And I could feel it crumbling…

“This is called the establisher. As soon as the hero is in extremis there is a the flashback:

How did I get into this terrible position…?

“Now the build which explains what happened, how through a series of circumstances the protagonist finally reaches the cliff where he is hanging on by one fingernail. Then the justifier gives him an unexpected chance at salvation – have him win by guts and ingenuity and he is off the cliff. All in 2,500 words. Type THE END, send it round the editors. Top markets like Argosy paid up to $500 for one of these. Salvage markets – the dregs who bought most anything – were $75.”

Harrison collaborated with Jackson Burke on an article titled ‘Were Carlson’s Raiders So Tough They Had to Die?’ published in the June 1957 issue of Real Action for Men. It’s possible that they wrote more than this one piece together, but this is the only one I have found. The tagline for this article is: ‘What can you do with trained, merciless killers when the time for killing is past?’

Harry Harrison had an agent in New York to help him sell his articles to the magazines. He may have found Sidney Porcelain through Burke or through one of his other writer friends.

Sidney PorcelainSidney Porcelain was a literary agent based in New York. I couldn’t find a single definitive source of information about Porcelain, but I found a few bits and pieces on various websites and I thought I ought to put them together.

The Internet Speculative Fiction Database records that Sidney Edgar Porcelain was born in Leominster, Massachusetts on 7th January 1911 and died 5th November 1997. Porcelain is also listed as having short stories in Science Fiction Digest and Tales of the Frightened magazines. I’ve also seen a listing for one of his short stories in the June 1962 issue of Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine.

Sidney E. Porcelain wrote two novels featuring detective Stephen Clay, The Purple Pony Murders (1945) and The Crimson Cat Murders (1946). The 1945 US edition of The Purple Pony Murders has the author as Sidney E. Porcelain on book jacket; the 1948 UK edition has Sidney A. Porcelain on the jacket. IMDb lists him as the writer of one episode, ‘Ninth Life,’ of the ABC radio series The Clock in 1950. He is also credited as one of three writers of the short film From Inner Space, based on the story ‘Or All the Seas with Oysters,’ by Avram Davidson. A 1969 short film, Hangup, is listed as being a remake of From Inner Space.

Sidney Porcelain (no initial) is the author on the cover of Office Tramp, published in paperback by Midwood Books in 1962. The cover says, ‘Her job was to keep the bosses happy, and it wasn’t by taking dictation.’ This should give you some idea of what kind of book it was.

On the website for Savant Garde Archives, there is a scan of a pamphlet titled How You Can Heal Yourself and Others by E. Sidney Porcelain – it is about ESP. The ‘About the Author’ on the back cover includes the following:

E. Sidney Porcelain has written several books, articles, and short stories. Some of his work is listed in The Best American Short Stories … He has had plays produced and a script on NBC-TV; a short film he wrote was shown at the film festival in Spoleto, Italy. He has acted and directed in several productions and has performed in cabaret theatre, singing his own novelty songs. He has also appeared on stage at the old Metropolitan Opera house in two operas.

I’m including the image below because the cover features a photograph of Porcelain, credited to Dave Ward. The original website address is https://savantgardearchives.tripod.com/E.SidneyPorcelain.html

A note on the webpage says that E. Sidney Porcelain is one of the original founders of The Savant Garde and that ‘the savant garde workshop’ will publish an e-edition of his Purple Pony Murders in 2011. The Savant Garde Institute is the ‘parent company’ of the workshop. I don’t know if the e-edition of the book was made available.

I think Sidney E. Porcelain was also the editor of a literary magazine, Unusual. Abebooks lists Volume 1, Number 1 and Volume 1, Number 3 with publication dates of 1955. The first published by Script Delivery Service, New York and the second by Sidney E. Porcelain, New York. Number 3 also lists ‘Harrison’ as a contributor, but I don’t know if that is our Harry Harrison.

Assuming that all of these details refer to the same man, and there are enough links to suggest they do, he seems to have been an interesting fellow.

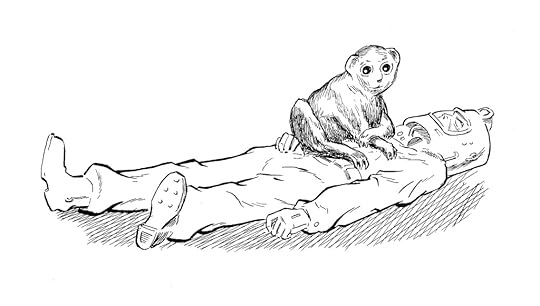

Hubert PritchardHarry Harrison and Hubert Pritchard were friends in high school and they met up again in New York after the Second World War. Pritchard began training to be a doctor while Harrison was training to be a cartoonist and illustrator. As I understand it, ill-health prevented Pritchard completing his studies, but his medical knowledge was put to use when he and Harry Harrison began collaborating on ‘true’ stories for the adventure and confession magazines. Pritchard would look at medical journals, seeking interesting medical cases that could be turned into ‘true’ adventure stories. When Harrison moved to Europe, Pritchard would carry out research into other topics – including military history – for the articles they wrote together.

The medical stories that Harrison and Pritchard wrote were popular with magazine editor Noah Sarlat.

Noah SarlatMagazine Management was a company founded in about 1947 by Martin Goodman, who had worked in the pulp magazine industry since the 1930s. The company published a number of magazines and was the parent company of Atlas Comics which later became Marvel Comics. Noah Sarlat was an editor for the company, editing magazines including Male, For Men Only, Men, Stag, Male, Man’s World, Challenge, and Man’s Magazine. Harry Harrison and Hubert Pritchard’s articles appeared in a number of these titles.

First Men’s AdventuresI know for sure that Harry Harrison’s articles began appearing in men’s adventure magazines at the beginning of 1956. The following all appeared in January of that year:

‘The Cave that Swallowed Me’ by Paul Barrell as told to Harry Harrison in For Men Only – ‘I swam until my fingers touched rock. Then I raised my face, but there was no air. I was in a water-filled tunnel of stone.’

‘The Day They Stole the U.S. Fleet’ by Harry Harrison in Brief (edited by Richard N. Bruce) – ‘It will never be confirmed. But the weirdest story of the war keeps cropping up with a strange persistence.’

‘I Went Down with My Ship’ by Captain M. Wilner as told to Harry Harrison in Men – ‘She was heading for the bottom and I couldn’t get out.’

The last of these is a title that Harry Harrison often mentioned when he spoke about his time writing these articles, along with ‘I Ate a Pigmy’ and ‘I Cut Off My Own Arm.’ You can read ‘I Ate a Pigmy’ by clicking on the link below.

I Ate a Pygmy

Sadly, I haven’t been able to locate ‘I Cut Off My Own Arm,’ but I will post ‘I Went Down with My Ship’ next time.

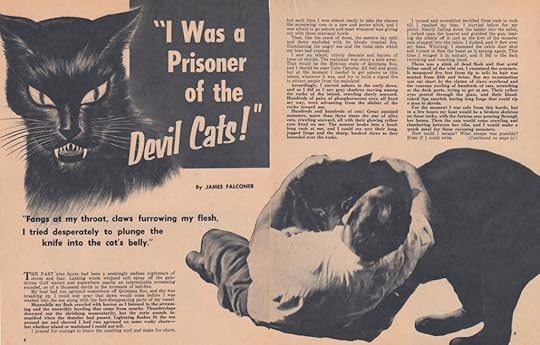

Harry Harrison didn’t write any men’s adventures with titles to challenge the classic ‘Weasels Ripped My Flesh!’ The example below was in Harry’s folder of tear sheets, so I’m presuming it was one of his, and it’s the closest I could find.

Judging by the cover and artwork, I would say that this magazine was probably one of the lower paying markets. The photograph almost certainly came from an agency and looks like it may have originally been a picture of a guy playing with a tame lion. Back in those days, I guess lions did occasionally wear blackface. That wouldn’t be allowed today.

Next Time: I Went Down with My Ship!

Paul Tomlinson is the author of over a dozen novels and books about writing genre fiction. www.paultomlinson.org

July 21, 2025

Harry Harrison Centenary – Part 10: Harry the Artist Part 3: Unpublished and Unidentified Artwork

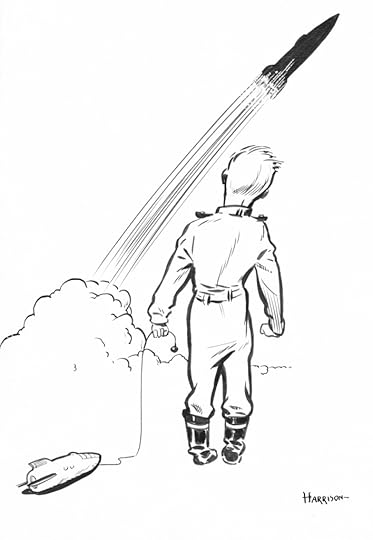

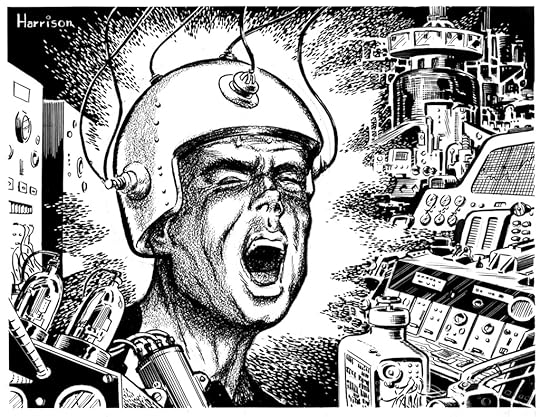

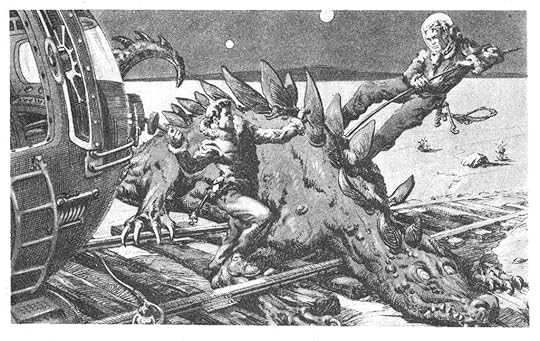

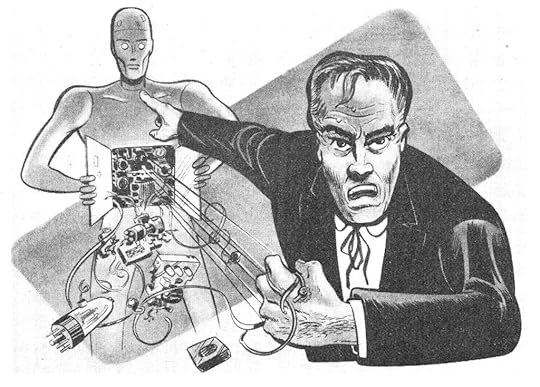

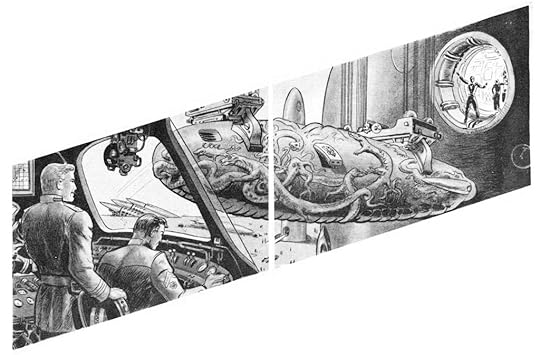

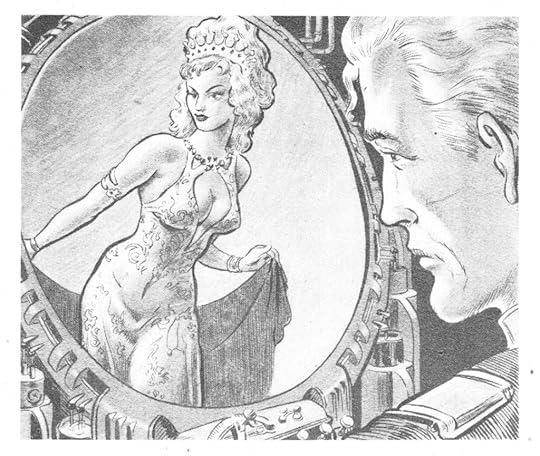

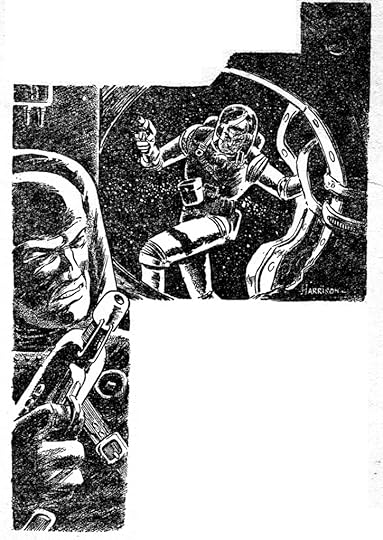

For this last post about Harry Harrison’s work as a professional artist, I have some images that I haven’t been able to identify. I scanned these from pieces in Harry’s portfolio – they were either original artwork or photographic copies.

The first illustration is science fiction but the rest are fantasy/horror in a fairly cartoony style. I have no idea where any of these pieces were published, or if they were published. If you know anything about them, please leave a comment below or contact me via the contact link.

The original artwork for some of these was interesting as they are drawn on textured paper using ink and soft graphite pencil for the shading.

None of the pieces below are dated. I suspect they date from about the same period as the Worlds Beyond and Marvel Science Fiction illustrations, 1951-1952

This one looks like the top was sliced off – I wonder what the monster was saying…

This one looks like the top was sliced off – I wonder what the monster was saying…

The image above is unsigned and is considerably more detailed than the others. Looking at the female character’s face and the hatching technique, I wonder if this was done in collaboration with another artist…

I posted one more piece of mystery HH artwork back in 2007, if you want to check that out too.

Starting with the next post, I will be looking at the articles and short stories that Harry Harrison wrote for men’s adventure magazines. Harry often referred to these in interviews, quoting such titles as ‘I Cut Off My Own Arm,’ ‘I Ate a Pygmy,’ and ‘My Iron Lung Baby.’ There are a lot more of them than I ever suspected, and I haven’t unearthed all of them, I’m sure.

If you want a taster, check out this post from 2007 – for some reason it’s the most visited page on this blog… ‘I Was Sold on the Slave Block‘

June 18, 2025

Harry Harrison Centenary – Part 9: Harry the Artist Part 2: Marvel Science Stories & Galaxy Science Fiction

Harry Harrison provided illustrations for all three issues of Worlds Beyond magazine, published in December 1950 and January and February 1951 – see the previous post in this series. During 1951, Harrison also provided artwork for Marvel Science Stories and Galaxy Science Fiction.

Marvel Science Stories first appeared in August 1938 and ran for nine issues until April 1941. It was resurrected in November 1950 and lasted for another six issues. Both times it was published by companies owned by brothers Abraham and Martin Goodman, and edited by Robert O. Erisman. During its second run it was titled Marvel Science Stories for three issues and then became Marvel Science Fiction for the final three. Martin Goodman had founded Timely Comics in 1939, and this would eventually become the Marvel Comics we know today.

The earlier issues of the magazine featured ‘spicier’ stories than were common in science fiction at that time. It was these magazines more than any other that created the image of science fiction as consisting of pulp magazines with stories – and pictures – of aliens lusting after Earth women. The later issues, including those illustrated by Harry Harrison, featured much more standard science fiction fare. But, although the magazine featured writers including Isaac Asimov, Arthur C. Clarke, Lester del Rey, Richard Matheson, William Tenn, and Jack Vance, historians of the genre note that these writers were selling their best stories elsewhere.

Harry Harrison provided illustrations for four issues of the magazine, May 1951, August 1951, November 1951, and May 1952. For each issue he illustrated more than one story. The images below are presented in their order of appearance in the magazine. All are taken from scans of the magazine unless indicated.

Marvel Science Stories – May 1951‘The Circle’ by Milton Lesser

‘The Polyoid’ by Bryce Walton

Scanned from a photographic copy in Harry Harrison’s collection

Scanned from a photographic copy in Harry Harrison’s collection‘Captain Wyxtpthll’s Flying Saucer’ by Arthur C. Clarke

Marvel Science Stories – August 1951

Marvel Science Stories – August 1951‘This Joe’ by A.E. Van Vogt

‘At No Extra Cost’ by Peter Phillips

Marvel Science Stories – November 1951

Marvel Science Stories – November 1951This issue also contains the article on The Hydra Club by Judith Merril with HH’s illustration – see previous post.

‘Chowhound’ by Mack Reynolds

‘The Most Dangerous Love’ by Philip Latham

‘The First Spacesuit’

Marvel Science Stories – May 1952

Marvel Science Stories – May 1952The issue also has artwork by Al Williamson and Roy Krenkel.

‘Star-Wife’ by Morton Klass

‘Brother’ by Frank Quattrochi

‘Who’s Zoo’ by L. Major Reynolds

Scanned from a photographic copy in Harry Harrison’s collectionGalaxy Science Fiction – May 1951

Scanned from a photographic copy in Harry Harrison’s collectionGalaxy Science Fiction – May 1951Galaxy Science Fiction was first published in October 1950, edited by H.L. Gold and initially published by World Editions, a French-Italian company. It was sold to a couple of different publishers over the years, its initial run ending in 1980. It was revived in 1994 and a further eight issues were published. As far as I’m aware, Harry Harrison only provided one illustration for the magazine, for the short story ‘Bridge Crossing’ by Dave Dryfoos in the May 1951 issue. The image below is taken from a scan of the magazine.

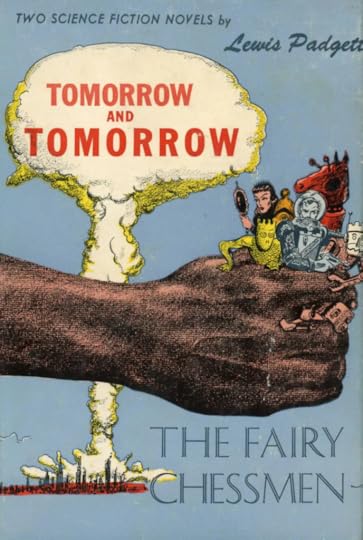

Gnome Press

Gnome PressI’ll include one more image here dating from the 1950-51 period, a jacket illustration by Harry Harrison for Tomorrow and Tomorrow and The Fairy Chessmen, by Lewis Padgett, published by Gnome Press in 1951. Padgett was a pseudonym of husband and wife writing team Henry Kuttner and C.L. Moore. Only 4,000 copies were printed.

Next: Harry the Artist Part 3: Unpublished and Unidentified Artwork

Paul Tomlinson is the author of over a dozen novels and books about writing genre fiction. www.paultomlinson.org

May 27, 2025

Harry Harrison Centenary – Part 8: Harry the Artist & The Hydra Club

In interviews and articles, you often get the impression that Harry Harrison’s transition from artist to writer was a linear one, that he went from drawing comics, to editing comics, to drawing for science fiction magazines, and finally to writing for magazines. But the actual chronology is much more complicated and there is a great deal of overlap. Harrison began writing for comics fairly early on, both scripting stories and writing two-page text fillers that comics had to contain. He even wrote letters columns, including an advice column in a romance comic.

When Harrison returned to New York after the Second World War, his social life seems to have centred on three main areas of interest. Having learned to correspond in Esperanto, he joined the Esperanto Association of North America, based in New York, and as a result learned how to speak the language. He was also a staff member on the American Esperantist Bulletin in 1948. I believe that it is through the association that he met his first wife, Evelyn. They married in 1949 – some sources say 1950.

His second group of friends were fellow artists at the Cartoonists & Illustrators School. And the final group were his friends in science fiction – both fans and professionals. As Harrison and others made the transition from fans to professionals, this caused some friction in the New York fan community. They were accused by at least one fellow fan of betraying their fannish roots.

The Hydra ClubA significant community of SF professionals in New York were members of the Hydra Club. The club was the idea of David Kyle and Frederik Pohl who discussed it on a train ride back from the first Philcon, an SF convention held in Philadelphia at the end of August 1947. Their friend Lester del Rey agreed that a club would be a great idea, and the first meeting took place in Pohl’s apartment on 25th October 1947. Kyle recalls that nine people were present and so the club named itself after the multi-headed mythological beast, the hydra.

David Kyle recalled the founding of the club in a piece titled ‘The Legendary Hydra Club’ published in the fanzine Mimosa #25 (April 2000) and now available online. Kyle lists Harry Harrison as being one of those who were ‘in at the beginning,’ though not one of the original nine. Membership of the club was by invitation only and had to be approved by the Permanent Membership Committee.

As a member of the Hydra Club, Harrison was known as ‘Harry the Artist.’ It’s likely that his friendships with other club members helped him get work illustrating SF magazines. Almost all of the magazine editors were members of the club.

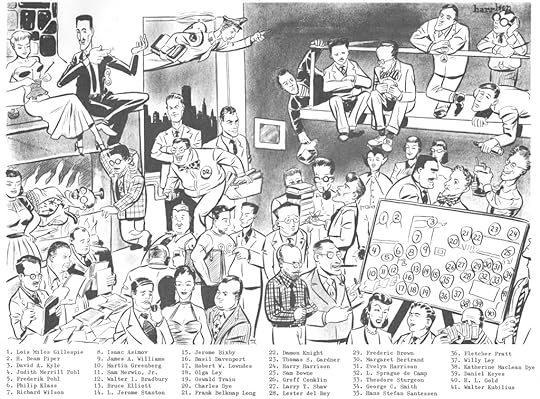

Hydra Club member Judith Merril wrote an article about the Hydra Club and it was published in the November 1951 issue of Marvel Science Fiction. It was accompanied by an illustration by Harry Harrison: it features caricatures of 41 club members, with a note saying that ‘the remaining twenty-odd members showed up too late at the meeting.’ The scanned image below is as it appeared in Graphic Story Magazine #15 (Summer 1973). Merril’s ‘The Hydra Club: An Organization of Professional Science-Fiction Writers, Artists and Editors’ can be found online in a couple of places. Frederik Pohl wrote a short blog post ‘About the Hydra Club’ in 2013 which reproduced Harrison’s illustration.

Evelyn Harrison

Evelyn HarrisonHarrison’s wife Evelyn also attended the club meetings, many of which were social gatherings. The only photographs of Evelyn Harrison that I’ve ever seen were taken by Jay Kay Klein at a Hydra Club meeting and at an SF convention. These images now belong to the University of California and can be viewed online here and here.

Harry Harrison and Evelyn divorced in, I think, 1951. Evelyn married Lester Del Rey in 1954. She was killed in an automobile accident in January 1970. Robert Silverberg and Judy-Lynn Benjamin (later Del Rey) wrote obituaries. Judy-Lynn described Evelyn (or ‘Evvie’) as “…only a relative of the science fiction family by marriage…” but it’s possible that she made a more concrete contribution, at least in the field of comics. In a 1950 census return, Harry Harrison’s occupation is listed as ‘commercial artist, cartoonist, and book illustrator.’ Evelyn is shown as ‘Freelance writer comic books.’ I’ve also seen a reference to Harry and Evelyn teaching at least one session on writing comic books. Harry Harrison always refused to talk about his first wife. When I asked him about her work on comic books, he said that she would type up some of his scripts and that sometimes they put her name on the front as writer because publishers were unhappy about someone being an artist and writer. It’s impossible to say whether Evelyn wrote any comic book scripts, but in light of the census return, I think it is possible.

In his memoir, In Joy Still Felt (1980), Isaac Asimov says that Evelyn was 44 years old when she died.

Harry the Artist – Part 1: Worlds BeyondHarry Harrison provided illustrations for science fiction magazines from late 1950 to early 1952. I don’t have a complete list of Harry Harrison’s contributions as an artist to the science fiction magazines. I found one or two sources online but they’re not complete either. Part of the problem is that artists weren’t always credited in the magazines, and they weren’t always permitted to sign their artwork.

In this post and the following one, I’m going to include all of the SF magazine artwork that I’m aware of. I scanned what I could from original artwork or from photographic copies in Harry Harrison’s files. Some of the latter were negative images, so I’ve flipped them back to positive. Where the artwork wasn’t in his files, I copied tear sheets he’d kept, and where those weren’t available, I’ve scanned old magazines or sought copies of magazines archived online.

The magazine Worlds Beyond was edited by Damon Knight – a Hydra Club member featured in Harrison’s illustration above – and lasted for only three issues. But it is significant in Harrison’s career. He provided illustrations for all three issues and his first published science fiction story appeared in the final issue.

While much of Harry Harrison’s comic art was, in his words, ‘desperate sh*t,’ he noted that Damon Knight encouraged him to produce some of his best artwork. This was subject matter he had an interest in and its clear he took some pride in it. The illustrations in Worlds Beyond were reproduced at a relatively small size – perhaps a quarter the width of the originals – next to the titles of stories. Harrison’s artwork was created using black ink and what appears to be a ‘crow quill’ pen.

I should note here that when I reproduced some of the Worlds Beyond illustrations in my fanzine, Harry Harrison expressed some concern that they appeared at a larger size than they had in the magazine – they were intended to be seen at the smaller size. The images reproduced here are even larger and much clearer – unless you’re reading this on your phone.

Worlds Beyond #1 (December 1950)

I’ll present the artwork here in the sequence it appeared in the magazine, identifying the story it illustrated and the source of the scan. Details are above each image. You can find scans of the whole magazine issues online, though I’m not sure of the copyright status of the contents. Search on Google for ‘Worlds Beyond’ plus the month and year.

The first issue features a cover by Paul Calle who also provided some interior illustrations.

‘Six-Legged Svengali’ by Mack Reynolds and Fredric Brown. Scanned from a photographic copy of the original artwork kept by Harry Harrison.

‘Simworthy’s Circus’ by Larry Shaw. Scanned from the original artwork.

‘The End of the Party’ by Graham Greene. Scanned from a photographic copy of the original artwork from the files of Harry Harrison.

‘The Hunter Gracchus’ by Franz Kafka. Scanned from the original artwork. There are two versions of this illustration in HH’s portfolio – this is the version that was used in the magazine.

‘The Mindworm’ by C.M. Kornbluth, scanned from the original artwork.

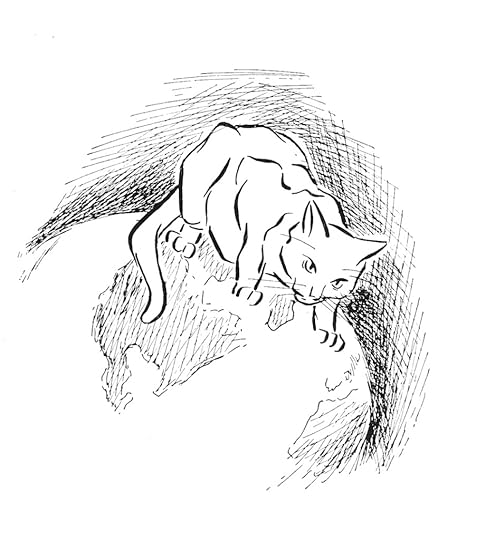

‘The Smile of the Sphinx’ by William F. Temple. Scanned from a photographic copy of the original artwork from the files of Harry Harrison. This story carries the following tagline: What do cats do in their spare time? … Rule the world, perhaps?

‘Invasion Squad’ by Battell Loomis. Scanned from a photographic copy of the original artwork from the HH’s files.

‘Wow’ by William Seabrook. This artwork was missing from Harry Harrison’s file – I have taken the image from a scan of the magazine.

‘The Loom of Darkness’ by Jack Vance. Scanned from a photographic copy of the original artwork from the Harry Harrison’s files.

Worlds Beyond #2 (January 1951)

The cover for this issue is by Henry Richard van Dongen (1920-2010) and interior illustrations are by Harry Harrison, Jannace, and Napoli. ‘Napoli’ is, I believe, James Vincent Napoli (1907-1981) who also illustrated Weird Tales. I haven’t been able to find any information about ‘Jannace’ – if you know who this was, please leave a comment on this post or e-mail me.

‘The Green Cat’ by Cleve Cartmill. This artwork was missing from Harry Harrison’s file – I have taken the image from a scan of the magazine.

‘The Fittest’ by Katherine MacLean. Scanned from the original artwork. MacLean was also a member of the Hydra Club – she and Harry Harrison would go on to collaborate on a novella published in 1953.

Only two Harry Harrison illustrations are included in the second issue of World Beyond.

Worlds Beyond #3 (February 1951)

The cover for this issue is by Henry Richard van Dongen and interior illustrations are by Harry Harrison, Jannace, and Napoli. Harrison’s first published science fiction story, ‘Rock Diver,’ appears in this issue. Artist credits are not given for individual illustrations and I didn’t find any copies of the artwork from this issue in Harry Harrison’s files – this may be why he has stated in interviews that he didn’t illustrate the third issue. It’s possible that Harrison provided illustrations without knowing in which issue a particular story would appear.

Identifying the artist of individual illustrations is tricky, particularly given the small size at which images were reproduced. What follows is my best guess. Have a look at online scans of the magazine and let me know your opinion.

When I asked Damon Knight to contribute to a 75th birthday tribute to Harry Harrison, this was his opening paragraph: “I first met Harry Harrison in New York about forty years ago. He was an illustrator then; later he became a writer and an editor. I was an illustrator, writer and editor, and Harry bought my stories and I bought his. I bought his illustrations, too, but he never bought mine, the skunk.”

I quote this because I wasn’t aware that Damon Knight was an illustrator. It’s possible that he created one or more illustrations for Worlds Beyond and didn’t credit himself on the contents page. This would further complicate things. I’m going to proceed on the assumption that only the three credited artists illustrated issue three of the magazine, but wanted to add this caveat. All of the images below are taken from scans of the magazine.

The illustration for Lester del Rey’s ‘The Deadliest Female’ is in a distinct style that I think may be ‘Jannace.’ H.B. Hickey’s ‘Like a Bird, Like a Fish,’ C.M. Kornbluth’s ‘The Rocket of 1955,’ and Harry Harrison’s ‘Rock Diver’ were all, I think, illustrated by Napoli. The images below may all be by Harry Harrison, but as I say, I cannot be certain. I’ve included the story titles as captions below the images.

‘Brain of the Galaxy’ by Jack Vance

‘Brain of the Galaxy’ by Jack Vance

‘The Old Brown Coat’ by Lord Dunsany

‘The Old Brown Coat’ by Lord Dunsany

‘The Acolytes’ by Poul Anderson

‘The Acolytes’ by Poul Anderson

‘Forgotten Tongue’ by Walter C. Davies

‘Forgotten Tongue’ by Walter C. Davies

‘Clothes Make the Man’ by Richard Matheson

‘Clothes Make the Man’ by Richard Matheson

‘Valley of Doom’ by Halliday Sutherland

‘Valley of Doom’ by Halliday SutherlandHarry Harrison drew Damon Knight for his book review column ‘The Dissecting Table’ when it ran in the magazine Science Fiction Adventures. The review column in Worlds Beyond carried the same title but didn’t use the image. The image below is taken from a scan of the magazine.

Damon Knight by Harry Harrison from Science Fiction Adventures (May 1954)

Damon Knight by Harry Harrison from Science Fiction Adventures (May 1954)In answer to my interview questions in 1984, Harry Harrison said this about ‘Rock Diver,’ his first SF story: “I was doing small illustrations for Worlds Beyond, but I got ‘flu and an infected throat, and I couldn’t draw … I typed a story out and asked Damon what to do with it, and he bought it for $100. My agent then was Fred Pohl, and Fred anthologised it, and I got another $100. So I did very well with my first story: I haven’t done that well with a single story since, I’ll tell you!”

Damon Knight wrote a paragraph on each writer who contributed to Worlds Beyond. About Harry Harrison, he said this: “Harry Harrison is a commercial artist whose interest in science-fantasy has until recently been entirely unselfish. He speaks fluent Esperanto and fair English, and is a mainstay of the Hydra Club in New York.”

Next: Harry the Artist Part 2: Marvel Science Stories & Galaxy

Paul Tomlinson is the author of over a dozen novels and books about writing genre fiction. www.paultomlinson.org

May 5, 2025

Harry Harrison Centenary – Part 7: The Comic Book Years 5 – Packaging Comics

Harry Harrison was a comics artist and writer until mid-to-late 1953 or thereabouts when he began packaging comics – taking responsibility for putting together whole issues of a comic book for a publisher. He worked as a comics packager until late 1955 or early 1956.

When I interviewed Harry Harrison in September 2010, he explained how it worked: “If you had a Kable contract – Kable was a distributer, and if you had a contract from them, you were a publisher. I used to work for a crooked lawyer packaging comics, and he’d be the publisher and I was the editor.”

Initially, Harrison was packaging comics for William ‘Billy’ Friedman, who was, in Harrison’s words, a ‘decent lawyer … who was packaging comics.’ Friedman’s brother-in-law was Lou Stricoff, who Harrison jokingly referred to as “…a fat crook bastard.” It seems that Stricoff took over some or all of Friedman’s comics business. Friedman “…turned me over to this guy,” Harrison said.

“He had a Kable contract, so what you’d do… he would lay out – which was not very much – editorial costs. I had my own studio, and editorial costs were just the production, which I did myself. Getting the cover, getting scripts for the stories, hiring artists to draw them … nobody got paid, they didn’t usually pay for two or three months. And when you had the comic complete, you turned it in to Kable.”

I think that Harrison’s studio at this point was an office on 46th Street in New York.

Writing in Great Balls of Fire (1977), Harrison said: “Many comic publishers were just black paint on an office door. If you had a distributor’s contract you were a publisher; it was as simple as that. For a few grand you could bring excitement into the lives of thousands. With the contract you got an engraver and a printer, because the distributor guaranteed to pay both these bills when the magazines were delivered. The least important thing was producing the magazine itself. This particular function was farmed out.”

Harrison also spoke about this in an interview for Graphic Story Magazine with Bill Spicer and Pete Serniuk. “The distributor paid the printer’s bill. So all you had to do was lay out a thirty-two page magazine at twenty-five dollars a page, a thousand bucks of your own cash, and you could be a package publisher.” And: “I edited, wrote what I could, drew and inked some of it.”

In Great Balls of Fire, Harrison said that he made $100 per issue on the comics as the editor. He would make more if he wrote or illustrated some of the content or did the cover.

Unpicking the comic book businesses that Harrison, Stricoff and Friedman were involved in isn’t straightforward, as the ‘publisher’ changed name a number of times. The Grand Comics Database entry for ‘Story Comics’ suggests that the outfit with Billy Friedman in charge was also known variously as Master Publications, Merit Publications, and Premier Magazines.

I think Harry Harrison created artwork for comics published by these companies, and the publisher Ribage which also seems to be connected. When it comes to packaging comics, most – if not all – of the titles he was involved with were for Premier Magazines, and these are reasonably well documented. In the Graphic Story Magazine interview, when talking about packaging, Harrison mentions the one-off comic Captain Rocket and True Stories of Stamps. Captain Rocket was a November 1951 comic, published before Harrison began packaging comics, so I think he’s misremembering the title. The stamps comic he’s referring to is, I think, Thrilling Adventures in Stamps (1951-1952), which he provided artwork and scripts for, but I think this again predates his work packaging comics. I may be wrong. Harrison certainly provided covers and the title/logo for the cover.

The Premier Magazines titles that Harry Harrison packaged are:

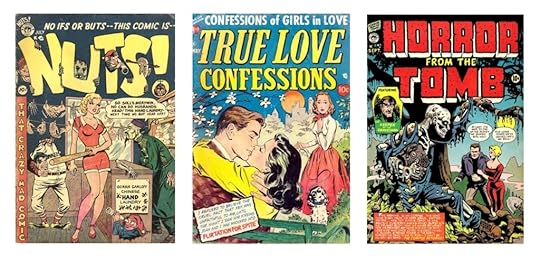

Masked Ranger – a Lone Ranger lookalike, running for nine issues from 1954 to 1955Mysterious Stories – a horror/weird comic, six issues 1954–1955Police Against Crime – a crime title, eleven issues 1954-1955True Love Confessions – romance, eleven issues 1954-1956Nuts! – humour, HH refers to it as ‘an imitation Mad.’ Five issues in 1954The earliest of Premier Magazine’s titles was a single issue of Animal Fun 3-D in 1953: Harry Harrison may not have been involved with that one. It featured characters called Ziggy Pig, Sally Seal, Billy and Buggy Bear, and Buzzy the Mouse and was printed in red and blue, with glasses included to allow viewing of the 3D effect.

Another Premier one-shot was Horror from the Tomb, with a cover date of September 1954. According to the Grand Comics Database, “…it was killed by the distributor’s (Kable News) President, George B. Davis, after he saw the issue.” When Davis gave testimony to the Senate Subcommittee Hearings into Juvenile Delinquency in June 1954, he referred to the comic as ‘Tomb Horror.’

Horror from the Tomb was replaced by Mysterious Stories, the first issue of that title being #2. From the Premier Magazine titles, Nuts! is the one that Harrison recalled most fondly.

Captain Marble Flies Again!Harry Harrison met science fiction author Otto Binder at the Hydra Club (more on this club in the next post) in New York. Binder had been writing comics since 1939 and was working on Captain Marvel (aka Shazam!) for Fawcett Publications. “When I started Nuts! I told him about it. He’d been writing Captain Marvel for 800 years … so he wrote a parody of his own work, called Captain Marble! It was funnier than shit! I got a good artist to draw it too. I had some good artists, but mostly I had very bad artists…”

The Grand Comics Database shows that the six-page story ‘Captain Marble Flies Again’ in Nuts! #5 (November 1954) was pencilled by Ross Andru and inked by Mike Esposito. Harrison knew both artists from the Cartoonists & Illustrators School.

Andru and Esposito published their own humorous comic book, Get Lost, which ran for three issues, March, April-May, and June-July 1954. Harry Harrison wrote a three-page article, ‘How to Make Your Own Comic Book!!’ – published under the name ‘Robsjon Gluck (Top-Notch, Star Comic Artist)’ for the second issue. It includes examples of script and comic book panels, satirising comic book art and writing.

Police Against CrimeThere weren’t many scripts in Harry Harrison’s files from this period, so it is difficult to know which comics stories he wrote. I did find a first draft script for a story called ‘.45 Bullet’ which appeared in Police Against Crime #3 (August 1954). I’ve included a scan of the typewritten script here along with the finished story, from a scan of the comic I found online.

45-BulletDownload45Bullet-ArtDownloadThe Comic Book CodeThe Comics Code Authority was established towards the end of 1954 with a New York magistrate, Charles F. Murphy, heading the organisation. It was set up as a result of public concerns concerning the depiction of sex and violence in comic books. Adherence to the ‘code of ethics and standards’ supervised by Murphy was entirely voluntary, a form of self-regulation designed to avoid the need for formal government regulation of comic book content. Large, well-established publishers could continue without subscribing to the Code, but smaller outfits – like the one Harry Harrison packaged comics for – had to follow the code if they wanted to be sure of getting their comics distributed.

Comics had to be submitted to the CCA who would then rule on their compliance to the Code. If a comic passed the test, it could carry a small logo on the cover – ‘Approved by the Comics Code Authority.’

Harrison recalled the practical implications of this in the Graphic Story Magazine interview: “…they had a lot of decayed old virgins going over the art panel by panel. When the pages came back we’d be armed with a tube of white and bottle of ink, flattening the girls’ chests down. We had to do ridiculous revisions, really heavy-handed nonsense.”

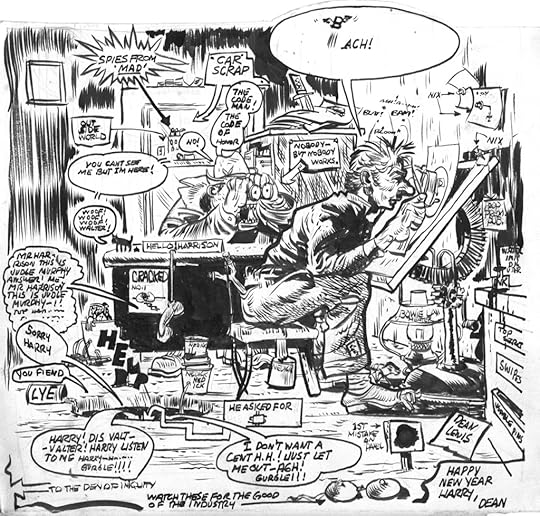

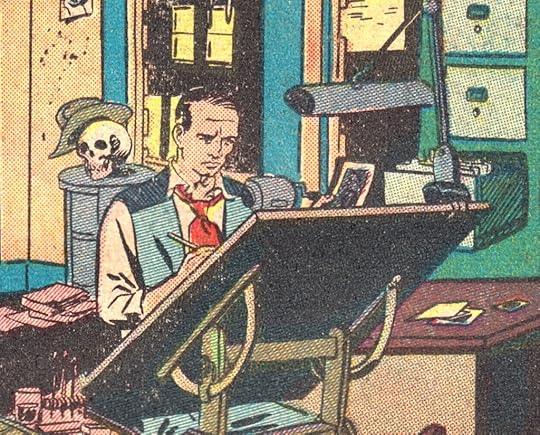

I found the illustration below in Harry’s portfolio. I’m not sure when – or if – it was published. It contains lots of comics in-jokes, including a reference to Judge Murphy. The fact that there is an image of Cracked on Harry’s desk seems to suggest it was from 1958 (when Cracked Mazagine was first published) or later. I think the artist signature is ‘Dean Lewis’ but I’m not familiar with the name – if you know who he was, please leave a comment on this post.

A combination of the ‘moral panic’ around horror and violence in comics and the rise of television as a form of entertainment in the home, meant that the popularity of comic books waned. The ‘Golden Age of Comics’ is said to have come to an end in 1956. This more or less coincided with Harry Harrison’s decision to leave the comic book business. As he told Bill Spicer and Pete Serniuk, “When comics went under I was already writing and editing, so I slipped sideways into editing and writing for science fiction magazines.” As we’ll see in the next few posts, Harry Harrison’s transition from comics artist to science fiction writer wasn’t as simple as he makes it sound.

Next: The Hydra Club and Harry the Artist

Paul Tomlinson is the author of over a dozen novels and books about writing genre fiction. www.paultomlinson.org

April 18, 2025

Harry Harrison Centenary – Part 6: The Comic Book Years 4 – Ernie Bache & Warren Broderick

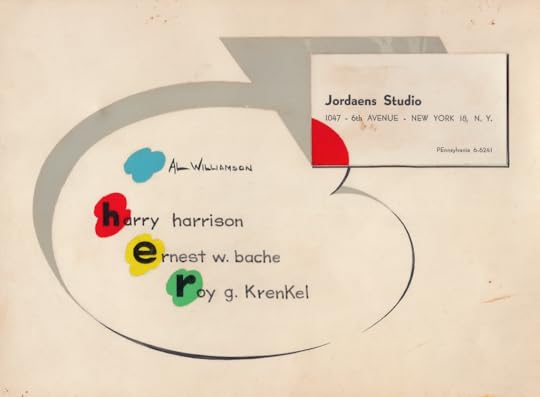

Following his split with Wally Wood, Harrison had to find a new space to work from. In an interview with Bill Spicer and Pete Serniuk, published in Graphic Story Magazine, Harrison said: “I had my own studio at one point, a loft on Sixth Avenue. Ernie Bache, Roy Krenkel, Al Williamson, and part of the time Frank Frazetta, a lot of guys came through the office, mid-town drunks, everyone! Ernie, Roy and I did a lot of comics together. Roy and I did some science fiction illustrations, book jackets, magazine illustrations, advertising.”

I found this layout from that period in Harry’s portfolio:

Harrison, Williamson, Bache & Krenkel studio cardErnie Bache

Harrison, Williamson, Bache & Krenkel studio cardErnie BacheErnest William Bache was born 22nd October 1922. He attended the Cartoonists & Illustrators School, where he was editor of The Cartoonists & Illustrators Billboard. Harry Harrison is listed as one of the ‘staff assistants’ on the monthly magazine that was published by the school’s Student Society.

The first collaboration with Ernie Bache that I found in Harry Harrison’s files was the story ‘The Steel Monster,’ in the May 1951 issue of Amazing Adventures (#2). There are a couple of ‘sneaks’ in the artwork – ‘BH Contractors’ appears in the splash panel and ‘BH’ again appears on page five. Harrison identified the pencils as being done by Bache – “…all perspectives I never used…” with him doing the inking and the title lettering for the splash panel. The script borrows heavily from Theodore Sturgeon’s novella ‘Killdozer!’ (1944) which was the basis for the 1974 TV movie.

Splash panel of ‘The Steel Monster’ from Amazing Adventures #2

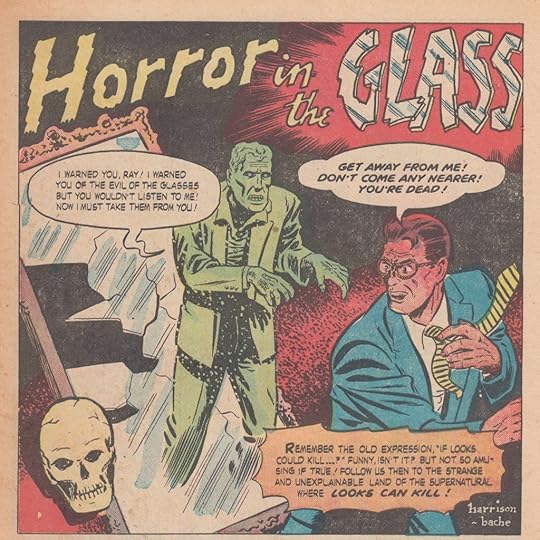

Splash panel of ‘The Steel Monster’ from Amazing Adventures #2The Dec 1951-Jan 1952 issue of Dark Mysteries (#4) has the story ‘Horror in the Glass’ with the splash panel signed Harrison-Bache. Harrison said that this story was from a later period when his inking was much tighter. This was one of two titles put out by the publisher Master Comics, the other being Romantic Hearts, which Harrison-Bache also did signed work for. Reviewing the artwork for ‘My Fight for My Lover’ in issue eight, Harrison said he was inking over Ernie Bache’s pencils and that this was “desperate sh*t!”

Splash panel for ‘Horror in the Glass’ from Dark Mysteries #4

Splash panel for ‘Horror in the Glass’ from Dark Mysteries #4The pair also did signed artwork for ‘Mel Torme Dr. of Love’ in Youthful Romances (#10), January 1952, and ‘Cold Cold Heart’ – featuring singer Tony Bennett! – in issue twelve dated June 1952. And for the May 1952 issue of Youthful Hearts (#1), their art for ‘Cherchez la Femme’ featured Frankie Laine.

In the horror genre, they did several stories for publisher Lou Strickoff. Strickoff liked comic art that featured skulls and Harrison would always take along some additional drawings so more skulls could be pasted on if requested.

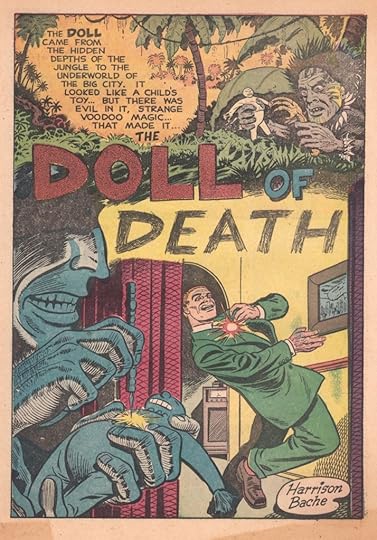

The June 1952 issue of Beware (#10) has signed art by Harrison-Bache for the story ‘The Doll of Death.’

Splash page for ‘The Doll of Death’ from Beware #10

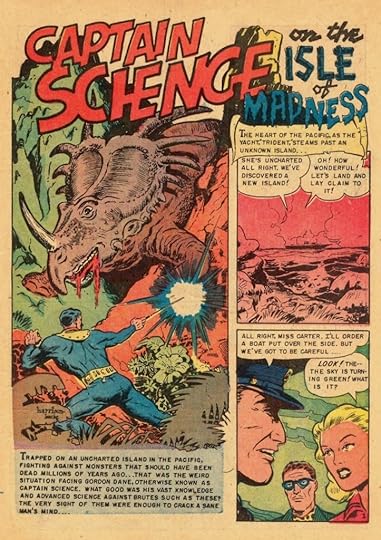

Splash page for ‘The Doll of Death’ from Beware #10 For Fantastic #8 (February 1952), the first page of the story ‘Captain Science on the Isle of Madness’ is signed Harrison-Bache. And in #9, dated April 1952, the two provided art for ‘Queen of the Shrunken Heads.’

Artwork by Harrison-Bache for ‘Captain Science on the Isle of Madness’ in Fantastic #8

Artwork by Harrison-Bache for ‘Captain Science on the Isle of Madness’ in Fantastic #8 One of the more bizarre titles Harrison and Bache worked on was the comic Thrilling Adventures in Stamps, featuring stories inspired by the illustrations on postage stamps. The February 1952 issue has a four-page story about Iwo Jima, with Harrison also providing the cover. The June 1952 issue has a three-page story, ‘Disaster!,’ about the Hindenburg, again with a HH cover.

Cover image for Thrilling Adventures in Stamps #5, pencils and inks by HH. Splash panel pencils by Ernie Bache and inks by Harry Harrison

Cover image for Thrilling Adventures in Stamps #5, pencils and inks by HH. Splash panel pencils by Ernie Bache and inks by Harry HarrisonFor the comic ‘Attack!’ (#1), dated May 1952, Harrison and Bache signed the front cover art and the story ‘Battle Report – Iwo Jima.’ The art for ‘Death of a Soldier’ in the July 1952 issue (#2) is also signed.

Cover and splash page for ‘Battle Report – Iwo Jima’ in Attack! #1, signed ‘HB’ and ‘Harrison-Bache’

Cover and splash page for ‘Battle Report – Iwo Jima’ in Attack! #1, signed ‘HB’ and ‘Harrison-Bache’The Harrison-Bache partnership seems to have ended sometime during 1952. According to the Grand Comics Database, Bache went on to assist Dick Ayers (who had also attended the Cartoonists and Illustrators School) between 1952 and 1954 at Timely/Atlas (later Marvel Comics). He worked as an inker on Atlas titles including Battlefront, Battleground and War Comics. He continued working on comics into the 1960s.

Ernie Bache died in August 1968.

Working with a Breakdown GuyAfter his partnership with Ernie Bache ended, probably towards the end of 1952, Harry Harrison began working as a comic book ‘packager’ – putting together whole issues of comic books for a publisher. This meant hiring writers and artists – and paying his own salary as editor – from a budget set by the publisher. One way to keep costs down was to ink some of the stories himself. And rather than paying another artist to draw the pencils, he hired someone to produce pencil page breakdowns – laying out the panels and sketching in rough details – which Harrison would then ‘draw’ as he was inking. The price paid for a finished page of comic book art was somewhere between $25 and $35, depending on the publisher.

Harrison recalled that “…half that – or maybe less than half – went to the penciller. But I found that for $8 a page, I could get a breakdown guy who would do a fairly rough outline of the page. And then I’d go through with a 4H pencil and tighten up the hands and faces, and then I’d ink the thing. And make most of the money myself!”

When I interviewed him about his comics work, Harry couldn’t remember the name of the artist he worked with, referring to him only as ‘the breakdown guy.’ He worked with this artist on many of the comics he was packaging.

When Harry and I went through the tear sheets in his files, he was able to identify a number of stories as being drawn in collaboration with the ‘breakdown guy.’ One factor that he used to identify them was the shape of the panels – “I never laid out tall thin panels.”

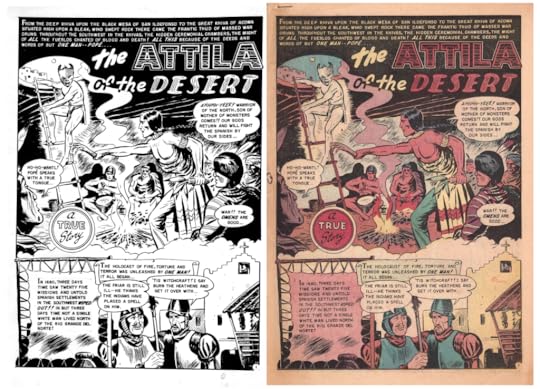

Original black and white artwork and tear sheet from the finished comic. ‘The Attila of the Desert’ from Redskin #6, April 1952

Original black and white artwork and tear sheet from the finished comic. ‘The Attila of the Desert’ from Redskin #6, April 1952An early example that Harrison identified as a possible collaboration with the ‘breakdown guy’ was for the story ‘The Attila of the Desert’ in Redskin #9, dated April 1952. More certain are those stories from late 1952 and into 1953. There is ‘Sea of Ghosts’ in Dark Mysteries #10 (Dec 1952-Jan 1953); ‘Medal from Korea’ in Attack! #5 (January 1953); and ‘The Vultures of Doom’ in Mysterious Adventures #12 (February 1953). Other possible collaborations include ‘My Guilty Heart’ in Daring Confessions #6 (March 1953), and ‘The Ancient Mariner’ in Chilling Tales #14 (February 1953) which is signed ‘Hh’ but also features some layouts with tall, thin panels. Of the work he did over these pencil layouts, Harrison said: “By that time I was doing most of my drawing with a brush… I did a page in about an hour.”

Warren BroderickWarren Hugh Broderick was born in February 1923 in New York. Like Harry Harrison, he attended the Cartoonists & Illustrators School courtesy of the G.I. Bill of Rights (Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944). Broderick began working for comics publishers from late 1947 or early 1948. Comics historian Ken Quattro published an article ‘The Search for Warren Broderick’ in 2020, including some examples of Broderick’s signed artwork. It also has what may be the only surviving photograph of the artist.

The Search for Warren Broderick

When I interviewed him, Harry Harrison recalled that Warren Broderick was “…a very nice guy. He was a very shy guy too, like Wally. He didn’t want to go out and face white editors. I can bullsh*t and I can front for these people. We partnered, working very well. He was a great penciller, so I got the jobs and gave them to him to pencil. I ended up with him as the last guy who did pencilling for me – better than the breakdown guy.”

Also in the same interview, Harry said: “He actually took me home once: I met his father who was a classic railroad porter. A little middle-class family. That was when I got to know a black family really for the first time. I met him, knew his friends. I used that later for the hero in Rebel in Time.”

I’m not clear from the interview comments, or those made elsewhere, whether Harrison worked with Warren Broderick before or after he worked with the ‘breakdown guy.’ This makes it difficult to identify any artwork that the two collaborated on.

Harry Mendryk discusses Warren Broderick’s work with Jack Kirby on the Jack Kirby Museum website in a post titled ‘Forgotten Artists.’

It’s A Crime, Chapter 6, Forgotten Artists

A list of Broderick’s artwork for Atlas comics can be found on the Atlas Tales website.

A list of can also be found on the Grand Comics Database.

When I spoke to Harry Harrison about Warren Broderick, he said: “When I got out of comics, he got out too, and he ended up being an ambulance driver for a hospital. I’d see him once in a while, but we were in different circles by then. Then we [Harrison and his family] went to Mexico.”

Warren Broderick eventually moved to San Bernardino, California where he died in 1996.

Next: Crooks & Comic Packaging

Paul Tomlinson is the author of over a dozen novels and books about writing genre fiction. www.paultomlinson.org

April 8, 2025

Harry Harrison Centenary – Part 5: The Comic Book Years 2 – EC Comics

EC Comics began in 1944 as Educational Comics, but William Gaines – the son of its founder – took the company in a different direction, renaming it Entertaining Comics in 1947.

Harry Harrison and Wally Wood had been creating artwork for lower paying markets. According to Joe Orlando, who worked with both men, Harrison was the better salesman, and it was probably him that persuaded William Gaines to give them work.

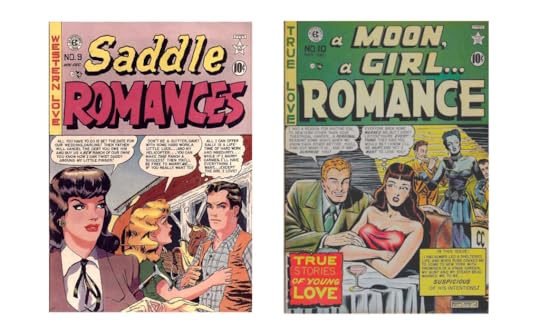

Covers from the EC Comics Saddle Romances #9 and A Moon, A Girl… Romance #10

Covers from the EC Comics Saddle Romances #9 and A Moon, A Girl… Romance #10Harry Harrison is believed to have pencilled and inked the story ‘An Indian Love Call,’ in Saddle Romances #9. A Moon, A Girl… Romance #10 has ‘I Thought I Loved My Boss,’ with pencils by Harrison and inks by Wally Wood – it is signed ‘Harry Wood.’ The art appeared in the November-December 1949 issues of the two comics. Harrison and Wood were still illustrating romances, but EC Comics was paying in the middle range – perhaps $25 or $28 per page with no kickbacks required and no agent’s commission.

If the title A Moon, A Girl… Romance seems an odd one, it is because it was a ‘continuation,’ following a comic called Moon Girl.

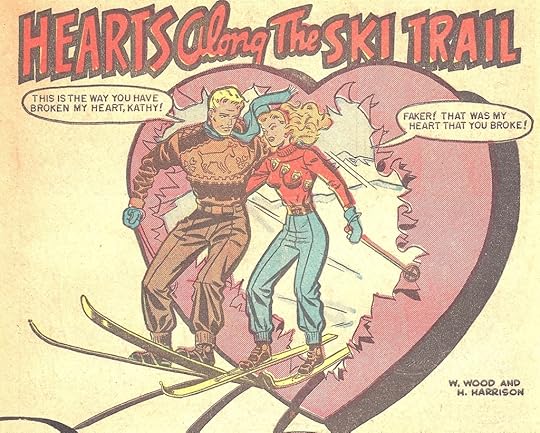

Splash panel from ‘Hearts Along the Ski Trail’ in A Moon, A Girl… Romance #11 (Jan-Feb 1950), signed W. Wood and H. Harrison

Splash panel from ‘Hearts Along the Ski Trail’ in A Moon, A Girl… Romance #11 (Jan-Feb 1950), signed W. Wood and H. HarrisonThe studio space that Harrison, Wood, and a number of other artists worked in was a big space on the floor under the apartment that Wally, his brother, and mother were living in. It was at West 64th Street, where the Lincoln Center now stands.

“We had guys dropping in all the time, we were very sociable,” Harrison recalled in a 2010 interview. Most of the guys were people he and Wally knew from the Cartoonists & Illustrators School. “We’d have a life class once a week, and other guys would come in and contribute fifty cents for the model. We had a factory going there and had to take on three or four more guys when we got a bigger contract assignment.” In the same interview, he said: “We had Roy Krenkel working with us, who was very slow and meticulous. He’d use a crow-quill pen … For a baseball game, one panel would be bleachers and he’d draw every f**king head!”

A self-portrait of Wally Wood – detail from a panel in ‘Dream of Doom’ from Weird Science #12 (May-June 1950)

A self-portrait of Wally Wood – detail from a panel in ‘Dream of Doom’ from Weird Science #12 (May-June 1950)Talking to Bill Spicer and Pete Serniuk, Harrison said that he and Wally Wood “…worked together because neither of us could hack it alone. We were a complete team … In the beginning, I think he pencilled and I inked. Then he got very good with inking and did the heads and hands. He’d break down the pages very tight with the figures, and we’d pass the pages back and forth, each handling certain kinds of swipes.”

‘Playtime Cowgirl’ from Saddle Romances #11 (March-April 1950)

‘Playtime Cowgirl’ from Saddle Romances #11 (March-April 1950)A comic art swipe – or ‘homage’ – according to Wikipedia, is the “…intentional copying of a cover, panel, or page from an earlier comic book or graphic novel without crediting the original artist.”

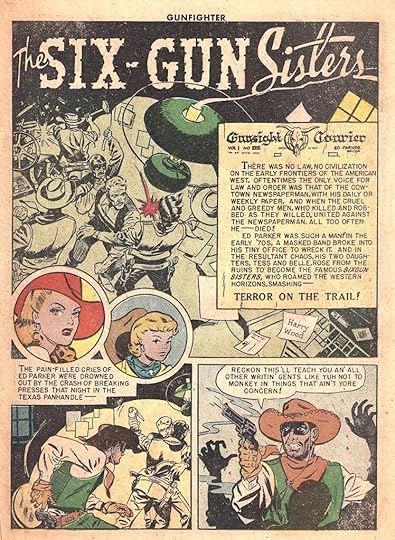

‘The Six-Gun Sisters’ from Gunfighter #13 (Jan-Feb 1950), signed ‘Harry Wood’EC Comics ‘New Trend’ – Horror & Science Fiction

‘The Six-Gun Sisters’ from Gunfighter #13 (Jan-Feb 1950), signed ‘Harry Wood’EC Comics ‘New Trend’ – Horror & Science FictionBy early 1950, the popularity of romance comics began to wane. In April-May 1950, EC Comics published the first of several titles that would establish them as publishers of horror comics. The Vault of Horror #12 – continuing the numbering from War Against Crime – featured the story ‘The Werewolf Legend,’ written by Gardner Fox with art by Harry Harrison and Wally Wood.

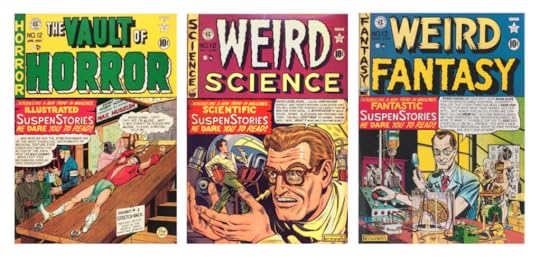

Covers for the EC comics The Vault of Horror #12, Weird Science #12, and Weird Fantasy #13

Covers for the EC comics The Vault of Horror #12, Weird Science #12, and Weird Fantasy #13Harrison and Wood were both long-time science fiction fans. They wanted to draw SF comics. According to Harry Harrison, they eventually managed to persuade Bill Gaines to launch a science fiction title. Sort of. Weird Science (#12) launched with a May-June 1950 issue, and Weird Fantasy (#13) came out at the same time. These comics replaced, and continued the numbering, of Saddle Romances and A Moon, A Girl… Romance. Harrison and Wood contributed artwork to both of the weird titles, with Harrison also writing some of the scripts. Wally Wood also did some plotting and probably scripted some stories, though the two never collaborated on the writing.

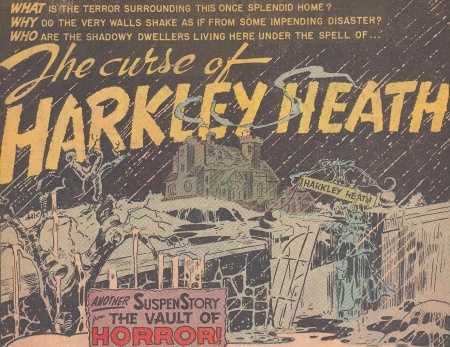

Splash panel from ‘The Curse of Harkley Heath’ in Vault of Horror #13 (June-July 1950). Pencils by Harry Harrison and inks by Wally Wood. Script by Harrison, possibly in collaboration with his first wife, Evelyn.The Harrison–Wood Break-up

Splash panel from ‘The Curse of Harkley Heath’ in Vault of Horror #13 (June-July 1950). Pencils by Harry Harrison and inks by Wally Wood. Script by Harrison, possibly in collaboration with his first wife, Evelyn.The Harrison–Wood Break-upThere was some tension in the studio that Harry Harrison and Wally Wood shared. “We got into a lot of fights,” Harrison recalled. “We all had big egos in comics.” He admitted that both he and Wood were ‘very hard to work with.’ Harrison said that some of the other guys called him ‘Old Snarly.’

Wally Wood began working more closely with Joe Orlando. And the science fiction comics allowed Wood to produce artwork that he enjoyed doing and was proud of. There were other changes in Wood’s life. He had met Tatjana Weintraub towards the end of 1949 and they married in August 1950. In 1951, the couple moved to an apartment in Rego Park and the studio on West 64th Street was closed.

“Wally and I split up,” Harry Harrison told me. “We’d been growing apart for a while, but I remember exactly the exchange that did it. Wally held up something he’d just finished…”

Wally: Hey, this is good, isn’t it?

Harry: Sure, Wally.

Wally: No, look, this is good.

Harry: Yeah, yeah…

Wally: But Harry, look, this is good.

Harry: It was better the first time when Milt Caniff did it.

The last Harrison-Wood collaboration appeared in the July-August 1950 issues of Weird Fantasy and Weird Science.

After the split, Harrison kept the EC Comics contract. Briefly. He was friends with Jules Feiffer, a young artist and writer who had worked with Will Eisner on The Spirit, starting when he was just seventeen years old. Harry Harrison has said that Feiffer had ambitions to be a comics artist in his own right. He may have pencilled the story ‘Only Time Will Tell’ in the May-June 1950 issue of Weird Fantasy, with the inks being done by Harrison and Wood.

The Vault of Horror #14, dated August-September 1950, carried a story titled ‘Werewolf,’ which may have been scripted by Jules Feiffer. Harrison has said of this story: “Very famous. Bill Gaines fired me right after this.” He has said on several occasions that he inked the artwork and Feiffer pencilled it. Feiffer, who went on to have a successful career as a cartoonist and author, claimed to have no memory of this.

“He wasn’t a very good penciller for the kind of thing EC was doing in their horror books, and without Wally, I wasn’t a very good inker,” Harrison told Spicer and Serniuk. “I lost the account.”

Wally Wood eventually returned to EC. He went on to become a celebrated artist and cartoonist, working on – among many other things – MAD Magazine, launched by EC in 1952, and the Topps trading cards that inspired the Mars Attacks movie.

Fredric Wertham’s Seduction of the InnocentIn 1953, the United States Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency was established to investigate the problem of juvenile delinquency. The psychiatrist Fredric Wertham had taken an interest in the effects of comic books on the development of children. In 1954, he published Seduction of the Innocent, in which he argued that crime and horror comic books were a significant cause of juvenile delinquency. This attracted a great deal of publicity and gained the attention of the subcommittee. In April and June 1954, public hearings took place, with Wertham and EC Comics publisher William Gaines being among those appearing.

The public outcry over these comics led to them effectively disappearing from the shelves. The Comics Code was brought in to ensure that the content of comic books was decent and wholesome. And by the end of 1956, EC Comics was publishing only MAD Magazine. The Golden Age of Comics, which had begun with the first appearance of Superman in Action Comics #1 in 1938, was over.

Harry Harrison’s work on that final EC werewolf story is often taken to define his work as a comic book artist. People have said that without Wally Wood, he was no good – and one has even implied that he was Wood’s assistant when they worked together. The latter is clearly untrue because Harrison pencilled and inked a number of solo projects and continued drawing comics after he split with Wally Wood.