Lona Manning's Blog

November 18, 2025

CMP#235 Four volumes of sheer tedium

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Spoilers abound in my discussion of these forgotten novels, and I discuss 18th-century attitudes which I do not necessarily endorse. CMP#235 Medieval Snoozefest -- The Duke of Clarence (1795), by Mrs. E.M. Foster

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Spoilers abound in my discussion of these forgotten novels, and I discuss 18th-century attitudes which I do not necessarily endorse. CMP#235 Medieval Snoozefest -- The Duke of Clarence (1795), by Mrs. E.M. Foster

What a snoozer! Chatgpt art Boy, what a slog. Frankly, I skimmed through most of this book. I had assumed that The Duke of Clarence was an historical novel but as it turns out, it’s a gothic novel set in England and France in the 15th century. Gothic novels aren’t my thing. I just can’t get excited about abducted and immured heroines, evil priests, secret passages, dastardly noblemen, and garrulous servants. So I confess—I didn’t catch every little detail explaining how and why our nobly-born hero Edgar De Montford ended up being mislaid and becoming a foundling.

What a snoozer! Chatgpt art Boy, what a slog. Frankly, I skimmed through most of this book. I had assumed that The Duke of Clarence was an historical novel but as it turns out, it’s a gothic novel set in England and France in the 15th century. Gothic novels aren’t my thing. I just can’t get excited about abducted and immured heroines, evil priests, secret passages, dastardly noblemen, and garrulous servants. So I confess—I didn’t catch every little detail explaining how and why our nobly-born hero Edgar De Montford ended up being mislaid and becoming a foundling.But the never-ending backstories with their thwarted love affairs and general perfidy--I mean, if you were a noblewoman unjustly immured in a tower for sixteen years and out of nowhere, two different people find you—coincidentally on the same night—and they asked you, Oh my god, what happened? Who put you here? would you give them a brief precis as you were running through the door to freedom, and maybe get into the details later after you've had a hot bath and a good meal? Or would you spend hours telling them the whole story from the beginning, recalling entire conversations and your every gesture with it? I’d be high-tailing it out of there.

As bad as this book is, I will say in justice to this authoress, and in contrast with Eliza Kirkham Mathews' youthful effort The Phantom, the backstories at least all tie together and relate to the central mystery of the story.

Joan of Arc So, in terms of my project of reading novels that were perhaps written by the same person who wrote The Woman of Colour, I have decided that academic rigour doe not require that I read The Duke of Clarence carefully because it is a completely different genre than The Woman of Colour. There won’t be many similarities in terms of plot points at any rate.

Joan of Arc So, in terms of my project of reading novels that were perhaps written by the same person who wrote The Woman of Colour, I have decided that academic rigour doe not require that I read The Duke of Clarence carefully because it is a completely different genre than The Woman of Colour. There won’t be many similarities in terms of plot points at any rate.The Duke of Clarence could very well have been written by the author of Rebecca. Both books feature highly emotional and overwrought language from both male and female characters (as of course do many other novels of the era). Rebecca had a fat character, Mrs. Nesbitt, who was held up to ridicule. In The Duke of Clarence, the evil priest is a fatty, who “waddled out” of heroine’s apartment, “with all the haste his corpulent person would admit of,” and he actually later dies after he trips because he’s so fat.

Although the emotions run high and the dialogue is florid, the narration really plods in this book. As in Rebecca, people's movements are described with clunky amateurish prose. Here, the nasty uncle arrives at the castle after Elfrida's father dies. She's up in her chamber crying, so her father's ward, Edgar, receives the earl. “Where is my brother’s chaplain, sir?” demanded the earl.

“I will desire him to attend your lordship,” replied Edgar, pleased at a pretext to quit the room.

“Do so sir, and I will thank you.”

Edgar withdrew, and presently met with Anthony, who was hastening to the earl—“The earl inquires for you, father.”

“You have seen him then, my son?”

“I have—ah, how much unlike his noble relative! But he is the uncle of Elfrida, and as such I respect him—but his lordship will be impatient.”

“I will attend him immediately,” said Anthony, leaving the youth.

The Duke of Clarence fell in the Battle of Baugé, France, 1421 Page after page of this plodding stuff...

The Duke of Clarence fell in the Battle of Baugé, France, 1421 Page after page of this plodding stuff...As with Rebecca, the misunderstandings between the lovers are unconvincing and artificially protracted. Elfrida’s father, on his deathbed, gives her permission to marry Edgar if he comes back triumphant from the latest campaign in France, but being a modest maiden, she can’t share the good news with Edgar, so they have a ridiculous conversation. “Deeply blushing,” she promises him (referring to herself in third person) “Elfrida will not, shall not, marry any but him her father has selected for her husband,” which sends Edgar into a rage of despair because he has no reason to assume that he’s the lucky guy.

He goes to France to help the king hold on to the French territories won by Henry V, which means they are up against Joan of Arc, who is mentioned but who does not appear in the story. He's falsely accused of ravishing a married woman, so further misunderstandings arise between him and Elfrida.

The authoress of this book can never decide if her hero is performing “miracles of valour,” or if he is participating in an immoral, unjustified war. In one chapter, Edgar “persevered in his glorious resolve” for a cause which should “animate every Briton’s arm.” In another chapter, the authoress upbraids the king for his absurd pretensions to the throne of France and being “deaf to humanity, actuated alone by the desire of conquest and monopolizing power, he has been the means of destroying thousands, and of leaving their helpless families a prey to poverty and sorrow!”

But considering that this is a female author, she tackles warfare and battle with more brio than many other female authors--as we know, Austen stayed away completely from warfare scenes.

Vengeful ghost A hard-won happy ending

Vengeful ghost A hard-won happy endingWell, in case you're on tenterhooks, Edgar and Elfrida do manage to make it to the altar, after several separations and misunderstandings. And after having to listen to a lot of backstories.

Two ghosts appear in the story and I assumed that at some point we’d learn that they are not real ghosts, but somebody dressed up as a ghost (the Scooby Doo ploy), but by golly, there was no such explanation. The reviewer for The Monthly Review thought including real ghosts was an “absurdity” and “an injury to young minds to impress on them, in tales of this kind, the belief of their real existence.”

It’s a mystery to me why this book was republished in Dublin and reprinted in 1831, but it was.

I’ve still got at least one more historical title to look at, Jacquelina of Hainault (1798). There was a real historical Duke of Clarence who was killed in battle in France but he was not married to someone named Emmeline and he had no son named Edgar.

The foundling who turns out to be of noble birth is of course a staple of novels of the long 18th century. Scholar Elizabeth Neimann calls this type of novel a “providential” novel, "built on the secret nobility of the hero or heroine. Yet this is an open secret; the hero’s exceptional good looks and virtuous mind unsubtly signal his real identity to readers as does his pervasive feeling of discomfort when living as a commoner.” The providentiai novel assumes a conservative mindset, in that people are born noble or common, as God ordains.

Neiman, Elizabeth. Minerva's Gothics: The Politics and Poetics of Romantic Exchange, 1780-1820. University of Wales Press, 2019.

Previous post: Rebecca

Published on November 18, 2025 00:00

November 10, 2025

CMP#234 Rebecca the heroine of sensibility

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Spoilers abound in my discussion of these forgotten novels, and I discuss 18th-century attitudes which I do not necessarily endorse. CMP# 234 Rebecca the Heroine of Sensibility: Rebecca (1799) by Mrs. E.M. Foster

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Spoilers abound in my discussion of these forgotten novels, and I discuss 18th-century attitudes which I do not necessarily endorse. CMP# 234 Rebecca the Heroine of Sensibility: Rebecca (1799) by Mrs. E.M. Foster

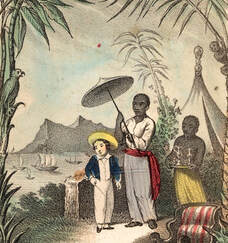

No author on title page Rebecca is one of 22 novels that may—or may not—have been written by the author of the 1809 novel The Woman of Colour, a book which has attracted a lot of academic interest in recent years. I’ve been entertaining myself by reading these novels to see if I can find similarities to The Woman of Colour.

No author on title page Rebecca is one of 22 novels that may—or may not—have been written by the author of the 1809 novel The Woman of Colour, a book which has attracted a lot of academic interest in recent years. I’ve been entertaining myself by reading these novels to see if I can find similarities to The Woman of Colour.Rebecca, published in 1799, is one of the earliest in this chain of novels which stretches from 1795, with the historical novel The Duke of Clarence, to 1817 and The Revealer of Secrets. One similarity worth noting is that the father of Olivia Fairfield in The Woman of Colour, and the father of Rebecca Elton in this novel, both tell their daughters who they should marry in their last will and testament.

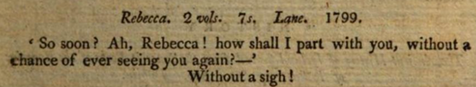

I have a lot to say about Rebecca, even though it is a minor, third-rate novel. It earned only a brief literary snort from the London Review, which quoted a bit of dialogue: “Ah, Rebecca! How shall I part with you?” to which the reviewer answered: “Without a sigh!”

Yes, the dialogue is often clichéd (and exceedingly florid to our modern tastes) and the narration is stilted. In that respect, we can contrast this authoress with Jane Austen. We can compare the themes and tropes of other novels of this era, and at some point, I’ll come back to it to discuss more similarities to The Woman of Colour, but not quite yet... Raging sensibility

The authoress of Rebecca, who has been identified as “Mrs. E.M. Foster,” claims to be an “Old Maid” (The “Mrs.” honorific was given to older ladies at this time even if they were single) who has never experienced “la belle passion” and who derived the details of her love story “from other tender works.” However, her love-scenes are not terse and contained, as with that more famous spinster, Jane Austen. Rebecca is more than a sentimental novel, this is a novel of sensibility. Rebecca's admirers rant, fall on one knee, smite their breasts, and weep. “Oh Rebecca! I cannot suppress my love, my adoration, which at this instant almost madden me… on you alone depends my every moment of future comfort; from the first hour I beheld you, you were the mistress of my fate.”

But so what if Mrs. Foster's writing lacked originality? Modern scholars like Elizabeth A. Neiman speak of the “intertextuality” of the Minerva Press novels. This stable of authors engaged, in a way, in a collaborative effort. The same stock characters, the same sentiments, the same tropes, reappear in many of them. Minerva Press readers knew what they were getting when they borrowed a Minerva novel from the circulating library and this was perhaps the secret to their success in the literary marketplace.

Lansdowne Crescent, Bath A Heroine Enters the World

Lansdowne Crescent, Bath A Heroine Enters the WorldWe meet our beautiful heroine--with her naturally curling hair left unpowdered and dressed in a simple but becoming muslin gown--as she arrives in Bath, where she is instantly dismayed by the contrast between her country home, with its “balmy fragrance of nature in the spring, and... the genial warmth of the sun” and the home of her aunt, with its “sickly glare,” and the “overpowering perfume of rooms, which were prepared for… the most fashionable and brilliant of the company who remained at Bath so late in the season.”

To be fair, something weighs heavily on our Rebecca's mind; her parents want her to marry Reuben Manly, the son of their good friends, the local parson and his wife. They’ve known each other since their infancy and he’s a great guy. But, sighs Rebecca, “I love him with the pure, the disinterested affection of a sister, far different from the tumultuous passion which he professes toward me.”

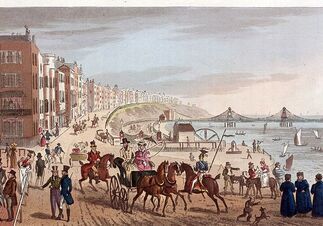

In Bath, Rebecca's aunt Mrs. Mellville and her cousin Caroline are kind to her. Caroline is saucy and vivacious, except when the subject of Reuben Manly comes up, then she turns red and pale by turns. They all jaunt off to Teignmouth (which is spelled T------- for some reason), and stay at the B----a V----a, that is, the Bella Vista, which is where Jane Austen and her family also stayed in 1802 and 1804. This sea-side resort boasts a circulating library, public rooms, and bathing-machines. And a cast of crazy characters!

Grok-created illustration Personalities and Plots

Grok-created illustration Personalities and PlotsThe Mellvilles socialize with the typical and varied cast of characters who always populate novels of this era. Each one represents a particular moral or social failing which surprises, amuses, or repulses the heroine. There's the oily army captain with his extravagant compliments. The hyperactive Miss Selby goes for long walks and arrives with muddy half-boots and muddy petticoats. The fat and hypochondriacal Mrs. Nesbitt is caught by one visitor: “ravenously devouring a great plate of toast, swimming in oiled butter, the transparent liquid emerging from the corners of her ambrosial mouth.” One is reminded of Austen’s Arthur Parker in Sanditon.

A pair of spinster sisters, the Miss Brownes, do not come in for the usual ridicule meted out to old maids, such as we find with Susan and Diana Parker in Sanditon. They have accompanied their friend Mr. Digby to Teignmouth in the forlorn hope that he will recover his health. Rebecca joins them in attending to Mr. Digby’s bedside as he dies of a broken heart. For one thing, his wife treats him terribly, then she deserts him and runs off with a fortune-hunting soldier. Mr. Digby takes this a lot harder than Mr. Rushworth in Mansfield Park, perhaps he was already consumptive or already heartbroken because his beloved younger sister and his brother-in-law just up and disappeared a few years ago. Nobody knows where they went. If only he could find his sister before he dies!

Rebecca’s got another interesting mystery to ponder—while out on a long morning walk, she comes across a cottage where a young woman and her little daughter live in utter seclusion and secrecy under an assumed name. Who could this woman be?

Colorized by Grok Love amidst the bed pans

Colorized by Grok Love amidst the bed pansAt any rate, Mr. Digby’s brother. Captain Clarence Digby, also comes to Teignmouth to succor him as he’s dying and he falls in love with Rebecca. But “insurmountable obstacles” keep them apart! One obstacle is Rebecca’s vacillation and timidity over whether she should marry Reuben to please Reuben and their respective families. By the terms of her father's will, half of her substantial fortune goes to Reuben if she marries him, but she doesn’t care about that, and she is willing to gift him with half of her fortune anyway, as a sort of consolation prize for not marrying him. But he wouldn't take the money from her, so that’s not really an issue. Altogether, I found these obstacles unconvincing. Just spit it out, girl.

Rebecca is prone to feeling the most exquisite sensations of pity and pain, so she spends a lot of time weeping. I think there must have been a kind of fashion for pale and wan heroines at this time. Like “heroin (not heroine) chic” on the fashion runway. What girl today would be pleased if the man they loved showed up and spoke with concern of her “pallid cheek” and “languid eye”? No woman likes being told that they look tired. Well, Clarence confesses his love to Rebecca, pallid or not, but he thinks Rebecca is engaged to Reuben so, after heaving many a sigh, he takes himself off to the battlefield in despair.

The Reading Rooms at Teignmouth, Thomas Allam, 1830 Staunch conservatism

The Reading Rooms at Teignmouth, Thomas Allam, 1830 Staunch conservatismThis kind of dramatic sensibility is associated with the Romantic era, but the novel also has an emphatically conservative and anti-Jacobin subplot, which warns against the excesses of radicalism. It turns out that Mr. Digby’s missing brother-in-law Mr. Selby was an idealistic young fellow caught up in the dawn of the French Revolution. He goes to France, gets fleeced out of his fortune, then is betrayed and sent to prison. Rebecca’s mysterious cottage-dwelling friend is of course the anguished Mrs. Selby. There is no good reason why this should not have all come to light well before the latter half of the second volume and the only reason it didn’t is the unconvincing behaviour of all involved.

For this and other reasons, Rebecca reads very much like a debut novel, although according to the attribution list, it’s Mrs. Foster’s fourth effort. You would think that by her fourth novel she would know not to name one character “Miss Selby” and another “Mrs. Sedly.”

Some of the group dialogue is lively and natural-sounding, but her narration often reads like a stage direction (“Saying this, the two cousins separated”) and she relies, again and again, on illness and impending death for her plot points. Three couples in this book fall in love when the man admires how well the girl conducts herself while nursing a dying invalid. Illness and death is used to move her characters from point A to point B, or to keep them at point A when they want to go to point B. By contrast, Austen needed to get the Grants out of the way and strike Thomas Bertram with a nearly-fatal illness in Mansfield Park, and she does it with some clever sleight of hand.

Austen's cousin Eliza de Feuillide Anti-feminist message

Austen's cousin Eliza de Feuillide Anti-feminist messageModern academics are in the habit of looking for feminist subtexts and rebukes of the patriarchy in these old novels, and it seems that the best recommendation you can give a forgotten novelist is to call her a feminist. Scholars on the hunt for feminism or other "isms" vastly outnumber scholars who acknowledge the most obvious in-your-face aspect of these novels, which is their Christian moralism. As for the feminism… well, you have to dig for it and ignore countervailing evidence. What about the many critical portraits of women who have plenty of power and who use that power against men? That includes The Woman of Colour, where the villain is a woman.

Unfeminine women are unambiguously condemned in this novel. “Did every female talk and act like [Caroline and Rebecca],” Reuben opines, “the ladies would soon regain that place in the estimation of mankind, which their monstrous and glaring violations of nature have robbed them of.” Poor Mr. Digby is portrayed as being unable to keep his wife under control: “Rebuke, remonstrance had no avail; they returned to England, her conduct still the same, his spirits broken… till unable to bear up against the destruction of all his hopes, and all his happiness, he has yielded to her sway, and, too weak to resist its attacks, is declining to the peaceful grave, the melancholy victim of a mercenary female.” The Amazonian Miss Selby—who admires Mary Wollstonecraft and calls her a “genius”--drowns after taking up gondola-paddling.

On the other hand, a virtuous women can come to grief as well. Through her backstory, we learn that Mrs. Selby unquestioningly follows her husband to revolutionary France and then he instructs her to escape back to England and hide incognito until he can clear his name and return. He never does, and she misses the chance to see her dying brother. Then she learns that her husband has been sent to the guillotine, then her little daughter dies and she goes crazy; all of this seems a disincentive for wifely obedience and feminine submission and an incentive for substituting your own better judgement.

Ouch! Sarcastic review from the Monthly Review. Just as with our previous novel, the heroine does not marry her childhood companion, but marries someone else. Rebecca and Clarence finally sort themselves out, and Reuben consoles himself by falling in love with saucy cousin Caroline, who has always loved him.

Ouch! Sarcastic review from the Monthly Review. Just as with our previous novel, the heroine does not marry her childhood companion, but marries someone else. Rebecca and Clarence finally sort themselves out, and Reuben consoles himself by falling in love with saucy cousin Caroline, who has always loved him. I have just started in on The Duke of Clarence, where the beautiful heroine Elfrida, of noble birth, is growing up in a castle in Wales alongside Edgar, her father's ward, who is the natural son of a knight who died penniless (or is he?). What could possibly go wrong? Mrs. Foster followed up Rebecca with Miriam (1800) and Judith (1800) If the attributions are correct, she also wrote some historical fiction, including The Duke of Clarence.

Top level quiz for Janeites: Did you notice the "sickly glare" that appalls Rebecca when she goes from the city to the country? Remind you of anything?

Here is a brief summary of The Woman of Colour, another modern academic recap which manages to discuss a Christian evangelical novel without once mentioning the religious faith which inspires and consoles the heroine in good times and bad. Is it just considered bad form to mention religion these days?

Jane Austen’s cousin Eliza de Feuillide’s husband the Comte de Feuillide met his end at the guillotine as well. I’m sure relatively few English families could boast this distinction.

Neiman, Elizabeth A. Minerva’s Gothics : The Politics and Poetics of Romantic Exchange, 1780-1820 University of Wales Press, 2019.

Previous post: Substance and Shadow

Published on November 10, 2025 00:00

November 6, 2025

CMP#233 Mary, the Fanny-like heroine

“Though I am mute, I am not always unobserving.” “it had even the power of partly raising Lady Lauretta from her recumbent attitude, who had almost given it her attention.”“Mary, who always felt too insignificant in her own estimation, to take umbrage at any rudeness which was offered to her, very readily agreed to be of the party.” -- Some quotes from Substance and Shadow for the delectation of Mansfield Park fans.

“Though I am mute, I am not always unobserving.” “it had even the power of partly raising Lady Lauretta from her recumbent attitude, who had almost given it her attention.”“Mary, who always felt too insignificant in her own estimation, to take umbrage at any rudeness which was offered to her, very readily agreed to be of the party.” -- Some quotes from Substance and Shadow for the delectation of Mansfield Park fans.Substance and Shadow, or, the Fisherman’s Daughters of Brighton, a Patchwork story in four volumes by the author of Light and Shade, Eversfield Abbey, Banks of the Wye, Aunt and Niece, etc. etc. Minerva Press, 1812. CMP#233 Substance and Shadow, a forgotten novel with a lot of Austen parallels

Brighton, T. Cruickshank (detail) 1824 Substance and Shadow opens with a genteel lady watching a storm blow in to the shore at Brighton, then a fashionable watering place patronized by the Prince of Wales. Mrs. Elwyn is amused by the rhapsodies of another young lady gamboling along on the beach, exclaiming over the tremendous crashing of the waves. We have here the same dichotomy Jane Austen used in Sense and Sensibility. Clara Elwyn “knew that romance and enthusiasm were the leading features of the day, and that those feelings were nurtured and indulged, at the hazard of running counter to all the forms and usages of society, and the good old way in which she had been taught to walk.”

Brighton, T. Cruickshank (detail) 1824 Substance and Shadow opens with a genteel lady watching a storm blow in to the shore at Brighton, then a fashionable watering place patronized by the Prince of Wales. Mrs. Elwyn is amused by the rhapsodies of another young lady gamboling along on the beach, exclaiming over the tremendous crashing of the waves. We have here the same dichotomy Jane Austen used in Sense and Sensibility. Clara Elwyn “knew that romance and enthusiasm were the leading features of the day, and that those feelings were nurtured and indulged, at the hazard of running counter to all the forms and usages of society, and the good old way in which she had been taught to walk.”But Mrs. Elwyn is concerned because she knows that a fisherman and his wife had gone out to sea that morning, and have not returned. The following morning brings the sad news that they are drowned, and Mrs. Elwyn benevolently visits the humble cottage where their twin infant daughters are being cared for by a neighbor woman. The babies will now become the responsibility of the parish and their prospects are bleak. Suddenly, the excitable young lady, also drawn to the news of the catastrophe, swoops in and carries off one of the babies. Mrs. Elwyn decides to give a home to the other. It will give her someone to care for, since she is childless and her husband is polite but remote and often absent... An experiment in education

So, we have the situation of twin girls separated almost at birth, and raised in completely different ways. This is yet another novel which stresses the importance of upbringing and education in the formation of character, and hence, one’s destiny in life.

When Mrs. Elwyn asks for her husband’s permission to foster little Mary in their home, he responds with: what a coincidence! He wants to introduce a little boy into the household, who is the…. uh…. the orphaned son of a good friend whom he had never happened to mention before. His name is Henry.

Mrs. Elwyn raises Mary while Henry spends most of his time at boarding school and university and Mr. Elwyn sinks into stupid lethargy. She aims to make little Mary into a “reasonable and rational being” so “rational and reasonable ideas must be implanted in her mind.” But don't be misled by the use of "rational" to suppose that Mrs. Elwyn is a disciple of Mary Wollstonecraft. Quite the opposite. This is definitely a conservative novel that praises virtue, modesty and forbearance. The authoress makes her intention very clear: “our design is to shew the practical advantages of a judicious education, and the stability and strength of mind which may be derived from an early knowledge of religion, and an exercise of its duties, even by a weak and timid female.."

Mary grows up to be intelligent and clever like Fanny Price in Mansfield Park, but she hides her light under a bushel, because of the “modesty of her disposition.” As a girl from a humble background elevated into a genteel household, Mary also has Fanny Price's socially ambiguous status.

Patchwork coverlet made by Jane Austen, her mother and Cassandra Secrets come to light

Patchwork coverlet made by Jane Austen, her mother and Cassandra Secrets come to lightMrs. Elwyn dies, leaving four thousand pounds for Mary to inherit when she comes of age or marries. Mary will not be forced into getting a job, but she is stuck with living with Mr. Elwyn and a new foster-stepmother. For, after Mrs. Elwyn is buried, Mr. Elwyn’s guilty secret comes out--he confesses that he was already married when married Clara! In his youth, he secretly married the pretty sister of a school chum. The school chum died, so there was no-one to stand up for the poor girl when he lied to her and told her their marriage was invalid, due to their being underage. He married his cousin Clara for the secure family money, and parked his first wife Ellen in a cottage. They had a son. So Clara Elwyn went to her grave without knowing that her loveless, childless marriage was also bigamous and Mr. Elwyn got away with it. Henry and Clara try to adjust to this awkward new situation. On the plus side for Henry, he's acknowledged as Mr. Elwyn's legitimate son and heir.

Mr. Elwyn brings his long-neglected first wife into the mansion. Her youthful charms have fled, she is merely an underbred, uneducated woman who lives for gossip and making patchwork quilts, an occupation that for some reason, the authoress scorns.

The neighborhood is also enlivened by the arrival of a couple recently returned from India: General Maxwell and his much older wife. They have houseguests too, Lady Lauretta and her daughter Lauretta Montgomery. This young lady bears an uncanny resemblance to Mary, except that Mary dresses simply and soberly and Lauretta is decked out and groomed to the nines. Incidentally, the Maxwells, Lady Lauretta, and her daughter have all just returned from the East Indies--yet another example of how authors of the time used the Indies, East and West, to keep their characters off-stage when their absence is needed for plot purposes (cough Sir Thomas cough).

Thomas Rowlandson, "Comforts of Bath" Mansfield Park-isms

Thomas Rowlandson, "Comforts of Bath" Mansfield Park-ismsOur mild-tempered heroine just can’t approve of Lauretta Montgomery and her flirtatious ways, but Henry is besotted with her. Mary can’t understand how Henry is “blind” to the faults of both mother and daughter: “‘His perception, his discernment, are usually not defective; is it possible that he cannot see it? Or is it possible that I see it through a prejudiced medium?' and then would she take herself to task, and try to discover whether to malice, envy, or uncharitableness, she could impute her opinions on this subject.”

At least Mary, unlike Fanny, has the advantage of an impartial bystander who sees things as she does—the blunt but kindly old neighbour Mr. Munsden.

Mr. Elwyn suddenly dies, and the widow Elwyn, the addle-pated Ellen, soon marries one of her male servants. To escape this trying situation, Mary goes to live with Mr. Munsden’s widowed sister in Bath. While there, she goes to a musical concert and encounters Henry busily courting Lauretta, and also Henry’s friend Frederic Fitzallen, who is quite taken with her.

Rev. Thomas Secker (1693 –1768) by Reynolds Spoiler wrap up

Rev. Thomas Secker (1693 –1768) by Reynolds Spoiler wrap upFrom here, chickens come home to roost for all the characters. Henry impulsively marries Lauretta and belatedly discovers what a selfish, immature character she is. He had started this novel in the pole position for being the hero, but by volume IV he is a miserable gambler, throwing away the family fortune at the card table. Lauretta’s mother is jilted at the altar, Henry's mother is miserable in her marriage to the servant, while Mary has enough money to take a nice cottage with her friend Miss Letsom. The young ladies are quite content in their new life and I think the authoress promotes the desirability of a quiet life of self-sufficiency--but on the other hand, this is a four -volume novel so the heroine should get a marriage by the end of it. And she does, to Mr. Fitzallan, now Sir Frederic on the death of his father.

The authoress finishes off by quoting Thomas Secker, the Archbishop of Canterbury: “Length of days, easy circumstances, general esteem, domestic tranquility, national good order and strength, are the smaller advantages that usually attend practising the rules of religion; but the constant ones, the calm peace, and joyful prospects, of all whose minds are duly affected by the genuine principles of it, these are blessings inexpressibly great.”

Heroine Mary is a sympathetic character despite being a heroine in the gentle, forbearing Fanny Price mode. She is free of Fanny’s tendency to passive-aggressiveness. She acts quickly when Lauretta's muslin gown catches fire, grabbing a shawl to smother the flames--what would Fanny have done in the same situation?

Substance and Shadow did not receive any reviews when it was published, but I found it to be fairly engaging and it kept me guessing whether Mary would end up with Henry or Frederic. The authoress makes good use of all her characters in her plots and subplots. The hero is introduced late into the story but he is the one who takes the initiative of visiting Brighton to confirm that Lauretta and Mary are sisters and of legitimate birth. This is to counteract a malicious rumor that the late Mrs. Elwyn had an illegitimate child and lied about Mary being a fisherman’s daughter.

I also expected to learn that somehow or other, Mary and Lauretta weren't the humble offspring of a fisherman and his wife. That their mother was perhaps of genteel birth or something--because usually foundling heroines turn out to be well-born, a notion that upholds heredity over upbringing, or nature over nurture. This author gives us a heroine who is actually a fisherman's daughter who marries a baronet. And he's happy to marry her because he recognizes her worth as a person.

About another six novels to go before I’ve read through all the novels involved in the attribution chain of The Woman of Colour. Previous post: An old review of Mansfield Park

Not everybody who reads Mansfield Park is happy with Fanny Price marrying her cousin Edmund. I had to contend with this question myself as the plot for my Mansfield Trilogy unfolded. For more about my novels, click here.

Not everybody who reads Mansfield Park is happy with Fanny Price marrying her cousin Edmund. I had to contend with this question myself as the plot for my Mansfield Trilogy unfolded. For more about my novels, click here.

Published on November 06, 2025 00:00

October 28, 2025

CMP#232 A 100-year old review of Mansfield Park

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Spoilers abound in my discussion of these forgotten novels, and I discuss 18th-century attitudes which I do not necessarily endorse. CMP#232 An (almost) 100 year-old review of Mansfield Park I was doing some research into how the reception of Mansfield Park has changed since it was first published. It is now generally regarded as her least popular novel, and some say, her least successful novel artistically. It's a favourite of mine, obviously, since I wrote an Austenesque trilogy based on it. In my own books, I had to come to terms with the slave trade and the fact that Sir Thomas owns a plantation (called an "estate" in the book) in Antigua. The issue of slavery was not an issue for a critic writing 100 years ago, even though they were not as far removed from the time of slavery.

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Spoilers abound in my discussion of these forgotten novels, and I discuss 18th-century attitudes which I do not necessarily endorse. CMP#232 An (almost) 100 year-old review of Mansfield Park I was doing some research into how the reception of Mansfield Park has changed since it was first published. It is now generally regarded as her least popular novel, and some say, her least successful novel artistically. It's a favourite of mine, obviously, since I wrote an Austenesque trilogy based on it. In my own books, I had to come to terms with the slave trade and the fact that Sir Thomas owns a plantation (called an "estate" in the book) in Antigua. The issue of slavery was not an issue for a critic writing 100 years ago, even though they were not as far removed from the time of slavery. I also had to deal with the widespread perception of the heroine Fanny Price as a prim little prig, or a timid little mouse. The anonymous author of this 1927 review, reproduced below, doesn't like Fanny, Edmund, or the book, but his opinions and the way he phrased them amused me. I think other Janeites would like this too, even Mansfield Park fans. But if you haven't read Mansfield Park, be advised, this review contains spoilers.

Sir Thomas and Mrs. Norris after his return from Antigua MANSFIELD PARK—JANE AUSTEN’S WORST NOVEL

Sir Thomas and Mrs. Norris after his return from Antigua MANSFIELD PARK—JANE AUSTEN’S WORST NOVELSheffield Daily Telegraph, Jan. 20, 1927

When new books fail to charm—and there comes a time when they do, and when all one’s favourite modern authors seem to be writing tiresome rubbish—there is no cure so good for the soul as to re-read old ones. We suspect that advancing age has much to do with this failure to find a new book to our taste.

To anyone suffering from this sad fate, whatever his age and literary preferences, we unhesitatingly recommend a course of Disraeli novels or those of Jane Austen.

To write of Jane Austen in general is like trying to find something new to say about the weather… Yet there remains, we think, something to be said of Mansfield Park. Perhaps it was because we read it last of all, of perhaps because it really is not so good as the others, that we must admit to finding it a very mediocre performance. Compared with the charming simplicity of Catherine Morland, the robust sense of Elinor Dashwood, the quiet intelligence of Anne Eliot or the satirical wit of Emma Woodhouse, Fanny Price is a dull and extraordinarily priggish heroine. As for Edmund Bertram, he is a prince of prigs indeed. Writers on this book have said that it is [mediocre] because in it Jane Austen tried to paint a moral lesson based on a wrong view of life, that she failed to hold the attention. If this is so we must concede that its morality (to our modern eyes amazingly overdone) is not only above question but also swamps everything in the way of humour in its overwhelming flood.

Henry and Mary Crawford are the only bright spots, and lest we should be dazzled by their charms to the extent of becoming bored with Fanny and Edmund, we are not allowed to admire them. Jane Austen is determined to be on the side of the angels, and she will not have us against her, so she makes them charming but frail. Henry is a flirt whose intentions are never honourable (save when he falls in love for a short time with Fanny) and Mary is presumed to be a monster of heartlessness because she will not marry the prim Edmund, and settle down to comparative poverty as a country parson’s wife at Thornton Lacey.

The Critic on the Hearth

The Critic on the HearthWe could never blame her. Edmund repelled us from the first. He is a well-meaning moral snob of the first quality. From the beginning, though captivated by her beauty, he criticises her conversation, behaviour, and view of life. Had Mary married him she would have had to live with the critic on the hearth to the end of her existence. But we do not believe she would have borne it so long, she must have left him, and there would have been another awful family skeleton in the Bertram cupboard.

But it is not only the behaviour of Fanny and Edmund that rouses our surprise and incredulity. The whole Bertram family are odd in their ways. When Sir Thomas is absent in Antigua a little gaiety manages to creep in (much to the horror of the two cousins) chiefly through the agency of Mr. Yates and the Crawfords. The young people proceed to erect a theatre in the billiard room, Mrs. Norris buys yards of green baize for a curtain, and private theatricals are in active rehearsal; when the sudden return of Sir Thomas at least a week before he was expected, throws them all into a fright, and the whole scheme is immediately abandoned.

Private theatricals, 1983 version There are many things in this episode that seem not a little absurd to modern minds. First the fuss and preparation that attended the event. Present-day “young people” would not have gone about it so elaborately. They would not have needed a scene painter from London, a real stage, a baize curtain, and the rest. The play would have been got up in a week or less, and with little fuss, though doubtless with a good deal of untidiness. But it is the manifestly guilty conscience of the Mansfield Park amateurs in [the] face of their father’s return, and their prompt realisation that the whole scheme must be abandoned questioningly, that surprise us most.

Private theatricals, 1983 version There are many things in this episode that seem not a little absurd to modern minds. First the fuss and preparation that attended the event. Present-day “young people” would not have gone about it so elaborately. They would not have needed a scene painter from London, a real stage, a baize curtain, and the rest. The play would have been got up in a week or less, and with little fuss, though doubtless with a good deal of untidiness. But it is the manifestly guilty conscience of the Mansfield Park amateurs in [the] face of their father’s return, and their prompt realisation that the whole scheme must be abandoned questioningly, that surprise us most.We have learnt how parents should be brought up since then, and though a modern Sir Thomas might be pardonably vexed at finding his own study about to be used as a green room, his billiard room in a mess, and his daughter (engaged to another man) endlessly rehearing passionate love scenes with a stranger [actually, they portrayed mother and son, but Maria’s character is a “fallen woman” and hence it was indelicate for her to play the part, and it gave Henry and Maria the chance to embrace and hold hands] all these things could be got over now a-days. And in the book these are not the things which seem to upset him. It is the impropriety of such a scheme among such a party and at such a time” that he deplores, and remarks about “delicacy of her situation” follow. The said delicacy being merely due to the fact that Maria is engaged to be married and that he has been away from home, does not seem to us to put such a very dreadful complexion on the proceedings. But we have the uneasy feeling that Sir Thomas expected to find his family so stricken by his long absence as to be capable of nothing but earnest prayers for his safe return.

A Bore and a Prig

A Bore and a PrigHe says—“I have come home to happy and indulgent,” but does not bear out this sentiment in his actions. In short we do not have to wait long to find out just what sort of a worthy old bore he is. It is Fanny who gives him away a few pages later:--“I suppose I am graver than other people… the evenings do not appear long to me. I love to hear my uncle talk of the West Indies. I could listen to him for an hour together. It entertains me more than many things I have done; but then I am unlike other people I dare say.”

This is one of the most illuminating passages in the book, showing up Sir Thomas with his “talk of the West Indies” and Fanny, the prig, with her certainty of being unlike other people—a type we all know, and avoid when we can.

We can only rejoice in her unlikeneness to Jane Austen’s other heroines, and hope that the absolute rectitude of their impeccable characters allowed them leisure for occasional relaxation. Perhaps the strain of two prigs in one house led her (or Edmund) to rebel and seek a little healthy entertainment before it was too late. But we fear it did not, and that Fanny bore him a large family of well-behaved children, all strictly brought up, and each more perfectly prim and proper than the last.

--(article signed) R.A.G. For more, much more, on Mansfield Park, read my series on Symbolism (and slavery) in Mansfield Park, Female education in Mansfield Park, and Lord Mansfield in Mansfield Park. S ee here for my Mansfield trilogy. Previous post: Corinne/Corinna Next post: Substance and Shadow

Published on October 28, 2025 00:00

October 22, 2025

CMP#231 Clarissa, the anti-heroine

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Spoilers abound in my discussion of these forgotten novels, and I discuss 18th-century attitudes which I do not necessarily endorse. CMP#231 Clarissa, the anti-heroine of The Corinna of England

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Spoilers abound in my discussion of these forgotten novels, and I discuss 18th-century attitudes which I do not necessarily endorse. CMP#231 Clarissa, the anti-heroine of The Corinna of England

I am slowly working my way through a dozen or so novels, all belonging to a tangled attribution chain, with the intent of figuring out whether Mrs. E.G. Bayfield or Mrs. E.M. Foster is the most likely author of The Woman of Colour, a Regency-era book which has drawn much recent scholarly interest. Next up: The Corinna of England, and a Heroine in the Shade (1809), published by Benjamin Crosby and Co. The fact that the author of Corinna of England is credited as being the author of The Woman of Colour right there on the title page to the right is not enough to prove the attribution, because the waters have been considerably muddied along the way.

I am slowly working my way through a dozen or so novels, all belonging to a tangled attribution chain, with the intent of figuring out whether Mrs. E.G. Bayfield or Mrs. E.M. Foster is the most likely author of The Woman of Colour, a Regency-era book which has drawn much recent scholarly interest. Next up: The Corinna of England, and a Heroine in the Shade (1809), published by Benjamin Crosby and Co. The fact that the author of Corinna of England is credited as being the author of The Woman of Colour right there on the title page to the right is not enough to prove the attribution, because the waters have been considerably muddied along the way.At any rate, let’s turn to the novel. No, wait, we can’t do that yet, until we first explain that Corinna of England is a parody of a tremendously successful French novel, Corinne, or, Italy (1807), by the authoress and public intellectual Madame de Stael.

Corinne caused a sensation at the time but also caused a backlash in England because of its feminist heroine. Corinne is a free-spirited poet and artist who entertained men at her home, did not shy away from fame, and openly courted the man she wanted to marry. The plot of de Stael’s novel is of secondary importance, although I will note two things which struck me; one, that de Stael uses a lot of narrative philosophical interludes which put me in mind of George Elliot, and secondly, after introducing her hero, she has him heroically rescue some people from a burning building. In other words, she gives him some hero bona fides, because otherwise he’s just some rich, well-born Englishman moping around Europe. As I have learned, a lot of leading men in these old novels are not heroes in the sense of being heroic, and some in my opinion are quite unheroic.

So that's Corinne. Now, let's move on to the 1809 parody....

The forlorn orphan meets the flamboyant heiress

The forlorn orphan meets the flamboyant heiress Scholar Miranda Kiek identifies The Corinna of England as an “anti-Jacobin” novel, meaning that it is written from a conservative English viewpoint to counter the philosophies identified with the French Revolution: “a set of beliefs referred to at the time under the catchall term of ‘new’ or ‘modern philosophy’… selfishness masquerading as utility, attacks on family and state religion, sexual voracity, grandiose but meaningless statements… and—for women in particular—a lot of attention and show. New philosophers in such novels can frequently be found advocating for atheism and free love, or knocking down some ancient edifice of England’s mythical Burkean heritage.”

The narrator of Corinne moves quickly to bring her “heroine in the shade,” the demure Mary Cuthbert, together with her flamboyant but wrong-headed cousin Clarissa Moreton (the Corinna of the title). With great narrative economy (telling not showing) she kills off Mary’s parents, a pious and upright clergyman and his wife, and sends 18-year-old Mary to live with Clarissa, who is 22 years old and also an orphan. Clarissa’s father was a successful merchant, and what we would call today a “limosine liberal.” Clarissa imbibed his progressive ideas and now holds court in the family’s old mansion (bought with new money) with a bunch of sycophants and hangers-on, including emigres from the French Revolution.

Mary arrives at this den of iniquity at the same time as one of Clarissa’s English admirers, Captain Charles Walwyn, who has brought along his friend from college, the handsome and upright Frederic Montgomery. Now the actual dialogue and action of the story begins. Both Mary and Frederic are instantly repelled by the freedom with which Corinna comports herself and the fact that she, an unmarried woman with no older chaperon, allows single men and women to live together under her roof. Clarissa’s maternal aunt Deborah also drops by frequently to scold her, but although Deborah’s heart is in the right place, the narrator makes it clear that her manner is so astringent that she does more harm than good.

Clarissa is soon attracted to Frederic, and assumes that he must be attracted to her, since after all, all men are in her thrall just like the fictional Corinne. She has no idea that he is actually drawn to her demure cousin Mary. Parallels with Austen

Clarissa has used some of her wealth to convert the old chapel of the mansion to a (gasp) private theatre! As scholar Miranda Kiek says, the author uses “thudding symbolism” when the local carpenter breaks his thigh when he falls from a scaffold while taking down a crucifix to replace it with a statue of Fame blowing her trumpet. While he is unable to work, his wife and four children face ruin. Mary encounters their humble cottage in one of her early morning walks (like any good heroine, she rises long before the rest of the decadent household) and gives what little aid she can render from her slender purse.

But let’s pause here and remark on the Mansfield Park similarities, which Kiek also saw. A demure and quiet heroine is a “heroine in the shade,” as a good Englishwoman should be. A beautiful, extroverted heiress finds herself unaccountably attracted to an upright and prudish young man who is destined for the church. Private theatricals—the play that Clarissa rehearses alone (on Sunday morning, no less), with Captain Walwyn is The Fair Penitent, a play about adultery. Here is how Kiek describes Mary Cuthbert: “Mary observes and reproves while her flamboyant cousin pronounces and acts. Mary is made the center of moral judgment, if not the center of action.” Sound familiar? But while Austen’s Mary Crawford is actually witty, Clarissa Moreton is a ridiculous egotist, a comic figure. The difficulty for a writer, of course, comes when the foil to your heroine is intrinsically more interesting than your heroine, right?

Courtesy British Museum A spectacle of herself

Courtesy British Museum A spectacle of herself To resume: Frederic Montgomery feels he must depart since he can’t endorse the wild behaviour of his hostess, although he despairs at the idea of leaving innocent young Mary behind in this den of new philosophy. There is nothing he can do about it, though, since Mary is the de facto ward of her older cousin: “yet shall I ever fervently pray for your felicity, and bear about me the remembrance of your wondrous sweetness; even though I should never meet you more—God bless you, farewell, Miss Cuthbert!”

Captain Walwyn is called back to his regiment, but the other inhabitants of the mansion—a French opera singer, two supposed French noblemen, a mediocre painter and an amateur entomologist, continue to enjoy Clarissa’s generous hospitality.

Things get even wilder when Clarissa and Mary drive in the family phaeton into Coventry where they encounter a large crowd assembled for the annual Lady Godiva ride. We never get a description of Lady Godiva, which would have been interesting, but the crowd inspires Clarissa to emulate the Corinne of the novel and make herself the center of attention, so she stands up in her carriage and makes a fiery pro-labor speech which promptly inspires a workers' uprising.

Soon, however, the crowd turns on a dime and attacks Clarissa’s mansion because she harbors Frenchmen and her loyalties are suspect. (This kind of thing happened in real life, for example when mobs turned on prominent people who had supported the French revolution--such as the scientist Joseph Priestley.)

Romantic quadrangle

Romantic quadrangleClarissa, leaving the wreck of her mansion behind to be renovated, takes Mary with her and follows Walwyn to Sussex, even though it’s his friend Frederic that she’s really seeking after.

Mary can no longer hold in her dismay at Clarissa’s conduct when they are escorted into the army barracks at Horsham and the soldiers promptly surround them and start leering at them. She runs into a room which turns out to be a sickroom, thus exposing herself and Clarissa to contagion. Clarissa removes them both to a local inn and takes to her bed, convinced that she is going to expire of fever, even though the local doctor assures her that she’s fine. When Captain Walwyn comes to call upon her, Mary remonstrates with her for even thinking of receiving a gentleman while she’s lying in bed, and Clarissa turns on her: “If I could have foreseen what [Mary’s late father] Mr. Cuthbert imposed upon me, worlds should not have tempted me to have undertaken the charge of a person, who, like a baneful planet, interposes to shroud my destiny with malign influence! Miss Cuthbert, I will see my friend. What! Are all our hours of confidence as nothing? Are the sweet interchanges of sentiment to be forgotten? And shall I discard a rooted and cemented friendship, like ours, to please a prudish girl…”

Captain Walwyn, understandably, assumes that Clarissa is in love with him, and he is looking forward to marrying an heiress. Meanwhile, Mary falls dangerously ill with a fever, but Clarissa is too selfish to stay and nurse her. She abandons her in the care of the local doctor and a nurse and takes off to see Frederic Montgomery at his family's parsonage. More farcical misunderstandings ensue between Frederic and Clarissa.

Covent Garden fire, British Museum Truth and consequences

Covent Garden fire, British Museum Truth and consequencesFrederic is horrified when he realizes Clarissa has abandoned Mary, deathly ill, in a strange town and summons her Aunt Deborah to her aid. Mary recovers while Clarissa, humiliated, retreats to London where she dies spectacularly in a real-life event, the Covent Garden Theatre fire of September 1808. Mary inherits everything and marries Frederic. The principles of propriety and religion triumph.

Female Education

Miranda Kiek notes that The Corinna of England blames Clarissa’s untoward behaviour on a faulty education and upbringing. "Anti-Jacobin fiction, especially when aimed principally at female readers, often blurs into educational treatise. Amelia Alderson Opie, Elizabeth Hamilton, and Jane West, who were all publishing novels around that time that were aimed at a similar market to that of The Corinna of England, never failed to exhaustively detail the minutiae of their heroines’ educational background.”

This again, tracks with Mansfield Park, which emphasizes the superficial education received by the Bertram girls and the consequent disaster for Maria Bertram Rushworth. Too late, their father Sir Thomas realizes that fundamental training in good principles was missing.

Madame de Stael costumed as her creation Corinne, by Massot (detail) Reviews of The Corinna of England

Madame de Stael costumed as her creation Corinne, by Massot (detail) Reviews of The Corinna of EnglandCorinna was given a favourable review in the Flowers of Literature, which is not surprising considering that the Flowers of Literature was published by Benjamin Crosby, the publisher of Corinna: “a most ingenious and successful satire against the votaries of what is erroneously called sentiment, and of the new school of philosophy. Corinna is a strong caricature, but is sketched with a masterly hand, and her eccentricities will excite alternate laughter and surprise. The visit to the horse barracks, the equivoque between the heroine and Walwyn, and the embarrassing scene before the Montgomery family are excellently managed; and while the author so strikingly evinces her power of ridicule, she no less proves her skill in striking the chord of sympathy; the characters of Mary Cuthbert and of Montgomery, being delineated with the greatest delicacy, Good sense and ability pervade throughout."

About the authoresses

Since the authorship of this novel is not confirmed, I will save my thoughts on that for a future date. Some of the other disputed books I've read so far: “The Winter in Bath,” “The Woman of Colour,” “Light and Shade", and "Black Rock House."

Germaine de Stael (1766-1817), daughter of the finance minister under Louis XVI, survived the fall of the ancien regime, the Reign of Terror, and the rise and fall of Napoleon, but much of it from a safe distance in exile. Like her creation Corinne; her considerable intellect could not be restrained by traditional gender expectations. It was reported that Jane Austen, when in London, had an opportunity to meet Madame de Stael, but turned it down. Kiek, Miranda. “Celebrity--thou art translated! Corinne in England” in Celebrity Across the Channel, 1750–1850. Eds Anais Pedron and Claire Siviter. U of Delaware Press, 2021. For me, Kiek's insights on the similarities between Mansfield Park and Corinna of England underscore the value of understanding Austen's masterpieces in context. When we read them in isolation, we can misinterpret the meaning or intent of things written more than 200 years ago.

Sylvia Bordoni's foreword to the Chawton House 2015 modern edition of The Corinna of England explains more about how Corinna of England is a parody of Corinne.

Previous post: Agatha and The Phantom Next post: A 100-year-old review of Mansfield Park

Published on October 22, 2025 00:00

October 14, 2025

CMP#230 Agatha, the Scooby-Doo heroine

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Spoilers abound in my discussion of these forgotten novels, and I discuss 18th-century attitudes which I do not necessarily endorse. CMP#230 A very posthumous novel, or Agatha, the Scooby-Doo heroine

This blog explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws

some occasional shade

at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Spoilers abound in my discussion of these forgotten novels, and I discuss 18th-century attitudes which I do not necessarily endorse. CMP#230 A very posthumous novel, or Agatha, the Scooby-Doo heroine

This post is yet another entry in the series clearing up the

tangled attribution

chain of aspiring authoress

Eliza Kirkham Mathews

(EKM) who died in 1802. 23 years after her death, London publisher Oddy & Co. issued an inexpensive one-volume novel titled The Phantom, or, Mysteries of the Castle, “by the late Mrs. Mathews, of the Theatres Royal, York and Hull." The story was offered for a mere four shillings--you can compare some other prices on their "new publications" list at right.

This post is yet another entry in the series clearing up the

tangled attribution

chain of aspiring authoress

Eliza Kirkham Mathews

(EKM) who died in 1802. 23 years after her death, London publisher Oddy & Co. issued an inexpensive one-volume novel titled The Phantom, or, Mysteries of the Castle, “by the late Mrs. Mathews, of the Theatres Royal, York and Hull." The story was offered for a mere four shillings--you can compare some other prices on their "new publications" list at right.James Burmester, an antiquarian book expert, pointed out that this London edition appears to be a re-issue of an earlier book that never made it onto any publication lists. Although the London publishers are on the title page, a publisher based in Hull has his imprint on the back of the title page and at the end. And Hull is where EKM lived with her aspiring actor husband Charles Mathews before they moved to York.

But what about this business of being of the Theatres Royal [in] York and Hull? It's Charles Mathews' second wife who was the actress, not EKM. But Anne Jackson Mathews --herself a published authoress--was alive when The Phantom came out; she was not "the late" Mrs. Mathews.

In Charles Mathews' memoir, there is no mention of EKM ever treading the boards--can she be described as being "of the Theatres Royal, York and Hull"? My research has turned up the fact that EKM did take to the stage, once in York and once in Hull, on her husband's "benefit nights." (Those are special performances when the profits from the night go to the featured performer.) So, while it might be an exaggeration, EKM could technically be described as being of the Theatres Royal of York and Hull.

This declaration jazzed up the title page of The Phantom and made the connection to the by-then-famous Charles Mathews clear to the reading public. More about EKM's theatrical career another time. Now, on to the novel itself... In previous posts, I discussed the characteristics of EKM's writing--characteristics that she shared with dozens if not hundreds of other writers, such as rapturous appreciation for scenery, moral didacticism, a heavy reliance on metaphorical phrases like "tear of sympathy" and "balm of consolation," narrative interjections and forewarnings, and so on. So instead, let's meet our (standard) characters of this gothic thriller.

We begin with our bad guy

We begin with our bad guyOur tale is set in medieval times. Mortimer Mordaunt, the Earl of some random castle somewhere in England. “The earl’s person was handsome and majestic, yet the deep furrows of care were imprinted on his brow. An air of conscious superiority marked his every action, while beneath the specious mask of politeness, he endeavoured to conceal an haughty, vindictive, and imperious spirit.”

“In pursuit of a favorite scheme his mind was strong and inventive. Religion he contemned as the work of priestcraft, and the resource of weak and enthusiastic minds.” (Here we see how people used the word “enthusiastic” in those days to signify over-the-top and irrational religious devotion.)

The earl is the guardian of the beautiful Agatha, whose parentage is a mystery. She has been raised in a nearby convent.

The earl knows he should leave Agatha in the convent and encourage her to take her vows, but “her loveliness continually disarmed him of those suggestions of prudence.”

The lovely Agatha

The lovely AgathaOur heroine checks all the boxes. She has “dark and expressive eyes" and a "luxuriance of bright amber hair” and "“a bosom unsullied as the mountain snow.” She is “unaccustomed to the gaudy scenes of life, and... Agatha breathed not a wish beyond the sanctuary which had sheltered her infant years, nor sighed for other society than those friends who had cherished the seeds of virtue in her mind, and stored it with useful and elegant instruction.”

Agatha is brought from the convent to the castle--and of course she is enraptured by the scenery along the way: “the castle, the surrounding country, the hoarse murmurs of the river, and the melodious songs of the warblers, all had power to cheer and enliven the heart of the innocent traveller. Her mind, pure and unsullied from baneful passions, received with enthusiastic rapture, the sentiments which scenes like these engender in the heart consecrated to virtue. Happy, thrice happy state of purity!”

But she is very uneasy to take up residence with the Earl Mowbray, who clearly, ahem, admires her. Agatha tells the neighbourhood religious hermit of her troubles, “she saw the tear of commiseration gather in his eye, then burst from its bounds, and stray to his venerable beard. Affected by his tender sympathy, she pressed the extended hand of her worthy preceptor to her ruby lips, and with winning softness wiped away the tear of feeling.” The castle is haunted by a phantom who shows up to give Agatha some timely advice. “’Fear not, my child,’ said the phantom, ‘I come to warn you of impending dangers, to strengthen, not to terrify. Mowbray speeds his way to the castle, beware of his evil machinations, avoid the murderer, the murderer of thy mother!’ ‘Gracious God!’ exclaimed Agatha, ‘my mother’s venerated name; tell me, celestial being, in pity tell me, who was my mother?’ ‘Time,’ replied the phantom, ‘and holy angels will withdraw the veil of mystery, adieu!’”

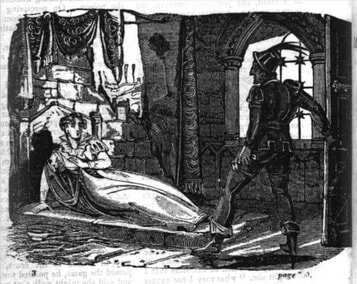

Original frontispiece The threat

Original frontispiece The threatThe danger, it becomes clear, is the lascivious propositions of Agatha's evil guardian. “[A] glow of virtuous indignation dyed her cheeks as she exclaimed, 'leave me, my lord, nor even dare again to insult me with proposals which my soul shrinks from with disdain!'

'Haughty girl,' replied he earl, 'do not provoke my vengeance, remember thou art in my power, tremble therefore, and be submissive.'

'Never! My heart scorns fear and submission, let the guilty tremble, and bow their heads to the dust, I am innocent!'

'You will repeat of this', said the earl, and hastened from the chamber."

The earl refrains from forcing himself on his niece and decides instead he had better have her killed--you'll find this same plot point in Ann Radcliffe's The Romance of the Forest. Just as with Radcliffe, it turns out the evil Earl is a usurper who has deprived his older brother of his birthright.

One of the earl's house guests, the handsome Adolphus De Burney, falls in love with Agatha, so he helps her escape through a secret tunnel to the home of the neighborhood hermit. Then he escorts her to a more distant convent, in the hopes that the Earl can't find her there. But he has to set out for the Crusades, so the lovers (I mean that in a romantic sense) must part.

One of the earl's house guests, the handsome Adolphus De Burney, falls in love with Agatha, so he helps her escape through a secret tunnel to the home of the neighborhood hermit. Then he escorts her to a more distant convent, in the hopes that the Earl can't find her there. But he has to set out for the Crusades, so the lovers (I mean that in a romantic sense) must part. The evil Earl recaptures Agatha. He locks her up for the time being in his spare castle, overseen by “the loquacious [servant] Debora.” Debora is thrown into a flurry when her master arrives, “ye blessed saints defend us… here’s the earl arrived, and with him such a train of servants; well, well, I must hasten down to receive him, though I never was worse prepared to see his lordship; the castle, as I may say, is all at sixes and sevens… Lord bless us, was ever the like before?”

In contrast, the female servant in Romance of the Forest isn't loquacious (in fact she has no dialogue at all). She isn't used as a confidante for the heroine or a device for exposition, either.

At any rate, Agatha manages to escape. Two mysterious female pilgrims show up and tell Agatha to come with them. Agatha is escorted back to St. Mary's convent.

Title page of "The Phantom" (detail)

Scooby Doo revelation

Title page of "The Phantom" (detail)

Scooby Doo revelation

We learn that sadly, the hero Adolphus has perished in a shipwreck so Agatha decides to stay at the convent and become a nun. Here is when EKM lets us know that the supernatural Phantom is not a phantom after al! It's Matilda, Agatha's mother (also one of the two mysterious female pilgrims). It might comfort Agatha in her heartbreak to know that her mother is alive, but nah... “Matilda had formed a wish of discovering herself to her daughter, but for the present determined to banish the pleasing idea, fearing it would draw her mind from her religious duties.” Makes sense. And at any rate, there is only one proper time for making astounding revelations, and that is of course, the moment when Agatha is about to take the veil.

Our hero De Burney arrives in the nick of time! He's not dead after all! Our heroine faints, and wakes up to see her father, also returned from the dead, hanging over her.

"At that instant a female rushed into the room, and flinging back her veil, discovered to the enraptured eyes of [dad] Mowbray--Matilda! His adored and long lamented wife! A scene ensued so unexpectedly tender that no being, save a celestial habitant of heaven, can pourtray it. The mind, possessed of sensibility, may imagine what words are inadequate to express."

It turns out that Agatha's father also turned hermit, i.e., he is a man who, on being told his wife and child had died while he was away at war, abandoned his title and responsibilities, and left his dependents and tenants to the mercies of his evil younger brother. He was therefore unaware that his wife, fearing for her virtue and life, had run away from the castle and was living in a cave with her faithful female attendant. As we've seen she occasionally haunted the castle to reproach the evil usurper and to falsely tell Agatha that he was "the murderer of thy mother". But she didn't rescue her daughter by taking her back through the secret tunnel to the same cave. Just... hanging out in a cave for years on end while dad was hanging out in his hermitage near that other castle. But let's not bicker and argue about whose actions made whose life miserable.

When the family is unexpectedly reunited and the false earl exposed as an usurper, Daddy Earl instantly forgives his wicked younger brother to demonstrate his Christian principles, and phantom/wife/mother calls on the heroine (whose real name is Victoria) to do the same: "'[C]onfirm that pardon which your noble sire has awarded to his brother.' 'May heaven bless me,' exclaimed Victoria, in a solemn tone of voice, as she bent over the unhappy Mortimer “as I forgive him.”

It is understood that evil uncle Mortimer will end his days in a monastery. Victoria and Adolphus are married and mom and dad renew their vows. Curtain.

Note the mark of the original Hull publisher and the obsolete use of the long "s". Plots and sub-plots

Note the mark of the original Hull publisher and the obsolete use of the long "s". Plots and sub-plotsThe main narrative I've described is abruptly interrupted three times for the dramatic backstories of three unlucky couples whose romances were thwarted. Inset narratives were exceedingly common in novels of this era--Austen used inset narratives, but more skillfully, as for example, when Colonel Brandon tells his story in Sense & Sensibility. Brandon's story is integrated into the plot. EKM's three sub-plots arguably serve as a tragic contrast to the main plot, and although I haven't read a lot of gothic novels, I suppose it was a common trope of the genre to include several tragic sub-plots involving separated lovers, as for example in Glenmore Abbey (1805) . These sub-plots also padded out the story, and The Phantom, already a short novel, would be much shorter without them. At a time when novelists could spin out a dilemma for chapter after chapter, EKM was quite terse. Here is her entire description of Adolphus' campaign in the Holy Land, something that would have taken--what, more than two years?: "Soon as the crusaders were landed on the shores of Palestine, they had repeated skirmishes, in which Prince Edward bore the palm of victory. In one of these skirmishes, Adolphus de Burney received a wound in his side, which had nearly proved fatal, and he was borne off the field of battle on the bucklers of his soldiers....[he convalesces and] the idea of again beholding his beloved Agatha enlivened his heart; joy sparkled in his eyes, and the roseate glow of hope animated his cheeks. The voyage was short and pleasant; they were now within sight of Albion’s white cliffs, and the sailors hailed with rapturous shouts their native shore.”

The Phantom reads as the production of a teenager who is a big fan of Gothic novels. There's nothing wrong with that--its how many writers learn their craft, by imitating others. I really need to read Percy Bysshe Shelley's two gothic novels that he published when he was a teenager sometime. There is no mention of The Phantom in Anne Jackson Mathews' memoir of her husband but she does say "no publisher thought [EKM's writings] worth much more than the cost of printing." I'm guessing EKM paid to have the novel printed (just as Austen did with Sense & Sensibility) but the gamble did not pay off in Hull and she was left with a lot unsold novels. A foreword that is also a disclaimer

By the 1820s, the craze for gothic novels had passed, although the genre still had its fans, of course. I don't know who arranged for the 1825 re-issue of The Phantom. Presumably it was either Charles Mathews, in fond memory of his first wife, or it was Anne Jackson Mathews, who saw a way of disposing of a pile of remaindered books. Who wrote this deprecatory foreword? Was it Anne Jackson, or the publisher?: “The following pages will not attract admiration for the brilliancy of the thoughts, the elegance of the diction, or the strict originality of the character—but the sensible and feeling heart will be interested in the fate of Agatha, who, amidst misfortunes of the most trying nature, preserves the dignity of a virtuous mind, and struggles to bear with calmness and resignation, the unmerited persecutions of [the villain who commits] deeds at which humanity shudders, and pity shrinks from, aghast and trembling.”

For more about the Gothic novels of this era, Ann B. Tracy's The Gothic Novel 1790-1830: Plot Summaries and Index to Motifs is a valuable guide, with an index like no other, with entries for "passage, subterranean," and "relative, lost, discovery of" and "veil-taking, disrupted."

For more about the way writers of this era used words like "serious" and "enthusiast" to refer to religion, I recommend Brenda Cox's book, Fashionable Goodness, Christianity in Jane Austen's England.

Previous post: West Indians in children's books

Previous post: West Indians in children's books

Published on October 14, 2025 00:00

September 30, 2025

CMP#229 An influential children's book

This month marks the fifth anniversary of my blog, which explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws some occasional shade at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Spoilers abound in my discussion of these forgotten novels, and I discuss 18th-century attitudes which I do not necessarily endorse. CMP#229 Three children's books--one plot. Also, who influenced whom?

This month marks the fifth anniversary of my blog, which explores social attitudes in Jane Austen's time, discusses her novels, reviews forgotten 18th century novels, and throws some occasional shade at the modern academy. The introductory post is here. My "six simple questions for academics" post is here. Spoilers abound in my discussion of these forgotten novels, and I discuss 18th-century attitudes which I do not necessarily endorse. CMP#229 Three children's books--one plot. Also, who influenced whom?

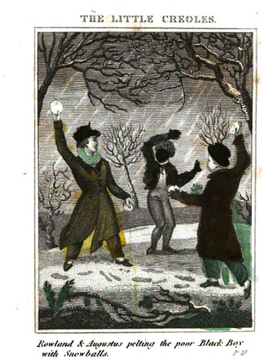

The Village School, William Henry Knight, detail In

my previous post

, I looked at two books for children, published by two different authors, both featuring a spoiled young West Indian heiress coming to England and correcting her behaviour after receiving judicious instruction from her host family. These two books are examples of a then-popular genre for children's books, which combined morally improving narratives with inset fables, scientific discourses, dialogue, and history lectures. As I mentioned, a book by Thomas Day, Sandford and Merton, was an outstandingly popular exemplar of this genre.

The Village School, William Henry Knight, detail In

my previous post