Max Eastern's Blog

November 4, 2025

Eric Ambler’s ‘Background to Danger’

By Max Eastern

Eric Ambler was a genius at building suspense. He didn’t do it brazenly or with gimmicks. He wasn’t in a hurry. Dread comes slowly in his novels. A fact is introduced to the narrative. Something small, seemingly insignificant. Later, another fact is added. A minor action is taken. The situation changes just a bit. The anxiety is turned up only a notch until the next little morsel. As the circumstances accumulate piece by piece, you eventually realize the protagonist has fallen into a trap so complex that he may not escape alive.

A good example is from Ambler’s novel Background to Danger, written in 1937.

Kenton, the protagonist, is a freelance journalist. He is in Nuremberg, Germany, covering a conference of important Nazis. He speaks German well, practically like a native. Ambler wastes no time in inserting little facts and circumstances, minor at first, even innocuous. But they grow.

Kenton is broke. He owes money on a gambling debt that must be repaid immediately. He’s desperate.He knows a man in Vienna who might lend him money. There is no other source for funds. He does not even have enough money to take a direct train to Vienna, so must transfer at Linz.A man joins him in his compartment at an interim stop.Kenton is famished and the man offers to share some food.When the man falls asleep, Kenton notices someone spying on him from the corridor.When the spy leaves, Kenton’s compartment mate admits he was not asleep but trying to avoid the spy. He turns out the light and explains to Kenton that he is a German Jew named Sachs, a factory owner whose business was destroyed by the Nazis, and he is fleeing Germany with ten thousand marks worth of German securities. But the Nazi authorities are onto him and will seize his securities at the German-Austrian border and arrest him for taking such a large amount out of the country. Kenton realizes this is a lie. The man isn’t even German. German securities are non-negotiable abroad.Sachs asks Kenton to carry the securities for him when they cross the border. An Englishman won’t be searched. He offers Kenton three hundred marks, enough to pay his gambling debt with more to spare. Though he knows something is very wrong, Kenton can’t resist this sum. A hundred fifty is provided up front. Sachs hands Kenton an envelope with papers inside. Sachs removes an automatic pistol from his suitcase and slips it into a holster.They reach the border, leave the train, go through customs without incident, re-board the train. But now the plan is changed. Sachs now asks Kenton for a further favor: take the envelope of securities to the Hotel Josef in Linz. He’ll pay him an additional three hundred marks.Ambler reveals to the reader at this point that Sachs is a Soviet agent who turned traitor and stole some important papers. The Soviets have a notorious assassin trailing him. The papers might have to do with a British petroleum company seeking concessions on Romanian oil fields. An agent working for this company is also involved. Kenton knows none of this.When they arrive in Linz, Sachs is followed off the train by the same man who was spying on him from the train’s corridor.Kenton wanders the streets of Linz at night looking for the Hotel Josef. He asks a police officer for directions. The hotel is shabby. Kenton asks the night porter for Sachs’s room. The porter asks Kenton’s name and he gives it. The porter recognizes the name as that of the man Sachs is expecting. He gives Kenton the number of Sachs’s room. Kenton is now determined to hand over the envelope, get his money, and be done with the business.Room 25 door is ajar. It’s dark inside. He calls Sachs name. No answer. Calls it again, louder. He lights a cigarette. Sachs is lying on the floor, stabbed.Kenton checks to make sure he is dead. He gets blood on his fingers. He opens the envelope. They are photographs and documents related to Russian military secrets. There are people waiting outside on the street, perhaps those who killed Sachs. Kenton leaves through a back way, is seen by one of those outside. A flashlight illuminates his face. He runs away.

And now all the facts are in place, and Kenton, through a series of tiny circumstances and minor actions on his part, finds himself in deep trouble. He cannot call the police because he would have to admit smuggling the papers into the country. The police might suspect he killed Sachs for his money. Whoever killed Sachs is after the contents of the envelope and they would murder Kenton now to get them. Kenton has provided his name to the night porter, who can also identify him. One of Sachs’s possible killers saw his face. A police officer on the street saw it as well.

The stage is set for the rest of the novel.

Eric Ambler

Eric Ambler

Max Eastern is the author of Red Snow in Winter, a thriller set in the final weeks of WWII.

October 1, 2025

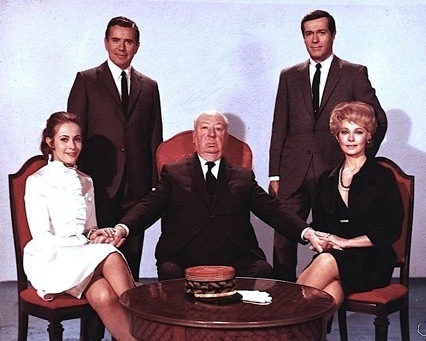

Why Did Hitchcock’s Cold War Thriller Bomb?

Alfred Hitchcock hoped his 1969 Cold War film Topaz would be a sensational hit, but it didn’t happen, despite some promising elements.

In Topaz, pieces of a puzzle are added one by one without the audience knowing the exact significance of each piece until the complete picture is revealed at the end. It starts with the defection of a Russian intelligence officer to the American side, then the French government’s awareness of this defection without anyone knowing exactly how they found out. A French intelligence officer, Devereaux, based in Washington, is asked by the Americans to obtain photographs of a document in New York, an aide-memoire, signed between the Soviet Union and Castro’s Cuba that will shed light on the relationship between the two countries.

Devereaux next travels to Cuba on behalf of the Americans to find evidence of Russian missiles (the year is 1962). In gratitude, the Americans offer Devereaux information from the Russian defector about Russian moles in the French intelligence service, thus coming back to the question of how the French government knew of the Russian defector in the first place.

These puzzle pieces are offered to the audience gradually, perhaps too gradually. Much time is spent on obtaining the photos of the aide-memoire at the Cuban delegation’s hotel in Harlem, Devereaux’s stint in Cuba, his wife’s suspicions he is having an affair with a Cuban woman, his actual affair with the Cuban woman who runs an anti-Castro underground network, and the collapse of that network. In other words, the movie is not tight and focused like a good thriller should be.

Devereaux, the protagonist, is played by the Czech actor Frederick Stafford, who, while certainly fine in the part, lacks the screen presence and charisma needed to hold this film together. Some sources suggest Sean Connery was under consideration for the part, and despite the incongruity of his playing a Frenchman, a strong, dynamic actor such as Connery was what this movie sorely needed to carry it.

Three supporting actors were excellent and more compelling than Stafford. John Vernon, playing a menacing Castro lieutenant, draws the audience to him in every scene he is in. Roscoe Lee Browne is superb as the Harlem operative who Devereaux employs to gain access to the Cuban delegation’s suites at a hotel in Harlem where he will be able to photograph the aide-memoire located in a locked briefcase in Vernon’s possession. Nominally the owner of a flower shop, Browne poses as a journalist seeking an interview with a member of the Cuban delegation, a man they know can be bribed in exchange for access to the aide-memoire. To get to this man, Browne must first pass Vernon’s scrutiny. Anticipating problems, Browne cleverly foregoes the suggestion of posing as a reporter from Playboy magazine and instead chooses Ebony, so that later, when he is confronted by the Vernon character’s reluctance to allow him access, he can play to the Communist revolutionary’s professed commitment to the marginalized and downtrodden by questioning out loud whether Vernon’s character refuses his entry because he is “anti-Negro,” thus guilting Vernon into letting him in. Finally, Philippe Noiret as one of the French intelligence officers working for the Russians brings to the role a superb combination of arrogance and panic.

Some things essential to the plot seem improbable. Devereaux is spotted by one of Vernon’s men in a crowd of hundreds if not thousands during a Castro-led mass rally in Havana. He is recognized as the man on the street in Harlem whom Roscoe Lee Browne accidentally stumbled upon while escaping from the Cubans at the Harlem hotel, and the jump is made that the stumble was in fact deliberate and therefore Devereaux must have been working with Roscoe Lee Browne, though they didn’t suspect any connection at the time. While all this is true (the stumble allowed Browne the opportunity to pass Devereaux the spy camera with the photographs in it), is a leap of logic that would only be made by characters in a movie with knowledge of the script not by real people.

In Cuba, an elderly couple working for the anti-Castro network is captured after taking important photographs of Russian missiles, thus putting the entire network in danger. Yet no one in the network wonders what became of them or even that they are unaccounted for. There seems to be no provision for this kind of eventuality even though their lives depend on it. Enough time passes for the couple to be tortured into revealing everything.

Finally, there is an elaborate scene in Cuba where one of the members of the underground network demonstrates to Devereaux how he has placed the covert film of the Russian missiles inside Devereaux’s razor blade containers so that he can smuggle the film out of Cuba undetected. But it turns out that film was not in the razor blades at all but in the binding of a blank memo book Devereaux’s mistress gave to him at the last minute, a discovery he makes by chance after he’s already out of Cuba. There is no explanation why Devereaux was kept in the dark about the true location of the film. It wasn’t as if he had no idea he was smuggling out film. In fact it was at his instigation that they took the photos in the first place. The entire circumstance makes no sense except as a pretext to provide a contrived twist when the Cubans discover the plot, search Devereaux’s razor blades at the airport and surprisingly find nothing.

The film was indifferently reviewed and earned $3,839,363 in North American by 1970. His next movie, filmed in England with a much smaller budget, did better although some people found it distasteful. That film is Frenzy.

Max Eastern is the author of the modern noir thriller The Gods Who Walk Among Us, a winner of the Kindle Scout competition.

Laura’s One Flaw

By Max Eastern

Spoiler Alert: This post will reveal the ending to the book ‘Laura,’ by Vera Caspary (and the movie, for that matter). So if you don’t want it ruined for you, don’t read any further.

What do you like most about reading a mystery novel? If it’s a Raymond Chandler work, it might be the quality of the writing, the beautiful descriptions, the cynical asides. You read Sherlock Holmes to spend time with the great man himself. For many readers, though, it’s the satisfaction of solving the mystery itself, picking up all the clues, analyzing them, figuring out who the killer is before Hercule Poirot does.

But isn’t this only satisfying if you can put yourself in the position of the sleuth, knowing exclusively what he or she knows, only those clues in the story itself? Unfortunately, sometimes an author creates a situation in which a reader will be able to solve a mystery by a clue that lies outside of the book, beyond its pages, a piercing of the third wall.

A good example of what I’m talking about is Vera Caspary’s classic noir Laura. Laura is a member of Manhattan society, an advertising executive who is found murdered in her apartment, her face obliterated by a shotgun blast. The New York City police detective, Mark MacPherson, has three suspects: Laura’s aunt, Ann Treadwell; her fiancé, Shelby Carpenter; and her mentor, an eccentric columnist named Waldo Lydecker. When Laura surprisingly shows up alive in the midst of the investigation, and everyone realizes the real corpse is that of a model at Laura’s agency, Diane Redfern, who was trying to steal Shelby Carpenter away from Laura, Laura herself becomes a suspect.

There are, of course, many clues pointing to all the suspects. Laura had an argument with Diane Redfern. Shelby lied to MacPherson about a number of things occurring the night of the murder. But there is one big clue that overshadows all the others. And it concerns Waldo.

The book is narrated by three characters: Waldo, MacPherson, and then Laura herself. Waldo is a fascinating character. His narration provides a good deal of the back story. He appears prominently in both MacPherson’s and Laura’s narration. And MacPherson spends a lot of time with Waldo. He visits his apartment twice, including the very first scene of the book. He twice has dinner with him. He sees him at Laura’s apartment. Shelby Carpenter doesn’t appear nearly as much in the book, and Ann Treadwell hardly at all. Soon it becomes obvious to the reader that the only reason so much time is spent on Waldo Lydecker is that he must be the killer. And, in fact, he is. He was so jealous of Laura’s intent to marry Shelby Carpenter that he went to her apartment and shot her. He didn’t know that Laura was away and Diane Redfern was staying there. He killed the wrong person.

So, in a sense, the reader is taken out of the pages of the book. It’s hard to ignore Waldo’s prominence. You know you’re not supposed to think about it, but you do. It’s like watching a TV show in which a very famous actor makes a guest appearance early on, and you know he must show up later in a way crucial to the plot because why else would they cast such a major star?

Fortunately, despite this one small defect, Laura is a fantastic read and justifiably one of the classics. The characters are so compelling, the writing so good, and there is so much else going on in the story and with the characters that you may even second-guess the conclusion you reached outside the story, and therefore be genuinely surprised that Waldo did it after all.

Max Eastern is the author of the debut noir mystery, The Gods Who Walk Among Us.

March 1, 2018

Why Did Hitchcock’s Cold War Thriller Bomb?

Alfred Hitchcock hoped his 1969 Cold War film Topaz would be a sensational hit, but it didn’t happen, despite some promising elements.

[image error]

In Topaz, pieces of a puzzle are added one by one without the audience knowing the exact significance of each piece until the complete picture is revealed at the end. It starts with the defection of a Russian intelligence officer to the American side, then the French government’s awareness of this defection without anyone knowing exactly how they found out. A French intelligence officer, Devereaux, based in Washington, is asked by the Americans to obtain photographs of a document in New York, an aide-memoire, signed between the Soviet Union and Castro’s Cuba that will shed light on the relationship between the two countries.

Devereaux next travels to Cuba on behalf of the Americans to find evidence of Russian missiles (the year is 1962). In gratitude, the Americans offer Devereaux information from the Russian defector about Russian moles in the French intelligence service, thus coming back to the question of how the French government knew of the Russian defector in the first place.

These puzzle pieces are offered to the audience gradually, perhaps too gradually. Much time is spent on obtaining the photos of the aide-memoire at the Cuban delegation’s hotel in Harlem, Devereaux’s stint in Cuba, his wife’s suspicions he is having an affair with a Cuban woman, his actual affair with the Cuban woman who runs an anti-Castro underground network, and the collapse of that network. In other words, the movie is not tight and focused like a good thriller should be.

Devereaux, the protagonist, is played by the Czech actor Frederick Stafford, who, while certainly fine in the part, lacks the screen presence and charisma needed to hold this film together. Some sources suggest Sean Connery was under consideration for the part, and despite the incongruity of his playing a Frenchman, a strong, dynamic actor such as Connery was what this movie sorely needed to carry it.

Three supporting actors were excellent and more compelling than Stafford. John Vernon, playing a menacing Castro lieutenant, draws the audience to him in every scene he is in. Roscoe Lee Browne is superb as the Harlem operative who Devereaux employs to gain access to the Cuban delegation’s suites at a hotel in Harlem where he will be able to photograph the aide-memoire located in a locked briefcase in Vernon’s possession. Nominally the owner of a flower shop, Browne poses as a journalist seeking an interview with a member of the Cuban delegation, a man they know can be bribed in exchange for access to the aide-memoire. To get to this man, Browne must first pass Vernon’s scrutiny. Anticipating problems, Browne cleverly foregoes the suggestion of posing as a reporter from Playboy magazine and instead chooses Ebony, so that later, when he is confronted by the Vernon character’s reluctance to allow him access, he can play to the Communist revolutionary’s professed commitment to the marginalized and downtrodden by questioning out loud whether Vernon’s character refuses his entry because he is “anti-Negro,” thus guilting Vernon into letting him in. Finally, Philippe Noiret as one of the French intelligence officers working for the Russians brings to the role a superb combination of arrogance and panic.

Some things essential to the plot seem improbable. Devereaux is spotted by one of Vernon’s men in a crowd of hundreds if not thousands during a Castro-led mass rally in Havana. He is recognized as the man on the street in Harlem whom Roscoe Lee Browne accidentally stumbled upon while escaping from the Cubans at the Harlem hotel, and the jump is made that the stumble was in fact deliberate and therefore Devereaux must have been working with Roscoe Lee Browne, though they didn’t suspect any connection at the time. While all this is true (the stumble allowed Browne the opportunity to pass Devereaux the spy camera with the photographs in it), is a leap of logic that would only be made by characters in a movie with knowledge of the script not by real people.

In Cuba, an elderly couple working for the anti-Castro network is captured after taking important photographs of Russian missiles, thus putting the entire network in danger. Yet no one in the network wonders what became of them or even that they are unaccounted for. There seems to be no provision for this kind of eventuality even though their lives depend on it. Enough time passes for the couple to be tortured into revealing everything.

Finally, there is an elaborate scene in Cuba where one of the members of the underground network demonstrates to Devereaux how he has placed the covert film of the Russian missiles inside Devereaux’s razor blade containers so that he can smuggle the film out of Cuba undetected. But it turns out that film was not in the razor blades at all but in the binding of a blank memo book Devereaux’s mistress gave to him at the last minute, a discovery he makes by chance after he’s already out of Cuba. There is no explanation why Devereaux was kept in the dark about the true location of the film. It wasn’t as if he had no idea he was smuggling out film. In fact it was at his instigation that they took the photos in the first place. The entire circumstance makes no sense except as a pretext to provide a contrived twist when the Cubans discover the plot, search Devereaux’s razor blades at the airport and surprisingly find nothing.

The film was indifferently reviewed and earned $3,839,363 in North American by 1970. His next movie, filmed in England with a much smaller budget, did better although some people found it distasteful. That film is Frenzy.

Max Eastern is the author of the modern noir thriller The Gods Who Walk Among Us, a winner of the Kindle Scout competition.

July 2, 2017

Len Deighton: Characters that come alive

Len Deighton’s characters seem so real to me that I feel as if I’m reading non-fiction–he’s not making up people but merely describing individuals who exist.

[image error]

Bernard Samson, the British intelligence agent in the Game, Set, Match Trilogy (Berlin Game, Mexico Set, London Match), is a perfect example. The same is true of Samson’s colleagues, his friends, his wife and his father-in-law. When Samson’s children come into danger, it’s not cheap exploitation for suspense as you see in generic thrillers. His kids’ peril is perfectly plausible. It could really happen.

The trilogy was written in the early 1980s before the fall of the Berlin Wall. When I read the books recently, I was absorbed into Samson’s world, turning pages every night into the early morning, eager to find out what would happen to these people. Finally, when I had no choice but to go to bed, I couldn’t sleep. Instead, I would lie there, practicing a conversation I was going to have with Bernard Samson the next day, as if I was really going to have it, assuring him that he didn’t have to worry because in only a few more years the Cold War would be over and his problems, though not solved, would be alleviated. After an hour and a half of this, I would have to remind myself that there is no Bernard Samson, I wouldn’t be having a discussion with him the next day or ever.

Most of all, I’d tell myself. Len Deighton is a brilliant writer.

Max Eastern is the author of the modern noir thriller The Gods Who Walk Among Us.

June 23, 2017

Amazon’s Summer Picks

Amazon in all of its wisdom decided to make my thriller, The Gods Who Walk Among Us, a Summer Pick. For the next two weeks, the novel is priced at $1.99. Here’s the link … and enjoy.

April 20, 2017

The Gimlet Experience

By Max Eastern

The classic noir detective is a drinker. Hard stuff usually, and lots of it. The world of crime and detectives is sordid and you tend to see the worst in humanity. The detective needs some kind of support, and a therapist just won’t do. That’s where whisky and vodka and rum come in.

And gin.

In Raymond Chandler’s 1953 noir mystery, The Long Goodbye, detective Philip Marlowe has something of what we would now call a bromance with an enigmatic Englishman named Terry Lennox. At Victor’s, a Los Angeles bar, Lennox is very particular about how he likes to drink his gin, and it isn’t in a martini:

We sat in a corner of the bar at Victor’s and drank gimlets. “They don’t know how to make them here,” he said. “What they call a gimlet is just some lime or lemon juice and gin with a dash of sugar and bitters. A real gimlet is half gin and half Roses Lime Juice and nothing else. It beats martinis hollow.”

Later, when Lennox is long gone, Marlowe finds himself back in Victor’s with a lady named Linda Loring, drinking gimlets again:

The bartender set the drink in front of me. With the lime juice it has a sort of pale greenish yellowish misty look. I tasted it. It was both sweet and sharp at the same time.

All of this made me curious about where the drink came from. It seems the gimlet may have been invented by a 19th century British naval surgeon, Dr. Thomas Gimlette, to combat scurvy, the disease caused by a lack of vitamin C that plagued Royal Navy sailors. An allotment of gin was already being served to the men, but combining lime juice with it would provide the vitamin C. Rose’s Lime Juice was developed around the same time by a Scotsman from Edinburgh named Lachlan Rose as a means of preserving citrus fruit juice.

To see the status of the classic drink in the 21st century, I went on a gimlet tasting tour myself in Manhattan, a city with its own noir status.

The first stop was the Gin Parlour, inside the Intercontinental Hotel on East 48th between Park and Lexington. Just off the lobby, it has an old-school atmosphere where Marlowe himself would’ve been at home, listening to the Ella Fitzgerald score.

[image error]The Gin Parlour

The gimlet itself was the classic, just as Terry Lennox demanded and just as Marlowe described it, though with maybe more gin and less lime juice. Edinburgh Cannonball Navy Strength Gin, which the bartender employed, is mixed with house-made lime cordial: sweet and sharp at the same time, crisp, perfect for spring. Navy strength, with the higher proof, provided a real buzz.

Second stop was the Flatiron Room on West 26th between Sixth and Broadway. Bottles of whisky and brandy and every conceivable booze stood behind the bar, lining the walls, in cabinets behind the booths, up to the ceiling, everywhere. Here, listening to live bluegrass at a wooden bar, I had a variation on the classic. Bulldog Gin with house-made blackberry juice and lime juice. It was a beautiful drink, not sweet, a subtle blackberry taste, but thick, and red like blood.

[image error]The Flatiron Room

From there I headed down to the Lower East Side to Beauty & Essex, a hip gathering ground behind a door at the back of pawnshop on Essex Street between Stanton and Rivington. Diverging even further from the original gimlet, they call their drink the Emerald Gimlet because along with the Belvedere Vodka (not gin this time) and the lime juice, they add a squirt of basil.

[image error]Beauty and Essex

The drink is a beauty to behold, and refreshing, and the pesto flavor gives it a nice, spicy kick. It went pretty well with a half dozen raw oysters.

To round out my departure from the classic, I ended up in Jewel Bako, an absolutely top-rated Japanese restaurant, one of the best in the city, specializing in sushi and sashimi. The Spring Moon cocktail offers fresh lime but it leaves out the gin and vodka altogether. Instead, it’s Sake with black currant cassis.

[image error]Jewel Bako

The drink is light, complex, refreshing, a slice of lime floating in the drink like a spring moon in a sunset. It’s also something that Philip Marlowe’s friend Terry Lennox would never have approved of, but so what? In the end, Lennox didn’t really treat Marlowe all that well anyway.

Max Eastern is the author of The Gods Who Walk Among Us, a modern noir thriller set in New York City.

[image error]

April 14, 2017

The Levanter: Suspense’s Slow Build

Eric Ambler wrote Background to Danger in the late 1930s on the eve of World War 2. Forty years later, he was still demonstrating his talent for creating suspense with a slow buildup of dread, giving the reader one little tidbit of information and then another and another until suddenly the protagonist is in a situation of great danger for which there is no obvious escape.

[image error]

The Levanter was written in the early 1970s. It takes place in the Middle East of that time. It starts in Beirut, where we are introduced briefly to Salah Galed, a Palestinian terrorist, murderer, and extortionist who is so dreaded even the PLO want him dead. Arab governments hunt him. He hides in an abandoned medieval fort in the mountains outside of Beirut. This is Ambler’s first fact, and it is allowed to sit there in the reader’s mind while the narrative shifts to the protagonist, Michael Howell.

Howell runs his family business, a small company based in Cyprus that acts as a selling agent across the Middle East, and owns factories in Syria that, in partnership with the Syrian government, manufactures, among other things, batteries. Howell has arrived in Damascus to check on his business concerns. At his office he learns something concerning: someone in his battery factory has been spending a great deal of money on an expensive order of absolute alcohol, even though this substance is not needed in the manufacture of batteries. Ambler has added the next salient fact.

Ambler lets that sit for a while as he spends a great deal of time describing the history of Howell’s family business, and in some detail, his business dealings with the socialist oriented Syrian government. Then a new fact: aside from absolute alcohol, the battery factory is receiving shipments of Mercury. The chemist Howell hired to supervise quality control at the factory is a Jordanian chemist named Issa. He was a recommendation from the Syrian government and Howell hired him even though he was caught lying about his education, or lack thereof, and his qualifications.

When he learns about the Mercury, Howell becomes worried. Even though it is late at night, he sets out unannounced with his assistant (and lover) Teresa, to the factory to check out the inventory.

The factory is well out of town in an isolated and deserted area. It is a former police headquarters from French colonial days and is surrounded by an impenetrable high wall. To get in, he must drive through a padlocked iron fence. Instead, he leaves his car outside the fence, and he and Teresa go on foot through a padlocked chain-link gate. He re-locks the gate behind him. He is now locked inside the factory grounds.

The watchman he hired is supposed to be there at the entrance but isn’t. He sees lights on in the office and in the laboratory. He hears voices. At this time of night no one should be in there, not even the watchman. He spies through a window. There is his chemist Issa, apparently lecturing a group of men taking notes. The lecture is about chemistry. Howell realizes what it’s really about. But before he can do anything, two men with machine guns appear out of the darkness.

Issa recognizes his boss but is unapologetic. One of the gunmen slams Howell in the kidney. In agony, he is brought into the laboratory. The watchman is in there, sitting in a chair, also taking notes. Howell accuses Issa of bombmaking and fires him on the spot. He fires the watchman. He threatens to report them to the police.

The watchman hasn’t moved. Now he gets up. He speaks. He reveals to Howell his true identity. He is the terrorist Salah Galed.

Howell has stumbled upon the clandestine bombmaking operation of a dangerous terrorist who has killed before. Howell is the prisoner of that terrorist in the middle of the night in a deserted area outside of Damascus in a compound surrounded by padlocked gates and an impenetrable wall. No one knows he is there but his assistant, who is also a prisoner. He is a known partner with and friend of the Syrian government, yet at the same time the terrorist activity is taking place in his factory by men he hired.

Once again Ambler has, through a series of small but accumulating facts, and the character’s deliberate responses to those facts, created a situation of extreme peril. Although the peril flows directly and logically from those facts and responses, it appears to be sprung on the reader suddenly and alarmingly.

Ambler was truly a suspense writer of great skill.

[image error]

The Levanter

Eric Ambler, creator of suspense, part 2

Eric Ambler wrote Background to Danger in the late 1930s on the eve of World War 2. Forty years later he was still demonstrating his talent for creating suspense with a slow buildup of dread, giving the reader one little tidbit of information and then another and another until suddenly the protagonist is in a situation of great danger for which there is no obvious escape.

The Levanter was written in the early 1970s. It takes place in the Middle East of that time. It starts in Beirut, where we are introduced briefly to Salah Galed, a Palestinian terrorist, murderer, and extortionist who is so dreaded even the PLO want him dead. Arab governments hunt him. He hides in an abandoned medieval fort in the mountains outside of Beirut. This is Ambler’s first fact, and it is allowed to sit there in the reader’s mind while the narrative shifts to the protagonist, Michael Howell.

Howell runs his family business, a small company based in Cyprus that acts as a selling agent across the Middle East, and owns factories in Syria that, in partnership with the Syrian government, manufactures, among other things, batteries. Howell has arrived in Damascus to check on his business concerns. At his office he learns something concerning: someone in his battery factory has been spending a great deal of money on an expensive order of absolute alcohol, even though this substance is not needed in the manufacture of batteries. Ambler has added the next salient fact.

Ambler lets that sit for a while as he spends a great deal of time describing the history of Howell’s family business, and in some detail, his business dealings with the socialist oriented Syrian government. Then a new fact: aside from absolute alcohol, the battery factory is receiving shipments of Mercury. The chemist Howell hired to supervise quality control at the factory is a Jordanian chemist named Issa. He was a recommendation from the Syrian government and Howell hired him even though he was caught lying about his education, or lack thereof, and his qualifications.

When he learns about the Mercury, Howell becomes worried. Even though it is late at night, he sets out unannounced with his assistant (and lover) Teresa, to the factory to check out the inventory.

The factory is well out of town in an isolated and deserted area. It is a former police headquarters from French colonial days and is surrounded by an impenetrable high wall. To get in he must drive through a padlocked iron fence. Instead, he leaves his car outside the fence, and he and Teresa go on foot through a padlocked chain-link gate. He re-locks the gate behind him. He is now locked inside the factory grounds.

The watchman he hired is supposed to be there at the entrance but isn’t. He sees lights on in the office and in the laboratory. He hears voices. At this time of night no one should be in there, not even the watchman. He spies through a window. There is his chemist Issa, apparently lecturing a group of men taking notes. The lecture is about chemistry. Howell realizes what it’s really about. But before he can do anything, two men with machine guns appear out of the darkness.

Issa recognizes his boss but is unapologetic. One of the gunmen slams Howell in the kidney. In agony, he is brought into the laboratory. The watchman is in there, sitting in a chair, also taking notes. Howell accuses Issa of bombmaking and fires him on the spot. He fires the watchman. He threatens to report them to the police.

The watchman hasn’t moved. Now he gets up. He speaks. He reveals to Howell his true identity. He is the terrorist Salah Galed.

Howell has stumbled upon the clandestine bombmaking operation of a dangerous terrorist who has killed before. Howell is the prisoner of that terrorist in the middle of the night in a deserted area outside of Damascus in a compound surrounded by padlocked gates and an impenetrable wall. No one knows he is there but his assistant who is also a prisoner. He is a known partner with and friend of the Syrian government, yet at the same time the terrorist activity is taking place in his factory by men he hired.

Once again Ambler has, through a series of small but accumulating facts, and the character’s deliberate responses to those facts, created a situation of extreme peril. Although the peril flows directly and logically from those facts and responses, it appears to be sprung on the reader suddenly and alarmingly. Ambler was truly a suspense writer of great skill.

April 9, 2017

42nd Street

For decades it’s symbolized New York City. It’s seen here from the easternmost point, on a terrace in Tudor City, looking west. My noir novel takes a skeptical view of the city, and who rises and who falls, and why. But the street speaks for itself.

[image error]

Max Eastern is the author of the noir thriller The Gods Who Walk Among Us, now on sale.