Rizwan Niaz Raiyan's Blog

October 19, 2025

View from The Hill: Barnaby Joyce is doing again what he does best – disrupting

Barnaby Joyce is a natural-born disruptor. He also always wants to be the head of the pack, and in the spotlight.

As Nationals MP Michael McCormack puts it, “he likes to be in charge, leading, in control”.

Taking into account his character, temperament and circumstances, it is unsurprising Joyce is kicking the Nationals in the shins, stepping out of their party room, and keeping people guessing whether his flirtation with One Nation will turn into a marriage.

Joyce has had two turns at being Nationals leader. Now he is on the backbench, after being confined at the last election to campaigning only in his electorate. He’s angry and upset; he is an open enemy of current leader David Littleproud but hasn’t the clout to replace him.

Joyce invariably lets his emotions hang out, and so it was in his weekend statement to party members, which came after a leak that he was in “advanced talks” to defect to One Nation. The leak caught him on the hop (despite earlier rumours), and the Nationals as well.

“My relationship with the leadership of the Nationals in Canberra has unfortunately, like a sadness in some marriages, irretrievably broken down,” he wrote.

He complained of being off the frontbench, “moved on for ‘generational change’” and “seated in the far corner of the [House of Representatives] chamber”.

“I am seen and now turning into a discordant note. This is not who I want to be”, he said. This overlooks the fact his circumstances in part reflect his own behaviour – he has indeed been a discordant note.

Joyce also pointed to “our position in continuing to support net zero”, with the damage he alleges that causes, “which makes continuing in the Nationals Party Room under this policy untenable”.

That sounds somewhat disingenuous, given the Nationals are reviewing the net zero policy and the signs are they are expected to drop it.

Joyce announced he will not recontest his New England seat but will stay in it until the election. He won’t sit in the Nationals party room, nor, it seems, attend Nationals events – he has pulled out of one he was scheduled for this week.

And then the tease. “I am free now to consider all options as to what I do next.”

Joyce is known to have been having talks with Pauline Hanson for some time, but hasn’t confirmed he will join her.

Hanson has said he’d be welcome and that “he’s more aligned with One Nation than what he is with the National Party”.

Nationals leader David Littleproud has appealed, no doubt through gritted teeth, for Joyce to stay. The departure of Joyce would be the second defection since the election – Jacinta Nampijinpa Price went off to the Liberals. Littleproud can’t be confident of his position and internal disruptions weaken it further. He needs to settle the net zero issue pronto.

Nationals senator Matt Canavan, a close ally of Joyce over the years, said on Sunday he did not want to see him go from the party. “We should do everything we can to keep him as part of our team.”

Canavan said he was “disappointed our former leaders’ skills and experience haven’t been used in a frontbench role or by other means”, and “I’d encourage the leadership to do that”.

In Joyce’s electorate about a dozen Nationals branch members have jumped to One Nation.

More generally, some Nationals sources say there is much discontent in their base, with criticism of Opposition Leader Sussan Ley and people feeling the Coalition is too focused on the cities and trying to win back Teal areas. The frustration was easier to keep in check when Peter Dutton was leader but has broken out under Ley, who has less authority, and with the current soul-searching within the Liberals.

One scenario that’s being canvassed is that if Joyce, 58, joins One Nation, he could succeed the 71-year-old Hanson as leader at some point. (Hanson’s current Senate term expires in 2028.) If he took this course, he could sit as a One Nation lower house member for the rest of this term and then run for the Senate.

There’d be no guarantee such a transition wouldn’t end in tears. Joyce has a strong reputation as a retail politician, but that has been somewhat tarnished in recent years. One Nation is full of many difficult people and is very much tied to Hanson personally. Joyce might not find himself such a good fit.

One Nation’s vote has surged post election, but will it soon peak? While there is support for it on the right and in the regions (and it doubled its Senate representation in May), remember that the Nationals held their own at the election. Many of their voters see their representatives as effective local members.

And then there is the question of how Hanson and Joyce would get on while he was serving his apprenticeship. McCormack (who’s had an up-and-down relationship with Joyce) wonders if it could be like Trump and Musk 2.0. With their volatile personalities, “who’d know whether that would work?”

Michelle Grattan does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

‘Reduce, reuse, recycle’ is corporate gaslighting – the real change must come from the fossil fuel industry

“Reduce, reuse, recycle.” For more than 50 years, those three Rs have been the world’s go-to environmental mantra.

On the face of it, the three Rs sound like an empowering call for each of us to play our part for the planet. However, the individualist approach behind the slogan has come in for increasing criticism by climate change activists.

I am one of them. As a scholar-activist who has spent over 16 years working with climate justice movements, I have studied how movements are challenging the individualistic focus to climate change – an approach that is heavily promoted by corporate public relations campaigns.

Read more: COP28: South Africa pioneered plans to transition to renewable energy – what went wrong

Fossil fuel corporations have worked with public relations firms to convince the public that environmental problems are the fault of consumer behaviour. One of the main aims of these campaigns is to shift attention and blame away from the main actors responsible for ecological destruction – wealthy corporations, polluting industries and the captured governments that enable them.

Individual emissions within the average person’s direct control account for less than 20% of total emissions. The vast majority come from industrial systems and infrastructure beyond people’s control.

The fossil fuel industry’s public relations campaigns also want individuals to focus on their own environmental footprint so that they are distracted from pushing for more structural and policy driven changes. Those structural changes would threaten the profits of the fossil fuel industry.

Read more: Climate justice for Africa: 3 legal routes for countries that suffer the most harm

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the world’s leading authority on climate change, has said that

rapid and far-reaching transitions across all sectors and systems are necessary to achieve deep and sustained emissions reductions.

Compared to the scale of change we need, “reduce, reuse, recycle” falls short.

Building on that evidence, climate ethics literature, and discourse analysis, in a newly published book chapter I argue that it’s past time to go deeper than just the old “Three Rs”. In addition, environmental education should embrace new, more radical mantras that tackle the root causes of our ecological crises, such as Regulation, Redistribution, and Reparations.

These more radical Rs focus on the structural and economic factors that drive ecological crises, working to reorient societies towards more socially and ecologically just ends. Social movements are increasingly realising that we need to focus on such systemic factors, which is part of why the slogan “Systems Change, Not Climate Change” has become such a key rallying call for climate justice movements across the world.

Regulation: reining in pollutersThe first R is regulation – putting in place strong, enforceable rules to rein in destructive industries and hold elites accountable. Corporations have tried to sell the idea that they don’t need to be regulated and that markets will solve the problem. However, despite decades of voluntary corporate pledges, most businesses are far off track.

Read more: Polluters must pay: how COP29 can make this a reality

Recent research into 23,200 companies from 14 industries across 129 countries found that nearly 75% had no official plans in place (climate transition plans) to end their greenhouse gas emissions. Fossil fuel companies are continuing to investing in vast amounts of new oil, gas and coal production – even though the world already has much more fossil fuel than we can burn to avoid climate catastrophe.

Redistribution: funding a just transitionThe second R is redistribution – shifting wealth and resources away from wealthy and destructive industries, towards a more socially and ecologically just future.

Along those lines, South African trade union federations Cosatu and Saftu have proposed progressive taxes on wealth, pollution and financial transactions to fund a just transition for workers and communities. Similar proposals have been put forward in many other countries, including by the Africa Tax Justice Network.

Such progressive taxation is especially key in deeply unequal countries like South Africa, where 10% of the population owns more than 80% of the wealth. Tackling that inequality through fair taxation, divestment from fossil fuels, and reinvestment in community-led projects is essential.

Redistribution can help ensure that the benefits of climate action reach those most affected by the crisis, and help us build a more prosperous, and socially and ecologically just future.

Reparations: repairing and rebuildingThe third R, reparations, recognises that today’s ecological crisis is rooted in centuries of colonial extraction and exploitation.

Africa is the continent least responsible for the climate crisis, yet it experiences countless climate disasters. Therefore reparations should mean debt cancellation, technology transfer, and climate finance from wealthy polluting nations – not as loans, but as debt payments.

Read more: Wealthy nations owe climate debt to Africa – funds that could help cities grow

However, reparations should be about more than just financial transfers. As philosopher Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò argues, reparations are a world-making project. In other words, they can be used to rebuild relationships, communities, societies and ecosystems that were damaged by colonialism, capitalism and environmental racism. Reparations should form the basis of creating new systems based on social and ecological well-being, not exploitation.

What needs to happen nextEven the most diligent recycling or green consumerism simply won’t get us to zero emissions. For example, during the 2020 COVID-19 lockdowns when much of the world stayed home, global emissions fell by only 8%.

That was a large, unprecedented drop. But it came nowhere near enough to get us to the needed goal of net zero or even negative overall human-caused emissions.

None of this is to say that one shouldn’t reduce, reuse, or recycle. However, we must be careful to focus too heavily on individual actions at the expense of structural change.

Read more: Heat extremes in southern Africa might continue even if net-zero emissions are achieved

A similar lesson can be drawn from the history of struggles for racial justice. One of the founders of the Black Consciousness Movement in South Africa, Stephen Bantu Biko, critiqued how some churches, during apartheid, would blame the poor in South Africa for their poverty. The churches said people were poor because they were sinful, not because apartheid had been constructed to exploit people and keep them in poverty.

Likewise, the Three Rs can stigmatise individuals as environmental sinners. This removes the attention from the fossil fuelled economic system that’s driving the ecological crisis.

If educators, activists and concerned citizens want to promote an effective environmental ethic, it is vital to move past a narrow focus on individual actions. Rather than trying to clean up the symptoms of the problem, society needs to tackle the roots of the ecological crises we face.

Dr Lenferna previously served as the elected general secretary of the South African Climate Justice Coalition - a civil society coalition aimed at advancing a transformative climate justice agenda. He also received funding from the National Institute for Humanities and Social Sciences for a post-doctoral research fellowship at Nelson Mandela University where he completed the research for this article.

Should Boko Haram fighters be given a second chance in society? We asked 2,000 young Nigerians

Across the world, the question of how to deal with former fighters remains urgent. From Nigeria and Iraq to Syria and the Sahel, governments are wrestling with how to bring people who once fought for violent groups back into society. Reintegrating ex-fighters – after appropriate punishment – is unavoidable. This is because alternatives such as indefinite detention, capital punishment or abandonment are unsustainable and risk fuelling future cycles of violence.

Yet local communities often seem to resist welcoming ex-combatants back.

How, then, can societies balance the need for reintegration with local resistance?

As scholars of public opinion during and after episodes of political violence, we set out to better understand these tensions. We have years of fieldwork experience in Nigeria and other conflict-affected settings and, together with our local team, we conducted a study to assess citizens’ views on reintegration. How risky would it be to take a certain person back? And does this person deserve a second chance?

Our research was conduced in Nigeria, where Boko Haram’s insurgency has devastated communities for more than two decades. As the group has weakened and thousands of fighters have surrendered, the government has launched programmes to reintegrate them into civilian life. These initiatives have achieved limited success so far, as many citizens remain wary and resistant to their return.

We surveyed around 2,000 young Nigerians and asked them to evaluate different hypothetical profiles of former Boko Haram fighters. This allowed us to see how different characteristics shaped public preferences.

We found that respondents were more forgiving towards former fighters who were forced to join the insurgency and expressed remorse afterwards. They were less willing to reintegrate more militant and less repentant offenders.

Our findings speak to several high-level policy debates today. Nigeria continues to run reintegration programmes. While some returnees have successfully rejoined their communities, others have faced suspicion, threats, and even renewed displacement.

What we foundThree patterns stood out:

Why they joined matters.People were far more open to reintegrating fighters who were forcibly recruited or joined as children than those who joined voluntarily – especially for ideological reasons. As one respondent put it:

Young fighters had little guidance or knowledge of what trouble they were going into.

What they do after leaving matters even more.Former fighters who left voluntarily and took part in reconciliation efforts, especially cooperating with the police or army in their fight against Boko Haram, enjoyed much stronger public support. One respondent even went a step further, suggesting that

instead of a prison sentence, former militias should serve a period of compulsory community service rebuilding the states they have destroyed.

Some atrocities were harder to forgive.As one participant put it:

The only precondition is that they have never taken a life. No killer deserves to be free, let alone get amnesty.

Still, our experimental results show this mattered less than one might expect: while people were reluctant to accept those who committed severe violence, the circumstances of joining and leaving weighed more heavily.

These same patterns also influenced whether people believed reintegration would succeed, and what punishments they thought appropriate. Fighters who were forced to join and left voluntarily were expected to reintegrate successfully and were more likely to be granted amnesty. Fighters seen as willing culprits who refused reconciliation were more often judged to deserve the death penalty.

Importantly, these patterns held broadly across different groups – whether respondents were Christian or Muslim, from the north or south, victims or non-victims of Boko Haram violence.

In short: willingness to forgive depended less on the violence of the past than on whether ex-fighters signalled remorse and a genuine commitment to peace today.

Why this mattersOur research suggests that reintegration and reconciliation is more likely to succeed when:

(1) Clear conditions are set. Linking reintegration to reconciliatory behaviour can reassure communities.

(2) Citizens are informed. Communication campaigns that explain how some fighters were coerced, or highlight the risks taken by those who defected, can reduce public resistance.

(3) Reconciliation is made visible. Publicising ex-fighters’ efforts to cooperate with authorities or support victims helps rebuild trust.

The lesson is simple but often overlooked: preparing societies for the return of ex-fighters is as important as preparing the fighters themselves. Without community buy-in, reintegration risks deepening divides instead of healing them.

Amélie Godefroidt received funding from the Research Foundation Flanders--FWO for this study.

October 18, 2025

A government review wants schools to respond to bullying complaints within 2 days. Is this fair? What else do we need?

Over the weekend, the federal government released its rapid review into school bullying.

Authored by clinical psychologist Charlotte Keating and suicide prevention expert Jo Robinson, the review received more than 1,700 submissions from parents, students, teachers and school staff. The majority were from parents.

Amid ongoing community concerns about the devastating impacts of bullying, what does the review get right? Where are the weak spots?

And is a call for schools to respond to a complaint of bullying in two days reasonable?

What did the review find?The review acknowledges bullying is not a single issue with a single fix. Bullying sits on a continuum of harmful behaviours that cuts across wellbeing, behaviour, attendance, engagement and family functioning.

It also notes students are not the only ones who bully. Sometimes staff and parents are the perpetrators.

The review calls for school cultures that prioritise empathy and kindness – two of the key priorities in our current national education declaration.

The review recommends clear policies and procedures around bullying, simple reporting pathways, and more training for teachers to help them manage their classrooms and deal with bullying.

Is it reasonable for schools to act within 2 days?Many caregivers during the review said they felt nothing happened after reporting concerns to their child’s school. The first casualty of many bullying incidents is the relationship and trust between families and the school.

One of the most prominent recommendations is schools should respond within two school days to a complaint or incidence of bullying.

This requires schools to show they have provided immediate safety measures and started an unbiased investigation. It recognises more complex cases may take longer to resolve, but this initial action is essential.

Setting a predictable two-day clock signals harmful behaviour will be taken seriously and the school will keep people informed as the process unfolds. This is realistic for schools – noting complex cases will take longer to properly resolve.

As the review noted, schools that already do this well have a simple reporting pathway and communication templates. Time is provided for staff to see students outside of class and there are clear escalation routes if concerns are not resolved. There is visible early action so students feel protected and families know what will happen next.

What does the review get right?The review is grounded in research evidence. It acknowledges the multifaceted nature of bullying, puts respectful relationships at the centre, and treats bullying as a whole school community issue. This is what current research suggests is the best way to approach this damaging issue.

It also calls for visible leadership and early action from the school, so trust does not erode while families wait for updates. It backs practical approaches to enable students to support peers and report concerns if they see something wrong.

Importantly, it allows schools to tailor how they work. This is especially important in rural and remote areas where staffing, services and community relationships differ.

Are there risks or weak spots?There is a risk of a “policy pile-on”. Schools are already dealing with a crowded landscape of bullying guidelines and programs. Adding more without pruning or aligning could create confusion and unnecessary extra work for schools, who are already stretched and short on time.

The review notes how data collection could help research and further responses to bullying. But more work is needed here. Tracking and reporting only work if there are shared definitions, data collection infrastructures and clear privacy rules.

Meanwhile, the digital landscape is moving at a rapid pace. Schools also need more guidance on image-based abuse and deepfakes.

What’s missing?We did not hear much about how bullying prevention interacts with existing approaches to students’ wellbeing, behaviour and attendance.

The review could have said more about the tensions between keeping students safe and making sure all students have access to education. Restorative justice approaches within schools, if done well, can help young people understand the impact of their actions.

Families of bullying victims may want to see a perpetrator “expelled” or “suspended”. But research shows this is a damaging approach.

More is needed to spell out what should happen when a matter moves beyond the classroom to school leadership and when it involves external agencies, such as police.

$10 million isn’t muchThe government has announced A$10 million for a national awareness campaign and new resources for teachers, students and parents.

But awareness alone is not enough. Schools need time, coaching and systems that support teachers and professional staff to do the work. So the $10 million is a limited beginning.

More commitment is needed to encourage states and other school sectors to increase funding for dedicated wellbeing roles within schools, data capability, coaching and time for teachers, so any new expectations become routine.

Ultimately, the states and territories are responsible for schools, so let’s hope the joint commitment to address bullying – expressed by all education ministers on Friday – remains central to their planning and funding decisions.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Pennsylvania’s budget crisis drags on as fed shutdown adds to residents’ hardships — a political scientist explains

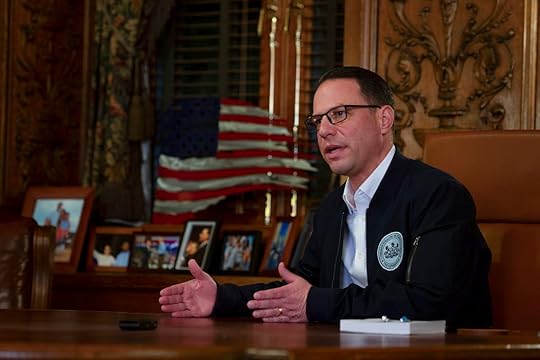

Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro's first budget, in 2023, was not fully passed until mid-December. AP Photo/Daniel Shanken

Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro's first budget, in 2023, was not fully passed until mid-December. AP Photo/Daniel ShankenWhile Americans across the country deal with the consequences of the federal government shutdown, residents of Pennsylvania are being hit with a double blow.

Pennsylvania has been without a state budget for over 100 days – and remains the only state currently operating without a budget.

As a political scientist at Penn State who studies state politics and policy, I see how Pennsylvania’s budget impasse has ripple effects that are compounded by the current budget problems in Washington.

Let’s look at the present budget problems in Pennsylvania and what we can learn from past battles over the state budget.

A double crisisDouble government budget crises, like the one Pennsylvania faces now, are rare. One reason is that 46 states, including Pennsylvania, begin their new fiscal year on July 1. The federal government’s fiscal year begins on Oct. 1. Even a state like Pennsylvania, that has had late budgets for eight of the last 10 years, would have to be very late in passing a budget for it to potentially coincide with a federal budget impasse. And, of course, federal government shutdowns do not happen all the time.

A group of Republican senators talk at the U.S. Capitol Building on Oct. 15, 2025, during a government shutdown that began Oct. 1. Andrew Harnik via Getty Images

A group of Republican senators talk at the U.S. Capitol Building on Oct. 15, 2025, during a government shutdown that began Oct. 1. Andrew Harnik via Getty Images Pennsylvania’s Democratic Gov. Josh Shapiro faces a delicate political environment in Harrisburg – as he has since his first budget in 2023. The Democrats control the state House by a single seat, whereas the Republicans have a comfortable majority in the Senate.

The parties have been debating over the last several budget cycles how to handle funding surpluses – much of which came from Biden-era legislation like the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act – and when and how to deal with the inevitable end to those surpluses.

This year, the two sides are far apart on their views of the proper spending level.

The Democrats in the House passed a US$50.3 billion spending plan, but Senate Republicans want to keep state spending flat at $47.6 billion. The two sides have clashed over proposals surrounding school vouchers, marijuana legalization and more.

As for the federal government, Republicans have a trifecta – control of the White House, Senate and House of Representatives – but do not have the 60 votes in the Senate required to overcome a filibuster. Democrats have dug in over reversing cuts to health care from the earlier passed “one big beautiful bill” and expiring Obamacare subsidies.

There is little sign of an immediate end to either impasse.

In Pennsylvania, there is growing frustration on both sides about an inability to compromise. Nationally, House Speaker Mike Johnson has speculated that this may end up being the longest federal government shutdown in history. In neither case, though, does there seem to be a great deal of urgency in coming to a compromise.

Effects on PennsylvaniaThese dual crises are affecting Pennsylvanians in many ways. The state government continues to function even without a budget, but counties, school districts and nonprofit organizations that rely on state funding are being forced to make difficult operating choices.

Some counties like Westmoreland and Northampton are beginning the process of furloughing employees. School districts are taking out loans, freezing hiring and deferring spending. The state already owes school districts more than $3 billion in missed payments for the past three months.

Cozy Wilkins, 66, stocks the shelves at New Bethany, a nonprofit that provides food access, housing and social services, in Bethlehem, Pa., on July, 22, 2024. Ryan Collerd/AFP via Getty Images

Cozy Wilkins, 66, stocks the shelves at New Bethany, a nonprofit that provides food access, housing and social services, in Bethlehem, Pa., on July, 22, 2024. Ryan Collerd/AFP via Getty Images The social safety net is also fraying as social service organizations, like rape crisis centers and mental health providers, are also expending reserves, taking out loans and furloughing employees.

Then comes the federal shutdown.

Military families nationwide have been hit particularly hard, with many turning to food pantries to help meet their needs. The recent money maneuvers at the Department of Defense to pay active-duty and activated National Guard and Reserves personnel is temporary. The commonwealth also has the eighth-highest population of federal civilian employees, at over 66,000 who are not being paid.

Services like food banks are especially vulnerable in this situation, as they are seeing greater demand – which may increase due to federal workers going unpaid – but rely on both the state and federal governments for subsidies. Just this week, it was announced that Pennsylvanians buying health care through the state’s Affordable Care Act marketplace for 2026 should expect a 22% increase in premiums, on average. Part of that increase is due to expectations around the expiring Obamacare subsidies at the center of the Democrats’ demands in this shutdown.

All of these forces are coming together to pinch Pennsylvania residents.

Echoes of the pastWhile the compounding pain of the federal shutdown is unique, long budget delays in Pennsylvania are not.

In 2023, Gov. Shapiro’s first budget was not fully passed until Dec. 14. That budget was fundamentally delayed by the acrimonious implosion of a deal on school voucher spending between the governor and Senate Republicans. The budget negotiations ended after some horse-trading on specific programs, like removing the popular Whole-Home Repairs Program started during the COVID-19 pandemic but adding funding for lead and asbestos abatement in schools.

The difference between then and now, however, is that back then the governor and General Assembly agreed on the overall budget, but typical bargaining was needed to get the votes needed to pass the spending bills after the voucher blow-up. This time, the parties are almost $3 billion apart in what should even be spent.

In the end, however, both Pennsylvania and the federal government will pass budgets, and I expect that each will be the result of protracted negotiations over multiple spending items, as Americans have seen in the past. The question is: How much pain will citizens, nonprofits and local governments face in the interim?

Read more of our stories about Philadelphia and Pennsylvania, or sign up for our Philadelphia newsletter on Substack.

Daniel J. Mallinson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

October 17, 2025

How ‘conflict-free’ minerals are used in the waging of modern wars

Minerals such as cobalt, copper, lithium, tantalum, tin and tungsten, which are all abundant in central Africa, are essential to the comforts of everyday life. Our phones, laptops and electric vehicles would not function without them.

These minerals are also tied intimately with conflict. For decades, military and paramilitary violence in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and on its borders – particularly with Rwanda – has been shaped and financed by control over some of these sought-after commodities.

Many of these minerals, including those that have supposedly been sourced responsibly, are linked to violence at the other end of the supply chain too. As we found in our recently published research, minerals sourced in central Africa play a crucial role in the waging of modern wars.

The eastern provinces of the DRC hold large mineral reserves, but mining there remains fraught with the involvement of armed groups. gt29 / Shutterstock

The eastern provinces of the DRC hold large mineral reserves, but mining there remains fraught with the involvement of armed groups. gt29 / Shutterstock Extensive campaigning and lobbying over the past two decades has focused on the idea of “conflict-free minerals” as a way to address links between extraction and armed conflict in mining regions.

This has resulted in a suite of legislation in the EU and US obliging tech manufacturers that use minerals from the DRC and surrounding countries to submit so-called “conflict minerals reports” to national authorities.

In the US, for example, tech firms file what is known as a “specialized disclosure form” to the Securities and Exchange Commission detailing all sources of four key minerals commonly associated with conflict in Africa: tantalum, tin, tungsten and gold.

The form requires a declaration that trade is compliant with the due diligence guidelines set by the OECD on responsible supply chains in the DRC and neighbouring states. This guidance has, in turn, given rise to an industry of regulators that seeks to ensure minerals connected to conflict do not enter supply chains.

Tech companies worldwide – big and small – now comply with conflict minerals policies. The fact that these firms can be held under a critical spotlight, and that attention is falling on how bloody wars are connected to consumer products, is a positive development. But there are many flaws to this system of accountability.

One issue is the difficulty in proving that mineral supply is truly conflict free. Many of the “conflict-free” minerals sold through Rwanda, for instance, are very likely to have at least some connection to war.

In the early 2000s, when Rwandan forces were involved in armed conflict in the DRC, the UN estimated that the Rwandan army controlled between 60% and 70% of all the coltan (tantalum ore) produced there. It is widely accepted that Rwandan influence has persisted in the DRC since.

Another issue is that, under conflict-free mineral legislation, “conflict” is associated with minerals only at source. There is no oversight on how minerals are connected to conflict at the other end of supply chains in modern weapons of war.

Conflict mineralsWeapons are no longer fashioned only with lead, iron and brass. They now depend on a range of advanced technologies: lithium batteries, cobalt cathodes, tantalum resistors, nickel capacitors, tin semiconductors, tungsten electrodes and so forth.

In fact, everything advanced militaries do nowadays – whether it involves a fighter jet, drone, guided bomb, smart bullet, night vision or remote sensing – utilises these components.

As we outline in our study, conflict-free minerals are essential to the waging of modern wars. We traced the movement of ores from the DRC into Rwanda, from where they are then sold to some of the world’s largest weapons makers as “conflict-free” minerals.

A coterie of defence contractors source minerals via this route. These minerals, as our previous research shows, are used as “volumetrically minor yet functionally essential” ingredients of the products these firms sell to militaries worldwide.

To draw focus on two “conflict-free” minerals traded through Rwanda, tin and tantalum are vital to the function of a wide range of military wares. According to the US defence department, tin is present in “nearly all military hardware”.

It is crucial in compound forms to defrost screens at high altitudes and to deflect radio waves to enhance stealth. Tin is also used to power the Joint Direct Attack Munition guidance kits that improve the accuracy of bombs.

Tantalum-based semiconductors comprise the basic circuitry of drones. And among other things, tantalum is the active adsorbent material in the infrared camera tubes that make night vision possible. High-tech wars cannot be fought without these minerals, which are traded under conflict-free mineral legislation.

A Ukrainian soldier programmes a drone in the Donbas region of eastern Ukraine. Jose HERNANDEZ Camera 51 / Shutterstock

A Ukrainian soldier programmes a drone in the Donbas region of eastern Ukraine. Jose HERNANDEZ Camera 51 / Shutterstock Researchers have long suspected that minerals can never be conflict free at source. But our findings now turn attention to the other end of the supply chain. If it is to have any purchase at all, the idea of “conflict-free” minerals must be entirely refigured.

Virtually all commentary by journalists, lawyers and scholars focuses narrowly on consumer technologies, with the injustices faced by mining communities in central Africa contrasted with phones and electric vehicles. The source of minerals is the sole focus of ethical scrutiny.

This is an important aspect of minerals supply chains. But there is a growing prominence of other tech companies, in the form of modern weapons manufacturers, whose customers are not the global masses but the militaries of the world’s most belligerent states.

Companies like Elbit Systems – which did not respond to The Conversation’s request for comment – present themselves as complying with ethical standards.

In its 2020 conflict minerals report, Elbit declared a corporate stance against “human rights abuses and atrocities”. It also expressed a commitment “to sourcing materials from companies that share our values with respect to human rights, ethics and environmental responsibility”.

Yet, as our research shows, some companies are sourcing minerals from one war zone and then making profit from another. It should be recalled that Elbit, for example, supplies “hundreds of products” to Israel’s defence ministry.

There needs to be more scrutiny on the use of minerals “downstream” to stem the flow of the raw materials that propel wars in Gaza and beyond.

The research mentioned in this article was published as part of ‘War and Geos: the Environmental Legacies of Militarism’ (UKRI Horizon Europe grant number EP/X042642/1 (awarded as a European Research Council Starting Grant)).

Mohamed El-Shewy does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Sam Fender wins Mercury prize: ‘Geordie Springsteen’ is voice of a UK ravaged by industrial decline

The Mercury prize almost always produces surprises – among them, Gomez not The Verve in 1998, and English Teacher not Charlie XCX in 2024 – but perhaps the biggest surprise is that the prize has survived for so many years. That it has been won this year by Sam Fender in his native Newcastle speaks very much of the time that has passed in those 34 years.

Conceived as a kind of credible alternative to the Brit Awards – a prize for those beyond the razzamatazz of mainstream pop music – the (then) Mercury Music prize was introduced in 1992.

This was the year of a general election which, while won by the Conservative party, did not see the re-election of Margaret Thatcher. But Thatcher’s work had been done: the introduction of neoliberal policies which ravaged many UK industries and the regions in which they were located.

Fender can be understood as a voice of that ravaged Britain. He was born two years after John Major’s election victory, and grew up in a disintegrating family in a disintegrating former industrial region. He survived the chaos and has written about that collective suffering with great skill and passion over three albums.

It is telling, too, that the (renamed) Mercury Prize lost its corporate sponsorship along the way. Being publicly allied with music is no longer the marketing “must have” it once was. This year’s award event was paid for jointly by Newcastle City Council and the regional authority.

As Britain attempts to cope with the evaporation of major industries and the suffering that permanent loss of employment infrastructure induces, many UK regions now foreground the creative abilities of their residents as a reason to invest in their particular area. Demand for music, and for the creativity it carries and expresses, has become a key feature of social and economic as well as cultural life.

This begs the question: what is it that creative people actually contribute? The 2025 Mercury prize shortlist gives us some clues, especially if we look at three of the nominees who missed out on the prize: Pulp, Wolf Alice and Martin Carthy. Both Pulp and Wolf Alice are previous winners (1996 and 2018 respectively), but Carthy has won very few awards over the 84 years of his life.

“Notable” musicians tend to be of their time. This is partly because their choice of instruments and combinations of keys, notes and tempos resonate with the moments they and their audiences are living through. But there is more to being a musician than this.

Real, affecting performance draws on and mobilises symbolic information far beyond musical soundmaking – even though that demands skill and ability. Fender, for example, is unequivocally a Geordie, even as he fits the mould of a kind of Bruce Springsteen for his times.

Both Pulp and Wolf Alice are challenging to discuss. Where Jarvis Cocker is concerned, the word “uncompromising” comes to mind, but what does that mean? Here is someone who is unique – yet what his vision of the world is, is never quite apparent. Cocker is “about something”, and he is about it so strongly that people stand back and admire him for it.

Wolf Alice are something different: a successful rock band in a time when rock bands have gone into decline. It is almost the band’s own self-awareness that, somehow, “they shouldn’t be” that gives them their energy – mining rock’s extensive back catalogue to support essentially introspective lyrics about (mainly singer Ellie Rowsell) self-adjusting to the demands of an evermore turbulent world.

In this, there are shades of Cocker. And with Fender singing about negotiating this turbulence too (only with a more explicit set of references to a world beyond his interior), so the core strengths of contemporary music begin to emerge.

Popular musicians go on providing a soundtrack for our lives because they express themselves through the idioms of the moment. If we take Fender’s previous album, Seventeen Going Under, as a point of reference, every aspect of the recording and its video speaks to his growing up in the northeast of England and his continuing loyalty to the place.

His moving acceptance speech and rapport with the audience were evidence of this. His performance of People Watching was almost pure Bruce Springsteen – mainstream rock inflected and defined by a hometown sensibility.

Which brings us to Martin Carthy. It is impossible to capture Carthy’s significance in words, because his voice cannot be heard on the page – and it is so powerfully distinctive that it needs to be heard.

Carthy was the soul of English folk music in the 1960s and ’70s. His brand of folk music speaks to a resilience through suffering – the suffering of pre-industrial society articulated through song. Now, Fender is speaking to the suffering of post-industrial society. They both should have won.

Mike Jones does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The fungi living in the body play an important role in health – here’s what you should know about the ‘mycobiome’

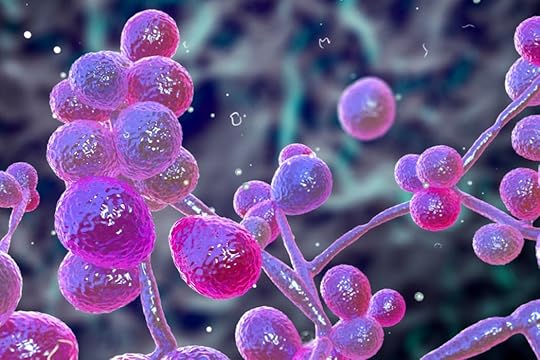

The most common fungal species found in our mycobiome are yeast from the _Candida_ family. Kateryna Kon/ Shutterstock

The most common fungal species found in our mycobiome are yeast from the _Candida_ family. Kateryna Kon/ ShutterstockThe “gut microbiome” has become a popular health term in recent years. It’s easy to see why, with an abundance of research showing how important the trillions of microbes living in our gut are for health.

But what many people might not realise is that the microbiome doesn’t only contain bacteria. It also contains other types of microbes – including fungi. The fungal component of the microbiome is called the “mycobiome”.

Although the mycobiome has been less well studied than its bacterial counterpart, recent research shows it’s sensitive to diet and may affect our health, too.

The best studied mycobiome is the one in our intestines. It’s composed of many fungal species. The most common fungal species found there, particularly in the Western world, belong to the Candida family.

Candida are a type of yeast. For most of us, the Candida population in our mycobiome is kept in check by our immune system and our gut bacteria. But changes to either of these can cause populations of Candida to expand in the mycobiome. This can be a problem, because Candida may cause life-threatening infections in people with damaged immune systems.

For example, research found that hospital patients who are given antibiotics are more likely to develop Candida infections.

This is partly explained by the effect of antibiotics, which kill off certain species of gut bacteria that compete with Candida for space and resources within the intestine. Antibiotics have also been found to directly alter our immune cells and how they fight fungal infections.

Another study, which analysed the mycobiome of cancer patients, found that those who developed serious Candida infections had an overgrowth of the fungus in their mycobiome just before the infection started. Combined with the damaging effects of chemotherapy on the immune system, this made it harder for patients to fight off the infection.

Disruption in the mycobiome’s Candida balance has also been linked to several other diseases. For instance, Candida levels are high in patients who are critically ill. This suggests that too much Candida in our guts is a sign of poor health.

Changes in the fungal mycobiome have also been linked to several gut diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease. Research on Crohn’s disease has also shown that patients have an overgrowth of Candida. These fungi also produce toxins that irritate the gut lining, which could potentially explain some of the symptoms Crohn’s patients experience.

High levels of Candida in the gut can activate immune cells as well, making them more inflammatory. This has been seen in patients with severe COVID-19.

Mycobiomes in the bodyThe mycobiome isn’t only found in our gut.

We also have a skin mycobiome. In fact, the skin between our toes contains a more diverse number of fungal species than any other skin mycobiome.

The skin mycobiome is mostly dominated by a fungus called Malassezia. This yeast has adapted to grow on the skin’s surface.

Malassezia can activate the immune cells that reside between the skin’s layers. This may lead to inflammation linked to skin disorders, such as psoriasis and eczema.

Eczema is linked to the skin mycobiome fungus Malassezia. Ternavskaia Olga Alibec/ Shutterstock

Eczema is linked to the skin mycobiome fungus Malassezia. Ternavskaia Olga Alibec/ Shutterstock Candida auris is also a cause for concern. This fungus is resistant to many antifungal drugs, which is why it can be a problem if it grows on the skin’s surface. In a hospital or emergency room, this could be dangerous – particularly to patients who have immune system problems.

Women also have a mycobiome within the vagina. Its balance with the bacterial communities living there can be a big determinant for vaginal health.

One of the most common fungal infections globally is vaginal candidiasis (thrush). It can cause symptoms such as intense itching, pain and swelling. Many adult women will experience at least one thrush infection in their lifetime.

The source of thrush is another fungus from the Candida family: Candida albicans. This is a common member of the vaginal mycobiome.

The vagina’s microbiome is normally dominated by the bacteria Lactobacillus which help keep Candida populations in check. But if the balance between bacteria and fungi gets disrupted (for example, by antibiotics), the fungus can overgrow or produce inflammatory molecules within the vagina. This inflammatory response is responsible for common thrush symptoms such as redness and itching.

Probiotics may help to restore the balance between fungi and bacteria to prevent vaginal yeast infections – although this has had limited success so far. Some new treatments that target inflammation-causing fungal molecules have shown promise in animal models and in small numbers of women.

There’s good evidence to suggest we might also have a mycobiome in the lungs and in breastmilk.

Controversially, some have even suggested that we may have small numbers of fungal cells in the brain – and these fungal cells may be linked with neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinsons and Alzheimer’s.

Autopsy studies have found evidence of fungi in the brains of people who died from brain disorders – but this doesn’t prove the fungi caused their illness or that it was there during their life.

Experimental studies in mice have also shown that small numbers of fungal cells can survive in the brain for long periods of time – and the presence of these fungal cells was linked with reduced memory function.

Experiments in flies have also shown fungi may travel to the brain and affect function. This is the best evidence we currently have showing small numbers of fungi may get into the brain and survive long-term.

Whether this occurs in people, and if this would be considered a true mycobiome, remains to be proven.

There’s still much we don’t know about the mycobiome. But with continued research in this area we may soon better understand the mycobiome’s importance in our health and how we can nurture and care for it.

Rebecca A. Drummond receives funding from the Medical Research Council, the Wellcome Trust and the Lister Institute for Preventative Medicine.

Rise in youth mortality fuelled by mental illness, drugs, violence and other preventable causes

In some regions, youth mortality has actually risen in the past decade. KieferPix/ Shutterstock

In some regions, youth mortality has actually risen in the past decade. KieferPix/ ShutterstockGlobal mortality continues to fall. Life expectancy has improved to unprecedented levels and deaths in young children have plummeted. Yet for adolescents and young adults, especially those aged 15 to 24, little progress has been made according to data from the latest Global Burden of Disease study. In parts of North America and eastern Europe, mortality in those aged 15-24 has actually risen in the past decade.

This latest study also showed the main causes of death among young people aren’t disease or poor health. The main causes were shown to be injury, violence, suicide, road traffic accidents and substance abuse.

This shows us that health systems worldwide are still ill-equipped to prevent or intervene effectively in social and structural causes of youth mortality.

The Global Burden of Disease study is one of the largest studies on the picture of health, disease and mortality worldwide. The study analysed more than 310,000 data sources collected between 1950 and 2023 from 204 countries. Using death registries, censuses and household surveys, the research team estimated age-specific mortality trends across the lifespan.

The overall picture is one of uneven progress.

For children, especially in low and middle-income countries, vaccines, improved sanitation and better nutrition have saved millions of lives. In east Asia, for instance, mortality in under-fives fell by 68% between 2011 and 2023.

For older adults, the global mortality rate declined by 67% between 1950 and 2023, thanks to better screening, medication and chronic disease management.

Deaths from cardiovascular disease (the leading cause of death globally) have also improved substantially. But cardiovascular disease and other non-communicable diseases (such as cancer and diabetes) still account for nearly two-thirds of all deaths ariund the world.

For young people aged 15-24, the risk profile was different. For them, the main causes of death were primarily preventable ones.

In North America, deaths among people aged 20 to 39 rose by as much as 50% in the past decade – largely due to suicide, drug overdose and alcohol-related harms. The picture was also similar in some parts of Latin America.

But in other parts of the world, such as sub-Saharan Africa, infectious diseases (such as as tuberculosis) and unintentional injuries were the main drivers of youth mortality.

The study also highlighted stark inequalities in mortality risk for youth from marginalised, low-income or Indigenous groups. For instance, the study found that mortality in young women aged 15-29 living in sub-Saharan Africa was 61% higher than previously estimated, mostly due to maternal mortality, road injuries and meningitis.

However, these groups remain systematically underrepresented in global health datasets. The study found that more than 80% of countries lacked nationally representative data across key health domains, including mental health and child health. This meant most of the data was drawn from high-income regions.

Latin Americans, for example, make up over 8% of the global population but represent less than 1% of some global reference datasets. Such a systemic lack of representation from these groups renders their health needs invisible – including the health needs of those affecting the young.

Emerging trendsToday’s young people face unprecedented economic insecurity, social volatility, violence and pressures from social media – all of which can have an extraordinary toll on both mental health and wellbeing.

The mental health needs of young people must urgently be addressed. New Africa/ Shutterstock

The mental health needs of young people must urgently be addressed. New Africa/ Shutterstock Mental health challenges underlie many of the leading causes of adolescent death reported in the study. It’s clear from this and other studies that youth mental health urgently needs to be addressed.

For instance, research from Spain which looked at over 2 million adolescent hospitalisations between 2000 and 2021, found admissions for mental health conditions more than doubled – surging especially after the COVID-19 pandemic.

For teenage boys, substance use, ADHD and psychosis were the most common causes of hospitalisation. For girls, eating disorders, anxiety and depression were more prevalent.

A related study found admissions for adolescent anorexia nervosa rose by almost 90% after 2020 – with cases overwhelmingly concentrated in girls aged 13-17.

Health survey data from 2023 also showed that half of US young adults aged 18-24 reported experiencing symptoms of anxiety or depression. Additionally, a separate US survey also found that more than one-third of 18-24-year-olds reported they’d recently thought about self-harm or suicide.

Other factors which may also have contributed to high youth mortality rates may include a historical lack of preparedness by health systems in focusing on adolescent health issues, as well as a lack of interventions aimed at reducing the actual leading causes of youth death (such as road safety, violence prevention and meaningful mental health care).

The response to youth mortality cannot be medical alone as the leading causes of death in this age group require interventions that sit outside healthcare and require coordination across sectors.

Data systems must also change. Youth from low-income countries, Indigenous people and marginalised groups are underrepresented in research. This means we don’t fully understand the needs of these groups and the problems they face – making it difficult to plan and implement effective interventions.

Youth health must be re-framed as an equity issue, as well. The current model treats young people as responsible for their own poor outcomes, when research shows that, overwhelmingly, these issues can be caused by conditions that young people do not control: poverty, exposure to violence, unsafe road environments, inadequate mental health services and lack of economic opportunity.

These deaths are preventable. We cannot celebrate global health gains when youth mortality is stagnant – and even worsening in many parts of the world. Preventing adolescent and young adult deaths is the next frontier for a fairer, healthier future.

Manuel Corpas does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Our research shows COVID-19 made people appreciate street cleaners more – but it also made their lives harder

In the early days of the pandemic, “solidarity” became a buzzword. As COVID-19 appeared to directly threaten us all, the UK celebrated its key workers who were keeping the country running.

This idea ran through discussions on TV and on social media. The Clap for Our Carers movement had people gathering outside on their doorsteps, applauding, ringing bells, chanting and banging on pots and pans to signal their support.

As a result, the collective reliance on various workforces, such as carers, street cleaners, refuse collectors and supermarket workers, to name a few, became increasingly transparent. Public demonstrations of solidarity with these workers gave the initial impression that the status we attach to such work might be revalued: instead of the low status to which these jobs were assigned before, COVID-19 underlined how essential they are.

However, our research on refuse workers shows that this has not translated into a permanent reevaluation of the benefit key workers bring. On the contrary, instead of a collective shift towards real social solidarity, the pandemic has exacerbated socioeconomic divisions.

Cleaners worked hard to keep infection at bay. G Torres/Shutterstock Unexpected visibility

Cleaners worked hard to keep infection at bay. G Torres/Shutterstock Unexpected visibilityBetween the UK’s first and the second lockdowns in 2020 and again, in the period after the end of the second lockdown in 2021, we interviewed 41 council workers involved in waste management across four sites in London and south-east England. Two were sites where we had previously conducted ethnographic research among street cleaners and refuse collectors.

We wanted to investigate if, and how, the pandemic affected the way that key workers involved in waste management are recognised. We asked our interviewees to reflect on and compare their experiences of working before, during and after the lockdown. We wondered whether they had noticed any changes in their interactions with the public and how they thought these developments might affect them in the future.

We found that the pandemic gave these workers moments of unexpected visibility and recognition. Not only did this show, to their minds, increased public respect, it also gave them hope that social bonds between workers and the public might be strengthened in the long term. They saw the possibility of a novel, yet seemingly mutual acknowledgement and respect. As Keith, one of our interviewees, put it:

During the pandemic we’re part of it, yes … it’s kind of like the police, the fire brigade, the ambulance, the hospitals, it’s part of the services of a community, working to keep the community functioning, and what we do is part of that.

And yet, this experience of coming together was eroded by the unequal consequences of the pandemic for different social groups. Our participants spoke of the differences they saw in people’s ability to distance themselves from the unpleasant or potentially dangerous aspects of the pandemic.

Whereas these workers still had to go to work everyday, other people did not. Our interviewees also noted the stark gap separating those key workers who performed the riskiest jobs (nurses, carers) and those whose jobs involved little risk and could be undertaken from home.

Another interviewee, Kevin, who works as a dustcart driver said:

COVID’s still going on now, because we’re not out of it yet. But, still, they’ve just carried on as their normal day, stayed at home working, while the likes of me go out there all day. And if I don’t work, I don’t get paid.

This chimed with what Nigel, a litter picker, reported:

They’re at home, comfortable. We get nothing. No nothing. Not even ‘Oh, we’ll give you a couple of days, like a couple of days extra as your holiday so you can recover and that’, nothing.

The pandemic also made broader social divisions more tangible. Our interviewees spoke about those with privilege seeming to lack interest in knowing about the deteriorating living conditions of workers like themselves. This was despite the fact that the activities these workers were doing, like waste collection and street cleaning, were vital for societal functioning. Another litter picker, Bernie, put it plainly:

You see people, you see some people going and spending like £12, £16 a day just on food going and buying lunch, and I sit there and I think: ‘How the hell do you do it?’ Nine times out of ten I have to make lunch just buying basics, you know, like a cheap loaf of bread, cheap bit of meat – luxury is a bit of sauce. They don’t want to think about people like me.

This illustrates the oxymoron of being “visibly invisible”. During the pandemic, keyworkers’ effort became more apparent. At the same time, they sensed little desire from the wider public to consider and challenge the cultural and socioeconomic factors that were negatively affecting their lives.

Our findings chime with research on how nurses, too, experienced the pandemic, with comparable levels of scepticism with regards to positive, long-term transformations. The question is whether, as German sociologist Andreas Reckwitz has argued, we are witnessing an increasing polarisation between different groups and social classes. Our research suggests that the sense that the world can be improved and society become more progressive feels ever more remote.

This has worrying implications for societal solidarity. As inequality grows, the mutual obligations citizens might have towards one another are increasingly being eroded.

All names have been changed to preserve interviewee anonymity.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.