Bernie MacKinnon's Blog - Posts Tagged "chester-a-arthur"

Nerding Out With Chester A.

Tomorrow marks the 150th anniversary of Lincoln's transcendent Second Inaugural Address. I've just read an absorbing series of articles in Smithsonian magazine about the Lincoln assassination and things related. But the leader I'm writing about here is not Lincoln and not what you'd call a household name.

This past Presidents Day (Feb. 16) brought to mind an NPR-sponsored contest I entered in the fall of 2012, "3-Minute Fiction: Pick A President." Contestants were told to submit a 600-word entry—about 3 minutes' reading time—focusing on any U.S. President, even a fictitious one. Over the weeks they read some of the entries on-air or posted them on the NPR site and I enjoyed all of them. The winner in the end was very good and quite original, featuring a man whose dementia-plagued father believed that Spiro Agnew had succeeded Nixon as President.

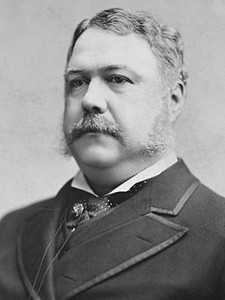

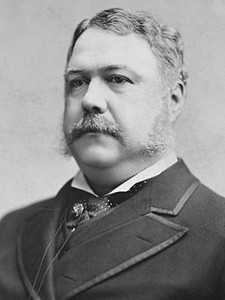

My submission was probably doomed to obscurity when I decided that it should be about our 21st President, Chester Alan Arthur. Why did I do this? Why did I pick my man from the gray middle of the pack—a virtual guarantee that it would be like throwing a jellybean into the Grand Canyon and waiting for an echo? The answer is straight from History Nerd Central: I am a champion of Chester A. I think he was a decent guy who made the best of a daunting situation. And I think he belongs farther up the rankings than historians often place him.

Chester A. Arthur, 21st President

of the United States.

(Courtesy: Library of Congress)

In the giant shadow of Abraham Lincoln, in a landscape gibbering with the ghosts of over 700,000 dead—and with the failure of Reconstruction, the maw of Jim Crow opening wide—post-Civil War politics seemed overpopulated with men who were bitter, vengeful, venal, corrupt and small. As far as Presidents go, many of us tend to think of the 36 years between Lincoln and the bright comet of Teddy Roosevelt as a kind of trough. Given this, it is surprising to actually look at who got into the Executive Mansion. Apart from Andrew Johnson and Benjamin Harrison—consistently rated as bottom-feeders—the United States was lucky to have these men available for the office. A few like Arthur were natural administrators; others like Ulysses S. Grant were not, but at least showed themselves to be fundamentally good and honest. It could definitely have been worse, as Johnson and Harrison abundantly proved.

Arthur was born in Fairfield, Vermont in 1829. His Irish-born father was a teacher-turned-minister and bedrock Abolitionist. Arthur (whose family always called him "Alan") started out as a teacher but ultimately switched to the law and New York City. Upon his admission to the bar, he joined the firm of the Abolitionist lawyer and family friend Erastus T. Culver, who then made him a partner. He lost no time distinguishing himself, helping to win the Lemmon v. New York decision, which established that any slave transported to New York State was automatically free.

Soon afterward, in 1854, Arthur served as lead attorney for Elizabeth Jennings Graham, a black schoolteacher and church organist. Late for service one Sunday, Graham had boarded a New York City streetcar which turned out to be whites-only. The conductor ordered her off but she insisted on her right to ride. Only after putting up an impressive physical fight with the conductor and a policeman before a hostile crowd was she forced off the car. It should perhaps have been clear right then that they had messed with the wrong church lady—but it definitely became so when Arthur took up her case. (Something else that might have made them think twice: Graham was the daughter of wealthy clothing store owner Thomas L. Jennings, founder of the Abyssinian Baptist Church and also the Legal Rights Association, which targeted racist statutes.) The next year—a full century before Rosa Parks—Arthur won Graham's suit against the conductor, the driver and the Third Avenue Railroad Company, which then had to desegregate its streetcars. Thanks in large part to the decision, all of NYC's public transit services were desegregated by the end of the Civil War. Elizabeth Graham went on to found the city's first kindergarten for black children.

Elizabeth Jennings Graham (1827-1901), civil

rights heroine and successful Arthur client.

(Courtesy: Kansas Historical Foundation)

By the time of the Civil War, Arthur had his own law practice, was deeply involved in Republican politics and married to the Virginia belle Ellen "Nell" Herndon, daughter of naval officer and explorer William Lewis Herndon (who was lost in the sinking of the SS Central America in 1857.) In 1861 the governor of New York assigned Arthur to the state's quartermaster department with the rank of brigadier general. He was so effective at housing and equipping the new troops that deluged NYC that he was soon promoted to inspector general and then quartermaster. He would have gone to the front as a regimental colonel if not for the governor's personal plea for him to maintain his home-front role. Yet that role was a political appointment and when the Democrats took over state government in 1863, Arthur lost his post.

Soon after this, he and Nell suffered the death of their three-year-old son William from illness. Nell gave birth to another son, Chester Alan Jr., the following year. In their ongoing grief over William, they heaped indulgence on young Chester, who grew up to be a rich, idle, attention-loving playboy. In 1871 they had a daughter, Ellen, who would lead a much lower-profile life. That same year saw Arthur named Collector of the Port of New York—a federal appointment and a highly lucrative one, typifying the spoils system and its routine rewards for political loyalty. It was a corrupt system, though then fully legal and Arthur personally quite honest. By the mid-1870's, however, the fever for civil service reform threatened to split the Republicans between the reform-minded "Half-Breeds" and the more traditional and complacent "Stalwarts," with the political machine of Senator Roscoe Conkling (Arthur's friend and patron) embodying the latter. The conflict resulted in President Rutherford B. Hayes sacking Arthur in 1878, an experience that left Arthur feeling branded as corrupt.

Arthur's ever-increasing work for the Conkling machine led to late nights and long absences, which strained his marriage. He was away in Albany in January 1880 when Nell died of pneumonia at age 42, causing him a sense of guilt that never quite abated. Within a year of this, he was catapulted to the Vice Presidency of the United States. The tumultuous 1880 Republican convention ended up nominating the "dark horse" (compromise, unforeseen) candidate James A. Garfield of Ohio for President. A champion of the Half-Breed faction, Garfield sought to mend the party split by choosing the Stalwart Arthur as his running mate. Arthur readily accepted the offer despite Conkling's urging that he not. His role in the election proved crucial, as the Republicans won by a wafer-thin 9,070 in the popular vote.

Ellen "Nell" Herndon Arthur (1837-1880), wife of Chester

A. Arthur. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

Arthur and Garfield immediately became estranged, however, over the latter's resistance to appointing Stalwarts to important posts. Arthur was in Albany on July 2, 1881, when he heard that Garfield had been shot and grievously wounded on a Washington railroad platform. Most unfortunately for Arthur, the assassin Charles J. Guiteau had declared on the spot, "I am a Stalwart, and Arthur will be President!" Never mind that Guiteau (often described as "a disappointed office-seeker") would make Booth and Oswald look like poster boys for mental health—the statement stoked public mistrust of Arthur, due to his background in urban machine politics.

Over the terrible eleven weeks that it took President Garfield to die, Constitutional constraints and Arthur's reluctance to seem presumptuous re: presidential authority (he stayed the whole time in NYC) created a power vacuum, ending only with Garfield's death on Sept. 19. And here I must say—the full tragedy of James Garfield's murder is lost on us today. He was smart, honest, gutsy, highly competent and a talented orator. Though President for only six and half months, the final two and a half spent bedridden and in pain, he had shown himself to be a quality leader, one who belonged in high office. As a for-instance, his feeling for the plight of African Americans was genuine, his intentions for them heartfelt without being especially naive; he in fact appointed a number of them to prominent posts, at a time when it was increasingly risky to do so. The tragedy would have been compounded had an Andrew Johnson been waiting in the wings to assume power. Luckily for all of us, though, it was Chester A. Arthur.

Widespread skepticism greeted Arthur's swearing-in. He came to the office with one of the slightest resumes in Presidential history. Malicious rumors were circulated that he had been born outside of the U.S. (sound familiar?) and was therefore ineligible for the Presidency. One by one, cabinet members—looking askance at this accidental President, and mindful of their careers—resigned and had to be replaced. Only the Secretary of War, Robert Lincoln (son of Abraham), stayed on for all of Arthur's term. A great many people expected Arthur to act like a creature of the spoils system, a typically corrupt big-city politician—but that is not how he acted. He embraced the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act, which stipulated that government jobs be offered on the basis of competence and not political patronage, that competence be rated by competitive exams, and that a United States Civil Service Commission be created to oversee the process. Arthur signed it into law in January, 1883, and it proved the central attainment of his Presidency. It raised the ire of his old friend Conkling, who had of course wanted machine politics to continue as ever (Conkling called it the "Snivel Service Act"). And old New York cronies came away disappointed when they approached Arthur for favors.

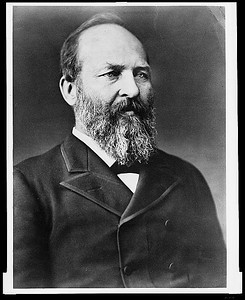

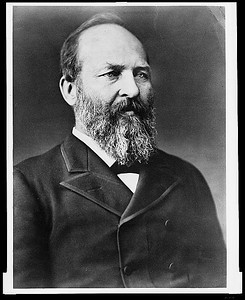

James A. Garfield, 20th President of the

United States and its second to die by

an assassin. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

Arthur also did much to revive the moribund U.S. Navy by pushing to fund the construction of steel-plated vessels. On other fronts, results for his administration were more mixed and frustrating. Arthur had the courage to veto the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which included a 20-year ban on immigration from China and denied citizenship to Chinese immigrants. But when the ban was cut to ten years, he grudgingly signed the bill, knowing that another veto would be overridden and weaken his Presidency. In the area of Civil Rights, he sought to combat the reemergence of the Southern Democrats and their disenfranchisement of black voters. To this end, he forged alliances with the new (and notably liberal) Readjuster and Greenback Parties. These efforts failed except for the brief tenure of the Readjusters in Virginia, where white supremacy's tide ultimately drowned that party's bi-racial coalition. Arthur also pushed with some success to fund education for American Indians. He pressed as well for the "allotment system," whereby individual tribe members and not tribes could own land. This system was not adopted until the first Grover Cleveland administration and then proved harmful to those it was supposed to help, with much Native land resold cheap to speculators.

A charming sophisticate, Arthur dressed stylishly, enjoyed the social whirl and had the Executive Mansion refurbished. "Elegant Arthur" was one of his nicknames, according to author Anthony Bergen (whose Arthur post on his terrific Dead Presidents website informs some finer points of this one—and here is his link: href=http://deadpresidents.tumblr.com). His reintroduction of liquor to Presidential get-togethers brought a harrumph from former President Hayes, who had banned it. For Henry Adams, the historian and member of the Adams political family, Arthur's stylishness and social aptitude denoted something rotten; with a puritanical sniff, he dismissed the administration as "the centre for every element of corruption." But by the end of Arthur's time in office, this was a minority opinion. Mark Twain said, "It would be hard indeed to better President Arthur's administration," while journalist Alexander McClure declared, "No man ever entered the Presidency more profoundly and widely distrusted than Chester Alan Arthur, and no one ever retired . . . more generally respected, alike by political friend and foe." In his Oxford History Of The American People, historian Samuel Eliot Morison wrote, "Arthur's administration stands up as the best Republican one between Lincoln and Theodore Roosevelt."

Late in 1882, however, Arthur's life darkened when he was diagnosed with Bright's disease (now called nephritis), a chronic kidney ailment that ensured he would not live to old age. Questions about his health were successfully deflected. Still, the illness certainly figured into his decision not to seek the Republican nomination in 1884. After leaving office, he lived only another year and nine months and in increasing misery, dying on November 18, 1886. On his deathbed he asked Chester Jr. to destroy all of his private and public documents and his son complied, burning the papers in trash cans. As a result, studies of the Arthur administration can only go so wide and deep. Why did he have his papers burned? A good guess is that his former image as a corrupt machine politician still pained him—and that in this last act, he hoped to shield himself against the harshly interpretive eye of history. I don't think he need have worried.

Anyway—even though it has little to do with the Civil War and even less with my novel Lucifer's Drum, here is my submission to that NPR 3-Minute Fiction contest:

ARTHUR’S PHANTOMS: OCTOBER, 1882

The Surgeon General’s diagnosis had drawn a stark border in time, dividing the last few hours from all the years before. And it seemed to have cleaved the President himself in two. At the desk, his ample body sat through a series of appointments while his soul observed from a ghost realm. His corporeal callers—the Secretary of State, just now, intoning about the Mexican trade agreement—remained oblivious as he watched the ghosts circulate.

One of them was Garfield, fierce-browed yet natty with his trimmed beard and black broadcloth suit, his watch fob glinting. Had he looked like this just before the madman shot him on the railroad platform? And had he lived, would he and his erstwhile running mate have grown to like each other? The President had admired Garfield as honest and intelligent—but Garfield had seemed to only half-reciprocate. No one had ever thought Chester Alan Arthur unintelligent, though many thought him untrustworthy—a foul creature of the Conkling machine, an overfed New York dandy spattered with political sewage. Without Arthur to knit up the Stalwart faction, Garfield would not have been elected—and yet as Vice-President, Arthur had been made to feel leprous.

As Garfield exited, Little William in his white baby clothes came stumbling, passing so close that the President nearly reached for him. The Secretary of State paused in his exposition, one eyebrow arching. “Please go on,” Arthur prodded. William smiled through pink gums and was gone, leaving an oddly precise ache in the President’s fingertips.

With the inevitability of autumn rain, Nell came next. Nell with whorled raven hair, face molded like a chalice. Nell in ivory taffeta, as young as her portrait in the East Room, where daily flowers kept vigil. As her lustrous eyes turned his way, he recalled them dimming with resentment for his late nights, his long absences in the party’s service. A Virginia lass, highborn. During the war, some had suspected Nell’s loyalty to the North. Whatever the truth, they had never known her. And they did not know him.

“I am a Stalwart,” Garfield’s assassin had declared, “—and Arthur will be President!” Some had speculated about a wider plot. And when the man’s lunacy had become too evident, they resorted to questioning Arthur’s citizenship. Born in Ireland, they said—and when that story didn’t work, born in Canada. More had simply shaken their heads, incredulous that a mere vassal of the spoils system, onetime Collector of the Port of New York, was now President of the United States.

The grotesqueries of “public discourse”—calls to exterminate the Indians, to shut out the Chinese, to keep the Negroes whipped and impoverished—were a giant trope for all the private, individual crimes committed round-the-clock. The easy judgment, the cold dismissal, the proud pontification. Self-styled reformers could be as vain as the most corrupt potentate, as vicious as any masked nightrider. But Arthur would give them reform. Oh, they would choke on reform. The Civil Service Bill was just the beginning—and when he was finished, their hunger for judgment would have to go sniffing elsewhere.

When the Secretary departed, Nell glided out after him. The spectral visitations, Arthur realized, had ceased for now. Standing at the French doors, he watched the wind-blown shrubbery outside, the low pewter clouds moving fast. His hand moved to the burning spot below his ribcage. Bright’s Disease—it was both daunting and reassuring to have it named. Specialists would have to be quietly summoned, a story concocted for the people. Not yet could he join the realm of phantoms.

This past Presidents Day (Feb. 16) brought to mind an NPR-sponsored contest I entered in the fall of 2012, "3-Minute Fiction: Pick A President." Contestants were told to submit a 600-word entry—about 3 minutes' reading time—focusing on any U.S. President, even a fictitious one. Over the weeks they read some of the entries on-air or posted them on the NPR site and I enjoyed all of them. The winner in the end was very good and quite original, featuring a man whose dementia-plagued father believed that Spiro Agnew had succeeded Nixon as President.

My submission was probably doomed to obscurity when I decided that it should be about our 21st President, Chester Alan Arthur. Why did I do this? Why did I pick my man from the gray middle of the pack—a virtual guarantee that it would be like throwing a jellybean into the Grand Canyon and waiting for an echo? The answer is straight from History Nerd Central: I am a champion of Chester A. I think he was a decent guy who made the best of a daunting situation. And I think he belongs farther up the rankings than historians often place him.

Chester A. Arthur, 21st President

of the United States.

(Courtesy: Library of Congress)

In the giant shadow of Abraham Lincoln, in a landscape gibbering with the ghosts of over 700,000 dead—and with the failure of Reconstruction, the maw of Jim Crow opening wide—post-Civil War politics seemed overpopulated with men who were bitter, vengeful, venal, corrupt and small. As far as Presidents go, many of us tend to think of the 36 years between Lincoln and the bright comet of Teddy Roosevelt as a kind of trough. Given this, it is surprising to actually look at who got into the Executive Mansion. Apart from Andrew Johnson and Benjamin Harrison—consistently rated as bottom-feeders—the United States was lucky to have these men available for the office. A few like Arthur were natural administrators; others like Ulysses S. Grant were not, but at least showed themselves to be fundamentally good and honest. It could definitely have been worse, as Johnson and Harrison abundantly proved.

Arthur was born in Fairfield, Vermont in 1829. His Irish-born father was a teacher-turned-minister and bedrock Abolitionist. Arthur (whose family always called him "Alan") started out as a teacher but ultimately switched to the law and New York City. Upon his admission to the bar, he joined the firm of the Abolitionist lawyer and family friend Erastus T. Culver, who then made him a partner. He lost no time distinguishing himself, helping to win the Lemmon v. New York decision, which established that any slave transported to New York State was automatically free.

Soon afterward, in 1854, Arthur served as lead attorney for Elizabeth Jennings Graham, a black schoolteacher and church organist. Late for service one Sunday, Graham had boarded a New York City streetcar which turned out to be whites-only. The conductor ordered her off but she insisted on her right to ride. Only after putting up an impressive physical fight with the conductor and a policeman before a hostile crowd was she forced off the car. It should perhaps have been clear right then that they had messed with the wrong church lady—but it definitely became so when Arthur took up her case. (Something else that might have made them think twice: Graham was the daughter of wealthy clothing store owner Thomas L. Jennings, founder of the Abyssinian Baptist Church and also the Legal Rights Association, which targeted racist statutes.) The next year—a full century before Rosa Parks—Arthur won Graham's suit against the conductor, the driver and the Third Avenue Railroad Company, which then had to desegregate its streetcars. Thanks in large part to the decision, all of NYC's public transit services were desegregated by the end of the Civil War. Elizabeth Graham went on to found the city's first kindergarten for black children.

Elizabeth Jennings Graham (1827-1901), civil

rights heroine and successful Arthur client.

(Courtesy: Kansas Historical Foundation)

By the time of the Civil War, Arthur had his own law practice, was deeply involved in Republican politics and married to the Virginia belle Ellen "Nell" Herndon, daughter of naval officer and explorer William Lewis Herndon (who was lost in the sinking of the SS Central America in 1857.) In 1861 the governor of New York assigned Arthur to the state's quartermaster department with the rank of brigadier general. He was so effective at housing and equipping the new troops that deluged NYC that he was soon promoted to inspector general and then quartermaster. He would have gone to the front as a regimental colonel if not for the governor's personal plea for him to maintain his home-front role. Yet that role was a political appointment and when the Democrats took over state government in 1863, Arthur lost his post.

Soon after this, he and Nell suffered the death of their three-year-old son William from illness. Nell gave birth to another son, Chester Alan Jr., the following year. In their ongoing grief over William, they heaped indulgence on young Chester, who grew up to be a rich, idle, attention-loving playboy. In 1871 they had a daughter, Ellen, who would lead a much lower-profile life. That same year saw Arthur named Collector of the Port of New York—a federal appointment and a highly lucrative one, typifying the spoils system and its routine rewards for political loyalty. It was a corrupt system, though then fully legal and Arthur personally quite honest. By the mid-1870's, however, the fever for civil service reform threatened to split the Republicans between the reform-minded "Half-Breeds" and the more traditional and complacent "Stalwarts," with the political machine of Senator Roscoe Conkling (Arthur's friend and patron) embodying the latter. The conflict resulted in President Rutherford B. Hayes sacking Arthur in 1878, an experience that left Arthur feeling branded as corrupt.

Arthur's ever-increasing work for the Conkling machine led to late nights and long absences, which strained his marriage. He was away in Albany in January 1880 when Nell died of pneumonia at age 42, causing him a sense of guilt that never quite abated. Within a year of this, he was catapulted to the Vice Presidency of the United States. The tumultuous 1880 Republican convention ended up nominating the "dark horse" (compromise, unforeseen) candidate James A. Garfield of Ohio for President. A champion of the Half-Breed faction, Garfield sought to mend the party split by choosing the Stalwart Arthur as his running mate. Arthur readily accepted the offer despite Conkling's urging that he not. His role in the election proved crucial, as the Republicans won by a wafer-thin 9,070 in the popular vote.

Ellen "Nell" Herndon Arthur (1837-1880), wife of Chester

A. Arthur. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

Arthur and Garfield immediately became estranged, however, over the latter's resistance to appointing Stalwarts to important posts. Arthur was in Albany on July 2, 1881, when he heard that Garfield had been shot and grievously wounded on a Washington railroad platform. Most unfortunately for Arthur, the assassin Charles J. Guiteau had declared on the spot, "I am a Stalwart, and Arthur will be President!" Never mind that Guiteau (often described as "a disappointed office-seeker") would make Booth and Oswald look like poster boys for mental health—the statement stoked public mistrust of Arthur, due to his background in urban machine politics.

Over the terrible eleven weeks that it took President Garfield to die, Constitutional constraints and Arthur's reluctance to seem presumptuous re: presidential authority (he stayed the whole time in NYC) created a power vacuum, ending only with Garfield's death on Sept. 19. And here I must say—the full tragedy of James Garfield's murder is lost on us today. He was smart, honest, gutsy, highly competent and a talented orator. Though President for only six and half months, the final two and a half spent bedridden and in pain, he had shown himself to be a quality leader, one who belonged in high office. As a for-instance, his feeling for the plight of African Americans was genuine, his intentions for them heartfelt without being especially naive; he in fact appointed a number of them to prominent posts, at a time when it was increasingly risky to do so. The tragedy would have been compounded had an Andrew Johnson been waiting in the wings to assume power. Luckily for all of us, though, it was Chester A. Arthur.

Widespread skepticism greeted Arthur's swearing-in. He came to the office with one of the slightest resumes in Presidential history. Malicious rumors were circulated that he had been born outside of the U.S. (sound familiar?) and was therefore ineligible for the Presidency. One by one, cabinet members—looking askance at this accidental President, and mindful of their careers—resigned and had to be replaced. Only the Secretary of War, Robert Lincoln (son of Abraham), stayed on for all of Arthur's term. A great many people expected Arthur to act like a creature of the spoils system, a typically corrupt big-city politician—but that is not how he acted. He embraced the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act, which stipulated that government jobs be offered on the basis of competence and not political patronage, that competence be rated by competitive exams, and that a United States Civil Service Commission be created to oversee the process. Arthur signed it into law in January, 1883, and it proved the central attainment of his Presidency. It raised the ire of his old friend Conkling, who had of course wanted machine politics to continue as ever (Conkling called it the "Snivel Service Act"). And old New York cronies came away disappointed when they approached Arthur for favors.

James A. Garfield, 20th President of the

United States and its second to die by

an assassin. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

Arthur also did much to revive the moribund U.S. Navy by pushing to fund the construction of steel-plated vessels. On other fronts, results for his administration were more mixed and frustrating. Arthur had the courage to veto the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which included a 20-year ban on immigration from China and denied citizenship to Chinese immigrants. But when the ban was cut to ten years, he grudgingly signed the bill, knowing that another veto would be overridden and weaken his Presidency. In the area of Civil Rights, he sought to combat the reemergence of the Southern Democrats and their disenfranchisement of black voters. To this end, he forged alliances with the new (and notably liberal) Readjuster and Greenback Parties. These efforts failed except for the brief tenure of the Readjusters in Virginia, where white supremacy's tide ultimately drowned that party's bi-racial coalition. Arthur also pushed with some success to fund education for American Indians. He pressed as well for the "allotment system," whereby individual tribe members and not tribes could own land. This system was not adopted until the first Grover Cleveland administration and then proved harmful to those it was supposed to help, with much Native land resold cheap to speculators.

A charming sophisticate, Arthur dressed stylishly, enjoyed the social whirl and had the Executive Mansion refurbished. "Elegant Arthur" was one of his nicknames, according to author Anthony Bergen (whose Arthur post on his terrific Dead Presidents website informs some finer points of this one—and here is his link: href=http://deadpresidents.tumblr.com). His reintroduction of liquor to Presidential get-togethers brought a harrumph from former President Hayes, who had banned it. For Henry Adams, the historian and member of the Adams political family, Arthur's stylishness and social aptitude denoted something rotten; with a puritanical sniff, he dismissed the administration as "the centre for every element of corruption." But by the end of Arthur's time in office, this was a minority opinion. Mark Twain said, "It would be hard indeed to better President Arthur's administration," while journalist Alexander McClure declared, "No man ever entered the Presidency more profoundly and widely distrusted than Chester Alan Arthur, and no one ever retired . . . more generally respected, alike by political friend and foe." In his Oxford History Of The American People, historian Samuel Eliot Morison wrote, "Arthur's administration stands up as the best Republican one between Lincoln and Theodore Roosevelt."

Late in 1882, however, Arthur's life darkened when he was diagnosed with Bright's disease (now called nephritis), a chronic kidney ailment that ensured he would not live to old age. Questions about his health were successfully deflected. Still, the illness certainly figured into his decision not to seek the Republican nomination in 1884. After leaving office, he lived only another year and nine months and in increasing misery, dying on November 18, 1886. On his deathbed he asked Chester Jr. to destroy all of his private and public documents and his son complied, burning the papers in trash cans. As a result, studies of the Arthur administration can only go so wide and deep. Why did he have his papers burned? A good guess is that his former image as a corrupt machine politician still pained him—and that in this last act, he hoped to shield himself against the harshly interpretive eye of history. I don't think he need have worried.

Anyway—even though it has little to do with the Civil War and even less with my novel Lucifer's Drum, here is my submission to that NPR 3-Minute Fiction contest:

ARTHUR’S PHANTOMS: OCTOBER, 1882

The Surgeon General’s diagnosis had drawn a stark border in time, dividing the last few hours from all the years before. And it seemed to have cleaved the President himself in two. At the desk, his ample body sat through a series of appointments while his soul observed from a ghost realm. His corporeal callers—the Secretary of State, just now, intoning about the Mexican trade agreement—remained oblivious as he watched the ghosts circulate.

One of them was Garfield, fierce-browed yet natty with his trimmed beard and black broadcloth suit, his watch fob glinting. Had he looked like this just before the madman shot him on the railroad platform? And had he lived, would he and his erstwhile running mate have grown to like each other? The President had admired Garfield as honest and intelligent—but Garfield had seemed to only half-reciprocate. No one had ever thought Chester Alan Arthur unintelligent, though many thought him untrustworthy—a foul creature of the Conkling machine, an overfed New York dandy spattered with political sewage. Without Arthur to knit up the Stalwart faction, Garfield would not have been elected—and yet as Vice-President, Arthur had been made to feel leprous.

As Garfield exited, Little William in his white baby clothes came stumbling, passing so close that the President nearly reached for him. The Secretary of State paused in his exposition, one eyebrow arching. “Please go on,” Arthur prodded. William smiled through pink gums and was gone, leaving an oddly precise ache in the President’s fingertips.

With the inevitability of autumn rain, Nell came next. Nell with whorled raven hair, face molded like a chalice. Nell in ivory taffeta, as young as her portrait in the East Room, where daily flowers kept vigil. As her lustrous eyes turned his way, he recalled them dimming with resentment for his late nights, his long absences in the party’s service. A Virginia lass, highborn. During the war, some had suspected Nell’s loyalty to the North. Whatever the truth, they had never known her. And they did not know him.

“I am a Stalwart,” Garfield’s assassin had declared, “—and Arthur will be President!” Some had speculated about a wider plot. And when the man’s lunacy had become too evident, they resorted to questioning Arthur’s citizenship. Born in Ireland, they said—and when that story didn’t work, born in Canada. More had simply shaken their heads, incredulous that a mere vassal of the spoils system, onetime Collector of the Port of New York, was now President of the United States.

The grotesqueries of “public discourse”—calls to exterminate the Indians, to shut out the Chinese, to keep the Negroes whipped and impoverished—were a giant trope for all the private, individual crimes committed round-the-clock. The easy judgment, the cold dismissal, the proud pontification. Self-styled reformers could be as vain as the most corrupt potentate, as vicious as any masked nightrider. But Arthur would give them reform. Oh, they would choke on reform. The Civil Service Bill was just the beginning—and when he was finished, their hunger for judgment would have to go sniffing elsewhere.

When the Secretary departed, Nell glided out after him. The spectral visitations, Arthur realized, had ceased for now. Standing at the French doors, he watched the wind-blown shrubbery outside, the low pewter clouds moving fast. His hand moved to the burning spot below his ribcage. Bright’s Disease—it was both daunting and reassuring to have it named. Specialists would have to be quietly summoned, a story concocted for the people. Not yet could he join the realm of phantoms.

Published on March 03, 2015 18:58

•

Tags:

chester-a-arthur, lucifer-s-drum, npr-pick-a-president