Bernie MacKinnon's Blog - Posts Tagged "edwin-m-stanton"

Spy Chiefs For The Union

STEEL NERVES, IRON FIST

In his dank gas-lit chamber he had come to haunt the public imagination, fashioning himself as a burrowed beast of prey. Infamy and prestige were one and the same for Lafayette Baker—and from his basement lair, that prestigious infamy resonated like a tiger’s snarl.—from Lucifer's Drum

In Lucifer's Drum, my main character Major Nathaniel Truly works for the secret service of the U.S. War Department. His boss and occasional bane-of-existence is Colonel (later Brigadier-General) Lafayette C. Baker, one of those figures who could only have sprung from real life—especially from the Civil War, whose turmoil swept many natural-born scoundrels into positions of power. The grandson of a Revolutionary War hero, Baker was born in western New York in 1826. As a young itinerant mechanic, he landed in California around the time of the Gold Rush and joined San Francisco's ruthless Vigilance Committee, pledged to impose order and quash crime. Baker—gray-eyed, reddish-haired and a sharp dresser—stood out among the vigilantes, who recalled him as a crack pistol shot and paragon of physical stamina. These assets plus a disdain for legal niceties (and for liquor—rare in that time and place) would serve him well later on.

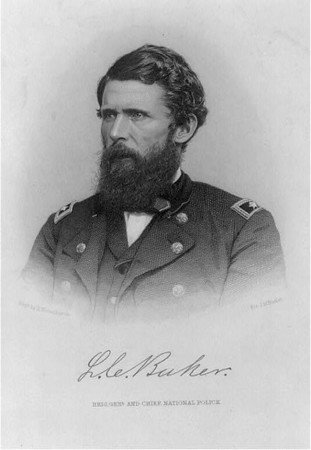

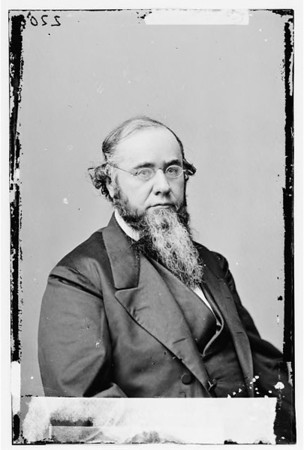

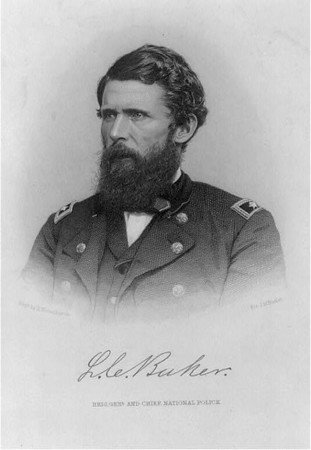

Lafayette C. Baker (1826-1868), chief detective

of the U.S. War Department and my main character's

problematic superior. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

Baker returned East in time for the Civil War's onset—an hour that gaped with nation-wide menace but also with opportunity, for men of certain skills. In July 1861, as the First Battle of Manassas loomed, he wangled an audience with General-in-Chief Winfield Scott. Baker proposed that he prove his worth with a daring, free-of-charge solo mission into northern Virginia, where he would learn the disposition of Confederate forces. Struck by his self-confidence, the elderly general agreed, giving him ten twenty-dollar pieces to finance the mission—which, even if you discount a detail or two of Baker's narrative, unfolded as an espionage drama and comedy in equal parts, requiring more nerve, luck and tenacity than a dozen ordinary spies could have shown.

His first effort to cross the Potomac was thwarted when federal troops arrested him and sent him to General Scott, who chuckled and told him to try again. He did so and was once more arrested by Union soldiers, though this time he talked his way out of it. The third try proved a charm, when he paid a farmer to row him to the Virginia side. Now on Rebel soil, he tramped westward through the summer heat but was nabbed by a pair of Confederate pickets. Before they could march him to their commander, he persuaded them to stop at a tavern where he got them drunk and gave them the slip. He kept on toward the main Southern encampment at Manassas but was caught yet again by a cavalry patrol.

Following a stern interview with General P.G.T. Beauregaud, he found himself in a stockade but then bribed an officer into letting him out for a spell, under guard. He got his guard drunk at a hotel bar and then took a leisurely stroll with him around the Confederate encampment, noting various units and learning the strength of each—including the Black Horse Cavalry, a special interest of General Scott's. When his tipsy, talkative guard wandered off, Baker wisely attempted no escape and returned on his own to the stockade. Confined again, he deflected his jailers' tricks to reveal him as a spy, as when a teenaged girl appeared with a whispered offer to smuggle out a note for him. (The girl was purportedly Belle Boyd, soon to be famous as "La Belle Rebelle" and the "Cleopatra of the Secession." Whether or not it really was her, the two would eventually cross paths—in reverse circumstances.)

Baker declared himself an innocent Knoxville, Tennessee native who had returned South to settle legal claims for a California minister—he had a partially forged letter to this effect. Still under suspicion, however, he was sent to Richmond by train and imprisoned there, wondering whether he would be hanged or just left to moulder. But after a few days, he found himself at the Spottswood Hotel, being interrogated by the President of the Confederate States himself, Jefferson Davis. Baker's nimble performance under pressure won him a parole within Richmond city limits, though he assumed that he was being watched. In an unlikely chance encounter, an old acquaintance called out his name in the street—then needed a ton of convincing that he had made a mistake. Alarmed, Baker decided it was time to cut bait. He managed to obtain a temporary pass to Fredericksburg.

His escape from Dixie was no less harrowing than his infiltration of it. Detained by Rebel cavalrymen north of the Rappahannock, he faked a limp to put them off guard, then stole a horse and a revolver as they slept. The next day, he evaded a Confederate search party by hiding in a haystack—into which an officer thrust his sword, coming inches from running the spy through. At last—starved, exhausted and with Rebel troops firing after him—he crossed the Potomac to safety in a stolen skiff.

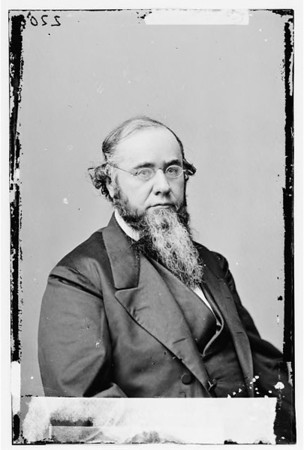

This exploit earned Baker a job as confidential agent, first to the Secretary of State and later to the Secretary of War. His suspicious nature helped make him effective as he shifted from intelligence to counterintelligence, ferreting out Confederate spies, smugglers and sympathizers. Military authorities and the District of Columbia police took a dim view of his brusqueness as well as his contempt for due process. Still, Edwin Stanton's War Department raised him to "Special Provost Marshal" and commissioned him a colonel, lending greater scope to his zeal. He was therefore perfectly positioned when, in November 1862, President Lincoln sacked General George McClellan as commander of the Army of the Potomac, and McClellan's loyal hireling Allan J. Pinkerton left the scene as well, ending his role as the Union's chief spymaster.

THE RELENTLESS SCOTSMAN

. . . the war’s onset had found him restless and uncertain, vulnerable when Pinkerton’s telegraphed plea arrived from Washington: MOMENTOUS TIMES–GOOD MEN NEEDED–AMPLE PAY–PLEASE COME EAST. What if he had declined? Would the war tides have left him relatively untouched, sitting on his stoop outside Chicago? With Rachel still at his side?

"Fate," Truly murmured, "thy name is Allan Pinkerton.”—from Lucifer's Drum

Born in Scotland in 1819, Allan Pinkerton immigrated to Illinois at age 23, working as a cooper until he helped foil a group of counterfeiters who were operating near his settlement. That episode led to his becoming Chicago's first police detective and in 1850, with an attorney partner, founding the private detective agency that came to bear his name. With cutting-edge business acumen, the firm advertised itself with the logo of a single unblinking eye (from which the term "private eye" would hatch) and the slogan, "We Never Sleep." Pinkerton was a constant reader and autodidact, as well as a lifelong atheist. He hired the first-ever female detective, the intrepid Kate Warne, and other women after her. He also hired the Union's first African American agent, John Scobell. And in the 1870's, he began compiling the world's first criminal database—a "rogue's gallery," with clippings, rap sheets and mug shots.

Union detective Allan J. Pinkerton (1819-

1884)—effective on the home front,

out of his depth at the battlefront.

(Courtesy: Library of Congress)

Pinkerton's eventual close linkage with McClellan held one apparent contradiction: the former was a committed Abolitionist—his homestead was a stop on the Underground Railroad and he and his wife gave material support to John Brown—while the latter never hid his disdain for Abolitionism. Nevertheless, the relationship commenced after McClellan became chief engineer and vice-president of the Illinois Central Railroad, for which Pinkerton's agency solved a series of train robbery cases. The detective also became acquainted with the Railroad's top lawyer, Abraham Lincoln.

Thus, with the eruption of the Civil War, did Pinkerton land at history's red-hot center. In February 1861, charged with ensuring President-Elect Lincoln's safe arrival in Washington, Pinkerton obtained intelligence concerning an assassination plot in Baltimore, where Lincoln's train would have to stop. He personally shepherded Lincoln onto a secret train that made Baltimore by night, then onto another train that left before secessionist mobs could get wind of it. That summer, when his patron McClellan took command of the Army of the Potomac, Pinkerton became head of the Union Intelligence Service. He threw himself into plugging intelligence leaks—both the government and the army high command were spouting like sieves—and arresting Confederate spies in and around the capital. He and his agents did a highly creditable job, breaking up the Rose Greenhow Ring and sending that celebrated femme fatale to the Old Capitol Prison.

The Old Capitol Prison, First & A Street, Washington, D.C., present-day site of the

Supreme Court. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

But battlefield intelligence-gathering was another matter entirely—and when McClellan's lumbering Peninsular Campaign got under way in April 1862, Pinkerton's inexperience in that area bore bitter fruit. His methodology reflected McClellan's already delusional fears about the forces opposing him, greatly magnifying their numbers and reinforcing the general's innate caution—and turning the campaign into a bloody failure. (See "Until A Dictator: Lincoln vs. The RISODS," https://www.goodreads.com/author_blog.... In Lucifer's Drum, Truly recalls his frustration over this sorry performance and the final break it causes between him and Pinkerton.) For months, even through the sanguinary saga of Antietam, Lincoln found reason to tolerate McClellan's unchanging conduct, until he no longer could. And when the President at last fired Little Mac, handing Ambrose Burnside command of the Army of the Potomac, Pinkerton decided to pack it up. He spent the rest of the war investigating fraud among army supply vendors and other such cases.

BATTLEFRONT BRILLIANCE, HOME FRONT THUGGERY

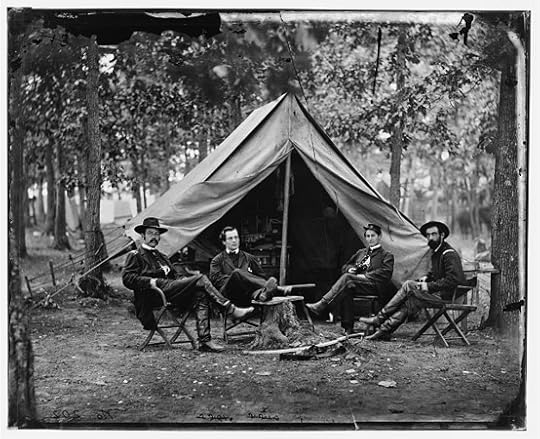

In his brief, disastrous tenure as commanding general, Burnside appears to have done nothing innovative in the area of intelligence. But when Joseph Hooker succeeded him in late January 1863, that general charged Colonel George H. Sharpe of the 120th New York Regiment with building a new organization within the army itself. So was born the Bureau of Military Information. Multi-lingual and classically educated—and in Lucifer's Drum, the immediate superior of Truly's associate Captain Bartholomew Forbes—Sharpe was an attorney and also a low-level diplomat who had served in Rome and Vienna. Under his capable authority and with invaluable help from two subordinates—Captain John McEntee and the civilian scout "Captain" John Babcock—the Bureau gathered an effective stable of scouts and agents and began cross-checking intelligence from numerous sources. Its greatest triumph was in the immediate days before Gettysburg, when its web of informants and diligent sifting of reports yielded the size, composition and direction of Robert E. Lee's army.

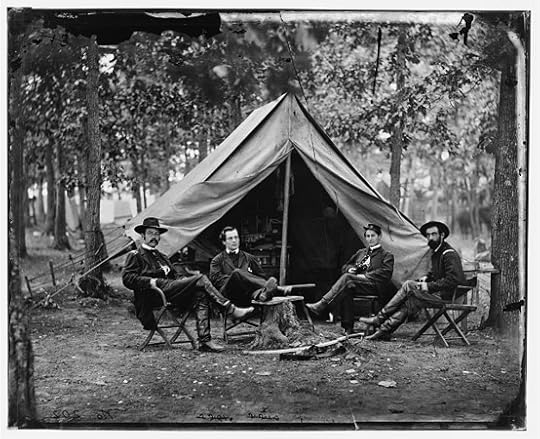

The capable Colonel George H. Sharpe (left, 1828-1900) of the Bureau of Military

Information, with subordinates at Brandy Station, Virginia, early 1864. (Courtesy:

U.S. Army)

Sticking with military intelligence, Colonel Sharpe's superb outfit filled half of the post-Pinkerton vacuum. To fill the other half—civilian espionage on the home front—Lafayette Baker was named head of the War Department's new detective section, which he grandly dubbed the National Detective Police (a name that my character Nate Truly derides.) It never boasted more than forty regular employees, though its tentacles reached some 2,000 informants throughout the North. Granted wide latitude, Baker consequently ran a rather nebulous operation. Counterintelligence and Confederate spies were of course a major focus, along with smuggling—and it took only a vague suspicion for Baker to arrest someone and consign him or her to the grimy, crowded confines of the Old Capitol Prison.

Appalled observers pronounced it a Reign of Terror, comparing Baker to Napoleon's cold-blooded police director Joseph Fouche. Supposedly modeling his methods on those of another Frenchman—the legendary criminal-turned-detective Eugene-Francois Vidocq—Baker wore a silver badge engraved with the words "Death To Traitors" (a detail that, damn it, I wish I'd stumbled upon while researching my novel—it would have been a nice touch). Still, his activities were all over the map. Much energy went to tracking down fraudsters, deserters, bounty-jumpers and, increasingly, counterfeiters. Baker even raided saloons, bordellos and gambling "hells" around the District and tried to suppress the nascent pornography industry. It all sounds grimly dutiful—but persistent scuttlebutt had him extorting cuts from illegal money schemes that he uncovered, as well as pocketing funds from arrestees.

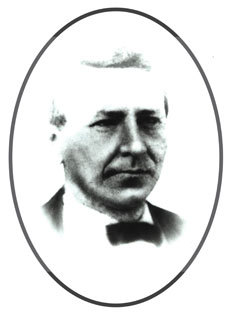

Working hand-in-glove with Baker was the wily superintendent of the Old Capitol, William P. Wood, a figure worth a book of his own. A model-maker by trade, the Alexandria, Virginia native had testified as an expert defense witness in the 1854 McCormick Reaping Machine trial, in which future Secretary of War Edwin Stanton beat back charges of patent infringement against his client. The Civil War revealed an enduring tie between Wood and Stanton, who became the former's patron and protector—often to a startling degree. (Of Wood's mysterious hold over the volatile Secretary, it was said, "Stanton is head of the War Department, and Wood is the head of Stanton.") Before his appointment as the Union's preeminent jailer, Wood was Commissioner of Public Buildings as well as a War Department operative. As bodyguard to Mary Todd Lincoln, he accompanied her on at least one of her notorious shopping binges (to Philadelphia, during which she bought the famous "Lincoln Bed.")

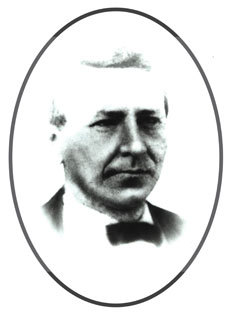

William P. Wood (1820-1903),

wily and sardonic, superintendent

of the Old Capitol Prison, later

head of the first formally named

United States Secret Service.

Physically small but powerful, Wood had served as a cavalryman in the Mexican-American War, though his rumored heroic exploits in that conflict remain just rumors. More certain is that while posted to New Mexico Territory, his commanding officer—future Union Brigadier-General and D.C. Provost Marshal Andrew Porter—sometimes ordered him strung up by the thumbs for one infraction or another. Later, presiding at the Old Capitol—and like Baker, holding a colonel's commission—he took obvious delight in bucking military orders (Porter's especially) and outraging the brass, whose efforts to retaliate were nevertheless quashed by Stanton.

Wood liked to receive incoming prisoners personally, his manner mixing graciousness with amused sarcasm. To an Englishman caught trying to pass through federal lines, he said, "I'm always glad to see your countrymen here!" Mockery was of course the least of an inmate's worries. In the dingy cells of the Old Capitol (present-day site of the Supreme Court), Wood and Baker employed time-honored and decidedly lowdown interrogation tactics. After days or weeks of isolation, a prisoner would be urged to sign a confession and, if he refused, be confronted with fake testimony. This would prompt him to speak in protest and perhaps elaborate on his case, after which the transcript would be read back to him with bogus passages inserted, leaving him confused, despairing and ripe for confession.

Confederate spy Belle Boyd, "the Cleopatra of the Secession."

(Courtesy: Getty Images)

Belle Boyd, age 18 at the time, described her own encounter with the Lafe & Willy Show during her stay in the summer of 1862, with Baker playing the menacing bad cop and Wood the unctuous good one. Boyd got off with relative ease, though, considering her refusal to confess or to take the oath of allegiance. When Baker's verbal bullying provoked a haughty retort from the girl spy, Wood took his colleague by the arm and said, "We'd better go—the lady is tired."

In her incomparable Pulitzer-winning book Reveille In Washington: 1860-1865, Margaret Leech said of Wood, "He was crafty and hypocritical, but his kindness was genuine." This quality showed in a grand gesture he made upon Belle Boyd's release, as part of a prisoner exchange. Having become engaged to a young Confederate officer and fellow inmate, Boyd had earlier been denied a day pass to shop for her wedding trousseau, so that joyous ritual remained unfulfilled. Sadness no doubt clouded her trip southward to Richmond, since freedom meant separation from her fiancee. But one happy surprise awaited her behind Confederate lines, when she received the trousseau that Wood himself had bought and sent after her under a flag of truce. Wood was especially solicitous with females, though he did have his limits. After a demanding note from the imperious Rose Greenhow, the superintendent wrote back, requesting that she "be kind enough to dispense with the God and Liberty style in your next pronunciamento."

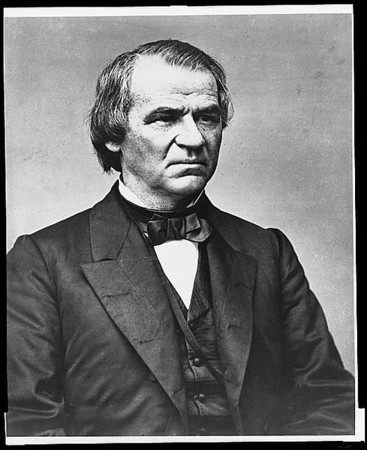

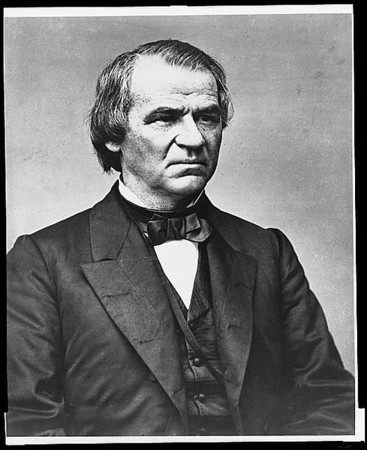

Edwin M. Stanton (1814-1869), Lincoln's

volatile yet gifted Secretary of War.

(Courtesy: Library of Congress)

Part of historical fiction's challenge is doing justice to any real historical figures an author might use, figures he would have had a hard time inventing. And in Lucifer's Drum, I tried to do justice to William Wood, depicting him as someone who Nate Truly values but can't entirely trust:

At the Old Capitol, government supplies had a habit of disappearing. Wood’s nephew ran the prison commissary, and it was whispered that the two of them were robbing it blind. Though an unswerving Republican and Abolitionist, Wood seemed on good terms with the smugglers and blockade runners who he kept under lock. Even with some of the Rebel troops he appeared friendly, provided they weren’t rabid in politics or aristocratic in bearing. With the occasional lady prisoner he was indulgent unto silliness, and most new arrivals were in fact received kindly. To a prisoner brought in on dubious charges, his rights blown away like dandelion seeds, Wood pledged every effort for his comfort and eventual release, then arranged for a detective to pose as the fellow’s cellmate. A lapsed Catholic, he reveled openly in non-belief while encouraging Sunday services at the prison. Dubbing him “The Crown Prince of Duplicity” or—invoking the two-faced Roman god—“Janus the Jailer,” Truly was nonetheless grateful for Wood’s presence on Earth, with its reminder of life’s twisted sorcery.

HARD FATES AND TANGLED WEBS

Most likely with job security in mind, Baker tried to dig up dirt on his boss Stanton by tapping one of his telegraph lines. But he was found out. Despite Stanton's fury, he did not sack Baker but exiled him to New York City, placing him under the thumb of an Assistant Secretary. Immediately upon President Lincoln's assassination, however, Stanton summoned his wayward operative back to Washington. Baker's aggressive reputation recommended him to the task of tracking down John Wilkes Booth and his fellow conspirators—which in a matter of days, he accomplished. Hound-like, he and his men scoured the District and countryside and made key arrests. On April 26, 1865, thanks in large part to Baker's efforts, Booth and his associate David Herold were trapped in a barn near Port Royal, Virginia and the actor/assassin was fatally shot. Baker collected $3,750 in reward money and President Andrew Johnson commissioned him a brigadier-general. From that point, however, Baker's fortunes took a steep dive.

President Andrew Johnson (1808-1875), combative

impeachment survivor, consistently rated among

the worst Presidents. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

Amid the rancor between Johnson and Congress, Baker's promotion was never confirmed. And in February 1866, having discovered that Baker was spying on him, Johnson ordered him sacked. Newspaper condemnation of the uber-snoop's wartime excesses had meanwhile been mounting. (Baker's story makes me reflect on historical figures like him and the nations that hire them—in particular, nations that openly aspire to humane and democratic values. Faced with an existential threat, they will call upon brutal men to act out their natures and do whatever the country's survival seemingly demands. With eyes averted, they will advance and encourage these men—but once the threat subsides, will distance themselves from the tools of their dirty work. It's as if democracy, at least in extremis, requires a certain amount of hypocrisy.)

A year later, Baker published his colorfully unreliable memoir, History Of The United States Secret Service, in which he stated that Stanton had ordered him to spy on Johnson—a plausible enough claim, given the two men's mutual enmity. No doubt resentful over Stanton's throwing him to the wolves, Baker also charged that his erstwhile chief had suppressed John Wilkes Booth's diary. When a Congressional investigating committee forced Stanton to turn over the diary, Baker testified that eighteen pages had been cut out. Stanton denied maiming the volume, though speculation persists to this day about its allegedly missing content. When the power struggle between Johnson and Stanton culminated in the former's impeachment trial, Baker testified against the President. Johnson famously survived the attempt to remove him from office, prompting Stanton to at last resign as War Secretary.

The Pinkerton National Detective Agency's iconic logo,

origin of the term "private eye."

As for Allan Pinkerton—the years enhanced his reputation as a crime fighter, despite setbacks and personal compromise. His agency's largely successful pursuit of the train-robbing Reno Gang was eclipsed by its failure to track down Jesse James. In 1872, despite his Abolitionist convictions, the Spanish government hired him to help defeat a Cuban revolutionary movement that opposed slavery. The Pinkertons played an increasingly anti-labor union role, breaking up the violent Molly Mcguires in Pennsylvania's coal region. Upon Pinkerton's 1884 death in Chicago—variously ascribed to a stroke, to malaria, or to gangrene after he slipped on the pavement and bit his tongue—his sons Robert and William took over the agency. Under them and later under his grandson Allan II, it gained long-term notoriety in the Homestead Strike (1892), the Pullman Strike (1894), the Ludlow Massacre (1914) and the Battle of Blair Mountain (1921)—a tragic irony, given its founder's youthful pro-labor sentiments. The agency exists today as a guard/detective subsidiary of Securitas AB, a Stockholm-based security group.

As head of the Bureau of Military Information, George Sharpe contributed mightily to the Union cause. But Army of the Potomac Commander George Meade nearly ruined the Bureau, absorbing it into his command structure and interfering with its methodology. In part because of this, Confederate General Jubal Early's July 1864 raid on Washington, D.C. went undetected until it was almost too late. The near-calamity prompted Ulysses S. Grant, the supreme commander, to reorganize the Bureau and restore its full effectiveness. Sharpe was promoted to brigadier-general in February, 1865. At Appomattox, he had the job of issuing paroles to every Confederate soldier, including Lee himself.

Federal civilian scout "Captain" John Babcock and his horse Gimlet, 1862. Babcock

served under Pinkerton and later under Sharpe. He went on to become a prominent

Chicago architect. (Courtesy: Getty Images)

In 1867, having resumed his happy life in Kingston, New York, Sharpe was dispatched by Secretary of State William Seward to Europe, where he vainly pursued the alleged Lincoln assassination conspirator John Surratt. Grant, having become President, appointed him federal marshal for the Southern District of New York in 1869. Against great resistance, he conducted an accurate census and thereby revealed election fraud, helping to break the power of the Tweed Ring. He then served as New York’s surveyor of customs until 1878, after which he remained active in the law and in state politics. He died in 1900.

In the aftermath of Lincoln's murder, the relationship between William Wood and his benefactor Stanton came apart. Wood took up the cause of accused conspirator Mary Surratt (John's mother), whose innocence he proclaimed, and sought an audience with President Johnson. In this Stanton allegedly thwarted him, breaking a promise that Mrs. Surratt would be spared the gallows. She hanged along with three male conspirators. Wood cut his ties with the War Department but, in July 1865, was named head of the first formally named United States Secret Service, a division of the Treasury Department, with the central task of fighting counterfeiting. He hired former forgers and counterfeiters to help in the endeavor, making more than two hundred arrests before angrily resigning in 1869, over a reward money dispute.

Late that same year, Stanton died, just days after President Grant nominated him for the Supreme Court. In an 1883 series of articles, Wood stated that Stanton had committed suicide, haunted to the last by the ghost of Mary Surratt. This claim was widely believed, though never proven. (Amid the aftershocks of the assassination, instances of personal disaster and despair make that period seem truly cursed. Senators James Lane of Kansas and Preston King of New York, for two examples, committed suicide within months of each other. The pair had blocked the White House stairs when Surratt’s daughter Anna came to beg a presidential pardon.)

Hanging of Lincoln conspirators, July 7, 1865. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

Wood made another startling claim, this one dating from the outset of his and Stanton’s acquaintance. He said that as Stanton's expert witness in the McCormick Reaping Machine trial, he had perjured himself, altering an early model of the reaper in order to win the case. He did not say whether Stanton knew of the deception—but to many, the story explained how Wood had come to secure the powerful man’s sponsorship. (Another member of the defense team was Abraham Lincoln, toward whom Stanton was rudely dismissive; Lincoln nevertheless appointed him as War Secretary eight years later—a tribute to the President’s pragmatic ego, as well as his eye for talent.) Wood died in 1903 at the age of 83, a more durable rogue than his friend Lafayette Baker.

Because Lafe Baker was long dead. In his sensational memoir as well as his testimony before Congress, he had come off as less than credible. But in 1868, settled in Philadelphia and expressing growing fears for his safety, he was said to be working on another book—one that would expose Stanton as the orchestrator of Lincoln's assassination. This roundly refutable conspiracy theory has proven more stubborn than most. Regardless, he died suddenly on July 3, age 41. Meningitis was deemed the cause, though Baker's wife had her suspicions. In the 1960's, Professor Ray A. Neff of Indiana State University used an atomic absorption spectrophotometer to analyze strands of Baker’s hair. It revealed arsenic poisoning as the cause of death. Citing Mrs. Baker's diary, Neff noted that the toxin's sequential elevations corresponded to deliveries of imported beer from Baker's brother-in-law, Walter "Wally" Pollock—Baker having evidently overcome his distaste for alcohol. Lafeyette Baker was as shady a character as ever wielded power in the Republic—but his demise, like Lincoln's, will keep theorists talking till Kingdom Come. Especially with this last detail: Wally Pollack was an employee of the War Department.

In his dank gas-lit chamber he had come to haunt the public imagination, fashioning himself as a burrowed beast of prey. Infamy and prestige were one and the same for Lafayette Baker—and from his basement lair, that prestigious infamy resonated like a tiger’s snarl.—from Lucifer's Drum

In Lucifer's Drum, my main character Major Nathaniel Truly works for the secret service of the U.S. War Department. His boss and occasional bane-of-existence is Colonel (later Brigadier-General) Lafayette C. Baker, one of those figures who could only have sprung from real life—especially from the Civil War, whose turmoil swept many natural-born scoundrels into positions of power. The grandson of a Revolutionary War hero, Baker was born in western New York in 1826. As a young itinerant mechanic, he landed in California around the time of the Gold Rush and joined San Francisco's ruthless Vigilance Committee, pledged to impose order and quash crime. Baker—gray-eyed, reddish-haired and a sharp dresser—stood out among the vigilantes, who recalled him as a crack pistol shot and paragon of physical stamina. These assets plus a disdain for legal niceties (and for liquor—rare in that time and place) would serve him well later on.

Lafayette C. Baker (1826-1868), chief detective

of the U.S. War Department and my main character's

problematic superior. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

Baker returned East in time for the Civil War's onset—an hour that gaped with nation-wide menace but also with opportunity, for men of certain skills. In July 1861, as the First Battle of Manassas loomed, he wangled an audience with General-in-Chief Winfield Scott. Baker proposed that he prove his worth with a daring, free-of-charge solo mission into northern Virginia, where he would learn the disposition of Confederate forces. Struck by his self-confidence, the elderly general agreed, giving him ten twenty-dollar pieces to finance the mission—which, even if you discount a detail or two of Baker's narrative, unfolded as an espionage drama and comedy in equal parts, requiring more nerve, luck and tenacity than a dozen ordinary spies could have shown.

His first effort to cross the Potomac was thwarted when federal troops arrested him and sent him to General Scott, who chuckled and told him to try again. He did so and was once more arrested by Union soldiers, though this time he talked his way out of it. The third try proved a charm, when he paid a farmer to row him to the Virginia side. Now on Rebel soil, he tramped westward through the summer heat but was nabbed by a pair of Confederate pickets. Before they could march him to their commander, he persuaded them to stop at a tavern where he got them drunk and gave them the slip. He kept on toward the main Southern encampment at Manassas but was caught yet again by a cavalry patrol.

Following a stern interview with General P.G.T. Beauregaud, he found himself in a stockade but then bribed an officer into letting him out for a spell, under guard. He got his guard drunk at a hotel bar and then took a leisurely stroll with him around the Confederate encampment, noting various units and learning the strength of each—including the Black Horse Cavalry, a special interest of General Scott's. When his tipsy, talkative guard wandered off, Baker wisely attempted no escape and returned on his own to the stockade. Confined again, he deflected his jailers' tricks to reveal him as a spy, as when a teenaged girl appeared with a whispered offer to smuggle out a note for him. (The girl was purportedly Belle Boyd, soon to be famous as "La Belle Rebelle" and the "Cleopatra of the Secession." Whether or not it really was her, the two would eventually cross paths—in reverse circumstances.)

Baker declared himself an innocent Knoxville, Tennessee native who had returned South to settle legal claims for a California minister—he had a partially forged letter to this effect. Still under suspicion, however, he was sent to Richmond by train and imprisoned there, wondering whether he would be hanged or just left to moulder. But after a few days, he found himself at the Spottswood Hotel, being interrogated by the President of the Confederate States himself, Jefferson Davis. Baker's nimble performance under pressure won him a parole within Richmond city limits, though he assumed that he was being watched. In an unlikely chance encounter, an old acquaintance called out his name in the street—then needed a ton of convincing that he had made a mistake. Alarmed, Baker decided it was time to cut bait. He managed to obtain a temporary pass to Fredericksburg.

His escape from Dixie was no less harrowing than his infiltration of it. Detained by Rebel cavalrymen north of the Rappahannock, he faked a limp to put them off guard, then stole a horse and a revolver as they slept. The next day, he evaded a Confederate search party by hiding in a haystack—into which an officer thrust his sword, coming inches from running the spy through. At last—starved, exhausted and with Rebel troops firing after him—he crossed the Potomac to safety in a stolen skiff.

This exploit earned Baker a job as confidential agent, first to the Secretary of State and later to the Secretary of War. His suspicious nature helped make him effective as he shifted from intelligence to counterintelligence, ferreting out Confederate spies, smugglers and sympathizers. Military authorities and the District of Columbia police took a dim view of his brusqueness as well as his contempt for due process. Still, Edwin Stanton's War Department raised him to "Special Provost Marshal" and commissioned him a colonel, lending greater scope to his zeal. He was therefore perfectly positioned when, in November 1862, President Lincoln sacked General George McClellan as commander of the Army of the Potomac, and McClellan's loyal hireling Allan J. Pinkerton left the scene as well, ending his role as the Union's chief spymaster.

THE RELENTLESS SCOTSMAN

. . . the war’s onset had found him restless and uncertain, vulnerable when Pinkerton’s telegraphed plea arrived from Washington: MOMENTOUS TIMES–GOOD MEN NEEDED–AMPLE PAY–PLEASE COME EAST. What if he had declined? Would the war tides have left him relatively untouched, sitting on his stoop outside Chicago? With Rachel still at his side?

"Fate," Truly murmured, "thy name is Allan Pinkerton.”—from Lucifer's Drum

Born in Scotland in 1819, Allan Pinkerton immigrated to Illinois at age 23, working as a cooper until he helped foil a group of counterfeiters who were operating near his settlement. That episode led to his becoming Chicago's first police detective and in 1850, with an attorney partner, founding the private detective agency that came to bear his name. With cutting-edge business acumen, the firm advertised itself with the logo of a single unblinking eye (from which the term "private eye" would hatch) and the slogan, "We Never Sleep." Pinkerton was a constant reader and autodidact, as well as a lifelong atheist. He hired the first-ever female detective, the intrepid Kate Warne, and other women after her. He also hired the Union's first African American agent, John Scobell. And in the 1870's, he began compiling the world's first criminal database—a "rogue's gallery," with clippings, rap sheets and mug shots.

Union detective Allan J. Pinkerton (1819-

1884)—effective on the home front,

out of his depth at the battlefront.

(Courtesy: Library of Congress)

Pinkerton's eventual close linkage with McClellan held one apparent contradiction: the former was a committed Abolitionist—his homestead was a stop on the Underground Railroad and he and his wife gave material support to John Brown—while the latter never hid his disdain for Abolitionism. Nevertheless, the relationship commenced after McClellan became chief engineer and vice-president of the Illinois Central Railroad, for which Pinkerton's agency solved a series of train robbery cases. The detective also became acquainted with the Railroad's top lawyer, Abraham Lincoln.

Thus, with the eruption of the Civil War, did Pinkerton land at history's red-hot center. In February 1861, charged with ensuring President-Elect Lincoln's safe arrival in Washington, Pinkerton obtained intelligence concerning an assassination plot in Baltimore, where Lincoln's train would have to stop. He personally shepherded Lincoln onto a secret train that made Baltimore by night, then onto another train that left before secessionist mobs could get wind of it. That summer, when his patron McClellan took command of the Army of the Potomac, Pinkerton became head of the Union Intelligence Service. He threw himself into plugging intelligence leaks—both the government and the army high command were spouting like sieves—and arresting Confederate spies in and around the capital. He and his agents did a highly creditable job, breaking up the Rose Greenhow Ring and sending that celebrated femme fatale to the Old Capitol Prison.

The Old Capitol Prison, First & A Street, Washington, D.C., present-day site of the

Supreme Court. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

But battlefield intelligence-gathering was another matter entirely—and when McClellan's lumbering Peninsular Campaign got under way in April 1862, Pinkerton's inexperience in that area bore bitter fruit. His methodology reflected McClellan's already delusional fears about the forces opposing him, greatly magnifying their numbers and reinforcing the general's innate caution—and turning the campaign into a bloody failure. (See "Until A Dictator: Lincoln vs. The RISODS," https://www.goodreads.com/author_blog.... In Lucifer's Drum, Truly recalls his frustration over this sorry performance and the final break it causes between him and Pinkerton.) For months, even through the sanguinary saga of Antietam, Lincoln found reason to tolerate McClellan's unchanging conduct, until he no longer could. And when the President at last fired Little Mac, handing Ambrose Burnside command of the Army of the Potomac, Pinkerton decided to pack it up. He spent the rest of the war investigating fraud among army supply vendors and other such cases.

BATTLEFRONT BRILLIANCE, HOME FRONT THUGGERY

In his brief, disastrous tenure as commanding general, Burnside appears to have done nothing innovative in the area of intelligence. But when Joseph Hooker succeeded him in late January 1863, that general charged Colonel George H. Sharpe of the 120th New York Regiment with building a new organization within the army itself. So was born the Bureau of Military Information. Multi-lingual and classically educated—and in Lucifer's Drum, the immediate superior of Truly's associate Captain Bartholomew Forbes—Sharpe was an attorney and also a low-level diplomat who had served in Rome and Vienna. Under his capable authority and with invaluable help from two subordinates—Captain John McEntee and the civilian scout "Captain" John Babcock—the Bureau gathered an effective stable of scouts and agents and began cross-checking intelligence from numerous sources. Its greatest triumph was in the immediate days before Gettysburg, when its web of informants and diligent sifting of reports yielded the size, composition and direction of Robert E. Lee's army.

The capable Colonel George H. Sharpe (left, 1828-1900) of the Bureau of Military

Information, with subordinates at Brandy Station, Virginia, early 1864. (Courtesy:

U.S. Army)

Sticking with military intelligence, Colonel Sharpe's superb outfit filled half of the post-Pinkerton vacuum. To fill the other half—civilian espionage on the home front—Lafayette Baker was named head of the War Department's new detective section, which he grandly dubbed the National Detective Police (a name that my character Nate Truly derides.) It never boasted more than forty regular employees, though its tentacles reached some 2,000 informants throughout the North. Granted wide latitude, Baker consequently ran a rather nebulous operation. Counterintelligence and Confederate spies were of course a major focus, along with smuggling—and it took only a vague suspicion for Baker to arrest someone and consign him or her to the grimy, crowded confines of the Old Capitol Prison.

Appalled observers pronounced it a Reign of Terror, comparing Baker to Napoleon's cold-blooded police director Joseph Fouche. Supposedly modeling his methods on those of another Frenchman—the legendary criminal-turned-detective Eugene-Francois Vidocq—Baker wore a silver badge engraved with the words "Death To Traitors" (a detail that, damn it, I wish I'd stumbled upon while researching my novel—it would have been a nice touch). Still, his activities were all over the map. Much energy went to tracking down fraudsters, deserters, bounty-jumpers and, increasingly, counterfeiters. Baker even raided saloons, bordellos and gambling "hells" around the District and tried to suppress the nascent pornography industry. It all sounds grimly dutiful—but persistent scuttlebutt had him extorting cuts from illegal money schemes that he uncovered, as well as pocketing funds from arrestees.

Working hand-in-glove with Baker was the wily superintendent of the Old Capitol, William P. Wood, a figure worth a book of his own. A model-maker by trade, the Alexandria, Virginia native had testified as an expert defense witness in the 1854 McCormick Reaping Machine trial, in which future Secretary of War Edwin Stanton beat back charges of patent infringement against his client. The Civil War revealed an enduring tie between Wood and Stanton, who became the former's patron and protector—often to a startling degree. (Of Wood's mysterious hold over the volatile Secretary, it was said, "Stanton is head of the War Department, and Wood is the head of Stanton.") Before his appointment as the Union's preeminent jailer, Wood was Commissioner of Public Buildings as well as a War Department operative. As bodyguard to Mary Todd Lincoln, he accompanied her on at least one of her notorious shopping binges (to Philadelphia, during which she bought the famous "Lincoln Bed.")

William P. Wood (1820-1903),

wily and sardonic, superintendent

of the Old Capitol Prison, later

head of the first formally named

United States Secret Service.

Physically small but powerful, Wood had served as a cavalryman in the Mexican-American War, though his rumored heroic exploits in that conflict remain just rumors. More certain is that while posted to New Mexico Territory, his commanding officer—future Union Brigadier-General and D.C. Provost Marshal Andrew Porter—sometimes ordered him strung up by the thumbs for one infraction or another. Later, presiding at the Old Capitol—and like Baker, holding a colonel's commission—he took obvious delight in bucking military orders (Porter's especially) and outraging the brass, whose efforts to retaliate were nevertheless quashed by Stanton.

Wood liked to receive incoming prisoners personally, his manner mixing graciousness with amused sarcasm. To an Englishman caught trying to pass through federal lines, he said, "I'm always glad to see your countrymen here!" Mockery was of course the least of an inmate's worries. In the dingy cells of the Old Capitol (present-day site of the Supreme Court), Wood and Baker employed time-honored and decidedly lowdown interrogation tactics. After days or weeks of isolation, a prisoner would be urged to sign a confession and, if he refused, be confronted with fake testimony. This would prompt him to speak in protest and perhaps elaborate on his case, after which the transcript would be read back to him with bogus passages inserted, leaving him confused, despairing and ripe for confession.

Confederate spy Belle Boyd, "the Cleopatra of the Secession."

(Courtesy: Getty Images)

Belle Boyd, age 18 at the time, described her own encounter with the Lafe & Willy Show during her stay in the summer of 1862, with Baker playing the menacing bad cop and Wood the unctuous good one. Boyd got off with relative ease, though, considering her refusal to confess or to take the oath of allegiance. When Baker's verbal bullying provoked a haughty retort from the girl spy, Wood took his colleague by the arm and said, "We'd better go—the lady is tired."

In her incomparable Pulitzer-winning book Reveille In Washington: 1860-1865, Margaret Leech said of Wood, "He was crafty and hypocritical, but his kindness was genuine." This quality showed in a grand gesture he made upon Belle Boyd's release, as part of a prisoner exchange. Having become engaged to a young Confederate officer and fellow inmate, Boyd had earlier been denied a day pass to shop for her wedding trousseau, so that joyous ritual remained unfulfilled. Sadness no doubt clouded her trip southward to Richmond, since freedom meant separation from her fiancee. But one happy surprise awaited her behind Confederate lines, when she received the trousseau that Wood himself had bought and sent after her under a flag of truce. Wood was especially solicitous with females, though he did have his limits. After a demanding note from the imperious Rose Greenhow, the superintendent wrote back, requesting that she "be kind enough to dispense with the God and Liberty style in your next pronunciamento."

Edwin M. Stanton (1814-1869), Lincoln's

volatile yet gifted Secretary of War.

(Courtesy: Library of Congress)

Part of historical fiction's challenge is doing justice to any real historical figures an author might use, figures he would have had a hard time inventing. And in Lucifer's Drum, I tried to do justice to William Wood, depicting him as someone who Nate Truly values but can't entirely trust:

At the Old Capitol, government supplies had a habit of disappearing. Wood’s nephew ran the prison commissary, and it was whispered that the two of them were robbing it blind. Though an unswerving Republican and Abolitionist, Wood seemed on good terms with the smugglers and blockade runners who he kept under lock. Even with some of the Rebel troops he appeared friendly, provided they weren’t rabid in politics or aristocratic in bearing. With the occasional lady prisoner he was indulgent unto silliness, and most new arrivals were in fact received kindly. To a prisoner brought in on dubious charges, his rights blown away like dandelion seeds, Wood pledged every effort for his comfort and eventual release, then arranged for a detective to pose as the fellow’s cellmate. A lapsed Catholic, he reveled openly in non-belief while encouraging Sunday services at the prison. Dubbing him “The Crown Prince of Duplicity” or—invoking the two-faced Roman god—“Janus the Jailer,” Truly was nonetheless grateful for Wood’s presence on Earth, with its reminder of life’s twisted sorcery.

HARD FATES AND TANGLED WEBS

Most likely with job security in mind, Baker tried to dig up dirt on his boss Stanton by tapping one of his telegraph lines. But he was found out. Despite Stanton's fury, he did not sack Baker but exiled him to New York City, placing him under the thumb of an Assistant Secretary. Immediately upon President Lincoln's assassination, however, Stanton summoned his wayward operative back to Washington. Baker's aggressive reputation recommended him to the task of tracking down John Wilkes Booth and his fellow conspirators—which in a matter of days, he accomplished. Hound-like, he and his men scoured the District and countryside and made key arrests. On April 26, 1865, thanks in large part to Baker's efforts, Booth and his associate David Herold were trapped in a barn near Port Royal, Virginia and the actor/assassin was fatally shot. Baker collected $3,750 in reward money and President Andrew Johnson commissioned him a brigadier-general. From that point, however, Baker's fortunes took a steep dive.

President Andrew Johnson (1808-1875), combative

impeachment survivor, consistently rated among

the worst Presidents. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

Amid the rancor between Johnson and Congress, Baker's promotion was never confirmed. And in February 1866, having discovered that Baker was spying on him, Johnson ordered him sacked. Newspaper condemnation of the uber-snoop's wartime excesses had meanwhile been mounting. (Baker's story makes me reflect on historical figures like him and the nations that hire them—in particular, nations that openly aspire to humane and democratic values. Faced with an existential threat, they will call upon brutal men to act out their natures and do whatever the country's survival seemingly demands. With eyes averted, they will advance and encourage these men—but once the threat subsides, will distance themselves from the tools of their dirty work. It's as if democracy, at least in extremis, requires a certain amount of hypocrisy.)

A year later, Baker published his colorfully unreliable memoir, History Of The United States Secret Service, in which he stated that Stanton had ordered him to spy on Johnson—a plausible enough claim, given the two men's mutual enmity. No doubt resentful over Stanton's throwing him to the wolves, Baker also charged that his erstwhile chief had suppressed John Wilkes Booth's diary. When a Congressional investigating committee forced Stanton to turn over the diary, Baker testified that eighteen pages had been cut out. Stanton denied maiming the volume, though speculation persists to this day about its allegedly missing content. When the power struggle between Johnson and Stanton culminated in the former's impeachment trial, Baker testified against the President. Johnson famously survived the attempt to remove him from office, prompting Stanton to at last resign as War Secretary.

The Pinkerton National Detective Agency's iconic logo,

origin of the term "private eye."

As for Allan Pinkerton—the years enhanced his reputation as a crime fighter, despite setbacks and personal compromise. His agency's largely successful pursuit of the train-robbing Reno Gang was eclipsed by its failure to track down Jesse James. In 1872, despite his Abolitionist convictions, the Spanish government hired him to help defeat a Cuban revolutionary movement that opposed slavery. The Pinkertons played an increasingly anti-labor union role, breaking up the violent Molly Mcguires in Pennsylvania's coal region. Upon Pinkerton's 1884 death in Chicago—variously ascribed to a stroke, to malaria, or to gangrene after he slipped on the pavement and bit his tongue—his sons Robert and William took over the agency. Under them and later under his grandson Allan II, it gained long-term notoriety in the Homestead Strike (1892), the Pullman Strike (1894), the Ludlow Massacre (1914) and the Battle of Blair Mountain (1921)—a tragic irony, given its founder's youthful pro-labor sentiments. The agency exists today as a guard/detective subsidiary of Securitas AB, a Stockholm-based security group.

As head of the Bureau of Military Information, George Sharpe contributed mightily to the Union cause. But Army of the Potomac Commander George Meade nearly ruined the Bureau, absorbing it into his command structure and interfering with its methodology. In part because of this, Confederate General Jubal Early's July 1864 raid on Washington, D.C. went undetected until it was almost too late. The near-calamity prompted Ulysses S. Grant, the supreme commander, to reorganize the Bureau and restore its full effectiveness. Sharpe was promoted to brigadier-general in February, 1865. At Appomattox, he had the job of issuing paroles to every Confederate soldier, including Lee himself.

Federal civilian scout "Captain" John Babcock and his horse Gimlet, 1862. Babcock

served under Pinkerton and later under Sharpe. He went on to become a prominent

Chicago architect. (Courtesy: Getty Images)

In 1867, having resumed his happy life in Kingston, New York, Sharpe was dispatched by Secretary of State William Seward to Europe, where he vainly pursued the alleged Lincoln assassination conspirator John Surratt. Grant, having become President, appointed him federal marshal for the Southern District of New York in 1869. Against great resistance, he conducted an accurate census and thereby revealed election fraud, helping to break the power of the Tweed Ring. He then served as New York’s surveyor of customs until 1878, after which he remained active in the law and in state politics. He died in 1900.

In the aftermath of Lincoln's murder, the relationship between William Wood and his benefactor Stanton came apart. Wood took up the cause of accused conspirator Mary Surratt (John's mother), whose innocence he proclaimed, and sought an audience with President Johnson. In this Stanton allegedly thwarted him, breaking a promise that Mrs. Surratt would be spared the gallows. She hanged along with three male conspirators. Wood cut his ties with the War Department but, in July 1865, was named head of the first formally named United States Secret Service, a division of the Treasury Department, with the central task of fighting counterfeiting. He hired former forgers and counterfeiters to help in the endeavor, making more than two hundred arrests before angrily resigning in 1869, over a reward money dispute.

Late that same year, Stanton died, just days after President Grant nominated him for the Supreme Court. In an 1883 series of articles, Wood stated that Stanton had committed suicide, haunted to the last by the ghost of Mary Surratt. This claim was widely believed, though never proven. (Amid the aftershocks of the assassination, instances of personal disaster and despair make that period seem truly cursed. Senators James Lane of Kansas and Preston King of New York, for two examples, committed suicide within months of each other. The pair had blocked the White House stairs when Surratt’s daughter Anna came to beg a presidential pardon.)

Hanging of Lincoln conspirators, July 7, 1865. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

Wood made another startling claim, this one dating from the outset of his and Stanton’s acquaintance. He said that as Stanton's expert witness in the McCormick Reaping Machine trial, he had perjured himself, altering an early model of the reaper in order to win the case. He did not say whether Stanton knew of the deception—but to many, the story explained how Wood had come to secure the powerful man’s sponsorship. (Another member of the defense team was Abraham Lincoln, toward whom Stanton was rudely dismissive; Lincoln nevertheless appointed him as War Secretary eight years later—a tribute to the President’s pragmatic ego, as well as his eye for talent.) Wood died in 1903 at the age of 83, a more durable rogue than his friend Lafayette Baker.

Because Lafe Baker was long dead. In his sensational memoir as well as his testimony before Congress, he had come off as less than credible. But in 1868, settled in Philadelphia and expressing growing fears for his safety, he was said to be working on another book—one that would expose Stanton as the orchestrator of Lincoln's assassination. This roundly refutable conspiracy theory has proven more stubborn than most. Regardless, he died suddenly on July 3, age 41. Meningitis was deemed the cause, though Baker's wife had her suspicions. In the 1960's, Professor Ray A. Neff of Indiana State University used an atomic absorption spectrophotometer to analyze strands of Baker’s hair. It revealed arsenic poisoning as the cause of death. Citing Mrs. Baker's diary, Neff noted that the toxin's sequential elevations corresponded to deliveries of imported beer from Baker's brother-in-law, Walter "Wally" Pollock—Baker having evidently overcome his distaste for alcohol. Lafeyette Baker was as shady a character as ever wielded power in the Republic—but his demise, like Lincoln's, will keep theorists talking till Kingdom Come. Especially with this last detail: Wally Pollack was an employee of the War Department.

Published on May 05, 2017 16:03

•

Tags:

allan-j-pinkerton, bernie-mackinnon, edwin-m-stanton, george-h-sharpe, lafayette-c-baker, lucifer-s-drum, william-p-wood