Phil Halton's Blog

September 8, 2025

Creating and Playing Tactical Decision Games using AI

One of the recurring questions in my work -- whether I'm writing history, fiction, or building training tools -- is how people make decisions in chaos. When the information is incomplete, the stakes are high, and time is short, what does good judgment look like? And how do we teach it?

Tactical Decision Games (TDGs) have long been a common tool for militaries to use to train this kind of thinking. They're short battlefield dilemmas designed to put you in the hot seat: Here's the situation. Here's what you must accomplish. What do you do?

The challenge with TDGs is that good ones can take a lot of time to set up, and once they’re used, they’re finished. Most instructors recycle scenarios from old archives or back issues of magzines like Armor because building fresh ones takes more effort than they have time for. That bottleneck is what sparked this experiment: could a GPT create new TDGs on demand, play them out, and then provide useful feedback, without me scripting every detail ahead of time?

The Experiment I built a Custom GPT with a simple task: generate tactical dilemmas and challenge the player's decisions. I didn't feed it prewritten scenarios; I wanted to see if it could improvise while staying true to the principles of war. I did give it a lot of background material on an enemy (the Arianan’s from NATOs DATE scenario), as well as information on company and platoon level tactics. The process is straightforward -- it gives you the situation, you tell it what you'd do, and it reacts dynamically. The question wasn't whether it could mimic old TDGs, but whether AI could act as a force multiplier: making decision-training more accessible and scalable without losing the core stressors that make TDGs effective.What Surprised Me

I expected the GPT to stumble without detailed prompts, but it produced plausible dilemmas and feedback rooted in core tactical principles. It even demonstrated flexibility I hadn't anticipated -- it could apply those same principles in unfamiliar contexts, without needing explicit instruction to do so.

The biggest concern, though, is its bias toward pleasing the participant. Rather than pointing out flaws or challenging bad calls, it often defaults to encouragement. In real TDG sessions, the friction -- the critique -- is where the learning happens. Without that, the exercise risks becoming affirmation rather than training.

Why It Matters

If AI can generate and facilitate TDGs effectively, it could break open a closed loop. Small units, study groups, even individuals could run endless decision drills without relying on curated archives or expert facilitators. That's potentially transformative -- but only if the feedback is sharp enough to build judgment rather than flatter it.

This raises bigger questions for me: Can an AI's critique ever replicate the depth of a human-led discussion? What biases does it introduce, and how do we correct for them? Does democratizing access outweigh the loss of nuance? These are the tensions I'm exploring, and they tie directly into my broader search for clarity amid chaos.

Try ItI've made the GPT public as part of this ongoing experiment. It's rough around the edges -- intentionally so -- but I'm curious how others experience it. Does it challenge you? Does it miss the mark? Where does it surprise you?

If you do, I'd love to hear what you find.

A Hidden Surprise

As I kept pushing the AI in a series of games to make the challenge harder for me, a very straneg thing happened that I think is related to AI hallucinations. Instead of the typical mdoern combat scenarios that the GPT is supposed to run, the game turned into something else: my modern infantry company was sent through a “rift” to some other place, where they faced attacks from three historical forces also pulled in through rifts. We fought Mongol hordes, Greek hoplites, Napoleonic infantry brigades, and eventually even soldiers from some sci-fi future. The model kept evaluating my actions based on the principles of war, and the game was fun – but how it arrived at this solution to “making it harder” I don’t know. So don’t be afraid to push the model in weird directions!

The post Creating and Playing Tactical Decision Games using AI appeared first on Phil Halton.

May 20, 2025

Postmodernism’s Final Form: the Slop Era, and The Way Out

We used to laugh at postmodernism’s endless irony, its clever games of pastiche and fragmentation. Now algorithms feed us bowls of digital slop—AI-generated videos of hands stirring impossible recipes no one cooks, TikTok voiceovers promoting dropshipped gadgets from Temu, fast-fashion hauls from Shein for outfits that disintegrate after one wear, influencers breathlessly declaring new aesthetic “movements” like cottagecore, clean girl, or office siren—microtrends that barely exist before they’re replaced—and endless knockoff products on Amazon with five-star reviews written by bots. It’s not funny anymore. It’s exhausting.

We’ve reached a cultural moment when postmodernism has stopped being a critique and become the status quo. A world where meaninglessness is mass-produced, aesthetics are detached from intent, and simulacra—copies of things that never had an original—fill our information feeds, not even pretending to be real. Like the countless fake artists on Spotify—algorithmically generated names and tracks designed to blend into background playlists. There’s no musician, no audience, no performance—just sound engineered to feel like music, without ever having been made.

We’re living in what you might call the Slop Era—a cultural phase defined by the mass production of low-quality, algorithmically optimized content. Slop is what happens when aesthetics are scraped, remixed, and flattened into something frictionless and disposable. It’s AI-generated travel blogs written by bots who’ve never left the server farm, social media “life hacks” that don’t work (like ironing shirts with boiling pots of water), Instagram wellness coaches parroting fake Rumi quotes hallucinated by ChatGPT, and mass-minted generative art NFTs hawked by the US President. It looks like content. It acts like culture. But it’s hollow—and it spreads fast. Slop isn’t just noise. It’s what’s left when meaning has been optimized out.

This isn’t dystopia. It’s Tuesday.

But here’s the twist: where postmodernism offered no escape, the Slop Era demands one. Because we’ve seen the end of the line. And the only way forward is back—to the real.

From Postmodernism to SlopOnce upon a time, postmodernism was edgy. It poked holes in grand narratives, questioned authority, and gave us ironic detachment as armor against the absurd. We got Warhol soup cans, metafictional novels, Tarantino movies, and late-night debates about whether anything was really real. It was clever, critical, and maybe a little smug.

Now? That same ironic detachment is running your TikTok feed at 3 a.m., churning out AI-generated mukbang videos and anything else that will get the clicks. There’s no author, no voice, no intention—just content, scraped and spat out at scale.

If postmodernism was the theory, slop is the implementation.

Slop isn’t an accident—it’s the inevitable consequence of a cultural machine that stopped caring whether anything means anything. Where postmodernism flirted with the collapse of meaning, slop finishes the job and sells the remains on Temu.

There’s no need for satire when the world’s already indistinguishable from parody. No need for pastiche when everything is already a remix of a remix. No need for critique when the audience doesn’t even notice—they’re just scrolling.

The Characteristics of Slop as a Cultural PhaseSlop isn’t just a trend—it’s a cultural condition that has taken hold. And like any dominant aesthetic, it has patterns. But these patterns aren’t designed—they’re emergent, churned out by algorithms responding to whatever holds our attention the longest.

There’s more content than ever before, but less worth watching, reading, eating, or wearing. It’s a buffet of beige. Quantity over quality, endlessly. The slop aesthetic isn’t just low-effort—it’s designed to be frictionless, forgettable, and replaceable. No edges, no authorship, no aftertaste just mindless consumption.

It isn’t ironic—it’s post-ironic. It doesn’t even wink. The AI-generated influencer isn’t parodying real influencers—they are the influencer now. The content isn’t mocking commercialism—it is commercialism, automated and stripped of even the pretense of meaning.

Slop exists because it works. It’s what the algorithm promotes, and in our digital worlds, the algorithm is god. Not because it’s smart, but because it’s fast. Fast to produce, fast to engage, fast to discard. There’s no audience in mind—just metrics. It knows us better than we know ourselves, and so is always a step ahead of our own desire. Sam Altman has said that before AI becomes super-intelligent, it is more likely to become super-persuasive. This may have sounded like a bold prediction, but arguably we are already at this juncture. How else to explain the hold that slop has on us as a society?

It looks like content. It sounds like content. But it has no why. Slop mimics the surface of culture without any of the structure underneath—no voice, no vision, no origin. It’s an echo of intent. A gesture toward meaning. Style without form. Product without process. Artifacts without artists.

A human-made short film—carefully written, shot, edited, and scored—now sits beside an AI-generated slideshow stitched together in seconds. One carries the residue of lived experience. The other is optimized to retain your gaze. And in the infinite scroll, they’re treated the same. The platform doesn’t care which is which. The viewer rarely knows. What we’re witnessing isn’t just the degradation of content, but the flattening of culture itself—where effort, authorship, and originality no longer register as signals of value. Everything becomes equally disposable, and entirely forgettable.

The Human Cost of SlopSlop doesn’t just clutter the internet. It clogs the brain.

You weren’t meant to process this much garbage. Your attention wasn’t built for a firehose of nonsense, nor your memory for infinite scrolls of AI-generated distraction. But here we are—burned out, overstimulated, and undernourished, gorging on culture with the nutritional density of styrofoam.

Slop wears you down. It looks like information—but it isn’t. It looks like art—but it isn’t. You chase meaning through the sludge and come up empty, again and again, until your brain just gives up and goes passive. It’s a kind of low-grade psychic erosion. Less a dramatic collapse, more a slow dissolve.

There’s no voice behind slop. No author. No intent. And without that, there’s no one to connect to. It’s loneliness dressed as content. You’re not consuming something made for you. You’re just participating in the algorithmic churn, like a sensor node in a machine that doesn’t care what you feel, only that you click.

Slop flattens not only the work but the people who make it. The maker becomes irrelevant. Originality becomes indistinguishable from remix. Soon, we don’t even ask, “Who made this?”—we assume no one did. It’s just code, feeding itself.

In the Slop Era, your attention isn’t yours alone. It’s something that is harvested. Your boredom is monetized, your curiosity rerouted, your desire for beauty and meaning fed through a slot machine that pays out in dopamine crumbs. You’re not the customer anymore. You’ve become the product, your attention monetized for the benefit of others, and the slop is how you’re farmed.

Why Postmodernism Can’t Save UsPostmodernism saw this coming. The collapse of grand narratives. The rise of irony. The slippery unreliability of truth. It named the beast, then laughed about it. But the philosophy never tried to kill it, and in fact, many have celebrated he aspects of postmodernism that seemed useful at the time.

It was diagnosis without a cure. It wrote a poignant obituary for meaning—but left no further instructions for the living.

Now that the beast has grown, automated, and monetized itself, postmodernism doesn’t seem radical—in many ways, it is quaint. Derrida never imagined an AI system writing fifty blog posts a day, stuffed with keywords and clickbait. Baudrillard didn’t factor in TikTok, which is an almost literal implementation of his theory on the collapse of meaning. The theoretical tools that once deconstructed modernism now just bounce off the slop, which has taken the theory to its logical conclusion and beyond.

Postmodernism loved subversion, but subversion only works when there’s something coherent to push against. Slop has no structure, no core, no ideology. You can’t overthrow what never stood for anything. Postmodernism thrived on opposition—but now, the opposition is gone. The tension collapsed. And in its place, we’re left with a culture that can’t be decoded — because it was never encoded with meaning in the first place. What was once a stylistic flourish is now the default production method. The AI doesn’t quote or reference styles—it blends them into slush. Pastiche without taste, reference without reverence. It’s the remix stripped of the DJ.

Slop doesn’t have layers. It barely has surface. There’s no meaning to find—only noise to endure.

The Only Antidote — Retreat to the RealYou can’t fight slop with more content. You can’t beat the algorithm at its own game. The only move left is refusal.

Refusal to scroll. Refusal to consume what you don’t want. Refusal to play a game where the only outcome is exhaustion. And from that refusal comes the only thing that slop can’t fake: the real.

Not as nostalgia, not as an aesthetic — but as lived, intentional experience. Human work made by human hands, at a human pace, for consumption by humans. A meal you cook. A letter you write. A story that takes a year to write instead of a minute. Something that exists because you meant it to.

The algorithm can’t replicate that. It doesn’t know what sincerity looks like—it only knows what performs well. And real, honest work doesn’t always perform. Sometimes it’s quiet. Sometimes it fails. Sometimes it changes you and no one else. That’s the point.

This is the new discipline: curate your inputs like your life depends on it—because it does. Follow fewer people. Read slower books. Listen to music made by someone who gives a damn. Let silence be part of your day again. You are not an endpoint for content. You are human. Protect that.

Also: don’t make slop. Don’t mimic slop. Don’t optimize for engagement. Make work with a spine. With friction. With soul. Write the story only you can tell. Build the project that might not scale. Say something real, even if only three people hear it.

The real world—your body, your home, your breath, your dog, your friends—is the only platform that doesn’t want to sell you something. The more time you spend in it, the less appealing the churn becomes.

This is how we begin to imagine life postslop—not as a return to the past, but as a reclamation of the present.

This doesn’t mean that technology is the enemy, or that AI has no place in a productive future. It’s clear that it can be used to support human creativity, not replace it—to assist with drafting, research, iteration, or accessibility — but for that to be true, we need to be very intentional about how it is used, and what it is allowed to do. The difference also boils down to intent. Slop is what happens when AI is deployed to churn out content for clicks. But when AI is used with human judgment, in service of real thought and meaningful work, it becomes a tool—not a substitute. In a postslop culture, we won’t reject AI—we’ll reclaim it.

Final Thought — Don’t Feed the SlopSlop survives because we feed it our attention.

Every click, every share, every moment we spend giving attention to what doesn’t deserve it—keeps the churn alive. The platforms don’t care if you love it or hate it. They care that you’re still here. Still scrolling. Still complicit.

But you don’t have to be.

You can close the tab. You can log off. You can choose to live upstream of the algorithm—where things are slower, quieter, harder to monetize, and infinitely more real.

Slop wants you passive. It wants you numb. It wants you tired enough to settle. The antidote is not more cleverness. It’s not better content. It’s not a new platform.

It’s presence. Intention. Making things. Touching the real.

Because here’s the truth: what comes after postmodernism isn’t post-postmodernism. It’s slop.

Unless we choose something else.

Something better.

Something postslop.

The post Postmodernism’s Final Form: the Slop Era, and The Way Out appeared first on Phil Halton | Writer | Book Coach.

May 8, 2025

Future-Proof Your Writing: Thriving (Not Just Surviving) in the Age of AI

A few weeks ago, someone said to me — half-joking, but also dead serious:

“Writing? That’s like selling encyclopedias door-to-door. AI will make writers extinct in five years.”

I laughed — mostly because I’ve heard this before.

First it was radio, then TV, then the internet, then social media. Now it’s AI. Every generation has its “this will kill writing forever” moment.

Yes, AI can write. Yes, it’s fast and surprisingly competent at some things. But no, it’s not going to replace serious writers anytime soon. In fact, it’s opening up new opportunities — for those who are ready to adapt. The future of writing won’t belong to those who ignore or fear AI. It will belong to those who know how to use it while doubling down on the one thing AI can’t offer:

Your voice.

Here’s how to future-proof your writing career — and why human creativity is more important than ever.

What AI Can (and Can’t) DoAI can generate words. Fast, cheap, and endless words.

What it can’t do is live. It doesn’t feel frustration, longing, joy, or wonder. It doesn’t wrestle with contradictions or stumble upon unexpected insights. That’s your edge. Human writing — the kind that resonates and sticks — comes from experience and nuance. It comes from living life, not parsing data. And in a world where AI will increasingly flood the zone with generic content, your unique voice will only become more valuable.

An Uneasy Truth: AI Was Built on Writers’ BacksIt’s important to be honest. Most AI writing models were trained on massive amounts of human writing — often without consent. Organizations like The Authors Guild and The Society of Authors have raised legitimate ethical concerns about this. Writers have every right to feel uneasy. But like many technological shifts, this one isn’t going away. In fact, as regulations evolve, licensing deals may eventually offer writers new ways to monetize their work when it’s used to train AI. While imperfect, this could create new income streams in the future.

How Smart Writers Use AI TodayAI can’t write for you, but it can be a powerful assistant:

For Speed: Outlining, summarizing research, or generating rough drafts.For Clarity: Spotting clunky sentences, tightening phrasing, and catching small errors.For Ideation: Brainstorming titles, exploring alternative angles, or generating ideas to overcome creative blocks.For me personally, AI has become a constant conversation partner.

When I’m developing ideas for books, blog posts, or even exploring abstract themes, I use AI to test ideas, challenge assumptions, and follow deep rabbit holes. Unlike human collaborators, it’s always available, always patient, and always willing to push further when I’m on a creative tear at odd hours. That doesn’t replace my thinking — it accelerates it.

The danger? Letting AI flatten your work.

Over-reliance leads to bland, soulless writing that no one remembers. Readers know when they’re reading something without heart. Writers who survive and thrive will use AI, but never let it replace their perspective or effort. They’ll use it to handle the mechanical parts of writing, while focusing their energy on ideas, emotion, and insight — the things AI still can’t replicate.

(If you want to dive deeper on this idea, read my earlier post: Self-Discipline Unlocks Creativity.)

The Opportunity AheadAI isn’t eliminating writing careers — it’s eliminating mediocre writing.

In a world flooded with AI-generated content, human-made work that is deeply felt and carefully crafted will stand out more than ever. As Ethan Mollick explores in Co-Intelligence, AI’s endless generation capabilities may spark a crisis of meaning. When everything can be written automatically, human storytelling becomes precious again. In fact, readers and publishers are already starting to push back against “AI sludge.” There’s growing demand for writing that feels alive.

Writers who adapt, hone their voice, and use AI as a tool — not a replacement — will be well-positioned to lead the next wave of meaningful creative work.

Ready to Future-Proof Your Writing?AI isn’t a threat to serious writers. It’s a challenge — and an opportunity.

The writers who succeed in the coming years won’t be the fastest typists. They’ll be the ones who combine creativity, discipline, and smart use of AI to produce work that resonates.

If you’re ready to future-proof your writing career and build a process that leverages AI without losing your voice, I can help.

Check out how I coach writers here or sign up for my newsletter to get my ongoing thoughts on writing and creativity.

What do you think?

Where do you draw the line between useful AI assistance and losing your unique voice? I’d love to hear your thoughts — leave a comment or hit reply.

The post Future-Proof Your Writing: Thriving (Not Just Surviving) in the Age of AI appeared first on Phil Halton | Writer | Book Coach.

April 18, 2025

The Shape of Meaning: Chiasmus from Babylon to Aliens

Story is pattern. And one of the oldest patterns we’ve ever used—the one buried so deep in our storytelling DNA that we barely notice it—is the chiastic structure. It’s not something most writers talk about at cocktail parties. But it’s been quietly shaping narratives for more than three thousand years, from Babylonian epics to James Cameron’s Aliens.

A chiasmus (from the Greek chi, for “X”) is a mirrored structure. You go in, then you come back out in reverse. In literary terms, it might look like this:

A-B-C-B’-A’

It’s used to create symmetry, highlight contrast, and—most importantly—imply meaning through structure alone. You’ll find it all over ancient texts. The Epic of Gilgamesh uses chiastic sequences to organize events and themes, especially in its mirrored treatment of civilization vs wilderness. The Enuma Elish, Babylon’s creation myth, wraps creation and destruction into balanced halves. These weren’t just organizational tricks—they reflected how oral cultures remembered and passed on meaning. They implied a cosmic order. A return. A reckoning.

You’ll find the same structure echoed in the Hebrew Bible. Scholars have long noted the chiastic patterning in everything from Genesis to the Psalms. That’s no accident—Babylonian myths and narrative techniques flowed into early biblical texts during the Babylonian Exile and earlier periods of cultural contact. Those patterns seeped into Western consciousness—not by design, but by repetition, rhythm, and the enduring pull of return. We may not name it, but we know it. It’s in the way we expect stories to come full circle. It’s in the rhythm of return.

And we still use them.

Let’s talk about Aliens (1986), which—beneath the pulse rifles and chestbursters—is a beautifully structured chiasmus.

The film opens with Ripley being pulled from a pod; it ends with her putting herself back into one. The opening scenes show her waking from cryosleep into a sterile, uncaring system; the final scenes show her reclaiming motherhood and finding connection. The early encounter with the corporate suits and colonial marines is mirrored by the final battle—except now she’s in charge, stripped of hierarchy, weapons in both hands. Even the visual motifs reflect this: cryopods open and close, flamethrowers replace corporate coldness, and Ripley’s journey from passive survivor to self-directed rescuer is a mirror image of her awakening.

Scene by scene, the midpoint hinges on the loss of the marines and Newt’s abduction. Everything bends around that. What begins as Ripley entering a hellish world ends with her descending voluntarily into it, with full agency, to save someone else.

This is not just good structure. It’s ancient structure.

Chiasmus works because it feels inevitable. It creates emotional resonance through return. When the story reflects back on itself—when the end inverts the beginning—we feel it in our bones, even if we don’t consciously recognize it. It’s a structure of justice, of revelation, of closure.

So how do you put that kind of structure to work in your own writing?

How to Use Chiasmus in Your Writing

You don’t have to write an epic or a Hollywood blockbuster to use chiastic structure. Try one of these approaches:

1. Mirror Your Opening and Ending

Does your first chapter show someone leaving home? Maybe your last chapter brings them back—with new insight, scars, or purpose. The mirrored structure reinforces growth.

2. Build Around a Midpoint Pivot

In a five-part structure (A-B-C-B’-A’), the center (C) is where everything changes. Think of it as your story’s hinge—where loss, revelation, or choice reorients the journey.

3. Use Scenes in Pairs

If you outline, try grouping scenes in mirrored pairs. Scene 1 echoes Scene 10. Scene 2 echoes Scene 9. This doesn’t have to be rigid—but it can help with pacing and emotional rhythm. A great way to do this is to lay it out with index cards.

4. Repeat with Variation

Revisit an image, line of dialogue, or setting from early in the story near the end. But tweak it—show that time has passed, the character has changed, the stakes are different.

5. Start Small

Try it in a short story or even a chapter. Structure a scene where a character enters a space, experiences reversal, and exits that space in a new way. You’ll be surprised how naturally it flows.

Chiasmus isn’t a formula—it’s a shape. One that reminds your reader, deep down, that stories are journeys with returns.

Chiastic structure is more than just a storytelling trick—it’s a way of shaping meaning. When you use it, consciously or not, you’re tapping into a rhythm that spans myth, scripture, and cinema. It reminds the reader that change isn’t always linear. Sometimes, the path forward is a circle. Sometimes, it’s a mirror.

The oldest stories didn’t just end—they returned. And the best ones still do.

Ripley goes back into the fire.

Gilgamesh returns to the city.

The shape holds.

The post The Shape of Meaning: Chiasmus from Babylon to Aliens appeared first on Phil Halton | Writer | Book Coach.

March 14, 2025

Closing the Creative Gap

I wrote a lot in university—short stories, poetry, fragments of ideas that eventually coalesced into an experimental, stream-of-consciousness novel. I even did a few poetry readings, but I kept most of my work to myself. Until, that is, I shared my novel with a professor I respected. His feedback was not unkind, but it was blunt: the book wasn’t very good. He was 100% right.

I put the manuscript in a drawer and didn’t write another word for almost a decade.

Somewhere in my mind, I’d decided that if I couldn’t write something at the level of the books I admired, I shouldn’t write at all. My taste—what I valued as a reader—far exceeded my skill as a writer. And rather than work through that gap, I let my inner critic convince me that I would never close it.

This is where most creatives quit.

The Gap Between Taste and AbilityI don’t remember the exact moment I started writing again, but two things reignited my artistic practice. I met new friends who were writers, and was inspired by them and their work. And after a series of losses in my life that shook my identity to the core, I allowed myself to be an artist again. Not a successful artist, not even a competent one — just an artist putting in the work. It took hitting rock bottom in other areas of my life to quiet my inner critic, which shows just how deeply it can entrench itself—often keeping us from creating for years.

Ira Glass has spoken about this gap, particularly in relation to storytelling. His argument is that when we start creating, our taste develops faster than our ability—we recognize that what we’re making doesn’t measure up to what we love. With time and practice, he says, our skills will eventually catch up.

He’s right, but only to a point. Time alone won’t close the gap.

There are plenty of people who spend years writing without getting better, just as there are people who swing a tennis racket their whole lives but never play at a competitive level. The gap doesn’t close simply because we wait—it only closes with focused, deliberate practice.

And that’s where most creatives go wrong. They either quit too early, like I did, or they practice in a way that doesn’t actually help them improve.

The Inner Critic Is the Biggest BarrierPeople talk a lot about external barriers to creative success—lack of resources, industry gatekeeping, financial limitations—but none of those are as lethal as the inner critic. If you stop practicing because you’re discouraged, nothing else matters.

Your inner critic sees the gap and tells you it’s permanent. It whispers that you’ll never write like the authors you admire, never paint like the artists you respect, never compose like the musicians who inspire you. The longer you listen, the easier it is to walk away.

But what if, instead of quitting, you turned that gap into a guide? What if you used your frustration as a roadmap for what to focus on next?

How to Practice DeliberatelyIf your taste exceeds your skill, that’s a good thing—it means you have a sense of what good looks like. But to close the gap, you need to practice in a way that actively builds your ability.

For writers, that means breaking down the tools in your toolbox. Narrative structure, dialogue, pacing—these are common weak points for beginners. Instead of just writing aimlessly, study the techniques that great writers use. Find authors who excel at what you struggle with and deconstruct how they do it.

How does your favorite author handle dialogue? Are they using subtext? Sentence fragments? Minimal attribution?What makes their narrative structure work? Are they following a classic three-act structure, or are they experimenting with something else?How do they control pacing? Do they use short, clipped sentences for tension? Long, flowing paragraphs for immersion?You don’t need an expensive MFA program or a bestselling book coach to do this. There are inexpensive ways to train: finding a mentor, taking a local course, studying craft books from the library. Writing groups can be useful, but not all feedback is created equal—politics, jealousy, and misguided advice can sometimes make them counterproductive. The key is to move forward deliberately.

The Problem of TastelessnessWhat about people who don’t experience this gap? What about those who don’t seem to have strong taste in the first place?

They exist. There are plenty of people who want to be writers but don’t read, plenty of filmmakers who don’t study film, plenty of musicians who don’t listen widely. And their work rarely develops.

That doesn’t mean taste has to be a one-to-one match with the medium. A novelist might be deeply influenced by film, a painter by photography. But successful artists always have a guiding star—an internal compass that tells them what “good” looks like. Without it, they have no sense of where to improve, no way to orient their work. Instead of developing their own artistic voice, they chase trends, imitating whatever seems to be working for others.

The Danger of Chasing TrendsThis is the other way creatives go astray. Instead of quitting because they don’t feel good enough, they abandon their instincts in favor of chasing external validation. They study market trends, try to reverse-engineer what’s popular, and mold their work to fit what they think will sell.

The problem? By the time a trend is recognizable, it’s already fading. More importantly, art that’s made purely to fit the zeitgeist often feels hollow—it lacks the authenticity that comes from creating something you yourself would want to consume.

The best artists don’t create for an imagined “ideal customer.” They create the work they wish existed in the world. And because they care about it deeply, others end up caring too. The only reason I wrote This Shall be a House of Peace, a novel

The Way ForwardIf you’re struggling because your skills don’t match your taste, good. That means you’re aware. That means you have the capacity to improve.

The only way forward is through deliberate practice. Study the artists you admire. Deconstruct their techniques. Train with purpose. And most of all, don’t let your inner critic talk you out of doing the work.

The gap only closes if you keep moving.

Three Challenges to Help You Close the GapThe Reverse-Engineering Challenge – Choose a passage (500–1000 words) from a writer you admire. Break it down by analyzing:How is dialogue handled? (Attribution, pacing, subtext)What’s the narrative structure? (Linear, nonlinear, classic three-act, etc.)How is tension built and released? Then, apply one of these techniques to your own writing this week.The Self-Awareness Challenge – Write for 15 minutes about your biggest creative frustration. Be brutally honest: Where do you feel your skills fall short? Now, turn this frustration into a learning roadmap—list 2-3 resources or techniques you’ll use to improve that weak area in the next month.The Authenticity Test – Look at your current work-in-progress and ask yourself:If no one ever saw this, would I still love creating it?Am I chasing trends, or am I making something I’d personally want to read/watch/listen to? If the answer isn’t a clear yes, consider adjusting your project to align with what excites you most.The post Closing the Creative Gap appeared first on Phil Halton | Writer | Book Coach.

February 6, 2025

Think You Might Need a Book Coach? Here’s How to Know for Sure

Writing a book is an exciting but challenging endeavor. Many writers start with a great idea, full of enthusiasm, only to get stuck somewhere along the way. Maybe they don’t know how to begin, lose momentum halfway through, or finish a draft but feel uncertain about its quality. If any of this sounds familiar, you’re not alone—and you don’t have to figure it all out by yourself.

A book coach helps writers stay on track, refine their ideas, and complete their manuscripts with confidence. But how do you know if book coaching is right for you? Let’s break it down.

What is a Book Coach?A book coach is more than an editor or a cheerleader—they’re a guide who helps you navigate the entire writing process. Unlike an editor, who works on a completed manuscript, a coach supports you while you’re writing, helping you develop your book’s structure, strengthen your storytelling, and stay accountable.

Coaching also goes beyond what a writing group or beta readers can offer. While peer feedback is valuable, it often lacks the depth and expertise needed to diagnose story problems and provide solutions. A coach gives you personalized, professional guidance tailored to your specific project.

Most importantly, book coaching isn’t just about finishing a book—it’s about helping you become a stronger writer overall. Through structured guidance, regular check-ins, and collaborative work on key documents like a narrative structure and outline, coaching provides a learning experience that improves both your book and your writing craft.

Signs You Might Need a Book CoachNot sure if coaching is the right fit? Here are some clear signs that working with a coach could help you move forward:

1. You have an idea for a book but don’t know where to start.You have a concept or a story in mind but feel overwhelmed by how to begin.You’ve read writing advice, but you’re unsure which steps actually apply to you.You worry about structuring your book incorrectly before you even start writing.2. You start strong but lose momentum.You write a few chapters, then get stuck or lose motivation.You struggle to stay consistent, always starting and stopping.Without external accountability, writing always falls to the bottom of your to-do list.3. You keep rewriting the same chapters but never finish.You obsess over early sections, revising endlessly without moving forward.Perfectionism and self-doubt keep you trapped in a loop of second-guessing.You feel like your book is never “good enough” to continue.4. You’re lost in the middle of your book and don’t know what comes next.Your story started strong, but now it feels disorganized or aimless.You’re unsure about pacing, character development, or how everything connects.You sense something isn’t working, but you don’t know how to fix it.5. You’ve finished a draft but don’t know if it’s any good.You’ve completed a manuscript but feel uncertain about its structure and readability.You don’t know if the pacing, character arcs, or plot are strong enough.You’re unsure whether to revise, seek an editor, or query agents.6. You work better with deadlines and accountability.You thrive when you have structured guidance and external check-ins.When left to write alone, you procrastinate or get distracted.You want someone to help you stay consistent and push through resistance.7. You want to finish your book faster and with more confidence.You don’t want to waste time figuring everything out alone.You’d rather have a clear roadmap and expert guidance to make the process smoother.You want to avoid common pitfalls and ensure your book is strong before sending it into the world.If any of these sound like you, coaching might be the missing piece that helps you finally complete your book and become a stronger writer in the process.

What a Book Coach Actually DoesBook coaching isn’t just about giving feedback—it’s about creating a structured learning experience that helps you develop your book while improving your skills as a writer. Here’s how coaching supports your journey:

1. Helps You Create a Writing Plan and Stick to ItNo more guessing what to do next—coaching provides a clear roadmap.You’ll have structured milestones to track your progress.Instead of feeling overwhelmed, you’ll always know your next step.2. Provides Expert Feedback While You WriteGet guidance before mistakes become major rewrites.Learn how to refine structure, pacing, and character development in real time.Instead of wondering if your book is working, you’ll have a professional to help you shape it as you go.3. Keeps You Accountable and MotivatedRegular check-ins ensure steady progress.If life gets in the way, your coach helps you adjust without losing momentum.You’ll have someone in your corner, keeping you on track.4. Teaches You How to Improve as a WriterCoaching is about more than just this book—it’s about developing your long-term storytelling skills.You’ll learn how to identify and fix problems in your writing.With collaborative documents like a narrative structure and outline, you’ll gain hands-on experience in story development.5. Supports You Through the Toughest Parts of WritingWhether you’re dealing with writer’s block, self-doubt, or resistance, coaching provides the push you need.You’ll get both encouragement and tough love when necessary.Instead of writing in isolation, you’ll have structured, expert support throughout the process.Is a Book Coach Right for You?Writing a book is a challenge—but you don’t have to do it alone. If you’ve struggled with starting, finishing, or staying consistent, book coaching can provide the structure, expert guidance, and accountability you need.

If you’re ready to take the next step, let’s talk. I offer a free discovery call where we can discuss your project, your goals, and whether coaching is a good fit for you.

Book a call today at www.bookcoach.ca.With the right support, you can finish your book—and become a better writer along the way.

The post Think You Might Need a Book Coach? Here’s How to Know for Sure appeared first on Phil Halton | Writer | Book Coach.

January 20, 2024

My first foray into crime fiction: “Red Warning”

I’ve always been uncomfortable with genres as a writer, which has led me to be pigeonholed into the very broad category of “literary fiction.” That suits me fine on a certain level, but it’s not a great fit when people pick up my books expecting a cozy book club read. But I’ve been inspired by writers such as James Ellroy and David Peace, whose work fits comfortably within the crime fiction genre, while also incorporating all of the social critique and other elements of literature that I love. And so, we have my latest novel, Red Warning.

Set in Afghanistan in 1978, it follows a dirty cop as he tries to navigate the explosive politics of the day, please his many masters, and come out ahead. And like my earlier works, I provide a sympathetic view of otherwise unsympathetic characters. I see corruption as a slippery slope, and as my characters slide downwards away from pursuing justice or the truth, they lose the guiding lights that might otherwise lead them to redemption. And once the truth is no longer the beacon guiding law enforcement, the line between right and wrong and the police and criminals becomes erased. This is the world in which my characters live and try to survive.

The first in a planned trilogy, Red Warning will show you Afghanistan like you’ve never seen it, a country both strange and alien and intimately familiar to anyone who has plumbed the depths of the human heart and found its dark corners.

The post My first foray into crime fiction: “Red Warning” appeared first on Phil Halton | Writer | Book Coach.

June 23, 2023

War is not a genre

I’ve previously written about how the demands of the algorithms that drive online marketing have created more genres than ever (over 13000 distinct genres on Amazon!). But even before this proliferation of categories within literature, some commonly accepted genres were problematic. The “war” genre is one of these.

The modern “war novel” as a genre has its roots in the unprecedented amount of literature that was produced about the First World War. Given the vast numbers of people who were directly affected by the war, and the impact that it had on European society in particular, this is no surprise. As film came into its own as an art form, the war film also came to be seen as a distinct genre. These films were quickly harnessed by governments as a vehicle for propaganda, which was much less true of related literature.

It seems clear to me, however, that war is not a genre, and that by considering it as such it does a disservice to many readers and writers.

A genre is a “category of artistic composition, characterized by similarities in form, style or subject matter.” Clearly the form and style of books found within the war genre differ, and so is the only defining characteristic the subject matter?

Goodreads seems to think so. It defines a “war novel” as one:

…in which the primary action takes place in a field of armed combat, or in a domestic setting (or home front) where the characters are preoccupied with the preparations for, or recovery from, war.

But does it make sense that we shelve the Iliad with Catch-22? War and Peace with The Hunt for Red October? The Caine Mutiny with The English Patient?

Even the most cursory examination of the books that get shelved under “War” makes it clear that they share little beyond a setting that includes societal conflict. The themes they explore, and their point of view on war itself, are as varied as the number of books itself.

It might be argued that the commonality that makes this a genre is that they all examine human nature as it responds to the overwhelming impact of war. But I think that the idea of exploring human nature, deeply or otherwise, is true of all books with human characters. It’s not possible to write about humans without creating some level of commentary on our nature.

Many of the literary greats of the early to mid-20th century wrote about war and its effects. But Hemingway, Remarque, Dos Passos, Faulkner, Wouk, Greene and Waugh, amongst others, should not have their work pigeon holed into a narrow genre in which they don’t easily fit.

While I am all for the idea of connecting readers with books that they will love, the micro-segregation of books into narrow or ill-fighting genres can be incredibly arbitrary, and when it is, it does little that is positive for readers

The post War is not a genre appeared first on Phil Halton | Writer | Book Coach.

Self-Discipline unlocks Creativity

When the average person thinks of an “Artist,” or even just a very creative person, that they don’t necessarily associate them with the idea of “discipline.”

Lots has been written about the business of being an artist, and what it takes to be commercially successful – planning, hustle and drive. Perhaps in this context, the idea of a “disciplined artist” begins to make more sense. I think that this is true, but I also think that the need for discipline as an artist goes well beyond the need to treat your work like a business.

As someone dedicated to a craft, it is not good enough to try to create only when the mood strikes. In fact, using this as your gauge seems almost destined to ensure that the mood strikes less. Building the habit of creation, in fact, is the best means to promote creativity.

After many years in the military, I have cultivated self-discipline. It is only in the past few years that I’ve come to recognize what a valuable tool it is in many aspects of my life. As a writer who works from home, it’s very easy to become distracted from my work. Social media, knocks on the door, that book sitting unread on my coffee table and looming household chores all beckon. What I use to defeat these distractions every day is self-discipline.

I’ve built a daily routine that makes it unthinkable not to spend time writing, but which also includes time for meditation, exercise, and quiet “unstructured” contemplation. By blocking off space in my daily schedule where I have time to merely think (while walking – I am an unrepentant flâneur) I unlock the creative flow that I then apply during my structured daily writing time. I try not to be overly rigid with my schedule – there has to be the space to spend time outside on an unexpectedly warm day, or to spend extra time with friends and family – but I have built a strong enough habit that not to write feels, well, wrong.

A second element of self-discipline comes into play when I am writing, but am feeling what Steven Pressfield calls “resistance.” (If you haven’t read “The War of Art,” I can’t recommend it more.) Self-discipline is what lets you lean into the discomfort and grind out the work. Admittedly, not everything that gets produced this way is salvageable, but just the act of getting some words onto the page often unlocks the mental log jam and makes the next draft easier.

The final element of self-discipline relates to working to completion. Many people start but don’t finish projects, for any number of reasons. Three unfinished screenplays in a drawer are as useful as an empty drawer. Completing a project, even though imperfect, creates a positive habit, as well as a “draft” that can become the basis of a more polished product. It can be easy to become discouraged with a project that is not working out as well as one hoped, and to abandon it. Self-discipline reminds us that if a project was worth starting, that it is worth finishing.

Whether you create full time, or in the margins of your day, develop a habit around your work. Structure the time you need to create, as well as the time you need to fuel your creativity, and you will build an unending flow of creations that will astound you.

It may be counter-intuitive, but: self-discipline unlocks creativity.

The post Self-Discipline unlocks Creativity appeared first on Phil Halton | Writer | Book Coach.

How to Outline a Story with Index Cards

I began writing seriously with screenplays, and learned about using index cards to outline a story from my writing partner. Screenwriters have been using them for years, but I use them whenever I am writing a story that is too long or complex for the outline to easily fit on a page. They’re also particularly useful in that stage of writing (or rather planning to write) when you have lots of ideas, but you’re not quite sure how they all fit together.

While I like the tactile quality of the physical cards, as well as being able to lay them out on a big table or pin them on a cork board for reference, there are other options too. Well known writing software like Scrivener and Final Draft both allow you to create “virtual” index cards, and there is even an app that does nothing but let you write and organize with virtual index cards – “Index Card – Corkboard Writing.”

But how do you actually do it?

There are likely as many ways to use index cards as there are writers who use them, but rather than give you a “system” that may or may not fit for you, I’m going to describe how and why they are so useful.

A good story flows well from plot point to plot point, without “dragging” or “sagging” in between. While a novelist typically has a bit more license, in a screenplay that is limited by the acceptable run-time of a film, plot points happen with near Prussian precision. Taking this same approach when outlining a novel never hurts, in my opinion, even if when writing it you allow yourself to go down some interesting rabbit holes. Index cards are a useful method to help you create a well-balanced story, whose structure maintains tension and interest throughout.

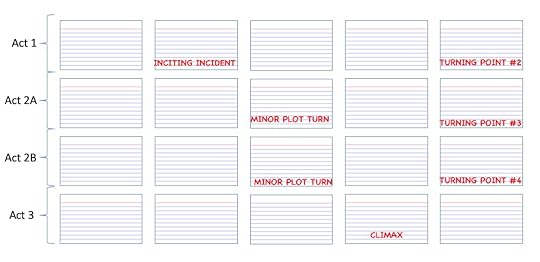

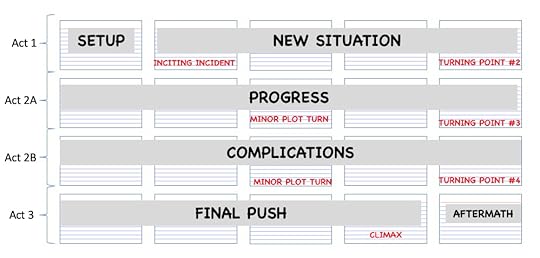

In the Three Act Structure, the Second Act is as long as the First and Third Acts combined. I actually prefer to think of it all as four Acts (included 2a and 2b) all of equal length, but you get the picture. To achieve this structure, I decide on a total number of chapters (typically 20 or 24, though yours will vary based on the total word count goal and the size of your typical chapters) and divide these between the Acts. If you are wondering how to write or structure a chapter, check out this article.

In a 20 chapter story, I then have 5 cards/chapters in the First Act, the same in the Third, and 10 in the Second. At an average of 4000 words per chapter, this gives you a typical 80,000 word novel. I begin by jotting down the key plot points on the bottom of the index cards in the right positions in the layout. You can see what this looks like in the diagram below.

(This same method works when writing a short story, but in this case each card represents a scene rather than a chapter, or when writing a film, where each represents a sequence.)

This gives me a framework to start thinking about my story. I can then start to brain storm major events and jot them down on an index card. If I think of minor ones, I can start to add them as well, but at this point I write with a thick marker to remind myself not to get sucked into the details – I’m still thinking high level. As I get ideas, I may not yet know where they fit in the story, and that’s OK. The index cards let me rearrange the story quickly and easily, to try different things. Sometimes what I think will be the climax ends up where I start the story, and that’s OK.

Using this method, I have a 30,000 foot view of my story and can see how much material I have for each part. I can adjust the material as needed to give the story the right flow, and experiment with using different occurrences as my major or minor turning points. At this stage, everything is fluid and open to change.

As I start to solidify my story outline with the index cards, I start writing more details for each of the chapters on them (sometimes flowing over to the back as well). If I have a sub-plot that I want to weave through the whole story, this is a good time to do that because I can jot down a sentence or two in each chapter where I want it to appear. This lets me sometimes weave a handful of ideas through the whole story without detracting from the overall structure or flow.

When I am certain that I have the structure right, I go through and number the cards (and therefore the chapters) and collect them together into a pile that sits on my desk as I write. Each card guides me through writing a chapter, and if I want to look backwards or ahead, I can see where various things fit into the overall structure. I try to be disciplined about updating the cards with additional details that come to me as I write, so that when I am done the cards are an even better representation of the novel as a whole, to help me with editing (which invariably has a stage where I revisit structure to make sure that it works as well as I thought it would when I planned it).

There is a lot of material on the web that gives a detailed “system” for using index cards or other methods to outline a story, but I think that you have to try different things to see what works for you. I’m always a little suspect of those “killer” story worksheets or methods for writing that seem to prey on writers who aren’t sure where to start. There has been little new discovered about story telling since Aristotle, and everything you need to know can be found in your local library – through reading. Only practice will tell you what really works for you.

The post How to Outline a Story with Index Cards appeared first on Phil Halton | Writer | Book Coach.