Doug Sundheim's Blog

February 9, 2021

Who Are You At Your Best?

Originally published February 4, 2021 on Forbes

At your best, you choose love.

You feel fear, or anxiety, or selfishness, or anger, or hate. But you choose love.

You choose love because you’ve chosen fear and anxiety before. And it paralyzed you.

You choose love because you’ve chosen selfishness before. And it isolated you.

You choose love because you’ve chosen anger and hate before. And it poisoned you.

Your eyes are wide open. You know that choosing love in a look-out-for-number-one world isn’t easy. No one would blame you if you didn’t choose love. But you’re not doing it because it’s a nice idea; you’re doing it because it’s necessary. You realize choosing anything else is a dead end.

You choose love because when you look into the eyes of your family, your friends, your colleagues, and your neighbors, you see yourself. When you look into the eyes of people across the nation and world, you see yourself. And even, in your clearest moments, when you look into the eyes of your enemies, you see yourself. You might not see yourself in their behavior, but you see yourself in their struggle. You see yourself in their humanity. It’s jarring, and it opens your heart.

In your moments of clarity, you realize that our most intractable global challenges are rooted in the simplest of indecencies: the failure to see humanity in each other.

You’re not sure how you’re going to make a difference, but you know it starts with your heart. So you choose love.

At your best, you find courage.

You know, unmistakably, that our current moment requires guts. You know that ideologies are easy but pragmatic solutions are tough. You know that power has a vested interest in selling oversimplified narratives for expedient political purposes, and that year after year this sell-job has had a cumulatively pernicious effect.

Still, you wake up each day with a sense of possibility. Cynicism is always next to you, begging you to listen, but its voice gets fainter until you just don’t listen to it anymore. The beauty around you drowns it out. It gives you courage.

You know that the courage required on the road ahead will take many forms. Sometimes standing up. Sometimes standing aside. Sometimes fighting. Sometimes forgiving. Sometimes holding on. Sometimes letting go. Always listening.

You also know that the road ahead will require vulnerability: showing up when you want to hide; admitting weakness when you want to be strong; or saying “I don’t know” when everyone is looking for an answer. Your vulnerabilities are never your problem; your relationship to them is. When you find the courage to own them with confidence, you find power.

At your best, you see humor.

You will feel joy and sadness, hope and resignation, confidence and doubt, acceptance and rejection, ease and adversity, and comfort and grief. With luck you’ll feel more of the good stuff than the bad. But being human you’ll feel all of it. The irony of life is that the more attached you are to only feeling positive emotions, the more you’ll worry and the less you’ll enjoy. To live life is to feel grief. To try to avoid it is to invite more of it.

So dream big dreams, make big plans, open your mind, open your heart, and pursue with courageous conviction. That’s what a great life is made of. And lighten up along the way. Life will pinch you, punch you, and kick you in the teeth. Find the humor in it. Roll with it. Nobody is getting out alive or without scars.

At your best, you inspire.

Inspiration doesn’t come through fancy words or big ideas. Inspiration comes through your actions, every day. Amidst fear, selfishness, and hate, people see you choosing love. Up against difficult odds, people see you finding courage. Feeling the heaviness of life, people see you smiling and laughing.

You inspire because you shine a light, allowing others to do the same.

This is true leadership. The most important work in the world.

The post Who Are You At Your Best? appeared first on The Sundheim Group.

February 1, 2021

Building Team Alignment: It’s An Everyday Job

Originally published January 27, 2021 on Forbes

Good leaders know that alignment is critical in building successful teams. Unfortunately, many of them don’t do it often enough. Frequently leaders adopt a one-and-done, event-based mentality, for example, aligning at yearly or quarterly strategy meetings. While alignment should certainly happen at regular strategy meetings, it should also happen at nearly every moment in between them.

Every interaction is an opportunity to see gaps or problems. A little disagreement here or a lack of understanding there are signals. Sometimes the signal is nothing and it solves itself. Sometimes it grows and derails projects and careers. A leader’s job is to be able to differentiate between the two and know when and where to step in to realign things.

Here are a few suggestions for how to approach regular team alignment.

Make alignment a priority

Alignment is hard work and as a result, leaders often deprioritize it. The rationale is that they can deliver a product or service without it so why go to all the trouble. On one hand they might be right: They might be able to jam through a given initiative without true alignment. But on the other hand, it’s shortsighted and can have serious costs. Long-term success requires leaders to think beyond delivering specific initiatives and focus on building sustainable business practices. Fostering alignment is an essential element of doing that.

Use simple structures

A simple yet powerful tool to maintain alignment is the structured meeting. At regular intervals (weekly, semi-monthly etc.) use something like the following five questions to guide your one-on-one and/or team meetings: (1) What were our successes? (2) What were our challenges? (3) What caused our results (4) What is our plan moving forward? (5) Where do we need support? These questions (or something similar) become a forcing mechanism to unearth challenges early on. Without simple structures like these, meetings will often devolve into report outs that don’t surface possible areas of misalignment.

Really listen. (Hear both what is and what isn’t said)

Sometimes people will acknowledge when they’re on a different page. Oftentimes they won’t and it takes reading between the lines. For example, their words might say things are OK, but their body language says there’s a problem. Or there may be a decrease in the reliability, quality or frequency of their communication. Or someone mentions backchannel conversations or frustrations that haven’t come out in the open. This kind of stuff will kill a team’s effectiveness and put goals in jeopardy. Listen for it and take it seriously.

Don’t avoid conflict

Trying to get aligned on something invariably involves conflict. Don’t avoid it. It can be tempting to hope it takes care of itself, but that seldom works. Usually, avoiding conflict just strengthens frustration and animosity creating strategic and execution risk, not to mention career risk. Where conflict management skills are lacking, get support and improve them; it’s a good investment of time.

Recognize that not everyone has to agree in order to align

A team where everyone agrees usually has critical blind spots, so that should never be a goal. Effective teams will always have disagreements. Alignment is finding a way to move forward despite disagreements. It may entail compromises or merely agreeing to support a path forward that isn’t a first choice. It only works through open dialogue and trust. This is why constantly listening for and addressing potential conflicts is so important. It allows disagreements to surface while still creating an opening for alignment.

Of all the things a leader must do, building alignment is one of the toughest: It requires considerable analytical and emotional awareness; it takes a tremendous amount of time and energy; and there’s no promise of success even if everything is done right.

But the payoffs of getting good at building alignment are huge: It deepens trust and relationships; it clarifies possibilities and problems; and it accelerates planning and execution.

Arguably, in our rapidly changing world, no leadership skill is more important.

The post Building Team Alignment: It’s An Everyday Job appeared first on The Sundheim Group.

November 22, 2020

Should you really build leaders at every level of your organization?

Originally published November 17, 2020 on Forbes

[Spoiler alert: Yes!! If you don’t you’re dead in this economy.]

I debated this question with the COO of medium-sized technology firm recently.

His take was that while leadership at every level sounded nice, in reality it was impractical and unwise. His argument surrounded five reasons:

Some people don’t have the skills to lead

Some people don’t want to lead

If everyone thinks they’re a leader too many people are directing things and not enough people are doing things

Having too many leaders creates confusion

Developing leaders is a resource-intensive task and, given reasons 1-4, not a good investment except for high potentials

I understand his logic, but it has a flaw; it defines leadership too narrowly.

Too often we cleave to an antiquated notion of leadership as visionary direction-setting and fearlessly leading the troops into future with a few big strategic decisions. Yes, that is one type of leadership, but it’s grounded in a set of assumptions about how the world works (military-industrial and command-and-control) that are rapidly changing. When the world moved more slowly a few big decisions at the top could legitimately set a trajectory for years to come. In this day and age, that’s a recipe for obsolescence.

Here’s a broader and more useful definition of leadership nowadays: critical and collaborative thinking and action given what you see in front you.

You want your C-Suite doing this, but you also want the lowest-level person in your organization doing it too. The scope and impact of their decisions will obviously differ, but the general mindset remains the same—we need everyone motivated to solve problems. Building critical and collaborative thinkers and doers at one level strengthens their ability to do the same at the next level and the next level.

Here’s a practical idea. Define what leadership looks like, as a mindset and set of behaviors, at every level of your organization. Create a curriculum that builds on itself as employees grow. First it’s about leading the self, then leading others, then leading the org. At each level touch upon the other levels so people see the bigger picture of leadership in the org. Have people understand what’s going to be required of them before they get there. The smart ones will start picking it up themselves.

Leading the self – This is all about personal and emotional awareness. It’s about values clarification and identification. It’s about understanding tensions and tradeoffs and developing a point of view on what matters most to an organization and the individual person. As an employee does this work, they get a better understanding of where there is and isn’t alignment, teeing up important decisions. Self and organizational awareness will evolve over a career. Stressing the importance of this early sets the stage for future leadership development.

Leading others – As employees move into increasingly larger managerial roles, they must remove themselves from more and more of the daily work, trusting that to the members of their teams. Doing this can be difficult for many who have been used to having their hands directly on the dials of the work to be completed. The previous self-awareness work becomes a critical foundation to making this leap and bringing out the best in others to get the jobs done effectively.

Leading the organization – This is the senior leadership of an organization. It requires setting vision and direction and making difficult tradeoff calls at the enterprise, industry, and often global level; it’s what we traditionally think of as “leadership.” Anyone who excels here does so because of the leadership development work they did at the lowest levels of an organization on up. They succeed because they and others saw themselves as a leader long before they were bestowed with the formal title.

Don’t wait to teach leadership until people are “ready” and somehow “worthy of investment.” If you do, you’ll never end up with who you need when you need them. Start with small awareness building early. Invest smartly in leadership building and a leadership culture all along the way. The most capable will rise to top for senior leadership roles. But more importantly everyone will know what leadership looks like at all levels, distributing the heavy lifting of leadership throughout the organization.

The post Should you really build leaders at every level of your organization? appeared first on The Sundheim Group.

November 18, 2020

We Need Leaders Who Have The Courage To Love

Originally published November 13, 2020 on Forbes

A global pandemic is raging. Racial tensions are smoldering. Economic inequality is increasing. An environmental crisis is looming. And a partisan chasm in the US is widening. The challenges we’re facing didn’t just show up this year or even the over the last four years. They’ve been simmering for half a century as we’ve grappled with the end of the post-war economic boom and fights over civil rights and equality. Faced with increasing tensions many of our leaders have chosen to respond with win-lose framings that at their worst have incited violence and at their best have lacked moral imagination. They’ve pitted capital against labor, profits against the environment, people against the government, and citizens against each other. Our long-simmering challenges have now reached a boiling point with a growing sense that things must change, or something will blow.

While we don’t yet know the best paths forward to address these challenges, I do know where the paths start: with love.

All lasting change, whether in a person, relationship, family, organization, town, city, or nation, starts with love. Love accepts people where they are (an ironic prerequisite of change). It listens without judgment. It sees without stereotyping. And it opens the door for dialogue, imagination, and new possibilities.

Yet, despite the central importance of love, our business and political leaders often struggle to embody it. One reason is the pervasive be-tough, show-no-emotion, dominate-or-be-dominated, zero-sum mindset that has long been valued and rewarded in our culture. To embody anything but this mindset is regarded as weak. This false assumption has brainwashed too many of our leaders for too long to the detriment of our institutions and society. Power, competitiveness, and the will to win are inevitable and valuable elements of modern life. But when they exist in the absence of love, they become destructive.

In his 1967 speech Where Do We Go From Here? Martin Luther King Jr articulated this requisite coexistent relationship between power and love: “What is needed is a realization that power without love is reckless and abusive, and that love without power is sentimental and anemic. Power at its best is love implementing the demands of justice, and justice at its best is love correcting everything that stands against love.”

We need more full-throated endorsements of love from our leaders. While these days we hear a lot about empathy as a critical leadership characteristic, we hear little about love. Is empathy love? It is not. Empathy is a foundational and necessary precursor to love, but it is not love per se. Where empathy seeks to understand, love seeks to do something. Love is empathy in action. Love moves past awareness through vulnerability to take a stand and lay something on the line.

James Baldwin captures this laying-it-on-the-line type of love in his 1962 essay on race, Letters from a Region in My Mind: “Love takes off the masks that we fear we cannot live without and know we cannot live within. I use the word ‘love’ here not merely in the personal sense but as a state of being, or a state of grace—not in the infantile American sense of being made happy but in the tough and universal sense of quest and daring and growth.”

This type of tough, unflinching, open, and daring love is needed now more than ever because it’s the only thing that can break open the entrenched-ness and stuck-ness we’re all feeling. This type of love is the only thing that will allow us to take off our masks and see each other. This type of love is the fuel that fires our moral imaginations to find new and powerful paths forward together.

In an era of scientific, technical, and industrial progress our moral imaginations have atrophied. Efficiency, a fine goal, has problematically become the only goal. Short-term value has supplanted long-term health. Specialization and individualization have weakened connection and community.

Two hundred years ago poet Thomas Love Peacock wrote an essay on how poetry had become irrelevant in a world where “mathematicians, astronomers, chemists, moralists, metaphysicians, historians, politicians, and political economists” had come to occupy “the upper air of intelligence.”

The following year poet Percy Bysshe Shelley penned a rebuke, arguing that Peacock failed to grasp the vital role a poet plays as a “legislator of the world” who works to “produce the moral improvement of man.” “The great secret of morals,” Shelley contended, “is love.” Through love the poet puts himself “in the place of others;” identifies with “the beautiful which exists in thought, action, or person;” and makes the “pains and pleasures of his species…his own.” Through love the poet “imagines intensely and comprehensively” and in so doing “awakens and enlarges the mind” with “a thousand unapprehended combinations of thought.”

We need poets to counterbalance power brokers right now. We need those thousands of unapprehended combinations of thought to revitalize a moral imagination that has suffocated in our greed-is-good modern world. We need storytellers and sensemakers to remind us that we’re all in this together, that separateness is an illusion, and that there is no winning when others get left behind.

Love is not weak. Love is not soft. It is, as Mahatma Gandhi said, “the prerogative of the brave.”

At this pregnant moment in our nation and world we need brave leaders, which is to say we need leaders who have the conviction and courage to love.

The post We Need Leaders Who Have The Courage To Love appeared first on The Sundheim Group.

October 21, 2020

10 Goals Effective CEOs Deliver To Drive Long-Term Value

Originally published October 16, 2020 on Forbes

The CEO job is tough. And it’s getting tougher as modern business gets more complex. The role of the CEO is different from any other in the organization. The CEO must see the entire context within which the organization is operating, understand myriad forces at play, set a broad vision, and be the final voice on difficult decisions.

In working with CEOs over the past twenty years, I’ve developed a list of ten goals that drive long-term value. The first six have to do with people. The last four are what great people deliver working together.

The value of this list isn’t its novelty. Rather it’s in capturing the breadth and complexity of the CEO role in a short, digestible, and demystified form. The list should provoke questions: How important is this goal? Why is it important? Are we delivering it? And how are we measuring success? It should provide a roadmap for assessment, dialogue, and prioritization of efforts.

Each goal is stated as an outcome rather than an action so as not to be prescriptive: There are many intelligent ways to approach these goals depending on context. The work of a CEO and executive team is to figure out the best path forward given their specific industry and situation. Under each goal is a brief description and key questions for consideration.

Ten goals that effective CEOs and their senior teams deliver:

1. Strong RELATIONSHIPS with all stakeholders

Customers, employees, suppliers, communities, board members, and shareholders are all critical to an organization’s success. When things turn bad for an organization it’s usually because one or more of these stakeholder groups have been neglected for too long. — Key questions for consideration: How regularly and robustly are we engaging stakeholder groups? How open is the dialogue? How clear are we about what’s on their minds?

2. Talented, diverse, and motivated PEOPLE

The right people in the right roles are pivotal to creating long-term value. It takes significant investment to build a winning talent engine from attraction and recruitment through development and retention. Efforts invested here become a competitive advantage that’s tough to replicate. — Key questions for consideration: Where is our talent engine strong and where is it weak? Have we raised talent to the right strategic level? If we haven’t, what will it take to do so?

3. Distributed and adaptive LEADERSHIP

No organization today can be successful in the long-term without distributed and adaptive leadership; business is too complicated, and changes come too fast. If leaders throughout the organization don’t have the judgment, skills, or authority to make quick calls it creates problematic bottlenecks. — Key questions for consideration: Where are we not pushing down leadership far enough into the organization? What’s holding us back?

4. Continuous LEARNING at the core of everything

To be in business today is to be somewhat paranoid. As technology upends industry after industry with increasing speed, an organization’s ability to learn and adapt quickly is essential to staying relevant. Moreover, continual learning and growth helps retain talent. — Key questions for consideration: How are we building learning into everything we do? How serious are senior executives about their own learning and development?

5. Clear VALUES alive in the organization

Organizational theorist Chris Argyris made the case that there are two sets of values in every organization: espoused values and values-in-use. When the two sets are far apart, values are empty words on a page. When they’re closer together, values provide meaningful power and focus. — Key questions for consideration: What are our espoused values? Are they the right values? Are we living them? If no, why not?

6. Collaborative, trust-based, and risk-tolerant CULTURE

The most significant driver of culture in an organization is senior leader behavior. Behavioral role-modeling cascades through an organization faster than any corporate initiative or change plan. — Key questions for consideration: How are senior leaders behaving? Are they role-modeling high trust, collaborative, and smart risk-taking behaviors? If not, what’s being role-modeled? And what’s the impact?

7. Shared and compelling VISION

A vision is a descriptive picture of the future. It’s effective when it provides broad clarity and inspiration regarding an organization’s direction. It fails when it’s not shared, compelling, or credible. — Key questions for consideration: How clear, compelling, credible and shared is our vision? Where and how do we regularly bring our vision to life?

8. Distinct and well-understood STRATEGY

In its simplest form, strategy is the allocation of limited resources in pursuit of a vision. It should play to strengths and create an advantage. Furthermore, it should provide guardrails and direction for making tradeoff decisions. — Key questions for consideration: Is our strategy clearly articulated and well understood? Does it provide appropriate direction for what we will and won’t do in pursuit of our vision?

9. Disciplined and dynamic EXECUTION

Strategy’s clean and elegant logic gets dirty in the real world. Successful execution requires disciplined processes that dynamically shift as needed. The faster business get, the more dynamic execution needs to become to keep pace. — Key questions for consideration: Do we have the right balance of discipline and dynamism in our execution? If not, where do we struggle?

10. Strong and sustainable PERFORMANCE

Organizations manage what they measure. Accordingly, a CEO must ensure the right things are being measured. Stakeholders should have a hand in helping to define appropriate metrics. — Key questions for consideration: What metrics matter most to our long-term health? How do we effectively measure them?

These ten goals are aspirational. No one nails all of them all the time. It’s best to use them to honestly self-assess where things are working and where they’re not. Where things aren’t working, the goals should tee-up productive exploration and discussion.

The list is also a reminder of just how challenging the CEO role is in our modern world. Where a CEO used to hold a vast majority of the knowledge needed to drive success in their industry, they now hold a fraction of that knowledge. Where they used to direct organizational activities, now they must facilitate them. Where they used to provide answers, now they must intelligently create the environment in which new answers can be collaboratively born and collectively pursued.

October 12, 2020

Capitalism Isn’t Broken: The Economic Thinking Behind It Is

Originally published October 7, 2020 on Forbes

Over the past forty years, business has worshipped at the altar of economic efficiency. Beneath countless management fads and trends have been three simple goals: cut costs, grow profits, and increase share price.

On the surface, this calculated agenda looks inarguably smart, providing the seemingly perfect engine for economic expansion. But just below the surface lies a dark side of using these narrow goals to make complex and messy decisions: when decoupled from a moral foundation, they tear at our social fabric.

Free market economists have helped lead this decoupling process. For years they’ve argued the best way to organize a prosperous and healthy society is to let individuals maximize their own financial self-interests through private markets. Collective selfishness, they contend, leads an “invisible hand” to guide society down the right path as competition dynamically optimizes for the best outcomes.

There are two problems with this argument. First, the US economy isn’t as competitive or free as some would have us believe, with much of the inefficiency advantage going to corporate interests and never really “trickling down” to the rest of society. Second, aggregated short-term private selfishness doesn’t actually produce long-term public good. In theory, that’s why we have government to intervene. Herein lies the challenge.

Over the past several decades government has neglected to play a proper balancing role in capitalist markets, instead jumping into bed with free market economists. Politicians have largely avoided making difficult decisions on tough topics such as climate change, inequality, stagnant wages, and common-sense financial regulation. In essence, they’ve cut a Faustian bargain by letting the fiction of an invisible hand pick-pocket our long-term future in order to drive short-term growth. To make matters worse, the spoils from this unholy bargain are accruing to an increasingly small percentage of those at the top. What’s blindingly obvious to anyone paying attention is that we need to rebuild our social contract to better serve our whole country and not just a powerful elite.

Of course, none of this is new. Articles and books on these topics have been written with increasing frequency since the 2008 financial meltdown. Even economist Alan Greenspan, former Chair of the Federal Reserve and one of the architects of thirty years of free market policies, admitted in 2008 that he was “in a state of shocked disbelief,” acknowledging that he had put too much faith in the self-correcting power of self-interest and free markets. Yet still, according to a sobering Wall Street Journal report, not a whole lot has changed since the 2008 crisis.

This begs the question: If the 2008 financial crisis, which would have brought down our global banking system were it not for a taxpayer-funded bailout (ironically, a move that reeks of just the socialism that free-marketeers like to rail against), wasn’t enough of a wakeup call to change our economic zeitgeist, what is?

It’s tough to say. The idea of stakeholder capitalism is gaining some steam and producing positive stories, but it still lives inside a system geared towards shareholder primacy. Many companies are being called out for giving lip service to stakeholder capitalism while not genuinely trying to advance the ball. Nevertheless, momentum continues to build: This September, the World Economic Forum, in conjunction with the world’s largest accounting firms published a comprehensive framework for measuring stakeholder capitalism. It’s a useful document, but it lacks the teeth for producing real change.

So, where will real change come from? Ultimately, one place: civic education and participation.

We as citizens must demand, with our voices and votes, the sort of policy and economic changes we want to see. Thomas Jefferson’s words from 1820 are just as true in 2020. “I know no safe depository of the ultimate powers of the society but the people themselves; and if we think them not enlightened enough to exercise their control with a wholesome discretion, the remedy is not to take it from them, but to inform their discretion by education.”

One useful topic of education for all of us is basic economics. Economics lies beneath everything. As noted British economist John Maynard Keynes observed, “The ideas of economists and political philosophers, both when they are right and when they are wrong, are more powerful than is commonly understood. Indeed, the world is ruled by little else.”

Unfortunately, many people think that economics is too complicated to understand. “Economists have been fantastically successful in making people believe that [economics] is…more difficult than it really is,” says Cambridge economist Ha-Joon Chang. “95% of economics is common sense. It’s just made to look difficult through the use of jargon and mathematics.”

That perceived difficulty is a significant barrier to a well-functioning democracy. Since the early 1970s, economic reasoning has come to dominate political and judicial decision-making and thus our entire society. It’s easy to understand how this happened: Economics provides rational, unemotional cost-benefit analyses for complex and thorny issues from business and investing, to crime and pollution. Even adultery has been examined through an objective economic lens.

This mathematicised view is so seductive in its reductionist clarity of the world and so ingrained in our national psyche that it’s tough to even notice it, let alone question where it’s overstepped desirable boundaries and crowded out other important ideas like character, morality, well-being, equality, and the environment. Three recent books are particularly useful in shedding light on the economic mental models we all live within: Doughnut Economics, Transaction Man, and The Economists’ Hour. Together they explain our journey to the present moment and how narrow economic goals and thinking are at the root of many challenges we now face.

On the flip side, an equally important topic of education is for economists to understand the humanities. Northwestern economist Morton Schapiro wrote a 2017 book with literary critic Gary Saul Morson about the problems created by using math-based models to solve human-centered challenges. “We’re not comfortable with things that we can’t put into an equation,” Schapiro shared, “and I think we lose a lot because of that.” Humans, it turns out, in one of those I-can’t-believe-I-have-to-actually-point-this-out insights, need the humanities.

We’re at a powerful moment right now. A global pandemic is exacting a costly and unequal toll on our economy and the human beings who live inside it. Yet, amidst the tragedy there is a silver lining: It is bringing into clear focus fractures in our society that need to be fixed. It’s waking us up to the fact that economics is not a set of “value-free” scientific laws, but rather value-laden judgment calls that have a real impact.

In the months and years ahead, we have to open our eyes to what’s happening around us. We have to speak up for the economic goals we feel are important, not just accept the ones we’re being fed. And we have to elect leaders who will fight for a more sustainable form of capitalism.

Our country won’t survive if we don’t create legitimate opportunities for everyone to thrive.

August 9, 2020

CEOs Have A Responsibility To Help Lead Society

Originally published August 4, 2020 on Forbes

by Doug Sundheim

In his New York Times opinion piece last month, Harvard economist Greg Mankiw, argued that C.E.Os are qualified to make profits, not lead society, and that we should not expect the latter of them. His arguments are too simple, have significant holes, and read as if they were written in 1970 when economist Milton Friedman famously argued the same point.

Friedman’s ideas came to be known as shareholder value theory. Its singular management goal was maximizing returns to shareholders. Conceptualized at a time of increasing global competition and slowing economic growth, the idea caught on fire. By the 1980s, shareholder value theory was at the heart of Ronald Reagan’s and Margaret Thatcher’s supply side economic policies, which spread throughout the world in the ensuing decades. By keeping business leaders solely focused on returns to shareholders, the logic went, benefits were supposed to trickle down to create prosperity for all. It sounded good in theory, but it’s been problematic in practice, leading iconic CEO Jack Welch, a onetime staunch supporter of shareholder value theory in the 1980s and 1990s, to eventually acknowledge it as “the dumbest idea in the world.”

Most troubling about Mankiw’s article is that at time when ~70% of the largest entities on earth are corporations, not nations, he doesn’t acknowledge the need for the executives running these corporations to help lead society.

Following are three of his arguments which fail to grasp the world in which CEOs are now leading, and my thoughts in response.

Mankiw’s argument: Corporate management’s mandate should be the narrow self-interest of achieving greater profits for shareholders, not broad social welfare

To illustrate his point, Mankiw presents a scenario in which a company producing gasoline cars in Michigan considers closing it and opening one producing electric cars further south. He asks the reader to imagine they are an executive deciding whether to approve the plan. In his view, if you’re concerned solely with profits for shareholders it will help “focus the mind.” However, he continues, if you’re concerned with a broader set of stakeholders, including customers, employees, suppliers, communities, and shareholders, it opens up a range of “dizzying” questions that will require CEOs to be broad social planners rather than narrow profit maximizers. He goes on to list several of the additional hypothetical questions that the broad social planners would have to consider:

How much will the closure of the old plant hurt its workers and their community?

How do you weigh those losses against the gains to the would-be workers at the new plant?

Given the nation’s history of systemic racism, should you consider the racial makeup of the two groups of workers, in an effort to reduce economic inequality?

Does it matter whether the new plant is in South Carolina, providing jobs for American workers, or in Mexico, providing jobs for Mexican workers?

How should you weigh the benefit of electric cars in mitigating climate change? Should you consider the global impact of climate change or only the impact on the United States?

How should you balance these concerns against the interests of shareholders, who entrusted you to invest their savings?

Every corporate executive I’ve worked with over the past twenty years would have included some version of the above questions in their considerations. To exclude them is ridiculous. It’s not broad social planning, it’s basic business planning in the 21st century: Business has grown more interconnected and complex. Who, for example, seeing the potential devastation of a community they are leaving, would not spend considerable time, energy, and effort trying to find a cost-effective and innovative solution to stay put. Good CEOs are always weighing social costs that don’t immediately show up on the bottom line. They will always have profit in mind, but they will also be considering the needs of a variety of stakeholders. In this day and age if these questions seem too “dizzying” for a CEO to consider, the answer is not to lower the bar on expected qualifications, but rather to raise it and find or train CEOs who can balance the demands of multiple stakeholders.

Mankiw’s argument: It’s unlikely that corporate executives, with their business training and limited experience, have the skills to be broadly competent social planners rather than narrowly focused profit maximizers

Related to points above, this distinction doesn’t accurately reflect the world in which CEOs now find themselves. Corporate executives can and should play a variety of leadership roles that move beyond narrow profit maximization. This is social responsibility, not broad social planning. The soul has been ripped out of business over the past 50 years as we’ve come to view every decision through the myopic lens of short-term earnings. We’re starting to find our way back to a more balanced view and we need CEO’s leadership in the process.

How should CEOs approach leadership on important issues where they can make a unique and lasting impact? Former Unilever CEO, Paul Polman talks about creating collective courage. He rightly points out that it’s tough for one industry player to impact an issue like reducing greenhouse gases because of the loss of competitiveness. But in his experience, if at least 20% of industry players can come together to move on an issue, they can reach a critical mass and begin tipping the scales. In this way, corporations, governmental agencies, and NGO’s can partner to lead society. Where does this sort of collective leadership live in Mankiw’s simplified model? Unfortunately, nowhere.

Mankiw’s argument: The world needs people to look out for the broad well-being of society. But those people are not corporate executives. They are elected leaders who are competent and trustworthy

This is perhaps the most troubling of Mankiw’s arguments. He claims that our elected leaders, not corporate executives should be looking out for the well-being of society. On the surface, it’s a fair argument: But he fails to acknowledge just how much influence our corporate executives have over our elected officials and the legislative process. Forty years ago, business, labor, and public interest group lobbying was on relatively equal footing. Today, large corporations and their associations outspend labor and public interest groups 34 to 1 on lobbying efforts, totaling upwards of $2.6 billion in 2014. To put that number in perspective, in 2014 the US spent $2 billion on all congressional (House and Senate) operations. That means that business lobbyists had more operational firepower than the entire elected legislative branch of the US government. That’s not a thumb on the scale, that’s an elephant on the scale crowding out everyone else.

In sum, CEOs cannot simultaneously be unqualified to lead society and yet be exerting such immense influence behind the scenes. If they’re qualified, they should step up and help lead on the thorny economic issues of the day. If they’re not qualified, they should take significant weight off the scale. They can’t have it both ways. With great power, comes great social responsibility. We must demand the latter of our corporations, their boards, and their CEOs.

August 5, 2020

How To Build Momentum When You Feel Stuck

Originally published July 31, 2020 on Forbes

by Doug Sundheim

Many of us feel stuck these days. The Covid-19 pandemic has upended our personal and professional lives. Certainties that we used to take for granted are now uncertain. Routines that gave us comfort are gone. Many plans and projects that we had lined up have been scrapped or derailed. And while we were troopers in March and April when the situation felt more temporary, now in the late summer we’re feeling exhausted by the daily grind and anxious about what appears to be an extended unclear future.

If you’re feeling stalled, what can you do to begin building forward momentum again?

Here are 4 suggestions:

Embrace gratitude

Being grateful is a counterintuitive but rewarding way to change your perspective. Try this exercise: Take 15 minutes every day for the next week and write down 3-4 different things you’re grateful for. By the end of the week you’ll have a list of 20-30 things that you truly appreciate about your life.

Why is this exercise helpful? Because it interrupts our negativity bias. Simply put, for survival reasons our minds tend to dwell on negative events more than positive ones. Negative thinking in short spurts can keep us sharp and aware. However, these days we’re swimming in too much negativity because it sells. The press, social media, TV, and other online offerings pull us into a vortex of negative thinking and emotions. The gratitude exercise is a simple way to actively interrupt our unwitting addiction to this bias.

Schedule time in your calendar to do this exercise regularly. Reminding yourself often is important.

Let yourself be stuck for a while

Being stuck can be a gift if we’re willing to live with it. Ironically, if we try to get ourselves unstuck too quickly, we can make our problems worse. By acting too fast, we miss important lessons regarding our habitual mindsets and behaviors, some of which themselves may be contributing to our challenges. “The mind is its own place,” English poet John Milton wrote, “and in itself, can make a Heaven of Hell, a Hell of Heaven.” When we worry and catastrophize too much, it undermines our ability to think creatively and expansively about solutions to our problems. If we don’t take the time to understand how our internal viewpoints color our world, we lose personal power and the opportunity to invent a better life for ourselves.

This single insight is at the heart of many world religions and spiritual practices. Buddhism, for example, is founded on the 4 Noble Truths. Summarized simply they are: (1) Life is not ideal, (2) Suffering comes from wanting life to be ideal, (3) Suffering decreases as we loosen our attachment to having everything be ideal, and (4) We loosen our attachment to having everything be ideal by slowing realizing just how crazy this attachment is making us. One of life’s great ironies is that we are at our most powerful to change unwanted circumstances when we accept—and are truly OK with—the fact that our circumstances may not change. There are many books written on this topic. Pema Chodron’s The Places That Scare You is a good one.

Try something new

Certain opportunities have now vanished. New opportunities are emerging. The longer we stare longingly at the vanished opportunities, the less we’re able to see the new ones that are coming into view. The internet is now filled with successful transformations to new businesses, or what have become known as “pivots”. For inspiration and ideas it’s worth poking around to see how others are pivoting to rewarding, viable work.

A great example is Sangria and Secrets with Drag Queens. Before the pandemic the business was an engaging in-person Airbnb Experience. When the pandemic hit the owners were devastated. Money started running low. The team decided to try something online, figuring they could earn a little money. The idea exploded, bringing in $150K in the first month. There are also inspiring stories of people finding new jobs they didn’t realize they could land.

The learning here is to just start moving in a new direction. Don’t try to figure everything out in advance; there are simply too many unknowns these days. Movement leads to more movement. Insights produce more insights. You can course-correct as you go.

Help others get unstuck

Staring at your own challenges gets tedious quickly. Moreover, when you’re so close to them it can be tough to see new paths forward. Often the best thing to do is find a way to take your mind off your problems for a while.

Reaching out to friends and colleagues to be a sounding board for their challenges is a productive way to do that. As long as you’re not doling out unsolicited advice, most people will welcome the connection. Plus it can be very helpful for a number of reasons. First, it allows the other person to get out of their own head (the same thing you need). Second, you’re able to see angles on someone’s problems that they often can’t see. Third, it helps the other person accelerate their own problem solving. Fourth, it gets your mind moving in different and often productive directions as well. It a great win-win: You can’t help another without also helping yourself.

Above all else, when you feel stuck remember this: You don’t have to solve all your challenges immediately. Small steps forward will create a positive sense of momentum. With momentum comes energy, hope, and the promise of a better, brighter future.

All you have to do is get started.

July 5, 2020

Your Communication Probably Stinks: Plan Accordingly

Originally published June 30, 2020 on Forbes

by Doug Sundheim

“The single biggest problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken place” —George Bernard Shaw

When it comes to pursuing new ideas, entering new markets, or trying to make any big changes that involve other people, I always tell clients to start with the assumption that their communication is going to break down. This advice isn’t based on my observations of them, their specific organization, or the specific situation they’re facing. Rather, it’s based on my observations of hundreds of leaders just like them, all their organizations, and all the situations they’ve faced. Whenever two or more people are involved in anything, there’s a good chance that communication will break down at some point.

I see it in my own life and business. While it’s my job to help leaders and teams get better at communicating — and I’m hyper aware of pitfalls that can lead to poor communication — I still have communication breakdowns. I might get busy and not let other team members know what I’m doing. Or I might spend so much time thinking about a topic that I forget that others aren’t on the same page as I am. Or I might not share a piece of information because it doesn’t occur to me that it would be helpful for others to know it. Given the pace of business today, it’s easy for these things to happen, even when I know better.

Recognizing how easily breakdowns can occur, I have weekly check-in meetings with my team on key projects. When an issue rears its head, we’ll discuss why it happened, how to address it, and how to avoid it in the future. However, although we get better, we never completely eliminate communication breakdowns. Invariably, a different issue under different circumstances arises several months later, and we’ll go through the process again.

I’ve come to see communication breakdowns as a simple fact of human interaction and organizational life, especially when you’re up to something big. There are always a lot of moving parts to manage. If you expect breakdowns, catch them, and address them, you can lessen their frequency, intensity, and negative impact. Also, if you deepen your appreciation for why they happen, you can get better at predicting them in advance.

The Communication Blind Spot

Communication within organizations breaks down for many complex reasons, ranging from power dynamics to low levels of trust to hidden agendas. However, in my experience, the most common reason communication breaks down is much simpler than these. It happens because people fail to realize that they have information that should be communicated in a more focused, thoughtful, and frequent way.

I call this the communication blind spot. It frequently unfolds something like this. People get together, talk about something over a number of months, and come to a set of decisions. Then they share their decisions with a few people in the organization in an ad hoc fashion. They might even send a document around outlining the decision. Three months later, because they’ve been talking about the issue so much and they remember sending a document around, they’re under the illusion that everyone understands and appreciates the decision the same way that they do. They’re blinded to the fact that others, who weren’t in the original planning meetings and have never been focused on the ideas that the planners discussed, don’t have nearly the same appreciation for those ideas. Then one of the original planners brings up the idea in a meeting, assuming that everyone is on the same page as he is. Unfortunately, 75 percent of the room has no idea what he’s talking about. The person bringing it up can’t believe it. He was sure that the decision and rationale were shared very clearly with the organization months ago. But he was wrong.

The communication blind spot happens because once something becomes really clear to us, we have a tendency to think that it’s clear to everyone else, too. As a result, we don’t feel that the topic needs a lot of detailed communication. That’s when problems begin. People have different understandings of the issue. They draw different conclusions, and they begin operating from different sets of assumptions.

Here are a few practical suggestions for avoiding the communication blind spot:

Always start from the assumption that your communication is terrible. It may be an overstatement, but it will serve you well by putting you in a productive mindset.

Capture key discussions and decisions in brief “recap” emails and circulate to relevant parties. Make them short. I recommend 3 parts to each topic discussed: Key discussion points, decisions made, and next steps. That way, in 3 months, when no one has any recollection of the meeting, you can remember, where, when, and why a decision was made. And you can use these notes to keep a group focused and hold them accountable.

Check in with people regularly. Ask for feedback on “in flight” projects or programs. If you get a blank stare you’ll realize the message didn’t get through. Go back to the drawing board and re-communicate. Repeat often.

June 16, 2020

How To Have Productive Dialogues On Tough Topics

Originally published June 11, 2020 on Forbes

by Doug Sundheim

Dialogue is the art of thinking and talking together at critical moments to deepen awareness and understanding. The current protests surrounding racial inequality, and global economic dynamics spotlighting income inequality and climate change make clear an inescapable fact: We need dialogue now more than ever.

However, dialogue can be difficult. It requires time, an open mind, a willingness to change, courage to speak up, and mutual respect—things that feel in short supply these days. That doesn’t mean we should shy away from dialogue. Rather we should be thoughtful in how we approach it. Following are a few suggestions.

Practice 5 key skills

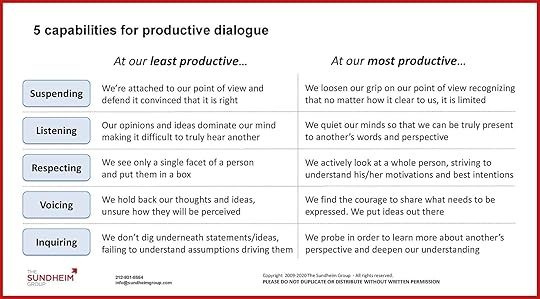

At the heart of good dialogue is the ability to put your perspective aside to truly hear others. This capability is called suspending. It, along with four additional capabilities — listening, respecting, voicing, and inquiring — make up what I refer to as the five fundamental moves of dialogue. Each can be viewed on a continuum from least productive to most productive. Below is a slide capturing these continua. (If the image is hard to read, identical text is below it.) Effective dialogue is the result of a group of people moving to the more productive side of the continuum on each dimension.

Suspending

At our least productive – We’re attached to our point of view and defend it convinced that it is right

At our most productive – We loosen our grip on our point of view recognizing that no matter how it clear to us, it is limited

Listening

At our least productive – Our opinions and ideas dominate our mind making it difficult to truly hear another

At our most productive – We quiet our minds so that we can be truly present to another’s words and perspective

Respecting

At our least productive – We see only a single facet of a person and put them in a box

At our most productive – We actively look at a whole person, striving to understand his/her motivations and best intentions

Voicing

At our least productive – We hold back our thoughts and ideas, unsure how they will be perceived

At our most productive – We find the courage to share what needs to be expressed. We put ideas out there

Inquiring

At our least productive – We don’t dig underneath statements/ideas, failing to understand assumptions driving them

At our most productive – We probe in order to learn more about another’s perspective and deepen our understanding

Be patient in creating a safe space for dialogue

The safer the space, the better the dialogue. However, safe spaces don’t materialize through edicts. A feeling of psychological safety gets stronger or weaker through social proof. Has someone opened up a sensitive topic and gotten positive reinforcement? Are leaders role modeling behavior and making themselves vulnerable? Sometimes it takes a few meetings with productive behaviors to begin to create a sense of safety. Don’t try to force dialogue around a difficult issue if people don’t feel safe. It will usually backfire and make open dialogue tougher in the future. Use the dialogue skills above to make your conversational space safer over time.

Pick the right situations for dialogue and then actively seek it out

Dialogue takes focus and energy. While a lot of situations could benefit from it, we cannot always engage in it. It’s best used in high-stakes and complex situations involving conflicting and contentious viewpoints. On the macro scale, racial inequality is one of these topics. I recommend seeking out dialogue groups for exploration. Many community, civic, and educational institutions around the world are holding sessions. As well, this site has useful resources on framing and starting dialogues around the topic of race.

On a micro scale, complex decisions or strained relationships among key people in an organization are good reasons for dialogue. Opening a dialogue between groups or factions can loosen entrenched perspectives and create room for new paths forward. Time invested now can have a significant positive benefit later.

Consider external facilitation for your toughest issues

If you’re trying to open a dialogue or get aligned around a particularly challenging set of issues in your organization, using an experienced external facilitator can be a good idea. An objective person offers a few important benefits. First, they’re not as close to the issues making it easier for them to stay objective. Second, their presence allows all group members to be players in the dialogue and not have to worry about refereeing tough interactions that often arise. Finally, they can help ensure quieter members get their voices heard and more vocal members don’t monopolize airtime.

In theory, it’s hard to argue against robust dialogue as an important leadership skill. In practice, however, for reasons listed above, dialogue is tough to do. The best advice is to start building the skills one meeting at a time. The long-term positive impact is worth it. Leaders who role model skillful dialogue create more leaders who do the same. In the tumultuous years ahead, this skill, embedded in a culture, both organizationally and societally, is essential.

Here is a useful resource on dialogue facilitation.