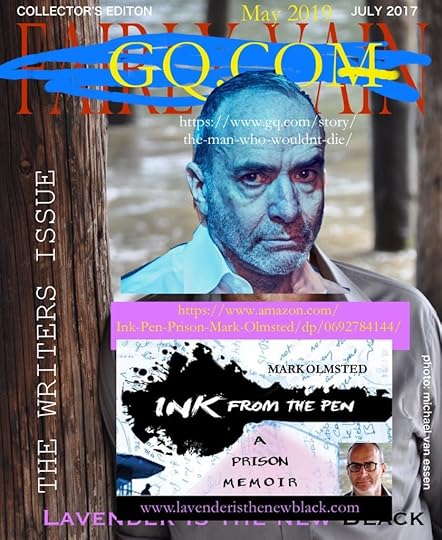

Mark Olmsted's Blog

May 23, 2019

GQ to the Rescue

At long last, the story about my story has made it to the big time.

https://www.gq.com/story/the-man-who-wouldnt-die

August 21, 2017

Arts and Understanding Promo II

Everyone gets 15 minutes of fame. But some of us want 20.

August 9, 2017

A & U Profile

August 4, 2017

Junkie in Jail

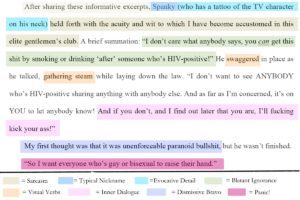

(This story in the New York Times leads me to post this excerpt from Ink from the Pen.)

There were only a few of us inside the holding tank, and after I gingerly stepped over someone sleeping in the dead center of the floor, I was grateful to find the last free corner. With a little luck, I thought, perhaps I could doze off, too. (The toilet paper Larry had given somehow felt like a security blanket.)

I had just drifted off when the moaning started. I tried to ignore it, but it went beyond some fitful soundtrack to a bad dream. A fellow I hadn’t even noticed before was on the floor of the tank, writhing in discomfort.

He started pleading to see a guard, claiming to have had a heart attack the week before, and in dire need of returning to the hospital. I surmised he was most probably suffering from heroin withdrawal, but that hardly made it less unpleasant. Dope sick is on par with food poisoning when it comes to feeling like you are about to die.

After what seemed like a solid hour, I started to press the “emergency” intercom. Finally, after twenty minutes or so, a deputy answered and asked what was wrong.

I resisted an overwhelming urge to mention how many times I’d rung the buzzer, and stuck to the point at hand.

“There’s a guy here who’s really sick. Seriously.”

There was a sigh, then silence. I felt the wary eyes of the other men in the cell on me, as if they were afraid my do-gooding would somehow get them all in trouble.

The intercom crackled back on.

“He’s seriously sick?”

No, I thought sarcastically, I’m just bored and felt like playing with the buzzer.

“Yes, I think he’s seriously sick.”

Unexpectedly, I got some support from the peanut gallery.

“Yeah, man, we don’t want him dying in here.”

A big burly black guy had piped up from the corner. Smart. Appeal to their fear of a wrongful death lawsuit.

It worked. A few minutes later, a deputy appeared. He leaned over the sick prisoner and gathered just enough information for the paperwork he would have to fill out later.

“So what’s going on?”

“Man, I was in the hospital last week… I had a heart attack… I need to go back…”

He clutched at his chest and gasped for air. If he was acting, he deserved an Oscar.

The C.O. gave a go-ahead on his walkie-talkie, and a minute or so later some medics appeared with a stretcher.

I made sure to thank the officer, who asked me if I knew the guy. I shook my head. That was enough small talk for both of us.

There in the cavernous, windowless basement of the County Jail, the daytime fluorescents turned on. It was the closest we ever got to sunrise in there.

MCO 2017

July 29, 2017

Promotional Video

July 14, 2017

Fringe Benefits

When we lived in Maryland, my father worked for various paper companies. He held a series of middle management jobs that, during the 1960s, a man without a college degree could land mostly just by virtue of being a well-spoken WASP. Never the corporate type, he would have been far better suited to being the principal of a middle school, for example. But if he lacked the sharp elbows required to jockey his way to the upper echelons of business, his bended elbow was perfectly made for the era of three-martini lunches. As an exceedingly nice guy who held his liquor fairly well, he was an attractive drinking companion. He wasn’t into sports, but he knew to peruse the back pages of last night’s newspaper for scores; he wasn’t a womanizer, but could be trusted to keep quiet over a co-worker’s indiscretions. Everybody liked Steve Olmsted.

Occasionally he would take a business trip, and my mother would take advantage of his absence to dispense with the usual way of doing things. I now see that she probably hoped to recreate the clubhouse feeling that existed between her and us before we started grammar school. We could watch TV as we ate, usually the Dick Van Dyke Show or I Love Lucy. She would make a pitcher of very milky tea, and we would eat “crazy meals” marked by one big fun entrée like spaghetti. During the commercials, someone would ask: “Please don’t pass the butter!” – then declare—”Opposite Day!” (Only as an adult did I discover we hadn’t made up this game.)

When my father was home, dinner was promptly at six. In the warm months, around 5:45 or so, my father would stand on our porch, letting out a long two-toned whistle that would penetrate every far-flung nook and cranny in the neighborhood. We had five minutes to finish up whatever game we were playing, five minutes to run home, and five minutes to wash our hands and make sure we were wearing a clean shirt. I can’t remember ever being late for dinner.

If traditions such as “no advertising on the table” (like milk cartons), and monogrammed napkin rings were a legacy of my father’s upbringing, establishing a topic of conversation at the table was truly his own idea. He made sure that all of us had a chance to have our say. Otherwise, my brother Luke and I would dominate the proceedings – he being naturally bossy and me naturally talkative. My dad would try to sum up our various contributions or impose a theme of sorts. This worked fine in principle, but in practice his consumption of Zinfandel made him a weak Master of Ceremonies. More often than not, his illustrative anecdote would miss the very point he was trying to make, or his poorly constructed joke would land with a thud. We would feel embarrassed for him, me in particular. My mother would say “Oh, Steve” wearily, then suggest we clear the table. We would gratefully comply.

A few times when my Dad was going into his raconteur manqué mode, I stumbled onto a one-liner that managed to make his misfire seem like a set-up for my joke. Not only would the tension be broken, but everyone would burst out laughing, and I would take pleasure in saving my father from appearing foolish. I began to dread his stories and unfunny jokes less as I became better and better at turning him into Ed McMahon to my Johnny Carson.

Had his alcoholism turned my father mean or violent, life would have been more difficult, but less confusing. None of us except my mother had yet connected the cocktails to what seemed like a corresponding drop in I.Q every evening. I simply recognized that my dad was the parent who never seemed to answer a direct question with a direct answer, and would be perfectly happy to help you with your math but could never spot an error in your work.

I knew that when a TV dad came back from a business trip, the children clamored to find out what he’d brought home for them. I also knew mine wasn’t that kind of dad, but asked once anyway, just in case. Almost apologetically, he came up with one of those small little airplane bottles, empty of its bourbon. Nothing could have pleased me more.

Down in the basement, the younger four of us – Luke, Sandra, Erica and I – would play “White Trash Family.” The little airline bottle, filled with tea, was the perfect prop for Luke as the gruff, working class father. As we “ate,” he would swill it down, pretending to get increasingly drunk and abusive. This was thrilling to us in the same way a scary movie might have been had we been allowed to watch one. Sandra expertly played the cowering wife, keeping her head down, waiting for the first inevitable faux swat of many. I would vainly try to fend off the brute, as little Erica pretended to eat her invisible cereal while looking on in horror that was only half-pretend. (My poor sister could never understand why we couldn’t just play regular “house.”)

Eventually our pretend dysfunctional family evolved into a tableau for a bona fide haunted house. We nailed some two-by-fours across the underside of the steps, fashioning an enclosure in which I played a humped creature kept at bay by my brother, as he cracked a bullwhip against the concrete floor of the basement. Doubling as guide, Luke would greet the neighborhood kids at the basement door in a cape, a flashlight in his face providing ghoulish illumination. He would then take the wide-eyed guests along a path to a table where my sister Sandra, dressed as a crone, would offer them “eyes” for sale—bloody marbles in ketchup-stained cotton. Erica would be hidden under the table, poking at their little legs with something wet. Then came my animal shrieks from under the stairs, which would propel them to the exit going up to the garage and back into the driveway and street. Not bad for five cents, but since we wanted repeat business, we were always coming up with new features.

One day Luke and I took one of Erica’s old dolls, put a noose on her, and dangled her over a water pipe that threaded its way across the ceiling. I had the bright idea to light her hair on fire, a reckless suggestion for a goody-two-shoes like me, probably born from an intense desire to impress my older brother. I remember my shock when he agreed we should try it, as the de rigueur reaction to any idea generated by me was a scowl. Matches were taken from the ashtray where my father rested his pipe, and an attempt was made to drop the doll into an empty toy chest with her hair on fire.

We hadn’t counted on the flame-retardant nature of the doll’s nylon hair, so all we managed was some minor singeing, to my secret relief. (I liked the idea of being “bad” far more than actually being bad.) But the word “singe” evoked something else, another phrase that danced at the edge of my tongue. I had overheard it when my parents were discussing the merits of a job offer my father was considering.

Luke released the rope, and chest slammed shut on that poor doll. The moment called for some sort of caption, a signature, le mot juste. And suddenly the adult phrase I had recently learned popped into my head. I waited a full second, then delivered it in my best Vincent Price.

“Fringe benefits…”

Perhaps this is only mildly amusing in retrospect, but I can say without a doubt that at the time it killed. Even my brother, who usually went out of his way to avoid acknowledging my jokes, could not stop laughing. More importantly, neither could I. I felt the rush of being intentionally witty; the payoff of constantly juxtaposing different combinations of words and ideas against each other and then delivering the result at precisely the right moment.

Being funny was my first addiction.

In 1968, my father started working at the West Virginia Pulp & Paper Company. We loved calling him at work. The word “pulp” was just plain fun to say , and then there was the alliteration when it was followed by “paper.” Those poor receptionists had to say the whole mouthful every time, no doubt amused at the paroxysms of giggles this provoked when we heard: “West Virginia Pulp and Paper Company; how may I direct your call?”

In 1969, the company renamed itself Westvaco, and transferred my father to New York. The next year we moved to Mount Vernon, the first stop on an easy commute for my dad to Grand Central Station. The house was a perfectly lovely Tudor on a leafy street, but the town itself was far more Bronx than Bronxville, and our new schools were full of abrasive kids of every ethnicity speaking in a very scary accent.

The basement of our new home was serviceably dank and grey, but we felt no need to replicate our haunted house. The mean streets of New Yawk were plenty full of terrors, thank you very much.

June 17, 2017

June 15, 2017

Blink of An Eye (Excerpt)

Thank God Danny was here to give me the rundown on the rules governing the bathroom. Since we only have five commodes here, there are two designated “pissers” and two designated “shitters.” It is a real no-no to piss in a shitter or vice-versa. The fifth one is an emergency back-up if two of the sit-down commodes are in already in use, but you try to avoid that. Of course, all of this concern for hygiene doesn’t translate to anyone wanting to actually clean the bathrooms, so they bribe volunteers by giving them control over the TV. In fact, you can always tell that some kind of playoff game is going to be on when the straight guys are suspiciously willing to grab a mop in the morning.

Thank God Danny was here to give me the rundown on the rules governing the bathroom. Since we only have five commodes here, there are two designated “pissers” and two designated “shitters.” It is a real no-no to piss in a shitter or vice-versa. The fifth one is an emergency back-up if two of the sit-down commodes are in already in use, but you try to avoid that. Of course, all of this concern for hygiene doesn’t translate to anyone wanting to actually clean the bathrooms, so they bribe volunteers by giving them control over the TV. In fact, you can always tell that some kind of playoff game is going to be on when the straight guys are suspiciously willing to grab a mop in the morning.

Although this is worlds better than Sycamore, the dorm format makes it much harder to avoid the assholes, who, being assholes, have no idea they are assholes. I pretty much put up with their attempts to socialize, as I’ve learned by now that you never know when you might end up needing an unexpected ally. But after five minutes of the most inane conversation, I’ll gamely point out that I need to finish the letter I’m writing to get it in the day’s mail, to which they inevitably respond: “But dude, you’re always writing letters!”

We don’t have library privileges here, but there are twenty-some paperbacks floating around and I got my hands on Jean Auel’s Clan of the Cave Bear. I completely missed it back in the seventies, but am glad I did so that I could enjoy it fresh now. She’s such a good storyteller, and I’ve already spent hours submerging myself in the pre-historic world she creates. I also have my eye on a thick Pat Conroy I spotted, but the guy who’s reading it wants three soups to hand it over when he’s finished. Considering that these books belong to the whole dorm, I just frowned and walked away.

My bunkie’s name is Dick. He’s 58, a former investment banker and the father of three grown kids. He’s diabetic and suffers from poor circulation in his legs. Although he’s not gay, every night he “hires” one of the boys who doesn’t have money on his books to massage his feet. He works in the kitchen, and mostly pays them in food he smuggles out. (Because of his age, I think he’ll do most of his time here, which is why he has a job.)

Birch is a place for prisoners who would be in danger elsewhere, including informants. For this reason, people tend to shade the stories of how they got here even more than usual – just in case you’re a plant. That’s why I’m not entirely sure of the veracity of Dick’s story. It feels a bit like an account he learned to retell exactly the same way to a judge and a jury as part of a very specific legal strategy.

The short version: there was a company picnic, a softball game, and too much beer consumed. One of Dick’s sons got into a fight over a bad call, and an alarmed Dick swung a baseball bat at the aggressor, intending to hit him in the leg. However, due to a terrible case of momentary lost footing, the bat slammed into the side of the victim’s head.

Dick, horrified, called an ambulance; then fled the state to a second home, anxiously waiting to find out if he’d killed the guy. Thank God, the brain swelling went down and the poor man recovered. Dick returned from Arizona and turned himself in. He negotiated his way to a five-year sentence – aggravated assault and battery – but he’ll have to serve 80% of it.

It doesn’t seem like he could be lying about something that that so many people witnessed, but my gut tells me that he’s actually taking the fall for one of his sons, who sounds like a hotheaded alcoholic always getting into trouble. And of course Dick feels worst of all of for his wife, who was looking forward to a plush retirement and suddenly has to come visit her husband behind bars.

After he told me the story, everything I thought to say seemed like a hopelessly leaden platitude. Dick, however, knew exactly what to say, and I realized it would apply whether he had almost killed a man or actually taken the blame for a son who had.

“The moral of the story, my friend, is that your life can totally change in a split-second.” He snapped his fingers. “Like that.”

The truth of his words lay there like an 800-pound dead gorilla, and it felt like we were both about to descend into a suicidal depression. I decided to lighten things up.

“You know what’s worse, Dick? Sometimes things can change gradually, over a 10-to-15 year period.”

For the longest second, I thought I’d completely overthought a punch-line, but then he got it and let out a deep, booming laugh that literally shook the room.

MCO 2017

May 31, 2017

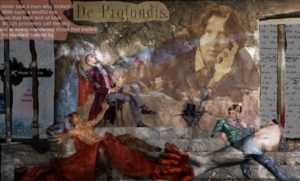

Lettre d’Oscar

Dear Mark,

Indeed, the parallels between us are striking. A youth gifted with familial love, education and talent; a midlife filled with promise and success, then a vertiginous fall from grace at the cusp of middle age – both of us 44. Neither of us could escape the impact of wider circumstances beyond our control – in my case, society’s hostility toward love between men; in your case, the woeful ruination of AIDS and addiction upon a generation. But we are both responsible for the hubris with which we tempted fate – inviting consequences we could have easily avoided. And prison was the ultimate consequence for us both.

As you know, my two years at hard labor broke my health, but I could never quite regret the experience. Like you, I have always felt art redeems everything, and it is unimaginable to me now that I would look back on my life’s work without De Profundis or The Ballad of Reading Gaol. I daresay you feel the same about Ink from the Pen – as you say, the only thing harder to imagine than going to prison in the first place is now not having written this book. The one story I was most drawn to was Friendless Stranger, because I remember so well my worst week in prison: the overwhelming fear and cacophony, the uncertainty whether my cellmate was friend or foe. And then the poem you shared within that chapter itself – Strange Friend– is quite haunting, no wonder “Drifter” stole it for Talent Night.

I actually read “Because the Stars Incline Us” aloud at our last salon and the Bronte sisters thought it was marvelous. (Norman Mailer scowled, but he scowls at everything.) Your Uncle was right, by the way, spirits stay in this “waiting room” until that have been sufficiently forgotten to move on – so that leaves quite a group of glittering artists here. We don’t mind. It means we are remembered, and what could a writer want more?

Don’t hurry to join us, young man, you have many more years of creativity ahead. But when you do get here it will be a great pleasure to throw you a grand dinner party, and you can regale us all with the tale of how you almost got away with faking your own death.

P.S. Oh I wouldn’t worry about claiming we have the same birthday. What’s one day and 104 years apart in the grand scheme of things?

https://www.amazon.com/Ink-Pen-Prison-Mark-Olmsted/dp/0692784144/

May 28, 2017

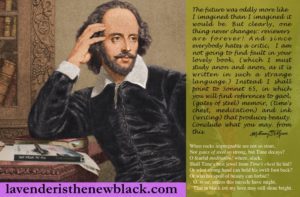

My “inter-review” with Shakespeare

The future was oddly more like I imagined than I imagined it would be. But clearly, one thing never changes: reviewers are forever! And since everybody hates a critic, I am not going to find fault in your lovely book, (which I must study anon and anon, as it is written in such a strange language.) Instead I shall point to Sonnet 65, in which you will find references to gaol, (gates of steel) memoir, (time’s chest, meditation) and ink (writing) that produces beauty. Conclude what you may. from this. — William Shakespeare

When rocks impregnable are not so stout,

Nor gates of steel so strong, but Time decays?

O fearful meditation! where, alack,

Shall Time's best jewel from Time's chest lie hid?

Or what strong hand can hold his swift foot back?

Or who his spoil of beauty can forbid?

O, none, unless this miracle have might,

That in black ink my love may still shine bright.