Jane Little Botkin's Blog

August 15, 2025

Writing an Honest Biography or Autobiography

At the WWWA conference in Amarillo in 1983, famous western biographer J. Evetts Haley recalled reading Thirty-One Years on the Plains and in the Mountains when he was a boy. The author, Captain William F. Drannan, claimed to be an adopted son of Kit Carson. Stories of trapping beaver, hunting buffalo, and chasing wild horses all over the West immediately enthralled ten-year-old Haley.” Much later, as an adult, Haley discovered the book to be a “monumental fraud from the standpoint of history.”

Ten-time Spur Award winner Johnny T. Boggs had a similar experience. When he was young, his father read Quentin Reynolds’s Custer’s Last Stand to him. Boggs was convinced that the narrative was the “greatest book ever written.” If you ask him, he can tell you the ending of the book, close to verbatim: “Two bullets hit Autie at the same time … He reaches for his brother Tom. And they die as they had lived—together.” An older and wiser Johnny Boggs realized that war correspondent Quentin Reynolds unfortunately made up—in Boggs’s words—”a lot of crap.”

Yet, both Haley and Boggs later reflect that their earliest biography experiences were memorable—and life changing. Haley admitted that this one book shaped his youthful character, a true story that fascinated him with the “possibilities of the West.” As for Johnny Boggs, Custer’s Last Stand, flawed as it was, helped influence his journey as a successful journalist and fiction writer, one who researches history and setting to help create captivating books set within accurate context.

And there’s the rub. Not just nonfiction writers—biographers and other historians—but all western writers are inspired by true events and have a responsibility to write authentically when it comes to context. But there is another revelation regarding Haley’s and Boggs’s words. A desire for escapism is the real reason many folks read western books. An allure to reading biography and autobiography, especially, is about losing ourselves in someone else’s life. And we don’t want to discover later that the main character and his or her narrative are phony. The narratives must be, more than anything else, honest.

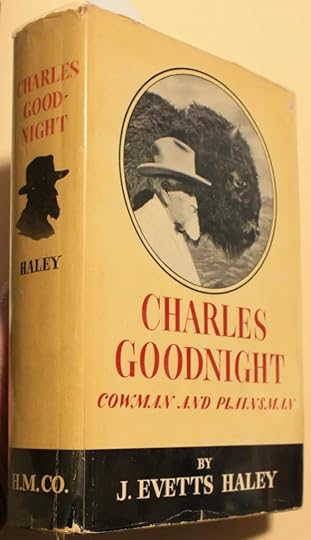

Those who love reading biographies often identify with the main character. I submit that the writers are often smitten with their subjects as well. As a biographer, an author may have an emotional connection, at some level, with whom he or she is going to research and write. During his Owen Wister Award recipient speech in 1983, Haley also told WWA members that he chose Charles Goodnight as a biographical subject because he made the “goodest” impression and moved him deeply. After meeting Goodnight— “that dominant western character, the greatest of America’s trail driver and the greatest of open range cowmen”—Haley described being left with an ambition to write the cattleman’s story, “‘a burning fire’ that sometimes you just have something to tell.” Obviously, Haley was taken with Charles Goodnight, and perhaps one could argue overly so, in his Charles Goodnight, Cowman and Plainsman(1936).

With that said, a biography (and autobiography) must be unbiased. Authors must present the subject—unvarnished—or the book may not be taken seriously. Well-known western historian and another Owen Wister award-winner, Robert Utley said in an interview:

I believe it especially important to bring that mindset to bear on people or institutions that have been buried in legend and romanticism and have spawned polarized public images. The challenge is to strip away the layers of error and myth to get as close as possible to the underlying reality. Rarely are people or institutions (composed of people) all good or all bad. Finding the balance between the poles is a historian’s (and biographer’s) duty. [Texas Monthly, November 2002]

When I wrote The Pink Dress, A Memoir of a Reluctant Beauty Queen, I had to step back and view myself as a character, a historical figure during America’s Counterculture. I had to strip away MY biases and present the story accurately, even if I didn’t like who I was at a moment in my life. I had no agenda but to tell a historic narrative (because I’m old)! Yet, bringing in people to my narrative, who had an impact on my life’s decisions, triggered emotional reflection. I couldn’t lie. This was me!

So, what should a biography do? How about enlighten and entertain? I would also add contribute. If writing about a famous person, biographers should research new evidence. They should present unusual or relatively unknown information—and document it. Look at all the Billy the Kid, George Custer, and Wyatt Earp books. In one quick survey, I counted thirteen books on Billy the Kid (including one by Robert Utley), seventeen books on George Custer, and a whopping twenty-three books on Wyatt Earp. Which biographies are tired repeats, and which books offer something new to the western reading audience?

If not the first biography about an individual, the author should write the narrative differently—provide a new twist with fresh, but accurate, information. On the other hand, if the subject is unknown, look for the value of the story and sell it to your audience. Otherwise, why should people read the biography? The point is, you wouldn’t be writing about a person unless that person had a relevant narrative. So, find the story!

To that purpose, how does one uncover a story? Sometimes it just pops up in the most unlikely place. During a visit to the Charles and Mary Ann Goodnight Ranch House Museum in the Texas Panhandle, I inquired if there were any books on Mary Ann Goodnight. The docent in charge quipped, “No one has written a biography on Molly Goodnight, and besides, there is only a smidgeon of information!” She squeezed her index finger and thumb together. When she added, “No one would want to read anything about Molly anyway,” the back of my neck prickled. I determined I would find the story. And, sure enough, there is a good one, and Mary Ann Goodnight’s biography, The Breath of a Bison, should be out late 2026 or spring 2027 from the University of Oklahoma Press.

Working the story often begins effortlessly, but don’t let easy-access resources fool you, the researcher. As an example, one can certainly find information in online frontier newspapers. But as western biographer Bill Markley told me recently, concerning conflicting newspaper reports in his research, you can’t believe everything you read in papers. I strongly suggest, don’t believe anything you read. Find a second or third source that supports newspaper information. Remember, papers were often corporately owned and politically controlled. Still, memberships to www.newspapers.com and www.genealogybank.com are worth the money. Chroniclingamerica.loc.gov is free as well as various regional sites, such as www.coloradovirtuallibrary.org.

Often states facilitate online research that can offer important contemporaneous observations. Keep in mind that during the Depression, federally employed interviewers canvassed pioneers across the country, collecting and transcribing oral histories, most all available online in various state archives. As examples, check out the University of Oklahoma Library’s online Indian-Pioneer papers and Wyoming State Archives’ oral history database with access to interviews. The online Portal to Texas History offers oral histories, documents, and newspapers.

Other useful online research may come from www.Ancestry.com (genealogy) and www.Fold3.com (military/war records). With Ancestry, accept information with skepticism. Still, a researcher can make connections to his or her subject’s descendants that may result in the discovery of significant family documents, old journals, photos, and passed-down stories. Because of connections like these, I was able to find a treasure trove of Goodnight letters that had been stashed in the eaves of an old barn. In addition to print resources, family anecdotes, flawed as they often are, almost always have a mustard seed of truth that can be researched. Be sure you do!

The biographer must also walk the story and taste it. Get out of your comfy office chair and travel the subject’s life narrative. I even walked the story for my autobiography, returning to El Paso multiple times. With Frank Little, I traveled his journey in ten states, investigating small libraries and historical societies along the way. I interviewed descendants of people who knew my uncle (the libraries knew who these folks were). I looked at the natural surroundings and tried to place photos of old structures where new ones had been built. I stood where Frank stepped into a knife fight on the hump of Tiger Hill in Drumright, Oklahoma, and later in the middle of Wyoming Street in Butte, Montana, where he was abducted and murdered. My walk took me six years, and only then did I begin to write. And this leads me to my last point about researching for a biography.

Biographers, who churn out books quickly, often fail in attaining comprehensive research. No matter if a biography takes six years or three years or two years to research and write, ultimately you, the writer, want to produce a biography that matters, that contributes. J. Evetts Haley said that “if you ‘pop off on radio’ (think podcast today) or ‘get caught on TV’, what you say is gone almost forever. But if you write it down and then have it printed,” then “whether you want to or not, it’s possibly for eternity because it is on the record, and you can’t call it back.” Keep that in mind.

What if you, the biographer, do not find the story you thought existed? Perhaps you predetermined a theme and selected research that supported your supposition, and these other pesky details keep interfering with your narrative thread? Rethink the process. Think of your research journey as an adventure in discovery. Well-known biographer David McCollough, in an interview piece regarding his writing John Adams, stated, “The more you know, the more you want to know…thinking is just as important as the research—think about what is not there.” Intellectual curiosity matters, and so does honesty. Take the time to research the entire story and document it.

In the 2002 interview, Utley states, “In evaluating the thought, decisions, and actions of people, I place great value on the test of plausibility: Given the evidence, is this likely to have happened?” Utley bails out the biographer. If you cannot prove an assertion to be correct or incorrect, there is a wonderful plethora of adverbs that can bail you out, words like possibly, perhaps, likely, and maybe. If you are down to two conflicting accounts, present them both. Let the reader come to his or her own conclusions. It would be dishonest to make that judgement for the reader.

If all else fails, do not force a story and do not be afraid to walk away.

In his John Adams interview, McCollough provides more thoughtful tips for the biographer. First, write to the ear and not just the eye. Use your computer’s “Read Aloud” function to listen to your text at intervals. Pay attention to syntax, word choice, etc. Your ear should catch errors.

Learn how to edit yourself. Southwestern biographer Leon Metz once asked his mentor C. L. “Doc” Sonnichsen, another biographer and University of Texas at El Paso professor, to review his work. “Leon,” Sonnichsen said, “You can say ‘done went’ and get away with it sometimes, but you can’t write ‘done went’ and ever expect people to read it.” Metz, a voracious reader as a boy, had performed miserably in language arts in school. He was a terrible speller and wrote as he spoke when he began his early career. Because of his editor and mentor, Metz learned to edit himself even as he became a better writer. In 1996, the WWA presented Metz a Spur Award for his biography on lawman John Selman, one of his many excellent biographies. Find a knowledgeable mentor.

Beginnings matter. Consider using a prologue that teases a main event in your subject’s life. Use chapter openings (factual, of course!) that make the reader want to read more.

Don’t tell me, show me. Every good writer should know this. Biographers need not write in linear, academic narratives. Consider your audience. Appealing nonfiction does not read like a textbook. Your writing also should have voice. Just because your writing is nonfiction does not mean you can’t incorporate imagery, flashbacks, and foreshadowing. It doesn’t hurt to go to a western fiction writing workshop where you can get ideas about how to make your manuscript more interesting, even structurally. And no, this is not creative nonfiction writing that I am describing—it’s effective writing.

With that said, McCollough reminds us to capture character with a minimum of strokes. Words do matter. Write with precision.

And finally, get up and dance; don’t tap your foot first. Like fiction writers, get the audience’s attention from the get-go. Dive into your subject with energy.

Above all, be honest. Leon Metz told an El Paso Times interviewer in 2010 that when he was a boy, he loved The Saga of Billy the Kid by Walter Noble Burns. It never occurred to him then that people would lie in print, but, Metz stated, “I found it out later, when I learned more about the story.” And he also remembered the lesson.

J. Evetts Haley stated, “There’s an obligation for the written and to the writer. When you put it in writing, it ought to be right.” That’s the first rule of good biography and other nonfiction.

Don’t settle for less.

The post Writing an Honest Biography or Autobiography appeared first on Jane Little Botkin.

May 29, 2024

Slow Living in the White Mountain Wilderness

Eight years ago, my husband and I decided to purchase a recreational home, i.e., a cabin, in Ruidoso, New Mexico, almost ten hours from our primary home in Dripping Springs, Texas. We first met on Sierra Blanca’s ski slopes in 1976, so the location had a romantic appeal for our newly retired lives. Besides, our youngest son and daughter-in-law, who recently completed post graduate degrees from Colorado State University, had selected the resort village to begin their professional lives—veterinary medicine and ecological work. Ruidoso was a midway point between Texas and Wyoming where both sets of parents lived. Our other son and his family resided in Central Texas. Exciting, right? The best of both worlds. Then Covid hit.

Our hometown in Central Texas soon drew a disaffected group of Americans from all over the States, but especially from California. These newcomers brought money, traffic congestion, and a subtle change to the culture of our area. I’m not saying that we dislike Californians, so don’t get me wrong. But we had built our home in a rural area, and our children had attended a rural school under the moniker, “Dripping Springs, just west of weird!” Austin bled into a bloating Dripping Springs and, many might say, brought some of its weirdness with it.

Soon, we could hear big rigs and sirens on highway 290 plus other sounds common to city life. New construction to accommodate the sudden population growth sent filth into a verdant creek behind our house, and industrial noise drowned out our waterfall’s soothing sounds. We reluctantly forbid our grandchildren to swim in a pond where their parents once cannonballed from a limestone ledge into cool summer waters.

So, we sold our home of thirty-four years—a home we had built and perfected—to a Californian with deep pockets.

We purged almost 45 years of possessions, packed what was left in five storage lockers, said goodbye to dear friends and family, and headed to New Mexico. A small elk-hunting cabin set on twenty-acres and isolated on a mountain slope awaited us in the White Mountain Wilderness.

Slow Living, an Oxymoron?

I first heard of the term “slow living” in an interview-article with Little House on the Prairie’s Melissa Gilbert several years ago. She had called quits in Hollywood, and along with her husband, purchased a New England farm to begin slow living. You know—grow your own vegetables and fruits, gather fresh eggs, cut flowers, and raise various pet farm animals—but in surroundings where Nature cooperates.

My husband and I soon realized that this concept near described what we wanted in our lives. He could work in a new workshop on projects, and I could write. He could hunt, and we could hike and camp out where no commercial lights would dim our starry night skies.

We desired the isolation that living below Nogal Peak afforded. Who cares if we were snowed in! Sure enough, my husband soon had to purchase snowshoes.

We also understood that an 847 square foot cabin would not do. Construction began around the cabin. During the process, we soon realized that nothing would be “slow” about living in a wilderness area. Danger is inherent.

We’ve had mountain lions, peccaries, and one old bear. Wicked 90 mph winds, hail, and blizzards. Yet, the most perilous element of our new lives, an aspect that races one’s heart instead of slowing it down, was wildfire. It, too, is a living, breathing entity.

Wildfire!

Unlike Central Texas when the bluebonnets are in bloom on cool, April mornings, New Mexico’s fire season encompasses the entire spring when the atmosphere and ground is generally thirsty. Red flag winds, like devil breaths, contribute to the danger, spreading or even causing wildfires.

For most wilderness residents, June arrives inconveniently, dressed in an assortment of tourists—mainly campers—who must be reminded of safe fire practices. With trepidation we watch the trailers, ATVs, and cyclists pour into the White Mountain Wilderness on our road in early summer.

Doesn’t matter that about twenty miles away, Capitan’s Smokey the Bear Museum features the icon’s story of being discovered while clinging to a pine branch during a Capitan Mountain fire. The bear’s message, “Only you can prevent forest fires,” seems to have been buried along with him on the museum’s grounds.

When monsoon season finally arrives in late July, everyone breathes a small sigh of relief. Rain is a cure-all.

We’ve been evacuated three times since we made our move in 2021. Though after each fire evacuation, we’ve become better with the process, one thing we have learned is that it isn’t necessarily the fire that causes destruction. Human error is what makes for a disaster, The first time we were affected by New Mexican wildfire was in April 2021. I was not even home but researching for my Mary Ann Goodnight biography in the Texas Panhandle. My husband called me.

“Janie, we’ve been evacuated,” he calmly said.

“What about Axel?” My response was more frantic. Our dog was more precious than anything in our house. This was a dumb question. Of course, he had Axel.

“I’ve got him.”

“What else did you get?” I asked.

“My hunting stuff—and dogfood.”

Silence.

“Did you happen to get any of my clothes?” I asked.

“Janie, we weren’t given much time. I grabbed what I could.” I could tell my husband regretted even telling me. Of course, he had his clothes.

In honesty, if the house burned, I could purchase new things. I had clothing in my suitcase. Why was I being so trivial? But all my book research? I thought about my library and became sickened. What about the 1845 family Bible wrapped in my armoire? Fire makes you contemplate what’s most important—if you have time for such consideration. My husband and dog. Definitely. Nothing else should matter.

“Don’t hurry home. There’s no place to stay.”

That night, my husband and Axel slept in his pickup truck at a rest stop where they could watch what would be called the Three Rivers Fire. The fire, igniting on the other side of a mountain overlooking our cabin, tried to roll over into our wilderness area and Nogal Canyon.

Mercifully for man and dog, the evacuation was brief. The fire burned only 5,854 acres and was contained within two months. Arson.

Afterward, we began clearing beetle-infested pinons and limbing pines and junipers (also known as gasoline trees). Trees twenty feet apart, limbed up at least twelve feet, etc. I raked old pine needles, bagging them and piling the black bags for my husband to put in our construction dumpster.

Actually, we had previously experienced fire in the Ruidoso area. In 2012, we helped move our son and his wife from Fort Collins during the High Park Fire, one of the most destructive wildfires in Colorado history. It began in June, a product of lightning and drought, burning 87,415 acres along the Cach La Poudre River in the mountains west of the city. As we loaded the kids’ U-Haul truck and other vehicles, ash fell on our heads. We backed out of the driveway, while helicopters labored overhead, their bags full of Horsehead Reservoir water.

When we arrived in Ruidoso, one of New Mexico’s largest wildfires ever was in progress—the Little Bear Fir—still the most destructive to date at 44,350 acres. We unloaded belongings with ash again falling on our heads. The cause? A small fire caused by lightning, mismanaged when a bureaucrat decided to let it burn itself out despite dry and windy conditions.

Our second evacuation was the Nogal Canyon Fire in April 2022. Again, I was not home but researching in Pueblo, Colorado, when my husband got the call. And again, he took the same items plus Axel.

“No need to rush,” my husband said when he called me. “Finish what you are doing there. There is nothing you can do here.”

Then he added, “Besides, we have another fire in Ruidoso and the kids have been evacuated too.” Of course, I immediately left for home, noticing what I thought was a dust storm to the west near Las Vegas, New Mexico. I later learned it was the Hermits Peak-Calf Canyon fire, which had started several days earlier from a prescribed burn. As a result, firefighting resources would be strained. The Hermits Peak fire was a monster and is the largest New Mexico wildfire in history at 341,735 acres.

Within a couple of hours of each other, our two Lincoln County fires had started—due to high winds bringing down power lines. The McBride fire burned 6,157 acres during five weeks and killed two elderly residents. The Nogal Canyon Fire burned 412 acres up to within 700 yards of our home. The entire family spent the time together in a rental in Capitan. Though the family time was rewarding, I decided I hated April.

During the fire, we worried about our ancient pines, some several hundred years old. What if our forest burned around us? Would we want to live in the same place? The McBride fire scar was not pretty, and certainly no pine trees had reappeared in the ten years since the fire. Nature takes her time. In the end, we decided that we wanted to stay in our home no matter the environment.

So, we reevaluated our setting. Was our house fire ready? Can anyone truly be fire ready?

We ripped off the new cedar siding from our home, ordering a material called Ever-log out of Missoula, Montana. I won’t lie. It was expensive and our contractor cursed as he learned to install the heavy new material on our home, the second structure in all of New Mexico to use it. A concrete siding that looks like real logs, one that will survive a three-hour forest fire’s direct heat. Best, you must touch the material to see it is not wood. We used other non-flammables for decks and trim. We replaced wood posts with iron. We carpeted gravel under all decks, extending rip rock ten feet from the house. We installed a new metal roof. We used foam insulation so that attic vents wouldn’t be needed.

Now we have a new fire, the Blue 2 fire. A two-acre lightning fire two weeks ago, another forestry bureaucrat decided to let it burn itself out, despite the red-flag warnings. Go figure. The fire is now over 7,000 acres and approaching our precious Nogal Canyon in the White Mountain Wilderness. Our beautiful Bonito Lake, cleansed of ash and chemicals and restocked with fish after the McBride fire’s damage twelve years ago, burned for a second time on the very day it was to reopen.

And, again, we find ourselves evacuated.

If we get another reprieve and our home still stands in the weeks to come, I’ll first thank God and then the firefighters who worked so selflessly to save our forest, home, and lives. Because of them, we’ll be able to return to our notion of slow living.

As for the other idiots—the ones who put firefighting men and women in danger because of flawed decisions; the ones who waste taxpayer money to fight fires that never should have developed; the ones who follow governmental policy to let Nature take her course when other factors say otherwise, the ones without commonsense—all I can say is shame on them. Fire cleanses for certain—even restores Nature’s balance—but black-and-white decision-making is wrong and narrowminded. As for us, I plan to continue throwing seed to what I call “my blue chickens,” the Stellar jays that enrich my life each morning.

One thing for sure, while slow living is not for the weak, it is surely worth it.

The post Slow Living in the White Mountain Wilderness appeared first on Jane Little Botkin.

April 24, 2024

A Song, a Movie, and a City

When Marty Robbins first made a West Texas town famous with his hit song “El Paso,” he did more than just earn a No. 1 country single for the original version, as heard on the 1959 album Gunfighter Ballads and Trail Songs. He changed the face of a city struggling to become consequential within the Lone Star State.

It’s true that El Paso sits in isolation from the rest of the state of Texas—635 miles from Dallas, 600 miles from Austin, and 551 miles from San Antonio. El Paso, with its sprawl around the southern tip of the Franklin Mountain on the Mexico-United States border, seems more like a foreign country. The Mexican state capitol of Chihuahua is only 239 miles from El Paso.

At the time of Robbins’s recording, Dallas, in northeast Texas, was already the site of gleaming high-rises, fine couture, and its famous Market, while oil derricks and dollar signs represented the south Texas city of Houston on whimsical maps. To many elsewhere in the state, El Paso was just western spit in the sand, far from anything else of significance. But Robbins’s western ballad changed this notion dramatically, even as the song reinforced El Paso as a romantic—but wild—frontier city.

So popular were the song’s lyrics that many folks simply referred to the song “El Paso” as “Rosa’s Cantina.” In the fictional cantina, a cowboy falls in love with a “wicked” Mexican girl named Feleena. After a gunfight where the smitten, jealous cowboy kills another “wild, young cowboy,” he flees on a horse that “looked like it could run” into the badlands of New Mexico. Not a far stretch for folks to believe since some Texas residents thought El Paso should be part of New Mexico anyway. His “love stronger than death,” the cowboy returns to his Feleena, only to die in the arms of the Mexican maiden.

After Marty Robbins recorded the gripping hit song, El Paso became further engrained in Western lore as an enduring frontier haven for desperadoes roaming dusty streets. Aside from my dad’s fascination with Western literature and movies, it is likely that our family move to El Paso in 1961 was influenced by Robbins’s song, which was like musical cinema to listeners’ ears. Aside from Tucson, living in El Paso was about as close to the Wild West as we could get. My father had a fascination with the escapism that Western film and music delivered. And he was not alone.

The Prequel, Riding Success Western Style

Like a hit movie’s prequel, Marty Robbins came out with a second ballad titled “Feleena” (of El Paso) in 1966, part of a collection of songs recorded for his album The Drifter. This ballad, too, ensnared the same audiences enamored with Old West allure within the Western musical genre. Robbins’s new single transformed forbidden love, heartbreak, and death into a universal narrative of love, tragedy, loss, and remorse.

In the song, Robbins croons the back story of the same Mexican maiden, born to young Mexican parents in a New Mexican shack. After all, one can stand outside El Paso and throw stones across border lines into Mexico, Texas, and New Mexico almost simultaneously! An ominous stage is set for sequential lyrics when lightning streaks the sky and “loud desert thunder” shakes New Mexican sands at Feleena’s birth. Nine verses later, a teenaged Feleena takes her young cowboy’s gun and shoots herself, falling dramatically atop his murdered body. The final verse borrows a variation of what every full-blooded Texan recognizes, the La Llorona story. “Out in El Paso, whenever the wind blows,” you can hear a distressed woman crying in the breeze—Feleena calling for her lover.

The spinoff made it to the top of the Billboard Hot Country Singles chart, though it would never be as endearing as the original “El Paso” tune. Briefly, El Paso thrived on this song’s celebrity too.

Hollywood Invasion

A natural extension of these classic ballads triggered cross-over appeal to El Paso’s sister city—Juárez. The ballads’ Wild West storylines, in tying Mexican and American culture together in a shared frontier history, now captured the imagination of Western film fans.

Ciudad Juárez, has always been the stuff of legends, whether about its famous college hangouts, visiting celebrities, or outlaws. Hollywood discovered the old city’s eccentricities decades earlier. Famous actors and actresses, addicted to romance, arrived for quickie marriages and divorces—and Kentucky Club margaritas, the famous cocktail allegedly invented there in 1932.

Tens of dusty-framed black-and-white glossies decorate walls deep into Kentucky Club’s narrow recess, celebrating its most famous guests—many Hollywood performers, sports figures, and even outlaws. Al Capone and Bob Dylan, Marilyn Monroe and Elizabeth Taylor, Tommy Lasorda and Oscar De La Hoya, John Wayne and Steve McQueen, and a Miss Universe, to name a few.

As early as 1954, many American Western movies were filmed in Mexico, often in Durango. Famously, Sam Peckinpah had also directed films in Mexico, the most controversial one with actors William Holden and Ernest Borgnine. The Wild Bunch, a film about the 1913 Mexican Revolution involving the border of Mexico and Texas, was red meat for El Pasoans. But it was not filmed near or in El Paso, having been filmed in 1968 within the Mexican states of Coahuila and Durango.

Though the song “El Paso” was recorded in 1959, no major Westerns had been made in or near El Paso since a 1953 Fort Bliss tale set during the Korean War, called Take the High Ground. In fact, the only other movie ever filmed in El Paso had been a 1922 Gloria Swanson film, The Husband’s Trademark.

Changing the Face of El Paso

When Sam Peckinpah and actors Steve McQueen, Slim Pickens, Ali MacGraw, Ben Johnson, and Sally Struthers, et. al, landed at the El Paso International Airport to film The Getaway in 1972, the first music they heard was Marty Robbins’s “El Paso,” playing in a continuous loop. Utilizing Robbins’s famous ballad as a reminder of El Paso’s colorful history, the film location, now named as an “All-American City,” had recently adopted the mantra, “El Paso, You’re Looking Good!” What better place to film a movie about an ex-con-bank robber and his true love, a double-cross, and a flight toward Mexico with police in pursuit (including fantastic car chase scenes, one beginning at the Oasis Drive-in, my old high school haunt). After all, Robbins had already memorialized the city with a barroom gunfight, rapid escape into the hills, a posse in pursuit, and a death in the arms of a loving woman.

One hundred technicians, artists, and actors descended upon the city to make the first movie since 1953. Peckinpah and co-producer David Foster, after taking a Jim Thompson 25-cent Signet paperback and turning it into a Walter Hill screen play, soon began filming in 114 locations, with El Paso handling fifty percent of the action.

For months, El Paso’s newspapers shared everything that had to do with The Getaway production, especially the fresh national exposure El Paso was receiving as a movie production site. Dollars poured into the city to pay for carpenters, electricians, drivers, cleaners, car and truck rentals, food, extras, and filming major actors wearing Tony Lama boots. One El Paso newspaper reported that El Paso seemed to be “coming of age.” An investor even offered to build a street near the city, along the same design as Old Tucson, to be used for future television series, Westerns, and other feature films.

But the euphoria was short-lived. El Paso city officials surrendered to the notion that an updated image from its Marty Robbins recording was inevitable, if not essential. When professional golfer Lee Trevino appeared center stage within the city, its mantra “El Paso, You’re Looking Good” evolved into a more contemporary and popular theme of resilience and hope. Citizens donned black, red, and white colors, and wore golf caps or sombreros, to honor a living Mexican American sports legend. Fickle cities—El Paso and Juárez —both became infected with “Trevino fever.” An era was over.

An Introspective Lens

Marty Robbins wrote a final song, completing what would become known as the “El Paso” trilogy. “El Paso City” hit the charts in 1976. Its lyrics nostalgically return Robbins to his original “West Texas Town of El Paso” narrative while aboard an airplane soaring over the western city. The narrator contemplates the lyrics of the first ballad and wonders if he could have lived in another time— if he could have been the cowboy in “El Paso City, by the Rio Grande.” Could he have been the gunslinger in the city below? Could he have shared a dying kiss with his lover Feleena? One thing is certain. The narrator feels that in another time— in another world—he might have lived in El Paso.

****

In 1998, Marty Robbins’s 1959 recording of “El Paso” on Columbia Records was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame. The membership of the Western Writers of America chose “El Paso” as one of the Top 100 western songs of all time in 2010. And, in 2024, the Western Writers of America inducted Marty Robbins into its Hall of Fame where, along with other prestigious western writers, he is featured at the McCracken Research Library in the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming.

And, if anyone is wondering, Rosa’s Cantina, opened in 1959, occupies a spot near the railroad tracks off Doniphan Drive, not far from Smelter Town and the Mexican border, in El Paso, Texas. Inside, Marty Robbins’s photo memorabilia and themed menus keep the famous ballad alive. Whether the tavern inspired Robbins is vague. But I prefer one writer’s notion that when Marty Robbins passed through town on tour, he came upon Rosa’s Cantina, and “it somehow stuck, lending him the perfect artistic license to incorporate the bar into his song.” And with that, Marty Robbins made the West Texas town of El Paso memorable.

1673words

Submitted by:

Jane Little Botkin

Vice-President of Western Writers of America

April 11, 2024

Contact: Jane@Janelittlebotkin.com

About the author:

National award-winning author Jane Little Botkin melds personal narratives of American families with compelling stories of western women. Her books have won numerous awards in biography, western historical nonfiction, and women’s studies, including two Spur Awards, two Caroline Bancroft History Prizes, the Barbara Sudler Award for best book about the American West by a woman, Women Writing the West’s Willa Literary Award biography finalist, High Plains Nonfiction Book Award Finalist, Foreword Indies Bronze Award in women’s studies, Sarton Book Award finalist in women’s studies, and Independent Publisher Book Awards’ Bronze Medal for Best Regional Nonfiction.

Recently completed, The Pink Dress, Memoir of a Reluctant Beauty Queen will release September 10, 2024 (She Writes Press; Simon & Schuster Distributor). She is currently working on The Breath of a Buffalo, a biography of Mary Ann (Molly) Goodnight, tentatively scheduled for release in 2026.

A member of Western Writers of America since 2017, Jane sits on its board of directors and serves as vice president. She also judges entries for the WWA’s prestigious Spur Award, reviews new releases, and writes articles for various magazines. A late-bloomer, Jane served as a public-school teacher for thirty years before turning to historical investigation and writing. In 2008 the Texas state legislature honored her career in education by formal resolution. Most notably she directed her students to produce and publish a collection of oral and documented county history essays annually. Now she blissfully escapes into her literary world in the remote White Mountain Wilderness near Nogal, New Mexico.

The post A Song, a Movie, and a City appeared first on Jane Little Botkin.

March 11, 2024

I Accepted a Challenge: Researching and Writing Mary Ann Goodnight’s Story

During a visit to the Charles and Mary Ann Goodnight Ranch House Museum several years ago, I inquired if there were any books on Mary Ann Goodnight. The docent in charge quipped, “No one has written a biography on Molly Goodnight, and besides, there is only a smidgeon of information!” Then she squeezed her index finger and thumb together, not realizing that her response to me would become a years-long challenge.

Mary’s story has never been told, though it was she, not her famous husband, whose continuing actions preserved the Southern American Bison herd from extinction. Charles Goodnight ordered the extermination of 15,000 bison within Palo Duro Canyon, Texas, in late 1877.

Several authors previously produced biographies on Charles Goodnight, including the most successful and accurate telling by J. Evetts Haley, a classic in western history and especially Texas history. In J. Evetts Haley’s Charles Goodnight, Cowman and Plainsman (1936), now a University of Oklahoma Press property, Mary Ann Goodnight’s portrait is sketched, albeit marginally. Not surprising if one considers the decade in which Haley’s famous biography was written. Biopics of women were uncommon, and, besides, Charles Goodnight’s interview answers and essays for Haley focused mostly on anecdotal information and his well-known accomplishments on cattle trails and with the Texas Rangers—historically, masculine endeavors.

For today’s western history lovers and serious historians alike, Haley’s biography enthralls while significantly contributing to the deep pool of recorded Texas history. Though in his early life Goodnight abhorred attention and adulation, his elder voice, slightly self-aggrandizing at times, colorfully repeats the same tales that tantalized those who once sat around the famous Goodnight dining table—right down to his capturing orphan bison calves that would eventually renew the American southern bison herd.

Haley only witnessed a shadow of Mary Ann Goodnight in 1925, a woman suffering from late-stage dementia, her obsession with saving the bison and charitable endeavors hidden from his first interviews with the old man at the Goodnight Ranch. Within Haley’s biography, Mary’s only mention relating to the origins of the famous Goodnight herd is that she had been “distressed by the slaughter” of 1878—Charles Goodnight’s words. But for me, a 21st century researcher, Charles Goodnight’s deliberate omissions to J. Evetts Haley clearly stand out and will be remedied within my upcoming biography on Mary Ann Goodnight—The Breath of a Buffalo.

Despite the Goodnights’ diverse philosophical views—beginning with saving four bison calves—their marriage was a fifty-six-year partnership in business enterprises, educational endeavors, and community service. Research also reveals a life-long love story between a prickly, illiterate, and foul-mouthed trail driver and a fun-loving but refined, petite schoolteacher who respected each other’s differences and shortcomings.

To understand how the Goodnights’ personal relationship evolved, this biography will scrutinize Mary’s life, beginning with her roots in Dyer County, Tennessee; her family’s move to Texas because of a pledge to Senator Sam Houston; and the chaotic setting that was northeast Texas before and after the Civil War. The narrative follows Mary when she gave Charles Goodnight an ultimatum demanding marriage, even as he mourned the loss of Oliver Loving, his partner. It discusses relationships among her Dyer brothers and other family members; Native Americans, and specifically Quanah Parker; the couple’s unsuccessful business adventures in Pueblo, Colorado; their forced move to free grass in the Palo Duro Canyon, where Mary first heard the cries of orphan bison calves. More business disappointments resulted in a new move to a site above the Palo Duro Canyon, where the historic Charles and Mary Ann Goodnight Ranch House stands today. Thus, the biography reveals a story of successes offset by failures, borne out of a marriage between two distinctly opposite personalities. Though Charles Goodnight famously said that he was never lost and needed no compass, clearly Mary Ann Goodnight became his lodestone.

Meanwhile, Mary’s bison continued to flourish, now at the new Goodnight Ranch situated on a mesa overlooking the Palo Duro Canyon in Armstrong County, Texas. From the beginning, Mary’s concern was for her bison, while her husband ventured toward novel ways to market them, at the same time reducing his cattle operation. Obviously, the Old West had transformed into a New West. Mary began working toward the establishment of a national park to home them, and when those attempts failed, she later campaigned for a state park.

Much like Buffalo Bill, Charles Goodnight took advantage of America’s new fascination with the romance of the Old West and its accompanying guilt for the destruction of the bison and the Native American‘s way of life. Three attempts at making movies—two for Hollywood—and his and second wife Corinne Goodnight’s later memoir project illustrate this.

Mary continued her philanthropy despite her husband’s various risky business ventures. She taught the first school on the Goodnight Ranch; and, along with Charles, financed the creation and support of Goodnight College. She helped found an orphanage and financed yet another new church as the new town of Goodnight (an unincorporated community in the Texas Panhandle today) grew. The cowboys on the JA Ranch and later at the Goodnight Ranch were expected to go to church, even if the service was held in a cabin or outdoors, and single men were expected to eat at her table in the main ranch house so that they would be well fed. Barefoot children were provided shoes and local families received turkeys at Christmas.

Mary was energetic, one contemporary writer calling her “elfish” in her quickness and appearance. She loved to entertain and hosted parties for the college students from Goodnight. She played her piano, donned Charles’s hat with pink chiffon wrapped around the crown, and played with her nieces and nephews. “Aunt Mary” became a favorite within her home, on the ranch, and in town.

Despite several family members’ untimely deaths, Mary made certain that survivors had income and supplied cattle from her own herd to help their finances. She gave advice on raising and selling cattle, including to her nine-year-old nephew, Samuel G. Dyer, Jr..

Charles once expressed his fear of being on the ‘brink of ruin” and he did, indeed, live his life this way until his death. Yet, over half a century, Mary Ann Goodnight provided stability, yanking him back to solid ground repeatedly. Readers will discover that theirs (the Goodnight’s) was a love story, and after Mary died, Charles Goodnight hung up his Mexican silver rowel spurs. He became despondent and “lost” after her death, which caused him to make some hasty decisions that left him living in a ranch house he did not own anymore.

Though Charles always spoke warmly of his wife, her role in his successes is easily overshadowed by the extraordinary early adventures that he experienced and which Haley describes in detail and often in Goodnight’s words. Clearly, Charles, late in his own life, was fully aware of the legacy he wanted to leave.

By the time Charles Goodnight, aged ninety-three, began dictating various “essays” for Haley in 1929, he was remarried to a new, ambitious Mrs. Goodnight, aged twenty-eight. Corinne Goodnight typed Goodnight’s papers and together they first worked to get their own book on Charles’s adventures published before eventually coming to an agreement with J. Evetts Haley. Haley contracted with Charles, promising the Goodnights one-third royalties of Charles Goodnight, Cowman and Plainsman.

It is no surprise that Mary was almost erased from history, her personal effects and letters disappearing from the old ranch house, leaving future Mary Ann Goodnight researchers at a disadvantage.

In the decades since Mary’s and Charles’s deaths, Americans—and Texans, in particular—nourished myths about the Goodnights as Charles Goodnight became an American icon in Western lore and on the big screen (think Lonesome Dove). Only recently has Mary’s prominent role in saving America’s southern bison herd become better known.

I’m pleased to say that Mary Ann Goodnight’s biography reveals much added information, and I am gratified to make my own contribution to the deep pool of Texas history. Though The Breath of a Buffalo will likely not be released until 2026, I am available to speak on Mary Ann Goodnight to interested groups.

The post I Accepted a Challenge: Researching and Writing Mary Ann Goodnight’s Story appeared first on Jane Little Botkin.

I Accepted a Challenge: Researching and Writing Mary Ann Goodnight’s Story.

During a visit to the Charles and Mary Ann Goodnight Ranch House Museum several years ago, I inquired if there were any books on Mary Ann Goodnight. The docent in charge quipped, “No one has written a biography on Molly Goodnight, and besides, there is only a smidgeon of information!” Then she squeezed her index finger and thumb together, not realizing that her response to me would become a years-long challenge.

Mary’s story has never been told, though it was she, not her famous husband, whose continuing actions preserved the Southern American Bison herd from extinction. Charles Goodnight ordered the extermination of the 15,000 bison within Palo Duro Canyon, Texas, in late 1877.

Several authors previously produced biographies on Charles Goodnight, including the most successful and accurate telling by J. Evetts Haley, a classic in western history and especially Texas history. In J. Evetts Haley’s Charles Goodnight, Cowman and Plainsman (1936), now a University of Oklahoma Press property, Mary Ann Goodnight’s portrait is sketched, albeit marginally. Not surprising if one considers the decade in which Haley’s famous biography was written. Biopics of women were uncommon, and, besides, Charles Goodnight’s interview answers and essays for Haley focused mostly on anecdotal information and his well-known accomplishments on cattle trails and with the Texas Rangers—historically, masculine endeavors.

For today’s western history lovers and serious historians alike, Haley’s biography enthralls while significantly contributing to the deep pool of recorded Texas history. Though in his early life Goodnight abhorred attention and adulation, his elder voice, slightly self-aggrandizing at times, colorfully repeats the same tales that tantalized those who once sat around the famous Goodnight dining table—right down to his capturing orphan bison calves that would eventually renew the American southern bison herd.

Haley only witnessed a shadow of Mary Ann Goodnight in 1925, a woman suffering from late-stage dementia, her obsession with saving the bison and charitable endeavors hidden from his first interviews with the old man at the Goodnight Ranch. Within Haley’s biography, Mary’s only mention relating to the origins of the famous Goodnight herd is that she had been “distressed by the slaughter” of 1878—Charles Goodnight’s words. But for me, a 21st century researcher, Charles Goodnight’s deliberate omissions to J. Evetts Haley clearly stand out and will be remedied within my upcoming biography on Mary Ann Goodnight—The Breath of a Buffalo.

Despite the Goodnights’ diverse philosophical views—beginning with saving four bison calves—their marriage was a fifty-six-year partnership in business enterprises, educational endeavors, and community service. Research also reveals a life-long love story between a prickly, illiterate, and foul-mouthed trail driver and a fun-loving but refined, petite schoolteacher who respected each other’s differences and shortcomings.

To understand how the Goodnights’ personal relationship evolved, this biography will scrutinize Mary’s life, beginning with her roots in Dyer County, Tennessee; her family’s move to Texas because of a pledge to Senator Sam Houston; and the chaotic setting that was northeast Texas before and after the Civil War. The narrative follows Mary when she gave Charles Goodnight an ultimatum demanding marriage, even as he mourned the loss of Oliver Loving, his partner. It discusses relationships among her Dyer brothers and other family members; American Indians, and specifically Quanah Parker; the couple’s unsuccessful business adventures in Pueblo, Colorado; their forced move to free grass in the Palo Duro Canyon, where Mary first heard the cries of orphan bison calves. More business disappointments resulted in a new move to a site above the Palo Duro Canyon, where the historic Charles and Mary Ann Goodnight Ranch House stands today. Thus, the biography reveals a story of successes offset by failures, borne out of a marriage between two distinctly opposite personalities. Though Charles Goodnight famously said that he was never lost and needed no compass, clearly Mary Ann Goodnight became his lodestone.

Meanwhile, Mary’s bison continued to flourish, now at the new Goodnight Ranch situated on a mesa overlooking the Palo Duro Canyon in Armstrong County, Texas. From the beginning, Mary’s concern was for her bison, while her husband ventured toward novel ways to market them, at the same time reducing his cattle operation. Obviously, the Old West had transformed into a New West. Mary began working toward the establishment of a national park to home them, and when those attempts failed, she later campaigned for a state park.

Much like Buffalo Bill, Charles Goodnight took advantage of America’s new fascination with the romance of the Old West and its accompanying guilt for the destruction of the bison and the Native American‘s way of life. Three attempts at making movies—two for Hollywood—and his and second wife Corinne Goodnight’s later memoir project illustrate this.

Mary continued her philanthropy despite her husband’s various risky business ventures. She taught the first school on the Goodnight Ranch; and, along with Charles, financed the creation and support of Goodnight College. She helped found an orphanage and financed yet another new church as the new town of Goodnight (an unincorporated community in the Texas Panhandle today) grew. The cowboys on the JA Ranch and later at the Goodnight Ranch were expected to go to church, even if the service was held in a cabin or outdoors, and single men were expected to eat at her table in the main ranch house so that they would be well fed. Barefoot children were provided shoes and local families received turkeys at Christmas.

Mary was energetic, one contemporary writer calling her “elfish” in her quickness and appearance. She loved to entertain and hosted parties for the college students from Goodnight. She played her piano, donned Charles’s hat with pink chiffon wrapped around the crown, and played with her nieces and nephews. “Aunt Mary” became a favorite within her home, on the ranch, and in town.

Despite several family members’ untimely deaths, Mary made certain that survivors had income and supplied cattle from her own herd to help their finances. She gave advice on raising and selling cattle, including to her nine-year-old nephew, Samuel G. Dyer, Jr..

Charles once expressed his fear of being on the ‘brink of ruin” and he did, indeed, live his life this way until his death. Yet, over half a century, Mary Ann Goodnight provided stability, yanking him back to solid ground repeatedly. Readers will discover that theirs (the Goodnight’s) was a love story, and after Mary died, Charles Goodnight hung up his Mexican silver rowel spurs. He became despondent and “lost” after her death, which caused him to make some hasty decisions that left him living in a ranch house he did not own anymore.

Though Charles always spoke warmly of his wife, her role in his successes is easily overshadowed by the extraordinary early adventures that he experienced and which Haley describes in detail and often in Goodnight’s words. Clearly, Charles, late in his own life, was fully aware of the legacy he wanted to leave.

By the time Charles Goodnight, aged ninety-three, began dictating various “essays” for Haley in 1929, he was remarried to a new, ambitious Mrs. Goodnight, aged twenty-eight. Corinne Goodnight typed Goodnight’s papers and together they first worked to get their own book on Charles’s adventures published before eventually coming to an agreement with J. Evetts Haley. Haley contracted with Charles, promising the Goodnights one-third royalties of Charles Goodnight, Cowman and Plainsman.

It is no surprise that Mary was almost erased from history, her personal effects and letters disappearing from the old ranch house, leaving future Mary Ann Goodnight researchers at a disadvantage.

In the decades since Mary’s and Charles’s deaths, Americans—and Texans, in particular—nourished myths about the Goodnights as Charles Goodnight became an American icon in Western lore and on the big screen (think Lonesome Dove). Only recently has Mary’s prominent role in saving America’s southern bison herd become better known.

I’m pleased to say that Mary Ann Goodnight’s biography reveals much added information, and I am gratified to make my own contribution to the deep pool of Texas history.

The post I Accepted a Challenge: Researching and Writing Mary Ann Goodnight’s Story. appeared first on Jane Little Botkin.

September 3, 2023

Phyllis George, the Girl-Next-Door Who Became Miss America

It was her dimples that first drew my attention to the Miss America pageant. A more-than-passable piano player with wholesome beauty, Phyllis George could have been anyone’s big sister or babysitter. I watched the pageant every September along with my parents. Before Phyllis, we knew almost nothing about the contestants parading in pale rainbows of chiffon gowns in front of the camera. Only where they were from and how they looked. We waited for emcee Bob Barker to call out our Miss Texas and hoped that she appeared as exotic and glamorous as Miss New York or as golden-skinned and blonde as Miss California.

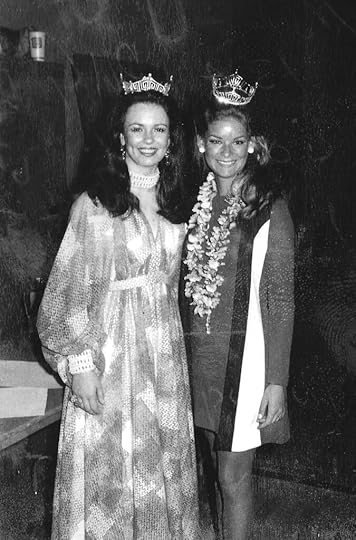

Miss America 1971 Phyllis George (left) with Miss El Paso 1971 Janie Little (Botkin)

Usually, we were not disappointed, and having our state in the mix made a family competition that much more fun. Together, we dissected swimsuit competition, evening gowns, and interviews. The real entertainment was the talent segment, counting for most of the judges’ scoring. Watching Miss America was akin to watching a variety show, much like Andy Williams, Ed Sullivan, or Carol Burnett. When Phyllis George won the Miss Texas pageant in 1970, watching the Miss America pageant became a more intimate experience. We felt like we knew Phyllis.

In spring 1971, a poster appeared on my college campus. “WANTED! You Could Be Miss America!” the words proclaimed in black and white above and below the beaming face of Phyllis George, Miss America 1971. She was then America’s girl-next-door, her dark, glossy lips in a dimpled smile revealing perfect white teeth. This poster drew me into the Miss America pageant franchise. Later Phyllis and I became friends, not intimate, but close enough that she knew my personal difficulties and quizzed me about my happiness. When I look back to my personal history with Phyllis, I realize she is the only other woman with whom my husband ever agreed to dance. How could he turn down Miss America? Yes, she had asked him.

Phyllis George’s reign amid turmoil

Phyllis’s reign, often amid American turmoil, seems extraordinary, though in retrospect, other Miss Americas surely dealt with unusual world events during their title years. Beginning with women’s liberation movement protestors in front of Atlantic City’s Miss America pageant venue in September 1970, the country appeared upended. The Viet Nam war; college unrest; prison revolts; Weatherman bombings; Cold War; and space race framed her whirlwind year. Phyllis even traveled to Viet Nam, part of a 22-day USO tour. Alongside comedian Bob Hope and other beauty queens, she helped entertain troops.

Often, Phyllis performed her piano piece, “Raindrops Keep Falling on My Head,” from the popular Butch Cassidy and Sundance Kid movie. She would stumble over the keys, frown, restart the piece, frown again, and then look at the audience, smile those amazing dimples, and charge into the music perfectly. She was an entertainer at heart.

Resistance from an all-male cast of chara cters

As if in tune with the revolution around her, Phyllis cracked the glass ceiling in the sports entertainment world. After a short stint co-hosting Candid Camera on television, CBS Sports hired her as a human-interest reporter and commentator, her most prominent gig on “The NFL Today.” Immediately, Phyllis faced resistance from an all-male cast of characters.

On the weekly pregame football show, featuring co-hosts Brent Musburger, Irvin Cross, and Jimmy “the Greek” Snyder, Phyllis received criticism. What in the hell did she know about sports? Phyllis responded that she knew “enough”! Her answer, “I’m from Texas and down there you follow the Texas Longhorns and the Dallas Cowboys, or you don’t belong.” She told People Magazine, “When I pick up the morning paper, the sports pages come first, and the fashion pages come last.”

Despite Jimmy the Greek’s relentless criticism of her, Phyllis became famous for her interviews with athletes. Still, during commercial breaks, while putting up with sexist remarks, she bravely offered ideas for the show. Phyllis remained with The NFL Today show until 1978, when her first marriage to movie Hollywood producer Robert Evans fell apart. They had only been married one year. Another beauty queen, Miss USA “top ten” finalist and stunning African American Jayne Kennedy took her place.

It’s all about the Texas do-over (El Paso do-over in my case), as readers will find in The Pink Dress, Memoir of a Reluctant Beauty Queen. Phyllis got hers in 1979 when she married again. This time to John Brown, who was elected governor of Kentucky the same year. Phyllis had a new role to play as first lady of the state for the next four years. She also returned to “The NFL Today” in 1980, staying until 1984.

Winning the Miss America 1971 title “was the springboard to everything I’ve done in my life.”

Phyllis never stopped expanding her experiences. After anchoring “The CBS Morning News” where she endured more criticism about her lack of journalistic background, she raised two children; acted in small movie roles; and hosted a talk show on the Nashville Network. She wrote five books, including one about diets (I can relate!) and one with an intriguing title, Never Say Never. She began two businesses, Chicken by George, which she later sold to Hormel, and a cosmetic and skin-care line, Phyllis George Beauty. Phyllis told a reporter from Texas Monthly in 2007 that winning the Miss America 1971 title “was the springboard to everything I’ve done in my life.”

It took me decades to realize that when Phyllis performed her Miss America pageant piano piece, “Raindrops Keep Falling on My Head,” she had a shtick—the deliberate errant notes. To cover for any accidental mistakes she might make, she had learned to make a joke out of any difficulty and proceed on as if nothing had happened. Everyone would think the mistake was part of her act. In much the same way, Phyllis had lived her life with the same attitude.

Her legacy

Phyllis George’s death of polycythemia vera in 2020 shocked the world. She had been diagnosed with the rare blood cancer when she was only thirty-five (1985) and kept the diagnosis a secret. All the while, Phyllis had showed the world that women could break the 1970s-1980s male bastion in sports entertainment. Soon after, increasing numbers of women gained wide respect at various networks. Her legacy? Phyllis George, facing private tragedy with a dimpled public smile and spirit, had led others to follow her path.

The post Phyllis George, the Girl-Next-Door Who Became Miss America appeared first on Jane Little Botkin.

Phyllis George, 50th Miss America and Girl Next Door

It was Phyllis George’s dimples that first drew my attention to the Miss America pageant. A more-than-passable piano player with wholesome beauty, she could have been anyone’s big sister or babysitter. Though I watched the pageant every September along with my parents, before Phyllis, we knew almost nothing about the contestants parading in pale rainbows of chiffon gowns in front of the camera. Only where they were from and how they looked. We waited for emcee Bob Barker to call out our Miss Texas and hoped that she appeared as exotic and glamorous as Miss New York or as golden-skinned and blonde as Miss California. Usually, we were not disappointed, and having our state in the mix made a family competition that much more fun.

Together, we dissected swimsuit competition, evening gowns, and interviews. We waited for emcee Bob Barker to call out our Miss Texas and hoped that she appeared as exotic and glamorous as Miss New York or as golden-skinned and blonde as Miss California. Usually, we were not disappointed, and having our state in the mix made a family competition that much more fun.

But the real entertainment was the talent segment, counting for most of the judges’ scoring. Watching Miss America was akin to watching a variety show, much like Andy Williams, Ed Sullivan, or Carol Burnett. It was a time when my parents seemed happy together as they joined in laughing at skits, interview answers, and even mishaps. When Miss Texas Phyllis George won the national pageant in 1970, watching the Miss America pageant became a more intimate experience. We felt like we knew Phyllis.

“WANTED! You Could Be Miss America!” words proclaimed in black and white above and below the beaming face of Phyllis George, Miss America 1971. Phyllis was America’s girl next door, her dark, glossy lips in a dimpled smile revealing perfect white teeth. Because of Phyllis George’s poster, I was drawn into the Miss America pageant franchise. Later we became friends, not intimate, but close enough that she knew my personal difficulties and questioned my happiness. Later she would have similar experiences herself. When I look back in my personal history with Phyllis, I realize she is the only other woman with whom my husband ever agreed to dance. How could he turn down Miss America? Yes, she asked him.

Her reign amid American turmoil seems singular to me, though in retrospect, other Miss America’s surely dealt with unusual world events during their title years. Beginning with women’s liberation movement protestors in front of the Miss America pageant venue in September 1970 when she won the crown, the Viet Nam war; college unrest; prison revolts; Weatherman bombings; the Cold War; and space race framed her whirlwind year as America’s queen. She even traveled to Viet Nam, included on a 22-day USO tour, where alongside comedian Bob Hope and other beauty queens, she helped entertain troops.

Often, she performed her piano piece, “Raindrops Keep Falling on My Head,” from the popular Butch Cassidy and Sundance Kid movie. She would stumble over the keys, frown, restart the piece, frown again, and then look at the audience, smile those amazing dimples, and charge into the music perfectly. She was an entertainer at heart.

As if in tune with the revolution around her, it was Phyllis who cracked the glass ceiling in the sports entertainment world. After a short stint co-hosting Candid Camera on television, CBS Sports hired her as a human-interest reporter and commentator, her most prominent gig on “The NFL Today.” Immediately, Phyllis faced resistance from an all-male cast of characters.

On the weekly pregame football show, featuring co-hosts Brent Musburger, Irvin Cross, and Jimmy the Greek (Jimmy Snyder), Phyllis instantly received criticism. What in the h___ did she know about sports? Phyllis’s answer, “I’m from Texas and down there you follow the Texas Longhorns and the Dallas Cowboys, or you don’t belong.” She told People Magazine, “When I pick up the morning paper, the sports pages come first, and the fashion pages come last.” Phyllis responded that she knew “enough” about sports!

Despite Jimmy the Greek’s relentless criticism of her, Phyllis became famous for her interviews with athletes. Still, during commercial breaks, while putting up with sexist remarks, she bravely offered ideas for the show. Phyllis remained with The NFL Today show until 1978, when her first marriage to movie Hollywood producer Robert Evens fell apart. They had only been married one year. Another beauty queen, Miss USA “top ten” finalist and stunning African American Jayne Kennedy took her place.

It’s all about the Texas do-over (El Paso do-over in my case), as readers will find in The Pink Dress, Memoir of a Reluctant Beauty Queen. Phyllis got hers in 1979 when she married again. This time to John Brown, who was elected governor of Kentucky the same year. Phyllis had a new role to play as first lady of the state for the next four years. She also returned to “The NFL Today” in 1980, staying until 1984.

But Phyllis never stopped expanding her experiences. After a short stint as anchor of “The CBS Morning News,” enduring more criticism that she lacked formal journalism background, she gave birth to two children; acted in several small movie roles; and hosted a talk show on the Nashville Network. She wrote five books, including one about diets (I can relate!) and one with an intriguing title Never Say Never. She began two businesses, Chicken by George, which she later sold to Hormel, and a cosmetic and skin-care line, Phyllis George Beauty. Phyllis told a reporter from Texas Monthly in 2007 that winning the Miss America title in 1971, “was the springboard to everything I’ve done in my life.”

It took me decades to realize that when Phyllis had performed her Miss America piano piece, “Raindrops Keep Dropping on My Head,” she had a shtick—the errant notes. To cover for any accidental mistakes she might make, she had learned to make a joke out of the small difficulty and proceed on as if nothing had happened. Everyone would think the mistake was part of her act. In much the same way, Phyllis had lived her life with the same attitude.

When Phyllis George died of polycythemia vera in 2020, the world was shocked. She had been diagnosed with the rare blood cancer with she was only thirty-five (1985) and kept the diagnosis a secret. All the while, Phyllis had showed the world that women could break the male bastion of the 1970s and 1980s in sports entertainment. Soon after, increasing numbers of women gained wide respect at various networks. Her legacy? Phyllis George, facing personal tragedy with a public dimpled smile and spirit, had led others to follow her path.

The post Phyllis George, 50th Miss America and Girl Next Door appeared first on Jane Little Botkin.

October 3, 2022

Los Lagartos Fountain, What Happened to the San Jacinto Alligators?

(Photo El Paso Historical Society)

Recently I returned to El Paso to visit my past—my classmates, Northeast El Paso’s Milagro Hills where I grew up, the Upper Valley where I last lived in the city, and, of course, Guyrex landmarks important to my newest book, The Pink Dress, Memoir of a Guyrex Girl.

A pleasant surprise was my residence during this journey down memory lane, a trip I shared with childhood friends. Together we stayed in the penthouse rooms on top of El Paso’s historic, art-deco Plaza Hotel (the Hilton, 1929), supposedly in the rooms that Nicky Hilton’s young wife Elizabeth Taylor occupied.

That was a novelty, but so was discovering members of the Scorpions, a rock band from the last century (see, I am showing my age!) who were performing at UTEP on one night of our stay. Their rooms were six floors below ours. A man, wearing a Scorpions t-shirt and bushy hair flowing sideways and down his back, politely exchanged places with us on an elevator. I snidely commented to my friends that an old rocker had shown up to attend the Scorpians’ concert. Little did I know, the fellow with grizzled hair was their drummer Mikkey Dees.

Below our 17th floor rooms, my friends and I could see historic landmarks from our past. There stood the Plaza Theater (1930) where, instead of sitting below the starry night-sky garden, we had sat under a balcony, so kids from rival high schools couldn’t spit on us from above. In front of our wine-colored, velveteen seats, our choir teacher Richard Hawley performed before weekend matinees on a grand Wurlitzer organ that arose from an orchestra pit in front of the stage.

There was also the Mills Building (1911), a renowned architect Henry Trost design where the White House Department Store once occupied. My girlfriends and I reminisced the times we saved up to shop in the downtown store known for high-end clothing. A few of us were fortunate to get jobs there, which meant discounted clothes sales.

But it was what was across the street from the Plaza Hotel, Plaza Theater, and Mills Building that brought back memories, tinged with smells, sights, and sounds that flashed across my brain. San Jacinto Plaza.

Most southwest, Spanish-colonial towns and cities began with a plaza, often near a church. And this would be true for El Paso’s sister city Juárez, with its missions and churches. Perhaps because of the Mexican city’s earlier birth (1659) as El Paso del Norte on the south side of the Rio Grande, and El Paso’s later established recognition on the north side of the river after the Treaty of Hidalgo (1848), a main plaza was delayed in its construction. But I’m just theorizing.

The Sheldon Hotel burned down in 1929, and the Hilton Hotel (Plaza Hotel) was built on its site. Photo El Paso Historical Society

The Sheldon Hotel burned down in 1929, and the Hilton Hotel (Plaza Hotel) was built on its site. Photo El Paso Historical SocietyWhat I do know is that in 1881, two acres were purchased to be used as a bona fide town square, framed by Mills, Oregon, Main, and Mesa streets. By 1882, a new plaza offered an open area in the middle with sidewalks, trees and benches spreading out from the center. The plaza earned its unique name in 1889, when in the middle of a sundial design at its center, an alligator pond was added. El Pasoans now called the plaza—La Plaza de Los Lagartos or Alligator Park.

No, though alligators occupy much of the south, east, and even central parts of Texas, they are not native to the high desert of El Paso! The first alligator came from Louisiana. In March 1889, a plaza park manager announced to El Paso papers that he was expecting a baby alligator to arrive soon. When the reptile arrived four months later, a crowd of El Pasoans came to see the baby “disport himself in foreign waters.” Soon, more alligators arrived, and they had fans.

The alligators became the central attraction at San Jacinto Plaza, the plaza renamed in 1903 after a famous battle for Texas independence from Mexico. Early visitors would rest on the wall surrounding the pond, watch the alligators, and chat about the day’s current events. On occasion, troops paraded around the square, artists exhibited their paintings, and holiday festivities abounded. The reptiles quickly became a staple of El Paso culture. At one time the pond contained seven alligators.

An online newspaper search reveals that in late summer 1952, Minnie, a 59-year-old female alligator, laid a total of three eggs aside the pond. Spectators were delighted when they saw the protective mother-alligator spring to life and lunge toward park employees who were cleaning the pond. The eggs never hatched.

Also in 1952, pranksters left a 10-foot San Jacinto Plaza alligator named Oscar inside Texas Western College (now UTEP) geology Professor Howard Quinn’s office. It thrashed around, damaging office furniture, “showing no sympathy for higher education.” A park commissioner stated, “Oscar went to college but he flunked out. Guess he was too old to learn.” Oscar was 60 years old. Still, newspapers reported that having alligators was said to be more dangerous for the alligators than for the pranksters.

Months later, Oscar was found dead at the bottom of the pond, the result of internal injuries after vandals threw him back into the water. El Pasoan Myrtle Price donated two alligators named Jack and Jill to take Oscar’s place, a pair who arrived in a cigar box, also from Louisiana. These two alligators are likely some of the ones I saw when I was a kid growing up in El Paso. They joined four other alligators, all between 60 and 70 years old.

Another prank occurred in 1956 after college students dumped another San Jacinto Plaza alligator into the Texas Western College swimming pool, right before an intramural swim meet. The park department advisor this time quipped, “It’s almost an annual occurrence. In another year or so, those alligators will know their own way home!”

Sally, one of the first alligators placed in the pond, was the object of a weight-guessing contest in 1958. The El Paso Herald Post shared that Sally was 8-feet-8-inches long, causing a flurry of letters to reach alligator experts across the country. Contenders for a $100 prize and a round-trip to Mexico City asked for scientific opinions regarding the reptile’s possible weight. One alligator expert refused to respond to the letters, saying, “Alligators are like people. Some are fat and some are thin. Some are hard and tough, and some soft and blubbery.”

Other competitors tried to make assessments on their own. To help them in their weight estimates, park officials painted a pink arrow on Sally’s head to help single her out from her pond-mates. Complicating people’s guesses, however, was the fact that Sally temporarily gained ten pounds immediately after feeding on ten pounds of horse meat. After a month of excitement, one estimator out of 10,000 entries hit Sally’s weight exactly—240 pounds and 2 ounces!

My remembrance of the old plaza is mainly during the 1960s when it was a hub for boarding city buses and taxicabs that had replaced horse-drawn carriages. We retrieved our Mexican maid there each week and returned her to the bus stop at the end of the day. And every time we attended a movie at the Plaza Theater, we begged our parents to first visit the alligators.

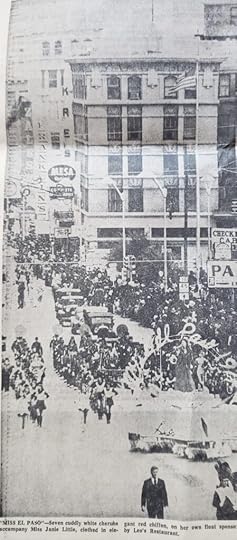

My last memory of the plaza was on a freezing day in January 1972, captured in an El Paso Times’ newspaper photograph. Wearing a three-quarters-length mink coat over my evening gown, I stand atop a Miss El Paso float with a portion of the Sun Carnival Parade on North Mesa Street. A man I hadn’t known took stock of my frozen situation and taking the coat from his wife, tossed it up to me. Behind me looms the five-story Banner Building, also designed by Henry Trost and beyond it, the art-deco Kress building and the Plaza Hotel. But the reader’s eye catches what is behind my float in the photograph—a procession of 1910s and 1920s cars follows, frozen in time, while to my left, crowds throng within San Jacinto Plaza, decked out in Christmas attire

My childhood friends shared their memories. They claimed the alligators smelled, but I don’t recall that sensory memory. My brain is full of sidewalk streetlights, park benches sticky with the day’s brown paper-bag lunches and sugary Mexican Coca Cola, people of all stripes milling around— Juareños and El Pasoans alike—and the pond’s murky surface. My childish curiosity consisted of waiting impatiently to see the alligators stick their gnarled snouts out of the gnat-covered water. When they did, we gleefully searched for any food tidbit to toss at them. This was probably against the rules.

Unfortunately, other passersby hurled rocks at the animals and burned them with cigarettes to get them to move.

The alligators were finally relocated to the El Paso Zoo in 1965 after Chama and Zal—a reference to the Chamizal border agreement—were stoned to death and another had a spike driven through its left eye. The alligators were briefly returned to the plaza in 1972 only to be removed once again in 1974 because of vandals. The pond was permanently removed shortly thereafter.

Today, a commemorative statue of the alligators sits in a central fountain to honor the 80-year history of alligators in the old plaza. Los Lagartos Fountain, Fountain with Alligators.

There are no smells. The water is clean and clear. Not a piece of trash or sticky syrup covers the pavers or new benches in the sterile, modern plaza. My friends and I, though, could remember, imagining the old smells, sights, and sounds of San Jacinto Plaza as we gazed into a new alligator pond with a central sculpture. Reflected in a kaleidoscope of colors, three frozen alligators, struggle to stick their snouts up high, mouths gaped open.

The post Los Lagartos Fountain, What Happened to the San Jacinto Alligators? appeared first on Jane Little Botkin.

July 1, 2021

El Paso, the World of Guyrex

Some folks claim that El Paso, Texas, should be El Paso, New Mexico. It’s true that the city sits in isolation from the rest of the state—635 miles from Dallas, 600 miles from Austin, and 551 miles from San Antonio. These same naysayers maintain that Midland, 306 miles away, is West Texas, not El Paso. To other visitors, the city, with its sprawl around the southern tip of the Franklin Mountain on the Mexico-United States border, seems more like a foreign country. The Mexican state capitol of Chihuahua is only 239 miles from El Paso.