Paul Cunningham's Blog

November 15, 2025

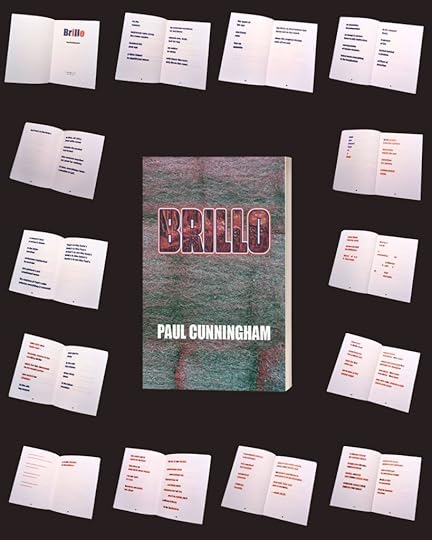

Happy Pub Day to ‘Brillo’! Now available from Lavender Ink Press!

Photo credit: Kalie Pead and Rebecca Greenes Gearhart

Photo credit: Kalie Pead and Rebecca Greenes Gearhart

Happy publication day to Brillo (now available from Lavender Ink). Endless gratitude to Sean F. Munro and Bill Lavender for manufacturing and distributing this holy box of flesh and bones. Grateful thanks also goes to the following brilliant poets for their generous responses to Brillo:

Paul Cunningham threshes the rim between Warhol’s shallow surface and Paul Thek’s “viscous interiority.” The brand-names (Thek, Warhol, Brillo) are re-pressed, re-touched, and un-boxed as art history unfolds through the gaze of a “worm-like eye. […] Cunningham decrypts the cubes, only to uncover a “flesh of code” and a “cryptography of open pores” that cannot be wormed through. The cubes align in a cabinet of curiosities that becomes Cunningham’s own memento mori. Will the void made flesh become spirit? Or will we all rot away in self-consumption…

— Felix Bernstein, author of Notes on Post-Conceptual Poetry

Paul Cunningham’s Brillo is not unlike the living presence of what is sourced by concrete poetry. Its living energy and visual identity traces back to Apollinare’s Calligrammes and the Brazilian heritage that stems from the modern Manifesto sired by Augusto de Campos.

— Will Alexander, author of Divine Blue Light

Echoing Jesus—“Eat, this is my body”—the book offers itself as object and offering. In the spirit of Sontag’s Camp—“its love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration”—Brillo becomes its own spectacle. “The box is blank but branded. Like me.” Beautiful, brutal, and impossible to look away from, it performs its own undoing.

— Valerie Mejer Caso, author of Rain of the Future

Less an ekphrastic exercise than ecstatic experience, Brillo is the transgressive account of one Paul possessing another, as a demon is said to possess a human body. This poem is a panoptical shadowbox, a butcher’s “artifact of / devotion,” in which Cunningham shadowboxes Thek, who’d visited the Palermo catacombs before wadding War-hole’s carton with viscera. Each page is a screen-printed poster

— Andrew Zawacki, author of Unsun

October 30, 2025

A Review of Aodhán Ridenour’s “Little Bit Weird” CHAPBOOK (Bottlecap Press, 2025)

Here are poems with a confessional directness reminiscent of the “speak now or forever hold your tongue” approach to poetry explored in Jack Kerouac’s Desolation Angels. In the acknowledgments of Little Bit Weird, Aodhán Ridenour writes, “I hardly wrote any of these poems.” With a youthful Beat sensibility, Ridenour’s mind, in the act of composing, channels what Denise Levertov calls the “organic” or what Charles Olson designates as “projective.” In “Projective Verse,” Olson likens a poem to a “kinetic” assemblage, or, an energy obtained from some external source. He also offers a kind of equation for projective verse: “the HEAD, by way of the EAR, to the SYLLABLE / the HEART, by way of the BREATH, to the LINE.” A similar kind of projective, self-conscious unfolding takes place in many of Ridenour’s poems—especially in “Black Pepper”: “I made sixteen mistakes today, / give or take, / and yet I sit here happilly, / inhaling her black pepper, / hapilly misspelled.” True, the word “happily” is intentionally misspelled twice in this poem, but the adjective could also be describing the “I” of this poem. A self misspelled (or scrambled) by desire (“my happiness, / the commencement of / my emptiness”).

The weirdness of the love poems of Little Bit Weird rests in Ridenour’s use of mythical and nautical language (“Its bow and stern / must bend to touch the edges of our bodies”), kinetic instant-by-instant self-transcendence (“Yet I have held my tongue, / a petal from the flowers in my head”) and a desire for communication in a tech-choked world (“I simply need to find another / Wi-fi mic-radio wave / to reach my antenna / in lieu of my attempts / to share my GHz with you.” From WhatsApp to Tinder to ChatGPT, Little Bit Weird is more than love poems, it’s a portrait of a writer in 2025: the way “fingers slide across the screen.” For fans of John Yau’s Borrowed Love Poems or Zachary Schomburg’s Fjords volumes.

Slippery Rock University Keynote Reading: Celebrating the 20th Issue of SLAB

I returned to my alma mater this past weekend to read from my new book, Brillo (now available to preorder from Lavender Ink). Slippery Rock University’s English department celebrated the release of the 20th issue of SLAB (Sound and Literary Arts Book) and there was a pretty impressive Halloween costume party.

SLAB is currently reading submissions of fiction, creative nonfiction, poetry, and text-based graphic art. Deadline: April 15th.

October 10, 2025

‘Ancient Algorithms’ is now available for purchase; ‘Brillo’ is available to preorder

“Katrine Øgaard Jensen and her collaborators engage in transritual and transcreation as acts of writing—transwriting. Their varied triggers and processes are spectacular. Ancient Algorithms reveals immense possibilities of language and poetry to become fearless and unbordered.”

— Don Mee Choi, author of Mirror Nation

I’m very pleased to announce I’m one of the poet collaborators in Katrine’s remarkable new book from Sarabande Books! Ancient Algorithms is a series of mistranslations and remixes of her award-winning translations of Danish poet Ursula Andkjær Olsen’s poetry trilogy (published by Action Books). Through deliberate obstructions and self-imposed rules, Katrine and I re-interpreted and rewrote her mistranslations of Olsen’s My Jewel Box.

I feel incredibly grateful to Katrine for having invited me to be a part of this extraordinary experimental translation project with so many translators and friends whom I greatly admire: CA Conrad, Sawako Nakayasu, Aditi Machado, Baba Badji, and Ursula Andkjær Olsen herself!

Here is a brief excerpt:

now we enter

my new growth stage

the stage is a stage

[I join the cast as Katrine]

I am no Katrine-doll

I am no doll, I am Katrine

a row of relation

familiar exterior relations

i.e. Paul has taken all the relations

and the situations of place

and entered the person concerned

only to repeat the entire scene

new interiority

This book is like Lars Von Trier’s The Five Obstructions — but for translators of poetry!

My fourth full-length book of poetry — Brillo — is also now available to preorder from Lavender Ink Press. “Brillo-shaped / block / fragment / of life / locked behind / a window / artifact of devotion” What does it mean to “see the old face in the altered one”? Taking my cues from Wittgenstein’s concept of ‘seeing-in,’ Brillo is more than a poet’s meditation on Paul Thek’s 1965 “Meat Piece with Warhol Brillo Box,” it’s a perception-expanding experiment that challenges readers to become spectators—to visualize poet as painter. Just as Thek signed his letters to his friend Susan Sontag as “Vincent” (after Van Gogh), I navigate the psychology of advertising, leaving a different kind of signature on a box of—a book of—questions concerning the art market, the meatpacking industry, mechanical reproduction, visual modernity, and Catholicism. Brillo might not be the answer to the (sin)ewy riddle oozing inside Thek’s pop art reliquary, but, like the knife-sharp clouds of Buñuel’s Un Chien Andalou, this box/book might force you to look in directions you’ve never dared to before. As Andy Warhol once said: “Art is what you can get away with.”

Learn more about Brillo [here]. Watch the official book trailer below:

August 13, 2025

“Spittle is the very symbol of the formless [informe]” TWo new poems published in Burning house press online

“Spittle is the very symbol of the formless [informe], of the unverifiable, of the non-symbol of the non-hierarchized”

— Michel Leiris, translated by Dominic Faccini

Can’t thank guest editor M. Forajter enough for publishing two of my poems (“To Lift” and “Night Shift“) in this sprawling and unspeakably sublime “Art & Annihilation” issue of Burning House Press Online. So many kindred spirits are here, too!

I’m also grateful that Burning House Press remains a stronghold for fearless and defiant writers during what feels like increasingly conservative times. Lately, too much of the surrounding litscape feels like a bunch of journals that are in the business of publishing excruciatingly personal third-person bios, not poems.

I’m so glad this house continues to burn!

July 31, 2025

Two new poems published in The indianapolis review

Here’s some ekphrasis I fashioned for The Indianapolis Review — “Something to Be Proudly Worn Into Heaven” — a response to an insect-flecked necklace (Schiaparelli, fall/winter 1938-39) and Joyelle McSweeney’s essay “Bug Time: Chitinous Necropastoral Hypertime against the Future“:

worn with the mnemonic sensation

of a weathered beetle’s precious metal

call it a resurrection strategy

something to be proudly worn into Heaven

memory after memory

we bleed only to catch the time

autocatalytic degradation

another neckline frozen in time

A second poem, “Cipher,” was inspired by a dress of glittering swarms designed by the late creative director of Lanvin, Alber Elbaz, who once said: “we can’t control nature — we are part of it”

survived by every dark green dragonfl-

ight every cruel legislation vib-

rating stinging diamonding pearl-

ing baubles blue swarms of possibility

designing bodies anew

These are two poems from a larger collection called Worn, my 70+ poem response to garments and pieces that appeared in Andrew Bolton’s 2024 exhibition, Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion.

Many, many thanks to Natalie Solmer for publishing these poems!

July 10, 2025

I’m Reading at the fuzzy needle Tomorrow (7/11) in durham, north carolina

Tomorrow (July 11)! I’ll be reading in Durham, NC with Ellen Boyette, Nathan Dixon, and Laura Jaramillo at The Fuzzy Needle Records & Books! Hope to see you there!

Ellen Boyette is a poet and essayist whose work is interested in the occult, the internet, and objects real or imagined. She received her MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. She is a Pushcart Prize nominee, Best of the Net nominee, and an Academy of American Poets College Prize recipient. She is the author of two chapbooks and has work featured in Poetry Daily, poets.org, The Columbia Review, The Iowa Review, jubilat, The Bennington Review, Prelude, and elsewhere.

Nathan Dixon received his PhD in English literature and creative writing from the University of Georgia. His first book, Radical Red, won the BOA Editions short fiction prize. His creative work has appeared in The Georgia Review, Fence, Tin House, Carolina Quarterly, Quarterly West, Redivider, and elsewhere. His critical/academic work has appeared in MELUS Journal, 3:AM, Transmotion, and Renaissance Papers. He currently teaches at North Carolina Central University and lives with his family in Durham, NC.

Laura Jaramillo is a poet and critic. Born to Colombian parents in Queens, New York, she now lives in Durham, North Carolina. Her books include Material Girl (subpress, 2012) and Making Water (Futurepoem, 2022). She holds a PhD in critical theory from Duke University. She co-runs the North Carolina-based reading and performance series Paradiso.

May 11, 2025

Notes on Andrew Felsher’s Notes from a Prison Cell: A Review

“I push through the sleep-like fog

and try running down the corridor

the corridor of a prison that I’ve studied every night

in the bird’s eye-view of my dream

As if the corridors of my body are about to burst

the walls slosh and roll

Like a tomb there’s no emergency exit anywhere

Every day I walk the same corridors that jail me

looking at the things that appear and disappear in the window”

—from Sue Hyon Bae’s translation of Kim Hyesoon’s “My Panopticon, That Bird’s-Eye View” (A Drink of Red Mirror)

Andrew Felsher’s Notes from a Prison Cell (Bottlecap Press, 2023) follows the thoughts and observations of an art installation located on a mountaintop. The art installation is known as “the prison cell” and it exists as its own self-aware entity. Disconnected from both a physical prison and from the unnamed artist who originally made the installation, the prison cell eventually befriends a talking sparrow sensitive to artistic concerns and an opinionated pebble who recently freed itself from its own prison: the hiking boot of a person affiliated with a “prestigious university.”

Reminiscent of a fairy tale, there’s a deliberate flatness to Felsher’s characters that’s essential for inviting readers to contemplate more abstract elements. Why a talking pebble? Why a sparrow who says things like “Wifi is a means to connect”? As Kate Bernheimer reminds us: “flatness allows depth of response in the reader.” There’s a simplicity and rhythm to Felsher’s sentences that permits an existential sense of humor (i.e. “When the artist died, people returned”).

Much of Felsher’s prose explores lack. A lack of connection with people. A lack of self-understanding. And, what feels most pressing: a lack of meaning typically afforded by the presence of an artist’s statement. Since the prison cell exists as a conscious art installation without an artist’s statement, art (for the artist), in many ways, can become its own form of solitary confinement. Institutions can, of course, deeply benefit artists. But what happens when the reverse is true? What happens when an institutions leaves an artist feeling meaningless? In an effort to feel “meaningful,” the prison cell recruits the sparrow to write an artist’s statement using twigs. An excerpt from the first iteration reads:

A PRISON CELL IS NOT A PRISON CELL. IT IS AN EMPTY YEARNING FOR CONTROL. THE ARTIST SEEKS TO JUXTAPOSE NATURE WITH CARCERAL APPARATUSES.

And while this artist’s statement goes through some unexpected edits and revisions, the prison cell’s initial yearning for “control,” might actually be a yearning for the opposite of control: nature. Nature without curation. Nature without human dominion. Perhaps it’s what Anna Tsing brilliantly calls “disturbance” in The Mushroom at the End of the World. When the prison cell becomes too focused on whether it’s meaningful art or not, it becomes less of an art installation and more of a prison cell.

Even though the prison cell is without a panoptic watchtower (as noted on the first page), Felsher’s conscious prison cell experiences what Foucault terms “permanent visibility.”

The crowds gradually shrank, until there would only be one person every few hours. And then one person a day. Then one a week.

When there was nobody left and the artist couldn’t move, the prison cell said, “Why do you do this to yourself?”

The prison cell’s feeling of imprisonment is not strictly a physical or architectural apparatus. The knowledge of being under constant observation alone is imprisonment enough. We also learn, from one of the pebble’s rants, that prison can take many forms: credit scores, money lending, gender, and, especially, language itself. The pebble’s mention of language reminds me of Bataille’s thoughts in Guilt:

“Communication, through death, with our beyond (essentially in sacrifice) – not with nothingness [le néant], still less with a supernatural being, but with an indefinite reality (which I sometimes call the impossible, that is with what can’t be grasped (begreift) in anyway, what we can’t reach without dissolving ourselves, what’s slavishly called God” (1988)

I think death, or, the undead, is appropriate when considering what exactly the prison cell is. Is it actually a prison cell? Is it an art installation? When the poor artist eventually returns to the prison cell to live out his days as a performance artist (perhaps similar to exhibit A or exhibit B), spectators dub him “The Prisoner.” Later, a more emaciated version of The Prisoner becomes “The Body.” In this moment, the art installation feels closest to a “tomb” (i.e. Bataille’s “communication, through death”) as echoed in the Kim Hyesoon poem quoted above:

Like a tomb there’s no emergency exit anywhere

Every day I walk the same corridors that jail me

Foucault’s detail of permanence also feels necessary since, spoiler alert: part of being the prison cell (with an unknown expiration date) means watching it outlive (?) some of its companion-spectators. And, speaking of what and/or who watches, it also feels important not to forget that while readers are eventually introduced to the fictional artist who made the prison cell, we know the creator of the prison cell is also undeniably Andrew Felsher, author of Notes from a Prison Cell.

In Felsher’s notes, one will find hole-like echoes of Kim Hyesoon, a playfully dark sense of humor reminiscent of David OReilly, and the self-discipline and self-imposed resistance explored in artist Matthew Barney’s earliest iterations of his Drawing Restraint series. The chapbook also features remarkable illustrations by artist Fi Jae Lee (who one cannot help but associate with the many translations of Kim Hyesoon’s poetry). Specific to Notes from a Prison Cell, I’d describe Lee’s rectangular three-dimensional images as ideological chambers. In these prison cell-like chambers, readers will witness the startling remains of human beings: leaking organs, wristwatches, books, bones, boomboxes, censored orifices, and limb after limb after limb. Surreal, residual decadence.

And now, without any further adieu, “Say thank you. Drown in the algorithmic quicksand.”

May 8, 2025

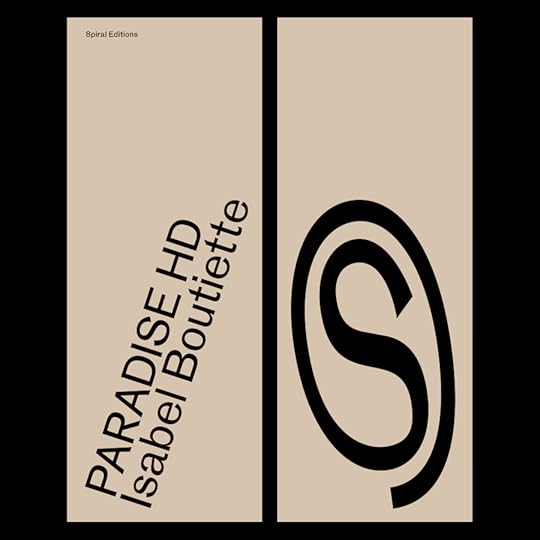

“REVISIONS of movement”: A Review of Isabel Boutiette’s PARADISE HD

Isabel Boutiette’s PARADISE HD (Spiral Editions, 2024) ventures into unknown territory via Lyn Hejinian and Leslie Scalapino’s collaborative conception of a boundless self. The chapbook opens with the following quote from Sight:

This simulacral (willed?) nation would have been a closed (self-defining) system. One might say it had been narrated into paradise.

PARADISE HD wastes no time in introducing us to a dusty, finger-sucking “I”—a drone-like beach-wandering vacuum called AMBER—whose dust bag interior rattles with crab carcasses, oxidized bells, empty cans, and other assorted microplastics. Boutiette aligns her vacuum-speaker with the sensory expertise of a mime: “in the whir sound / REVISIONS of movement / miming your salty finger / in my mouth.” Sand-sucking AMBER spends her days on the mysterious “BEACH” contemplating the differences between a “system” and a “performance” as all-caps WORDS flutter across her forehead:

the SCREEN’s BEACH

is the DRONE’S BEACH

the BEACH, appears not

as system, but

BEACH as the performance of BEACH

light feeds to more light

The way the WORDS repeat throughout AMBER’s mind (or programming?) feels similar to Hilda Doolittle’s own startlingly lucid dreams and recurring visions. Especially her memorable rendering of a ladder in the scene from Tribute to Freud when Doolittle astral projects an image onto a blank wall:

I must hold on here or the picture will blur over and the sequence be lost. In a sense, it seems I am drowning; already half -drowned to the ordinary dimensions of space and time, I know that I must drown, as it were, completely in order to come out on the other side of things (like Alice with her looking glass or Perseus with his mirror). I must drown completely and come out on the other side, or rise to the surface after the third time down, not dead to this life but with a new set of values, my treasure dredged from the depth. I must be born again or break utterly.

AMBER also doesn’t appear to recognize a sky when gazing at the BEACH, but there are “clouds fogging” over a “screen.” If the BEACH is in fact a simulacrum and the sky a screen, perhaps PARADISE HD is about learning how to “break utterly” in order to shatter the screen of a former self. To break with the limits of one’s social environment. To shatter Videodrome-style (i.e. “Long live the new flesh”) and enact “REVISIONS of movement.” This breaking is also reinforced in Boutiette’s glitch-rapid use of enjambment as well:

a metallic form

gelatinous in the Unreal

I’m a type of a paper

I mean

I’m your type, on paper

the poem a possibility

coiling forward

tits first

Boutiette’s title itself posits the idea of clarity as an ultimate, but not necessarily achievable ‘paradise.’ The entire so-called purpose for high-definition television (HDTV) has always been the same: to improve picture quality and to make footage clearer, more realistic, and more immersive. This promise of the imaginary (and its lucrative ties to consumerism) will continue to sell the idea of “paradise” as long as consumer-spectators are prevented from achieving actual immersive experiences in the real world—beyond the screen.

We also eventually learn that AMBER is not just a name, but also a product model. She and a fellow rattling AMBER (“I’m here, there’s only / five others left”) are just two of multiple AMBERS roaming the BEACH’s interface. However, these AMBER models (or products) demonstrate consciousness (“earth so desolate now / that I’m caught / thinking about it”) and a desire for companionship or selfhood (“I’m trying to find my person / this simulation of memory”).

The narrative unfolding of PARADISE HD changes significantly when AMBER’s addressee becomes the ocean shore: “can I steal you for a second?” AMBER steals a jellyfish from the SHORE. The use of the term “SHORE” feels significant. AMBER steals a jellyfish—not from the beach or the ocean—but from the blurred line that divides ocean from beach. In a way, in that moment, the image of a jellyfish takes over. Gives new form to AMBER: “I lived soluble / for so long / a gel sighing / away from / immersion.” From that moment on, the former AMBER appears to be caught in a glitch. Frozen. Forever loading like her fellow AMBERS: “the BOYS are loading / the GIRLS are loading / I am especially loading / in the chlorine ripple again.”

Boutiette’s PARADISE HD puts all its eggs in an amber basket. The endless dialectic between the real and the unreal. Like trying to vacuum a beach. Or desert. Boutiette leaves readers to sift through—see—the mirage for themselves. What is and what appears. A cassette tape sucked from the sand. A salty finger presses “Play.” A song comes on. The sun zeroes in:

And I thought I was mistaken

And I thought I heard you speak

Tell me, how do I feel?

Tell me now, how should I feel?

March 18, 2025

Sociocide at the 24/7

Last month my third book of poetry, Sociocide at the 24/7, was released by DIAGRAM/New Michigan Press. The University of Notre Dame book launch can be viewed [here]. The book was also recently featured in Dennis Cooper’s “Five Books I Read Recently and Loved” series.

“I guess it’s part of every country that if you’re proud of where you live and think it’s special, then you want to be special for living there, and you want to prove you’re special by comparing yourself with other people. Or maybe you think it’s so special that certain people shouldn’t be allowed to live there, or if they do live there that they shouldn’t say certain things or have certain ideas. But this kind of thinking is exactly the opposite of what America means.”

— Andy Warhol, AMERICA

One of several major inspirations behind Sociocide at the 24/7 was Warhol’s writings — fascinating meditations on both celebrity and death — that appear in his 1985 photography book AMERICA. At one point he compares tourists in Washington to tourists in Disneyworld. But, perhaps most memorable, is when he says he’d wished he had died after he was shot in 1968. Two bullets ripped through his stomach, liver, spleen, esophagus, left lung, and right lung. Juxtaposed with photographs of a cemetery in Lenox, New York is this quotation which opens Sociocide at the 24/7:

“I always thought I’d like my own tombstone to be blank. No epitaph, and no name. Well, actually, I’d like it to say ‘figment.'”

Upon learning this, I was doubly reminded of Baudrillard’s writings on simulacra and Disneyland, but also Disney’s somewhat failed mascot “Figment” — first introduced in 1983 as part of the “Journey into the Imagination” attraction at Epcot.

Many of the poems of Sociocide at the 24/7 attempt to expose the dangers of unchecked imaginations — especially the imaginations of American influencers and so-called entrepreneurs.

Today, video of Warhol’s gravesite can be livestreamed 24/7. The project is a collaboration between the The Andy Warhol Museum and EarthCam. The collaborative project has been called “Figment.”