Luke Bauserman's Blog

December 19, 2017

The Dark Side Of The Woods: An Interview With Author Willie Dalton

“If you go back far enough, no town is boring.” Author Willie Dalton joins us this week to talk about her supernatural romantic thriller, The Dark Side Of The Woods.

The post The Dark Side Of The Woods: An Interview With Author Willie Dalton appeared first on The Weekly Holler.

November 20, 2017

Thanksgiving Meals That Got Away (or Almost)

Most of us get our Thanksgiving dinners from the grocery these days, but that wasn’t always the case. Before the advent of modern refrigeration, holiday meals were usually living in the woods or the farmyard until the day of the feast. Sometimes this resulted in Thanksgiving dinners making a break for it. Here are several stories from such occasions:

Thanksgiving ‘Possum Escapes When Firemen Extinguish Tree Fire – The Atlanta Constitution (Atlanta, Georgia) · Fri, Nov 26, 1920

A Thanksgiving ‘possum hunt by boys at Inman Park terminated in a manner disappointing to the boys when neighbors summoned the fire department to avert the destruction of a venerable hollow oak tree in imminent danger of being burned by the “smudge” which the boys set to smoke out “Br’er ‘Possum,” and which a brisk wind whipped up into a blaze over which the lads quickly lost control. “Br’er ‘Possum escaped in the shuffle, and the lads ruefully returned to their homes. Firemen related a similar occurrence Thanksgiving day a year ago.

Escape of a Thanksgiving Raccoon and the Fun That Followed – The Morning News (Wilmington, Delaware) · Sat, Nov 29, 1890

Early on Thursday morning a man came along the north side of Eighth street going east. He had under one arm a live and very frisky raccoon, which he had evidently intended should take the place of a Thanksgiving turkey. Be that as it may, just as he was about to cross Shipley street he lost his grip on the coon, which suddenly sprang to the ground. When the prospective coon-eater gathered his wits he found that his dinner had climbed to the top of a maple tree. Quick as a flash he mounted that tree. The higher he climbed the further out did the coon climb. The branches bent under the weight of the anxious coon chaser.

Thomas J. Goslip on whose pavement the tree stands opened a window of his house and ordered the man down, as he was afraid that the old tree would break and the man would be hurt. The man came down at once. He was disgusted and told the gathering crowd of people that the one who caught the coon could have it.

By this time the coon had crossed to a tree on the pavement of St. Andrew’s Church and settled down on the outer end of a limb to await developments. Then it was that burly man started to make chase. The crowd, which had increased to 200 persons, cheered and jeered as the burly man climbed.

“I’ll shake him down,” he said, “and the feller what catches him will please hold him for me.” The crowd agreed to that and kept up their jokes.

After a vigorous shaking of the limbs the coon dropped to the sidewalk. The crowd parted to give the little animal a chance. He took it, and darted up Eighth street toward Orange. The crowd started after him, and he was soon captured and taken back to the man who had dislodged him. The happy man seized the coon by the tail and started toward Whitechapel followed by the crowd.

Ducks Escaped Thanksgiving Mess – The Lincoln Star (Lincoln, Nebraska) · Sat, Dec 5, 1914

Weeping Water, Neb. Dec. 5.—Yesterday morning two ducks belonging to Mrs. Ohnmacht, living at Nebraska City, returned to their quarters in the chicken house after what had evidently been a week’s vacation taken to avoid being served up for a Thanksgiving dinner. Mrs. Ohnmacht sold the ducks to John Franks a day or two before Thanksgiving and was to deliver them a little later. The morning after the sale she discovered the chicken house door open and the two ducks and six chickens missing. No trace of the fowls was found until the ducks returned Thursday morning. The six chickens have not yet put in their appearance.

1,000 Thanksgiving Dinners on Loose – The Wilkes-Barre Record (Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania) · Tue, Aug 10, 1943

A thousand Thanksgiving dinners were on the loose in a Des Moines suburb today.

That many 10-week-old pheasants answered the call of the wild and flew out of the rearing pens at the L. E. Heifner Hatchery.

Attempts to drive the birds back into their pens met with little success.

Heifner said due to wartime shortages he had been unable to cover the pens with chicken wire. He had clipped the birds’ wings once but they grew out sooner than he had anticipated.

Heifner was growing the birds for the holiday trade.

The Sad Fate of A Gobbler, Escaped the Thanksgiving Axe But Met Death Next Day – The Morning Call (Allentown, Pennsylvania) · Tue, Nov 30, 1897

Dr. George Seiberling had an immense turkey gobbler, which, after he found out he had escaped the Thanksgiving Day axe, went and committed suicide on Friday. This is perhaps the only case on record where a gobbler’s pride was so wounded after seeing many of his brothers chosen for the feast and himself left that he went and ended his existence.

The doctor had invited his parents and the parents of his wife to spend Thanksgiving at his home. The parents, however, found it impossible to be here upon that day, and it was decided that the gobbler’s day should be prolonged. His wings were clipped, and then he was allowed to be king of all he surveyed in the backyard. But the gobbler’s heart was sore, and, for want of company, he pined. Looking through openings in the fence, he spied others of his tribe and on Friday he decided to join them. He managed to get up on the fence, but must have lost his balance between two palings protruding on one side and the body went down up the other, and, there suspended from the fence, the doctor’s gobbler ended his days.

Hundred Turkeys Fleeing From The Thanksgiving Ax – Chicago Tribune (Chicago, Illinois) · Wed, Nov 27, 1901

Scattered through the woods in North Evanston a hundred turkeys, destined for Thanksgiving tables, are enjoying liberty through the grace of a team of restless horses. The turkeys were the property of Jacob Nellis, who has a large poultry farm a few miles from the town, and whose birds are farmed for their size and fatness.

Nellis placed his turkeys in coops, loaded the coops on a wagon, and started for Evanston with them yesterday afternoon. At North Evanston, when he left the wagon to get a drink, the team became frightened and ran away. The wagon was overturned, the frail coops broken from the force of the fall, and the turkeys fled to the shelter of the trees which lined the road. The sun was going down, and in the darkness the turkeys proved exasperatingly elusive. Nellis gave up the attempt to capture them and returned home, resolved to try again today.

Fat Fowl for Thanksgiving Dinner Escapes and Hunting Party is Formed to Capture the Bird – Delaware County Daily Times (Chester, Pennsylvania) · Tue, Nov 28, 1911

It is seldom that the residents of this section of the state get an opportunity to go hunting for turkeys, except when the hunt takes them to the stores. On the Ralston property was a fine turkey, which was growing steadily fatter as Thanksgiving day drew near, and the owners were already smacking their lips over the quantity of white and dark meat he would provide, when the turkey, evidently knowing what was in store for him, escaped from the farm. For a week he did not return and then an organized hunt was made for him. In a clump of woods quite a distance from the farm the gobbler was discovered and the pursuit began, but every effort to get close to the bird was vain, the wily bird baffling all their attempts. The owner finally went for a shotgun and a charge of shot brought the bird to an untimely end.

Turkey “Sniped” From Uptown Building – The Pantagraph (Bloomington, Illinois) · Wed, Nov 25, 1914

A bunch of live turkeys had been cooped up in the rear of the Schneider meat market, and yesterday morning employees of the place proceeded to dress them. In the scrimmage, one of the largest of the birds escaped into the open. Using his long-neglected power of flight, he soared out over the street and up to the roof of the Ferre building opposite. There he alighted and sat in serenity. The question of how to get him down seemed at first a serious one. But soon some one suggested to a group of men in the [nearby] gun store the practical idea of “sniping” the bird. No sooner said than done, and in a minute there was the short crack of a rifle shot ringing out over West Front street, and his bird-ship came tumbling to earth. His demise was quick and painless, and a good Thanksgiving dinner was saved to some one. The incident attracted considerable attention in the vicinity.

I hope you enjoyed this week’s stories. The Weekly Holler wishes you and yours a happy Thanksgiving. May your turkeys stay put and your hams never wander.

The post Thanksgiving Meals That Got Away (or Almost) appeared first on The Weekly Holler.

November 13, 2017

The Phantom Inn: A Tale of Thanksgiving Eve

If you thought Halloween was the only holiday with scary stories, you were wrong. The following Thanksgiving tale was written by Hezekiah Butterworth and appeared in the November 26th, 1893 issue of The Philadelphia Inquirer:

I’ve gone down to Greenharbor from Boston in an old stagecoach on many cold nights like this, with the wind rising in the tops of the trees, and clouds scudding over the moon. I’ll tell you a tale of one of those nights, but be warned, some folks say that it makes them lie awake at night when the shutters bang.

The coaches in those days had great leather boots that covered the driver’s legs. When the weather was cold they could be raised high enough to protect nearly the whole body. Many a time I have driven my horses, protected from the rain or snow by the boot. Under the boot, I carried the mail bags and such packages as we today send by express. I had an old dog that would ride with me. A sailor gave him to me, and that dog would ride under the boot at my feet among the mailbags. He was an unusual animal. I was teaching him some tricks one day, and he was begging for a treat when he made a sound like my name. I repeated it, and he uttered it again. After that, I would hold him back from his food until he had made that sound. “Say Silas,” I would command, and after a time he would utter the word. In time he would rise on his hind legs shake his paws, and say “Silas” whenever he wanted food. I was very proud to have him call me by my name, and I had him do it whenever I met my friends. He became a kind of neighborhood wonder, and was called the ‘talking dog.’

I sometimes took my coach on side tours through the Dedham woods. Those woods used to be a lonely place. It’s mostly farms now, but the forest used to stretch all the way to the coast. There were no towns like Hyde and Park then, no costly summer homes. The forest had a woodsy smell in the fall, and the air was full of the odor of sassafras in the spring. The crows had nests in great groves of pine trees that looked like islands amid the white birches. The sunlit spaces between the trees were full of blue jays that would eye my coach with outstretched necks. I can seem to see them now. Oh, but those were lonely roads in the winter. The winds used to whistle. They seemed to catch the spirit of the sea which was not many miles away.

There came a time when strange happenings were reported in the Dedham woods. Several travelers who had gone through those woods at night had met with strange adventures. They had seen a window and a light in a lonely place, a little distance from the road, and heard the ringing of a bell like a supper bell. Two of them had turned toward the window, but as they attempted to approach it, it seemed to draw back into the heart of the woods. After walking toward it for a considerable distance it seemed to them no nearer, and they had become alarmed, and suddenly turned and fled, believing it to be a ghost. One traveler, who had entered the road at dusk, had never been heard of again.

After these events, anyone who saw the window at night took to his heels and at last few persons would go through the woods after dark, except in a carriage, or in company. No one riding in a carriage had ever seen the mysterious window, but one man riding there alone had been attacked by an unknown person and robbed. The Dedham woods began to bear a bad reputation, and the dark events that happened there were assigned to ghosts, and the vanishing window and light were spoken of as the “Phantom Inn.” Around that time I was frequently warned to beware the Phantom Inn, and I used to answer such warnings with a laugh and say to my dog, “We aren’t alarmed, are we? Speak, dog!” and the dog would rise up and shake his paws and say, “Silas!”

Was I ever afraid when riding alone in the old Dedham woods? I always speak plainly and must say that I sometimes was. A sort of shadow of fear would come over me. I never truly believed in ghosts or haunted houses after my early years. Yet a superstitious nature clings to me. It has often made me feel jittery until I stop to reason.

Then came the time that people began to move away from Boston to New York State. They called it “up country” then. The Mohawk valley seemed as far away at that time as the prairies do now. I had a good offer to go to Albany and drive the stage route from there to Buffalo. I caught the “up country” fever and resolved to go. One of my greatest regrets on parting was that I left my coach dog behind at Greenharbor when I made the move.

One day as I was stopping at the old Scituate Inn, just before setting out for Albany, I met a stranger there. He called himself Searle. I shall never forget the eyes of that man. There seemed to be a hidden spirit, not himself, looking through them. It was unsettling. My dog seemed to see something mysterious in that man’s eyes too because he leaped into the air when Searle appeared and said ‘Silas!’ He shook all over, dropped to his feet, and ran round and round me, whining in a fearful tone. It used to be said in old New England times that dogs would see ghosts coming before people could see them, and that was one reason they would start up and howl without an apparent cause.

“I hear you’re goin’ up country,” said Searle.

“Yes, I have concluded to take the Albany route,” said I. “There is more money in it.”

“Goin’ to take your dog here along with you? He’s a fine one.”

“I am uncertain,” said I. “I’ll have to go by way of New York, and up the river to Albany, and they don’t allow dogs on the boat.”

There came a strange light into the man’s eyes. “Don’t want to sell him, do ye?”

I hesitated. “Stranger,” said I at last, “where do you live?”

“Oh, in a lonely place down by the ponds in Dedham woods. They say it’s gettin’ dangerous there, and I want a dog to guard the house. I need one. Say, as you’re goin’ off, what will you take for him?”

“I don’t know—I wouldn’t sell him for anything. I set a store by that dog.”

“I’ll give you $10 for him. That is high, but I’m lonely like, and they say them woods are gettin’ dangerous. What do you say?”

“You may have him.”

I felt somehow that I had down an unworthy thing: That I had sold my dog to an unworthy master. That dog had such a true nature that he would never have tricked me with any act. There is something dark in any moment of life when a man feels that he is false in anything. The Scriptures of a man’s inner life are true, and they demand, as in old the Hebrew bird’s nest commandment, that a man shall be sincere even with animals, and keep the golden rule with brute creation.

How should I part with my dog? I felt my head ache at the thought of it—the dog had been so faithful. I decided that I would have Searle put a rope on his collar, and would leave him in the evening in the office of the inn with him, and so steal away from him unknown. I did—and if ever I felt like a coward, it was then.

I never could bear to think of that dog, and yet I could never quite forget him. I used to imagine months afterward, that I could feel him lying at my feet on the Albany stage.

Five years passed when one November day I received a letter at Buffalo from Greenharbor. My old friends, the Whites, had remembered me, and they invited me to spend Thanksgiving with them at Greenharbor. My wife’s folks lived in the old town of Dedham, and she urged me to accept the invitation as she wished to go with me and visit her family.

So I secured a driver to take my place for a few weeks, and we set out for Boston and Dedham. One day, late in November, I left my wife among her folks and set out for Greenharbor, intending to visit my old friends. I had expected to start in the morning and make a day of it, but I was delayed until the afternoon. It was delightful Indian summer weather, and I did not mind a night walk, as I could rest at my friends’ home.

“Don’t stop at the Phantom Inn,” said my wife as we parted.

“I shan’t stop at no Phantom Inn,” said I, “if I expect to reach Randolph tonight. There will no acorns sprout under my feet.”

“But,” said my wife’s mother, “they do tell strange stories still about these woods. Are you armed?”

“Yes, as much as I ever am.”

Nightfall overtook me at the border of the old Dedham woods. I still remember the strange, mysterious feeling that came over me as I entered the shadow of the pines on that lonely road. I stopped and looked back. The west was red: corn stacks stood on a hillside farm, and I could hear the merry voices of the huskers. The air seemed hollow and still. As I stood there listening there came a vivid impression that somehow I was in the companionship of the old coach dog, as I used to be. I could feel my heart shrink as I recalled how meanly I had treated him, and I eased my conscience with the reflection that I had done as well for both him, and myself, as I could.

There are subtle atmospheres in which mind may commune with mind, and convey impressions and needs and warnings. That a dog might make its presence felt in some way by a mysterious force is possible, I cannot say, but I repeat it—I seemed to feel that the old coach dog was somewhere near me in these woods and that he knew I was there too.

I entered the lonely way, walking along with a witch-hazel stick for a cane. A great light rose like a fire among the tops of the gray rocks and skeleton trees. It was a full hunter’s moon coming up from the sea. After a time it went into a cloud, but the way was still clear. It was almost as still as death.

Occasionally a timid rabbit would cross the way: once a rabbit leaped out before me, and I felt my heart beat and thought again of the old coach dog, and the tales of the Phantom Inn, at which I used to laugh when I drove the cape stage.

The way grew more lonely, amid the oaks and the russet leaves, pines, and rocks. In places, the road was strewn with fallen nuts, and at some points with rustling leaves. Once, the eyes of a white owl confronted me on a decaying limb—I thought of the eyes of Searle, the man who had bought my dog.

Here and there the faint poisonous odor of the wild dogwood bushes drifted across the cool air—I met the old familiar scent of the wild grapes, which hung in the crevices of rocks, and the cidery smell of some wild apples. The moonlight fell in rifts, as the clouds scudded, driven by some ocean wind along the sky.

I hurried on, hoping to reach Randolph before midnight, when, suddenly I heard a sound that stopped my feet at once, and sent a chill over me. It was a hollow tone, like the ringing of a supper bell, such as used to be common in the farmhouses and inns. I looked in the direction of the sound when I saw a little way from the road a window and a light among the trees.

“Is it imagination?” I asked myself. “Is it a dream of the old story? Shall I run or turn toward the bell?”

I was frightened, and my heart beat fast, but I am not a man to run. After hesitating for a few moments, I turned into the wood in the direction of the window and the light and found a path there, which I began to follow cautiously. I walked to the place where I had first heard the bell and seen the window and the light, but the window and the light were as far away now as when I started from the road. As I watched, I could see it move, but I could hear nothing. I stopped again. The window and light seemed to stop. Should I run? No, I would shout. So I cried out, “hullo!”

The rocks answered my loud call with many echoes. A startled partridge rose on whirring wings from some wild alder bushes near me. Then, all was still, or—did I imagine it?—I thought I could hear the low piteous suppressed whine of a dog. The light vanished.

I knew not what to do. The forest was dark, and I could hardly see. I went forward very slowly and cautiously. The path grew soft, and the earth began to crumble beneath my feet. I paused and listened—

A cry pierced the hollow air. How can I describe it? It thrilled every nerve in my body. I can hear it now. It seemed as though all the intensity of a human heart was in it—

“Silas!”

I knew the voice. It was a warning tone. I stepped back and listened again. I heard a splashing struggle down in the distance. Where was I? It came to me. I was on the border of a ledge of rocks. Below me was a pond. Had I taken a few steps more, I would have gone over into the water. I had been drawn into a trap to destroy me. My every nerve quivered with terror.

As I stood listening, a fearful oath rose from the pond. Then all was still. I looked up to the sky. It was the only object that seemed friendly. The clouds parted below the hunter’s moon, and a wide silvery light swept over the scene. I was surely on a projecting edge of rock or platform over the pond.

Suddenly I heard a sound in the bushes. It was a patter of feet. A dog came bounding out toward me. He rose up, springing as it were into the air, shook his paws and cried, “Silas!”

It was my old coach dog.

I hurried back to the road, followed by the dog. Was it a dream? What had happened?

At near midnight I came to old friend’s farmhouse at Randolph and roused the family. Before anyone could speak, I pointed to the dog.

“Tell me, for heaven’s sake, what is that?” I cried.

“That is a dog,” said my old friend, “your old coach dog What did you think it was? Where did you find him?”

We went the next morning to the scene of my night’s adventures. One of the first things we found was Searle’s dead body floating in the pond.

The light in the window of the Phantom Inn had allured me to the edge of a broad precipice, and I was just about to fall into the pond when my old coach dog saved me. The dog had evidently dragged his dark-minded master over the rocky cliff into the pond.

Searle had carried the window and light in his hand and with covered feet had moved back to lure travelers into the woods where he could trap and rob them.

Nothing ever made me so thankful as that one word, “Silas,” and I never passed a Thanksgiving when I didn’t reflect on it.

The dog? Yes, I must answer that question. What became of him? I took him back to Albany with me where he lived out the rest of his days.

I hope you enjoyed this story. If you like spooky stories, I think you’ll love my novel Some Dark Holler. It’s available on Amazon.com as an ebook, hardcopy, and audiobook.

The post The Phantom Inn: A Tale of Thanksgiving Eve appeared first on The Weekly Holler.

November 8, 2017

Captain Rufe’s Old-Time Turkey Shoot

Before the arrival of European colonists in North America, wild turkeys were everywhere. Some biologists believe that they numbered around 10 million and inhabited nearly every corner of what is now the continental United States.

Now wild turkeys make an incredible meal, having eaten both wild birds and their farm-raised equivalent I can attest to the difference that a diet of berries, nuts, and fresh plants makes in the taste of their meat. It didn’t take long for early colonists to discover how plentiful and delicious wild turkeys are, so it’s no surprise that they almost ate them into extinction—moving from a population of 10 million birds down to a couple hundred thousand in the entire US between 1910 and 1920. In fact, biologists have linked the Great Depression to the resurgence of wild turkeys in the US. The economic collapse drove many farmers out of rural areas to big cities in search of jobs, resulting in a lot of farmland reverting to the native habitat of the turkey.

But during the years when the wild turkey population was in steep decline, these birds were eradicated in 16 to 18 states where they had once been abundant. For the people in these areas, the wild turkey had become not only a food source but part of their cultural tradition. Every harvest season, marksmen would take to the woods to show their skill and return with a gobbler to be plumped down in front of their admiring family on Thanksgiving day. With no more wild turkeys in these areas, a new tradition arose, the turkey shoot.

A turkey shoot was an event where a domesticated turkey was tied behind a barrier that it could peek over. Marksmen sat at a distance and took turns shooting at the bird’s head, which proved to be a challenging target due to its small size, and the turkey constantly ducking behind the barrier. Whoever killed the turkey took it home as the prize. This allowed the village marksmen a chance to show off their skills around the holidays.

Such events date back at least to the days of author James Fenimore Cooper who wrote about a turkey shoot in his 1823 novel The Pioneers.

The following story is an account of a turkey shoot that took place in a small town in Michigan recorded by Sewell Ford and published in the Harrisburg Telegraph, on November 24, 1896:

Rufe Jackson worked every summer in the wheelhouse of a little tugboat in which he was captain and crew. During the fall and winter, Rufe turned his hand to almost anything that did not demand hard work and in which there was an honest dollar.

So along about Thanksgiving time there appeared in the local weekly paper a notice to the effect that “our enterprising and genial townsman, Captain Rufe Jackson, has secured from Detroit two dozen fine turkeys which he is fattening in anticipation of the annual Thanksgiving turkey shoot which he will conduct at the foot of Main street.”

Everyone knew the place indicated, for Main street had a definite foot, or ending, in the lake. So on Thanksgiving morning every man who thought he was a good rifle shot—and there were full two score in the village—could be seen making his way down toward the lake shore.

“Hello, doc! Where you goin’ with the gun?” was a common salutation on such occasions.

“Oh, just down the shore.”

“Expect to get one of Cap’n Rufe’s turkeys?”

“Oh, no! I’m just going to throw a little lead at ‘em for fun. Want to help Rufe out, you know.”

This reply would call out a hearty laugh, for it was well known that the doctor was one of the best shots in town and that he usually got a turkey pretty cheap on Thanksgiving day.

At the lakeshore would be gathered from 50 to 75 men, most of them with rifles, but some without The latter were the noncombatants who had come down to see the fun along with half the boys in the town. Out on the edge of the shore ice Captain Rufe had stationed his assistant with the turkeys, The birds were in crates and bobbed their heads up through the slats wonderingly. They were as excited and nervous as if they knew the fate in store for them.

The butt of a saw log which had been rolled out on the ice served as an executioner’s block. Behind this, the turkeys were tied. Had they had wit enough to crouch down behind it they would have been safe from the bullets, but the foolish birds constantly stretched up their necks to see what was going on, and thus offered a fair if not easy mark for the sportsmen. The assistant had rigged up a bulletproof windbreak of logs and boards, behind which he might seek shelter while the rifles were popping.

Inshore, 100 yards away, Captain Rufe had marked off the line behind which the marksmen were to stand. The boys had built up a fire of driftwood, where numbed fingers might be thawed out, and all was in readiness.

“Now, boys,” spoke up the captain, “we’re all ready for the slaughter. I’ve got two dozen fine birds out there, fat and young and tender, and it only costs you 10 cents a shot. Who will open the ball?”

The captain’s assistant had tied one of the turkeys behind the log, and the bird was peering foolishly about to see what was going to happen next. There was a loud laugh from the crowd when Tuttle, who ran the hardware store, stepped up to the improvised range and tossed a half dollar to the captain, with the remark that he reckoned he “could get two or three birds for that.”

As Tuttle was known to be the poorest but most persistent shot in town, his optimistic sally was regarded as the height of the ridiculous. With a good-humored smile, he told the crowd to watch him “knock that fellow’s head off” and blazed away with his new breechloading rifle. His first shot sent up a little cloud of powdered ice 20 feet to the right of the turkey. The second went as far to the left. The third was nearer the line, but fell 50 feet short, while the fourth went sailing harmlessly over the turkey’s head far out on to the frozen surface of the lake.

“You’re gettin’ the range, Tuttle, you’re gettin’ it,” the captain said, while the bystanders added other remarks which were not so encouraging.

“I’ll get him this time sure,” said Tuttle. But he didn’t. There was much discussion as to where his bullet really did strike, but the point was not settled. There was no disputing one fact—the captain had 50 cents in his pocket, and not a feather of his first bird had been touched.

While Tuttle was carefully cleaning out his rifle and reloading, another marksman stepped up to the line. His bullets went much nearer the mark than those of the hardware dealer’s, but a turkey’s head is not an easy mark to hit at 100 yards, especially when a strong wind is sweeping across the range. So inside of half an hour, Captain Rufe had been paid almost as much as the bird cost him, and was feeling very good natured.

Then Hayes, the blacksmith, shouldered his way to the front, unlimbered his rifle and squinted carefully along the sights. It took three shots before he got the gauge and his fourth bullet made the splinters fly from the log. His fifth and sixth shots were evidently close, but it was not until the seventh shot that the waving neck of the turkey disappeared from sight.

“Got him that time, Hayes!” remarked the captain. “Here, boy, run down and get that bird, will you?”

When the trophy was brought back, it was “hefted” by the crowd, who decided that it was a good 12 pounder.

Then the doctor signified his intention of shooting a little, and a fresh bird was put up. The doctor got him at the sixth shot, and the captain said that 60 cents was twice as much as he had expected to get from him.

Then came the other marksmen. Some of them shot as many as a dozen times without even hitting the stump, and the next three or four turkeys which were killed brought the captain in from $1.50 to $2 each. The firing had been going on merrily for an hour when a peculiar looking figure came shuffling down the street.

“Hello! Here’s old Jake.”

Jake proved to be a half-breed Indian, well known as a village character. A cur dog loped along at his heels, and he trailed an antiquated and battered muzzleloading rifle. Jake viewed the shooting for awhile and then handed out a 10 cent piece to the captain without a word. Raising his long-barreled gun to his shoulder, he cautiously took aim and fired. The turkey’s head still waved defiantly, and Jake swore fluently. With a good deal of grumbling, he fished out another dime and reloaded his rifle. It was evident that he meant business this time, for he peered carefully through the sights before he pulled, and the turkey’s head disappeared. Jake’s second bullet had cut the bird’s head off as clean as if it had been severed with a hatchet. Tuttle brought the prize, and Jake went back up town to invest the proceeds of his marksmanship in hot and rebellious liquor.

These are some of the incidents connected with the most recent turkey shoot that I witnessed, and, although that was a dozen years ago, I suppose that this coming Thanksgiving there will be a similar gathering down on the lake shore.

Source

Harrisburg Telegraph (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania) · Tue, Nov 24, 1896

The post Captain Rufe’s Old-Time Turkey Shoot appeared first on The Weekly Holler.

October 29, 2017

Hellhounds of Appalachia

In 1937, Robert Johnson recorded one of the most haunting blues songs of all time, “Hellhound on My Trail.” While experts debate the exact meaning of Johnson’s lyrics, the imagery is chilling. The first time I heard the song, I immediately imagined a beast like the Hound of the Baskervilles chasing a blues singer through the backwoods of Mississippi.

The association between dogs and the underworld is very widespread in ancient folklore and has continued into modern times. In ancient Egypt and Rome, fearsome dogs guarded the gates to the underworld. The British Isles have a rich tradition of “black dog” lore. Such critters are associated with death, bad omens, the Devil, and crossroads. It’s no surprise then, that when Europeans settled in the mountains of Appalachia, they brought their folk tales with them. In Virginia Folk Legends, Thomas E. Barden writes that during the New Deal, researchers employed by the Virginia Writers’ Project gathered twenty-one narratives of supernatural and/or “devil” dogs in their collecting, most of them from Appalachia and all of them from mountainous regions of the state. . . . One striking aspect of the stories. . . . is how similar their descriptions of ghostly dogs are. “The dogs are always large and black, and they have remarkable eyes, which are variously described as being red, ‘as big a saucers,’ and ‘shining like balls of fire.’”

In writing my novel Some Dark Holler, I spent a lot of time hunting down and reading these “devil dog” stories. My favorite one was “The Black Dog of the Blue Ridge,” recorded by Mrs. R.F. Herrick in 1907. In it, we meet a supernatural black dog who is both a terrifying creature and a character worthy of sympathy. It was this story that inspired me to take a similar approach to Sampson, the hellhound in Some Dark Holler.

The Black Dog of the Blueridge

In Botetourt County, Virginia, there is a pass that was much traveled by people going to Bedford County and by visitors to mineral springs in the vicinity. In the year 1683, the report was spread that at the wildest part of the trail in this pass there appeared at sunset a great black dog, who, with majestic tread, walked in a listening attitude about two hundred feet and then turned and walked back. Thus he passed back and forth like a sentinel on guard, always appearing at sunset to keep his nightly vigil and disappearing again at dawn. And so the whispering went with bated breath from one to another, until it had traveled from one end of the state to the other.

Parties of young cavaliers were made up to watch for the black dog. Many saw him. Some believed him to be a veritable dog sent by some master to watch; others believed him to be a witch dog. A party decided to go through the pass at night, well armed, to see if the dog would molest them. Choosing a night when the moon was full they mounted good horses and sallied forth. Each saw a great dog larger than any dog they had ever seen, and, clapping spurs to their horses, they rode forward. But they had not calculated on the fear of their steeds. When they approached the dog, the horses snorted with fear, and in spite of whip, spur, and rein gave him a wide berth, while he marched on as serenely as if no one were near. The party was unable to force their horses to take the pass again until after daylight. Then they were laughed at by their comrades to whom they told their experiences. Thereupon they decided to lie in ambush, kill the dog, and bring in his hide.

The next night found the young men well hidden behind rocks and bushes with guns in hand. As the last ray of sunlight kissed the highest peak of the Blue Ridge, the black dog appeared at the lower end of his walk and came majestically toward them. When he came opposite, every gun cracked. When the smoke cleared away, the great dog was turning at the end of his walk, seemingly unconscious of the presence of the hunters. Again and again they fired, and still, the dog walked his beat, and fear caught the hearts of the hunters, and they fled wildly away to their companions, and the black dog held the pass at night unmolested.

Time passed, and year after year went by, until seven years had come and gone, when a beautiful woman came over from the old country, trying to find her husband who eight years before had come to make a home for her in the new land. She traced him to Bedford County, and from there all trace of him was lost. Many remembered the tall, handsome man and his dog. Then there came to her ear the tale of the vigil of the great dog of the mountain pass, and she pleaded with the people to take her to see him, saying that if he was her husband’s dog, he would know her.

A party was made up, and before night they arrived at the gap. The lady dismounted and walked to the place where the nightly watch was kept. As the shadows grew long, the party fell back on the trail, leaving the lady alone, and as the sun sank into his purple bed of splendor the great dog appeared. Walking to the lady, he laid his great head in her lap for a moment, then turning he walked a short way from the trail, looking back to see that she was following. He led her until he paused by a large rock, where he gently scratched the ground, gave a long, low wail, and disappeared. The lady called the party to her and asked them to dig. As they had no implements, and she refused to leave, one of them rode back for help. When they dug below the surface, they found the skeleton of a man and the hair and bones of a great dog. They found a seal ring on the hand of the man and a heraldic embroidery in silk that the wife recognized. She removed the bones for proper burial and returned to her old home. It was never known who had killed the man. But from that time to this the great dog, having finished his faithful work has never appeared again.

This story appears in Six Tales from Sixmile Creek, the companion volume to Some Dark Holler. You can pick up a free copy of Six Tales from Sixmile Creek here.

Sources

Herrick, Mrs. R. F. “The Black Dog of the Blue Ridge.” Journal of American Folklore 20 (1907): 151-52.

The post Hellhounds of Appalachia appeared first on The Weekly Holler.

October 15, 2017

You Can Find His Bones In Hangtown

It was like nature knew where I was headed and had decided to provide the perfect atmosphere. The roads snaked through dry cornfields and hills covered in autumn trees, a thick fog turned familiar places into spooky landscapes. I couldn’t think of a more fitting setting for the dark tale I was tracking down.

My trip took me to Ragersville, Ohio. A small quiet town nestled in the backroads of Amish country.

But this sleepy little village has another name, Hangtown, and I was here to see the skeleton in the community closet, literally.

One hundred and forty-four years ago a man called Jeff Davis was lynched in this town, and it happened right here as you enter Ragersville. The story is like many tales of 19th-century vigilante justice, but the difference here is that the town of Ragersville still has Davis’s skeleton.

Local historian, Ray Hisrich, met me at the Ragersville Historical Society to show me Davis’s bones, which now reside in the basement.. I followed him down a set of creaking stairs to a glass case which holds the remains. “There’s Jeff,” Ray said pointing to the skeleton. “He’s around 5’6”, 5’7” and when you stretch his bones out and everything he’s just about the right size.”

The story goes that Jeff Davis was a vagabond that came through Ragersville. Davis had been in legal trouble in Ragersville before and folks said he was back in town to get even with the men who had put him behind bars. This time around, he assaulted several women and a little girl in this sleepy little town, and a warrant was put out for his arrest.

Davis was apprehended and brought to Ragersville on the evening of July 26, 1873. The newspaper recorded what happened later that night.

While Davis was in the Justice’s office, in the custody of the officers, and waiting for the witnesses to arrive, a crowd of unknown men from the country, seized the prisoner with great violence, first blowing out the lights, then knocking him down with a poker; then after firing seven pistol shots into his body, dragging him from the office by a rope attached to his heels some distance through the town to a tree, and there hung him up by the neck until dead.

The Democratic Press (Ravenna, Ohio), August 14, 1873

Details on the lynching are sometimes unclear because the residents of Ragersville were tight-lipped about the matter.

“Way back, you couldn’t get information from the people,” Ray said. “They still weren’t giving out information. Their grandparents were in on it, and they were always told ‘we don’t talk about that.’ There was an old lady up the road, we tried to get her to tell the story. She said ‘no, we don’t talk about that.’ She was about a hundred. Her dad would’ve been in on it, dad and grandpa, her dad would’ve been real young. She would not talk about it.

And then we have documents here, the criminal documents of this township, and when it comes to that date there’s nothing there. Blank. No one ever went to jail, no one was ever tried. everyone was in on it. I think law enforcement just looked at it and said, there’s no family here, he had no family.”

Over the course of the visit, I worked up the nerve to ask Ray a question I’d thought of while he was telling the story. “Do you have any ancestors that would’ve been around for that?”

“I think my great-grandfather probably could’ve been involved,” he said. “I wouldn’t want to say, but they had just about all of the head family members in on this thing. They all got together and they said, ‘listen, it’s all of us or none.’ And so, as they questioned people, they questioned everybody, and no one knew anything. Nothing.”

So how did the skeleton come to be in the basement of the Ragersville Historical Society? It was in large part due to Ray’s efforts.

“Well, so they threw him over the county line, buried him in a sawdust pile. They thought, get him to Holmes county, instead of Tuscarawas County. At that time doctors could take a body that wasn’t claimed and use it for study. A Dr. Miller got him in Shanesville… ended up over here in Ragersville with a Dr. Peters. And Davis was in his doctor’s office for sixty years or better. My dad said as kids they’d go by that doctor’s office and it was haunted, they didn’t want to go by there at night because they were afraid of that skeleton in there.

And then Dr. Peter’s son sold it to a fellow in Sugarcreek, he traded him for a box of cigars. They wanted this skeleton to hang int he woods to scare the coon hunters that came down. Different guys came down from the city wanting to hunt coons all the time. But the fellow’s wife said ‘no way!’ So he took it to an undertaker. The undertaker kept it for years, he gave to his daughter who became a nurse, she used it for study. Her husband was a doctor, he used it for study. I had talked to them years back and said, ‘if you ever want to get rid of it let us know.’ So she called one day, and my dad and I went over and picked him up. ”

If you’re ever near Ragersville, I recommend stopping in and touring the museum with Ray. He’s a great local historian and has a sense of humor well suited to the subject matter.

“I always tell everybody that since that hanging, we really haven’t had many problems here.”

The post You Can Find His Bones In Hangtown appeared first on The Weekly Holler.

September 19, 2017

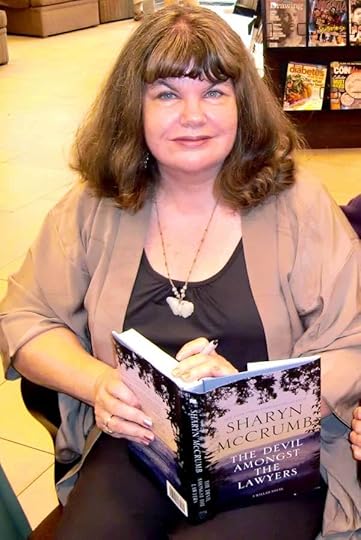

The Unquiet Grave: An Interview With Author Sharyn McCrumb

A mere three months after her wedding, Zona Heaster Shue of Lewisburg WV was found dead at the bottom of the stairs in her log home. It was January 23, 1897, and the body was found by a neighbor boy who did chores for her.At first, Zona’s death was said to have been caused by “an everlasting faint” followed an unfortunate fall down the stairs.

Shortly after Zona’s burial, her mother began telling neighbors that Zona’s ghost had appeared to her saying that she had been murdered. The villain behind the crime was Zona’s husband, Erasmus Stribbling Trout Shue.

Enlarge

Zona’s mother went to the law, and an exhumation of Zona’s body was ordered. The autopsy revealed that Zona’s death had indeed been the result of foul play. Her neck was broken and bore finger marks indicating that she had been choked.

Zona’s husband was arrested and found guilty on June 22, 1897, making Zona’s case the only case in the American judicial system in which the testimony of a ghost helped convict a murderer.

But there is a lot more to this story.

Enlarge

In her newest book, The Unquiet Grave, New York Times Bestselling author Sharyn McCrumb tells the story of Zona Heaster Shue like it has never been told before. The Unquiet Grave hit shelves on September 10th, and Sharyn was kind enough to carve time out of her book tour schedule to do an interview with The Weekly Holler. I hope you enjoy it!

Enlarge

Luke: So, first off, if you were introducing yourself to someone who was new to your writing, how would you introduce yourself, and how would you describe your journey to becoming the storyteller that you are today?

Sharyn: Well, my ancestors settled western North Carolina, where western North Carolina included Tennessee, back in 1790. I had two ancestors who fought in the American Revolution, and they stayed there in western North Carolina and became preachers and teachers. My father got out of North Carolina, out of the hills, to go to World War II. I wasn’t born up in the mountains because by then, he had settled on the coast of North Carolina.

I grew up with one parent who was a southern belle from the coast, so if you want to understand her, you can rent Steel Magnolias. My father was one of the mountaineers, and I still say to this day that if you want to understand the mountaineers of Appalachia, the movie that you should rent is Braveheart, because that’s who settled here. The people who went to the mountains instead of staying on the coast were the Scots, the Irish, the Welsh, and the Cornishmen. That split between the English and the Celts that fueled Braveheart that you saw there in Scotland carried over to this country. That’s where you get the hillbilly stereotypes and all that stuff. Those are those English people in the flatlands who haven’t gotten along with the Scots and the Irish for the last thousand years.

So I grew up in a mixed marriage, because my mother was one of those flatland English people, and my father was a Scot from the mountains. It was kind of like an atmosphere of Ernest Tubb meets Debussy. I grew up thinking that culture was optional. Whichever parent I imitated, the other one thought it was hilarious. I grew up as an outsider, which is what you need to be to be a writer. You look, as an outsider, at cultures. When I got old enough … My first novels, which were written when I was in grad school, were light, funny books that had been called Jane Austen with an attitude.

When I finished the master’s degree and got the children out of diapers and was ready to write serious books, I had a choice between two cultures: my father’s culture and my mother’s culture. I chose my father’s because all the good stories were in the mountains. I’m primarily known, then, for writing the Ballad novels, which are a series of books set somewhere in the central-southern mountains from West Virginia down to north Georgia, and they deal with the history and the folklore of the mountain south

.

Luke: The Ballad novels are how I discovered you. I thought that was such a great idea, exploring the stories behind these ballads that are stories set to music. How did that idea occur to you to mine that tradition?

Sharyn: Well, music was an important part of my family, although I could make a good living getting paid not to sing. My father’s uncles all played guitar and mandolin and fiddle and so on and knew those ballads. In fact, an epiphany in my life, I guess, was back when I was in college. When I was in college, folk music was at the forefront of American culture. This was the era of Joan Baez and Peter, Paul, and Mary and Judy Collins. In lieu of going to some of the more tedious classes at UNC-Chapel Hill, I went to the pawn shop and bought a $10 guitar and learned to play about five chords. With five chords on a guitar, you can play at least 500 folk songs really badly. When Thanksgiving rolled around, I went home to wow my father, the Tennessee mountain boy, with this new skill that his tuition money was making possible.

After Thanksgiving dinner, I hauled him into the living room and sat him down and started playing this new song that I had just learned from my Joan Baez recording that I had bought at the Record Bar in Chapel Hill. It was the very latest thing in college music. I started playing this song, and my father joined in. He was a little Ernest Tubb on the tune, but he was letter perfect on the words, and I was horrified. I said, “How do you know this song? This is what the cool people are singing in Chapel Hill.” My father said, “Oh, that song, that’s John Riley. I had that song from my grandfather, and he had it from his grandfather.” After the holidays, I went back to college and looked at the liner notes on my album, and it said this song is a Child ballad from the 1600s in the north of England and the borders of Scotland and had been collected by Francis Child. It’s a Child ballad.

See, my father had had that song from when the people from Yorkshire that he’s descended from came over in the 1700s and settled those mountains and passed that song down from parent to child for 200 years. I went to the Record Bar and paid $6.98 for it. Doesn’t that tell you how fragile culture is? You’re the only link between the past and the future, and if you don’t pass something on, there’s a very good chance it could be lost. That focused me on the ballads. The ballads were, for me, a link to the past and to my own family’s past. Also, from the point of view of a novelist, songs, and even country songs today, are three-minute novels. When I teach writers’ workshops, I will bring in things like Midnight in Montgomery by Alan Jackson and play it and say, “That’s a three-minute novel.” The whole story’s there. There’s a lot of those.

From the point of view of a novelist, you’ve got songs which tell a story, and there are no boring minimalist ballads. There’s nothing about not much happened to people you don’t like anyway or the angst of a middle-class man in the suburb. They don’t write songs about that. They write songs in which something happens. I think the philosophy of the Scots-Irish is if nothing happens, shut up. That’s that feeling that I wanted to capture in the Ballad novels, that there’s a life and death situation happening and that it is archtypical, that these people are larger than life. A lot of them have songs written about them, which certainly makes you larger than life. Tom Dooley, who was hanged for murder in 1868 in North Carolina. Hang down your head, Tom Dooley. Hearing that song, I decided to look into the story and discovered that if you know the song by the Kingston Trio, hang down your head, Tom Dooley, you have to be reprogrammed, because everything they told you is wrong.

It took me two years to research that song, going back to trial transcripts and birth certificates and local maps just to figure out what really happened. I did that with Frankie Silver, who was the first woman hanged for murder in the state of North Carolina. People had gone for 150 years assuming that she did it because she was executed. The first time I heard that story, I knew she didn’t, because she was 18 years old and her husband was killed and dismembered. As soon as they told me that and told me she was 18, I said, “Who did it?” They said, “Oh, no, she was convicted. She was executed.” I said, “There has never been a case of a woman younger than 35 dismembering a body. It has never happened. Who did it?” Took me four years to figure out what happened, but I started out knowing that fact. Google away. There has never been a dismemberment by a woman of 18.

Luke: You knew what you were looking for when you were digging into that one.

Sharyn: Yes. Yes. One of my mottos is, from Louis Pasteur, the French scientist, he said, “Chance favors the prepared mind.” The more you know, the more connections you can make, and the more substance you can put into whatever you talk about. I read everything. If there’s nothing else, I’ll read cereal boxes. If you read geology and history and criminology, many different countries, and sociology and mining/engineering, you never know when one of those things is going to trip into whatever you’re looking at. The Unquiet Grave, that story, the new book that’s out, that story has always been told as a folk tale.

Luke: Do you recall the very first time you heard it?

Sharyn: Oh, I was grown, because I grew up in North Carolina and this story happened in West Virginia. I live about 70 miles from where it happened right now. That’s where our farm is. It takes you two hours to get there, but if they would flatten the mountain, I could be there in 45 minutes. In the middle of the town of Louisburg, there’s a historical marker that says the story of the Greenbrier Ghost. What it says on the marker is this case is the only case in America in which the testimony of a ghost convicted her killer. There it is. That’s it, on the historical marker. I’d seen that for years and years driving through there. Finally, one day, I just said, “Let me see what’s happening with that story.” I went to the Historical Society and said, “Give me everything you’ve got.” They’ve got all the records. Give me everything you’ve got on this case.

They led me into the gift shop and showed me this little ghost stories of West Virginia book with a three-page summary of the case. They said, “That’s what we got.” I thought, oh, boy. A year and a half later, I have a notebook that’s about six inches thick with documents. Then I started writing.

Luke: Wow. Was it when you saw that all that there was that little ghost story book, was that when you thought “I need to write this?”

Sharyn: Well, that’s when I got interested, but I didn’t commit to it until I got some more facts. If I were going to make it up, I could have started from anywhere, but I wanted to find out what really happened. In order to do that, I had to look into that story deeply enough to find out if there was a story there. When I discovered that one of the lawyers ended up in an insane asylum in 1930, I thought, oh, yeah, we can do this. He was my logical narrator because he was the first African American attorney to practice in southern West Virginia, and he was 29 years old when he was in that courtroom as the second sheriff of the defense. The other two lawyers in the case were both Civil War veterans, one from each side, one Union, one Confederate. Here’s this young African American attorney just watching these old bulls go at each other.

Luke: I couldn’t believe that. I’d heard the folk tale, too, but when I learned that it was the first African American attorney to practice in West Virginia that was involved in the case, I thought you couldn’t make this up. This is so many interesting characters.

Sharyn: Yeah. It was just amazing to find him.

Luke: How long did the research process take for you to unearth all of this?

Sharyn: About a year and a half, although we’re, honestly, still researching. I have a hard time letting go, because there are still things that I want to find out. The main thing is that I have found photographs of everybody in the story except Mr. Gardner, the lawyer. It’s not for lack of trying. I have written everybody I can think of to see if anybody’s got … I’ve been to archives. I’ve been to college archives and written to the Masons, because he was a Mason. State of West Virginia. Everything I can think of. BAR Association. Nobody can find a picture of him. He did not die until 1951. I have pictures of my parents from the ’30s and ’40s.

Luke: Yeah, you’d think there’d be something, with him living that long. You’ve got to think it’d be out there.

Sharyn: Yes. Yes. I’m hoping so, because the man was an attorney for 50 years, and he was an officer in the local Masonic lodge. At some point, those guys in the Masons must have put all the officers up on the steps, like people do in clubs, to take a picture of all the officers. I just don’t know what happened to it.

Luke: At what point did you realize that Mr. Gardner and Mary Jane Hester were the narrators of this story, were the ideal narrators?

Sharyn: First of all, I couldn’t use just one narrator, because Mary Jane is the one who would know everything about her daughter and the wedding and the whole personal side of the story, but she doesn’t know anything about the law, and she lives 15 miles from town on a four-acre farm. We’re not talking sophistication here. She was really good for the backstory, the emotional part, but when you got to the trial part, then you had to have somebody who knew the law. Using Mr. Gardner gave you a perfect outsider’s point of view. He is the ultimate outsider. He knows the law, but he’s sort of cold and detached and uninvolved with these people, but he knows his stuff. He’s a good lawyer. I let him talk about the life and times in the town. She speaks for the country people, and he speaks the lawyers and the more sophisticated, educated, professional people that you found in Lewisburg.

Luke: Now, when we start off the novel, he’s in the insane asylum. He’s being exposed to the beginnings of modern psychological therapy. Did you have to research that, as well, for this novel?

Sharyn: Yes. I have several friends who are psychiatrists or psychologists, and I’m accustomed to running things by him and say, “What would this do?” For the Ballad of Tom Dooley, the one person that had to be the narrator for that story was a sociopath. I read the trial transcript, and that woman was a sociopath. I had to keep feeding chapters to my psychiatrist friend. Any time that Pauline, in that book, expressed any emotion except for rage and gloating, he would make me take it out. That’s all sociopaths feel. There’s no sympathy. There’s no fear. There’s no anxiety. There’s nothing except rage when you lose and gloating when you win.

Yes, I did the same thing with Dr. Boozer. That’s the other thing in the research that isn’t finished yet. We’re trying to find where he’s buried. His death certificate tells us when he died, so does the Social Security index. He died in Westchester County, New York. We even found his great-niece, his brother’s granddaughter, and asked her where he was buried. She gave us the name of the cemetery. Well, she had two uncles, James and Thomas, and the cemetery she gave us is where Thomas is buried, but James is not there. So we checked every other cemetery in Westchester County and then down in Long Island, and we can’t find him. I think he’s in a coffee can in somebody’s garage.

Luke: You know, it sounds like just the research process for this was such an adventure in and of itself. Did you have any particular adventures that really stand out in your mind as you were looking into these people and their stories and looking for paper trails that led to them?

Sharyn: There was one. There are two things. First of all, did you notice in the first chapter, when he’s in the insane asylum, he and Dr. Boozer, Gardner and Dr. Boozer talk about the residents reporting seeing a demon with red eyes. Did you pick you on that?

Luke: I did, yeah.

Sharyn: Do you know who that is?

Luke: No.

Sharyn: Neither did my editor. She said, “Okay, you’re going to have to explain to people about this demon with the red eyes,” and I said, “Well, really, I don’t, because it’s an insane asylum, and if you want to think it’s a hallucination, that’s okay.” If you’d like to know who he really is, that insane asylum was located north of Point Pleasant, West Virginia, right on the Ohio River.

Luke: Oh, okay, I know where you’re going with this.

Sharyn: Yeah. Just keeping renting Richard Geer movies until you find him.

Luke: I love it! That’s a little Easter egg in the book there.

Sharyn: The other adventure was one that Sandra had, because Sandra was looking at all these documents. The chief witness against Trout, besides Mary Jane, was the young man who found the body. In the folk tales, they talk about the fact that his mother was a widow and he was her only child. We looked in the census records and so on. He’s got five brothers and sisters, and his father’s still alive. We thought what’s up with that? So Sandra keeps digging. Remember, the trial was in June and early July of 1897. At that point, he had five brothers and sisters, and his father was right there in the house. Sandra called me after doing some more research and said, “I think I have uncovered a tragedy.”

I wrote that in one of the last scenes of the book, when Mr. Gardner runs into the boy’s mother in the courthouse and invites her to his wedding, which was going to be on Christmas day, which it really was. She says, “You don’t know, do you?” What happened was between the time that the trial happened and the time that he saw her in December in the courthouse, everybody else in the family had died except for her and Anderson, Joan’s son. They got typhoid. One would linger for two weeks or so, and then another one would come down with it. By the time he got to December, the father and the brothers and sisters are gone.

Luke: Wow.

Sharyn: I know. They didn’t even get mentioned in the folk tales. They just said, okay, the mother was a widow. By then, we had gotten to know her, too. I really felt this, because these people are all real, and sometimes I think of myself as a speaker for the dead. There are people who slipped through the cracks in history. They don’t get their stories told. They’re forgotten. I find these people, like Frankie Silver, who was hanged for murder at the age of 19, or Mr. Gardner, who practiced law and we can’t even find a picture of him 50 years after he died. As a speaker for the dead, I ask them what do you want me to tell people about you? If you had a chance, what would you say?

Luke: That’s so true. I feel like oftentimes, folk tales really are all that remain of the history of these people that … I guess, for lack of a better term, the common folk that weren’t operating on a big political level or something like that. So often, the folktales get it wrong.

Sharyn: Yes. King’s Mountain is the book I wrote about the American Revolution in which a bunch of farmers who were not even members of the Continental Army, they were just farmers, got a threatening letter from a British officer saying that if they didn’t stay out of war, he was going to come up there and burn their homes and kill their families. They all got together and took the muskets down off the mantelpiece and went looking for him. The way that they found him was that there was a guy with him who could do what we would consider a Gomer Pyle act or Forrest Gump. He pretended to be a simpleton, so people just ignored him, and they talked around him as if he were not there. He was picking up all kinds of military secrets, because everybody thinks the idiot won’t get it.

He goes straight back to the patriots and tells them the location of that British regiment and so on. Because of him, they won the battle, because they were prepared. They knew what they were doing. They knew where the troops were. This guy was killed in the battle. He was one of the very few patriots that were killed. He’s not in the history books. He doesn’t have any descendants. Nobody remembers him. Never a biography. Of course, no diary or any memorial of him at all. I gave him a part in King’s Mountain because he deserved to be remembered.

Luke: An unsung hero.

Sharyn: Yes.

Luke: How do you think we benefit when we learn the stories of these people that have been lost to history?

Sharyn: I think one of the things is I’ve long ago gotten tired of the whole hillbilly stereotype thing, very tired of it. I think, in writing these stories, I can bring these people to life, not in a demeaning way. They’re smart. They’re capable. Thomas Jefferson said that the Battle of King’s Mountain was the turning point of the American Revolution, and that was a bunch of guys from east Tennessee and western North Carolina. That was the traditional, quote, “hillbillies,” but they saved the war when George Washington was losing it. In that battle, for example, at King’s Mountain, the following people were there: the first governor of Tennessee, the first governor of Kentucky, the brother-in-law of the governor of Virginia, Davy Crockett’s father, Robert E. Lee’s father, and the grandfather of North Carolina’s Civil War governor Zebulon Vance. All in that one battle. Somebody’s got to do counterpoint for things like the Dukes of Hazzard. I mean, there are people out there who are smart and noble and brave, and they’re just getting ignored. I’m very happy when my books get studied in colleges, and especially in high schools because the kids in this region need to hear about this.

Luke: Well, Sharyn, it has been a real pleasure talking to you. Thanks so much for doing this.

Sharyn: Well, thank you. It’s nice to meet you.

Sharyn brings her signature magic and historical accuracy to this fascinating story in The Unquiet Grave. It’s one of my favorite books so far this year. You can pick up a copy here.

The post The Unquiet Grave: An Interview With Author Sharyn McCrumb appeared first on The Weekly Holler.

September 5, 2017

An Appalachian Panther Tale

For thousands of years, the Appalachia mountains were home to cougars, also known as mountain lions, pumas, painters or panthers. Many tales exist of early settlers witnessing panthers drop from tree limbs onto unsuspecting victims. Their cries were said to sound like a wailing woman and struck fear into the hearts of frontier settlers.

The last confirmed eastern panther was killed in 1938. They were declared extinct in 2011, although a genetic study conducted in 2000, is leading many biologists to believe that there is no real difference between the Western and Eastern branches of the cougar family.

In spite of this, cougars sightings are reported every year in the states east of the Mississippi River. I myself saw one in 2016 while driving up Spruce Knob in West Virginia. It’s unclear whether these cats are undocumented remnants of the eastern population, wanderers from the western states, or cougars that have escaped from captivity.

Without a doubt, the memory of cougars is still strong in Appalachian history and folklore, particularly cats known as “black painters.” George Barr, a reader of The Weekly Holler from Denver, North Carolina, recently contacted me to share a panther-themed folktale his grandfather used to tell. The story was so good, I called George to learn more.

“There were 11 of us cousins, and I wrote it down before it got lost. And I’m not sure where it originated. My grandfather, Pappy, was the son of minister who had postings around various places, and I think his father probably originated that story, although I’m not certain of that.”

“So what about your grandfather then, what can you tell me about him, and maybe what you remember it being like hearing this story from him?”

“My grandfather was a civil engineer, but he loved farming. And then he had a chance to buy a farm, it’s called Barrsden, and it was about 240 acres. Originally it was slave quarters for a plantation that was about a quarter of a mile away. He had taken these slave quarters and had winched some of them around with big tripods and mules, and then he built this big rambling farmhouse between all of these things that had been strategically situated. So there could be a gaggle of us, sometimes Easter dinner might be 50 people, and he had a dining room big enough to handle it.”

“So Pappy, he liked his bourbon, and he smoked. I think he smoked from, I don’t know, probably 15 years old, or thereabouts, up to I think he was about 70 when he quit. But he had a real growl, an honest growl to his voice.

This was mostly in summer time, I don’t think he ever told it in the house, we were always outside. And he’d be sitting in sort of a swing-backed hammock chair and the rest of us would be sitting on the ground in front of him. And he didn’t have any notes or anything, he just went into it, and lit into it, and really brought it alive! It was fun to listen to even if we knew the whole thing. Not to mention that Pappy was just beloved by all of us.

So the story, it always started out really innocuously, then kind of worked its way into the deep dark wood. You know, even then ones of us who had heard it before couldn’t help but get the hairs standing up on end, and gooseflesh. We weren’t out in the woods, we were in a mostly open farm. But there was plenty of wildlife around, so whether it was owls, or sometimes we’d hear a bobcat screeching, just all those night noises, you know. And it never failed to delight. it just was one of those traditions that we looked forward too. We’d just pester him something fierce to tell us that story, and he’d usually demur, but then he got the right audience together, and the night was just right, and he’d sit down and tell us the story.

I’m sure that I’m not match for Pappy’s storytelling, but I’m honored to take a crack at sharing his legendary tale with you. So gather ‘round the fire, and huddle close, here is the story of Taie Todla:

Once upon a time, there was a young boy by the name of Billy Gumboil. During the school year, Billy went to school in the city with all of his friends, but in the summers he lived in a little town in the country. There weren’t many kids in Billy’s town, so you can imagine that he felt lonely sometimes, and when he felt lonely, he always started thinking about his best friend from school, Willy Snodgrass, who lived even further out in the sticks than Billy did. One day during the summer, while he was running errands for his mother, Billy was struck by a bout of loneliness, and he decided that this time he was going to do something about it. No more moping around town for Billy, he was going to visit his buddy Willy Snodgrass.

Later that evening, Billy told his parents about his plans and they agreed that he was old enough to make a trip to visit his friend. So, Billy wrote a letter to Willy Snodgrass to see if a visit was convenient. About a week later, he received a letter from Willy inviting him to visit. In the letter, Willy drew two maps for Billy, detailing the two routes he could take. The first route was the long way, on a road which meant a pleasant but a tiring all day ride through beautiful rolling hills, where Billy could see the farmers at work and smell the good smells of the countryside. The second route was shorter, but it went through the heart of a deep dark forest. The route would be cooler in the summer and took less time, but the forest was known to be full of wild animals. It was rumored that a black panther haunted those parts. Billy was afraid that travel through the forest could be dangerous, even his parents’ eyes grew wide when he mentioned it, so he decided he would take the long way. Early the next morning, just at dawn, Billy put some lunch and a change of clothes into his saddle bags and saddled his horse to go. He kissed his parents goodbye and set off to see Willy Snodgrass with time to get there just before dark.

Just as Billy was leaving town, his horse threw a shoe. So Billy stopped at the village blacksmith to get the horse shod. He told Robin, the blacksmith, where he was going. Robin raised his eyebrows and said that Billy was traveling to wild parts indeed. The blacksmith reached into the pocket of his leather apron and gave Billy a curious stone on a sling to carry for good luck. After Robin was through shoeing the horse, Billy climbed into his saddle and began to ride off. Robin called after Billy, telling him that if he met a black panther in his travels, he need only twirl the sling around over his head three times and say, “One, two, three, Robin knows me.” Billy thought that this was a little odd, but he thanked Robin and went on his way.

Around sundown, Billy arrived at the Snodgrass’s house; he found Willy eagerly awaiting him, along with the rest of the Snodgrass family. They had eaten supper, but they had saved him some fried chicken and biscuits for Billy to eat before he went to bed, exhausted from his journey. Billy was so tired that he hardly noticed how strange Willy’s family appeared, although he did think that they seemed somewhat peculiar. During the night he heard the most curious noises during his sleep, funny squeaking, and chattering noises, as though someone was making quite a fuss over him in a language which wasn’t quite familiar. He awoke in the morning a little later than usual, but still in time for breakfast, so he washed up and went downstairs. And sure enough, what he hadn’t noticed in the dim light of evening and in his tired state was that all of the Snodgrass family except Willy were part monkey! Just as Robin had said, these were wild parts indeed! Billy was quite unnerved, but being the polite young lad that he was, he attempted to appear as though nothing was unusual. He suspected that the Snodgrass family didn’t get much company, and he was determined to be a good guest.

Willy’s sister was quite hideous, as her monkey-ness showed mostly in her face. Willy had a hard time to keep from grimacing as she grimaced constantly across the breakfast table from him. Willy’s mother was as nice as she could be, but her fingers were as monkeylike as could be, and Billy worried that the eternal picking she was doing was getting hair and who knew what else into the food. But the funniest feeling came when a long, furry thing curled around Billy’s neck and slid down to his plate where it picked up a biscuit and returned it to Mr. Snodgrass’s mouth! It was Mr. Snodgrass’s long monkey tail! Well, Billy barely made it through breakfast with his senses, he even found himself missing his own town. They finally finished the meal, and everyone helped clean up. Mr. Snodgrass’s tail was handy for carrying extra dishes, and the work went quickly. Billy went outside with Willy to ride an old lopsided bicycle and to while away the morning playing. When lunchtime came, Billy dreaded the thought of another meal around the table with this odd family, but he stayed as though nothing was wrong, since he was so polite. But after another meal of grimacing faces, picking hands and curling tails, he knew he must bid his farewell before the next meal and before nightfall meant he would spend another night there. So, with apologies to Willy’s family that his visit was so short, and with a farewell to his friend Willy until the start of school, Billy saddled up his horse and rode off toward home. In the distance, he could see Mr. Snodgrass waving goodbye with his kerchief held in his tail, and Mrs. Snodgrass was waving her kerchief from her picking fingers, and Willy and his sister were simply waving and making some little chattering noises.

This time Billy had gotten a late start in his journey. He could ride the road he had come, sleep under the stars, and continue his journey tomorrow, or he could ride the short route through the deep dark forest and be home in time to sleep in his own soft, warm bed. By the time Billy arrived at the entrance to the wood, he had decided to take the short way home. After all, he could rely on the speed of his trusty horse. When Billy entered the wood, he noticed that what had once been a road was now barely a path; no one had traveled this way for a long time. The trees had overgrown the roadway, so that there was a natural cover which blocked most of the daylight almost immediately. And the deeper he went into the wood, the darker it became. Billy’s horse pricked up its ears as they went, it snorted, shivered, and rolled its eyes as if to say that it liked the other route better.

Billy urged his horse along the gloomy trail. They rode into the heart of the forest, and Billy thought he heard a faint sound in the distance, his horse’s ears pricked up again. Billy listened carefully, and through the other woodland sounds he could make out something that sounded like,” te, te, tl, tl, tl, la…”

They pressed on, and Billy’s horse became more skittish, its nostrils flaring and eyes rolling wildly. Again, Billy heard the strange sound, clearer now, it had grown closer. “Taie ah, taie ah, todle lodle, todle lodle, todle lodle la…”

Billy’s mount snorted, and his flanks quivered. Billy tried to swallow the lump in his throat and encouraged the horse to step up his pace once again to a fast trot. Without warning, they heard the strange growl again, even closer now, “Taie Ah, Taie Ah, Todle Lodle, Todle Lodle, Todle Lodle Ah…”