Tiago Forte's Blog

November 10, 2025

The Book I’ve Been Waiting to Write for 15 Years

I’m incredibly proud to share news that’s been two years in the making: my next book is coming in Fall 2026!

It’s called Life in Perspective, and it represents the culmination of a reflective practice I’ve been refining since 2008: the annual review.

If you’ve read Building a Second Brain or The PARA Method, you know I’m passionate about systems that help us manage information and act on it. But I’ve come to realize we’ve been solving only half the equation.

We’ve gotten incredibly good at capturing information as it arrives. But we’re terrible at revisiting and making sense of what we’ve accumulated after time has passed.

That’s what annual reviews are for. And the timing has never been more critical.

Why this matters nowWe’ve spent the last few decades in what I call the Attention Era—a unique period in history in which human attention became the scarcest resource, and thus the most valuable.

Every hour of every day has been transformed into a unit of consumption. Our attention is bought and sold by the second, fragmenting our mind into tiny pieces so that it can be monetized more efficiently.

But I believe we’re reaching the end of the Attention Era, because we’ve fully exploited that scarce resource. The average person now checks their phone 96 times per day—once every 10 minutes. There are simply no more pockets of attention left to harvest.

What’s scarce now isn’t what we notice, but how we make sense of it and put it in context. The new currency of our age is perspective, and we are entering what I call the Perspective Era.

Unlike attention, perspective cannot be harvested or extracted by outside forces. It can only be cultivated.

And the annual review is the most powerful tool I’ve ever found for doing so.

A life-and-death lesson on the power of perspectiveLet me tell you how I discovered this practice, because it didn’t start with productivity optimization or goal-setting frameworks. It started with a gun pointed at my chest.

I was 23, studying abroad in Brazil and living in one of Rio’s favelas, where I taught English at a small nonprofit. I’d pulled out my camera to film my street when a man named Chucky – a local drug trafficker – pressed his assault rifle into my chest and accused me of being a police informant. He marched me up the hill to his headquarters while I tried to explain, in broken Portuguese, that I was just a volunteer teacher who’d been filming memories.

After what felt like an eternity, his leader let me go. But the encounter shattered something inside me. I couldn’t stop thinking: What am I doing with the time I have? Am I willing to continue following a path I haven’t chosen for myself, knowing it could all end at any moment?

A few weeks later, on New Year’s Day 2009, I sat on a Brazilian beach at dawn with a notebook. I had no idea what I was doing—I’d never read a self-help book or heard of SMART goals. I just knew I needed to see my life differently.

I started by listing everything I was grateful for from the past year. The first few items came slowly. Then the memories started flowing: teaching English to rowdy twelve-year-olds, dancing at Carnival until my feet ached, starting my first blog, the moment I realized I could make people laugh in Portuguese.

By the time I finished, I had pages full of specific, vivid memories. The picture they painted was of an unforgettable year I couldn’t help but feel proud of. As I set down my pen, I felt something shift physically inside me—the knot of existential terror that had been simmering there for weeks began to loosen.

When I turned to my goals for the new year, I suddenly saw them from a completely different perspective. I noticed something in what I’d written: I was happiest when traveling, teaching, and learning. That one insight – so small, yet so clear – made everything click into place for the next chapter of my life.

That was the moment the course of my life changed. Not because the obstacles had changed, but because I had.

I didn’t know it at the time, but I had just completed my first annual review.

The missing link in your knowledge systemOver the years, I’ve realized that the annual review (along with other reviews at other timescales such as quarterly, monthly, and weekly) is the fifth step in the CODE knowledge management cycle I’ve taught for years:

Capture: Getting information into your systemOrganize: Structuring it for retrievalDistill: Extracting the essenceExpress: Creating value for ourselves and othersReview: Reactivating and reframing our accumulated knowledgeWithout that final step, we’re like computers with infinite storage but no RAM. That is, we can remember everything, but can’t turn any of it into awareness or wisdom.

Think about how much happens in a single year of your life. Thousands of experiences. Hundreds of insights and lessons. Dozens of meaningful relationships and projects.

Without a systematic review process, 99% of that value is lost.

An annual review isn’t just reflection for reflection’s sake. It’s a memory technology—a way to compress a year’s worth of experiences into accessible insights, preserve important memories before they fade, reorient yourself in the arc of time, and build agency over your past so you can consciously shape your future.

And it compounds over time. Your third annual review is exponentially more valuable than your first because you’re pattern-matching across multiple years of consciously processed experience.

The ARC Method: A practical process that worksIn Life in Perspective, I’ll guide you through the complete framework I’ve developed over 15+ years of practice and teaching this to over 1,000 students. I call it the ARC Method—three stages that correspond to past, present, and future:

Appreciate the Past: You’ll spend 1-2 hours gathering what was good about your year. Not in vague generalities (“I’m grateful for my family”), but in vivid, specific details that bring memories back to life. You’ll scroll through photos, review your calendar, collect artifacts—anything that helps you remember what actually happened versus what you think you remember.

Reflect on the Present: Next, you’ll spend 1-2 hours looking for patterns in what you’ve gathered. Which memories still move you? What themes keep appearing? This is when you notice the bodily sensations—the quickening breath, the tightness in your chest, the sense of expansion—that reveal what matters at a level deeper than the intellect. You’re not analyzing; you’re listening to your intuition.

Create the Future: Finally, you’ll spend 1-2 hours deciding what you want to create next. But unlike typical goal-setting that starts with what you should do, this emerges naturally from what you’ve discovered about who you truly are and what genuinely enlivens you. You’re not starting from scratch – you’re building on what already exists and what’s worked in the past.

This isn’t about perfectly following a rigid checklist. It’s a flexible toolkit you draw from based on your needs. Some years, you might spend most of your time on gratitude and excavating the past. In other years, you’ll focus on identifying patterns in the present. The process pulls you forward based on what captures your curiosity, rather than requiring you to force yourself through it.

What makes this differentIf you’ve tried annual reviews before and found them draining or daunting, I understand why. Most approaches to structured reflection are built on assumptions that work against human nature.

The typical annual review asks you to analyze what went wrong, identify your failures, and rationally construct goals based on where you fell short. It’s an audit, not an exploration. A diagnosis of deficits, not a celebration of what has been and what’s possible.

The approach I’m taking in Life in Perspective contradicts that conventional approach in several fundamental ways:

It starts with what worked, not what didn’t. When you begin by looking for problems, you’ll find them…and miss the subtle patterns of what’s currently working well in your life. The most valuable insights don’t come from analyzing your failures; they come from noticing what makes you come alive and doubling down on that.

It trusts your body’s wisdom, not just your analytical mind. Your intellect can rationalize anything, but your body knows the truth. It is physical sensations that reveal what matters in the long term. Smart, achievement-oriented people especially need this, because we’re trained to override our intuition with analysis.

It treats annual reflection as a sacred ritual, not an optimization exercise. This should feel like hiking your favorite trail in deep conversation with your best friend, not suffering through a performance review with a tyrannical boss. When something is genuinely enjoyable, you don’t need willpower to sustain it. You can’t compete with someone who’s having fun, and there’s no reason this practice can’t be fun!

It anchors you in the natural rhythm of years, not the tyranny of daily habits. While productivity culture obsesses over morning routines and daily tracking, I’m more focused on how humans experience the long arc of time—through seasons, cycles, and the earth’s rotation around the sun. What happens annually guides and shapes what happens daily, and that reality has been underappreciated in most self-improvement literature.

My book will teach the specific principles and practices that make an annual review work, that make it feasible and sustainable, and that allow you to squeeze as much value as possible out of the practice.

Why I had to write thisI’ve been practicing annual reviews since 2008. Since 2019, I’ve published mine openly on my blog – among my most popular content. I’ve taught The Annual Review workshop every year since 2019 to over 1,000 students from around the world.

The results I’ve seen from doing so have been nothing short of remarkable, rivaling any other method or technique I’ve ever encountered. I’ve seen my students discover unprocessed grief they finally had the courage to face. They’ve committed to long-postponed dreams and signed their first clients within weeks. They’ve identified recurring patterns that needed deeper self-understanding, not just willpower.

But beyond the credentials, I know this works because completing an annual review remains the single most important project I undertake every year. The success of everything else hinges on the depth of honesty I’m able to reach in my reviews. They’ve become even more critical since becoming a father—my ability to be present and loving with my family depends on the overall balance I maintain across all areas of life.

Most importantly, even if there were no external benefits whatsoever, my reviews rank among the most fun and meaningful experiences of my life. They’re a priceless chance to appreciate what’s happened over the past year of my life, which is so easy to miss as the months blur together.

A technology for becomingAs AI handles more of our analytical and routine tasks, the value is shifting to what only we can do: make meaning from our unique experiences.

Your annual review becomes a deep well of accumulated wisdom that no AI can replicate. It’s your personal system for sense-making, fueled by the raw material of your life.

I call this building “temporal agency”—the ability to consciously shape your relationship with time, memory, and your personal evolution.

If you’ve ever felt like:

You’re moving fast, but not sure you’re going in the right directionYou keep making the same mistakes despite having all the “right” informationYour Second Brain is full, but somehow not helping you growYou want to be more intentional about your life choices and prioritiesThis book is for you.

Annual reviews aren’t just another productivity technique. They’re a technology for becoming who you’re capable of becoming, by finally learning from who you’ve been.

It took a brush with death to wake me up and give me a new perspective on my life nearly 20 years ago. I still have that notebook from the Brazilian beach, its pages yellowed and curling, reminding me of time’s relentless passage.

But you don’t need a near-death experience to access that same transformation. You just need a few hours, a notebook, and the willingness to see yourself clearly.

I can’t wait to share this experience with you.

The post The Book I’ve Been Waiting to Write for 15 Years appeared first on Forte Labs.

November 3, 2025

What I’ve Learned From 20 Years of Goal-Setting

In the summer of 2005, when I was 20 years old, I sat down and wrote one of my first personal goals:

“Hold a position in the Associated Student Government of Saddleback College at start of Fall semester (August 22, 2005).”

I had just dropped out of college on the East Coast after burning through all my college savings in one year. I’d moved back in with my parents in shame and enrolled in a local community college to try and get my life back on track. Writing down this goal was my first tentative attempt at regaining a sense of control and agency.

I can remember it like it was yesterday – how daunting it felt to commit to this goal, despite the fact that the position was uncontested and there were no real barriers to my winning it in the upcoming student government elections!

Even such a small, easy commitment required me to confront limiting beliefs: that I wasn’t good with numbers or with money. Even entertaining such a small amount of ambition meant I had to shift my identity, since I didn’t remotely see myself as a leader.

I’m happy to say that I persevered through those fears, took on the position successfully, and it ended up being a very rewarding part of my college career. More importantly, it was the inception of my relationship with goals.

Reveling in this first small victory, I soon after decided to write down a series of other goals I had for myself – for the GPA I would attain, for the girlfriend I wanted, and for the 4-year college I wanted to transfer to.

I discovered SMART goals around that time, and decided to attach a target completion date to each of them. Looking back at that list, the furthest date I assigned to my most ambitious goal was in 2025, when I would turn 40 years old. At the fresh-faced age of 20, I couldn’t fathom being any older than that. It was the farthest my imagination could reach.

Now that I’ve arrived at that seemingly distant horizon, I want to revisit not only that first batch of goals, but all the goals I’ve formulated for myself in the 20 years since. I’m less interested in which ones I accomplished or didn’t, and more interested in what I discovered and who I became by aiming for them in the first place.

Let me take you on a retrospective journey through 20 years of goal-setting to find out what I learned.

Building the foundation of adulthoodLooking at the list of outcomes I said I wanted in the earliest days, I can see that I was struggling and striving to build the foundation of my adult life.

Some goals had to do with seemingly small projects, such as creating a website to promote my first business, fixing people’s home computers:

“Build a professional, full-featured website for Forte Computer Solutions by beginning of Spring semester (January 14, 2006).”

I remember I didn’t succeed because there were no user-friendly website builders at the time, and I didn’t have enough motivation to learn HTML. But it was my first personal experience with the challenge of building things with technology, a subject I’m still grappling with today.

Some goals had to do with deep mindset shifts I underwent, such as diving into the world of Robert Kiyosaki’s book Rich Dad, Poor Dad:

“Complete Rich Dad’s curriculum: read and take notes on all Rich Dad books, master Cashflow 101 and 202, and read all books recommended by Robert Kiyosaki by end of Spring semester (May 20, 2007).”

I’d been raised by artists, and as useful as that was for my creative integrity, it didn’t give me any of the financial or business skills I needed. I spent over a year completely immersed, reading all Kiyosaki’s books, and many others he recommended, and even purchasing his financial education board game and playing it with my friends and family.

Looking back, I can see how fundamental that experience was for giving me an abundance mentality toward money – that it could be reliably earned, leveraged, multiplied, and compounded, and in a creative and values-aligned way.

Other goals seemed quite random and incidental at the time, such as getting my first English teaching job in Curitiba, Brazil, where I was studying abroad:

“Get a job teaching English at an established school in Curitiba by end of March 2008.”

Yet I now realize that experience opened up the door to my entire career in education. I see repeated evidence that some of the biggest endeavors in my life started so small.

Other projects were clearly massive from the start, and I have no idea what I was thinking taking on something so ambitious:

“Write Beyond the Orange Curtain and have it published by New Year (January 1, 2011).”

That was my first book, and I took every conceivable shortcut I could find to make it real. The chapters of the book were just unedited posts from my travel blog. I used a service called Blurb to design the front and back covers on my computer, and uploaded it to Kindle Direct Publishing. I remember I couldn’t bring myself to charge anyone for it, so instead I made it a fundraiser and donated all the proceeds to charity.

Fast-forwarding a couple of years to the start of my career, my goals started involving higher stakes. I began making real decisions about where my life would lead, with irreversible tradeoffs.

Kicking off my professional careerI returned to the U.S. from my service in the Peace Corps in December 2011, and immediately dedicated myself to finding a job in San Francisco:

“Get a job in the technology or non-profit sector and move to San Francisco by April 30, 2012.”

A few months later, I found myself in that city interviewing for the two jobs I’d received offers for: a junior analyst job at a French consulting firm called Fabernovel, and a role on the fundraising team at the Wikimedia Foundation (which manages Wikipedia, among other projects).

These paths couldn’t have been more different: the former represented a sharp turn into the world of business and technology, while the latter would have continued my current trajectory deeper into the world of non-profits. But I was already wary of the non-profit world. I’d spent much of my 20s in it, and seen a lot of dysfunction, politics, and waste. I decided I wanted to try something new and accepted the consulting job.

At that point, I notice a gap in my running list of goals, and I think it was because for the 18 months I worked at the consulting firm, I wasn’t responsible for choosing my own goals. They were assigned to me, in line with the broader goals of the company. That was useful, to see what it felt like for my personal goals to be subsumed into a wider mission.

I see my own agency emerge again in early 2013, as I started thinking about leaving consulting. I wanted to work on technology more directly, and started planning how I would apply to a tech company like Google, Coursera, Evernote, Udemy, Autodesk, Uber, IDEO, or Tesla.

I had no real technical skills, however, and knew I would need a stellar resume to have any chance. I signed up for a Squarespace account and built my own website, with a portfolio showcasing my credentials and accomplishments:

“Publish an online professional portfolio with documented evidence of my accomplishments, in a beautifully designed format by July 1, 2013.”

That ended up not being nearly enough, and I failed to secure even one interview for any of the roles I applied for at those companies.

A few months later, in June 2013, after yet another long night at the office banging my head on the keyboard and getting nowhere, I decided to call it quits. I was working too hard, for too little pay, and with too little control of my destiny. I would rather take my chances on my own.

Embarking on the journey of self-employmentAs soon as my two weeks’ notice was up, I turned my portfolio website into a business website and threw myself into trying to make money any way I could think of.

I worked at random events, helped my friends with their projects as a subcontractor, and made my first online course on the GTD productivity method. That course ended up being an unexpected hit, and paid the bills for a while:

“Launch GSD.LAB on Skillshare and get 1,000 paying students signed up by Jan. 1, 2014.”

With a bit of financial breathing room, I had some freedom to experiment, and experiment I did. Looking back, I can see that many of the seeds of my future endeavors were planted around this time as seemingly low-stakes experiments.

I volunteered to give a talk at a local Quantified Self meetup, which introduced me to the subculture of people using technology for personal development in a systematic way:

“Create and deliver an inspiring, moving, cutting edge talk on my QS experiments for the QS SV Meetup on Nov. 18, 2013.”

The Quantified Self community ended up being my gateway to an adjacent field – personal knowledge management – that would become my main focus in the ensuing years. That talk actually took place at the Evernote headquarters in Redwood City, foreshadowing my relationship with the platform that would be my tool of choice for building my “second brain.”

After the lucky success of my first online course, I found it very difficult to continue making that income stream work sustainably. It was too hard to build the following I knew I needed, while also creating more courses and other products, while also doing everything else involved in running a business. I saw the potential of that career path, but wasn’t ready for it, so I turned to corporate training at the invitation of a mentor:

“Sign a major corporate training contract for productivity/workflow design by Apr. 1, 2014.”

Those workshops were well paid, and gave me a financial lifeline for a couple of years. More importantly, they happened infrequently, giving me lots of free time to learn new skills and pursue new interests.

Setting goals for my personal developmentThe life of a freelancer was quite uncertain and stressful, and I turned to meditation around this time as a basic survival measure after seeing an introductory book on it mentioned on an online forum one night:

“Establish a daily mindfulness meditation practice by May 31, 2014.”

That would eventually lead me to join a 10-day silent meditation retreat:

“Attend a 10-day meditation retreat by August 31, 2014.”

That experience was so profound that I felt compelled to write about it, which became my first blog post on a fledgling site called Medium. The meditation retreat was free, requiring only 10 days of my time. And yet it was a seismic shock to my psychology, kicking off two of the most significant themes that continue to define my life to this day: writing in public and my further explorations of personal growth experiences.

My next such exploration was to join a weekend seminar called the Landmark Forum, which I’d heard several friends talk about:

“Attend a Landmark Forum program by Dec. 31, 2016.”

I can still remember how daunting it felt to spend $700 of my own money on a seminar. And yet again, the return-on-investment was incalculable. I spent two years immersing myself in the world of Landmark as a result, taking a series of their other courses and seminars, culminating in their 7-month leadership program along with my then-girlfriend Lauren.

I see so many examples of how saying “yes” to something that seemed inconsequential at the time opened up entire new worlds for me. As another example, I agreed to write a series of 5 guest articles for an obscure blog I followed called Ribbonfarm. That experience was my training for writing long-form thought pieces, which would deepen my writing and thinking, attract my first consistent following, and give me exposure to a vibrant community that was the perfect testing ground for my own emerging ideas about productivity:

“Write a 5-post guest series on Ribbonfarm, laying out my vision for productivity and recruiting a smart audience by Jan. 31, 2017.”

And sometimes personal growth was less about reaching some mountain peak of experience, but about taking the time to engage in non-goal-oriented activities. I’m certain, for example, that the time I spent sailing was really important for my mental health:

“Receive Junior Skipper certification from Cal Sailing Club by August 31, 2015.”

I turned to sailing in 2015 when I needed an outlet that had nothing to do with my work, gave me exercise and exposure to nature, and helped me make new friends. The Cal Sailing Club operating out of the Berkeley Marina was my lifeline in all those respects, and I’m so grateful I set aside the time from my professional pursuits to learn to sail there.

The rise of Building a Second BrainAs I saw my ideas start to gain traction, an earlier vision returned: of creating an independent career of reading, researching, writing, and teaching, like a freelance professor.

I remember vividly in the fall of 2016 when a new goal emerged along these lines, which was intimidating, but also the perfect synthesis of everything I’d learned over the previous few years:

“Create a new online course on digital organization and creative execution, and deliver it to 50 people at premium prices, by Feb. 28, 2017”

As I reentered the online course space, I wanted to approach it differently from the “self-paced” course model that hadn’t worked for me previously. It’s agonizing to see evidence of how long it took me to arrive at that new approach!

Like watching the main character in a movie stumble around and miss all the obvious clues, it’s all so clear with my 20/20 hindsight vision. I wrote vaguely about creating some kind of “bootcamp,” which would eventually give rise to the cohort-based course model and a whole new category of virtual education.

Around that time, I switched from single-sentence SMART goals to more narrative-style visualization that contained more detail and specificity:

“I run a regular virtual bootcamp, enrolling my most engaged followers in a high-quality, engaging, accountable learning experience using the latest ideas and tools. I have a system for updating and delivering these bootcamps with minimal recurring effort, dedicating most of my time to providing coaching, feedback, and support for their projects and businesses. This bootcamp helps me test and refine the key components of my new vision for productivity, generating testimonials, case studies, and examples for a book.”

My first small beta group ended up being only 15 people, mostly friends or acquaintances who agreed to be part of it for free, in exchange for providing their feedback. We met once a week for 4 weeks, and I recall creating the slides for each call immediately before it took place, based on the feedback from the previous one.

That feedback, thankfully, was excellent, and I went on to deliver a series of cohorts to slowly growing numbers of people, at slowly increasing prices. I can remember reaching the following goal, which finally confirmed that this was a sustainable model for me:

“Deliver BASB v3 to 80 people, generating $48k in revenue, by August 31, 2018.”

It’s astonishing to me to look back on this fledgling start and see what Building a Second Brain has become. In the 7 years since, it’s served hundreds of thousands of people via an ecosystem of books, courses, a membership, and a sea of content, created both by me and countless others. Yet it all began with a goal written down on paper.

It’s also amazing to look back on issues that once occupied a lot of bandwidth and stress, such as putting aside money for taxes and making estimated tax payments, which are now completely automated, and I don’t spend one second thinking about. Other concerns that once seemed unbelievably far in the future, such as saving for retirement, now feel much more relevant since reducing our tax burden has thankfully become our main problem!

What I learned from unfulfilled or delayed goalsI’ve recounted a succession of the goals that worked out and led to something greater, but I can also see many, many others that fizzled out, were off the mark to begin with, or would take far longer to come to fruition than I imagined.

In early 2017, I felt a desire to connect with other creators and entrepreneurs, since that lifestyle could be so solitary so much of the time. I had no idea what that could look like concretely, however, and you can see that lack of clarity in how I worded it:

“Establish a group of like-minded, ambitious, engaged people for mutual learning, accountability, community, and growth by June 30, 2017.”

That desire would persist and only grow over the years, before finally manifesting as the Wholesome Mastermind I would start 6 years later, in 2023. In retrospect, I can see that I wasn’t ready to host an event like that one until I’d reached a certain level of financial stability and gained enough of a reputation that other entrepreneurs would be willing to join.

Other goals seemed to take shape quickly, but would involve many iterations before I figured them out. In 2017, I decided to hire someone for the first time, as the BASB cohorts took off and I needed a course manager to handle the logistics:

“Establish a solid working relationship with a collaborator, significantly boosting my productivity and profitability by Dec. 31, 2017.”

I can still remember how scary that was, what an immense responsibility it felt like, and how hesitant and unclear my expectations were. I hired the first person who offered to work with me, without any semblance of a wider search. Eight years later, and after hiring probably 20 people in the interim, I’m finally starting to feel like I’ve achieved a balance of autonomy and accountability with my team.

The narrative style of goal-setting that I adopted around this time led to an unexpected side effect: it revealed a lot more detail about my mistaken assumptions around what would bring me happiness and fulfillment. The results are often insightful or funny.

In early 2014, I wrote:

“I wake up after a restful night of sleep, which was tracked by QS devices for later analysis. I record my health metrics using a smart scale, activity tracker wristband, and other QS devices.”

LOL! At this time, I was neck-deep in the Quantified Self movement and related ideas, and believed that self-optimization was the path to self-fulfillment. If only I could achieve a high enough sleep score, fitness score, productivity score, etc., then surely I’d be happy!

That optimization mindset extended to my surroundings and the products I bought:

“My chair was chosen after in-depth research and perfectly supports my spine. I’ve also studied and practiced the best sitting techniques and ergonomic positioning, and use them.”

Thankfully, not long after this period, I would realize what a dead-end self-optimization becomes after a certain point. I learned to satisfice instead: to allow most parts of life to be relaxed and somewhat “mediocre” at any given time, so I could focus my energies on a few things that truly matter.

In 2014, I invested a lot of time and money launching my second online course, on habits, which would end up being a tremendous flop:

“I am teaching an online course on behavior design, teaching newcomers how to make a plan for designing and sustaining new habits, and how to execute the plan using the best ideas, methodologies, and tools out there.”

My choice of topic was spot on, as the meteoric success of Atomic Habits a few years later would demonstrate. But in retrospect, I can see exactly what didn’t work: what I was teaching wasn’t authentic to me. I’ve never been particularly committed to habits or a routine of any kind. I don’t even really believe in them, preferring to flex and adapt my choices to how I feel. That tension, between what I was recommending and how I lived, showed up everywhere and doomed the project from the start.

But even that failure taught me a profound lesson: that I shouldn’t chase the trends or try to do what was popular. I have to follow what is authentic to me, what I’m passionate and inherently curious about, even if it seems to lead somewhere random. I still follow that principle to this day.

Goals as a means to self-knowledgeI notice in my narrative goal-setting that I had a lot of beliefs about what my work “should” look like, many of which turned out to be misconceptions.

For example, I kept returning to the idea of “one-on-one coaching,” since that has always been such a powerful trend in personal development circles in the San Francisco Bay Area. But I would eventually learn that coaching wasn’t a good fit for me, and I was much better suited to monetizing my knowledge through courses that could serve many people at once.

The same is true for public speaking. I wrote:

“I speak regularly at events and conferences around the world, using them as platforms to spread my message and impact people directly.”

And for consulting:

“I consult with the world’s most influential organizations, shaping the development of products and services that manifest human-centered design principles and what I’ve learned about human-centered work.”

I had other misconceptions around what was important in business. I put way too much emphasis on having a slick brand for Forte Labs in the early days, for example, pouring time into logos, business cards, and beautiful slides:

“The Forte Labs brand has been completely redesigned and refreshed, presenting a look and feel equal to the world’s most innovative brands. This brand is reflected in the website, all social media properties, and printed materials, providing a consistent and alluring experience with every interaction.”

With the benefit of hindsight, the brand didn’t matter at all and would only become important and clear when BASB came about.

Many of the goals I set for myself were most useful not because I successfully achieved them, but because I didn’t. They taught me what I truly wanted and didn’t want. That self-knowledge and self-awareness is far more valuable than whatever I would have gained by unquestioningly pursuing those goals to their completion.

I had so many fanciful ideas of what I thought I wanted, such as “having breakfast in a super modern, gorgeous kitchen.” It turns out that acquiring a “super modern” kitchen requires renting a super modern apartment, which is very expensive. I found that I much preferred to live in affordable places that didn’t stress me out when rent was due.

Another example is “frequent business travel,” which felt so luxurious and prestigious for a short period, until I quickly realized I wanted to avoid it at all costs.

The runway is longer than you think, but the plane can soar higher than you imagineMany goals I set for myself seemed so far out of reach, and were far out of reach! In my 2015 goal-setting, I dared to write:

“I’m generating $200,000 per year in pre-tax income.”

This felt like a totally audacious sum, and it would be 4 years until I achieved it in 2019. A couple of years later, as the pandemic fueled online business growth, our personal income would reach 7 figures, which my 2015 self could scarcely have imagined. I would give anything to travel back in time and see the look on his face as I delivered the news.

This is a case of a common phenomenon I can detect in retrospect: that many goals take longer to accomplish than I first imagined, yet once I do, their potential can greatly exceed my limited imagination. In other words, I tend to underestimate the “runway” needed for the plane to take off, but once it achieves liftoff, it can soar far higher than I can imagine.

Another example of that principle is my book advance. In 2015, I wrote:

“I have a book deal with an upfront advance of at least $50,000.”

You can sense in my language a kind of pleading tone – I really would have been happy with a book deal of any size.

It would, in fact, take me 6 years to receive the first part of that book advance, but when it came, it was $325,000, a sum that exceeded my combined income from my first 5 years of self-employment. Today, a decade after I wrote those words, I’ve made $1.85 million from the book and associated product sales, and project that number should reach $6.8 million in earnings over its lifetime. Astonishing.

It’s amusing to look back on some of my earliest goals, such as to “reach financial freedom,” which I defined as having enough passive income to meet my expenses:

“Become financially secure (passive income = expenses) by age 33 (May 4, 2018).”

I understand now that that goal was based on a misconception that work was something I should try to “escape.” From the vantage point of today, I wouldn’t want to stop working even if I had the choice to, as it’s one of my greatest sources of learning and fulfillment. And I know that the sense of security I was looking for isn’t found in a certain size bank balance, but in a holistic life of rich relationships, including a healthy relationship with risk and uncertainty.

The same is true for personal goals. Almost every year, I wrote down something along these lines:

“I perform some type of exercise every day, and vary my exercises to keep me in shape and support overall health.”

Over time, I tested out a variety of theories about health and fitness, such as Paleo-style diets, CrossFit workouts, high-protein breakfast, etc., that were making the rounds at the time. None of them ever really stuck for long.

Regular exercise has always been my “white whale,” and it is only over a decade later, in 2025, that I can say I’ve (more or less) formed that habit. I find that I’m able to do it now because I’m in a different life stage with different, more aligned motivations: not to get ripped or impress girls, but to avoid aches and pains and be more active with my children.

I see so many examples of just how long it takes many desires and intentions to come to pass. We tend to think in weeks, months, quarters, and, if we are really long-term thinkers, at the scale of a year. But I can’t help but conclude, as I look back at 20 years of goals, that most of my most meaningful pursuits took years to manifest.

Goals for the businessI see many examples in my business-related goals of a variety of theories and hypotheses I was testing at various points.

In 2020, I tried having “no meeting days”:

“Each day has a strong unifying intention, either free of appointments so I can focus on producing something, or open and spontaneous to make myself available to people who need me.”

But I would soon discover that a day was too large a block of time, and it fit my energy cycles much better to reserve all mornings free of meetings, and to spend the afternoons on calls.

I can see I consistently underestimated the impact of the economic and cultural environment on my business growth, thinking it all depended only on me instead of trends in online education and the economy:

“Forte Labs is growing explosively, not because of what I’m doing or pushing through, but because of who I’m being.”

I see other examples of my naivete, such as thinking I could “open source” all my content and still have a profitable business:

“Everything I know is open-sourced and available to help people create more freedom, pleasure, and impact in their work and lives, whether they ever buy from me or not.”

Some goals represented major initiatives that turned out to be completely misguided.

“I oversee an online course incubator, which regularly turns out new courses and other offerings that generate income and value for the people that have developed them. I provide every piece of knowledge, service, and counsel the participants need to develop their idea to fruition, and take a percentage while giving them a worldwide sales and marketing platform.”

We did pursue trying to build a platform and marketplace for multiple courses from other instructors for about a year, but that failed miserably as it wasn’t in line with our values or capabilities.

I laugh at how unclear my articulation of what I do has been:

“Our community is the world’s best source of conversations, curated resources, tutorials, and experiments on the future of work.”

I don’t think it’s that much better even today!

I’m also reminded, looking back at goals I’ve set, of just how diverse and wide-ranging my interests are:

“I oversee a portfolio of experiments pushing forward the boundaries of my field, such as group knowledge management, design thinking, science fiction prototyping, behavior change, self-tracking, art and music, crowdsourced collaboration, full-stack freelancing, online marketing, project management, community building, creativity, emergence, history, self-awareness, online learning, time-tracking, visual thinking, and writing.”

This exercise is a reminder to revisit some of those interests that I didn’t have time to pursue in the past, and perhaps resurrect them in a new form.

What I value todaySurveying the long arc of my goal-setting history, it’s clear that getting married and starting a family was the most consequential shift in my life. It changed every aspect of my life, including goal-setting.

One of the earliest goals I wrote down at 20 years old was this one:

“Get married to a beautiful, loving, intelligent, spiritual, sensitive woman who will make a great mother, in a wonderful gathering of our families that creates a community around us, by December 31, 2020.”

That wedding would take place in April 2019, and I couldn’t even imagine how meaningful, complex, and fulfilling that marriage would be.

I can see Lauren’s influence on my goal-setting earlier, however, such as in 2016, when I wrote:

“I respect the cycles of my body, mind, spirit, family, friends, community, nature, and nation, leaning into each season as an opportunity to bring balance to a new aspect of my life.”

She taught me balance, and nuance, and how to savor life in the present rather than only living for the future. I would never have written the following intention if it weren’t for her:

“I am ambitious but equanimous, driven but tolerant. I don’t go to unnecessary extremes, and accept moderation in most areas of my life at any given time.”

Some of the most meaningful, precious intentions for me these days are not the business milestones, but rather the mundane details of a calm and peaceful life:

“We go to bed early, reading and meditating, and fall asleep with a sense of peace and deep gratitude.”

How I set goals todayAround the birth of our daughter in 2022, I noticed that the list format for my goals that I’d kept for over 15 years at that point no longer resonated with me.

It’s because our lives themselves had become non-linear: it was no longer about the steady march of piling one brick on top of another, or winning each leg of a race. We are now a family of 4, with a lifestyle and business that my younger self couldn’t have imagined. Life has become more about enjoying our days, finding meaning in them, and squeezing the juice out of everything life has to offer.

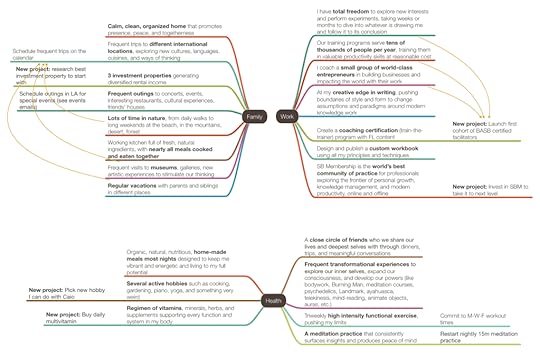

So I switched to a mindmap format to try and capture the non-linear, exploratory, and serendipitous way I think about goals today. The mindmap has three clear parts, reflecting how clearly I see the three main priorities in my life: Family, Health, and Work.

Here’s the most recent version, as of the end of 2024:

For Family, everything revolves around our kids to an extent I wouldn’t have thought possible. Looking at the intentions in that part of the mindmap, I think we fulfill all of them to a great extent, except for buying an investment property, which is something Lauren and I have realized we don’t want to manage.

For Health, my longest-running goals of eating healthy and exercising regularly have finally been fulfilled, but not because of any newfound self-discipline. It’s because we hired a full-time housekeeper and cook who takes care of all our meals. I’m working out consistently, mostly because of the nanny who picks up the kids from school and watches them in the afternoon. In retrospect, the key to my results in these areas depended on getting outside support, not any sophisticated habit formation framework. There’s a lesson there, I think.

The one intention in the “Health” arena I can’t say I’ve fulfilled has been finding a solid hobby I’m dedicated to. It’s more like I have a variety of interests and hobbies that I turn to if and when needed. In retrospect, that fits me better. I think I was expecting to become passionate about something like woodworking, or gardening, or beekeeping, but the reality is, I don’t have much obsessive energy left over after my workday.

And for Work, I once wrote “Total freedom to pursue my interests,” but only recently realized how central that value is to me. This year, I walked away from a plausibly multi-7-figure business opportunity because I couldn’t stand the thought of having to buckle down and focus on one thing for a couple of years that wasn’t perfectly in line with my curiosity.

I also wrote in the past that I would be “at the creative edge of my writing,” but that looks quite different from what I expected. I’ve realized I don’t mainly value writing the most creative, soulful prose, nor pushing forward cutting-edge research. I value popularizing and spreading proven ideas that I know work to more people, who wouldn’t find out about them otherwise. That’s a different kind of “edge,” and I’m finding it requires traits like balance, wisdom, and a sense of perspective. Maintaining those qualities in my work is my own personal “cutting edge.”

These days, I face an abundance of opportunities, a plethora of possible paths forward. It feels much less like forging a path through an impenetrable jungle with my machete, and more like thoughtfully intuiting my way like an experienced explorer tracking an elusive beast.

Everyone has underestimated me, including myselfLooking back at the last half of my life, and how deeply it was shaped by the practice of goal-setting, a final lesson comes to mind: everyone I’ve ever met – including my parents, teachers, friends, professors, colleagues, mentors, and employers – has always underestimated me.

No one ever knew how much I was capable of, not even myself. No one understood or could have predicted how much hard work, courage, determination, and persistence I had inside me, least of all myself. I had to find it all inside.

This thought came to mind as I was driving in the car on the way to pick up my kids, shortly after writing a first draft of this article. It brought me to tears, as I felt myself acknowledging my younger self and giving him the trust and recognition that he so craved.

Applying that same observation to others has led me to one of my core beliefs: that each person’s potential is inherently unlimited. That’s why I believe so much in education and its limitless ability to transform people’s lives. Why I’m such an advocate of personal development as a discipline that can be planned and pursued systematically. Why it’s so important to me to learn how to leverage AI as a force to unlock people’s talents and abilities.

The next 20 years of my own journey, I can clearly see, are about helping others craft the life of their dreams as I have. I intend to use everything I know and everything I have to do so.

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on X, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you’re ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

The post What I’ve Learned From 20 Years of Goal-Setting appeared first on Forte Labs.

October 13, 2025

Beyond Acceptance: The Transformational Journey of Applying to Grad School (or Anything Else)

My wife Lauren and I met at a co-working space in San Francisco in our mid-twenties. I was working an entry-level position at a creative consulting agency, at the bottom of the pyramid. Lauren was making $15/hour at an arts nonprofit, living rent-free with her aunt.

We both saw no pathway to climb in our current jobs and chose two different paths to reaching for more.

I quit the creative agency to become an entrepreneur, designing my first online course. Lauren applied to grad school.

Neither path was easy, but both catapulted us from entry-level jobs to the careers of our dreams. What got us there wasn’t our qualifications, but our courage to go after something bigger than we were ready for.

Those leaps transformed us. We learned that you don’t wait until you’re qualified—you become qualified in the process of taking action. When you pursue something that stretches you, the journey itself develops the exact skills and confidence you need to succeed.

Since then, Lauren and I have shared a mission of helping others take similar leaps. (If you hang out with us too much, you risk quitting your day job). We love helping people become active creators of their lives rather than passive participants in systems that don’t serve them.

What we’ve noticed is that both kinds of leaps—starting a business and applying to grad school—require the same underlying capacities. People without the ideal background, resources, or pedigree often overlook the soft skills that can propel them over perceived limitations. These leaps require courage and the ability to articulate a vision that moves you and others.

But there is also a difference in our two approaches.

My work tends to resonate with people who have considerable autonomy—freelancers, creators, entrepreneurs, executives, and others who design their own career paths in the wild frontiers of professional independence.

But the reality is that most people’s careers don’t unfold that way. They navigate through institutions—companies, universities, governments, and nonprofits. Their success depends on leveraging opportunities these organizations provide and successfully passing through gatekeepers who control access to advancement. This is where Lauren is the yin to my yang.

While I’ve spent a decade helping people create freedom outside traditional structures, she’s mastered the art of navigating within them—and teaching others to do the same. Through her program Grad App Academy, she’s coached over 500 people from around the world into gaining admission to elite schools including Harvard, MIT, Stanford, Berkeley, and pretty much any other top U.S. university you can name.

I’m incredibly proud and excited to share that she’s now distilled all that experience and knowledge into a new book, Beyond Acceptance: The Transformational Journey of Applying to Grad School.

The Hidden Curriculum No One Teaches

The Hidden Curriculum No One TeachesHer book reveals the “hidden curriculum” of applying to grad school – a series of rules, insights, and strategic levers that no one teaches you, and yet vastly increase your odds of getting into the school of your dreams. These tactics are crucial for standing out from the crowd of more than 1 million people who apply to U.S. graduate programs every single year.

As a co-founder of our company, Forte Labs, Lauren also weaves in many of the ideas and principles you may have seen in my content or books, but geared toward grad school applications.

Most people approach grad school applications by working harder: taking more classes to boost their GPA, studying endlessly for standardized tests, applying to dozens of schools hoping something sticks. They’re exhausted, scattered, and often end up with mediocre results because they’re spreading their energy too thin.

Lauren teaches the opposite approach: work smarter by being strategic and intentional.

Instead of applying to 15 schools, apply to 4-7 programs that truly resonate with your vision. Instead of trying to compensate for every perceived weakness, leverage your unique strengths. Instead of cramming more credentials onto your resume, craft a compelling narrative that helps admissions committees see the value you’ll bring.

The title captures what makes this book different from every other grad school application guide out there. Yes, it contains all the tactical advice you need—how to choose programs, craft compelling essays, secure strong recommendations, and navigate interviews. But more importantly, it teaches the transformational mindset shifts that will serve you for taking any big leap:

Curiosity over Conditioning- Learning to follow what genuinely lights you up rather than what society tells you you should do.

Courage over Credentials – Taking action despite feeling unqualified, reaching out to strangers, and creating your own opportunities rather than waiting for permission.

Compassion over Criticism – Silencing your inner critic to see your unique gifts and tell your story powerfully.

Intuition over Information – Learning to trust your inner wisdom when facing uncertainty.

These aren’t just principles for grad school applications. They’re the capacities that allow you to navigate any inflection point in your life with confidence and clarity. They’re what allow you to stop letting gatekeepers determine your worth and start trusting yourself to create the future you envision.

Whether you’re applying to grad school this year or considering any other big leap, this book will help you develop the courage to go after what you deeply want—and become the kind of person who continues pursuing meaningful goals long after the acceptance letters arrive.

Lauren has seen her former students use the same skills she’s taught to win major scholarships, grant funding, and even get into start-up incubators like Y Combinator.

Start With the Most Important Question

Most books on this topic focus narrowly on the “how,” taking for granted that getting a graduate degree is the right choice for you. Lauren’s process is much deeper, more personal, and more foundational. It begins with crafting a core vision you have for your life and then determining if grad school is the shortcut to that future, or a detour.

Starting with this foundation has so many powerful advantages. First, it may cause you to realize that grad school isn’t the right path for you at all, saving you years and many thousands of dollars. Depending on what you are trying to achieve in your life and in the world, she asks you to consider all kinds of alternative pathways that may be a much better fit, including:

Learning the skills you seek through work experience (and getting paid for it!)Finding mentors in your field you could learn from directlyTaking online courses, bootcamps, cohorts, fellowships, or other programs that more directly target your goalStarting an independent project or even an organization that teaches you through real-life experienceThis is such a valuable, crucial step! Lauren often notices that many people go to grad school for the wrong reasons – because they don’t know what else to do, because it seems like the “next logical thing,” or to please their parents. Lacking a compelling vision for where they’re going, they casually walk into this multi-year, six-figure commitment without a plan for who they want to be on the other end.

If you decide that grad school is indeed the right choice for you, then starting with your vision will be just as important, since the lack of one is the single biggest mistake that Lauren has seen in the over 1,000 essays she’s reviewed.

As she writes in her book:

“Instead of “I want to work in renewable energy,” I want to hear “I want to accelerate the transition to clean energy in rural communities that have been economically dependent on fossil fuel industries.” Instead of “I want to get into tech,” I want to hear “I want to develop technologies that democratize access to high-quality film special effects.”

Once you’re clear on your vision, Lauren then takes you through a strategic, targeted, and proven process for developing the best possible application you can, including dozens of insights and tricks she’s gleaned from seeing who gets in and who doesn’t.

For example:

How to reach out to current students to get insight into what it’s actually like to be in the program you’re applying to, and what unwritten rules determine who gets inRevealing essay prompts that help you uncover the stories, milestones, and paradigm-shifting moments that made you who you are todayGuidelines on when and how to use AI to save time, and when to avoid it at all costsHow to prep your stories and examples in advance, so you’re not scrambling during an interviewHow to draft your own letters of recommendation to make it far more likely you’ll get them submitted on timeHow to negotiate your funding with the university you got accepted to, instead of just settling for whatever they offer youLauren started her business because she was the first in her family to go to college. She witnessed the many built-in disadvantages for people like her trying to ascend through the halls of elite institutions. At UC Berkeley, she served on an admissions committee and taught as a Graduate Student Instructor, and saw firsthand how unfair and opaque the entire admissions process could be.

She has spent the last year pouring her love and wisdom into this book to make her knowledge more accessible to others, especially anyone who doesn’t have the perfect resume or the most pristine pedigree.

Her mission is to serve those who didn’t go to the most prestigious schools, are applying from outside the U.S., received a low GPA, or are switching into new fields they haven’t previously studied.

For all these people, applying to schools and programs of various kinds is still one of the most reliable paths to upward mobility, financial stability, and impact. This book contains the best advice I’ve ever seen on how to take that path confidently and successfully.

The reason it’s called “Beyond Acceptance” is that the skills you gain, the story you tell, and ultimately the person you become as a result of applying to grad school, or applying to anything, will continue to serve you for the rest of your life, whether in business, parenting, advocacy, relationships, or in retirement.

Lauren writes that “Your purpose isn’t something you do; it is something you are, a state of being that can’t be taken away by getting rejected from grad school.”

Perhaps the most fundamental thing of all that you’ll take away from this book is how to believe in your vision, whether or not traditional systems of power recognize it or not. What that ultimately requires is learning to listen to your inner compass, no matter what society conditions you to believe.

I encourage you to pick up a copy on Amazon.

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on X, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you’re ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

The post Beyond Acceptance: The Transformational Journey of Applying to Grad School (or Anything Else) appeared first on Forte Labs.

October 6, 2025

Boundary Intelligence: Why What You Can Access Matters More Than What You Know

A new, powerful definition of intelligence is emerging out of the AI field: “boundary intelligence.”

I first came across it in this excellent piece To Know Is To Stage by Venkatesh Rao, which appropriately, was co-authored by an LLM.

Let me step back and explain what boundary intelligence means (mixing my own words with paraphrasing from that piece).

Our definition of “intelligence” has already evolved through a few eras.

For most of human history, intelligence was mainly defined as “strong memory.” Information was so hard to access in the first place that your ability to recall specific facts and details from memory was considered the highest mark of intelligence.

When the printing press arrived, that definition changed for good. Memorizing long passages became obsolete and unnecessary, since the most flawless memory couldn’t compete with even a small reference library.

Intelligence started to be defined as the ability to process or analyze information that was stored in written form. That included the ability to cross-reference ideas found in different written works, and to synthesize or distill them into a new understanding.

That definition was only strengthened with the rise of digital technology in the late 20th century. Our main metaphor for human intelligence became “processing power,” in analogy to the computer. Intelligence was something that happened “inside the brain,” as a function of a person’s raw brainpower.

Just like a computer processor, intelligence was defined mainly in terms of power and speed. An intelligent person was someone who could arrive at novel insights quickly.

But the rise of AI is once again changing our definition of intelligence. That’s because even at this early stage, it already far surpasses our ability to process information, especially large amounts. Many tasks that AI accomplishes in seconds would take us days or weeks to achieve on our own.

Updating the Definition of IntelligenceRao proposes a new definition of intelligence in the age of AI: intelligence is defined by what information can be accessed under constraints of cost, availability, and time.

The reality is that storage is now cheap. Computation is even cheaper. What’s expensive is short-term memory access – the ability to keep the relevant details “in mind” for a given problem.

Let’s examine what makes short-term memory access such a difficult problem.

If we use RAM in a computer as a metaphor, the easiest information to access is whatever was accessed most recently. If you have a certain set of data already loaded up “in memory,” it is instantly and cheaply available, versus data that has to be found and loaded up from a hard drive or server.

Thus, a computer’s “intelligence” is now constrained not by the power of its processor, but by its ability to keep the right fragments of the past (and the imagined future) close enough to inform the present. In other words, the bottleneck of a system’s intelligence is how cheaply it can remember.

If you look at how modern computers perform, you can see this principle at work. A CPU can perform billions of operations per second, but is often stuck waiting for the right information to arrive from memory. Storage is cheap and computing is abundant, but what remains tremendously expensive is getting the right data to the right place at the right time.

It’s not the price of knowing that limits intelligence now, but the price of remembering. And the same is increasingly true of humans, as we co-evolve with our technology.

Activating a memory in the human brain is an expensive operation. It requires waves of coordinated firing across widely distributed neurons, the expenditure of neurotransmitters and metabolic energy, and of course, it takes time. Our “system” pays a real price to retrieve information, and that price determines what we call our intelligence.

The New Frontier of IntelligenceAnother way of saying all this is that the new frontier of intelligence is at the boundary of a system – including a computer or a human brain – where it interfaces with external memory. That is where decisions are made about what information to retrieve, when, and how. That boundary is also a filter, determining which information is allowed to enter the system and at what cost.

Rao calls this “boundary intelligence” – the ability to make good decisions at the boundary about what information becomes “knowable” at any given time.

How is the decision of which information to keep accessible made?

It’s made based on predicted needs => what data the system predicts will be useful in the near futureIt’s made based on access frequency => data that was accessed recently is more likely to be needed again soonIt’s made based on cost => if a piece of info is buried too deep, or would require too much computation or energy to retrieve, it’s deprioritizedThis explains why intelligent systems – again including human brains, digital computers, and LLMs – often behave in ways that seem deficient or suboptimal. They are not retrieving the ideal memory; they’re retrieving the affordable one. Intelligence in this view isn’t about optimizing across all known information, but optimizing for accessible information under constraints.

We know that the act of recall in the human brain “reactivates” a memory. And the more we recall a specific memory, the more familiar and accessible it becomes in the future. In other words, if we’ve “paid” to keep a memory warm and active by recalling it frequently, it will be even easier to remember the next time. That is how we might remember a fond childhood memory better than yesterday’s boring work meeting.

The implication is that a truly intelligent system is not one that remembers everything, which is impossible anyway. It is the system that knows how to retain access to what matters at its edges, through filtering inputs, deciding what to retrieve, prioritizing relevance, and managing communication with outside systems.

While it’s important to have a certain level of “internal” intelligence, to be able to think and reason and self-regulate, past a certain point, it is boundary intelligence that dominates outcomes. Here are some concrete examples:

Reading well (interior intelligence) matters less than choosing what to read (boundary intelligence)Arguing well (interior) matters less than deciding when and to whom to speak (boundary)Thinking clearly (interior) matters less than focusing attention wisely (boundary)LLMs trained on more data (interior) matter less than having access to rich context (boundary)Being individually productive (interior) matters less than being able to orchestrate a team (boundary)Boundary Intelligence Is Fundamentally Social

There’s one final detail in this theory: most of the memory an intelligent system utilizes is not its own.

That’s true of computers: they mostly pull data from external hard drives, local networks, or remote servers. Most memory infrastructure is shared.

It’s also true of humans: we rely on external language, culture, societal norms, rituals, and documents, all of which constitute a collective memory infrastructure that we constantly navigate and draw upon. Our own memory is just a small node in a vast external network of books, browsers, friends, and feeds.

This means that boundary intelligence is fundamentally social. It isn’t just about what to retrieve, but from where and from whom. You have to know who to trust, what information or resources they possess, on what terms you can acquire it, and what is expected of you in return.

To act intelligently, you have to know how to navigate through this shared memory. Each intelligent node, human and artificial, is a small island of limited processing ability floating on an ocean of distributed memory. What separates one island from another isn’t what it contains on the inside, but how it filters and navigates what’s on the outside.

Each intelligent system lives not in isolation, but in a perpetual social negotiation with its environment. To be intelligent is not to know everything, but to know how to traverse memory that isn’t yours.

What We Need NowWhat boundary intelligence gives you is persistence through time. In other words, it helps you survive – by sensing your environment, adapting to change, and recruiting allies and assets.

Kei Kreutler, in his piece Artificial Memory and Orienting Infinity, reframes cultural memory systems, such as rituals and archives, not as storehouses of facts, but as technologies of orientation.

What we need now is tools to navigate an overwhelming and constantly shifting landscape of relevance. Memory is thus not about having a perfect record of what happened in the past, but about telling you where you are now and where you want to go next. Intelligence is no longer primarily about logic or speed; it’s about the ability to retrieve the past in service of future survival and flourishing.

This is precisely why practices like annual reviews have become so vital in the modern world. In an age where our daily attention is constantly fragmented by digital devices and endless information streams, those who thrive will be those who can regularly zoom out beyond the 24-hour news cycle or social media churn, and contextualize their lives in longer arcs.

An annual review is a structured way to exercise your boundary intelligence – to consciously decide what memories to keep accessible, what patterns from the past to learn from, and what future possibilities to hold in your awareness.

In modern computing, CPUs don’t process instructions in the order they were received. They process them “out of order,” prioritizing the ones they can handle now and postponing the others for later (a process known as “random access memory”). In other words, they rearrange time.

This is the same thing we do as humans when we conduct an annual review – we revisit and reframe the past, we defer judgment and anticipate regret, and prepare for future conditions that haven’t happened yet. Our lives are not lived linearly. They are assembled out of fragments, swapped in and out of memory, and run only if and when needed.

The annual review is an orientation technology for managing this temporal complexity, a ritual that lets us consciously navigate between past lessons and future possibilities.

Our memory doesn’t just enable cognition; it enables temporal agency – the ability to reorder time, to choose when to know, when to feel, when to act. And in a world drowning in information, this agency to consciously curate what we remember and what we pursue may be the most important intelligence of all.

I explore these practices in depth in my upcoming book on annual reviews, where I show how this ancient ritual can be adapted for modern life as a powerful tool for developing the boundary intelligence and perspective we desperately need. Sign up here if you’d like to get updates on it.

The post Boundary Intelligence: Why What You Can Access Matters More Than What You Know appeared first on Forte Labs.

September 22, 2025

3-Year Update: A Financial Analysis of My Book’s Unit Economics

It has now been 3 years and 3 months since my book Building a Second Brain came out in the U.S., and I’ve just received word that it has now earned out its advance!

That probably doesn’t mean anything to readers, but to me as an author, it means a ton. It means that the “loan” of $325,000 the publisher gave me to create this book has been “paid back,” which means the project as a whole has turned a profit, at least from the perspective of the publisher.

I wanted to take this occasion to determine if it’s also been profitable for me as the author, and to evaluate the holistic financial picture of my book-writing endeavors.

First, the numbers for my book Building a Second Brain:

144,018 total copies sold in the U.S. across all formats$352,246 in total earnings to date (or $10,674 per month on average)On average, I earn $2.45 per copy sold, but that varies by format: $3.69 per hardcover sold, $2.70 per ebook sold, $1.41 per audiobook sold, and only 58 cents per paperback sold. I make 6.3 times as much money for each hardcover sale compared to a paperback!The breakdown of sales by format has been 38.5% audiobook, 32% ebook, 27% hardcover, and 2.5% paperback. This is surprising to me, as I would have expected the ebook version to far outsell audio, since I put so much emphasis on saving digital highlights.My advance was actually earned out around October 2024, or 2 years and 4 months after the book’s releaseMy second book, The PARA Method, also earned out its (much smaller) advance in this period:

33,779 total copies sold in the U.S. across all formats$63,664 in total earnings to date (or $3,350 per month on average)That amounts to $1.88 per copy in royalties (about 23% less than the first book), and varies between $2.43 for hardcover, $2.25 for ebook, and 94 cents for audiobookThe breakdown of formats has been 40% ebook, 32% audiobook, and 29% hardcover (so the ebook was more popular than the audiobook for this title)The advance was earned out around September 2024, only 13 months after the book’s releaseConsidering these books as complementary titles within the BASB ecosystem, they’ve sold 177,797 copies together in the U.S. and earned $415,910 in royalties for me as the author. If sales continue at the current pace, ongoing sales of these two books should continue to earn me about $5,300 and $1,900 per month, respectively, or $7,200 per month combined. The rest of this analysis only takes into account Building a Second Brain.

I was curious how much my U.S. publisher, Simon & Schuster, has earned from my book so far. Working with ChatGPT and some reasonable assumptions, I estimate they gross about $9.95 per copy sold on average, and after their costs, net about $8.61 per copy sold (which is 3.5x higher than what I make). At 144,000 copies sold to date, that means they’ve grossed $1.05 million, netted $850,000, and paid me $352k, or 41% of it. This doesn’t include their overhead costs, however, which probably dramatically lowers their overall profitability.

One thing I take away from this analysis is that the common idea that publishers are raking in the dough while paying authors a mere pittance is mistaken. Under this model, my share seems to represent over 40% of the publisher’s earnings on a per-unit basis, and would probably be over 50% or even more if their overhead costs were taken into account.

Comparing to a self-publishing scenarioWorking again with ChatGPT and conservative assumptions, I wanted to model what it would have looked like to self-publish my book on Amazon, knowing everything I know now.

Starting with the hardcover, I would have used Amazon’s KDP Print service. With a list price of $30, the printing cost would have come out to around $6.50. Amazon’s take would have been 60% of the list price, or $18, leaving me with $11.50 per copy sold as my royalty.

For the paperback, also via KDP Print, a book with a list price of $18 would have cost $3.50 to print, and after an Amazon take of $10.80, I’d be left with $7.30. Selling the ebook version for $15 would leave me with $10.35, and the audiobook $8 via ACX.

Assuming I sold the exact same number of copies via the self-published route, I would’ve netted:

$447,959 in hardcovers (versus $143,469 I made via traditional publishing)$476,969 in ebooks (versus $124,498)$443,832 in audiobooks (versus $78,492)$26,200 in paperbacks (versus $2,069)All of these together would have totaled a net of $1.39 million in self-publishing royalties, which is 3.95x as much as I made with a publisher. In other words, assuming the number of copies sold stayed the same, I missed out on about a million dollars. That includes, on a per-copy basis, a self-pub royalty that is ~3x for hardcover, ~13x for paperback, ~6x for audio, and ~3.8x for ebooks.

However, this is based on the following assumptions:

The biggest one is that I would have somehow managed to sell just as many copies through my own efforts as I did partnering with a publisher which I think is extremely unlikelyThis calculation doesn’t take into account the considerable amount I would have likely spent on marketing and promoting the book on my ownI’m also confident the mix of formats would be much different with self-publishing, including far fewer hardcovers and far more paperbacks, which would result in a less favorable comparisonUsing a more realistic scenario of what I would have managed to sell on my own, such as 70% as many copies sold and a more typical mix of formats, results in a self-publishing grand total of $934,510. That’s still 2.6x what I actually made, meaning I missed out on $582,000 instead of a million. Another way of saying this is that I would have only needed to sell 37,926 self-published copies, or 25% as many as I did, to make the same earnings as I’ve done through traditional publishing.

Including foreign translations

Including foreign translationsIf I include foreign rights and translations, however, the picture changes considerably. To date, I’ve made $276,000 from 225,000 foreign copies sold via 24 foreign publishers. That means I make $1.23 per foreign sale, versus $2.45 on average for U.S. sales, or only half as much.

But I doubt more than 2 or 3 of those would have happened if I had self-published, which means the differential would have only been around $306,000. In terms of raw numbers of copies sold, U.S. sales have accounted for only 39% of total global sales, and I expect that number to keep going down as new foreign translations continue to be released.

All of this boils down to a simple distinction: traditional publishing still wins when it comes to overall reach plus foreign rights; self-publishing wins when it comes to overall per-copy economics.

Worldwide, across all formats, I make $1.70 per copy sold. Via self-publishing, I would have made $9.27 per copy sold, or 5.5 times as much (though limited only to the U.S.)

Projecting into the futureIf I assume that my book is at the midpoint of its lifetime sales as of now, and will go on to sell another 369,000 copies worldwide, then I can expect to make another $627,540 in earnings through traditional publishing, in contrast to another $2.4 million via a hypothetical self-published route.

If that comes to pass, that results in a grand total, lifetime earnings number for this book of $1,255,000, versus a hypothetical $4,789,000 via self-publishing.