Donald J. Robertson's Blog

November 29, 2025

Next Week: Ancient Philosophy Meets Your Anxiety

Hi everyone,

Just a quick reminder that next Thursday I’m teaching a new live workshop:

“Five Things I’ve Learned from Ancient Wisdom about Coping with Anxiety.”

👉 REGISTER NOW: Ancient Wisdom for Modern Anxiety

📅 Thursday, December 4 — 8pm Eastern

Over the past twenty-five years of studying Stoicism and cognitive-behavioural therapy, I’ve been struck by how similar our anxieties are to those of the ancient philosophers — and how powerful their solutions still are.

Next week’s class will focus on five of the most effective techniques I’ve found for calming the mind during uncertainty:

The View from Above – shrinking anxiety with perspective

Premeditatio Malorum – preparing for setbacks without catastrophizing

Cognitive Distancing – separating from anxious thoughts

Virtue Ethics – anchoring yourself in character, not outcomes

Modelling the Sage – borrowing strength from internal role models

We’re also creating a Stoic Anxiety Cheat-Sheet (infographic) summarizing all five tools. Everyone who registers will get it before the live class.

If you’d like to join me for this session, I’d love to see you there.

👉 Reserve your spot: Ancient Wisdom for Modern Anxiety

Best,

Donald Robertson

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

November 26, 2025

The Rescuer Trap: Treehouse of Sadness: Codependency and Depression

This episode features guest hosts Dr. Scott Waltman and Kasey Pierce, authors of the forthcoming book The Rescuer Trap. Kasey breaks the silence with a six-word confession. She and Scott then explore the painful truth of codependency: when you jump into the quicksand of a partner’s depression to save them, the inevitable result is sinking yourself.

Are you the fixer, the over-giver, the emotional first responder for everyone but yourself? Welcome to The Rescuer Trap. We playfully own the labels “Parentified and Codependent” to make a point: these are not identities, but learned behaviors.

And what can be learned can be unlearned. Hosts Dr. Scott Waltman and Kasey Pierce use Stoic philosophy and CBT to give you the tools to break the cycle and reclaim your autonomy. Your escape from the trap starts here. Based on the forthcoming book, The Rescuer Trap (New Harbinger).

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

November 25, 2025

Marcus Aurelius versus Donald Trump

Mock-up of Trump holding a picture of Marcus Aurelius

Mock-up of Trump holding a picture of Marcus Aurelius[This article was originally published in July 2019.]

Ever on [Marcus Aurelius’] lips was a saying of Plato’s, that those states prospered where the philosophers were kings or the kings philosophers. — Historia Augusta

Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius’ (121–180 AD) was the most famous proponent of the Greek philosophy known as Stoicism. Having just written a book about Marcus (How to Think Like a Roman Emperor), I’m often asked what the Stoic emperor would think of the current US president, Donald Trump. How would their political ideals and leadership qualities compare?

Stoicism has experienced a resurgence over recent decades, which extended into the political realm. Recently, Pat McGeehan, a Republican legislator in the West Virginia House of Delegates, wrote a book titled Stoicism and the Statehouse (2017). It was inspired, in part, by the example of James Stockdale, who drew on his knowledge of Stoic philosophy while enduring torture for over seven years in the notorious Hanoi Hilton, during the Vietnam War. Stockdale later ran as a vice presidential candidate in the 1992 election, on the same ticket as the independent Ross Perot. He once wrote that the sine qua non of a leader lies “in his having the character, the heart, to deal spontaneously, honorably, and candidly with people, perplexities, and principles.” Stoicism is a virtue ethic, which prizes moral wisdom and strength of character. Stockdale agreed with Will Durant’s statement that it therefore “produced the strongest characters of its time”, exceptional leaders, “men of courage, and saintliness, and goodwill,” including Marcus Aurelius.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

When General James Mattis announced he was a fan of Stoicism recently, it raised the question of how Stoic virtue ethics might inform his conduct as Secretary of Defence under the leadership of President Trump. While in office, Mattis told an audience of military cadets that the one book every American should read is The Meditations of Marcus Aurelius. “In combat”, he said, “the reason I kept a tattered copy in my rucksack to pull out at times was it allowed me to look at things with a little distance.” Mattis drew inspiration from Stoicism when frustrated with all “the political heave ho” in Washington and the apparent inexperience of certain individuals around him. He mused that the Empress Faustina, and Marcus’ son and co-emperor, Commodus, “were not people that you’d want to spend much time with”. Marcus Aurelius’ attitude toward these challenges clearly struck a chord with Mattis. What he admired most was the “humility and the dignity with which he conducted his life” as a ruler, even in the face of extreme circumstances. A few months later, General Mattis resigned from the Trump administration, citing a lack of alignment between his own views and those of the president.

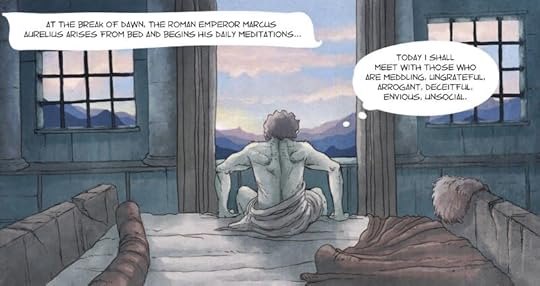

Excerpt from one of my web comics about the life and philosophy of Marcus AureliusMarcus Aurelius as Emperor

Excerpt from one of my web comics about the life and philosophy of Marcus AureliusMarcus Aurelius as EmperorAt the beginning of The Meditations, Marcus Aurelius sets forth his Stoic political ideals. Marcus’ friend and tutor, the Aristotelian Claudius Severus, taught him what it meant to love truth, justice, and his fellow man. He also introduced him to the political values of famous Roman Stoic republicans, such as Cato the Younger and Thrasea Paetus who sacrificed their lives opposing despots — Julius Caesar and Emperor Nero respectively. From their example, Marcus learned to cherish:

[…] the idea of a republic in which there is the same law for all, a republic administered with regard to equal rights and equal freedom of speech, and the idea of a kingly government which respects most of all the freedom of the governed. — Meditations, 1.14

We can see that he lived and ruled by these principles. Marcus was acclaimed emperor with the full support of the Senate and yet he insisted that, for the first time in Roman history, power should be shared by two co-emperors. His adoptive brother and son-in-law, Lucius Verus, was therefore appointed to rule alongside him.

Marcus typically confirmed appointments and ratified important decisions through the Senate. The Historia Augusta states that he significantly extended the powers of Senators, making them “the judge in many inquiries and even in those which belonged to his own jurisdiction.” We’re told that Marcus showed more respect to the Senate than any other emperor. The Stoics believed that a mixed constitution was the best form of rule because it could combine the best elements of different political systems by allowing different branches of government to provide checks and balances for one another. Marcus genuinely viewed himself as a servant of the people therefore and actively sought to share power with his co-emperor and the Senate. In other words, despite being a Roman emperor, he was, at least in some key regards, arguably perceived as less autocratic than President Trump is today.

We’re told that he ruled in such an exceptionally tolerant manner that even though a popular satirist constantly ridiculed him, Marcus was not offended. He refused to do anything to punish such critics or restrict their freedom of speech. The same historian writes:

Toward the people he acted just as one acts in a free state. He was at all times exceedingly reasonable both in restraining men from evil and in urging them to good, generous in rewarding and quick to forgive, thus making bad men good, and good men very good, and he even bore with unruffled temper the insolence of not a few. — Historia Augusta

The Stoics believed that a true ruler, or leader, must be unswayed by flattery and unperturbed by insults. This notion perhaps goes back to Antisthenes whose saying Marcus Aurelius quoted with approval: “It is a king’s part to do good and be spoken of ill” (Meditations, 7.36). In his play Hercules Furens, the Stoic philosopher Seneca likewise wrote “’Tis the first art of kings, the power to suffer hate.” Arguably, though, President Trump has been rather less tolerant of criticisms in the free press and other media than the Emperor Marcus Aurelius would have been.

General Mattis also mentioned to those cadets that Marcus Aurelius spent much of his reign far from home, fighting the northern tribes along the Danube. The First Marcomannic War was interrupted by a civil war in 175 AD. An uprising instigated by Marcus’ most senior general in the east, Avidius Cassius, who had presumptuously acclaimed himself emperor in Egypt. Mattis admired the way Marcus Aurelius responded to this and other events, observing that “the commitment to his country, to his troops, really comes through” as you read the pages of The Meditations.

Marcus’ response to the usurper Avidius Cassius is one of the clearest examples in the history books of Stoic philosophy being put into action by a political leader. As soon as news reached Rome of the rebellion the Senate freaked out. Their knee-jerk reaction was to officially denounce Cassius as an “enemy of the people” (hostis publicus) and seize his assets. This, of course, escalated the crisis. The populace became afraid that Cassius would march on Rome, sacking the city to exact revenge. It would probably have taken over a week for a dispatch rider bearing the news to reach Marcus Aurelius’ army camp on the northern frontier. What the emperor did next was reported in detail by the Roman historian Cassius Dio, who even provides the reputed text of the speech he delivered before the gathered legionnaires — it’s frankly astounding.

Marcus declared that if Cassius had sought to impeach his authority peacefully he would have voluntarily stepped down from office and spoken before a Senate hearing where the claims against him could have been judged impartially, through due process. One of the most important ethical principles that the Stoics inherited from Socrates was the doctrine that no man does evil knowingly. Based on this premise, Marcus overcame his naturally quick temper, developing instead empathy and a reputation for showing clemency and forgiveness. He refused to blame Cassius or express anger toward him. Instead he insisted the most plausible explanation was that the rebels had acted in error, mistakenly believing rumours of his death from illness. Marcus therefore announced that he was officially pardoning everyone involved in the rebellion against him.

Cassius refused to stand down so, ironically, his own officers turned on him, beheading him in an ambush. They deemed that preferable to facing the might of the loyalist army advancing toward them under the rightful emperor’s command. Having been pardoned they had no more reason to fight. The civil war ended with minimal bloodshed about three months after it had begun. Cassius was a strict disciplinarian, notorious for his cruelty, who dismissed Marcus as a “philosophical old women” and a weak leader. However, though they feared Cassius, his officers weren’t willing to risk their skins for him, whereas Marcus’ troops loved him and remained steadfastly loyal.

Another Roman historian, Herodian, wrote of Marcus Aurelius:

The ruler who emplants in the hearts of his subjects not fear resulting from cruelty, but love occasioned by kindness, is most likely to complete his reign safely. For it is not those who submit from necessity but those who are persuaded to obedience who continue to serve and to suffer without suspicion and without pretense of flattery. And they never rebel unless they are driven to it by violence and arrogance.

President Trump has watched one after another of his former allies leak information, turn on him, and even testify against him in court. These are the fairweather friends the Stoics warn us against: friendships of expediency. The president has also been quick to get rid of appointees who questioned his judgement. Marcus Aurelius, by contrast, surrounded himself with a handful of carefully chosen “friends of the emperor”, hand-picked for their wisdom and strength of character. He encouraged them to speak plainly to him, and he retained them even when they challenged his decisions. I think perhaps Marcus, in his capacity as imperator, would have welcomed General Mattis’ views, whether or not they aligned with his own.

I think it’s fair to conclude that President Trump cuts a very different figure from Marcus Aurelius in terms of his leadership style. Presidential historian Jon Meacham, wrote of the surprising relevance Marcus Aurelius’ “optimistic Stoicism” has for the crises faced by contemporary US politicians. In doing so, Meacham noted some the most relevant qualities Marcus sought to embody as emperor were truthfulness, humility, and affection for his neighbours.

The Stoics, who were notorious for their paradoxes, would say that true leadership, or as they put it kingship, is a state of mind. Kingship can be possessed by anyone no matter how humble their station in life. Diogenes the Cynic was an exile who lived like a beggar but somehow more majestically than Alexander the Great, whom legend claims he looked upon as, at best, an equal. Whether or not any given king is kingly, or president presidential, we should all aspire to possess the virtues of leadership ourselves by living as wisely and responsibly as we can, treating others courteously, and so on.

“Only the virtuous man rules,” say the Stoics, “and even if he does not in all circumstances do so in actuality, still in all circumstances he does so by disposition.” In other words, leadership is a state of mind, a truly “kingly” or “presidential” character can be exhibited regardless of our station in life. Indeed, the virtues of leadership potentially exist within each and every one of us and that’s the first place we should start looking for them.

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

November 20, 2025

A Stoic Way to Practice Mindfulness

Such as are your habitual thoughts, so also will be the character of your mind. For the soul is dyed by its thoughts. — Marcus Aurelius

Change your thoughts and you can change your life. That’s how I sometimes paraphrase a central Stoic idea: what unsettles us is rarely the world alone but the judgments we make about events. We don’t control every event, but we can notice our thoughts and choose whether to go along with them or not. Learning to do so is a daily practice.

Explore my curated Stoic Playlist with a 30-day free trial:👉 https://www.wakingup.com/donaldrobertson

Over the past few years I’ve been asked for a practical, trustworthy way to cultivate that skill alongside our Stoic work here. Today I’m pleased to share something I believe will genuinely help. It’s something that many of my clients use and have frequently recommended to me.

When we practice attention deliberately, we make space between stimulus and response.

Listen to my Waking Up Playlist

Why mindfulness matters to StoicsStoicism teaches us to distinguish between impressions (what merely appears) and assent (what we endorse as true). Modern psychology has a parallel: cognitive distancing—stepping back from thoughts and feelings long enough to see them as events in the mind, not commands we must obey.

Mindfulness is the moment-to-moment training ground for that ability. When we practice attention deliberately, we make space between stimulus and response. That space is where reason can breathe, values can speak, and courage can act. The ancient Stoics called this prosoche or “attention” to the mind — if you prefer, we could call it Stoic mindfulness.

A brief personal note

A brief personal noteSome time ago I recorded an in-depth conversation with Sam Harris about Stoicism and mindfulness, after having spent some time exploring his Waking Up app. I found it to be an approach to meditation that invites you to understand what you’re doing, not merely perform a technique. The app weaves together lessons on philosophy and psychology in a way that feels very aligned with our work here—Stoic reflection, cognitive therapy, and the disciplined pursuit of a good life.

That’s why I’ve agreed to a collaboration. I’ve curated a Stoic Playlist inside Waking Up—hand-picked selections from my own series, our conversation, and a few carefully chosen lessons from teachers who cover related topics, including Prof. William B. Irvine, author of A Guide to the Good Life. Think of these lessons as a pathway for you, if you want to bring Stoic mindfulness into your daily self-improvement routine.

Explore my curated Stoic Playlist with a 30-day free trial:👉 https://www.wakingup.com/donaldrobertson

What you’ll find in the playlist

What you’ll find in the playlistCognitive Distancing: a short, focused practice to help you step back from thoughts and feelings before endorsing them.

Facing your Fears in Imagination: navigating adversity first in your mind so you’re prepared to do so in the real world.

Living Virtuously: applying values as a compass for everyday action.

Conversation: Philosophy for Life with Sam Harris: a wide-ranging discussion on Stoicism’s modern applications and links with Buddhist mindfulness.

Additional mindful practices and reflections that support equanimity, clarity, and courage.

If you’ve ever thought, “I understand Stoicism—but how do I practice it consistently?” this is designed for you.

How Stoicism and mindfulness meet

How Stoicism and mindfulness meet The Stoics taught that disturbing passions begin with an impression—a rapid, automatic thought—followed by a judgment or act of assent that endorses it. For example: This is terrible; I can’t stand it! or What if something awful happens? How will I cope? With training, we can interrupt that sequence, notice the appearance, and avoid being swept away by strong emotions.

In cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) we call the same move cognitive distancing. You might say to yourself:

“Right now, I notice I am having the thought ‘What if I fail?’”

“I am angering myself right now by blaming other people.”

“Anxiety is present; I can accept the feeling and observe the thoughts.”

Naming the experience is not a gimmick; it’s a way of learning to see more clearly. Mindfulness practice strengthens that capacity in the real world. When we sit for ten minutes and repeatedly notice distraction, we rehearse the very skill that helps during conflict, grief, or pressure: look, label, let go, return to what matters. Over time, the mind becomes less of a battlefield and more a workshop for developing our wisdom and virtue.

Why I’m sharing this now

Why I’m sharing this nowMy work has always been about making philosophy usable—for parenting, leadership, adversity, and everyday life. I’m partnering with Waking Up because it offers a thoughtful framework for exactly that kind of practice.

If you’re curious, I’d invite you to try the playlist for a week and see what changes. You can listen to my whole course on Stoicism and Mindfulness with a free 30-day trial, giving you access to the whole app, with many other courses from other authors.

Start your 30-day free trial here:👉 https://www.wakingup.com/donaldrobertson

A closing reflectionEarlier I said that Marcus Aurelius reminds us how the mind becomes dyed with the color of its habitual thoughts. Practice is how we choose the dye. A few minutes each day, applied steadily, can shift the tone of a life—from rumination to reflection, from impulse to intention. Philosophy gives us the why; mindfulness gives us the how.

I hope this playlist helps you strengthen both.

This is an affiliate partnership—if you subscribe via my link, I receive a commission at no extra cost to you.

PS. If you try just one thing today, make it the Cognitive Distancing clip in the playlist. It’s a simple exercise for stepping back from thoughts so you can decide—calmly and deliberately—what deserves your assent. Use it once when you’re clear-headed, and once when you’re stirred up. The contrast is the lesson.

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

November 19, 2025

The Rescuer Trap: Doormat or a Hand Grenade: When Rescuing Behavior Gets Overcorrected

This episode features guest hosts Dr. Scott Waltman and Kasey Pierce, authors of the forthcoming book The Rescuer Trap. It’s time to rejoin the pack, lone wolf, and bring your newfound healthy boundaries with you. Scott and Kasey unpack Maladaptive Overcorrection and how to find the middle path of flexibility and true, healthy Interdependence.

Are you the fixer, the over-giver, the emotional first responder for everyone but yourself? Welcome to The Rescuer Trap. We playfully own the labels “Parentified and Codependent” to make a point: these are not identities, but learned behaviors.

And what can be learned can be unlearned. Hosts Dr. Scott Waltman and Kasey Pierce use Stoic philosophy and CBT to give you the tools to break the cycle and reclaim your autonomy. Your escape from the trap starts here. Based on the forthcoming book, The Rescuer Trap (New Harbinger).

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

November 18, 2025

How to Turn Intellectual Insight into Emotional Insight

So you’ve realized that some of your beliefs are irrational and that they shape your emotions to a greater extent than you previously assumed. What now? As people often put it, how do you turn your intellectual insight into emotional insight? How do you achieve deeper and more experiential change? Well, you’re not alone. This is what other people do…

Photo by Suzanne D. Williams on Unsplash

Photo by Suzanne D. Williams on UnsplashStoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Habitual DisputationFirst of all, disputing your irrational beliefs more consistently is often important, and focus helps. If you challenge lots of different thoughts in an inconsistent way, that can lead to superficial changes. So try to identify your most important irrational beliefs and get into the habit of really refuting them as directly and concisely as possible, until it becomes second nature to you. In my experience, people who think they’ve challenged their irrational beliefs, without feeling emotional benefits often just haven’t done it systematically enough.

So hone in on your core rigid demands. These can take various forms but the three most common types are:

I MUST succeed otherwise it means I’m a total failure.

People MUST treat me with respect otherwise they’re total jerks.

My life MUST be comfortable and pleasant enough otherwise it’s absolutely awful and I can’t stand it.

Focus on your rigid MUSTs but also look out for and dispute their cousins:

Awfulizing, or judging things to be a disaster.

Low frustration tolerance, or acting as if certain types of discomfort are too much for you and you can’t cope.

Damning people, yourself or others, by putting them down in the form of global negative ratings or labels.

Often when people say “I’ve tried cognitive therapy but it didn’t work”, and you ask them to demonstrate how they dispute their irrational beliefs, they can’t, or they do it very weakly or in a half-hearted way. It’s important to build your skill and confidence through repetition. Remember to challenge your irrational beliefs in a number of ways and try to make your disputes as powerful and decisive a you can.

Dispute the Pragmatism. Ask yourself, “How is this likely to work out for me in the long run?” — e.g., “How is believing that I must always succeed working out for me?” But go harder and actually persuade yourself, if possible, that the belief itself does you more harm than the thing you’re concerned about and that it’s not just unhelpful but totally self-defeating.

Dispute the Evidence. Ask yourself, “Where’s the evidence for this?” — e.g., “Where’s the evidence that people MUST always treat me nicely?” Again, go harder and ask yourself whether there could ever conceivably be any evidence to prove your rigid demand is true? No, because by definition it’s not grounded in observation — it goes beyond the facts. I would point to my countryman, the philosopher David Hume, here and his assertion that we cannot derive an “ought” from an “is”, known today as the naturalistic fallacy. It’s not just false, it’s unempirical.

Dispute the Logic. Ask yourself, “How is this even logical or rational?” — e.g., “How is it logical to conclude that just because I strongly desire that things were easier, they absolutely must be easy?” Again, you can go further and dispute whether it can ever be logical to believe that something “must” be the case when you already know that sometimes it is not. Believing “Life absolutely must always be pleasant, but sometimes it isn’t” — is an obvious logical contradiction! I would refer you to another great moral philosopher here, Immanuel Kant, who famously said “Ought implies can”, meaning that it is simply irrational to say that something “ought” or “must” be the case, unless it is somehow under your control. It’s not just irrational, it’s contradictory.

In addition to asking these questions, it’s usually important to directly counteract your irrational beliefs by rehearsing a rational, realistic, and constructive belief, which will usually feel less rigid and more flexible. For example, “I strongly desire succeeding but I don’t always have to do so, and if I don’t it’s not the end of the world; I can cope.”

You may already be at this stage but the truth is that often people need to improve their disputation skills in order to transform intellectual insight into emotional insight, and really change the way they feel and behave. However, let’s look at some other ways you can deepen the benefits of disputation.

Emotive Disputation“REBT therapists suggest that clients can help themselves go from intellectual to emotional insight by vigorously Disputing their irrational Beliefs.” — Albert Ellis

Albert Ellis used to tell clients that making their disputation more vigorous was the key to emotional change. That’s true for many people. It can be helped by swapping roles with a coach or therapist and practising your disputation, repeatedly going back and forth, with increasing firmness and assertiveness. Sometimes you find that it helps to adopt a firmer attitude whereas in other cases it might make more sense to speak and act with greater compassion toward yourself.

Another piece of advice that I find helps is to say that when disputing your irrational beliefs you should have at least some passion in your voice. You don’t have to turn the dial all the way up to ten because for many people even a small change in this regard can have a big impact. Instead of disputing your irrational beliefs in a purely “intellectual” way, actively choose to feel at least some emotion behind what you’re telling yourself — in other words, say it with feeling. For instance, imagine facing a problem that makes you anxious while telling yourself “I don’t like this feeling but I can deal with it.” Experiment by saying those words with a bit more passion. Speak from the heart, as if you really mean what you’re saying, and make it come through in the sound of your (inner) voice.

Ellis also recommended recording yourself disputing your irrational beliefs so that you can listen back to it. I can’t honestly say I’ve encountered many clients who use this method. You may, however, find it helps to look in a mirror and speak aloud to yourself, in order to practice disputing your irrational beliefs with more intensity and emotion. (You can also use your mobile phone as a mirror by turning on the front-facing camera as if you’re taking a selfie.) Look yourself in the eyes as you speak, and focus on the truth of what you’re saying. I would also encourage you to think creatively of ways that you could feel more engaged when disputing your irrational beliefs and rehearsing rational alternatives.

Photo by Alexei Maridashvili on UnsplashMental Imagery

Photo by Alexei Maridashvili on UnsplashMental ImageryFor many people, the simplest and most obvious way to intensify the experience of disputation is for them to close their eyes, while doing it, and imagine one of the situations that triggers their irrational beliefs. The most common mental imagery technique used by Ellis is called Rational Emotive Imagery (REI).

Anyone can change his disturbed feelings to healthy ones if he only changes his irrational musts and shoulds into realistic preferences… I encouraged him to practice rational emotive imagery once a day for thirty consecutive days until he solidly believed and felt his new philosophy. — Albert Ellis

It requires imagining yourself facing a situation in which you typically feel distressed, and really experiencing the emotion fully for a minute, in order to observe what you’re telling yourself in order to get that upset. Then promptly begin making an effort to replace the unhealthy emotion with a healthy one, and study what you tell yourself in order to do that. As I like to put it, you are going to voluntarily get yourself into the hole so that you can practice climbing back out again — and do this repeatedly.

In my experience, it’s usually best to begin by reliving recent events that are good examples of your problem. Then perhaps, as you start to introduce behavioural experiments (see below), proceed to imagine yourself in hypothetical situations, where you anticipate experiencing problems. That way you can use mental imagery to prepare in advance for challenges that you have coming up in the real world. In some cases, you may be troubled by memories about events in the distant past. That obviously happens in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) but it may also be that you simply feel anxious about public speaking, for instance, and keep remembering a time in the past when a presentation went very badly. Sometimes, therefore, it can be very helpful to relive long past events, in order to practice challenging our irrational beliefs about them.

During mental imagery, you can actively dispute your irrational beliefs, which will typically mean that you do so in a more emotional state of mind. It often feels like you’re directly changing your emotional reaction to the situation that you’re facing in fantasy. Doing this frequently can create new habits, not only of thinking, but also of feeling, in response to your problems.

Ellis recommends that clients should do REI for five minutes per day, for 30 days. In my experience, most people see benefits within a week, if they’re consistent, and really put their heart into what they’re doing. Stick with one mental image at a time, if possible, and work on it until you’ve really transformed how you feel about it, before moving on to work on a different scene in your imagination.

Behavioural ExperimentsBehavioural experiments are, in a sense, the gold standard for emotional change. In the most common version, you face your fears, repeatedly, and for longer than normal, in order to prove to yourself conclusively that you can cope and nothing catastrophic will actually happen. However, there are many other ways in which you can break your own rules and refute irrational beliefs by testing them out in the real world. As mentioned above, mental rehearsal can be a stepping stone to real-world behavioural experiments — you can rehearse what you plan to do in your imagination in order to reduce your anxiety enough to face it in reality.

Ellis famously advocated “shame-attacking” exercises, in which clients engage in embarrassing tasks in order to prove to themselves that just because they do silly things, even if other people laugh at them (which seldom happens), they don’t need to label themselves as idiots or feel ashamed. For instance, clients were often instructed to tie a piece of string to a banana and take it for a walk around a shopping mall. (Here’s a video of someone doing the banana walk exercise.) Sometimes they would introduce themselves to strangers by saying they’d recently been discharged from a psychiatric hospital or asking “What year is it?” You can decide for yourself what would be required for you to get over yourself and become more indifferent toward the opinions of other people.

It can take a bit more planning to come up with suitable behavioural experiments for every problem but it’s worth spending some time thinking about creatively. Ask yourself, for instance, how you would behave differently if you were acting “as if” you completely rejected your irrational beliefs and accepted your new rational ones. That will often give you a good indication of specific ways in which you can experiment with behaviour change.

Often behavioural experiments are about overcoming procrastination and doing what you’ve been avoiding — so I call this avoidance reversal. That may test your motivation, commitment, and tolerance of discomfort. For instance, perhaps you’ve avoided some boring tasks at work. Forcing yourself to sit down and do them each day for a week, in order to test your ability to endure the effort and boredom, makes sense. Conversely, for some people the big experiment may consist in abstaining from something they do compulsively. If you feel addicted to pornography, simply enduring the urge to look at porn, without acting on it, may be the best experiment to challenge your irrational belief about not being able to tolerate the urge while exercising restraint.

Postponement of worry or rumination is another important type of experiment. In this, you prove to yourself, repeatedly —probably every day, for weeks— that you can accept automatic thoughts about anxiety or sadness, without having a prolonged conversation about them, by delaying thinking about them until a “worry time” that you’ve already planned. You’re testing, for instance, the metacognitive belief “I MUST worry or ruminate about upsetting thoughts when they occur.” (Or “I CAN’T let go of upsetting thoughts by telling myself that I’ll come back to them later.”)

Another experiment I find helpful consists in replacing harsh criticism (of yourself or others) with guidance that is specific and solution-focused. For example, suppose you fail a job interview. Instead of beating yourself up and saying repeatedly “Why am I so incompetent? What an idiot!”, calmly accept yourself as a fallible human being, pat yourself on the back for whatever you did well, and focus your advice on how you could improve specific things, such as your answers to certain questions. Get practical and get specific, instead of castigating yourself with global labelling such as “I’m a total failure!” Through trial and error, refute your irrational belief that “I MUST harshly criticize myself and punish myself for mistakes.”

Motivation can be an issue when it comes to reversing avoidance and actually changing your behaviour. Sometimes it helps to prepare yourself by focusing on how good you’ll feel as a result of facing your fears or exercising more self-discipline. You may need to build your tolerance for effort and discomfort. Many people have employed what psychologists call “contingency management” to maintain their commitment to change, by employing rewards or penalties. For instance, you might help yourself to overcome procrastination by telling your wife that you’re going to take her to her favorite restaurant at the weekend but that it’s contingent on doing at least ten minutes of work each day on a project you’ve been avoiding — if you miss one day you have to call up and cancel the reservation. I call this the nuclear deterrent. Not many husbands want to have to tell their wife that their weekend plans have changed because they didn’t accomplish a small task. However, quite a lot of people can (somehow) motivate themselves to overcome their procrastination about work by saying: For God’s sake, just do it!

Continuing to verbally dispute your irrational beliefs and rehearsing new rational ones, before, during, and after, behavioural experiments, can really help you to deepen change and make it more experiential. Changing your behaviour is arguably the best way to get beyond mere intellectualisation. You’ll realize that all behaviour change is trial and error, or experimentation, and best approached with an attitude of open-minded curiosity. This is the big question: “I wonder what would happen if I tried doing something else instead of what I usually do?” There’s only one way to find out!

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

November 13, 2025

Where a man’s interest lies there also is his piety...

In piety towards the gods, I would have you know, the chief element is this, to have right opinions about them—as existing and as administering the universe well and justly—and to have set yourself to obey them and to submit to everything that happens, and to follow it voluntarily, in the belief that it is being fulfilled by the highest intelligence. For if you act in this way, you will never blame the gods, nor find fault with them for neglecting you.

This mirrors the twofold cognitive conceptualization of Stoic ethics attributed to Chrysippus, who said that it consists of one judgment regarding events and another about appropriate action in response to them.

But this result cannot be secured in any other way than by withdrawing your idea of the good and the evil from the things which are not under our control, and placing it in those which are under our control, and in those alone. Because, if you think any of those former things to be good or evil, then, when you fail to get what you want and fall into what you do not want, it is altogether inevitable that you will blame and hate those who are responsible for these results.

We are bound to feel frustrated eventually when we invest absolute intrinsic value in external outcomes, rather than in our own ruling faculty, because external events are not up to us. We doom ourselves to become resentful and angry toward the universe, unless we view external events lightly.

For this is the nature of every living creature, to flee from and to turn aside from the things that appear harmful, and all that produces them, and to pursue after and to admire the things that are helpful, and all that produces them. Therefore, it is impossible for a man who thinks that he is being hurt to take pleasure in that which he thinks is hurting him, just as it is also impossible for him to take pleasure in the hurt itself. Hence it follows that even a father is reviled by a son when he does not give his child some share in the things that seem to be good; and this it was which made Polyneices and Eteocles enemies of one another, the thought that the royal power was a good thing.

How could we not hate the gods, or hate the universe, as long as we invest absolute value in things that are bound to be denied us eventually?

That is why the farmer reviles the gods, and so also the sailor, and the merchant, and those who have lost their wives and their children. For where a man’s interest lies, there is also his piety. Wherefore, whoever is careful to exercise desire and aversion as he should, is at the same time careful also about piety. But it is always appropriate to make libations, and sacrifices, and to give of the first fruits after the manner of our fathers, and to do all this with purity, and not in a slovenly or careless fashion, nor, indeed, in a niggardly way, nor yet beyond our means.

Epictetus could also have said that we naturally focus our attention where our interests are invested, or threatened. So we live outside of ourselves, insofar as we confuse our good with external events.

November 12, 2025

The Rescuer Trap: Dating a Dream: The Rise of AI Dependency

This episode features guest hosts Dr. Scott Waltman and Kasey Pierce, authors of the forthcoming book The Rescuer Trap. In this Sci-not-so-Fi episode, they talk about the dangers of emotional dependency on AI and Socrates asks “What is a boyfriend?”

Are you the fixer, the over-giver, the emotional first responder for everyone but yourself? Welcome to The Rescuer Trap. We playfully own the labels “Parentified and Codependent” to make a point: these are not identities, but learned behaviors.

And what can be learned can be unlearned. Hosts Dr. Scott Waltman and Kasey Pierce use Stoic philosophy and CBT to give you the tools to break the cycle and reclaim your autonomy. Your escape from the trap starts here. Based on the forthcoming book, The Rescuer Trap (New Harbinger).

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

November 5, 2025

The Rescuer Trap: The Schema Trap featuring Dr. Jeff Perron

This episode features guest hosts Dr. Scott Waltman and Kasey Pierce, authors of the forthcoming book The Rescuer Trap. Dr. Jeff Perron joins us to explore the deep-seated schemas (like Self-Sacrifice and Subjugation) that create the “Rescuer Trap.” We discuss how these unconscious, childhood-rooted patterns conflict with your adult values, and provide insight on using a schema-informed approach to establish boundaries and finally break free from the cycle of people-pleasing.

Follow Dr. Perron on Substack:

The Psychology of HappinessProven lessons on happiness and living a rich life.By Dr. Jeff Perron, C.Psych

The Psychology of HappinessProven lessons on happiness and living a rich life.By Dr. Jeff Perron, C.Psych

Are you the fixer, the over-giver, the emotional first responder for everyone but yourself? Welcome to The Rescuer Trap. We playfully own the labels “Parentified and Codependent” to make a point: these are not identities, but learned behaviors.

And what can be learned can be unlearned. Hosts Dr. Scott Waltman and Kasey Pierce use Stoic philosophy and CBT to give you the tools to break the cycle and reclaim your autonomy. Your escape from the trap starts here. Based on the forthcoming book, The Rescuer Trap (New Harbinger).

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.

November 4, 2025

What Irrational Beliefs?

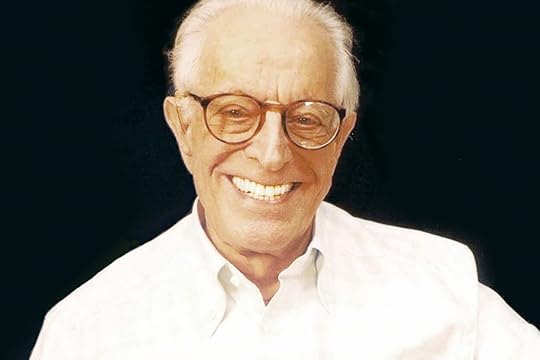

In the 1950s, Albert Ellis developed the original form of modern cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT). Ellis’ initially called his approach “Rational Therapy” but it eventually became known as Rational Emotive Behaviour Therapy (REBT). He had read Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius in his teens and drew more heavily on Stoic philosophy than any other famous psychotherapist. REBT is, moreover, often described as being the most philosophical approach to CBT.

I take inspiration from both Stoicism and REBT in my own coaching practice, and in the books that I write. Ellis was a New Yorker who expressed his ideas in blunt language — that was both a strength and a weakness. His down-to-earth style resonated with his clients, and readers, but meant that his work sometimes struggled to get the attention it deserved from academic psychologists and researchers.

Over a decade after Ellis began developing REBT, Aaron T. Beck, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania, introduced a very similar approach called cognitive therapy (CT), which stole the limelight to some extent from Ellis’ work. Many variations of cognitive therapy appeared. These are grouped under the blanket term cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) because they combine Beck’s approach, and sometimes Ellis’, with the established theory and practice of behaviour therapy.

Ellis agreed with the Stoics that emotional disturbance is caused, to a greater extent than most people assume, by irrational beliefs. He quoted the famous saying of Epictetus in most of his books and taught it to all of his clients and students.

People are disturbed not by events but by their opinions about them.

This premise continued to be important throughout the history of CBT, although I think Ellis articulated it in a very clear way, that’s still compelling and has some practical advantages.

Ellis liked to describe his approach as more philosophical than CBT. Beck avoided referring to “irrational” beliefs and, instead, spoke of negative automatic thoughts and dysfunctional (unhelpful) beliefs. However, Ellis went further than Beck by insisting that our core negative and unhelpful beliefs are also deeply irrational. I think that’s an important difference because by questioning whether they could ever be true or helpful, we can potentially dispute these sorts of beliefs more profoundly, and transform them in a more lasting way.

The ABC ModelBefore we look at specific examples of irrational beliefs, it’s important to explain what Ellis called his ABC model. Most people tend to use stimulus-response language to describe their motions and other reactions to events. They say things like “My husband rolled his eyes, and that made me angry” or “I lost my favourite toenail clippers, and that made me sad.” Ellis argued, following Epictetus, that it is not events that upset us, however, but our beliefs about them.

He illustrated this using the letters ABC, where A stands for “Activating event” (or sometimes “Adversity”). You can think of this as the trigger or stimulus. C stands for “Consequences” and includes your thoughts, actions and especially your feelings about A. REBT begins by filling in the gap, the missing B, which stands for your “Beliefs”. For example:

A: The response was activated by losing my favourite toenail clippers.

B: I irrationally believed that “I MUST never lose important things, otherwise it means I’m totally INCOMPETENT.”

C: The consequences were that I felt sad, cried for hours, and refused to come out of my room.

Although we talk as if A causes C, if that were true everyone would respond to A in more or less the same manner. The truth is that A+B causes C — our beliefs shape our thoughts, actions, and feelings, to a greater extent than we normally acknowledge. Ellis considered this the most important thing for clients to grasp at the outset of treatment.

Insight No. 1: You largely choose to disturb yourself about the unpleasant events of your life, although you may be encouraged to do so by external happenings and by social learning. You mainly feel the way you think. When obnoxious and frustrating things happen to you at point A (Activating Events or Adversities), you consciously or unconsciously select Rational Beliefs (RBs) that lead you to feel sad and regretful and you also select Irrational Beliefs (IBs) that lead you to feel anxious, depressed, and self-hating. — Albert Ellis, How to Maintain and Enhance Your Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy Gains

As Ellis frequently pointed out himself, that’s basically what Epictetus and other Stoics were saying two thousand or more years ago.

The goal of REBT is therefore to dispute certain irrational beliefs and replace them with rational ones. Now lets do a deep dive into the sorts of irrational beliefs that typically cause us problems.

Rigid DemandsEllis concluded that the root cause of most people’s problems consists in the tendency to replace strong desires, which are natural, rational, flexible and adaptive, with extreme demands, which are unhealthy, irrational, rigid and maladaptive. He liked to call this “musterbation” because it often takes the form of beliefs such as “I MUST always succeed” or “People MUST respect me” or “Life MUST be fair.” These irrational beliefs can be expressed in the form of “SHOULD”, “HAVE TO”, “GOT TO”, “NEED TO”, and in other ways but their essence is that they treat your desires as rigid necessities.

Thought experiment. Take even a strong desire or preferences and conjoin it with an assertion that what you desire is not the case. For example:

“I strongly desire that I succeed… but have, in reality, failed.”

“I greatly prefer that people respect me… but, in fact, they sometimes do not.”

“I passionately desire life to be fair… but, hey, it often turns out not to be.”

Tough luck, I guess, but it’s not the end of the world. You’re probably disappointed but not tearing your hair out about it. However, notice what happens if you turn those into rigid demands:

“I MUST always succeed… but I have failed!”

“I absolutely NEED people to respect me… but sometimes they do the opposite!”

“Life has GOT TO be fair… but it just isn’t!”

That sounds odd, right? Each of these actually sounds a bit self-contradictory. How can you rigidly demand something that you already know is not really going to happen? That’s what I like to call a recipe for neurosis. As you’re bound to get what you don’t want, you’re inevitably going to be frustrated and upset. You may as well say to yourself “I MUST get what I want… otherwise I’m going to freak out!”

Try another thought experiment:

“I MUST always succeed… but success is not 100% up to me.”

“I NEED people to respect me… but it’s not down to me whether or not they do.”

“Life has GOT TO be fair… but that’s not under my control.”

Doesn’t that also sound rather nonsensical? How can you demand that something be the case unless it’s actually under your control? And is anything really 100% under your control except your current intention? All external outcomes are at least partially in the hands of Fate. So where does that leave your demands? Desires are adaptive because, whatever else they do, they don’t deny reality. Demands are a form of self-deception. Whenever I believe something absolutely MUST not go against my wishes, I’m trying to kid myself that it’s impossible and will never happen. In the real world, that’s bound to lead to frustration unless you happen to have godlike omnipotence.

Often people doubt at first whether their beliefs are really this extreme. That’s natural. Your brain goes in and out of different states in which it temporarily believes different things, and your beliefs may become more flexible or inflexible, depending on your mood. Sitting in your armchair, with your slippers on, relaxing with a warm mug of cocoa, you may think to yourself “It would be nice if people approved of me, sure, but it’s no big deal if sometimes they don’t.” That’s your prefrontal cortex (PFC) talking — the mature and rational part of your brain. Very wise!

When under pressure, however, because you need to get to work on time but your kids have just drawn on the walls with crayons, and your wife looks at you like you’re making things worse by snapping at them, you may think differently. In the heat of the moment, your brain goes into a different mode, and suddenly you’re thinking “My wife NEEDS to respect me, otherwise what does that say about me? That I’m a complete and utter LOSER or something? That’s awful! I should be ashamed!” So you get angry, have a blazing argument, and before you know it you’re divorced and your kids hate you. (Hopefully not!)

So you may have to dig under the surface to find your lurking irrational beliefs. Extreme attitudes tends to come more to the fore when you’re upset or avoiding things. Often people overlook the problem because they think that their strong desires sufficiently explain their extreme emotions. One way to test that would be to affirm the desire while simultaneously negating the rigid demands. For example:

“I passionately desire success… but I do not HAVE TO succeed.”

“I love it when people respect me… but they do not NEED to do so.”

“I really wish life was fair… but it does not HAVE TO be.”

Most people realize when they really imagine experiencing things this way that it is indeed the rigid demand, and not the desire, no matter how strongly felt, that’s causing the problem. Having a strong desire for things to go your way isn’t going to cause intense frustration. Believing it’s a dire necessity for things to go your way will, however, prime your brain to explode.

Another thought experiment. Close your eyes and imagine the last time you were really upset — as if it’s happening right now. Relive the moment when your distress reached its peak, and focus on the aspect of the situation that upset you the most. First identify what your rational desires or preferences were. Did you want to succeed, or gain approval, or control events? Keep telling yourself your rational belief for a while, such as, “Hey, I desire things to be different, but I don’t need them to be.” Note how that attitude interacts with your feelings, and your urge to act in certain ways. You will probably observe that having a strong desire or preference (or aversion / dispreference) doesn’t cause severe emotional distress unless you escalate it into a rigid demand or extreme evaluative belief. Test that out in your imagination. Turn it into an extreme irrational belief such as “Things absolutely MUST be the way I want here, and if they’re not it’s utterly AWFUL, and UNBEARABLE - I cannot stand it!” Which one causes you more distress? Rational desires or irrational demands?

As the intensity of your emotion increases, you may notice that your attitude becomes more extreme.

Another quick thought experiment. Imagine yourself in 2-3 upsetting situations from your recent past. Voluntarily turn up the intensity of your emotional distress. As your feelings begin to reach a peak, imagine yelling out spontaneously. What did you feel like saying or doing when you increased the emotion? Get examples from multiple situations. That may often shed light on the attitudes implicit in your distress. As the intensity of your emotion increases, you may notice that your attitude becomes more extreme. You will probably recognize in it some of the irrational beliefs below!

The three examples above are common but rigid beliefs can take different forms. We impose a variety of irrational demands on ourselves, other people, and events (or life in general). Rigid demands tend to be associated with all-or-nothing thinking. The more rigidly you demand something, the more likely you are to fear that not getting it will lead to something bad. For example, “I HAVE TO be loved, otherwise it means I’m totally UNLOVABLE” or “I MUST control my anxiety, otherwise I could make a fool of myself, which would be AWFUL.” As you can see, we tend to fear either the awful consequences of failure or the personal meaning that it has for us, and our self-esteem.

Ellis believed that the demand or MUST was usually the root of the problem. In any case, these sorts of beliefs tend to be closely intertwined. So when you dispute one you will often weaken the others, although it can also be helpful to target them separately. They can each be disputed in the same way, although there are also questions specific to each type of belief, which can be used.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

AwfulizingEllis sometimes called this catastrophizing but over time that term took on a slightly different meaning. Catastrophizing tends to refer to inflating the probability and severity of an anticipated threat, whereas awfulizing, more simply, refers to the inflated severity of any event. People often feel (or rather when upset they believe) that not getting what they rigidly demand is awful. Ellis liked to say that means that it’s worse than 100% bad. It’s extremely bad. Too much to handle. “I MUST pass all my exams, otherwise my whole life will be RUINED!” It makes a crisis into a drama — a Greek tragedy!

It’s often been noted, even by the ancient Stoics, that anxiety is quite forward-looking. When we look back on setbacks, they often appear less than catastrophic. For example, most people feel that if their current relationship ended, or their marriage led to divorce, that would be disaster city. It’s unthinkable, right? Almost everyone today is in multiple long-term relationships over the course of their lives. Looking back many years later on the end of previous relationships, the fact they didn’t work out often seems bad but not awful. (Also try telling your current wife that you still feel divorcing your first wife was awful and the worst thing that ever happened to you!)

You know, it’s almost as if none of these things are objectively awful but what we mean is that we’re subjectively evaluating them as awful. That would explain why our evaluations change depending on the context, and evolve over time. What is green today will still have been green when you look back on it ten years from now. Suppose I lost a thousand bucks today. When I look back on it tomorrow, and even a decade later, it will still have been a thousand bucks, and not a single dollar less. That’s just an objective fact. But will it still be catastrophically awful? That’s a value judgment, and it’s subjective. When I’m ninety years old, I might be a billionaire and so a thousand bucks would be small change in retrospect. Who knows? The point is that the awfulness of things is not a fact, it’s just a value judgment.

The most philosophical attitude might be that it’s unpleasant, and maybe unhelpful, right now to lose a thousand bucks, but it’s not objectively awful. That might seem like mere wordplay at first but remember the experiments we did earlier. You’re unlikely to burst into tears, or at least not for long, just because you consider some setback to be temporarily very unhelpful. It’s extreme thinking that drives extreme emotions.

Often awfulizing may relate to past events, that have already happened, such as memories of unpleasant childhood experiences, in which case it can be linked with shame or depression. Or it may be conditional on something that never happens, such as believing “It would be AWFUL if everyone at work laughed at me and said my presentation was complete garbage!” Whereas CBT will often challenge the inflated probability estimates of the worst-case scenario, Ellis would often place more emphasis on confronting it and de-awfulizing it. That’s a more radical approach but I think he was right. Even if the impossible happened and everyone at work laughed you out of the room, and chased you down the street yelling “What an idiot!”, so what? Would that really be a complete disaster or would you survive? If you can recognize that none of these things are objectively awful, but only appear awful because you subjectively evaluate them to be so, then it doesn’t matter how unlikely your fears are, you’ll be able to experience them as highly unhelpful but not catastrophic.

Low Frustration ToleranceIn the 1960s, a researcher called Richard Lazarus developed what’s known as the “transactional” model of stress, a general conceptualization of emotional disturbance, which influenced most subsequent cognitive models. It is sometimes called the see-saw model because Lazarus attributed stress to the disparity between two factors called threat appraisal and coping appraisal.

This basically reinforced a distinction already present in REBT. Most CBT tends to focus primarily on the threat appraisal side of the equation, which is closely related to what Ellis called awfulizing. However, awfulizing tends to go hand-in-hand with a poor appraisal of coping, or sense of helplessness, which is similar to what Ellis called Low Frustration Tolerance (LFT) or I-can’t-stand-it-itis.

Photo by Pascal Bernardon on Unsplash

Photo by Pascal Bernardon on UnsplashIf you are facing even a very minor threat but your frustration or discomfort tolerance is low, you may feel distressed, and are likely to procrastinate or avoid the situation. On the other hand, if you are facing a very severe threat, and your frustration tolerance is low, you will feel completely and utterly overwhelmed. If you have high frustration tolerance, though, you will be emotionally resilient, and even a very severe problem may seem like a challenge to you rather than a threat.

Awfulizing and low frustration tolerance are often two sides of the same coin. “This is awful and unbearable — how will I cope?” Chronic worriers, in particular, tend to be prone to the toxic combination of catastrophic thinking plus low frustration tolerance. However, it’s also possible to be intolerant of even low levels of discomfort or frustration. People are intolerant of many aspects of life, such as:

Feelings of anxiety, sadness, anger, tension, or frustration

Feelings of tiredness, pain, or discomfort

Difficulty, effort, and hard work

Making mistakes or looking stupid

Uncertainty, ambiguity, or not knowing

Others who disagree with them or the threat of conflict

Pressure, demands, or the complexity of tasks

Having to be patient and wait for things

Feeling urges or desires without acting on them

It may sometimes be extremely difficult or unpleasant to put up with these things but where is the evidence that it’s impossible?

If you allow yourself to say that it’s “overwhelming”, “too much”, or “you cannot cope” then you’re going to extremes in your thinking. In a sense, you’re signalling a feeling of helplessness and a desire to give up, or escape from the situation. However, if you accept the discomfort, and the occasional mistake, then doesn’t the record show that you are, in fact, able to survive and come out the other side? You may experience great difficulty but you’re not literally incapable of coping. It’s unpleasant but not unbearable. And remember this: it may be a self-fulfilling prophecy. As the saying goes: whether you say “I can” or whether you say “I cannot”, either way you will prove yourself right. If you believe “I can’t; it’s too much”, you may as well throw your arms up and surrender. Here’s the bad news, though: nobody is coming to rescue you. So be willing to put up a fight if you want to be emotionally resilient.

It’s very common for people to disguise this form of self-doubt by asking themselves “How will I cope?” or complaining “I don’t know what to do!” In that moment, your appraisal of your own coping ability is effectively zero. By affirming your ability to cope, though, you activate all the resources at your disposal. And trust me, nature and nurture have already given you everything you need. Every living human being has character traits, strengths, strategies, and skills, which are perfectly designed to deal with hardship and discomfort. The simplest is just acceptance. You have the capacity for patient endurance, as well as many other ways of coping. Moreover, by chunking down tasks, and simply telling yourself “I’ll take this slowly, one step at a time”, you can make even the most daunting tasks appear more manageable. Don’t turn yourself into a helpless victim. Choose to make yourself a survivor. “They can”, said Virgil, “because they believe they can.”

DamningSelf-worth is an issue for most people. That doesn’t necessarily mean that their self-esteem is already low but, perhaps more often, that it is unstable and fluctuates because it depends on achieving some external standard of success or the approval of other people. Ellis diagnosed conditional self-esteem as one of the most common problems encountered in therapy. For example, “I MUST perform better at work than anyone else, otherwise I am a worthless FAILURE.” Putting yourself down in such an extreme way can lead to shame, anger with yourself, or even depression. The drive to avoid confirming this self-damning belief is often what leads to fear and anxiety.

People often try to motivate themselves through self-flagellation, i.e., ruminative self-criticisms. They believe “I HAVE TO criticize myself for being a FAILURE in order to learn from my mistakes and to make sure I do better in the future.” I like to call this the world’s worst self-improvement strategy. It doesn’t work. You wouldn’t expect a coach or therapist to try motivating clients by calling them “WORTHLESS” and “STUPID” would you? It tends to become obvious nonsense if you imagine adopting this strategy toward someone you care about, especially a child. Calling kids “IDIOTS” or “totally INCOMPETENT” is not a well-regarded educational method. Damning people, adults or children, actually inhibits learning rather than encouraging learning. If you wouldn’t do that to other people, why would you do it to yourself?

It’s also common, particularly in anger, to end up damning other people in a similar manner. For example, “People MUST live up to my high standards, otherwise they’re just total IDIOTS” or “People HAVE TO respect me, otherwise they’re total JERKS.” I sometimes refer to self-damning or damning others as vilification. It’s a form of objectification, in which we temporarily view others as no longer fully human but rather we reduce them to a single damnable character trait or behaviour. He’s a damn LIAR! Politicians are all so damn CORRUPT! As if there’s nothing more to a person than can be subsumed under that label. But it’s never the whole story.

Ellis championed a philosophy of unconditional self and other acceptance. He believed, as the Stoics did, that the solution to this baneful human tendency is to place our common fallibility and imperfection front and centre, and accept ourselves simply as human beings. Where is the evidence that just because you strongly dislike someone’s actions that makes their whole being WORTHLESS and STUPID? Just because you did some stupid things, it doesn’t make you a fundamentally stupid person. Condemn the sin, not the sinner. By focusing on specific actions, and keeping an open mind about the person as a whole, recognizing their fallibility and complexity, and capacity for change, we can prevent ourselves from getting into the habit of vilifying ourselves and others.

Incidentally, if you’re going to damn yourself as a fundamentally STUPID or INCOMPETENT person, you’ll soon be tied up in philosophical knots. You are the one evaluating things. If you genuinely believe that you are completely STUPID and INCOMPETENT, how can you trust your own evaluation of yourself? Surely you’d be too STUPID and INCOMPETENT to know for sure how STUPID and INCOMPETENT you actually are? It’s an operational self-contradiction.

When we judge a person as a whole to be worthless or attach a global negative label to their character, we’re making what philosophers call a logical category error. Think of this analogy. If you don’t like the shows broadcast on television, you might call them STUPID or WORTHLESS. But what sense does it make to say that the television set itself is STUPID or WORTHLESS just because you don’t like the shows? The television set has played lots of different shows in the past, and will play lots more in the future. The shows it played in the past are too varied to be reduced to a single adjective. Different people may have switched channels and watched different programs on the same device. You don’t know what it will play in the future. Indeed, there’s no limit what shows can be broadcast and played on a television. It’s the same with a human being. When we slap rigid labels on people, we forget how complex they are, how they behave differently in different contexts, and that they could potentially change at any point in the future.

A table that has four legs today will probably have four legs in the future, and if you place it in another room it will still have four legs, unless we saw one off. People are alive, though, and life is a dynamic process. Someone who acts stupidly or selfishly today may not always have acted that way. They may act differently in different situations. And they could potentially change at any point in the future. So what sense does it make to call them a STUPID or SELFISH person? That’s a form of reductionism, which leads us to reify living human beings and treat them as if they were as static and inert as a mere object.

Once again, the difference may not be obvious at first. Saying that someone has acted selfishly is a world apart, psychologically speaking, though, from saying that they are nothing but a completely SELFISH person. When we want people to learn from their mistakes we get specific. We point to the individual mistakes they made, to the part of the equation they got wrong, we encourage their efforts, and praise them for the bits they got right, before helping them to correct their mistake, and pointing them toward the solution. We don’t say “Your problem is that you’re fundamentally INCOMPETENT.” That demotivates people and it’s so vague and generalized that it makes it impossible for them to know how to learn from their mistakes and correct their actions. It’s not helpful to treat other people that way. It’s even more dangerous when we do that to ourselves. The world, however, is full of people who compulsively attempt to motivate themselves through morbid self-flagellation. Get specific; criticize the behaviour not the person; and radically accept that you are fallible just like everyone else.

ConclusionI largely agree with Ellis, and I find his way of conceptualizing irrational beliefs to be simple and pragmatic. It reminds me of a famous quote from the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein:

My aim is: to teach you to pass from a piece of disguised nonsense to something that is patent nonsense. — Philosophical Investigations, 464

We can all recognize rigid demands, awfulizing, low frustration tolerance, and damning of ourselves and others. No more: “I MUST succeed; it will be AWFUL and UNBEARABLE if I fail, and means I’m a total LOSER.” Instead: “I strongly desire to succeed but I don’t NEED to; it would be unhelpful but not AWFUL and unpleasant but not UNBEARABLE if I fail; even if I do fail that doesn’t make me a LOSER.”

After identifying these irrational beliefs, the next step in REBT is usually to actively dispute them, and to continue doing so vigorously each day. Often imagination exercises are used to progressively deepen intellectual insight until it becomes emotional insight, and starts to shape our experience. We then act contrary to our irrational beliefs, carrying out behavioural experiments, to prove to ourselves that we do better when we act “as if” we hold more flexible and adaptive beliefs. And finally, we can begin to make this the foundation of a rational philosophy of life.

PS.

Some people say “But I’m not aware of going around saying any of this stuff to myself!” Sure but we’re talking about beliefs not thoughts. Psychologists tend to refer to the fleeting events in consciousness as “thoughts” and the underlying attitudes that remain fairly constant as your “beliefs”. Let me ask you a silly question: how many beliefs do you have? (Think about it for a minute.) Too many to count, right? Do you walk about verbalizing them all in your head all the time? No. For the most part, almost all of them remain implicit or unspoken.

You could say they’re often unconscious. We’re not looking, though, for deep unconscious repression here. Most of these beliefs are pretty obvious from the way you think, act, or feel. Even if they don’t go around saying “Other people MUST approve of me, otherwise it means I’m a total FAILURE”, many people go around acting “as if” that’s precisely what they believe, because that’s how they feel, at least in certain situations. So for evidence of irrational beliefs, look at how you’re acting and feeling, when upset, rather than simply at what you say to yourself. After all, it’s primarily your feelings and actions that you probably want to change.

Thanks for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life! This post is public so feel free to share it.