Jon Stone's Blog: Stray Bulletin

December 28, 2025

ESSAY / Search More Widely, Look More Closely

View from Craco, Basilicata, 2014

View from Craco, Basilicata, 2014Here is my third or fourth published version of an essay with this title, the eighteenth or nineteenth draft – three times as much of it on the cutting room floor. It used to be a tirade. It’s still too much of a sermon. It’s the imperfect expression of an analysis that informs (and is braided from) my understanding of all that’s going on about me, and it returns in its final paragraphs to poetry, since that’s what I write about most often.

To begin with (and to start with my conclusion, as it were), a list of very strong recommendations:

Search more widely. Look more closely. Look again at what you’ve set aside, what you thought commonplace. Cultivate some degree of suspicion toward whatever fits too comfortably, sits too easily (as if it were a bribe). Side-eye every simple law. Savour, and examine, your own distaste. Apply generosity – or, at the very least, curiosity – where you’re at first inclined to feel nothing much at all. Feel indifference, instead, to stature and fame. Keep expanding the range of what you contend with, attend to. Lean toward the overlooked. Lean away from the overexposed. Read what you don’t enjoy, as well as what you do. Read to be troubled, to be changed, to be shaken loose. Read to be reminded of how much wilderness is out there, and in you, and in the alien depths of other people. Read to make headway into that wilderness. Limit the degree to which you surround yourself with media and furniture that smooths it all over. Build yourself an outpost, not a bunker.

Now, as to the why:

One way of understanding our ongoing predicament is through Manuel Castells’ theory of decentralised versus centralised networks. Simply put: the modern, digitally-connected society can be diagrammed as a dense mesh, with each node linked to numerous other nodes. Information, ideas and value are distributed across the mesh, such that their flow is not easily controlled by any lone actor.

A traditional centralised or hierarchical society, in contrast, looks more like a series of exploding stars: nodes are connected to central, powerful hubs, which are in turn connected to even more central, even more powerful hubs (from patriarchs to churches, landowners and employers, to states, broadcasters, etc). The larger and more central the hub, the greater its control over information, ideas, value.

Two important things to note. Firstly, Castell is modelling the relationship between autonomous units: people, communities, organisations. But the nodes in these diagrams should also be envisaged as concepts, ideas and symbols that have taken on a life of their own. Participants in a society do not blindly follow the whims of people and organisations higher up the chain; they’re also loyal to shared internalised principles, traditions and habits of thought. For example, ‘the nation’ is arguably a more central, more powerful hub than ‘the state’. ‘God’, ‘human rights’ and ‘science’ are all mega-charismatic concepts; people cluster round them and categorise one another according to who follows what.

Second important thing to note: we are not really living in a decentralised network at all, but a chaotic hybrid of the two models. Not an earth-shattering revelation, I know (“The old world is dying and the new world struggles to be born”) but it’s useful to diagnose the problem in precisely this way: the more centralised and hierarchical the society, the greater the requirement for equilibrium across and between its various hubs. To the extent that equilibrium is shaken, conflict ensues, as different centres of influence vie for power.

This loss of balance is unavoidable. As a society grows, grows more diverse, mingles with other societies, discovers new physical and intellectual machinery, encounters more problems and requires more specialist knowledge, the chances of hierarchical equilibrium being maintained get ever less likely. “The centre cannot hold.” The decentralised network emerges not just as the result of advances in communication technology, but as the only viable alternative form of civilisation outside of a totalitarian state.

For many, this process feels like a great, continuous unravelling. The past, it seems, was somewhat coherent, orderly; the present is full of contradictions, and the future looks unfathomable. This is no recent development – here is Stephen Spender, in The Struggle of the Modern, 1963:

“From Carlyle, Ruskin, Morris and Arnold, to T. E. Hulme, Ezra Pound, Years, Eliot, Lawrence and Leavis, there is the search for a nameable boojum or snark that can be held responsible for splitting wide apart the once fused being-created consciousness. The Renaissance, the puritan revolution, have all been named as villains. There runs through modern criticism the fantasy of a Second Fall of Man.”

It’s amusing to read this today, amidst a never-ending flurry of hare-brained treatises locating the downfall of Western civilisation somewhere in the last half-century. Clearly, the theory of a historical ‘wrong turn’ is comforting to some; the alternative is to accept that whatever end is coming has always been coming. Or, if we are prepared to put serious effort in, to make it a beginning, rather than an end.

Easier said than done, of course. Not only is there a practical need to retain some sort of centralised network – standardised tax and legal systems, national and regional governance and so on – but it’s also tough, psychologically, to do without the assurances a balanced hierarchical system gives you. Where is your place in the decentralised network? Who serves you, and whom do you serve? How do you categorise other people? What is it that unites us?

People’s attempts to answer these questions vary wildly and are often totally incompatible. In place of ideas like ‘the nation’ and ‘God’, which once served as the most central of all societal hubs, we have various woolly principles that excite a lot of support when named but (and increasingly) deepen conflict when used to adjudicate. Take ‘freedom of speech’, for example – it sounds appealing, and suggestive of the kind of bedrock principle all could agree on. In practice, though, there is insufficient consensus on what it means for it to function as any sort of social glue. ‘Basic decency’, ‘civility’, ‘justice’ – important concepts to debate, but none of them markers of commonality, or explanations of who we are.

Lacking ways to locate themselves in the broader panoply of their society, individuals are susceptible to the lure of the cult and the coterie, and of fantasy worlds: smaller, less unwieldy spaces in which they feel more secure in their purpose. Fandoms, followerdoms, fictions and games, clubs, sects and scenes of various types. These are also social hubs, of course, often with their own hierarchies, but their relationship to one another and to traditional institutions is often ambiguous, even vexed – a melange of counter-cultures, a jigsaw where every piece is from a different box.

Is that good? It can be. As well as offering temporary relief from the pressing question of where and how we otherwise fit in, these smaller networks can act as a sort of mental gymnasium, in which we exercise the very cognitive muscles we need to make sense of our wider surroundings, so that we grow wiser and more considerate.

But it can all go wrong in two ways. First, a minor cult or fantasy scene can become so fundamental to a person’s sense of belonging that they cannot contemplate its loss, its displacement, or even its evolution into something else. (See, for example, the reaction of male gamers to relatively tame feminist critique, and to the game industry’s ongoing pursuit of a more mainstream market. See also some of the darker manifestations of stan culture).

Secondly and perhaps more obviously, a cult can be a crucible in which a person’s entitlement and sense of disconnection from wider society is relentlessly fed.

This is where opportunists and power-hungry egoists enter the picture – and capital, of course. Like all drug-pushers, they exploit and feed a deepening cycle of pain. In their hands, the cult or fantasy is not a respite, nor a doorway to a richer understanding of other people, but an endlessly withheld promise of better things to come. Buy into it, goes the promise (whether with literal money, or devotion) and the whole world will be remade. You will now be at the centre of it. Whether that is because your new, expensive possessions will make you more confident and efficient, or because alien invaders will be repelled and proper roles and expectations reinforced, your pain will be excised. But only if you buy, buy, buy.

Now we have the only formula we need for resurgent fascism and other reactionary movements, as well as conspiracy theories, obsession-fed loneliness and frantic, self-destructive excess. The manosphere. Eugenics. Nativism. Internet Gaming Disorder. Incel culture. Lots more besides. Of course, all have other causes as well – but I would argue that a major driving force behind each of them is horror and rejection of the decentralised society, and the idea of being adrift within it, to the point where the normal socialising instinct becomes utterly warped.

Two questions, then: 1) What do we do about it?, and 2) Is the same malady also, as some would contend, an explanation for (and hence reason to dismiss) left-wing activism, and identity politics in particular?

I’m going to take the second of these first, because it touches on an important nuance, which is this: challenging the current state of society remains a legitimate enterprise. There are a vast number of problems to be solved and a large number for which no past iteration of society had anything close to a solution. The centralisation of pure power in a sprawlingly complex modern society is corrosive – particularly where there is no holding it to account, as in the case of massed wealth, authoritarian states and corporate thuggery. The failure of our political systems to adequately distribute wealth and opportunity exacerbates all problems, and further radicalises everyone in the camps I’ve listed above.

There’s nothing, therefore, inherently wrong in advocating for radical change. As George Bernard Shaw said, “All progress defends upon the unreasonable man.”

There is, however, a difference between doing so out of a sense of social responsibility, with due consideration to the needs of all members of a society – with little expectation, even, of direct personal benefit – and doing so as a form of self-aggrandisement, in order to be vindicated or to see one’s enemies vanquished. Reactionary/right-wing radicalism is almost entirely rooted in the latter. It flows from the conviction that there is a natural, non-arbitrary order that must be restored or permitted to take shape – usually something that revolves around patriarchs, churches and great men, with ‘Western culture’ or our old friend ‘God’ as unifying concept – and that in this natural order I, the right-wing radical, will get my due.

To test this hypothesis fully, it must destroy most of the culture that currently exists and brutalise or murder a lot of people. But according to its own moral logic, that’s fine – the victims are worthless in the soon-to-be-established scheme of things.

Even allowing for great calamities, sweeping political victories and mass murder, the right-wing radical will never see his dream come true – his existential crisis cannot be solved in this way. This means he will continue to fight and hate, and to be a perfect instrument of societal rot – one whom political conmen can rely on as a stepping stone to power.

Purveyors of identity politics are accused of being in much the same boat, except that they seek to invert traditional hierarchies and install different sacred certainties. And while it’s true – unavoidably so – that some of the individuals who undertake this kind of activism use it as a vehicle for a bottomless grievance, or are lesser opportunists, the ideas themselves are insufficiently grandiose for this to be endemic. They primarily concern shifts in language, organisational policy and moral posture – aims to which, as is frequently pointed out, it is trivially easy to pay lip service. Their effect is often characterised as insidious precisely because it’s so limited in scope.

Complaints against identity politics are voluble, nevertheless, because it’s a form of activism that increases the degree of complication and anxiety at surface level. People and organisations scramble to keep up with recommendations on the best pose to strike, which words and phrases to adopt and which to dump, who carries the most moral authority in any given situation, and so on. Each digs their heels in at different points, leading to acrimony, and to two sides of a relatively minor matter going at each other for years on end.

In other words, identity politics insistently draws attention to the fact that a decentralised society has to negotiate its terms with itself, and that all accords are temporary. Activists keep re-opening negotiations, sometimes re-opening wounds in the process. Where right-wing reactionism seeks to reforge absolute certainties, the left, it seems, means to contribute to the unravelling effect we all feel. (This is why, incidentally, Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida have become the unlikely poster boys for civilisation’s downfall in the eyes of the right-wing commentariat, since it is they who popularised what ought to be, by now, an entirely uncontroversial observation: that we are making it all up as we go.)

There isn’t space here to explore the exact extent to which identity politics is indicative of the left’s approach more generally, so I will simply make a tendentious claim: unlike conservatism and the far right, which are obsessed with the reinforcement or reimposition of cultural hierarchy, left-wing politics – broadly, and despite its tunnel vision in some areas – anticipates a future of constant flux. It emphasises struggle, protest and fuss-making because it does not envisage a point where we will again be able to trust some fatherly centre of power.

Which leads me back to my first question: what can we do to make that future less dangerous? What is to be done/isn’t being done already about the widespread toxic inter-alienation I’ve described above?

In an ideal world, we’d see more government intervention in the spread of inflammatory, cynical propaganda. First, however, we’d need governments who understand what inflammatory, cynical propaganda is, or who don’t actively promote it for their own ends. So let’s put that problem aside for now and think about what ordinary people can do, outside of direct political activism.

A lot of what I see proposed still amounts to some kind of re-centralisation. Not as hierarchical as the right envisages – more a sort of coming together. People talk over and over, for instance, about the importance of community – and while this sounds entirely right on its surface, it seems what they’re often envisaging is a freshly reimagined, powerfully attractive group identity.

I don’t think this can be magicked up. Any approach that is, in some sense, one of bringing stray lambs back into the fold is likely to fail, because we cannot agree what the fold ought to look like.

Similarly, a lot of hope seems to be placed in the idea of strong figureheads, role models and leaders emerging. Leadership of some kind is a necessity – anyone who has ever tried to decide anything as part of a large committee knows that. But a head can’t function without a body, and leaders and figureheads nearly always let us down, sooner or later.

So the way I see it is this: we need to get better at being a decentralised network.

What does that mean? It means we need to make an effort to get outside of the clubs, cults, sects, scenes, fandoms, followerdoms, games and fictions we most agreeably inhabit, and find ways to connect them up with others. Rather than simply tuning in to the frequencies we already think in, which are personally affirming – rather than armouring ourselves in these to weather the maelstrom of everything else – we ought to be habitually testing others, trying to find points of overlap, ways in which they rhyme.

This is, in a sense, to echo another famous statement, José Martí’s “The knowledge of different literatures frees one from the tyranny of a few” – but applied to more than literature.

It involves, I think, some degree of detaching ourselves from the centres of each of these little worlds – consciously working against their centripetal pull (their tyranny, if you will). That means paying less heed to the people, organisations and events that most powerfully define each scene. It means giving less thought to noteworthy figures and brands, to what everyone else in that particular social hub is talking about, and looking instead to the fringes of their orbit.

Yes, this is a way of saying “Try to stop fawning over famous people”. It’s also a way of saying “Try not to be a culture snob”.

Consider that our tendency to heap attention (and compassion) on the already-glutted all-too-often leads directly to abuses of power. How corrosive it is when people defend harmful acts because the perpetrator, whom they do not know, is somehow important to them.

Consider also that our lack of interest in, or warmth toward, those not gilded by success and adoration – especially when they belong to other clubs and scenes – is what really robs us of our sense of community. There’s great wisdom in “Love thy neighbour” as an edict, and we should be able to do so without need of a baseline of commonality. ‘Loving’, in this context, should mean being willing to value differences.

Consider, thirdly, that it’s better, as a matter of personal resilience, to be a member of many distinct, over-crossing realms of thought and interest, to have many different strands of identity – so that as and when one of these becomes less of a home, less of a good fit, you have others to take refuge in. We want to avoid being the gamer who turns on women for ‘ruining’ his hobby. Or the faded star who has nothing but bitter contempt for those who’ve taken his crown. Or even the sensitive millennial left bereft when their hero author is revealed as a monster. Nothing outside of our close personal relationships should be so central to our idea of who we are that we cannot let it go.

So we are aiming for tensile strength at two levels. A decentralised society is made up of many smaller societies. For it to resist tearing – for it to not be vulnerable to violent revolt from those who want to impose arbitrary order – its smaller parts should not just meet at their edges, but be messily, tightly, inextricably interwoven. Similarly, for an individual to have real durability – for them to be able to withstand their safe certainties being obliterated – they need to be suspended within a web of possible selves.

Or, as John Berger writes about Chaplin’s Tramp:

“Every time he falls, he gets back onto his feet as a new man. A new man who is both the same man and different. The secret of his buoyancy is his multiplicity. The same multiplicity enables him to hold on to his next hope, although he is used to his hopes being repeatedly shattered.”

Yes, this is contrary to some aspects of our nature. We like being followers. We like regulation, a sense of order. That’s why this still needs to be something of a sermon. It’s why ‘search more widely, look more closely’ has to be a command, a mantra.

The part of our nature that likes to grip the same hand-rail every day is failing us. It is ill-suited to our predicament. So we must try to become something better. As Jonathan Miller said in a debate with Enoch Powell in 1971, “Difficulties are in the nature of human co-existence (…) Social cooperation is a hard and difficult thing.” But it can be hard in a way that precedes expansion and enrichment of the mind, or hard in that we are just beating at the walls, asking for the guards to come in and flatten our enemies.

I echo what Miller went on to say: “What I ask for is … a sense of the variety of human existence and also an attention to the capacity of human beings to absorb each other’s differences.”

Part 2 (the much shorter part): Poetry

Part 2 (the much shorter part): PoetryIn my list of strong recommendations at the beginning, I should have included: Read lots of poetry. Writing and publishing a poem costs little in both time and physical resources – arguably less than any other artform – which means a fairly wide range of people earnestly attempt it at some point in their lives. Some percentage of those then work sufficiently hard at mastering the associated skills that what they produce can be said to bear more than a trace of their own uniqueness. To read across many poets is, therefore, to encounter many intimate perspectives and styles of thought.

But as poetry is also a kind of scene, it serves as an appropriate case study for me to end on – especially since the manner in which it’s avidly recommended, marketed and talked about all too often falls into one of the traps I’ve described above. What I mean by that is: poetry is simultaneously offered as a means of withdrawing deeper into one’s own world, and as a way of reconnecting to some inscrutable shared human essence which the poem documents. Neither framing is very helpful, either to us as a struggling society, or to poetry as an artform.

I won’t quote from specific promos or book blurbs. Instead I’ll try to summarise three of the general ways in which the value of a particular poem or set of poems is communicated: “Read this – it will touch your heart.” “Read this – its themes and ideas are universal.” “Read this – it’s a work of supreme and dazzling merit.”

Taking those promises in order, the first sells reaffirmation (and manipulation) of a person’s existing sympathies and fondnesses. So much already exists for this purpose, and poetry is not especially well-suited to the task. In fact, I’d argue that the persistent presence of this expectation is one of the reasons most readers don’t get on with the artform; little speaks to them directly, and little ever could, because of our increasingly distinctness from one another. Poetry is far better suited to capturing those distinctions; it challenges us to extend our sympathies and fondnesses, because its weirdness is the weirdness of others we don’t yet know or understand.

Then comes the next promise: “Read this – its themes and ideas are universal.” Similar objection: no, they aren’t. There are no universal themes and ideas, and encouraging a small number of readers to think that the point where their own perspective aligns with the poet’s represents something neutral, apolitical, primordial – above the petty disagreements of others – is only likely to make them more stubbornly closed off to other systems of understanding. Areas of commonality between the concerns of poet and individual reader, reader and reader, poet and poet are always likely to be numerous, and recognition of them may occasion revelatory joy, but this ought to be seen as a starting point, not the purpose of the exercise.

“Read this – it’s a work of supreme and dazzling merit” may just signal harmless enthusiasm. Such recommendations go awry insofar as they imply a universal scale of quality — positioning poets as literary darts players all aiming for the same spot on the dartboard. We should be very wary of this – often, a narrow aesthetic criterion is simply a codification of a person’s taste, and their taste exists solely to avoid tangling with the unfamiliar. In other words, it becomes just another way of affirming a static perspective – “I like it because it’s good” as a front for “It’s good because I like it.”

On top of that, this particular promise is usually an attempt to set the poet on a pedestal – to recommend them as grand, leaderly figure, as cultural lynchpin. So too is it often made in the same breath as a disavowal of most of the rest of the poetry available and/or a lament that poetry has lost or abandoned its cultural centrality. The overall strategy, then, is another weak protestation against the decentralised society and attempt to restore a charismatic hub.

We can see the negative effect of this in the numbers of people (many, in my experience) who dismiss nearly all contemporary poetry on the basis that it doesn’t adhere to the same arbitrary rules as poetry from 150 years ago. What they mistake for exacting standards is actually a peculiarity of taste that cuts them off from a substantial vein of up-to-date intelligence. They are convinced great poetry is of importance but have closed their minds to most of the forms it might take – like those who, awaiting the Second Coming of Christ, will accept nothing less than a halo’d man in tunic and beard.

We see a further manifestation of the effect of each of these sales strategies in recent research showing that in a blind test, people prefer A.I. poetry to work by even long-canonised poets – deeming the A.I. pieces to be warmer, more ‘human’, more formally competent and fuller of feeling. To be clear, they still didn’t like the A.I. poems enough to want to read more, but the A.I. achieved its goal of showing them something comfortingly familiar – a version of other human beings’ ways of thinking and meaning that reflected their own limitations of imagination back at them.

That is, to my mind, a strong indicator of how we might lose the battle: by choosing that which makes immediate, vague sense over that which is harder to fathom but more truthfully represents the tremendous variation in personhood among our communities.

These sales strategies also cause strife and division within the poetry scene itself. It’s not unusual now to see even relatively successful poets bemoan slipping standards – or even, in the manner of Carlyle et al, describe some kind of great recent catastrophe – without any evidence but the fact that increasing numbers of poems do not speak directly to their heart, or conform to the criteria they developed to codify their increasingly out-of-touch tastes. For all that it teems with articulate writers, the scene struggles to have meaningful conversations with itself, falling instead into rhythms of contestation: who is or ought to be ‘winning’, etc.

And unfortunately, because these strategies are still thought to work, the range of contemporary poetry which is pushed hardest on the public is not very representative – often limited, in fact, to work that deals in already emotive subject matter and relies chiefly on this for impact. What’s missing is widespread understanding of the fact that for reading to contribute to any kind of societal closeness, it must involve work on the part of both writer and reader, that the distance cannot be closed from one direction only. In its place is the much more troubling idea that our reading, like our other pursuits, ought to reassure us that we belong to a core (a corps, even) of right-thinking people.

So there is my case study. Poetry is an artform that, to my mind, speaks to our sincere efforts to function as a decentralised network – to find other ways to connect to one another, and to trust one another, without the need of an absolute common denominator or charismatic centre. But because old habits die hard, it remains a frustratingly marginal art, beset by thoughtless factionalism, dressed up as something it isn’t.

I see this as indicative of a general pattern: reason to believe we are becoming something better, on the one hand; on the other, reason to think we’ll keep clawing at the ghosts of centralised networks until we come apart at the seams. So I make my list of recommendations, as found at the beginning of this essay, to myself and to you, in the hope of lending my shoulder to the former. Happy New Year.

December 23, 2025

10-Day Icy Advent Calendar #10: Ice Dive

It’s a shame we can’t embed playable text into Substack, isn’t it?

It’s a shame we can’t embed playable text into Substack, isn’t it?Also a shame that I didn’t have time to make a new version of Ice Dive, as I’d been planning to. This version is a little buggy, the mechanics are unbalanced and many of the lines need further shaping and shuffling.

But I wanted to end the advent calendar on a ludokinetic poem and this is the only ice-themed one I have — even counting the many pieces sitting around in various states of completion in the workshop. It was originally devised so as to be playable over a Zoom call — the player merely has to shout “Stop!” when they want to come up for air, whereupon I (the person in control of the game) click once to bring them back to the surface.

For what it’s worth, it is possible to finish the game, collecting all seven pieces of the ‘something’ it is you’re collecting. I’ve only managed it once, though.

December 22, 2025

10-Day Icy Advent Calendar #9: Or, from the Mountain

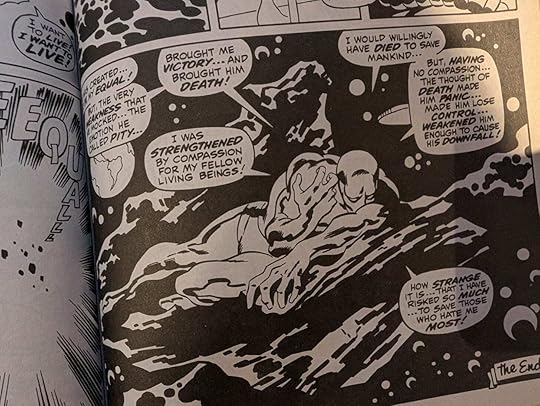

It’s a short sequence of superhero poems — comic-book-based, since the Marvel Cinematic Universe hadn’t really made its appearance yet. For this little advent calendar, I should arguably have revived ‘Iceman’ — but I’m not sure that poem has a lot of heart or depth to it, and I’m not quite as invested in Iceman as I am in the Silver Surfer.

The Surfer, of course, appeared in this summer’s Fantastic Four: First Steps, portrayed by Juliet Garner, in a mildly controversial (though ultimately inconsequential) bit of casting. A male version, played by Doug Jones (of Pan’s Labyrinth and other monster movies) appeared in 2007’s Fantastic Four: Rise of the Silver Surfer — Jones did a better job of brooding philosophically, aided by Laurence Fishburne’s baritone voiceover, but neither portrayal really connected with the version of the character I’ve found most affecting, which is rooted in Stan Lee and John Buscema’s run of Silver Surfer comics from 1968 to 1970. Here, the Surfer is almost wretchedly noble and introspective, frequently shown in poses of contorted anguish as he faces godly adversaries, existential crises and the self-destructive stupidity of vicious men.

“In every voice … in every human heart … a smouldering hostility!” he laments, squatting on a rooftop while Spiderman tries to pick a fight with him. The messaging is fairly crude — these are comics for children, after all — but it remains refreshing, even today, to read about a superhero who is made vulnerable, even driven to despair, by his sensitivity to man-made horror.

Why is this version of the poem called ‘Or, from the Mountain’? I suppose because I wanted to revise it into something with more of a folk flavour. What if, rather than being coated in silver, the character had an association with orichalcum, the mythical metal referred to in Ancient Greek texts (from ὄρο / óros / mountain and χαλκό / khalkós / copper)? The mountain as a source of power, rather than the space god Galactus, is also a little more grounded.

December 21, 2025

10-Day Icy Advent Calendar #8: White Dead-Nettle

It’s got something of the Batrachomyomachia about it (also referenced in the only podcast episode I’ve ever uploaded to Substack) and emerged from my wanting to do something with a bunch of tiny poems I’d written for Christmas cards some years back. (Long-term readers will recall that Unravelanche also started as Christmas card poems). Since I’m still working on it, and since I’m nearly at the bottom of the bag in terms of previously published ice-themed poems, I thought I’d use the advent calendar as an excuse to add one more soldier to the crew.

December 14, 2025

10-Day Icy Advent Calendar #7: "The iceberg is back ..."

It’s eight years since we published

Aquanauts

.

It’s eight years since we published

Aquanauts

.If I won the lottery, one of the things I would pour money into is revisiting Sidekick collections like this one and building new, luxurious expanded editions. Aquanauts was sprawling in a sense — it moved from ponds to deep-sea creatures — but there was so much more it could have covered, had we the time and money to bring on board more contributors, or commission the ones we had to do more work. I would have loved a whole section on the arctic.

December 12, 2025

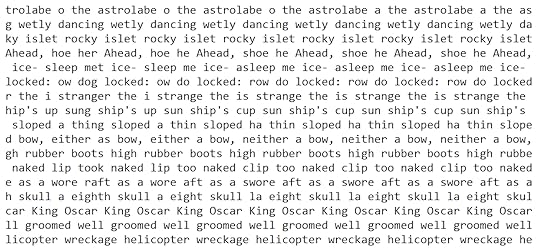

10-Day Icy Advent Calendar #6: Another Labyrinth

You might have to try landscape mode. If any of the lines are broken, it’s unlikely to make sense. Sorry about that — I should probably have uploaded it as an image. Apologies, also, for it being six days late, if you were actually following this as a 10-day advent calendar! As long as I can manage ten within the normal 24-day period, we should be fine, right?

Dick Higgins calls this form ‘leonine verse’ in Pattern Poetry: Guide to an Unknown Literature, but I can’t find reference to it anywhere else. In fact, Wikipedia has an entry for ‘leonine verse’ that describes a totally different form. Whatever you care to call this, it looks more complicated than it is — each stanza is really a couplet, but the second and fourth (or, alternately, the first, third and fifth) metrical foot of each line in each couplet is identical. These are placed in a third line that sits between them and is read twice, once as part of the first line, once as part of the second. Effectively, the lines are woven together.

Also, if you read it across diagonally from just inside the top left corner, it goes snow, snow, snow, snow.

December 7, 2025

10-Day Icy Advent Calendar #5: Shadow from a Future Zone

I can’t speak or write Japanese, but using a combination of Google Translate, Wiktionary and existing English versions (in this case Robert Pulvers’ translation from Strong in the Rain: Selected Poems of Kenji Miyazawa), I sometimes write down versions of Japanese poems in English. I published a few in School of Forgery because the underlying theme of the book was ‘the volatile relationship between fakery and invention’.

“Immature poets imitate; mature poets steal,” goes the well-worn Eliot quote. It continues: “Bad poets deface what they take, and good poets make it into something better, or at least something different.” But isn’t the defaced object automatically made different? Did he mean that it should no longer bear any resemblance to what it once was? That is has to have been pointed to a new purpose? One thing I like about remakes and readjustments — the principle of them (something which seems to occupy film-makers more than poets) — is how they make it seem as if the paint is not yet dry, as if nothing is really finished.

December 4, 2025

10-Day Icy Advent Calendar #4: The Ice Pilot's Dream

This is a stereogram poem.

This is a stereogram poem.The form has not taken off in any big way as far as I know, in part because hardly anyone, it seems, is able to read them. It takes me some effort every time I test it. As with conventional stereograms, the trick is to cross or unfocus your eyes, or start with the screen close to your face before drawing away, until one set of words stands out from the rest. In this case, you’re looking for a narrow strip just left of centre.

In God’s name, why? Well, it ought to have something to do with the meaning of the poem, of course, and for that reason my only examples of the form are what you see here (where the business of reading the poem is supposed to mimic the act of squinting through a snowstorm, trying to make out a distant object) and a set of three ‘masks’, such that holding the page up to your face simulates putting the mask on. You can read those in Look Again: A Book of Hidden Messages, under a pseudonym.

December 3, 2025

10-Day Icy Advent Calendar #3: 'Undoing'

Unravelanche is really a very short story divided into prose poems, interrupted by snowy collages. But it’s standard practice in literary writing these days to present extracts from other works, shorn of context, and I’ve found I rather like doing it. I’m a little addicted to it, in fact. So now I’ve done it to myself.

December 2, 2025

10-Day Icy Advent Calendar #2: Icicle

This may have been what I had in mind when I wrote this, since it reads as a brief entry in a pocket directory. Or I might have been remembering an account of the murder of Trotsky from an old Eagle annual. Likely I was browsing Observer’s Books at the time as well. It’s an exercise in fuzzy rhyme — a term Andrew Osborn uses to describe a technique deployed repeatedly by Paul Muldoon, where roughly the same group of consonants is repeated in a different order.

Actually, I’ve formularised this much more rigidly than Osborn — Muldoon’s rhymes are often very fuzzy indeed, to the point of challenging readers to pick out any kind of marked similarity of sound. I don’t find this as satisfying as Muldoon’s many avid fans seem to; I was much more taken with the idea of trying to find as many words and short phrases as possible that use the same set of consonant phonemes in a slightly different order. It’s a variant of the anagram-rhyme technique I picked up off Roddy Lumsden and used in ‘Mustard’ — probably my most successful poem in terms of reach.

Of course, it’s hard to get it exactly right. ‘Lackeys’, ‘killers’ and ‘colours’ end in a /z/ rather than an /s/. I like the movement from ‘silk’ to ‘skull’ to ‘slake’ though, especially as it’s a sort of imitation of the noise of dripping water.

Come to think of it, at the time of writing, I was playing a lot of Team Fortress 2, a game in which you can play a balaclava’d spy armed with a ‘spy-cicle’. When you use this to stab a member of the enemy team in the back, it instantly transforms them into an ice statue, back arched in pain.

Stray Bulletin

- Jon Stone's profile

- 3 followers