Rachel Lyon's Blog

November 18, 2025

Northward Through Mirkwood

Hello from wintry New England, where we returned Sunday evening after a joyful weekend in NYC. Because my rather obsessive five-year-old has gotten into audiobooks, we listened to The Hobbit practically the whole ride home. How dramatic it was to hear about little Mr. Baggins and the dwarves traveling Northward through Mirkwood to brave the lair of Smaug as we too drove northward, from the colorful leaves and blue skies of the temperate city and through brief thunderstorms and rainbows to the icy roads and snowy winds of Western Mass, where the gray trees are waggling naked in the bitter wind outside my window as I write this, with a cup of tea and the space heater going by my side.

Which . . . very hobbit-like.

AI: mostly evil, but useful for generating images of hobbit houses.

AI: mostly evil, but useful for generating images of hobbit houses.No shade, but I never got into Tolkien as a kid. He is obviously not great re: female characters (just one problematic thing for which he has been critiqued in recent years), and as an excessively girly little girl I only read books about female characters unless someone forced me to do otherwise. As you can probably tell, however, as an adult I’ve been enjoying it, consuming it as I am for the first time with my kids and via the energetic narration of Andy Serkis, a.k.a. Gollum himself. It’s also fun to finally understand a bunch of cultural references, not least the reference by our neighbor-friend down the road, who has more than once referred to us a hobbit family, because we are all pretty small, and three of four of us have unusually big feet.

That it’s too advanced for the three-year-old doesn’t seem to matter. She gets some general gestalt of the story and enjoys the sounds of the various words and phrases. Over dinner last night, as we all collectively tried and failed to remember the names of the dwarves (Dwalin, Balin, Kili, Fili, Dori, Nori, Ori, Oin, Gloin, Bifur, Bofur, Bombur, and Thorin, so fun), she proposed a few creative nonsense names of her own. The narrative is also, admittedly, pretty advanced for the five-year-old, who will occasionally admit he has no idea what’s going on, and/or ask to pause the audiobook so I can give him a brief synopsis. More often than not, though, he gets bored midway through my explication and asks that I start the story up again. It’s very curious to me that he wants to keep listening despite not entirely understanding it.

Curious to try to parse how much plot he actually comprehends. Plot seems to be the hardest to grasp; he has apparently absorbed a lot of character, setting, scene. He is capable for instance of describing every detail of a dramatic set-up, but his understanding is pretty limited re:, like, the characters’ motivations, and what’s happening in the story more globally — and, crucially, why. This is, of course, in part, a developmental limitation of his specific, five-year-old brain, but it’s a shortcoming he shares, unfortunately, with many a college-aged student I’ve known, and many grown-ups, too — especially when we are distracted (which! in the distraction economy!? when are we not!?).

What I’m saying is, we all need practice consuming and considering long stories, if we really want to understand them — not to mention how they are put together, and why.

Thanks for reading Postcards from Mountain House. If you have a friend who might like it, please

It’s been months since I last posted here, which is mostly because I’ve been working rather obsessively (a genetic trait, perhaps?) on retyping my third book. This retyping process made up the bulk of my most recent round of revision, the one which brought the book to what I am thinking of, at this point at least, as some kind of early finish line. It was a dumb and straightforward as it sounds: after doing a few early edits I knew needed to happen, I opened the most recent draft, created a new document, and, split-screen, began typing the book again from the beginning, fixing problems little and big as I went.

It was a time-consuming, painstaking, and often rather boring editorial pass, but, if you’re a novelist, I can’t recommend it enough. For one thing, as authors of long projects, I do feel we really owe it to our readers to reread our whole manuscript, start to finish, and fix it up nice before we send it out, whether to editor, agent, or friend. But if you, like I, find it difficult to read anything without skimming a bit, here and there, now and then (in this economy!?), you probably find it even harder to read your own words without skimming. After all, you know them so well. Retyping forces me, anyway, to slow the fuck down and really consider every dangling modifier, every lopsided sentence, every sloppily constructed paragraph, every stupid line of dialogue, every cliché, and methodically replace each unfortunate incidence with something fresher and truer.

sticker art by Meghan Hopkins Sokorai

sticker art by Meghan Hopkins SokoraiIt is not just the minutiae, however. I’ve also found that retyping the book in this way, from front to back, with as fiercely critical an eye as I can muster — and, crucially, over a relatively short period of time — allows me to identify overarching plot issues that I may have missed when I was drafting, then revising. After all, writing a 300-or 400-page book takes literal years of one’s life, and life does not pause to accommodate the process. The component parts will always have been assembled piecemeal, in bits and bobs and through comings and goings and cuttings and pastings and puttings-aside, with less attention to their place in the whole than to their individual excellence. Due to this problem of chapters having necessarily to be hewn separately before assembly, it’s common to find, post-assembly, that key elements of the overarching narrative have been omitted due to lack of foresight, or accidentally dropped, or glossed over, or forced to fit together when, actually, they don’t really.

The process of retyping feels slow amidst the trees, but looks quick from above the forest. Rereading my book as I retyped it, word by word, over the course of a compressed couple of months, allowed me, I found, to more easily keep the whole thing in my mind at once, and therefore identify what was missing and what was redundant or extraneous, what belonged and what didn’t.

It’s similar, in fact, to listening to a long audiobook, in that both processes force the reader (and/or writer) to consume the narrative both at a slower rate and via different sensory input than she otherwise might (aural, tactile). The effect of this, I feel, I suspect, is not only a kind of forced, sustained attention, but also an improvement in memory and, therefore, narrative comprehension. If you have a child you are probably familiar with a certain conversation in the learning world about multisensory learning. Turns out it has been proven to improve memory even in house flies.

Anyway. Now that I’ve completed the long process of retyping the book and sent it to my agent, I’m having trouble knowing what to do with myself. I feel like I’m in a kind of anxious, unsettled creative purgatory, too distracted to read, too anxious and invested in the current novel to start working on something new. It takes, I am ashamed to report, a non-negligible amount of self-control to refrain from writing my agent daily with hideously needy requests for an update: Have you read it yet? Do you hate it? Are you obsessed with it? It’s been 1 day, 2 days, 3 . . . You don’t have other clients, right? You don’t have a family, a life? Can we sell it, though, do you think? For a zillion? Half a zillion? A quarter zillion, maybe? Do you think it has a shot at winning a prize or two? Should I throw it away and start a new life? Should I just die?

What do you do when your personal energy is so annoying you can’t even stand yourself? You write something on Substack? You clean your house? You listen to audiobooks? You Hobbit.

There is honestly so much that is so deeply pleasing about Bilbo Baggins as a protagonist. Let’s start with his name. It’s delicious to utter. Then there is the fact that he is such a very unwilling hero. As a Taurus, I can sympathize utterly with his wanting always to be back in his cozy hobbit-hole, eating many delicious meals and dozing by the fire. And yet he is chosen, despite himself, due only to his own begrudging goodwill and hospitality, to go off on this very uncomfortable adventure, into the darkness. He is frightened and complains frequently but it must be done, and, turns out, it must be done by him, and by doing it, he finds he can. There’s this one moment that really got me, when he’s almost made it to the dragon’s lair. In the tunnel in the mountain, our unwilling Mr. Baggins hesitates:

It was at this point that Bilbo stopped. Going on from there was the bravest thing he ever did. The tremendous things that happened afterward were as nothing compared to it. He fought the real battle in the tunnel alone, before he ever saw the vast danger that lay in wait.

Our five-year-old is a pretty sensitive kid. Most movies, even kids’ movies, stress him out too much for him to really enjoy them. He frequently asks for reassurance that no one will get hurt or die. Listening to The Hobbit with this kid, however, I’ve noticed that, although he is thrilled by the book’s many scenes of imminent peril, they do not seem to upset him. When I have paused the audio, at key moments, to check in with him about how he is feeling, whether Bilbo is facing bloodthirsty goblins or sadistic giant spiders, the kid seems completely into it, a bit worried maybe but game to keep going. Part of this is growing up, of course. He has literally grown an inch a month since summertime, and one can only imagine how busy his little brain has been, constructing new neural pathways. But part of it, I suspect, has to do with the nature of story, in and of itself.

We tell — we crave — stories about what scare us. Hauntings, killings, stolen children, murdered wives, serial killers: to experiment with these subjects on the page, as writer or as reader, is to process our fear slowly, with nuance and distance, and from varied angles. I think I am drawn, as a writer, to stories about losing the people we love, because that is what scares me most. I can only imagine that the endless proliferation of true-crime podcasts and TV has to do with our reckoning, as a culture, with some of the same — and with the political and personal distrust that has been fomenting in our ever fractured communities, and with a fascination with our own darkest selves, and on and on.

A book-length narrative, however, consumed slowly, forces our confrontation with all those frightening things into a kind of contained intimacy. We trust the author, particularly when we are familiar with the tropes of his craft. We believe that he will be honest with us, and (probably) not murder his protagonist, our avatar. We are invited to understand what frightens us through the lens of a fictional character’s perception. We are in control, too; we can close the book at any time and abandon it. So the unsafe becomes safe.

May 16, 2025

Revision (2): Coincidence and Boredom

I am barely more than halfway through a second revision of this new manuscript.

It’s not going great!

At the risk of self-indulgence—and in the hope of reaching someone who is also struggling!—I’m going to tell you about it.

I began this revision (re-revision?) with vigor and conviction, buoyed by the collective wisdom of my generous beta readers, ready to make something pretty good into something pretty great [avoid superstition] something with the potential for greatness. I took tons of notes and compiled them by chapter. I wrote a whole new beginning, which extends the already very long (48-year) timeline by another six years. I approached the subsequent chapters as if with oversized, nihilist scissors, lopping off great chunks of prose, killing darlings left and right.

An elder millennial makes elder millennial references.

An elder millennial makes elder millennial references.Something interesting happened during this process—the good part of the process, I mean. The revisionist’s frame of mind brought with it a particular and prickly awareness. I had been noticing scenes in the manuscript, relics of its first draft, which echoed one another. (Why do my characters have two, separate, totally unrelated conversations while waiting for an elevator? Why do we see these musicians play essentially the same show, twice?) In that mental context, unconsciously, then consciously, I started noticing more real-life coincidences, very often nothing special, very often very small, so insignificant I felt like a cuckoo nut bringing them up. Did you notice that you said the word yield at the exact moment we passed a yield sign? I asked my husband. How curious that our 4-year-old is obsessed with turtles this week, the very week I happen to be reading a book about people who become obsessed with turtles! How doubly curious that Turtle Diary is itself about coincidences:

Something very slowly, very dimly has been working in my mind and now is clear to me: there are no incidences, there are only coincidences. When a photograph in a newspaper is looked at closely one can see the single half-tone dots it’s made of. There one sees the incidence of a single dot, there another and another. Thousands of them coinciding make the face, the house, the tree, the whole picture. Each picture is a pattern of coincidence unrecognizable in the single dot. Each incidence of anything in life is just a single dot and my face is so close to that dot that I can’t see what it’s part of. I shall never be able to stand back far enough to see the whole picture. I shall die in blind ignorance and rage.

(Side note: do read Turtle Diary, by Russell Hoban—the very same, very strange Russell Hoban who wrote the Frances books, about a bratty but endearing young badger, which you, like I, might have often read in childhood. Turtle Diary, which is not for kids, is a slim 1970s novel about two lonely middle-aged people who become preoccupied by the idea of freeing the sea turtles from the London aquarium. As you can see from the above quotation, it is also about coincidences. I stumbled upon a reference to it in this very good essay by Kevin Brockmeier, who calls it the best book he read in ten years. I maybe wouldn’t go that far—but there was a possibly ten-year period of my life when I’d have told you Brockmeier’s 2007 novel The Brief History of the Dead was my favorite book, so maybe Turtle Diary is a grand-favorite.)

Anyway, here I was, working on this revision, happily noticing coincidences, when, at the exact middle of the manuscript—in the middle of chapter 5 of 10—I lost momentum. 5 is the chapter immediately following what might be thought of as the novel’s first real plot point, in 4: the initial dramatic situation which—despite the fact that the book is structured chronologically backward—will, I hope, invite the reader to keep reading. I won’t bore you with the details, but what happens in 4 is painful, and my intention was for 5 and 6 to act as a kind of semicomedic reprieve, a chance to hang out with the central characters when they’re relatively young and bumbling, ignorant of the tragedy to come. In 7 will come the so-called third-act climax, in which the main characters’ relationship is twisted such that, I hope, all the events of the previous chapters will be cast in a slightly different light. 8 is meant to give more context for that event; the purpose of 9-10 is as a kind of elegiac denouement, the innocence and hope of childhood, etc.

But that’s all theoretical, for now. I haven’t gotten there yet because, as stated above, in the baggy middle, I lost momentum.

It feels awful, after such a promising first few weeks, to have again run out of gas in this journey. To try to hot-wire my process, I picked up The Art of Revision by Peter Ho Davies, and learned quite a lot, and was gruesomely attacked. See this passage Davies quotes, from Benjamin Percy:

When revising, the beginning writer spends hours consulting the thesaurus, replacing a period with a semicolon, cutting adjectives, adding a few descriptive sentences—while the professional writer mercilessly lops off limbs, rips out innards like party streamers, drains away gallons of blood, and then calls down the lightning to bring the body back to life.

Working on chapters 1-4 of this book, I might have dared to identify as that “professional writer” Percy refers to. I felt merciless and powerful as Doctor Frankenstein himself! Since entering the book’s second half, however, I am no better than a persnickety meddler. I’ve been working on chapters 5 and 6 with all the conviction and originality of a colorblind painter-by-numbers. I crave the “innards like party streamers,” the “gallons of blood,” the lightning! Instead I feel stuck and stupid and full of pent-up irritation. Put it on my gravestone, Hoban:

I shall die in blind ignorance and rage.

Perhaps, after an intense period of time spent with the tragedy of chapter 4, the relative froth of 5 and 6 feels like an awkward tonal shift. Perhaps 4 took too much emotional energy and I am too tired now to see 5 and 6 as clearly as I need to. Perhaps I just haven’t been sleeping well (I blame Industry, our current show. The backstabbery! The cocaine!). Perhaps I hate this book! Probably it sucks! Maybe I’m just bored.

Fortunately, Davies has something to say about boredom. Regarding the question of when a piece of writing is done, he acknowledges,

One familiar version of doneness is exhaustion, or boredom. There are writers who will describe this as the end point of revision, by which measure stories are less finished than abandoned. But boredom seems to be a rather dispiriting end point for a creative process.

Recently a writer friend of mine confessed that, after years of writing and rewriting and re-rewriting, she can hardly bear to look at her book anymore, she’s just going to call it done. I’ve been there. Getting to that point with a creative project is like falling out of love. Everything about it feels familiar and irritating. You just can’t stand the sight of it. Davies writes,

We lose faith in the shining idea that got us started when we discover its flaws.

Peter Ho Davies’ theory of revision (re-vision, he points out) consists of re-seeing one’s work: developing a new and inquisitive, essentially readerly relationship with one’s material. He writes, “Much of revision is to see our work through the eyes of the reader. This is why I wrote this. This is what it means to me. This is why I value it.” If that’s so, then “Doneness, in some fundamental sense, returns a story to its writer.” It is why one hates to write, but loves having written, as Dorothy Parker said. In this framework, doneness equals the clarity and apotheosis of those garbled curiosities that got one into this whole mess in the first place.

Thanks for reading Postcards from Mountain House. If you like it, forward it to a friend?

This weekend, I plan to abandon husband and kids for a brief self-imposed writing retreat at a mostly empty conference center in the woods, 30 minutes from where we live. I’ll be one of the only people there, will have to bring most of my own food, but it’s close enough that the aforementioned husband and children will deliver me dinner Saturday night, the angels. Other than eating with them, what will I do? How to intentionally re-channel that reanimating lightning?? Peter Ho Davies nicely describes the situation, and offers his humble perspective, but he never tells the reader how to fall back in love. How could he? The process must be as personal and specific as the lover herself.

While it’s not something I necessarily claim to know how to do as a writer, I do, sort of, know how to do it as a married person, and a person with several years-long friendships. I slow the fuck down. I try to listen better. I admit my resentments to myself and try to repair them. I search for the reflections of myself in my other, and for their reflections in me.

It occurs to me that, when our subject is people, what might otherwise be thought of as mere coincidences becomes something more sacred, evidence of our shared humanity.

Perhaps this approach will also work with a book.

In Other NewsThe Dream Away Reading Series is back! With a limited schedule and a new, quieter time slot (no competing with noisy diners / rock musicians!). We’ll be at The Dream Away Lodge in Becket, MA, on Sunday, 5/25, at 4 PM, with three lovely local writers. We’ll do only two more readings at the Lodge this season, on August 3 and October 12, so do mark your calendar, if you’re local. It is always a good time.

Happily, the Brooklyn bookstore Unnameable Books, just blocks from our old apartment, has an outpost in Turners Falls, MA, just 40 minutes from our new house. (Coincidence?) I’ll be in conversation with Serena Burdick at the Turners Falls location on June 20 at 7PM about her forthcoming novel A Promise To Arlette.

I will be teaching my fourth annual free creative writing class this summer at Belding Memorial Library in Ashfield, MA, Wednesdays 6:30 – 8:00, July 30 – August 27. This class has found some real fans, some real regulars, and it has become really special to me, too. In a season when arts funding is being cut, compromised, and retracted, left and right, I’m particularly thankful to the Ashfield Cultural Council for agreeing to fund us again.

March 17, 2025

Notes on Revision

I read, this past Wednesday night, to some students at Bennington College. During the Q&A, somebody asked this question: how is one to know when a book is “done”? It’s a question I’ve heard before, in workshops and classes, in other people’s Substacks (see below) and books on craft. Still, I am not sure how to answer it! I muddled through some kind of reply. Basically, I think, I said, I don’t know?, and, It’s specific to the project, and, You just kind of feel it?, and then rambled for a while about the very reassuring experience I happened to have with my beloved editor at Scribner.

Unfulfilling answers, all.

What I might and maybe should have done is directed that student to this useful piece by Courtney Maum.** But, to be honest, I have been feeling pretty soured, recently, on the whole capitalist-optimist orientation of publication-as-goalpost, of market-as-gauge-of-quality. Like the Ukranian TikTok witches who’ve been casting death hexes on JD Vance, I’ve been feeling that feminine urge to turn inward, away from empire, toward something more ancient and innate.

(**For a refreshingly anticapitalist take on art-making in this marketplace of a world, see Making Human by Maria Bowler.)

Of course, I want to sell this book eventually! And to do that I must make it comprehensible. Enjoyable, even! A book is made of language, and language is connection (among other things). Still, before I trust this manuscript to the market, I owe it my most open, thoughtful, ruthless, witchy scrutiny. Scrutiny of the thing on its own terms, not the terms of even my own beloved editor. Not the terms of the market.

The truth is I don’t know how other people decide their books are “done.” Which I put in quotation marks because, if you’ll allow me a moment of side-eye, a lot of ostensibly finished books—books that have been edited, bound, and published, with lots of pretty blurbs on their backs—often feel undercooked to me. I have felt finished only when, after many years of work, I’ve read and reread my manuscript countless times, and found (A) that I could think of nothing else to do with it, no area that felt accidentally underdeveloped, no end left unwittingly loose, and, (B) that it left me short of breath, with a prickly feeling all over, proud and apprehensive and somehow transformed. And even then, there’s a non-zero chance—a perhaps more like one hundred per cent chance—that, fourteen or so months after publication, I’ll be doing a reading from the damn thing, in front of an audience, and I’ll feel like, The fuck is this nonsense? How did I ever think this was done?

So the more useful question is, I think: How to work toward completion?

And the answer to that is: Revise.

Because, these past few weeks, I have been at once deep in revision, and in teaching mode (I’m halfway through a monthlong craft class for One Story; perhaps I’ll share some takeaways here when it’s done), I thought it might be useful to share a few thoughts on the revision process.

What follows is all I currently know about ushering a book into its final stages. A qualifier: if you are not a writer, you may as well skip this post, as you will very likely find what follows, just, eye-blisteringly boring. Even if you do happen to be a writer, you might find this piece completely navel-gazing and unhelpful! Everyone’s process is different and I don’t claim to hold the keys to any kingdom. I share my revision process here only because I do sort of feel like some writer, somewhere, who finds revision daunting and scary, could conceivably copy these practices and end up with a better draft of an unwieldy long-form project than she had before.

A month and a half ago I completed a first draft of my third novel. What that means to me is that I worked on and revised, in turn, each of the book’s nine sections, as one would a short story, in Scrivener; painstakingly compiled them into a Word document; and then spent a few weeks going through that document from beginning to end, editing / revising as I went.

That initial round of editing (Round 1!) was somewhat haphazard and cursory, in part because I knew I’d be doing a lot more soon enough. So while there were times when I spent a painful hour on one wretched paragraph, trying to get it to say what I wanted it to mean as honestly and precisely as possible, without vagueness, hyperbole, shorthand, or cliché, there were other times when I sort of skimmed, because I was tired or in a rush or just thought, in the back of my head, I’ll come back to this. The main goal was to smooth out the edges of the manuscript, fix obvious errors, make the thing shapely and clean.

When that draft was ready, I sent it to a few very kind friends who were willing to read it and offer feedback. I spent a couple of worried weeks waiting. During that time I did not work on the book at all. I felt nervous and awkward. I wrote approximately two paragraphs of a short story, which remains unfinished.

Then the feedback started to trickle in, in its various ways. One friend and I had a long phone conversation. One sent an email with a Word doc attached, as well as marginalia in her document. Two shared their notes with me over dinner. None of these modes of sharing feedback was better or worse than the others. Each is specific to its reader, her approach, and her current bandwidth.

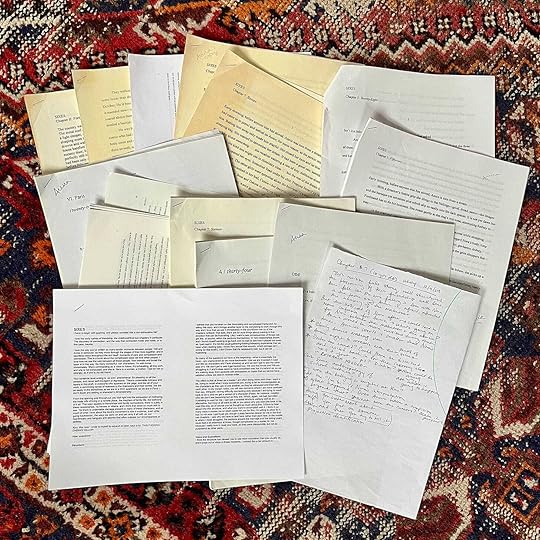

Some of the feedback I’ve accumulated over the past fourteen months.

Some of the feedback I’ve accumulated over the past fourteen months.As I digested and synthesized what these friends had to say, I began to compile this feedback—and, in some cases, my reactions to it—in several ways: I added tracked changes to a new document titled something like [novel3]_Draft2.docx. These tracked changes included the most valuable notes my friend had added in her marginalia, a few section-specific notes from her and other readers, and a few notes of my own, mostly reminders to myself to come back to certain sections in my next round.

Meanwhile I’ve continued adding to a separate, running tally of revision notes in my Notes app. These bulleted notes, organized by chapter, range in specificity from the mechanical (e.g. changing a couple characters’ ages by two or three years) to the existential (e.g. exploring more thoroughly the cumulative complexity of my main character’s grief), and their provenance is unimportant. Some are ideas from friends, others are my own. They make up a constantly evolving list, practically as old as the novel itself. Sometimes I’ll add a note to the list in the middle of the night, only to delete it the next morning because it makes no sense. Sometimes a note will hang out in the list for only a few days before being implemented in the manuscript and then deleted. Other times a note will linger in the list for months or even a year before it is deemed irrelevant and deleted. One goal of revision process is to get to the equivalent of inbox zero, which is to say to delete every note, either because it has served its purpose or because it has eventually proved unnecessary.

I think I’ve mentioned this in previous Substacks, but plenty of my notes to self originate as Voice Memos. I can’t understate the usefulness of Voice Memos as a tool for working when you’re not working. Ideas tend to visit at inopportune times (e.g. on the drive to school pick-up, during bath time, in the middle of the night), when it’s not always possible to get out the old phone or a notebook and pen and write or thumb-type them out. Periodically, when I have a moment, I sit down and transcribe every Voice Memo, keeping what feels valuable (I add those to the running tally in Notes), and discarding the rest.

Every one of the above (except for one) is a note-to-self about the novel.

Every one of the above (except for one) is a note-to-self about the novel.When I say valuable I mean an idea that feels relevant to where I want to take the book as a whole, or offers some useful framework through which to return to and transform the book into something more urgent, honest, and complex.

It is at this point that the second round of revision (Round 2!) officially begins. Round 2!, historically and currently, involves painstakingly re-importing [novel3]_Draft2.docx from Word into Scrivener, section by section, paragraph by paragraph, or even sentence by sentence, while consulting my constantly evolving list of notes and addressing each comment in tracked changes. At the time of writing this Substack post I am 4,511 words into this process; this draft is around 116,000 words. Put another way, I’ve reached the end of the second subsection in a novel which is currently 49 subsections long. If my math is right (it probably isn’t!) I’m approximately 4% of my way through the book. Yesterday morning I spent nearly two hours on one godforsaken paragraph, and I’m still pretty sure it is crap. So, you know. I don’t use the word “painstaking” lightly.

All to say. It is slow. Sometimes it is terrible. But, stop! you ask. What is it!? What do these painstaking changes to the manuscript actually consist of?? Let me step back, here, and try to name just a few approaches to revision that one might use, in Round 2!.

First: another qualifier. Approaches to revision are infinite. Mine is certainly not the only Substack tackling the topic (Danielle Lazarin has some very good stuff to say about revision in Talk Soon), and probably some of what follows is stuff you’re already thinking about. That said, here are a few, specific ideas, arranged from micro to macro:

Delete. For instance,

Murder cliché. Not just every dark and stormy night, every eye that lights up or glazes over or is as black as night or blue as tritest summer’s day (though, obviously, destroy those, too). Every yawn of a description can be understood as placeholder for something more alive. Reread to expose that past version of the self who was, to some degree, half-assing it, phoning it in, writing in language that came not fresh from her own brilliant brain but from ad copy for moisturizer or a bad novel she read years ago in the library of library her grandma’s assisted living facility. Let our prose not be colonized by cliché! Let it be fresh, alive, and free!

Destroy useless dialogue. Every instance of “yeah,” “uh,” “like,” “um” is wasted real estate; every time one character agrees with another, adding nothing to the conversation; every “maid-and-butler” moment, when the characters are being used by the writer to sum up plot or rehash backstory, rather than being allowed to speak for themselves. Every line of dialogue can be its own one-line play. Less is more—unless more is more, and if more is more, overwrite with abundance! BUT—

Annihilate redundancies. When we read for meaning, rather than to be intoxicated by our own poetic prose, we often find a ton of repetition. Two sentences may live three paragraphs away from one another—or maybe they’re right next door—which, if worded differently, essentially mean the same thing. Both cannot survive.

Replace. For instance,

Whet the vague into the sharp. We write to understand what we mean, so very often the bulk of the material in a first draft is vague, groping prose which never quite grasps the deepest essence of the matter.

Interrogate exposition. This one’s a classic. First drafts are rife with long sections of exposition explaining stuff or offering backstory which is often better conveyed in scene. I am far from a “show, don’t tell” purist. Sometimes a long section of exposition is just what the novel wants, to slow things down, let the characters rest, and give the reader something to mull over. Interrogate these sections, is all I’m saying. Some of them, at least, will probably have to be replaced.

Conversely, it’s frequently necessary to add new material.

E.g. in my current revision I spent about a week on a new scene concocted to reveal something, early in the book, about my main character’s sexual ambivalence, feminine rage, and repression. I was reluctant to convey this information in exposition because (A) the novel is already exposition-heavy enough!, and (B) the narrative voice is a very close third, and these qualities are ones of which she is semi-unaware. The purpose of this new scene is to reveal to the reader what the main character cannot or is unwilling to see.

Inevitably, when one rereads, one finds certain hints, in the manuscript, at various material which does not exist. It might be implied, for instance, that one character has a grudge against another, but in the current draft the reasons for that grudge are absent. When I revise I often find objects that feel somehow charged with narrative meaning, but whose cameos feel random and unimportant. E.g. in this revision, it is mentioned that the central couple finds a blue and yellow quilt draped over a stranger’s front gate, being given away for free. Why that mattered to me when I wrote that scene, I do not know, but when I read it again, I liked the quilt; it seemed to be invested with a kind of semi-magical narrative charge. In revision, I brought the quilt back many years later; their daughter sleeps beneath it. Few readers may notice it, but for me it helps establish a certain coherence for their world through time.

Ensure that each individual scene succeeds, locally and globally. In a recent Substack, Brandon Taylor discussed at very good length the idea of a story’s “situation.” The whole piece is excellent, do read the full post, but the bit that really resonated for me was this:

There is the large Situation which governs the story itself, and then there are local situations of character and scene which more rapidly change and alter in response to character situation. We might call the larger, more stable Situation governing the story at large as fate, destiny, or even social position.

The work of a scene is to alter a situation in some way—be it the large Situation of the story or the local situation of scene and character. The scene has not come off if the situation remains unchanged.

After reading the above, I realized what my first chapter’s “situation” was—and that, in my first draft, it remained unchanged. I never want an opening chapter to exist merely in order to introduce the novel’s characters and big, overarching themes. I want each chapter, especially in this book, to be a little story in its own right, each scene to function as an alteration of both the local situation of each individual chapter and the global situation of the novel as a whole. To that end,

Take note of and refine the manuscript’s natural rhythm. I’ve referenced the intensely structured quality of my current project several times here. It is written essentially in eight chapters made up of six two-to-three-thousand-word sections, plus one chapter made up of one single section at the end. I recognize that not everyone works within constraints that specific, but I do believe that every novel has a certain overall shape it will wants to take, as well as an innate natural rhythm. A manuscript might flow best near the beginning, but fall apart in the so-called saggy middle. It might build slowly in short bursts of prose toward an ultimate, third-act climax. The goal is to observe and dissect the sections where the book reads most naturally. Detect, if you can, what shape it wants to take, and use that information to guide choices like length, density, flow, and cadence.

There are certainly more approaches one might take in a second round of revision. There are questions of order and chronology—should this foundational moment come earlier in the book? Should that climactic scene be pushed back?. There are questions of interior character complexity; characters’ exteriors (the shape, size, and evolution over time of each character’s body); and vividness of setting. I’ve found it’s often useful to do one’s rounds of revision attuned specifically to elements like these later in a manuscript’s life cycle. Which, honestly, who knows how long that could be?

Until next time,

Rachel x

January 16, 2025

A Final Countdown

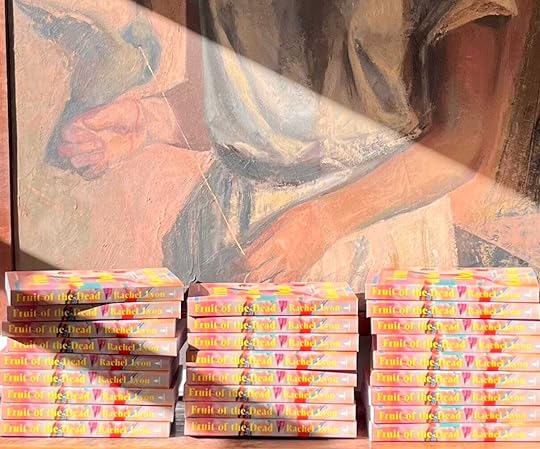

It’s a real exercise in nihilistic absurdism, promoting a book in (what feels like) an apocalypse. For the sake of efficiency, I’m going to put the bulk of what I have to say here below the following news: FRUIT OF THE DEAD: The Paperback! comes out on 2/4/25. I have a big stacks of these pretty babies in my office here. I’d love to give you one—especially if you’ve already read the book and would like to give it to someone else as a gift.

This isn’t even all of them.

This isn’t even all of them.Be one of the first 10 people to enter your address in the form below, and I will mail you one of these very copies, inscribed to the recipient of your choice. (All your info will stay private.)

I have been thinking a lot, lately, about social media. Particularly the constant dialogue therein about catastrophe. It goes without saying that social media facilitates and multiplies knee-jerk reactions, finger-pointing, lies, and bad ideas. That it also intensifies and perpetuates discourse around our worst and most relentless catastrophes plunders our mental and emotional resources, which at once numbs us to the pain of others and/or destroys our ability to compartmentalize.

Like so many, I have fretted and wept in the car and lost sleep about the inconceivable wreckage wrought by the recent and ongoing fires in Los Angeles. The violent suddenness, the magnitude of loss. The immeasurable, bewildered grief. But I have become allergic in recent months (or couple years? since perhaps the war in Gaza?) to posting about catastrophe on social media. I am confused by the social pressure that encourages us to add our voice to the echoing, discordant multitude.

What would I be posting for, I wonder? Surely not for the victims. If it can be cathartic to participate in a kind of communal outpouring of grief, the line between authentic sympathy and virtue-signaling is awfully murky. I have come to feel that my own emotional reactions, my own inexpert perspectives, are exactly as valuable to the world at large as “thoughts and prayers.” As for links to aid organizations and accurate, up-to-date information, plenty of activists and journalists are already spreading the word far better and wider than I ever could.

In a recent Substack piece, contextualizing an upcoming year-long break from social media, the novelist Edan Lepuki wrote, “The war-to-vacation photos whiplash is already challenging, and I can’t abide the notion that posting about an atrocity is a political action—or that, by not posting you are complicit in this or that atrocity.” The presumption that online silence is complicity feels not just wrong to me but possibly dangerous and probably inappropriate.

Wrong, often literally, because the majority of us are not journalists and do not/ cannot adequately fact-check our information before sharing it. Wrong, morally, because you cannot know what a person is doing behind closed doors, or on CashApp. To help someone anonymously is the highest form of tzedakah. To broadcast one’s charity publicly can seem cheap and thirsty.

It feels dangerous, long-term, because while our first amendment rights may still be protected now, in the last shallow gasps of the Biden administration—albeit on some private company’s social platform, with its dubious security, purchasable surveillance, and artificially intelligent, evolving algorithms—as a citizen, a novelist, or consumer of even the lightest dystopian content, one cannot help but wonder what kind of consequences could await the armchair social media activist who publicly opposes future administrations.

Lastly, that “silence = complicity” might apply to passivity online feels inappropriate—if not misappropriated—because, I suspect, the very idea has been decontextualized completely from its origins. It is one thing, say, to publicly shame an organization for some corruption, sign a petition, or amplify a group or individual working to effect real change. It is another to direct one’s rant into the echo chamber. Not only is it useless; not only do the platform’s algorithms evolve quicker than we do to silence those who speak out publicly against oppression; but, also, the dopamine rush of simply posting about the thing can trick us into feeling as if we took some action. To merely post is to talk the walk.

In terms of my own online dialogue around catastrophe, I have come to believe that, personally, I can offer approximately three categories of value: amplification of actual experts; love; and money. (Allow me to direct you to this recent post by the profoundly reasonable LA-based writer Pri Mattoo.) Privately, I donate; I catastrophize; sometimes I cry. Publicly my vibe is more: check out this psychedelic Play-Doh hot dog.

And, you know, after posting a picture of said hot dog in my Stories, I heard from a friend in LA who saw the photo and wrote to say that, in fact, despite or because everything is so deeply frightening right now, it kind of helped. We all play different roles, and while not all of those roles have equal value, they can all be precious, even in some fleeting, minor way.

Perhaps someday soon I will follow Lepuki’s lead and—particularly in the wake of Meta’s despicable and cowardly new policy announcement—leave Instagram for a year or even forever. Perhaps I already would have, were it not for the increased, increasing value to me of exchanges like the above. Had I not become a mommy hermit in the howling woods with two maniac children for most of her company, for whom each small hangout and correspondence, digital or otherwise, can feel almost holy. Had I no book to promote for a while.

For now, however, I have this one, small happy thing: that FRUIT OF THE DEAD has entered its final stage of the publication life cycle. The psychedelic Play-Doh hot dog of good news.

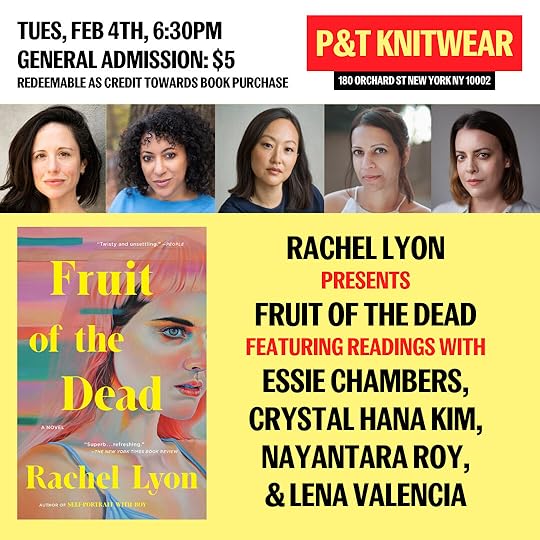

EventsIf you’re in the NYC area, please join me at a reading and launch party to celebrate the paperback release of FRUIT at P&T Knitwear on Tuesday, February 4. The lineup—Essie Chambers (SWIFT RIVER), Crystal Hana Kim (THE STONE HOME), Nayantara Roy (THE MAGNIFICENT RUINS), and Lena Valencia (MYSTERY LIGHTS)—will be terrific. Will I wear sequins? Will we go out afterward, like child-free grown-ups without a care in the world? Come find out.

If you’re NYC-based but can’t swing the above, come to Franklin Park the following Monday, 2/10, where I’ll join another excellent lineup, including Jessica Hoppe, Anelise Chen (CLAM DOWN: A METAMORPHOSIS), and Sarah Perry (SWEET NOTHINGS), at the paperback launch event for Leslie Jamison’s SPLINTERS.

If you’re Eastern Massachusetts, say hello at Porter Square Books on Tuesday, 2/11—

Classes—and if you’re in Western Mass, consider dropping in on one of the last two sessions of my creative writing class, currently meeting Wednesday evenings from 6:30-8PM at Belding Memorial Library (through 1/29). The people are lovely, the vibe is cozy, the readings are excellent, and the prompts are pretty fun, I think.

I will be teaching a new craft course on time in fiction for One Story this March. The four-week class is an expanded, virtual version of a one-day master class I taught to MFA students at the Kent University Paris School of Arts and Culture this past October. We’ll be looking at short stories by Ted Chiang, Lorrie Moore, Justin Torres, and others, and craft essays by the likes of Joan Silber and Kevin Brockmeier. I think it will be great. Sign up here.

In Other NewsA long and generous review of FRUIT OF THE DEAD appeared in this season’s issue of The Georgia Review.

Happily, FRUIT was also a Goodreads Editors Pick and named a best book of 2024 by the nice people at Oprah Magazine, British GQ, Write or Die, Lit Girl, and So Many Damn Books, among other publications.

And I just saw this week that Pravesh Bhardwaj included my story “The Fragrant Conscious World,” published in the winter 2024 issue The Bennington Review, among very good company in his 10 Outstanding Stories To Read in 2025 in Longreads. If you’re looking for something to read, there’s a lot out of wonderful stuff still out there which has been through the rigorous content moderation process that is publication.

Yours,

Rachel

Thanks for reading Postcards from Mountain House. The newsletter is free and the post is public. If you enjoy it, please share it.

October 25, 2024

Postcard from Paris

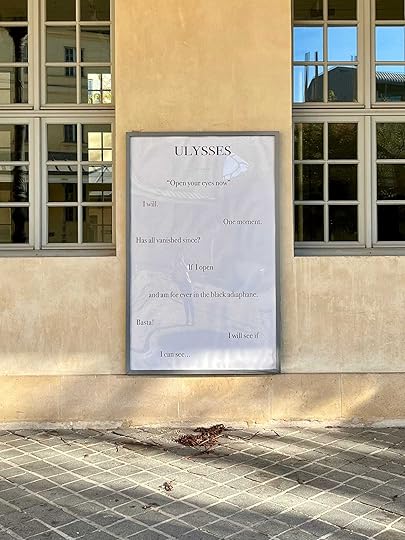

For the past month—with the exception of a long weekend in the middle, when I went home to New York for a wedding and a birthday party and to squeeze and kiss the husband and kids—I have been in Paris. Thanks to a monthlong residency through the American University I have been living at the Irish Cultural Center, a lovely old building with big beautiful casement windows looking out on a broad gravel courtyard with trees pruned in the European style and little round red tables and folding chairs. The weather was cold and wet for the first couple of weeks, which was discouraging vis-a-vis walking around Paris in sneakers, but beneficial vis-a-vis productivity. In this, my last week, however, it’s been gorgeous, blue and crisp and warm enough in the sun that I could spend a long time, for instance, writing down there in the courtyard, in a tee shirt, getting sunburnt beside this poster-sized quotation from Ulysses which hangs, framed, on one exterior wall:

Invitation to subscribe for free, if you haven’t already (or forward to a friend who might like):

Sunday I will fly home to my kids, to the spooky/gorgeous apotheosis of Halloween in New England, and the tremendous anxiety of Election Day. I have been thinking a lot—you probably have, too—about the election: our responsibilities as voters nationally and internationally; the possibility (responsibility?) of taking seriously both some major betrayal by, faithlessness in, and cynicism about our country’s leadership, in light of the unthinkable and ceaseless atrocities in Gaza and, now, Lebanon, and, simultaneously, a degree of hope and dedication to the democratic process, despite everything.

But you really don’t need to hear any of that from me, an adequately informed middle-class white American fiction writer. You’re getting it, we all are, from all sides. All I will say is that my four-year-old son’s preschool is closed on 11/5, so I’m looking forward to bringing him with me to our local polling station, and to talking with him about the democratic process in the hopeful, honest, G-rated way we talk about things together. I hope (pray?) that he will remember helping to vote in our first woman President.

For today, though—and for the sake of this newsletter, which is, you know, about writing—I am still here in Paris, missing my children but having, in a meaningful way, returned to myself, as an artist and an individual, through a lot of just exquisite time alone, and fun with old and new friends, and writing, and doing a few great events, and having, overall, a lovely time.

Yesterday at The Red Wheelbarrow, sweetest ever English language bookshop.

Yesterday at The Red Wheelbarrow, sweetest ever English language bookshop.For my own reasons, neurotic and otherwise, I’ve been measuring progress on my third book mostly quantitatively, recording the number of words that have made it from my brain to the digital page each day. And I have to say: to look at those numbers in a vacuum is to deduce that I have made objective and significant progress! One day at a time, I have written more than 26,000 words this month, triple the number of words I managed over the course of the entire summer. My manuscript is now over the 300-page mark, which is already longer than my whole second book—and it’s not done yet, but, you know, it is the length of a novel! Compiled into a Word doc, it looks like a novel! It is made up of chapters which are made up of sub-sections which are made up of paragraphs made up of sentences made up of those very 26,000 words!

I am proud of having made meaningful progress on the project, but I am also wary. Just because it is looking more like a novel and less like a jumble of disorganized paragraphs and bracketed [[tbd]]s does not mean it is necessarily closer to becoming a book. Art is of course immeasurable. Once complete, it can be evaluated only qualitatively, and prior to completion it is subject to any number of unpredictable external forces, from its author’s whims and revelations to feedback from or inspiring conversations with friends to, for instance, a month in another country, or becoming a parent. In other words I am aware that, no matter how obsessively I record my daily word count, it simply will not tell me whether the book is any good, nor what it requires to move in a goodly direction.

At home, I usually do not manage to write every day, and during periods when I do, the number of words I manage to get down is usually in the hundreds, not the thousands. 200, 500, 700, something like that. Usually, on a good week, I sit down to write twice in a week—three times, tops—and during those days when I don’t manage to write, I feel like my creative energy gets stored up and replenished, so that when I do get a chance to sit down and write, I have a lot more to say and a lot more energy with which to say it. Sometimes I mull over a scene for a week and a half before I sit down to write it—and then, I’ve already worked out some of the kinks and confusions, so it really flows. Writing every day, as I have here, has meant writing even when the spirit has not moved me. It has meant a lot of getting up from my desk and going down to the courtyard, and taking long breaks to walk or nap or read, and consuming lots of other art (see below). It has meant rereading some of the stuff I wrote a day earlier, then rereading some stuff I wrote months ago, and realizing, rather thickly, then realizing again, that more words does not necessarily mean better words.

However, if I feel somewhat stupider and uninspired, now and then, day to day, on a micro level, on a macro-level I feel more in tune with the project, more sure of its structure, its premise, its internal dynamics, its overall feel. Living in it every day has made me aware of certain patterns and undercurrents which remained unconscious, unnoticed, during the time when I was only visiting it every now and then.

Unlike my first two books, the first of which takes place over the course of one year, the second of which elapses over just one summer, this third novel unfolds over the course of forty-two years—backward. In part because, in working on it, I have been dipping in and out of different sections, which occur during different time periods, in part simply because I’m still working on the first draft, I have gotten to know my characters the way you might get to know your cousins, say, or a friend who lives too far away to see very often: in brief if sometimes telling moments, over half a lifetime.

But here is another thing that writing every day has done for me: after a month of visiting them daily, I’ve begun to feel as if these characters are not merely acquaintances. I’m not sure how to put what they do feel like; I want to say that they are me, but they are definitely not me. They are something like dear, real neighbors, walking next to me, with pasts and futures and distinctive qualities that have evolved over time and will continue to. They are also complex, embodied roles which I am increasingly compelled and able to duck into, to inhabit.

Incidentally, by now you may already have heard The New York Times’s Interview podcast with Sally Rooney. (Caroline Hagood recently had a few smart and critical things to say about it.) Whatever your take on Noted Male Interviewer David Marchese, Rooney talks about what she does as being similar to acting, say: she has this experience of inhabiting the roles of her characters, and also she feels like they are her friends. I think I feel the same way, and I sort of wonder whether it has to do with being a specifically dialogue-oriented writer, a kind of acty writer, which I’d say Rooney is, and which I probably am, too.

Rooney is among the artists I’ve read and absorbed during these weeks in Paris; it felt appropriate, as I’ve been staying at the Irish Cultural Center, among all these Irish visitors, to read her. I’ll spare you my hot (lukewarm?) take, since the literary world is already oversaturated with Sally Rooney Discourse, and just tell you this one last anecdote. Tuesday night, I was lucky enough to get to be in conversation with luminous genius / novelist / Beckett scholar Amanda Dennis. During the Q&A at the end of the talk, one of the students in the audience asked a question about Influence. Do you read when you’re writing? she said. Because I read somewhere that some writers don’t like to be Influenced by other work while they’re working on a novel. It throws them off, changes their voice, etcetera. That sort of thing.

In answering this question I felt myself becoming very animated. I said something like, well, first of all, anybody tells you he doesn’t like to read while he’s writing is probably just . . . lazy? I mean, practically speaking, if you are a writer, and you don’t read while you’re writing, when do you read? Like, it can take five or six years to finish a novel? Do you wait, that whole time, and only then, finally, when you’re done with your manuscript, pick up one book? When do you start your next project? Are you reading approximately one single book by another person every twelve years? Like, life is too short? Not to read???

But, secondly, and less flippantly, my deep belief is that reading while you are working on a long-term project is one of the great joys of life. I am like a sieve in this way: whatever I read goes right through my brain and into my work—sometimes without the benefit, even, of any real analysis—sometimes without my even noticing. For days after finishing Conversations With Friends, for instance, I kept catching myself trying to Roonify my dialogue. Eventually I will go back and edit the stuff and reel it in, bring it back to myself, closer to the heart of the project I’m working on. But, for now, I think what’s happened is, I’ve actually just learned something from her, and been practicing it on the page. And how great is that, to have found another literary role model? How gloriously weird, that bizarre, parasocial instinct, to try to speak in the same emotional dialect as another writer you love?

RecommendationsI don’t usually do this because frankly when you’re raising small kids the stuff you end up reading and watching is (A) not nearly sufficient to warrant any kind of list and (B) often mindless junk and/or meant for children, BUT since I have been here for the month I’ve had the bandwidth to sit with and absorb a bunch of stuff, which I shall now share with you:

Speaking of reading while writing, on this episode of the Ezra Klein Show (that link is just an excerpt you can read) genius Zadie Smith talks a lot about her book The Fraud and how iPhone / social media technology is not morally neutral and books she’s read and the history of the novel in light of this kind of ecstatic history-flattening thing that seems to be happening with contemporary music. It’s completely fascinating. You could listen to it twelve times and still get something new out of everything she has to say.

Relatedly, in George Saunders’s very cute Substack community, somebody then quoted that Smith interview to Saunders and asked very ingenuously whether it was a good idea, as a writer, to take a suggestion Smith made in that Klein interview, in a rather off-the-cuff way, to study the novel as a form from the 1300s until today. The post is called “How Much Do We Have To Read To Have A Chance To Be Good?” and people have offered a bunch of recommendations in the comments for a syllabus of quote-unquote Great Books from 1300-the present you ought to get through if you want, as Smith suggests, to study the novel as an evolving form over time. My only quibble is, like, okay, but half those people suggest that Lincoln in the Bardo is the defining book of the 21st century, which, I love Saunders, but. No.

My second full day here, I went alone to a 2PM screening of The Outrun, which is so good, transcendent and raw—based on a memoir by Amy Liptrot about a young scientist (played in the film by Saoirse Ronan) in the early stages of recovery from alcoholism, and the violent beauty of the archipelago to which she exiles herself, the violently gorgeous Orkney Islands off the coast of Scotland. It was me and approximately eight French retirees. I tried not to cry too noisily.

I also watched this clever, claustrophobic, and in the end very moving film called His Three Daughters. I watched it initially because two of its three stars are actors I love, Elizabeth Olsen and Natasha Lyonne, but I ended up really invested and absorbed and kind of transported. Also: good dialogue.

As research I’ve been going to hear a bunch of live music. A friend introduced me to the drummer Tiss and his project Poor Boys: incredible. (Tiss’s father-in-law, who was sitting next to us, leaned over and informed us that Tiss is the greatest drummer of his generation. I am on board.)

I’ve gone to to a few manouche jazz shows: I saw Angelo DeBarre perform with Mathias Levy on violin; then I saw Mathias again with the stunning singer Norig. Tomorrow I’m going to see Mathias play with Pablo Murgier. Conveniently I fly home on Sunday so if Mathias takes out a restraining order on me I will already be far away enough to abide by it.

In addition to the aforementioned Rooney, I’ve read and can enthusiastically recommend Amanda Dennis’s brilliant novel-of-ideas Her Here, it’s wonderful, just as luminous and smart as she is.

Krystelle Bamford’s forthcoming debut Idle Grounds is a book I shall be blurbing shortly—and hopefully saying something more eloquent than, Oh my god, I’m obsessed with this book, it’s incredible, because I am, and it is.

On a quick lil trip to Belgium I read and appreciated David Szalay’s intelligent novella Turbulence as well as Kaveh Akbar’s stirring—I want to say revivifying?—poetry collection, Calling a Wolf a Wolf. It left me very hungry for Martyr!, which I plan to pick up in advance of the plane ride home.

I spent about five hours one day at this like, unbearably huge museum, you may have heard of it, The Louvre? It was cool. I’ll leave you with my favorite of all the objects I saw there, this worried-looking 16th century Florentine guy riding a snail. Please enjoy: Gnôme à l’escargot:

À bientôt,

Rachel

p.s. My One Story class is filling up but there may still be a couple spots left. Join us, if you are so inclined! It will be fun and warm and productive and just great overall, I think.

September 3, 2024

[x] Steps Forward, [y] Steps Back

1.

Long, long ago, a lifetime ago, last March, shortly after FRUIT OF THE DEAD came out, when I was still feeling those post-pub feels—alternately low and exposed and hopeless and weird, and buzzy and high and on top of the world—I told my agent in a fit of manic productivity that, at the rate I was going, she could expect a complete draft of my third novel in her inbox by January ‘25.

LOL.

Back then, in early spring, I did have relatively non-delusional reason to believe I could achieve such a thing. I was trotting away into the new book at a pretty good clip. I felt good about the project: its parameters, its pace, and, generally, the quality of the first-draft prose I was producing.

Now, having lived in and with the work for several months, I am unashamed to admit that, from where I sit today, that claim seems wildly overconfident. I am more familiar with the book now. I have uncovered its weak spots, its eccentricities and over-complications. I understand, more clearly every day I work on it, that the foundation I am currently laying is weaker than I’d hoped it would be, that this sprawling construction will likely require a complete gut-reno before my realtor (/agent) walks through any prospective buyer (/editor).

The thing is, though, I don’t think it was mere confidence that inspired me to make that claim to my agent, four or five months ago. I think it was a combination of things: anxiety about what comes next; some wild, ambitious idea that I could, conceivably, sell my third book before the paperback edition of my second came out (more on that below); most importantly, the kind of grandiose commitment that, I think, any first draft of any project requires.

I mean, in my experience, if you don’t believe—manically and completely—in your first draft before you’ve even really begun, it won’t turn into anything. Like the fairies in Neverland, books which are not believed in either die or never live at all.

From which follows this: that, possibly, a writer’s confidence in the viability of her first draft diminishes in direct proportion to that draft’s progress, so that it is paradoxically when that initial draft has reached a point of initial completion that its writer’s confidence in the ultimate book-to-be is, infuriatingly, at an all-time low.

You can now preorder this gorgeous paperback edition of FRUIT OF THE DEAD and get it on publication day, 2/4/25.

You can now preorder this gorgeous paperback edition of FRUIT OF THE DEAD and get it on publication day, 2/4/25.2.

I have an accountability thread going with two other creative people (a poet, a writer/filmmaker) in which, now and then, we update one another with our daily word counts and other measures of progress. There have been times over the years (!) during which we’ve kept up this practice when said thread has raged with activity. Currently, we are in a period during which it is updated very infrequently. One of us recently had a baby. I can’t imagine he’s been doing a whole heck of a lot besides tending to his son. The second of us has started a new, unrelated career in writing code for software.

Me, I blame summer “vacation,” a period during which I have been able to write very little/have been able to produce just a couple hundred words at a time, when I’ve written at all. I could have shared those measly word counts with my accountability friends, but I guess I felt a little shy about them . . . maybe I was also affected by the inertia of their silence. At any rate, instead of sharing my word counts with them, I’ve been keeping track of these small numbers on a baby animals calendar I got from my in-laws for Christmas, which hangs on the inside of my office door.

Now that summer is finally over (!!), and the children are back at last in the daytime care of seasoned professionals, and I’m back at my desk, writing to you, I’d like to share with you what those word counts have been:

June (happy duckling in a field): over 7 days, produced 7,027 words

July (baby lemur, smiling strangely): 8 days (+ one insomniac night) of work; 8,306 words

August (baby bear, alert on hind feet, hay in his fur): 6 partial days of work; 3,322 words

For context, during a regular week, during the school year, in a perfect world in which mornings were never eaten up by laundry or the dentist or looking for misplaced documents or lesson-planning or catching up on the sleep stolen from me in the night by my four-year-old (the worst, the absolute worst), I am theoretically free to write for at least part of each school day, four days per week. At the end of this past May, for instance, I was averaging about 800 words per day. At this rate, I would be able to produce around 12,800 words per month. Mathematically, then, three months of summertime—during which we paid for approximately 100 hours of childcare—cut my productivity roughly in half.

Truthfully, though, of course we don’t live in a perfect world, and I wasn’t cranking out 12,800 words per month all year long. I’m not a machine. I’m not even just a writer. I’m a caretaker and a friend and a partner and a laundress and a cleaning person and a cook, and a body that requires maintenance and a brain that requires stimulation and a spirit that requires community. So, actually, though 6-8 days per month neither feels like nor is enough writing time for me, I’m going to go ahead and pat myself on the back for getting literally anything done this summer. I’ll invite you to do the same.

3.

For whatever reason, I’ve ended up in a total of three adorable creativity trios, the aforementioned accountability thread included. The second of these is a group text / sporadic Zoom hang I have going with the authors Danielle Lazarin and Jessie Chaffee, both native New Yorkers like myself (they are still in the city), currently raising small humans while working on book-length projects.

It was in our group text that Danielle recently updated Jessie and me with her progress returning to a manuscript she had not touched since completing a first draft, months ago. During our most recent Zoom we had cheered her on, reassuring her that the novel would still feel alive to her when she returned to it.

“Wanted to report back,” she wrote, a few days later, “that I have started to dip my toes back in the novel again, and you were both right to suggest I should just get back in there, trust myself that I’d find my footing. I have as much as I can at this point.” After our exclamations of delight and cheerleading, she added, “Was quickly reminded how SLOW writing is, but also yes, I do know these people / this world. Bird by bird, baby.”

By the way, Danielle actually wrote about this exchange in her own Substack last week! Her newsletter is wonderful. You should totally sign up.

But, also: isn’t it incredible how all of us, even these writers who’ve been working and publishing for many years now, have to relearn this, over and over? Big news, folks: writing is SLOW. Slower, even, I suspect, the more material you have.

4.

For instance, I recently completed an almost 18,000-word draft of my novel’s fifth chapter. Anyway, no sooner had I sent the final section of this chapter to the other members of my third creativity trio—a little writing group I have formed with two other woman writers, up here in Western Mass—than I found myself lost again in Chapter 1, reading and rereading paragraphs I know I’m going to cut; fretting to myself about how much revision I am going to have to do, now that I know so much more about the characters; and about how much is going to have to be established in those initial pages; and that, for instance, if the highly anticipated houseguest, whose arrival functions as a kind of fulcrum of that first chapter, is going to be coming not just for any old November weekend but for Thanksgiving, as I’ve recently decided, shortly followed by the novel’s near-entire cast of characters, my protagonist is going to have to be doing a heck of a lot more preparation. I mean, sheesh, this woman has not just a house to clean but yams to candy, pies to bake, a turkey to brine—and I, a middling cook on a good day, have copious research to do.

Herein is the necessary paradox of “progress.” As I attempted to reassure myself, having faced the music re: the copious revision that awaits me, a certain phrase kept kicking around in my head—you know it—an old chestnut: “two steps forward, one step back.” But that phrase itself, though somewhat reassuring, strikes me as a fallacy. Writing a novel is not linear. Indeed it feels worth noting, here, that while I did just write a doozy of a Chapter 5, chapters 4 and 6 remain unwritten.

I imagine the writing of the novel as more of a sculptural or constructive process, like building some giant, traversable object in three dimensions. You sketch out a draft of this area, then go over it, revising as you do, in more permanent material. You tug over here only to feel some depletion over there. You cut from this spot and paste on that. You fasten unrelated bits together, or dig a tunnel from one area to another, or compress a whole meandering field of bits and pieces into one hard, glittering thing. It is only [x] steps in some direction, [y] steps in another, if by “steps” we mean gestures of all kinds, if by “in some direction” we mean in and out and up and down and around and through and on and on.

In Other NewsGot a few fun things coming up:

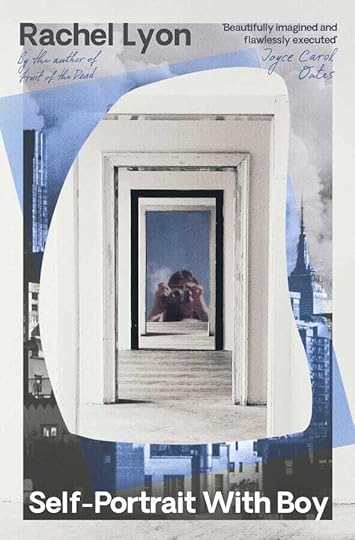

The new UK paperback edition of my first book SELF-PORTRAIT WITH BOY will come out with Scribner UK on September 12! Preorder it now and receive it on pub day.

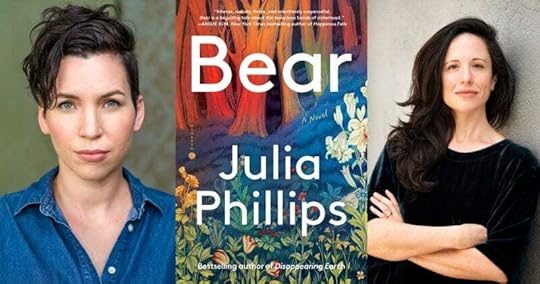

I’ll be at the Mississippi Book Festival 9/14, on a panel called Reimagining Classics. It’s from 10:45-11:45 AM in State Capitol Room 113 and I’m just thrilled by the writers I’ll be in conversation with: Katy Simpson Smith, Jen Fawkes, Julia Phillips, and Katya Apekina.

Submissions to the Pigeon Pages 2024 Flash Contest will close on 9/15. Send in your tiny stories! I want to read them!

This month’s Dream Away Reading Series will be at 6PM on 9/21 at The Dream Away Lodge. We’ll host bestselling debut novelist Essie Chambers, novelist and Straw Dog Writers Guild founder Ellen Meeropol, and novelist/songwriter Nerissa Nields.

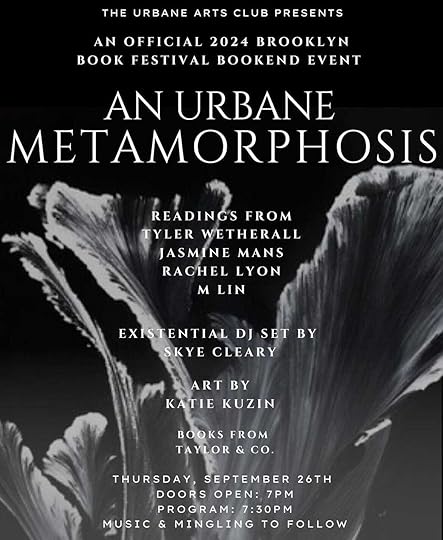

I’ll be at the Brooklyn Book Festival via The Urbane Arts Club on 9/26, at an event that promises to be a real party (you can RSVP here):

That’s all for now, I think. Thank you for reading,

Rachel x

July 24, 2024

In the Pocket(s)

Recently I received a kind note from someone who has been reading my work for a while. She had written to share a picture of my book at Dussmann, a big bookstore in Berlin (below! I love!), and to let me know she’d been reading this newsletter.

Get your own UK edition of

Fruit

right here :)

Get your own UK edition of

Fruit

right here :)This reader mentioned that her kids are the same ages as mine, and thanked me for discussing, here, the difficulties of writing while parenting. I am grateful to her for her note, not just because it is always a joy to hear from people through my work (!!), but also because it’s a relief to know that this topic—which I, at least, need to talk about, often and desperately!—resonates with her.

I am lucky to have grown up with an artist mother who paved the way for me to take my creative work seriously, and who has told me frankly how, as a working artist with young children, forty and thirty years ago, she was dismissed and discouraged. Other artists, even and especially women who’d chosen not to have kids, freely offered her unsolicited feedback to the effect of, No one can be both a good mother and a great artist. Of, You’ll quit soon, you’ll see. I think of her, and I think: This topic is my inheritance.

She’s still working, by the way.

Postcards from Mountain House is free. Subscribe to receive new posts, infrequently:

When I was three years old, my parents left me with my grandparents to spend a month in Italy, where my dad had been granted a residency as part of his graduate studies at NYU’s Institute of Fine Arts. My parents didn’t have or come from money. They were each the first in their families to undertake any postgraduate education, let alone college. In fact, of my four grandparents, only my maternal grandmother finished high school.

I imagine it must have felt very bold, almost reckless, for them to take advantage of this opportunity, thirty-eight years ago. To leave their young daughter for a month, to pursue travel and knowledge and their work in the arts, for no material reason. For no reason at all, except to learn, and to experience the world. To enrich their own lives, in other words—and, by extension, mine.

We were lucky enough to return to Italy as a family ten or fifteen years later, in the roaring ‘90s when I was a teen. I remember my dad geeking out about every melodramatic old sculpture, every godforsaken cathedral. I remember the pizza, the pasta, gorgeous Amalfi and its lumpen lemons. I also remember Laocoön. I didn’t care very much, then, about my dad’s beloved Renaissance sculptures, but I learned about them despite myself. Many years later, one of them would make its way onto the dust jacket of my second book.

Of that first trip they took to Italy, without me, however, I recall almost nothing. I was only three. I have only a sense memory of walking to the beach with my Nana, the vague mental image, many times reconstructed, of my parents returning, my mom kneeling beside me on the grass to give me the porcelain doll she brought home for me: pale-faced in a green velvet dress and lace-edged bonnet, with vinyl-lashed eyes that closed when you tilted her.

My children are recently four and almost two, a year older and a year younger than I was then. This October, I will spend a month at a residency in Paris. I am so very honored, so very excited, and, also, to think of being away from my kids for that long is already breaking my heart. It might break my husband! But, while my son (a Cancer) is certainly having big feelings, and my daughter (a Leo) will wail loudly, whimper pitifully, and demand my return, I know my absence won’t break my kids. I know it because they have another loving, responsible parent who will be here with them—and because my parents’ absence didn’t break me.

I suspect too that not only will this residency afford me the greatest gift any writer can ask for—the gift of time—but also that missing my children will end up being useful for the project I’m working on. This book—my third novel, the story of a friendship between two women, told in backward chronological order over the course of 42 years—is about friendship and family, aging and loss, and the ways that close relationships can drift in and out of one’s life, over decades. Being away from the two little people (and one big person) I love most in this world will, I think, help me evoke, to some degree, the specific and personal ways my main character misses her best friend.

In the mean time, I’ve been working on the book in the pockets of time that are available to me. Thanks in part to my husband, in part to my children’s preschools, in part to the tiny writing group I have with two writer friends, I’ve gotten a chapter done here, a section there, during the limited hours when my kids are out of the house or asleep. I’ve recorded Voice Memos to myself while I’m driving. I’ve encouraged the husband to get invested in TV shows I won’t be tempted to watch with him. Last night, after I woke from an anxiety dream and was unable to fall back asleep, I drafted about 900 words in the insomniac hours between midnight and 2 AM.

In these ways, in these pockets of time, I’ve written a little over half of a first draft—just over 50,000 words, last I looked.

I like this phrase, in the pocket. Not its political or financial meaning, but its musical one. In music jargon, in the pocket refers to being on the beat—in the beat, really. A drummer, a bassist, a band that’s really in sync, is playing in the pocket. If you’re in the pocket, you’re not making music so much as the music is making you. You are an instrument in the most literal way, a portal, a channel for the tune. It is the best feeling, no matter what medium you’re working in: that feeling that the work you’re supposedly making is this larger-than-life, thrumming entity, bringing itself to life by means of you.

In Other NewsI’ll be at Powerhouse Arena in Brooklyn, NY, on 8/6, in conversation with Lena Valencia at the launch of her imminent and delightful short story collection Mystery Lights. . .

. . . and at Odyssey Books on 8/12, I’ll be in conversation with Juliet Grames about her highly entertaining 1960s-era Italian literary mystery, The Lost Boy of Santa Chiona.

I am teaching a free drop-in creative writing class at Belding Memorial Library in Ashfield, MA, on Wednesdays from 6:30-8, through 8/21. It has been lovely. Join us, if you’re in the area.

Very excited to share that the August edition of The Dream Away Reading Series, from 6:30-7:30 PM at Becket, MA’s legendary Dream Away Lodge, will feature poet Sarah Eddy, debut novelist Sarah Seltzer (The Singer Sisters), and international literary hero Ocean Vuong.

May 30, 2024

Events, events, events!

Winter’s last frost has passed and spring has settled onto our mountain for good. Everything is lush, here, everything blooming. The grass I seeded last month has sprouted, blue-green and fine as hair. The little cottage garden at the front of our house is teeming with flowers whose names I’ve never learned. Little yellow bobbles that nod in the wind, and delicate blue stars, and freakishly tall tulips so darkly purple they are almost black. Our seasonal depression has fallen away into a crazed chattering of hopes and plans. We try desperately to hold our delight in one hand, our terror, anxiety, and grief in the other. Spring is mania. I sign at least one petition a day, often two or three. Do you?