Sue Wilkes's Blog

November 9, 2025

A Visit To Thiepval

Thiepval Memorial. Over ten years ago, we paid a visit to Loos Memorial so that I could pay my respects to my great-uncles Harry and Herbert Dickman, who died in 1916. This year, I was lucky enough to visit Thiepval Memorial, where one of my 'cousins', John William Dickman, is commemorated, and to pay my respects.

Thiepval Memorial. Over ten years ago, we paid a visit to Loos Memorial so that I could pay my respects to my great-uncles Harry and Herbert Dickman, who died in 1916. This year, I was lucky enough to visit Thiepval Memorial, where one of my 'cousins', John William Dickman, is commemorated, and to pay my respects.

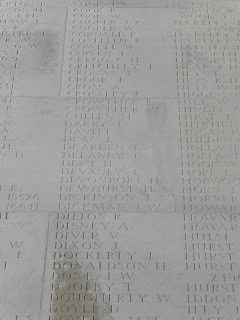

J W Dickman, Thiepval.

J W Dickman, Thiepval. John was the son of John and Mary Dickman, of 38, Kay St., Lower Openshaw, Manchester, and he served in the 8th Battalion of the East Lancashire Regiment. He was only 24 years old when he died on 15 July 1916 - just two weeks before my great-uncle Harry was killed. (Herbert died earlier that year).

What a terrible year that was for my family.

Photos copyright Sue and Nigel Wilkes.

'Scarlet Sin'

My latest feature for Jane Austen's Regency World magazine (Nov/Dec issue) is on the ancient craft of dyeing.

In 1814, Jane Austen wrote to Cassandra to complain about the local dyer: ‘My poor old muslin has never been dyed yet. It has been promised to be done several times. What wicked people dyers are! They begin with dipping their own souls in scarlet sin’.

Dyes were used for many different fabrics: wool, worsted, linen, cotton, and silk.

The secret of Turkey-Red dyeing (from the Far East), was much sought after in Britain, but it was not until the 1780s that it was successfully accomplished in Britain, in Manchester and the Glasgow area.

The late eighteenth century also saw the introduction of new dyes from metals, like 'iron buff' and orange from antimony.

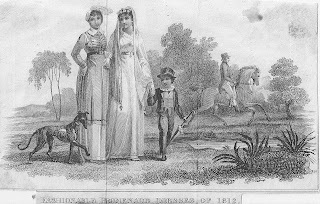

Image from the author's collection: Costume Parisien, Journal des Dames et des Modes, 1803. A ‘Robe de Mousseline Turque’ [Turkey muslin].

July 18, 2025

8 College Street, Winchester.

No 8, College Street, Winchester.

No 8, College Street, Winchester. A few weeks ago, I was very privileged to see inside No 8, College Street, Winchester, the house where Jane Austen spent her last few weeks.

Her family hoped that a town doctor, Dr Lydford, might be able to effect a cure for her illness (the cause of which is still not known for certain).

Jane wrote to her nephew James Edward Austen, 'Our lodgings are very comfortable. We have a neat little drawing room with a bow window overlooking Dr Gabell’s Garden'.

The bow-window at 8 College Street. The left image is the current view through the bow window on the first floor; on the right is the view of the same room from the far end.

The bow-window at 8 College Street. The left image is the current view through the bow window on the first floor; on the right is the view of the same room from the far end. Below you can see how the room looks at the far end; there's a fireplace at both ends of the room.

Jane was still writing almost until the end; her last composition was a comic verse on Winchester horse races.

She died on 18 July 1817.

I was very moved to finally see inside the house; I have often seen it from the outside over the years. Of course, I was more sad than excited. How young Jane was! She was still only 41 years old.

After Jane's death, her sister Cassandra wrote mournfully to their niece Fanny Knight: 'I have lost a treasure, such a sister, such a friend as never can have been surpassed. She was the sun of my life, the gilder of every pleasure, the soother of every sorrow; I had not a thought concealed from her, and it is as if I had lost a part of myself'.

Winchester College has renovated the interior, and carefully matched the paint on the walls to traces found during the restoration. The house is currently open to visitors until the end of August (although you may have to wait for a cancellation).

July 1, 2025

'Your Irish' Linen

My latest feature for Jane Austen's Regency World (July/August issue) is on linen manufacture.

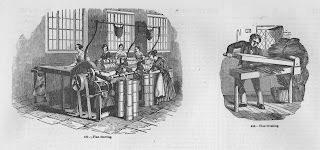

Flax-drawing and flax-breaking.

Flax-drawing and flax-breaking. In a letter to Cassandra, (16 September 1813), Jane Austen wrote, ‘Fanny bought her Irish [linen] at Newton’s in Leicester Square, and I took the opportunity of thinking about your Irish, and seeing one piece of the yard wide at 4s…it seemed to me very good’.

Linen was made from flax; it required a great deal of processing - 'dressing' - to turn the plant's woody stems into yarn for weaving. In the late 1780s, the first flax-spinning factories appeared in Britain. Scotland and Yorkshire were important linen manufacturing areas.

An enormous flax mill was also opened near Shrewsbury. Ditherington Flax Mill (1796) was the first ever fireproof mill in the world.

Ditherington Flax Mill

Ditherington Flax MillLinen was used for items like ladies’ shifts, nightwear, underwear, and dressing-gowns, and of course, table and bed 'linen'.

Images:

Top: Flax-drawing in a factory (left) and flax-breaking (right). Charles Knight, Knight’s Pictorial Gallery of Arts, Vol. 1, London Printing and Publishing Co., c.1858. Author’s collection.

The Spinning Mill at Shrewsbury Flax Mill Maltings, built c.1796. Formerly Ditherington Flax Mill, it was converted to a maltings in the late nineteenth century. © Sue Wilkes.

May 6, 2025

The Power of the Press

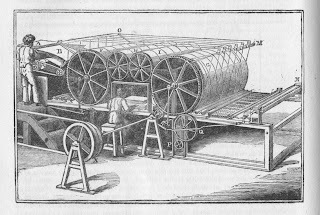

My latest feature for Jane Austen's Regency World (May/June issue) is on the advent of printing newspapers and books by steam-power, instead of a printing press worked by hand. On 29 November 1814, the first ever copy of The Times newspaper entirely printed by machine appeared.

The new printing-press, invented by Frederick Koenig, required just two child workers to tend the machine and feed it with paper, instead of two highly trained printers.

By the late 1820s, an improved version of Koenig's press, designed by Edmund Cowper and Augustus Applegarth, could print 5,000 newspaper pages every hour.

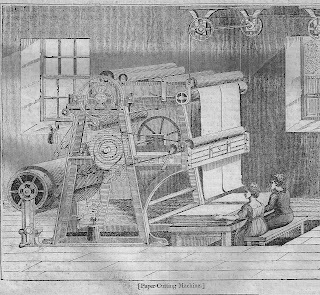

Image: An Applegarth and Cowper printing machine, with child workers. This machine was used for printing books. Luke Hebert, The Engineer’s and Mechanic’s Encyclopedia, Vol. II, Thomas Kelly, London, 1836, Nigel Wilkes Collection.

March 5, 2025

'Hot-Pressed Paper'

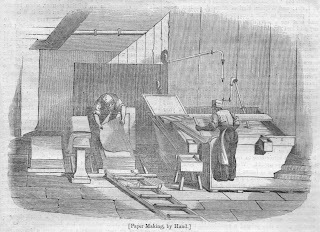

My latest feature for Jane Austen's Regency World (March issue) is on the art of paper-making. Paper was needed, of course, for Jane's letters, and for her books to be printed on.

My latest feature for Jane Austen's Regency World (March issue) is on the art of paper-making. Paper was needed, of course, for Jane's letters, and for her books to be printed on. Paper was commonly made from cotton or linen rags. Some of the process was already mechanized and powered by water - there were already paper-mills in the mid-eighteenth century - but it was a slow process. It could take up to three months to make one sheet of paper by hand, depending on its quality.

'Hot-pressing', as mentioned in Jane's novels, involved heating a sheet of writing-paper between cast-iron plates to give a nice smooth finish.

Louis-Nicholas Robert's 'continuous wire process' (1798) made it possible to make much larger sheets of paper by machine. Within a few years, the first paper made in a single continuous roll was made at Frogmore Mill in Hemel Hempstead.

The paper was also cut by machinery, tended by child workers.

And the more paper was made, the more novels could be printed!

Images from the author's collection:

Top left: Paper making by hand at Hollingworth's Turkey Mill, Maidston, Penny Magazine, 1833.

Centre: Paper-cutting machine with child workers, Monthly Supplement of the Penny Magazine [96], 31 August to 30 September, Charles Knight, London, 1833.

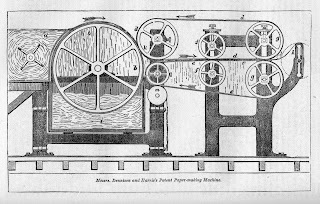

Image right: Dennison (Denison) and Harris’s Patent Paper-Making Machine, patented 1 January 1825. Luke Hebert, The Engineer’s and Mechanic’s Encyclopedia, Vol. II, Thomas Kelly, London, 1836, Nigel Wilkes Collection.

January 27, 2025

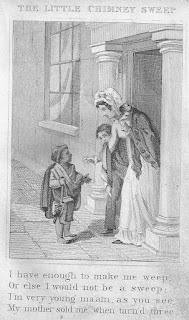

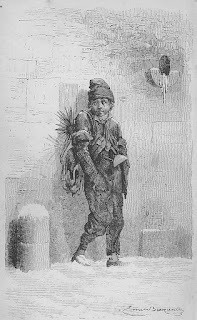

The Last Child Chimney Sweep To Die At Work

A blue plaque is planned for George Brewster, a climbing boy (child chimney sweep) who died on 12 March 1875 after swallowing a large amount of soot while sweeping the flues at Fulbourn Lunatic Asylum, Cambridge.

His master, William Wyer, was found guilty of manslaughter and sentenced to six months in jail with hard labour.

George's death was just one of many which shamed the British nation.

Politicians and philanthropists of various hues like Jonas Hanway had been attempting to ban the use of child chimney sweeps since the late eighteenth century.

Impoverished parents actually sold their children to chimney sweeps to use as apprentices (their small size meant they could climb up inside chimneys to clean them of soot).

But George's horrific death finally sparked the impetus for change, and it's thought that he was the last child to die while sweeping chimneys.

Lord Shaftesbury (the 7th Earl), after several unsuccessful previous attempts, finally piloted the Chimney Sweepers' Act, 1875, through parliament. The Act required chimney sweeps in England and Wales to be licensed annually, and gave the police powers to enforce the law.

Lord Shaftesbury (the 7th Earl), after several unsuccessful previous attempts, finally piloted the Chimney Sweepers' Act, 1875, through parliament. The Act required chimney sweeps in England and Wales to be licensed annually, and gave the police powers to enforce the law. You can read more about the story of the child chimney sweeps in my new release Young Workers Of The Industrial Age, which is still on special offer on the Pen and Sword website.

December 31, 2024

Charles Lamb, plus Early Locomotives

Happy New Year, everyone! I hope you all had a peaceful Christmas and New Year.

Happy New Year, everyone! I hope you all had a peaceful Christmas and New Year. The January/February 2025 issue of Jane Austen's Regency World has two features by me, on two very different subjects.

The first feature is on the tragic life and career of the author Charles Lamb.

The first feature is on the tragic life and career of the author Charles Lamb.

Charles Lamb was well known for his comic essays; but his life was marked by deep personal tragedy.

Very sadly, the Lamb family suffered from mental illness, especially his sister Mary.

Charles's life was changed forever after Mary, while very distressed, fatally stabbed their mother.

Nevertheless, Lamb steadily forged a writing career, publishing plays, novels, poems, and essays (under the sobriquet Elia). He also collaborated with Mary on their Tales from Shakespeare (1807), which is still in print today.

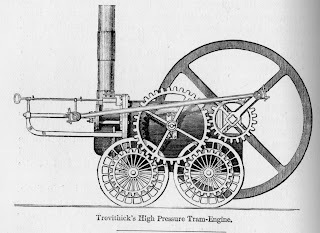

My other feature, part of my continuing series on the industrial revolution, is on the advent of railway engines, including Richard Trevithick's ground-breaking 'Catch-Me-Who-Can', and his 'tram-engine' (1804) which hauled minerals at Pen-y-Darren ironworks, South Wales.

Images from author's collection:

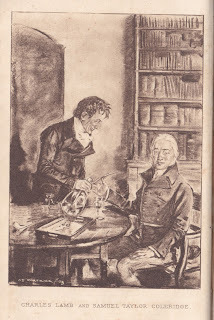

Top left: ‘Charles Lamb and Samuel Taylor Coleridge’. Illustration by Archibald Standish Hartrick (1864–1950), The Letters of Charles Lamb, Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co. Ltd, London, c.1903.

Image centre right: Interior of the Bell at Edmonton, from a sketch by J. White. A friend from the country had called upon Lamb.

Bottom. Exterior of the Bell at Edmonton, in Charles Lamb’s time. W. Carew Hazlitt, Mary and Charles Lamb: Poems, Letters and Remains, Chatto & Windus, London, 1874.

Image Left: Trevithick's High Pressure Tram-Engine, The Engineer’s and Mechanic’s Encyclopedia, Vol. II, Thomas Kelly, London, 1836.

December 21, 2024

Happy Christmas Everyone!

Happy Christmas! I hope you all have a wonderful, peaceful Christmas and New Year.

Image from the author's collection.

December 10, 2024

Child Workers in Britain's Coal Mines

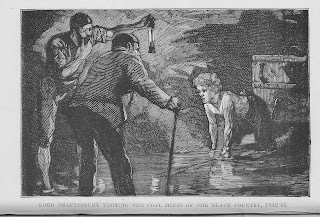

A child miner in 1842.In 1842, a Children's Employment Commission was set up to discover the true facts about child labour in Britain's coal mines.

A child miner in 1842.In 1842, a Children's Employment Commission was set up to discover the true facts about child labour in Britain's coal mines. We do not know precisely how manychildren worked underground in the middle of the nineteenth century. The commission only established the proportionof children and young people to adults, which varied according to district. For example, over one-third of the workforce was under eighteen in the Durham, Northumberland, Glamorgan andDerbyshire mines.

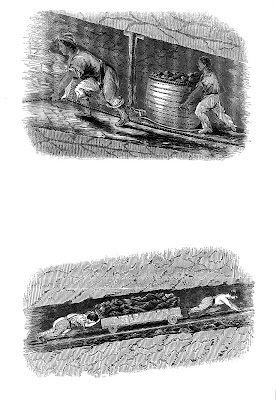

Wellcome Collection. Child workers 'hurrying'.

Wellcome Collection. Child workers 'hurrying'. The age when children first entered the pit depended on thethickness of the coal seams, family poverty, and local custom. Children asyoung as four were recorded. On averagegirls and boys began working underground when they were eight or nine yearsold.

The youngest children were 'trappers'. They opened and closed the ‘trap-doors’ which regulated air-flow through the pit. The trappers sat alone for hours in the dark,unless they had a candle. Six-year-oldSusan Reece, a trapper in a South Wales pit,said she ‘didn’t much like the work’.

Older children moved coal for the ‘getter’ or ‘hewer’ from thecoal-face to the bottom of the mine-shaft. Thin seams (only twenty inches high) could only be worked by using childrento drag or push the loads of coal, sometimes up a steep slope. This was called‘hurrying’ or ‘putting’.

Children hauled tubs of coal using agirdle or belt and chain, which they paid for out oftheir wages. The belt blistered and cut the children’s skin; theirbodies became stunted from prolonged stooping.

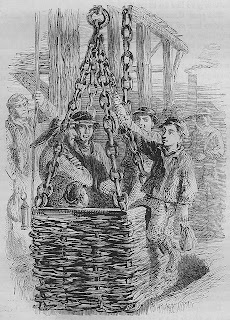

Descending into the pit, 1870s.In some pits, young boys were ‘engineers’; they controlled the engine which wound parties of workers up and down themine-shaft. They had to stop the basket or tubcarrying the people at exactly the right moment. If not, the tub and itspassengers continued up and over the overhead pulley, injuring them or dashingthem into the mine-shaft below.

Descending into the pit, 1870s.In some pits, young boys were ‘engineers’; they controlled the engine which wound parties of workers up and down themine-shaft. They had to stop the basket or tubcarrying the people at exactly the right moment. If not, the tub and itspassengers continued up and over the overhead pulley, injuring them or dashingthem into the mine-shaft below.

In east Scotland, women and girls of all ages carried coal ontheir backs to the surface via a succession of steep, rickety ladders. The loads they carried were incredibly heavy. Some fathers ruptured themselves as they lifted aload onto their daughter’s back.

Women and children also worked above ground at thepit-brow in many areas.

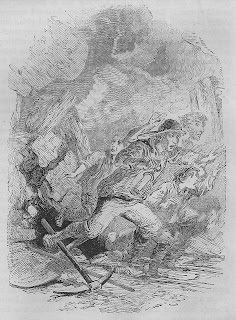

Coal mines were (and still are) very dangerous places to work in. Explosions from gases like fire-damp were commonplace; and there were thousands of run-of-the-mill accidents, like being run over by a coal waggon, or a roof collapse. In 1838, there were 349 fatalities in English collieries; over one-third of those killed were under eighteen. An explosion in a coal mine, 1870s.

An explosion in a coal mine, 1870s.The Mines Reform Act of 1842 banned allwomen and girls from the pits. The minimum age for boys enteringthe pit was lowered to ten, but they could be engine-men as young as fifteen. However, it proved difficult to enforce the Act. Boys under ten were found working below ground overten years after the Mines Reform Act.

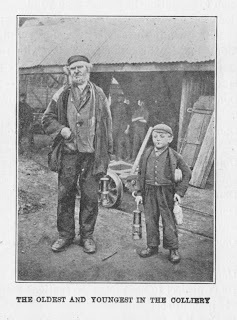

Oldest and youngest miners in a colliery, c.1906.

Oldest and youngest miners in a colliery, c.1906.