Stephanie Spence's Blog

April 7, 2025

Is Yoga Dangerous?

February 26, 2025

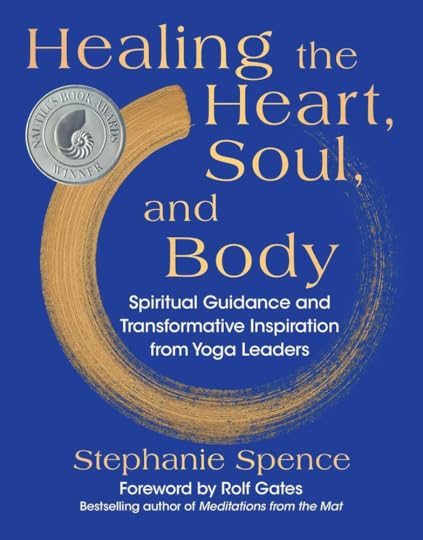

Book Release

Exciting News!

I’m thrilled to share that my book, Yoga Wisdom: Warrior Tales Inspiring You On and Off Your Mat, is being rereleased with a beautiful new cover and a fresh title:

Healing the Heart, Soul, and Body: Spiritual Guidance and Transformative Inspiration from Yoga Leaders

This book has already touched so many readers with its compelling blend of storytelling, spiritual wisdom, and heartfelt inspiration from yoga leaders around the world. Now it’s poised to reach even more seekers on their journey toward healing and wholeness.

Here’s why readers have called it transformative and why it belongs on your bookshelf:

✨ Deep, Personal Stories: Authentic accounts from yoga leaders who share how they found strength, clarity, and healing in the face of life's challenges.

✨ Guidance Beyond the Mat: Timeless lessons on healing your heart, mind, and body that resonate whether you practice yoga or not.

✨ Practical Inspiration: Uplifting, actionable wisdom that helps you live with more mindfulness, compassion, and resilience.

✨ Available for Pre-Order NOW! ✨

I can't wait for you to experience this updated edition when it officially launches at the end of April 2025. Secure your copy today and continue your journey toward healing and transformation.

Thank you for being part of this journey!

#HealingTheHeartSoulBody #PreOrderNow #YogaWisdom

December 14, 2023

Manifesting Intentions: Yoga and Crystals for Empowerment

Have you ever wondered how yoga and crystals can work together to empower you? In this article, we will take a closer look at the concept of manifesting intentions through the dynamic duo of yoga and crystals. Imagine being able to set positive goals and see them come to life – that's the power we'll be exploring here.

To start, let's understand what manifesting intentions means. It's about turning your thoughts and aspirations into reality. This article looks into how joining the ancient practice of yoga and crystals it’s believed you can create special energies. So, how do yoga and crystals connect to empowerment?

Well, that's what we're here to unravel – the special link between these practices and the strength they can offer you. We'll dive into how their combined forces can uplift not just your body but also your mind and spirit. So, get ready to explore this exciting synergy that could bring a positive change to your life.

The Power of Yoga for Empowerment

Yoga, an ancient practice spanning centuries, transcends mere physical movements. It serves as a spiritual guide, fostering a connection between the practitioners' bodies, minds, and souls. Envision yoga as a means to achieve internal equilibrium, with its fundamental principles centered on seeking life's balance, purposeful movement, and mindfulness of our breath.

Now, let's talk about how yoga is a superhero for your well-being. First off, it acts as a champion for your body, ensuring flexibility and strength. Plus, it's a brain booster and Zen producer! Yoga is so much more than physical moves; it is a proven tool to activate your parasympathetic nervous system which promotes relaxation, reduces stress, and enhances overall well-being by calming the body and mind. It also aids in concentration. Remember the spiritual aspect as well; yoga provides a pathway for individuals to explore and cultivate a deeper connection to their inner selves, fostering spiritual growth and a sense of transcendence.

Within the vast landscape of yoga, specific poses and practices have been identified for their empowering effects. Poses such as Warrior I (vīrabhadrāsana I) and Warrior II (vīrabhadrāsana II) cultivate a feeling of strength and confidence, both in your body and your mind. Practices like breathwork (prāṇāyama) teach us to harness the power of our breath, promoting clarity and focus.

Crystals and Their Energetic Properties

Crystals have been esteemed across the annals of history not merely for their aesthetic allure, but rather for a multifaceted array of intrinsic qualities and symbolic significance. Various cultures, from ancient times to today, have found special meanings in these colorful gems. It has been a part of human traditions, whether for reasons of beauty or spirituality.

Many people think crystals have a special energy that can affect how we feel. It's based on the idea of energy fields and vibrations. In simple terms, people believe crystals give off energy that connects with the energy in our bodies.

Though it might sound a bit like magic, this belief has stuck around for a long time. People think that by being near certain crystals, they can feel happier and more positive. To use crystals for empowerment, you pick ones that match your goals.

Every crystal is believed to possess its unique powers. For example, some link rose quartz with love, while others connect amethyst to clarity and spiritual growth. Bringing these crystals into your daily life can be as easy as carrying them or placing them in your space. By having crystals around, you might feel more positive and empowered in your life.

Yoga and Crystals: A Powerful Combination

Yoga and crystals team up to make something special. When we mix crystals with yoga, it's like joining the old wisdom of yoga with the good vibes from crystals. Imagine your yoga mat as a special space where the positive energy from crystals enhances the entire experience.

Crystals, like amethyst or clear quartz, are thought to have special powers that can make us feel good. When we use them in yoga, they act like friends which may make the mind and body connection even stronger.

Yoga already brings strength, clarity of thought, and a sense of something greater. Now, add in the crystal vibes, and you've got a mix for feeling powerful. The easy flow of yoga goes hand in hand with the gentle energy of crystals, making a practice that's more than just poses.

It's like fitting together parts of a puzzle – yoga and crystals harmonize seamlessly, crafting an image of strength, equilibrium, and inner well-being. So, when you unroll your yoga mat with a crystal, you're not just doing yoga – you're embarking on or continuing a journey to deepen your understanding of yourself and feel strong, grounded, present, and self-aware.

Manifesting Intentions through Yoga and Crystals

On the journey to feeling stronger through yoga and crystals, setting intentions is like a friendly guide pointing us toward what we want. Think of intentions as tiny seeds we plant in our minds during yoga. Yoga helps us think about what we want to achieve or grow in our lives. Crystals are like helpful friends in this process, making our intentions stronger with their special energies.

Engaging in specific rituals and techniques assumes paramount significance in the actualization of our intentions. It's a bit like following a recipe to make a yummy dish. We can do certain things, like holding a crystal while meditating or doing specific yoga moves that match our goals.

Keeping a positive mindset is like having a happy coach cheering for you. It's normal to face problems or feel unsure sometimes, but keeping a positive mindset helps us get through them. These simple rituals make the whole process more powerful.

Connecting actions with intentions means thinking about our choices and actions outside of yoga or when we're not meditating crystals help us. This journey becomes a loop of setting intentions, doing rituals, and making choices that create a strong and positive impact in our lives.

Practical Tips for Incorporating Yoga and Crystals into Daily Life

1. Start by setting aside a small, dedicated time each day, even if it is just 10-15 minutes. Find a quiet space where you can move and breathe comfortably.

Begin with simple yoga poses, like child's pose (bālāsana) or mountain pose (tāḍāsana), to gently wake up your body and mind. As you become more at ease, feel free to explore extra poses or sequences that connect with you.

2. Selecting the appropriate crystals for your goals or objectives is essential when it comes to crystals. For instance, you might want to consider utilizing clear quartz if you are looking for attention and clarity. If you need a boost of positive energy, citrine could be a great choice.

3. To enhance the energetic link, keep your selected crystal nearby while engaging in meditation (dhyāna) or practicing yoga (āsana). Remember consistently that there isn't a universal solution and invest ample time in choosing the crystals that resonate with your instincts.

4. Thinking about mindfulness and reflection doesn't require a lot of time. Include a few minutes each day, as part of your morning routine, in your breaks, or before bed, to assess your physiological and psychological state.

5. Simple activities like paying attention to your breath during a quick walk or dinner can demonstrate ,mindfulness. By incorporating these simple practices into your everyday routine, you will progressively cultivate a more intentional and aware life that aligns with the empowering principles of crystal healing and yoga.

Conclusion:

I want to take this opportunity to encourage you to give it a try! You are welcome to experiment and customize these techniques, but I encourage you to seek out a qualified and certified yoga teacher if you are new to yoga. As far as crystals go, you may even figure out what crystal makes you feel the greatest.

To feel empowered, design your own experience. Most importantly, make your health and well-being a priority and enjoy yourself. Cheers to your journey of empowerment through yoga and crystals!

September 27, 2023

Teaching ahimsa and karuṇā: Yoga's Blueprint for Empathy

There is no better time to create an empathetically enhanced world through the practice of yoga. The place to start is with today’s generation of children. In so doing, we must teach our children how to develop a peaceful mind. But where best can we begin?

Today’s educational model is outdated for the need to address the envisioned change. To enhance the educational model, we could teach yoga as secular ethics. Secular ethics is a branch of moral philosophy in which ethics is based solely on human faculties such as logic, empathy, reason or moral intuition, and not derived from belief in supernatural revelation or guidance which is the source of ethics in many religions (Wikipedia 2007). Additionally, we should also include emotional intelligence, altruism, mutual respect, reason: how to analyze things through investigation (making every effort with full confidence) and give explanation of our minds. Cultural heritage would need to be addressed in this new model. Specifically, each cultural heritage may need a different explanation on how to develop a peaceful mind.

Furthermore, this new model must include ahimsa (non-violence) and karuṇā (compassion) and teach future generations about a peaceful mind and mental health. While it wouldn’t be easy, one thing is certain; to achieve the level of empathy necessary to change the world, we must start with education. The time for this new model is now.

With the current escalation in violence in the United States, now is the time to teach children about the emotions that destroy our peace of mind; anger, fear, and selfishness/ego.

This paper dives further into two concepts of yoga: ahimsa and karuṇā. If we remove the broad adoption barriers such as prayer and references to common religion from yoga, the message of love/empathy (which is contained in all religious traditions) would be the catalyst necessary in achieving an empathetically enhanced world (allowing all seven billion of us on Mother Earth to live better together). We can learn to respect all life, reducing anger, fear, and selfishness.

By using hermeneutic analysis, I took my initial idea of how to teach children to develop a peaceful mind and searched through the ancient yoga text, the Bhagavad-Gita, for insights into my thesis. I gathered information in books and online from different religions, ancient yoga texts, and my personal modern yoga practice. I sorted through numerous books in my personal library, some of which were required through my university as part of my pursuit of my Master’s in Yoga Studies. I selected numerous sources, which I site, to support my thesis. I read and analyzed the text through my cis gendered, Caucasian, Buddhist, feminist post-modern self-identifying champion of the ancient science of this tool of transcendence, the yoga of my understanding.

I would like to acknowledge the ancient texts that I used were not only translated by different people, but the commentaries were also unique to the time and place of its commentators. Although the critical thinking and commentary that I present is nuanced by my over forty years of practicing yoga, it is my personal views and opinions that have helped me identify and refine my opinions. My views and opinions are also shaped by the neoliberal and capitalist western modern yoga that exists here in the United States. This has all helped me develop my ideas about issues of social justice, which is ultimately the focus of this paper, but I understand that I may have biases. I applied the filters of living in this time and in this place. This has all helped me develop my ideas about issues of social justice, freedom from suffering, and co-existing in a peaceful world which contributes to the underlying themes of this paper. It goes without saying that rectification, comments, criticism, current research or relevant data, and any useful information that someone reading this thesis may be able to contribute will be gratefully received.

What if we could help children identify certain emotions that give us a distinctive flavor of self-love? Many children today are so desensitized to violence and anger that they are developing an unconscious growing sense of division among people. Self-love could perhaps then be reconciled (through the teachings of yoga) with love for humanity, and love for the earth, a more holistic experience of love.

In addition to teaching children how to identify, and honor, all of their feelings, we need to direct them into healthier alternatives. Nourishing their emotional landscapes with a broader spectrum of emotions that shift them beyond the self, into a state of interconnectedness. Awe has been identified as an emotional state (along with inspiration, gratitude, and compassion) which transcends the self.

What if we could teach children to actively seek out and celebrate emotional experiences that move beyond a fixation with self to reinforce our connectedness to other human beings, and the wider planet? As we face far-reaching environmental and humanitarian challenges, self-transcendence will be more necessary and significant than ever before. Emotions, long seen by some as irrational or inconsequential, actually lead to tangible behaviors because they could also positively propel decisions and actions.

Self-transcendence is the final, and often forgotten, peak of Maslow’s pyramid (Courtney E. Ackerman 2021). When psychologist Abraham Maslow created what he called the hierarchy of needs, it is meant to represent the various needs and desires that make up and motivate the totality of human behavior. As we would teach children yoga, through something as simple as a system like Maslow’s (that is usually taught in traditional public schools anyway), we would teach yoga as a part of this pyramid. This, of course, would also come under the umbrella of having the most basic of human needs met, which belong in the realm of human rights. There is a genuine degree of personal authenticity and purpose for someone that is able to achieve their greatest potential through self-actualization. We all deserve this, and I believe it is our responsibility to ensure that our children and generations to come have an opportunity to learn how this is possible. Teaching the foundations of yoga to our children is the answer.

The Yoga Sutras of Patañjali (YS) constitute the foundations of yoga. This, along with teachings from the Bhagavad-Gita and others, could be secularized so that mainstream fears could be alleviated that somehow yoga is a religion. But, for the purposes of this paper, I will identify a couple of specific moral values and/or abstinences from the YS which will offer guidance both on and off the yoga mat.

Bhavani Silva Maki, yoga teacher and author, espouses a wholistic view of wellbeing.

The natural state of living in spiritual balance is called Dharma, and comes from the root dhar, meaning “to support, to hold”. Dharma is the principle that there are basic fundamental standards requisite in maintaining human life in harmony with nature. Not only do the dharmik codes support an environment conducive to our personal wellbeing, they are also our responsibility to uphold in order to support a general atmosphere of human happiness, social harmony, and the highest good for all. (Maki 2013)

Maki goes on to say that,

Dharma is not only our responsibility and duty, but also our right, and privilege. (Maki 2013)

The tenets of dharma, according to Patañjali, are the yama and niyama. The first limb of yoga, according to Patañjali, is made up of the yamas. The teachings illustrate a very important principle: if you want to change the world, you have to start with yourself. Ahimsa, often thought of as the most important yama, means ‘Non-violence’ or ‘non-harming’. (‘himsa’ = ‘hurt’ and ‘a’ = ‘not’). In this sense, we are talking about non-violence in all aspects of life. If we could teach children that when we act with ahimsa in mind, this means not physically harming others, ourselves or nature; and making sure what we do (and how we do it) is done in harmony, rather than harm. If children could leave behind (tyāghaḥ) anger and violence they would not only have a peaceful mind, but a peaceful daily experience. Sutra II:35 of the YS is ahiṁsā-pratiṣṭhāyaṁ tat-sannidhau vairatyāghaḥ ॥35॥

When in the presence of one established in nonviolence, there is the abandonment of hostility. (Chapple 2008)

And according to Hariharānanda Āraṇya, Sutra II:35 also means that

As the Yogin becomes established in non-injury, all beings coming near him cease to be hostile. (Aranya 2017)

Therefore, inwardly and outwardly, the life of yogis (and those around them) would be more peaceful.

The idea of living in harmony need not seem like some kind of “spiritual dogma” that has come from a religion that seems out of sync with the understanding or sensibilities of people that have never studied religions like Hinduism, Buddhism, and/or Jainism. Most religions of the world believe in harmony, treating others as we would treat ourselves, and love as basic tenets of right-living, so this could be taught more as a code of right conduct. This all-encompassing teaching of ahimsa brings to light that anger and even negative thoughts bring pain, to self and others.

According to Nicolai Bachman, author of The Path of the Yoga Sutras: a practical guide to the core of yoga,

When we harm others, we harm ourselves, and vice versa. (Bachman, The Path of the Yoga Sutras: a practical guide to the core of yoga 2011)

Bachman goes on to add that,

A quiet heart-mind calms, whereas an agitated one disrupts. Whenever we direct thoughts toward other people, they receive the energy of those thoughts. On the other hand, thoughts of unconditional love and support will uplift another person. Being considerate by performing acts of kindness stimulates friendship and goodwill among people. (Bachman, The Path of the Yoga Sutras: a practical guide to the core of yoga 2011, 144)

Children need to understand that,

Each person has the potential to be kind or be mean. Practicing ahimsa can strengthen our kindness and weaken our meanness. All sensory information, especially sights and sounds, will influence our heart-mind and create impressions on it. Every time we have an experience, we are colored by it. Therefore, if we want to cultivate nonviolence, we can consciously choose to reduce experiences that expose us to violence… and replace them with positive input that has the character of kindness and compassion. (Bachman, The Path of the Yoga Sutras: a practical guide to the core of yoga 2011, 145)

Growing up in an extremely abusive household I witnessed firsthand the devastating effects of violence. When my parents would use corporal punishment, rage, and argue, the energy surrounding them would permeate every part of our house. I could see that they were not only harming me and my brothers but harming themselves as much as each other. I tried to protect myself, but the psychological effects were profound. I was fearful most of my childhood. I could have benefitted from being taught about the concept of ahimsa.

In a recent workshop I attended chaired by Reverend James Lawson, he shared that Mahatma Gandhi, the father of non-violence, translated the Jain word ahimsa in a positive way. Ahimsa had been translated by many at the time to be do no harm, but Gandhi thought that the non in nonviolence had to be translated in a way that meant that we practice love as the energy that shapes our behavior, even in conflicted situations. This supports the idea that in order to use yoga as a tool for transformation we must act; ahimsa does not mean passivism. Reverend Lawson also shared that ahimsa is the single passageway to experiencing the fullness of life. And to love another as we love ourselves. I believe we owe that promise, to experience the fullness of life, to our children and future generations to come.

Dr. Christopher Chapple, yoga scholar and professor, shared his commentary on Yoga Sutra II:35 which further supports Reverend James Lawson’s point of view:

When in the presence of one established in nonviolence, there is the abandonment of hostility. (Chapple 2008)

When I was the CEO and editor of my wellness magazine, I had the great honor to be in the presence of H.H. The Dalai Lama. I had heard stories prior to our meeting of people who would hear him speak and would remain calm and peaceful for days afterwards. Not only can I confirm that I, too, had this same experience after being with him but I also have this experience after being in a group yoga class. As the old saying goes, you are who you surround yourself with.

Another Sanskrit concept, karuṇā, is generally translated as compassion and self-compassion. Karuṇā signals the intention and capacity to relieve and transform suffering and lighten sorrows. ‘Compassion’ is composed of com (‘together with’) and passion (‘to suffer’) but we do not need to suffer to remove suffering from another person. Doctors have been trained to do this. We could also teach others how to do that too.

To develop compassion in ourselves, we need to practice mindful breathing, deep listening, and deep looking. The Lotus Sutra describes Avalokiteshvara as the bodhisattva who practices looking with the eyes of compassion and listening deeply to the cries of the world[1]. Compassion contains deep concern. One compassionate word, action or thought can reduce another person’s suffering and bring them joy. One word can give comfort or confidence. With compassion in our heart, every thought, word, and deed can bring about a miracle. We need to be aware of the suffering, but we also must retain our clarity, calmness, and strength. We can help transform situations that effect our children. Karuṇā could be a cornerstone of their existence and is applicable in daily life.

There are also clear teachings of Karuṇā in the Yoga Sutras, including Yogasūtra

I:33: maitrī-karuṇā-muditā-upekṣāṇāṁ sukha-duḥkha-puṇya-apuṇya-viṣayāṇāṁ bhāvanātaḥ-citta-prasādanam ॥33॥

Dr. Kausthub Desikachar, a yoga scholar, translates and comments I:33 in the following way:

In daily life, we see around us those who are happier than we are and those who are less happy. Some may be doing things worthy of praise, while others engaged in ignoble deeds. Whatever our usual attitudes towards such people and their actions (Desikachar 2020)

Desikachar further comments:

If we can be happy for those who are happier than ourselves, compassionate towards those who are not as happy, appreciative towards those whose actions are praiseworthy and non-judgmental towards those who commit sins, our minds will remain tranquil. (Desikachar 2020)

This is an important sutra for creating a more grace-filled life. The cultivation of feelings of friendliness and compassion would be extended to all who have ever crossed the path of our life. Imagine what a world like this would be like? There are instances where a person may not delight and be happy over the fortunes of their friend. They might even pretend to be happy for them, but if things are not going well in their day or life, it could be challenging for anyone to align true feelings with delight. This would reflect a mind where division and separation exist. This leads to suffering.

This sutra would be taught to apply to someone we may not call a friend, and/or perhaps have been taught is an “enemy.” If this “enemy” experiences misfortune and we delight in their suffering on a subconscious level, we can create more turbulence rather than serenity of mind. Ease of mind refers to that which does not disturb the vṛttis, or mind waves, either on a conscious or subconscious level.

Rama Jyoti Vernon, author of a book titled Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras; Gateway to Enlightenment, shared:

As Swami Hariharānanda Āraṇya says in his commentaries, ‘To overlook the lapses in others is indifference. It is not positive thinking or denial but is restraining the mind from dwelling on the frailties of others.’ This is so important considering a common theme throughout the Sutras is that if we dwell on the defects of others, we take on those defects. (Vernon 2017)

The author goes on to say that,

As the Swami continues his commentaries, he writes, ‘Feelings of envy, cruel delight, malevolence or anger disturb the mind and prevent its attaining concentration. By cultivating the opposite feelings, the mind can be kept pleasant and happy, free from any disturbing element, then it can become one-pointed and tranquil. (Vernon 2017)

Thinking back to my childhood as it relates to this commentary, I remember struggling with concentration. Taking tests were difficult because I could not focus for long periods of time. Practicing yoga has helped me, as it would children, learn how to calm my mind and remain tranquil even in situations to require long periods of concentration. Instead of rushing through tasks, I’ve learned how to remain undisturbed and tranquil so that I can slowly, and effectively, accomplish more in a joyful way.

Ahimsa and Karuṇā, taught together, could bring about a global shift of empathy. Patañjali gives specifics to what we now call positive thinking but is essentially honoring our emotions and senses.

The practice of Yoga seems to make our conscience more sensitive. This is what the commentaries of Vyāsa refer to in Sutra II:15 when he says, ‘To the yogin who is as sensitive as an eyeball, the world is painful.’ The analogy of the cobweb is used, when it is brushed on the less sensitive skin of the forearm, we will not feel it. But if we brush it across the ball of the eye, it is painful. As our conscience becomes more developed through our practices, we will instantly feel the effects. (Vernon, Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras; Gateway to Enlightenment Chapter Two 2018)

Vernon further states that:

Through the practice of ahimsa, we can learn to walk softly upon the earth, and speak softly from our heart. The commentary that alludes to the Yogin, who is as sensitive as an eyeball, also means that as our sensitivity grows through our practices, we are no longer just absorbed in our personal pain, but we then feel the pain of others. Once we face our own tears, we can see and feel the tears of others. (Vernon, Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras; Gateway to Enlightenment Chapter Two 2018)

This leads to Karuṇā, and growing compassion leads us back to Ahimsa; and together they create a more peaceful heart and mind.

Human rights must include access to yoga and other wholistic solutions, including health literacy. The definition of health literacy was updated in August, 2020 with the release of the U.S. government’s Healthy People 2030 initiative (Prevention 2020). The update addresses personal (and organizational) health literacy, which could be supportive of policy changes which would enable this to become a reality. The new definition outlines that people should have an ability to use health information, rather than just understand it. If we, through this initiative, are able to make “well-informed” decisions don’t we have a responsibility to provide our children and future generations new tools to develop their body, minds, and emotional life in a healthy way? I believe so. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

Businesses, educators, community leaders, government agencies, health insurers, healthcare providers, the media, and many other organizations and individuals all have a part to play in improving health literacy in our society. (Prevention 2020)

The yoga community exists as community leaders (and educators) and together, with the others identified, we could be a part of a positive radical shift in the future of the United States. We could then take these teachings to a global governing body, like the United Nations and/or The World Health Organization and work together for the common good of all nations, people, beings, and the planet.

As yoga teachers, we can teach children how to identify their internal world, to investigate their mind and emotions. The could radically change how, as a society, we interact with each other and the world and we could call into existence a new future where citta-bhavana (the development or cultivation of the heart/mind) and metta-bhavana (the development/cultivation of lovingkindness) is normalized and offers transcendence.

Transcendence, the very highest and most inclusive of holistic levels of human consciousness, would be possible for anyone and everyone. The ways and means of achieving this through yoga, could be tailored to young minds. This will revolutionize behavior. We as a species can learn to relate to oneself, to significant others, to human beings in general, to other species, to nature, and to the cosmos in an empathic way.

BibliographyAranya, Hariharananda. 2017. Yoga Sutra Study. Accessed April 15, 2021. https://yogasutrastudy.info/yoga-sutr....

Bachman, Nicolai. 2011. "The Path of the Yoga Sutras: a practical guide to the core of yoga." In The Path of the Yoga Sutras: a practical guide to the core of yoga, by Nicolai Bachman, 143. Colorado: Sounds True, Inc.

Bachman, Nicolai. 2011. "The Path of the Yoga Sutras: a practical guide to the core of yoga." In The Path of the Yoga Sutras: a practical guide to the core of yoga, by Nicolai Bachman, 143. Colorado: Sounds True, Inc.

Chapple, Christopher Kay. 2008. "Yoga and the Luminous; Patañjali’s Spiritual Path To Freedom." In Chapple, Christopher Kay, by Christopher Kay Chapple, 175. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press.

Courtney E. Ackerman, MA. 2021. What is Self-Transcendence? Definition and 6 Examples. 02 18. Accessed April 15, 2021. https://positivepsychology.com/self-t....

Desikachar, Dr. Kausthub. 2020. Viniyoga Singapore. Accessed April 15, 2021. https://www.viniyoga.com.sg/yogasutra....

Maki, BhVni Silvia. 2013. "The Yogi's Roadmap." In The Yogi's Roadmap, by BhVni Silvia Maki, 134. Hawaii: Viveka Press.

Prevention, CDC and. 2020. Health Literacy in Healthy People 2030. Accessed April 15, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy/le....

Vernon, Rama Jyoti. 2017. "Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras; Gateway to Enlightenment Chapter One." In Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras; Gateway to Enlightenment Chapter One, by Rama Jyoti Vernon, 99. Oregon: Lighthouse Publishing .

Vernon, Rama Jyoti. 2018. "Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras; Gateway to Enlightenment Chapter Two." In Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras; Gateway to Enlightenment Chapter Two, by Rama Jyoti Vernon, 172. Oregon: Lighthouse Publishing.

Wikipedia. 2007. Secular Ethics. August 1. Accessed April 15, 2021. Https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Secular....

September 25, 2023

Paramahansa Yogananda, Jesus Christ and the Self-Realization Fellowship

The first passenger boat sailing from India to America after the end of World War I carried a passionate and devoutly spiritual Indian monk. Three years after founding a yoga school for boys in Bengal in 1917, Paramahansa Yogananda had a vision that it was time to bring the spiritual wisdom of India to the West. Not only would he become world famous for introducing millions to the teachings of meditation and Kriya Yoga through his global organization, but his legacy includes his mission to “reveal the complete harmony and basic oneness of original Christianity as taught by Jesus Christ and original Yoga as taught by Bhagavan Krishna; and to show that these principles of truth are the common scientific foundation of all true religions.”[1]

Yogananda arrived in the United States and “was incredibly successful due to his appealing personality and his willingness to adapt his teachings of Yogoda to Western Audiences.”[2] “The yogi persona appealed to American audiences because it combined the magical allure of the exotic Orient with the universal authority of modern science. The thing is those early twentieth-century Americans pictured the yogi as an ‘Oriental’ man in a turban.”[3] In the year Yogananda landed in Boston, provincial roots of Indian nationalism could be traced to Bengal. Yogananda told his father he’d go to America for four months, although he wouldn’t return to India for fifteen years.

When Yogananda left India in 1920 the deep seeds of change were imbedded in the culture. Historically, realizing that a united India was a strong India, the British decided to separate Hindus and Muslims. This policy left a deep impact on the Indians which eventually led to their strive for independence. Although Yogananda was not overtly political while living in India, his deep love for his country (and for honoring the spiritual teachings of India) would never be far from his mind. Although he spent most of his life living in the United States, his teachings would impact the world. He did return to India though, triumphantly, as the founder of what was to become a worldwide organization of his making called the Self-Realization Fellowship (SRF).

At the time Yogananda arrived in the United States, the country was in a decade of change. America was untethered from war, and celebrating, but still haunted by its weight. Peacetime expansion and prosperity raised the standard of living for millions. America had become a world power and was no longer considered just another former British colony. The decade was one of learning and exploration, exciting progress, and cultural conflicts. The swelling of cities, the rise of a consumer culture, and the “revolution in morals and manners” represented liberation from the restrictions of the country’s Victorian past. There were clashes, though, over such issues as foreign immigration, prohibition, evolution, race, and women’s roles. It was a time of profound social changes with a “culture ripe for a Vedic tidal wave” [4] which Yogananda would eventually tap into. Even Carl Jung stated that “the West will produce its own yoga, and it will be on the basis laid down by Christianity.”[5]

Although a highly influential guru named Vivekananda (who came to America before Yogananda) is recognized as the person who introduced Hinduism at the Parliament of the World’s Religions in Chicago in 1893 (and established Vedanta centers in the West) it is Yogananda who’s mission and work continues to be remembered and praised for “demonstrating to the world the tremendous value of India’s spirituality.”[6]

According to Williamson, “Vivekananda and Yogananda were successful in transplanting their own versions of Hinduism to America. It was Vivekananda who ‘preached the good news of an impersonal God based on Vedanta’ and Yogananda who stressed heartfelt devotion to a personal God.” [7] Foxen writes that “despite his extraordinarily long shadow, Vivekananda was actually a rather minor presence in the landscape of American Yogis.”[8] Although his autobiography, or auto-hagiography, “as Robin Rinehart coined,”[9] is undoubtedly his most famous work, Yogananda would become a prolific author and poet, and “entrepreneur who sold yoga lessons by correspondence, and as a magazine editor.”[10]

America (at the time) was ready for a new way to spiritually gather and ready for Yogananda’s unique integration of “traditional Indian thought, modern science, and prevailing Western metaphysical notions of will, mind, and consciousness” and in the “esoteric practice of Kriya Yoga, the goal of which is nothing short of total enlightenment.”[11]What is clear is that Yogananda was among the first to “establish the bridge between the esoteric techniques of premodern hatha yoga and the postural practice of today.”[12] His “leadership in the global interfaith movement and the deep and abiding interest in Jesus and Christianity that was a central feature of his identity”[13] rivals his efforts to remain “relevant and pragmatic simultaneously weaving in a distinct spiritual agenda” that “would come to bear fruit as his popularity soared.”[14]

Early on in his career he moved from city to city and offered the public “a series of free lectures that led into private lessons and dyadic services for a fee.” Yogananda, and others on this circuit, would freely “borrow and modify ideas and practices” and present it to US audiences as ancient yogic wisdom from India.[15] Deslippe wrote about this “dissemination of yoga, taught by the ‘Swami Circuit’ that lectured wherever there was a sizeable number of people”[16]While traveling, Yogananda even visited the infamous Great Oom, aka Pierre Bernard, and ended his talk with “a song, accompanied with an Indian instrument that he played.”[17] Yogananda’s tireless efforts to spread his teachings paid off. At the time, to study with a teacher was “costly, and those that did so were either affluent or dedicated enough to enroll at a significant financial sacrifice.”[18]

He appealed most strongly to women and to the “restless souls in the liberal Christian tradition” who “longed for mystical experience or religious feeling” who valued “meditation” and “prized immanence in humans and nature.” They “expressed a cosmopolitan appreciation” for “religious diversity, and they emphasized self-expression.” He also attracted Christians primarily from liberal Protestant traditions and “those interested in spirituality outside American religious mainstream.” They were drawn to “the authority of an Indian swami” and to his “focus on the experience of the divine, his integration of body, mind, and spirit” in an era when there was deep interest in learning and exploration and in health and the body.[19] More importantly, audiences found his instruction attractive precisely because he “integrated scientific, positivistic, and pragmatic concerns with a robust affirmation of transcendence that allowed space for the miraculous.” [20]

Yogananda, devotional to the core, had a personality that audiences adored. Not only was his message distinctive, patterns of immigration between the Civil War and the Great Depression highly favored the growth of Western European Protestants and Catholics in the United States at the time. Also, the passage of strict immigration quotas at the time severely limited Asian entrance in the U.S. This ensured that Yogananda would become something of an isolated carrier of instruction in yoga and Eastern philosophy to the West. Foxen nominates him as “the best exemplum of an early Western Yogi that history can give us.”[21] He wasn’t the first as that title seems to go to Vivekananda. Yogananda, though, certainly has stood the test of time. His living legacy includes five hundred centers and meditation groups worldwide. His big claim to fame appears to be his celebrated Autobiography of a Yogi [published in 1946 and at last count has sold over 4 million copies and been translated into thirty-three languages]. Despite this literary accomplishment, the respondents to my ethnographic research project are unsure if his legacy will endure the test of time but given his imprint on the American spiritual landscape, Neumann says that “it is appropriate to call him the Father of Yoga in the West”.[22] as his followers of SRF do.

Yogananda’s “affection for Jesus and the New Testament makes him an awkward fit for many yoga scholars, though this need not be the case, since his interest in Jesus and Christianity puts him in good company with many other contemporary yoga teachers and Hindu intellectuals”[23] and as Yogananda “did think that the yoga practices that deserved most attention were those that led to God-realization” the “teleological interest within most yoga scholarship on the emergence of contemporary secular yoga, which focuses on postures, health, and mental well-being, has led to the neglect of individuals who do not fit that pattern.”[24] One of my personal goals is to help change that.

As a part of my Master's of Yoga Studies class in Modern Yoga through Loyola Marymount University I decided to apply for and carry out an ethnographic research project on Yogananda’s legacy. My Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved study was carried out via an online survey tool with adherence to all IRB protocols. The survey entailed recruitment of participants who had been or were currently members of SRF. This was done through online channels and included two participants I knew personally. To protect the privacy and confidentiality of the participants no personal identifiable information was collected.

For the survey, participants were asked a series of questions about what brought them to the SRF, their thoughts as to how Jesus Christ fits within the lineage, Jesus’ role within Kriya yoga (to the extent they were able to share due to strict parameters around the community’s adherence to a respect of keeping secret the sacredness of the teachings), and thoughts about the legacy of Yogananda as it relates to his teachings of Christ.

After reviewing the thoughtful and generous comments, overwhelmingly the participants shared that when they mediate, they feel closer to God and at peace. One respondent shared that they felt Yogananda’s compassion and inspiration is his legacy and at the “rawest form of the teachings, Christianity is not at the center.” Interesting considering Yogananda wanted to “revive” the essential unity of “Original Christianity”[25] as taught by Christ and “Original Yoga” as taught by Krishna. Most of the respondents mentioned the non-judgmental, open, and accepting community had fulfilled their expectations: SRF has been “a place ideologically to belong” and that the enlightened wisdom and embrace of Paramahansa Yogananda and SRF’s spiritual lineage had taught them to “attain direct personal contact with God through divine meditation.”

But before we go on, let’s establish just what this spiritual lineage is. The teachings of the SRF have been passed from guru to disciple through a linage of teachers that stretches back thousands of years. According to Yogananda, a “deathless” guru who lived in the Himalayas, Babaji-Krishna, directed his disciple, Lahiri Mahasaya, to reintroduce the meditation science of Kryia Yoga to the world. Jesus had appeared to the yoga master Babaji and asked him to send someone to the West to spread the teachings of original Christianity and learn how to receive him through deep meditation. Lahiri Mahasaya passed the teachings onto his disciple, Sri Yukteswar, who eventually would become the guru of Yogananda. Yukteswar would become famous for completing two commissions: writing a book on the underlying unity between the Christian and Hindu scriptures and to train Yogananda for his mission to spread the teachings of yoga to the West.[26]

Yogananda’s mission, as the world would come to learn more about in Yogananda’s famous book Autobiography of a Yogi, was foretold to his mother while he was still a baby. Lahiri Mahasaya, his mother and father’s guru, declared to his mother that her tiny son would be a yogi. Not just a yogi, but a “spiritual engine” who would “carry many souls to God’s kingdom.”[27]

Gyana Prabha Ghosh, Yogananda’s mother, passed away while he was still young. Her death had a profound impact on his life and teachings but his guru, Sri Yukteswar, forever remains one of the most important influences in Yogananda’s life. Yukteswar’s mission for Yogananda, “to teach yoga and the harmony between Krishna and Christ”[28]became much more than that. Yogananda tried to show the underlying unity of all religions. Although Yukteswar wrote a treatise on the Vedas and the teachings of Jesus Christ, it’s Yogananda who expounded on this by pointing out the parallels of the Bhagavada Gita and the Gospels while explaining the terminology and the teachings of the yogi, Jesus Christ. Yogananda saw Christ as a yogi. Yogananda also eventually established Christ within his own lineage within the “dominant currencies of spiritual and cultural capital in the romanticized Asian marketplaces of the West”[29] which is clear when you visit a Sunday SRF Inspirational Service, as I did.

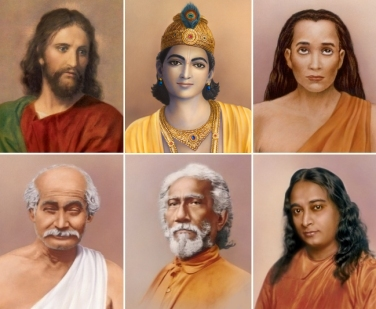

At the front of each of the over 500 worldwide SRF centers there are images of Jesus Christ, Krishna, Babaji-Krishna, (L to R top row in image), Lahiri Mahasaya, Sri Yukteswar, and Yogananda (L to R bottom row in image). During my SRF visit it was the first time that I had experienced a service where Hindu and Christian teachings were delivered in a lecture about karma. Yogananda’s “embrace of Christ” at the time enabled him to “reconfigure for millions the way they understood and related to Jesus. His work “gave many disaffected Christians a path to forming a more comfortable relationship with the tradition of their birth”[30] which had an eerie resonance with me as a former Catholic. It is also important to note that because Kriya Yoga requires initiation and calls for “committed and sustained practice” I was unable to meet the time requirements to study the “technique via the series of lessons that Yogananda composed and left behind.” Despite this fact, as an ethnographer and scholar, I believe that objectivity remains present in this paper.

Although details about the specific Kriya Yoga techniques taught in the lessons were not discussed in the Inspirational service, we used a guided “conscious muscular contraction and relaxation” and breathing (with eyes closed) while internally gazing above and between our eyebrows (the third eye) to become “intuitionally in tune with the Cosmic Vibration” from the “infinite reservoir of the cosmos.”[31] Learning to bridge the gap between yoga, which Yogananda associated with Hindu traditions, and Christianity was instrumental to his mass appeal. I was able to witness the teachings of “great masters and yogic saints” to “tap into the true nature of omnipotence” just as Yogananda’s living teacher had done. [32] Because Yogananda “decreed himself to be the last in the line of Kriya Yoga gurus (in the West) the lessons have become guru in his stead.”[33]

The scientific Kriya Yoga of his lineage, Yogananda said, “consists of magnetizing the spinal column and the brain, which contain the seven main centers, with the result that the distributed life electricity is drawn back to the original centers of discharge and is experienced in the form of light,” thus freeing up the “spiritual Self” from physical and mental distractions. [34] So popular, even now, is Yogananda “that therapists, Yoga teachers, and gurus have attempted to establish their credibility by claiming a connection to him.”[35] The best-known Americans “with links to Yogananda are a pair of direct disciples” who “both have been teaching on their own for more than forty years and say they offer the same practices their guru authorized but in a different format from SRF’s.” [36]

Yogananda was not the first missionary of universal Hinduism, but he was more successful than his predecessors, including Vivekananda. Was Yogananda driven to outshine Vivekananda or felt inspired by his success? Did he consciously emulate Vivekananda? “Vivekananda’s emphasis on meditation and self-realization appealed to many countercultural Americans who rejected mainstream institutional forms of Protestant Christianity for new metaphysical movements, such as Christian Science and New Thought. Vivekananda and these Americans were all interested in wedding metaphysics with modern ideas and values as well as the aim of self-realization.[37] but none of the prior Indian spiritual teachers (including Vivekananda) “established a movement of comparable size or duration.” Vivekananda “rehabilitated yoga to align with neo-Hindu reform movements and to appeal to a bourgeois western audience.”[38]Vivekananda even wrote in his famous book, Raja Yoga, that it was the “highest of all yoga’s,”[39] Yogananda, though, embodied “charisma in both the technical and popular senses.” This “creative entrepreneurial religious figure seemed made for the modern American age of consumption.” His ministry revealed how “missionary Hinduism’s success hinged on a deep understanding of Christian belief and practice. The scope of his ambitions far exceeded the small target audience of Theosophists and New Thought practices he effortlessly drew. Seeking to win over large numbers of Americans, he routinely appealed to the Christian mainstream.” Using “theological discourse familiar especially to American Protestants, he presented yoga as the essential practical tool” that led to “intimate communion with God.” His teaching was “less an integration of the two religions than a reinterpretation of Christianity in light of Hinduism.” “This construction of yoga further positioned India as a place ready and willing to save alienated westerners from the failures of industrial capitalist modernity.” [40]

The SRF compiled Yogananda’s writings and published a book that “aims to recover what Yogananda believed were major teachings lost to institutional Christianity. Among them was the idea that every seeker can know God not through mere belief but by direct experience via yoga meditation.”[41] Quoting the Bible throughout the book, Yogananda focuses on an essential message: ‘Be still and know that I am God.’ which he felt was the key to the science of yoga.”[42] The Yoga of Jesus is Yogananda’s reflections of Christ’s teachings as they align themselves with an East Indian point of reference going as far to say that yoga is “scientific union with God.”[43]

Yogananda regularly explained how the New Testament, properly understood, spoke “about yoga and revealed Jesus as the consummate yogi.” He often expounded on the Bible as the “partial revelation of a universal Indian dharma” that “elucidated and fulfilled all other religions.” Yogananda’s guru, Swami Sri Yukteswar, “planted the seeds for what would later become Yogananda’s teachings of ‘original Christianity’ in America.”[44] And since “Jesus Christ was merely a later avatara of the head of Yukteswar’s Kriya-yoga tradition, Babaji-Krishna, Yukteswar, and Yogananda were in a lineage of spiritual practice bearing a more ancient spiritual practice than Christianity.”[45] And, in several ways, Yogananda “implicitly portrayed himself as a Christ figure”[46] although his reticence to claim divine status directly reflected “his understanding of the humility a teacher was expected to display.”[47] Late in life, Yogananda shares [in his autobiography, in the Encinitas hermitage] he “beheld the radiant form of the blessed Lord Jesus” and gazing into his eyes he “intuitively understood the wisdom conveyed.”[48] This entrepreneurial godman “consciously constructed and successfully marketed” his teachings by “associating them with their own personae as well as spiritual wares that were attractive to large target audiences of… spiritual seekers.”[49]

Continuing to explore the results of my ethnographic research into Yogananda’s legacy, I concluded that how the members of the SRF understand Jesus Christ to fit within their yoga lineage varies from person to person, but most indicated that Jesus Christ was one of many prophetic master’s at the time. One respondent felt that the “power brokers at the time used Jesus to control the masses; meaning he had a better public relations group to get the word out.” Some respondents felt that God is a connector of sorts; a central character brining Christianity and Hinduism together (not unlike Yogananda) and that God’s role with yoga is to “help humans deal with each other – or simply said, to help humanity.”

One person shared that ‘Christ was a man just like I am, and just as all of the great prophets and wisemen that have walked our planet have been. Jesus ultimately embodied what Yogananda teaches.’ Yet another shared that they had not considered Jesus ‘fitting into’ the lineage but considered the connection rather as a broader, less direct, reflection of an emergence of ‘God incarnate’ with essential teachings, particularly necessary to the time, to uplift the world. The harmony of it is clear – Krishna embodies Vishnu as a force of preservation, sustenance, nourishment, and healing. Christ is that – more than love, Christ came at a time when humanity threatened to destroy itself. While Jesus Christ’s message can be manipulated to manipulate and cause harm, sometimes I think it is the only thing keeping communities and societies in the west from self-destruction and collapse. His [Yogananda’s] teachings of love, of the possibility of a personal relationship with God, of the approachable presence of embodied divinity, of forgiveness of sin and an invitation to experience enlightened being, to sing with Love and dance with God – There is a high and holy, haunting resonance.” Yogananda “proclaimed that it was Babaji and Christ together who had, through him, sent the teachings of Self-Realization to teach men to attain direct personal contact with God through divine meditation. According to Yogananda, Jesus Christ himself taught his disciples a technique like Kriya Yoga to help them remember the ‘inward communion with God.’”

Personally, I now understand the appeal of Yogananda’s unique contribution. I wonder now if I had been living during his life if I would have been drawn to seek out his message of the “importance of ‘Self’ and ‘Self-realization’[50] although I also appreciate Vivekananda’s “reinterpreted, simplified and modernized Vedanta” presented as the exemplary form of ‘Universal religion’ capable of catering for all religious needs through different types of yoga.”[51] Yogananda’s universal laws of transformation, tools for transcendence, and messages of compassion, peace, and visions for living in spiritual communities fit nicely within my Buddhist sensibilities. As a lifelong seeker and practitioner of yoga, I have been a “bricolage builder” of snippets of Christianity, Hinduism, and Buddhism (what has been referred to as an assembled religious identity). This ability to reconfigure, for myself, a higher power of my understanding that is full of light, love, compassion, and wisdom does not fit into any specific organized religion but is my yoga. It fills me with peace, well-being, and harmony. That same experience seems to reflect the members of SRF that participated in this project. Yogananda assumed the identity of a modern yogi, rooted in ancient Sanskrit texts but also deeply conversant with Christianity, the modern world’s most widespread religion. His message centered on yoga meditation as a practical tool for communing with God, situated within a larger body of Indian religious and philosophical teachings.”[52]

“Yogananda came to view his own teachings themselves as ‘the guru’, a somewhat ‘novel idea at the time,’ but one that anticipated a recent trend in yoga.”[53] “As Modern Yoga became progressively more attuned to the secular, pragmatic and rationalistic temper of the West, it was accommodated in a twofold manner: at the margins of ‘health and fitness’ concerns on one hand, and within the conceptual and institutional sphere of alternative medicine on the other.”[54] Modern Yoga became a live link between East and West: a bridge through which personal, cultural, institutional, and other exchanges could take place.[55] The members of SRF show “tremendous dedication to their daily practices” and a pledge to God and the six gurus of the Self-Realization Fellowship lineage of ‘unconditional love, reverence, and loyalty forever.’”[56] “Unlocking the mystery of Yogananda himself”[57] and how Christ fits within the lineage of SRF has been truly a privilege and honor. What will his enduring legacy be? As Yogananda himself wrote in Yogoda in 1925, I think it will continue to “bring you in touch with the Superconscious (the soul and the Great Spirit), giving you wonderful peace, harmony and poise of mind so essential to the higher living of life.”[58] The “scaffolding of his work” is “fundamentally Indian”[59] and answers questions about “the nature of the body, the soul, and the mind.”[60]

IRB protocol number: LMU IRB 2021 FA 27-R

[1] The Self Realization Fellowship, “Lineage and Leadership”, accessed November 2, 2021, yogananda.org/lineage-and-leadership.[2] Georg Feuerstein, The Psychology of Yoga: Integrating Eastern and Western Approaches for Understanding the Mind (Shambhala, 2014), 11.[3] Anya P. Foxen, Inhaling Spirit: Harmonialism, Orientalism, and the Western Roots of Modern Yoga (Oxford University Press, 2020), 30.[4] Philip Goldberg, American Veda: From Emerson and the Beatles to Yoga and Meditation How Indian Spirituality Changed the West (Harmony, 2013), 112.[5] Foxen, Western Roots of Modern Yoga, 223.[6] Yogoda Satsanga Society of India, “Modi’s Address March 7, 2017”, accessed November 3, 2021, yssofindia.org/blog/indias-pm-releases-stamp-commemorating-yss-centenary.[7] Lola Williamson, Transcendent in America: Hindu-inspired meditation movements as new religion (New York University Press, 2010), 55.[8] Anya P. Foxen, Biography of a Yogi: Paramahansa Yogananda and the Origins of Modern Yoga (Oxford University Press, 2017), 45.[9] Foxen, Paramahansa Yogananda and the Origins of Modern Yoga,17.[10] David J. Neumann, Finding God through Yoga: Paramahansa Yogananda and Modern American Religion in a Global Age (The University of North Carolina Press, n.d. Chapel Hill, 2019), 17.[11] Foxen, Paramahansa Yogananda and the Origins of Modern Yoga, 87, 125.[12] Foxen, Paramahansa Yogananda and the Origins of Modern Yoga,126.[13] Neumann, Paramahansa Yogananda and Modern American Religion in a Global Age, 17.[14] Foxen, Paramahansa Yogananda and the Origins of Modern Yoga, 129.[15] Suzanne Newcombe, and O’Brien-Kop, Karen Routledge, Handbook of Yoga and Meditation Studies (Routledge, 2020), 355.[16] P. Deslippe, The Swami Circuit: Mapping the Terrain of Early American Yoga (Journal of Yoga Studies, 2018), 10. [17] Love, The Great Oom; The Improbable Birth of Yoga in America, (Viking, 2010), 40.[18] Deslippe, Mapping the Terrain of Early American Yoga, 29. [19] Neumann, Paramahansa Yogananda and Modern American Religion in a Global Age, 12.[20] Neumann, Paramahansa Yogananda and Modern American Religion in a Global Age, 14.[21] Foxen, Paramahansa Yogananda and the Origins of Modern Yoga, 18. [22] Neumann, Paramahansa Yogananda and Modern American Religion in a Global Age, 3.[23] Neumann, Paramahansa Yogananda and Modern American Religion in a Global Age, 18.[24] Neumann, Paramahansa Yogananda and Modern American Religion in a Global Age, 19.[25] Philip Goldberg, The Life of Yogananda: The Story of the Yogi Who Became the First Modern Guru (Hay House, 2018), 149.[26] Ananda, “A place of Awakening,” Accessed October 19, 2021, www.anandapaloalto.org/spiritual-lineage.[27] The Self Realization Fellowship, “Lineage and Leadership”, accessed November 2, 2021, yogananda.org/lineage-and-leadership.[28] Lola Williamson, Transcendent in America: Hindu-inspired meditation movements as new religion, (New York University Press, 2010) 55.[29] Mark Singleton, Yoga in the Modern World: Contemporary Perspectives, (Routledge, 2008), 89.[30] Philip Goldberg, The Life of Yogananda: The Story of the Yogi Who Became the First Modern Guru, (Hay House, 2018), 149.[31] Foxen, Paramahansa Yogananda and the Origins of Modern Yoga, 46. [32] Foxen, Paramahansa Yogananda and the Origins of Modern Yoga, 152. [33] Foxen, Paramahansa Yogananda and the Origins of Modern Yoga, 133. [34] Paramahansa Yogananda, Autobiography of a Yogi, (Self-Realization Fellowship, 1946, 1998), 231.[35] Philip Goldberg, American Veda: From Emerson and the Beatles to Yoga and Meditation How Indian Spirituality Changed the West, (Harmony, 2013), 126.[36] Goldberg, From Emerson and the Beatles to Yoga and Meditation How Indian Spirituality Changed the West, 127.[37] Andrea Jain, Selling Yoga: From Counterculture to Pop Culture, (Oxford University Press, 2014), 34.[38] Newcombe, Yoga and Meditation Studies, 14.[39] Swami Vivekananda, Raja Yoga, (First published 1896, independently published, 2018 (ISBN-13:978-1976913235), 62.[40] Newcombe & Routledge, Handbook of Yoga and Meditation Studies,14.[41] Paramahansa Yogananda, The Yoga of Jesus – Understanding the Hidden Teachings of the Gospels, (Self-Realization Fellowship, 2007) viii.[42] Yogananda, Understanding the Hidden Teachings of the Gospels, ix.[43] Yogananda, Understanding the Hidden Teachings of the Gospels, 80.[44] CP Miller, World Brotherhood Colonies: A Preview of Paramahansa Yogananda’s Understudied Vision for Communities Founded Upon the Principles of Yoga (Yoga Mimamsa, 2018), 2.[45] Miller, Vision for Communities Founded Upon the Principles of Yoga, 2.[46] Neumann, Paramahansa Yogananda and Modern American Religion in a Global Age, 8-11.[47] Neumann, American Religion in a Global Age, 14.[48] Yogananda, Autobiography of a Yogi, 536-537.[49] Jain, From Counterculture to Pop Culture, 50.[50] Elizabeth De Michelis, A History of Modern Yoga: Patanjali and Western Esotericism, (Continuum, 2005), 120.[51] De Michelis, Patanjali and Western Esotericism, 123.[52] Neumann, American Religion in a Global Age, 27.[53] Neumann, American Religion in a Global Age, 236.[54] De Michelis, Patanjali and Western Esotericism, 15.[55] De Michelis, Patanjali and Western Esotericism, 20.[56] Lola Williamson, Transcendent in America: Hindu-inspired meditation movements as new religion, (New York University Press, 2010) 57.[57] Williamson, Hindu-inspired meditation movements as new religion, 69.[58] Anya Foxen and Christa Kuberry, Is This Yoga?: Concepts, Histories, and the Complexities of Modern Practice,(Routledge, 2021), 168.[59] Foxen, Western Roots of Modern Yoga, 71.[60] Jain, From Counterculture to Pop Culture, 28.

May 18, 2023

Mastering the Art of Yoga: Unveiling my MFA in Yoga Studies

I am thrilled to announce that I have earned my Master's of Fine Arts in Yoga Studies, marking a significant milestone in my journey of spreading the transformative power of yoga. This achievement reinforces my commitment to making a positive impact on the human condition and advancing the cause of human rights, particularly in the realm of gender equality. With this profound knowledge and expertise, my objective remains unchanged: to share the authentic teachings of yoga to the modern world. I am driven to build bridges between diverse countries, religions, faiths, and healing modalities, fostering social and spiritual health in our interconnected global community. Together, let us embark on a path of self-discovery, wellness, and unity, as we embrace the boundless potential of yoga for personal and collective transformation.

May 14, 2021

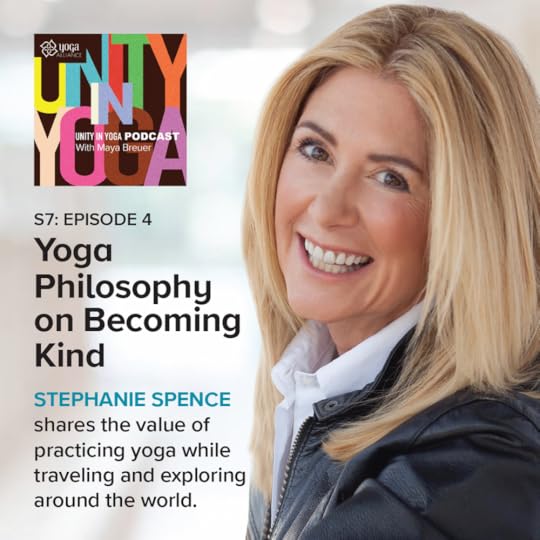

Yoga Philosophy on Becoming Kind

I’m so excited to share I’ve been featured on the Yoga Alliance Unity In Yoga Podcast.

Unity in Yoga engages listeners through the teaching, practice, and discussion of yoga. Host Maya Breuer chats with guests from the yoga and wellness community representing a broad range of cultural and philosophical perspectives in a collective effort to promote: inclusion, accessibility, and better health through yoga.

Listen now! On Itunes or Spotify

“Stephanie Spence shares the value of practicing yoga

while traveling and exploring around the world.

Hear how she learned to listen to an inner voice,

to be comfortable in the stillness,

and to appreciate all of herself including the flaws.”

Season 7, Episode 4.

Deeply honored that I was asked to be interviewed on this podcast. Maya, in case you haven’t tuned in before, is celebrated as one of America’s distinguished Black Yogis by Black Enterprise magazine, Unity in Yoga host ,Maya Breuer is Yoga Alliance’s Vice President of Cross-Cultural Advancement; the co-founder and Emeritus President of the national Black Yoga Teachers Alliance; and a preeminent yoga teacher, speaker, practitioner, author, and community activist.

Thank You ,,Yoga Alliance, ,,Maya, and all of the staff of the Unity In Yoga Podcast.

April 27, 2021

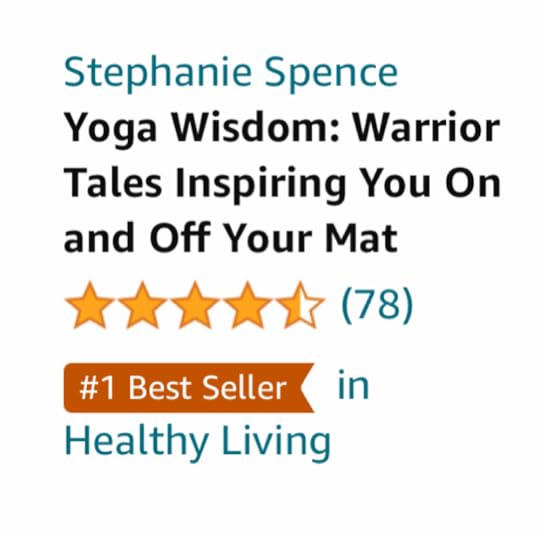

"Yoga Wisdom" Earns Best-Seller Title

My book, Yoga Wisdom: Warrior Tales Inspiring You On And Off Your Mat, became a best-seller this week. After earning multiple literary awards, I thought it just couldn't get any better... and then it did.

Allow me the rare chance to celebrate by sharing some of the categories:

March 28, 2021

Why do we expect yoga to be free?

Equal Pay Day just passed, and it got me thinking. If yoga is a $16 billion industry in the United States, why are yoga teachers paid so little? Is it because 74% of yoga teachers are women? We are the caretakers, the nurturers in our communities, and companies are used to paying women less. To make matters worse, yoga teachers feel compelled to teach for free or at a discount, and students have come to expect it.

Why should yoga be free?

Like many yoga teachers, I was laid off when the pandemic hit. Studios closed and my private clients canceled indefinitely. Suddenly yoga teachers scrambled to offer classes online to replace lost income, and I was struck at how many teachers offered free classes or a “pay what you can” option. This was amazingly generous, but one year later, most online yoga classes and workshops taught by individual teachers still have that option. The competition is fierce online and this has now become the standard. Are other professions offering a “pay what you can” rate? Why do we expect yoga at a discount?

Part of the reason is that yoga is a spiritual tradition and this complicates the feelings yoga teachers have about earning a living from teaching. There is also the concept of seva, which means “service” in Sanskrit. When I’ve been asked to teach for free or do extra jobs in a studio like sweep the floor, sell merchandise or take out the trash, I’ve been told it’s part of seva. This blending of the spiritual tradition with capitalism allows companies to exploit teachers. Meanwhile students have grown accustomed to free yoga classes and seeing their teachers as providing a community service, rather than as trained professionals.

I started teaching yoga in my mid-forties and was an executive at a non-profit at the time. Teaching yoga was a hobby, something I enjoyed doing on the side, so I didn’t pay much attention to the pay or the requests to teach or assist other teachers for free. I was just happy to be teaching and gaining experience. As I taught more though, I wondered if it was possible to teach full-time and earn a decent living.

Most yoga teachers earn $35 to $50 per class at a studio with bonuses for full classes. Some studios pay a per student rate of $2 to $3. If only three students attend, it could mean teaching for 90 minutes and earning $6. Teaching privately is more lucrative, but it takes time to build a client base. After teaching for five years, I had eight classes per week at yoga studios where I earned $45 per class, and two regular privates. In total, I was earning $640 per week gross with no access to health care, retirement or benefits. Needless to say, I had to keep my day job.

This is never mentioned in yoga teacher training. To earn a 500-hour Yoga Alliance teaching certificate, the gold standard in the industry, it costs approximately $10,000. I remember our teacher saying, “you can make really good money teaching yoga.” This seemed to involve a lot of hustle to market yourself on social media, teach as much as possible, and build up a student following so you can charge for retreats and privates. It all sounded exhausting.

It’s ironic that teaching yoga doesn’t align with a yogic lifestyle. Most students have an image of their yoga teachers practicing, meditating and eating healthy meals. The reality is that yoga teachers travel miles to different studios or private homes, in traffic, trying to beat the clock, with little time to eat. When I did have time to practice, I just wanted to lie over a bolster in savasana. The pressure to fill your classes and your schedule to make ends meet is soul destroying. Perhaps that’s why a 2016 study funded by Yoga Journal and Yoga Alliance found that 67% of yoga teachers work less than 10 hours per week, and 33% said it was just a hobby, something they did to make them feel good.

In a $16 billion industry, someone is earning a lot of money from yoga, it’s just not yoga teachers. As we emerge from online yoga classes to once again teaching in person, I hope we can find a new paradigm that is equitable and fair to yoga teachers. In the meantime, if you are offered a “pay what you can” option for a yoga class, please pay the full rate. Show your yoga teacher that you value them and their knowledge.

Sandra is a yoga instructor and Ayurvedic Practitioner in Pasadena, CA. She has advanced training in therapeutic and restorative yoga, and is working on completing her Master’s Degree in Yoga Studies at Loyola Marymount University.

To connect: @smsanchezyoga

February 26, 2021

What is Quantum Yoga?

Ever wonder where all these different "types of yoga" are organically coming from?

I have traveled the earth discovering and practicing with yoga teachers to share with you for the last fifteen years.

I continue to be curious about the ever-changing, ever-evolving world of yoga.

I recently heard of a yoga that I was unfamiliar with, Quantum Yoga.

I reached out to it's original source, Lara Baumann, to learn more about how the Quantum Method of Yoga came about. Following is our brief Q&A.

Stephanie: How did you get started on your yoga path?

Lara: A diplomat’s daughter, I grew up partly in India in Madras, now Chennai. Convalescing from the after-effects of yellow fever, my mother followed the advice of a friend and decided to try yoga. My father organised the best teacher available to the expatriate community in the 1970’s, but alas my mother did not have the patience for yoga. The yogi master was relegated to the children, and as my two older brothers seemed to have better things to do, I at age 4, was the primary recipient of his teachings. My parents reported that I enjoyed the yoga greatly, and I have very vague scraps of memory of doing lion breath with a funny-looking bearded friendly man with big bright eyes, who gave me his full attention. Being the youngest, I was not used to that.

My father was next posted at the United Nations in New York, and my mother sent me to ballet classes. A tomboy at heart, I didn’t like them and soon quit.

It was only many years later, having already studied yoga in depth academically as part of my Masters degree in Religious Studies (SOAS, London) and Comparative Religions (Oxford University), that I rediscovered the asana practice on a 10-day silent meditation retreat at a Buddhist monastery in southern Thailand. Having had the luxury of clearly observing the effects of yoga in the framework of a silent retreat, I knew then without the shadow of a doubt, that asana-vinyasa was far more effective and powerful than any other exercise I’d known, and more importantly a valuable compliment to meditation. When I returned to London, I searched out the only regular yoga class – Iyengar - in walking distance to my apartment in Notting Hill (unimaginable now that you can find yoga centres on every corner of this now expensive neighbourhood), and attended regularly. The next quantum shift came when a naughty cover teacher introduced us to Ashtanga Vinyasa. Then I was completely hooked and willing to cycle across town, early mornings through cold and dark, to Mysore practice at the Royal Homeopathic Hospital in Bloomsbury.

Stephanie: Inspiration for your quantum yoga?

Lara: I soon got heavily into the Ashtanga practice, working on Advanced A & B sequences. To balance out the exhilarating but hyped up effect I would experience, I counter-balanced the Ashtanga with Shadow Yoga, which was much closer the martial arts like Chi Gong, and therefore more calming and grounding. Occasionally I would still do an intensive workshop at the Iyengar Institute too.

However, I found that I would penetrate deepest, when I broke away from any formal style-specific practice, and flowed into a sort of spontaneous and intuitive yoga play. Hitherto inaccessible asana would become possible, but more importantly that elusive and lofty pursuit of “Union with the Absolute”, the definition of yoga I had so often penned down at Uni, in precious moments of absorption, I then realised is not an experience reserved only for dreadlocked sadhus (ascetics) or pure and pious Brahmin (India’s priestly caste).

The yoga scene of the nineties was political. If you were an Ashtangi, you wouldn’t want to be seen doing Iyengar and vice-versa. They all thought Shivananda and related practices like Satyananda etc. was for lightweights, whereas the Shivanandis believed offshoots from the Krishnamacharya lineage never got past the first four limbs of Patanjali’s system of the Eight Limbs (Ashtanga therefore being the biggest misnomer). Then Bikram exploded onto the scene, and things became really heated.

Meanwhile, I had studied both with Sri K Patthabi Jois in Mysore, as well as BKS Iyengar and family in Pune, and was left dissatisfied. I didn’t know yet with total certainty that I had in fact found my guru in Clive Sheridan, but it is Clive’s pranayama instruction and satsang (spiritual discourse) that make him so invaluable and unique. Without meeting the charismatic Danny Paradise, whose approach to Ashtanga was neither fanatical nor cultish, I probably would have stopped.

Having grown up largely in Asia, the holistic approach to health that Ayurveda offers is second nature to me. I’ve always known that there is no one remedy that fits everyone, just as there is no diet that is good for all body types, nor can there be a single yoga sequence that fits everyone at all times. I could see the imbalance and damage the rigid adherence to “the system” was doing to Ashtangis, including myself, not to mention Bikram.

At the same time, my study of quantum physics offered a clear explanation why I was advancing faster and penetrating deeper in my free, conscious and creative yoga sessions. When I allowed myself to stray from pre-fabricated sequences, I was forced to enter a dialogue with the mind-body. Here I began listening to the bio-feedback I was getting, rather than overruling it, lovingly and patiently responding to the emotions generated by physical sensations, and always aiming for balance. Quantum Yoga is a listening practice. The transformative potential of any activity increases in direct relation to the level of consciousness with which it is done. This is especially so for sadhana, spiritual practice. As my guru Clive keeps reminding his students: Pay attention!

Stephanie: How do you use yoga to meet and move through challenges?

Lara: Yoga, and here I mean the entirety of the teachings (not just asana), rouses a faculty of cognition referred to as the buddhi, inadequately translated as “intellect”. The English language does not posses a word for buddhi, because it grew out of a completely different worldview. The buddhi is still part of manas, the mind, and therefore part of prakriti (“nature” or all that is not purusha, “spirit”). The buddhi however is that part of you that recognises the inner turbulence as unreal (“real” in the ultimate sense means permanent and uncaused). It is from here that the longing for space, stillness and bliss comes – our root state. The practice of yoga therefore has equipped me with the ability to differentiate between all that is caused by my mind interacting with an ever-changing world that I am navigating to the best of my ability, and that inner sanctum, which is totally unaffected, and was never born, nor will it ever die. I’m passionately involved in life’s ups and downs, but the true Self dwells in a state of impersonal witnessing. Regular yoga practice and the non-dual state of pure consciousness thus cultivated, brings about an emancipation from the ego-mind, and the identification of the illusion of separation. Life’s challenges can now be tackled with powerful and courageous calm, without the blinding and weakening interference of the “little me”. When there is no more voice insisting that life is not fair, no part of you that has an agenda, nothing left to fix, except whatever challenge is immediately at hand, you are free. This freedom gives me the strength to face life’s many challenges.

Stephanie: What has yoga taught you about life? And yourself?

Lara: This one is tricky to answer, because yoga has been such a long-standing companion to me. It is as natural and necessary to me as brushing my teeth. Yoga has taught me about myself, that the stronghold of the ego is incredibly powerful, and that therefore yoga is not just a goal, but a practice that I must maintain always. Yoga restored my ability to see the wonder that is life. I have infinite gratitude for the teachings that have allowed me to penetrate so deep, and touch on the primordial bliss that I know lies at the basis of all that is manifest.

Lara Baumann teaches the Quantum Method® of Yoga to all levels of students both publicly and privately worldwide.