Stephen Law's Blog

September 14, 2025

J'accuse! The News Agents Investigates: The Rise of the Far Right.

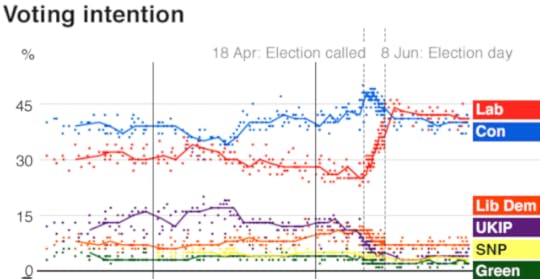

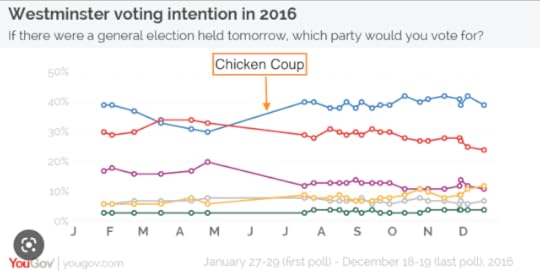

The diagnosis offered by the podcast focuses on centre-right parties adopting the rhetoric/discourses of the far right. Why did they do this? The suggestion made is 9/11 (worries about Muslims), and the fact that centre-left and -right became very similar on economic policy, resulting in the centre-right shifting their focus/arguments to the social/cultural (and thus immigration, etc.) in order to get some distance from the centre-left.

It's also suggested that the far right thrive in times of political turmoil, and that Covid, and now the situation in Gaza, are being exploited (the far right tend to be very pro-Isreal, even while also being quite antisemitic). Online radicalisation also gets a mention.

No mention at all of the left, or left policies, or the left's diagnosis.

The only fairly clearly leftist voice that I could detect was, weirdly, that of a demonstrator that commented only on Israel's relationship with Geert Wilders (a 'Zionist puppet'), a comment that Lewis Goodall then took the opportunity to suggest was antisemitic (which will of course remind listeners of the (false) accusation that the left is riddled with antisemitism).

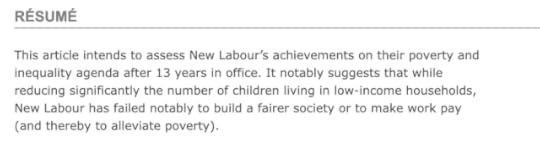

So what is the left's I think very plausible explanation for the rise of the far right? Inequality is ramping up (growing relentlessly, even under New Labour) & ordinary people's lives are getting worse and worse as the result of an oligarchy that relies increasingly on distraction by divide & rule (blame, immigrants, foreigners, muslims, woke...)

The left's solution is to bring in left policies that will *significantly* redress inequality, which centrist politicians - sponsored by oligarchs - will not do. The result of centrist inaction is that the right will only get stronger still as frustrations and (misdirected) anger continue to grow. With the left now effectively removed from the political arena, it's just a matter of time... Eventually: 'Boom!'

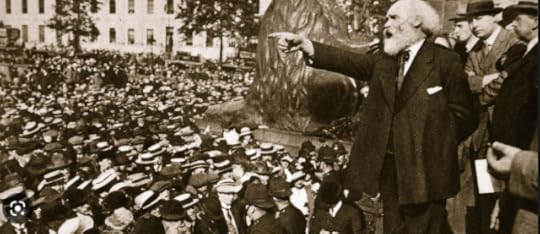

No mention at all of this leftist PoV from The News Agents Investigates. Even if it's wrong, it's surely at least worth mentioning and discussing? It's a very well-known view that's been around a long time. See image for Tony Benn accurately predicting and diagnosing the rise of the far right back in 1982.

To me, the airbrushing out of the left's views and diagnosis, plus the one recognisably left voice that was included being framed and dismissed as that of an antisemitic conspiracy theorist, makes this investigative report look *extremely* biased against the left. Most listeners won't notice though.

The irony is that, if I am correct, then The News Agents - and centrists journalists of the same stripe who habitually airbrush out or smear the left - are actually themselves contributing to the rise of the far right.

I am not suggesting for a minute that this anti-left bias from Lewis Goodall was deliberate. I just think the smearing and airbrushing out of left voices is so much a part of the journalistic culture that it takes quite a bit of effort not to go with that established flow.

Happy to be corrected if you feel I have misrepresented The News Agents here. You can listen to the podcast I am discussing here.

January 23, 2025

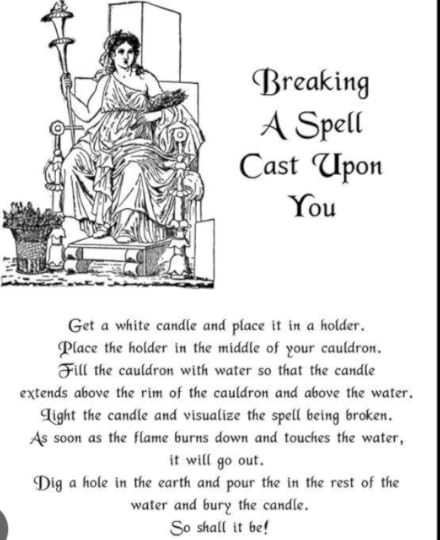

Breaking The Spell: the bizarre, convoluted, and ultimately absurd defence of belief in a good God

Could the universe be the creation of a supremely powerful and wicked deity? Most of us will rightly dismiss that suggestion out of hand. ‘Of course not’, we’ll say ‘Look around you – at all the love, laughter, ice-cream, and rainbows! This world contains far too much good for it to be the creation of such an omnipotent and omni-malevolent deity.’ And there’s no denying that while there is suffering and misery in the world, there is also much good – good of such depth and on such a scale that it really is highly unlikely there’s some evil-God justifying reason for every last ounce of it. And the one thing we can be sure such an evil God won’t allow is gratuitous good – good for which there is no evil-God-justifying reason.

Now of course the objection we have just raised to the suggestion that we are the creation of an omnipotent and omni-malevolent deity is just the mirror image of a much more familiar objection – to belief in an omnipotent and omni-benevolent deity. Just as it strikes most of us obvious that there’s no Evil God given the abundance of good in the world, so it strikes many atheists as just obvious that there’s no Good God either, and on much the same basis – an abundance of evil.

So how do those who believe in a Good God respond to the problem of evil? Some construct theodicies. They appeal to free-will. They say this is a vale of soul making. They say no pain, no gain. They say much pain and suffering is caused by laws of nature required for greater goods. Or they say that just because we cannot think of a reason for all these evils, doesn’t allow us reasonably conclude there is no such reason. Such reasons could easily lie beyond our limited ability to think of them.

Now, interestingly, all these strategies can be employed by someone intent on defending belief in an Evil God. Indeed, it’s fascinating to explore Evil God apologetics and the mirror manoeuvres that can be made. It’s not just intellectually interesting. It gives you an insight into a certain mindset – a certain way of looking at things – on which everything fits, everything makes sense given – everything really can be squared with – the existence of a supremely malevolent deity. It’s a mind-set exhibiting ingenuity, imagination, and lunacy in equal measure.

We who live in the Judeo-Christian West are very familiar with the mirror version of that metaphysical mindset. Indeed, Good God theodicies, appeals to Good God’s mysterious ways, and so on, are such a familiar part of our cultural landscape – are so habitually trotted out – that we don’t even notice their bizarre, convoluted, and ultimately absurd character. Ours is a mindset that has acquired the anaesthetic of familiarity.

Our first encounter with the mirror, Evil-God version of this mindset can, for this reason, be a very powerful and disturbing experience. We’re suddenly presented with our mirror selves, our mirror culture, our mirror beliefs and mirror intellectual strategies – and the absurdity of our own metaphysical edifice becomes gloriously apparent, at least for a moment. We are afforded a brief glimpse of how things really are, and what we’re really like.

The Evil God Challenge is presented in this short cartoon.

(This post is the Foreword I wrote to John Zande's On The Problem of God: Owner of All Infernal Names)

January 19, 2025

'So What's It All About Then?' The Meaning of Life Explained!

According to some, questions about the meaning of life are inextricably bound up with questions about God and religion. Without God, it is suggested, humanity amounts to little more than a dirty smudge on a ball of rock lost in an incomprehensibly vast universe that will eventually bare no trace of us having ever existed, and which will itself collapse into nothingness. So why bother getting out of bed in the morning? If there is a God, on the other hand, then we inhabit a universe made for us, by a God who loves us, and who has given us a divine purpose. That fills our lives meaning.

But is God, or religious belief, really a necessary condition of our leading meaningful lives? How, exactly, is the existence of God supposed to make our lives meaningful? And if meaningful lives are possible whether or not there is a God, what makes for a meaningful existence? This chapter examines these and related questions.

What do we mean by a 'meaningful life'?

One of the difficulties we face in giving an account of how humanism, or any other view for that matter, can allow for the possibility of a meaningful life is in identifying what constitutes a meaningful life in the first place. I imagine there is a broad consensus that certain answers won't do.

First of all, surely there is more to leading a meaningful life than, say, feeling largely happy and content. Someone continuously injected with happiness-inducing drugs might have a pleasurable time, but that wouldn't guarantee a particularly worthwhile or meaningful existence.

Secondly, there are presumably more ways of leading a meaningful life than just doing morally good works. While leading an exceptionally virtuous existence is one way in which one might, perhaps, have a meaningful existence, it is not the only way. Many great artists, scientists, explorers, musicians, writers and sportsmen and women have, surely, lived meaningful lives, despite not being noticeably more moral than the rest of us (indeed, some have been rather immoral).

It seems that not only is a lifetime spent performing good deeds not necessary for a meaningful existence, neither is it sufficient. Consider a man living under a totalitarian regime who devotes his entire life helping sick children but only because he fears the terrible consequences of not obeying his orders. Has he led a meaningful life? Despite his good deeds, it is by no means obvious that he has. What this example illustrates, perhaps, is that, in order for your life to be genuinely meaningful, you must exhibit a kind of autonomy. You must be self-directed, rather than just following the instructions of another.

I suspect many of us would add that someone might think their life had been a pointless waste of time when it was in fact highly meaningful. Conversely, I suspect most of us would allow that someone might think their life highly meaningful when in truth it was not.

For example, has a woman who has successfully devoted her life to leading a white supremacist movement thereby led a particularly meaningful existence? She and her followers might think so. But does that guarantee that she has? It seems to me the answer is ‘no’. To lead a meaningful life, you need not be particularly moral. But surely, if your life's central project is downright immoral, then it cannot give your life meaning. Because of the immoral nature of this racist woman's project, it cannot make her life meaningful (though her life could still be meaningful for other reasons, of course). That, at least, is how my intuitions run (though I acknowledge others will disagree).

Also notice that a meaningful life might presumably end in the failure of its central project. Consider Scott of the Antarctic, who struggled valiantly to be the first to reach the South Pole. Despite his failure, Scott's life is held up by many as a shining example of a life well-lived. The same is true of many other heroic failures, including for example, those Germans who tried, but failed, to assassinate Hitler in order to bring a quick end to the Second World War.

We have seen that there are, perhaps, certain features a life must possess if it is to be meaningful – a not immoral project or goal pursued in a self-directed way, for example. But is even that sufficient? It seems not, as a lifetime spent pursuing a worthwhile goal by an enthusiastic incompetent is often rather more farcical than it is meaningful.

Is the search for THE meaning of life a wild goose chase?

The above section is intended to illustrate the point that it is rather difficult to provide a watertight philosophical definition of what makes a life meaningful.

Part of the difficulty we face, here, perhaps, is that we assume that in order to explain what makes for a meaningful life we must identify some one feature that all and only meaningful lives possess: that feature that makes them meaningful. But why must there be one such feature? Perhaps the search for the meaning of life – this single, elusive, meaning-giving feature – is a wild goose chase. Perhaps the concept of a meaningful life is what the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein calls a family resemblance concept. The members of a family may resemble each other, despite there being no one feature they all have in common (e.g. that big nose or those small ears). Wittgenstein supposes the same is true of, for example, those things we call ‘games’. Activities such as backgammon, solitaire, football, chess and badminton resemble each other to various degrees. But is there one thing all and only games have in common, in virtue of which they are all games? Wittgenstein thinks not:

Don't say: ‘There must be something common, or they would not be called “games” – For if you look at them you will not see something that is common to all, but similarities, relationships, and a whole series of them at that. To repeat: don't think, but look! – Look for example at board-games, with their multifarious relationships. Now pass to card-games; here you find many correspondences with the first group, but many common features drop out, and others appear. When we pass next to ball-games, much that is common is retained, but much is lost. – Are they all ‘amusing’? Compare chess with noughts and crosses. Or is there always winning and losing, or competition between players? Think of patience. In ball-games there is winning and losing; but when a child throws his ball at the wall and catches it again, this feature has disappeared …[T]he result of this examination is: we see a complicated network of similarities overlapping and cross-crossing: sometimes overall similarities, sometimes similarities of detail. I can think of no better expression to characterize these similarities than ‘family resemblances’; for the various resemblances between members of a family: build, features, colour of eyes, gait, temperament, etc. etc. overlap and criss-cross in the same way. – And I shall say: ‘games’ form a family.

If Wittgenstein is correct, the search for the one feature all and only games possess is a wild goose chase. It does not exist. But of course that does not entail that either there is, after all, no such thing as a game, or that what makes something a game must be some further mysterious characteristic we have yet to identify.

Perhaps we make the same kind of mistake if we assume that, if meaningful lives are possible, then there must be some one feature that all and only the meaningful lives share. Our inability to identify this feature amongst warp and weft of the Earthly features of our lives may then lead us mistakenly to conclude that either our lives lack meaning, or else the elusive meaning-giving feature must be other-worldly.

When we look at lives that are meaningful, and compare them with those that are not, we may find, not a single feature possessed by all of the former and none of the latter, but a great many factors that have an impact on meaningfulness, including some to which we have already alluded: a project freely-chosen, a project that is not deeply immoral, a project pursued with some dedication and skill, engagement in activities that help or enrich the lives of others, and so on. The impression that none of these worldly features are sufficient – that some further, magical, other-worldly ingredient is required if our lives are really to have meaning – may in part be a result of our failing properly to register that the concept of a meaningful life, like that of a game, is a family resemblance concept. Talk about ‘the’ meaning of life may be symptomatic of this confusion.

Is God required for a meaningful life?

While we might struggle to provide a watertight philosophical definition of what makes for a meaningful life, most of us tend to agree about which lives are meaningful and which are not. There's a broad consensus that, say, Marie Curie, Socrates, and Scott of the Antarctic led highly significant and meaningful lives, whereas a mindless follower-of-orders, or someone who has devoted their life entirely to torturing small animals, has not.

However, some Theists argue that, if there is no God, then no life is meaningful – not even the life of a Curie, Socrates or Scott. Let's look at three such arguments.

1. A moral argument

One simple line of argument that may tempt some is: a meaningful life is a morally virtuous life; but morality depends on God; thus there cannot be meaningful lives without God.

We have already looked at two reasons why this initial line of argument won't do.

First, the lives of many great artists, musicians, explorers and scientists have surely been highly meaningful, despite the fact that the individuals in question were not particularly moral. While moral lives can be meaningful, meaningful lives need not, it seems, be especially moral (though, as we have seen, it's arguable that their central projects must not be downright immoral). In which case, even if there were no such thing as morality, a meaningful life might still be possible.

Secondly, the above argument in any case just assumes that morality depends on God, a claim we have already seen is dubious.

2. The ultimate purpose argument

A second argument for the conclusion that meaningful lives require God focuses on ultimate ends or purposes. Surely, the argument runs, a life has meaning by virtue of its having some sort of final aim or goal. We must be here for some purpose. But only God can supply such a purpose.

Some religious people, for example, maintain that our ultimate purpose is to love and worship God. They suppose that without God there can be no such purpose, and with such a purpose, life is meaningless.

But is God required for us to have a purpose? It seems not. Each living organism has a purpose, to reproduce and pass on its genetic material to the next generation. We each exist for a purpose, a purpose supplied by nature, whether or not there is a God.

What this example also brings out, of course, is that merely having a purpose is not, by itself, sufficient to render a life meaningful. Discovering that nature has designed me for no other purpose than to pass on my genetic material hardly makes my life seem terribly significant. Indeed, my life is, on this measure, no more significant than that of a worm, which has the exact same purpose.

In reply, it may be said that I am overlooking a crucial difference between purposes: those for which we have evolved and those bestowed on us by some higher, designing intelligence. It is the latter, they may maintain, that render a life meaningful. But is this true? No. It is notoriously easy to construct counter-examples involving super-intelligent aliens. Here's one of my own devising.

Suppose humans have been bred on this planet for a reason – to wash the smelly underwear of a highly advanced alien race. The aliens will shortly return to pick us up and take us to their enormous alien laundry. Would this fact, or its discovery, fill our lives with meaning? Hardly.

Perhaps it will be conceded that merely being designed by some higher intelligence for a purpose is not enough to render our lives meaningful. The purpose must be one that we positively embrace and that makes us feel fulfilled. Washing alien undies fails on both counts.

But now suppose the aliens have designed us so that we discover we profoundly enjoy washing their underwear. In fact, once we start work in their laundry, we finally feel fulfilled in a way that we have never felt before. We rest each evening with an enormous sense of satisfaction that we are now doing what we were always meant to do. Would this make our lives meaningful? It's by no means obvious that it would (whatever we might happen to think).

In reply, it may be said that I am focussing on a silly purpose, certainly not the sort of purpose God has in mind for us. God made us for a particular purpose: to love him. It is this specific purpose that makes our lives meaningful.

But, again, this seems dubious. Suppose a woman wants to love someone who loves her unconditionally in return. It occurs to her that she could have a child for that purpose, and does so. Does the purpose for which this new person is created automatically bestow meaning upon their life? Not obviously. Some of us probably were conceived for such a purpose. Yet few would point to that fact in order to explain why their lives have meaning. I cannot see why God's creating me to love him would give my life any more meaning.

In fact, isn't creating human beings solely for some end a rather demeaning and degrading thing to do, as a rule? But then why is God's doing it any different? It is debatable whether, if there were a God of love, he would even want to create human beings for a particular purpose.

So the question of how our lives can have meaning is not, it seems, easily answered by appealing to divine purpose. In particular, the question of how our possessing a God-given purpose makes our lives meaningful has not, so far as I can see, been adequately explained. More often than not, we are offered, not a clear account of how God's existence makes our lives meaningful, but merely a promissory note that, in some mysterious and unfathomable way, it just does.

3. The divine judgement argument

Here's a third argument. It seems lives don't have meaning just because we judge that they do. Presumably, a life devoted solely to kicking other people in the shins at every available opportunity would not qualify as meaningful, even if we all thought it did.

But, the Theist might now add, if lives aren't meaningful simply because we judge them to be so, then they are meaningful only because God judges them to be so. So a meaningful life requires God after all.

This is a popular argument. Unfortunately, it runs into difficulties similar to those that face the parallel argument that if things aren't morally right or wrong because we judge them to be so, they must be right or wrong because God judges them to be so. The Euthyphro dilemma crops up here too. We can now ask:

Are lives meaningful because God judges them to be so, or does God judge them to be so because he recognizes that they are?

The first answer seems ridiculous. Surely, had God judged that kicking people in the shins at every available opportunity is what makes life meaningful, that wouldn't make it so. But the second answer – God merely recognizes what makes for a meaningful life – concedes that there are facts about what makes for a meaningful life that obtain anyway, whether or not God exists to make such judgements. But then these are facts to which humanists are just as entitled to help themselves as are Theists. God is redundant.

Does meaning require immortality?

We have not, as yet, found a good argument for supposing a meaningful life requires the existence of God. Let's now set such arguments to one side, and consider a slightly different claim: that, whether or not meaningful lives require God, they do at least require that we be immortal. How, Theists sometimes ask, can a life have any meaning or point if it ends in death? True, we may have achievements that outlive us, such as books written, buildings designed, and children well-raised. But those books will eventually be forgotten and those buildings will crumble. Our children will soon wither and die. Indeed, the human race as a whole will eventually disappear entirely without trace. But then, without immortality, isn't our existence all for nothing – a pointless waste of time?

It seems to me that, while a longer life might be desirable, it is not necessarily more meaningful. True, if you live longer, you may achieve more, do more good works, etc. But is a long life exhibiting such virtues thereby more meaningful than a shorter version? Presumably not. Nor is it obvious why extending such a life to infinity imbues it with any more meaning.

In fact, it is sometimes in the manner of our death that our lives acquire particular meaning and significance. Someone who deliberately sacrifices their own life to save others is often held up as an example of a person whose life is particularly meaningful. I might add that, if we compare the sacrifice of a religious person who lays down their life thinking they will be resurrected in heaven, and an atheist who lays down their life thinking death is the end of them, surely it is the latter individual who intends to make the greater sacrifice, and whose action is, for that reason, much more noble and meaningful.

Even when a life is not sacrificed for others, the manner of its end can often be what marks it out as particularly significant. We rightly admire those who face death with courage and dignity. Death is often an important episode of the story of our lives, an event that completes the narrative of a life in a satisfying and meaningful way. The fact that we die, and that death really is the end, does not make our lives meaningless. Indeed, the finality of death gives us an opportunity to make our lives rather more meaningful than they would otherwise be.

Religion vs. shallow, selfish individualism

Let's now turn to religious practice. Setting aside the issue of whether God exists, perhaps it might still be argued that religious reflection or observance is required if our lives are not to be shallow and meaningless. Here is one such argument.

It is sometimes claimed, with some justification, that religion encourages people to take a step back and reflect on the bigger questions. Even many non-religious people suppose that a life lived out in the absence of any such reflection is likely to be rather shallow. Contemporary Western society is obsessed with things that are, in truth, comparatively worthless: money, celebrity, material possessions, etc. Our day-to-day lives are out often lived out within a narrow envelope of essentially selfish concerns, with little or no time given to contemplating bigger questions. It was religious tradition and practice that provided the framework within which such questions were once addressed. With the loss of religion, we have inevitably slid into selfish, shallow individualism. If we want people to enjoy a more meaningful existence, we need to reinvigorate religious tradition and practice (some would add that we need, in particular, to ensure young people are properly immersed in such practices in school).

There is some truth in the above argument. Religion can encourage people to take a step back and contemplate the bigger issues. It can help break the hypnotic spell that a shallow, selfish individualistic culture can cast over young minds.

However, religion can itself also promote forms of selfishness – such as a self-interested obsession with achieving one's own salvation or personal enlightenment. And of course religion has itself been used to glorify material wealth, by suggesting that great wealth is actually a sign of God's favour.

Is it true that only religion encourages us to think about the big questions? No. There is another long tradition of thought running all the way back to the Ancient world that also addresses the big questions – a secular, philosophical tradition. If we want people, and especially children, to think about such questions, we are not obliged to take the religious route. We can encourage them to think philosophically.

Indeed, there is evidence that introducing philosophy programmes into the curriculum can have a dramatic impact on both the behaviour of pupils and the ethos and academic standing of their schools.

Most contemporary humanists are just as concerned about shallow, selfish individualism as are religious people. They too believe it is important we should sometimes take a step back and consider the big questions. They just deny that the only way to encourage a more responsible and reflective attitude to life is to encourage children to be more religious.

If we really want to encourage young people to think about the big questions, philosophy is, arguably, a much more promising approach. The Church of England poses the question ‘Is this it?’ on billboards and buses, promising those who sign up to their Alpha Course ‘An opportunity to explore the meaning of life’. However, when the religious raise such questions, they are often posed for rhetorical effect only. They are asked, not in the spirit of open, rational enquiry, but merely as the opening gambit in an attempt to sign up new recruits. Unlike religion, philosophy does not approach such questions having already committed itself to certain answers (though it does not rule out religious answers, of course). Philosophy really does encourage you to think, question and make your own judgement – an approach to answering the Big Questions that, in reality, many religions have traditionally been keen to suppress.

The claim that only religion encourages us to think about the big questions is not just false, it is rather ironic when made by religions with long and sometimes violent histories of curtailing independent thought.

Do humanists miss out on something?

It may be that we do miss out on something if we give up religion. Consider belief in Santa Claus. For the child who comes to believe in Santa, the universe appears wonderfully transformed. From within the perspective of their bubble of belief, the world, come December, takes on new meaning and significance – a rosy, magical glow. There is something it is like to inhabit this bubble of belief – to be a true believer in Santa – something its very hard to understand if you have never experienced it yourself.

When the child grows up a bit and the Santa bubble pops, it can be distressing for the child: the rosy glow vanishes leaving the world seeming rather sad and drab by comparison.

There's no doubt that popping the bubble of religious belief can be distressing for its occupant. The magic and meaning may appear to drain out of the world, leaving it seeming cold and barren. Isn't it better to live inside such a religious bubble if we can?

I don't believe so. If there is no God, then the magical glow the world seemed to take on when viewed from inside the bubble was always an illusion. When the bubble pops, the world might seem a little drabber for a while. But, personally, I would rather see the world as it is, than as I might like it to be.

In fact, isn't an appreciation of what is really important in life actually likely to be obscured by such a bubble? Compare belief in Santa, his workshop at the North Pole, the flying reindeer and so on. When that bubble pops, those colourful characters all vanish, but what was always most important come December 25th – love, getting together with our friends and family, and so on – are all still in place. In fact, for us grown ups, wouldn't belief in Santa – and the accompanying activities of posting letters to the North Pole, putting out the mince pie and milk – threaten to be a disabling distraction, preventing us from recognizing what truly matters?

I believe the same is true of belief in Gods, angels, demons, an after-life and so on. It is true that, without religious belief, we may miss out on something – e.g. on seeing the world as a divinely-ruled kingdom, on the comforting promise of being reunited with loved ones after our death. But we may gain rather more – including a more mature and clear-sighted view of what is really valuable and significant in life.

As the writer Douglas Adams once said: ‘Isn't it enough to see the garden is beautiful without having to believe there are fairies at the bottom of it?’

Humanism and the meaning of life

Some readers may be feeling short-changed. They may ask: ‘But what is the specifically humanist answer to the question: what makes for a meaning of life?’ The fact is that there is no official ‘humanist answer’.

The truth is that (with a few obvious exceptions, such as lives of religious piety) most humanists tend to agree with the religious about which lives are meaningful and which are not. Like most religious people, they agree that raising good children, pursuing intellectual enquiry with dedication, producing strikingly original and moving art, and so on are all ways in which we can enjoy a meaningful existence. Setting aside reference to the divine, humanists also apply much the same criteria in judging which are meaningful and which are not.

Humanists merely differ from some religious people in supposing (i) that those lives that we generally agree are meaningful are still meaningful even if there is no god or gods, and (ii) that belief in a god or gods can actually be an impediment to our living full and meaningful lives, by for example: leading us not to think about the big questions; forcing us to live a certain way out of fear divine punishment; or wasting our lives promoting false beliefs because of a mistaken expectation of a life to come.

From the humanist perspective it's what's before us – the rich warp and weft of our worldly, human lives – that really matters.

Adapted from my book published by CUP: Humanism: A Very Short Introduction.

October 10, 2024

Seeing the divine in the world: illusion or reality?

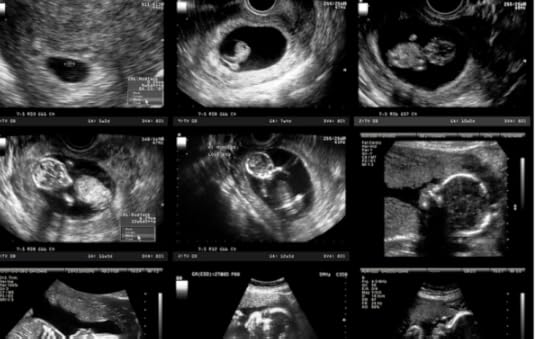

An ultrasound scan

An ultrasound scanSome religious folk believe that, perhaps with the right training and/or immersion in religious practice - some can become sensitive to meaning and significance in the world - meaning and significance that is lost on atheists. I look out the window and just see the sunset. They look out the window and see the Glory of God.But are they detecting meaning and significance that is really there for anyone with eyes to see? Or are they merely projecting that meaning and significance onto a realty that lacks it?

I suppose it boils down to something like the difference e.g. between 1. seeing the baby or the tumour in those shifting, fuzzy ultrasound scan images - something not everyone can do, and which requires training to get really good at it, and 2. seeing the canals of Mars.

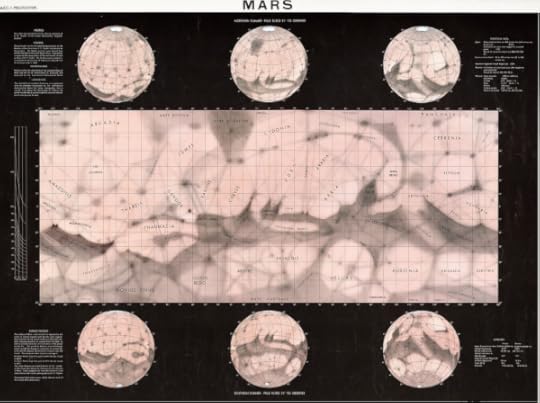

In the 1870s the astronomer Schiaparelli thought he could see the Martian canals through his telescope, and started to map them. Others joined in. They confirmed the existence of Schiaperelli's canals, and even noted that new ones had appeared. Then small black spots at the intersections of the canals were observed and recorded. Eventually, detailed maps of the canals were created and theories about them developed. Lowell famously theorised the canals were a planet-wide irrigation system designed to bring water down from the icy poles.Of course, the canals did not really exist.

My suspicion, of course, is that religious experience of the sort described above are more like the latter than the former. An interesting question is: how can we tell which of these things is going on: detecting real significance and meaning in what’s before us, or merely projecting that meaning and significance into what we see?

With ultrasound images we can at least check against something independent how well we are doing in reading the scans. I thought that was a hand, but it turns out it was a foot. We can now perform similar checks on the surface of Mars. But no such check is possible (I think?) when it comes to the veracity of the religious experience.

Notice that mere agreement among experts doesn’t count for that much, as we have that in the Martian canals example too. On the other hand, defenders of the veracity of such religious experiences may insist that just because there’s no objective independent check possible doesn’t mean what the religious seem to detect isn’t actually there.

Here’s Schiaperelli’s 1877 map, and then a 1962 map, of the canal systems of Mars (it wasn’t until 1965 Mariner fly-by that the canal theory was entirely debunked)

September 24, 2024

PHILOSOPHERS ON GOD: The Evil God Challenge

Jack Symes interviews me on The Evil God Challenge for his book Philosophers on God. Also included Richard Dawkins, Dan Dennett, Richard Swinburne, Yugin Nagasawa, and William Lane Craig. Prepublication draft.

Chapter Eight

The Evil-god Challenge

Stephen Law

Introduction

The problem of evil is perhaps the most powerful argument against classical monotheism. However, as Nagasawa pointed out in our previous chapter, religious believers claim to have an infinite number of resources at their disposal; resources which, they say, can be used to explain why God allows evil to exist. A lot of ink has been spilt on whether these explanations are successful. It’s a complex and contentious debate, which rarely leads to opponents changing their minds. Perhaps, if we want to break the deadlock between theists and atheists, we need to reframe the discussion?

In 2010, Stephen Law released a paper that would do just that. Today, Law’s article – ‘The evil-god challenge’ – is among the most downloaded and discussed papers in philosophy of religion of the past decade. Law’s work – through books, videos, podcasts and live events – has a global audience in the millions and has attracted the attention of some of the world’s most notable religious philosophers.

The evil-god challenge can be stated as follows: why is believing in a good god significantly more reasonable than believing in an evil god? Fundamentally, this question depends on the truth of what Law calls ‘the symmetry thesis’, which states that the two beliefs (belief in good god or evil god) are roughly as reasonable. To answer the challenge, religious believers need to explain why belief in a good-god is significantly more reasonable than belief in its malevolent counterpart. If they can’t do this, says Law, then traditional theism is scarcely more reasonable than belief in an evil god, which is, surely, absurd.

The challenge

One of your arguments against god’s existence, ‘the evil-god challenge’, has received enormous attention. Who is this ‘evil god’, and how are they a challenge to theism?

According to Christians, Jews and Muslims, there exists one god who is all-powerful, all-knowing and maximally good. Religious believers give lots of reasons for thinking that this god – let’s call them ‘good god’ – exists. For example, some argue that the universe’s existence and finely tuned character point towards a supremely intelligent creator. Let’s say, just for a moment, that their arguments have some credibility. (I don’t think they do, but suppose do.) Now, I want you to consider an alternative hypothesis. Imagine a similar god who differs in one crucial respect: rather than being maximally good, this being is maximally evil. That’s what I mean by ‘evil god’. The first thing to notice is that many of the arguments used to support a good god – such as the universe’s existence and fine-tuned character – can also be used to support an evil god. In fact, I think that once we consider all of the arguments and evidence at our disposal, we’ll find that the likelihood of both hypotheses (good god and evil god) is fairly similar. In other words, I think there’s a rough symmetry between the two hypotheses. I call this the ‘symmetry thesis’.

Now, here’s the problem. The evil-god hypothesis is obviously ridiculous. If a grown-up told you they believed in an evil god, you might question their sanity. However, according to the symmetry thesis, believing in good god is no more reasonable than believing in evil god. So, if the good-god hypothesis is roughly as reasonable as the evil-god hypothesis – and believing in an evil god is absurd – then we ought to think that believing in a good god is absurd as well. For the Abrahamic believer, the only way to avoid this conclusion is to answer the challenge. The challenge is, in essence, to explain why the symmetry thesis is false: what makes believing in good god significantly more reasonable than believing in evil god?

Why does one hypothesis need to be ‘significantly’ more reasonable?

If one is downright ludicrous, then pointing out that the other one is slightly more reasonable is hardly good enough. Maybe believing that fairies are at the bottom of your garden is somewhat more reasonable than believing Santa delivers your presents on Christmas Day. The minor difference doesn’t matter; both are absurd beliefs. That’s why the theist needs a reason to suppose the good-god hypothesis is significantly more reasonable.

Could they achieve this by appealing to goods within the universe? Might they not point out that the world is not nearly evil enough to be the creation of such a malevolent deity?

This response, which I call the ‘problem of good’, says that we can reasonably rule out the existence of evil god because the world contains a very significant amount of good. After all, surely an evil god would not create a world with so much laughter and love, rainbows and contentment? And why does evil god allow us to help each other and to reduce the suffering of others? I accept that the problem of good is a strong enough reason to reject the evil-god hypothesis. Don’t forget, however, that the world also contains a very significant amount of evil. This parallel argument, the notorious ‘problem of evil’, is just as big of a problem for the theist. ‘Why,’ asks the evil-god challenger, ‘would good god create a world that contains so much pain and misery?’ Consider all of the terrible things that we do to each other – murders, genocides, torture, cruelty, exploitation – and then there’s all of the natural diseases, disasters, and millions of years of animal suffering. For example, for almost the entire sweep of human history, your chances of making it to adulthood were little better than fifty-fifty. Many of those child deaths would have been slow and horrific. And then there’s the psychological suffering of the parents. Ask any parent, ‘What’s the worst thing that could happen to you?’ They’ll probably tell you it’d be watching their child die a slow and unpleasant death. If we can reasonably rule out the evil-god hypothesis because of the problem of good, and I think we can, then why can’t we rule out the good-god hypothesis because of the problem of evil?

Theists have been responding to the problem of evil for centuries. Can’t they overcome the challenge by appealing to theodicies and defences?

Yes, the good-god defender might appeal to theodicies and defences, but so can the evil-god challenger. Let’s take an example. One of the most popular responses to the problem of evil is the free-will defence. According to this argument, good god allows for evil to allow for the greater good of free will. If good god had created human beings as puppets who always did the right thing, then we wouldn’t be morally responsible for our actions. Therefore, good god cut our strings and set us free. Sometimes we do the wrong thing, but if we weren’t free, then good god would miss out on the tremendous good that is the human capacity to engage in genuinely virtuous actions.

The problem with this kind of response is that appears to work more or less equally effectively in defence of an evil god. Answering the problem of good, the challenger can argue that evil god allows some people to be virtuous, but that’s the price evil god pays for free will and genuinely malevolent actions. Evil god could have created us as puppets who always did wrong, but then we wouldn’t be responsible for our actions. Therefore, to get the very worst kinds of evil – like freely chosen genocide and slavery – he cut our strings and set us free. Unfortunately, some of us then behave virtuously. That’s the price evil god pays to allow for such horrendous moral depravity.

What about explanations of natural evils? The soul-making theodicy, for example, claims that evils that aren’t caused by humans – from hay fever to hurricanes – allow us to develop our characters. Can the challenger mirror this response?

I think they can. First, let’s be clear on what the soul-making theodicy is supposed to show. As you say, according to theists, some of the evils in the universe allow us to develop our characters. Evil can help us grow and become better people. Call it a ‘vale of soul-making’. As a parent, I taught my daughter to ride her bike. She didn’t enjoy falling off and grazing her knees – children spill a lot of blood and tears when they’re learning to ride a bike – but I encouraged her to keep trying. Why did I do that? Because that’s how she’ll grow as a person. She ought to learn the skill of riding a bike; she should learn how to overcome hardships and she’d benefit from the sense of achievement. According to the theist, the same is true for many of the evils in the natural world: the suffering that we go through in this life brings us closer to perfection. They give us opportunities. No pain, no gain.

But now notice that, with some minor adjustments, the challenger can use this same theodicy in response to the problem of good. ‘Why,’ asks the theist, ‘does evil god give us healthy young bodies that can ride bikes?’ So he can take them away with age, of course. It’s cruel to give something wonderful and then take it away – like giving a child a wonderful toy and then smashing it up in front of them. That makes them more miserable than if they never had the toy. The same is true of our friends, children and all of our accomplishments. ‘Why,’ asks the theist, ‘did evil god give us children to love and to cherish?’ Because it’s only if we love our kids that we’ll suffer torment when he kills them on an industrial scale, as he has for hundreds of thousands of years. If we are indifferent, we’ll just say ‘meh’. Love is required for the most appalling forms of psychological torment. This is not a vale of soul-making but a vale of soul-destruction.

So what are these reverse-theodicies supposed to show?

I’m trying to get the penny to drop. If you’ve spent a long time engaged in a certain kind of intellectual activity that’s pretty flaky – but everyone around you is doing it, and everyone’s telling you that it’s pretty effective – then it can be hard to see that there’s something suspect about the way you’re thinking. The evil-god challenge is, in part, a way of getting theists to step outside of their skin and see what they’re doing from a different perspective. Most of us can see immediately that, notwithstanding such ingenious mirror moves that might be used to defend belief in an evil god against the problem of good, it remains pretty obvious, given observed goods, that there’s no evil god. Most theists would remain entirely unconvinced – would see through the charade - if somebody used such mirror theodicies to defend their belief in evil god. I’m asking them a question: why is what you’re doing any better?

Breaking the symmetry

There are some theodicies that don’t have obvious parallels. For example, Saint Augustine thought that evil entered the world when Adam and Eve committed the original sin and, therefore, good god isn’t responsible for the world’s evils. It’s difficult to imagine what a reverse-original sin would even look like. Does this difference, this asymmetry, offer a possible solution to the challenge?

It doesn’t solve my version of the challenge, though it might be a problem for earlier versions. One of the earliest evil-god challenges appeared in Edward Madden and Peter Hare’s book, Evil and the Concept of God. For Madden and Hare, the problems of good and evil were ‘completely isomorphic’. In the 1970s, Stephen Cahn defended a similar view and, in the 1990s, Edward Stein and Christopher New came to the same conclusion. I disagree. Original sin is just one example of an explanation that doesn’t have an obvious parallel. Remember, however, that I claimed that there’s a ‘rough symmetry’ between the reasonableness of both hypotheses. This is different to what the earlier challengers thought. In assessing the reasonableness of each hypothesis we should look at all the available evidence and explanations for it. True, some defences of a good god might be less effective than defences of an evil god, and vice verse. Original sin is an example; there is no obvious parallel theodicy. However, it’s one of the least plausible theodicies. There was no Adam or Eve, and we now know unimaginably vast quantities of pain and suffering stretch back millions of years before human ever lived or sinned. So yes there’s an asymmetry here – this theodicy doesn’t flip - but that doesn’t change the overall balance of reasonableness much.

Are there any asymmetries that favour evil god over good god?

In think so. One candidate is the argument from religious experience – miracles, revelations and the like. Now you might think that miracles and religious experiences are clearly evidence for a good god and against an evil god. A good god will want to cure us, alleviate suffering, and reveal himself to us. An evil god wouldn’t miraculously cure people. So here is evidence that tips the balance in favour of a good god. However, on closer examination, maybe this evidence actually better supports an evil god. The fact that the world’s religions and denominations are so varied in their beliefs seems to be a bigger problem for the theist than it does for the challenger. If I were an evil god, I’d might well maximise evil by engaging in deception. I might dress up in a white outfit, throw on a halo and appear in the religious experiences of one group. I’d also perform some genuine miracles (which, being a god, I can do). Perhaps I’ll tell them that Christianity is the one true religion and raise Jesus from the dead. Then, I would go to another group – still dressed in my good god garb – and tell them things that contradict my messages to the first. Perhaps I’d perform miracles but also reveal that Jesus was not raised from the dead. Now each of these groups believes – because of the genuine miracles and so on - they have the one true god on their side, and that’s a recipe for of deep and bloody conflict! An evil god would be delighted with that result. He might even engineer it. A good god, on the other hand, would surely never reveal himself in such a misleading way, or allow such confusion to reign because of contradictory revelatory experiences, miracles, teaching, and so on. The question that we should ask is: which of our two hypotheses is a better fit for the evidence – that a good god is responsible for these things, or that an evil god is?. The distribution of religious miracles, experiences, and scriptures looks like it offers more support to an evil god than good god.

I wonder if it’s even possible for a maximally perfect being to be evil rather than good?

There might be a logical problem with the idea of an evil god, just as some atheists think there’s a logical problem with the idea of a good god. Critics have argued for a long time that god’s various attributes can’t be combined, or that individual attributes – such as god’s omnipotence – generate contrdictions. It may be that you can present similar objections against an evil god too. Perhaps better logical objections to an evil god. However, even if you could establish a logical problem when it comes to the idea of an evil god, we can still run the evil-god challenge. My argument is this: if you can reasonably reject evil god because of the problem of good, and I think you can, then why can’t you reasonably reject belief in good god because of the problem of evil? To point out that there are further, logical problems with the idea of an evil god not mirrored by problems for a good god is to miss the point. The evil-god challenge can still be used in this way, even if it turned out that the idea of an evil god is logically incoherent.

Perhaps the theist could claim that the world contains significantly more good than evil. If this is true, some might say, then the problem of good would rule out the evil-god hypothesis; however, the problem of evil wouldn’t rule out the good-god hypothesis. Is this a better response?

I don’t think so. First, is there significantly more good than evil? It’s very hard to quantify good and evil. I wouldn’t be confident about the assessment that there’s a lot more good than evil, or vice verse. And remember, a mainstream Christian view is that the world is absolutely saturated in evil – in particular, every single human being is so morally depraved as to deserve everlasting torment. And, as anyone that’s watched a few nature documentaries will know, for many of the world’s sentient inhabitants, life involves quite extraordinary amounts of suffering. Nature is cruel beyond our imagining. Secondly, even if it’s true that there is significantly more good than evil, which I doubt, there can still be more than enough of each reasonably to rule out both god hypotheses. Compare: perhaps there’s ten times as much evidence against Santa than there is against fairies. Clearly, there can still be more than enough evidence to rule out both. Most theists acknowledge that the problem of evil really is a very significant problem precisely because there’s so much of it. They acknowledge that, prima facie at least – it’s hard to see how there could be a good god-justifying reason for every last ounce of it. And if there’s any pointless evil – even a teaspoonful - then there’s no good god. Ditto pointless good of course: an evil god won’t permit any pointless goods – good’s for which there’s a more than adequate evil justification. So, even if there is a significant asymmetry in terms of the amount of good and evil that exists, that needn’t alter the fact that both hypotheses can reasonably be ruled on the basis of the distribution of observed good and evil.

What about the suggestion made by skeptical theists – that we are in non position to know whether any evils are pointless. Sure there is pain, suffering, and moral depravity. And it may be that we can’t think of a good-god-justifying reason for that evil. But just because we can’t think of such a reason doesn’t mean a reason doesn’t exist. We are mere humans, with limited intellectual abilities. Just as I shouldn’t expect to be able to see an insect half a mile away, given my perceptual abilities, so I shouldn’t expect to be able to think of all the reasons a good god might have to allow the evils we observe. But now the problem of evil collapses. Fot all we know, all evils are justified. Does this move tip the balance of reasonableness strongly in favour of a good god?

No. For the exact same reasoning applies to an evil god. Perhaps there are evil reasons for the goods we observe, but we just can’t think of them. Skeptical theism works just as well in defence of an evil god as it does in defence of a good god. But in any case, I argue that skeptical theism is untenable. It generates other skepticisms that the theist is unlikely to accept. For example, if skeptical theism is true, then for all I know there’s a good reason for a good god to deceive me about the existence of the external world and the past. I can’t reasonably assign a low probability to there being such reasons. But then I can’t reasonably trust my senses or my memory. For all I know I am being deceived. In short, skeptical theism opens a skeptical Pandora’s box, with the skepticism spreading out in ways the theist is unlikely to want to accept.

William Lane Craig offered an interesting response to your evil-god challenge. Craig thinks that your argument misses the point. Christians don’t believe in god’s goodness because of the goods they find in the world, he claimed, but because ‘being good’ is what it means to be ‘God’.

I think Craig has missed the point. I don’t assume Christians make their case for a good god based on observation of the world around them. Sure, the religious may sing songs about how everything’s bright and beautiful, but most don’t typically infer god’s goodness from observed goods in the world. I hope it’s clear that my point is not that Christians can’t reasonably support belief in a good god based on such observed goods. Rather, it is that if we can reasonably reject belief in an evil god based on observed goods, and I think we can, then why can’t we can reasonably reject belief in a good god based on observed evils? Surely we can. So Craig seems to have misunderstood this challenge. Why can’t we reasonably rule out both hypotheses based on observation of the world around us?

Well, let’s consider another of Craig’s responses. To run the evil-god challenge, you need to appeal to objective moral values. However, objective moral values, says Craig, can’t exist unless there’s a god. Therefore, your challenge proves the very thing you set out to disprove!

There are lots of Christian apologist internet videos and posts making this same point: atheists can’t use the problem of evil, because they don’t believe in evil! Good and evil only exist if good god exists. So if I admit evil exists, I admit god exists. Of course this objection relies on the thought that moral good and evil can’t exist in the absence of god, which is highly dubious; even some theists deny that. But in any case, this response to the problem rests on misunderstanding. To run the problem of evil, atheists don’t need to believe in evil. The point is that the problem of evil is an internal problem for theism. If a Christian thinks that pointless (i.e. good-god-unjustified) suffering is an evil, and they do then, then given the existence of much pointless suffering, they have a big problem. I can point out this problem even if I’m not myself committed to the existence of good, evil, and/or god. Atheists don’t need to believe in good and evil in order to run the problem of evil.

There is another response to the evil god challenge worth mentioning. What if we could come up with an argument for a good god – a really powerful argument – that was not mirrored by a good argument for an evil god? Of course, given what appears to be such compelling evidence against both an evil god and a good god, that argument is going to have to be very strong. I mean, in order to make it reasonable to believe in an evil god, given the problem of good, any argument for an evil god is going to have to be really strong. Ditto any argument for a good god that is capable of outweighing the problem of evil. It’s going to need to be a knock-out argument.

The trouble is, there are no such arguments. Most of the most popular and intuitively appealing arguments for god aren’t even arguments for a good god. They are merely arguments for a first cause, necessary being, prime mover, or intelligent designer. These arguments, as such, provide no clue as the moral attributes, if any, of the thing they’re arguing for. Considered in isolation, these arguments provide as much support for an evil god as they do for a good god. They do nothing to show that belief in a good god is significantly more reasonable than belief in an evil god.

Having said that, there are of course some arguments specifically for a good god. However, they are among the weakest arguments for god’s existence. For example, the moral argument for a good god, which Craig favours, is notoriously flimsy, with even Christian Philosophers like Richard Swinburne rejecting it (though I know the argument plays well to lay audiences). Other arguments for a good god – e.g. a maximally great being, which must then include perfection, including moral perfection – tend to be pretty abstract and slippery. Again, theists disagree even amongst themselves about whether such arguments are any good – which suggests they’re really not that compelling. Further, even some of the arguments specifically for a good god can be mirrored, like this flipped ontological argument:

I can conceive of a maximally evil being.

It is more evil for such a being to exist in reality than in my imagination.

Therefore a maximally evil being exists.

And as the evil such a being is capable of increases with its power, this maximally evil being must also be maximally powerful.

So, in summary, and on balance, the case for a good god looks at best pretty flimsy, and certainly not nearly strong enough to outweigh the problem of evil.

The ghost of god

There are religious believers who argue that it’s reasonable to believe in good god without evidence or argument. One such proponent, Alvin Plantinga, suggests we can come to know that god exists through a god-given sense, the sensus divinitatis. This provides direct, non-inferential knowledge of good god’s existence. Might this be a way of unlocking the evil-god challenge?

In order to illustrate Plantinga’s thinking, let’s consider an example. Imagine that you’re observing an apple in a bowl. It very much seems to you that there’s an apple there – that you can see it, feel it, smell it, and taste it. Suppose that somethere in the bowl. Here’s compelling evidence that there’s a global shortage of apples, with none in the UK!’ You would think their argument was ridiculous; you can just see there’s an apple in the bowl! It can be reasonable for you to believe despite the evidence to the contrary, given it just very much seems to you that there’s an apple there and you’ve no reason to believe your senses aren’t to be trusted on this occassion. That’s Plantinga’s view. But then the religious person can insist that it can be reasonable for them to believe in the existence of a good god, given that’s very much how things seem to them, and even if there’s strong evidence that there’s no such god (such as a lot of apparently gratuitous evil).

Is this an effective way of meeting the evil god challenge? Can direct religious experience trump the problem of evil?

I think there are excellent grounds for being sceptical about such religious experiences. What would you think if I told you that, right now, my dead auntie was here in the room with us?

It depends on whether she’s a corpse or a ghost.

She’s a ghost.

I’d be relieved that she wasn’t a corpse… but I’d still think you were crazy.

Exactly. It might really seem to me that my dead auntie is in the room with us, but, given other background information, it still isn’t reasonable for me to believe it. Psychologists have pointed out that we human beings are horribly prone to false positive beliefs about extraordinary hidden agents. People believe in all sorts of thing - including goblins, ghosts, nature spirits, fairies, angels, and miraculous appearances of the Virgin Mary - on the basis of subjective experience and testimony. We know that very many of these beliefs are false. Indeed, they are constantly being debunked (take out a subscription to Skeptical Inquirer magazine for numerous examples). We are notoriously prone to such false positive beliefs – thinking that there are extraordinary beings there when there aren’t. Psychological theories are now being developed to explain this striking tendency we have to over-detect agency. Given this well-established tendency to think we are experiencing extraordinary hidden agency when we’re not, it is not reasonable to trust our own experiences, or the experiences of others. And this obviously extends to experiences of gods, including good god. There’s huge amount of evidence against the existence of such a deity - the problem of evil. Plus we have very good reason to distrust such experiences given we’re so prone to false positive beliefs based on them. Yes it’s reasonable to believe there’s an apple in the bowl if that’s very much how it seems to me, notwithstanding the evidence that there are no apples in the country. But it’s no longer reasonable to trust appearance once I have grounds for thinking I may well be hallucinating, or being deceived by a hologram, or am in an environment where people regularly falsely report seeing apples. Under those circumstances I have what philosophers call an undercutting defeater for my belief. My belief there’s an apple there could still be true, but it’s no longer reasonable for me to hold that belief given this additional information. For much the same reason, then, it’s no longer reasonable to trust god experiences once we know they are a variety of experience notoriously prone to producing false positive beliefs.

But still, can’t we explain a great deal by appealing to god – explain many things that are otherwise deeply mysterious? Doesn’t this count heavily in theism’s favour?

I suspect this takes us close to the heart of the debate between atheists and theists. There’s no doubt that if you posit an invisible being with supernatural powers, you can explain all sorts of things. And, when somebody points out evidence against your belief in such beings, you can always explain away that evidence, given sufficient ingenuity. Nine times out of ten, that’s the theist’s strategy: explain away the evidence and keep hammering away at the mysteries. Funnily enough, that’s exactly how all sorts of conspiracy theories work. They employ those same basic strategies. The same goes for belief in extraordinary supernatural beings such as fairies or gremlins. ‘I can’t find my keys! I thought I put them on the mantelpiece, but now they’re here on the sofa.’ Can you explain that? No you can’t. It really is quite mysterious! But if I say that gremlins moved your keys – mischievous invisible creatures with supernatural powers – then I can explain what you can’t. Once I introduce an extraordinary hidden agent, I can explain anything I want. And if you argue that there can’t be any gremlins because we never see them, etc. I can, with a little ingenuity, always cook up ways to explain that evidence away. We never see the gremlins because they’re invisible, or are just really, really good at hiding. And so on.

Rather than engaging in such make-believe, I think right thing to do is just honestly admit we don’t know the answers to all of these questions. I don’t know how my keys ended up on the mantelpiece. Yes, gremlins would explain how they got there, but that doesn’t give me much reason to believe in gremlins. Similarly, I don’t know why the universe exists and I don’t know how consciousness arises. But still, it’s clear that I can quite reasonably rule out the suggestion that an evil god created the universe and conscious beings in order to torture them. And if I can do that, then why can’t I rule out a good god on much the same basis? Surely I can. We may not know the answers to various deep philosophical questions, but that doesn’t prevent us quite reasonably ruling out certain answers.

Afterthoughts

In my experience, the evil-god challenge never fails to inspire a passionate conversation. Whether it be a friend at a party or a professor at a conference, the idea of an evil god – and a new lens through which to explore the question of God’s existence – seems to capture people’s imaginations. Philosophically, the challenge’s greatest asset is its simplicity. Rather than launching a head-on attack, the challenger points to analogous belief that is clearly silly: ‘Look how silly that belief is,’ says Stephen, about belief in an evil god. And of course you recognise that it really is silly. But then he adds: ‘So now explain why your belief is significantly more reasonable.’

In the wider literature, the evil-god challenge is treated as if it can be used to respond to every argument for God. I don’t think that’s right. For example, theists have many reasons for thinking that god is good rather than evil. As Hill explained in our opening chapter, for example, the concept of God – namely, the greatest conceivable being – would possess every great-making property that it’s possible to have. As moral goodness enhances greatness, but moral wickedness detracts from greatness, theists seem justified in attributing goodness (and not evil) to the greatest conceivable being. As we saw in his response to Craig, Law doesn’t think this rebuttal applies to his version of the challenge. This is worth considering too. Law’s version of the challenge rests on the claim that theists believe that evil god is absurd because of the problem of good. I wonder, however, whether this is something that theists actually believe. Do religious believers reject the evil-god hypothesis because the world contains so much good? If that is not their reason, then perhaps they can free themselves from the clutches of the challenge.

Questions to consider

1. Could an evil god have created the world?

2. How strong is the symmetry between the problem of good and the problem of evil?

3. Are religious experiences better evidence for good god or evil god?

4. When, if ever, is it reasonable to believe in invisible beings with supernatural powers?

5. Is the good-god hypothesis more reasonable than the evil-god hypothesis?

Recommended reading

Advanced

John Collins, ‘The evil-god challenge: extended and defended’, Religious Studies, vol. 55 (1) (2019): 85–109.

Collins’s paper develops further symmetries between the good-god hypothesis and evil-god hypothesis. He also addresses those who have responded to Law’s challenge, maintaining that each fails to overcome the symmetry thesis.

Christopher Weaver, ‘Evilism, Moral Rationalism and Reasons Internalism’, International Journal for Philosophy of Religion, vol. 77 (1) (2015): 3–24.

There are so many of papers responding to the evil-god challenge; this is one of the best. Weaver argues that, following certain meta-ethical assumptions, it would be impossible for an evil god to exist.

Intermediate

Stephen Law, ‘The evil-god challenge’, Religious Studies, vol. 46 (3) (2010): 353–73.

This is Stephen’s landmark paper on the evil-god challenge: he introduces the challenge, compares it to previous versions and addresses a series of responses. If you enjoyed this chapter, this is a must-read.

Stephen Law, Believing Bullshit: How Not to Get Sucked into an Intellectual Black Hole (New York: Prometheus Books, 2011).

In this short and accessible book, Stephen exposes fallacious ways of thinking and how we can respond to them. Law’s focus isn’t just religion but the techniques used by a range of dangerous belief systems. If you’re looking to develop your critical thinking skills, then this is definitely worth a read.

Beginner

Asha Lancaster-Thomas, ‘The Evil-god Challenge Part I: History and Recent Developments’, Philosophy Compass, vol. 13 (7) (2018): 1–8.

For those looking to engage with the wider evil-god literature, this is a great place to start. Lancaster-Thomas discusses the history of the challenge, its nature – including a synopsis of the different types of evil-god challenges – and several arguments to which the challenge can be applied.

Asha Lancaster-Thomas, ‘The Evil-God Challenge Part II: Objections and Responses’, Philosophy Compass, vol. 13 (8) (2018): 1–10.

This is the follow-up piece to the previous recommendation, in which Lancaster-Thomas gives an overview of different responses to the challenge. Lancaster-Thomas also discusses the strengths of the challenge and its implications for theism more generally.

Notes & Sources

Saint Augustine, Confessions, trans. Henry Chadwick (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 31.

Edward Madden and Peter Hare, Evil and the Concept of God (Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas, 1968), 32–4.

Ibid., 34.

Steven Cahn, ‘Cacodaemony’, Analysis, vol. 37 (2) (1977): 69–73.

Christopher New, ‘Antitheism: A Reflection’, Ratio, vol. 6 (1) (1993): 36–43.

See Asha Lancaster-Thomas, ‘The Evil-God Challenge Part II: Objections and Responses’, Philosophy Compass, vol. 13 (8) (2018): 1–10.

March 4, 2024

Cult of MAGA: The Crisis, The System, and The Enemy

This is a pre-publication draft of a piece that appeared under a lightly different title in a recent Byline Times supplement on Trump, available here.

In The Art of The Deal, Trump claimed that the decorative tiles in the children's room at his Mar-a-Lago resort were made by Walt Disney personally. When Trump's butler asked him if that was really true, Trump replied, “Who cares?”

Trump is a bullshitter. Harry Frankfurt’s little classic On Bullshit points out that the liar and the honest person have at least something positive in common: a focus on the truth. The honest person says what they believe is true; the liar what they believe isn’t true. But bullshitter, says Frankfurt,

…is neither on the side of the true nor on the side of the false. His eye is not on the facts at all, as the eyes of the honest man and of the liar are, except insofar as they may be pertinent to his interest in getting away with what he says. He does not care whether the things he says describe reality correctly. He just picks them out, or makes them up, to suit his purpose.

It's said we live in a ‘post-truth’ culture, and bullshit, in Frankfurt’s sense, is a part of that culture. Many accuse Trump of being a master of bullshit, casually firing off statements to self-aggrandise or manipulate uninterested in whether or not they’re true.

While Frankfurt’s characterisation of bullshit is intriguing, I think it’s too narrow. A lot of what rightly gets called bullshit is propagated by folk who do care about truth. For the most part, believers in astrology, demons, guardian angels, or spiritualist communication aim to aim to believe what’s true. To suggest that anti-vaxxer or Christian Science parents (who forego orthodox medical treatment in favour of prayer) don’t care about whether their belief is true seems absurd given they’re prepared to bet their child’s life on it.

So what about the Make America Great Again movement backing Trump? While Trump often seems uninterested in what’s true, I think his followers, for the most part, do care about truth. Yet I still consider the MAGA movement a kind of bullshit movement, alongside wacky conspiracy theories and religious cults. In order to understand why it’s a bullshit movement, we’ll need a more encompassing conception of bullshit than Frankfurt’s.

In my book Believing Bullshit, How Not To Get Sucked Into an Intellectual Black Hole, I outline eight key warning signs that we’re imprisoned in a bullshit belief system. There’s no single common denominator when it comes to bullshit: different belief systems tick different boxes. But before get into why MAGA is a bullshit movement, I want briefly to explore why our current political landscape provides such fertile soil for bullshit political movements to take root. I’ll focus on two key reasons, which I call The Crisis and The System.

A crisis makes us more susceptible to bullshit. Medical crises, for example, make many of us vulnerable to quacks and charlatans offering miracle cures. Bereavement can have the same effect. Parents who have lost a child may be drawn to spiritualists who reassure them that not only is their child not gone, they can even be communicated with.

MAGA also exploits a crisis. In both the US and UK, there is a growing sense of deepening economic crisis. Many feel it personally and acutely. The cost of rent and food is spiralling, wages are stagnating, job insecurity is increasing, and many neighbourhoods are in visible decline. Owning your own is becoming impossible for most. This, too, is a crisis that can make us easy prey for charlatans. The more desperate we feel, the more vulnerable we become.

Alongside The Crisis is what I might call The System. Many bullshit belief systems exploit individuals’ sense and fear that a secretive elite controls everything. Conspiracy theorists foster and feed off these feelings, encouraging us to believe the Illuminati or the Jews control everything, or that 9/11 was an inside job, or that Area 51 holds dead aliens, or the Moon landings were faked.

MAGA also invokes The System. Many ordinary citizens, both inside and outside MAGA, feel increasingly powerless and “left behind”. “They’re all the same”, is a common refrain. There is a suspicion that while those in control might pretend that we all have a choice and can exert influence through the ballot box, the truth is that real power has been stitched up. Behind the façade of democracy, a corrupt and entirely self-interested political and economic oligarchy, is really in control. Some call it the ‘deep state’.

The Crisis and The System combine to suggest that our economic woes are a result of a rather secretive and corrupt elite who act always in the own narrow interests at the expense of everyone else. This creates particularly fertile soil for a bullshit political movement to take root. If The Crisis is a product of The System, then solving The Crisis requires we take a sledgehammer to The System. And that is exactly what Trump and the MAGA movement promises to do. They promise to ‘drain the swamp’.

MAGA feeds on the widespread perception of The Crisis and The System. But is that what makes it a bullshit movement? Actually, no. There really is a severe economic crisis hurting increasing numbers of ordinary Americans. And it’s at least arguable that this crisis is in large part a product of a political system that really is increasingly corrupt, offering less and less real choice, and presided over by an economic and corporate elite. So perhaps the MAGA movement is right about something: the Crisis is real, and the cure really will require taking a sledgehammer to The System. In order significantly to improve the lives of ordinary Americans, we need to step outside of the fairly narrow parameters of the Overton window of ‘acceptable’ political opinion and do something comparatively radical.

So if the MAGA movement might actually be correct about both The Crisis and The System, what makes it a bullshit movement? I think the answer lies in its identification of what I’ll call The Enemy: those who supposedly control The System and are responsible for The Crisis.

Who is The Enemy, according to MAGA? It comprises the ‘woke mob’, cancel culture, immigrants, Hispanics, Black Lives Matter, the left, and those who wish to rob Americans of their freedom to own automatic weapons and refuse to bake a gay couple a wedding cake. The truth, of course, is that none of these groups are responsible for the economic crisis hurting ordinary Americans. Those chanting “Build the Wall!” and yelling slogans about BLM, Muslims, or the Woke are calling for things that will do little if anything to bring back jobs or reduce the cost of living.

If there is a veiled elite responsible for their declining living standards and decimated high streets, it’s not comprised of these folk.