Scott D. Anthony's Blog

August 7, 2015

June 10, 2015

February 27, 2015

September 17, 2014

The Chief Innovation Officer’s 100-Day Plan

Congratulations! Your energy and track record of successfully launching high-impact initiatives scored you a plum role heading up innovation. Expectations are high, but some skeptics in the organization feel that innovation is an overhyped buzzword that doesn’t justify being a separate function. So, what can you do in your first 100 days to set things off on the right track?

Over the past decade we’ve helped dozens of leaders through their first 100 days. Based on our experience, augmented by in-depth interviews with a few of the most seasoned practitioners with which we have worked, we suggest that innovation leaders put the following five items on their 100-day punch list.

Spend quality time with every member of the executive committee. This should go without saying, but it’s vitally important to develop relationships with the CEO, business unit leaders, and other key executives to understand the company’s strategy, so that the innovation approach and projects you pursue align with overall corporate goals. Brad Gambill, who over the past few years has played a leading role in strategy and innovation at LGE, SingTel, and TE Connectivity, believes the first 100 days are an ideal time to “ask dumb questions and master the basics of the business.” He particularly suggests focusing on the things “everyone else takes for granted and thinks are obvious but aren’t quite so obvious to people coming in from the outside.” So don’t be afraid to ask why a decision-making meeting ran the way it did or challenge the wisdom of pursuing a certain strategy or project.

It is particularly important to understand these executives’ views of two things – innovation’s role in helping the company achieve its growth goals and your role in leading innovation. Is innovation intended to improve and expand the existing business, or is it meant to redefine the company itself and the industry in which it operates? Do executives expect you to establish and incubate a growth businesses, act as a coach to existing teams, or focus on establishing a culture of innovation so that new ideas emerge organically?

As you invest time with top executives, you should begin to understand the organizational relationship between your innovation work and the current business. Are leaders willing to give up some of their human and financial resources to advance innovation? Are you expected to recruit a separate team from within and beyond the company? Or are you expected to spin straw into gold by working without dedicated resources? Will leaders support you if you propose radical changes to people, structures, processes, and roadmaps, or are you supposed to change everything but in a way that no one notices?

Zero in the most critical organizational roadblocks to innovation. Chances are, you won’t get the same answers to these questions from everyone you talk to. Those areas where executives disagree with one another will define the most immediate (and often the most fundamental) challenges and opportunities you’ll face in your role.

As quickly as possible within your first 100 days, therefore, you will need to understand where the fault lines lay in your company. Pay particular attention to the three hidden determinants of your company’s true strategy – how it funds and staffs projects, how it measures and rewards performance, and how it allocates overall budgets. A clear understanding of where leaders’ priorities fail to match what the company is actually funding and rewarding will help you identify the biggest hurdles to achieving your longer-term agenda, and where short-term workarounds are required.

Define your intent firmly but flexibly. You don’t need to have all the answers perfectly formulated from the beginning. But you should have a perspective – even on Day 1 – regarding how your role as the innovation leader can help the organization achieve its overall strategy. Look for ways to stretch the boundaries of current innovation efforts, but remember you are not the CEO or CTO. You need them to want to support you, not worry that you are gunning for their jobs. Gambill suggests one way to build this trust is never to bring up a problem without also proposing a solution. The CEO “has lots of people who know how to point out problems; it is important to establish yourself as a problem solver and confidant as quickly as possible.”

Determine how you plan to balance your efforts between developing ideas, supporting initiatives in other parts of the organization, and creating an overall culture of innovation. Those are related, but distinctly different, tasks. Don’t get too rooted to your initial perspective. Be as adaptable in your approach as you will be when you work on specific ideas.

Develop your own view of the innovation landscape around the company. Colin Watts, who has played a leadership role in innovation and strategy functions at Walgreens, Campbell Soup, Johnson & Johnson, and Weight Watchers, suggests getting a “clear market definition ideally grounded in customer insights.” Companies tend to define their world based on the categories in which they compete or the products they offer. However, customers are always on the lookout for the best way to get a job done and don’t really care what industries or categories the solutions happen to fall into. Understanding how customers make their choices often reveals a completely different set of competitors, redefining the market in which your company operates, its role in the market, and the basis for business success.

Watts also suggests zeroing in on the adjacencies that have the potential to shape your market. As he notes, “There is no such thing as an isolated market anymore.” Through an innovation lens you are likely to see early signs of change that the core business might have missed.

Develop a first-cut portfolio of short and longer-term efforts, with a few planned quick losses. A key component of your job, of course, will likely be to advance a set of innovation initiatives. Some may already be in progress. There may be a backlog of ideas waiting to be developed. Or the raw material might be a bit rougher, existing primarily in people’s heads. Regardless, in the first 100 days you want to come up with a clear view of some of the specific things on which you will plan to work. Some of these might be very specific initiatives, like identifying product-market fit for a new technology. Some might involve investigating broader areas of opportunity (for example, “wearables”). Some may involve developing specific capabilities. One specific capability Watts suggests building as an “investment that will pay back for years to come” is a “fast and cheap way to pilot ideas and products.”

Savvy innovation leaders place some long-term bets that they start to explore while also quickly addressing some more immediate business opportunities to earn credibility. If your portfolio is all filled with near-in ideas, some people in the core organization might naturally ask why they can’t do what you are doing themselves. And you are probably missing the most exciting and possibly disruptive ideas in your space. But if the portfolio is filled only with further out ideas, you run the risk that organizational patience will run out as you do the long, hard work of developing them.

When considering quick wins, don’t avoid quick losses. True innovation requires an organization to stop avoiding failure and see the benefits of learning from it. But failure remains very scary to everyone. Have enough things going on that you can tolerate a quick loss without damaging your overall pipeline. As Watts says, “You may be able to do it fast or do it cheap or do it reliably but not likely all three.” Make sure that you and your executive sponsors loudly and proudly celebrate the first project you stop when it becomes clear it won’t work.

That feels like a lot for 100 days, and it is. Innovation has the power to positively transform an organization, but no one said it was going to be easy.

September 3, 2014

How to Market Test a New Idea

“So,” the executive sponsor of the new growth effort said. “What do we do now?”

It was the end of a meeting reviewing progress on a promising initiative to bring a new health service to apartment dwellers in crowded, emerging-market cities. A significant portion of customers who had been shown a brochure describing the service had expressed interest in it. But would they actually buy it? To find out, the company decided to test market the service in three roughly comparable apartment complexes over a 90-day period.

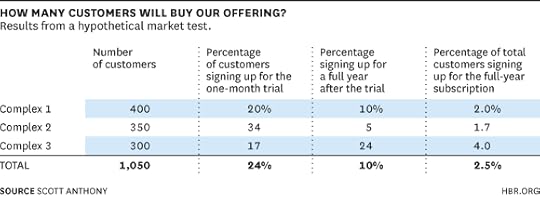

Before the test began, team members working on the idea had built a detailed financial model showing that it could be profitable if they could get 3% of customers in apartment complexes to buy it. In the market test, they decided to offer a one-month free trial, after which people would have the chance to sign up for a full year of the service. They guessed that 30% of customers in each complex would accept the free trial and that 10% of that group would convert to full-year subscribers.

They ran the test, and as always, learned a tremendous amount about the intricacies of positioning a new service and the complexities of actually delivering it. They ended the three months much more confident that they could successfully execute their idea, with modifications of course.

But then they started studying the data, which roughly looked as follows:

Overall trial levels were lower than expected (except in Complex 2); conversion of trials to full year subscribers were a smidge above expectations (and significantly higher in Complex 3); but average penetration levels fell beneath the magic 3% threshold.

What were the data saying? On the one hand, the trial fell short of its overall targets. That might suggest stopping the project or, perhaps, making significant changes to it. On the other hand, it only fell five customers short of targets. So, maybe the test just needed to be run again. Or maybe the data even suggest the team should move forward more rapidly. After all, if you could combine the high rate of trial in Complex 2 with the high conversion rate of Complex 3…

It’s very rare that innovation decisions are black and white. Sometimes the drug doesn’t work or the regulator simply says no, and there’s obviously no point in moving forward. Occasionally results are so overwhelmingly positive that it doesn’t take too much thought to say full steam ahead. But most times, you can make convincing arguments for any number of next steps: keep moving forward, make adjustments based on the data, or stop because results weren’t what you expected.

The executive sponsor felt the frustration that is common to companies that are used to the certainty that tends to characterize operational decisions, where historical experience has created robust decision rules that remove almost all need for debate and discussion.

Still, that doesn’t mean that executives have to make decisions blind. Start, as this team did, by properly designing experiments. Formulate a hypothesis to be tested. Determine specific objectives for the test. Make a prediction, even if it is just a wild guess, as to what should happen. Then execute in a way that enables you to accurately measure your prediction.

Then involve a dispassionate outsider in the process, ideally one who has learned through experience how to handle decisions with imperfect information. So-called devil’s advocates have a bad reputation among innovators because they seem to say no just to say no. But someone who helps you honestly see weak spots to which you might be blind plays a very helpful role in making good decisions

Avoid considering an idea in isolation. In the absence of choice, you will almost always be able to develop a compelling argument about why to proceed with an innovation project. So instead of asking whether you should invest in a specific project, ask if you are more excited about investing in Project X versus other alternatives in your innovation portfolio.

And finally, ensure there is some kind of constraint forcing a decision. My favorite constraint is time. If you force decisions in what seems like artificially short time period, you will imbue your team with a strong bias to action, which is valuable because the best learning comes from getting as close to the market as possible. Remember, one of your options is to run another round of experiments (informed of course by what you’ve learned to date), so a calendar constraint on each experiment doesn’t force you to rush to judgment prematurely.

That’s in fact what the sponsor did in this case — decided to run another experiment, after first considering redirecting resources to other ideas the company was working on. The team conducted another three-month market test, with modifications based on what was learned in the first run. The numbers moved up, so the company decided to take the next step toward aggressive commercialization.

This is hard stuff but a vital discipline to develop or else your innovation pipeline will get bogged down with initiatives stuck in a holding pattern. If you don’t make firm decisions at some point, you have made the decision to fail by default.

June 16, 2014

Why Would Amazon Want to Sell a Mobile Phone?

If you believe the rumors, Amazon.com is going to enter the mobile phone business this week, with most pundits guessing that a mysterious video suggest that it will release a phone with novel 3-D viewing capabilities.

There are obvious reasons for Amazon to be eying the category. The mobile phone industry is massive, with close to 2 billion devices shipped annually and total spending on wireless-related services of more than $1.6 trillion across the world. As mobile devices increasingly serve as the center of the consumer’s world, their importance to a range of companies is increasing.

What should you watch for on Wednesday’s launch to see if Amazon is moving in the right direction? It is natural to start with the set of features that Amazon includes on its phone.

One of the basic principles behind Clayton Christensen’s famous conception of disruptive innovation is that the fundamental things people try to do in their lives actually change relatively slowly. The world advances not because our needs, hopes, and desires change, but because innovators come up with different and better ways to help us do what we were always trying to get done.

Take the big shifts in the music business. People have enjoyed listening to music for all of recorded history. But the biggest industry transformations came when innovators made it simpler and easier for people to listen to the music they want, where they want, and when they want. Thomas Edison’s phonograph was the first big democratization of music, allowing individuals to listen to music without having to hire a live performer, train to be a musician, or go to a concert. Sending sound through the airwaves, received in a radio, furthered this trend, enabling people to hear live sound remotely, or hear a wider variety of pre-recorded music.

Floor-standing radios were relatively expensive and consumed a lot of power. So it was hard for individuals to listen to what they wanted where they wanted until Sony popularized the highly portable transistor radio in the 1960s. The fidelity was low, but teenagers eager to listen to rock music out of earshot of disapproving parents or to baseball games late at night flocked to the device.

It’s difficult to enjoy music if everyone is blaring transistor radios on the subway, so Sony again made it simpler and easier for people to listen to what they wanted, when they wanted, when it introduced the Walkman in 1979. The device, and its offspring the Discman, had one obvious limitation — when people were away from home they couldn’t easily access their music collection. People compensated for this by making mix tapes or lugging around cases with dozens of CDs.

MP3 players, most notably Apple’s iPod, made it simpler and easier to listen to the precise music you wanted when and where you wanted. The first commercials for the iPod highlighted the value of having “1,000 songs in your pocket.” Finally, streaming music services like Spotify removed even the need to build a music collection.

Mobile phones follow a similar pattern. The first wave of growth came as devices from Motorola and Nokia made it easy and steadily more affordable for people to make phone calls and send short messages when they were on the go. Blackberry’s rise came from releasing office workers from their desks by making remote e-mail easy. The next wave of growth came as Apple and Android-based smart phones put productivity and entertainment applications from computers in the palm of your hand.

Leaving aside the hype of 3-D technologies, the big question about Amazon as it enters into this seemingly crowded arena will be whether its offering makes it easier or more affordable for people to do something they’ve historically cared about. Pundits are skeptical, with some calling the potential idea “silly.” But one job a 3-D phone might do better than existing alternatives is enable shoppers to see something before they buy it. People like finding and obtaining new goods, and replicating the in-store experience anywhere in the world could allow more people to shop more conveniently.

Of perhaps even more interest is Amazon’s business model. Market disruptions typically combine a simplifying technology with a business model that runs counter to the industry norm. The prevailing mobile phone model involves service carriers subsidizing the devices in return for locking consumers into two-year phone service contracts and charging them based on usage.

If Amazon were primarily interested in driving more retail purchasing it might come up with completely different pricing and usage models, subsidizing both the hardware and the phone service, perhaps in conjunction with a more disruptively oriented mobile carrier such as T-Mobile, and reaping its profits by taking a cut of transactions enabled by its 3-D platform.

Finally, remember that the true impact of an innovation isn’t always fully apparent when it launches. When Apple launched the iPod in 2001 it was interesting, but when it added the iTunes music store in 2003 an industry changed. Similarly, Google’s super-fast search technology caught people’s attention in the late 1990s, but the development of its AdWords business model a few years later is what made the company what it is.

So on Wednesday look to see if Amazon has found a way to make the complicated simple or the expensive affordable, pay particular attention to the business model it plans to follow, and, most critically, once the dust settles from the pundit reactions, watch what the company next has up its sleeves.

June 13, 2014

No Innovation Is Immediately Profitable

The meeting was going swimmingly. The team had spent the past two months formulating what it thought was a high-potential disruptive idea. Now it was asking the business unit’s top brass to invest a relatively modest sum to begin to commercialize the concept.

Team members had researched the market thoroughly. They had made a compelling case: The idea addressed an important need that customers cared about. It used a unique asset that gave the company a leg up over competitors. It employed a business model that would make it very difficult for the current market leader to respond. The classic fingerprint of disruptive success.

With five minutes left in the meeting, it was all smiles and nods. The unit’s big chief (let’s call her Carol) loved the concept, and in principle agreed with the recommendation to move forward. “I just need to see one more thing,” she said. “Can we talk about your financial forecasts? You’ve told me it’s a big market, but I’m not sure yet what we get out of this.”

The team members smiled, because they were prepared. They knew — and they knew Carol had been taught — that detailed forecasts for radically new ideas are notoriously unreliable. So they instead turned to their best guess of what the business could look like a few years after launch. They detailed assumptions about the number of customers they could serve, how much they could make per customer, and what it would cost to produce and deliver their idea. Even using what seemed to be conservative assumptions, the team’s long-term projections showed a big, profitable idea. Of course there were many uncertainties behind those projections, but the team had a smart plan to address critical ones rigorously and cost effectively.

Carol began to look impatient. “That all sounds good,” she said. “But can you double-click on the next 12 months? We can’t afford to lose money on this for more than nine months. When do you turn cash-flow positive?”

The team had estimated it would take at least two years of investment before there was any chance of crossing that threshold. They were being careful to stage investment, since they knew their strategy would change based on what they learned early on in the market, so they expected to keep early losses modest. But there simply wasn’t a realistic way to meet Carol’s request.

My six-year-old daughter Holly and I debate the existence of unicorns, and Carol obviously would come down on Holly’s side. After all, she was seeking a disruptive idea that would deliver market magic; flummox incumbents; leverage a core capability; was new, different, and defensible; and produced financial returns immediately. Would that such a creature existed!

It’s not really Carol’s fault. She was running a business unit coming off a turnaround, and she had steep financial targets to hit over the next 12 months. If the momentum continued, she was in line for a promotion within the next 18 months. If momentum stalled, well, she faced a different outcome.

The simple truth is that Carol wasn’t in a position to absorb the early-stage losses that developing a disruptive idea almost always requires. As much as we like to believe in overnight success stories, most start-up businesses fail, and those that don’t typically go through a fair number of twists and turns before they find their way to success.

Every company should dedicate a portion of its innovation portfolio to the creation of new growth through disruptive innovation. But companies need to think carefully about who makes the decisions about managing the investment in those businesses. If the people controlling the purse can’t afford to lose a bit in the short term, then you simply can’t ask them to invest in anything but close-to-the-core opportunities that promise immediate (albeit more modest) returns.

That doesn’t necessarily mean pulling all disruptive work to a skunkworks-like home far away from your current operations, because that approach can deny your new-growth efforts access to unique assets of your company, like its brands, technology, market access, or talent. And certainly scaling the business will likely involve the existing business. But to have any hope of disruptive success, early-stage funding has to come from a budget that allows for a long-term view.

Ideally in this case Carol’s boss would have created a central pool of resources to test out early-stage ideas. Carol should have a say in how those funds are deployed on ideas that her unit will ultimately have to invest in to scale, especially since her staff will be called on to contribute to up-front work. But she shouldn’t have to feel the financial pinch from initial investments in software development, early marketing, and so on.

If Carol’s boss wasn’t willing to take the short-term hit, then frankly the company shouldn’t waste time pursuing disruptive ideas. That choice has long-term repercussions. But it can be very clarifying for staffers who would otherwise just end up frustrated that, as they get closer to toeing the first mile of disruption, their sponsors find ever more creative ways to say no.

June 4, 2014

The Industries Apple Could Disrupt Next

After an unprecedented decade of growth, analysts wrote off 2013 as a year to forget for Apple. Most pundits agreed on what was wrong — a lack of breakthrough innovation since the passing of founder Steve Jobs. But in our view, Apple faces a deeper problem: the industries most susceptible to its unique disruptive formula are just too small to meet its growth needs.

Apple has seemingly served as an anomaly to the theory of disruptive innovation. After all, it grew from $7 billion in 2003 to $171 billion in 2013 by entering established (albeit still-emerging) markets with superior products — something the model suggests is a losing strategy.

Back in 2008, we suggested that the key to Apple’s success was that it had perfected a particular disruptive strategy we dubbed “value chain disruption.” That is, rather than employ a new technology to disrupt a company’s business model, an upstart disrupts the entire breadth of an entrenched value chain by wresting control of a critical asset. Thus Apple’s integration of its iPod device, iTunes software, and iTunes music store disrupted the existing music industry value chain from the record labels to the CD retailers to the MP3 device makers. The key to Apple’s success was that Steve Jobs was able to convince the major record labels to sell its critical asset — individual songs — for 99 cents.

Achieving such a wholesale disruption of an industry is exceeding rare because the key players in the existing value chain typically have controlling rights to the scare resource, which prevents a new value chain from forming. And they are understandably loathe to give it up. But at the time, the music labels were under attack by upstarts giving their offerings away for free and were embroiled in a fairly hopeless effort to sue Napster and other music-sharing services into oblivion. In relation to nothing, 99 cents looked pretty good.

The deal Jobs struck allowed Apple to form a new digital value chain for the legal distribution of music content with itself at its center, reaping high margins on its iPod hardware. Apple quickly became the largest music retailer in the U.S. The record labels grumbled that Apple sucked the lion’s share of the profits out of the industry, but it was too late.

Jobs and Apple were able to run this play again with the introduction of the iPhone. About a decade ago, wireless carriers like AT&T, Verizon, and Sprint tightly controlled the wireless telecom value chain through the critical asset – so-called “walled gardens” they had placed around their service that prevented users from putting any nonauthorized content on their phones.

Jobs made the iPhone’s success possible by negotiating the famous deal in 2007 with the then-struggling AT&T Wireless which, in an effort to distinguish itself from its rival carriers, surrendered control over phone content in exchange for exclusive access to the iPhone in the U.S. for three years. As a result, Apple was once again able to create a new value chain, with the App Store playing a role similar role to the iTunes store, and once again reaping high margins on its hardware.

AT&T’s deal with the devil allowed it to grow substantially, but it started a process that has led wireless carriers to increasingly complain that profits have shifted from them to the device and content producers. Customers now decide first what mobile value chain they will join (Apple or Android), and choose a carrier second.

Today, Apple sits at a crossroads. In our view, the question facing CEO Tim Cook isn’t how Apple will remain “insanely great” without Jobs at the helm. It’s whether there are any other value chains it can disrupt in industries both desperate enough to be vulnerable — and big enough to fuel Apple’s further growth beyond its current $171 billion in annual revenues. After all, even modest 6% growth at this point equates to more than $10 billion in new revenue.

Let’s look at four value chains Apple could disrupt, each of which in markets that, on the face of it, seem large enough to offer hope: television, advertising, health care, and automobiles.

The TV market is immense, and Apple has a toe in the door with its Apple TV, a special purpose device that allows users to stream content from the iTunes library and a select group of partners to existing televisions. But by this time, content owners like Time Warner and cable operators like Comcast have learned from the music and mobile phone industries and won’t cede sufficient control over content to enable Apple to disrupt the entire value chain. So, at the moment Apple TV is a $1 billion line of hardware that is so small, relatively speaking, that Jobs dismissed it as a hobby. What’s more, Apple already has to contend with competing offerings from start-ups like Roku and other tech companies like Google and Amazon, both of which have introduced set-top boxes with streaming content services.

Just as traditional television will be with us for many more years, so will traditional television advertisements. The market looks more than big enough for Apple, and it has made several acquisitions that edge onto the market, including Quattro Wireless (a platform for mobile advertising) for $250 million in 2010. But the critical asset in that value chain is the viewership data that Nielsen provides, which sets the price for advertising. And Nielsen has no reason to cede control of it.

Apple might try to compete with Nielsen directly by offering up a superior metric, such as a measure of audience engagement or a way to track actual transactions generated by a broadcast advertisement. That’s not entirely impossible, given the obvious limitations of Nielsen ratings as a predictor either of audience size or of a commercial’s ability to increase sales. But that approach would take substantial investment, and the fight with entrenched incumbents on their own ground would be fierce.

The delivery of primary health care in the United States is ripe for disruption. Apple might conceivably go beyond what seems to be inevitable forays into the fitness and health-monitoring markets to create new disruptive ways to diagnose and deliver primary care and support the ongoing treatment and management of chronic illness. Doing so would require some nifty regulatory maneuvering. It would also require the company to crack a problem that has flummoxed Google and Microsoft: the creation of a simple, common electronic medical record, which could function as the glue of a new primary care value chain.

IBM with its Watson computer seems to be positioning itself as a vital partner for the world’s most complicated problems, but Apple has a demonstrated history of bringing elegant simplicity to the kinds of everyday problems that serve as the core of primary care. Our view is this is the most complicated of the organic options and therefore the one with the lowest chances of success, but the one that also has the most upside potential.

These first three paths are primarily organic in nature. But what if Apple followed through on rumors that it might acquire Tesla, Elon Musk’s rapidly growing electric vehicle company?

Tesla is clearly attempting to disrupt the automobile value chain by building charging stations and battery factories and challenging independent dealers with direct sales. Perhaps combining with Apple would help Tesla navigate the complicated regulatory challenges facing its deployment. However, rather than leveraging preexisting assets at the center of the sprawling petroleum-powered car value chain to disrupt it, Apple and Tesla would have to invest heavily to create an entirely new one. Apple’s vast assets would certainly help Tesla wage that battle, but the required investments would be gargantuan.

None of these options is a slam dunk, of course. If they all end up being strategic dead ends and Apple can’t find another mega-industry value chain ripe for disruption, perhaps the company needs to consider something more radical. A recent article in The Economist counseled Warren Buffet to break Berkshire Hathaway into smaller pieces. Perhaps Cook should consider a similarly radical decision to break Apple up so that the remaining pieces are small enough to again love niche opportunities that aren’t quite so difficult to pull off. Otherwise, Apple’s next decade runs a high risk of looking like Microsoft’s last — steady performance, attractive cash flows, but an overall sense of stagnation.

When Innovation Is Strategy

An HBR Insight Center

The Case for Corporate Disobedience

Google’s Strategy vs. Glass’s Potential

Why Germany Dominates the U.S. in Innovation

How Separate Should a Corporate Spin-Off Be?

June 2, 2014

What’s Holding Uber Back

As a consumer, I absolutely love Uber. The other week I was at a dinner in a relatively remote part of Singapore. Afterwards, the hotel concierge furiously worked three phones to get taxi cabs to appear for the 15 people who were waiting with growing impatience. I clicked three buttons, and my ride was there in 12 minutes. It’s simple, and it works beautifully.

I also love Uber as a student (and teacher) of disruptive innovation theory, because the challenges the transportation company is encountering as it seeks to expand into new cities helpfully illustrate how to assess an idea’s disruptive potential.

This is important, because companies that adhere as closely as possible to the patterns of disruption have the greatest chance to create explosive growth and transform markets. Those that deviate from the approach can succeed, but they are likely to have to fight much harder and spend much more.

Based on our field work applying Clayton Christensen’s foundational research on disruptive innovation, we look at potential disruptors’ performance in three critical areas.

First, the would-be disruptor should follow an approach that makes it easier and more affordable for people to do what historically has mattered to them. Making the complicated simple and the expensive affordable is why disruptors have the potential to dramatically expand a constrained market or prosper at price points that are far lower than market leaders’.

Uber nails this. Getting a taxi is a maddeningly complex task in cities around the world. Uber’s slick user interface solves the problem in a simple, elegant way. It has had to deal with occasional customer complaints about so-called surge pricing (when the price of a ride shoots up dramatically at times of high demand, such as during major weather events or on New Year’s Eve). But it probably has a more committed user base than any business launched in the last five years.

Next, the innovator has to develop a behind-the-scenes advantage: a way of producing a product or service that seems magical from the customer’s perspective and that is difficult for other companies to replicate. Ideally, the innovator has a proprietary technology that makes the offering simple and affordable, or it has developed an innovative operating model that enables the business to keep its costs radically lower than competitors’ as it scales up. Either (or ideally both) of these advantages helps the innovator defend itself when existing competitors or others inevitably respond by trying to emulate its success.

Uber looks solid here, as well. Its powerful back-end system allows it to manage a real-time network of cars in an extremely simple and potentially low-cost way. It can take advantage of network effects in its operations, since the more drivers it recruits, the more valuable its service become and the more other drivers want to join in.

The final area — and the one where Uber faces clear challenges — is whether the would-be disruptor is following a business model that takes advantage of “asymmetries of motivation”. In simple terms, that means a disruptor is attacking markets that existing companies are motivated to exit or ignore because they are unprofitable or seemingly too small to matter. (We discussed these in detail in Seeing What’s Next.)

Consider the early days of Salesforce.com. The company sold its cloud-based customer relationship management software to small companies that could never afford more-sophisticated applications sold by industry leaders like Siebel. Salesforce.com didn’t compete against these applications. It competed against pen and paper and handmade spreadsheets. In its early days, market leaders felt no pain because Saleslforce.com wasn’t taking away any of their customers; rather, it was creating new ones.

The other way disruptors take advantage of asymmetries of motivation is to build a business model that makes it financially unwise for incumbents to respond. This is at least one reason why Netflix ended up crushing Blockbuster. Netflix’s business model did not require it to charge the late fees that made up the vast majority of Blockbuster’s profits. Naturally companies are unlikely to follow strategies that appear to destroy profitable revenue streams or promise to lose them money.

Uber is following neither of these paths. It targets exactly the same customers that taxi companies want. And customers pay fares that are generally comparable, if not higher, than ordinary taxi fares. Taxi companies therefore are naturally neither motivated to ignore nor to flee from Uber. Rather, they are fighting fiercely with every tool at their disposal, including protests by taxi drivers and legislative action.

Worse, the battle between traditional taxis and Uber has attracted opportunity-sniffing entrepreneurs who want to help the incumbents fight back. For example, one of the most popular apps now in Singapore is called GrabTaxi, which uses an Uber-like mobile interface to simplify the process of ordering a traditional cab. That allows cab drivers to offer many of the conveniences of Uber without being disintermediated. GrabTaxi isn’t trying to disrupt the market; it’s trying to help established companies fight back against entrants.

All of these battles are great for consumers, who get to enjoy simpler, increasingly more convenient solutions. There’s little doubt that Uber will continue to penetrate the markets it targets — particularly with its growing war chest of venture capital funding. But because it appears to be missing a key disruptive ingredient, the fight looks like it will get increasingly difficult and expensive.

April 21, 2014

Why You Have to Generate Your Own Data

This is it. You’ve aligned calendars and will have all the right decision-makers in the room. It’s the moment when they either decide to give you resources to begin to turn your innovative idea into reality, or send you back to the drawing board. How will you make your most persuasive case?

Inside most companies, the natural tendency is to marshal as much data as possible. Get the analyst reports that show market trends. Build a detailed spreadsheet promising a juicy return on corporate investment. Create a dense PowerPoint document demonstrating that you really have done your homework.

Assembling and interpreting data is fine. Please do it. But it’s hard to make a purely analytical case for a highly innovative idea because data only shows what has happened, not what might happen.

If you really want to make the case for an innovative idea, then you need to go one step further. Don’t just gather data. Generate your own. Strengthen your case and bolster your own confidence – or expose flaws before you even make a major resource request – by running an experiment that investigates one or a handful of the key uncertainties that would need to be resolved for your idea to succeed.

That may sound daunting if you haven’t tried it. And, you may well ask, how do you do it when you lack a dedicated team and budget? Fortunately, there’s a fairly systematic way to go about it.

Start by focusing your attention on resolving the biggest question on the minds of the people who will decide to give you those resources. That might be whether a customer will really be willing to use – and purchase – your proposed offering. Or perhaps whether the idea is technologically feasible. Or maybe there’s concern that some operational detail could stand in the way of success.

Once you’ve identified the most important potentially “deal-killing” issue, the next step is to find a cheap and quick way to investigate it. The key here is to find some low-cost way to simulate the conditions you’re trying to test.

For example, for several years Turner Broadcasting System (a division of Time Warner) had been playing with the idea of tying the first advertisement in a commercial break to the last scene in a television program or movie. Imagine a scene of a child landing in a mud puddle followed by a commercial for laundry detergent. Academic research showed this contextual connection had real impact, raising the possibility that Turner could charge a highly profitable premium to match the right advertiser to the right commercial slot. But would the system it used to match its content to advertisers’ offerings be too expensive to make the service profitable? And what if there just weren’t enough scenes in Turner’s library of movies and TV programs that could serve as effective contexts for its advertisers? How could the project team find out?

Instead of speculating, Turner locked a team of summer interns in a room for a few weeks, had them watch movies and television shows, and asked them to count the number of points of context in a select group of categories. Then Turner brought the results to a handful of advertisers, who enthusiastically supported the idea.

Imagine how these experiments changed the meeting. Without them, the team would have presented a conceptual plan full of glaring unknowns. But with these data in hand, they could offer evidence that the idea was feasible and that potential advertisers were interested. Perhaps not surprisingly, Turner ended up launching the idea, named TVinContext in 2008 to significant industry acclaim.

Working out how to generate data to test out an idea at its earliest stages requires some creativity. A mobile device company we were advising was considering a new service that would serve up customized content to consumers based on their mood and location. Would anyone want that? Would they pay for it?

To find out, we had to find a low-cost way to simulate the offering and some way to test people’s interest in something that didn’t actually yet exist. First we worked with third-party designers we contacted through eLance.com to develop mockups of what the interface might look like and worked up a two-minute animated video describing how the service would work. Here’s a screenshot from the video:

How could we tell whether the idea resonated with customers? Of course we could show them the mockups and videos and ask them if they liked or didn’t like the idea. But that really wouldn’t tell us whether they liked it enough to use it, let alone pay for it. So we asked customers at the end of the presentation if they wanted to be the first to participate in a beta test of the idea. All they had to do was give us their credit card number, and we’d charge them $5 once the test started. We didn’t actually plan to charge the consumers. Instead, we wanted to know how many were interested enough in the service to part with sensitive data in the hopes that they’d be first in line to access it when commercial trials began. When a significant number of customers were willing to give us credit card details, we knew we were going in the right direction.

One of the most valuable things these kinds of experiments can do is provide dramatically convincing evidence of serious flaws in your idea before you make the mistake of investing serious resources in it. The results from one concrete demonstration is worth reams and reams of historical market data.

For instance, an education company had what at first looked like a really promising idea to improve the quality and efficiency of teacher recruiting. Schools and applicants have long complained that paper résumés aren’t very good indicators of teaching ability and interpersonal skills. What if, the company wondered, we created a service that allowed schools to review short video clips created by prospective teachers showing them in action? Both teachers and schools loved the concept — on paper.

But then the education company tried to get real teachers to create real videos. It advertised the service in a handful of teacher-training colleges and put posts on on-line forums about the service. No interest. The company even began offering $100 for people to sign up. Still no interest.

It turned out that once the opportunity shifted from abstract to real, prospective teachers clammed up. They loved the concept of selling themselves through video, but in reality worried about how they would come across.

Notice how all of these examples involved some kind of prototype. As online tools improve and 3D printing becomes increasingly affordable and accessible, it’s becoming easier and easier to bring an idea to life without substantial investment. For example, a company that manufactures insulin pumps for people who suffer from Type 1 diabetes knew that customers didn’t love the physical designs of current pumps. The company was curious to find out how patients would react to pumps of different sizes and shapes. It worked with a small design shop in Rhode Island to develop a series of physical prototypes that brought the look, feel, and weight of the imagined devices to life. It had insulin pump customers pick up and play with the prototypes and compare them side-by-side with current offerings. The approach allowed the company to get critical feedback before it invested millions in more comprehensive design work.

None of the experiments described above required hundreds of thousands of dollars or hundreds of man hours. And yet they all quickly generated critical data that helped innovators to strengthen – or, in the case of the education company, discard – ideas. When it comes to making your case persuasive, one well-thought out experiment is worth a thousand pages of historical data. Certainly that’s well worth a little extra effort.

Persuading with Data

An HBR Insight Center

How to Have an Honest Data-Driven Debate

The Quick and Dirty on Data Visualization

To Tell Your Story, Take a Page from Kurt Vonnegut

Don’t Read Infographics When You’re Feeling Anxious