Omid Malekan's Blog

October 7, 2020

A Defense of Keeping Politics Out of Crypto

Brian Armstrong, the CEO of the leading American crypto exchange, caused a stir recently when he announced a policy of keeping Conibase out of political and social activism to better focus on its core mission. He backed up the decision with a generous buyout for any employees who disagreed. In his own words:

Many companies never stand the test of time, because they decide to dabble in unrelated efforts, and distract and divide their workforce in the process. Paradoxically, by being laser focused on our mission, we will likely have an even greater impact on the world, through our products and growing customer base.”

One should read the entire post before reacting, as some of the people who have responded negatively clearly have not. There’s more to his argument than “we are just here to make money,” and the online pundits who insist on reducing it to some caricature of capitalism just validate the overall argument.

Armstrong says that he doesn’t want the pursuit of outside causes to distract Coinbase from the core work of building an open financial system that provides greater access to everyone, because executing on that mission will have a greater impact than activism. I support this approach and hope that more crypto companies adopt it — leaving the tweeting, campaigning, protesting and every other kind of vocal activism to others.

My reasoning starts with that famous proverb that Mohandas Gandhi — the man often credited for it — never said: to be the change we want to see in the world. It’s a powerful saying, regardless of who came up with it, but lacking in practical instructions. Thankfully, what Gandhi did say was more nuanced.

“All the tendencies present in the outer world are to be found in the world of our body. If we could change ourselves, the tendencies in the world would also change. As a man changes his own nature, so does the attitude of the world change towards him. This is the divine mystery supreme. A wonderful thing it is and the source of our happiness. We need not wait to see what others do.””

That last sentence makes all of the difference. There’s a false belief in today’s discourse that yelling about a problem, or shaming those considered responsible for it, go a long way toward solving it. They don’t. Outrage is the state of being upset over something and demanding somebody else fix it. Real change takes individual action — but not, as the Mahatma believed — the kind that impacts others, but rather the kind that impacts the self. A million people tweeting about the need to end racism wouldn’t change much. Those same people taking the time (and summoning the humility) needed to confront their own biases — the kind that all of us, myself included, suffer from — would make a genuine impact.

But that’s doing, and doing is hard. Retweeting is easier. So everyone gets caught up in a recursive loop of posting and protesting, then being upset that nothing has changed, then getting louder. Sides are picked, battle lines are drawn, and little is accomplished. Doing is more effective, but easily distracted by the need for validation. A company deciding to have more minorities in executive positions is great. That same company issuing multiple press releases before the first promotion is less great.

Which brings us back to crypto. One of the things that shocked me about Bitcoin when I first learned about it was its sheer openness. Anyone could do anything, from owning the coins to writing the code to participating in mining to building the supporting infrastructure (as Coinbase has). If you wanted to build the next great crypto wallet, all you had to do was build it. It didn’t matter if you were young or old, black or white, gay or straight, American or Iranian, an experienced coder or a total noob. The only thing that mattered to the rest of the community was the usefulness of your product, which you were free to build however you thought best.

This was a stark contrast to the traditional financial system, where nothing could be done until you were given permission by a gatekeeper, and the first thing the gatekeeper would ask you to do was to fill out a form, and that form asked you to disclose your name, age and address — information which could easily be used (or misused) to make conclusions about your gender, nationality and race.

Decentralization is often portrayed by the skeptics as a negative, an open invitation to the world’s anarchists or criminals to cause mischief. But decentralized also means “doesn’t discriminate.” When there is nobody in charge, there is no ability to oppress or exercise bias. Our existing financial system on the other hand is built on bias.

Case in point KYC, or the almost universal requirement for traditional financial services providers to “know their client.” Such requirements are designed with good intent, to cut down on financial crime and prevent the use of the banking system for illicit activity. But they are costly, and that cost is borne disproportionately by the underprivileged. Even when executed fairly, KYC requirements mean that poor people who don’t have proper ID, migrants who don’t have a fixed address or undocumented workers trying to stay under the radar can’t get a bank account. That is the best case scenario. The worse case scenario is the personal information gathered for these requirements are used to practice racism, sexism and every other kind of discrimination.

The blockchain doesn’t discriminate, because the blockchain doesn’t know, and better yet, doesn’t give a damn. All anyone needs to access bitcoins is free software — making the bitcoin platform the first digital platform that can’t pick favorites. As far as the protocol is concerned, a billionaire in America gets the same amount of access as a farmer in Thailand. Not because there are laws against discrimination or because miners have undergone sensitivity training, but because both users look exactly the same to every other participant.

A more abstract, but arguably more insidious form of discrimination within the legacy financial system is the distribution of new money. In crypto, new coins are generated algorithmically and distributed to those who contribute the most, be they miners, coders or users. It doesn’t matter who they are, where they live or which political candidate they’ve contributed to. The fiat domain works on the opposite principle. Newly minted dollars, euros or pounds usually go to those who deserve it least, like “too big to fail” banks in the last economic crisis or any corporation that has access to public capital markets in this one.

Central banks such as the ECB and Federal Reserve are now using printed money to subsidize the borrowing of large corporations, including that of mega tech companies like Apple and Microsoft, a corporate subsidy for highly profitable companies who have actually benefited from the pandemic. Since they don’t need the money, these companies will just use the subsidy to drive up their stocks via share buybacks. According to the Fed’s own data, stock ownership in the U.S. skews heavily towards the old, the white and the rich. That makes Fed programs that benefit the market (which is practically all of them) a form of systemic discrimination, executed to the tune of trillions of dollars. No wonder the current chairman has started giving speeches on the need to tackle racism. A little bit of saying to whitewash all of that tragic doing.

All of these issues are amplified in developing countries where access to basic financial services are even more limited and government institutions are a lot more corrupt. But there is hope, because the same meritocratic and open approach to financial services that was pioneered by Bitcoin is now being applied to everything from fiat currencies to banking. Argentinians fed up with endless government defaults and devaluations could now save in a dollar-denominated stablecoin called Dai, and expats who are often can’t use banks will soon have much better remittance options, including Libra.

Further out on the horizon are protocols for borrowing, lending and investing. Not just in crypto, but tokenized versions of every other asset class, from gold to real estate to collectible art. Such products are not available to the vast majority of people today, due to a tragic mix of poor infrastructure and bad policy. This lack of access has been a prime contributor to the explosion in the wealth gap over the past decade, and when combined with the other types of discrimination inherent to our financial system, form a de facto conspiracy by economic elites to make sure nobody else catches up to them. Put differently, the New York Stock Exchange, Sotheby’s and the SEC are not about to make investing a universal right, but the Ethereum blockchain just might.

I don’t mean to exaggerate the benefits as they stand today. Bitcoin is still too small to make a difference and stablecoins and other forms of tokens are too new to make a dent. But they represent a new way of doing things, one that is superior along the axis that society increasingly cares about, such as equal treatment and universal access. Bringing that vision to the masses will take a lot more doing, and some of it will have to be done by companies like Coinbase. So Brian Armstrong was correct. The company can have a much greater impact on social justice by focusing on its core mission. As can everyone else in crypto.

September 25, 2020

Decentralized Finance as Value Creator and Destroyer

defipulse.com

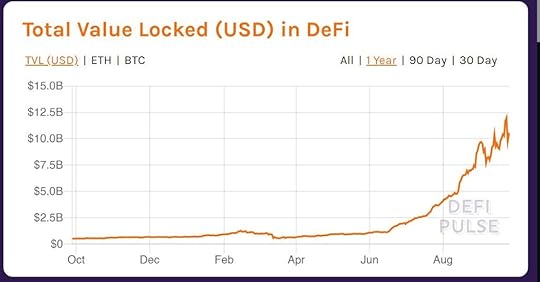

defipulse.comAs you’ve probably seen, DeFi on Ethereum is now the hottest thing in all of crypto, further establishing the platform’s first mover advantage, and firing what should be perceived as a shot across the bow of traditional financial services. The success of the movement is attributable to three fundamental properties of decentralized blockchain networks:

Composability: Any output of an existing solution — such as collateralized lending or automated market making — could easily be used as an input of a new solution. This means that developers can build on the work of others, mixing and matching existing services to create their own financial supermarkets (what the crypto kids call money legos).Transparency: Every project is transparent, open-source and imminently replicable. Not only can developers look under the hood of successful projects, they can copy the code and introduce their own variation.Permissionless: Anyone can do anything. There are no licenses to acquire, vendors to onboard, KYC procedures to follow or AML/CFT laws to be crippled by. Those who have innovative ideas build them and those who like the resulting service use them. Full stop.Also aiding the boom is a growing cast of supporting infrastructure in the form of stablecoins, oracles and ramps to other platforms such as Bitcoin. All of this has been around for years, as have the earliest DeFi protocols. But the action didn’t take off until the arrival of liquidity mining earlier this year, an innovative incentive scheme best understood with an analogy: Back in the day, banks used to give away toasters for opening a new account. DeFi projects go one step further and give away equity, in the form of a governance token. The more users borrow, lend, provide liquidity or trade in a particular protocol, the greater the claim on future revenues and say in ongoing governance that they get.

Liquidity mining is the decentralized and community-owned ethos of the crypto universe expanded to financial services. There is no off-chain equivalent, but analogous to Robinhood giving away free stock to its clients based on usage. (RH would never do this, because the infrastructure can’t handle it and the regulators won’t allow it— yet another reason why the only real innovation in financial services is happening on the blockchain).

The introduction of liquidity mining set the DeFi world on fire. Even those who didn’t have an immediate need to lend, borrow or trade started doing so to earn a reward. This spike in activity created a virtuous cycle: the more people used a protocol, the more valuable the token it was giving away was perceived to be, so the greater the incentive for new users to join the party. In just three months, the value of assets involved with DeFi went up 10x, and fees on Ethereum surged as well.

All of this is great for adoption, energy and excitement. DeFi has reinvigorated the crypto ecosystem, attracted attention from outsiders and caused even greater agita for regulators still grappling with the difference between security tokens and tokenized securities. What it’s not great for is the value of the DeFi governance tokens themselves. This might be considered heresy in the most devout DeFi circles, but I would argue the vast majority of DeFi tokens are borderline worthless. Why? Because of what makes DeFi great in the first place. Put in crypto speak:

Composability + Transparency + Permissionless = No Moat

Put in plain English: If you build it, they will come, but then someone will build a replica, and they will leave. In a world where anyone can do anything, including copy your code, tweak your solution and parody your name, then every successful project will have imitators, and since there are no account signups, national borders or regulatory barriers, your customers can become their customer with a single click. This isn’t just speculation, it has already happened, with comical naming conventions to boot. The popular decentralized exchange Uniswap yielded Sushiswap which was then copied into Kimchiswap. Another popular service called Curve was forked into Swerve, and the robo-yield-farmer Yearn has spawned more copycats than one can keep track of.

At issue is the fundamental equation of trust. The main goal of a decentralized platform like Ethereum is the minimization of counterparty risk — a fundamental driver of financial innovation for millenia. The platform’s success in doing so makes it both easy to build new solutions and hard to monetize them, because everyone shares the most important edge. This is not the case in traditional finance. You can spend billions of dollars replicating the physical infrastructure of the NYSE or BoA, but end up with none of their customers, because you won’t have the licenses, reputations and relationships that make those entities trustworthy.

Ironically, that means the only lasting value any DeFi solution could have comes from the messy and more centralized stuff that you can’t just copy and paste, such as business development, VC backing and human talent. It also means that the oldest DeFi protocols who have the most sophisticated teams and weathered more than just a single season are the only ones worth owning at current prices. My favorites are MakerDao, Compound, Aave and Uniswap. Everything else is either too new, too unproven, too unused or too easy to copy (Maker increasingly seems like the only solution that’s truly fork proof, given Dai’s growing penetration into obscure corners of the ecosystem, and Latin America)

Even more ironically, the market currently values most of these protocols in the opposite order that I do. The DeFi aggregator Yearn, which would have no reason to exist if not for the base protocols it feeds, has a higher market cap than all of them. The synthetic asset maker Synthetix, whose sUSD stablecoin has less than $60m in distribution, is valued more than Maker, whose Dai stablecoin is approaching $1B. These disparities are the result of the crypto world’s never ending (and always embarrassing) desire for free money. Maker isn’t giving away any equity, while SNX is giving away plenty.

These disparities will eventually be resolved. The valuations of the core protocols will rise to the top while some of the current high-flyers will end up worthless. But even then, the upside will always be capped by the fact that competition is easy to build. The most sustainable winners will be the off-chain infrastructure providers, for the simple reason that you can’t fork USDC’s cash reserves or Bitgo’s cold storage.

And once again, the biggest winner of all will be Ethereum itself, as DeFi has only increased its value and cemented its first mover advantage. It is a mistake to assume that today’s astronomical transaction fees are anything other than a blessing. Demand outstripping supply is the best thing that can happen to any startup.

The opinions expressed here are strictly my own and not that of any employer, client or associate. I own some of the tokens mentioned above. If you can’t pronounce composability, you probably shouldn’t.

July 3, 2020

Fractional Reserve Banking Comes to Crypto

source: defipulse.com

source: defipulse.comActually, that title is a lie. It was always here, and is a natural tendency of crypto’s purported role as money. I love the passion and open-mindedness of the hardcore “cryptocurrency is better money” crowd, but sometimes they are so open minded that they convince themselves of things demonstrably untrue. One of those things is the false belief that fractional reserve banking only happens with fiat currency like the U.S. Dollar. In truth, the activity long predates fiat currency, and is in some ways as old as money itself.

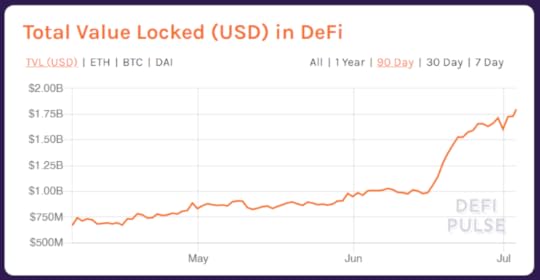

This post was inspired by recent developments within the Decentralized Finance sector on Ethereum, where there has been a surge of users depositing and borrowing a stablecoin called Dai from a decentralized money market called Compound, as can be seen here:

source: compound.finance

source: compound.financeThe actual lending and borrowing and lending of Dai is not that interesting, and not that different from what goes on at your corner bank. Savers hoping to earn yield have deposited $518m dollars worth of Dai, $476m of which has been borrowed by those in need of capital. What is interesting is the fact that the amount of Dai currently sitting in Compound is far greater than the amount of Dai ever generated by its own decentralized protocol in the first place.

source: makerburn.com

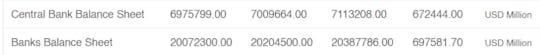

source: makerburn.comUpon first glance, this seems impossible. How could Compound users deposit more Dai tokens than exist? The numbers aren’t wrong, because unlike with your corner bank, everything that happens on the blockchain is transparent and independently verifiable. There are no mistakes here, just magic, the same kind of magic that exists in the traditional banking system. To wit, consider the latest stats from the Federal Reserve:

source: Federal Reserve

source: Federal ReserveThe top number is the total amount of dollars created by the Fed, as represented by physical coins and bills, and the reserves commercial banks have to keep at the Fed. These dollars — known as the monetary base — happen to be the highest quality dollars in the world, because the Fed is unlikely to fail.

The bottom number represents the amount of dollars currently deposited with commercial banks. Here too we have a large discrepancy. Somehow, banks such as Wells Fargo and Chase and have far more dollars deposited with them than was ever created by the Fed. This is not an illusion, nor is it some kind of fraud. In fact it’s what we expect to see in any economy where there is borrowing and lending, because credit creation always increases money supply.

To see how, let’s walk through a simple example. Let’s say that you have a $100 bill, and decide to deposit it at a bank. The bank would like to earn a profit, so it lends $20 of your money to somebody else. You as the depositor are mostly oblivious to this loan, and still consider yourself as having $100. But a total stranger now has $20 that she didn’t have before, so the total supply of money has grown.

To be fair, not all of the dollars in question here are created equal, and the magic is aided by the conversion of one kind of money into another. The $100 bill that you started out with is a claim against the Fed (if you look closely, it will say “Federal Reserve Note” at the top). That makes it central bank money, also known as public money. Depositing that $100 bill at the bank converts it to commercial bank money, also known as private money. Commercial bank money is always riskier than central bank money because commercial banks are more likely to fail than an arm of the government granted the right to print more money. But people who have savings accounts don’t think this way, they just think “I have $100, and it’s at the bank.”

(As a side note, the current debate on whether central banks should issue their own digital currencies is in part driven by the fact that the digitization of payments as currently only offered by private entities is slowly diminishing public access to central bank money).

Note that the inflationary impact of credit creation on the total money supply applies to every kind of money, not just the fiat variety. If you have five gold bars and lend one to a friend, you have technically swapped a portion of your base money for a liability against your friend. But you expect to get that gold back, so you still think of yourself as having five bars. Your friend on the other hand has one bar that he didn’t before, so the synthetic gold supply is now 6. Money supply isn’t how much money people physically posses — it’s how much money they think they have.

Note further that the same thing could happen, and in fact already does, with Bitcoin. There are services such as BlockFi that let you deposit your cryptocurrency to earn interest. They do this because they turn around and lend some of those coins to exchanges who need liquidity or traders who want to short Bitcoin. The second you send your coins to BlockFi, you are technically not in possession of them anymore, and instead own a claim against BlockFi. But in your mind, you probably don’t think “I don’t own any Bitcoin, I only own a claim against BlockFi.” You just think “I own 5 Bitcoins, when moon?”

This brings us to the central fallacy of Bitcoin and any other type of hard money such as gold, that there is truly limited supply. Yes, physical or algorithmic scarcity can limit the monetary base (and that is indeed distinct from fiat currency, where the Fed just created a cool 2 trillion worth of new dollars). But there is never a limit on how much additional supply can be generated from credit creation

Your favorite blockchain explorer might tell you that there are currently 18.42m Bitcoins in existence, but the actual number is greater, thanks to services like BlockFi and the wBTC money market on Compound (not to mention individuals who may occasionally lend a coin to a friend). This phenomenon can also go in the opposite direction, as credit destruction reduces the total money supply. The fear of that happening, and its consequences on the broader economy, is the main reason why central banks love to pump during a crisis.

source: Federal Reserve

source: Federal ReserveGoing back to Dai, what’s happening now is that in order to earn free COMP tokens (the DeFi equivalent of the free toaster) people are depositing as much Dai as they can get their hands on into Compound. Some of those users are using their deposits as collateral to borrow even more Dai, effectively lending and borrowing the same asset from the same bank. As strange as this may sound, it’s not that unusual, and is not that different from someone who already has a savings account taking out a loan and depositing the borrowed money at their bank. This is why the money multiplier is such a potent force.

As with anything else in the economy, there is no free lunch here. Regardless of whether it happens at Wells Fargo or on DeFi, and whether it’s denominated in dollars or Dai, all of this synthetic money creation via lending comes with credit risk. The interesting question that DeFi poses is whether users are taking more or less risk when they interact with a decentralized bank.

On the one hand, transparency, automation, censorship resistance and trustlessness should reduce risk. As I’ve said many times before, one of the appeals of projects such as Compound is that the general public knows more about them than your typical CEO does about his own bank. On the other hand, smart contracts can be hacked and blockchains can fail, especially when they are relatively young. So let’s call it a wash— although I suspect that DeFi will gain in the years to come, particularly once central bank digital currencies enter the mix.

In the meantime, critics of fractional reserve banking, many of whom tend to be closed-minded Bitcoin maximalists, should take note that all of this adoption is happening on a single platform, and it’s not their favorite.

May 28, 2020

What Crypto Is and Isn’t

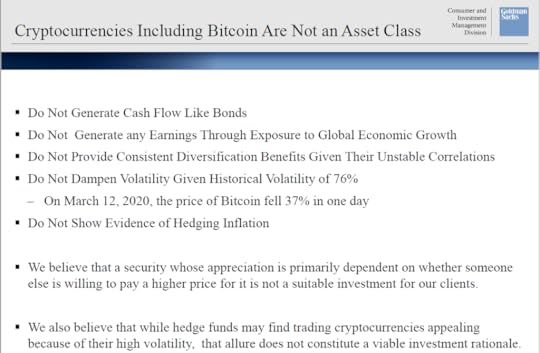

The first thing to note about the slide above, which comes from a recent Goldman Sachs presentation that got some crypto enthusiasts in a tizzy, is that all of the listed characteristics of Bitcoin are accurate. The second thing to note is that it’s just one slide inside a 45 page presentation that’s mostly about gold, and why people shouldn’t invest in either.

If we go back a few years and tell most crypto enthusiasts that come 2020, a major Wall Street outfit would be discussing 10 year old Bitcoin in the same conversation as antediluvian gold, they’d be ecstatic. So most of the complaints on crypto twitter are somewhat misplaced, and betray the inferiority complex that still defines our young industry. Anyone convinced that crypto will go up substantially should celebrate a presentation like this. It gives them something to joke about when they cash out their millions and call Goldman Sachs to open up a private bank account.

That said, I do have a few bones to pick here, starting with the title of the slide. There is something preposterous about the conclusion that “XYZ is not an asset class.” It’s sort of like saying that a style of painting is not art, or that a certain person is not cool. Who gets to decide such things? Are inverse volatility ETFs prone to the occasional blow up an asset class? How about futures tied to a commodity that may trade deep into negative territory?

Better yet, what about bonds with negative interest rates? The first bullet of the above slide calls out crypto because it “doesn’t generate cash flow like bonds.” Thanks to extreme central bank intervention, neither do an ever growing list of, well, bonds. As with Bitcoin, German Bunds currently “Do Not Generate Cash Flow.” Does that mean European sovereign debt is no longer an asset class?

There are few things in life that I hate more than semantic arguments. They are a waste of my time and never teach me anything. They are also a sign of a lesser mind, a favorite tool of those who can’t engage in a substantive debate and instead distract with pointless arguments over what the meaning of the word is is.

I have no problem with the Consumer and Investment Management division of an investment bank telling its clients not to invest in crypto. It’s probably sage advice given the risk profile and return expectations of their audience. But the reasons given betray a lack of sophistication. For example, consider the following critique found later in the same presentation:

Though individual cryptocurrencies have limited supplies, cryptocurrencies as a whole are not a scarce resource. For example, three of the largest six cryptocurrencies are forks — i.e., nearly identical clones — of Bitcoin (Bitcoin, Bitcoin Cash, and Bitcoin SV).

True enough — and moronic. Akin to saying “though gold itself has limited supplies, metals as a whole are not scarce. For example, aluminum and iron are the third and fourth most abundant elements in the earth’s crust.” Or better yet: “though individual social media networks enjoy certain network effects, anyone can start a new social media service by writing a few lines of code. For example, my cousin Joey recently made a knockoff of Instagram called Joeygram”

Bitcoin’s hash rate — the total amount of computing power dedicated to mining — is currently over 30x that of Bitcoin Cash and 50x that of Bitcoin SV. Hash rate is synonymous with security, and security is fundamental to the coin’s scarcity — one reason why Cash and SV both trade at a fraction of the dollar value of Bitcoin (and why cousin’ Joe’s newest venture, Bitcoin Joey, is totally worthless).

There is more cherry picked foolishness within the deck that I won’t spend too much time on, like the “parabolic price appreciation indicates bubble” argument (Zoom stock is up over one million percent since its seed funding round) and the “used in illicit activity” canard (more crime gets committed using dollars in a single day than crypto in a full year).

The biggest takeaway here is the fact that crypto was singled out as something not to invest in, and that this conclusion was communicated by declaring what Bitcoin isn’t. I come across this sort of double-negative analysis in my work within academia and on Wall Street all of the time. The professors say Bitcoin is not money and the bankers announce that crypto is not an asset class. Both remind me of the great Marshall McLuhan, and the observation that the medium is the message.

More telling than what either group believes is how they go about communicating it. It tells us that all of these people, the elites of the old guard, suffer from their own inferiority complex. Some part of them understands that the world is about to change, and that once it does, those who cannot grapple with its unique attributes — things like hash rates, algorithmic scarcity, and the like — will not be as important as they are today. So they perseverate on what the technology isn’t and how the future can’t be.

What they don’t realize is that making something a taboo only accelerates the pace of adoption. There was a time when rap wasn’t music and playing video games wasn’t a career, and it wasn’t that long ago. I don’t know what happened to the experts who said those things, but doubt anyone cares what they have to say about hip-hop or e-sports today.

The opinions expressed here are strictly my own and not that of any affiliated employer, client or university. I own some crypto, but unless you understand what hash rate means, you probably shouldn’t.

May 9, 2020

For this, there will be hell to pay

I still remember all of the signs of seething public anger. A TV rant against the bailouts that went viral. Voters venting against their representatives in town halls. Kids showing up to occupy a strangely named park. It was the period after the last financial crisis, and people were pissed. Not so much about the housing crash — that was accepted as the inevitable consequence of a speculative binge that consumed everyone from their neighbors to Lehman Brothers. No, what most people were angry about were the proposed solutions.

Somehow, those who benefited the most on the way up would suffer the least on the way down, while those barely hanging on would be allowed to drop into the economic abyss. Somehow, CEOs who called on Washington got generous bailouts while borrowers who called a helpline only got a busy signal. The banks were saved, but only to go on pushing foreclosures (and paying bonuses). Cheap financing was made available, but most of it got taken up by the people and companies who needed it least. Individuals who lied on a single mortgage application were jailed, but executives who lied on a thousand were promoted.

All of that anger eventually metastasized into the political movements we recognize them as today: Tea Party cum Make America Great Again, and Feel the Bern nee Occupy Wall Street. Despite their differences, the populist movements of the right and the left can be traced back to the same original sin, and a lingering suspicion by many since the last crisis that the system is somehow rigged. That suspicion can now be removed entirely. Of course the system is rigged. The proof might not be in the headlines, but you can see it in the fine print.

Last Friday's dismal jobs report, and the exuberant market response, were the crowning achievements of a broken system. Somehow, the fastest main street collapse in economic history was perceived as a positive by Wall Street. And no, this wasn’t some temporary market rebound after a brutal decline. Stocks have been rallying for over a month and are not only significantly off their lows but higher than they were a year ago. Some stocks are even up on the year, meaning the investors who bought them long before ever hearing the word coronavirus have net benefited from the resulting decimation.

The experts, many of whom are also befuddled by this dichotomy, offer various explanations. “The economy is bad, but it’s set to rebound” they say, or “the market is mostly made up of tech stocks, and tech is the clear winner here.” These are not convincing arguments. They are after-the-fact justifications of a shocking new reality. Assets do not appreciate in value because an unexpected and terrific shock is only temporary, and the biggest corporations in the world don’t win from a 30% collapse in GDP because “the internet.”

Amazon is not Zoom and Apple is not Clorox. These are massive businesses that touch every corner of the economy, so they can’t only benefit from record unemployment. For every shelter-in-place practitioner ordering delivery from Whole Foods there are two unemployed waiters no longer buying new shoes from Zappos. For every two AWS clients increasing usage because of remote work one is about to go out of business. Among the 30m people who are newly unemployed, some will not be in the market for a new iPhone.

Shares of Amazon and Apple are both higher than where they were when they released their first post-pandemic earnings reports a few weeks ago, but not because management announced great numbers. No, to understand what’s really happening here, and to fully appreciate the magnitude of the populist uprising to come, you have to look at the fine print.

What’s happening here is the same thing that happened a decade ago. Back then, the powers that be responded to a crisis that resulted in millions of people losing their job and their home by lowering interest rates and flooding the system with money. They did this knowing that not all of that largess would reach the folks who really needed it. The unemployed and recently foreclosed upon don’t qualify for a loan — at any interest rate. Just because a company is bailed out doesn’t mean it won’t turn around and lay off workers. Subsidizing house prices doesn’t do anything for the millions of people who now have to rent (although it does wonders for luxury condo owners in Manhattan). Helping the rich to help the poor mostly ends up growing the wealth gap. That’s an idea so simple that even an economist should be able to understand it. But alas, that’s giving them too much credit.

The same cycle is now repeating itself, except that this time, everything is happening bigger and faster. Back in 2008, it took most companies years to start taking advantage of the Fed’s lowered interest rates to juice their own shares. Apple was one of the last to introduce the practice because Steve Jobs didn’t believe in it. But this time around, the company didn’t even wait for the ICU wards to fully clear out.

The company just took advantage of the Federal Reserve’s kitchen sink attack on the corporate bond market to issue $8b in bonds — but not because it needs the cash, or is about to go on a hiring spree, or plans to move production back to the U.S., or wants to donate iPads to hospitals. No, the world’s third biggest company by market cap took advantage of the Fed’s “stimulus” in order to reward its shareholders. That’s great news for Tim Cook and Warren Buffet (both billionaires), and the hundreds of hedge funds that own the stock (who by law can only serve millionaires), and your wealthy neighbor who is max long in his retirement account. But you know who it’s not great for?

This is not an accident of history. It’s not a phenomenon that one couldn’t see coming, and it sure as shit isn’t capitalism. It’s history repeating itself. It’s the top down rigging of the economy to a shocking degree. Corporate borrowing costs are supposed to rise during a crisis in order to enforce discipline for the tough times ahead. Higher rates remind management to save and punish those who didn’t. That’s not a bug, it’s a feature. It’s no different than parents who withholds allowance when their kids are slacking at school. It’s for their own good.

But central banks no longer allow this cycle to play out — because the middle class! But if they really wanted to help the middle class (or the unemployed, or healthcare workers, or those who lost a loved one to the disease) they would just help those people. Instead they are doing what they’ve always done, with predictable results. Apple might get to borrow billions of dollars here, but countless small and family-run businesses on the brink of collapse don’t have that luxury. Does anybody have a problem with that? Apparently not.

Sure, there are piecemeal programs designed to help the “little guy,” but the dollars involved are trivial compared to the amounts being gobbled by the behemoths. The Federal Reserve has printed over two trillion dollars in the past few months. To see who didn’t benefit, read the fine print.

Back when I started arguing against these programs a decade ago, the most common argument I heard back was that doing nothing would have led to another great depression. That part I agreed with. At issue wasn’t the act of the government doing something, but rather the policies chosen. I think the justification for action is even more now, because the economic victims of the shutdowns have done nothing wrong. But the issue now is still the same it was back then: free money mostly benefits those who can get it, as opposed to those who actually need it. I was not surprised back then by the fact that such programs resulted in a significant expansion of the wealth gap. But I was surprised by the lasting impact they had on politics.

The one thing the failed leadership of that era had going for it was that it could at least pretend to not realize the consequences of its actions. Today’s leaders have the benefit of hindsight, but heave doubled down anyway. Even more shocking is the fact that belief in this one failed idea seems to be a bipartisan affair. Democrats and Republicans don’t agree on much, but they do agree that the best way to help the innocent is by bailing out the reckless.

For this, there will be hell to pay.

April 21, 2020

Libra is Alive and Kicking (as are its foolish skeptics)

Boy, people really hate Facebook, don’t they? You can see it in the latest round of biased coverage surrounding Libra, including this hatched-job in the FT. The legacy news outlets have always done a poor job of covering crypto, and their Libra coverage has been particularly weak. You could argue that there is a certain logic here, since crypto is a challenge to the notion of ‘important gatekeeper’ which newspapers used to be (and Facebook is a challenge to the profits newspapers used to make.)

That FT article is so one sided that I had to check several times to make sure it wasn’t an opinion column. Even the title, “How Facebook’s Libra went from world changer to just another PayPal” smacks of ignorance. Before getting into why, let’s review the changs the Libra Association just announced:

The focus has shifted from a single “basket coin” to multiple single-currency stablecoins (LibraUSD, LibraEuro, etc) with their own cash reserves. There is now a more sophisticated compliance framework. Most users are expected to access the network via a KYC’ed wallet issued by an authorized provider, and those who don’t (thus accessing the network pseudonymously) will face balance and transaction limits. There will be AML inspections, sanctions blocks, and all of the other oversight that is a staple of the payment industry. The network will remain permissioned forever.

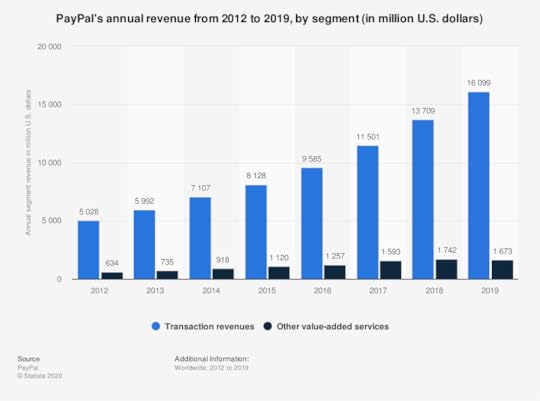

Yes, the project has compromised many of its original ambitions (some of which, like the bakset idea, were dumb to begin with) in order to cowtow to the authorities. But no, that doesn’t make it “just another PayPal.” Anyone who makes a statement like that knows little about stablecoins and even less about PayPal. To wit:

PayPal doesn’t let you program your paymentsPayPal doesn’t let you issue an infinite variety of other tokensPayPal doesn’t give you transparency into it’s ledger (or its reserves)PayPal doesn’t allow non-KYC’ed usage (sorry poor, unbanked or undocumented people)PayPal doesn’t interoperate (not even with Venmo, which it owns!)PayPal doesn’t allow others to build around it or on top of itEven a regulated and somewhat defanged Libra offers features that PayPal does not, will not and could not. But perhaps more important are the things that PayPal does offer but Libra lacks:

PayPal does charge both a fixed fee and a variable fee for every online merchant transactionPayPal does charge an even higher fixed fee and variable fee for cross-border transactionsPayPal does charge even more fees if an account is funded via debit or credit rails.A cross-border PayPal payment can cost merchants upwards of 5% in fees. The same payment on Libra may cost as little as 5 cents. I’ll leave it up to you to decide if an online merchant with $1m in annual sales would like to save $50k. We still don’t know too much about Libra’s fee structure, but if it’s anything like the other stablecoins out there, they’ll be a small fraction of most legacy options.

Blockchain networks have a radically different business model because they use fees to seek security, not rent. There are many consequences to this distinction, the biggest one of which is the fact that blockchain payments are amount-agnostic, so a $1000 payment costs the same as a $1 one. Transitioning to such a model would impair the revenue growth of any payment network. Blockchains have the luxury of not caring about revenues.

Now, can Facebook or the Libra Association still try to charge PayPal like fees if they wanted to? Sure. But that will just aid the adoption of Tether, USDC and Dai. Although the economics of joining the Libra Association remain murky, it’s unlikely any of the existing members are expecting PayPal like profits.

source: statista.com

source: statista.comIf anything, companies like Uber and Shopify joined to try to force payment revenues down across the board, to reduce costs. Uber reported in its IPO filing that it spent $750m on credit card processing fees in 2017. That number is probably north of $1B today. The one thing legacy payment providers and FinTechs (and their investors) never seem to appreciate is that their revenues are the rest of the digital economy’s expense. The more payment-related revenues grow, the greater the incentive for the rest of the world to find an alternative. (Enter stablecoins, stage left.)

Tellingly, a lot of the shade being thrown at Libra in the FT article comes from the crypto community. One reason why stablecoins keep being ignored — despite their potential and continued growth — is because they are unsatisfying to both ideological extremes. Not as proprietary as PayPal, but also not as decentralized as Bitcoin — the technological equivalent of whatever idea doesn’t get much coverage on MSNBC or Fox News. That’s how we know they are a good idea.

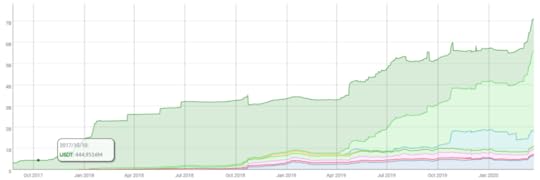

Coinmetrics chart of stablecoin growth on Ethereum

Coinmetrics chart of stablecoin growth on EthereumThere is much that remains to be seen about Libra. But the recent update reveals that the project hasn’t just gone into hibernation as many had hoped. There are also rumors of association members having finally made a financial commitment. But even if the project never launches, it has done a lot of the heavy lifting to pave the way for a stablecoin future. Some of its most recent innovations, such as throttled non-KYC’ed accounts, will probably be adopted by others, including central banks rushing to issue CBDCs.

Notably, the project’s new white paper directly invites central banks to issue digital currencies into its network to eliminate the need for a reserve altogether. If you are a PayPal executive, that’s the kind of development that should keep you up at night.

The opinions expressed here are strictly my own and not that of any client, associate or employer.

April 17, 2020

Consequences of the Crisis, Part II: Digital identity to the forefront

source: https://privatemedcreds.com/

source: https://privatemedcreds.com/In part 1 of this series, I identified the politicization of digital payments as one blockchain-related consequence of the ongoing crisis. Number two on the list is how the crisis will accelerate the need for true digital identity. No lesser an authority than Bill Gates commented on this in a recent Reddit AMA. Asked about the changes the business world would have to make to accommodate social distancing, he said:

“Countries are still figuring out what to keep running. Eventually we will have some digital certificates to show who has recovered or been tested recently or when we have a vaccine who has received it.”

What he was referring to was the fact that to bring the economy back online while preventing another flare-up of the virus, governments will have to figure out an efficient means of authorizing who is allowed to be where. This may include essential workers, those who’ve recently tested negative and those who are demonstrably immune. The simplest way to do that is via digital identity, but there are two conflicting approaches to providing it. To understand how they differ, we need to review some history.

The internet has always had an identity problem, best understood through the lens of how identity used to work. Back in the pre-web era, your identity was established by a series of physical documents. They were issued by governments (your driver’s license) and corporations (your bank statement) and organizations (your college degree).

Proving your identity, or some aspect of it, was done by presenting those physical documents in person. The most important ones included a picture to make authentication easy. For greater assurance, the verifier may have reached out to the issuer to confirm authenticity. The system wasn’t perfect, but worked well enough. Security was provided by the fact that people are difficult to impersonate and physical credentials are hard to forge.

That internet challenged that model because digital presence is easy to spoof and digital documents are easier to counterfeit. The first solution to this problem was the clunky username and password (and your mother’s maiden name, and your Authenticator code…) login method we’ve all grown to hate. It’s not secure and doesn’t scale, so something better was needed.

That something turned out to be the federated approach. Instead of establishing your identity with every website independently, you establish it with a single online authority who has built the infrastructure to share your info with others and provide some level of attestation upon request. So long as you trust the purveyor with your sensitive data, only a single login would be needed. Federated ID sounds like a solid solution on paper, until you realize that one of the largest providers is Facebook.

There are other, less shady providers of a “login with XYZ” solution, and various industry consortium and even governments are rolling out their own versions, but the fact remains that all federated solutions require users to surrender personal information to a third party. At best, they only occasionally abuse the privilege and slightly monetize your data. At worst they get hacked and spill everything. The incentive structure is all wrong, and the more popular a federated solution becomes, the more likely something bad will happen.

Blockchain technology enables a third way. There is still third-party infrastructure for the sharing of digital credentials (in the form of a distributed ledger) but its only function is to authenticate the source and originality of a credential. The actual data of that credential (address, credit score, etc) is stored inside your mobile wallet and shared with the recipient of your choosing in P2P fashion. That’s why blockchain-based digital identity is referred to as “self-sovereign identity”, or SSI. There is no data play for a corporation or honeypot for hackers. The ledger is transparent, but its data is useless to anyone other than the two parties involved.

This brings us to the present, where most people agree that some kind of digital identity solution is very much needed. The question is which approach. The centralized federated approach or the decentralized self-sovereign one?

Ironically, the best thing the more advanced blockchain-based solution has going for it is how much it resembles the pre-internet way of doing things. There was no need for any third party when the DMV would mail you a license that you’d use to get into a bar. SSI works the same way, but substitutes a digital wallet for a physical one and a blockchain for the unique plastic and the hologram. SSI also enables new features that the physical model didn’t, such as revealing your DOB to the bouncer without revealing your home address.

The federated solution on the other hand requires an additional intermediary for storage and sharing. There is no old-world analog to this approach, other than perhaps the credit bureaus in the US, and we know how that went.

I am very much in favor of the SSI approach. It respects the importance of issuing authorities (like the DMV, or a medical test center) but eliminates the dangerous middle layer that only exists due to the inherent flaws of the web’s architecture, flaws that are now being addressed with blockchain tech. There is already a sophisticated SSI community in place, and its members have rallied to respond to this moment. There are also cool startups such as MedCreds building easy to use end to end solutions to empower this approach.

But I fear that society is not ready. Decentralization still scares people in too many ways that it shouldn’t, and the back-end infrastructure hasn’t been battle tested enough. What’s more, there’s something about a pandemic that scares everyone into the arms of the big and powerful — like the mega tech companies that are dying to get their hands on all of our data, including our medical data. They’ll say the right things about privacy and protection, just as they have been for years. Then they’ll break those promises (just as they have been for years).

The resulting backlash might be just what the SSI community needs to make its case. Either way, the need for digital identity will now be thrust into the limelight.

The opinions expressed here are strictly my own and not that of any client, employer or associate.

April 10, 2020

Consequences of the Crisis, Part I: Digital Cash Becomes a Political Issue

This is the first of three posts exploring blockchain applications that I believe will see accelerated adoption due to the ongoing crisis. None will arrive fast enough to impact the pandemic, but all will be in consideration for dealing with the aftermath. Crises have a way of changing society’s priorities.

One of the more underrated news items of not that long ago was New York City joining San Francisco in banning cashless business. It revealed the blow back against one of the most commonly held beliefs in finance and tech, that all payments will eventually be digital and handled by an ecosystem of for-profit banks, card rails and Fintechs.

The first problem with that thesis is that it doesn’t account for tens of millions of people who exist outside of the banking system and would therefore be locked out of a cashless economy. The second problem is that it assumes society would be fine paying an effective tax on every single transaction in the form of fees.

Both issues were thrust into the spotlight when Libra was announced. Although many disagreed with Facebook's solution, few disagreed with the stated problem: fees on payments are usually borne by the least privileged among us, including migrants, the poor, gig economy workers and small businesses. The controversy over Libra's proposed solution created an explosion of interest in so called central bank digital currencies, or CBDCs.

Central banks are already important in payments, both via the banknotes (aka cash) they issue and due to the national payment infrastructure (check clearing, RTGS) they operate. Notably, these systems are either free or operated at cost — unlike corporate digital payment solutions, whose fees create economic distortions, such as delis with minimums for card purchases and gas stations that charge more for credit. There are also non-financial costs to private payment solutions, such as privacy and mass data collection.

A tokenized cash equivalent (aka stablecoin) such as Libra is a partial solution. Although still privately issued, stablecoins have a different business and data model, which is why they are often designed as loss leaders. No stablecoin provider will ever be as profitable as PayPal, and that’s the point.

A general purpose CBDC goes as a step further, because unlike with a stablecoin, users don’t have to worry about the adequacy of the reserve. If the Fed were to issue a tokenized dollar on some blockchain and declare it legal tender, then it would be as valuable as a physical dollar bill. Fees would be minimal if any, so the entire economy would get an effective tax break.

The covid crisis has exposed our current system’s inability to get money where it’s needed quickly. Digitally native companies have offered to help, but there are thorny questions of how. Would these companies be willing to waive the fees and data collection that are core to their business model? If not, would society be OK with some percentage of the stimulus money flowing not to those who desperately need every penny, but to Silicon Valley companies? The answer, according to some in congress, is absolutely not, so they proposed an alternative.

Found in earlier drafts of the stimulus bill (but taken out before passage), that solution called for commercial banks to operate so-called “narrow banks” that would process stimulus payments at a loss, and for the Fed to open up its balance sheet and payment system to the general public — also known as a retail CBDC. One solution would be a money loser for commercial banks while the other would greatly disrupt the payments industry.

My thinking on this subject has evolved since I first proposed the disruptive potential of stablecoins a few years ago. My core thesis can be found here, and is summarized as “stablecoins will do to payments what Skype did to pay-per minute phone calls.” I’m now expanding that thesis to include a political imperative. The crisis requires countless injections of cash by the government, and the notion that mega financial firms or billionaire tech bros should profit as a result is distasteful. I have nothing against private companies earning a profit, but now there is a technology that affords society the same outcome for free.

The congressional digital dollar proposal has nothing to do with blockchain, and most central banks looking into CBDCs are as open to using traditional account-based solutions as they are to tokens. But the former just isn’t as good. A distributed ledger is more resilient than a non-distributed one. An immutable ledger is preferable to an editable one. Private-key based transactions are more secure than identity-based ones. Programmable money is superior to non-programmable money. Both account-based and tokenized CBDC solutions use ledgers, but blockchain is better ledger technology.

As the economic fallout from the current crisis unfolds, the need for better, faster and cheaper payments will become a hot-button issue. That will drive a lot of innovation, but those hoping to extend the old way of doing things will now encounter political push back. If digital payments are viewed as a public good, then stablecoins win out.

The opinions expressed here are strictly my own and not that of any client, employer or associate.

February 29, 2020

Why crypto bulls may not want it to be a safe haven

cointelegraph.com

cointelegraph.comAll eyes were glued to the quote screens this past week to see how crypto would react to the virus-inspired selloffs in other markets. Many were hoping that Bitcoin would finally show off its bonafides as a “safe haven” or flight to quality asset — something I myself have wondered about in the past. But crypto mostly tanked alongside everything else.

There are two ways market watchers are interpreting this. Some observers now (disappointedly) think that crypto is just another risk-on asset, to be sold during a crisis. Others still think it’s a safe haven, and point to the fact that gold fell this past week as well (there is some precedence of precious metals falling during the peak of a crisis, then rebounding strongly. Make of that what you will).

My hunch is that it’s neither. Crypto is mostly doing its own thing. Too few big players own any of it, or even consider owning it, for it to be caught up in the usual “risk-on, risk-off” calculations. Asking the average Wall Streeter what happened to Bitcoin while the Nasdaq was tanking is sort of like asking them what happened to the Mexican Peso. Most traders probably weren’t even thinking about it. More importantly, I wonder whether crypto investors should want their preferred investment to be a flight to quality asset. I certainly don’t.

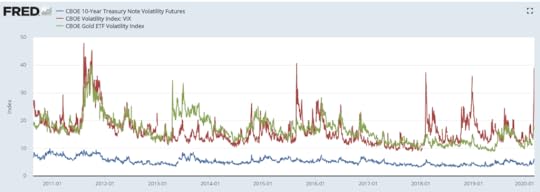

My belief is based on volatility: To be a safe haven, an asset needs to be less volatile than the thing investors are fleeing. This is as much a mathematical truth as it is common sense. The reason why you’d rather own treasuries or gold during a market crash is because — regardless of the market mood — they usually don’t move as much as Tesla. You can see what I mean in the following chart of the implied volatility of stocks, treasuries and gold.

Although their relative vols tend to be correlated, one is almost always much higher than the other two. Bond volatility actually spiked to a multiyear high last week, but it was still less than a quarter of stock volatility.

Crypto volatility doesn’t even register on this chart because it’s an order of magnitude higher. That alone disqualifies it for proper “safe haven” status. Case in point, the price of Bitcoin rallied by over 50% in the two months prior to this week, with alts rallying even more. Nobody wants something that can double that quickly as their store of value. Things that go up quickly can come down just as fast.

So in order for crypto to become a true safe haven, its volatility would have come down drastically. This is not something hodlers should want. A less volatile asset is one that by definition has less potential upside. To put it in industry slang, less vol equals much later moon.

Gold, which is historically a reliable tore of value, has had an impressive rally over the past five years, climbing by 44%. If Bitcoin were to follow the same trajectory, it would barely break above $12,000 in the year 2025 — still 40% below its previous high. How terribly disappointing that would be for most investors

So as far as crypto’s safe-haven status is concerned, be careful what you wish for. There are still many risks and unknowns to owning these things, so investors should expect disproportionate upside as their reward. This is even truer given crypto’s backwards volatility profile. Unlike stocks, bonds, gold and almost everything else — cryptocoins are more volatile during bull markets than bear ones. The current five year high realized 30 day vol in Bitcoin was recorded right around the time of the late 2017 peak. The low came 11 months later as she was making her 2018 lows.

https://www.bitpremier.com/volatility-index

https://www.bitpremier.com/volatility-indexThis begs the question: if not risk on vs risk off, what drives crypto prices? It’s still too hard to know for sure, but my guess is that the performance of relative market infrastructure matters more than relative asset prices. There are now two competing models for a financial system: the legacy one, which emphasizes centralized control by large commercial entities whipped around by their central banking overlords, and the newer one, which emphasizes decentralized protocols driven by a global community.

My admittedly non-mathematical correlation analysis shows changing perceptions about how value is best moved around are the biggest drivers of crypto valuations. When the old way fails its users, as was the case during the great financial crisis that launched Bitcoin, the Cypriot bail-in that lead to the 2013 highs or more recent Chinese capital controls, crypto goes up. When the new way shows its own problems, like the Ethereum DAO crisis of 2016, or the contentious Bitcoin Cash split that marked the 2018 lows, crypto goes down. Ironically, the biggest gains have happened when the stalwarts of the old guard bless the new way, like when the CME announced Bitcoin futures in 2017 or Facebook launched Libra in 2019.

If this analysis holds true, then the question crypto longs should be asking is not how stocks or bonds will do as the Coronavirus situation unfolds, but rather how the legacy financial infrastructure holds up during this period, and just as importantly, the ensuing response.

My prediction is not so good. The current attitude towards easy money from the world’s central banks reminds me of what Homer Simpson once said about alcohol: it’s the cause, and cure, of all of life’s problems. All of the instabilities that have built up from a decade of easy money — like an insane debt load in China or the destruction of commercial banking in Europe — are about to be pushed to a new extreme. It might take a few years to play out, but it won’t end well, increasing the appeal of an alternative

There’s also the possible catalyst of a central bank digital currency using some kind of blockchain infrastructure, an event made more likely by a scary contagious disease. If you believe in the price impact of blessings by the old guard, then it doesn’t get any better than a tokenized CBDC, a friendly blink from the Eye of Sauron himself.

The ideas expressed here are strictly my own and not that of any client, employer or associate. If you aren’t sure whether you should invest in crypto, then you probably shouldn’t.

January 8, 2020

Here Come the Private White-Labeled Stablecoins

When it comes to stablecoins, 2019 could be remembered as the year of the big bang project that wasn’t — or at least, isn’t yet. That sets up 2020 to be the year of the little whimper that will. Projects like Libra, JPMC and USC generated a lot of attention, but are still nowhere to be seen. Some of the blame goes to the over ambitiousness of those initiatives. Some goes to the challenges of forcing something new into a regulatory framework designed for something old. A lot goes to the irrational overreaction by the powers that be, many of whom never took the time to understand the difference between Libra and Litecoin, and more than a few (cough cough central bankers) who are a bit too regulatory-captured to be objective on disruptive tech.

Either way, nothing is live, and it remains unlikely that any of the Big Stablecoins will launch at full scale. But the overall thesis, as I’ve written before, has been validated. All of that fear mongering carried a subtext of “this technology clearly works, and that’s why we fear it!” That opens the door to less ambitious but easier to launch white-labeled stablecoins for niche applications. They could be issued on public or private chains (the distinction is not as big of a deal for cash-backed tokens given the required KYC bridge to the outside world) and created by banks, payment companies, legacy tech players or crypto startups.

They will mostly likely be domestic and B2B at the outset to minimize regulatory headaches. Some will solve blockchain-native problems, such as instant settlement for security tokens, but most will focus on industry-specific needs, like an insurance company paying subsidiaries, an industrial conglomerate paying suppliers, a franchiser interacting with its restaurants, a shared-economy platform paying service providers, a legacy capital market platform trying to speed up payments, a supply-chain looking to more directly integrate credit issuance, and so on.

They will not be nearly as sexy as Libra, but they will still be transformative. They won’t solve all the headaches because recipients will still have to rely on traditional rails to cash out their coins, but they’ll solve the biggest headache of all: the need to freaking pay someone right now.

Here, we can take a moment and call a spade a space. For all of the great progress made by the payments industry in the past decade, it still lags the rest of the internet. Just ask any corporate treasury official who has tried to make an important payment on a Sunday afternoon in August. The email confirmation that a payment has been issued travels instantly, but the payment itself does not. Sometimes it takes minutes, other times hours or days. This distinction should not be, since a payment, just like an email, is nothing more than data. But it’s not, and the complicated reasons why one type of data travels instantly and another might take 3 days is not the treasury officials problem.

The payment guru will hear this argument and say “Oh but look at SWIFT GPI, half of all payments are now credited within 30 minutes!” Yes, that’s true, and 56k modems were a huge upgrade over 28.8 — just ask your parents (also, what happens to the other half?) For the record, GPI is indeed a fantastic upgrade, one that took a herculean effort to pull off globally. But it’s an extension of the old architecture. You can only squeeze out so much efficiency from a network constructed half a century ago until the world moves on to something new, and that something is stablecoins.

Aside from instant payments, PWLS (private white-labeled stablecoins — the payments industry loves acronyms) offer other useful features, such as instant tracking by all parties involved, an immutable audit trail, programmable payments (so that Treasury official doesn’t need to be in the office Sunday afternoon), invoicing on the same platform, and multiple other features. You can get all of those things already, but you can’t get them on the same platform using just a few lines of smart contract code. PWLS also provide guaranteed delivery, because that’s what decentralized networks do.

Banks, particularly ones who specialize in payments, should be on the forefront of the PWLS movement. Unlike certain payment oriented Fintechs, many of which rely on the fee-based model stablecoins eschew, banks use payments as a source of cheap deposits. Not only does that model not change with stablecoins, it’s improved by it. If you are a supplier getting paid with a stablecoin, the fastest way for you to cash out is by having an account at the bank that custodies the cash backing it. Banks offering PWLS can gain entire ecosystems as customers, and that in turn will empower them to offer additional features — including stablecoin-based credit.

The critic will hear this argument and say “but wait a minute, can’t a big enough bank offer that already? If a company and its supplier are both customers of the same bank, can’t they already make instant payments day and night?” The answer, like most things inside financial services, is yes, but only in theory. Most of the systems inside most banks were either built, or at least architected, long before the internet was a thing. They can only be pushed so far, particularly inside the most regulated industry on earth.

Stablecoins represent a leapfrog opportunity. Big Stablecoins are the ultimate manifestation of that opportunity, but they’ll take time to roll out. PWLS are the happy medium. They are best thought of as a cost-effective outsourcing of internal infrastructure, sort of like cloud computing. The fact that banks can either issue their private coin on a public network like Ethereum or Stellar, or deploy their own permissioned one using free open-source protocols, makes the idea even more appealing.

Back in 2018, I made several predictions that stablecoins would soon be a big deal in payments, and challenge the likes of PayPal. I was both right and wrong. Last year saw a ton of new announcements, but nothing is in production, which means no actual disruption is taking place yet. Having learned a lot more about the payments universe in the interim, I am altering that belief to accommodate the fact that long before Big Stablecoins have any noticeable impact, PWLS will start to be used all over, and in certain cases actually enhance the position of legacy payment providers.

(until Dai changes everything)