Sean Poage's Blog

October 10, 2025

Arthur’s Siege of Nantes

Today we talk about Arthur’s Siege of Nantes, the first major battle of King Arthur’s campaign in Gaul. My previous articles, ‘King Arthur’s European Campaign‘, has an overview of the history and legend behind this campaign, while ‘Why Did Anthemius Ally with the Britons?‘ and ‘King Arthur’s Strategy for Gaul‘ have more details behind the historical politics and strategic challenges Arthur would have faced.

As you may know, I do not alter history to fit my stories. I must find the story that fits history. Where the history is missing, I look for clues to fill in the blanks. The details of this post are mostly speculative, based on historical clues applied to my own military experience and education, and framed as depicted in my books. There aren’t any specific mentions of Arthur attacking Nantes in history or legend, but I have some very good reasons for thinking it must have occurred, which I will explain below. First, let’s dig into the historical details about Nantes in Arthur’s time, and the Arthurian references in legend.

NantesNantes began as a town built by the Romans in the Gallic Celtic tribal region of the Namnetes, from which comes its current name. They named it Condevincum, a Latinization of the Gaullish term “Condate” (“confluence of two rivers”). Later, it became Portus Namnetum before evolving to Namnetis in the 5th century. Suffering from Germanic raids, they built walls around the city in the 3rd century.

Skipping forward to the later medieval era, the father of Arthurian Romance, Chrétien de Troyes, described Arthur choosing Nantes for Erec’s coronation site as king of Outre-Gales, a fictional kingdom of confused whereabouts. In the 13th century vulgate Story of Merlin, Nantes is described as being fortified against Saxon attacks during a rebellion against King Arthur. This is one of the infrequent instances where an Arthurian Romance may actually carry a hint of ancient history, as we shall see.

Nantes was not a very important town in the Roman scheme. But with the influx of Britons fleeing barbarian invasions of Britain in the 5th century, it became a principle city and eventual capital for Letavia, the region that would become Brittany. Legend and history suggest it was important to the war looming between Rome and the Visigoths, and this is where Arthur comes in. According to Roman records, the River Loire (the Leger) was controlled by Saxons (the name generally applied to all sea-going Germanic tribes by the Britons and Romans) up to the town of Angers (Andecava). Yet, Riothamus (Arthur) came by sea to the the land of the Bituriges, the region of Bourges, France. The only way for Arthur to arrive near Bourges by sea would be by ship up the Loire, at least as far as Tours (Turonis). He would have to pass Nantes.

Arthur’s ChallengesIf you have read my previous article, ‘King Arthur’s Strategy for Gaul‘, you’ll recall that Arthur, Syagrius and Anthemius devised a plan for Arthur to establish a foothold in Visigoth territory, specifically at Poitiers (Pictavis). The best route of supply would be the major Roman road between Poitiers and Nantes, but the bridge was destroyed, and the Nantes was in Saxon hands. The Saxons of the Loire were led by a warlord called Odoacer. If that name sounds familiar, it’s because Odoacer is also the name of the Germanic warlord who ended the Western Roman Empire in 476 and became the first King of Italy. Many, including myself, think it is the same man.

Coin of Odoacer with his “barbarian” mustache, 477 AD

Coin of Odoacer with his “barbarian” mustache, 477 ADGregory of Tours said that Odoacer received hostages from Angers, about 55 miles upriver from Nantes. This suggests that Angers was not held by the Saxons, but that Odoacer was enough of a threat that the city cooperated with him. Arthur thus had to worry about a second city if he were to take control of the Loire. Additionally, the Saxons were notoriously difficult to pin down, as the Gallo-Roman politician, Sidonius, describes to a friend:

Look-out for curved ships: the ships of the Saxons, in whose every oarsman you think to detect an arch-pirate. Captains and crews alike, to a man they teach or learn the art of brigandage; therefore let me urgently caution you to be ever on the alert. For the Saxon is the most ferocious of all foes. He comes on you without warning; when you expect his attack he makes away. Resistance only moves him to contempt; a rash opponent is soon down. If he pursues he overtakes; if he flies himself, he is never caught. Shipwrecks to him are no terror, but only so much training. His is no mere acquaintance with the perils of the sea; he knows them as he knows himself. A storm puts his enemies off their guard, preventing his preparations from being seen; the chance of taking the foe by surprise makes him gladly face every hazard of rough waters and broken rocks.

Sidonius Apollinaris, Letters

Not only did the Saxons have a walled stronghold at Nantes and a cooperative city at the end of their reach, but many hideouts and havens among the islands and shore all along the Loire to the sea. To secure his lines of communication and supply, Arthur would have to clear the Saxons entirely from the Loire valley. A daunting task, but any good general looks for ways to turn problems into advantage.

Spoilers AheadIf you haven’t read The Retreat to Avalon and want to avoid spoilers, you might want to pause here and read at least through chapter nine. The Retreat to Avalon is told through the eyes of Gawain, who, as a minor officer, only sees Arthur’s plans as they unfold. The following describes Arthur’s overall strategy, from the beginning of his planning, to the capture of Nantes.

In chapter 8, Gawain and his men board ships to sail to Letavia. This is the last shipment of Arthur’s army. For months he’s been collecting soldiers and supplies and shipping them to a staging camp at Aletum, near modern Saint-Malo on the northern coast of Brittany. It would be nearly impossible for this sort of military buildup, over months, to go on without notice, even in this era. Merchants, peasants, clergy and spies all carried news and rumors. Originally, Arthur gave the impression that his goal was only to clear the Loire valley and return Nantes to the control of his friend, Hoel of Comberos (Quimper, France). The alliance with Rome was still a secret. This secret would come out before Arthur was ready, but that’s a story for the next post. It had little effect on Arthur’s plans for Nantes.

It would be a tough fight just to clear the Saxons out of the Loire’s islands. Taking a walled city was a whole other issue, but Arthur’s biggest problem was time. He had to deal with Nantes quickly to move on his next target. The usual way, a siege, was out of the question. But the Saxons didn’t know that.

Today we tend to think of ourselves as far more sophisticated than people of the past, but digging into history will change your mind. We don’t hear much about the use of spies, disinformation and scouting because it was not the focus of historical records. But as my article, Espionage in the Arthurian Age explains, it was always a factor. I doubt Arthur would have been as successful a commander as legend describes if he didn’t make use of all tools, so in my series, espionage plays a major role.

Information gathering is one of the more important aspects of war planning. Throughout The Arthurian Age series you may note hints of this sort of espionage. There is an underlying factor that I won’t reveal yet because of overall spoilers, but you might pick up the clues. To deal with Odoacer, Arthur used his resources from the beginning to get an estimate of Saxon numbers and locations. He was already very familiar with their tactics and tendencies, and he would make his plans accordingly.

Romano-British Soldiers from Arthur’s Era

Romano-British Soldiers from Arthur’s EraOdoacer and Arthur were both skilled generals who looked for ways to choose the fight they preferred. Odoacer had the significant advantage of defence, but Arthur had some advantages of his own, such as the locals who wanted the Saxons gone as well. Additionally, around any army there develops an even larger ecosystem of non-combatants. Wives and children, merchants, tradesmen, prostitutes, entertainers, beggars, swindlers, and enemy spies. While providing conveniences, services and distractions to the often ornery soldiers, they generally caused more problems than they solved, particularly in slowing an army’s progress. However, they had to be tolerated as much as possible to pacify the army, and Arthur found a way to use them to his advantage, as he described to Gawain:

Arthur chuckled. “Even when we wanted our men to talk, you were silent.” Noting Gawain’s puzzled look, Arthur added, “Gossip, within any army, is the most efficient way to spread news known to mankind. From the beginning, we’ve harnessed this resource by giving out bits of misinformation that we wanted the enemy to learn and believe. If all our men were as tight-lipped as you, our plans would never have worked.” Arthur shook his head with a wry smile.

The Retreat to Avalon, Chapter Nine

If you recall, throughout the story there are references to rumors and gossip. When I was in the army, we joked it was an official office, “Rumor Control”. Soldiers rarely know the big picture, so every scrap of information is analyzed, spread, re-interpreted and twisted as they try to guess the future their leaders have planned for them.

Chess MovesOne of the main rumors that Arthur encouraged was that he had siege engines recovered from Roman armories at Saxon Shore fortresses. This was vital because it changed the way Odoacer would have to defend Nantes. Odoacer had about 5,000 warriors. Not enough to face Arthur’s army openly, but plenty to defend Nantes in a long siege. However, Odoacer knew he couldn’t hold the city if the walls or gates were breached by Arthur’s siege engines. As Gawain would later learn, the siege engines were so old and poorly maintained that they were unusable, yet Arthur made it appear that they were working and carted them to Nantes. Arthur’s ploy pushed Odoacer into looking for a way to trap the Britons. Arthur knew the only likely option Odoacer had, and his spies confirmed Odoacer would use it.

Odoacer would expect the Romanized Britons to follow normal Roman army practice, marching down the Roman road from Rennes (Redones), and building a protective ditch and palisade to protect the siege equipment from attacks from the city. If the Britons really followed Roman procedures, they’d follow that with a second, outer, defensive ditch and palisade to protect against attacks from any Saxon relief forces. Odoacer planned to intervene before that could happen.

Nantes battlefield upon Odoacer’s arrival

Nantes battlefield upon Odoacer’s arrivalOdoacer’s advantage lay in the mobility of his Saxon ships and their control of the river as far as Angers. The walled city of Nantes lay on a peninsula formed by the confluence of the rivers Loire and Erdre. He needed to ambush the Britons.

When news came that Arthur’s army was moving south, Odoacer left about a thousand men in the city and packed the rest into their ships, then sailed upriver to wait near Angers. When the Britons arrived and started their siegeworks, he’d sail quickly downriver and attack the Britons from behind, pinning them between his Saxons in Nantes, and those landing by ship. If things went bad, he had only to retreat to his ships and fight another day as Nantes withstood the siege.

This is what Arthur counted on. He had disguised his numbers by moving people in and out of camps, and had more than enough men to defeat the Saxons, but only in open battle, and only if he could pin them down and prevent their escape. His plan to draw as many Saxons out of Nantes as possible worked. Now he had to keep Bedwyr from being surrounded, and prevent the Saxons from escaping. This is where Arthur’s next bit of trickery came in.

The rumors of the army preparing to move began to swirl as Arthur and the last of the army arrived at Aletum. Gawain wasn’t there long before he and the other cavalry members were rousted late at night and led on a secret forced march about twenty miles east to the isolated cavalry camp. Here they learned Arthur’s plan, and their place in it.

Bedwyr would be leading the majority of the army south to Nantes. It would move slowly, pulling the heavy siege equipment, supplies, spare horses, and the infantry. It would be reported immediately to Odoacer, who would sail upriver to Angers. As Bedwyr plodded southwards, Cei would lead Arthur’s cavalry along a different, hidden route, guided by locals and fed by pre-positioned supplies. They would hide in a wooded valley overlooking the Loire, about 8 miles east of Nantes (near present day Mauves-sur-Loire). When they spotted Odoacer’s fleet sailing south to Nantes, the cavalry would wait until they passed, then ride out after them. Odoacer, expecting to pin the Britons between the walls of Nantes and his army would find himself pinned between Bedwyr’s infantry and Cei’s cavalry. Bedwyr’s fortification wasn’t to protect the siege engines, it was to keep the Saxons in the city from coming to Odoacer’s aid when the trap closed.

Travel routes of the armies: green for the Britons, red for the Saxons.

Travel routes of the armies: green for the Britons, red for the Saxons.Brown are Roman roads.

There was still one more key to success. The Saxons must not escape. Before Bedwyr marched, Arthur had already set sail with his fleet around Brittany for the mouth of the Loire. He would ensure no Saxons remained downriver from Nantes, and that none escaped by ship when the battle commenced. During the build up, Arthur had also been quietly sending groups of skirmishers to the west under the command of Drustan. Their job was to make their way secretly to the west of Nantes and wait until Odoacer’s ships had arrived to try and trap Bedwyr’s army. With the Saxons distracted, they would fire the Saxon ships that remained on the western side of the city, sowing confusion amongst the Saxon defenders, and the smoke would alert Arthur that the battle was fully engaged. Arthur would then bring his fleet the rest of the way up the Loire to Nantes, intercepting any Saxons that tried to escape.

If you’ve read The Retreat to Avalon, you know how that turns out. We’ll talk about the results, the fallout, and what came next on the next post. For now, thanks for coming by, I’d love to hear comments and questions, and please remember to help authors by simply leaving a rating or review for their books!

The post Arthur’s Siege of Nantes appeared first on Sean Poage.

September 5, 2025

King Arthur’s Strategy For Gaul

It’s time to get back to the story line. Today, we’ll talk about King Arthur’s strategy for his campaign in Gaul. My previous short article, ‘King Arthur’s European Campaign‘, has an overview of the history and legend behind this campaign, and the article, ‘Why Did Anthemius Ally with the Britons?‘, discusses why the Roman Emperor would want to ally with King Arthur in Gaul.

Now, why would Arthur want to join the Romans in a war in Gaul? We can only guess at the reasons he would do this. I use the historical and legendary hints as the background for the novels of my series, The Arthurian Age. In short, it may have been equal parts altruism and hubris. Arthur was revered as the leader who led a resurgence of the Britons against foreign adversaries. Perhaps the success went to his head. Perhaps he saw it as a way to ensure the long-term security of Britain. The upcoming third novel in the series, Three Wicked Revelations, will delve into this question.

I wrote The Retreat to Avalon largely to explore the practical application of the theories behind the research of the eminent historian, Geoffrey Ashe, and focused on the core of the premise: the war in Gaul with the Visigoths. I found Geoffrey’s thesis entirely cogent, but having been involved in wartime operations, I wondered about the strategic, tactical and logistical problems that would be faced by a military leader in the 5th century. Was such an expedition even possible? What decisions led to the locations and events?

As you may know, I stick to history as we know it when writing my novels. The lack of direct proof of Arthur and his activities makes it impossible to know for sure if any of what I describe may have happened. But there are references to draw from history, and the legendary stories may have correlating hints. The rest has to be conjecture, but it must be plausible conjecture that doesn’t go against known history. So for the purposes of this article, we’re going to assume that King Arthur existed, that he was known as Riothamus to the Romans, and that the Battle of Déols was between Arthur and Euric, King of the Visigoths.

Sometime around 468 AD, King Arthur, basking in a British resurgence, gets a letter from the Roman Emperor, Anthemius, asking for an alliance against the Visigoths in Gaul. Arthur agrees to the alliance, and now has to develop a strategy for success in Gaul.

The SituationAt home the Britons are enjoying a measure of relative peace won after decades of bitter struggle. The Irish and Picts have given up on major incursions and only engage in minor piracy and occasional small raids. The Anglo-Saxons, while not pushed out of Britain, have been cowed to the point that their expansion has been stopped, and in many places reversed. Arthur believes that Britain is secure enough for him to mount a foreign expedition, as long as the British nobility don’t fall back into their quarrelling ways.

His ally, the Roman Empire, is a mess of political infighting, assassinations, and struggles to hold its borders. The eastern empire, under Leo I, isn’t always in synch with the western emperor, currently Anthemius. Both halves deal with high-level generals and politicians who have their own agendas that often are in conflict with their emperors’. The Eastern empire will be a source of trade and money, but no military help. Anthemius has promised money and an army to join Arthur.

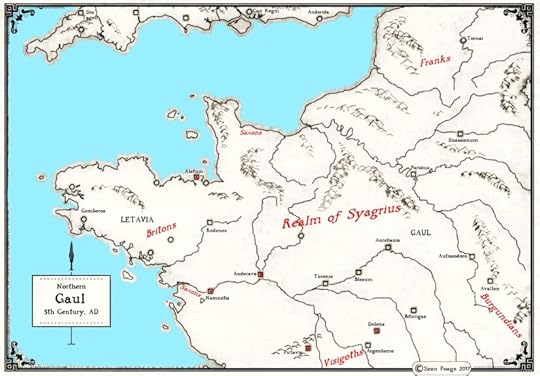

Even though the empire still claims Gaul, it is effectively out of Rome’s control. The Visigoths control Spain and southern and eastern Gaul up to the the Leger River (the Loire). Saxons control the city of Namnetis (Nantes) and the River Leger from the Atlantic nearly to Andecava (Angers). They also have settlements on coastal Armorica (around present-day Normandy).

Northern Gaul, including Armorica, is under the control of the barely-competent Syagrius, who became ruler after his father’s mysterious death a few years earlier. Though effectively independent, Syagrius is considered a Roman governor and promises to help Arthur. However, he has made a risky alliance with his Frankish neighbor to the north, Childeric I, and it remains to see what comes of that.

Spoiler: History finds it a decision Syagrius will regret.

Letavia (Brittany), on the westernmost tip of Armorica, is essentially an independent region of small British colonies loosely tied to the noble families of Britain. It doesn’t have enough of a population to draw an army from, but it is a reliable foothold in Gaul.

Western Gaul is held by the Burgundians, a Germanic tribe that Rome settled in the region as allies when they couldn’t be kept out of the empire any longer. Gundioc, their king, is friendly but unwilling to engage in war with the neighboring Visigoths.

North of Gaul, the Franks are growing in power. Arbogast controls the Roman city of Treveris (Trier), and while he claims to represent Rome, he is essentially independent and struggles to maintain his realm against the Franks and other Germanic tribes. He’s unlikely to be any help or hindrance.

The MissionAnthemius is trying to bring parts of the western empire, lost to Germanic tribes, back under empire control. His joint expedition with Leo to retake the rich grainfields of North Africa from the Vandals ended in disaster, so he turned his eyes towards the Visigoths. Alternately allies and enemies, the Visigoths have essentially taken over Spain and Southern France. They claim to be vassals of Rome, but act independently and continue to expand their control, taking over eastern Gaul, nearly up to the Leger. To re-assert Roman control in Gaul, Anthemius wants Arthur to establish a foothold in the region south of the Leger, where both Visigothic and Roman control is thin. Arthur should try to avoid a major military confrontation with Euric until Anthemius and Syagrius are able to send reinforcements.

Execution, Support, and CommandArthur estimates he can raise, supply and move an army of about 12,000 soldiers. A large army, but not out of the question for the era. This would be sufficient to gain his foothold and wait for the Romans to join him. Arthur figures he can get most of the troops by using his position as High King of the Consilium to beg, barter or bully the other rulers of the Romano-British kingdoms. This is also an opportunity to build alliances with the northern British kingdoms that are not members of the Consilium, namely Berneich, Alt Clut, Nouant, and the Gododdin. If he could convince, or more likely bribe, these kingdoms into joining the expedition, it would be a foot in the door to Arthur’s dream of unity among all Britons.

Arthur will have monetary support from the Empire and be able to gain supplies from the Roman populace he liberates from the Visigoths. For them, it’s mostly trading one tax collector for another, but at least Arthur isn’t Arian, and operates under Roman authority. Arthur will also get supplies from Syagrius. More importantly, Syagrius will supply an army, augmented by Frankish troops through his alliance with Childeric. Finally, Anthemius will bring a Roman army to join with Arthur and Syagrius, once the foothold is established. With their combined armies, they will be able to defeat Euric, return Gaul to Roman control, and reestablish normal trade routes.

Arthur tapped a place on the map. “Pictavis is ideally placed in terrain as a gateway between southern and northern Gaul. The walled city sits upon a strong position on a promontory over the river and would be ideal to hold while our allies advance from other points.”

The Retreat to Avalon, Chapter Nine

The ideal location for Arthur to establish his foothold and wait for reinforcements is Pictavis, modern Poitiers. The city’s strong position at a major geographic crossroads in Europe made it a vital strategic stronghold from Antiquity through the Medieval era. It is on the edge of the Visigothic zone of control, so not heavily garrisoned, and the Roman inhabitants are not fond of paying taxes to distant Arian Visigoths.

To get there, Arthur will have to get his army to Gaul and then to Pictavis. He doesn’t have a navy to speak of, nothing like the Romans had a century before, so moving the army to Gaul is his first challenge after raising the army. There is barely enough merchant shipping to handle the increase in trade, vital to raising money, so Arthur finds his ships in an unexpected way: he hires Saxons to transport his troops. After all, they were famed seafarers and happy to take anyone’s money. The Britons and Romans generally referred to any seafaring Germans as Saxons, and the Germanic tribes didn’t necessarily see themselves as allies of other Germanic tribes. In addition, any Saxons working for Arthur wouldn’t be raiding Britain.

Moving armies and their supplies doesn’t change much until the modern era.

Moving armies and their supplies doesn’t change much until the modern era.Still, moving 12,000 troops, their equipment and supplies is a big undertaking. It would require between 200 and 300 of the sort of ships available to them. That wasn’t an option, so Arthur will shuffle the troops in stages to a mustering point in Letavia, specifically Aletum, near modern Saint-Malo. This is a secure location in Gaul to gather his troops and supplies and make other preparations for the campaign, such as scouting and espionage. And as any good military commander knows, the last thing you want are bored soldiers standing around, looking for trouble. So as the troops gather, Arthur will send them on raids against the Saxon settlements in Armorica, to the east. It will give them combat experience as well as reduce the threat of Saxon attacks from there as the campaign proceeds.

There’s one more challenge for Arthur between Aletum and Pictavis: the Saxons of the Loire. According to the thin historical record, the Saxons controlled the Loire between the Atlantic Ocean and the city of Angers. There were many islands along the river for them to occupy, but they must also have controlled the walled town of Nantes. Supplying 12,000 soldiers and their mounts would require roughly 300 sheep worth of meat and 20 tons of grain, cheese, oil, salt, wine and other supplies, per day! If Arthur is going to cross the Loire and have secure lines of supply and communications back to Letavia and Syagrius, he’ll need to capture Nantes.

In 469, Arthur has his army assembled in Gaul and ready to move. He, Anthemius and Syagrius have put together a sound strategy. But as the old military maxim goes, “No plan survives first contact with the enemy”.

We’ll see how that first contact went in the next post. Thanks for coming by, and as always, I love to hear from you in the comments.

The post King Arthur’s Strategy For Gaul appeared first on Sean Poage.

July 11, 2025

People and Characters of The Arthurian Age

This post is really just to introduce a new permanent page on the website: “People and Characters of The Arthurian Age”. It’s a list of every historical and legendary character in my Arthurian Age series and related books, as well as the few that I invented. It includes information about them from the books, as well as their places in history and legend. And now by popular demand, I have included name pronunciation!

One of the most frequent questions I’ve had about my series is how to pronounce the characters’ names. As I’ve said in my article, “,” the best approach is to just go with whatever sounds good to you. But if you really want to know, you can now look it up on my website.

My print and ebooks always include an appendix with information on the characters, places, and terms, and I’ve already got some additional pages with this information on my website, such as “Arthurian Age Glossary, Locations, Terms“, “Arthurian Age Maps Collection“, and “List of Sources for The Arthurian Age“. So far, there are 233 people listed. Not all feature personally in the books. Some are people with minor references that have an impact on the history and story, so I include details about them, as well.

I hope this will be especially helpful for the ebook and eventual audio book readers. So now, if you’d like to check out the new page, you can find it in the links bar, above, or click on this link.

Something else that I am debuting today is a new bit of Arthurian Age artwork, from the amazing Peter Xavier Price! He’s done some amazing work, especially on Tolkien subjects, that you can check out at this link. You’ll be seeing more of his work!

Thanks for stopping by, and please consider leaving a review for authors when you read a book. We appreciate it so much because it helps us get a little more notice.

The post People and Characters of The Arthurian Age appeared first on Sean Poage.

June 27, 2025

Why did Anthemius ally with the Britons?

I wrote The Retreat to Avalon largely to explore the practical application of the theories behind the research of the eminent historian, Geoffrey Ashe, and focused on the core of the premise: the great battle between the Britons and the Visigoths. I found Geoffrey’s thesis entirely cogent, but I wondered about the strategic, tactical and logistical problems faced by a military leader in the 5th century. Was such an expedition even possible? Why would Anthemius, emperor of the Western Roman Empire, ally with a king of the Britons they called Riothamus and who we know as Arthur?

The State of the Empire, 469-470 ADAnthemius is the Western Roman emperor, while Leo I is emperor in Constantinople. Both are struggling to deal with barbarian pressures: the Huns and Ostrogoths in central Europe, the Vandals in North Africa, Visigoths in Spain and southern Gaul, Franks on the borders of northern Gaul, Burgundians in eastern Gaul, and others, not to mention peasant uprisings like the Bacaudae.

The State of the Empire in 469 AD when Riothamus aids Anthemius against the Visigoths.

The State of the Empire in 469 AD when Riothamus aids Anthemius against the Visigoths.Even Gaul was splintering from the Empire. Even though Rome still claimed all of Gaul and parts of Germania, the empire had very little control beyond the city of Arles. The Burgundians controlled most of eastern Gaul and the Visigoths controlled most of southern Gaul. Three areas were cut off from the empire and operated independently, but remained Roman: the city of Avernis (Clermont-Ferrand), ruled by Ecdicius (brother-in-law of Sidonius Apollinaris– a name deeply associated with Riothamus), the domain of Syagrius, in northern Gaul, and the city of Trier, ruled by Arbogast. The Alans, settled at Orléans by Rome to control Armorica (Normandy), seem to have been under the rule of Syagrius. The Britons of Letavia (Brittany) seem to have become fully independent. Those living in the frontiers between these regions likely were left alone, or paid taxes to whichever ruler could project enough military might to coerce compliance.

All this doesn’t even take into account the internal troubles and political rivalries within the empire, itself. Anthemius became emperor in 467, after five other emperors had been elevated and either murdered or deposed and killed within the space of a decade. He was from Constantinople, not Rome, so his detractors called him “that Greek” and claimed he was only appointed to be Leo’s puppet.

A rare gold coin bearing Anthemius’ image

A rare gold coin bearing Anthemius’ imageEmpire politics in the fifth century were notoriously byzantine (the term actually comes from the original name of Constantinople, now Istanbul, and refers to convoluted, confusing, and sinisterly bureaucratic). Leo was preceded by Marcian, who appears to have intended Anthemius to succeed him. Marcian even married his only daughter, Marcia Euphemia, to Anthemius. However, Marcian died before appointing his successor, leaving this opportunity to his magister militum, Aspar.

Treacherous EmployeesAspar, an Arian of Goth and Alan descent, could not become emperor, but his control of the military gave him great power. He wanted a puppet, not an independent emperor, as Anthemius would have been, so he appointed the relatively low-level military leader, Leo. When it turned out that Leo was actually a fairly competent ruler that did not bend to Aspar’s wishes, the resulting conflict led to Leo having Aspar killed.

The western empire had the same troubles with Germanic-Arian magistri militum. In this case, it was Ricimer, a man of Suebic and Visigothic decent. His influence was behind the appointments of five Western Roman emperors, including Anthemius. He also was behind the deaths of at least two, and probably four emperors, including Anthemius.

Ricimer

RicimerRicimer, like Aspar, wanted puppets he could control. Ricimer didn’t want Anthemius. He wanted an aristocrat from Rome named Olybrius. The Vandal king, Gaiseric, also wanted Olybrius to be made emperor, because his son and Olybrius both married the daughters of a former western emperor, and Gaiseric looked forward to immense influence through that relation.

Leo, however, didn’t want the Vandals, who he hoped to drive out of North Africa, to have any more influence in the empire, so he put forth Anthemius as the candidate. Ricimer wasn’t happy about it, but he wanted to repair relations with the eastern empire and have more leverage against the Vandals, so he agreed, and Anthemius became the western emperor.

Anthemius was an effective general and diplomat. If not for internal politics and some plain bad luck, he may have reversed the decline of the Western Empire. He married his daughter, Alypia, to Ricimer in the hopes of gaining his loyalty. After a campaign to retake North Africa from the Vandals ended in a disaster and the permanent loss of that region, Anthemius turned his attention to the second major problem facing the Western Empire: the Visigoths.

In 410, the same year that the Britons expelled the Roman magistrates from Britain, the Visigoths sacked Rome. Such a thing had not happened in 800 years, when Rome was a small city-state sacked by the Gauls. The Visigoths later settled in southern Gaul and formed their own kingdom as federates of the Roman Empire, but eventually expanded their control into Spain.

Fickle AlliesThe empire’s relations with barbarian tribes were a muddled mess of warfare, bribery, offering land for protection against other barbarians, making treaties, then violating those treaties when either side found it convenient. The Visigoths were a prime example. Forty-one years after sacking Rome, they helped the Romans defeat Attila the Hun at the famous Battle of the Catalaunian Plains (the apparent inspiration behind J.R.R. Tolkien’s Battle of the Pelennor Fields in The Lord of the Rings).

The Charge of the Rohirrim from The Return of the King

The Charge of the Rohirrim from The Return of the KingTo make peace with the Visigoths, and enlist their help retaking Iberia (Spain and Portugal) from the Vandals and other Germanic tribes that had taken over the peninsula, Rome settled the Visigoths in southern Gaul as foederati – independent allies sworn to provide Rome military protection. With their capital at Toulouse, they soon expanded control into of most of Iberia. The Visigoths weren’t content with these lands, and had their eyes on the rest of Gaul.

In 453, Theodoric II murdered his brother to take the kingship of the Visigoths. Theodoric suffered several defeats against the Romans, and had to cede territory and submit to being a Roman vassal again. In 461, Ricimer assassinated Emperor Majorian and installed Severus III as emperor. The western Magister Militum, Aegidius, refused to accept Severus, so Ricimer called upon the Visigoths and his Burgundian allies (Ricimer had married the sister of the king of the Burgundians), and waged war on Aegidius. Ricimer and Theodoric were defeated at Aurelianis (Orleans), and this string of failures seems to have led to Theodoric being murdered by his brother, Euric.

With Euric now king of the Visigoths, he consolidated power by defeating other Visigoth chiefs and began retaking Iberia. He certainly still had an interest in expanding his territories in Gaul, and Anthemius had to find a way to stop the bleeding.

Anthemius, however, had very few options. He barely had the funds to field a defense for Italy, and yet had to find a way to bring Gaul fully back into the empire. The 6th-century historian, Jordanes, said that Anthemius allied with “Riothamus, King of the Britons” to bring 12,000 soldiers to Gaul “by way of the ocean”. If you’ve read Geoffrey Ashe’s The Discovery of King Arthur, you will understand why this is the Arthur of history and legend.

Raising, supplying and transporting an army that large would have been a difficult, but not impossible or even unlikely thing at that time. Especially since this was at a point when the Britons seemed to have won a respite against Anglo-Saxon incursions. If you’ve read The Retreat to Avalon, you’ll see how I describe this endeavor. I’d love to know what you think.

Wrapping UpIf you’ve read The Retreat to Avalon, you know what happened from there. The next few articles will talk more about everything leading up and through that event. The next article, however, is in response to the most common thing I hear requested regarding the Arthurian Age series. I hope you’ll check it out. And I always love to get comments and questions!

The post Why did Anthemius ally with the Britons? appeared first on Sean Poage.

April 30, 2025

Ancient Espionage

I was about to get back into the next big event in The Retreat to Avalon, namely King Arthur’s capture of Namnetis (Nantes, France), when I realized that all the preparation for his campaign involved something I haven’t gotten into yet: Ancient Espionage! You might be surprised by how much espionage is going on in my series, The Arthurian Age.

I’ve always loved a good spy story. I’ve also had the background to know that espionage comes in many forms and nearly everyone has some experience with it. It’s not just Sterling Archer or Mata Hari. The smallish kid who has to outsmart the bullies to get safely home from school practices it. Politicians routinely use it on each other and their constituents. Journalists, businessmen, police officers, even parents. Espionage is about intelligence gathering, misdirection, deception. There is no reason to believe our ancestors weren’t sophisticated enough to make use of it, despite the lack of technology that makes it easier today.

Espionage in the Ancient WorldSome of the earliest references to spies come from the region of Syria and Iraq in the 18th century BC. The tablets describe well-developed approaches to military and civil espionage (great article here). The 15th century BC Egyptian Amarna Letters discuss deceitful diplomacy, uncovering disloyal citizens, covert operations and details of rival kingdoms. A century later, the Hittite king Muwatalli II sent spies posing as deserters to lead Ramesses II into an ambush at the Battle of Kadesh. Shortly after this, Moses sent twelve spies into Canaan to prepare for the Israelites to conquer the region. In the 5th century BC, Sun Tzu wrote The Art of War, with an entire chapter dedicated to espionage. The Arthashastra of the 1st century AD is an ancient Indian text about governance, including the use of espionage against citizens as well as foreigners.

Tablet from Mari with espionage details.

Tablet from Mari with espionage details.Everyone knows of the Trojan Horse of The Iliad. It’s hard to know how much is true history, but that wasn’t the only covert operation of that war. Odysseus infiltrated Troy as a slave to gather intel on the Trojans and determine their morale. Later, Odysseus and Diomedes infiltrated behind Trojan lines at night and captured a Trojan who had been sent to spy on the Greeks. They interrogated him, then killed him, and used the information to attack the camp of the Thracians, allies of the Trojans, killing their king, Rhesus.

The later Greeks used the scytale, an early encryption device that involved wrapping a material around a cylinder of a specific size, then writing a message, letter by letter, across each strip. Unwound, the strip of cloth would look like a random string of letters. The person receiving the message would wrap the strip around a cylinder of the same circumference, enabling them to place the letters in the correct order again. Anyone capturing the strip must first recognize it for what it is, and then correctly determine the size of the cylinder in order to decode the message.

Greek Scytale Encryption Device

Greek Scytale Encryption DeviceThe Romans made a science out of everything, and espionage was no exception. Their earliest spies were scouts and messengers assigned to military units. These developed into the Speculatores, experts who typically worked alone or in pairs gathering intelligence or performing special operations. They took on the roles of bodyguards, interrogators, executioners, torturers, and assassins. They were bodyguards for the emperor and operated as a secret police until that role was take over by the Frumentarii or “Grain Collectors”.

The Frumentarii began as couriers, tax collectors, and were in charge of getting grain supplies to military units. When the emperors decided they needed some sort of intelligence service geared more towards internal security, the Frumentarii were chosen because of their movements throughout the empire and contacts with civilians and foreigners. They became a secret police force until eventually disbanded due to the abuse of their considerable power.

Espionage in the Arthurian AgeWith the fall of the Roman Empire, western Europe became decentralized and structured espionage systems devolved. The two greatest sources of intelligence gathering were merchants and the clergy. The Church’s extensive network of priests, monks, nuns and community lay-members was a powerful source for the exchange of news and more confidential information. For the most part, this source would be focused on the aims of the Church, but could be shared when the Church’s goals coincided with a ruler’s goals, or unscrupulous members could find advantage.

Perhaps a greater source of espionage were the merchants and itinerant craftsmen. With the collapse of Roman trade networks in Britain, many crafted goods became rare and expensive. Merchants had to navigate pirate-infested waters, or travel roads beset by bandits. A tradesman, such as a blacksmith or skilled carpenter, might travel from place to place finding work, if unable or unwilling to find a permanent patron. In fact, the high status of craftsmen is portrayed in the ancient British poem, Culhwch and Olwen:

“The knife is in the meat, and the drink is in the horn, and there is revelry in Arthur’s hall, and none may enter therein but the son of a king of a privileged country, or a craftsman bringing his craft.”

The status afforded craftsmen and the wide ranging travels and networking of merchants made them privy to news, rumors and secret information. This fact was well known to the later Vikings, who often planned their raids based on information they received from merchants, or by working as merchants themselves. They would learn local customs, develop informants and learn who and where persons of power were located.

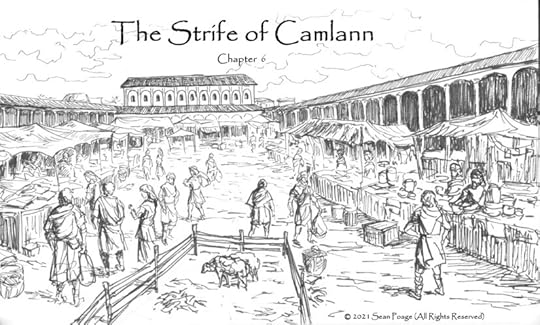

Marketplaces were a fantastic source for espionage.

Marketplaces were a fantastic source for espionage.Aside from merchants and artisans, money, threats, promises or revenge could turn servants, slaves and even family members into informants for an adversary to use. A wily leader looking to mislead an adversary could use the ever present rumor mill amongst soldiers, or community gossip channels to spread disinformation, knowing that the enemy has his own spies. And you can be certain that women were far more influential than their mentions in history books would make it appear. There is a great article about the history of women in espionage at this link. I even wrote a short story called The Letter, about a girl who becomes a spy in one of the pivotal events related to The Retreat to Avalon. While the event is real, the specifics, including the main character, are my own speculative invention. If you would like to read the story, send me your email address, and I’ll be happy to send it to you for free.

Additional SourcesIf you’ve already read The Retreat to Avalon, you may recognize some of the espionage techniques I’ve talked about here. A couple of good books that were part of my research, if you are interested, are The Enemy within: A History of Spies, Spymasters and Espionage by Terry Crowdy, and Spies, Espionage, and Covert Operations: From Ancient Greece to the Cold War by Michael Rank.

Thanks for coming by. As always I love to get comments and questions. And if you can spare a moment to leave a rating or short review for any books you’ve liked by any author, you can be assured each one is greatly appreciated and helps so much.

Book II of The Arthurian Age

Book II of The Arthurian AgeThe post Ancient Espionage appeared first on Sean Poage.

March 15, 2025

Taxes in The Arthurian Age

So I just finished doing my taxes; that time of year when I get acid-reflux and my wife says I turn from her easy-going teddy bear to an irritable grouch. Sorry, babe. Anyways, it got me thinking about taxes in the Arthurian Age. How were taxes collected and what was done with them?

The Romans had, much like the other aspects of their empire, a methodical system for taxes. There was a census about every five years and this was used to assess a yearly poll tax on each adult, which tended to vary. There was also a tax on the value of land, of around 1% to 3%. Custom duties were collected at borders, bridges and gates, at around 2.5%. Items sold at auction were typically taxed at about 1%, and there was a 5% inheritance tax (usually not charged against close relatives). This is rather generalized, partly because additional taxes might be levied in times of emergency, but also because of how the taxes were collected.

Local aristocrats were appointed by the government to collect the taxes, but these people were not going door to door for the often dirty and always thankless job. Sometimes they appointed tax collecting officials who were paid a salary, but more often, they would offer contracts to private citizens or companies to collect taxes. The contractors, known as “publicani”, would offer to pay all the taxes up front. The highest bidder was given the contract to collect taxes from the population. The publicani made their profit by whatever they could collect above what they had paid to get the contract. Needless to say, graft, extortion, cheating and even violence was not uncommon and tax collectors were often seen as the lowest of vermin within the empire.

Tax revolts were not uncommon in the empire, particularly in the 3rd century, when the Western Roman Empire was in crisis. Insurgents known as bacaudae, made up of peasants, runaway slaves and army deserters, caused as much trouble as barbarian invasions and even caused regions, such as Armorica, to break away from Roman control.

Prior to the Roman occupation, most of Britain operated on a barter system, aside from some southern tribes that used coinage because of their frequent trade with Roman Gaul. Rome’s introduction of a standard currency in Britain made trade easier, as well as tax collection. After the Roman government in Britain collapsed, coins became rare and the Celtic British quickly reverted to their old bartering systems for what little trade remained. It changed how taxes were collected in the Arthurian Age.

Without a centralized government, local rulers, warlords and petty kings had to fund and feed their warriors and households from their decentralized holdings. It was difficult and often arbitrary to extract food, livestock and goods from peasants who learned to hide the meager returns of their subsistence farming well, or risk starving. Some taxes were collected from trade, but often, the warlord’s best source of wealth came from raiding their neighbors, and this contributed to the endemic warfare which characterized the “Dark Ages”.

As the early Anglo-Saxons became more established in Britain, they brought their own tax system. It was based on the “hide“, which was a unit of land capable of supporting a free peasant family, usually about 120 acres. A tenant family paid their taxes in much the same way as the Britons, until the Anglo-Saxons started using their own coinage in the 7th and 8th centuries. They also had a system of fines for judicial cases that were paid to the king.

In Europe, the nomadic Huns didn’t have a formalized tax system, instead relying on raiding, plunder, and tribute from those they conquered. The Visigoths in Gaul and Hispania collected tribute from their formerly Roman subjects and also assessed land taxes based on the Roman practice.

In my novels, I have some portrayals related to taxes in the Arthurian Age. If you recognize any of them, or having any thoughts on the subject, I’d love to hear from you. Until next time!

The post Taxes in The Arthurian Age appeared first on Sean Poage.

January 30, 2025

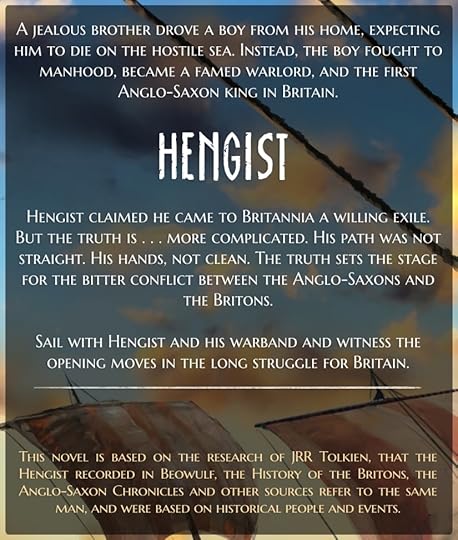

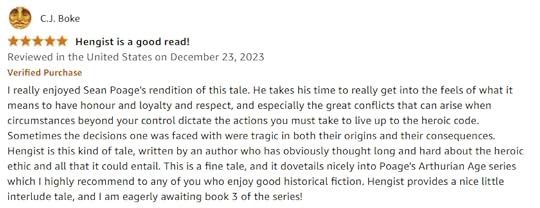

Grab HENGIST for Free!

Hi folks! I’m past due for a blog post, but that is because I have been putting all my spare brain power into writing Three Wicked Revelations, book 3 of my historical fiction series, The Arthurian Age. Today I’m doing a quick post to let you know that the ebook version of my novella, HENGIST, is going to be available for free for five days, starting tomorrow, February 1st through the 5th, 2025.

All I ask is that you leave a rating when done. Well, ok, I can’t hold anyone to that, but I’d really appreciate it. You don’t even have to write a review, but if you do, that is appreciated, also. It’s not too much to ask for a free book like Hengist, I hope.

Below is the blurb from the back of the book, but you can also check out my blog post about it.

So what can you expect from this book? Here are a few reviews that might help you decide:

So if this interests you, you can click on the link below, or go to Amazon and pick it up. Thanks!

Hengist: Exile, Warlord, First Anglo-Saxon King in BritainAmazon.com: Hengist: Exile, Warlord, First Anglo-Saxon King in Britain: 9798988610106: Poage, Sean: Books

Hengist: Exile, Warlord, First Anglo-Saxon King in BritainAmazon.com: Hengist: Exile, Warlord, First Anglo-Saxon King in Britain: 9798988610106: Poage, Sean: Books

The post Grab HENGIST for Free! appeared first on Sean Poage.

November 21, 2024

Illtud the Soldier, Teacher, Saint

Today we’re talking about one of the more interesting characters who appears in both The Retreat to Avalon and The Strife of Camlann. His name is Illtud, and he is known in history and legend as a soldier who served King Arthur, a saint, and a great teacher.

If you are familiar with my Arthurian historical fiction series, The Arthurian Age, you’ll remember Illtud as one of Gawain’s junior officers, who goes on to greater things. His role seems minor, aside from being Gawain’s friend, but he makes important and long-reaching contributions to the story, and to history.

Like nearly everyone from this era, we don’t have many written records about Illtud. The earliest, The Life of Saint Sampson, was written in Brittany around 600 AD, which is not long after Illtud’s life. While the book is about Sampson, another British saint, it discusses St. Illtud. It described him as a student of St. Germanus, and the most accomplished of all of the Britons in scripture, all kinds of philosophy, science, mathematics, rhetoric, grammar, etc. He was even said to have the gift of prophecy.

Illtud the SoldierIlltud was the son of a warrior named Bicanus and Rieingulid, the daughter of a prominent ruler in Letavia (Brittany). He may have been born in the borderlands region between modern England and Wales, which would not be unusual, as British aristocrats often maintained lands in both Britain and Letavia in this era. His parents were said to have intended for him to join the clergy, and had him educated towards this purpose. However, for unstated reasons (I supply a possibility in The Retreat to Avalon), Illtud abandoned that path, took a wife named Trynihid, and became a soldier.

As a soldier, Illtud was said to have served for a minor warlord, then under King Arthur, and this seems to have the seed of truth to it. Interestingly for those who enjoy the later medieval Romances, Illtud is one of the triumvirate, along with Cadoc and Peredur, to whom Arthur gave custody of the Holy Grail. For this reason, he is sometimes identified with the character “Sir Galahad“. He is said to have helped with Arthur’s funeral arrangements, a concept that predates the idea that Arthur never died.

Sir Galahad, from the Medieval Romances

Sir Galahad, from the Medieval RomancesAfter his time as a soldier, he is said to have had a change of heart and took up a religious life, studying under Bishop Germanus of Auxerre, a city in France known at that time as Autissodoro. Germanus was a major mover of his time and features heavily in the history and legends of the Britons. You’ll be meeting him in book 3, Three Wicked Revelations. Historically, Germanus is very important because his is one of very few hagiographies written soon after his life. It contains rare details of 5th Century Britain, such as his visit there to combat Pelagianism, which was considered a heretical sect of Christianity originating in Britain.

Illtud was said to have driven off his wife (who was said to have become a nun) when he devoted himself to the Church, but this is likely an invention by later medieval writers when the Catholic Church banned priests from being married in the 11th century. Some say it was due to the belief that celibacy allowed priests to be focused on their Godly mission. However, it’s thought it had more to do with medieval law and the Church being concerned about the children of priests inheriting Church property. In any event, married priests were not uncommon in the early Church, and even monks and nuns could be married, though this was generally not the case if they lived in monastic communities.

Slight Spoilers Ahead…However, there’s a bit of a problem with the record of Illtud being a disciple of Germanus, and that is timing. Germanus died no later than 448, well before Illtud would have been old enough to study under him. In The Retreat to Avalon, I reconcile this by having Illtud study under Bishop Censurius, who was a student of Germanus, and took over the bishopric of Auxerre after Germanus. He lived in precisely the right time for Illtud to have studied there.

Saint Germanus

Saint GermanusInterestingly, Auxerre is only about 30 miles (50 km) north of the village of Avallon. If you’ve read Geoffrey Ashe‘s book, The Discovery of King Arthur, or my novels based on his research, you’ll know that this is the location in France where Arthur and his army retreated to after the Battle of Deols. In The Retreat to Avalon, I show how simple it would have been for Illtud to have changed course and stayed at Auxerre.

Illtud the TeacherIlltud studied to become a monk, was ordained and returned to Britain. In Book 2, The Strife of Camlann, we meet up with Iltudd again. He is a teacher and the abbot of a school established at the site of today’s St. Illtud’s Church in Llanilltud Fawr (translates as “Illtud’s Great Church”) in southern Wales.

There may have been an earlier school there, established by the Romans in the 4th century called the College of Theodosius. It was said to have been destroyed by Irish raiders and abandoned until re-established by Illtud. The College of Theodosius is suspected to be the invention of a Welsh antiquarian named Iolo Morganwg, but may have come from oral tradition. There are nearby Roman villa ruins that may have been used as a school. In any event, Illtud’s school was the first school established in Britain, at least since the end of the Roman era.

St. Illtud’s Church

St. Illtud’s ChurchIlltud was famed for teaching some of the more famous people in Dark Age Britain, including St. Sampson, St. Gildas (who you’ll know from Book 2 was a contemporary of King Arthur), and the king of Gwynedd, Maelgwn (another interesting historical character portrayed in Book 2). Gildas, the only surviving source of records from Britain in this era, called Illtud the most refined teacher of almost the whole of Britain.

Illtud the SaintSaint Illtud is not an “official” saint of the Catholic Church, because official canonization of saints didn’t begin until 993, when Pope John XV canonized St. Ulrich of Augsburg. Before that, saints were proclaimed by the voice of the people who believed the person was saintly. It seems Illtud was revered for his wisdom, piety, and role in establishing monasticism in the region.

Illtud as a teacher. Note the Celtic tonsure of the monks (shaved forehead instead of crown of the head, as the Roman Catholic tonsure).

Illtud as a teacher. Note the Celtic tonsure of the monks (shaved forehead instead of crown of the head, as the Roman Catholic tonsure).Later medieval beliefs required the performance of miracles to prove holiness. Yet, even the later stories seem to suggest that Illtud did not perform miracles himself. Rather, God sent miracles on his behalf, often for his safety. Illtud is described as a pacifist, always forgiving of even his worst attackers. This might not seem so out of character for a veteran of terrible wars, particularly Arthur’s last battle.

Illtud passed peacefully some time in the early to mid 6th century. He is said to have been buried at his church in Llanilltud Fawr, which is most likely, though some legends say he was buried about 60 km to the north, near the town of Brecon, in the Church of Llanilltud.

Thanks for coming by, and I love to get comments and input!

The post Illtud the Soldier, Teacher, Saint appeared first on Sean Poage.

October 4, 2024

Were Ancient Battles Utter Chaos?

My last post about The Retreat to Avalon talked about the legends and history behind King Arthur’s military adventures in Europe. Gawain is about to be in his first major battle. Now, most people have an image of ancient battles being utter chaos. A non-stop bloodbath until everyone on one side was dead. But is this reality, or Hollywood? Let’s look at some of the most common portrayals of ancient battles.

Charge!The charge is a great image on screen and when described in print. Very dramatic. But did real battles start like that? Very unlikely.

Let’s start with infantry. Imagine you’re an average fit person who must carry, at the least, a spear and shield, and run with it. A fit person can sprint for about 30 seconds, covering, at the most, about 100 meters. That being considered, you also need to meet the enemy with enough breath to actually fight. I’ve had to run in full modern combat gear, which isn’t much different in weight from medieval soldiers, and I can tell you, under stress, even moving in short bursts from location to location can leave you gasping pretty quickly.

Love that last guy!

Love that last guy!So these long charges by foot soldiers just aren’t in the cards. A typical engagement would start with the attackers walking towards the defenders, who likely stayed put, having chosen the best location they could find to defend. Archers, if any, would try to soften up either side when they were within range, and the attackers would either hunker down to wait until the enemy was out of arrows, or move quickly forward to close the gap. But still, not at a full run, in most cases.

An example is in the famed Battle of Marathon, in which the Greeks were said to have overwhelmed the much larger Persian army by unexpectedly running at them. The Greek army was composed mostly of heavy infantry (hoplites), while the Persian army employed a great many archers whose effective range was about 200 meters. The Greeks marched towards the Persians, and once the arrows started falling, they began to run, most likely to close the space to the lightly armed Persian archers as quickly as possible, trusting to their heavy armor to protect them. Still, it was probably a jog for most of that 200 meters. Greek hoplites were famed for being in excellent physical condition, but their armor and weapons weighed between 50 and 70 pounds. The real sprint probably didn’t happen until the last 50 to 30 meters, at best.

Returning to our Dark Age warriors, javelins, thrown spears and axes would often be exchanged when the two sides were with range of these hand thrown weapons, about 15 to 30 meters, and then any charge would likely follow while the enemy’s head is down. That’s not too far to sprint and still have some energy left to fight.

What about cavalry? A horse can “sprint” much farther than a human, of course. More than a mile or two, and faster. But cavalry soldiers are pretty careful about their mounts. They’re expensive as well as important. You don’t want your horse blown on contact with the enemy. Another major issue is terrain. A mass of horses in close formation doesn’t have room to maneuver much, and high speed makes it harder for the horse or rider to spot holes and other obstacles that could bring the horse down. So, while the Charge of the Rohirrim in the Return of the King movie is epic, in reality they would not have hit full gallop until at least within bow range. For example, the British cavalry manual, stated:

Single Combat in the Chaos“Whatever distance a Line has to go over, it should move at a brisk trot, till within 250 yards of the enemy, and then gallop, till within 40 or 50 yards of the point of attack, when the word ‘Charge’ will be given, and the gallop made with as much rapidity as the body can bear in good order.”

Regulations for the Instructions, Formations, and Movements of the Cavalry, 1851

Most Hollywood representations of battles show a massive fight of individual battles. It’s utter chaos, with everyone running different directions, picking out whichever enemy happens to be nearest, with no real problem discerning friend from foe. A good example is the “Battle of the Bastards” scene from Game of Thrones. (Caution – includes graphic violence.)

Scene from Game of ThronesEven some of the better depictions, like in the Last Kingdom series, might start off with a realistic battleline, but it quickly devolves into a mashup of single combat scenes. If Uhtred wasn’t impaled by a spear as he leapt over the Viking shieldwall, he would have been surrounded by angry Vikings with no support from his own men.

The key to victory has always been teamwork. The Greek historian, Plutarch, wrote of the Sayings of Spartans, “a man carried a shield for the sake of the whole line.” Aside from the protection gained by having friends with shields to either side, there was the most important aspect: psychology. People are braver in groups than they are alone. The love of your friends, their encouragement and boasts, and most importantly, their judgement, all these things drove men to face death. But everyone has a breaking point.

What surprises most people is the fact that the casualties in battle are very low until one thing happens: one side breaks and runs. Whatever causes it, exhaustion, confusion, fear that their side is losing, it only took a few men to lose their nerve and flee, causing more men to run. At a certain point, the dam breaks and instead of a trickle of men running away, it becomes a flood. Those who did not break, who try to hold the line, find themselves at risk of being enveloped as the enemy pushes through on either side, so most of them will turn and run.

Nearly all of the deaths in these battles came, not from the two sides stabbing at each other, but from behind. Roman records give us an idea of just how great a disparity: the winning side suffered about 4-5% casualties, while the losing side suffered 15-30% (sometimes more). To visualize it, imagine a small battle of 100 soldiers on each side. During the battle, each side would only lose four or five men. Yet, when one side broke and ran, the losing side would lose another ten to twenty-five. This is why cohesion is so important in military units to this day.

Just One RoundAnother major error is when people think that battles were short, single engagements of non-stop, brutal hacking and stabbing until one side was destroyed. That works well for movies, but not in real battles. Think of a boxing match: those are highly trained athletes wearing shorts and gloves, and even they don’t fight for more than three minutes without a break. When I was in the Army, we sparred with pugil sticks – padded sticks we would use to beat the sense out of each other. Those are the longest three minutes you’ll ever experience, and you are pretty well blown by the end of it.

Raids and skirmishes would have been short, relatively low-casualty affairs. Full on battles (aside from sieges) between significant numbers of combatants would last hours to a full day, or even span multiple days. No one is going to fight, hand-to-hand, non-stop for even an hour. Instead, what is most likely is that when the two battle lines met, there would be several minutes of intense conflict, pushing with shields, stabbing with spears, etc, then the two sides would move apart to rest, reorganize and deal with the dead and wounded as best they could.

A reasonably good Hollywood representation of this is found in this clip from the series, The Last Kingdom. (Caution – includes graphic violence.)

Scene from the series, The Last KingdomThe Roman army was an exception to this. Rome employed full-time professional soldiers that drilled constantly. Therefore, they were able to practice and perform complicated maneuvers such as rotating ranks through a formation. This would allow them to keep a fight going longer to exhaust and break the enemy.

The Romans didn’t leave any details on how they performed this maneuver. This clip from HBO’s series, Rome, shows one idea of how it may have worked. I think this depiction has some flaws, but it is close to what must have been done. (Caution – includes graphic violence.)

Scene from HBO’s series, Rome.This would not apply to most of the medieval period because large standing armies able to train constantly just didn’t exist. Especially in the “Dark Ages”. A warlord typically had a warband of around thirty five warriors. The richest may have had up to one hundred fifty. So a typical battle between two warlords would have been quite small. Larger battles bringing together multiple warlords and their retinues still wouldn’t reach the level of Roman or later medieval battles. The English army at Hastings mustered only about 7-8,000 men, only about a thousand of whom were full time warriors.

In chapter four of The Retreat to Avalon, the men preparing to join Arthur’s army have all grown up with some basic training in fighting together in the “shield wall”. But this was for small battles, skirmishes and raids. They are facing a battle of a size that only the Roman Empire could muster. Their instructor says:

“In practice, it’s a simple thing to rotate through the lines,” Gwalhafed, explained. “But in battle, it’s near impossible. The wounded are often trampled or suffocated. Sometimes the press is so dense the dead cannot even fall to the ground. If the fight goes long, and men must rotate, you’re more likely to be crushed or attacked as the man behind you tries to take your position. The best you can hope for is to cover yourself, let the tide wash over you and pray that you soon find yourself behind the lines of your men, and not of the enemy.”

The Retreat to Avalon

One of my goals in writing The Arthurian Age was to immerse readers in the reality of life in the “Dark Ages”. The era was not as primitive as the term, or Hollywood, would lead you to believe. Most writers have never served in the military, much less actually fought for their lives, so I’m fortunate to have some experience to draw from. Like most writers, I dream of seeing my book on the big screen. But I fear what Hollywood might do to it. Movie directors look for excitement and visual impact over veracity. This results in wildly unrealistic portrayals. It’s too bad, because this need not be the case. Maybe someday I’ll get lucky.

Thanks for stopping by. As always, I love to hear from you in the comments. And if you’ve read any of my books, please leave a short review where you bought it. It helps authors so much.

Book II of The Arthurian Age

Book II of The Arthurian AgeThe post Were Ancient Battles Utter Chaos? appeared first on Sean Poage.

August 11, 2024

Janet Morris

I’m in one of my rare periods of melancholy. Yesterday, a dear friend, mentor and just amazing person, Janet Ellen Morris, passed away at the age of 78. I’ve only known her and her husband, Chris, since 2017, but that connection has had a major impact on my life. From the outpouring of her fans and friends who have learned of her passing, it’s clear that she’s had that sort of influence on everyone who’s been blessed to have spent time in her orbit. There are others, especially Chris, who can say more than what you’d find in her Wikipedia article, so I should only speak to what I know. Forgive the inevitable turn that feels like I’m making it about me. It’s the nature of a memorial, I suppose.

Chris and Janet

Chris and JanetIf you haven’t heard of Janet, you’ve missed out. If you have, you probably understand the subtitle on the post image. She’s authored more than forty outstanding novels and several non-fiction books, many in cooperation with Chris. Most of these are in fantasy and science fiction, though she has a masterpiece of historical fiction called I, The Sun, about the Hittite King, Suppiluliuma I. Her first novel, published in 1977, was a post-apocalyptic work called High Couch of Silistra, the first of a tetralogy. Janet’s and Chris’ non-fiction works involved national security, non-lethal weapons and other defense technologies that brought them into the upper echelons of national and international consulting and research.

I think I was in 7th grade, living in Yuma, Arizona, when I first saw her name. I had been the sort of reader who picked up a book when I had nothing else to do. When my mother handed me The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings series, I discovered a new world. Wanting to visit more such worlds, and bugging my mother about it, she handed me a book called Thieves’ World, an anthology of short stories from the best authors of the time set in the shared universe of a town called Sanctuary. It came out in 1979, and its dark, cynical, exciting atmosphere was very different from Middle Earth. Janet’s first story in the series, “Vashanka’s Minion” appeared in the second book of the series, Tales from the Vulgar Unicorn, and her character, Tempus, and his band of mercenaries became my favorites of the many denizens of Sanctuary. Janet’s contributions to Thieves’ World were so impactful, that the entire 12 book series was shaped more by her characters, stories and ideas than any other single author.

The cover of one of the books I managed to never lose.

The cover of one of the books I managed to never lose.No matter where I moved, those books, and Janet’s spin-off novels, like The Sacred Band, went with me. Anyone who’s been in the military, where limiting personal belongings is a virtue, can appreciate what that means. When I stepped into the world of writing, Janet’s wordcraft is what most influenced me, even if I couldn’t hope to match hers. My novels even have some scenes that were inspired by scenes from her books.

So, when my first book was at the publisher, in the process to get it out into the world, I found Chris and Janet on Facebook. With little hope of hearing back, I sent a message explaining how she has been such an influence on my writing, and that I wondered if she’d be willing to read my first novel. To my surprise and delight, she not only responded, but agreed to read the book and offer a review.

Publisher Par Excellence

Publisher Par ExcellenceYou can only imagine my excitement when she told me she liked the book and invited Jennifer and I to visit her and Chris. Jenn and I made the first of several such trips in which I had to restrain my inner fan-girl each time. Janet and Chris offered me the honor of contributing to their anthology, Heroika: Skirmishers, and it became my second published work with my short historical fiction story, “A Handful of Salt”. Their mentorship greatly improved my writing, and the first examples of their instruction may be found in that story. Not only that, but Chris graciously began teaching me the art and science of book publishing, which made me appreciate what it takes to put out a professional product. Their decades of experience has made their company, Perseid Press, a well-respected publisher. So it was an even greater honor when they took over the publication rights of The Retreat to Avalon and published the second novel in the series, The Strife of Camlann.

Janet and Chris have become dear friends. I treasure those late nights, soaking in everything she and Chris had to say about writing, publishing, heroic literature, history, horses, dogs, their fascinating lives-it’s a font of knowledge and advice that I have been so fortunate to have sipped from. We loved meeting their beautiful Morgan, Field of Honor, playing with their lovely Belgian Tervurens, Tailer and Night, getting a tour of the places where Janet grew up, or getting the best ice cream we’ve ever had from a local spot. We’ve enjoyed sitting in as Janet and Chris practiced their music. Who would have thought she was a base player! You can-and should-catch their music here.

Watching Field of Honor strut his stuff.

Watching Field of Honor strut his stuff.Like I said, this post shouldn’t be about me. There are others who can offer far more than my small memorial. I guess this is my way to make something concrete of the impact she’s made on my life in the short time I’ve been blessed to know her. Immortality is not just found in the spirit, but in legacy. Janet has bequeathed a legacy to me and to many others, and that immortality, how we impact the lives of those around us, is a gift she gave of freely and generously.

The Perseid meteor showers are underway, as if the heavens, too, salute our commander.

Janet and Night

Janet and NightThe post Janet Morris appeared first on Sean Poage.